Submitted:

16 July 2024

Posted:

17 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Anthocyanin Extraction, Quantification and Characterization from the Different Extracts

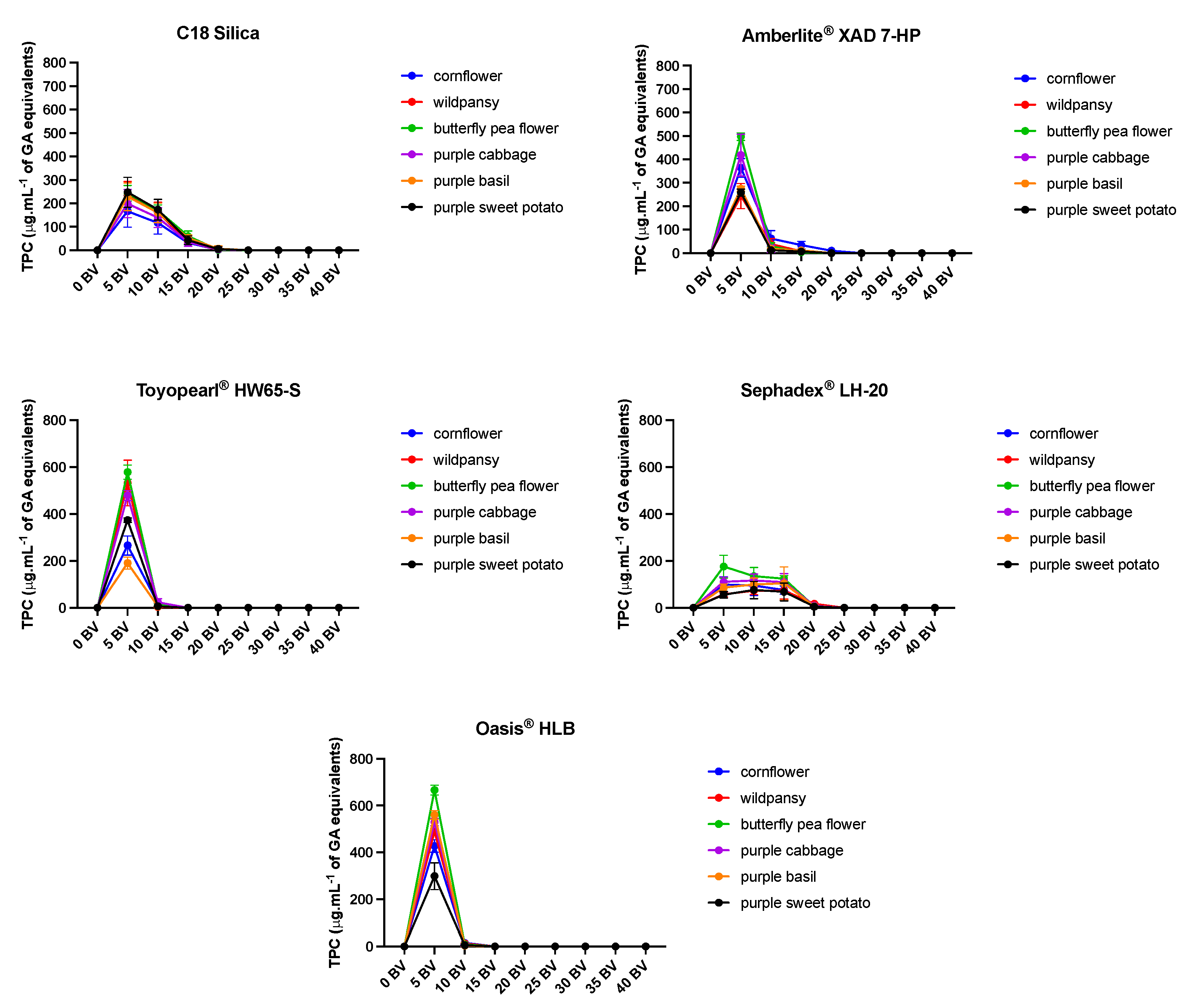

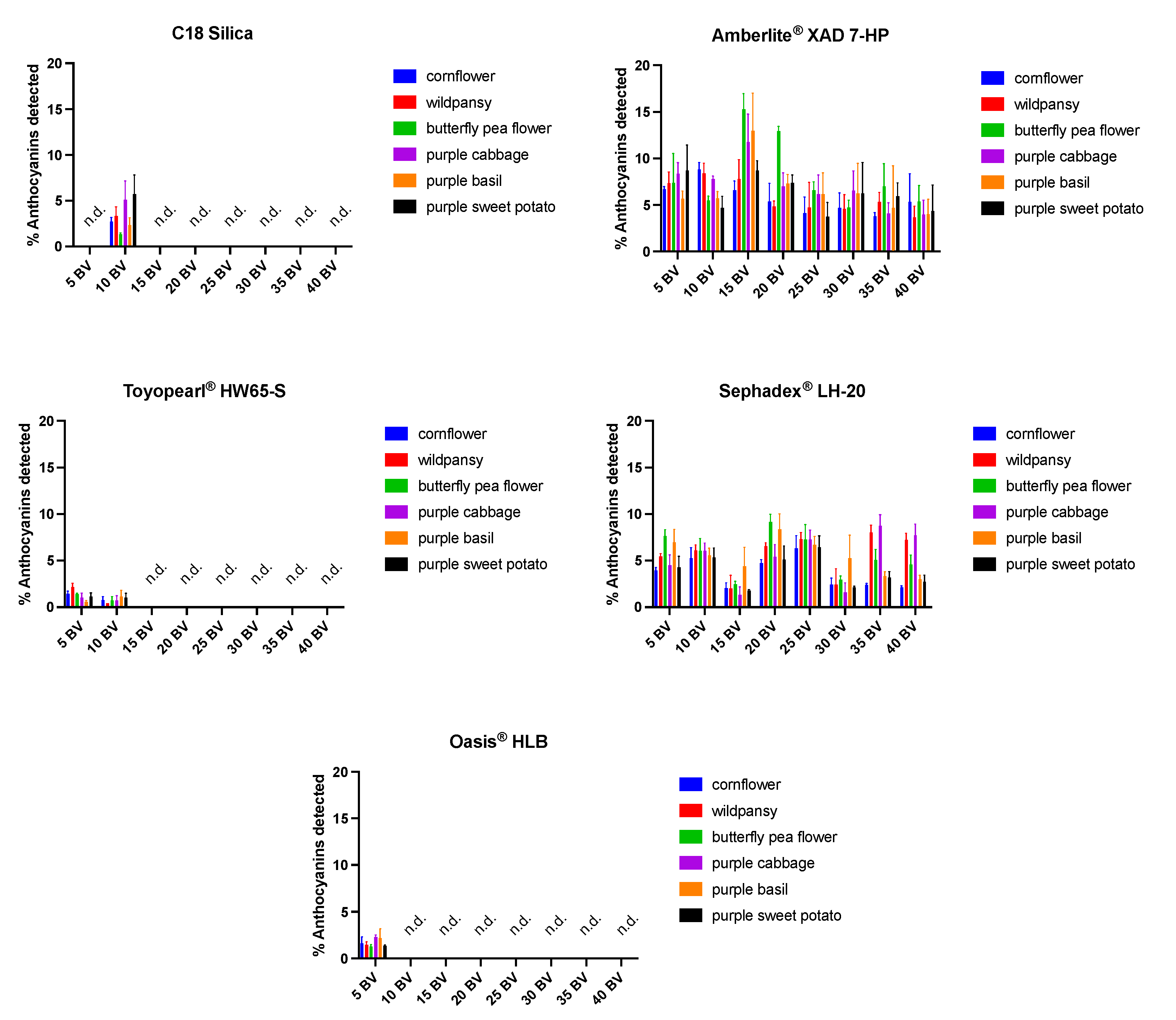

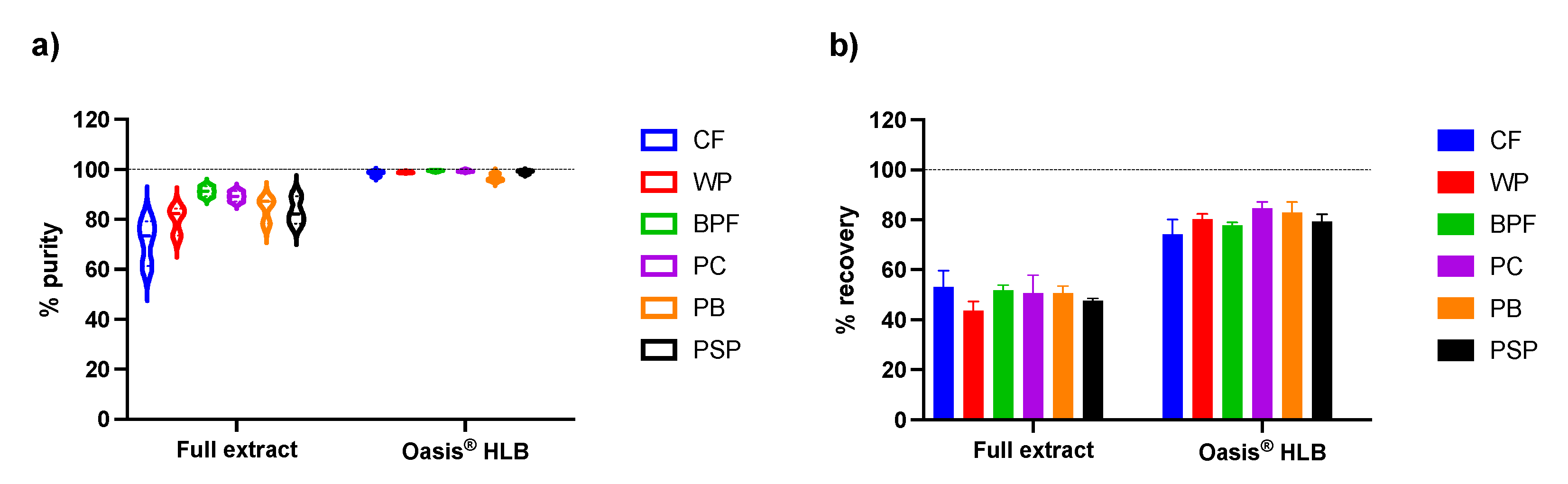

2.2. Anthocyanins Purification Strategies with the Different SPE

2.2.1. Non-Anthocyanin Fraction Removal with Ethyl Acetate

2.2.2. Effect of Acidic Water Application in the Resins

2.2.3. Recovery and Purity of Anthocyanins with Acidic Methanol

2.3. Cation-Exchange Chromatography with Discovery® DSC-MCAX

3. Conclusion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Samples Preparation

4.1.1. Edible Flowers

4.1.2. Purple Basil (Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens), Purple Cabbage (Brassica oleracea) and Purple Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas L.)

4.2. Solid-Phase Extractions Resins

4.2.1. C-18 Silica Resin

- 40 BV of ethyl acetate.

- 40 BV of deionized water with 1% HCl 1M.

4.2.2. Amberlite® XAD 7-HP Resin

- 40 BV of ethyl acetate.

- 40 BV of deionized water with 1% HCl 1M.

4.2.3. Toyopearl® HW65-S Resin

- 40 BV of ethyl acetate.

- 40 BV of deionized water with 1% HCl 1M.

4.2.4. Sephadex® LH-20 Resin

- 40 BV of ethyl acetate.

- 40 BV of deionized water with 1% HCl 1M.

4.2.5. Oasis® HLB Resin

- 40 BV of ethyl acetate.

