1. Introduction

A nutritious diet is essential for a healthy growth and development among children. Healthy food protects against many illnesses and chronic diseases, and improves psychological well-being [

1,

2]. In addition, eating behaviors established during childhood tracks into adulthood and contribute to long-term health and disease [

2,

3,

4,

5].

There is strong evidence that a high intake of fruit and vegetables reduces the risk of cardiovascular heart disease, stroke, and hypertension [

6,

7,

8,

9], risk of cancer and respiratory diseases [

10,

11,

12]. Meanwhile, vegetable consumption may help prevent obesity and associated diseases. Despite the known health benefits of fruits and vegetables, a preponderance of children fails to meet the dietary recommendations for these food groups [

13]. The intake of vegetables by children in China and most other Western countries is far below the recommended level [

14,

15,

16].

The child’s food neophobia, or fear of new foods, is one of significant barrier to vegetable consumption [

17,

18]. Defined by [

19], "food neophobia" refers to the reluctance or outright refusal to consume novel food items. This biological defense mechanism potentially safeguards individuals from ingesting harmful or toxic substances [

20]. Food neophobia is not a phenomenon exclusive to childhood; it can persist into adulthood [

21,

22]. Studies have indicated that individuals demonstrating food neophobia tend to consume fewer vegetables, salads, poultry, and fish, thereby limiting their dietary variety [

23]. As a persistent personality trait, food neophobia is associated with detrimental dietary habits. Consequently, it contributes to the reduction of dietary diversity [

24,

25,

26] and may result in a deficiency of essential micronutrients and fiber required for normal and healthy growth and development in children [

27].

Furthermore, Sensory acceptance of vegetables by children is considered one of the main obstacles to vegetable intake [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Children's food choices are primarily driven by pleasure [

34,

35,

36]. Therefore, investigating the visual cues on children's liking and emotion responses to willingness behaviors may be a feasible method to promote their intake.

However, there is insufficient studies on visual appeal in present articles. Visual cues are one of the first factors in people's food choices, but in current strategies, the visual appeal of vegetables is often overlooked [

37]. Children are greatly influenced by the visual presentation of food, and a lack of attention to appealing colors, shapes, and overall presentation may lead to a negative perception of vegetables [

38,

39]. Moreover, emotional responses also significantly influence food choices [

40,

41]. However, current research focuses on emotional responses to diet in adults, with little exploration of the interconnections between children's emotional responses and diet [

42].

Extrinsic cues from utensils are also a direct factor influencing children's vegetable choices [

43,

44]. Utensils are the most used physical environment in daily life [

45], yet they are often overlooked. There is scarce literature exploring how utensils evoke children's emotional responses and influence food choices. Food does not exist in isolation; it is often closely linked with container and packaging [

46,

47,

48]. The utensils used to serve food are the most frequently used items in daily life, yet they are often ignored. There is almost no literature treating utensils as stimuli in research on children's food neophobia. Integrating visually cued utensils into intervention measures is crucial for enhancing the appeal of vegetables.

Finally, liking is defined as the primary individual determinant of children's vegetable intake [

49,

50,

51]. Some studies suggest a significant relationship between the shape and color of food and children's preference and liking [

52,

53,

54], but others indicate that children's food preferences correlate positively only with the type of food, particularly those with high energy density [

55,

56]. Therefore, these inconsistencies are the starting point for research into children's preferences for vegetables.

To address these issues, acknowledging the psychological aspects of food neophobia, leveraging visual appeal [

57], emotional responses [

58,

59], and promoting the willingness behaviors. This study aims to bridge this gap in understanding by examining how intrinsic and extrinsic visual cues influence the emotional responses, liking, and willingness behaviors to vegetable of children with food neophobia [

29,

60,

61].

The proposed hypotheses form the basis for testing and analyzing the impact of visual cues on vegetable willingness behaviors among children with food neophobia, providing a structured framework for the research investigation.

H1: Visual cues have a significant effect on the liking among children with food neophobia. Children exposed to attractive visual cues will report higher levels of liking compared to those presented with less appealing visual cues.

H2: Visual cues significantly influence the emotional responses of children with food neophobia. Positive visual cues will evoke more favorable emotional responses compared to neutral or negative visual cues.

H3: Visual cues significantly impact the willingness behaviors of children with food neophobia. Positive visual cues are more likely to be eaten and buy by children than those with less engaging visual cues.

H4: The impact of visual cues on liking, emotional responses, and willingness to eat and buy is controlled by age, gender, and different level food neophobia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The study design was a cross-sectional study as collected the data at a one-time point within specific period. A structured questionnaire methodology to explore the intricate relationship between visual cues, liking, emotional responses, and children's willingness behaviors. A series of well-defined assessment tools and validation procedures aimed at yielding comprehensive and credible insights into the research objectives.

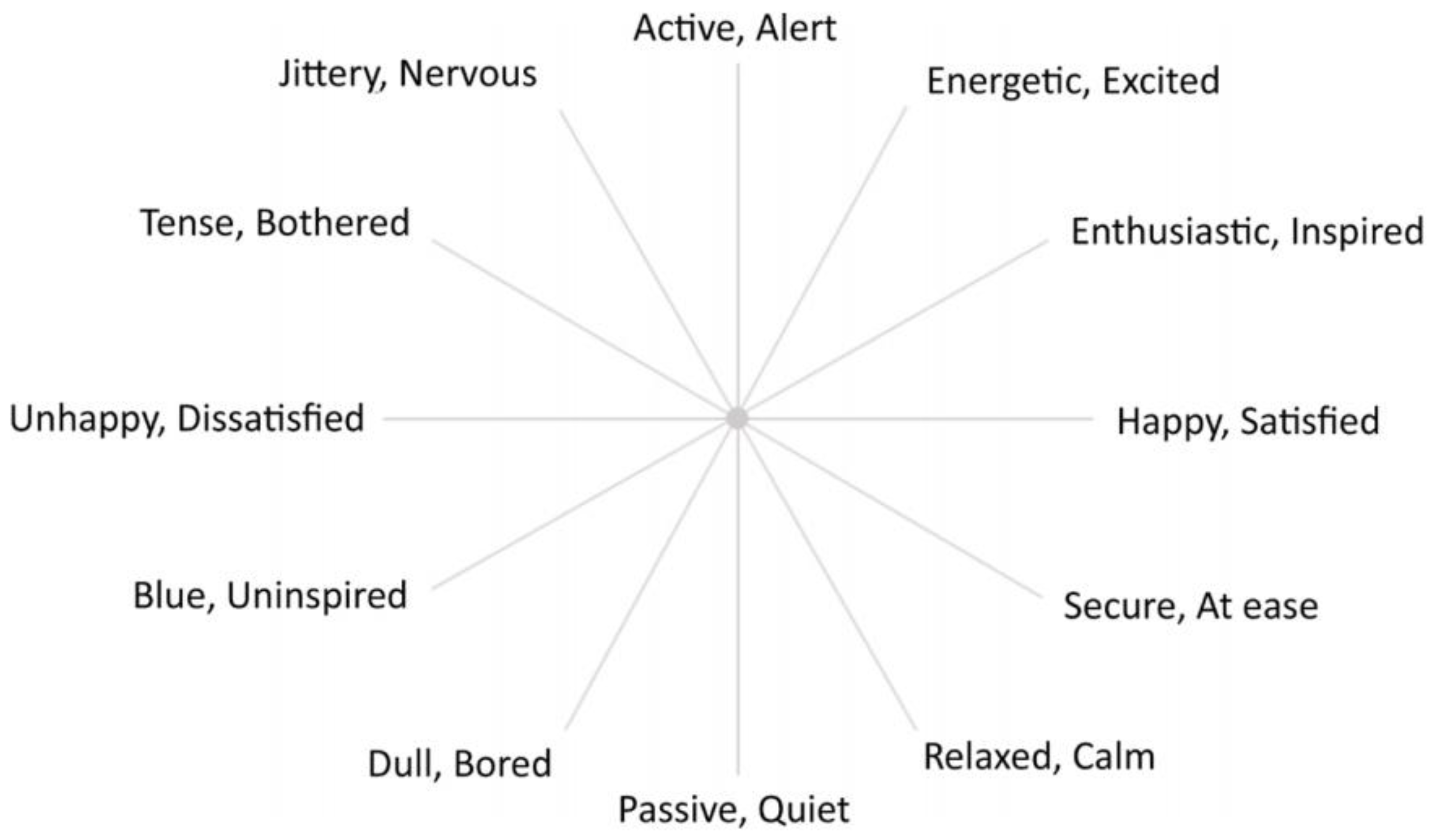

Firstly, the questionnaire structure included commences by collecting basic demographic information from the participating children to establish a comprehensive participant profile. Next, the investigation further incorporates the utilization of the Food Neophobia Scale, containing 10 items, to categorize the children according to their levels of food neophobia, distinguishing populations with high, medium, and low food neophobia. Then, used a 5-point Likert scale is then implemented to gauge liking across vegetable intrinsic cue and extrinsic cues about plates, five distinct colors of plates (white, green, red, blue, and pink), encompassing three varying shapes (triangular, round and square), to assess visual cues effectively. Moreover, to measure emotional responses. The circumplex emotional questionnaire (CEQ) (

Figure 1) has been used in several studies of emotion responding to foods, beverages and other products [

62,

63,

64,

65].

