1. Introduction

We recommend a series of actions that policy-makers can take to improve enabling conditions for high-quality blue-carbon projects and promote equitable outcomes, particularly for women and Indigenous communities. To clarify ownership and rights, governments can invest in gender equitable participatory mapping; maintain a registry of ownership; and mandate gender-equitable engagement with Indigenous Peoples and local communities. Where land ownership changes under intentional barrier removal, carbon rights should be retained by the landowner; otherwise, there is little incentive to undertake blue-carbon projects. Governments can act to ensure adequate pricing and distribution of benefits from blue-carbon projects. Due to the limited income available from some carbon credit payments, other crediting and non-market methods should be considered to supplement landowners’ incomes and encourage habitat protection. Policy makers can use public funds to increase the investment-readiness of projects, address knowledge gaps, and conserve coastal wetland areas that are less suited to market-based mechanisms. Conflicting priorities between agencies managing coastal wetlands can be resolved through systematic restructuring/streamlining and collaborative planning processes. This might require changes to policies and amending delegated legislation. Governments can also support more effective enforcement by providing clear guidance through a national code of practice.

Key Policy Insights

First systematic review blue-carbon policy gaps and challenges in the Asia-Pacific with a focus on resolving these challenges to enhance enabling conditions.

Exclusion of women and indigenous peoples and local communities harms both project success and the opportunity for equitable outcomes. These groups should always be involved in project design and leadership.

To clarify ownership and rights, governments can invest in gender equitable participatory mapping, maintain a registry of ownership, and mandate gender-equitable engagement with indigenous peoples and local communities.

Due to the limited income available from some carbon credit payments, other crediting and non-market methods should be considered to supplement landowners’ incomes and encourage habitat protection.

Conflicting priorities between agencies managing coastal wetlands can be resolved through systematic restructuring/streamlining and collaborative planning processes. This might require changes to policies and amending delegated legislation.

Ongoing anthropogenic climate change, caused primarily by fossil fuel-burning-associated carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, poses a significant existential threat to ecosystems and to humans worldwide (Pörtner et al., 2022). Vegetated habitats absorb CO2 and sequester it in the soil, and saline coastal wetlands are particularly effective carbon sinks, sequestering 3-4 times more CO2 per unit area and at a faster rate than terrestrial forests (Byun et al., 2019; Crosta et al., 2023; NOAA, 2023). The protection, restoration, and creation of coastal wetlands are thus extremely effective means of mitigating anthropogenic climate change (e.g. Nellemann et al., 2009; Armistead, 2018; Wood and Ashford, 2023; Macreadie et al., 2021). The carbon stored in these habitats (salt marshes, mangrove forests, and seagrass meadows) is often referred to as blue carbon (Nellemann et al. 2009). We limit our discussion to these three ecosystem types because they are represented in carbon credit schemes, which create a monetary incentive to remove CO2 from the atmosphere by allowing companies or governments to partly meet their carbon neutrality goals through purchasing carbon credits, representing fungible units of CO2 sequestration (Climate Commission 2024 and Kenton 2024). While other coastal ecosystems (e.g., macroalgae) may provide significant blue-carbon sinks, insufficient data exists regarding the fate of carbon in these environments, thus they are excluded from blue-carbon markets (CMs) (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2019; Jones, 2021; Northrop et al., 2021; Friess et al., 2022).

1.1. The Value of Coastal Wetland Ecosystem Services

Coastal wetlands sequester 7-20% of all global CO2 emissions (UN ESCAP et al., 2023), and are particularly important in the Asia-Pacific region (defined sensu UN ESCAP, 2021), which contains an estimated 50.6% of the planet’s mangroves (Bunting et al., 2018), 35.8% of the planet’s salt marshes (Mcowen et al., 2017), and ~57% of the planet’s seagrasses (Fortes et al., 2020). Beyond carbon sequestration, the benefits of restoring and protecting coastal wetland habitats include:

Protecting uplands from flooding and erosion (e.g. Alongi, 2008; Dept. Fisheries, 2012; Marois and Mitsch, 2014; Möller et al., 2014; Pearce, 2014).

Tourism and recreation (e.g. Charkraborty et al., 2020; Moore et al., 2022; Hawes, 2023)

Food (e.g. Dept. Fisheries, 2012; Bhomia et al., 2016; Everard, 2014; Carrasquilla-Henao et al., 2019).

Building resources (e.g. Daiber, 1986; Nguyen et al., 2015; Palacios and Cantera, 2017).

Habitats for threatened and commercially-important wildlife (e.g. WRC 2016; Hamilton et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2023).

Filtering runoff, thereby protecting nearshore subaqueous habitats (including coral reefs) from pollution and smothering (e.g. Cochard, 2017; Theuerkauff et al., 2020).

Altogether, coastal wetlands contribute an estimated $3.4 trillion USD to the region’s economy in ecosystem services annually (Davidson et al., 2019), and are relied upon for food, resources, and income by millions of people (Trent, 2022). Despite the importance of these ecosystems, 0.5-2% of coastal wetlands are lost each year globally (Scott et al., 2014; Blue Carbon Initiative, 2019) and over 50% of mangrove forests are at risk of collapse before 2050 (IUCN, 2024). Around 70% of this coastal wetland loss has occurred in the Asia-Pacific region over the last 25 years (UN ESCAP et al., 2023), and, from 2000-2020, 43% of this decline was driven by conversion to aquaculture, oil palm plantation, and rice paddies (Leal and Spalding, 2024). The Asia-Pacific region is therefore highly important in the conservation (e.g., restoration and protection) of coastal wetlands.

1.2. Barriers to Coastal Wetlands Conservation, Including Equity

Due to their significant value in tackling climate change, coastal wetlands conservation projects can potentially be funded by revenue from carbon credits (e.g. Friess et al., 2020; Jones, 2021; DCCEEW, 2022; Kuwae et al., 2022; Vanderklift et al., 2022; Bell-James, 2023a; VCMI, 2023). High quality blue-carbon projects (defined sensu Conservation International et al., 2022; Landis, 2022) are projects which “conserve, protect, and restore lost and degraded coastal ecosystems” while achieving five criteria: 1. Safeguard nature; 2. Gender-equitable empowerment of Indigenous and local people; 3. Operate locally and appropriately in their regional environmental and economic context; 4. Employ the best available information and carbon accounting principles; 5. Mobilize high-integrity capital, ensuring that agreements, contracts, pricing, and benefit-sharing are fair. However, major barriers exist to initiating these projects, as evidenced by their under-representation in the nature-based solutions CM.

To identify and catalog challenges to initiating high-quality blue-carbon projects and find examples where policy solutions helped resolve these barriers, we conducted a thorough review of the existing literature (Appendix 1) and solicited supplemental information from assorted practitioners, experts, and other interested parties working in coastal environments. From our findings, we then recommended policy solutions that may facilitate future implementation of high-quality blue-carbon projects. Throughout our analysis of the existing literature and discussions with practitioners, we paid special attention to challenges that disproportionately impacted Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPs and LCs) and other vulnerable groups, such as women, who often rely heavily upon coastal wetland environments (e.g. Januar et al. 2022; Moore et al., 2022; Scott et al., 2024) but are regularly sidelined or ignored in policy and management decisions around coastal wetlands (Larson et al., 2015;Barletti et al., 2022; Lofts et al., 2021a; Pricillia et al., 2021; Schindler Murray et al., 2023; James et al., 2023).

Women are frequently disadvantaged in the development of blue-carbon projects and sometimes lose access to these essential habitats (e.g. Bosold, 2012; Thomas, 2016; TNC, 2017; Ban et al., 2019; Loch and Reichers, 2021; Giangola et al., 2023). Therefore, improving intersectionality, or the interaction across multiple overlapping axes of discrimination (Crenshaw, 1989; UN WA, 2019; James et al., 2022), must be treated as an essential aspect in resolving the policy gaps and challenges addressed throughout this study. Improving the rights of women involved in managing coastal wetland environments can also contribute to United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 5: To achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls (UN DESA, 2023). In our paper, we use “women” to include cisgender women, transgender women, femme/feminine-identifying, genderqueer and nonbinary individuals, who are all at a greater risk of gender-based inequality and discrimination (Thorne et al., 2019; James et al. 2023).

2. Methods

2.1. Primary Literature Collection

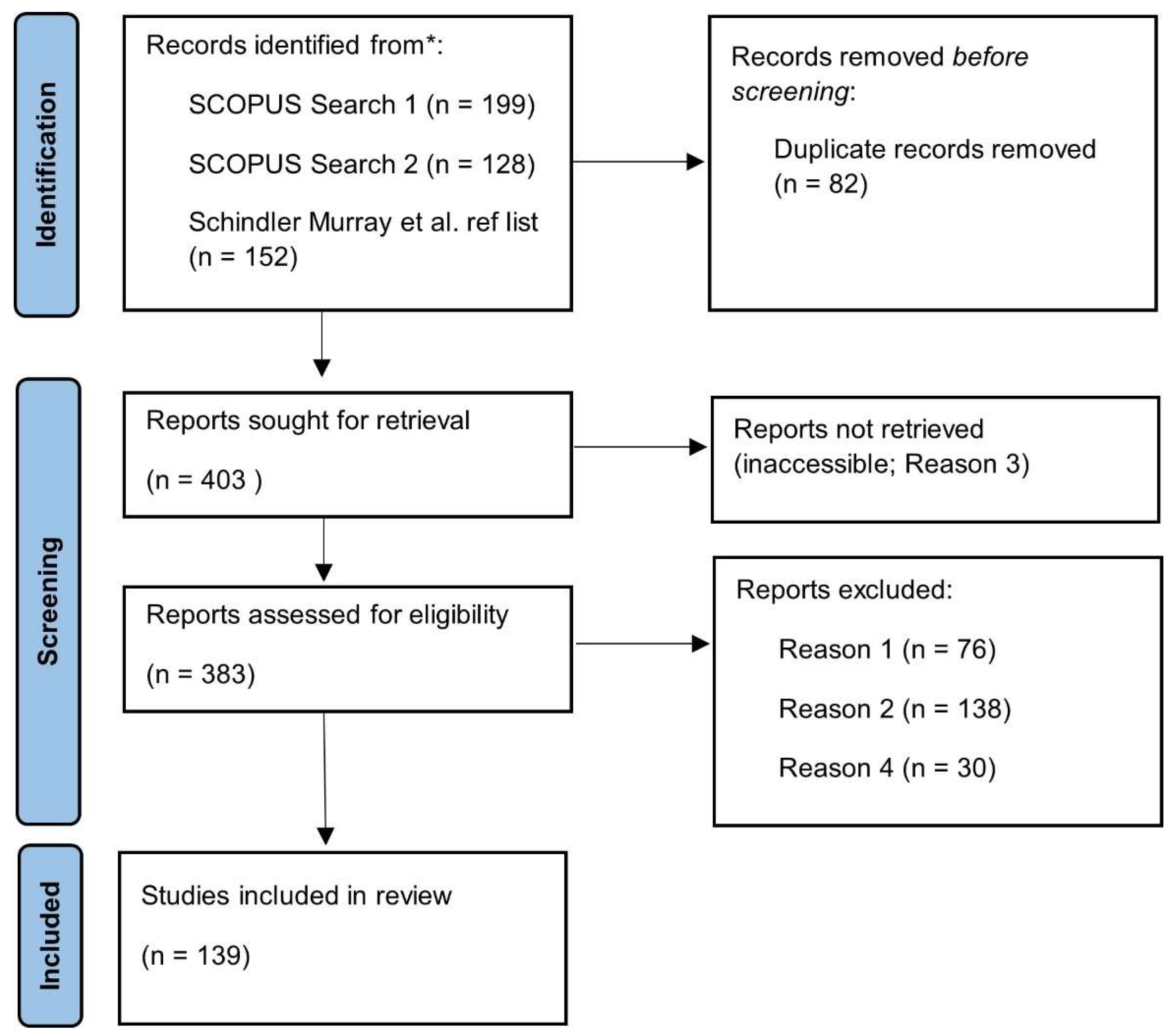

On 19th September 2023, we conducted a literature search of peer-reviewed scientific articles using the scientific indexing database SCOPUS (

https://www.scopus.com/) through two searches through article titles, abstracts, and keywords (