- 40 BV of deionized water with 1% HCl 1M

4.3. Cation-Exchange Extraction

4.4. UHPLC-DAD Analysis

4.5. HPLC-DAD-ESI-MS Analysis

4.5. Quantification of Anthocyanins

4.6. Total Polyphenol Content

4.7. Bed Volumes (BV) Definition

4.8. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mannino, G., et al. Anthocyanins: Biosynthesis, Distribution, Ecological Role, and Use of Biostimulants to Increase Their Content in Plant Foods—A Review. Agriculture, 2021. 11. [CrossRef]

- Krga, I. and D. Milenkovic, Anthocyanins: from sources and bioavailability to cardiovascular-health benefits and molecular mechanisms of action. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2019. 67 (7): p. 1771-1783. [CrossRef]

- Khoo, H.E., et al., Anthocyanidins and anthocyanins: colored pigments as food, pharmaceutical ingredients, and the potential health benefits. Food & Nutrition Research, 2017. 61(1): p. 1361779. [CrossRef]

- Tan, J., et al., Extraction and purification of anthocyanins: A review. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 2022. 8: p. 100306.

- Nunes, A.N., et al. Alternative Extraction and Downstream Purification Processes for Anthocyanins. Molecules, 2022. 27. [CrossRef]

- He, S., et al., Water Extraction of Anthocyanins from Black Rice and Purification Using Membrane Separation and Resin Adsorption. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation, 2017. 41(4): p. e13091. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., et al., Adsorption properties of macroporous adsorbent resins for separation of anthocyanins from mulberry. Food Chemistry, 2016. 194: p. 712-722.

- Xue, H., et al., Isolation and Purification of Anthocyanin from Blueberry Using Macroporous Resin Combined Sephadex LH-20 Techniques. Food Science and Technology Research, 2019. 25(1): p. 29-38.

- Mateus, N., et al., A New Class of Blue Anthocyanin-Derived Pigments Isolated from Red Wines. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2003. 51(7): p. 1919-1923.

- Ferreiro-González, M., et al., A New Solid Phase Extraction for the Determination of Anthocyanins in Grapes. Molecules, 2014. 19(12): p. 21398-21410.

- Liao, Z., et al., Recovery of value-added anthocyanins from mulberry by a cation exchange chromatography. Current Research in Food Science, 2022. 5: p. 1445-1451.

- He, J. and M.M. Giusti, High-purity isolation of anthocyanins mixtures from fruits and vegetables – A novel solid-phase extraction method using mixed mode cation-exchange chromatography. Journal of Chromatography A, 2011. 1218(44): p. 7914-7922.

- Shah, N.M. and J.M. Chapman, Rapid Separation of Anthocyanins and Flavonol Glycosides Utilising Discovery DSC-MCAX Solid Phase Extraction. Analyti X, 2009. 9.

- Tena, N. and A.G. Asuero, Up-To-Date Analysis of the Extraction Methods for Anthocyanins: Principles of the Techniques, Optimization, Technical Progress, and Industrial Application. Antioxidants (Basel), 2022. 11(2).

- Paludo, M.C., et al., Optimizing the extraction of anthocyanins from the skin and phenolic compounds from the seed of jabuticaba fruits (Myrciaria jabuticaba (Vell.) O. Berg) with ternary mixture experimental designs. Journal of the Brazilian Chemical Society, 2019. 30(7): p. 1506-1515.

- Albuquerque, B.R., et al., Anthocyanin-rich extract of jabuticaba epicarp as a natural colorant: Optimization of heat- and ultrasound-assisted extractions and application in a bakery product. Food Chemistry, 2020. 316.

- Xu, D.P., et al., Natural Antioxidants in Foods and Medicinal Plants: Extraction, Assessment and Resources. Int J Mol Sci, 2017. 18(1).

- Pina, F., J. Oliveira, and V. de Freitas, Anthocyanins and derivatives are more than flavylium cations. Tetrahedron, 2015. 71(20): p. 14.

- He, J., et al., Dietary polyglycosylated anthocyanins, the smart option? A comprehensive review on their health benefits and technological applications. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 2022. 21(4): p. 3096-3128.

- Handayani, L., et al., Identification of the anthocyanin profile from butterfly pea (Clitoria ternatea L.) flowers under varying extraction conditions: Evaluating its potential as a natural blue food colorant and its application as a colorimetric indicator. South African Journal of Chemical Engineering, 2024. 49: p. 151-161.

