Submitted:

21 July 2024

Posted:

22 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

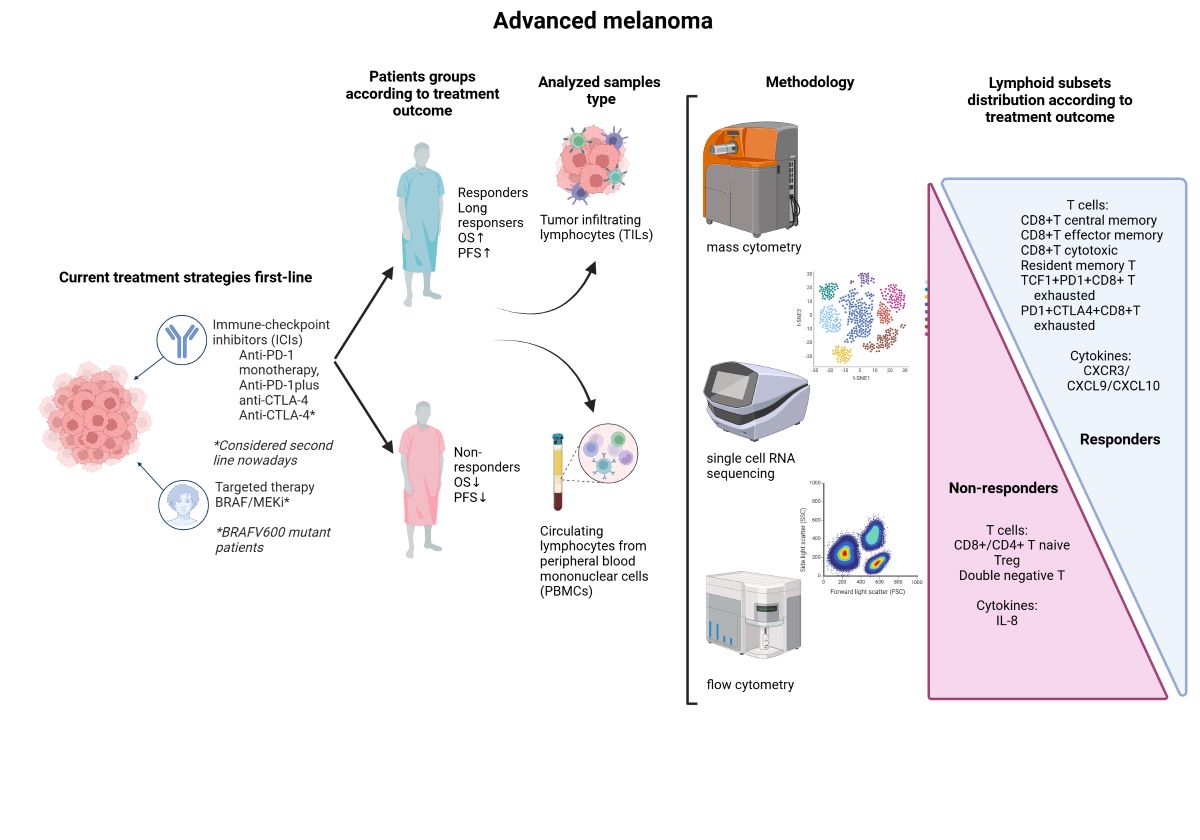

1. Introduction

2. Lymphoid Populations and Outcomes of Melanoma Patients Treated with ICI

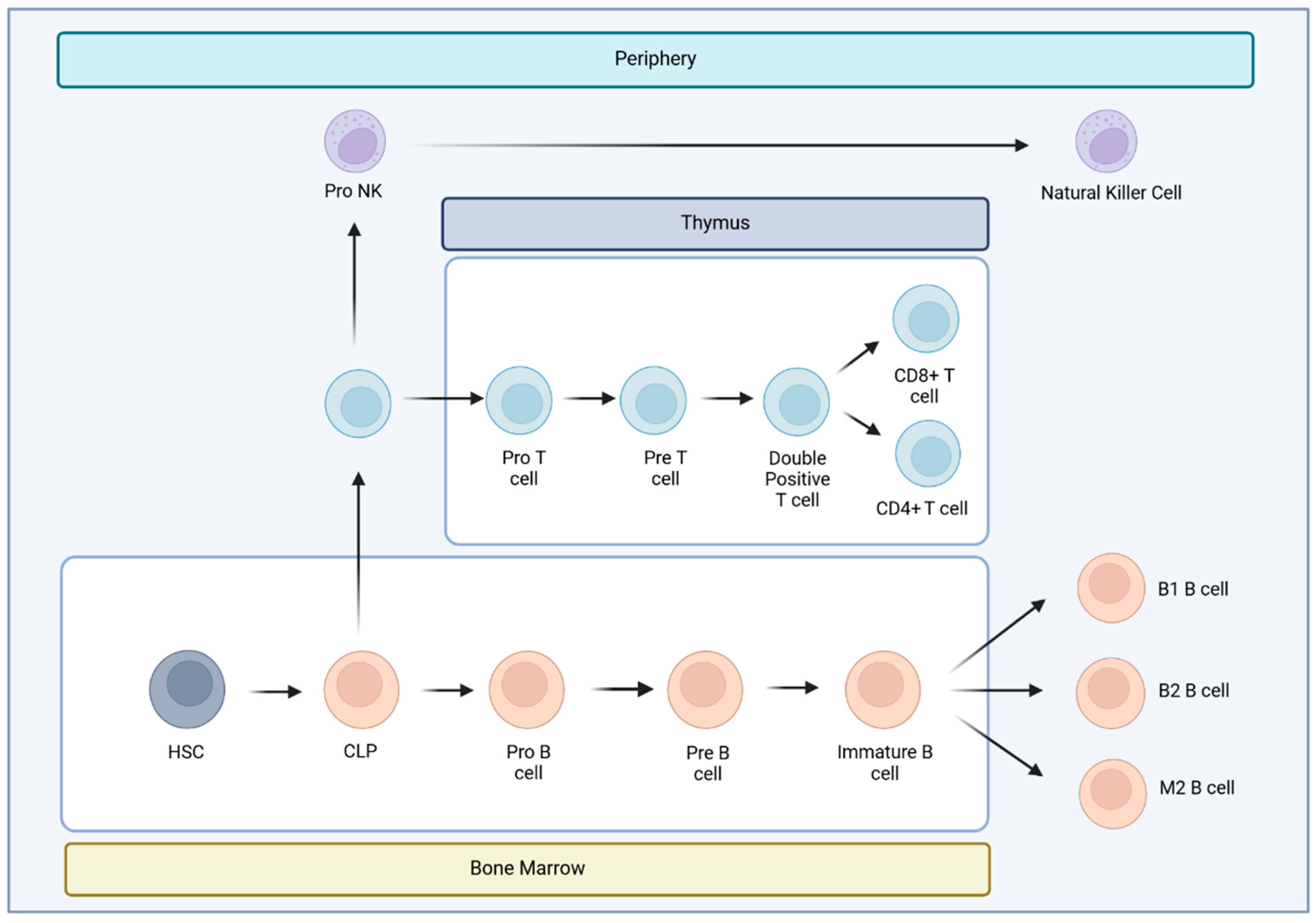

2.1. Lymphoid T Populations

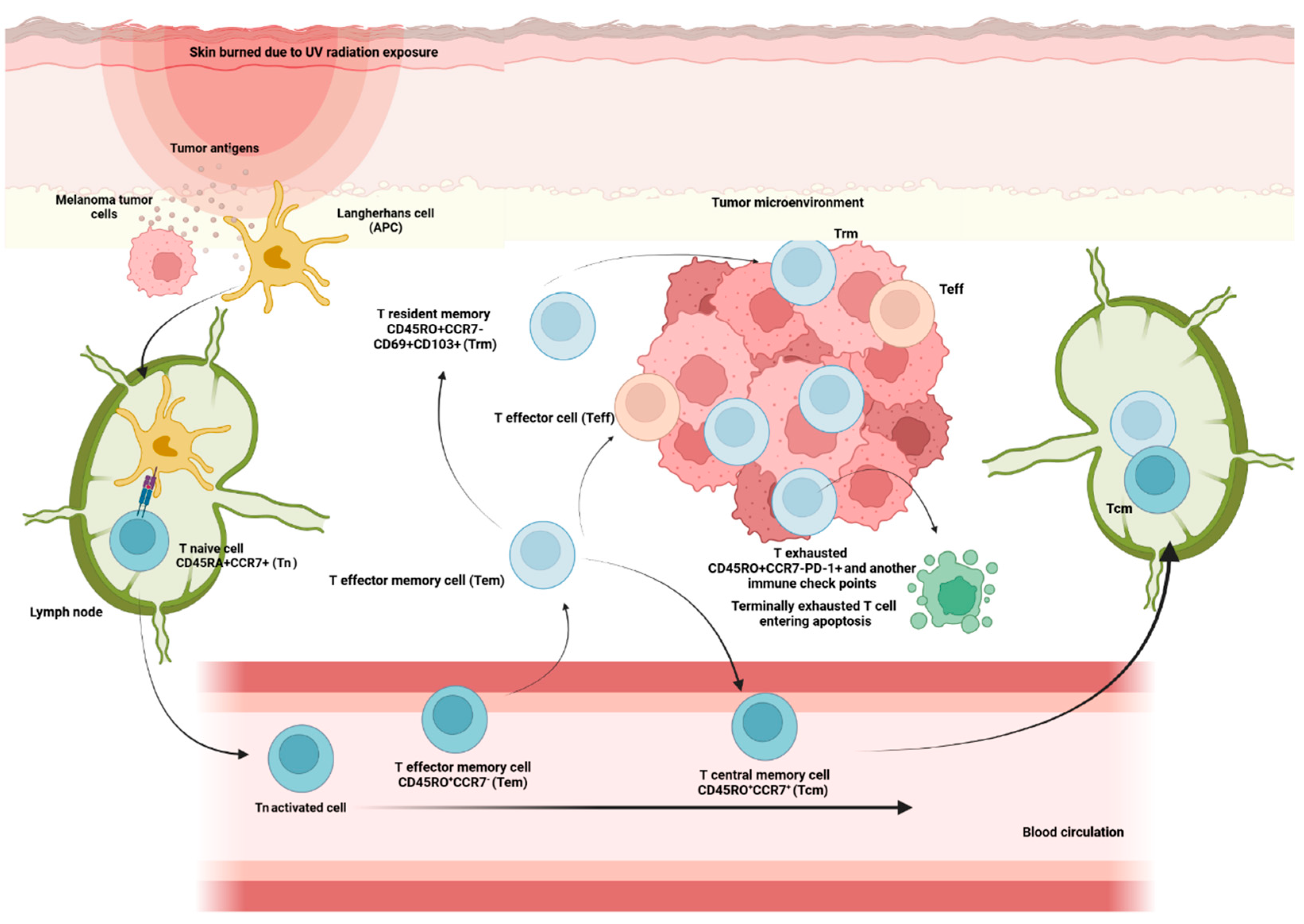

2.1.1. Memory Compartment from Lymphoid T Cell Population

2.1.2. CD4+T Cells

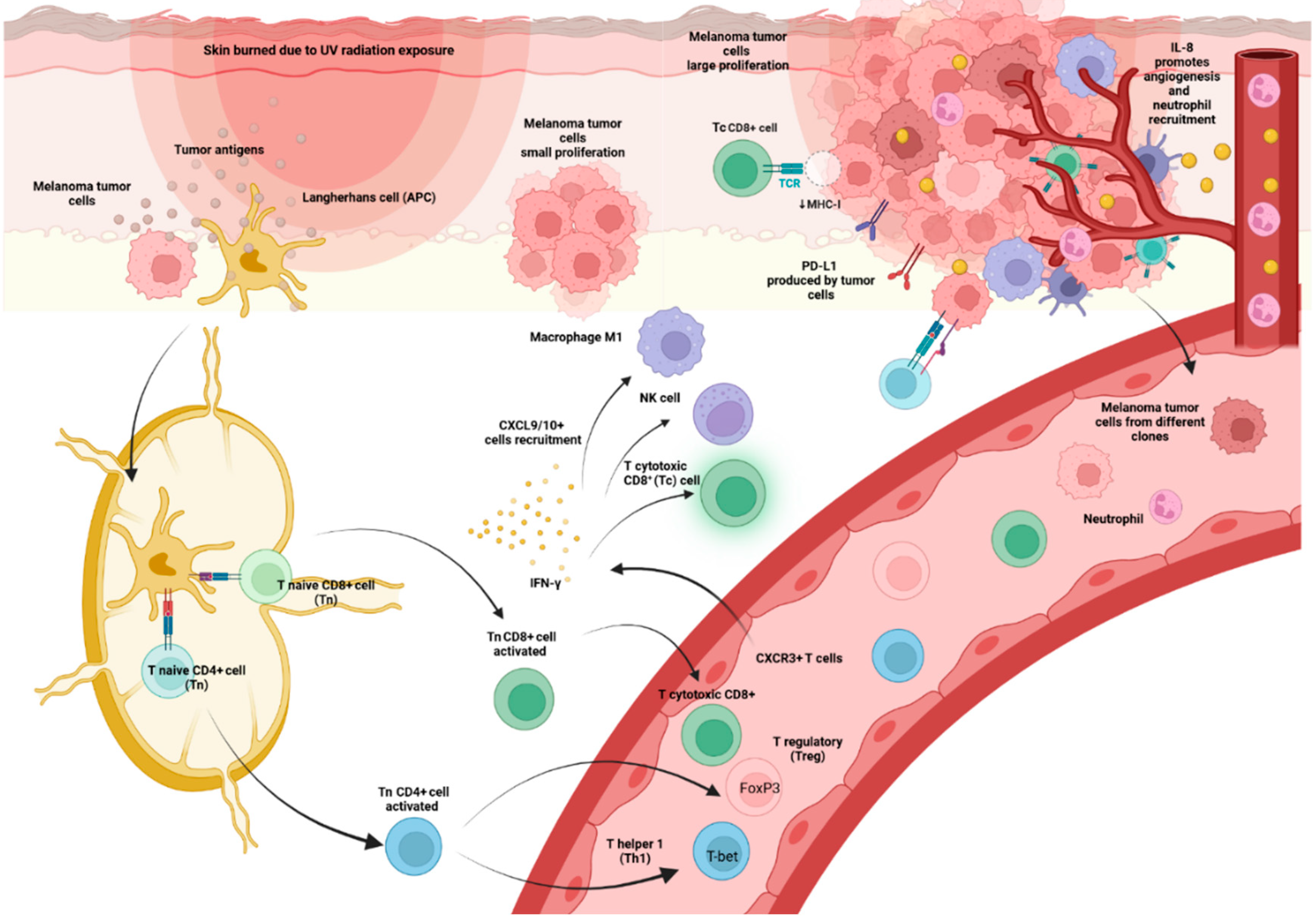

2.1.3. CD8+T Cells

2.1.4. Dysfunctional Programs: From T Progenitor Exhausted to Terminally Exhausted and Reinvigoration

2.1.5. Transcription Factors and Encoding Genes Regulators of Lymphoid T Cell Populations

2.1.6. Double Negative T Cells (DNTs)

2.2. Chemokines and Outcomes of Melanoma Patients Treated with ICI

2.3. Distinct Effects of Anti-CTLA-4 and Anti-PD-1 on Lymphoid Populations

3. Discussion

| Lymphoid cell population | Patients population | Observation | Ref* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T cell | Memory populations | Tn CD4+ | Stage III melanoma | ↑ in worse PFS | [20] |

