Introduction

Intuition (in Latin intueri) is a human characteristic that does not have empirical evidence of its existence, but yet provides knowledge, even if nobody is conscience or can verbalize in a structured way. If intueri means “to consider” or “to contemplate”, both of them are verbs without an implicit action but an activity of the contemplative life (Arendt 1971). For considering intuition, the Kuhn’s approach is taken in this article:

“First, if I am talking at all about intuitions, they are not individual. Rather they are the tested and shared possessions of the members of a successful group, and the novice acquires them through training as a part of his preparation for group-membership. Second, they are not in principle unanalysable” (Kuhn 1970, II:191).

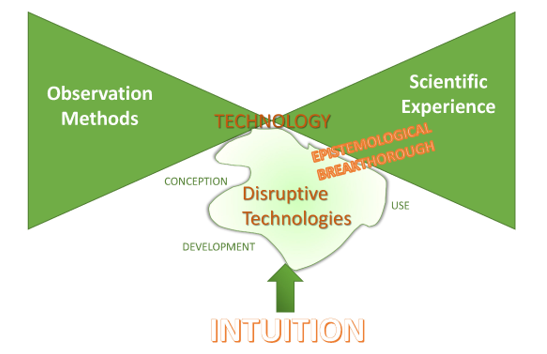

The transcendence of limits of human experience is a universal concern for the humanity, and -attending to the high speed of the technological change that we witnessed today- its study is more relevant than ever. However, human characteristics that are not scientifically justified are hard to study in relation with innovations today, since science and technology are mainly related to observation and scientific experience. Therefore, not rational, scientific or analytic modes of thinking are appropriate for researchers of every arenas if we consider the intuition as one of their facilitators. For instance, Oliver Markley essay´s (Markley 2015, 119) shows the reflexion of the scientists about using intuition for their own research: ‘I have come to rely on many types of processes for eliciting intuition—not as a replacement, but as an integral complement to rational/analytic methods for insight, foresight and wise-choosing’. So, intuition may be a fascinating mechanism for activating other approaches since the human mind if we consider its use for innovating.

Nowadays, technologies experience rapid changes, and also impact on the society faster than ever. For instance the driveless cars, the Internet-of-the-Things, 3D Printing and the blockchain are considered disruptive innovations (Rahman et al. 2017; Vicente-Oliva 2018; Frizzo-Barker et al. 2020; Woensel and Archer 2015), and they are capable to create complete technological ecosystems (Jacobides, Cennamo, and Gawer 2018; Gomes et al. 2021). Disruptive innovation able to provide a new set of attributes of a new product with some characteristics with lower performance but with other very attractive ones that are greatly appreciated in the market at ones that stimulates a disruption towards current existing products, market, and value network, thus subsequently replacing the previous technology (Christensen 1997). However, its evolution is not yet possible to forecast because is a synergistic relationship with the entire set of novel technologies in each emergent technological paradigm (Devezas 1997). Moreover, by attending to how the inventions are exploited and their irreversibility after its introduction (Battistella and De Toni 2011), every economic and social science provides an essential support for all kinds of science. This is because economical and business inexperience go hand in hand with technical inexperience (Green, Gavin, and Aiman-Smith 1995) in such kind of inventions, and we revised several interactions in this article for exploring about how intuition can boost the conception, development, and use of disruptive technologies.

Therefore, the study of disruptive innovation has experienced plenty of difficulties1 since its original inception. Thus, a holistic approach -as this article adopts- is required for explaining the relation of intuition to disruptive technologies. The purpose of this investigation resides in the epistemological breakthrough between scientific experience and intuition that rely on two questions. The first one if for creators of new technologies (technicians and development teams): How do you conceive and develop disruptive technologies? The second question should be directed to users: Are you familiar with disruptive new technologies capable of making your life better? And more precisely: Could you explain to the creators how would you like to use technologies that are not still exist? There is no conceptual way that allows respond these questions because new technologies will not expand if people do not include in their life in form of goods, products or services, although the researchers did not create thinking about them.