- Teixeira, M., et al., Anthocyanin-rich edible flowers, current understanding of a potential new trend in dietary patterns. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 2023. 138: p. 708-725.

- Tan, S., et al., Physical character, total polyphenols, anthocyanin profile and antioxidant activity of red cabbage as affected by five processing methods. Food Research International, 2023. 169: p. 112929.

- Rodríguez-Mena, A., et al., Coloring potential of anthocyanins from purple sweet potato paste: Ultrasound-assisted extraction, enzymatic activity, color and its application in ice pops. Food Chemistry Advances, 2023. 3: p. 100358.

- da Silva, R.F.R., et al., Anthocyanin Profile of Elderberry Juice: A Natural-Based Bioactive Colouring Ingredient with Potential Food Application. Molecules, 2019. 24(13).

- Denev, P., et al., Solid-phase extraction of berries’ anthocyanins and evaluation of their antioxidative properties. Food Chemistry, 2010. 123(4): p. 1055-1061.

- Huopalahti, R., E.P. Järvenpää, and K. Katina, A NOVEL SOLID-PHASE EXTRACTION-HPLC METHOD FOR THE ANALYSIS OF ANTHOCYANIN AND ORGANIC ACID COMPOSITION OF FINNISH CRANBERRY. Journal of Liquid Chromatography & Related Technologies, 2000. 23(17): p. 2695-2701.

- Westfall, A., et al., Ex Vivo and In Vivo Assessment of the Penetration of Topically Applied Anthocyanins Utilizing ATR-FTIR/PLS Regression Models and HPLC-PDA-MS. Antioxidants (Basel), 2020. 9(6).

- Pérez-Magariño, S., M. Ortega-Heras, and E. Cano-Mozo, Optimization of a Solid-Phase Extraction Method Using Copolymer Sorbents for Isolation of Phenolic Compounds in Red Wines and Quantification by HPLC. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2008. 56(24): p. 11560-11570.

- Trikas, E.D., et al., Evaluation of Ion Exchange and Sorbing Materials for Their Adsorption/Desorption Performane towards Anthocyanins, Total Phenolics, and Sugars from a Grape Pomace Extract. Separations, 2017. 4(1): p. 9.

- Teixeira, M., et al. First Insights on the Bioaccessibility and Absorption of Anthocyanins from Edible Flowers: Wild Pansy, Cosmos, and Cornflower. Pharmaceuticals, 2024. 17. [CrossRef]

| Extract1 | Total Anthocyanin Content (mg.g-1 DW of extract) |

|---|---|

| cornflower | 67,4 ± 1,2 |

| wild pansy | 43,5 ± 2,3 |

| butterfly pea flower | 172,4 ± 4,3 |

| purple cabbage | 274,3 ± 2,1 |

| purple basil | 72,4 ± 1,4 |

| purple sweet potato | 87,3 ± 5,3 |

| Extract | Rt (min) | [M+H]+ (m/z) | Main fragment ions | λmax (nm) | Tentative identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cornflower | 8.20 | 611.39 | 449.26, 287.14 | 276, 512 | Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside-5-O-glucoside |

| 9.49 | 697.4 | 535.3, 449.49, 287.36 | 280, 512 | Cyanidin-3-(6-malonyl)-O-glucoside-5-O-glucoside | |

| 10.21 | 711.39 | 549.35, 449.5, 287.15 | 280, 516 | Cyanidin-3-(6-succinyl)-O-glucoside-5-O-glucoside | |

| 13.00 | 725.38 | 563.36, 449.5, 287.15 | 276, 516 | Cyanidin derivative | |

| 15.68 | 549.41 | 287.18 | 280, 516 | Cyanidin-3-(6-succinyl)-O-glucoside | |

| wild pansy | 7.50 | 773.38 | 611.34, 465.31, 303.18 | 276, 520 | Delphinidin-3-O-rutinoside-5-O-glucoside |

| 14.83 | 919.41 | 757.47, 465.47, 303.17 | 284, 528 | Delphinidin-3-(4″-p-coumaroyl)-O-rutinoside-5-O-glucoside | |