| Locally advanced melanoma treated with neoadjuvant ipilimumab (IPI) | ↓ after treatment | [21] | |||

| Tn CD8+ | MM treated with Pembrolizumab (PEM) | ↓ in responders | [25] | ||

| Tcm CD8+ | ↑ in responders | ||||

| MM treated with IPI | ≥13% Tcm CD8+ in long responders | [29] | |||

| Tcm | MM treated with IPI | ↑ in patients (pts) with DC | [23] | ||

| Tem | |||||

| Tem CD8+ | ↑ in pts with DC | ||||

| MM treated with NIVO or PEM or NIVO+IPI | ↑ after 3 weeks in responders | [28] | |||

| Tem CD4+ | MM treated with nivolumab (NIVO) + IPI | ↑ in better PFS | [24] | ||

| MM treated with PEM | ↓ in responders | [25] | |||

| CX3CR1+CD8+ | Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with NIVO | ↑ better ORR, PFS and OS | [26] | ||

| Tcm/Teff | MM and NSCLC treated with NIVO | ↑ better PFS | [30] | ||

| Trm CD8+ | MC38-OVA and B16-OVA melanoma in murine model | ↓ tumor growth in conjuntion with anti-PD-1 | [32] | ||

| MM treated with anti-PD-1 | ↑ in responders | ||||

| MM treated with anti-PD-1 | ↑ better melanoma specific survival and ORR | [35] | |||

| Advanced resectable melanoma | ↑ better RFS | [37] | |||

| CD4+ | Th1 and Th2 | B16 melanoma in murine model | ↓ tumor growth | [40] | |

| Th1 | Spontaneously regressing tumours | ↑ Th1 genes expression | [41] | ||

| Th17 | MM treated with IPI +/- HLA-A*0201 | ↑ better RFS | [42] | ||

| Treg | MM treated with IPI | ↓ after treatment | [51] | ||

| MM treated with IPI | Lower Treg expression better RFS | [55] | |||

| PD-1+Treg | MM treated with PEM | Significant ↓ after 1rst cycle was predictor of PFS and Melanoma specific death | [63] | ||

| Teff/Treg | MM patients | ↑ associated with better OS | [50] | ||

| MM treated with IPI | ↑ was related to tumor necrosis | [53] | |||

| MM treated with PEM or NIVO | ↑ ratio | [61] | |||

| MM treated with combined anti-PD1+anti-CTLA-4 | ↑ within the tumor | [48] | |||

| CD8+ | Intratumoral CD8+ | MM treated with PEM | ↑ density at the invasive margin in responders | [65] | |

| CD8+ | MM treated with PEM or NIVO | ↑ PFS and ORR | [76] | ||

| CD8+Tc | MM treated with anti-PD-1 alone or with anti-CTLA-4 | ↑ORR | [66] | ||

| CD8+Teff | MM treated with IPI | ↑ associated with DC | [23] | ||

| DNTs | CD4-CD8-CD56- | MM treated with anti-PD-1 alone or anti-CTLA-4 | ↓ in responders | [90,110] | |

| Dysfunctional programs | TCF1+PD-1+CD8+ | MM treated with NIVO plus IPI | ↑ among responders and associated with longer response, OS and PFS | [74] | |

| Ki67+PD-1+CTLA-4+CD8+ | MMtreated with PEM | ↑ after treatment | [75] | ||

| CTLA-4+PD-1+CD8+ | MM treated with PEM or NIVO | ↑ associated with better ORR and PFS | [77] | ||

| Ki67+PD-1+CD8+ | MM treated with PEM | ↑ Ki67+PD-1+CD8+to tumor burden ratio associated with better OS, PFS and ORR | [78] | ||

| PD-1hiCTLA-4hiCD8+ | MM treated with ICI | ↑ better ORR, OS and PFS | [80] | ||

| Progenitor Tex/ Terminally exhausted Tex | MM treated with anti-PD-1 | ↑ ratio correlated to ORR | [74] | ||

| Transcription factors | TCF7+CD8+ | MM treated with anti-PD-1, anti-CTLA-4 or combined treatment | ↑ in responders | [83] | |

| TCF7+CD8+/TCF7-CD8+>1 | MM treated with anti-PD-1 | ↑ in responders | [83] | ||

| EomeshiT-BEThiCD8+ | MM treated with anti-CTLA-4 | ↑ after treatment | [36,88,89] | ||

| Eomes+CD69+CD45RO+Tem | MM treated with anti-PD-1, anti-CTLA-4 or combined treatment | ↑ better response and longer PFS | |||

| Ki67+Eomes+CD8+ | MM treated with IPI | ↓ baseline level associated with relapse | [88] | ||

| Cytokines | CXCR3+CD8+ | MM treated with PEM | Marked increase and decrease after second infusion in responders | [94] | |

| MM | ↑ better OS | [95] | |||

| CXCL9 and CXCL10 | MM treated with PEM or IPI+NIVO | ↑in responders | [96] | ||

| MM treated with anti-PD-1 alone or with anti-CTLA-4 | ↑intratumoral expression in responders and longer OS | [97] | |||

| IL-8 | MM patients treated with PEMBRO or NIVO alone or with IPI | ↓ levels in responders | [106] | ||

| Early ↓ associated with better OS | |||||

| MM treated with IPI or iBRAF | Positive correlation with tumor burden and negative with ORR and OS | [107] | |||

4. Conclusion

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021 Jan;71(1):7-33. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21654. Epub 2021 Jan 12. Erratum in: CA Cancer J Clin. 2021 Jul;71(4):359. [CrossRef]

- Michielin O van Akkooi, A.C.J. Ascierto, P. A. Dummer, R., Keilholz, U. Cutaneous melanoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1884–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixidó, C.; González-Cao, M.; Karachaliou, N.; Rosell, R. Predictive factors for immunotherapy in melanoma. Ann Transl Med. 2015 Sep;3(15):208. [CrossRef]

- Hodi, F.S.; O’Day, S.J.; McDermott, D.F.; Weber, R.W.; Sosman, J.A.; Haanen, J.B.; Gonzalez, R.; Robert, C.; Schadendorf, D.; Hassel, J.C.; et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma, N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, C.; Thomas, L.; Bondarenko, I.; O’Day, S.; Weber, J.; Garbe, C.; Lebbe, C.; Baurain, J.F.; Testori, A.; Grob, J.J.; et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma, N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 2517–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ascierto, P.A.; Long, G.V.; Robert, C.; Brady, B.; Dutriaux, C.; Di Giacomo, A.M.; Mortier, L.; Hassel, J.C.; Rutkowski, P.; McNeil, C.; Kalinka-Warzocha, E.; Savage, K.J.; Hernberg, M.M.; Lebbé, C.; Charles, J.; Mihalcioiu, C.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Mauch, C.; Cognetti, F.; Ny, L.; Arance, A.; Svane, I.M.; Schadendorf, D.; Gogas, H.; Saci, A.; Jiang, J.; Rizzo, J.; Atkinson, V. Survival Outcomes in Patients With Previously Untreated BRAF Wild-Type Advanced Melanoma Treated With Nivolumab Therapy: Three-Year Follow-up of a Randomized Phase 3 Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Feb 1;5(2):187-194. [CrossRef]

