1. Introduction

At the utility scale, power generation systems such as photovoltaic (PV) generators or wind farms sell electricity to an AC grid in the long-term market via the daily or intraday market or through a power purchase agreement. At this scale, there are high-load consumers (towns, large factories, residential, commercial, or industrial areas) that can supply their load consumption via the utility grid and/or their own generating systems (e.g. PV and/or wind turbines with or without storage). We study large consumers such as load supply systems (LSS) with their own generating systems that include PV, wind turbines, and PHS storage. Further, we consider power-generating systems (PGS) comprising a PV generator and/or wind turbines with PHS storage, where the objective is maximizing the income generated by selling electricity to the grid. There is no auxiliary load consumption, i.e., the load for auxiliary components is considerably lower than the generated power. At the national utility-scale levels, grid stability and secure load supply suggest the necessity to increase energy storage in the generation mix with a greater presence of renewable energy and a lower weight in the mix of thermal power plants [

1]. High PV penetration affects the shape of day-ahead hourly price curves, lowering the daytime electricity prices [

2] (‘duck’ shape [

3]). In grid-connected systems, PHS is a type of storage that can be used for energy arbitrage: store electricity (pump water from the lower to the higher reservoir) during hours when electricity prices are low (off-peak hours, with low national demand) and use the stored energy (the water from the upper reservoir flows back down through a turbine and generates electricity) to inject electricity to the grid when the electricity price is high (peak hours, with high national demand). Thus, PHS can improve grid stability and load supply security and reduce costs in LSS or increase benefits in PGS. Energy arbitrage with PHS could be profitable (i.e. the increase in benefits attributed to price arbitrage could help compensate for its investment and operational costs) based on the hourly electricity prices, PHS efficiency, and capital expenditures (CAPEX), and operational expenditure (OPEX) costs, [

4]. Other PHS benefits for renewable power include curtailment reduction, fast and flexible ramping, frequency regulation, black start, and capacity firming [

3]. In addition, PHS can be used for other ancillary services such as steady-state voltage control, fast reactive current injections, and island operation capability [

5].

PHS is the dominant technology in electrical energy storage, with 97% of power and 99% of storage energy [

6]. The primary advantages of PHS as storage include its technological maturity, long useful life, high overall efficiency, rapid response, and strong power ramping. PHS is the most suitable technology for small islands and mass storage [

7], and it has been used for energy storage on islands with high renewable penetration, such as the El Hierro [

8] and Feroe islands [

9]. PHS is the most suitable technology for the seasonal storage of electrical energy. Hunt et al. (2020) [

10] showed that more than 79% of global electricity consumption in 2017 could be stored in PHS at a cost of less than US

$50/MWh. Existing PHS plants in electrical systems consume electricity during off-peak hours (pumping water) and inject electricity using the stored energy into the grid during peak hours, thereby contributing to grid services. Further, they operate in an open (one or more reservoirs are connected to a natural body of water) or closed loop (reservoirs are separate from natural waterways) [

7]. Traditionally, PHS operated at a fixed speed [

11] although variable-speed systems were gradually incorporated [

12,

13].

Mountainous countries show high potential for pumped storage hydropower (for example, Nepal [

14]). In many mountainous countries, and specifically in Spain, there is considerable potential for reusing traditional hydroelectric power plants through the aggregation of pumping systems, and there is also the possibility of expanding existing pumping plants by incorporating new groups with the same hydraulic infrastructure [

15]. Further, using low-head applications can make PHS usable in regions where it is not feasible traditionally [

5]. Underground pumped storage hydropower (UPSH, also called sub-surface pumped hydro storage, SSPHS) can avoid the environmental problems of installing new massive PHS plants using underground deposits in caverns or in abandoned mines (use of water from mine drainage for generating electrical energy through a reversible purification plant, thereby allowing the regeneration of mining environments). Although this technology is still in the development phase [

16], there are already projects for mining basins in Germany, the United Kingdom, Spain, China [

17] and USA [

18]. Other nonconventional technologies are also being evaluated, e.g. the use of canals or streams at different heights or deposits on the seabed [

19]. In addition, there are innovative projects that involve seawater pumping, in which the lower reservoir is the sea [

20,

21], with existing projects in Japan, Ireland and Hawaii [

18]. Renewable generation can be installed near existing PHS plants, operating in a similar way as a traditional power plant (energy management and arbitrage) and exploiting the existing grid connection infrastructure. Floating photovoltaic generation can also be added to the existing PHS reservoirs [

22].

Rehman et al. [

7] presented a technological review of renewable power storage using PHS. Barbour et al. [

23] reviewed the developments in relevant international electricity markets, and Lian et al. [

24] reviewed studies on hybrid renewable systems, including those that used PHS. Ali et al. recently investigated the drivers of and barriers to PHS [

25]. Javed et al. presented an extensive review of solar and wind power generation systems with PHS [

19].

The literature review indicates that most previous optimisation articles on PV-wind-PHS systems are related to off-grid systems. In addition, the literature review indicated that in PV-wind-PHS optimisation studies, the head dependence of water-power conversions and the variability of the friction losses and pump-turbine efficiency are neglected in the studies on PV-wind-PHS optimisation, assuming fixed constant values.

Toufani et al. performed a full review to address the uncertainty in the optimisation of PHS [

26], concluding that only a few studies considered uncertainties in PHS sizing, while even fewer studies focused on long-term planning.

The majority of studies on grid-connected PV-wind-PHS optimisation attempted to optimise the daily operation (short-term). Thus far, few studies optimised the size of the PV-wind-PHS system; however, they did not consider energy arbitrage, and only considered the grid to inject surplus energy (which cannot be used by the load that is not stored) or to import the energy required by the load that cannot be covered by the system.

Eliseu and Castro [

27] optimised the day-ahead operation of a Wind-PHS system with two different objectives: maximisation of the market profit or generation of constant firm output power. Abadie and Goicoechea [

1] presented a stochastic model for evaluating the effect of an optimally managed PHS power plant using certain price ranges for pumping and others for generation. They optimised energy management, but not component size, thereby considering the PHS global efficiency for a fixed value of 80%. Nassar et al. [

28] optimised the size of a PV-wind-PHS system for supplying the load of an urban community in Libia, injecting surplus energy into the grid (which cannot be used by the load or stored) and consuming the energy that cannot be supplied by the system from the grid. Variable penstock losses were considered (assuming laminar flow); however, the pump and turbine efficiencies were considered constant. In addition, fixed electricity prices were used to sell or purchase electricity from the grid. Gao et al. [

17] optimised the daily operation of a PV-wind-PHS (PHS mine in China), thereby reducing the volatility of the power injection to the grid and increasing the benefits; however, they did not consider variable losses in the pump, turbine, or penstock. Recently, Al-Masri et al. [

29] presented the optimisation (minimisation of grid-usage factor) of the different combinations of PV, wind, and PHS grid-connected systems with load consumption, which includes the variability of the friction losses and variable height, water reservoir evaporation, and seepage in the simulations; however, the pump and turbine efficiencies are considered as fixed values, and the energy management strategy is simple (injected into the grid only when there is surplus energy that cannot be stored in the reservoir), and the electricity grid price is a fixed value. Yin et al. [

30] presented a method for the multi-objective minimisation of power mismatch and the maximisation of revenues in offshore wind-PHSs, using accurate models for wind generation (including the wake effect) and considering hourly periods for the electricity price. However, simple models for the PHS were used (fixed efficiency for the pump-turbine performance including friction losses and no variable head).

Recently, Naval et al. [

31] showed the optimisation of the operation of a grid-connected PV-wind-PHS system that must supply a specific load consumption for one year. The optimisation of the monthly strategy maximise the benefits using PHS to meet the demand not covered by renewable sources and injecting surplus energy into the grid (not considering arbitrage). They used hourly prices of the Spanish wholesale electricity market in 2019, while considering fixed values for pump turbine performance, including friction losses and no variable head.

To the best of our knowledge, none of the previous studies considered the use of PHS for arbitrage in grid-connected systems with load consumption under a real-time pricing (RTP) scheme for the electricity price. In this study, we consider the use of PHS for arbitrage under electricity RTP, optimising the component size (PV, wind, pump turbine, and reservoir) and set points for arbitrage and management. Further, we used advanced models that have not been used in previous studies related to the optimisation of renewable – PHS systems. The main features of this work are provided below:

Both LSS, where the objective is minimising the electricity cost of the load supplied, and PGS, where there is no load and the objective is maximising income from selling electricity to the grid, are optimised.

Two different energy arbitrage systems are used: allowing or not buying energy from the grid during low RTP price periods to store energy in the pumped water. Further, the case without PHS is optimised for comparing the optimal results with and without PHS.

Each combination is simulated in time steps of 15 min during the lifetime of the system (typically 25 years).

Unlike most previous studies, we consider uncertainties in electricity prices, solar irradiation, and wind speed over the entire lifetime of a system. Further, an increase in load consumption during the system lifetime was considered.

The RTP electricity price is updated every year considering the effect of the increase in renewable power in the national electrical mix (‘duck curve’ of the electricity price profile).

The performance decay of equipment during the years of the system lifetime is considered.

Unlike most previous studies, we used accurate nonlinear models for all components and considered variable pump and turbine efficiencies (variable speed); variable head (attributed to changes in the water level in the upper and lower reservoirs); variable losses in penstocks, water reservoir evaporation, and seepage; and variable efficiency of the PV inverter.

We optimised not only the size of all components, but also four variables related to the load supply and energy management for arbitrage (which helps decide the priority to supply the load using the grid or storage, when to store energy, and when to inject energy into the grid).

A genetic algorithm (GA) based metaheuristic technique was used for efficient optimisation.

To the best of our knowledge, none of the previous studies included all these features simultaneously.

The remainder of this manuscript is organised as follows:

Section 2 presents the modelling approach for the simulation and optimisation of the system.

Section 3 presents the computational results and discussion, including the validation of the simulation approach compared to the results of a previous publication and the optimisation of representative cases with sensitivity analysis. Finally, the conclusions are presented in Section 4.

2. Modelling Approach

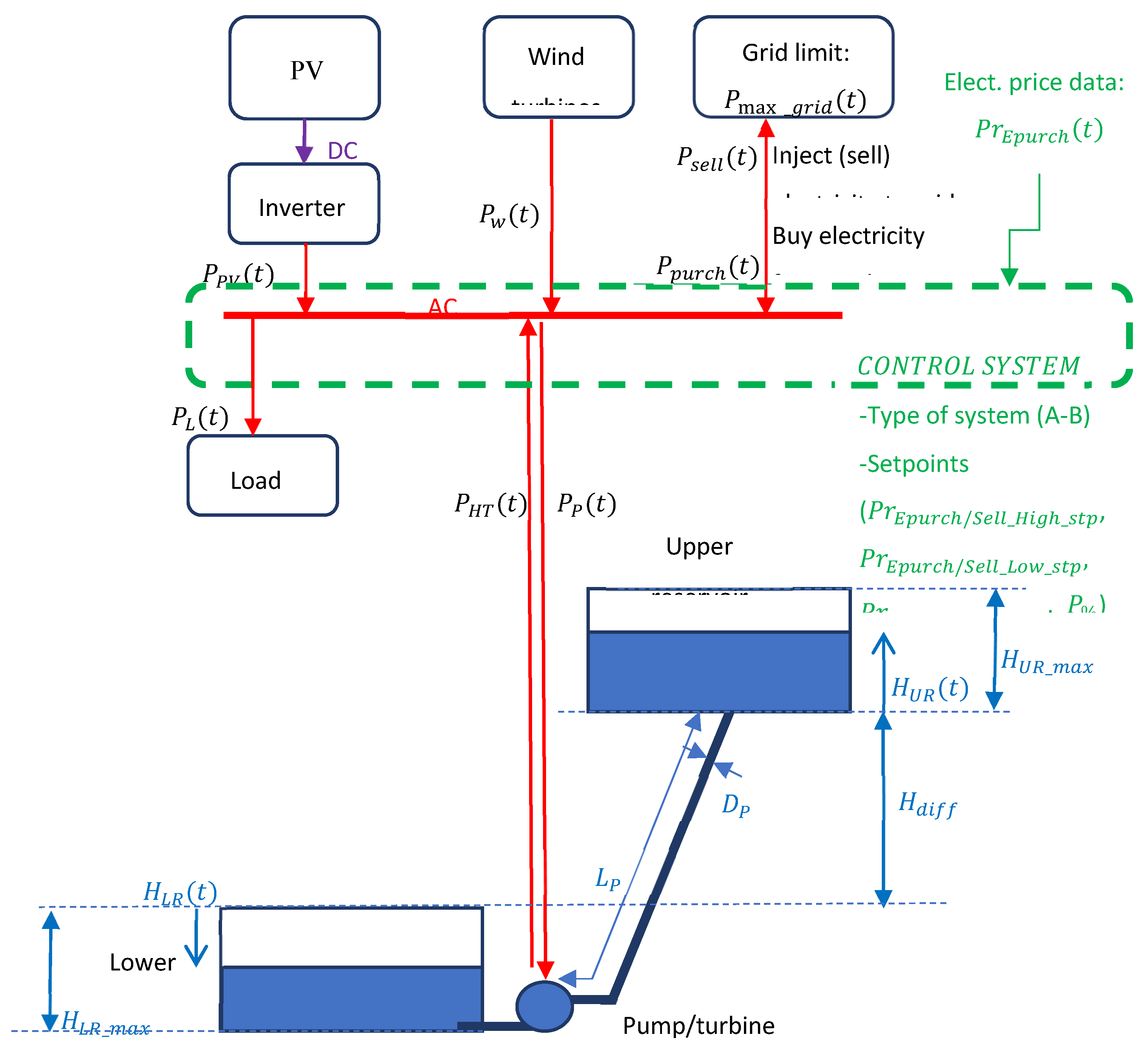

Figure 1 shows the PV-wind-PHS. In this study, we expanded the megawatt hybrid maximizing by genetic algorithms (MHOGA) [

32,

33] software to perform simulations and optimisations.

We consider two systems:

LSS (

Figure 1): In this system, electrical load

must be supplied during every time step

t of the entire system lifetime. The system can be applied to a small town or residential, commercial, or industrial area. Electricity is supplied by means of the grid and renewable-PHS system, and the objective is maximizing the electricity cost (maximizing net present cost, NPC) of the load supplied.

PGS: In such systems, there is no load demand (or the load demand is very low only for the auxiliary consumption of the power system). The objective of the owner of the renewable-PHS power-generating system is maximizing the benefits obtained by selling electricity to the grid (maximizing the net present value, NPV). It would be a specific case of LSS considering no load ( ) or low load (for the auxiliary consumption of the PGS).

Two different types of systems were considered for energy arbitrage (

Table 1): Type A (allowed to purchase energy from the grid for energy arbitrage) and Type B (not allowed to purchase energy from the grid for energy arbitrage; purchase is allowed only for the load supply when it is required).

Once the system type was defined, different combinations of components (PV generator, wind turbines, pump turbine, and reservoirs) and control strategies were simulated during the system lifetime in time steps of 15 min and evaluated.

For each time step, the energy balance was determined based on the type of system and different variables. Input variables for each time step

t are (

Figure 1) maximum grid power

, load consumption

, PV output power

, wind turbines output power

(W), water volume of the upper and lower reservoirs,

and

(m

3), electricity price (purchase to the AC grid price and sell to the AC grid price), and

and

(€/kWh).

The set points are listed below:

High limit of electricity price for energy arbitrage (). If the electricity price (purchase or sale price, depending on project type A or B, respectively) is higher than this limit, the priority is injecting electricity into the grid, including hydropower generation, at its maximum allowed power.

Low limit of electricity price for energy arbitrage (). If the electricity price is lower than this limit, a pump is used to store water in the upper reservoir. Depending on the type of project (A or B), the pump runs at its rated power (consuming electricity from the grid, if needed) or with the power supplied by the net renewable power.

Limit of the purchase price for the electricity to supply the net load using the grid (if the electricity price is lower than this setpoint) or hydro turbine (if the price is higher): . This setpoint has no meaning in the PGS if there is no load. In addition, during the time steps when arbitrage (charge or discharge) was selected, this setpoint had no meaning.

Minimum hydro turbine load: Minimum percentage of the hydro turbine rated power to supply the net load ().

For each time step, the net load

is defined as the load minus the renewable power.

The net renewable power is expressed as

The energy arbitrage performances of the two types of systems are explained as follows (see

Table 1).

Type A: Energy arbitrage is considered during each time step. If the purchase electricity price is higher than the high set point () → ‘arbitrage: discharge’, the priority is injecting the (sell) electricity to the grid (net renewable generation + hydro turbine at maximum power). If the purchase electricity price is lower than the low set point () → ‘arbitrage: charge’, the priority is storing the energy (to pump water with renewable surplus power). If the renewable surplus power is lower than the pump nominal rated power (), the difference is purchased from the grid to run the pump at rated power. If the purchase electricity price is between the two setpoints → ‘no arbitrage’ (dead band for arbitrage): if there is surplus power, it is sold to the grid; if there is net load, it is covered by the hydro turbine only if the purchase electricity price is higher than the load set point limit () and the net load is higher than a specific percentage of the turbine nominal rated power ( > ). In this way the hydro turbine is used to supply the net load (using stored energy) only when the purchase price and power are high (avoiding turbine low efficiency at low power).

Type B system (not allowed to purchase electricity from the grid for arbitrage). Unlike Type A, it is not allowed to purchase electricity from the grid for arbitrage in this system (purchasing electricity from the grid is allowed only to supply the net load). In this type of system, the selling price is the electricity price used for comparison with arbitrage setpoints. For each time step, the energy arbitrage operates as follows: If the sell electricity price is higher than the high set point () → ‘arbitrage: discharge’, the priority is injecting (sell) electricity to the grid (net renewable generation + hydro turbine maximum power). If the sell electricity price is lower than the low set point () → ‘arbitrage: charge’, the priority is storing energy (to pump water just with the renewable surplus power, not buying electricity to the grid). If the sell electricity price is between the two setpoints → ‘no arbitrage’ (dead band for arbitrage): same as in type A.

For both cases, the maximum grid power () limits the power purchased and sold to the AC grid.

1.1. Simulation

Each combination of components and control strategy is simulated during the lifetime of the system in steps of 15 min.

1.1.1. PV Model

Global hourly irradiation data over the tilted surface

(W/m

2) can be imported from the measured data or downloaded from the PVGIS [

34], Renewables Ninja [

35], and NASA [

36] databases. The uncertainty is considered in the irradiance for each hour (h) of each year (y) of the system lifetime

, which is obtained by multiplying

by a random number

that follows a normal distribution with mean 0 and standard deviation

. Given the hourly irradiance, the irradiance in 15-min time steps G(t) (W/m

2) is calculated using a first-order autoregressive function.

The AC PV generator output at time

t (year

y),

(W), represents the minimum of the output of the PV (considering the inverter efficiency,

) and the PV inverter-rated power (nominal AC output power,

).

where , , , α, ), and , and (°C) represent the rated DC peak power of the PV generator, PV annual reduction factor due to degradation, efficiency factor (dirt, wire losses…), power temperature coefficient (%/°Cirradiance and cell temperature under standard test conditions (1000 W/m2 and 25 °C), respectively, and

cell temperature during time

t, respectively, which is expressed as

where (°C) represents the ambient temperature and NOCT (°C) represents the nominal operation cell temperature.