Owing to the idea that intuitions are not individual (Kuhn 1970), a post-positivist approach is valuable in the analysis of the emergence, development, and use of disruptive technologies. It is commonly accepted today that technology mediates between the observation of nature and human experience (Ihde 1990). This is not a vision based only on occidental conceptions, but contributions from the East—with a different background—and also a great number of miscellanea of social, religious, etc. movements have their space in the universe of the perceptions and beliefs, which reflect the use of intuition and their impact on our societies though technology use. Following the structure of (Mitcham 1994), this article discusses intuition and innovation considering a perspective from artefact to habitat, and also includes some thoughts in the discussion section for future research suggestions based on the current tendencies.

Intuition and Innovation

If innovation is a word that points out something new or different that is introduced, and also the introduction of new things or methods, inventors cannot afford to engage in their activity without innovating. Attending to the perspectives that philosophy has adopted for discussing the innovation, artefacts, knowledge, activities, and characteristics of humanity are considered in the following sections.

Artefacts

Human beings have produced artefacts forever for their use as instruments, tools, decorations, and weapons. The physical characteristics (colour, shape, materials, etc.) can be studied separately from their functions (Jones, Buntting, and De Vries 2013). Although the first pragmatists (Peirce and James around 1900) considered only the practical effects of the objects in their insights, today the concept is broader. So, the technical effect the technologies can produce thanks to potential new functions is also important in the study of artefacts. For instance, new features can be designed to improve the speed of a computer network or create virtual communities for supporting research activities including even not specialized people.

The common interest for the technicians is grounded in the operation and performance of the technology. In this sense, post pragmatism and new pragmatism can regard technical artefacts in the forms of tools that exist to face social problems (Zhu 2009), so they is included together with social issues for characteristics of humanity (fifth section).

Technocracy, (as a theory ruled by technical experts) and its technocratic thinkers had influence on government and policy, especially, in the twentieth century. At this juncture, society was considered to be a machine run by engineering experts. However, even for them, the response to our research question passes throw “how is a technology considered inherently disruptive, or does disruptiveness depend on the perspective of the firms confronted with the technological change? At what point can disruption be said to have occurred?” (Danneels 2004, 248). Considering technology in isolation from acting subjects (Sikka 2012) produces items that can be utilized with high consequence for the entire of humanity, such as the nuclear bomb (Jaspers 1961) in the past or artificial intelligence development in the future. Frequently, the scientific community has been considered naïve about the possibilities of their inventions (Dusek 2008) because they were only focused in technology, or even their uses for a better world, for instance, there is no regulations about artificial intelligence development because it could be like preparing traffic rules for driving on planet Mars.

Today a separation between artefacts and the society that produced them is difficult to find (Liu 1992, 146), and technology has an instrumental use, focused on efficiency (Feenberg 2006). Intuition has no place as an instrumental concept within technology. Discussion about artificial intelligence or other technologies and its future development (and consequences for the human being) were grounded in this argument for the technologist, although society’s considerations can exercise a mediator effect creating some limitations and boosting the most required benefits. These technological positions will be watered down over time, when innovations will make known to the society.

Research on creativity related to innovation flourished in the last decade (Kwan, Leung, and Liou 2018). A search in the Web of Knowledge carried out with the keyword ‘Intuition’ came up today2 with 20,529 records, a growing amount of articles, books chapters and proceedings papers since 1990. Philosophy is the main area in number with 9.5% of them, although the sum of every aspect of the Computer Science (theory methods, information systems, software engineering, and artificial intelligence) composes 31.2%, and 21.2%% is represented by Social Sciences (Economics, Management, Psychology, and Ethics). So, intuition has increased scientific interest when human beings search for consciousness in their intelligent creations and try to find economic and social benefits, and find pitfalls for learning beyond their assignments.