- Hamid, O.; Robert, C.; Daud, A.; Hodi, F.S.; Hwu, W.J.; Kefford, R.; Wolchok, J.D.; Hersey, P.; Joseph, R.; Weber, J.S. , et al. Five-year survival outcomes for patients with advanced melanoma treated with pembrolizumab in KEYNOTE-001. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolchok, J.D.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; Rutkowski, P.; Grob, J.J.; Cowey, C.L.; Lao, C.D.; Wagstaff, J.; Schadendorf, D.; Ferrucci, P.F.; et al. Overall Survival with Combined Nivolumab Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma, N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1345–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolchok, J.D.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; Grob, J.J.; Rutkowski, P.; Lao, C.D.; Cowey, C.L.; Schadendorf, D.; Wagstaff, J.; Dummer, R.; Ferrucci, P.F.; Smylie, M.; Butler, M.O.; Hill, A.; Márquez-Rodas, I.; Haanen, J.B.A.G.; Guidoboni, M.; Maio, M.; Schöffski, P.; Carlino, M.S.; Lebbé, C.; McArthur, G.; Ascierto, P.A.; Daniels, G.A.; Long, G.V.; Bas, T.; Ritchings, C.; Larkin, J.; Hodi, F.S. Long-Term Outcomes With Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab or Nivolumab Alone Versus Ipilimumab in Patients With Advanced Melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2022, Jan 10;40(2):127-13m7. [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, T.N.; Schreiber, R.D. Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science. 2015, 348:69–74 154. [CrossRef]

- Azimi, F.; Scolyer, R.A.; Rumcheva, P.; Moncrieff, M.; Murali, R.; McCarthy, S.W.; Saw, R.P.; Thompson, J.F. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte grade is an independent predictor of sentinel lymph node status and survival in patients with cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012, 30:2678–2683. [CrossRef]

- Ladányi, A. Prognostic and predictive significance of immune cells infiltrating cutaneous melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2015, Sep,28(5):490-500. [CrossRef]

- Anichini, A.; Vegetti, C.; Mortarini, R. The paradox of T cell–mediated antitumor immunity in spite of poor clinical outcome in human melanoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2004, 53, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogunovic, D.; O’Neill, D.W.; Belitskaya-Levy, I. Immune profile and mitotic index of metastatic melanoma lesions enhance clinical staging in predicting patient survival. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2009, 106, 20429–20434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brummelman, J.; Pilipow, K.; Lugli, E. The Single-Cell Phenotypic Identity of Human CD8+ and CD4+ T Cells. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2018, 341:63-124. [CrossRef]

- Maecker, H.T.; McCoy, J.P.; Nussenblatt, R. Standardizing immunophenotyping for the Human Immunology Project. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012, Feb 17,12(3):191-200. [CrossRef]

- Clark, W.H., Jr.; Elder, D.E.; Guerry, D.I.V.; Braitman, L.E.; Trock, B.J.; Schultz, D.; Synnestvedt, M.; Halpern, A.C. Model predicting survival in stage I melanoma based on tumor progression. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 1989, 81, 1893–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senovilla, L.; Vacchelli, E.; Galon, J.; et al. Prognostic and predictive value of the immune infiltrate in cancer. OncoImmunology. 2012, 1, 1323–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taniuchi, I. Views on helper/cytotoxic lineage choice from a bottom-up approach. Immunol Rev. 2016, 271:98–113. [CrossRef]

- Jacquelot, N.; Roberti, M.P.; Enot, D.P.; Rusakiewicz, S.; Semeraro, M.; Jégou, S.; et al. Immunophenotyping of stage III melanoma reveals parameters associated with patient prognosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2016, 136, 994–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarhini, A.A.; Edington, H.; Butterfield, L.H.; Lin, Y.; Shuai, Y.; Tawbi, H.; Sander, C.; Yin, Y.; Holtzman, M.; Johnson, J.; Rao, U.N.; Kirkwood, J.M. Immune monitoring of the circulation and the tumor microenvironment in patients with regionally advanced melanoma receiving neoadjuvant ipilimumab. PLoS One. 2014, Feb 3,9(2):e87705. [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.S.; Hamid, O.; Chasalow, S.D.; Wu, D.Y.; Parker, S.M.; Galbraith, S.; Gnjatic, S.; Berman, D. Ipilimumab increases activated T cells and enhances humoral immunity in patients with advanced melanoma. J Immunother. 2012 Jan;35(1):89-97. [CrossRef]

- Felix, J.; Lambert, J.; Roelens, M.; Maubec, E.; Guermouche, H.; Pages, C.; Sidina, I.; Cordeiro, D.J.; Maki, G.; Chasset, F.; Porcher, R.; Bagot, M.; Caignard, A.; Toubert, A.; Lebbé, C.; Moins-Teisserenc, H. Ipilimumab reshapes T cell memory subsets in melanoma patients with clinical response. Oncoimmunology. 2016, Feb 18,5(7):1136045. [CrossRef]

- Kverneland, A.H.; Thorsen, S.U.; Granhøj, J.S.; Hansen, F.S.; Konge, M.; Ellebæk, E.; Donia, M.; Svane, I.M. Supervised clustering of peripheral immune cells associated with clinical response to checkpoint inhibitor therapy in patients with advanced melanoma. Immunooncol Technol. 2023 Aug 24;20:100396. [CrossRef]

- Krieg, C.; Nowicka, M.; Guglietta, S.; Schindler, S.; Hartmann, F.J.; Weber, L.M.; Dummer, R.; Robinson, M.D.; Levesque, M.P.; Becher, B. High-dimensional single-cell analysis predicts response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Nat Med. 2018 Feb;24(2):144-153. Epub 2018 Jan 8. Erratum in: Nat Med. 2018 Nov;24(11):1773-1775. [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, T.; Hoki, T.; Oba, T.; Jain, V.; Chen, H.; Attwood, K.; Battaglia, S.; George, S.; Chatta, G.; Puzanov, I.; Morrison, C.; Odunsi, K.; Segal, B.H.; Dy, G.K.; Ernstoff, M.S.; Ito, F. T cell CX3CR1 expression as a dynamic blood-based biomarker of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Commun. 2021, Mar 3,12(1):1402. [CrossRef]

- Ribas, A.; Shin, D.S.; Zaretsky, J.; Frederiksen, J.; Cornish, A.; Avramis, E.; Seja, E.; Kivork, C.; Siebert, J.; Kaplan-Lefko, P.; Wang, X.; Chmielowski, B.; Glaspy, J.A.; Tumeh, P.C.; Chodon, T.; Pe'er, D.; Comin-Anduix, B. PD-1 Blockade Expands Intratumoral Memory T Cells. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016 Mar;4(3):194-203. [CrossRef]

- Valpione, S.; Galvani, E.; Tweedy, J.; Mundra, P.A.; Banyard, A.; Middlehurst, P.; Barry, J.; Mills, S.; Salih, Z.; Weightman, J.; Gupta, A.; Gremel, G.; Baenke, F.; Dhomen, N.; Lorigan, P.C.; Marais, R. Immune-awakening revealed by peripheral T cell dynamics after one cycle of immunotherapy. Nat Cancer. 2020 Feb;1(2):210-221. [CrossRef]

- Wistuba-Hamprecht, K.; Martens, A.; Heubach, F.; Romano, E.; Geukes Foppen, M.; Yuan, J.; Postow, M.; Wong, P.; Mallardo, D.; Schilling, B.; Di Giacomo, A.M.; Khammari, A.; Dreno, B.; Maio, M.; Schadendorf, D.; Ascierto, P.A.; Wolchok, J.D.; Blank, C.U.; Garbe, C.; Pawelec, G.; Weide, B. Peripheral CD8 effector-memory type 1 T cells correlate with outcome in ipilimumab-treated stage IV melanoma patients. Eur J Cancer. 2017 Mar;73:61-70. [CrossRef]

