1. Introduction

As a de facto standard for container environment management, Kubernetes simplifies deploying, managing, and scaling applications packaged in containers. With the growing dependence of organizations on Kubernetes for their production environments, it is crucial to prioritize and maintain optimal network performance. Conventional approaches to testing network bandwidth and latency typically require time-consuming manual procedures, are prone to errors, and are not readily adaptable to larger scales. This seminar paper presents a new approach to automating and coordinating the testing of network bandwidth and latency for Kubernetes container network interfaces. The methodology covers different technologies, performance profiles, and settings and utilizes Ansible.

Using Ansible to automate these tests offers substantial benefits compared to manual methods. Ansible, known for its robust automation and orchestration capabilities, guarantees consistent and replicable outcomes, minimizing the chances of human mistakes and facilitating quicker iterations. By implementing automation in the testing process, we can effectively manage intricate testing scenarios and extensive environments, which would be unfeasible to handle manually. Furthermore, automation enables the ongoing surveillance and evaluation necessary for upholding superior performance benchmarks in dynamic and scalable Kubernetes environments.

The practical impact of creating Ansible playbooks for this purpose is significant. Organizations can utilize these playbooks to obtain a more profound understanding of their network performance, rapidly detect and resolve bottlenecks, and enhance the efficiency of their Kubernetes deployments. As a result, there is an increase in application performance, better user experience, and improved operational efficiency. Therefore, implementing automated and coordinated network testing enhances the durability and strength of containerized applications, enabling organizations to accomplish their business goals confidently. This approach would be well-suited as an additional resource for performance evaluation on other platforms, like HPC. For example, contemporary research in scheduling HPC workloads might do well to implement this mechanism to get even more data on which to base ML-based Kubernetes scheduling decisions [

1].

Enhancements to Ethernet networks such as Priority-based Flow Control (PFC), RDMA over Converged Ethernet (RoCE), and Enhanced Transmission Selection (ETS) on a 100 Gb/s Ethernet network configured as a tapered fat tree have been researched in the past [

2]. The authors conducted tests that simulated various network operating conditions to analyze performance results. Their findings indicated that RoCE running over a PFC-enabled network significantly increased performance for bandwidth-sensitive and latency-sensitive applications compared to TCP. Additionally, they found that ETS can prevent network traffic starvation for latency-sensitive applications on congested networks. Although they did not encounter notable performance limitations in their Ethernet testbed, they concluded that traditional HPC networks still hold practical advantages unless additional external requirements drive system design.

Research has also been done regarding the Quality of Service (QoS) of Ethernet networks based on packet size, addressing the need for predictable, reliable, and guaranteed services in Ethernet networks, as standardized by IEEE 802.3 [

3]. Through simulations using the Riverbed modeler 17.5, they analyzed QoS metrics like end-to-end delay, throughput, jitter, and bit error rate for varying packet sizes, mainly focusing on sizes more significant than the 1500-byte Maximum Transmission Unit (MTU) of Ethernet. The results showed distinct variations in network performance based on packet size, highlighting the importance of managing these parameters for optimizing network QoS. In their study, the authors underscore the necessity of proper segmentation to improve performance and reduce packet loss and delay.

Evaluation has also been done for network processing performance and power efficiency over 10 GbE on Intel Xeon servers [

4]. Authors broke down per-packet processing overhead, revealing that driver and buffer release accounted for 46% of processing time for large I/O sizes and 54% for small I/O sizes, alongside data copy. They identified bottlenecks in the NIC driver and OS kernel using hardware performance counters. Furthermore, their study examined power consumption using a power analyzer and an external Data Acquisition System (DAQ) to profile components like CPU, memory, and NIC. These findings guided recommendations for a more efficient server I/O architecture to enhance performance and reduce power consumption in high-speed networks.

Performance measurements on 10 Gigabit Ethernet have been done using commodity hardware for high-energy physics experiments [

5]. This study evaluated maximum data transfer rates through a network link, considering limitations imposed by the memory, peripheral buses, and the processing capabilities of CPUs and operating systems. Using standard and jumbo Ethernet frames, they measured TCP and UDP maximum data transfer throughputs and CPU loads for sender/receiver processes and interrupt handlers. Additionally, they simulated disk server behavior in a Storage Area Network, forwarding data via a 10 Gigabit Ethernet link. Their findings emphasized the impact of jumbo frames in reducing CPU load and improving throughput.