Russell and co-workers [

66] developed a “12-point circumplex model of core affect,” which constitutes a more refined version of the original circumplex model and Affect Grid. This model uses 12 dimensions, which are positioned in a circumplex structure around the circumference of a circle, enabling an individual to indicate their experienced emotions by identifying a point within the circle that represents the “core affect” of the experience in terms of both valence and arousal.

While the circumplex model and associated method for quantifying core affect were primarily used in psychological research, Jaeger and coworkers [

67,

68,

69,

70] applied the circumplex approach to the evaluation of emotions evoked by foods and beverages. By combining the single-item scale characteristic of the Affect Grid with the 12-point circumplex structure of core affect, a rapid method for food-related emotion measurement was created. This emotion circumplex ballot is shown in

Figure 1. As can be seen, specific word pairs are arranged around the perimeter of the circle, so that those on the right represent positive feelings / emotions and those on the left represent negative feelings / emotions. The upper and lower parts of the figure represent feelings / emotions that are higher and lower in emotional activation, respectively.

The Check-All-That-Apply (CATA) method is a research technique used to explore respondents' perceptions and emotional responses by presenting them with a list of options and asking them to select all that apply to their experience. By incorporating a variety of emojis and emotional words, researchers can capture emotional responses, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of their feelings and experiences.

2.2. Pilot Study

To test the questionnaire and the protocols, a pilot study was conducted. The participants consisted of 48 children from the fourth grade to sixth grade in China (24boys, 24 girls), with a mean age of 10.8 ± 0.1. After analyzing the protocol and the efficiency of the practicalities, minor adjustments were made to the protocols. Equally, minor changes were made to the questionnaire after evaluating the pilot study results (not reported).

2.3. Main Study

2.3.1. Participants

The study participants were based on a cross-sectional study including 420 children aged 9–12 years, from a public primary school in Hubei (China) were enrolled in the study. Teachers and parents were thoroughly informed about the study and parents gave written consent. Parental approval was obtained and only children who returned signed informed consent (signed by the parents or legal guardian) were considered as eligible participants in the experiment. Children's participation in the study was voluntary and classes received mixed toys (value: 80 US dollars) as a small reward for their participation.

The data were collected anonymously and involved no sensitive data. The stimuli used in this research was only the pictures sole selection criterion, so it is not needed to mention children with allergies. The questionnaire was assessed on paper, and, in total, 420 children fully completed the questionnaire. To make the participants feel more at ease during the data collection, a teacher was present, and data were collected in their classroom. Children participated in the experiment one class at a time (50 children). The mean age of the children was 10.8years (SD = 0.8 years).

2.4. Stimuli

The stimuli for this study were categorized into two main groups: internal cues (vegetables) and external cues (plates). The internal cues included the five most common vegetables: spinach, tomatoes, cucumbers, broccoli, and carrots. These vegetables were sliced and presented in servings of 220 grams each. The external cues comprised the plates used to hold the vegetables, which varied in color (white, green, red, blue, and pink) and shape (triangle, round, and square). Photographs of the stimuli were taken under natural lighting conditions to ensure the authenticity and accurate visual representation of the vegetables on the plates.

2.5. Measurement of Outcomes

All statistical analyses were conducted using the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS 27), p < 0.05 was considered to represent statistical significance.

First, the overall reliability of the questionnaire and the reliability of the food neophobia scale are tested. The overall Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the questionnaire is 0.879, and for the food neophobia scale, it is 0.968. Both values are indicating high reliability. These results reflect the stability and consistency of the measurement instruments used in the study. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and structural equation model (SEM) methods were used. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) value for the model is 0.975, which indicates that the fit of the model is relatively ideal, suggesting that the survey data fits the theoretical model very well and demonstrates good validity.

Following the reliability and validity assessments, a difference analysis was conducted to investigate how various factors influenced emotional responses and related behaviors. An independent sample T-test was employed to examine the differences in liking and emotional response dimensions. This analysis aids in understanding whether boys and girls exhibit significantly different emotional responses to the stimuli. Additionally, a variance analysis (ANOVA) was used to examine differences in liking and emotional response dimensions across participants with high, medium, and low levels of food neophobia.

ANOVA was also utilized to analyze differences in other dimensions, such as visual cues, liking, and willingness behaviors. This included examining how participants responded emotionally to various visual stimuli (e.g., the color and shape of plates), variations in liking different types of vegetables, and differences in willingness to eat the vegetables presented. Furthermore, the analysis assessed discrepancies in participants' willingness to buy. These analyses are critical for tailoring interventions and strategies aimed at promoting healthier eating habits among children, particularly through addressing emotional responses and leveraging visual appeal.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics among Participants

The mean ± SD for age was 10.85 ± 0.82, boys(211,50.2%) , girls( 209 ,49.8%). Grade median was 5, and grade 4 was16.2%, grade 5 was 51.4%, and grade 6 was 32.4%. Whether they are used to eating vegetables, yes (113, 26.9%), no (307, 73.1%), Further details the findings of the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants (

Table 1).

The above

Table 1, shows that the number of boys and girls is evenly distributed, and there will be no error caused by gender imbalance in the study. In addition, most of the participants, 73.1%, are not used to eating vegetables, which explains the necessity of the subsequent research.

3.2. Food Neophobia Characteristics of the Participants

The 10 items of the Food Neophobia Scale were scored on a 5-point Likert scale, resulting in a possible score range of 10 to 50. Participants were categorized based on their scores into three groups representing different levels of food neophobia: low level (205, 49%), medium level (93, 22%), and high level (122, 29%), See

Table 2 below for more details.

3.3. Visual Cues Scales

3.3.1. Intrinsic Cues

The results show that the

Table 3 provides different attributes of vegetables, categorized according to the level of agreement or disagreement. The dimensions included healthy, fun, and tasty. For example, in the healthy category, a significant number of participants (35.5%) said they "strongly agreed" with the statement, while in the fun category, most participants (46.9%) tended to "strongly agree." Based on the different levels of agreement expressed, this data provides insight into the participants' views and attitudes toward these vegetable attributes.

3.3.2. Extrinsic Cues

At the healthy dimension, each plate type is associated with the corresponding number of participants and their percentage distribution across the likability categories. For instance, in the white plate category, most participants (31.7%) expressed a preference by selecting 'Like,' while more participants chose the green plate (39.3%) and the triangular plate (27.9%). This data reflects the varying levels of liking towards different plate colors and shapes among the participants surveyed, see

Table 4.

At the tasty dimension provided to illustrate participants' attitudes towards the perceived tastiness of various plate colors and shapes. For example, in the white Plate category, a significant portion of participants (30.2%) expressed a strong affinity by selecting 'Strongly like,' while for the pink Plate, many participants (45%) indicated a liking with 'Like.' This data reflects the diverse preferences and perceptions of participants regarding the tastiness associated with different plate colors and shapes. It can be concluded that visual cues have a positive impact on emotional responses.