If technology evolves, business models also have to evolve in order to find benefits and survive in case of ‘creative destruction’ (Schumpeter 1942). With a multilevel perspective, displacement and replacement of technologies occur in different markets, for instance, steamers (Geels 2002) or coal production and decarbonization and their impacts (Turnheim and Geels 2012; Rosenbloom and Meadowcroft 2014). When disruptive technology emerges, technological niches are created and developed in small networks, usually by a marginal part of the actors, although the limits are not clear, nor are their expansion (Rip and Kemp 1998). When potential customers emerge, market niches can evolve and build an image of the technology thanks to learning processes that increase the stock of knowledge of the technology, and show a more powerful group the possibilities of the technology (Geels and Schot 2007; Schot and Geels 2008). This contributes to the great expansion of the technology if there is an ecosystem that provide complementary acts (Kapoor and Lee 2013). However, users still have to learn how operate the new technology and knowledge is fundamental for it.

Knowledge

According to (Yusuf 2009), innovation are based on creativity and stock of knowledge. The nature of technological knowledge is distinct from other types of knowledge (Jones, Buntting, and De Vries 2013), by the fact, among other issues, that the inventors, developers, and users have a different body of knowledge about how to operate a technology. Dealing with a disruptive technology does not just involve after-dinner speeches around desires and visions about how could they work and what ought to do. Thus, the research and development (R&D) activities are combined with market forecast on these technologies (Roland Ortt, Langley, and Pals 2007) in a very complicated process where disruptive assets can reduce their effectiveness and efforts to afford and exploit radical innovation (Henderson 1993). This is because technological knowledge has a normative dimension, specifically if it can be learned and developed for useful utilization, although cannot be fully expressed in a manner for its understanding. Tacit knowledge is a concept applied by Polanyi (1966) for describing this kind of knowledge that exists inside people even if they are not conscious that it was acquired or the way they acquired it. Regarding innovation issues, tacit knowledge increased in importance for researchers especially after the Cohen and Levinthal (1989) article about the two faces of R&D: providing more information, and enhancing the firm capabilities to assimilate and exploit new information.

Frequently, a technology is used by human beings without a complete understanding of its composition, potential other uses, or considerations about its future development. Even if a child does not understand the scientific fundamentals of electricity, he or she knows how to operate the switch. What if every customer were capable of knowing, even in a tacit manner, how to work every technology involved in her/his life? Probably, their diffusion would be faster than others hard to use by people.

Affordability for individual customers is related to their ability to discern what new technologies are capable of making a great contribution to their life, and which ones will not make a reasonable one for them. In these terms, for whom does it not come to mind announcements of revolutionary technologies that would be able to change your life? The costs for learning how to use breakthrough technologies is frequently underestimated in economic models. This happens fundamentally because the transactional costs are assumed by users during the activities in which new technology is involved, although economic models on business administration discipline consider regularly.

Activities

The approach of cognitive sciences is especially valid for studying the development of disruptive technologies. The advances in social cognitive neuroscience rejuvenated scholarly research into intuition (Hodgkinson et al. 2009), especially when intuition is implicit in social relations. Each conscious experience is extraordinarily informative and differentiated for our consciousness (Tononi and Edelman 1998).

Koch (2012) interpreted the Toroni’s symbol Φ—expressed in bits—as a measure of the holism in a network. Regarding his simulations, small networks showed that achieving high values of this parameter was difficult and specialization and integration are required. Intuition could be an indivisible part of these characteristics, a personal property of inventors and developers that does not reduce the uncertainty in the invention environment, or in the user one. Today, teams for conceiving innovations are getting bigger every day and they involve more knowledge areas and are more complex; consequently experience and intuition go hand in hand with the pragmatic application of the theory (Winter et al. 2006). Tacit knowledge or uncodified explicit knowledge (Duguid 2005) is implicit in the activities directed at use of new technologies, and intuition seems to be a part of this kind of knowledge under this perspective. However, there is a question that remains without empirical evidence: How can we know the intuition of the employees separate from their individual stock of tacit knowledge?

Collective intuition includes expert intuition, as acknowledged by Akinci and Sadler-Smith (2019), because it provides opportunities for organizational learning as consequence of applying non-intentional solutions to crucial problems. For collective intuition, ‘all intuiting is tacit but not all tacit knowing is intuiting’ (Akinci and Sadler-Smith 2019, 560). Passing though the bounds of tacit knowledge or expert knowledge for managing business, intuition is not a studied activity for the organizations.