Researchers also explored the implementation of Energy Efficient Ethernet (EEE) in HPC systems [

6]. The study analyzes EEE’s power savings and performance impact, showing that EEE can achieve up to 70% link power savings but may lead to a 15% increase in overall system power consumption due to performance overheads. The authors propose a “Power-Down Threshold” to mitigate this, reducing the on/off transition overhead from 25% to 2%, thus achieving overall system power savings of about 7.5%. Future research should optimize these strategies for better integration into HPC systems. They highlight the need for vendor-specific design decisions to fully leverage EEE in HPC environments, emphasizing the balance between energy savings and performance impacts. Challenges include addressing latency overheads and ensuring seamless integration with existing HPC infrastructure to maximize efficiency gains. Additionally, exploring adaptive mechanisms to further reduce power consumption without compromising performance is recommended.

The benchmarking study has been performed on four CNCF-recommended CNI plugins in a physical data center environment to evaluate their performance in Kubernetes [

7]. The study assessed latency and average TCP throughput across various Maximum Transmission Unit (MTU) sizes, the number of aggregated network interfaces, and different interface segmentation offloading conditions. Results were compared against a bare-metal baseline, revealing significant performance variations among the plugins. Kube-Router demonstrated the highest throughput, followed by Flannel and Calico. The findings underscore the importance of selecting appropriate CNI plugins to optimize Kubernetes network performance, particularly in environments with varying network interface configurations.

Other research has been done to analyze the performance of several CNI plugins, including in Kubernetes environments [

8]. Benchmarking tests conducted under various scenarios in this paper aimed to identify plugins that provided higher throughput and lower resource usage (CPU and memory), focusing on compute overhead. The study found that Kube-Router achieved the highest throughput in inter-host data exchanges, utilizing more than 90% of the nominal link bandwidth on TCP data transfer. Flannel and Calico followed in performance rankings. The research highlights the critical role of CNI plugin selection in optimizing Kubernetes network performance and resource efficiency.

A comprehensive assessment of various CNI plugins in Kubernetes, focusing on functionality, performance, and scalability, was done in 2021 [

9]. The authors compared open-source CNI plugins through detailed qualitative and quantitative measurements, analyzing overheads and bottlenecks caused by interactions with the datapath/iptables and the host network stack. The study highlighted the significant role of overlay tunnel offload support in network interface cards for achieving optimal performance in inter-host Pod-to-Pod communication. Scalability with increasing Pods and HTTP workloads was also evaluated, providing valuable insights for cloud providers in selecting the most suitable CNI plugin for their environments.

A study also focused on benchmarking different network visualization architectures in Kubernetes deployments tailored for telco data plane configurations. The study evaluated the performance of various architectures, including OvS-DPDK, Single Root Input Output Virtualization (SR-IOV), and Vector Packer Processing (VPP), leveraging industry-standard testing methodologies and an open-source testing framework [

10]. The research examined the effects of different resource allocation strategies on data plane performance, such as CPU-pinning, compute and storage resource variations, and Non-Uniform Memory Access (NUMA). The findings underscored the importance of optimizing resource allocation strategies to enhance data plane performance in telco Kubernetes deployments.

Researchers also investigated the sufficiency of Kubernetes’ resource management in isolating container performance, focusing on performance interference between CPU-intensive and network-intensive containers and multiple network-intensive containers [

11]. Their evaluation revealed that containers experience up to 50% performance degradation due to co-located containers, even under Kubernetes’ resource management. The study identified CPU contention, rather than network bandwidth, as the root cause of performance interference. The authors recommended that Kubernetes consider CPU usage of network-related workloads in resource management to mitigate performance interference and improve overall service quality.

A GENEVE (Generic Network Virtualization Encapsulation) tunnel in a multi-cloud environment at Trans-Eurasia Internetworking (TEIN) with sites in Malaysia and South Korea was deployed for a performance evaluation [

12]. The study highlighted GENEVE’s advantage in transferring larger payloads due to its smaller header size than other Layer 2 tunnels like GRE or VXLAN. They emphasized the importance of monitoring tools for network and instance performance forecasting. Machine learning algorithms can use data from these tools to predict optimal cloud and instance performance, ensuring resource sharing is efficient and not overutilized. Their implementation demonstrated that GENEVE tunnels could effectively facilitate communication and resource sharing between cloud instances.

Researchers also proposed an SDN-based optimization for VXLAN in cloud computing networks [

13]. They introduced an intelligent center to enhance multicast capabilities and facilitate VM migration within the VXLAN architecture. This new architecture addresses issues like signaling overhead during multicast periods and communication interruptions with migrating VMs. Their Mininet emulation demonstrated effective load balancing and highlighted the potential improvements in VXLAN’s multicast efficiency and VM migration facilitation. This work provides a blueprint for future cloud computing networks to enhance their performance and reliability.

The Segment-oriented Connection-less Protocol (SCLP), a novel Layer 4 protocol for existing tunneling protocols like VXLAN and NVGRE, was introduced and evaluated by researchers [

14]. SCLP was designed to enhance the performance of software tunneling by leveraging the Generic Receive Offload (GRO) feature in the Linux kernel, thereby reducing the number of software interrupts. The authors implemented VXLAN over SCLP and compared its performance with the original UDP-based VXLAN, NVGRE, GENEVE, and STT. Their results showed that SCLP achieved throughput comparable to STT and significantly higher than the other protocols without modifying existing protocol semantics, making it a viable alternative for high-performance software tunneling in data centers.