3.4. Independent Samples t-Test for Gender

3.4.1. Visual Cues Induce Mean Score of Liking of the Participants with Gender

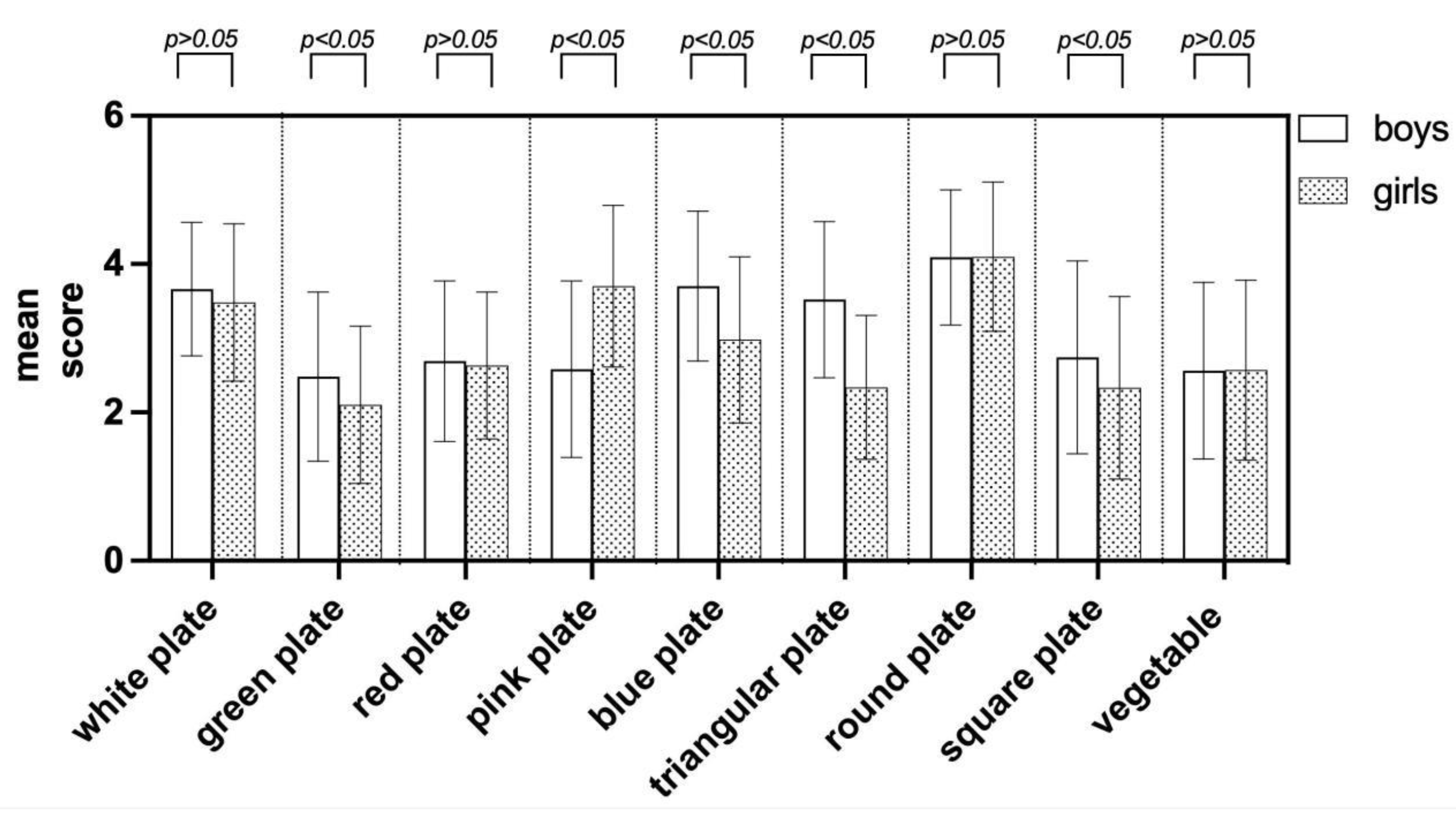

The application of an independent samples t-test revealed that children's gender has an impact on their preferences for distinct visual cues, including plate colors and shapes, as indicated in

Figure 3. Significant variations in preferences emerged when children were exposed to pictures of green, pink, and blue plates, alongside triangular and square plates. These differences were statistically notable, with p<0.05. In addition, it can be seen from the

Figure 3 that boys and girls have a higher number of choices for white and round plates, which means that further research on food neophobia is meaningful, because white and round plates are the most familiar plates, which is consistent with the fact that food neophobia usually choose familiar products [

71,

72,

73].

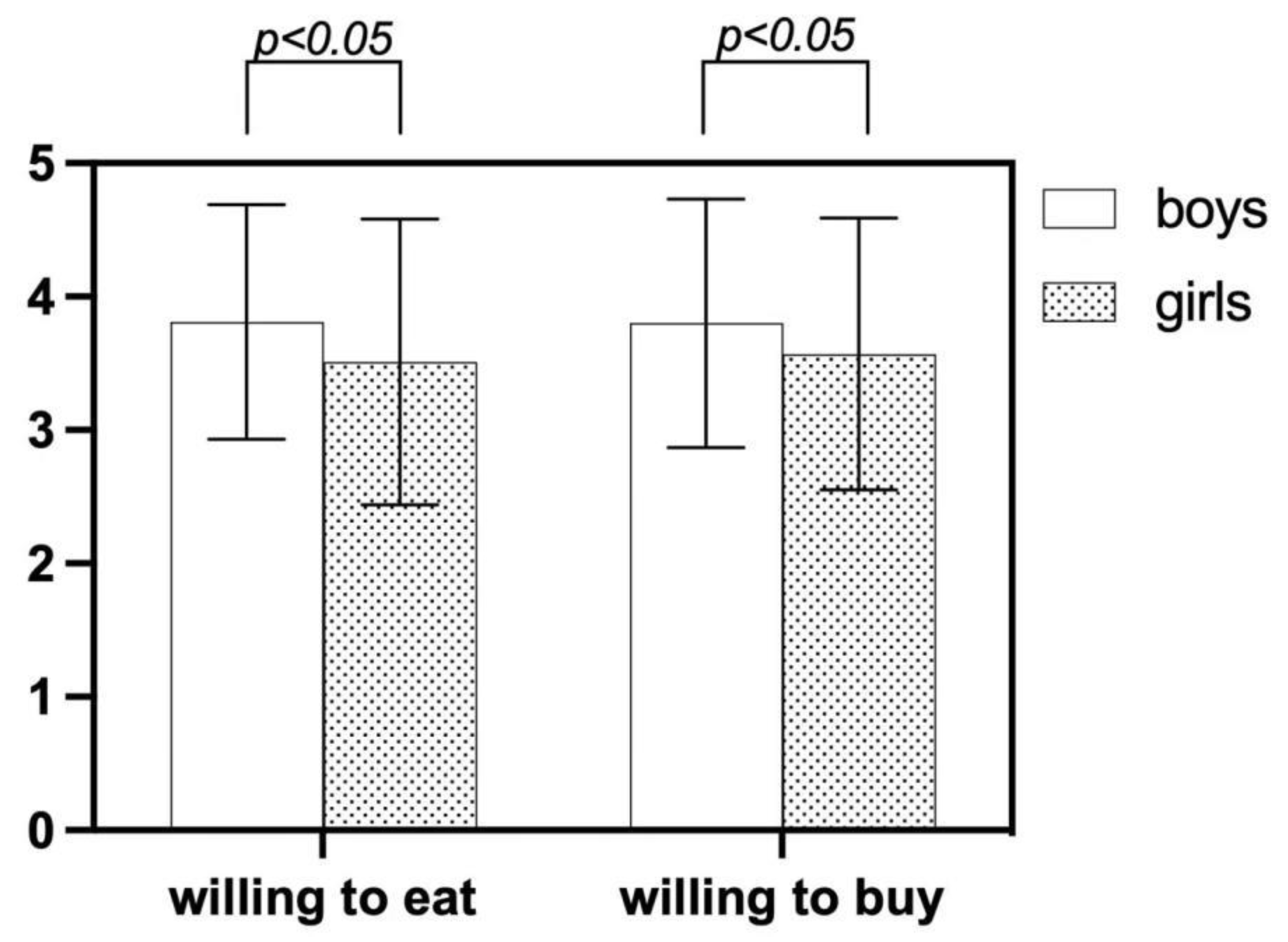

3.4.2. Willingness behaviors of the participants with Gender

There are significant gender differences in children's willingness to eat and buy, and boys are more willing than girls. These variations were statistically significant, p<0.05.