Figure 1). The first search (Source 1 in Appendix 1) was for “blue carbon” AND “policy” and yielded 199 articles. The second search (Source 2 in Appendix 1) was for “carbon sequestration” AND “policy” AND “salt marshes” OR “salt marsh” OR “saltmarshes” OR “saltmarsh” OR “mangroves” OR “mangrove” OR “seagrass” OR “seagrasses” OR “sea grass” OR “sea grasses” and yielded 128 articles. We used an additional key resource, “The Blue Carbon Handbook” (Schindler Murray et al., 2023), to source papers via its reference list (Source 3 in Appendix 1), which contained 152 documents. Six grey literature reports and books were provided by The Nature Conservancy (TNC) (Source 4 in Appendix 1). In total, we gathered 403 resources (papers, books, book chapters, and conference papers) and then applied the following rejection criteria to review a final selection of 139 papers:

1 – Paper does not cover projects in the Asia-Pacific.

2 – Paper does not discuss policies directly impacting blue-carbon projects.

3 – Paper is inaccessible/Not available.

4 – Paper does not cover projects in coastal wetlands (salt marshes, mangrove forests, and seagrass meadows).

We initially catalogued the findings from the 139 documents into one of nine topics to organize our synthesis: “gender equity and land tenure”, “interventions for rights/zonation”, “accounting for de-facto vs statutory ownership”, “difficulty accessing land ownership data”, “legislative mismatch between restoration and development”, “conflicting priorities between management agencies”, “non-achievable/non-scientific targets”, “distribution of benefits to landowner vs. resource user” and “valuing/accounting for natural capital/resilience” (Appendix 1). These nine topics were identified as potential barriers to coastal ecosystem conservation during a prior workshop with 30 TNC Asia-Pacific staff in 2023. We summarized the results from our synthesis into three main themes that incorporate all challenges common across multiple countries: unclear land tenure and ownership, insufficient funding and protection, and conflicting priorities and jurisdictions, with the additional overarching considerations of ensuring the rights of IPs and LCs and gender equity.

2.2. Practitioner Consultations

To assess the in-the field accuracy of the literature review findings and identify any additional challenges to the origination of blue-carbon projects in Asia-Pacific countries not covered in the primary literature, we consulted with practitioners in these environments and projects using the following avenues:

Four virtual workshops with 30 TNC personnel working on blue-carbon projects across the Asia-Pacific to discuss barriers and potential solutions (conducted through Microsoft Teams on November 8 and 9, 2023). We held the workshops with TNC staff because most of this paper’s authors are TNC employees and thus could identify relevant TNC personnel in the Asia-Pacific Region. Additionally, as a global organization, TNC has been involved in scoping and developing several blue-carbon projects across the Asia-Pacific region.

A survey (Appendix 3) sent to the above 30 TNC workshop attendees and 17 external partners identified by TNC staff or through the primary literature review involved in the management or implementation of coastal wetlands.

Nine interviews conducted with practitioners, experts, and other interested parties based on their specific expertise and/or experience, as identified through the literature review or by TNC workshop participants. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and the transcriptions assessed for information in each category of information (Appendix 4).

All interview and workshop participants were anonymised and assigned a random alphanumeric (e.g., 75vzi) using GIGACalculator (2023), though an option to be named in the paper was also provided.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Findings

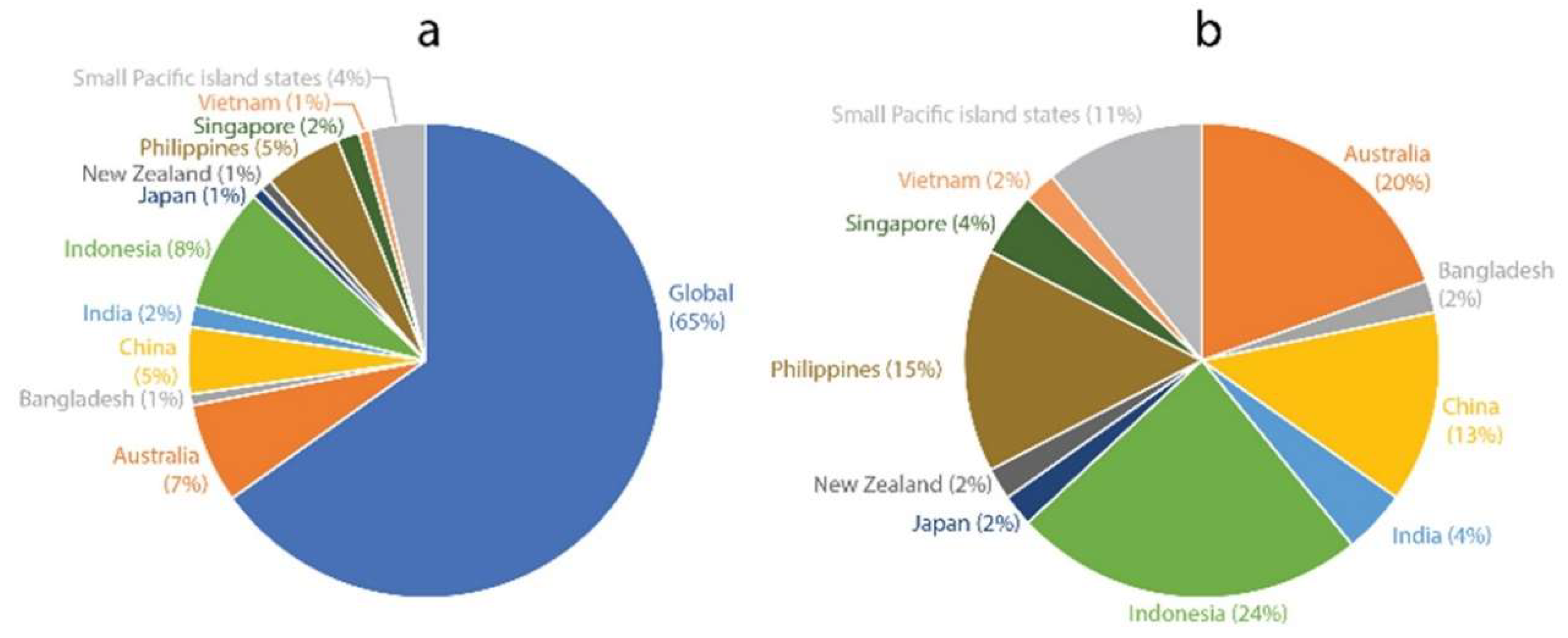

Of the 139 papers gathered through the SCOPUS search, 27% of papers discuss land tenure/ownership issues, 65% discuss the funding and protection of coastal wetlands, and 40% discuss conflicting jurisdictions and priorities between agencies. Of these studies, 65% were global studies, with Indonesia (8%) and Australia (7%) the most well-documented countries (