| 17.22 | 903.4 | 741.37, 449.3, 287.15 | 292, 524 | Cyanidin-3-(4′-cis-p-coumaroyl)-O-rutinoside-5-O-glucoside | |

| 20.01 | 757.42 | 611.3, 465.2, 303.15 | 284, 532 | Delphinidin-3-(4′-cis-p-coumaroyl)-O-rutinoside | |

| butterfly pea flower | 10.03 | 1183.37 | 935.47, 773.43, 611.44, 465.36, 303.19 | 184, 528 | ternatin C4 |

| 10.16 | 1405.44 | 1243.6, 1081.61, 935.46, 773.53 | 288, 536 | preternatin A3 | |

| 10.67 | 1491.36 | 1405.73, 1243.68 | 288, 540 | Ternatin C2 | |

| 12.5 | 1243.41 | 1081.48, 919.42, 773.46, 611.34, 465.36, 303.22 | 288, 540 | Delphinidin-3-O-glucoside-3′-(6-p-coumaroyl)-O-glucoside-5′- (6-p-coumaroyl)-O-diglucoside | |

| 13.4 | 1329.37 | 1081.56, 919.6, 773.56, 611.53, 465.4, 303.24 | 288, 540 | Ternatin B4 | |

| 15.06 | 1405.33 | 288, 540 | preternatin A3 | ||

| 15.38 | 1799.36 | 1713.7 | 290, 548 | Ternatin A2 | |

| 16.6 | 1343.37 | 1243.61, 1081.54, 919.60, 773.55, 611.42, | 288, 540 | Delphinidin-3-(6-succinyl)-O-glucoside-3′-(6-p-coumaroyl)-O-glucoside-5′- (6-p-coumaroyl)-O-diglucoside | |

| 16.73 | 1343.39 | 1081.49, 919.59, 773.55, 611.45, 465.32 | 288, 540 | Delphinidin-3-(6-succinyl)-O-glucoside-3′-(6-p-coumaroyl)-O-glucoside-5′- (6-p-coumaroyl)-O-diglucoside | |

| 17.05 | 1035.34 | 873.48, 773.42, 611.34, 465.35, 303.17 | 288, 540 | Delphinidin-3-O-glucoside-3′-(6-succinyl))-O-glucoside-5′- (6-p-coumaroyl)-O-glucoside | |

| 17.58 | 1637.34 | 1551.61, 1389.68 | 288, 548 | Ternatin B3 | |

| 18.19 | 1813.32 | 1713.64, 1551.87, | 288, 548 | N. D | |

| ·22.34 | 1637.34 | 1389.7 | 296, 548 | Ternatin B2 | |

| 23.16 | 1945.39 | 292, 552 | Ternatin B1 | ||

| 25.43 | 1475.31 | 1389.67, 1227.65, 919.67 | 292, 548 | Ternatin D2 | |

| 31.72 | 1783.36 | 1697.68, 1535.61 | 292, 552 | Ternatin D1 | |

| purple cabbage | 8.18 | 773.37 | 280, 516 | Cyanidin-3-O-diglucoside-5-glucoside | |

| 9.63 | 1141.39 | 979.42 | 280, 332, 528 | Cyanidin-3-(6-sinapoyl)-O-triglucoside-5-O-glucoside | |

| 12.21 | 1081.35 | 919.44, 757.52, 449.36, 287.13 | 280, 520 | Cyanidin-3-(6-p-coumaroyl)-O-triglucoside-5-O-glucoside | |

| 12.66 | 1111.38 | 949.44, 787.5, 611.5, 449.27, 287.12 | 280, 524 | Cyanidin-3-(6-feruloyl)-O-triglucoside-5-O-glucoside | |

| 15.6 | 1287.32 | 1125.5, 963.46, 449.29 | 288, 532 | Cyanidin-3-(6,6′-diferuloyl)-O-triglucoside-5-O-glucoside | |

| 16.23 | 1317.39 | 1155.5, 993.51, 611.35, 449.35 | 288, 324, 536 | Cyanidin-3-(6-feruloyl)(6′-sinapoyl)-O-triglucoside-5-O-glucoside | |