A research paper focused on improving the performance of Open vSwitch VXLAN in cloud data centers through hardware acceleration proposed a design that utilizes hardware acceleration methods to enhance the throughput performance of VXLAN [

15]. Their implementation demonstrated a fivefold increase in performance, achieving up to 12 Gbps throughput, compared to the 2 Gbps achieved by software-only solutions. This significant improvement underscores the potential of hardware acceleration in optimizing virtualized network environment performance in cloud data centers.

Researchers also detailed the VXLAN framework for overlaying virtualized Layer 2 networks over Layer 3 networks [

16]. This protocol addresses the need for scalable overlay networks within virtualized data centers, accommodating multiple tenants. VXLAN’s deployment in cloud service providers and enterprise data centers helps overcome the limitations of traditional VLANs. The protocol’s ability to encapsulate Ethernet frames in UDP packets allows for effective communication across IP networks, making it a crucial component in multi-tenant cloud infrastructures.

Challenges of measuring latencies in high-speed optical networks, particularly in scenarios requiring microsecond resolution, have also been researched [

17]. Researchers propose a software-based solution for latency measurement using high-performance packet engines like DPDK, which provides a cost-effective alternative to hardware-based methods. The paper introduces a novel concept of a convoy of packet trains to measure bandwidth and latency accurately, demonstrating the feasibility of their approach in 10 Gbit/s networks.

Researchers also debated a method for real-time measurement of end-to-end path latency in Software-Defined Networks (SDN) [

18]. They propose improving the looping technique by using IP TTL as a counter and measuring latency per link stored in the SDN controller. This method reduces redundant work and network overhead, providing accurate and efficient latency measurements. Their approach also includes a technique for measuring latency using queue lengths at network switches, further reducing network overhead.

Machine learning-based methods for estimating network latency that does not require explicit measurements have also been researched [

19]. ML is trained using the iConnect-Ubisoft dataset and uses IP addresses as the primary input to predict latencies between nodes. Performance evaluations show high accuracy and speed, with a significant proportion of measurements falling within a low estimation error margin. This method offers a fast and efficient alternative to traditional latency measurement techniques in large-scale network systems.

In 2021, researchers developed Formullar, a novel FPGA-based network testing tool designed to measure ultra-low latency (ULL) in highly precise and flexible networking systems [

20]. The tool comprises a hybrid architecture with hardware (FPGA) and software components, enabling accurate packet generation and timing control according to various traffic patterns. The hardware layer measures latency based on packet generation and reception timings, providing exact results. Evaluations indicate that Formullar achieves nanosecond precision at a bandwidth of 10 Gbps, making it suitable for time-sensitive applications requiring strict latency guarantees.

The paper “Catfish: Adaptive RDMA-Enabled R-Tree for Low Latency and High Throughput” presents an RDMA-enabled R-tree designed to handle large multidimensional datasets in distributed systems [

21]. The authors address performance challenges where R-tree servers are often overloaded while networks and client CPUs are underutilized. Catfish uses RDMA to balance workloads between clients and servers, employing two fundamental mechanisms: fast messaging, which uses RDMA writes to achieve low query latency, and RDMA offloading, which offloads tree traversal to clients. The adaptive switching between these methods maximizes overall performance. Experiments demonstrate that Catfish significantly outperforms traditional TCP/IP schemes, achieving lower latency and higher throughput on InfiniBand networks. Future research is suggested to optimize adaptive mechanisms further and explore deployment in diverse network environments.

In 2019, researchers proposed LLDP-looping, a novel latency monitoring method for software-defined networks (SDNs) [

22]. This method uses LLDP packets injected repeatedly in the control plane to determine latency between switches, providing continuous and accurate latency monitoring without dedicated network infrastructure. LLDP-looping minimizes overhead and achieves high measurement accuracy, with evaluations demonstrating over 90% accuracy compared to Ping in an SDN with link latency as small as 0.05 ms. The method can be applied to various networking scenarios with minimal modifications to SDN switches.

In 2020 [

23], a multimodal deep learning-based method for estimating network latency in large-scale systems was also researched. The system uses a deep learning algorithm to predict latencies from a small set of RTT measurements, significantly reducing the overhead associated with traditional measurement methods. The AI model achieved high accuracy, outperforming existing techniques, with a 90th percentile relative error of 0.25 and an average accuracy of 96.1%, demonstrating its effectiveness for large-scale network latency estimation.