1.1.1. Wind Turbine Model

Hourly wind speed data for an entire year can be imported or downloaded from online databases. The wind speed for each 15-min time step was obtained using a random number

(to consider the uncertainty) and first-order autoregressive function model. If the hub height

zhub (m) is different from the anemometer height

zanem (m), the wind speed at the hub height

whub(

t) (m/s) is obtained by converting the measured wind speed

w(

t) (m/s) at the anemometer height considering the surface roughness length

z0 (m) based on

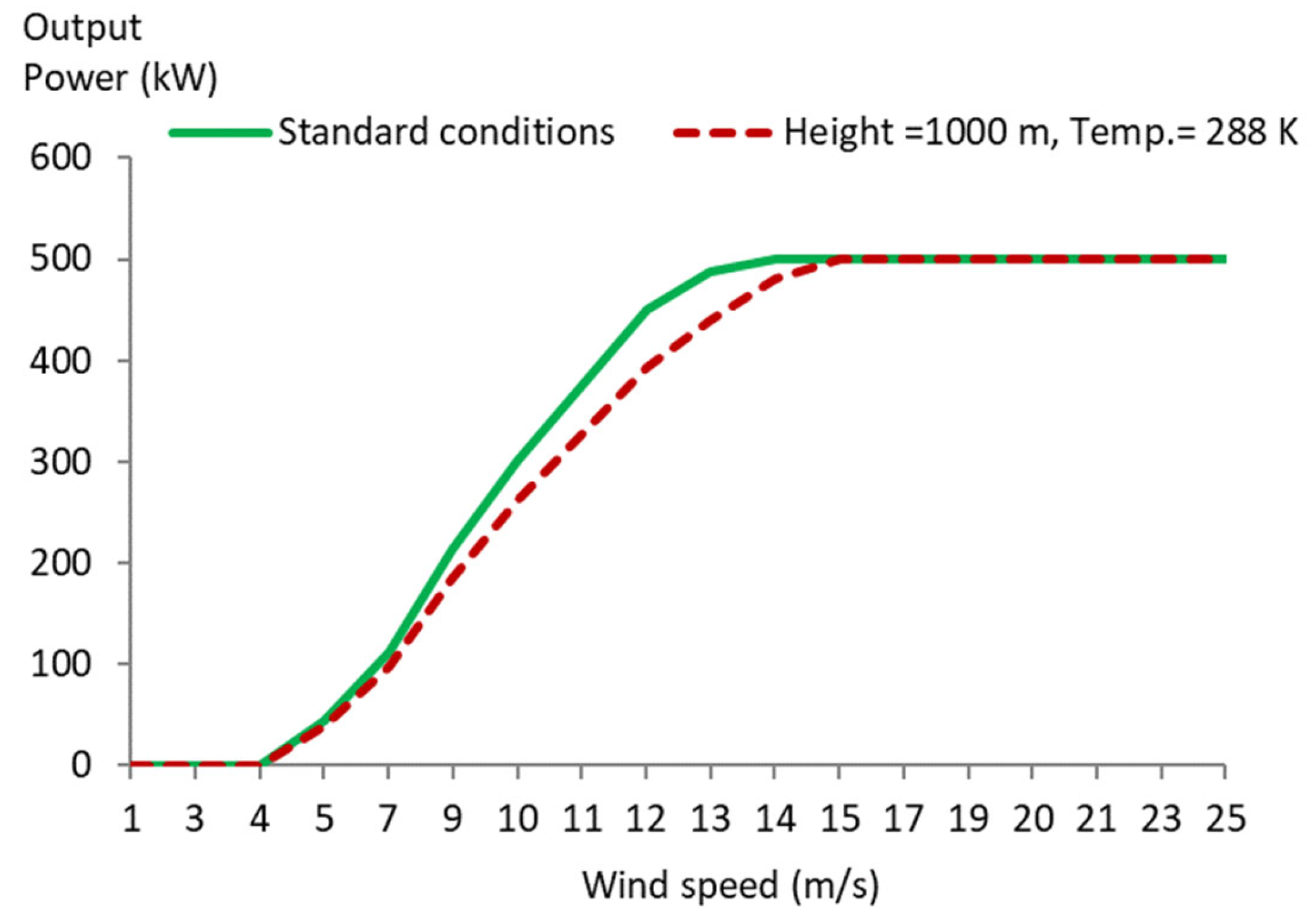

The wind turbine output power curve supplied by its manufacturer is measured in standard conditions (temperature 288.15 K, sea level, and air density

ρair_0 = 1.225 kg/m

3). For each time step, the wind turbine output curve was converted to the air density of the time step

ρair(t) (kg/m

3) by multiplying with the relationship

ρair(t)/

ρair_0. Turbines with pitch control maintained their nominal power (

) without any changes, as shown in

Figure 2.

The wind turbine output power

(W) at time

t for each wind speed

is obtained as

where

represents the output power curve (power vs. wind speed

) of the wind turbine when it is new (year 0) under standard conditions;

represents the wind turbine annual reduction factor owing to degradation ([

37]);

represents the efficiency owing to losses in wires, switches, etc.; and

represents the rated wind speed of the wind turbine (in

Figure 2, 15 m/s).

Several wind turbines can work in parallel; in this case, the total output power is calculated considering the wake effect model proposed by González-Longatt [

38].

1.1.1. Pump Model

Variable-speed reversible pump turbines are considered in this study. For each time step, the control strategy determines the value of the pump input power

(W), which cannot be higher than the nominal rated power (

) depending on the type of system and on the different variables (

Section 2,

Table 1). The pump flow rate (water taken from the lower reservoir and stored in the upper reservoir) depends on the pump efficiency and head. The pump model [

39] calculates the flow rate of the pump

(m

3/s) as a function of the input power (first term in Equation 8). The second term of Equation 8 shows that the pump flow rate cannot exceed the nominal flow rate

(m

3/s). The third and fourth term of that equation show that, at the end of the time step (after

= 15 · 60 = 900 s, which corresponds to the time step of 15 min) the lower reservoir volume

(m

3) cannot be lower than its minimum allowed

(m

3), and the upper reservoir volume

(m

3) cannot be higher than its maximum allowed

(m

3).

where

represents the pump efficiency (which includes the motor efficiency) and is a function of

, which can be found in the pump technical datasheet;

ρ represents the water density (

ρ = 997 Kg/m

3 at 25 °C),

g represents the gravity acceleration (

g = 9.81 m/s

2), and

(m) represents the pump head, which is the sum of the static head

and head loss of the pump mode

.

The static head is the difference in the water level of the upper and lower reservoirs, which considers the difference in heights between the minimum level of the upper reservoir and maximum level of the lower reservoir (

), and the variations over the minimum level of the upper reservoir

and below the maximum level of the lower reservoir

(

Figure 1).

The water level in the upper reservoir

can be calculated by assuming that the reservoir has a cuboid shape.

where

represents the maximum height of the water in the upper reservoir (m). The variation below the maximum level of the lower reservoir

can be calculated by assuming that the lower reservoir has a cuboid shape given by

where

represents the maximum volume of the stored water in the lower reservoir (m

3) and

represents the maximum height of the water in the upper reservoir (m).

The head loss of the pump mode

represents the hydraulic losses of the pump mode because of the friction between the water and inner surface of the pipes and fittings.

is calculated as a function of

using the Darcy–Weisbach equation [

39]

For laminar flow, the friction factor (

f) is calculated as x

where

represents the Reynolds number.

For turbulent flow (normal in PHS systems), an approximation of the Colebrook equation (Haaland equation) is used.

where

,

,

and

, ε, and

represent the total resistance coefficient, coefficient resistance of the pipe, coefficient resistance of the fittings, water speed (m/s), pipe diameter and pipe length between the pump and the reservoir (m), absolute roughness (m), and dynamic viscosity of water (Pa·s), which depends on temperature, respectively.

1.1.1. Turbine Model

The turbine is the same as the pump (pump-turbine reversible machine); therefore, the turbine pipe diameter () and length () are the same as those defined for the pump ().

For each time step, the control strategy determines the hydro turbine output power

(W), which is limited to the maximum value

.

The maximum hydro turbine output is limited by its nominal rated power

(W) and nominal flow rate

(m

3/s). Further, at the end of the time step, the lower reservoir cannot exceed its maximum volume

(m

3) and the upper reservoir volume cannot be lower than its minimum value

(m

3).

The turbine flow rate (obtained from the upper reservoir and stored in the lower reservoir) depends on the turbine efficiency and turbine head. The turbine model [

39] calculates the flow rate of the turbine

(m

3/s) as a function of the input power, which cannot be higher than the nominal flow

(m

3/s). At the end of the time step, the lower reservoir cannot exceed

and the upper reservoir volume cannot be lower than

.

where

is represents turbine efficiency (which includes the multiplier efficiency and the generator efficiency) and is a function of the flow, which can be found in the turbine technical manual. Further,

(m) represents the turbine head, which is calculated as the static head in turbine mode

minus the head loss in the turbine mode

.

A pump-turbine reversible machine is considered, the static head is defined in the same manner as that for the pump (Equation (10)). The loss in the turbine mode is calculated using the same equations as those for the loss in the pump mode (Equations (13)–(19)) using the turbine flow rate ().

1.1.1. Water Volume in the Reservoirs

The water volumes (m

3) in the upper and lower reservoirs at the next time step are calculated as

where

and

(m

3) represent the incoming water minus the outgoing water from the reservoir (apart from the pump and turbine flow) for the upper and lower reservoirs, respectively, which can be calculated based on the geographical features of the area, including losses caused by evaporation and seepage.

The maximum stored energy depends on the maximum volume of the upper reservoir and static head, and it is given by

where

represents the average static head in the turbine mode.

The duration of the upper reservoir (

) represents the time (h) at which the upper reservoir can supply the nominal flow of the turbine (PHS time of full-capacity operation in generation mode).

1.1. Optimisation

The software simulates different combinations of possible components in time steps of 15 min during the system lifetime

LifeS (usually 20–25 years, defined by the user): the PV generator (including its own inverter), wind turbine group (size and number of wind turbines), pump-turbine reversible unit, and water reservoir size. Further, it considers four set points for control, as detailed in

Section 2 and

Table 1.

Considering a system lifetime of 25 years, the number of time steps simulated for each combination is 876,000 (25 × 365 × 24 × 4). Considering the nonlinear characteristics of many components (PV inverter efficiency, wind turbine output curve, pump-turbine efficiency, penstock losses, etc.), optimisation cannot be performed by the classical methods or MILP. In this study, GA metaheuristic techniques were used for the optimisation. The two GA were considered in the optimisation: a main algorithm to determine the optimal configuration of the components, and a secondary GA to determine the optimal control.

Five variables are optimised with the main GA.

where

,

,

,

, and

represent the code for the PV generator type (including its own inverter), code for the wind turbine type, number of wind turbines in parallel, code for the pump-turbine reversible machine type, and water storage duration defined in Equation 28, respectively. In each case, the penstock diameter was calculated to obtain the specific water speed for the nominal flow of the pump/turbine.

For each combination, the maximum reservoir volume is calculated as follows:

is obtained from the

(Equation (28)), and the

is proportional to the upper reservoir by a factor (

) that depends on the design conditions.

The secondary GA optimises the control strategy, which is composed of four setpoint variables (explained in

Section 2).

For each combination of the main GA, the secondary GA is run to obtain its optimal control, simulation, and evaluation of a number of combinations of the four set-point variables.

In the LSS, the objective of the optimisation is to find a combination of components and a control strategy to minimise the NPC

Under the constraint that the unmet load

(%) must be lower than the maximum unmet load allowed (

),

In the PSS systems, the objective of optimisation is to find a combination of components and a control strategy to maximise the NPV.

where NPV is the opposite of the NPC.

1.1. Economic Results Calculation

The NPC of each combination of components and the evaluated control strategy is computed considering all costs during the system lifetime: the CAPEX and OPEX of all components of the system, their replacement cost during the system lifetime, and cost of electricity purchased from the AC grid. All cash flows are converted to the present moment using a discount rate. In addition, the income from selling the electricity to the grid during the lifetime of the system was considered (negative values as income) [

33].

where

I and

Inf represent the annual nominal interest or discount rate and annual inflation rate, respectively;

OPEXj represents the annual OPEX of component

j at the beginning of the system lifetime (year 0). For the pump turbine, we consider the start-up cost (a cost is considered each time the pump turbine starts to work), which will be added to the annual OPEX.

NPCrep_j represents the sum of the present costs because of the replacement of component

j (PV, wind turbine group, pump/turbine, and reservoir) during the system lifetime minus the incomes attributed to the residual life of all components at the end of the system lifetime.

Incsell_E_y represents the income from the electricity sold to the AC grid during year

y.

Costpurch_E_y represents the cost of electricity purchased from the AC grid during year

y (1…

LifeS).

TAXy represents the cost of payable taxes related to project benefits: revenues minus operational expenses, interest, depreciation, and amortisation multiplied by the applicable tax rate

TR (%), calculated as shown in ref. [

40].

In the LSS, the levelised cost of energy (LCOE) is the cost per kWh consumed and sold to the grid.

where

and

represent the 15-min load and energy sold to the grid during year

y, respectively.

In the PGS, the net present value (NPV) of each combination of components and the control strategy evaluated is the opposite of the NPC.

In PGS systems, the LCOE is the generation cost of kWh injected into the grid, which is calculated as

where represents the sum of the total present costs of the system over its lifetime (NPV minus income).

1.1. Electricity Price

The PV-wind-PHS system is assumed to be an electricity price taker, and a real-time pricing (RTP) model is considered. The effect of the change in the hourly profile of the day caused by the increase in PV penetration (‘duck curve’) and the increase in wind penetration are considered for estimating the future electricity prices. The selling electricity price in year

y is calculated as [

41]

where

represents the sell electricity price of hour

h (0… 8760) of year

y.

represents the PV factor to consider the price reduction in the future hourly price profile attributed to an increase in PV penetration ‘duck curve’ depending on the average irradiance of hour

h of year 1

(W/m

2).

represents the wind factor to consider the price reduction in the future hourly price profile caused by an increase in wind generation and

represents the annual inflation rate for the electricity price. The uncertainty in electricity price was considered using a random number with a mean

and standard deviation

for calculating the annual electricity price inflation rate for each year

y.

The price calculated in the previous equation refers to year 0 (beginning of the system lifetime); therefore, the price considered for year will be updated (increased due to inflation) by a factor . The purchase price of electricity is affected similarly. The electricity (purchase or sell) price set points are updated each year with electricity price inflation so that the electricity price of each hour of each year is compared to their updated values.

Author Contributions

Rodolfo Dufo-López: Conceptualisation, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualisation, Writing – Original draft, Writing – Review & editing. Juan M. Lujano-Rojas: Conceptualisation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualisation, Writing – Review & editing. Rodolfo Dufo-López: Conceptualisation, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualisation, Writing – Original draft, Writing – Review & editing. Juan M. Lujano-Rojas: Conceptualisation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualisation, Writing – Review & editing. Rodolfo Dufo-López: Conceptualisation, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualisation, Writing – Original draft, Writing – Review & editing. Juan M. Lujano-Rojas: Conceptualisation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualisation, Writing – Review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

PV-wind-PHS system.

Figure 1.

PV-wind-PHS system.

Figure 2.

Wind turbine output curve of a 500-kW wind turbine with pitch control. Standard (green curve) and other conditions (dotted red curve).

Figure 2.

Wind turbine output curve of a 500-kW wind turbine with pitch control. Standard (green curve) and other conditions (dotted red curve).

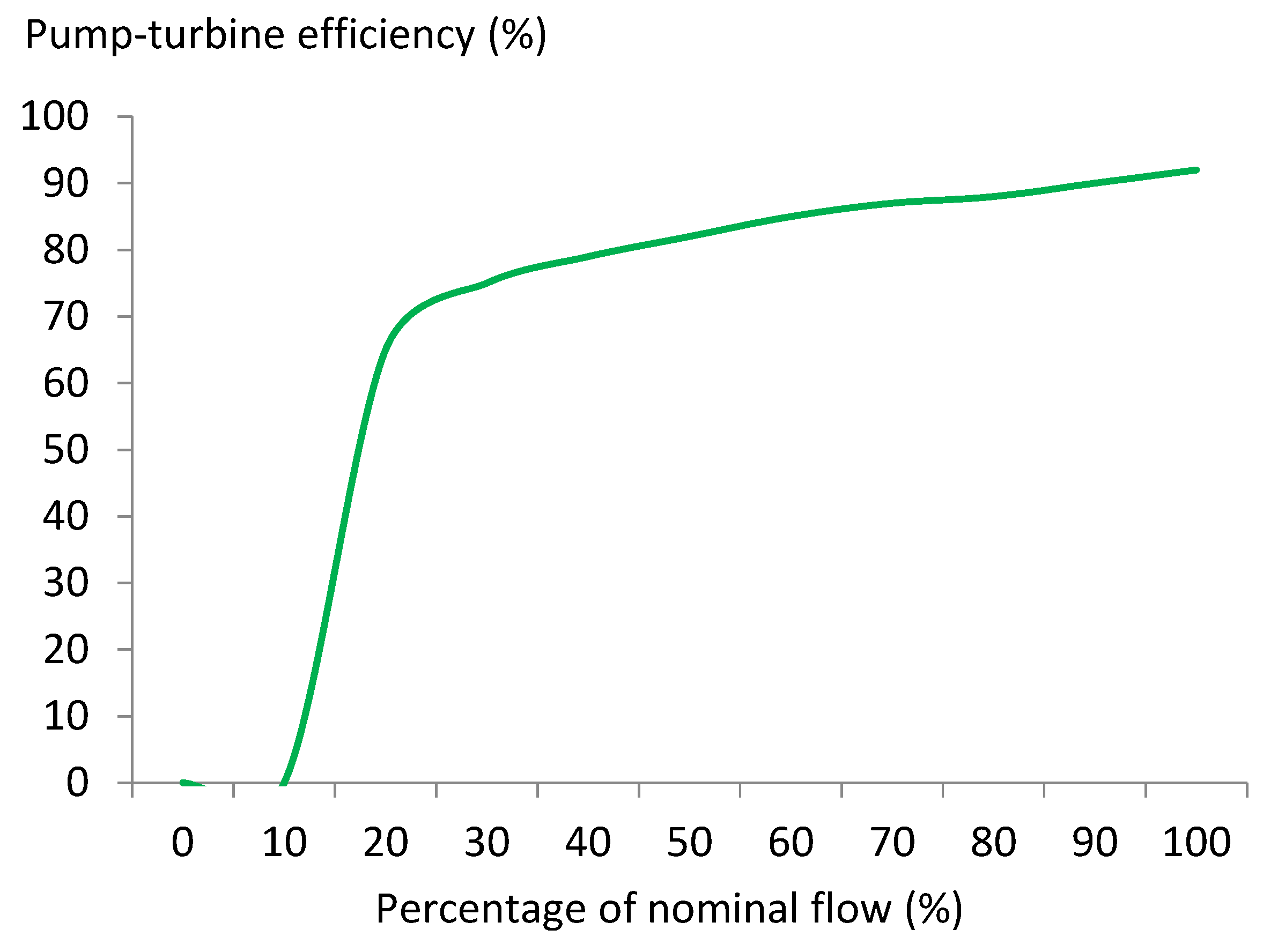

Figure 3.

Efficiency (%) vs. maximum flow (%) of the pump-turbine reversible machine considered in this study.

Figure 3.

Efficiency (%) vs. maximum flow (%) of the pump-turbine reversible machine considered in this study.