3.5. ANOVA Analysis for Food Neophobia

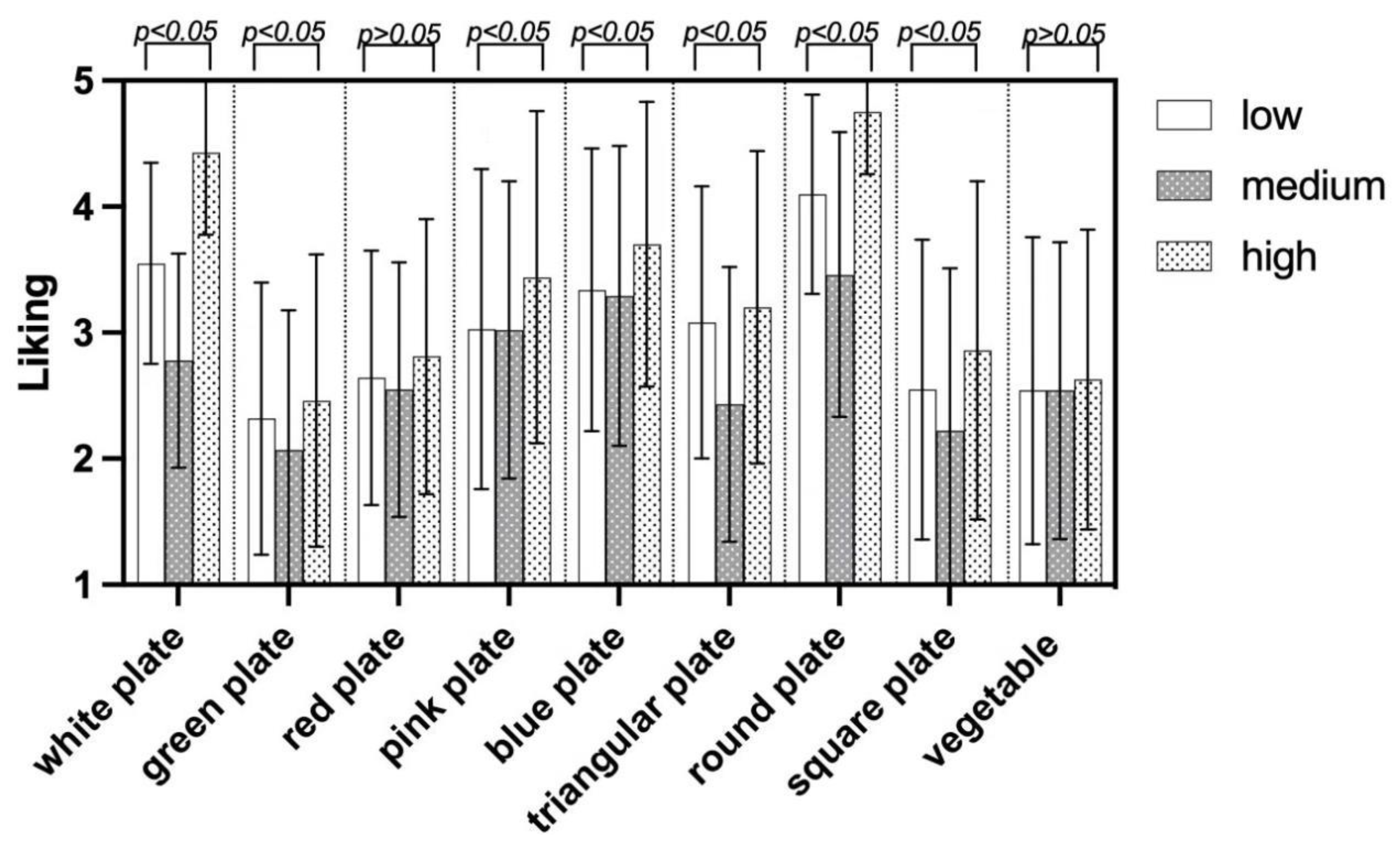

3.5.1. Visual Cues Induce Liking of the Participants with Food Neophobia

The application of a One-way ANOVA test indicates that children's food neophobia levels play a role in influencing their preferences for various visual cues, as shown in

Figure 4. The results revealed significant disparities in liking patterns when children with different level of food neophobia were exposed to images of white, green, pink, and blue plates, as well as triangular, round, and square plates. These variations were statistically significant, p<0.05.

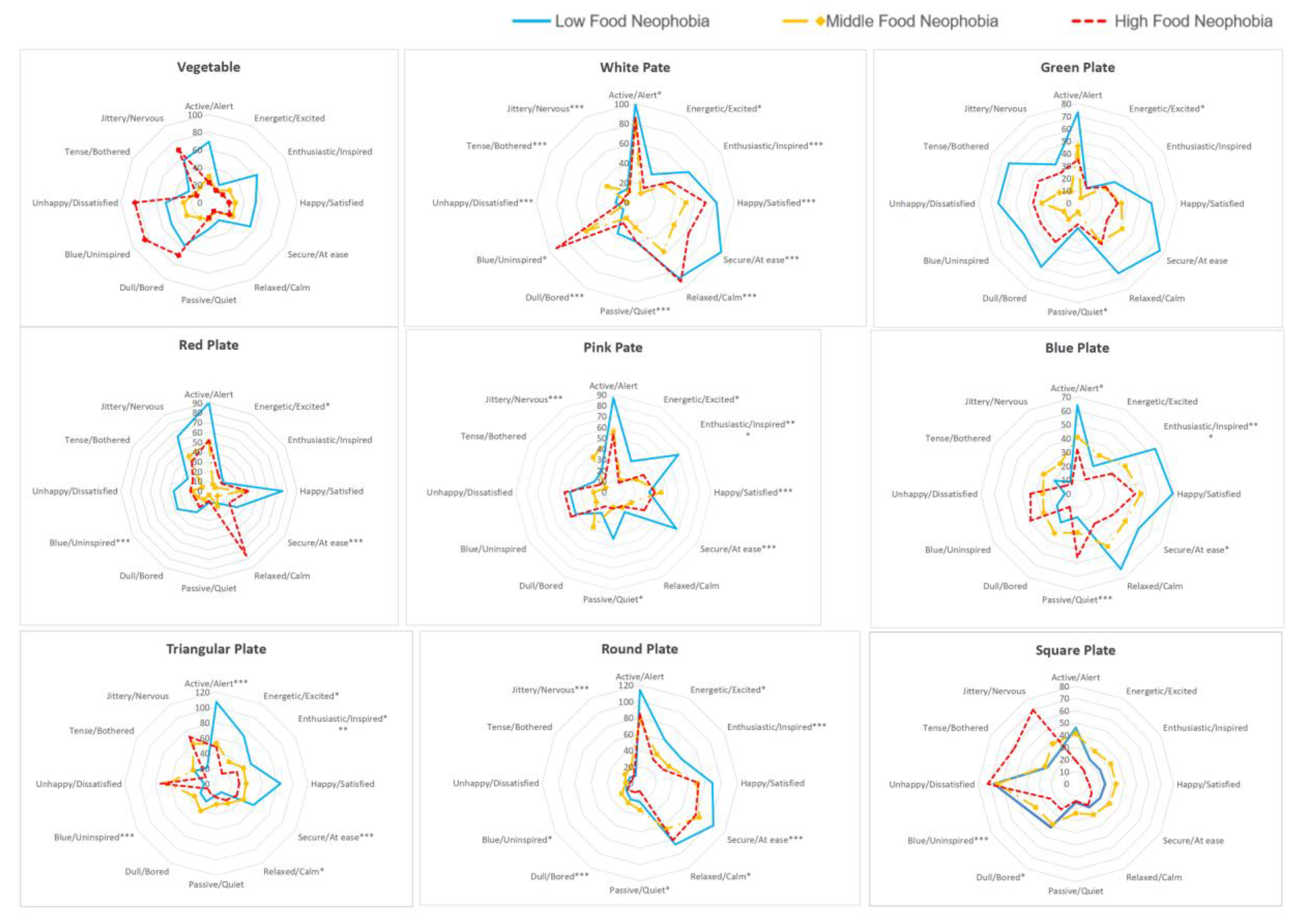

3.5.2. Analysis of Food Neophobia in Emotional Responses

Despite the intrinsic cues of vegetables not having a significant effect, high and low arousal, and high valence still elicited emotional responses in children with food neophobia, such as active/alert, blue/uninspired, and happy/satisfied. There was a notable correlation between emotional responses to food neophobia on white plates, particularly with high-arousal emotions like active/alert, low-arousal emotions like passive/quiet, and high-valence emotions like enthusiastic/inspired in high level of food neophobia. Conversely, no positive emotion responses were triggered by the green plate. Instead, negative and low-arousal emotions, such as dull/bored and blue/uninspired, were predominant. On the red plate, there was a significant difference between children with high and medium levels of food neophobia. Those with high food neophobia exhibited higher scores in active/alert emotions, whereas medium level food neophobia had higher scores in blue/bored. The pink plate also showed significant differences in emotional responses, particularly in high-arousal emotions like active/alert and energetic/excited, as well as high-valence emotions like happy/satisfied and enthusiastic/inspired, and low-arousal emotions like passive/quiet. The blue plate elicited significant differences in tense/bothered, active/alert, and secure/at ease responses.

Emotional responses to the triangular plate varied significantly, with notable differences in active/alert, energetic/excited, enthusiastic/inspired, blue/uninspired, and secure/at ease emotions. The round plate produced more considerable differences in emotional responses such as energetic/excited, enthusiastic/inspired, dull/bored, blue/uninspired, secure/at ease, and unhappy/dissatisfied among children with food neophobia (

Figure 5). Finally, the square plate revealed significant emotional responses only for the emotion word pairs blue/uninspired and dull/bored.

Therefore, the study demonstrated that the color and shape of plates can significantly influence the emotional responses of children with food neophobia. These responses vary depending on the specific visual cues presented, highlighting the importance of considering these factors when addressing food neophobia in children.