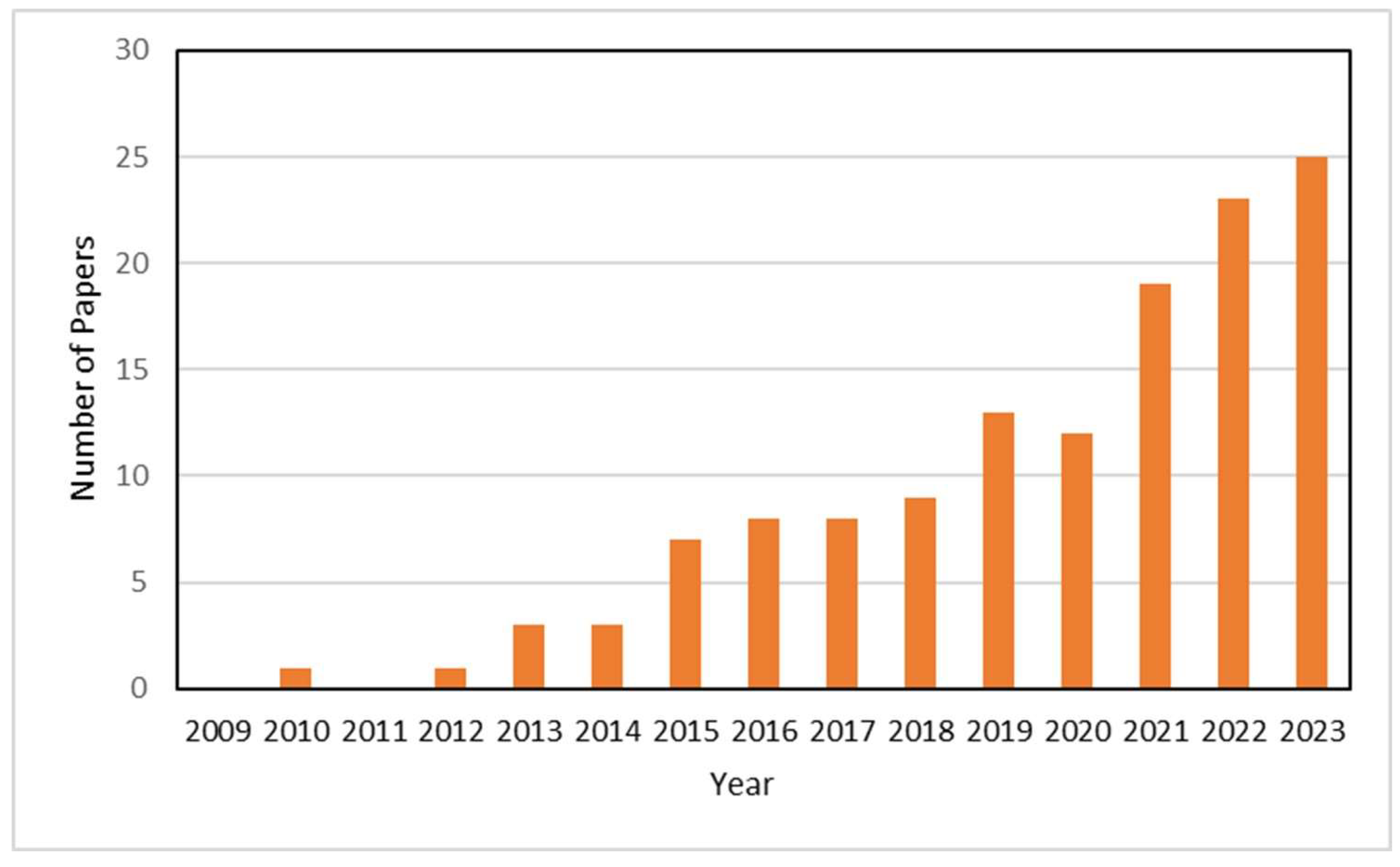

Figure 2). Equity was not broadly addressed in the literature, with only 5% of these papers discussing gender equity and 17% discussing IP and LC rights and tenure. Since 2009, the number of papers covering blue-carbon policy in the Asia-Pacific region has almost consistently increased annually, demonstrating an ever-growing interest in the carbon sequestration or ecosystem services provided by these ecosystems (

Figure 3).

We received eight responses (Appendix 3) to our survey requests from participants with experience in projects based in Aotearoa New Zealand (n=2), Australia (n=1), Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (n=1), India (n=1), Indonesia (n=2), and Malaysia (n=1). Of the survey respondents, four were TNC employees, three were external, and one remained anonymous to the authors.

Our nine interviewees worked on projects in Fiji (n=1), Australia (n=2), Indonesia (n=4), and Aotearoa New Zealand (n=1). Of these interviewees, two were TNC employees and seven were external.

3.2. Unclear Land Tenure and Ownership

Difficulty in accessing land-ownership data provides a direct challenge to the implementation of nature-based solutions and blue-carbon projects (Hejnowicz et al., 2015; Beeston et al., 2020; Hamrick et al., 2023; Interviewee Janet Hallows) and for land-owners looking to access financial incentives for conservation (Hejnowicz et al., 2015; Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2019). Uncertain tenure was identified as a problem in approximately one third of all REDD+ projects (forestry-based carbon-sequestration projects, where REDD stands for “reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries and ‘+’ stands for additional forest-related activities that protect the climate, namely sustainable management of forests and the conservation and enhancement of forest carbon stocks) (Hamrick et al., 2023).

3.2.1. Establishing Tenure for IPs and LCs

In much of the world, while IPs and LCs have customary rights, or ownership born out of custom or tradition, to the land they occupy (e.g. Bouvier, 1856; Huggins, 2012), these rights are often not legally recognized (Warner et al., 2016; Lofts et al., 2021b; Song et al., 2021; Lasheras et al., 2023; Hamrick et al., 2023). This lack of legal recognition has often led to the exclusion of IPs and LCs from the project planning process and opened them up to exploitation by carbon project developers.

Of the ten Asia Pacific countries reviewed for the status and recognition of their IP and LC carbon rights, seven legally recognized IP and LC carbon rights, with carbon rights being poorly defined, and three had ambiguous laws regarding IP and LC carbon rights (Lofts et al. 2021b). In Indonesia, carbon rights for IPs and LCs are “partially recognized” by law, with non-uniform issuing of tenure rights and regulations to these communities that vary by district (Lasheras et al., 2023). This has contributed to a lack of involvement of IPs and LCs in mangrove restoration projects and significant negative impacts to their livelihoods (Warner et al., 2016).

3.2.2. Gender Inequities in Land Ownership

Even where IP and LC land tenure is recognised and upheld, women in coastal wetland ecosystems may not receive equitable benefits from carbon projects because they rarely own the land (Pearson et al, 2019; James et al. 2023). Exclusion from carbon projects harms women in three ways: 1. exclusion from any financial benefits (i.e. carbon credits) tied to land ownership; 2. denied access to an essential resource once it takes on a new financial value for others in the community; and 3. higher personal risk (e.g. gender-based violence) if they continue accessing these resources (Minney, 2020; James et al., 2023). Blue carbon projects that exclude women, IPs, and LCs from decision making are also consistently less successful than projects centering them (Lauer and Aswani, 2010; Thompson et al., 2017; Vierros, 2017; Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2019; Ban et al., 2019; Pricillia et al., 2021; Barletti et al., 2022; Macreadie et al., 2022; Chanda and Akhand, 2023; Schindler Murray et al., 2023; James et al., 2023).

Across the Asia-Pacific, women are less likely than men to exclusively own land (Swaminathan et al. 2017). Globally, women make up only 12.8% of agricultural landowners, while being disproportionately affected by economic crises in coastal wetlands (Minney, 2020). Thus, women stand to lose out if benefits of carbon credits are exclusively tied to land tenure and if the processes of determining carbon rights do not recognize the patriarchal systems of land ownership that projects are operating within (James et al 2023). Our interview, literature review, and workshop responses combined show carbon practitioners rarely consider gender in project development.

3.2.3. Impacts of Restoration and Sea-Level Rise on Ownership

In some countries, changes to the tidal regime that alter the mean high-water line (e.g., removing coastal barriers in conservation projects) may alter land ownership status by moving a site into public waters (Macreadie et al., 2022; Bell-James, 2023b; Dencer-Brown et al., 2022; Urlich and Hodder-Swain, 2022; Stewart-Sinclair et al., 2024). Landowners who consider using carbon projects or other payments for ecosystem services (PES; Tacconi, 2012) to finance coastal restoration projects through restoring tidal flows face uncertainty about whether the state may have a claim on their lands and any carbon payments (Macreadie et al., 2022; Bell-James, 2023b).

For example, in Fiji, while local people can theoretically receive land and carbon rights, there is no existing process that allows them to retain rights below the mean high-water line (interviewee Mei Zi Tan). In Australia’s Northern Territory, “marine waters” (public land) are defined by the position of the high-water mark (Sangha et al., 2019; interviewees 9dzh; Elizabeth Macpherson), which will change once a site is opened to tidal influence. Sea-level rise can create similar uncertainty regarding land ownership, as it will also alter the mean high-water line, albeit on a much slower (decadal) timescale than the immediate removal of barriers (interviewee Mei Zi Tan).

3.3. Funding and Protection of Coastal Wetlands

3.3.1. Size of Payments

Many challenges hinder the adequate funding of coastal ecosystem conservation or restoration projects through carbon credit and other PES schemes. These challenges stem from difficulties in valuing ecosystem services provided by coastal wetlands (Hejnowicz et al., 2015; Friess et al., 2016; Gevaña et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2019; Chanda and Ghosh, 2022), uncertainty in the spatial extent of carbon stocks and magnitude of carbon-fluxes across the Asia-Pacific region (e.g. Macreadie et al., 2014; IPBC, 2015; Rogers et al., 2016; Moraes, 2019; Thuy and Thuy, 2019; Sejati et al., 2020; Alemu et al., 2022; Corcino et al., 2023; Howard et al., 2023), inequities in CMs (Huxham et al., 2020), and inadequate investment in voluntary carbon markets relative to compliance markets (Huxham et al., 2020; Hamrick et al., 2024). For example, inadequate mapping of seagrasses, combined with their fragile nature, challenges the demonstration of permanence for a site (interviewee Janet Hallows). This has led to Australia excluding seagrasses from their emissions reduction program (Kerin et al., 2021).

Existing carbon credit prices for nature-based carbon projects, particularly in the voluntary CM, are too low to be the sole income source to support many landowners, and inadequate with respect to their true cost and value (Hamrick et al. 2023). In Australia for example, high restoration costs can delay blue-carbon project profitability by decades (Hejnowicz et al., 2015; Jones, 2021; Knight et al., 2022). Globally, high start-up costs and extensive resources required for project initiation and creating enabling conditions (Huxham et al., 2020) render projects less attractive for investors (Potouroglou et al., 2020), challenging project initiation. Furthermore, around 80% of the average carbon credit price across Asia-Pacific goes to project developers without benefiting LCs (Crosta et al., 2023). This unequal distribution of incentives fails to deter land users, including IPs and LCs, from mangrove-degrading activities such as shrimp aquaculture, rice paddies, and logging (Warner et al., 2016; Gevaña et al., 2018; Miller and Tonoto, 2023).

3.3.2. Land Valuation and Regulatory Disincentives

Counterintuitively, consistently high demand for coastal property in spite of sea-level rise means that prices for coastal properties, and thus opportunity costs for the initiation of blue-carbon projects that require land purchases, are increasing (Runting et al., 2017; Workshop participant 9rzng). While discussion of this issue is limited to Australia in published literature, multiple workshop participants and interviewees outside of Australia considered the economic value of coastal land to be a significant issue. For example, Hong Kong’s government has preferred conversion of wetland habitat into housing and technology industry land use instead over prioritizing blue-carbon habitats (Interviewee Felix Leung).

50% of survey participants stated that it was “hard” and 50% stated that it was “somewhat hard” in their countries to obtain permits or approval for wetland restoration. In Australia, there are significant difficulties obtaining permits for use in restoring or creating blue carbon habitats, due in part to the legislative mismatch in which applications to restore an environment by planting seagrass or breaching a barrier to the sea are legally considered dredging or development and treated the same as those environmentally harmful activities (Kelleway et al., 2020; Bell-James, 2023a; 2023b; Carmody, 2023; 2024). This restricts Australia’s abilities to meet their sequestration targets (Bell-James et al., 2023a) and creates significant regulatory approval challenges and fees that may be too expensive for small-scale local landowners (Carmody, 2023; Bell-James et al., 2023a).

3.3.3. Additionality

For carbon credits to be generated, project developers must demonstrate additionality - that the carbon would not have been sequestered without the establishment of the new carbon project (e.g. Pham et al., 2013; Ullman et al., 2013; Ralph et al., 2018; Moraes, 2019; Vanderklift et al., 2022). This means that there is clearer economic incentive to restore damaged wetlands, but can make it difficult to attract private investment to protect existing coastal ecosystems and their carbon stocks that are not under apparent imminent threat (Pham et al., 2013; Ullman et al., 2013), leading to many countries having policies and programs that prioritize restoration over protection (Macreadie et al., 2014; Interviewees 75vzi and Ibp2I). Additionality may be particularly hard to prove in seagrass systems (Interviewee Janet Hallows), resulting in them being neglected by protection and restoration policies in comparison with other coastal wetlands (Potouroglou et al., 2020).