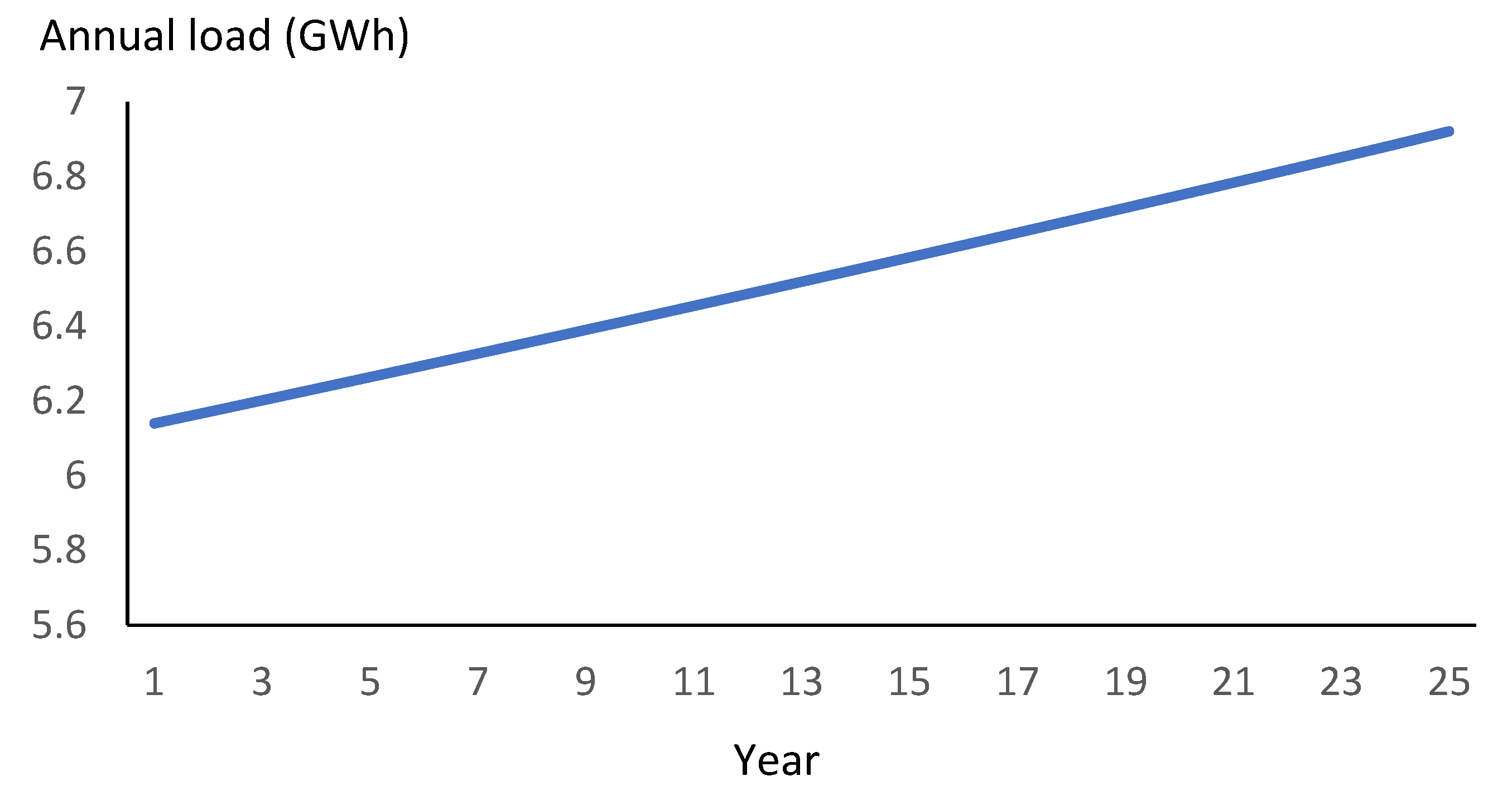

Figure 4.

Annual load consumption during the years.

Figure 4.

Annual load consumption during the years.

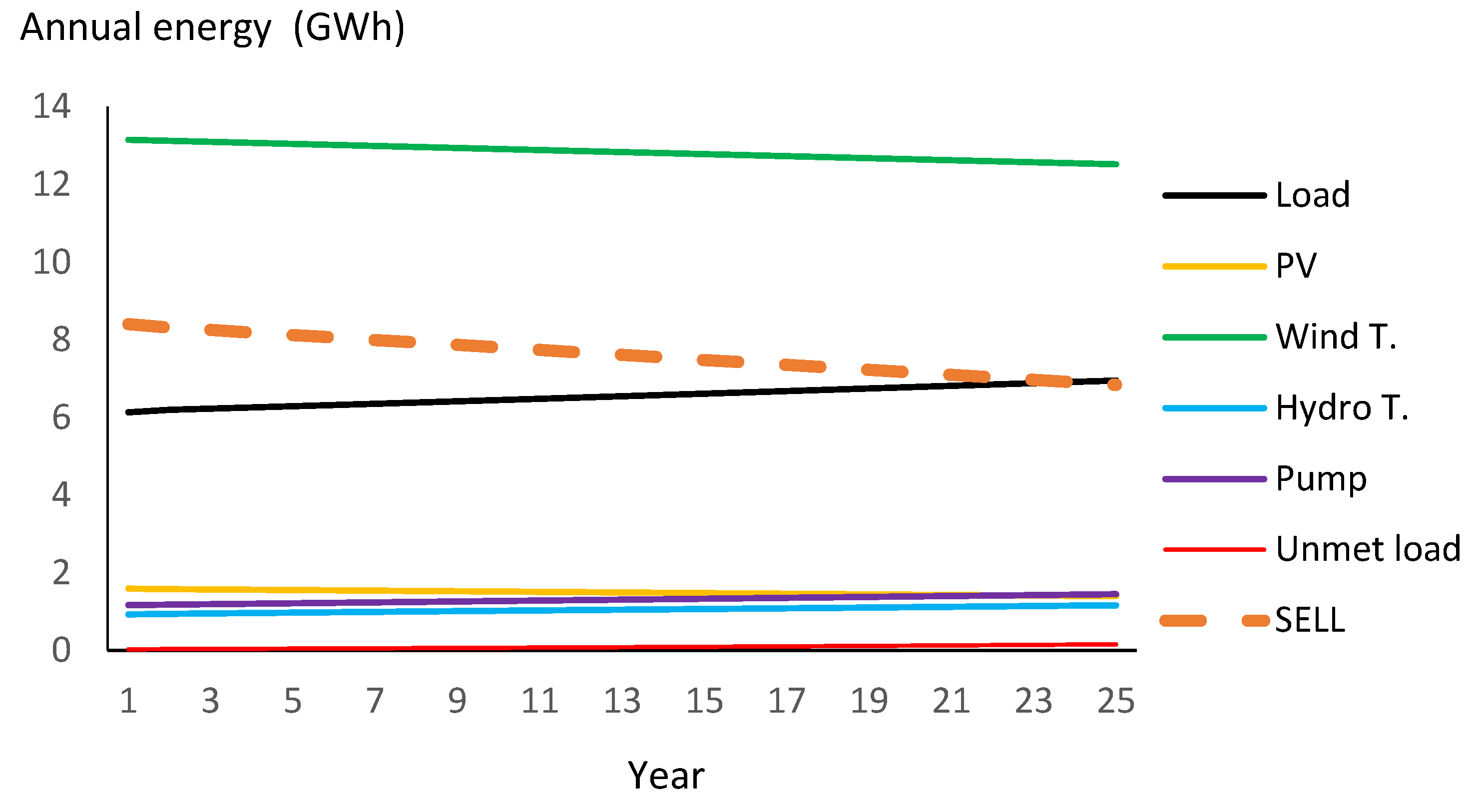

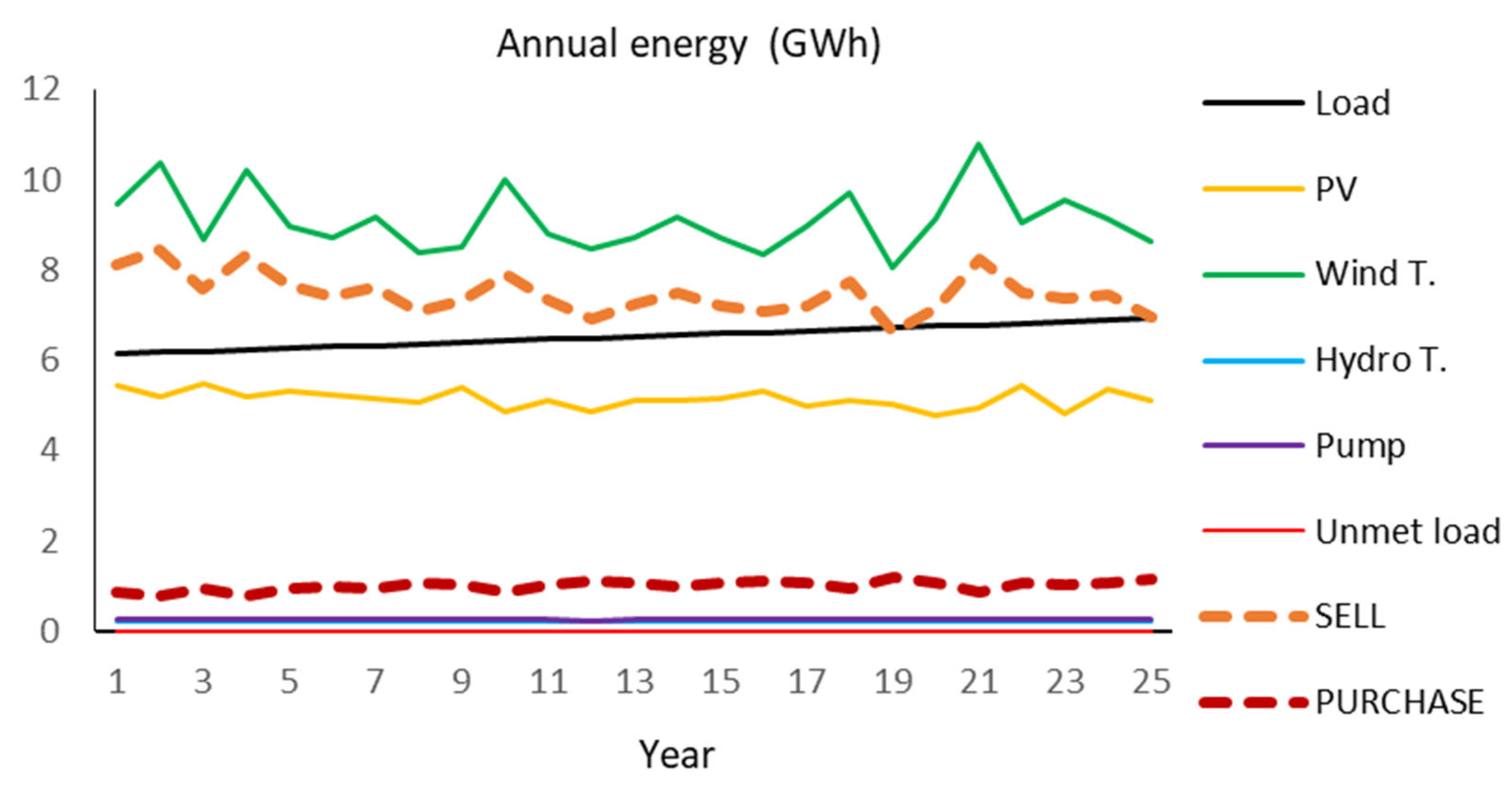

Figure 5.

Annual energy (GWh/year) supplied by the different components, unmet load, and sell energy during the 25 years of the simulation.

Figure 5.

Annual energy (GWh/year) supplied by the different components, unmet load, and sell energy during the 25 years of the simulation.

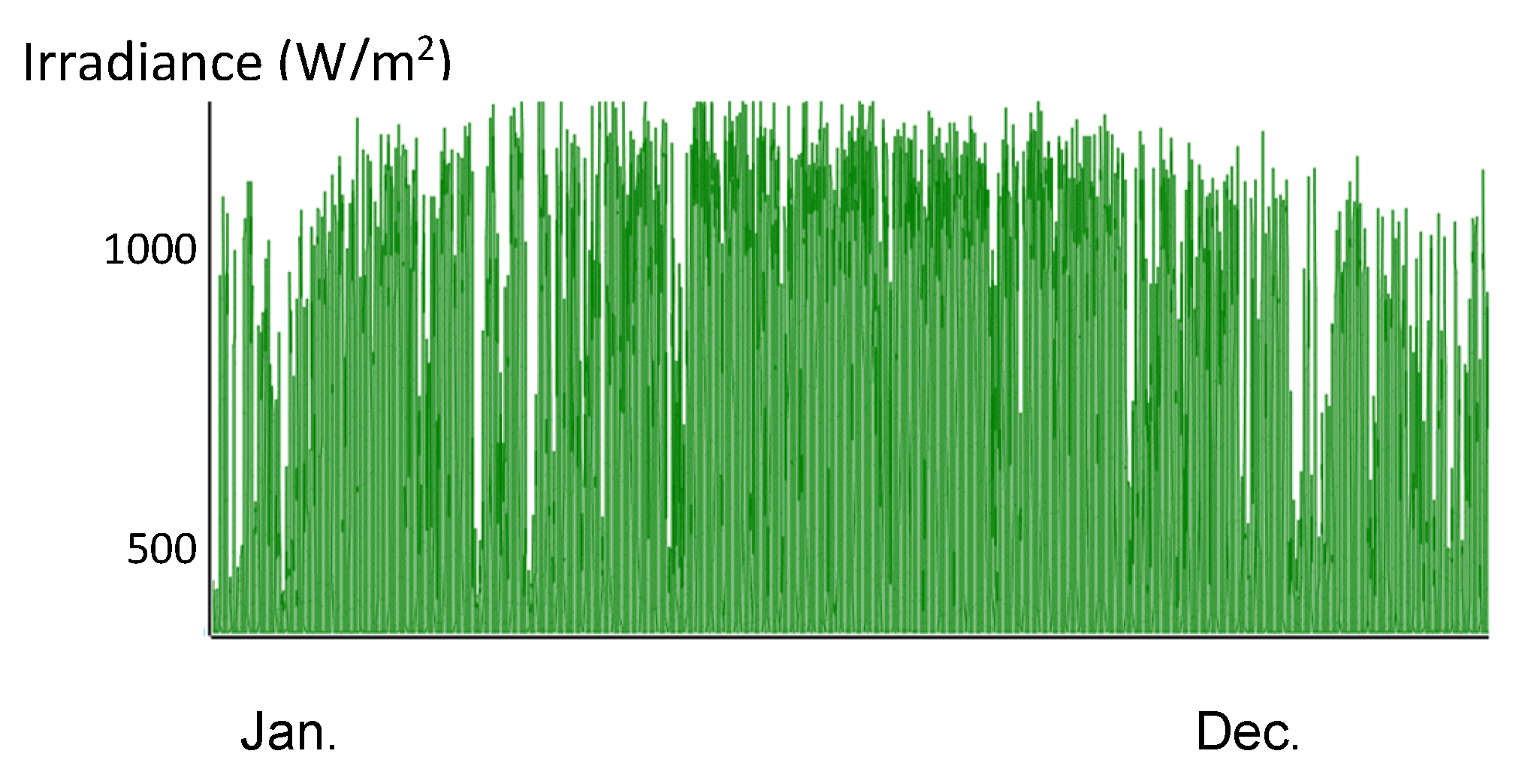

Figure 6.

Hourly irradiance (W/m2) in Zaragoza (slope of 35° and azimuth of 0°).

Figure 6.

Hourly irradiance (W/m2) in Zaragoza (slope of 35° and azimuth of 0°).

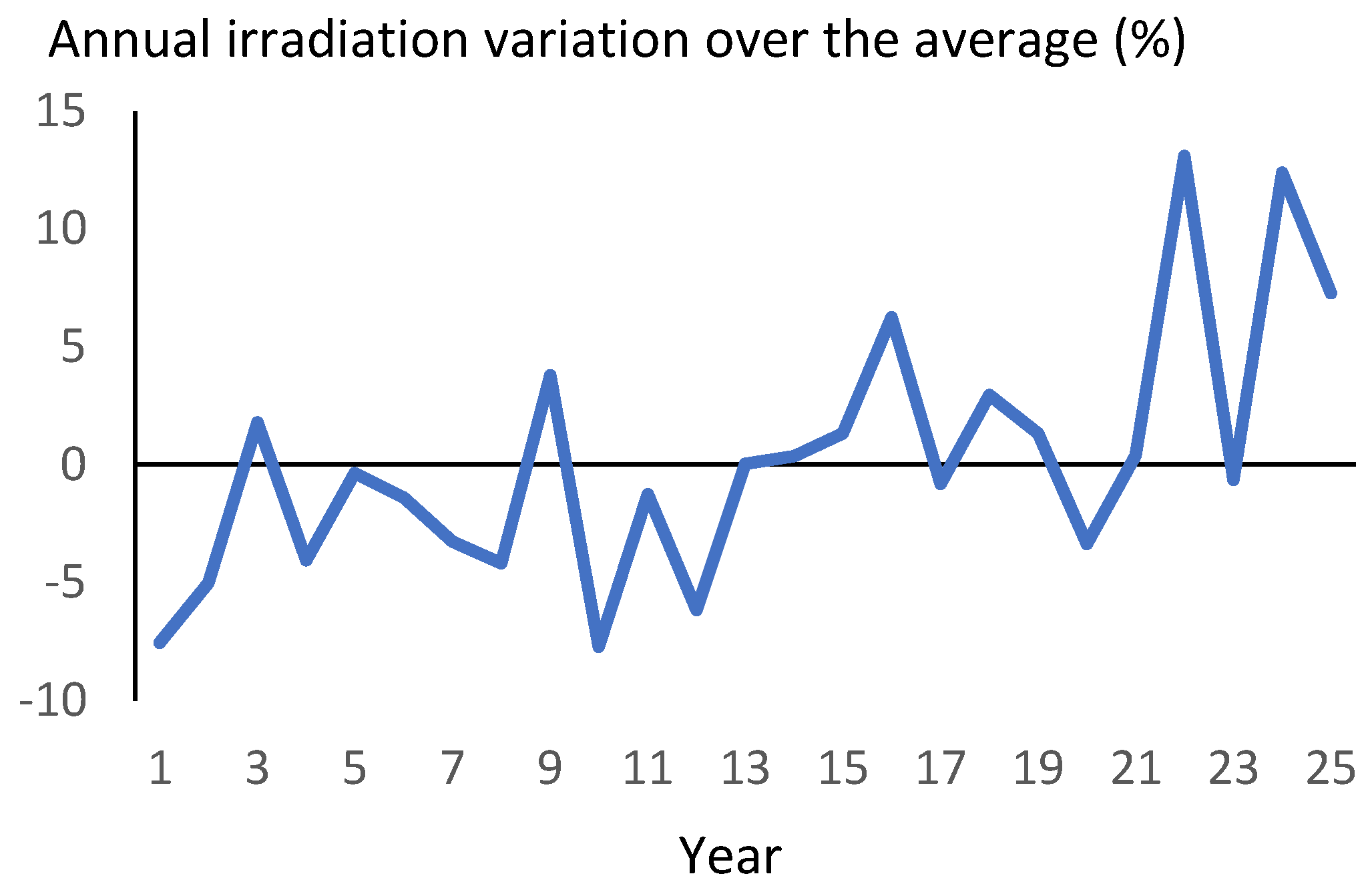

Figure 7.

Annual irradiation variation over the average (%).

Figure 7.