For the future, intuition would be needed for finding weak signals of change (Hiltunen 2008). Therefore, a new question needs a response: Are disruptive technologies sending early signals before they are dreamed up? If researchers would be capable of perceiving these, they could invent the technology that the world needs to face their challenges. The metaphysical derivations of this evidence open the window for speculations on the fate of humanity beyond organizations or the immediate surroundings of the researchers. The fact is that tacit knowledge has reached a quasi-mystical (Duguid 2005) status in economic sciences. Hence, on the ground of research methods based on evidence, it is accepted that physical and graphical models, analogies, and metaphors are general tools for the foresight practitioners, although not only for scanning the future. The tools that provide means for understanding, and dialogues about abstract ideas and entities that are not observable in very basic physical and social perceptions (Devezas 2005) encourage human interaction and social issues. Therefore, the interactions among researchers and users that share a common context can provide ideas and stimulus for conceiving and developing disruptive innovations, and for learning as social, rational activity. These are characteristics of humanity.

Characteristics of Humanity

For Heidegger, thinking was a reflection upon the original way to discover the world (Heidegger 1953), in opposition to rationalist thinkers like Descartes who locate the essence of the man in our thinking abilities. Phenomenology studies focus on the individual experience from a subjective point of view, and claim to achieve knowledge about the nature of consciousness through a form of intuition (Smith 2013). Today, post-phenomenology academics proposes a close analysis of human–technology relationships that consider—in a positive manner—technology as a tool to improve the experience of reality (Ihde 1990).

The context of time and use of breakthrough technologies are relevant for the Philosophy of Technology. The hermeneutics studies’ interpretative structures of experience involve tasks that are more ontological than methodological (Gadamer 2008). In this article interpretation of very unsettling technologies, there are not previous paradigm. Thus, nobody knows if disruptive technologies will make better or worst your life, and moreover your future life, although it seems rational choose only the benefits minoring the risks.

Future options and trends of technology are studied by optimistic and pessimistic approaches (Slaughter 1998). Therefore, concerns about the future are not so simple for technology developers: How could we know the unknowns?

Intuition does not play an active role in social changes if an individual point of view is adopted, although an intuitive society could shape technology in order to contributing to desired social change, a new attitude, and the supplementing of technological existence with other communal forms of existence (Dreyus and Spinosa 1997). A meditative thinking should be replace the calculative one (Dusek 2008, 128) due to in the postmodernist sight has the sharp-edged lines are not so keen. It is considered a plurality of “worlds” provided by technology (Dreyus and Spinosa 1997): virtual and real, natural and artificial, intuitive and deductive, etc. From this perspective, the inexistence of an absolute truth facilities a shared vision about the use of intuition for disruptive technologies.

Since a pragmatic point of view, the successful practices for innovation are not determined by a priori beliefs or ideologies. It exists successful relations between inventors and users shaped like collaborations in R&D, production, maintenance and re-desing (Hobday 1998). Considering the disruptive technologies were some negative effects of the society (dystopian ideals), the active and rational customer involvement should be desirable to minimize the impact. In addition, guaranteeing people’s freedom (Dusek 2008), is a main concern for the opponents of technology (among others romantics, luddites, and neo-luddites). Ramirez, Van Der Heijden, and Selsky (2008, 276) explained the addiction to prediction in the 20th century based in “the global spread of adversarial legalism, the increasing emphasis on evidence-based policy, the hubris of experts who drastically overestimate their own knowledge, and overconfidence in the benefits of quantitative approaches to risk management”. Therefore, emergence of some disruptive technologies, and their impact on economic and social issues are not predictable in an empirical way. There is an opportunity for novelties in the markets.