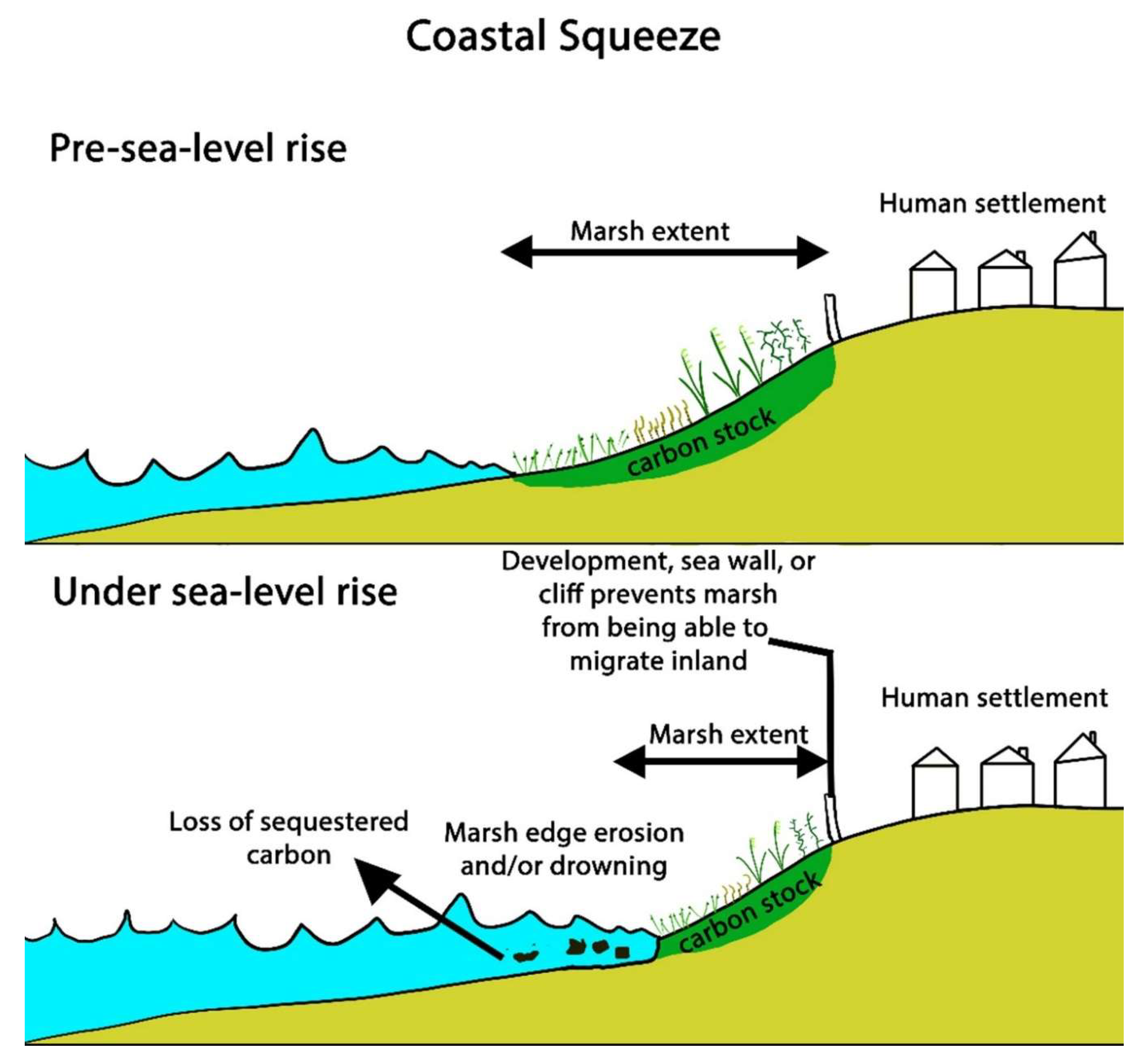

3.3.4. The Challenge of Sea-Level Rise

Under sea-level rise, many coastal wetlands are eroding or being submerged at their seaward ends, and migrating landward, where they can be “squeezed” against coastal settlements and barriers (e.g. Blankespoor et al., 2014; Figueira and Hayward, 2014; Hansen and Reiss, 2015; Moraes, 2019; Primavera et al., 2019; Swales et al., 2020; Crosta et al., 2023) (

Figure 4). This limits the fundability of blue-carbon projects since most carbon registries have a permanence requirement of 40 years and coastal wetlands restoration projects that lose area to erosion and coastal squeeze will have reduced carbon income potential.

Globally, policies around coastal wetlands have failed to account for coastal squeeze (Urlich and Hodder-Swain, 2022) and most Asia-Pacific countries have no regulations in place that require wetland restoration and protection projects be permitted room to migrate inland (e.g. Wylie et al., 2016; Urlich and Hodder-Swain, 2022; Bell-James et al., 2023a)), with Tasmania and New South Wales being notable exceptions in Australia (Bell-James, 2020; Bell-James et al., 2023a).

Land subsidence-enhanced sea-level rise also affects Indonesian mangroves, with many mangrove forests subsiding faster than can be managed by mangrove-planting schemes. While this has been addressed by regulations on groundwater use to reduce subsidence (Kementerian ESDM, 2023), with further related policies already in-place around green-belt and riverine environments, these have been sub-optimally enforced (Interviewee 2vzhc). Furthermore, in China 60% of the entire country’s coastline is protected by seawalls (Bell-James, 2020), which lie inland of 90% of the country’s mangroves (Daming et al., 2020), severely restricting their long-term survivability. Simply restoring and protecting blue-carbon habitats may not protect them in the long-term without removing some coastal barriers and settlements.

3.3.5. Knowledge-Related Issues

A lack of awareness by local people about blue carbon and CMs was noted as a potential barrier to originating blue-carbon projects by 85.7% survey participants, as well as by interviewees and workshop participants from Malaysia, Papua New Guinea (PNG), Indonesia and Hong Kong. Crosta et al. (2023) connected this lack of knowledge among local communities to a similar capacity deficit among local and regional authorities and the disconnect between scales of government (national, regional, local). In Malaysia, knowledge-related challenges have been the biggest hurdle to initiating blue-carbon projects, with stakeholders possessing limited knowledge of basic CM concepts and uncertain of how to create connections between ownership and finance mechanisms (interviewee Dr. Jamaludin).

In contrast to their lack of knowledge of CMs, IPs’ and LCs’ traditional knowledge of coastal habitats can be essential for the sustainable management of coastal wetlands, but is routinely undervalued or ignored (Lauer and Aswani, 2010; Vierros, 2017; Ban et al., 2019; Hoegh-Gulberg et al., 2019; Pricillia et al., 2021 Macreadie et al., 2022, Leal and Spalding, 2024). For example, Miller and Tonoto (2023) discussed an incident where restored mangroves were washed away by storms because they were planted on a budget-driven timescale during the monsoon season without consulting traditional landowners. The lack of consideration for habitat suitability (e.g., soil type, salinity level, water level, amount of inundation) and site ecology by project planners has led to survival rates of only around 25% in some mangrove plantation projects in Indonesia (Interviewees 75vzi and Ibp2I). Women, while primary users and managers of these resources, are often similarly left out of consultation (James et al., 2023).

3.4. Conflicting Jurisdictions and Priorities Among Agencies

Blue-carbon projects in the Asia-Pacific often fall under the jurisdiction of multiple different agencies and authorities. This may be due to limited coordination across different levels of government, historical and traditional reasons, or that both terrestrial and marine-based agencies can claim jurisdiction over coastal wetlands (Pham et al., 2013; Friess et al., 2016; Warner et al., 2016; Quevedo et al., 2021; Arifanti et al., 2022; Li and Miao, 2022; Macreadie et al., 2022; Urlich and Hodder-Swain, 2022; Bell-James, 2023a, Miller and Tonoto, 2023, NCSC, 2023; Sidik et al., 2023). Different authorities are not always incentivized to collaborate and may come up with independently-designed, contradictory restoration plans/strategies. This is particularly noted in Indonesia, the Philippines, and Aotearoa New Zealand, and is widely discussed in available literature (e.g. Friess et al., 2016; Warner et al., 2016; Quevedo et al., 2021; Arifanti et al., 2022; Macreadie et al., 2022; Bell-James, 2023a; Crosta et al., 2023; Miller and Tonoto, 2023; Sidik et al., 2023; Stewart-Sinclair et al., 2024).

For landowners, the large number of authorities responsible for managing or legislating coastal wetlands creates an environment of uncertainty regarding the process for obtaining blue-carbon project approvals and following sometimes contradictory regulations (Beeston et al., 2020; Macreadie et al., 2022; Urlich and Hodder-Swain, 2022; Quevedo et al., 2023; Bell-James, 2023a; Sidik et al., 2023). Regulatory hurdles to the development and protection of blue carbon can also stem from the priorities, funding, and management of the organizations in question. For example, some authorities have de-prioritized protection of blue-carbon environments due to economic valuations favoring other uses for the land (Hejnowicz et al., 2015; Miller and Tonoto, 2023). Authorities are also often tightly constrained by budget and may make decisions on the timing and details (species selection/location) of restoration projects based on budgetary constraints, and not science (Miller and Tonoto 2023).

Survey participants all agreed that challenges to coastal wetland restoration result from contradictory regulations stemming from different authorities, with 75% noting significant difficulties, and 25% noting somewhat significant difficulties. 87.5% of survey participants said that significant difficulties arose due to uncertainty over which agency is in charge of managing coastal wetland environments.

In Indonesia, unaligned goals across ministries, uneven funding among levels of government, and a lack of dissemination of knowledge from Central to District governments have led to conflicting jurisdictions and priorities, creating significant problems for the success of blue-carbon projects (Interviewees 2vzhc and 75vzi). Interviewee lbp2l noted that there have been contradictory actions put in place by different ministries regarding planting strategy, due in-part to the economic drive to enhance shrimp aquaculture in the region. Similarly, in India, contradictory regulations exist between protecting and restoring marine and forest environments and, depending on the level of connection between mangrove forests, terrestrial forests and the sea, different authorities have responsibility for the mangroves, creating an often-ambiguous situation (Workshop Participant 4q9st).

