Submitted:

23 October 2025

Posted:

24 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Extraction Yield of Anthocyanins

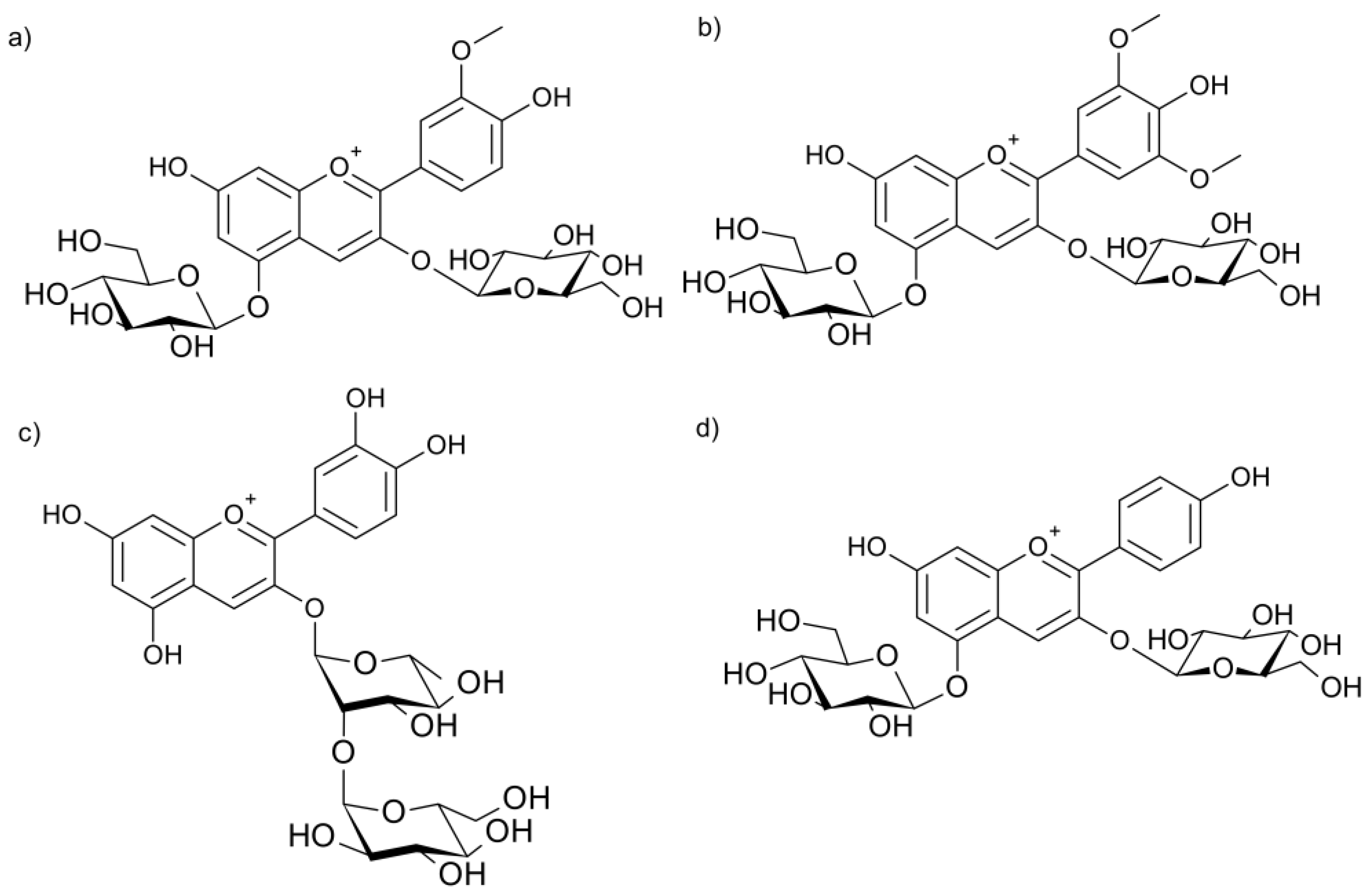

2.2. Chromatographic Characterization of Anthocyanins and Anthocyanidins

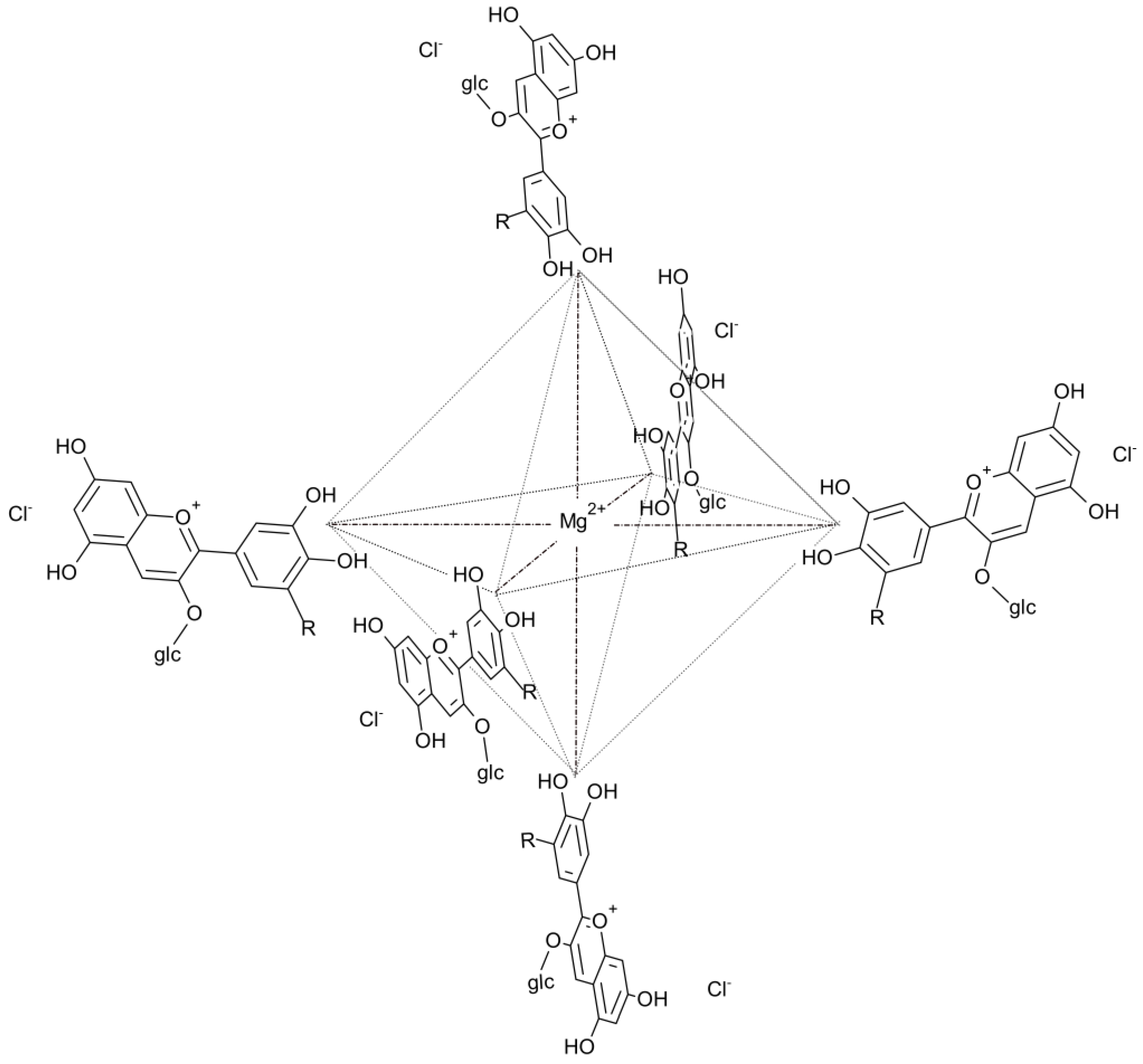

2.3. Formation and Characteristics of the Magnesium-Anthocyanin Complex

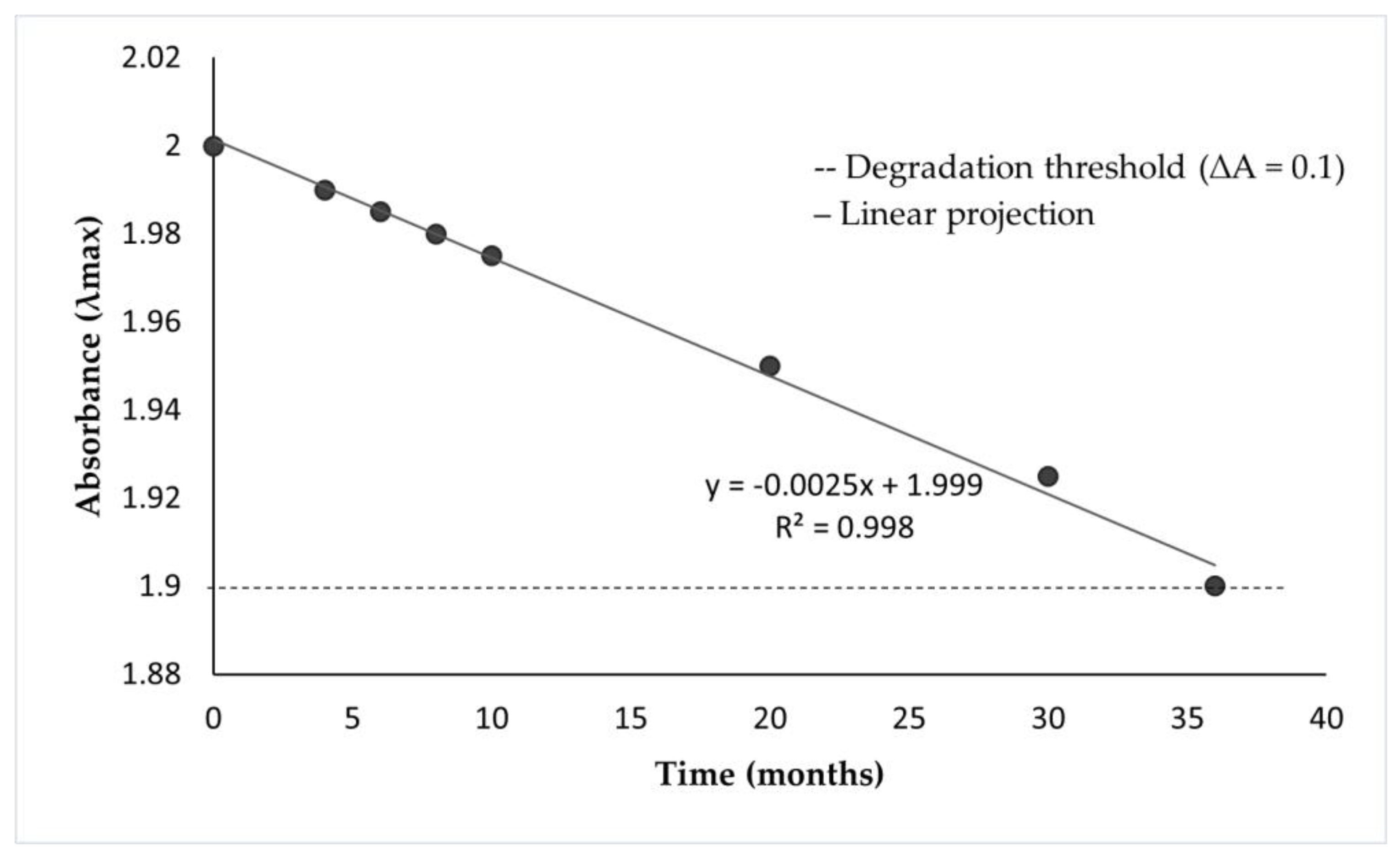

2.4. Spectrophotometric Stability and Shelf-Life Projection

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents and Equipment

4.2. Plant Material and Sample Collection

4.3. Extraction and Concentration of Anthocyanins

4.4. Paper Chromatography and Identification of Anthocyanins and Anthocyanidins

4.5. Stabilization and Spectrophotometric Evaluation of the Magnesium Complex

4.6. Ethical and Environmental Considerations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kong, J.-M.; Chia, L.-S.; Goh, N.-K.; Chia, T.-F.; Brouillard, R. Analysis and Biological Activities of Anthocyanins. Phytochemistry 2003, 64, 923–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, H.E.; Azlan, A.; Tang, S.T.; Lim, S.M. Anthocyanidins and Anthocyanins: Colored Pigments as Food, Pharmaceutical Ingredients, and the Potential Health Benefits. Food & Nutrition Research 2017, 61, 1361779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, T.C.; Giusti, M.M. Anthocyanins. Advances in Nutrition 2015, 6, 620–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobylewski, S.; Jacobson, M.F. Toxicology of Food Dyes. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health 2012, 18, 220–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amchova, P.; Kotolova, H.; Ruda-Kucerova, J. Health Safety Issues of Synthetic Food Colorants. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 2015, 73, 914–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carocho, M.; Morales, P.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Natural Food Additives: Quo Vadis? Trends in Food Science & Technology 2015, 45, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Ovando, A.; Pacheco-Hernández, Ma.D.L.; Páez-Hernández, Ma.E.; Rodríguez, J.A.; Galán-Vidal, C.A. Chemical Studies of Anthocyanins: A Review. Food Chemistry 2009, 113, 859–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouillard, R.; Dubois, J.-E. Mechanism of the Structural Transformations of Anthocyanins in Acidic Media. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977, 99, 1359–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patras, A.; Brunton, N.P.; O’Donnell, C.; Tiwari, B.K. Effect of Thermal Processing on Anthocyanin Stability in Foods; Mechanisms and Kinetics of Degradation. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2010, 21, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K.; Mori, M.; Kondo, T. Blue Flower Color Development by Anthocyanins: From Chemical Structure to Cell Physiology. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009, 26, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, G.; Brouillard, R. The Mechanism of Co-Pigmentation of Anthocyanins in Aqueous Solutions. Phytochemistry 1990, 29, 1097–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, K.; Hayashi, K. Metallo Anthocyanins. I. Reconstruction of Commelinin from Its Components, Awobanin, Flavocommelin and Magnesium. Proc. Jpn. Acad., Ser. B 1977, 53, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Giusti, M.M. Metal Chelates of Petunidin Derivatives Exhibit Enhanced Color and Stability. Foods 2020, 9, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissim-Levi, A.; Ovadia, R.; Forer, I.; Oren-Shamir, M. Increased Anthocyanin Accumulation in Ornamental Plants Due to Magnesium Treatment. The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology 2007, 82, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Li, C.; Shi, L.; Wang, L. Anthocyanins: Modified New Technologies and Challenges. Foods 2023, 12, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hondo, T.; Yoshida, K.; Nakagawa, A.; Kawai, T.; Tamura, H.; Goto, T. Structural Basis of Blue-Colour Development in Flower Petals from Commelina Communis. Nature 1992, 358, 515–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivichai, S.; Hongsprabhas, P. Profiling Anthocyanins in Thai Purple Yams (Dioscorea Alata L.). International Journal of Food Science 2020, 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.; Xu, J.; Kim, J.; Chen, T.-Y.; Su, X.; Standard, J.; Carey, E.; Griffin, J.; Herndon, B.; Katz, B.; et al. Role of Anthocyanin-Enriched Purple-Fleshed Sweet Potato P40 in Colorectal Cancer Prevention. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2013, 57, 1908–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Escudero, F.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Pérez-Alonso, J.J.; Yáñez, J.A.; Dueñas, M. HPLC-DAD-ESI/MS Identification of Anthocyanins in Dioscorea Trifida L. Yam Tubers (Purple Sachapapa). Eur Food Res Technol 2010, 230, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreno--Diaz, R.; Grau, N. Anthocyanin Pigments in Dioscorea Tryphida L. Journal of Food Science 1977, 42, 615–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harborne, J.B. Phytochemical Methods; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 1984; ISBN 978-94-010-8956-2. [Google Scholar]