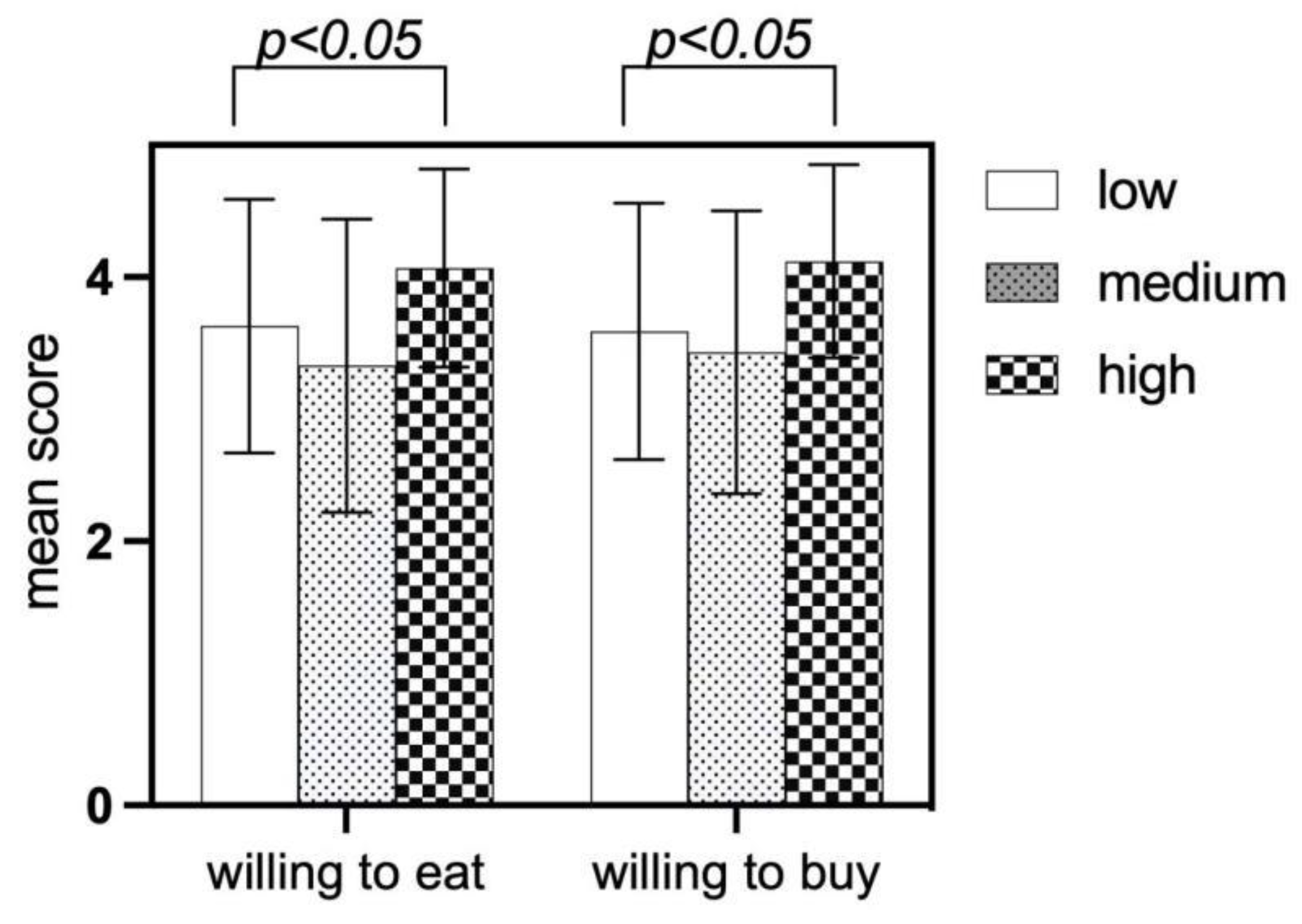

3.5.3. Analysis of Food Neophobia Differences in Willingness Behaviors

There are significant differences in the willingness to eat and buy among children with food neophobia, and the differences are statistically significant (p<0.05). Children with high levels of food neophobia have the strongest willingness to eat, which deserves further analysis and research.

3.6. Spearman Correlation Analysis

This study is based on the control variables of age, gender, and food neophobia, and the mediating variables are liking and, emotional responses, independent variables are intrinsic cues, extrinsic cues, and dependent variables are willingness to eat and buy. Since the emotion word pairs in this study are categorical variables and there is a possibility of non-normal distribution, it would be more accurate to use Spearman correlation analysis when conducting correlation analysis. To analyze the relationship between variables, as shown in

Table 6.

3.6.1. Food Neophobia (FN)

Age shows significant positive correlations with emotional responses (0.157), Intrinsic Cues (0.144), Willing to eat (0.096), and Willing to buy (0.106). This suggests that age may positively influence emotional responses to food, perceptions of intrinsic qualities, and willingness to try and purchase food. Gender shows significant negative correlations with several variables, including Liking (-0.239), Emotional responses (-0.180), Intrinsic Cues (-0.134), Extrinsic Cues (-0.171), Willing to eat (-0.150), and Willing to buy (-0.119). This implies gender differences in these responses, potentially indicating that girls might have lower scores in these measures. Additionally, there is a strong correlation between Liking and Emotional responses (0.131), Intrinsic Cues (0.439), Extrinsic Cues (0.393), Willing to eat (0.355), and Willing to buy (0.375). This highlights that liking is a central factor influencing other perceptions and behaviors related to food. Next, emotional response has moderate positive correlations with Intrinsic Cues (0.482), Extrinsic Cues (0.467), Willing to eat (0.499), and Willing to buy (0.463), suggesting that emotional response to food significantly impacts other factors. Both intrinsic and extrinsic cues have strong correlations with Willing to eat and Willing to buy, indicating the importance of these cues in predicting food-related behaviors.

Firstly, gender has significant negative correlations with Liking (ρ = -0.217, p < 0.01), Emotional response (ρ = -0.186, p < 0.01), and Extrinsic Cues (ρ = -0.167, p < 0.01). This suggests that gender differences influence these attributes, with girls having lower scores on these variables. A significant but smaller negative correlation exists between Gender and Intrinsic Cues (ρ = -0.120, p < 0.05) and Willingness to Eat (ρ = -0.119, p < 0.05).

Secondly, Food neophobia has positive correlations with Liking (ρ = 0.172, p < 0.01), Intrinsic Cues (ρ = 0.151, p < 0.01), Extrinsic Cues (ρ = 0.102, p < 0.05), and Willingness to Buy (ρ = 0.180, p < 0.01). This indicates that higher levels of food neophobia are somewhat paradoxically associated with higher liking and willingness to buy, potentially suggesting a nuanced relationship that could be mediated by factors.

Then, Liking has a strong positive correlation with Emotional Response (ρ = 0.197, p < 0.01), Intrinsic Cues (ρ = 0.428, p < 0.01), Extrinsic Cues (ρ = 0.397, p < 0.01), Willingness to Eat (ρ = 0.359, p < 0.01), and Willingness to Buy (ρ = 0.378, p < 0.01). Liking strongly impacts how children feel about the food, suggesting that positive visual sensory experiences directly influence other positive behaviors. And Emotional Response is positively correlated with Intrinsic Cues (ρ = 0.490, p < 0.01), Extrinsic Cues (ρ = 0.464, p < 0.01), Willingness to Eat (ρ = 0.504, p < 0.01), and Willingness to Buy (ρ = 0.450, p < 0.01). Emotional responses strongly influence both intrinsic and extrinsic assessments as well as willingness behaviors, underscoring the role of emotions in food-related decisions.

Moreover, Intrinsic Cues have positive correlations with Extrinsic Cues (ρ = 0.262, p < 0.01), Willingness to Eat (ρ = 0.422, p < 0.01), and Willingness to Buy (ρ = 0.381, p < 0.01). The attractiveness or healthiness of the vegetables (intrinsic characteristics) directly relates to how they are perceived in different contexts (extrinsic factors) and the willingness to engage with the food, either by eating or buying. Meanwhile, Extrinsic Cues correlate positively with Willingness to Eat (ρ = 0.499, p < 0.01) and Willingness to Buy (ρ = 0.500, p < 0.01), showing that external factors like plate color and shape can profoundly influence children's willingness to engage with the food.

Furthermore, Willingness to Eat and Willingness to Buy are strongly positively correlated with each other (ρ = 0.360, p < 0.01). Both also show strong positive correlations with other variables significantly tied to sensory and emotional responses, emphasizing that a complex interplay of intrinsic and extrinsic factors, mediated by emotion and liking responses, drives these behaviors.

Therefore, the findings about gender impacts liking, emotional response, and extrinsic cues, indicating potential gender-specific perceptions. Paradoxically, higher food neophobia correlates with higher liking and willingness to buy; this needs further exploration under potential mediators or cultural factors. Liking and emotional response are key intermediaries linking intrinsic and extrinsic cues to willingness behaviors, indicating that positive sensory experiences are crucial. Both intrinsic and extrinsic factors play significant roles in shaping children’s decisions and behaviors regarding vegetables, with external presentation being particularly impactful in initial decision-making stages. Further inferential or multivariate analyses could uncover deeper insights, especially regarding paradoxical findings around food neophobia.

3.7. Hierarchical Regression Analysis

The hierarchical regression analyses reveal that both intrinsic and extrinsic cues play significant roles in influencing children's willingness to eat vegetables, with liking and emotional responses serving as crucial mediators. Intrinsic characteristics, such as taste and healthiness, have a strong positive effect on willingness to eat (β = 0.415, p < 0.001) and predict liking (β = 0.194, p < 0.001). Extrinsic factors, such as plate color and shape, also positively affect this behavior (β = 0.562, p < 0.001) and predict liking (β = 0.191, p < 0.001). Gender differences are marginally significant for intrinsic cues and more pronounced for extrinsic cues, indicating varying preferences between boys and girls. Food neophobia shows a small positive effect on willingness to eat with both intrinsic and extrinsic cues, but this effect is fully mediated by liking, emphasizing the importance of positive sensory experiences (Intrinsic: β = 0.325, p < 0.001; Extrinsic: β = 0.296, p < 0.001). Moreover, liking is positively influenced by food neophobia (Intrinsic: β = 0.113, p < 0.001; Extrinsic: β = 0.123, p < 0.001). Emotional responses also significantly mediate the relationship between both intrinsic (β = 0.527, p < 0.001) and extrinsic cues (β = 0.467, p < 0.001) and willingness to eat. These emotional reactions are influenced positively by intrinsic (β = 0.325, p < 0.001) and extrinsic cues (β = 0.355, p < 0.001), and by age (Intrinsic: β = 0.157, p < 0.001; Extrinsic: β = 0.182, p < 0.001), while gender (Intrinsic: β = -0.155, p < 0.001; Extrinsic: β = -0.134, p < 0.05) negatively impact emotional responses.