Ernst Kapp—one of the first “philosophers of technology”—pointed out that technology is the way humans extend their own natural organs (De Vries 2005, 68). Today, an intellectual movement called Transhumanism exists with the aim of exploring the elevation of human condition: it advocates the use of technology to expand human capacities and capabilities. The technological singularity will be the point in the future when the technology creates entities with greater than human intelligence (Vinge 1993, 12), a post-humanism era. However, the emotions, feelings, or other human characteristics remain without a clear role for shaping the future. Panpsychism, the consciousness (mind or soul) is a universal feature of all things, although Transhumanism considers “sentient beings” to be more than only the human being. For conceiving of disruptive technologies and their effects on humans, their impact should be studied in a wider operating range. The philosophy of mind goes further than technological issues: what if our human free will could be influenced by unconscious feelings, or even the intervention of other beings?

Discussion

If technology is the name of things that we do not yet use every day (Brimley, Fitzgerald, and Sayler 2013, 3), the future things exists only in our mind. Even from pragmatism arena -where there not place for mind and body dualities (Hookway 2008)-, intuitions can be “a good place to start” (Pitt 2011, 3:76).

The intense relation between technology development and its impact on society is undeniable. The concept of “reverse adaptation” from (Winner 1973) describes how the technological system adapts the society to technology rather than vice versa. For developing technologies, it is not necessary to imagine the fifth dimension, believe in alien life, or believe there is a life beyond death. However, there are people like us who think in alternative or evolutionary futures, dystopic or utopic conceptions, and potential or plausible scenarios.

In the arena of artificial intelligence and machine learning, there are recent studies that have recognized that people handle abstract concepts more successfully than computers do because of intuition and expertise (e.g. Agwu, Akpabio, Alabi, & Dosunmu, 2018; Boyer, Scherer, Fleming, Connors, & Whitehead, 2018).

The disruptive technologies development involves the reinterpretation of abstract knowledge in order to be operationalized in the technological problem resolution. Furthermore, improvisation and intuition are an approach that is nearer to a child’s thinking (Hennessy 1993), than researchers’ rumiations. New concepts from psychology, and new age conceptions of reality point to the empowerment of the “inner child”. Can she not be the voice of human intuition?

However, there is not an agreement about the relevance of intuition in the knowledge of humankind. For instance, the Shamkya philosophy considers intuition as a knowledge transcending the logics, or even a revelation (Talwar 2004), one of the higher intellectual functions (Schweizer 1993). It is considered the depository of the fundamental truth upstream from reason. Whereas for some classical philosophers as Compte, religion and metaphysics are inferior, less-evolved forms of knowledge in comparison with scientific knowledge (Dusek, 2008, p. 45); our industrial and post-industrial world does not yet match with spiritual conceptions of the intuition.

Conclusions

Researchers from Philosophy and Organizational studies arenas consider intuition a collective characteristic. However, their application for conceiving, developing, and using disruptive technologies needs a less theoretical frame in order to leverage the resources committed to innovation. This article does not solve the research question. Nevertheless, it is just an invitation for reflection, in order to find more pathways for human understanding in the future.

Scientists and technologists cannot conflict with the human features that could be able transcend beyond the world that we know today. However, there is an inherent question about the future: What about the inventions for tomorrow? We have an epistemological breakdown that needs more study because we are living in a challenging new era for entire humanity, with multiple challenges that are unresolvable solely from the scientific experience. A breakthrough between technology and collective intuition has never ever been so close; we have to wake up from our rationalist dream and afford new approaches. Are you ready?

Notes

| 1 |

An epistemological rupture was pointed out between them by Bachelard in 1938 (see Bachelard and McAllester Jones, 2002). More precisely, scientific experience in their own context (hermeneutic) could be reduced to a before-handed criteria regarding a concrete situation, a kind of ad hoc intuition (Karczmarczyk, 2013). If an emerging technology is arising for the inventors, developers, and clients, how do we save the breakthrough between scientific-technological experience and its significance?

|

| 2 |

The 4th of November, 2021. |

References

- Agwu, Okorie E., Julius U. Akpabio, Sunday B. Alabi, and Adewale Dosunmu. 2018. “Artificial Intelligence Techniques and Their Applications in Drilling Fluid Engineering: A Review.” Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 167 (April): 300–315. [CrossRef]

- Akinci, Cinla, and Eugene Sadler-Smith. 2019. “Collective Intuition: Implications for Improved Decision Making and Organizational Learning.” British Journal of Management 30 (3): 558–77. [CrossRef]

- Arendt, Hannah. 1971. The Life of the Mind. New York and London: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich.