- Bate-Smith, E.C. Paper Chromatography of Anthocyanins and Related Substances in Petal Extracts. Nature 1948, 161, 835–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daravingas, G.; Cain, R.F. The Anthocyanin Pigments of Black Raspberries. Journal of Food Science 1966, 31, 927–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asen, S. Anthocyanins in Bracts of Euphorbia Pulcherrima as Revealed by Paper Chromatographic and Spectrophotometric Methods. Plant Physiol. 1958, 33, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markakis, P.; Jurd, L. Anthocyanins and Their Stability in Foods. C R C Critical Reviews in Food Technology 1974, 4, 437–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.M.; Luh, B.S. Anthocyanin Pigments in the Hybrid Grape Variety Rubired. Journal of Food Science 1965, 30, 995–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekazos, E.D. Anthocianin Pigments in Red Tart Cherries. Journal of Food Science 1970, 35, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawanson, A.O.; Osude, B.A. Identification of the Anthocyanin Pigments of Zea Mays Linn, Var. E.S.1. Zeitschrift für Pflanzenphysiologie 1972, 67, 460–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberca Laveriano, L.D.; Carrero Tejeda, S.A.; Flores Barraza, R.R. Favorable Conditions for the Extraction of Anthocyanins from Purple Papaya (Dioscerea Trifida L.) Using a SOXHLET Apparatus, Universidad Nacional del Callao: Callao, Perú, 2017.

- Moriya, C.; Hosoya, T.; Agawa, S.; Sugiyama, Y.; Kozone, I.; Shin-ya, K.; Terahara, N.; Kumazawa, S. New Acylated Anthocyanins from Purple Yam and Their Antioxidant Activity. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 2015, 79, 1484–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, M.; Huang, S.; Wang, H.; Huang, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, L. Optimization of Ultrasonic-Assisted Extraction of Pigment from Dioscorea Cirrhosa by Response Surface Methodology and Evaluation of Its Stability. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 1576–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas-González, R.; Pateiro, M.; Domínguez-Valencia, R.; Carrillo, C.; Lorenzo, J.M. Optimization of Anthocyanin Extraction from Purple Sweet Potato Peel (Ipomea Batata) Using Sonotrode Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction. Foods 2025, 14, 2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, S.; Osorio-Tobón, J.F. Isolation and Characterization of Starch from the Purple Yam (Dioscorea Alata) Anthocyanin Extraction Residue Obtained by Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction. Waste Biomass Valor 2024, 15, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.D.J.L.; Canto, H.K.F.; Da Silva, L.H.M.; Rodrigues, A.M.D.C. Characterization and Properties of Purple Yam (Dioscorea Trifida) Powder Obtained by Refractance Window Drying. Drying Technology 2022, 40, 1103–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Valle Leguizamón, G.; Gonzáles León, A.; Báez Sañudo, R. Grape Anthocyanins (Vitis Vinifera L.) and Their Relation to Color. Revista Fitotecnia Mexicana 2005, 28, 359–368. [Google Scholar]

- Beyerlein, P.; Pereira, H.D.S. Morphological Diversity and Identification Key for Landraces of the Amerindian Yam in Central Amazon. Pesq. agropec. bras. 2018, 53, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Arévalo, J.; Ramírez Saavedra, R.; Adrianzen Julca, P.; Cobos Ruiz, M.; Castro Gómez, J. Diversidad Genética de Dioscorea Trifida “Sachapapa” de Cinco Cuencas Hidrográficas de La Amazonía Peruana. Cienc amaz (Iquitos) 2013, 3, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuisima-Coral, L.L.; Guillén Huachua, W.F. Genetic Variability of Yam (Dioscorea Trifida) Genotypes in the Ucayali Region, Peru. Agron. Colomb. 2022, 40, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedenko, V.S.; Shemet, S.A.; Landi, M. UV–Vis Spectroscopy and Colorimetric Models for Detecting Anthocyanin-Metal Complexes in Plants: An Overview of in Vitro and in Vivo Techniques. Journal of Plant Physiology 2017, 212, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Xu, S.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Qi, J.; Weng, L.; Cai, S.; Wang, J. Metabolome and Transcriptome Profiling Reveals Light-Induced Anthocyanin Biosynthesis and Anthocyanin-Related Key Transcription Factors in Yam (Dioscorea Alata L.). BMC Plant Biol 2025, 25, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.M.; Yan, R.X.; Zhang, P.T.; Han, X.Y.; Wang, L. Anthocyanin Accumulation Rate and the Biosynthesis Related Gene Expression in Dioscorea Alata. Biologia plant. 2015, 59, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Dixon, R.A. The ‘Ins’ and ‘Outs’ of Flavonoid Transport. Trends in Plant Science 2010, 15, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen-Yi, H.; Murray, J.R.; Ohmann, S.M.; Tong, C.B.S. Anthocyanin Accumulation during Potato Tuber Development. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci 1997, 122, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, P.M.; Harborne, J.B. Plant Biochemistry; Elsevier, 1997; ISBN 978-0-12-214674-9.