- Manjarrez-Orduño, N.; Menard, L.C.; Kansal, S.; Fischer, P.; Kakrecha, B.; Jiang, C.; Cunningham, M.; Greenawalt, D.; Patel, V.; Yang, M.; Golhar, R.; Carman, J.A.; Lezhnin, S.; Dai, H.; Kayne, P.S.; Suchard, S.J.; Bernstein, S.H.; Nadler, S.G. Circulating T Cell Subpopulations Correlate With Immune Responses at the Tumor Site and Clinical Response to PD1 Inhibition in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Front Immunol. 2018, Aug 3,9:1613. [CrossRef]

- Sabat, R.; Wolk, K.; Loyal, L.; Döcke, W.D.; Ghoreschi, K. T cell pathology in skin inflammation. Semin Immunopathol. 2019 May,41(3):359-377. [CrossRef]

- Blanc, C.; Hans, S.; Tran, T.; Granier, C.; Saldman, A.; Anson, M.; Oudard, S.; Tartour, E. Targeting Resident Memory T Cells for Cancer Immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2018, Jul 27,9:1722. [CrossRef]

- Boddupalli, C.S.; Bar, N.; Kadaveru, K.; Krauthammer, M.; Pornputtapong, N.; Mai, Z.; Ariyan, S.; Narayan, D.; Kluger, H.; Deng, Y.; Verma, R.; Das, R.; Bacchiocchi, A.; Halaban, R.; Sznol, M.; Dhodapkar, M.V.; Dhodapkar, K.M. Interlesional diversity of T cell receptors in melanoma with immune checkpoints enriched in tissue-resident memory T cells. JCI Insight. 2016 Dec 22;1(21):e88955. [CrossRef]

- Enamorado, M.; Iborra, S.; Priego, E.; Cueto, F.J.; Quintana, J.A.; Martinez-Cano, S.; et al. Enhanced anti-tumor immunity requires the interplay between resident and circulating memory CD8(+) T cells. Nat Commun (2017) 8:16073. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.; Wilmott, J.S.; Madore, J.; Gide, T.N.; Quek, C.; Tasker, A.; Ferguson, A.; Chen, J.; Hewavisenti, R.; Hersey, P.; Gebhardt, T.; Weninger, W.; Britton, W.J.; Saw, R.P.M.; Thompson, J.F.; Menzies, A.M.; Long, G.V.; Scolyer, R.A.; Palendira, U. CD103+ Tumor-Resident CD8+ T Cells Are Associated with Improved Survival in Immunotherapy-Naïve Melanoma Patients and Expand Significantly During Anti-PD-1 Treatment. Clin Cancer Res. 2018, Jul 1,24(13):3036-3045. [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.C.; Levine, J.H.; Cogdill, A.P.; Zhao, Y.; Anang, N.A.S.; Andrews, M.C., et al. Distinct cellular mechanisms underlie anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 checkpoint blockade. Cell. 2017, 170(6):1120–33.e17. [CrossRef]

- Attrill, G.H.; Owen, C.N.; Ahmed, T.; Vergara, I.A.; Colebatch, A.J.; Conway, J.W.; Nahar, K.J.; Thompson, J.F.; Pires da Silva, I.; Carlino, M.S.; Menzies, A.M.; Lo, S.; Palendira, U.; Scolyer, R.A.; Long, G.V.; Wilmott, J.S. Higher proportions of CD39+ tumor-resident cytotoxic T cells predict recurrence-free survival in patients with stage III melanoma treated with adjuvant immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2022 Jun;10(6):e004771. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-J.; Cantor, H. CD4 T cell subsets and tumor immunity: the helpful and the not-so-helpful. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014, 2:91–8. [CrossRef]

- Erdag, G.; Schaefer, J.T.; Smolkin, M.E.; Deacon, D.H.; Shea, S.M.; Dengel, L.T. Immunotype and immunohistologic characteristics of tumor infiltrating immune cells are associated with clinical outcome in metastatic melanoma. Cancer Res. 2012, 72:1070–80. [CrossRef]

- Eftimie, R.; Hamam, H. Modelling and investigation of the CD4+ T cells – macrophages paradox in melanoma immunotherapies. J Theor Biol. 2017, 420:82–104. [CrossRef]

- Lowes, M.A.; Bishop, G.A.; Crotty, K.; Barnetson, R.S.C.; Halliday, G.M. T helper 1 cytokine mRNA is increased in spontaneously regressing primary melanomas. J Invest Dermatol. 1997, 108:914–9. [CrossRef]

- Sarnaik, A.; Yu, B.; Yu, D.; Morelli, D.; Hall, M.; Bogle, D.; Yan, L.; Targan, S.; Solomon, J.; Nichol, G.; Yellin, M.; Weber, J.S. Extended dose ipilimumab with a peptide vaccine: immune correlates associated with clinical benefit in patients with resected high-risk stage IIIc/IV melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011, Feb 15,17(4):896-906. [CrossRef]

- Dulos, J.; Carven, G.J.; van Boxtel, S.J.; Evers, S.; Driessen-Engels, L.J.; Hobo, W.; Gorecka, M.A.; de Haan, A.F.; Mulders, P.; Punt, C.J.; Jacobs, J.F.; Schalken, J.A.; Oosterwijk, E.; van Eenennaam, H.; Boots, A.M. PD-1 blockade augments Th1 and Th17 and suppresses Th2 responses in peripheral blood from patients with prostate and advanced melanoma cancer. J Immunother. 2012, Feb-Mar;35(2):169-78. [CrossRef]

- Josefowicz, S.Z.; Lu, L.F.; Rudensky, A.Y. Regulatory T cells: mechanisms of differentiation and function. Annual Rev Immunol. 2012, 30: 531–564. [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, S.; Takahashi, T.; Nishizuka, Y. Study on cellular events in postthymectomy autoimmune oophoritis in mice. I. Requirement of Lyt-1 effector cells for oocytes damage after adoptive transfer. J Exp Med 1982, 156, 1565–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, L.; Bergmann, C.; Szczepanski, M.; Gooding, W.; Johnson, J.T.; Whiteside, T.L. A unique subset of CD4+CD25highFoxp3+ T cells secreting interleukin-10 and transforming growth factor-beta1 mediates suppression in the tumor microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res. 2007, 13(15):4345–4354. [CrossRef]

- Callahan, M.K.; Postow, M.A.; Wolchok, J.D. CTLA-4 and PD-1 pathway blockade: combinations in the clinic. Front Oncol. 2014, 4: 385. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, A.; Sakaguchi, S. Targeting Treg cells in cancer immunotherapy. Eur J Immunol. 2019 Aug;49(8):1140-1146. [CrossRef]

- Nizar, S.; Meyer, B.; Galustian, C.; Kumar, D.; Dalgleish, A. T regulatory cells, the evolution of targeted immunotherapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010, 1806:7–17. [CrossRef]

- Quezada, S.A.; Peggs, K.S.; Curran, M.A.; Allison, J.P. CTLA4 blockade and GM-CSF combination immunotherapy alters the intratumor balance of effector and regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest. 2006, 116:1935–1945. [CrossRef]

- Selby, M.J.; Engelhardt, J.J.; Quigley, M.; Henning, K.A.; Chen, T.; Srinivasan, M.; Korman, A.J. Anti-CTLA-4 antibodies of IgG2a isotype enhance antitumor activity through reduction of intratumoral regulatory T cells. Cancer Immunol Res. 2013, Jul,1(1):32-42. [CrossRef]