Annual irradiation variation over the average (%).

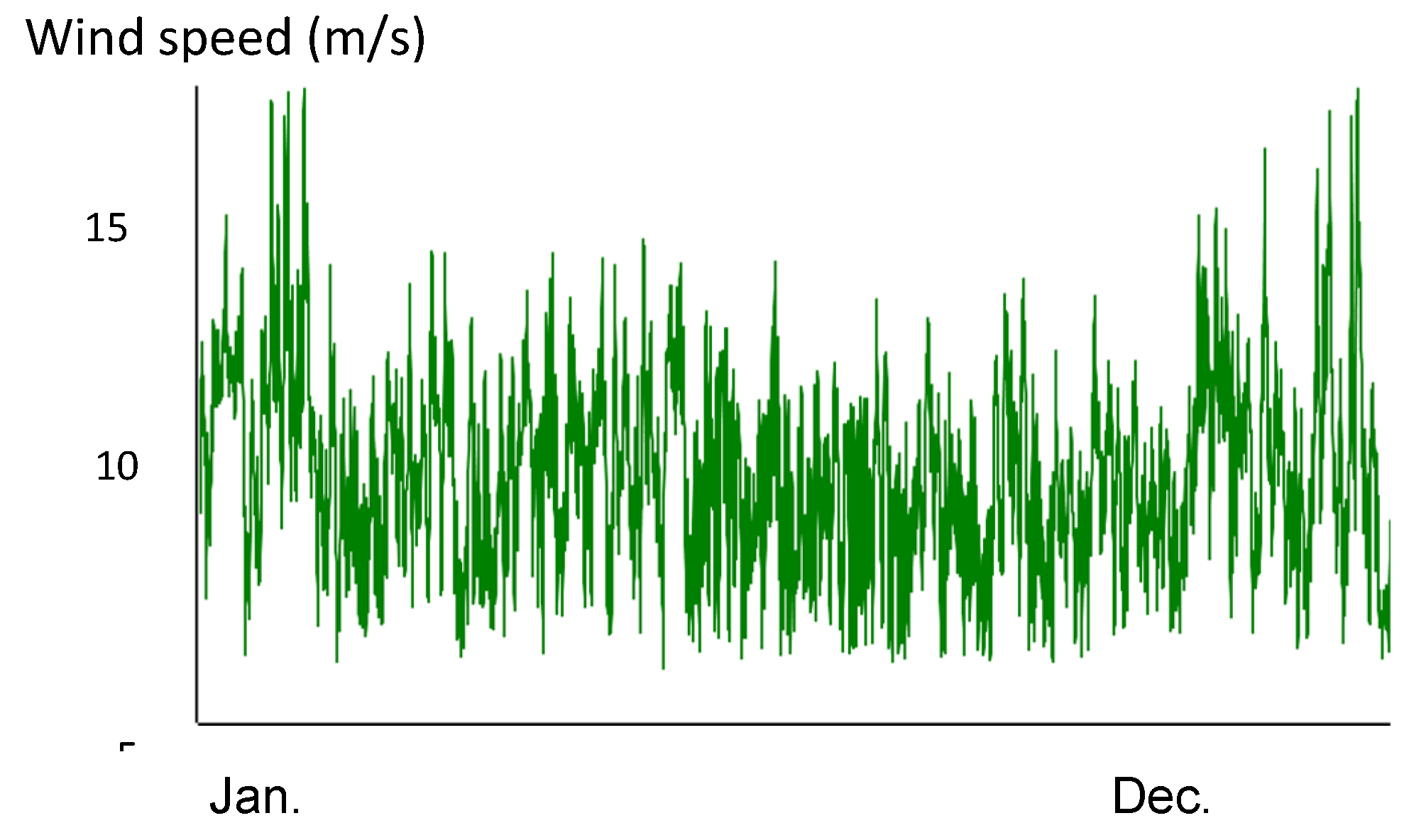

Figure 8.

Hourly wind speed (m/s) at a height of 53 m in Zaragoza.

Figure 8.

Hourly wind speed (m/s) at a height of 53 m in Zaragoza.

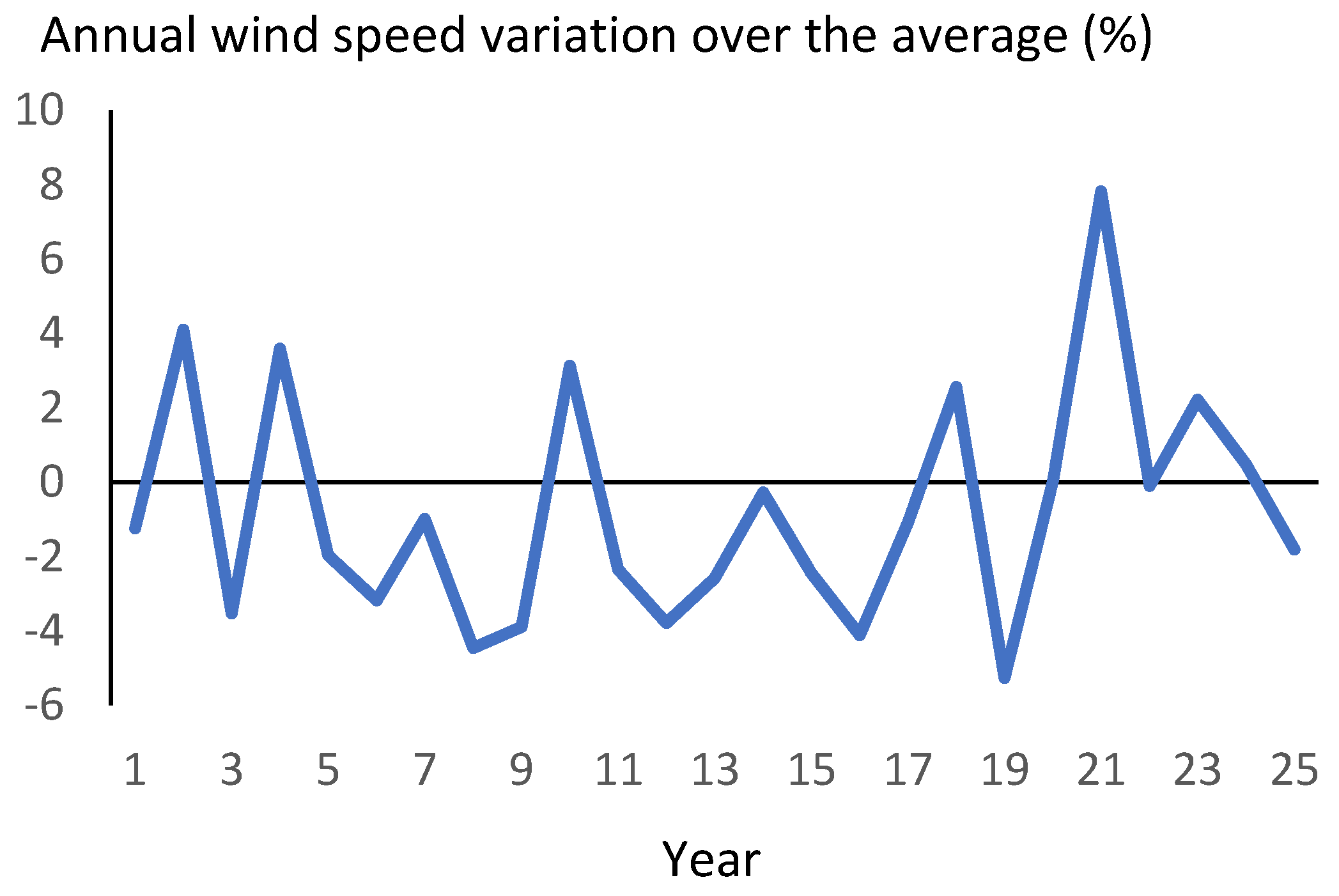

Figure 9.

Annual wind speed variation over the average (%).

Figure 9.

Annual wind speed variation over the average (%).

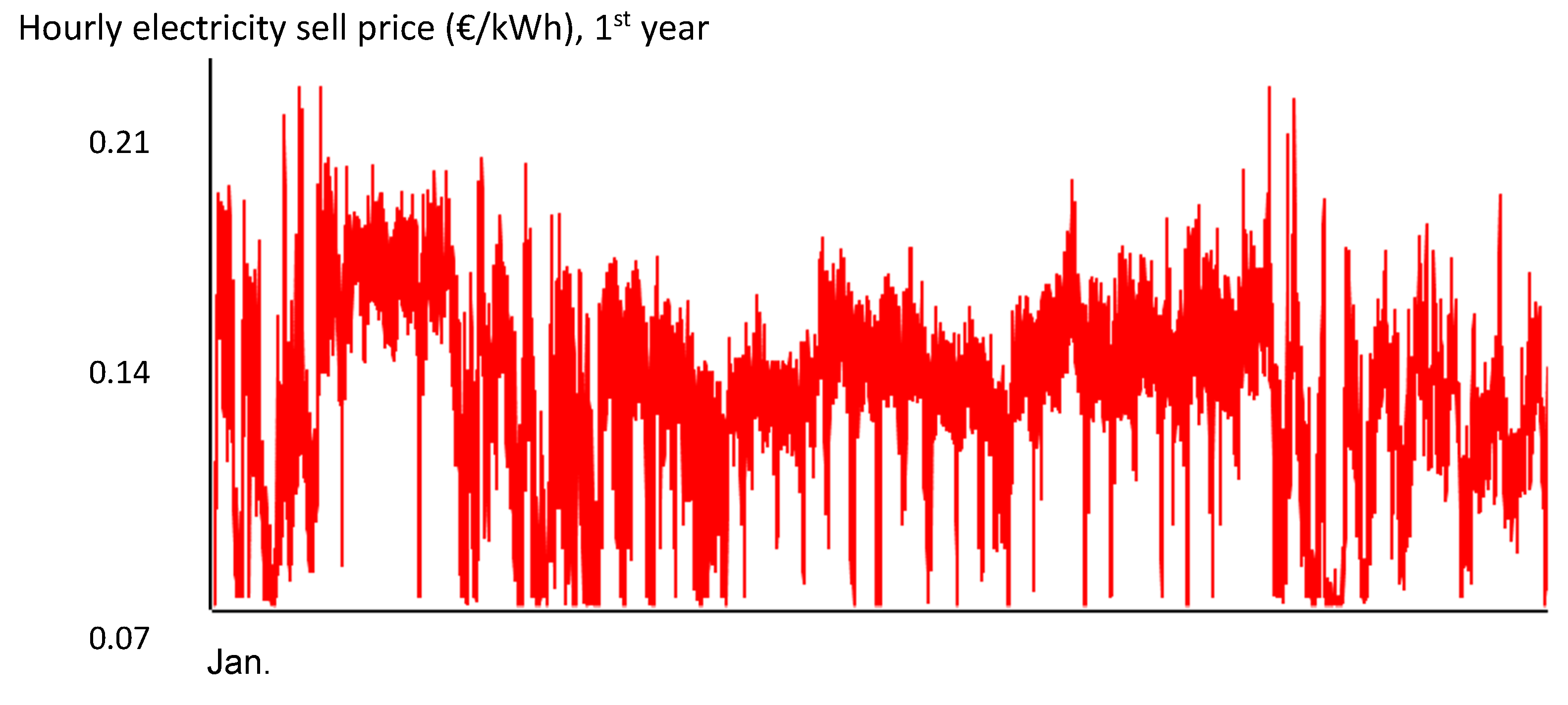

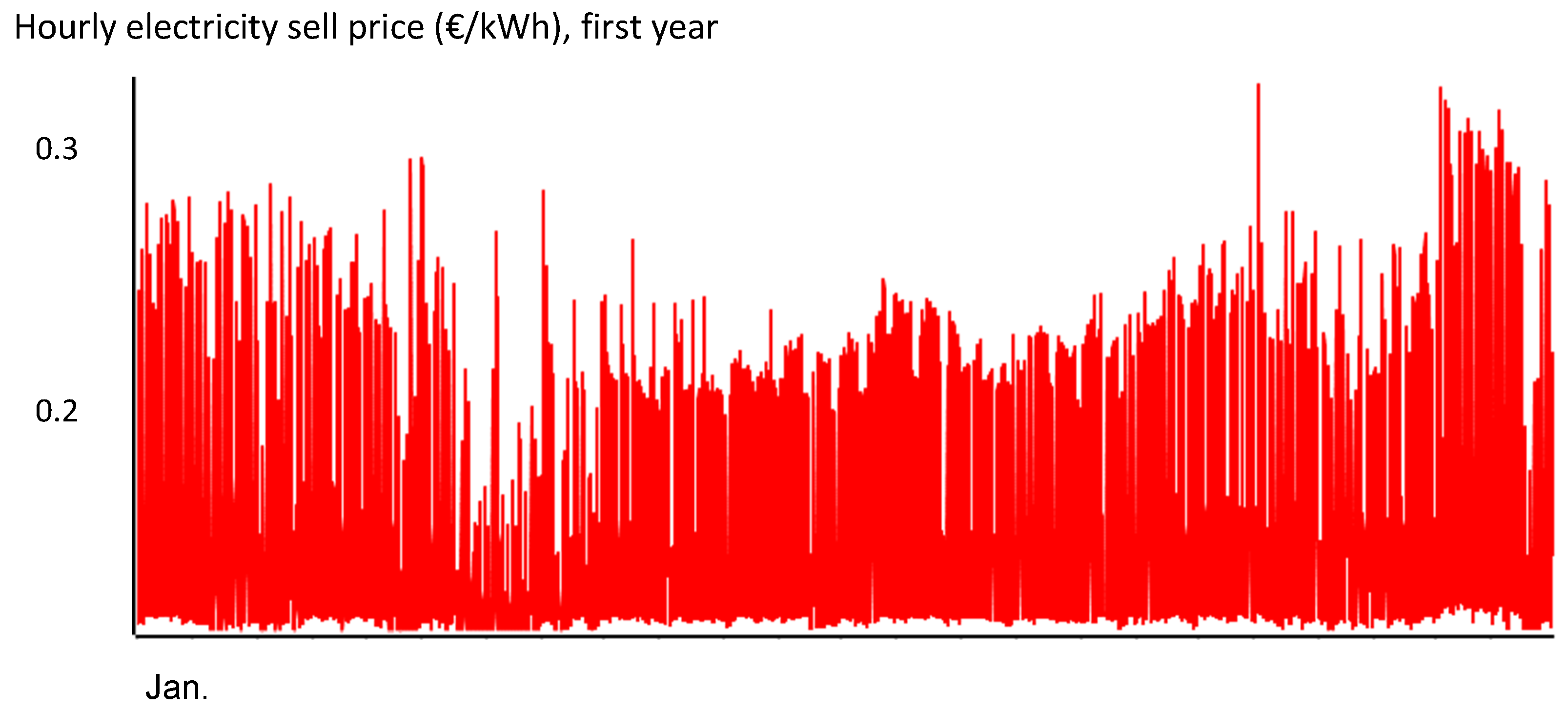

Figure 10.

Hourly sell electricity price for the first year.

Figure 10.

Hourly sell electricity price for the first year.

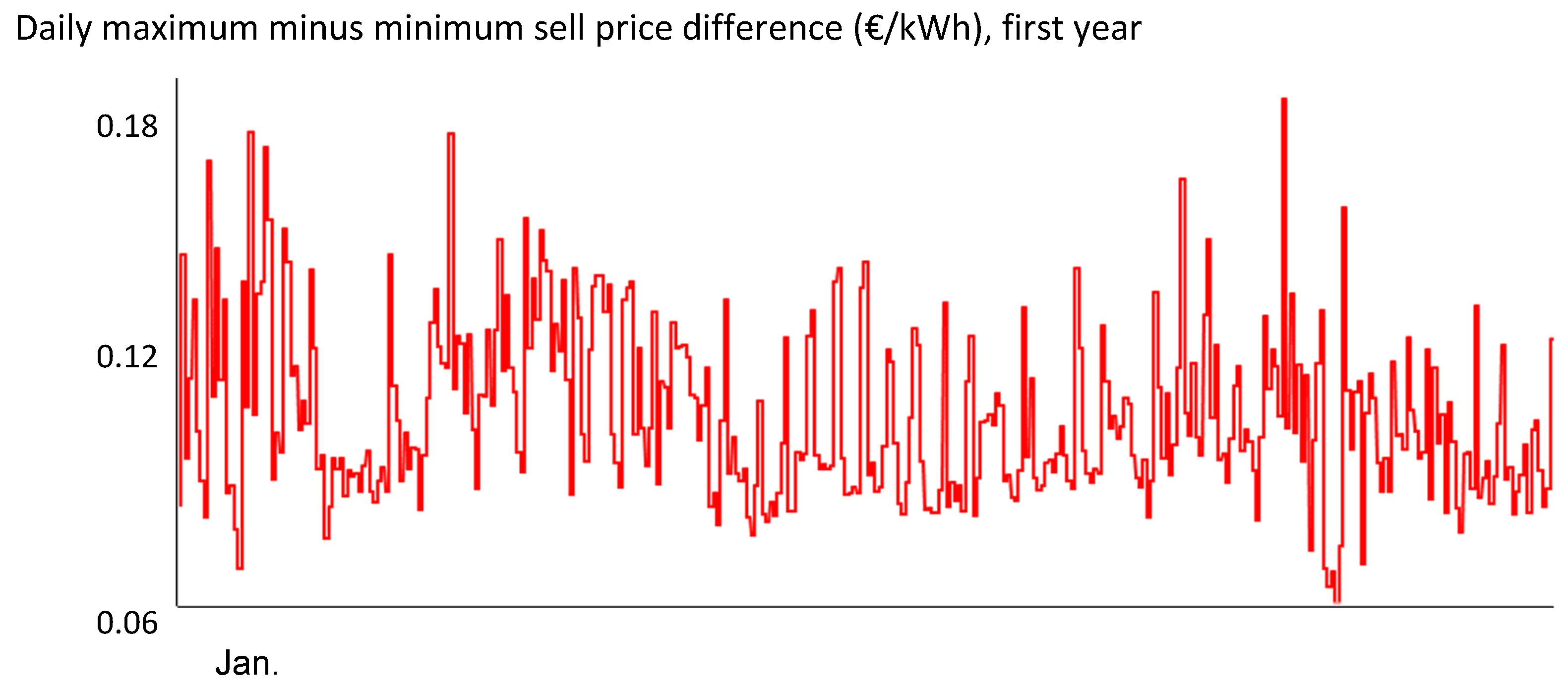

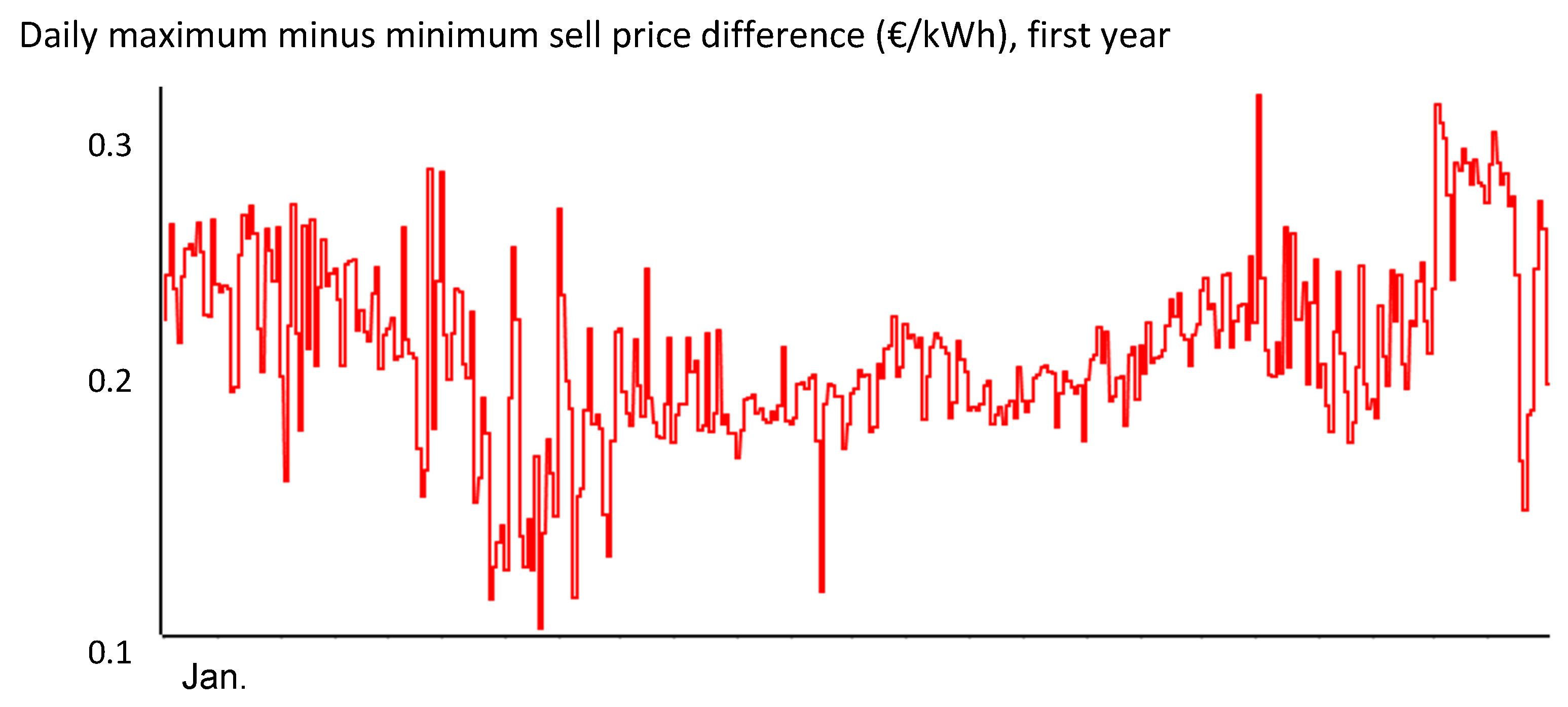

Figure 11.