| 19.03 | 919.38 | 757.58, 595.44, 449.33, 287.12 | 280, 312, 520 | Cyanidin-3-(6-p-coumaroyl)-O-diglucoside-5-O-glucoside | |

| 19.6 | 979.37 | 817.41, 655.55, 449.29, 287.15 | 280, 324, 520 | Cyanidin-3-(6-sinapoyl)-O-diglucoside-5-O-glucoside | |

| 21.1 | 817.34 | 284, 328, 524 | Cyanidin-3-(6-sinapoyl)-O-glucoside-5-glucoside | ||

| 23.46 | 1125.35 | 963.42, 757.61, 595.56, 449.3, 287.13 | 296, 320, 532 | Cyanidin-3-(6-sinapoyl)(6′-p-coumaroyl)-O-diglucoside-5-O-glucoside | |

| 24.32 | 1155.32 | 993.43, 787.69, 449.36, 287.12 | 296, 328, 532 | Cyanidin-3-(6-feruloyl)(6′-sinapoyl)-O-diglucoside-5-O-glucoside | |

| 24.99 | 1185.36 | 1023.43, 817.49, 449.34, 287.12 | 300, 332, 532 | Cyanidin-3-(6,6′-sinapoyl)-O-diglucoside-5-O-glucoside | |

| purple basil | 11.04 | 919.36 | 757.43, 595.48, 449.4, 287.14 | 280, 524 | Cyanidin-3-(6-p-coumaroyl)(6‘-caffeoyl)-O-diglucoside isomer 1 |

| 12.44 | 919.37 | 757.48, 595.57, 449.47, 287.15 | 280, 520 | Cyanidin-3-(6-p-coumaroyl)(6‘-caffeoyl)-O-diglucoside isomer 2 | |

| 19.15 | 1081.32 | 919.43, 757.57, 595.46, 449.3, 287.13 | 284, 524 | Cyanidin-3-(6-p-coumaroyl)(6‘-caffeoyl)-O-diglucoside-5-O-glucoside isomer 1 | |

| 19.72 | 757.28 | 595.34, 449.38, 287.14 | 284, 520 | Cyanidin-3-(6-p-coumaroyl)-O-glucoside-5-O-glucoside | |

| 21.90 | 1081.34 | 919.4, 757.5, 595.46, 449.33, 287.14 | 288, 524 | Cyanidin-3-(6-p-coumaroyl)(6‘-caffeoyl)-O-diglucoside-5-O-glucoside isomer 2 | |

| 24.24 | 1065.41 | 903.44, 757.53, 595.47, 449.38, 287.14 | 284, 528 | Cyanidin-3-(6,6′-dip-coumaroyl)-O-diglucoside-5-O-glucoside isomer 1 | |

| 29.16 | 1065.37 | 903.54, 757.6, 595.49, 449.4, 287.14 | 284, 528 | Cyanidin-3-(6,6′-dip-coumaroyl)-O-diglucoside-5-O-glucoside isomer 2 | |

| purple sweet potato | 8.61 | 787.36 | 524 | Peonidin-3-O-diglucoside-5-O-glucoside | |

| 11.47 | 907.35 | 745.36, 463.29, 301.25 | 274, 520 | Peonidin-3-(6-p-hydroxybenzoyl)-O-diglucoside-5-O-glucoside | |

| 11.88 | 1067.39 | 905.4, 887.58, 605.55 | 273, 532 | Peonidin derivative isomer 1 | |

| 12.32 | 1097.35 | 935.43 | 532 | Cyanidin-3-(6,6′-dicaffeoyl)-O-diglucoside-5-glucoside | |

| 13.05 | 1067.35 | 905.46, 887.55, 605.45 | 273, 532 | Peonidin derivative isomer 2 |

| Resin | TAC (%) after 40 BV | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CF1 | WP1 | BPF1 | PC1 | PB1 | PSP1 | ||