In 2020, researchers proposed an ultra-low latency MAC/PCS IP for high-speed Ethernet, targeting data centers with high data throughput and transmission delay requirements. The study analyzed low-latency technologies and implemented a simulation experiment to measure latency on different platforms. The proposed MAC/PCS IP showed significant latency improvements compared to existing solutions, making it suitable for applications requiring ultra-low latency in high-speed Ethernet environments.

4. Methodology

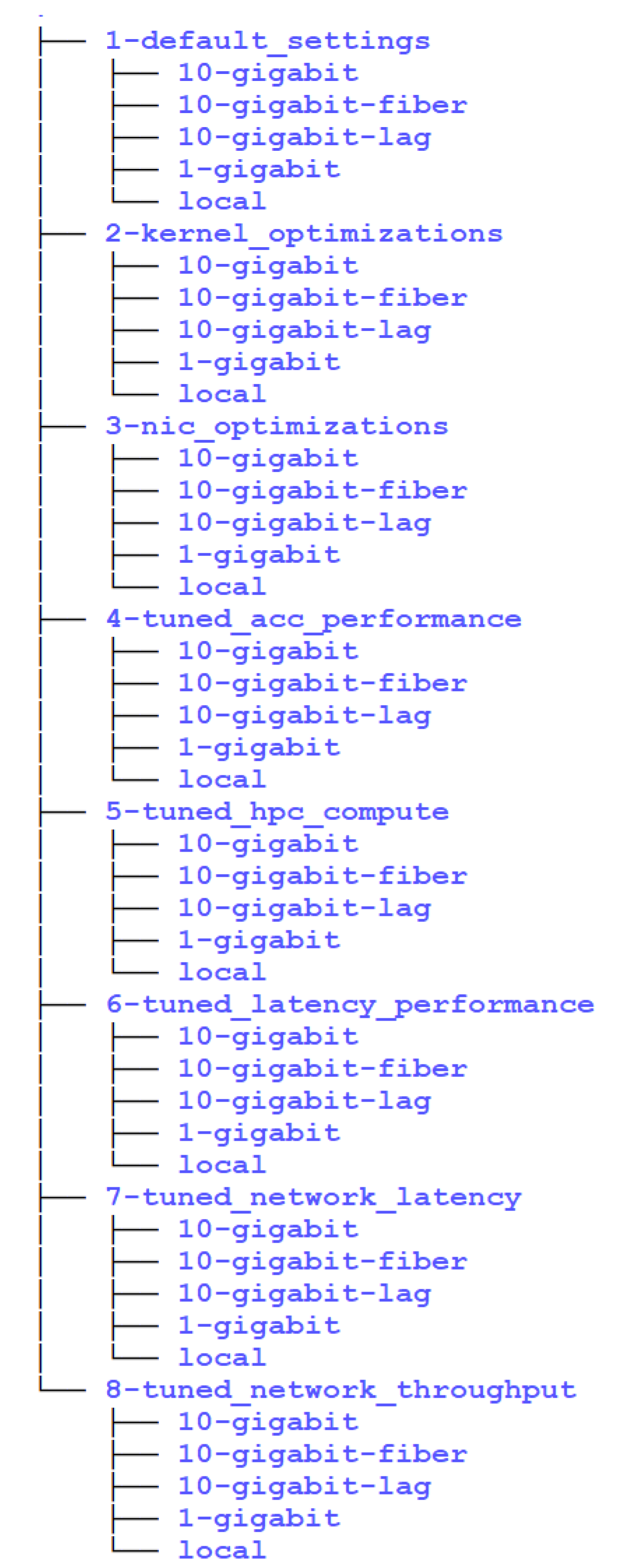

We based our methodology on default, built-in, and custom settings for performance profiles. We used five built-in performance profiles that are a part of the tuned package in Linux. We also made two custom profiles related to kernel optimizations and NIC optimizations. Every test was done five times to have some testing consistency and data. This is the list of all performance tuning profiles we used:

Default settings

Kernel optimizations

NIC optimizations

Tuned accelerator-performance profile

Tuned HPC-compute profile

Tuned latency-performance profile

Tuned network-latency profile

Tuned network-throughput profile

Then, we also paired that with different network standards:

Also, we paired that with multiple different packet sizes, with MTU values set to 1500 and 9000 (commonly used options):

64 bytes

512 bytes

1472 bytes

9000 bytes

15000 bytes

In terms of CNIs, we used:

Antrea 2.0.0

Flannel 0.25.4

Cilium 1.15.6

Calico 3.20.0

A stack of Ansible playbooks represented each set of tests in a separate directory, and we made a final playbook that included all the sub-directory playbooks, as can be seen in

Figure 1:

For these tests, we made a stack of Ansible playbooks that installed all the necessary components, reviewed all these performance evaluations, and stored their results in a MySQL database. Initially, we worked with a set of CSV files for test results but quickly realized this would become impractical, considering the amount of data we needed to analyze. We are talking about a couple of thousand results that testing parameters must also average out. Then, data in the MySQL database is used by Grafana to produce real-time performance graphs we can investigate. This also made for a setup that we could use in production environments. However, this research aimed to create an Ansible-based methodology for these performance evaluations that anyone can use. For this reason, we will publish our Ansible playbooks on GitHub so everyone can evaluate and use them. They will be accompanied by simple documentation so anyone can do the necessary configuration and run their tests.