Daily maximum minus minimum sell price difference (€/kWh) for the first year.

Figure 11.

Daily maximum minus minimum sell price difference (€/kWh) for the first year.

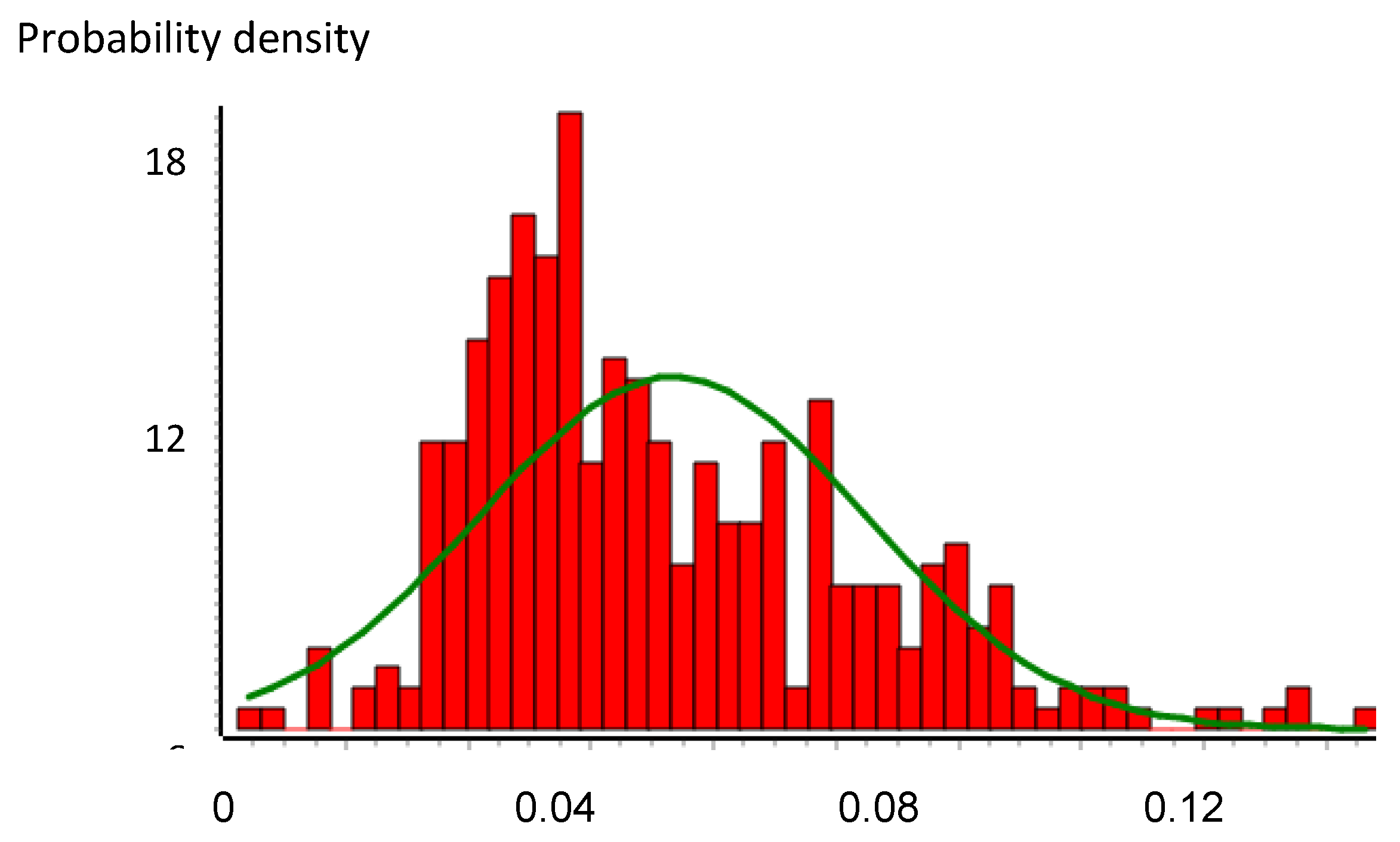

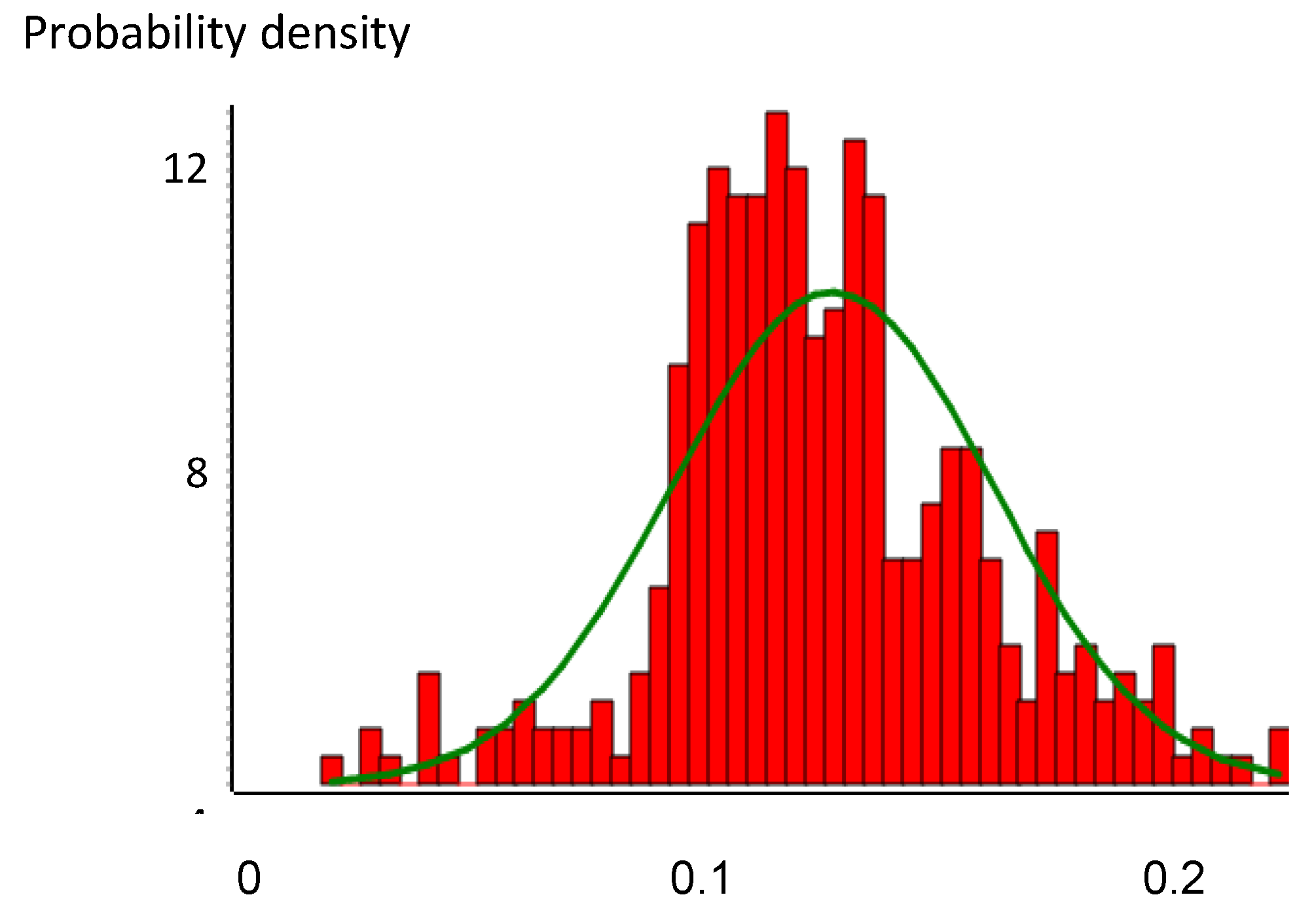

Figure 12.

Probability density function of the daily maximum minus minimum sell price difference (€/kWh) for the first year.

Figure 12.

Probability density function of the daily maximum minus minimum sell price difference (€/kWh) for the first year.

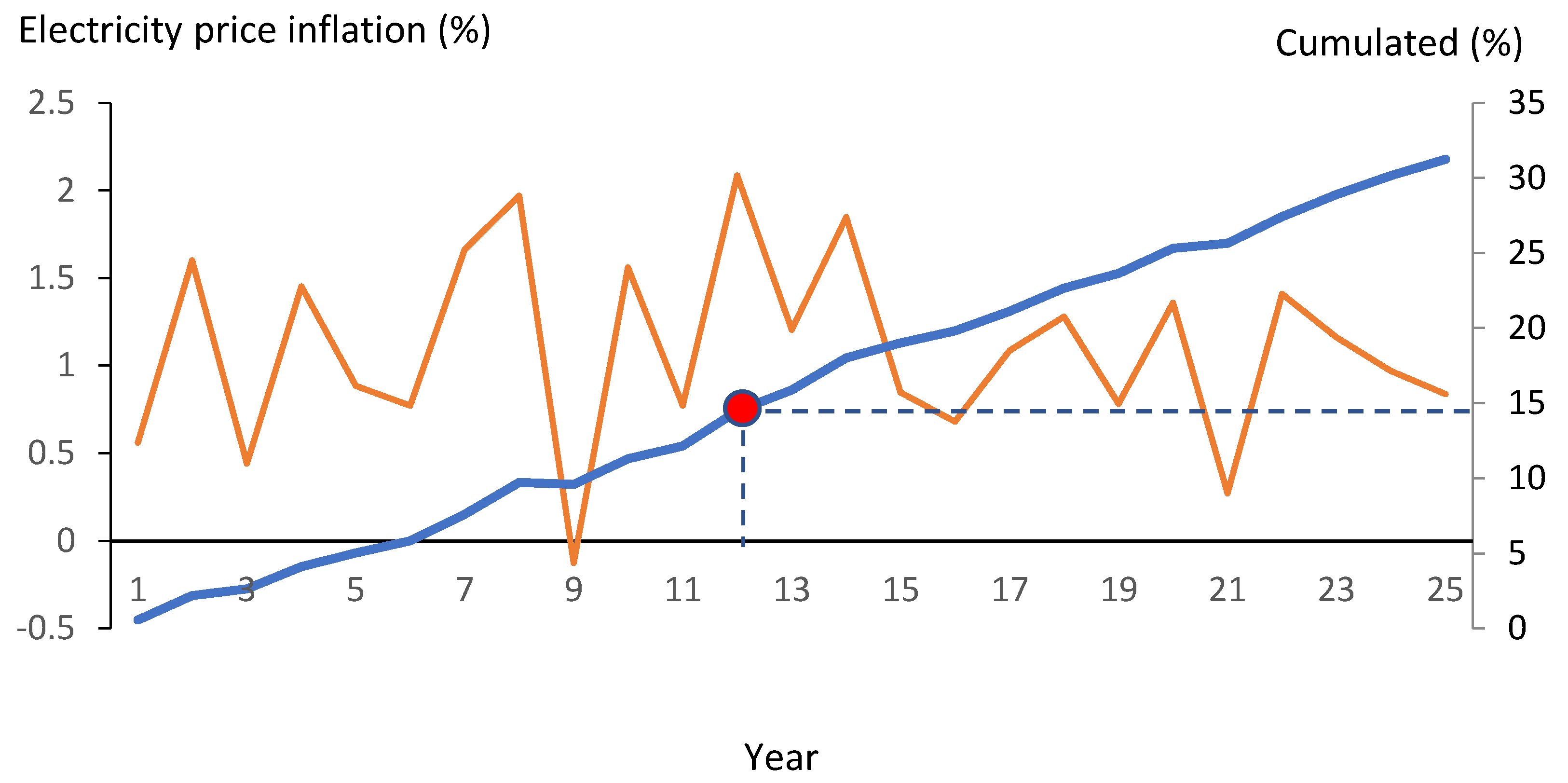

Figure 13.

Annual and cumulated inflation for the electricity price (%).

Figure 13.

Annual and cumulated inflation for the electricity price (%).

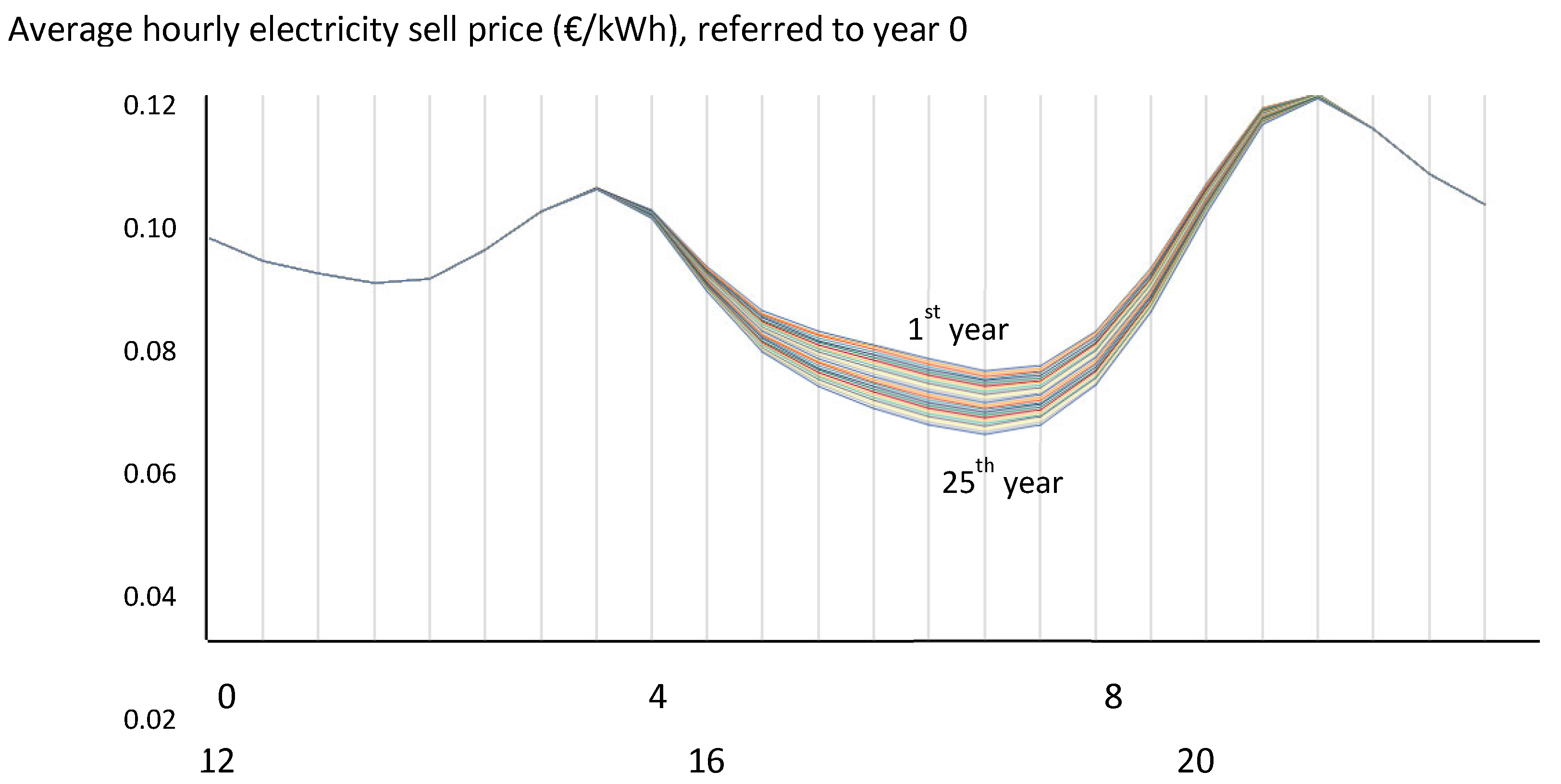

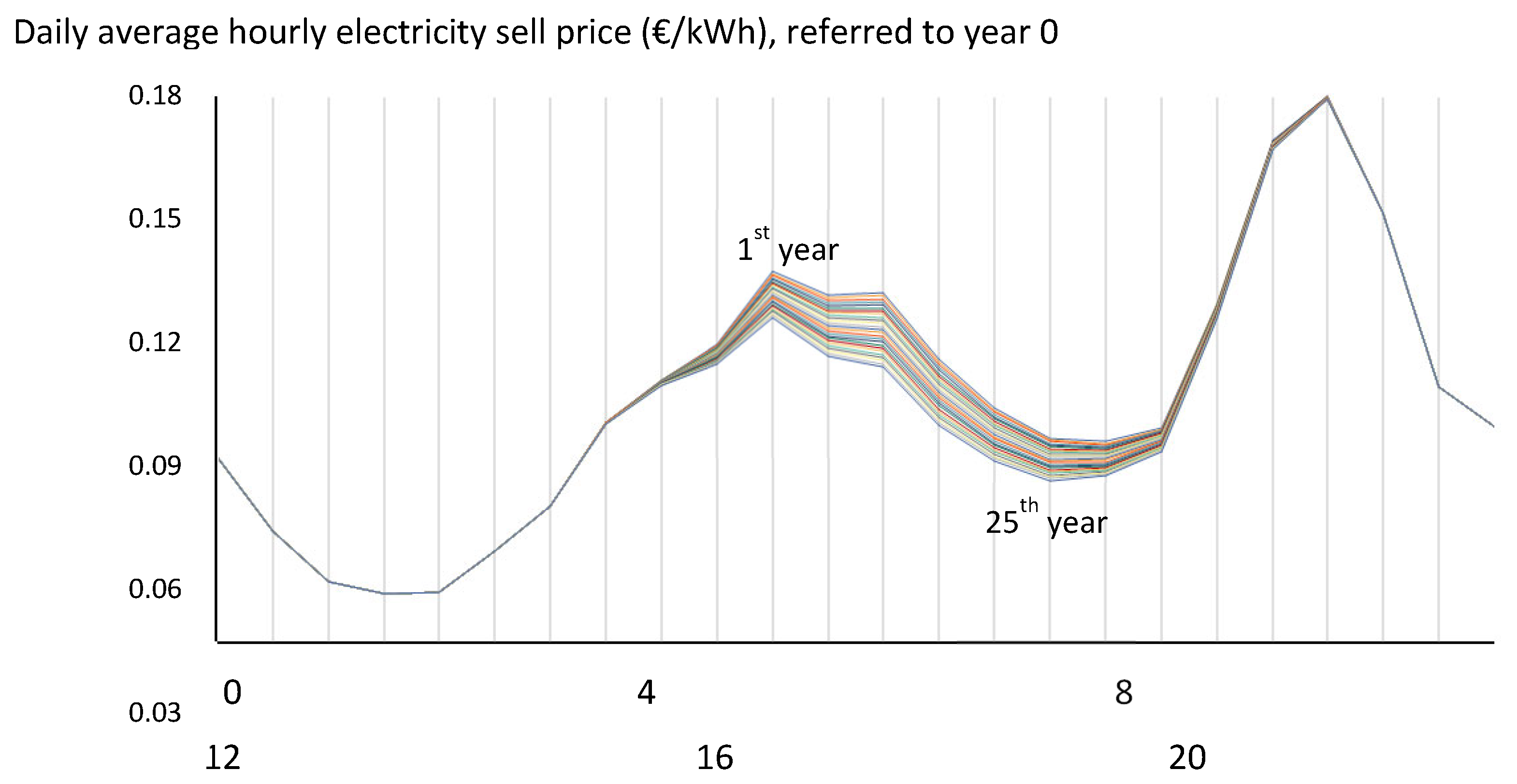

Figure 14.