| C18 Silica | 2.5 ± 0.9# | 5.1 ± 0.73-5 | 7.7 ± 2.3 | 4.2 ± 0.4$ | 5.8 ± 0.5 | 8.8 ± 0.3a,b,d,e,,$ | |

| Amberlite® XAD 7-HP | 3.4 ± 0.3b,c,e | 5.8 ± 1.13-5 | 6.6 ± 1.2 | 1.7 ± 0.7$ | 4.2 ± 1.2 | 3.0 ± 0.5$ | |

| Toyopearl® HW-65S | 1.1 ± 0.4b,d,e | 2.4 ± 0.3$ | 1.5 ± 0.5$ | n.d.#,1,2,4 | 2.2 ± 0.91,2,4 | 0.8 ± 0.71,2,4 | |

| Sephadex® LH-20 | 7.8 ± 1.2d,$ | 11.4 ± 0.5#,$ | 7.2 ± 0.7 | 9.4 ± 0.3$ | 5.7 ± 0.7 | 6.4 ± 0.8$ | |

| Oasis® HLB | n.d.e-f,$ | n.d. e-f,$ | n.d. e-f,$ | n.d. e-f,1,2,4 | 1.3 ± 0.4a-d,1,2,4 | 1.0 ± 0.2 a-d | |

| Resin | Anthocyanin Recovery (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CF1 | WP1 | BPF1 | PC1 | PB1 | PSP1 | |

| C18 Silica | 72.6 ± 6.4c,2,3 | 62.3 ± 5.2 | 77.3 ± 10.4d,2,3,4 | 46.1 ± 1.7e,f,5 | 75.4 ± 2.52 | 76.7 ± 9.34 |

| Amberlite® XAD 7-HP | 49.1 ± 7.85 | 50.9 ± 6.83,5 | 33.2 ± 9.4d,f,3,5 | 58.1 ± 4.33,5 | 48.1 ± 15.84,5 | 67.5 ± 1.8 |

| Toyopearl® HW-65S | 48.0 ± 11.9b,5 | 73.9 ± 5.9d | 57.9 ± 4.0d,4,5 | 34.4 ± 8.9e,f,5 | 63.1 ± 15.75 | 59.9 ± 16.85 |

| Sephadex® LH-20 | 63.4 ± 14.5c,5 | 62.3 ± 13.1c | 37.0 ± 4.6e,5 | 45.0 ± 2.5e,5 | 68.4 ± 11.25 | 56.7 ± 8.95 |

| Oasis® HLB | 83.9 ± 4.9 | 79.9 ± 10.1 | 81.2 ± 4.3 | 91.6 ± 2.6 | 89.8 ± 2.2 | 85.9 ± 1.5 |

| Anthocyanin Purity (%) | ||||||

| CF1 | WP1 | BPF1 | PC1 | PB1 | PSP1 | |

| C18 Silica | 36.4 ± 1.9b,c,e,f,$ | 48.0 ± 3.0d,$ | 48.0 ± 1.4d,3,4,5 | 31.9 ± 1.2e,f,3,5 | 54.5 ± 2.24,5 | 57.1 ± 6.34,5 |

| Amberlite® XAD 7-HP | 47.3 ± 2.5d,f,$ | 38.6 ± 4.3c,e,f,$ | 38.6 ± 3.63,4,5 | 29.3 ± 0.9e,f,3,5 | 52.3 ± 2.73,4,5 | 58.9 ± 6.34,5 |

| Toyopearl® HW-65S | 66.4 ± 6.14 | 67.5 ± 2.44 | 67.5 ± 3.94,5 | 62.5 ± 4.34 | 62.2 ± 4.54,5 | 62.6 ± 2.74,5 |

| Sephadex® LH-20 | 15.3 ± 7.1#,5 | 29.0 ± 7.3d,5 | 29.0 ± 2.15 | 33.2 ± 2.15 | 39.8 ± 5.55 | 37.4 ± 2.15 |

| Oasis® HLB | 68.9 ± 4.7c | 72.4 ± 4.4d | 72.4 ± 3.5d | 61.6 ± 1.5e,f | 72.2 ± 2.1 | 74.9 ± 2.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).