A combination of shell scripts (a small minority) and Ansible playbooks was used to implement complete functionality for this paper. Shell scripts are used only in cases where they’re the most convenient way to implement certain functionality. Specifically, three shell scripts are used for three important tasks:

This is a portion of the script that parses logs—the first part of the script is all about setting some variables that are going to be used through the script:

# Listing all the test optimization levels

TEST_OPTIMIZATIONS=(“1-default_settings” “2-kernel_optimizations” “3-nic_optimizations” “4-tuned_acc_performance” “5-tuned_hpc_compute” “6-tuned_latency_performance” “7-tuned_network_latency” “8-tuned_network_throughput”)

# Listing all the test configurations for which the logs will be processed

TEST_CONFIGURATIONS=(“1-gigabit” “10-gigabit” “10-gigabit-lag” “fiber-to-fiber” “local”)

# Listing all the MTU values used in the tests

TEST_MTU_VALUES=(“1500” “9000”)

# Listing all the packet sizes used in the tests

TEST_PACKET_SIZES=(“64” “512” “1472” “9000” “15000”)

# Change this value according to your needs

TEST_LOG_DIRECTORY=“../logs/doktnet01/testing_results”

# Change this value according to your needs

PARSED_LOG_DIRECTORY=“../logs/parsed.”

Now that these variables are set, we can start the workload part of the script, contained in the next excerpt:

for test_optimization in ${TEST_OPTIMIZATIONS[@]};

do

for test_configuration in ${TEST_CONFIGURATIONS[@]};

do

bandwidth_logs_directory=“${TEST_LOG_DIRECTORY}/${test_optimization}/${test_configuration}/bandwidth”

# Create the bandwidth_logs_directory

mkdir -p “${PARSED_LOG_DIRECTORY}/${test_optimization}/${test_configuration}/bandwidth”

# Find all the protocol-specific logs

for protocol in “tcp” “udp”;

do

proto_bandwidth_logs_files=$(find $bandwidth_logs_directory -name “*${protocol}*” -print)

for bandwidth_log_file in ${proto_bandwidth_logs_files[@]};

do

# From the filename, get the mtu

log_file_mtu=$(echo $bandwidth_log_file | rev | cut -d ‘/’ -f1 | rev | cut -d ‘-’ -f3)

# From the filename, get the packet size

log_file_packet_size=$(echo $bandwidth_log_file | rev | cut -d ‘/’ -f1 | rev | cut -d ‘-’ -f5 )

# From the file get bandwidth

BANDWIDTH=$(tail -n4 ${bandwidth_log_file} | head -n1 | awk ‘{print $7 $8}’)

echo $BANDWIDTH >> “${PARSED_LOG_DIRECTORY}/${test_optimization}/${test_configuration}/bandwidth/${protocol}-mtu-${log_file_mtu}-packet-${log_file_packet_size}.log”

echo “PROTO: ${protocol} - ${bandwidth_log_file} - MTU: ${log_file_mtu} - packet: ${log_file_packet_size}”

done

done

latency_logs_directory=“${TEST_LOG_DIRECTORY}/${test_optimization}/${test_configuration}/latency”

# Create the latency_logs_directory

mkdir -p “${PARSED_LOG_DIRECTORY}/${test_optimization}/${test_configuration}/latency”

# Find all the protocol-specific logs

for protocol in “tcp” “udp”;

do

proto_latency_logs_files=$(find $latency_logs_directory -name “*${protocol}*” -print)

for latency_log_file in ${proto_latency_logs_files[@]};

do

# From the filename, get the mtu

log_file_mtu=$(echo $latency_log_file | rev | cut -d ‘/’ -f1 | rev | cut -d ‘-’ -f3)

# From the filename, get the packet size

log_file_packet_size=$(echo $latency_log_file | rev | cut -d ‘/’ -f1 | rev | cut -d ‘-’ -f5 )

# From the file get the latency

LATENCY=$(tail -n4 ${latency_log_file} | head -n1 | awk ‘{print $7 $8}’)

# Save the latency to the specific log file

echo $LATENCY >> “${PARSED_LOG_DIRECTORY}/${test_optimization}/${test_configuration}/latency/${protocol}-mtu-${log_file_mtu}-packet-${log_file_packet_size}.log”

echo “PROTO: ${protocol} - ${latency_log_file} - MTU: ${log_file_mtu} - packet: ${log_file_packet_size}”

done

done

done

done

As there are many sub-loops to this process for different configurations for each CNI tested, we had to ensure that the script goes through all possible optimizations and configurations.