Daily average hourly electricity sell price for the different years, all referred to the beginning of the system (year 0) (€/kWh).

Figure 14.

Daily average hourly electricity sell price for the different years, all referred to the beginning of the system (year 0) (€/kWh).

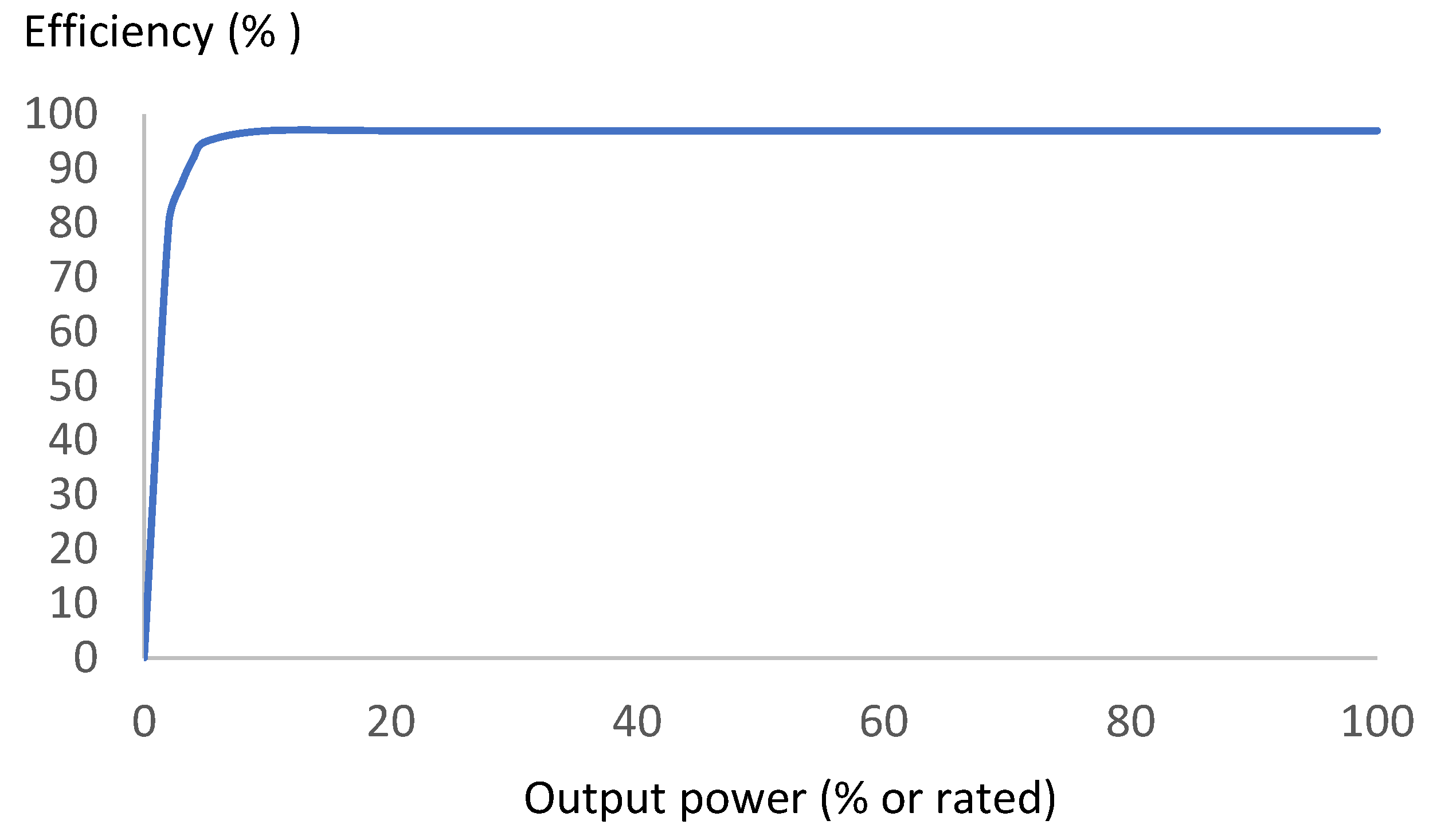

Figure 15.

PV Inverter efficiency.

Figure 15.

PV Inverter efficiency.

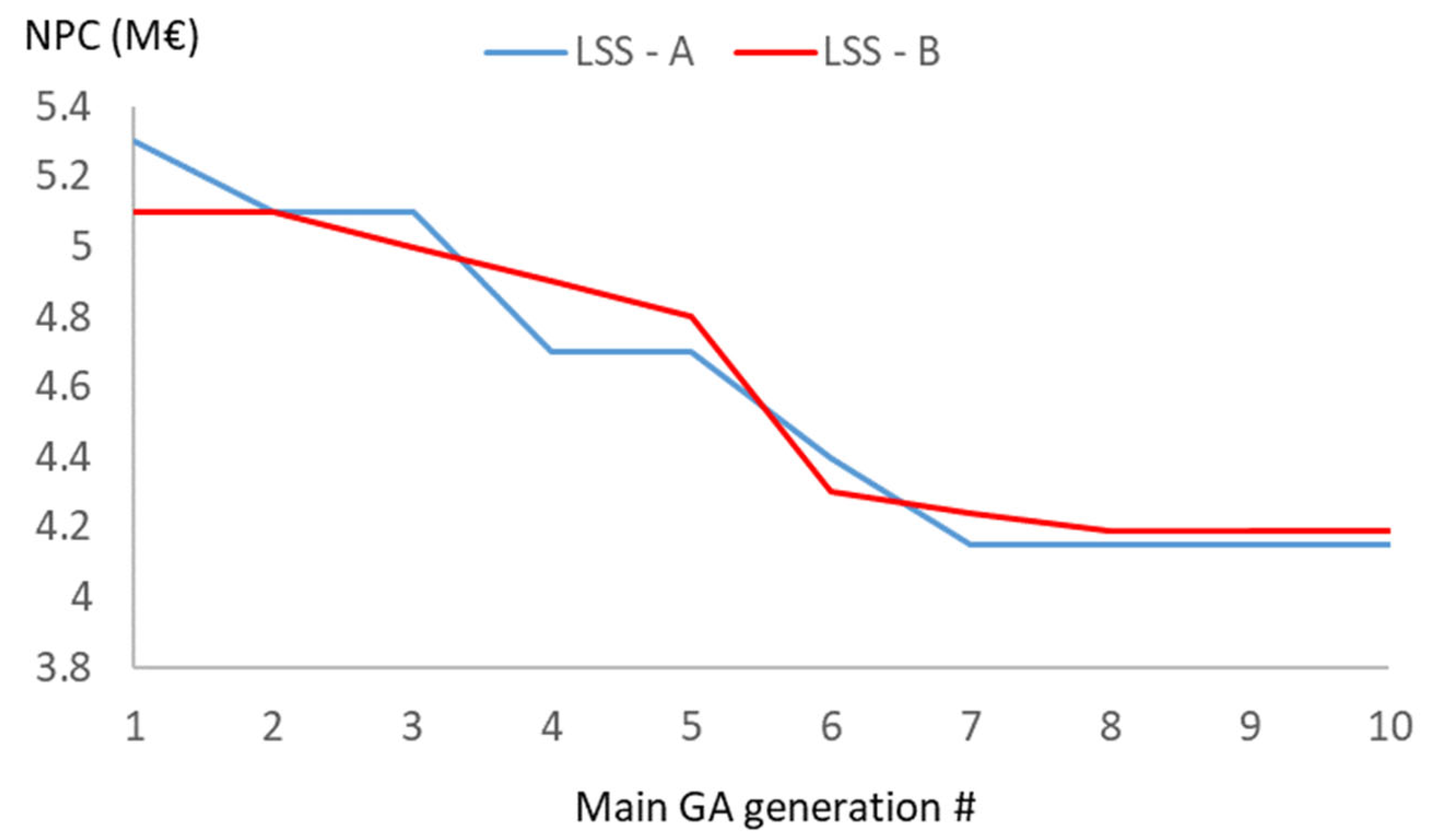

Figure 16.

Evolution of the NPC of the best system found for each generation of the GA.

Figure 16.

Evolution of the NPC of the best system found for each generation of the GA.

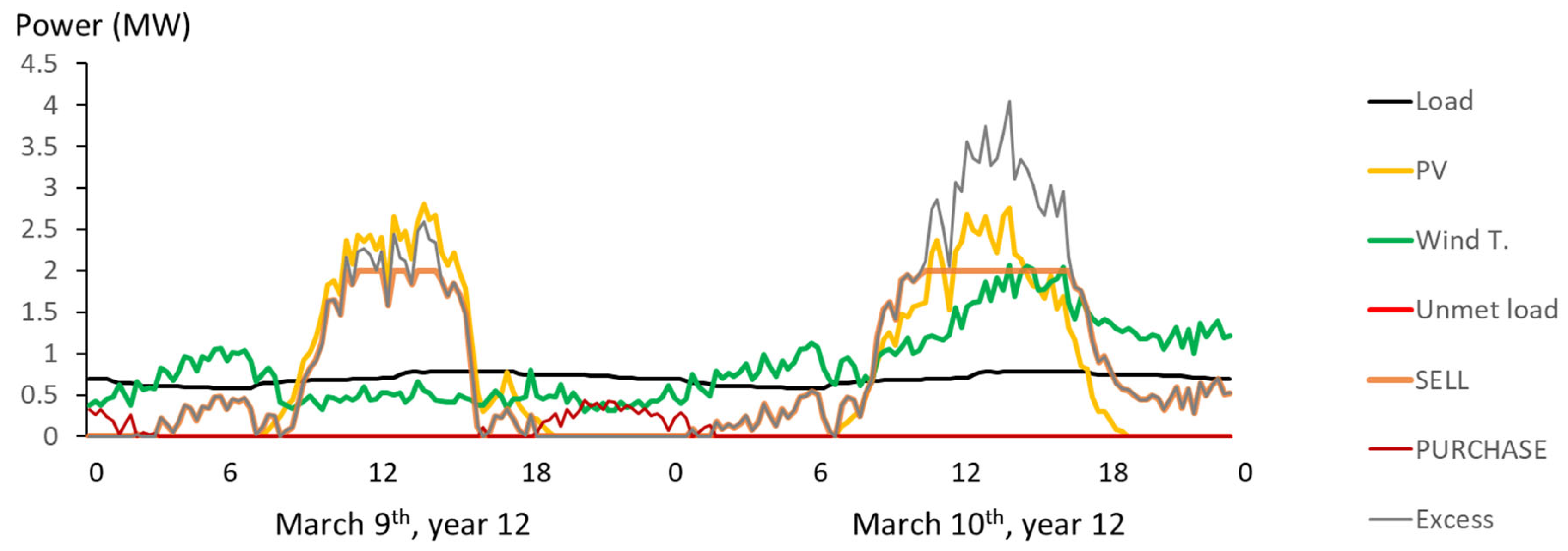

Figure 17.

Simulation of two consecutive days, March 9 and 10, year 12. LSS optimal system without PHS.

Figure 17.

Simulation of two consecutive days, March 9 and 10, year 12. LSS optimal system without PHS.

Figure 18.

Annual energy, LSS optimal system without PHS.

Figure 18.

Annual energy, LSS optimal system without PHS.

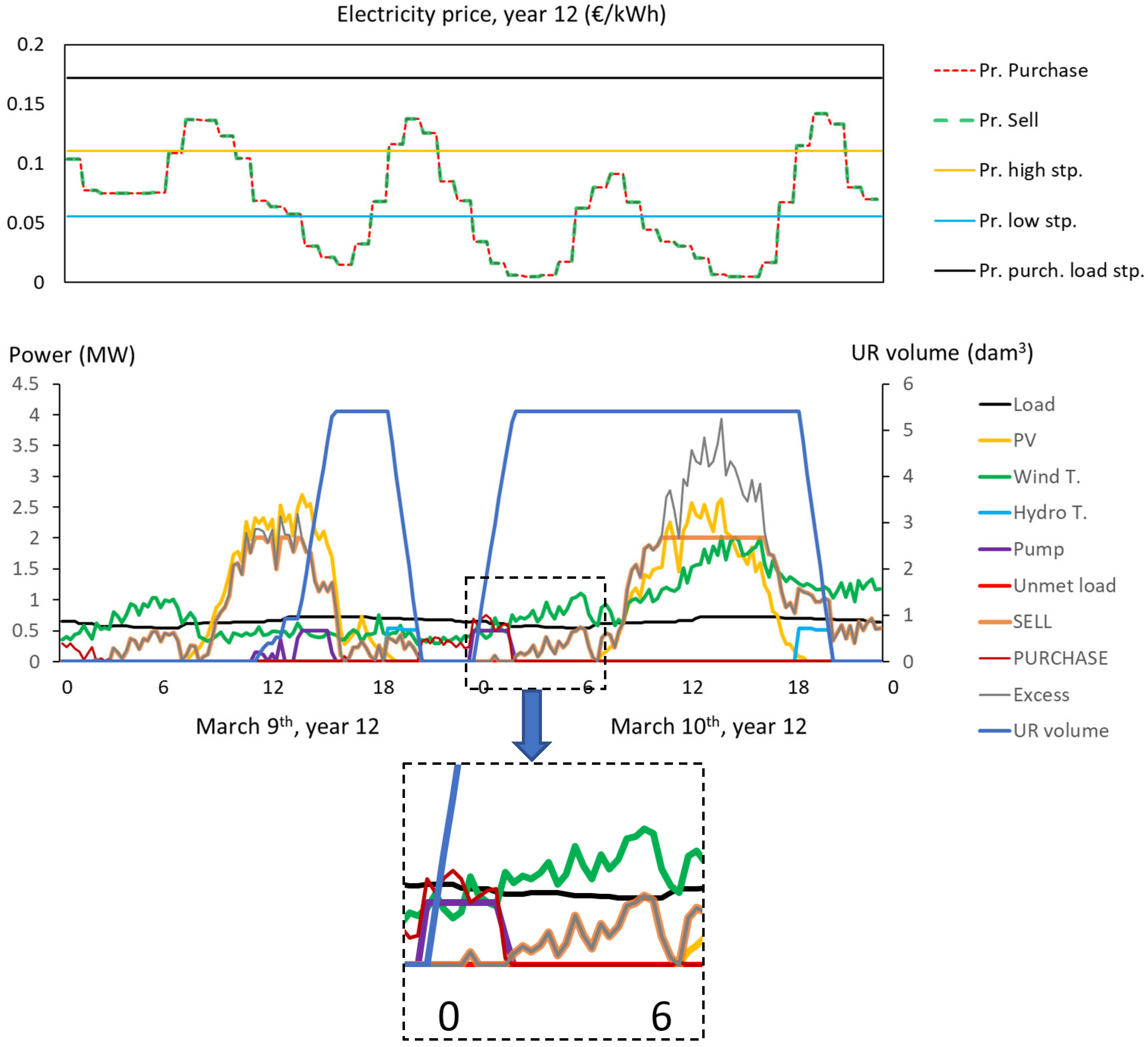

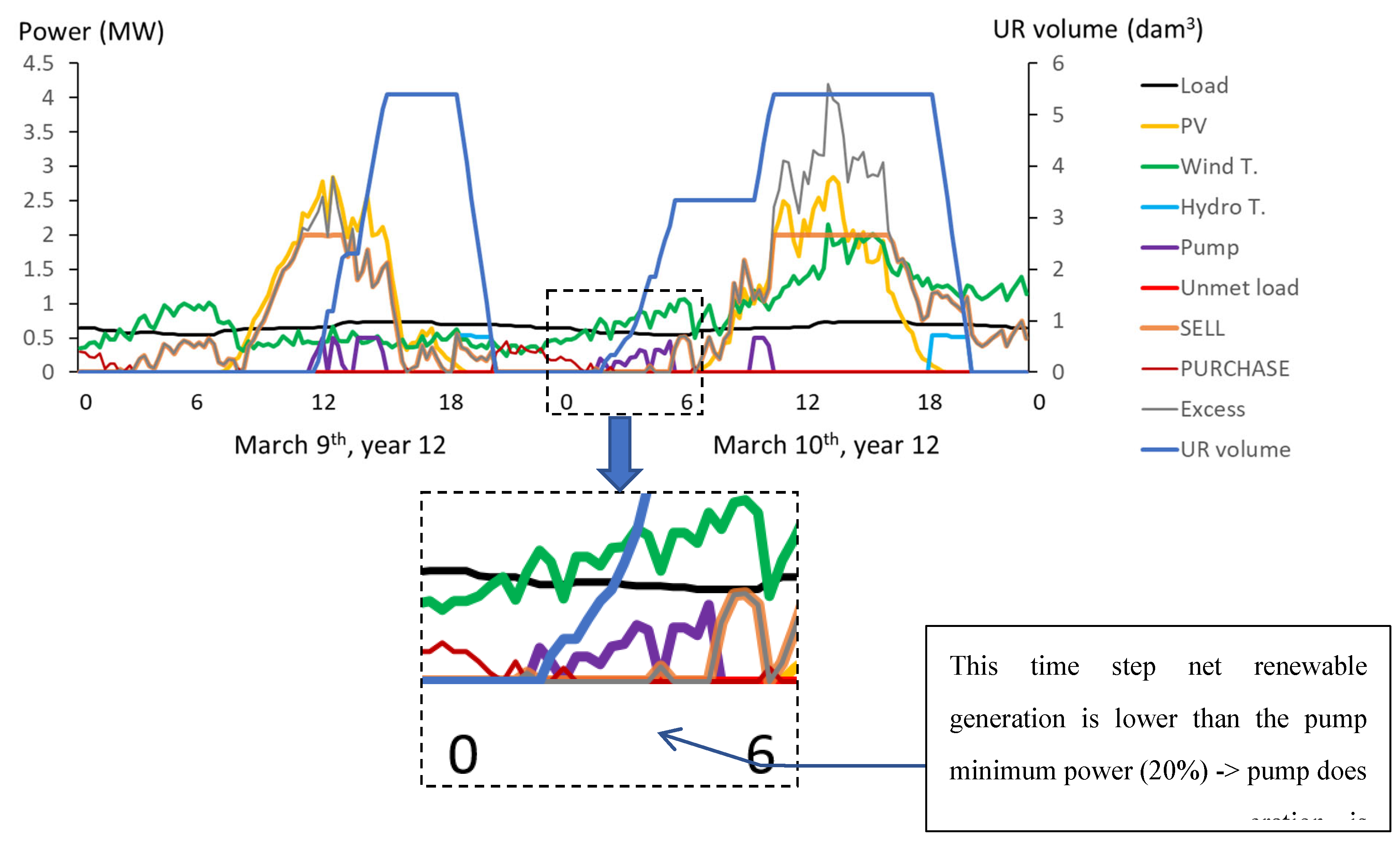

Figure 19.