- Simpson, T.R.; Li, F.; Montalvo-Ortiz, W., et al. Fc dependent depletion of tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells co-defines the efficacy of anti-CTLA-4 therapy against melanoma. J Exp Med. 2013, 210: 1695–1710. [CrossRef]

- Hodi, F.S.; Butler, M.; Oble, D.A.; Seiden, M.V.; Haluska, F.G.; Kruse, A., et al. Immunologic and clinical effects of antibody blockade of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 in previously vaccinated cancer patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008,105:3005–10. [CrossRef]

- Ouwerkerk, W.; van den Berg, M.; van der Niet, S.; Limpens, J.; Luiten, R.M. Biomarkers, measured during therapy, for response of melanoma patients to immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review. Melanoma Res. 2019, Oct, 29(5):453-464. [CrossRef]

- Retseck, J.; Nasr, A.; Lin, Y.; Lin, H.; Mendiratta, P.; Butterfield, L.H.; Tarhini, A.A. Long term impact of CTLA4 blockade immunotherapy on regulatory and effector immune responses in patients with melanoma. J Transl Med. 2018, Jul 4,16(1):184. [CrossRef]

- von Herrath, M.G.; Harrison, L.C. Antigen-induced regulatory T cells in autoimmunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003, 3:223–232. [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, Y.; Nishikawa, H. Roles of regulatory T cells in cancer immunity. Int Immunol. 2016, Aug,28(8):401-9. [CrossRef]

- Charoentong, P.; Finotello, F.; Angelova, M.; Mayer, C.; Efremova, M.; Rieder, D.; Hackl, H.; Trajanoski, Z. Pan-cancer Immunogenomic Analyses Reveal Genotype-Immunophenotype Relationships and Predictors of Response to Checkpoint Blockade. Cell Rep. 2017, Jan 3,18(1):248-262. [CrossRef]

- Overacre-Delgoffe, A.E.; Vignali, D.A.A. Treg Fragility: A Prerequisite for Effective Antitumor Immunity? Cancer Immunol Res. 2018, Aug,6(8):882-887. [CrossRef]

- Overacre-Delgoffe, A.E.; Chikina, M.; Dadey, R.E.; Yano, H.; Brunazzi, E.A.; Shayan, G., et al. Interferon-g drives Treg fragility to promote anti-tumor immunity. Cell 2017,169:1130–41e11. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Lau, R.; Yu, D.; Zhu, W.; Korman, A.; Weber, J. PD1 blockade reverses the suppression of melanoma antigen-specific CTL by CD4+ CD25(Hi) regulatory T cells. Int Immunol 2009, 21: 1065–1077. [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Park, J.S.; Jeong, Y.H.; et al. PD-1 upregulated on regulatory T cells during chronic virus infection enhances the suppression of CD8+ T cell immune response via the interaction with PD-L1 expressed on CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2015, 194(12): p. 5801-11. [CrossRef]

- Gambichler, T.; Schröter, U.; Höxtermann, S.; Susok, L.; Stockfleth, E.; Becker, J.C. Decline of programmed death-1-positive circulating T regulatory cells predicts more favorable clinical outcome of patients with melanoma under immune checkpoint blockade. Br J Dermatol. 2020. May,182(5):1214-1220. [CrossRef]

- Fairfax, B.P.; Taylor, C.A.; Watson, R.A.; Nassiri, I.; Danielli, S.; Fang, H.; Mahé, E.A.; Cooper, R.; Woodcock, V.; Traill, Z.; Al-Mossawi, M.H.; Knight, J.C.; Klenerman, P.; Payne, M.; Middleton, M.R. Peripheral CD8+ T cell characteristics associated with durable responses to immune checkpoint blockade in patients with metastatic melanoma. Nat Med. 2020, Feb;26(2):193-199. [CrossRef]

- Tumeh, P.C.; Harview, C.L.; Yearley, J.H.; Shintaku, I.P.; Taylor, E.J.; Robert, L.; Chmielowski, B.; Spasic, M.; Henry, G.; Ciobanu, V.; West, A.N.; Carmona, M.; Kivork, C.; Seja, E.; Cherry, G.; Gutierrez, A.J.; Grogan, T.R.; Mateus, C.; Tomasic, G.; Glaspy, J.A.; Emerson, R.O.; Robins, H.; Pierce, R.H.; Elashoff, D.A.; Robert, C.; Ribas, A. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature. 2014 Nov 27,515(7528):568-71. [CrossRef]

- Watson, R.A.; Tong, O.; Cooper, R.; Taylor, C.A.; Sharma, P.K.; de Los Aires, A.V.; Mahé, E.A.; Ruffieux, H.; Nassiri, I.; Middleton, M.R.; Fairfax, B.P. Immune checkpoint blockade sensitivity and progression-free survival associates with baseline CD8+ T cell clone size and cytotoxicity. Sci Immunol. 2021 Oct;6(64):eabj8825. [CrossRef]

- Ayers, M.; Lunceford, J.; Nebozhyn, M.; Murphy, E.; Loboda, A.; Kaufman, D.R.; Albright, A.; Cheng, J.D.; Kang, S.P.; Shankaran, V.; Piha-Paul, S.A., et al. IFN-γ-related mRNA profile predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade. J Clin Investig. 2017, 127: 2930–2940. [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Welsh, J.W.; de Groot, P.; Massarelli, E.; Chang, J.Y.; Hess, K.R.; Basu, S.; Curran, M.A.; Cabanillas, M.E.; Subbiah, V.; Fu, S.; Tsimberidou, A.M.; Karp, D.; Gomez, D.R.; Diab, A.; Komaki, R.; Heymach, J.V.; Sharma, P.; Naing, A.; Hong, D.S. Ipilimumab with Stereotactic Ablative Radiation Therapy: Phase I Results and Immunologic Correlates from Peripheral T Cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2017 Mar 15;23(6):1388-1396. [CrossRef]

- Balatoni, T.; Mohos, A.; Papp, E.; Sebestyén, T.; Liszkay, G.; Oláh, J.; Varga, A.; Lengyel, Z.; Emri, G.; Gaudi, I.; Ladányi, A. Tumor-infiltrating immune cells as potential biomarkers predicting response to treatment and survival in patients with metastatic melanoma receiving ipilimumab therapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2018, Jan,67(1):141-151. [CrossRef]

- Fourcade, J.; Sun, Z.; Benallaoua, M.; Guillaume, P.; Luescher, I.F.; Sander, C.; Kirkwood, J.M.; Kuchroo, V.; Zarour, H.M. Upregulation of Tim-3 and PD-1 expression is associated with tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cell dysfunction in melanoma patients. J. Exp. Med. 2010, 207, 2175–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, M.; Wang, C.; Cong, L.; Marjanovic, N.D.; Kowalczyk, M.S.; Zhang, H.; Nyman, J.; Sakuishi, K.; Kurtulus, S.; Gennert, D. , et al. A distinct gene module for dysfunction uncoupled from activation in tumor-infiltrating T cells. Cell. 2016, 166, 1500–1511e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paley, M.A.; Kroy, D.C.; Odorizzi, P.M.; Johnnidis, J.B.; Dolfi, D.V.; Barnett, B.E.; Bikoff, E.K.; Robertson, E.J.; Lauer, G.M.; Reiner, S.L.; Wherry, E.J. Progenitor and terminal subsets of CD8+ T cells cooperate to contain chronic viral infection. Science. 2012 Nov 30;338(6111):1220-5. [CrossRef]