- Bachelard, Gaston, and Mary McAllester Jones. 2002. The Formation of the Scientific Mind: A Contribution to a Psychoanalysis of Objective Knowledge. Beacon Press.

- Battistella, Cinzia, and Alberto F. De Toni. 2011. “A Methodology of Technological Foresight: A Proposal and Field Study.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 78 (6): 1029–48. [CrossRef]

- Boyer, Ryan C., William T. Scherer, Cody H. Fleming, Casey D. Connors, and N. Peter Whitehead. 2018. “A Human-Machine Methodology for Investigating Systems Thinking in a Complex Corpus.” IEEE Systems Journal 12 (3): 2837–2948. [CrossRef]

- Brimley, By Shawn, Ben Fitzgerald, and Kelley Sayler. 2013. “Game Changers: Disruptive Technology and U. S. Defense Strategy.”.

- Christensen, C. M. 1997. The Innovator\’s Dilemma: The Revolutionary Book That Will Change the Way You Do Business. Collins Business Essentials.

- Cohen, Wesley M, and Daniel A. Levinthal. 1989. “The Two Faces of R&D.” The Economic Journal 99 (397): 569–96.

- Danneels, Erwin. 2004. “Disruptive Technology Reconsidered: A Critique and Research Agenda.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 21 (4): 246–58. [CrossRef]

- Devezas, Tessaleno C. 2005. “Evolutionary Theory of Technological Change: State-of-the-Art and New Approaches.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 72 (9): 1137–52. [CrossRef]

- Devezas, Tessaleno C. 1997. “The Impact of Major Innovations: Guesswork or Forecast? On Chance and Necessity in the Evolution of Technology.” Journal Of Futures Studies 2 (February): 33–41.

- Dreyus, H.L., and C. Spinosa. 1997. “Highway Bridges and Feasts: Heidegger and Borgmann on How to Affirm Technology. Man and World, 30(2), 159-178.” Man and World 30 (2): 159–78.

- Duguid, Paul. 2005. “‘The Art of Knowing’: Social and Tacit Dimensions of Knowledge and the Limits of the Community of Practice.” The Information Society 21 (2): 109–18.

- Dusek, Val. 2008. Philosophy of Technology and Macro-Ethics in Engineering. Blackwell Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18427953%5Cnfile:///C:/Users/morganya/Documents/My eBooks/academic/Dusek, Val. Philosophy of Technology An Introduction.pdf.

- Feenberg, Andrew. 2006. “What Is Philosophy of Technology ?” In Defining Technological Literacy towards on …, 5–16. Palgrave Macmillan US. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=PQLGAAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA5&dq=What+Is+Philosophy%3F&ots=OLN4rYbTZu&sig=fnQ-0vjo8TkPoK_SxWPGcbXWopM.

- Frizzo-Barker, Julie, Peter A. Chow-White, Philippa R. Adams, Jennifer Mentanko, Dung Ha, and Sandy Green. 2020. “Blockchain as a Disruptive Technology for Business: A Systematic Review.” International Journal of Information Management 51 (October): 0–1. [CrossRef]

- Gadamer, H. G. 2008. Philosophical Hermeneutics. Univ. of California Press.