- Chen, X.; Sun, J.; Shan, N.; Ali, A.; Luo, S.; Wang, S.; Zhu, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Li, Z.; Fang, Y.; et al. DaMYB75 and DaMYB56 Antagonistically Regulate Anthocyanin Biosynthesis by Binding to the DaANS Promoter in Dioscorea Alata. The Crop Journal 2025, S2214514125000881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.-G.; Jiang, W.; Mantri, N.; Bao, X.-Q.; Chen, S.-L.; Tao, Z.-M. Transciptome Analysis Reveals Flavonoid Biosynthesis Regulation and Simple Sequence Repeats in Yam (Dioscorea Alata L.) Tubers. BMC Genomics 2015, 16, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera Ortíz, Mi.; Reza Vargas, M. del C.; Chew Madinaveitia, R.G.; Meza Velázquez, J.A. Functional Properties of Anthocyanins. Biotecnia 2011, 13, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Starr, M.S.; Francis, F.J. Effect of Metallic Ions on Color and Pigment Content of Cranberry Juice Cocktail. Journal of Food Science 1973, 38, 1043–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomé, F. de M.; García-Pinchi, R.; Carranza, J.; Alva, A. Obtaining Coloring from Dioscorea Trifida (Sachapapa Morada) by Atomization. Conoc. amaz 2010, 1, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza Sillerico, E.V.; Curi Borda, C.K.; Rojas Metrcado, V.J.; Alvarado Kirigin, J.A. Encapsulation, Characterization and Thermal Stability of Anthocyanins from Zea Mays L. (Purple Corn). Revista Boliviana de Química 2016, 33, 183–189. [Google Scholar]

- Arrazola, G.; Herazo, I.; Alvis, A. Obtaining and Evaluation of Stability of Eggplant Anthocyanins (Solanum Melongena L.) in Beverages. Inf. tecnol. 2014, 25, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niño Vega, E.M. Development and Stabilization of Food Colorants from Blackberry Extracts, University of Salamanca and Polytechnic Institute of Brangança: Braganza, 2019.

- Freitas da Silva, G.J.; Lessa Constant, P.B.; de Figueiredo, W.; Madeiros Moura, S. Formulation and Stability of Anthocyanin Dyes Extracted from Jabuticaba (Myrciaria Ssp.) Peels. Alim. Nutr. 2010, 21, 429–436. [Google Scholar]

- Acciarri, G. Stabilization of Natural Antioxidants through Encapsulation and Their Incorporation into Value-Added Dairy Products, Universidad Nacional del Litoral: Santa Fe, 2017.

- Ersus, S.; Yurdagel, U. Microencapsulation of Anthocyanin Pigments of Black Carrot (Daucus Carota L.) by Spray Drier. Journal of Food Engineering 2007, 80, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Li, X.; Ren, G.; Bu, Q.; Ruan, Y.; Feng, Y.; Li, B. Stability of Purple Corn Anthocyanin Encapsulated by Maltodextrin, and Its Combinations with Gum Arabic and Whey Protein Isolate. Foods 2023, 12, 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Oliveira, G.; Lila, M.A. Protein--binding Approaches for Improving Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability of Anthocyanins. Comp Rev Food Sci Food Safe 2023, 22, 333–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadalinejhad, S.; Kurek, M.A. Microencapsulation of Anthocyanins—Critical Review of Techniques and Wall Materials. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 3936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallet, M.; Faus, J.; García-España, E.; Moratal, J. Part III: Metals; Calcium and Magnesium. In Introduction to Bioinorganic Chemistry; Editorial Síntesis S. A: Madrid, España, 2003; p. 591.

- Moeller, T. Inorganic Chemistry; Editorial Reverté S. A: New York, U.S.A, 1961.