Simulation of two consecutive days, March 9–10, year 12. LSS optimal system with PHS, type A project.

Figure 19.

Simulation of two consecutive days, March 9–10, year 12. LSS optimal system with PHS, type A project.

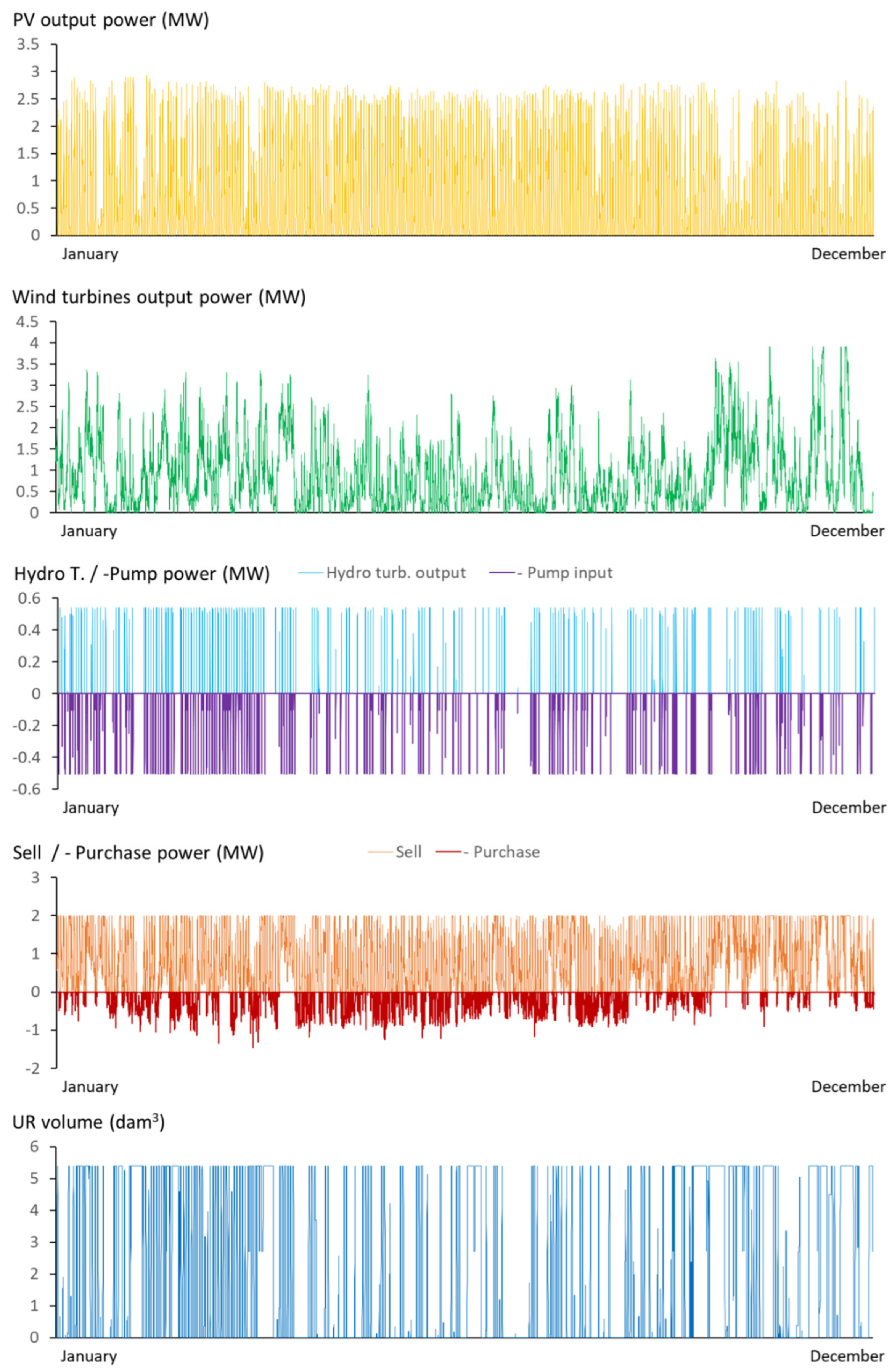

Figure 20.

Simulation of year 12. LSS optimal system with PHS, type A project.

Figure 20.

Simulation of year 12. LSS optimal system with PHS, type A project.

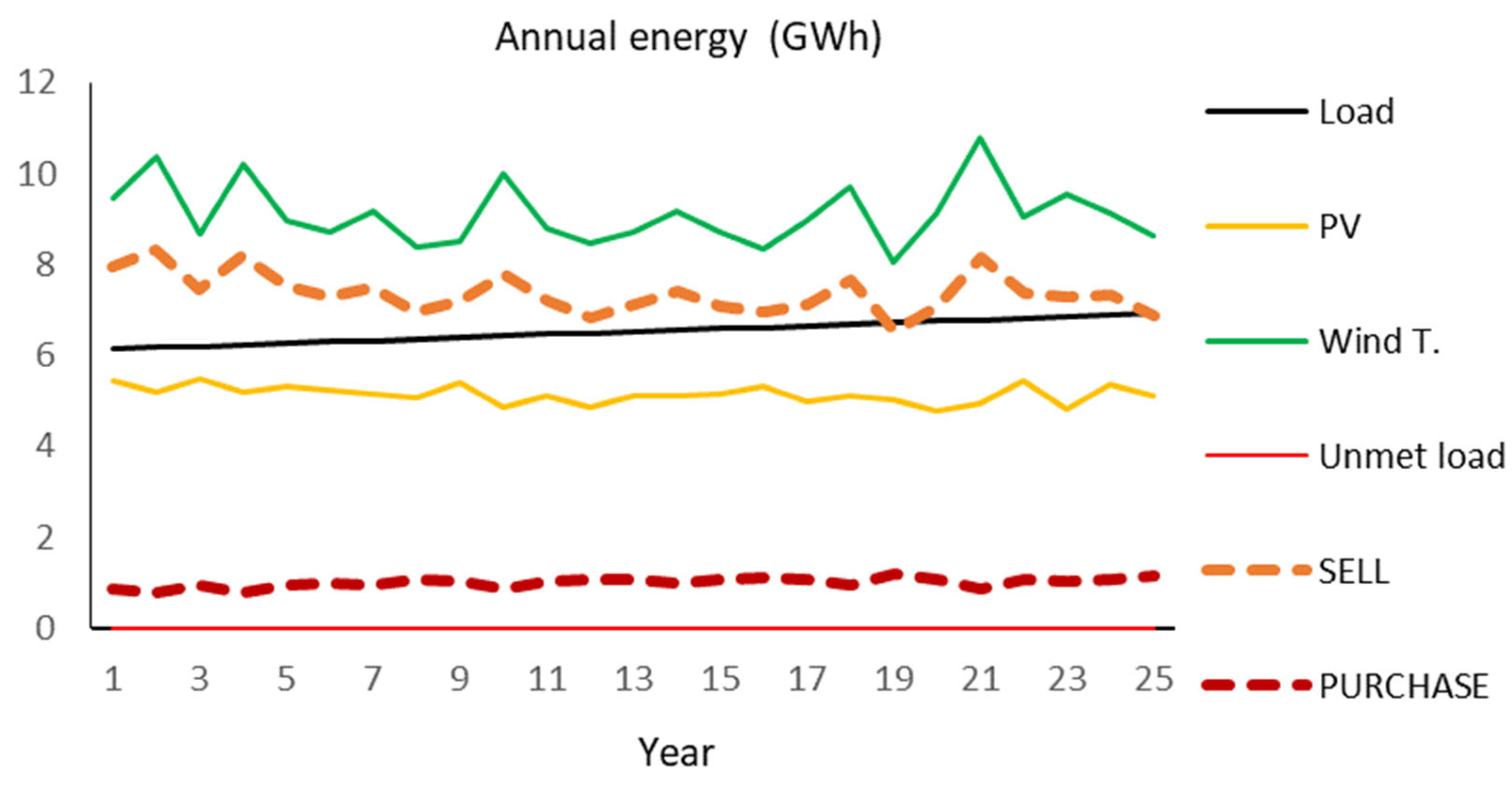

Figure 21.

Annual energy, LSS optimal system with PHS, type A project.

Figure 21.

Annual energy, LSS optimal system with PHS, type A project.

Figure 22.

Simulation of two consecutive days, March 9–10, year 12. LSS Optimal system with PHS, type B project.

Figure 22.

Simulation of two consecutive days, March 9–10, year 12. LSS Optimal system with PHS, type B project.

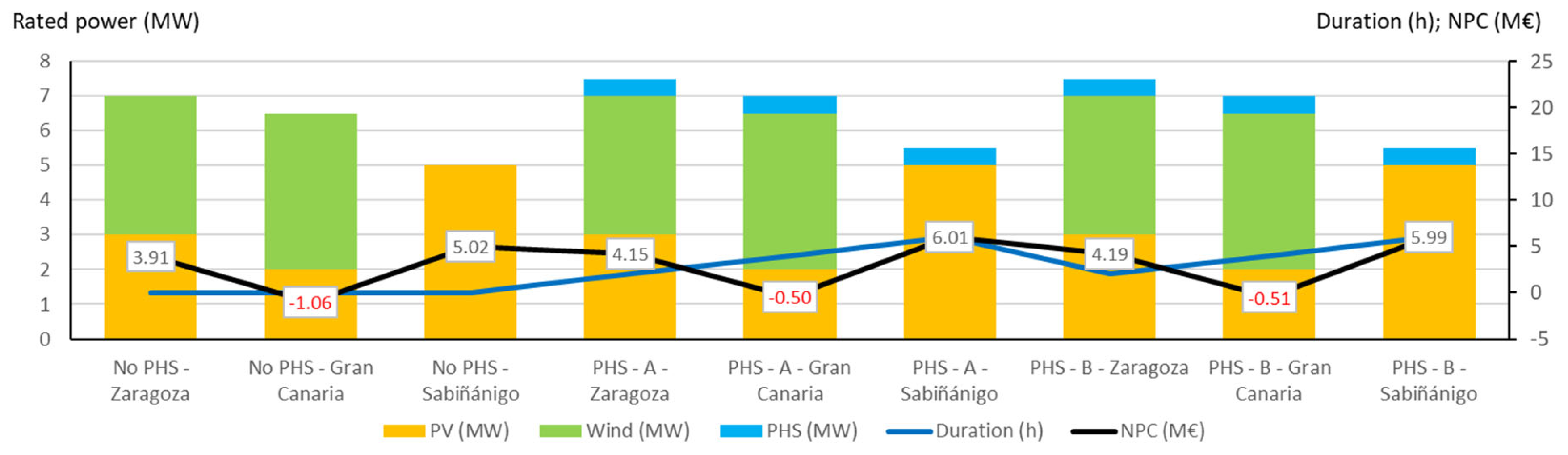

Figure 23.

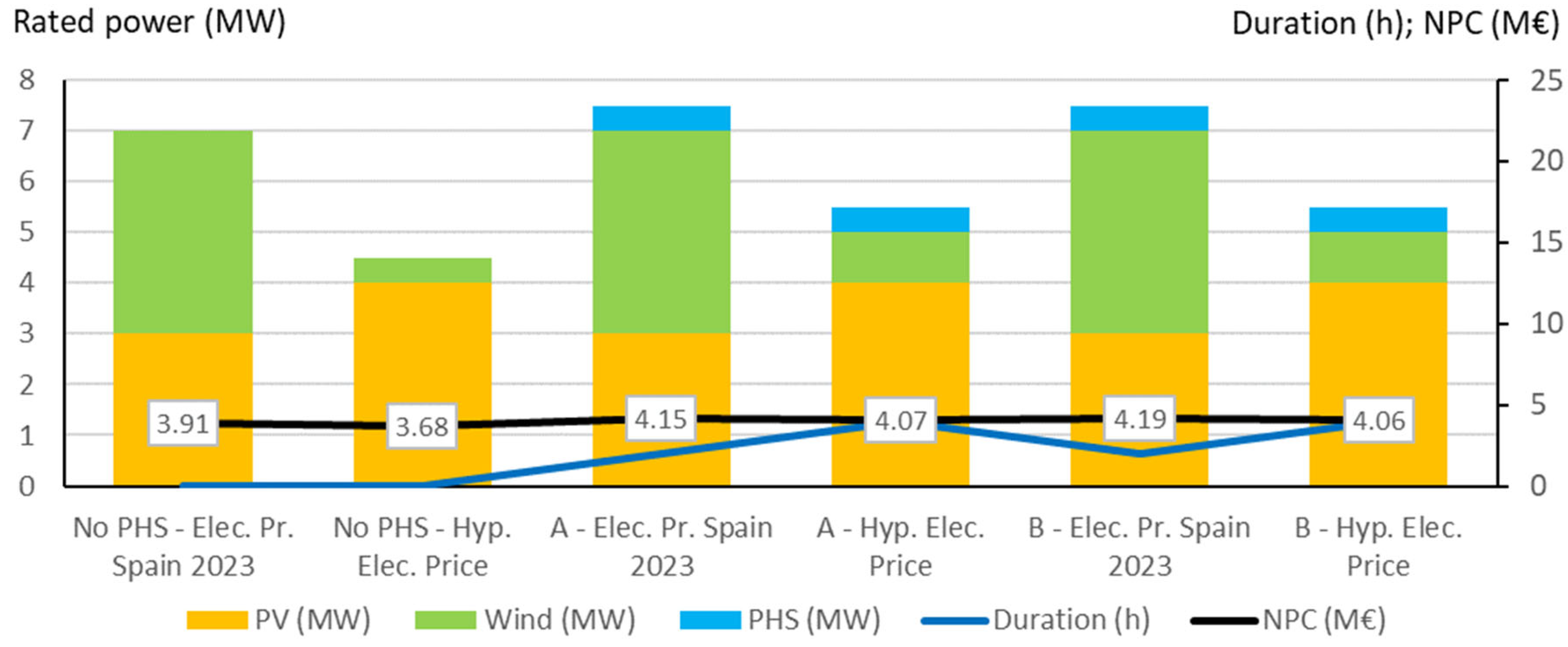

Optimal systems found for the different locations: LSS systems.

Figure 23.

Optimal systems found for the different locations: LSS systems.

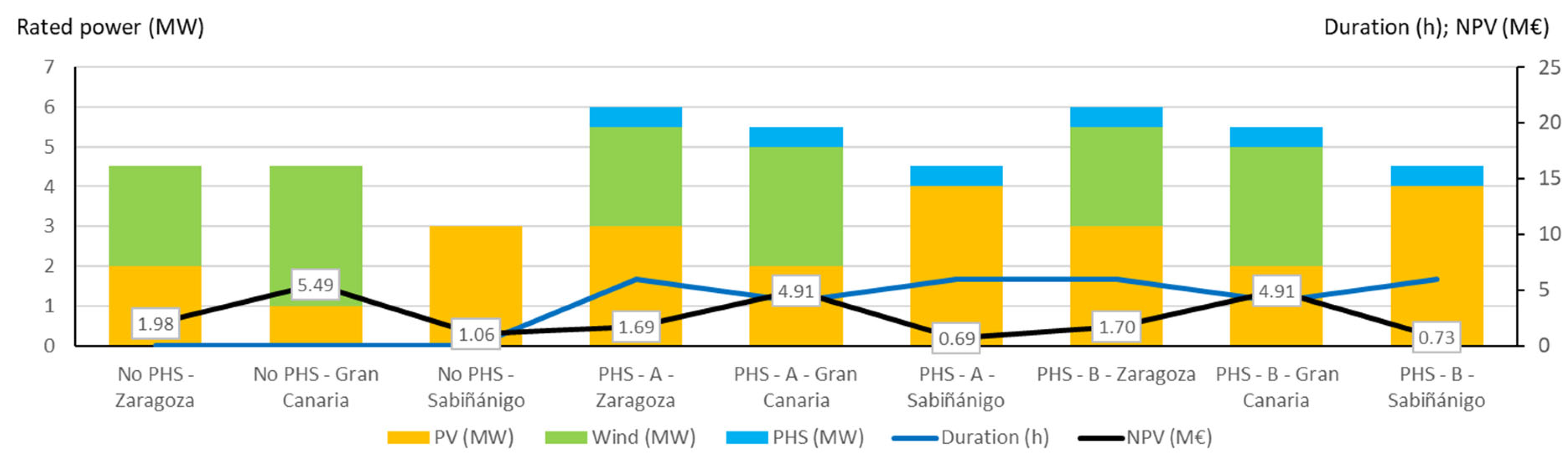

Figure 24.

Optimal systems found for the different locations: PGS systems.

Figure 24.

Optimal systems found for the different locations: PGS systems.

Figure 25.

Hourly sell electricity price of first year. Hypothetical electricity price.

Figure 25.

Hourly sell electricity price of first year. Hypothetical electricity price.

Figure 26.

Daily maximum minus minimum sell price difference (€/kWh), first year. Hypothetical electricity price.

Figure 26.

Daily maximum minus minimum sell price difference (€/kWh), first year. Hypothetical electricity price.

Figure 27.

Probability density of the daily maximum minus minimum sell price difference (€/kWh), first year. Hypothetical electricity price.

Figure 27.

Probability density of the daily maximum minus minimum sell price difference (€/kWh), first year. Hypothetical electricity price.

Figure 28.

Daily average hourly electricity price, referred to year 0. Hypothetical electricity price.

Figure 28.

Daily average hourly electricity price, referred to year 0. Hypothetical electricity price.

Figure 29.

Optimal systems found for the different RTP electrical price: LSS system.

Figure 29.

Optimal systems found for the different RTP electrical price: LSS system.

Figure 30.

Optimal systems found for the different RTP electrical price: PGS system.

Figure 30.

Optimal systems found for the different RTP electrical price: PGS system.