- Geels, Frank W. 2002. “Technological Transitions as Evolutionary Reconfiguration Processes: A Multi-Level Perspective and a Case-Study.” Research Policy 31 (June): 1257–74. [CrossRef]

- Geels, Frank W., and Johan Schot. 2007. “Typology of Sociotechnical Transition Pathways.” Research Policy 36 (3): 399–417. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, Leonardo Augusto de Vasconcelos, Ximena Alejandra Flechas, Ana Lucia Figueiredo Facin, and Felipe Mendes Borini. 2021. “Ecosystem Management: Past Achievements and Future Promises.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 171 (June): 120950. [CrossRef]

- Green, S.G., M.B. Gavin, and L. Aiman-Smith. 1995. “Assessing a Multidimensional Measure of Radical Technological Innovation.” IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 42 (3): 203–14. [CrossRef]

- Heidegger, Martin. 1953. “Being and Time: A Translation of Sein Und Zeit.” State University of New York Press in 1998. [CrossRef]

- Henderson, Rebecca. 1993. “Underinvestment and Incompetence as Responses to Radical Innovation : Evidence from the Photolithographic Alignment Equipment Industry.” The RAND Journal of Economics 24 (2): 248–70.

- Hennessy, S. 1993. “Situated Cognition and Cognition Apprenticeship: Implications for Classroom Learning.” Studies in Science Education 22: 1–41.

- Hiltunen, Elina. 2008. “Good Sources of Weak Signals: A Global Study of Where Futurists Look for Weak Signals.” Journal of Futures Studies 12 (4): 21–44. [CrossRef]

- Hobday, Mike. 1998. “Product Complexity, Innovation and Industrial Organisation.” Research Policy 26 (6): 689–710. [CrossRef]

- Hodgkinson, Gerard P., Eugene Sadler-Smith, Lisa A. Burke, Guy Claxton, and Paul R. Sparrow. 2009. “Intuition in Organizations: Implications for Strategic Management.” Long Range Planning 42 (3): 277–97. [CrossRef]

- Hookway, Christopher. 2008. “Pragmatism.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2008. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/pragmatism/.

- Ihde, D. 1990. Technology and the Lifeworld: From Garden to Earth. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Jacobides, Michael G., Carmelo Cennamo, and Annabelle Gawer. 2018. “Towards a Theory of Ecosystems.” Strategic Management Journal 39 (8): 2255–76. [CrossRef]

- Jaspers, K. 1961. Die Atombombe Und Die Zukunft Des Menschen. Müchen: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag.

- Jones, Alister, Cathy Buntting, and Marc J. De Vries. 2013. “The Developing Field of Technology Education: A Review to Look Forward.” International Journal of Technology and Design Education 23 (2): 191–212. [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, Rahul, and Joon Mahn Lee. 2013. “Coordinating and Competing in Ecosystems: How Organizational Forms Shape New Technology Investments.” Strategic Management Journal 34 (3): 274–96. [CrossRef]

- Karczmarczyk, Pedro. 2013. “La Ruptura Epistemológica, de Bachelard a Balibar y Pêcheux.” Estudios de Epistemología, no. 10: 9–33.

- Koch, Chistof. 2012. Consciousness. Confessions of a Romantic Reductionist. Cambridge, Massachusetts, London: The MIT Press.

- Kuhn, Thomas S. 1970. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. 2nd Editio. Vol. II. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Kwan, Letty Y.Y., Angela K.y. Leung, and Shyhnan Liou. 2018. “Culture, Creativity, and Innovation.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 49 (2): 165–70. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Albert. 1992. “Reviewed Work: Critical Theory of Technology. by Andrew Feenberg.” Edited by K.B Olsen, J, S.A. Pedersen, and V.F. Hendricks. MLN 107 (5): 1032–35. [CrossRef]

- Markley, Oliver. 2015. “Learning to Use Intuition in Futures Studies: A Bibliographic Essay on Personal Sources, Processes and Concerns.” Journal of Futures Studies 20 (1): 119–30. [CrossRef]

- Mitcham, Carl. 1994. Thinking through Technology. Te Path between Engineering and Philosophy. Chicago: Chicago University.

- Pitt, Joseph C. 2011. Doing Philosophy of Technology. Edited by P. Vermaas. Vol. 3. Philosophy of Engineering and Technology. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. [CrossRef]

- Polanyi, Michael. 1966. The Tacit Dimension. London, Routledge: University of Chicago Press.