Moreover, intrinsic and extrinsic cues significantly affect children's willingness to buy, with both the liking scale and emotional responses serving as crucial mediators. Intrinsic characteristics like healthiness, fun, and tastiness positively impact willingness to buy (β = 0.368, p < 0.001), especially among older children (β = 0.194, p < 0.01). Extrinsic factors such as plate color and shape similarly enhance willingness to buy (β = 0.592, p < 0.001). Gender does not significantly influence willingness to buy in either context. When the liking scale is considered as a mediator, the effects of both intrinsic (β = 0.297, p < 0.001) and extrinsic cues (β = 0.538, p < 0.001) are reduced but still significant, confirming partial mediation (Intrinsic: β = 0.369, p < 0.001; Extrinsic: β = 0.280, p < 0.001). Both intrinsic and extrinsic cues significantly predict the liking scale (Intrinsic: β = 0.194, p < 0.001; Extrinsic: β = 0.191, p < 0.001), with gender showing a negative impact (Intrinsic: β = -0.168, p < 0.001; Extrinsic: β = -0.16, p < 0.001) and food neophobia paradoxically enhancing liking (Intrinsic: β = 0.113, p < 0.001; Extrinsic: β = 0.123, p < 0.001). Emotional responses also partially mediate the effects of intrinsic (β = 0.216, p < 0.001) and extrinsic cues (β = 0.466, p < 0.001), emphasizing the role of emotions (Intrinsic: β = 0.468, p < 0.001; Extrinsic: β = 0.355, p < 0.001). Older children have more positive emotional reactions (Intrinsic: β = 0.157, p < 0.001; Extrinsic: β = 0.182, p < 0.001), whereas gender negatively affects these responses (Intrinsic: β = -0.155, p < 0.001; Extrinsic: β = -0.134, p < 0.05). In conclusion, enhancing both intrinsic and extrinsic attributes of vegetables and fostering positive sensory and emotional experiences are essential strategies to increase children's willingness to eat and buy, while addressing demographic differences such as age, gender, and decreasing food neophobia.

4. Discussion

The study utilized the food neophobia scale to evaluate the prevalence of high food neophobia among children, with findings consistent with literature indicating a range from 10.8% to 30.1% [

74,

75,

76,

77]. A high response rate of 88.1% from 420 participants indicated strong motivation to engage children in the study, focusing on color and shape attributes impacting food choices significantly. Visual cues like plate color and shape influenced preferences, highlighting the importance of these factors in shaping individual choices [

78].

The research emphasized the role of food-evoked emotions in predicting individual food choices, revealing a strong correlation between food-related emotions and perceived liking. The study recognized that both liking and emotions influence children's actions such as willingness to eat and buy, providing deeper insights than simple choice assessments [

39]. Prior research indicated moderate to high correlations between emotion scores and liking, suggesting a robust link between valence and preference for certain emotion words, aligning with previous findings on emotional responses to food products [

79,

80,

81].

Gender differences in color preferences were highlighted, with significant distinctions between boys and girls, notably in their liking for specific colors and shapes [

82]. The study revealed differences in liking and emotional responses among children with food neophobia, categorizing them into high, medium, and low levels. Notably, preferences for plates of different colors and shapes varied significantly among these groups, with white plates being perceived as more familiar, suggesting a preference for familiar elements among children with high food neophobia [

83]. Post hoc analyses indicated significant preferences for specific colors and shapes impacting liking levels and perception of food taste.

Moreover, the research explored the relationship between food neophobia and intrinsic and extrinsic clues in food choices. The results showed moderate positive correlations between food neophobia and reliance on both intrinsic and extrinsic cues, highlighting their impact on decision-making processes. Furthermore, the correlation between food neophobia and liking emphasized a moderate positive relationship, suggesting that individual preferences for colors and shapes can evolve into pleasurable experiences once tried. The study proposed using familiar colors and shapes to enhance comfort and willingness to engage with food choices effectively.

In conclusion, the study underscored the strategic use of visual cues to enhance children's experiences concerning liking, emotional responses, and decision-making related to eating and buying behaviors. Different color shades significantly influenced liking scores and emotional responses, with white, pink, and blue colors evoking more positive emotions than green and red colors. The study highlighted the importance of intrinsic and extrinsic cues as predictors of willingness to eat and buy vegetables, emphasizing the mediating roles of liking and emotion responses in promoting vegetable consumption.

5. Limitations

This study may have limitations concerning the demographic characteristics of the sample population. It was conducted on a specific group child from grade 4 to grade 6, the generalizability of the findings to a broader population may be restricted. Reliance on self-reported data introduces the potential for response biases that could influence the accuracy and reliability of the results. Other than that, the participants were recruited from the public primary school of Hubei province. Thus, they cannot be representative of the whole country. This study was a cross-sectional study, which can only represent the participants at a particular time but cannot change in long-term effects can be observed.

6. Conclusion

The current study demonstrated that visual cues (intrinsic and extrinsic cues) could be used as a strategic tool to specially modify children with food neophobia experiences regarding their liking, emotional responses and willingness to eat and to buy behaviors. The different plate colors and shapes significantly impacted the liking scores. Familiar colors (white) and shapes (round) elicited higher valance and high arousal emotion responses. Meanwhile, the green and red plates, as well as the square plates, elicited more negative emotions. Children neither used liking nor emotion alone to make their willingness decision; hence, changing liking scores and emotion intensity corresponding to visual cues could potentially impact.

In conclusion, the study highlights the significant roles played by intrinsic cues, extrinsic cues, emotional responses, and various control variables. Intrinsic cues consistently demonstrated a strong positive influence on both willingness to buy and emotional responses, underlining the importance of product attributes in shaping children willingness. The mediation analyses emphasized the crucial link between emotional responses and willingness intentions, illuminating the impact of children emotions on willing to eat and buy behaviors. Additionally, the study underscored the significance of external factors, like extrinsic cues, in influencing children willingness behaviors and emotional responses, reaffirming the critical role of environmental stimuli in children decision-making processes.

7. Implications

Both liking, and emotional responses significantly mediate the relationships between intrinsic/extrinsic cues and willingness to eat or buy, emphasizing the necessity of fostering positive sensory and emotional experiences. More details, about gender, age, and food neophobia differences play critical roles in moderating these relationships. Boys and girls have distinct preferences and emotional reactions, older children generally respond more positively to enhanced cues. Although initially presenting as a barrier, food neophobia's negative impact can be mitigated by improving the visual sensory appeal and emotional engagement with vegetables and plates.

These findings highlight the importance of tailored approaches that consider differences among age, gender, and children with food neophobia and the necessity of enhancing both the intrinsic and extrinsic attributes of vegetables and plates to promote healthier eating habits among children.

The visual cues in this study have a positive impact on children's liking and emotional responses. When targeting children with food neophobia, the results of this study can be used as a reference theory, especially the extrinsic cues in the visual cues, that is, the color and shape of the plate, which give children a sense of health and deliciousness, proving that the selected stimuli have a promoting effect on children's liking and positive emotional responses. Based on emotion factors, focusing on vegetables, and establishing positive emotion connections with the plates containing vegetables, and providing visual sensory stimulation-oriented experience strategies may help reduce rejection and disgust of vegetables and improve the acceptance of children with food neophobia.

In addition, it has positive theoretical guidance significance for parents, educators, health care professionals, tableware designers, etc., aiming to encourage children with new food phobia to develop healthier eating habits through positive visual stimulation. Establish a healthier and more positive relationship with vegetables from an early age and reduce the number of food neophobia in adulthood.

The study showed that internal cues and external cues have a complex interactive relationship in influencing children's liking and emotional responses and their willingness to eat and buy. This also directly leads to the willingness behavior of children to make choices in the end.

Finally, moving forward, it is crucial to tailor interventions aimed at guiding children with food neophobia by incorporating emotional engagement strategies. Recommendations include creating positive emotion associations with food products tailored to children, offering sensory-oriented experiences to make food exploration enjoyable, and incorporating familiar elements to reduce aversions. Collaborative efforts involving parents, educators, and healthcare professionals are essential in promoting healthier eating habits among children with food neophobia. Encouraging exposure to a variety of foods in a supportive environment, providing education on balanced diets, and creating engaging sensory experiences can effectively address food neophobia, fostering a positive relationship with food from an early age.