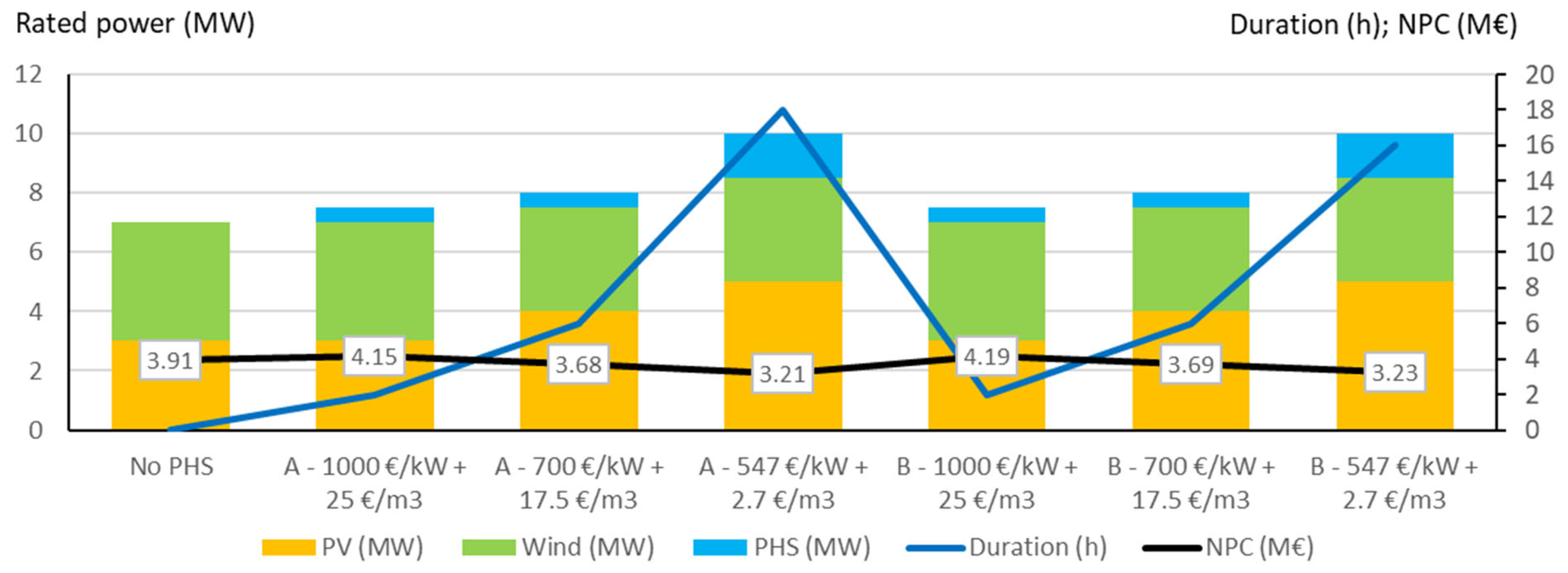

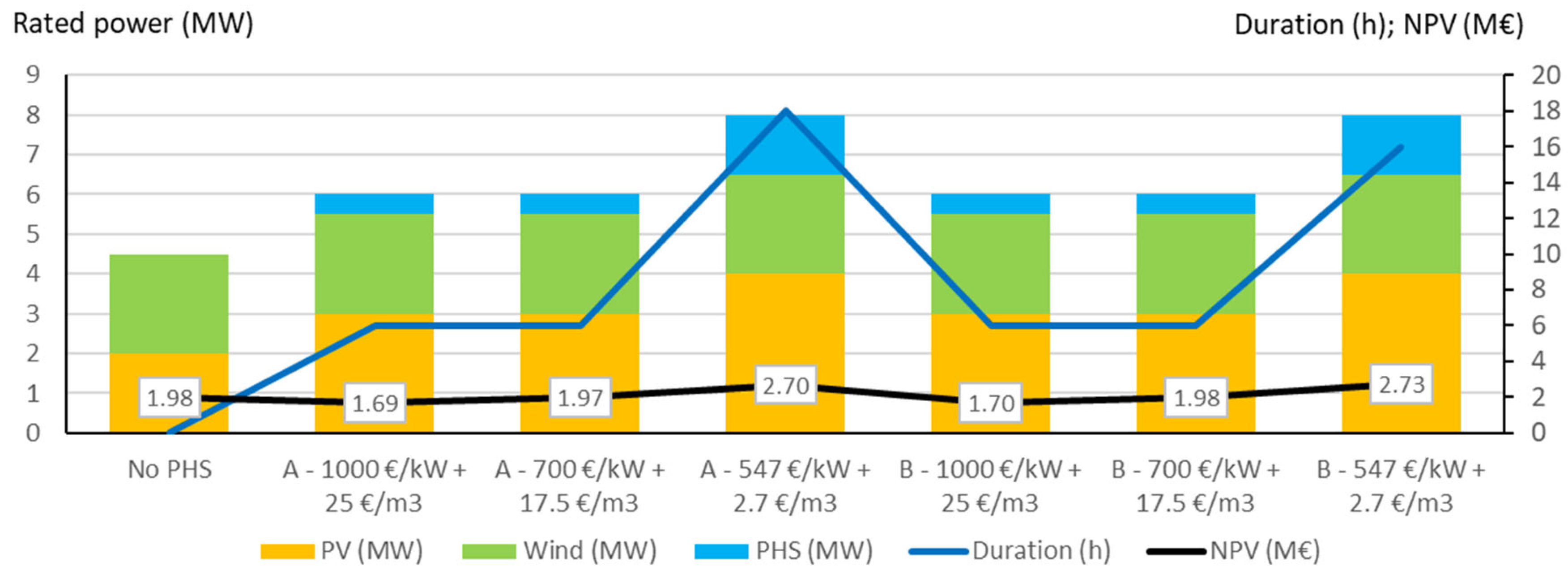

Figure 31.

Optimal systems found for the different PHS CAPEX: LSS system.

Figure 31.

Optimal systems found for the different PHS CAPEX: LSS system.

Figure 32.

Optimal systems found for the different PHS CAPEX: PGS system.

Figure 32.

Optimal systems found for the different PHS CAPEX: PGS system.

Table 1.

Performance of the two different types of projects (A or B) of PV-wind-PHS systems.

Table 1.

Performance of the two different types of projects (A or B) of PV-wind-PHS systems.

| |

Type A: Allowed to buy energy for arbitrage |

Type B: Not allowed to buy energy for arbitrage |

| Allowed to purchase electricity from the grid for arbitrage (for pumping) |

✓ |

✗ |

| Arbitrage sell electricity price set points ) |

✕ |

✓ |

| Arbitrage purchase electricity price set points ()

|

✓ |

✕ |

|

Operation principle: During each time step t: |

|

|

| |

|

|

| - If there is net renewable generation () or no load and no generation. |

- If buy electricity price is higher than the set point () → Energy arbitrage (discharge): Priority is injecting (sell) electricity to the grid (net renewable generation + hydro t. max. power*):

- If → Energy arbitrage (charge): Priority pumping water with a renewable surplus power; if it is lower than pump rated power, buy electricity to run the pump at the rated power:

- If → No arbitrage: Priority is injecting the net renewable generation to the grid. |

-If buy electricity price is higher than the set point ( → Energy arbitrage (discharge): Priority is injecting (sell) electricity to the grid (net renewable generation + hydro turbine max. power*):

- If → Energy arbitrage (charge): Priority is pumping water with renewable surplus power:

- If → No arbitrage: Priority is injecting the net renewable generation to the grid:

|

| |

|

| - If there is net load () |

If > .

. Further, consider priorities for energy arbitrage (depending on the electricity price) shown above |

| |

|

|

Table 2.

Results of the optimal system obtained by Nassar et al. [

28] and comparison with this work.

Table 2.

Results of the optimal system obtained by Nassar et al. [

28] and comparison with this work.

| |

Total renewable generation (GWh/year) |

Energy injected to the grid (%) |

Direct supply to the load from renewable sources (%) |

Demand covered by hydro turbine (%) |

Unmet load (%) |

| Nassar et al.’s optimal system (lowest LCOE) [28] |

14.6 |

57.1 |

85 |

15 |

0 |

| This work, assuming the same inputs as Nassar et al. [28], simulating their optimal system (with several assumptions) |

14.72 |

57.6 |

84.6 |

15.4 |

0.4 |

| This work, same inputs as Nassar et al. [28] plus a variable head, pump-turbine variable efficiencies, and simulating 25 years. |

14.33 av.

13.92 min.

14.74 max.

|

53.08 av.

49.17 min.

57.01 max. |

83.92 av.

83.19 min.

84.77 max. |

16.6 av.

15.22 min.

16.81 max.

|

1.41 av.

0.61 min.

2.35 max. |

Table 3.

Main characteristics of the system.

Table 3.

Main characteristics of the system.

| Variable |

Value |

| Location |

Zaragoza (Spain) (41.66°N, 0.88°W) |

| System lifetime |

25 years |

| Electrical load (First year) |

1.2 MW peak power, 6.14 GWh annual load (Nassar et al. [28], Section 3.1). |

| Annual increase in electrical load |

0.5% |

| Unmet load allowed |

0%. |

| Maximum grid power |

2 MW |

| Nominal discount rate |

8% |

| General inflation |

2% |

| Sell and purchase electricity Price |

RTP (First year market price Spain 2023) |

| Access charge |

0.02 €/kWh fixed. |

|

0.3 |

|

0 |

| Mean of electricity price inflation |

1% |

| Standard deviation of electricity price inflation |

0.5% |

PV:

|

|

| CAPEX |

0.855 €/Wac [50] |

| OPEX |

0.5% of CAPEX per year [51] |

| Nominal power (AC) |

0 to 5 MWac, steps of 1 MWac |

| Slope and azimuth |

35° and 0°. |

| Lifetime |

25 years |

|

0.5% [44] |

|

43 °C |

|

95% |

|

−0.41%/°C |

| PV inverter DC/AC ratio |

1.25 |

| Inverter efficiency |

Figure 15 [52] |

Wind turbines:

|

|

| CAPEX |

1.3 €/W [53] |

| OPEX |

2% of CAPEX per year[53] |

| Nominal power |

500 kW |

| Number in parallel |

0−10 |

| Lifetime |

25 years |

| Hub height |

53 m |

| Roughness |

0.1 m |

|

0.2 [37] |

|

98% |

| Power curve |

Figure 2 |

PHS:

|

|

| Pump/turbine reversible machine CAPEX (inc. civil works) |

1,000 €/kW |

| Pump/turbine OPEX |

1.5% of CAPEX per year + 0.35 €/kWh |

| Reservoirs CAPEX |

25 €/m3 (130 €/kWh considering 70 m head) |

| Lifetime |

50 years |

| Pump/turbine start-up costs |

0.1 €/MW [31] |

| Nominal power |

0.5–2.5 MW, steps of 0.5 MW |

| Nominal flow |

0.75–3.75 m3/s, steps of 0.75 m3/s |

| Efficiency curve |

Figure 3 |

| Pump minimum input power |

20% of nominal power |

| Head |

70 m |

| Upper reservoir duration: (h) |

2–20 h, steps of 2 h |

|

100% |

|

0% |

| Lifetime |

25 years |

|

0.6 m < Dp < 1.5 m. Calculated for each case to obtain a water speed of 2.5 m/s for nominal turbine flow. |

|

250 m |

|

0.8 |

|

0.05 mm |

|

70 m |

|

5 m |

Table 4.

Results of the different optimisations with the LSS system.

Table 4.

Results of the different optimisations with the LSS system.

| Project type |

LSS - Optimal system without PHS |

LSS - A (buy for arbitrage) -

Optimal with PHS |

LSS - B (no buy for arbitrage) - Optimal with PHS |

|

(MWac) |

3 |

3 |

3 |

|

× (MW) |

0.5 × 8 = 4 |

0.5 × 8 = 4 |

0.5 ×8 = 4 |

|

(MW) |

0 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

|

(dam3) |

0 |

5.4 |

5.4 |

| Storage duration (h) |

- |

2 |

2 |

|

, first year (€/kWh) |

- |

0.15 |

0.15 |

|

(%) |

- |

60 |

80 |

|

, first year (€/kWh) |

- |

0.048 |

0.048 |

|

, first year (€/kWh) |

- |

0.097 |

0.097 |

| PV energy (GWh/yr, average) |

5.14 |

5.14 |

5.14 |

| WT energy (GWh/yr, average) |

9.103 |

9.103 |

9.103 |

| Pump energy (GWh/yr, average) |

- |

0.241 |

0.224 |

| Pump run hours/starts per year (average) |

- |

556/467 |

567/478 |

| Hydro turbine energy (GWh/yr, average) |

- |

0.21 |

0.206 |

| Turbine run hours/starts per year (average) |

- |

404/307 |

385/280 |

| E sold (GWh/yr, average) |

7.367 |

7.478 |

7.441 |

| E purchased (GWh/yr, average) |

0.992 |

0.996 |

0.964 |

| UL (%) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| CAPEX (M€) |

7.765 |

8.4 |

8.4 |

| NPC (€) |

3.91 |

4.15 |

4.19 |

| LCOE (€/kWh) |

0.0464 |

0.0492 |

0.0497 |

Table 5.

Results of the different optimisations: PGS system.

Table 5.

Results of the different optimisations: PGS system.

| Project type |

PGS - Optimal system without PHS |

PGS - A (buy for arbitrage) -

Optimal with PHS |

PGS - B (no buy for arbitrage) - Optimal with PHS |

|

(MWac) |

2 |

3 |

3 |

|

× (MW) |

0.5 × 5 = 2.5 |

0.5 × 5 = 2.5 |

0.5 × 5 = 2.5 |

|

(MW) |

0 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

|

(dam3) |

0 |

16.2 |

16.2 |

| Storage duration (h) |

- |

6 |

6 |

|

, first year (€/kWh) |

- |

- |

- |

|

(%) |

- |

60 |

60 |

|

, first year (€/kWh) |

- |

0.048 |

0.048 |

|

, first year (€/kWh) |

- |

0.048 |

0.048 |

| PV energy (GWh/yr, average) |

3.417 |

5.125 |

5.125 |

| WT energy (GWh/yr, average) |

5.682 |

5.682 |

5.682 |

| Pump energy (GWh/yr, average) |

- |

0.884 |

0.875 |

| Pump run hours/starts per year (average) |

|

2039/691 |

2134/700 |

| Hydro turbine energy (GWh/yr, aver.) |

- |

0.731 |

0.722 |

| Turbine run hours/starts per year (aver.) |

- |

1650/624 |

1634/623 |

| E sold (GWh/yr, average) |

8.529 |

9.851 |

9.816 |

| E purchased (GWh/yr, average) |

0 |

0.042 |

0 |

| CAPEX (M€) |

4.96 |

6.72 |

6.72 |

| NPV (€) |

1.979 |

1.688 |

1.698 |

| LCOE (€/kWh) |

0.0536 |

0.061 |

0.0611 |

Table 6.

Resources data for the different locations.

Table 6.

Resources data for the different locations.

| Location |

Zaragoza

(Section 3.2.1) |

Gran Canaria |

Sabiñánigo |

| Latitude and longitude (°) |

41.66N, 0.88W |

27.81N, 15.43W |

42.50N, 0.36W |

| Optimal PV slope (°) |

35 |

15 |

35 |

| Average annual Irradiation over the optimal inclined surface (kWh/m2) |

2,013 |

2,343 |

1,977 |

| Average temperature (°C) |

15.45 |

20.01 |

10.75 |

| Average wind speed (m/s) at 53 m hub height |

6.96 |

8.31 |

5.6 |

| Wind speed Weibull form factor |

2.9 |

3.8 |

2.8 |

Table 7.

First year electricity sell price data.

Table 7.

First year electricity sell price data.

| RTP Electricity price, first year data |

Spain 2023 (Section 3.2.2) |

Hypothetical price |

| Hourly electricity price: |

|

|

| Average (€/kWh) |

0.0871 |

0.0598 |

| Standard deviation (€/kWh) |

0.0414 |

0.056 |

| Maximum (€/kWh) |

0.221 |

0.3286 |

| Minimum (€/kWh) |

0 |

0.0009 |

| Average from 10–16 h: |

0.0661 |

0.0915 |

| Daily difference (max.–min.): |

|

|

| Average (€/kWh) |

0.0733 |

0.181 |

| Standard deviation (€/kWh) |

0.0315 |

0.0485 |

| Maximum (€/kWh) |

0.191 |

0.3219 |

| Minimum (€/kWh) |

0.0043 |

0.0293 |

Table 8.

PHS CAPEX needed for the PV-wind-PHS system to be competitive with the PV-wind system without storage.

Table 8.

PHS CAPEX needed for the PV-wind-PHS system to be competitive with the PV-wind system without storage.

| |

Zaragoza |

Gran Canaria |

Sabiñánigo |

| LSS system |

850 €/kW + 20 €/m3

|

350 €/kW + 10 €/m3

|

450 €/kW + 15 €/m3

|

| PGS system |

700 €/kWh + 17.5 €/m3

|

400 €/kW + 15 €/m3

|

600 €/kW + 20 €/m3

|

Table 9.

Effect of the type of system. Optimal LSS–A–547 €/kW + 2.7 €/m3.

Table 9.

Effect of the type of system. Optimal LSS–A–547 €/kW + 2.7 €/m3.

| |

Results obtained (type A) |

Results after changing to type B |

| E. pump (GWh/yr) |

2.556 |

2.048 (−19.9%) |

| E. turb (GWh/yr) |

2.061 |

1.628 (−21%) |

| E. buy (GWh/yr) |

1.813 |

1.182 (−34.8%) |

| E. sell (GWh/yr) |

7.140 |

6.621 (−7.3%) |

| NPC (M€) |

3.210 |

3.527 (+13%) |

Table 10.

Effect of the high/low limit set point for arbitrage. Optimal LSS–A–547 €/kW + 2.7 €/m3.

Table 10.

Effect of the high/low limit set point for arbitrage. Optimal LSS–A–547 €/kW + 2.7 €/m3.

| |

Results obtained

( = 0.0484 €/kWh = 0.0484 €/kWh) |

Results after changing:

- 0.02 €/kWh + 0.02 €/kWh |

| E. pump (GWh/yr) |

2.556 |

1.944 (−24%) |

| E. turb (GWh/yr) |

2.061 |

1.552 (−24.7%) |

| E. buy (GWh/yr) |

1.813 |

1.56 (−14%) |

| E. sell (GWh/yr) |

7.140 |

7.048 (−1.3%) |

| NPC (M€) |

3.210 |

3.353 (+7.5%) |

Table 11.

Effect of the minimum hydro turbine load set point. Optimal LSS–A–547 €/kW + 2.7 €/m3.

Table 11.

Effect of the minimum hydro turbine load set point. Optimal LSS–A–547 €/kW + 2.7 €/m3.

| |

Results obtained

(P% = 60%) |

Results after changing: P% = 40% |

Results after changing: P% = 80% |

| E. pump (GWh/yr) |

2.556 |

2.590 (+1.3%) |

2.486 (−2.8%) |

| E. turb (GWh/yr) |

2.061 |

2.077 (+0.8%) |

2.015 (−2.3%) |

| E. buy (GWh/yr) |

1.813 |

1.831(+1%) |

1.792 (−1.2%) |

| E. sell (GWh/yr) |

7.140 |

7.144 (+0.1%) |

7.119 (−0.3%) |

| NPC (M€) |

3.210 |

3.218 (+3.1%) |

3.237 (+3.8%) |