The next script is all about running our pre-defined tests for all the possible scenarios:

# Listing all the test optimization levels

TEST_OPTIMIZATIONS=(“1-default_settings” “2-kernel_optimizations” “3-nic_optimizations” “4-tuned_acc_performance” “5-tuned_hcp_compute” “6-tuned_latency_performance” “7-tuned_network_latency” “8-tuned_network_throughput”)

# Listing all the test configurations

TEST_CONFIGURATIONS=(“1-gigabit” “10-gigabit” “10-gigabit-lag” “fiber-to-fiber” “local”)

# Define either operating-system or Kubernetes testing

TEST_ENVIRONMENT=“kubernetes”

# Define BANDWIDTH_SERVER -> endpoint to which the tests are pointed

BANDWIDTH_SERVER=“172.16.21.2”

# Define LATENCY_SERVER -> endpoint to which the tests are pointed

LATENCY_SERVER=“172.16.21.2”

for optimization in ${TEST_OPTIMIZATIONS[@]};

do

ansible-playbook -i inventory test_optimization/$optimization/setup.yml ;

for configuration in ${TEST_CONFIGURATIONS[@]};

do

ansible-playbook -i inventory tests/test_cleanup.yml ;

ansible-playbook -i inventory test_configuration/$configuration/test.yml --extra-vars “bandwidth_server=$BANDWIDTH_SERVER” --extra-vars “latency_server=$LATENCY_SERVER” --extra-vars “test_optimization=$optimization” --extra-vars “test_environment=$TEST_ENVIRONMENT”;

done

ansible-playbook -i inventory test_optimization/$optimization/cleanup.yml ;

done

The cleanup process is also included, but this tends to be very involved if it needs to be done manually. IP addresses can be changed easily for testing in different subnets - subnets chosen in the paper are used because they weren’t used in our environment.

The Ansible part of the methodology presented in this paper starts with some variable definitions, as visible from the code excerpt below:

---

results_dir: “/testing_results”

test_configuration: “10-gigabit”

test_devices:

- “ens2f0”

- “ens1f0”

mtu_values:

- 1500:

- 9000

packet_sizes:

- 64

- 512

- 1472

- 9000

- 15000

protocols:

- “tcp”

- “udp”

This will ensure that all the necessary tests and variables are available as one file, which can be included in other Ansible playlists, simplifying the process. Also, this file can be used to change the names of network interfaces used, simplifying the process if different interfaces need to be used.

The following Ansible code for TCP and UDP handles bandwidth testing:

- name: Test information

debug:

msg:

- “Testing bandwidth with the following configuration: “

- “ - Test optimization: {{ test_optim }}”

- “ - Test configuration: {{ test_config }}”

- “ - Test endpoint: {{ test_endpoint }}”

- “ - Test port: {{ test_port }}”

- “ - Test packet size: {{ test_packet_size }}”

- “ - Test mtu: {{ test_mtu }}”

- “ - Test duration: {{ test_duration }}”

- “ - Test protocol: {{ test_protocol }}”

- “ - Test environment: {{ test_env }}”

when: ansible_hostname == “{{ test_hostname }}”

- name: Testing bandwidth over TCP

shell: “iperf3 -c {{ test_endpoint }} -p {{ test_port }} -l {{ test_packet_size }} -t {{ test_duration }} >> {{ test_log_output }}”

when: ansible_hostname == “{{ test_hostname }}” and test_protocol == “tcp” and test_env == “operating-system”

- name: Testing bandwidth over UDP

shell: “iperf3 -c {{ test_endpoint }} -p {{ test_port }} -u -l {{ test_packet_size }} -t {{ test_duration }} >> {{ test_log_output }}”

when: ansible_hostname == “{{ test_hostname }}” and test_protocol == “udp” and test_env == “operating-system”

- name: Generate random string

set_fact:

random_name: “{{ lookup(‘community.general.random_string’, length=15,upper=false, numbers=false, special=false) }}”

- name: Testing bandwidth over TCP

become: false

k8s:

state: present

kubeconfig: “{{ kubeconfig }}”

definition:

apiVersion: batch/v1

kind: Job

metadata:

name: bandwidth-tcp-{{ random_name }}

namespace: default

labels:

app: bandwidth-tcp-test

mtu: “{{ test_mtu }}”

packet: “{{ test_packet_size }}”

optimization: “{{ test_optim }}”

config: “{{ test_config }}”

protocol: “{{ test_protocol }}”

spec:

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: bandwidth-tcp-test

mtu: “{{ test_mtu }}”

packet: “{{ test_packet_size }}”

optimization: “{{ test_optim }}”

config: “{{ test_config }}”

protocol: “{{ test_protocol }}”

spec:

nodeSelector:

kubernetes.io/hostname: doktnet01

containers:

- name: iperf3

image: hpc/cni-performance-testing:1.0

command: [“iperf3”, “-c”, “{{ test_endpoint }}”, “-p”, “{{ test_port }}”,”-l”,”{{ test_packet_size }}”, “-t”, “{{ test_duration }}”]

volumeMounts:

- name: testing-results

mountPath: /testing_results

volumes:

- name: testing-results

hostPath:

path: /testing_results

type: DirectoryOrCreate

restartPolicy: Never

backoffLimit: 4

delegate_to: localhost

when: test_protocol == “tcp” and ansible_hostname == “{{ test_hostname }}” and test_env == “kubernetes”

- name: Testing bandwidth over UDP

become: false

k8s:

state: present

kubeconfig: “{{ kubeconfig }}”

definition:

apiVersion: batch/v1

kind: Job

metadata:

name: bandwidth-udp-{{ random_name }}

namespace: default

labels:

app: bandwidth-udp-test

mtu: “{{ test_mtu }}”

packet: “{{ test_packet_size }}”

optimization: “{{ test_optim }}”

config: “{{ test_config }}”

protocol: “{{ test_protocol }}”

spec:

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: bandwidth-udp-test

mtu: “{{ test_mtu }}”

packet: “{{ test_packet_size }}”

optimization: “{{ test_optim }}”

config: “{{ test_config }}”

protocol: “{{ test_protocol }}”

spec:

nodeSelector:

kubernetes.io/hostname: doktnet01

containers:

- name: iperf3

image: hpc/cni-performance-testing:1.0

command: [“iperf3”, “-c”, “{{ test_endpoint }}”, “-p”, “{{ test_port }}”,”-u”,”-l”,”{{ test_packet_size }}”, “-t”, “{{ test_duration }}”]

ports:

- containerPort: 5201

name: iperf3

volumeMounts:

- name: testing-results

mountPath: /testing_results

volumes:

- name: testing-results

hostPath:

path: /testing_results

type: DirectoryOrCreate

restartPolicy: Never

backoffLimit: 4

delegate_to: localhost

when: test_protocol == “udp” and ansible_hostname == “{{ test_hostname }}” and test_env == “kubernetes”

- name: Waiting for the testing job to finish

pause:

seconds: 40

prompt: “Waiting 40 seconds for the testing job to finish”

echo: false

when: test_env == “kubernetes” and ansible_hostname == “{{ test_hostname }}”

Testing latency is similar to this code, but it utilizes a different command and a different set of parameters, as visible from the following code:

- name: Test information

debug:

msg:

- “Testing latency with the following configuration:”

- “ - Test optimization: {{ test_optim }}”

- “ - Test configuration: {{ test_config }}”

- “ - Test endpoint: {{ test_endpoint }}”

- “ - Test mtu: {{ test_mtu }}”

- “ - Test duration: {{ test_duration }}”

- “ - Test protocol: {{ test_protocol }}”

- “ - Test environment: {{ test_env }}”

when: ansible_hostname == “{{ test_hostname }}”

- name: Testing latency over TCP

shell: “netperf -H {{ test_endpoint }} -l {{ test_duration }} -t TCP_RR -v 2 -- -o min_latency,mean_latency,max_latency,stddev_latency,transaction_rate >> {{ test_log_output }}”

when: ansible_hostname == “{{ test_hostname }}” and test_protocol == “tcp” and test_env == “operating-system”

- name: Testing latency over UDP

shell: “netperf -H {{ test_endpoint }} -l {{ test_duration }} -t UDP_RR -v 2 -- -o min_latency,mean_latency,max_latency,stddev_latency,transaction_rate >> {{ test_log_output }}”

when: ansible_hostname == “{{ test_hostname }}” and test_protocol == “udp” and test_env == “operating-system”

- name: Generate random string

set_fact:

random_name: “{{ lookup(‘community.general.random_string’, length=15,upper=false, numbers=false, special=false) }}”

- name: Testing latency over TCP

become: false

k8s:

state: present

kubeconfig: “{{ kubeconfig }}”

definition:

apiVersion: batch/v1

kind: Job

metadata:

name: latency-tcp-{{ random_name }}

namespace: default

labels:

app: latency-tcp-test

mtu: “{{ test_mtu }}”

optimization: “{{ test_optim }}”

config: “{{ test_config }}”

protocol: “{{ test_protocol }}”

spec:

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: latency-tcp-test

mtu: “{{ test_mtu }}”

optimization: “{{ test_optim }}”

config: “{{ test_config }}”

protocol: “{{ test_protocol }}”

spec:

nodeSelector:

kubernetes.io/hostname: doktnet01

containers:

- name: netperf

image: hpc/cni-performance-testing:1.0

command: [“netperf”, “-H”, “{{ test_endpoint }}”,”-l”, “{{ test_duration }}”, “-t”, “TCP_RR”, “-v”, “2”, “--”, “-o”,”min_latency,mean_latency,max_latency,stddev_latency,transaction_rate”]

volumeMounts:

- name: testing-results

mountPath: /testing_results

volumes:

- name: testing-results

hostPath:

path: /testing_results

type: DirectoryOrCreate

restartPolicy: Never

backoffLimit: 4

delegate_to: localhost

when: test_protocol == “tcp” and ansible_hostname == “{{ test_hostname }}” and test_env == “kubernetes”

- name: Testing latency over UDP

become: false

k8s:

state: present

kubeconfig: “{{ kubeconfig }}”

definition:

apiVersion: batch/v1

kind: Job

metadata:

name: latency-udp-{{ random_name }}

namespace: default

labels:

app: latency-udp-test

mtu: “{{ test_mtu }}”

optimization: “{{ test_optim }}”

config: “{{ test_config }}”

protocol: “{{ test_protocol }}”

spec:

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: latency-udp-test

mtu: “{{ test_mtu }}”

optimization: “{{ test_optim }}”

config: “{{ test_config }}”

protocol: “{{ test_protocol }}”

spec:

nodeSelector:

kubernetes.io/hostname: doktnet01

containers:

- name: netperf

image: hpc/cni-performance-testing:1.0

command: [“netperf”, “-H”, “{{ test_endpoint }}”, “-l”, “{{ test_duration }}”, “-t”, “UDP_RR”, “-v”, “2”, “--”, “-o”,”min_latency,mean_latency,max_latency,stddev_latency,transaction_rate”]

ports:

- containerPort: 5201

name: netperf

volumeMounts:

- name: testing-results

mountPath: /testing_results

volumes:

- name: testing-results

hostPath:

path: /testing_results

type: DirectoryOrCreate

restartPolicy: Never

backoffLimit: 4

delegate_to: localhost

when: test_protocol == “udp” and ansible_hostname == “{{ test_hostname }}” and test_env == “kubernetes”

- name: Waiting for the testing job to finish

pause:

seconds: 40

prompt: “Waiting 40 seconds for the testing job to finish”

echo: false

when: test_env == “kubernetes” and ansible_hostname == “{{ test_hostname }}”

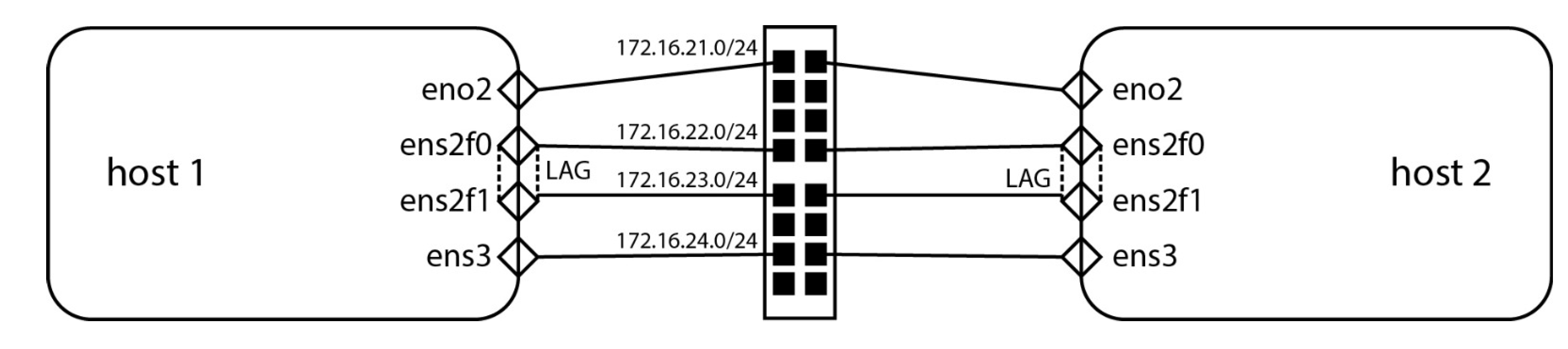

Some parts of the code need to be changed so that this code can work for every environment. However, the changes are minimal - hostnames, network interfaces, IP addresses, and code can be easily extended to test many hosts, but that mostly won’t be necessary. When designing a data center, the default design principle is to use the same hosts with the same capabilities to make them a part of the same QoS domain. For our testing environment, the network connectivity diagram is visible in

Figure 2.

In the excerpts of Ansible code presented in this paper, host1 refers to doktnet1, and host 2 refers to doktnet2, as these were the two assigned hostnames for two servers used to debug and test this methodology.