- Rahman, Airini Ab, Umar Zakir, Abdul Hamid, and Thoo Ai Chin. 2017. “Emerging Technologies With Disruptive Effects: A Review.” Perintis EJournal 7 (2): 111–28.

- Ramirez, R., K. Van Der Heijden, and J.W. Selsky. 2008. Business Planning for Turbulent Times. New Methods for Applying Scenarios. Business Planning for Turbulent Times. Trowbridge: Cromwell Press. http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=w4t8T2Q8v68C&oi=fnd&pg=PR5&dq=Business+Planning+for+Turbulent+Times&ots=yhGqnoiF12&sig=QyI_svlX0OzS8MpHDhnLsrekC7U.

- Rip, A., and R. Kemp. 1998. “Technological Change.” In Human Choice and Climate Change, 327–99. Ohio. Volume 2, Ch: Battelle Press.

- Roland Ortt, J., David J. Langley, and Nico Pals. 2007. “Exploring the Market for Breakthrough Technologies.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 74 (9): 1788–1804. [CrossRef]

- Rosenbloom, Daniel, and James Meadowcroft. 2014. “The Journey towards Decarbonization: Exploring Socio-Technical Transitions in the Electricity Sector in the Province of Ontario (1885-2013) and Potential Low-Carbon Pathways.” Energy Policy 65 (February): 670–79. [CrossRef]

- Schot, Johan, and Frank W Geels. 2008. “Strategic Niche Management and Sustainable Innovation Journeys: Theory, Findings, Research Agenda, and Policy.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 20 (5): 537–54. [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, JA. 1942. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. New York: Harper.

- Schweizer. 1993. “Mind / Consciousness Dualism in Sankhya-Yoga Philosophy.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 53 (4): 845–59. [CrossRef]

- Sikka, Tina. 2012. “A Critical Theory of Technology Applied to the Public Discussion of Geoengineering.” Technology in Society 34 (2): 109–17. [CrossRef]

- Slaughter, Richard a. 1998. “Futures beyond Dystopia.” Futures 30 (10): 993–1002. [CrossRef]

- Smith, Daniel Woodruf. 2013. “Phenomenology.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2013. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/phenomenology/.

- Talwar, S.D. 2004. “Yoga: Attainment of Ultimate Reality and Meaning.” Ultimate Reality and Meaning 27 (1): 3–28.

- Tononi, Giulio, and Gerald M Edelman. 1998. “Consciousness and Complexity.” Science 282 (5395): 1846–51. [CrossRef]

- Turnheim, Bruno, and Frank W. Geels. 2012. “Regime Destabilisation as the Flipside of Energy Transitions: Lessons from the History of the British Coal Industry (1913-1997).” Energy Policy 50: 35–49. [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Oliva, Silvia. 2018. “La Impresión 3D Como Tecnología de Uso General En El Futuro.” Economía Industrial 407: 123–35.

- Vinge, Vernor. 1993. “The Coming Technological Singularity: How to Survive in the Post-Human Era.” Vision-21: Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering in the Era of Cyberspace 10129: 11–22. http://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19940022855_1994022855.pdf%5Cnhttp://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=19940022855&hterms=CP-10129.

- Vries, Marc J. De. 2005. “The Nature of Technological Knowledge: Philosophical Reflections and Educational Consequences.” International Journal of Technology and Design Education 15 (2): 149–54. [CrossRef]

- Winner, L. 1973. Autonomous Technology and Political Thought. University of California, Berkeley.

- Winter, M, C Smith, P Morris, and S Cicmil. 2006. “Directions for Future Research in Project Management: The Main Findings of a UK Government-Funded Research Network.” International Journal of Project Management 24 (8): 638–49. [CrossRef]

- Woensel, Van, and Geoff Archer. 2015. “Ten Technologies Which Could Change Our Lives: Potential Impacts and Policy Implications.”.

- Yusuf, Shahid. 2009. “From Creativity to Innovation.” Technology in Society 31 (1): 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Qin. 2009. “Book Review: Pragmatism as Post-Postmodernism: Lessons from John Dewey by Larry A. Hickman.” Techné 13 (2): 172–74.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).