3.5. Lack of Adequate Funding for Enforcement

An issue borne out of all three of the aforementioned themes is that existing regulations designed to protect coastal wetlands are seldom enforced or implemented (Thomas, 2016; Thompson et al., 2017; Gu et al., 2018; Primavera et al., 2019; Denya & Peters, 2020; Rudianto et al., 2020; Chanda, 2022; Miller and Tonoto, 2023). Survey participants listed a number of reasons for this, including a lack of penalties, insufficient funding to those responsible for enforcing regulations, a lack of awareness of existing regulations, exploitable loopholes in regulations, corruption, underdeveloped legal frameworks, and a “shifting of responsibility” between agencies with overlapping authority.

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview of Findings

The existing literature on policies pertaining to the conservation of coastal ecosystems showed that the Asia-Pacific is not evenly represented in the research, with the vast majority of published information coming from Indonesia, Australia, and the Philippines. While the largest economic benefits from coastal wetlands in the Asia-Pacific are projected to occur in Indonesia and Australia (Bertram et al., 2021), some countries (e.g., PNG) were clearly under-represented in relation to the size of their coastal ecosystems (

Figure 2). However, our surveys, interviews, and workshops with practitioners working across the region supplemented many major gaps in the available literature.

While we recognize that our survey of existing barriers to coastal ecosystem conservation is likely incomplete, we expect that our identified issues are regionally relevant. In the following sections, we present a series of recommendations to improving access to carbon-financing for coastal ecosystem conservation work, based on successful examples from countries in the region. We believe that these recommendations can resolve many of the issues identified in this study and can contribute to facilitating future coastal ecosystem restoration in the Asia-Pacific.

4.2. Unclear Land Tenure and Ownership

4.2.1. Invest in Gender Equitable Participatory Mapping of Tenure Rights

One essential method for improving enabling conditions for blue-carbon projects is to generate maps to resolve ownership uncertainty and clarify wetland boundaries. National strategies to resolve overlapping boundaries and unclear land rights are clearly necessary (Beeston et al., 2020), but these strategies must recognize and respect the customary rights of IPs and LCs.

Participatory boundary and land use mapping efforts with the active involvement of IPs and LCs are currently implemented by TNC in PNG in order to clarify land ownership for natural-resource management. PNG communities engage in these efforts by drawing their own lines, walking the boundaries using GPS devices where land is disputed, and creating birds-eye view maps that are then discussed and agreed to by clans, reducing conflict and helping to ensure that the right people can benefit from future blue-carbon projects (workshop participant 7dd8t). These efforts aid IPs and LCs in legally preventing deforestation by outsiders, and governments can support them and improve enabling conditions for PES through grants, such as Australia does with the Blue Carbon Accelerator Fund (workshop participant 4qs9t, DCCEEW, 2025).

Due to inequalities in land tenure and differences in natural resource use, gender must also be intentionally considered when undertaking participatory boundary and land use mapping to prevent reinforcement or worsening of gender inequality when implementing coastal conservation projects. Women representing a diversity of intersecting social identities (race, ability, income level, etc) must be actively engaged to ensure their rights are also upheld, their knowledge is included, and their interests are met in the mapping processes.

4.2.2. Mandate Equitable IP and LC and Gender Engagement for Blue-Carbon Projects

Currently there is a lack of legally-mandated safeguards for the rights of IPs and LCs and women in existing and developing blue-carbon projects across the region. While voluntary safeguards have been broadly applied to protect IPs and LCs and women (Barletti et al., 2021; 2022; Lofts et al., 2021a; Lasheras et al., 2023; UNFCCC, 2023; Hamrick et al., 2023), they are of limited effectiveness due to the lack of legal enforcement and insufficient funding. Companies may be encouraged to consider the “inclusion” and “participation” of IPs and LCs, but this language echoes a colonial dynamic and de-emphasizes IPs’ sovereignty over their land (interviewee Dr. Elizabeth Macpherson).

To ensure effective use of traditional knowledge and the most equitable outcome for customary landowners, governments should support IPs and LCs with the resources, capacity, and equitable processes to self-determine their role in blue-carbon projects (rather than being “permitted” to participate). Existing safeguard mechanisms for REDD+ projects (UNFCCC, 2023; UN REDD+ Programme, 2023; Verra, 2023) and critiques of these mechanisms (e.g. Lofts et al., 2021a; Barletti et al., 2022; Hamrick et al., 2023; Lasheras et al., 2023) can be used to guide the creation of laws and policies that prevent the exploitation of IPs and LCs and women in blue-carbon projects and mandate their involvement in project leadership, design, and development. As noted by Lofts et al. (2021a) and Hamrick et al. (2023), it is imperative that these policies exist to ensure that IPs and LCs and women are actually protected, empowered, and able to fully participate, as well as to support the ongoing credibility of voluntary schemes.

As part of this approach, comprehensive social and gender analyses and human rights-based impact assessments should be mandated at the scoping phase of projects in order to identify power dynamics and cultural and socioeconomic drivers of natural resource use. Disaggregating data by gender (and other social identities) will also identify who stands to lose or gain from a project. Resources and time should then be focused on working with communities to address the identified risks and opportunities to ensure benefits are equitable and safe and any risks are mitigated (James et al., 2023).

Examples of schemes that can be used as templates to improve IP and LC and women’s land rights include Plan Vivo’s carbon standard, which emphasizes and creates opportunities for IPs and LCs (Wrangham, 2023), and WOCAN’s W+ Standard that quantifies, verifies and generates income for women’s empowerment within projects (WOCAN, 2024).

4.2.3. Provide Access to Information Through Awareness Programs and Publicly Available Databases

Governments have an important role in providing access to information through awareness programs and public databases. Awareness programs, aimed towards local peoples and government, can help to improve and develop a shared understanding of blue-carbon projects as a mechanism for funding coastal wetland conservation, and are an important component of ensuring indigenous peoples’ right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent (UN DRIP, 2007). Education programs, ideally led by local experts, should discuss the causes and impacts of climate change and take account of the myriad ecosystem services, including blue-carbon sequestration, provided by coastal ecosystems, as well as help landowners accurately assess the economic value of coastal wetlands and what could be lost if they are transformed.

For example, TNC has been engaging with landowners, local communities, and particularly women, as part of Mangoro Market Meri to develop a shared understanding of how to benefit from mangrove protection and restoration and assess associated potential sources of revenue, from mud crabs to blue carbon. A similar community education program is ongoing in Australia to inform local people about carbon sequestration potential. These programs could be much more wide-reaching if funded and organized by governments at a federal or state-level. This might also include widely distributing user-friendly written materials or videos on mangrove importance, conservation and policy (Hayman, 2023), (Workshop participant 7668t) in local languages.

To increase transparency around project development and ensure that all appropriate stakeholders and rightsholders have equitable access to tenure information, maps of statutory and customary ownership and use rights should be made available in a public repository and adequately funded for regular updates. A template example to present this is the interactive tool used by Land Information New Zealand (LINZ) (2023) which displays land-ownership data. In PNG, a National Carbon Register is under review to record and verify carbon rights and the generation of carbon credits. This ensures the inclusion of carbon-sequestering environments in the country’s Paris Agreement NDCs, protects landowners’ carbon rights, and allows the government to track carbon sequestration, CM transactions, and land ownership changes, enhancing equity through increased transparency. In all cases, indigenous land rights should be honored following The Land Rights Standard (RRI, 2022).

4.2.4. Address Impacts of Restoration and Sea-Level Rise on Ownership

To clarify carbon rights and remove disincentives to coastal ecosystem restoration, governments need to enact policies clarifying if and how land ownership and governance will change under both sea-level rise and restoration scenarios (e.g., restoring tidal flows). This issue has been partially overcome in Australia through contractual agreements between landowners and various levels of government over the retention of carbon rights, even if land rights change due to the new tidal flows (Macreadie et al., 2022). In Aotearoa New Zealand, while land below the high-water mark is considered public, Māori are permitted to apply for customary marine title over an area under the Marine and Coastal Area Act 2011, which may enable traditional landowners to benefit from future CM schemes when established (Stewart-Sinclair et al., 2024).

4.3. Funding and Protection of Coastal Wetlands

4.3.1. Adequately Pricing and Distributing Benefits from Blue Carbon

Governments can set price floors, or send a signal by paying a high price for demonstrable high quality carbon credits, to encourage more accurate valuation of the protection and restoration of blue-carbon habitats. For example, Queensland’s Land Restoration Fund considers the cost of carbon credit generation as well as co-benefits delivered by a project when setting its price on its website; currently AUD $81.08 per tonne of CO2 (Queensland Government, 2023; 2024). The LEAF program, an initiative focused on jurisdictional REDD+ programs, also provides a valuable template, as it offers forward purchase agreements for an agreed price, with a floor price commitment of USD $10/ton for at least 100 million metric tons of CO2, making large projects more attractive to investors (LEAF Coalition, 2023; 2024).

It is also important to address the current inequitable distribution of carbon credit income, whereby 80% of profit goes to developers. Policies and mandatory safeguards must ensure a greater proportion of profits reach IPs and LCs and, crucially, that these benefits are equitably distributed within communities to ensure they also reach women and other vulnerable groups (see

Section 4.2).

One example of a program that has attempted to improve access to carbon project benefits is the World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Facility, which has distributed benefits from a jurisdictional REDD+ program to IPs and LCs in East Kalimantan Indonesia (Adityasari, 2022). These are being distributed as reward- and performance-based payments via a Benefit Sharing Mechanism, with village government and village community organizations set to receive benefits worth 119,368,448,400 Indonesian Rupiah (IDR) as performance allocation and IDR 11,430,000,000 as reward allocation, according to the East Kalimantan Governor Decree of 2023. However, in 2024, the project was criticized for sidelining the Dayak Bahau people, further emphasizing the importance of proper engagement and co-designing with IPs (MacInnes and Doq, 2024).

4.3.2. “Stacking” Economic Opportunities in Coastal Wetland Ecosystems

Carbon credits and economic mechanisms such as aquasilviculture (the practice of keeping or planting a significant mangrove population within a fish or shrimp pond), sea cucumber farming, and broader PES schemes, should be considered in concert whenever possible and utilized together to ensure that people stewarding coastal ecosystems can obtain maximum benefits (workshop participant x4886). In this regard, carbon credits are best viewed as a supplemental source of income, rather than a sole or even primary source, particularly in locations where other concurrent livelihoods exist. Other nature-based credit schemes should also be considered if they can provide additional financial support for the management of coastal wetlands, including PES schemes (Waage et al., 2008), biodiversity credits (Khatri et al., 2022), resilience credits, and the recently-proposed nature repair credits in Australia (DCCEEW, 2023). As additional crediting opportunities for environmental services develop, it is critically important that these are designed with compatibility with CMs as a key objective and that projects can access multiple crediting schemes where appropriate.