- Wee, M.G.V.; Chinnappan, A.; Ramakrishna, S. Elucidating Improvements to MIL-101(Cr)’s Porosity and Particle Size Distributions Based on Innovations and Fine-Tuning in Synthesis Procedures. Adv Materials Inter 2023, 10, 2300065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiono, M.; Matsugaki, N.; Takeda, K. Structure of the Blue Cornflower Pigment. Nature 2005, 436, 791–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, M.; Kondo, T.; Yoshida, K. Cyanosalvianin, a Supramolecular Blue Metalloanthocyanin, from Petals of Salvia Uliginosa. Phytochemistry 2008, 69, 3151–3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeagbo, A.I.; Azeez, A.A.; Ogunmola, O.O.; Sodamade, A.; Larayetan, R.A. The Anthocyanin Metal Interactions: An Overview. JCSN 2024, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marpaung, A.M.; Pustikarini, D. Spectrophotometric Change of Butterfly Pea (Clitoria Ternatea L.) Flower Extract in Various Metal Ion Solutions During Storage. Sci. Technol. Indones 2023, 8, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Vital, D.; Cortez, R.; Ongkowijoyo, P.; Gonzalez De Mejia, E. Protection of Color and Chemical Degradation of Anthocyanin from Purple Corn ( Zea Mays L.) by Zinc Ions and Alginate through Chemical Interaction in a Beverage Model. Food Research International 2018, 105, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) Safety of Aluminium from Dietary Intake – Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Food Additives, Flavourings, Processing Aids and Food Contact Materials (AFC). EFSA Journal 2008, 6. [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Forbes, A.; Guo, X.; He, L. Prediction of Anthocyanin Color Stability against Iron Co-Pigmentation by Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Foods 2022, 11, 3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astuti, E.; Ahmad, A.; Dali, S. Effect of Mg (II) Metal Ion on Antioxidant Activities of Ethanol Extracts of Rambutan Peel (Nephelium Lappaceum). ICA 2019, 11, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Anthocyanins | Values Rf x100 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| From D. trifida L. | Bibliographic source | |||

| BAW a | HCl 1% | BAW | HCl 1% | |

| Peonidin-3,5-diglucoside | 23 | 17 | 23 | 17 |

| Carreño and Grau (1977) [20] | Harborne (1984) [21] | |||

| Malvidin-3,5-diglucoside | 31 | 22 | 31 | 22 |

| Carreño and Grau (1977) [20] | Bate-Smith (1948) [22] | |||

| Cyanidin-3-rhamnosyl-glucoside | 32 | 19 | 32 | 19 |

| Daravingas and Cain (1966) [23] | Daravingas and Cain (1966) [23], Harborne (1984) [21] | |||

| Pelargonidin-3,5-diglucoside | 34 | 23 | 34 | 23 |

| Asen (1958) [24] | Harborne (1984) [21] | |||

| Anthocyanidins | Forestal b | Formic c | Forestal | Formic |

| Cyanidin | 49 | 22 | 49 | 22 |

| Harborne (1984) [21], Markakis and Jurd (1974) [25], Smith and Luh (1965) [26] and Dekazos (1970) [27] | Harborne (1984) [21], Markakis and Jurd (1974) [25], Smith and Luh (1965) [26] | |||

| Malvidin | 60 | 27 | 60 | 27 |

| Harborne (1984) [21], Markakis and Jurd (1974) [25], Smith and Luh (1965) [26] | ||||

| Peonidin | 63 | 30 | 63 | 30 |

| Harborne (1984) [21], Markakis and Jurd (1974) [25], Smith and Luh (1965) [26] | Harborne (1984) [21], Markakis and Jurd (1974) [25], Smith and Luh (1965) [26] and Dekazos (1970) [27] | |||

| Pelargonidin | 68 | 33 | 68 | 33 |

| Harborne (1984) [21], Markakis and Jurd (1974) [25] and Lawanson and Osude (1972) [28] | Harborne (1984) [21], Markakis and Jurd (1974) [25] | |||

| Time (months) | Measured absorbance | Projected absorbance |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2.000 | 2.000 |

| 4 | 1.990 | 1.990 |

| 6 | 1.980 | 1.985 |

| 8 | 1.978 | 1.980 |

| 10 | 1.976 | 1.975 |

| 20 | - | 1.950 |

| 30 | - | 1.925 |

| 36 | - | 1.900 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).