Funding

This study did not receive any funding.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Questions and response categories in the questionnaire.

Table A1.

Questions and response categories in the questionnaire.

| Questions |

Type of answers |

|

Section 1 Demographic characteristics |

|

| Q1-Q3 Sociodemographic: age, gender, grade |

Multiple choice questions |

| Q4 Used to eating vegetables |

Multiple choice questions |

|

Section 2 Food Neophobia Scale: 5-point scale |

|

| Q5-Q14 Food Neophobia |

5-point scale |

|

Section 3 Liking and Emotion Responses to Visual Cues |

|

| Q15-Q21 Some questions about vegetables. |

|

| Q15 How much do you like eating the vegetables in this picture? |

5-point scale |

| Q16-18 Do you think this vegetable is healthy [tasty, fun to eat]? |

5-point scale |

| Q19 How would the vegetables in this picture make you feel? |

CATA |

| Q20-Q21. How willing are you to eat the vegetables [ ask parents to buy the vegetables] in the picture? |

5-point scale |

| Q22-27: Some questions about white plate |

5-point scale |

| Q28-33: Some questions about green plate |

5-point scale |

| Q34-39: Some questions about red plate |

5-point scale |

| Q40-45: Some questions about pink plate |

5-point scale |

| Q46-51: Some questions about blue plate |

5-point scale |

| Q52-57: Some questions about triangular plate |

5-point scale |

| Q58-63: Some questions about round plate |

5-point scale |

| Q64-69: Some questions about square plate. |

5-point scale |

References

- Bazzano, L.A.; Serdula, M.K.; Liu, S. Dietary intake of fruits and vegetables and risk of cardiovascular disease. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2003, 5, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaikkonen, J.E.; Mikkilä, V.; Magnussen, C.G.; Juonala, M.; Viikari, J.S.A.; Raitakari, O.T. Does childhood nutrition influence adult cardiovascular disease risk?—Insights from the Young Finns Study. Ann. Med. 2013, 45, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Story, M.T.; Neumark-Stzainer, D.R.; Sherwood, N.E.; Holt, K.; Sofka, D.; Trowbridge, F.L.; Barlow, S.E. Management of Child and Adolescent Obesity: Attitudes, Barriers, Skills, and Training Needs Among Health Care Professionals. Pediatrics 2002, 110, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, G.C.; Coffey, C.; Carlin, J.B.; Sawyer, S.M.; Williams, J.; Olsson, C.A.; Wake, M. Overweight and Obesity Between Adolescence and Young Adulthood: A 10-year Prospective Cohort Study. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2011, 48, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, K.S.; Katan, M.B. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. Public Health Nutr 2004, 7, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, F.J.; Nowson, C.A.; MacGregor, G.A. Fruit and vegetable consumption and stroke: Meta-analysis of cohort studies. Lancet 2006, 367, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauchet, L.; Amouyel, P.; Hercberg, S.; Dallongeville, J. Fruit and Vegetable Consumption and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease: A Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 2588–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeing, H.; Bechthold, A.; Bub, A.; Ellinger, S.; Haller, D.; Kroke, A.; Leschik-Bonnet, E.; Müller, M.J.; Oberritter, H.; Schulze, M.; et al. Critical review: vegetables and fruit in the prevention of chronic diseases. Eur. J. Nutr. 2012, 51, 637–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Gong, G.; Li, G.; Li, C. Consumption of fruit, but not vegetables, may reduce risk of gastric cancer: Results from a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur. J. Cancer 2014, 50, 1498–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antova, T.; Pattenden, S.; Nikiforov, B.; Leonardi, G.; Boeva, B.; Fletcher, T. . & Holikova, J. Nutrition and respiratory health in children in six Central and Eastern European countries. Thorax 2003, 58, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forastiere, F.; Pistelli, R.; Sestini, P.; Fortes, C.; Renzoni, E.; Rusconi, F.; Dell'Orco, V.; Ciccone, G.; Bisanti, L. Consumption of fresh fruit rich in vitamin C and wheezing symptoms in children. Thorax 2000, 55, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, H.-C.; Joshipura, K.J.; Jiang, R.; Hu, F.B.; Hunter, D.; Smith-Warner, S.A.; Colditz, G.A.; Rosner, B.; Spiegelman, D.; Willett, W.C. Fruit and Vegetable Intake and Risk of Major Chronic Disease. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2004, 96, 1577–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krebs-Smith, S.M.; Guenther, P.M.; Subar, A.F.; Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Dodd, K.W. Americans Do Not Meet Federal Dietary Recommendations. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 1832–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.; Tsou, S.C. Combating micronutrient deficiencies through vegetables—a neglected food frontier in Asia. Food Policy 1997, 22, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bentley, M.E.; Zhai, F.; Popkin, B.M. Tracking of Dietary Intake Patterns of Chinese from Childhood to Adolescence over a Six-Year Follow-Up Period. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason-D'Croz, D.; Bogard, J.R.; Sulser, T.B.; Cenacchi, N.; Dunston, S.; Herrero, M.; Wiebe, K. Gaps between fruit and vegetable production, demand, and recommended consumption at global and national levels: an integrated modelling study. Lancet Planet. Heal. 2019, 3, e318–e329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, L.J.; Wardle, J.; Gibson, E.L.; Sapochnik, M.; Sheiham, A.; Lawson, M. Demographic, familial and trait predictors of fruit and vegetable consumption by pre-school children. Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardle, J.; Carnell, S.; Cooke, L. Parental control over feeding and children’s fruit and vegetable intake: How are they related? J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2005, 105, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pliner, P.; Hobden, K. Development of a scale to measure the trait of food neophobia in humans. Appetite 1992, 19, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifci, I.; Demirkol, S.; Altunel, G.K.; Cifci, H. Overcoming the food neophobia towards science-based cooked food: The supplier perspective. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2020, 22, 100280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaar, J.L.; Shapiro, A.L.; Fell, D.M.; Johnson, S.L. Parental feeding practices, food neophobia, and child food preferences: What combination of factors results in children eating a variety of foods? Food Qual. Preference 2016, 50, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicklaus, S.; Monnery-Patris, S. Food neophobia in children and its relationships with parental feeding practices/style. In Food Neophobia; Woodhead Publishing, 2018; pp. 255–286.

- Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, C.; Keller, C. Antecedents of food neophobia and its association with eating behavior and food choices. Food Qual. Preference 2013, 30, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, L.L. Preschool children's food preferences and consumption patterns. J. Nutr. Educ. 1979, 11, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, L.L.; O Fisher, J. Development of eating behaviors among children and adolescents. Pediatrics 1998, 101, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Falciglia, G.; Couch, S.C.; Gribble, L.S.; Pabst, S.M.; Frank, R. Food Neophobia in Childhood Affects Dietary Variety. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2000, 100, 1474–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carruth, B.; Skinner, J.; Houck, K.; Moran, J.; Coletta, F.; Ott, D. The Phenomenon of “Picky Eater”: A Behavioral Marker in Eating Patterns of Toddlers. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 1998, 17, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blissett, J.; Fogel, A. Intrinsic and extrinsic influences on children's acceptance of new foods. Physiol. Behav. 2013, 121, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poelman, A.A.; Delahunty, C.M.; de Graaf, C. Vegetable preparation practices for 5–6 years old Australian children as reported by their parents; relationships with liking and consumption. Food Qual. Preference 2015, 42, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, K.; Dinnella, C.; Spinelli, S.; Morizet, D.; Saulais, L.; Hemingway, A.; Monteleone, E.; Depezay, L.; Perez-Cueto, F.; Hartwell, H. Liking and consumption of vegetables with more appealing and less appealing sensory properties: Associations with attitudes, food neophobia and food choice motivations in European adolescents. Food Qual. Preference 2019, 75, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinaerts, E.; de Nooijer, J.; Candel, M.; de Vries, N. Explaining school children's fruit and vegetable consumption: The contributions of availability, accessibility, exposure, parental consumption and habit in addition to psychosocial factors. Appetite 2007, 48, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchette, L.; Brug, J. Determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among 6–12-year-old children and effective interventions to increase consumption. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2005, 18, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, K.W.; Baranowski, T.; Owens, E.; Marsh, T.; Rittenberry, L.; de Moor, C. Availability, Accessibility, and Preferences for Fruit, 100% Fruit Juice, and Vegetables Influence Children's Dietary Behavior. Heal. Educ. Behav. 2003, 30, 615–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brug, J.; Tak, N.I.; Velde, S.J.T.; Bere, E.; de Bourdeaudhuij, I. Taste preferences, liking and other factors related to fruit and vegetable intakes among schoolchildren: results from observational studies. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 99, S7–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köster, E.P.; Mojet, J. From mood to food and from food to mood: A psychological perspective on the measurement of food-related emotions in consumer research. Food Res. Int. 2015, 76, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, L.L. Development of food preferences. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1999, 19, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Laan, L.N.; De Ridder, D.T.D.; Viergever, M.A.; Smeets, P.A.M. Appearance Matters: Neural Correlates of Food Choice and Packaging Aesthetics. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e41738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schifferstein, H.N.; Wehrle, T.; Carbon, C.-C. Consumer expectations for vegetables with typical and atypical colors: The case of carrots. Food Qual. Preference 2019, 72, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C. On the psychological impact of food colour. Flavour 2015, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalenberg, J.R.; Gutjar, S.; ter Horst, G.J.; de Graaf, K.; Renken, R.J.; Jager, G. Evoked Emotions Predict Food Choice. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e115388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; King, J.; Prinyawiwatkul, W. A review of measurement and relationships between food, eating behavior and emotion. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 36, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Roose, G. Visual Design Cues Impacting Food Choice: A Review and Future Research Agenda. Foods 2020, 9, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaglioni, S.; De Cosmi, V.; Ciappolino, V.; Parazzini, F.; Brambilla, P.; Agostoni, C. Factors Influencing Children’s Eating Behaviours. Nutrients 2018, 10, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krølner, R.; Rasmussen, M.; Brug, J.; Klepp, K.-I.; Wind, M.; Due, P. Determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among children and adolescents: a review of the literature. Part II: qualitative studies. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 112–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolnicka, K.; Taraszewska, A.M.; Jaczewska-Schuetz, J.; Jarosz, M. Factors within the family environment such as parents’ dietary habits and fruit and vegetable availability have the greatest influence on fruit and vegetable consumption by Polish children. Public Health Nutr 2015, 18, 2705–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrose, G.; Harris, P. (2017). Packaging the brand: The relationship between packaging design and brand identity. Bloomsbury Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Marsh, K.; Bugusu, B. Food packaging—roles, materials, and environmental issues. Journal of food science 2007, 72, R39–R55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosīte, D.; König, L.M.; De-Loyde, K.; Lee, I.; Pechey, E.; Clarke, N.; Maynard, O.; Morris, R.W.; Munafò, M.R.; Marteau, T.M.; et al. Plate size and food consumption: a pre-registered experimental study in a general population sample. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drewnowski, A. Taste preferences and food intake. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1997, 17, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, E.L.; Wardle, J.; Watts, C.J. Fruit and Vegetable Consumption, Nutritional Knowledge and Beliefs in Mothers and Children. Appetite 1998, 31, 205–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, S.D.; Thompson, W.O. Fourth-Grade Children's Consumption of Fruit and Vegetable Items Available as Part of School Lunches Is Closely Related to Preferences. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2002, 34, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kildegaard, H.; Olsen, A.; Gabrielsen, G.; Møller, P.; Thybo, A. A method to measure the effect of food appearance factors on children’s visual preferences. Food Qual. Preference 2011, 22, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, D.; Stuart, M.; Bell, R. Examining the relationship between product package colour and product selection in preschoolers. Food Qual. Preference 2006, 17, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunk, L.; Møller, P. Do children prefer colored plates? Food Qual. Preference 2019, 73, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, L.L.; O Fisher, J. Development of eating behaviors among children and adolescents. Pediatrics 1998, 101, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briefel, R.R.; Wilson, A.; Gleason, P.M. Consumption of Low-Nutrient, Energy-Dense Foods and Beverages at School, Home, and Other Locations among School Lunch Participants and Nonparticipants. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, S79–S90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, E.; Mulkens, S.; Jansen, A. How to promote fruit consumption in children. Visual appeal versus restriction. Appetite 2010, 54, 599–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbilek, O.; Sener, B. Product design, semantics and emotional response. Ergonomics 2003, 46, 1346–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Strien, T.; Cebolla, A.; Etchemendy, E.; Gutiérrez-Maldonado, J.; Ferrer-García, M.; Botella, C.; Baños, R. Emotional eating and food intake after sadness and joy. Appetite 2013, 66, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laureati, M.; Bergamaschi, V.; Pagliarini, E. School-based intervention with children. Peer-modeling, reward and repeated exposure reduce food neophobia and increase liking of fruits and vegetables. Appetite 2014, 83, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laureati, M.; Bertoli, S.; Bergamaschi, V.; Leone, A.; Lewandowski, L.; Giussani, B.; Battezzati, A.; Pagliarini, E. Food neophobia and liking for fruits and vegetables are not related to Italian children’s overweight. Food Qual. Preference 2015, 40, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardello, A.V.; Pineau, B.; Paisley, A.G.; Roigard, C.M.; Chheang, S.L.; Guo, L.F.; Hedderley, D.I.; Jaeger, S.R. Cognitive and emotional differentiators for beer: An exploratory study focusing on “uniqueness”. Food Qual. Preference 2016, 54, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Rasmussen, M.A.; Prescott, J. Relationships between food neophobia and food intake and preferences: Findings from a sample of New Zealand adults. Appetite 2017, 116, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Spinelli, S.; Ares, G.; Monteleone, E. Linking product-elicited emotional associations and sensory perceptions through a circumplex model based on valence and arousal: Five consumer studies. Food Res. Int. 2018, 109, 626–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Xia, Y.; Le Blond, M.; Beresford, M.K.; Hedderley, D.I.; Cardello, A.V. Supplementing hedonic and sensory consumer research on beer with cognitive and emotional measures, and additional insights via consumer segmentation. Food Qual. Preference 2018, 73, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yik, M.; Russell, J.A.; Steiger, J.H. A 12-point circumplex structure of core affect. Emotion 2011, 11, 705–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Roigard, C.M.; Chheang, S.L. The valence x arousal circumplex-inspired emotion questionnaire (CEQ): Effect of response format and question layout. Food Qual. Preference 2021, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Roigard, C.M.; Jin, D.; Xia, Y.; Zhong, F.; Hedderley, D.I. A single-response emotion word questionnaire for measuring product-related emotional associations inspired by a circumplex model of core affect: Method characterisation with an applied focus. Food Qual. Preference 2020, 83, 103805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.L.; Davies, P.L.; E Boles, R.; Gavin, W.J.; Bellows, L.L. Young Children's Food Neophobia Characteristics and Sensory Behaviors Are Related to Their Food Intake, J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 2610–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzek, D.; Głąbska, D.; Lange, E.; Jezewska-Zychowicz, M. A Polish Study on the Influence of Food Neophobia in Children (10–12 Years Old) on the Intake of Vegetables and Fruits. Nutrients 2017, 9, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suntikul, W.; Agyeiwaah, E.; Huang, W.-J.; Pratt, S. Investigating the Tourism Experience of Thai Cooking Classes: An Application of Larsen's Three-stage Model. Tour. Anal. 2020, 25, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinard, J.-X. Sensory and consumer testing with children. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2000, 11, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudenbush, B.; Frank, R. Assessing Food Neophobia: The Role of Stimulus Familiarity. Appetite 1999, 32, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuorila, H.; Lähteenmäki, L.; Pohjalainen, L.; Lotti, L. Food neophobia among the Finns and related responses to familiar and unfamiliar foods. Food Qual. Preference 2000, 12, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrena, R.; Sánchez, M. Neophobia, personal consumer values and novel food acceptance. Food Qual. Preference 2013, 27, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazley, D.; Stack, M.; Walton, J.; McNulty, B.A.; Kearney, J.M. Food neophobia across the life course: Pooling data from five national cross-sectional surveys in Ireland. Appetite 2022, 171, 105941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozioł-Kozakowska, A.; Piórecka, B.; Schlegel-Zawadzka, M. Prevalence of food neophobia in pre-school children from southern Poland and its association with eating habits, dietary intake and anthropometric parameters: a cross-sectional study. Public Health Nutr 2018, 21, 1106–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szakály, Z.; Kovács, B.; Soós, M.; Kiss, M.; Balsa-Budai, N. Adaptation and Validation of the Food Neophobia Scale: The Case of Hungary. Foods 2021, 10, 1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firme, J.N.; de Almeida, P.C.; dos Santos, E.B.; Zandonadi, R.P.; Raposo, A.; Botelho, R.B.A. Instruments to Evaluate Food Neophobia in Children: An Integrative Review with a Systematic Approach. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kildegaard, H.; Olsen, A.; Gabrielsen, G.; Møller, P.; Thybo, A. A method to measure the effect of food appearance factors on children’s visual preferences. Food Qual. Preference 2011, 22, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, M.; Chaya, C.; Hort, J. Beyond liking: Comparing the measurement of emotional response using EsSense Profile and consumer defined check-all-that-apply methodologies. Food Qual. Preference 2013, 28, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhumiratana, N.; Adhikari, K.; Chambers, E., IV. The development of an emotion lexicon for the coffee drinking experience. Food Res. Int. 2014, 61, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S.C.; Meiselman, H.L. Development of a method to measure consumer emotions associated with foods. Food Qual. Preference 2010, 21, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.; Wai, P.P.; Koirala, P.; Bromage, S.; Nirmal, N.P.; Pandiselvam, R.; Nor-Khaizura, M.A.R.; Mehta, N.K. Food product quality, environmental and personal characteristics affecting consumer perception toward food. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1222760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).