Aquasilviculture practices have been promoted for mangrove protection and economic development by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (KLHK) in Indonesia (Miller and Tonoto, 2023), and are being promoted as a means of both restoring mangrove ecosystems and providing an income for local people in other parts of Asia (Flores et al., 2016; Susitharan and Sindhu, 2021). Similarly, PNG is trialling sea cucumber ranching, which rewards protection as it can only be conducted in healthy seagrass ecosystems (Hair et al., 2016; 2022). These livelihood activities should be explored as potential income streams for IPs and LCs that would have limited impacts on their coastal ecosystems (Aziz et al., 2016; Warner et al., 2016; Wylie et al., 2016; Crosta et al., 2023).A major case study in how aquasilviculture might complement blue-carbon projects is demonstrated in the Mekong Delta with the Market and Mangroves (MAM) scheme. Active throughout Asia (Mangrove Alliance, n.d.), MAM works with governments and assists the drafting of policy to prevent deforestation by creating an economic incentive to protect at least 50% of existing mangroves. Communities or farmers that fulfil this criterion can supplement their income with carbon credits and obtain organic certification for their shrimp, allowing them to be sold at higher market prices. By 2016, this scheme greatly improved the livelihood of the ~6,000 participating farming households in the Mekong Delta while preventing the loss of 23.5 ha and protecting 3,371 ha of the region’s mangroves (Wylie et al., 2016). Similarly, a mangrove-retaining “eco-farming” program trialed in Guanxi, China, showed great promise for protecting the ecosystem, enhancing species richness, and restoring the wellbeing of the local community (Hangqing, 2021). These case studies may provide a template for governments looking to support the growing aquaculture field while limiting its impacts on mangrove ecosystems.

4.3.3. Remove Regulatory Disincentives

The particular legislative mismatch in Australia between restoration and development projects was not found to be a significant issue elsewhere. However, the lack of clarity around the permitting process for coastal restoration projects is a common barrier that needs to be rectified to improve the enabling environment for high quality blue-carbon projects (noted by 50% of survey participants). This could be done through removing fees for applications for coastal wetland restoration projects (but not for development projects) and creating a separate application pathway for projects aiming to restore coastal wetlands from those aiming to develop the coastline (Carmody, 2024).

4.3.4. Integrate Sea-Level Rise in Property Valuations for Coastal Areas

The high economic value of coastal land can reduce local governments’ willingness to originate blue-carbon projects or protect existing coastal wetlands (Runting et al., 2017; Adame et al., 2021; Primavera et al., 2019; workshop participant sjkfo). These high land-valuations should be reconsidered under the context of the impacts of sea-level rise on agriculture (e.g. Johnson, 2014; Genua-Olmedo et al., 2016; Jamwal, 2019) and urban land habitability (e.g. Bell et al., 2015; Hauer et al., 2020; Bell, 2021). Countries should develop sea-level projections based on long-term and short-term vertical land movement and relative sea-level change data across their coastlines, as templated by Naish et al. (2024) and NZ SeaRise (2022). These can be used alongside model projections of changes in vegetation under different sea-level rise scenarios (Albot et al. (2022)) to understand how a coastal wetland is likely to change in the future. A site’s ability to sequester carbon may decrease due to erosion (Figueira and Hayward, 2014), but may also substantially increase as salt marshes are replaced by lower-growing mangroves which store more carbon (Kelleway et al., 2015; Raw et al., 2019; Saintillan et al., 2019). A case-study implementing this approach is present in South Australia, where coastal zones are identified using sea-level rise scenarios, with bans being put in place for the development of these zones, disincentivizing development around their surroundings (workshop participant jtuiy).

4.3.5. Invest in Public Funding for Coastal Wetland Protection

Due to challenges to fulfilling carbon-additionality market requirements, many coastal ecosystem conservation projects may struggle to solicit private capital. Sustaining protection of these healthy wetlands that fall short of additionality requirements is an essential role for governments in order to protect the many ecosystem services/benefits coastal wetlands provide. Planners and policymakers should consider the extent to which different coastal wetlands are suited to market-based mechanisms when allocating funding, ensuring funds are still directed towards areas that are in need of investment, but might not meet carbon or environmental market criteria.

In Indonesia and Malaysia, government-run marine protected areas (MPAs) or terrestrial protected areas have been an effective alternative means of protecting coastal wetlands outside the framework of CMs (Moraes, 2019; Cranshaw & Fox, 2022). Areas where mangroves have been incorporated into MPAs in Indonesia have prevented the loss of an estimated 14,000 ha of mangroves, the equivalent of 13 Mton CO2 (Howard et al., 2017). While MPAs can be managed with extensive IP and LC input, they have been criticised for utilising a top-down approach to management, which can exclude IPs and LCs and negatively impact on their wellbeing (Vierros, 2017; Newell et al., 2019). Women are also typically marginalised and excluded from MPA establishment, management and governance (Anariba et al., 2025). The large size and scope of MPAs also limits the amount of funding that can be specifically diverted to protecting coastal ecosystems (Newell et al., 2019).

Locally managed marine areas (LMMAs) are another existing framework for facilitating benefit distribution, as they are run via a “bottom-up” approach and have been broadly considered to be successful at allocating benefits to local people and ensuring local knowledge is used in environmental management (Vierros, 2017; Moraes, 2019; Newell et al., 2019). LMMAs are more likely to meet additionality requirements to sell carbon credits than MPAs, enabling them to provide more direct benefits to local communities (Moraes, 2019). Since LMMAs (or other types of “other effective area-based conservation measures”/OECMs) often allow for more carbon-intensive subsistence and/or livelihoods activities, there is an opportunity for carbon credits to provide alternative incomes.

Public funding should be directed towards creating enabling conditions, such as those mentioned in previous sections (e.g., awareness programs, mapping tenure, or gender analyses) to increase the investment-readiness of projects which may encourage or improve the effectiveness of private investment in restoration projects. This should be done without de-prioritizing the protection of existing coastal wetlands where CMs are not expected to be a suitable vehicle for investment. To ensure that money is well spent and to maximize success for coastal ecosystem conservation projects, policy makers should require that projects be guided by the best science and local and indigenous knowledge. For example, mangrove restoration projects can establish breakwaters to promote calmer seas and increase the chances of seedling establishment (interviewee lbp2l) and/or research the preferred tidal position and hydropoint tolerances of mangrove and salt-marsh plant species before planting.

4.4. Conflicting Jurisdictions and Priorities Between Agencies

4.4.1. Clarify and Align Political Mandates and Jurisdictions

To simplify blue-carbon project initiation, governments must address and simplify overlapping political mandates, removing jurisdiction-related complications. Resolution of issues where conflicting jurisdictional mandates exist is complicated and location-specific, requiring extensive discussion-based workshops between authorities as well as consultations with stakeholders and IPs and LCs to ensure all challenges are properly resolved.

In PNG, for example, two agencies have overlapping jurisdiction over mangrove restoration (workshop participant 7dd8t). In 2014-2015, TNC organized workshops to facilitate collaboration across the agencies by helping them align their differing and conflicting priorities and develop mangrove policy. Another interviewee from Indonesia noted that the creation of the KKMD (the Regional Mangrove Working Group), coordinating efforts on a provincial level, and the KKMN (the National Mangrove Working Group), coordinating efforts at a national level, have clarified responsibilities for the different aspects of blue-carbon restoration. To offer a long-term solution to the fundamental issue of conflicting institutional mandates and authorities it is important that governments take the effort to create larger-scale institutional change and mandate it at appropriate levels (Bell-James et al., 2023a).

International agreements like the Paris Agreement, can motivate national governments to ensure that different levels of government and authorities over coastal wetlands are brought into alignment. For example, Australia and Vanuatu have incorporated coastal ecosystems into their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) towards meeting targets to avoid +1.5°C warming (Herr et al., 2017; Kelleway et al., 2020; Thuy and Thuy, 2019). Including coastal wetland ecosystems in a NDC carbon accounting framework requires rigorous planning and robust capacities (Hamilton et al., 2020). In order to meet their commitment, a government will need to establish a framework that supports and enables the protection and restoration of coastal wetlands, including through institutional coordination and policy coherence. Additionally, their inclusion into NDCs can signal opportunities for climate finance in support of climate mitigation and/or adaptation.

4.5. Improve Effectiveness of Enforcement

In some places, introducing penalties may help dissuade damaging practices to blue-carbon habitats. However, the presence of a penalty given towards local people without consultation or engagement in regulatory changes will not lead to an equitable outcome. Governments should undertake outreach and engagement programs with local communities living in and near coastal areas, to ensure that community members are engaged in any efforts to strengthen and improve enforcement of regulations, including by introducing penalties for ecologically damaging activities. For example, community-based ranger programs have proven successful in improving biodiversity outcomes from carbon projects in savannas in Northern Australia (ALFA, n.d.; Northern Land Council, 2024). Adaptation of this to approach to coastal wetlands should be explored.

Effective enforcement requires cooperation across levels of government, with each taking on different roles. For example, national governments could establish codes of practice (Bates, 2023) to streamline and standardize the process of restoring and protecting blue-carbon habitats. This can establish a shared understanding and framework for compliance among stakeholders. Local or regional governments, in contrast, may play a larger role in involving and connecting with coastal communities to ensure compliance and alignment. Workshops, such as those discussed in the previous section, can be held between government agencies of different levels as well as traditional/customary institutions to coordinate and delegate enforcement responsibilities. These workshops can be used to develop and align protection strategies, and should involve gender inclusive consultation with practitioners and IPs and LCs to identify and address loopholes without negatively impacting the rights of IPs and LCs or women.

6. Conclusions

This project has identified three common areas of policy challenges where governments across the region should look to address in order to accelerate high-quality blue carbon development in the Asia-Pacific region and to enable coastal ecosystems in the region to meet their full potential as a nature-based solution to climate change, and ensure that outcomes are equitable. These areas include land tenure and ownership issues, funding and protection of coastal wetlands, and conflicting priorities and jurisdictions between organizations responsible for managing coastal wetland habitats. While these issues are complex and challenging, we believe that the recommendations presented in this paper will be valuable to policy makers in closing policy gaps and improving the enabling-conditions for the initiation of blue-carbon projects.

Author Contributions

DJK conducted the SCOPUS search, wrote the literature review, drew all figures, and led the writing of the manuscript. YW, RM, and AL supervised and advised the project. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was internally funded by TNC.