- Im, S.J.; et al. Defining CD8+ T cells that provide the proliferative burst after PD-1 therapy. Nature. 2016. 537, 417–421. [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.C.; Sen, D.R.; Al Abosy, R.; Bi, K.; Virkud, Y.V.; LaFleur, M.W.; Yates, K.B.; Lako, A.; Felt, K.; Naik, G.S.; Manos, M.; Gjini, E.; Kuchroo, J.R.; Ishizuka, J.J.; Collier, J.L.; Griffin, G.K.; Maleri, S.; Comstock, D.E.; Weiss, S.A.; Brown, F.D.; Panda, A.; Zimmer, M.D.; Manguso, R.T.; Hodi, F.S.; Rodig, S.J.; Sharpe, A.H.; Haining, W.N. Subsets of exhausted CD8+ T cells differentially mediate tumor control and respond to checkpoint blockade. Nat Immunol. 2019, Mar,20(3):326-336. [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.C.; Orlowski, R.J.; Xu, X.; Mick, R.; George, S.M.; Yan, P.K.; Manne, S.; Kraya, A.A.; Wubbenhorst, B.; Dorfman, L.; D'Andrea, K.; Wenz, B.M.; Liu, S.; Chilukuri, L.; Kozlov, A.; Carberry, M.; Giles, L.; Kier, M.W.; Quagliarello, F.; McGettigan, S.; Kreider, K.; Annamalai, L.; Zhao, Q.; Mogg, R.; Xu, W.; Blumenschein, W.M.; Yearley, J.H.; Linette, G.P.; Amaravadi, R.K.; Schuchter, L.M.; Herati, R.S.; Bengsch, B.; Nathanson, K.L.; Farwell, M.D.; Karakousis, G.C.; Wherry, E.J.; Mitchell, T.C. A single dose of neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade predicts clinical outcomes in resectable melanoma. Nat Med. 2019 Mar;25(3):454-461. [CrossRef]

- Maibach, F.; Sadozai, H.; Seyed Jafari, S.M.; Hunger, R.E.; Schenk, M. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes and Their Prognostic Value in Cutaneous Melanoma. Front Immunol. 2020. Sep 10,11:2105. [CrossRef]

- Daud, A.I.; Loo, K.; Pauli, M.L.; Sanchez-Rodriguez, R.; Sandoval, P.M.; Taravati, K., et al. Tumor immune profiling predicts response to anti-PD-1 therapy in human melanoma. J Clin Invest. 2016, 126:3447–52. [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.C.; Postow, M.A.; Orlowski, R.J.; Mick, R.; Bengsch, B.; Manne, S.; Xu, W.; Harmon, S.; Giles, J.R.; Wenz, B.; Adamow, M.; Kuk, D.; Panageas, K.S.; Carrera, C.; Wong, P.; Quagliarello, F.; Wubbenhorst, B.; D'Andrea, K.; Pauken, K.E.; Herati, R.S.; Staupe, R.P.; Schenkel, J.M.; McGettigan, S.; Kothari, S.; George, S.M.; Vonderheide, R.H.; Amaravadi, R.K.; Karakousis, G.C.; Schuchter, L.M.; Xu, X.; Nathanson, K.L.; Wolchok, J.D.; Gangadhar, T.C.; Wherry, E.J. T cell invigoration to tumor burden ratio associated with anti-PD-1 response. Nature. 2017, May 4,545(7652):60-65. [CrossRef]

- Kuehm, L.M.; Wolf, K.; Zahour, J.; DiPaolo, R.J.; Teague, R.M. Checkpoint blockade immunotherapy enhances the frequency and effector function of murine tumor-infiltrating T cells but does not alter TCRβ diversity. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2019, Jul,68(7):1095-1106. [CrossRef]

- Kurtulus, S.; Madi, A.; Escobar, G.; Klapholz, M.; Nyman, J.; Christian, E.; Pawlak, M.; Dionne, D.; Xia, J.; Rozenblatt-Rosen, O.; Kuchroo, V.K.; Regev, A.; Anderson, A.C. Checkpoint Blockade Immunotherapy Induces Dynamic Changes in PD-1-CD8+ Tumor-Infiltrating T Cells. Immunity. 2019, Jan 15,50(1):181-194.e6. [CrossRef]

- Marshall, H.T.; Djamgoz, M.B.A. Immuno-oncology: emerging targets and combination therapies. Front Oncol. 2018, 8:315. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Shan, Q.; Xue, H.H. TCF1 in T cell immunity: a broadened frontier. Nat Rev Immunol 2022, 22, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sade-Feldman, M.; Yizhak, K.; Bjorgaard, S.L.; Ray, J.P.; de Boer, C.G.; Jenkins, R.W.; Lieb, D.J.; Chen, J.H.; Frederick, D.T.; Barzily-Rokni, M.; Freeman, S.S.; Reuben, A.; Hoover, P.J.; Villani, A.C.; Ivanova, E.; Portell, A.; Lizotte, P.H.; Aref, A.R.; Eliane, J.P.; Hammond, M.R.; Vitzthum, H.; Blackmon, S.M.; Li, B.; Gopalakrishnan, V.; Reddy, S.M.; Cooper, Z.A.; Paweletz, C.P.; Barbie, D.A.; Stemmer-Rachamimov, A.; Flaherty, K.T.; Wargo, J.A.; Boland, G.M.; Sullivan, R.J.; Getz, G.; Hacohen, N. Defining T Cell States Associated with Response to Checkpoint Immunotherapy in Melanoma. Cell. 2018 Nov 1;175(4):998-1013.e20. [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, A.E.; Jones, T.R.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Clarke, C.; Kang, I.H.; Friman, O.; Guertin, D.A.; Chang, J.H.; Lindquist, R.A.; Moffat, J. , et al. CellProfiler: image analysis software for identifying and quantifying cell phenotypes. Genome Biol. 2006, 7, R100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, I.; Schaeuble, K.; Chennupati, V.; Fuertes Marraco, S.A.; Calderon-Copete, S.; Pais Ferreira, D.; Carmona, S.J.; Scarpellino, L.; Gfeller, D.; Pradervand, S.; Luther, S.A.; Speiser, D.E.; Held, W. Intratumoral Tcf1+PD-1+CD8+ T Cells with Stem-like Properties Promote Tumor Control in Response to Vaccination and Checkpoint Blockade Immunotherapy. Immunity. 2019, Jan 15,50(1):195-211.e10. [CrossRef]

- Jeannet, G.; Boudousquie, C.; Gardiol, N.; Kang, J.; Huelsken, J.; Held, W. Essential role of the Wnt pathway effector Tcf-1 for the establishment of functional CD8 T cell memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010, USA 107, 9777–9782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.C.; Wei, W.Z.; Tomer, Y. Opportunistic autoimmune disorders: from immunotherapy to immune dysregulation. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010, 1183:222-36. [CrossRef]

- McLane, L.M.; Ngiow, S.F.; Chen, Z.; Attanasio, J.; Manne, S.; Ruthel, G.; Wu, J.E.; Staupe, R.P.; Xu, W.; Amaravadi, R.K.; Xu, X.; Karakousis, G.C.; Mitchell, T.C.; Schuchter, L.M.; Huang, A.C.; Freedman, B.D.; Betts, M.R.; Wherry, E.J. Role of nuclear localization in the regulation and function of T-bet and Eomes in exhausted CD8 T cells. Cell Rep. 2021 May 11;35(6):109120. [CrossRef]

- Gide, T.N.; Quek, C.; Menzies, A.M.; Tasker, A.T.; Shang, P.; Holst, J.; Madore, J.; Lim, S.Y.; Velickovic, R.; Wongchenko, M.; Yan, Y.; Lo, S.; Carlino, M.S.; Guminski, A.; Saw, R.P.M.; Pang, A.; McGuire, H.M.; Palendira, U.; Thompson, J.F.; Rizos, H.; Silva, I.P.D.; Batten, M.; Scolyer, R.A.; Long, G.V.; Wilmott, J.S. Distinct Immune Cell Populations Define Response to Anti-PD-1 Monotherapy and Anti-PD-1/Anti-CTLA-4 Combined Therapy. Cancer Cell. 2019, Feb 11,35(2):238-255.e6. [CrossRef]