Acknowledgments

Rozaimi Jamaludin (Universiti Kebangsaan), Olya Albot (TNC, Victoria University of Wellington), Aji Anggoro (Yayasan Konservasi Alam Nusantara/YKAN), Topik Hidayat (YKAN), Ruth Konia (TNC), Sophia Bennani-Smires (TNC), Felix Leung (TNC), Prayoto Tonoto (Hiroshima University), Stella Kondylas (TNC), Rick Hamilton (TNC), Justine Bell-James (University of Queensland), Stefanie Simpson (TNC), Stephanie Hedt (TNC), Ed Garrett (University of York), Paul Hudson (University of York), Emily Kelly (World Economic Forum), Mei Zi Tan (Carbon Markets Institute), Janet Hallows (Carbon Market Institute), and Peter Benham (TNC), as well as all anonymized parties, are thanked for their invaluable insight, conversations, and/or comments, which greatly improved the final paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Adame, M.F., Connolly, R.M., Turschwell, M.P., Lovelock, C.E., Fatoyinbo, T., Lagomasino, D., et al. (2021). Future Carbon Emissions from Global Mangrove Forest Loss. Glob. Chang. Biol. 27, 2856–2866. [CrossRef]

- Adityasari, M. (2022). Yayasan Konservasi Alam Nusantara Supports FCPF-Carbon Fund Program in East Kalimantan. https://www.ykan.or.id/en/publications/articles/press-release/ykan-support-fcpf-carbon-fund-program-in-east-kalimantan/ [Accessed April 16, 2024].

- Albot, O., Levy, R., Ratcliffe, J., Naeher, S., Giananne, C., King, D., et al. (2022). The future of Aotearoa New Zealand’s saltmarshes – carbon sequestration and response to sea level rise. Wellington: Victoria University of Wellington.

- Alemu I, J.B., Yaakub, S.M., Yando, E.S., Lau, R.Y.S., Lim, C.C., Puah, J.Y., et al. (2022). Geomorphic gradients in shallow seagrass carbon stocks. Estuar. Coastal and Shelf Science, 265, 107681. [CrossRef]

- ALFA. (n.d). Our Offset Projects. (Arnhem Land Fire Abatement). Available online at: https://www.alfant.com.au/ [Accessed February 6, 2024].

- Alongi, D.M. (2008). Mangrove forests: Resilience, protection from tsunamis, and responses to global climate change. Estuar. Coast. Shelf. Sci. 76(1), 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Ammar, A.A., Dargusch, P., and Shamsudin, I. (2014). Can the Matang Mangrove Forest Reserve provide perfect teething ground for a blue carbon based REDD+ pilot project? J. Trop. For. Sci. 26(3), 371-381. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43150919.

- Anariba, S.E.B., Sanders, A., Canty, S.W.J. (2025). Promoting gender equity in marine protected areas: A self-assessment tool. Mar. Policy. 173, 106526. [CrossRef]

- Arifanti, V.B., Sidik, F., Mulyanto, B., Susilowati, A., Wahyuni, T., Subarno, et al. (2022). Challenges and Strategies for Sustainable Mangrove Management in Indonesia: A Review. For. 13, 695. [CrossRef]

- Armistead, A. (2018). Blue carbon: An effective climate mitigation and drawdown tool? https://www.resilience.org/stories/2018-11-28/blue-carbon-an-effective-climate-mitigation-and-drawdown-tool/ [Accessed October 26, 2023].

- Ayostina, I., Napitupulu, L., Robyn, B., Maharani, C., and Murdiyarso, D. (2022). Network analysis of blue carbon governance process in Indonesia. Mar. Policy. 137, 104955. [CrossRef]

- Aziz, A.A., Thomas, S., Dargusch, P., and Phinn, S. (2016). Assessing the potential of REDD+ in a production mangrove forest in Malaysia using stakeholder analysis and ecosystem services mapping. Mar. Policy. 74, 6-17. [CrossRef]

- Ban, N.C., G.G. Gurney, N.A. Marshall, C.K. Whitney, M. Mills, S. Gelcich, et al. (2019). Well-Being Outcomes of Marine Protected Areas. Nat. Sustain. 2(6), 524–32. [CrossRef]

- Barletti, J.P.S., A.M. Larson, K. Lofts, and Frechette, A. (2021). Safeguards at a Glance: Supporting the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities in REDD+ and Other Forest-Based Initiatives. https://www.cifor.org/publications/pdf_files/Flyer/REDD-safeguards-1.pdf [Accessed November 24, 2023].

- Barletti, J.P.S., N.H. Vigil, E. Garner, and A.M. Larson. (2022). Safeguards at a Glance: Are Voluntary Standards Supporting Gender Equality and Women’s Inclusion in REDD+? https://www.cifor.org/publications/pdf_files/Flyer/REDD-safeguards-5.pdf#:~:text=Ye,s [Accessed October 26, 2023].

- Bates, G. (2023). Proposal for a National Code of Practice for Landscapse Rehydration & Restoration. Bungendore: Mulloon Institute.

- Beeston, M., L. Cuyvers, and Vermilye, J. (2020). Blue Carbon: Mind the Gap. https://gallifrey.foundation/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Blue-Carbon-Mind-the-Gap-V2.2.pdf [Accessed October 27 2023].

- Bell, R, (2021). “How will our coasts and estuaries change with sea-level rise? Implications for communities and infrastructure.” in Climate Aotearoa: What’s Happening & What Can We Do About It?, ed. H. Clark (Auckland: Allen & Unwin), 62-92.

- Bell, R.G., Paulik, R., and Wadwha, S. (2015). National and regional risk exposure in low-lying coastal areas: Areal extent, population, buildings and infrastructure. Hamilton: National Institute of Water & Atmosphere Ltd.

- Bell-James, J. (2020). “Ecosystem-based adaptation in coastal areas: lessons from selected case studies” in Research Handbook on Climate Change, Oceans and Coasts, ed. J. McDonald, J. McGee, and R. Barnes. (Cheltenham: Edward Egar Publishing. pp. 348-365. [CrossRef]

- Bell-James, J. (2023a). From the Silo to the Landscape: The Role of Law in Landscape-scale Restoration of Coastal and Marine Ecosystems. J. Env. Law. 35, 419-436. [CrossRef]

- Bell-James, J. (2023b). Overcoming legal barriers to coastal wetland restoration: lessons from Australia’s Blue Carbon methodology. Restor. Ecol. 31, e13780. [CrossRef]

- Bell-James, J., Foster, R., and Shumway, N. (2023a). The permitting process for marine and coastal restoration: A barrier to achieving global restoration targets?. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 5, e13050. [CrossRef]

- Bell-James, J., Fitzsimmons, J.A., and Lovelock, C.E. (2023b). Land tenure, ownership and use as barriers to coastal wetland restoration projects in Australia: Recommendations and Solutions. Env. Manag. 72, 179-189. [CrossRef]

- Bertram, C., Quaas, M., Reusch, T.B.H., Vafeidis, A.T., Wolff, C., and Rickels, W. (2021). The blue carbon wealth of nations. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 704-709. [CrossRef]

- Bhomia, R.K., MacKenzie, R.A., Murdiyarso, D., Sasmito, S.D., and Purbopuspito, J. (2016). Impacts of land use on Indian mangrove forest carbon stocks: Implications for conservation and management. Ecol. Appl. 26, 1396-1408. [CrossRef]

- Blankespoor, B., Dasgupta, S., and Laplante, B. (2014). Sea-level rise and coastal wetlands. Ambio. 43, 996-1005. [CrossRef]

- Blue Carbon Initiative. (2019). About Blue Carbon. https://www.thebluecarboninitiative.org/about-blue-carbon [Accessed December 13, 2023].

- Bosold, A.L. (2012). Challenging The “Man” In Mangroves: The Missing Role Of Women In Mangrove Conservation. Stud. Publ. 14. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/14/.

- Bouvier, J. (1856). “A Law Dictionary, Adapted to the Constitution and Laws of the United States. Philadelphia: Childs & Peterson” in The Free Dictionary by Farlex: Customary Rights. (Huntindon Valley: Farlex). https://legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Customary+rights [Accessed October 19, 2023].

- Bunting, P., Rosenqvist, A., Lucas, R.M., Rebelo, L.-M., Hlarides, L., Tomas, N., et al. (2018). The Global Mangrove Watch—A New 2010 Global Baseline of Mangrove Extent. Remote. Sens. 10, 1669. [CrossRef]

- Byun, C., Lee, S-H., and Kang, H. (2019). Estimation of carbon storage in coastal wetlands and comparison of different management schemes in South Korea. J. Ecol. Env. 43, 8. [CrossRef]

- Carmondy, E. (2023). Alignment of policies and agencies. Asia Pacific Blue Carbon Workshop (Online Workshop). Day 3, 11:10 am Session.

- Carmody, E. (2024). Restore Blue: Blue Carbon Review of State Laws NSW and QLD. Victoria: The Nature Conservancy.

- Carrasquilla-Henao, M., Ban, N., Rueda, M., and Juanes, F. (2019). The mangrove-fishery relationship: A local ecological knowledge perspective. Mar. Policy. 108, 103656. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S., Saha, S.K., and Selim, S.A. (2020). Recreational services in tourism dominated coastal ecosystems: Bringing the non-economic values into focus. J. Outdoor. Recreat. Tour. 30, 100279. [CrossRef]

- Chanda, A. (2022). “Threats to the Blue Carbon Ecosystems Adjoining the Indian Ocean” in Blue Carbon Dynamics of the Indian Ocean: The Present State of the Art, ed. A. Chanda, S. Das, and T. Ghosh (Dordrecht: Springer), 255-303 pp. [CrossRef]

- Chanda, A., and Akhand, A. (2023). Challenges towards the Sustainability and Enhancement of the Indian Sundarban Mangrove’s Blue Carbon Stock. Life. 13, 8. [CrossRef]

- Chanda, A., and Ghosh, T. (2022). “Blue Carbon Potential of India: The Present State of the Art” in The Blue Economy: An Asian Perspective, ed. S. Hazra, and A. Bhukta (Dordrecht: Springer), 159-180. [CrossRef]

- Chomba, S., Kariuki, J., Lund, J.F., and Sinclair, F. (2016). Roots of inequity: How the implementation of REDD+ reinforces past injustices. Land. Use. Policy. 50, 202-213. [CrossRef]

- Climate Commission. (2024). FAQs: What is the NZ Emissions Trading Scheme (NZ ETS)? https://www.climatecommission.govt.nz/get-involved/exploring-the-issues/what-is-the-nz-ets/#:~:text=Carbon%20credits%3A%20these%20are%20financial,GHG)%20emissions%20in%20the%20atmosphere [Accessed September 9, 2024].

- Cochard, R. (2017). “Coastal Water Pollution and Its Potential Mitigation by Vegetated Wetlands: An Overview of Issues in Southeast Asia” in Redefining Diversity & Dynamics of Natural Resources Management in Asia, Volume 1. Sustainable Natural Resources Management in Dynamic Asia, ed. G.P. Shivakoti, U. Pradham, and Helmi (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 189-230.

- Conservation International, Friends of Ocean Action, World Economic Forum, Ocean Risk and Resilience Action Alliance, Salesforce, The Nature Conservancy, et al. (2022). High-quality blue carbon principles and guidance: A triple benefit investment for people, nature, and climate. Arlington, Stanford, Washington, D.C., San Francisco, Arlington, and Dillon: Conservation International, Friends of Ocean Action, World Economic Forum, Ocean Risk and Resilience Action Alliance, Salesforce, The Nature Conservancy, and Meridian Institute.

- Corcino, R.C.B., Gerona-Daga, M.E.B., Samoza, S.C., Fraga, J.K.R., and Salmo, S.G. (2023). Status, limitations, and challenges of blue carbon studies in the Philippines: A bibliographic analysis. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 62, 102916. [CrossRef]

- Cranshaw, J., and Fox, E. (2022). Potential restoration sites for saltmarsh in a changing climate. Whakatāne: Bay of Plenty Regional Council. 51 p.

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. Univ. Chic. Leg. Forum. 1, 139-167.

- Crosta, N., Sabbion, E., Cachia, F., and Fullbrook, D. (2023). The Big Blue: Supporting Blue Carbon Ecosystems in South-East Asia. The Key Role of Nonprofits and Philanthropy. Zurich: UBS Optimus Foundation and UBS Climate Collective.

- Daiber, F.C. (1986). Conservation of Tidal Marshes. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Ld., 341 p.

- Daming, B., Hongwei, N., Guangchun, L., Hangqing, F., Chengye, L., Fengyi, T., et al. (2020). Report on China Mangrove Conservation and Restoration Strategy Research Project. Executive Summary. Chicago, Hohhot, and Shenzhen: Paulson Institute, Lao Niu Foundation, and Shenzhen Mangrove Wetland Conservation Foundation. 30 p.

- Davidson, N.C., van Dam, A.A., Finlayson, C.M., and McInnes, R.J. (2019). Worth of wetlands: revised global monetary values of coastal and inland wetland ecosystem services. Mar. Freshw. Res. 70, 1189-1194. [CrossRef]

- Dencer-Brown, A.M., Shilland, R., Friess, D., Herr, D., Benson, L., Berry, N.J., et al. (2022). Integrating blue: how do we make nationally determined contributions work for both blue carbon and local coastal communities? Ambio. 51, 1978-1993. [CrossRef]

- Denya, K., and Peters, M. (2020). The root causes of wetland loss in New Zealand: An analysis of public policies & processes. Pukekohe: National Wetland Trust.

- Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW). (2022). Emissions Reduction Fund to Credit Blue Carbon Projects. https://www.dcceew.gov.au/about/news/emissions-reduction-fund-to-credit-blue-carbon-projects [Accessed October 26, 2023].

- DCCEEW. (2023). Nature Repair Market. https://www.dcceew.gov.au/environment/environmental-markets/nature-repair-market [Accessed February 21, 2024].

- DCCEEW. (2025). Carbon Accellerator Fund. https://www.dcceew.gov.au/environment/marine/coastal-blue-carbon-ecosystems/conservation/accelerator-fund [Accessed February 25, 2025].

- Department of Fisheries (Dept. Fisheries). (2012). Fisheries Fact Sheet: Mangroves: Mangroves of the West. https://www.fish.wa.gov.au/Documents/recreational_fishing/fact_sheets/fact_sheet_mangroves.pdf [Accessed December 14, 2023].

- Everard, M. (2014). “Food from Wetlands” in The Wetland Book, ed. C.M. Finlayson, M. Everard, K. Irvine, R.J. McInnes, B.A. Middleton, A.A. van Dam, N.C., et al. (Dordrecht: Springer), 1-3. [CrossRef]

- Figueira, B., and Hayward, B.W. (2014). Impact of reworked foraminifera from an eroding salt marsh on sea-level studies, New Zealand. N. Z. J. Geol. Geophys. 57, 378-389. [CrossRef]

- Flores, R.C., Corpus, M.N.C., and Salas, J.M. (2016). Adoption of aquasilviculture technology: A positive approach for sustainable fisheries and mangrove wetland rehabilitation in Bataan, Philippines. Int. J. Food. Eng. 2, 79-83. [CrossRef]

- Fortes, M., Griffiths, L., Collier, C., Mtwana Nordlund, L., de la Torre-Castro, M., Vanderklift, et al. (2020). “Policy and Management Options” in Out of the Blue: The Value of Seagrasses to the Environment and to People, eds. M. Potouroglou, G. Grimsditch, L. Weatherdon, L., and S. Lutz (Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme), 62-69.

- Friess, D.A., Thompson, B.S., Brown, B., Amir, A.A., Cameron, C., Koldewey, et al. (2016). Policy Challenges and Approaches for the Conservation of Mangrove Forests in Southeast Asia. Conserv. Biol. 30, 933–49. [CrossRef]

- Friess D.A., Yondo, E.S., Alemu, J.B., Wong, L.-W., and Soto, S.D. (2020). Ecosystem services and disservices of mangroves and salt marshes. Ocean. Mar. Biol. Ann. Rev. 58, 107-172.

- Friess, D.A., Howard, J. Huxham, M., Macreadie, P.I., and Ross, F. (2022). Capitalizing on the Global Financial Interest in Blue Carbon. PLOS Clim. 1, e0000061. [CrossRef]

- Genua-Olmedo, A., Alcaraz, C., Caiola, N., and Ibáñez, C. (2016). Sea level rise impacts on rice production: The Ebro Delta as an example. Sci. Total. Env. 571, 1200-1210. [CrossRef]

- Gevaña, D.T., Camacho, L.D., and Pulhin, J.M. (2018). Conserving mangroves for their blue carbon: Insights and prospects for community-based mangrove management in southeast Asia. Coast. Res. Libr. 25, 579-588. [CrossRef]

- Giangola, L., Self, R., Stiles, M., Gallagher, K., and Kupchik, M. (2023). The Importance and Impact of Blue Carbon in the Indo-Pacific. Washington, D.C.: United States Agency for International Development.

- GIGACalculator. (2023). Random Alphanumeric Generator. https://www.gigacalculator.com/randomizers/random-alphanumeric-generator.php [Accessed December 7, 2023].

- Griffith Asia Institute. (2019). Mangoro market meri: Women guardians of mangroves in PNG. https://blogs.griffith.edu.au/asiainsights/perspectivesasia-mangoro-market-meri-women-guardians-of-the-mangroves-in-png/ [Accessed May 30, 2024].

- Gu, J., Luo, M., Zhang, X., Christakos, G., Agusti, S., Duarte, C.M., et al. (2018). Losses of salt marsh in China: Trends, threats and management. Estuar. Coast. Shelf. Sci. 214, 98-109. [CrossRef]

- Hair, C., Mills, D.J., McIntyre, R., and Southgate, P.C. (2016). Optimising methods for community-based sea cucumber ranching: Experimental releases of cultured juvenile Holothuria scabra into seagrass meadows in Papua New Guinea. Aquac. Rep. 3, 198-208. [CrossRef]

- Hair, C., Militz, T.A., Daniels, N., and Southgate, P.C. (2022). Performance of a trial sea ranch for the commercial sea cucumber, Holothuria scabra, in Papua New Guinea. Aquac. 547, 737500. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J., Kasprzyk, K., Cifuentez-Jara, M., Granziera, B., Gil, L., Wolf, S., et al. (2020). Blue Carbon and Nationally Determined Contributions Second Edition: Guidelines on Enhanced Action. International: The Blue Carbon Initiative.

- Hamilton, R. J., Almany, G. R., Brown, C. J., Pita, J., Peterson, N. A., & Choat, J. H. (2017). Logging degrades nursery habitat for an iconic coral reef fish. Biol. Conserv. 210, 273-280. [CrossRef]

- Hamrick, K., Myers, K., and Soewilo, A. (2023). Beyond Beneficiaries: Fairer Carbon Market Frameworks. Arlington: The Nature Conservancy.

- Hangqing, F. (2021). Mangroves at the Intersection of Ecological Protection and Targeted Poverty Alleviation. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. http://www.bcas.cas.cn/infocus/202111/t20211124_293056.html [Accessed November 2, 2023].

- Hansen, J.D., and Reiss, K.C. (2015). “Threats to marsh resources and mitigation” in Coastal and Marine Hazards, Risks, and Disasters, ed. J.F. Shroder, J.T. Ellis, and D.J. Sherman (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 467-494. [CrossRef]

- Hauer, M.E., Fussell, E., Mueller, V., Burkett, M., Call, M., McLeman, R., and Wrathall, D. (2020). Sea-level rise and human migration. Nat. Rev. Earth. Env. 1, 28-39. [CrossRef]

- Hawes, R. (2023). Project Salt Marsh: South Atlantic Salt Marsh Initiative. https://www.coastalconservationleague.org/projects/salt-marsh/ [Accessed December 13, 2023].

- Hayman, T. (2023). Restoring Mangrove Forests in Papua New Guinea. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qu-G4_y0uQE [Accessed February 21, 2024].

- Hejnowicz, A.P., Kennedy, H., Rudd, M.A., and Huxham, M.R. (2015). Harnessing the climate mitigation, conservation and poverty alleviation potential of seagrasses: Prospects for developing blue carbon initiatives and payment for ecosystem service programmes. Front. Mar. Sci. 2, 32. [CrossRef]

- Herr, D., M. von Unger, D. Laffoley, and A. McGivern. (2017). Pathways for Implementation of Blue Carbon Initiatives. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 27 (S1), 116–129. [CrossRef]

- Hoegh-Guldberg, O., Caldeira, K., Chopin, T., Gaines, S., Haugan, P., Hemer, M., et al. (2019). The Ocean as a Solution to Climate Change: Five Opportunities for Action. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute.

- Howard, J., McLeod, E., Thomas, S., Eastwood, E., Fox, M., Wenzel, L., and Pidgeon, E. (2017). The potential to integrate blue carbon into MPA design and management. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 27 (S1), 100-115. https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.2809. Howard, J., Sutton-Grier, A.E., Smart, L.S., Lopes, C.C., Hamilton, J., Kleypas, J., et al. (2023). Blue carbon pathways for climate mitigation: Known, emerging and unlikely. Mar. Policy. 156, 105788. [CrossRef]

- Huggins, C. (2012). Defining Customary Land Rights. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/20080609_property_Huggins.pdf [Accessed October 19, 2023].

- Huxham, M., Brown, C.J., Unsworth, R.K.F., Stankovic, M., and Vanderklift, M. (2020). “Financial Incentives”. in Out of the Blue: The Value of Seagrasses to the Environment and to People, ed. M. Potouroglou, G. Grimsditch, L. Weatherdon, and S. Lutz (Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme), 73-80.

- International Partnership for Blue Carbon (IPBC). (2015). Coastal blue carbon: An Introduction for Policy Makers. Paris: International Partnership for Blue Carbon.