- Strippoli, S.; Fanizzi, A.; Negri, A.; Quaresmini, D.; Nardone, A.; Armenio, A.; Sciacovelli, A.M.; Massafra, R.; De Risi, I.; De Tullio, G.; Albano, A.; Guida, M. Examining the Relationship between Circulating CD4- CD8- Double-Negative T Cells and Outcomes of Immuno-Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy-Looking for Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets in Metastatic Melanoma. Cells. 2021, Feb 16,10(2):406. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.X.; Young, K. ; Zhang LCD3+CD4-CD8- alphabeta-TCR+ T cell as immune regulatory cell, J. Mol. Med. Berl. 2001, 79, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Acquisto, F.; Crompton, T. CD3+CD4-CD8- (double negative) T cells: Saviours or villains of the immune response? Biochem. Pharmacol. 2011, 82, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delyon, J.; Mateus, C.; Lefeuvre, D.; Lanoy, E.; Zitvogel, L.; Chaput, N., et al. Experience in daily practice with ipilimumab for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma: an early increase in lymphocyte and eosinophil counts is associated with improved survival. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO 2013, 24:1697- 703. [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wang, Y.; Sun, J.; Tan, T.; Cai, X.; Lin, P.; Tan, Y.; Zheng, B.; Wang, B.; Wang, J.; Xu, L.; Yu, Z.; Xu, Q.; Wu, X.; Gu, Y. Role of CXCR3 signaling in response to anti-PD-1 therapy. EBioMedicine. 2019, Oct;48:169-177. [CrossRef]

- Mullins, I.M.; Slingluff, C.L.; Lee, J.K.; Garbee, C.F.; Shu, J.; Anderson, S.G.; Mayer, M.E.; Knaus, W.A.; Mullins, D.W. CXC chemokine receptor 3 expression by activated CD8+ T cells is associated with survival in melanoma patients with stage III disease. Cancer Res. 2004 Nov 1;64(21):7697-701. [CrossRef]

- Chow, M.T.; Ozga, A.J.; Servis, R.L.; Frederick, D.T.; Lo, J.A.; Fisher, D.E.; Freeman, G.J.; Boland, G.M.; Luster, A.D. Intratumoral Activity of the CXCR3 Chemokine System Is Required for the Efficacy of Anti-PD-1 Therapy. Immunity. 2019 Jun 18;50(6):1498-1512.e5. [CrossRef]

- House, I.G.; Savas, P.; Lai, J.; Chen, A.X.Y.; Oliver, A.J.; Teo, Z.L.; Todd, K.L.; Henderson, M.A.; Giuffrida, L.; Petley, E.V.; Sek, K.; Mardiana, S.; Gide, T.N.; Quek, C.; Scolyer, R.A.; Long, G.V.; Wilmott, J.S.; Loi, S.; Darcy, P.K.; Beavis, P.A. Macrophage-Derived CXCL9 and CXCL10 Are Required for Antitumor Immune Responses Following Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Clin Cancer Res. 2020 Jan 15;26(2):487-504. [CrossRef]

- XYang, Y., Chu, Y. Wang, R. Zhang, S. Xiong, Targeted in vivo expression of IFN-gamma-inducible protein 10 induces specific antitumor activity. J Leuk Biol 80, 2006, 1434–1444. [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, H.; Pourhanifeh, M.H.; Derakhshan, M.; Mahjoubin-Tehran, M.; Ghasemi, F.; Mousavi, S.; Rafiei, R.; Abbaszadeh-Goudarzi, K.; Mirzaei, H.R.; Mirzaei, H. CXCL-10: a new candidate for melanoma therapy? Cell Oncol (Dordr). 2020 Jun;43(3):353-365. [CrossRef]

- Kawada, K.; Sonoshita, M.; Sakashita, H.; Takabayashi, A.; Yamaoka, Y.; Manabe, T.; Inaba, K.; Minato, N.; Oshima, M.; Taketo, M.M. Pivotal role of CXCR3 in melanoma cell metastasis to lymph nodes. Cancer Res. 2004 Jun 1;64(11):4010-7. [CrossRef]

- Bakouny, Z.; Choueiri, T.K. IL-8 and cancer prognosis on immunotherapy. Nat Med. 2020, May;26(5):650-651. [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, C.; Sanmamed, M.F.; Rodríguez-Ruiz, M.E.; Teijeira, Á.; Oñate, C.; González, Á.; Ponz, M.; Schalper, K.A.; Pérez-Gracia, J.L.; Melero, I., et al. Interleukin-8 in cancer pathogenesis, treatment and follow-up. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017, 60:24–31. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Aparicio, M.; Alfaro, C. Influence of Interleukin-8 and Neutrophil Extracellular Trap (NET) formation in the tumor microenvironment: is there a pathogenic role? J Immunol Res. 2019, 2019:7. [CrossRef]

- Salerno, E.P.; Olson, W.C.; McSkimming, C.; Shea, S.; Slingluff, C.L. T cells in the human metastatic melanoma microenvironment express site-specific homing receptors and retention integrins. Int J Cancer. 2014 Feb 1;134(3):563-74. [CrossRef]

- Schalper, K.A.; Carleton, M.; Zhou, M.; Chen, T.; Feng, Y.; Huang, S.P.; Walsh, A.M.; Baxi, V.; Pandya, D.; Baradet, T.; Locke, D.; Wu, Q.; Reilly, T.P.; Phillips, P.; Nagineni, V.; Gianino, N.; Gu, J.; Zhao, H.; Perez-Gracia, J.L.; Sanmamed, M.F.; Melero, I. Elevated serum interleukin-8 is associated with enhanced intratumor neutrophils and reduced clinical benefit of immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Med. 2020, May;26(5):688-692. [CrossRef]

- Sanmamed, M.F.; Perez-Gracia, J.L.; Schalper, K.A.; Fusco, J.P.; Gonzalez, A.; Rodriguez-Ruiz, M.E.; Oñate, C.; Perez, G.; Alfaro, C.; Martín-Algarra, S.; Andueza, M.P.; Gurpide, A.; Morgado, M.; Wang, J.; Bacchiocchi, A.; Halaban, R.; Kluger, H.; Chen, L.; Sznol, M.; Melero, I. Changes in serum interleukin-8 (IL-8) levels reflect and predict response to anti-PD-1 treatment in melanoma and non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2017 Aug 1;28(8):1988-1995. [CrossRef]

- Sanmamed, M.F.; Carranza-Rua, O.; Alfaro, C.; Oñate, C.; Martín-Algarra, S.; Perez, G.; Landazuri, S.F.; Gonzalez, A.; Gross, S.; Rodriguez, I.; Muñoz-Calleja, C.; Rodríguez-Ruiz, M.; Sangro, B.; López-Picazo, J.M.; Rizzo, M.; Mazzolini, G.; Pascual, J.I.; Andueza, M.P.; Perez-Gracia, J.L.; Melero, I. Serum interleukin-8 reflects tumor burden and treatment response across malignancies of multiple tissue origins. Clin Cancer Res. 2014, Nov 15,20(22):5697-707. [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.C.; Anang, N.A.S.; Sharma, R.; Andrews, M.C.; Reuben, A.; Levine, J.H.; Cogdill, A.P.; Mancuso, J.J.; Wargo, J.A.; Pe'er, D.; Allison, J.P. Combination anti-CTLA-4 plus anti-PD-1 checkpoint blockade utilizes cellular mechanisms partially distinct from monotherapies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019 Nov 5;116(45):22699-22709. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).