Submitted:

13 July 2024

Posted:

16 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Study Area and Data

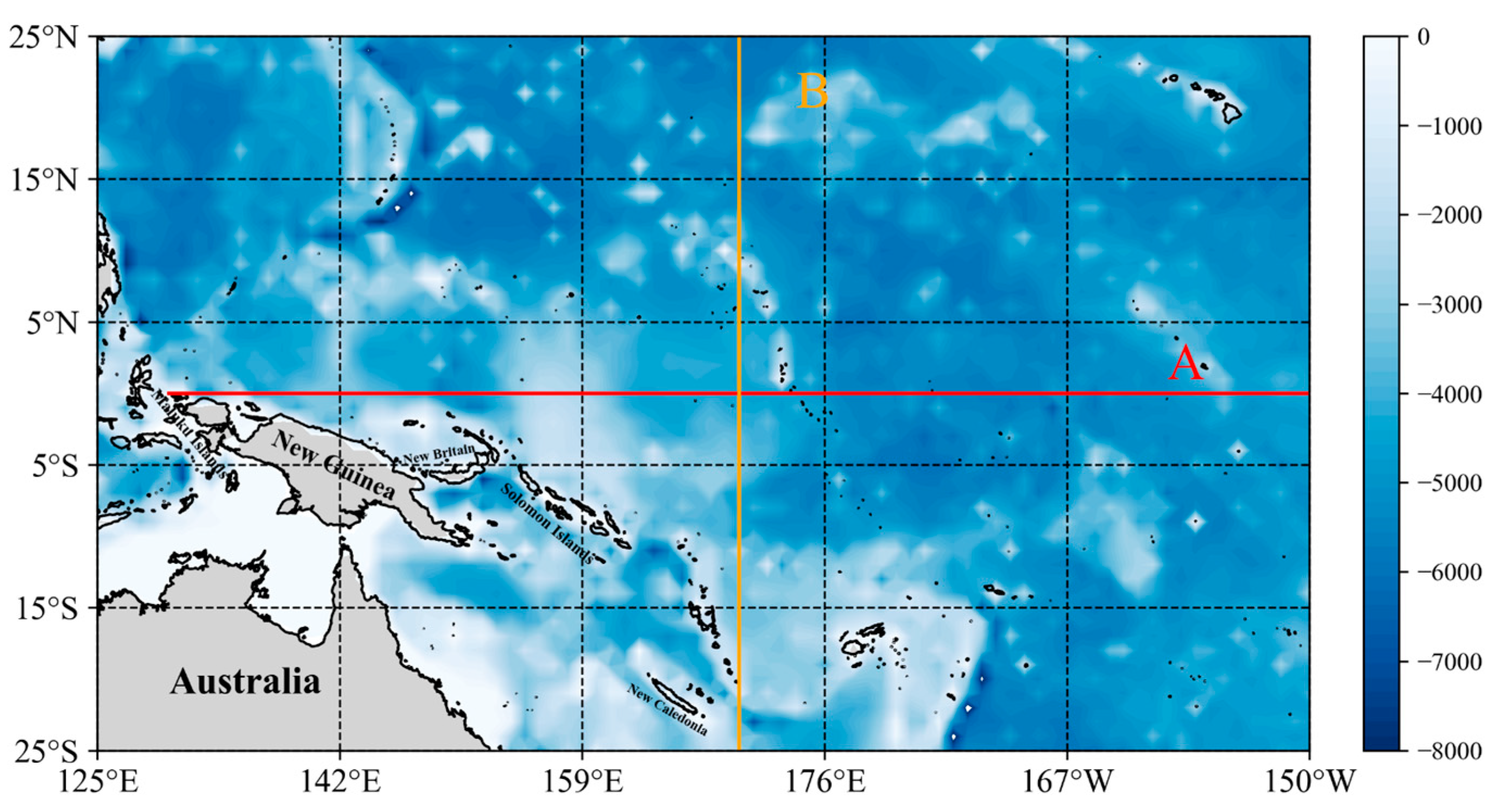

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Source and Preprocessing

3. Methods

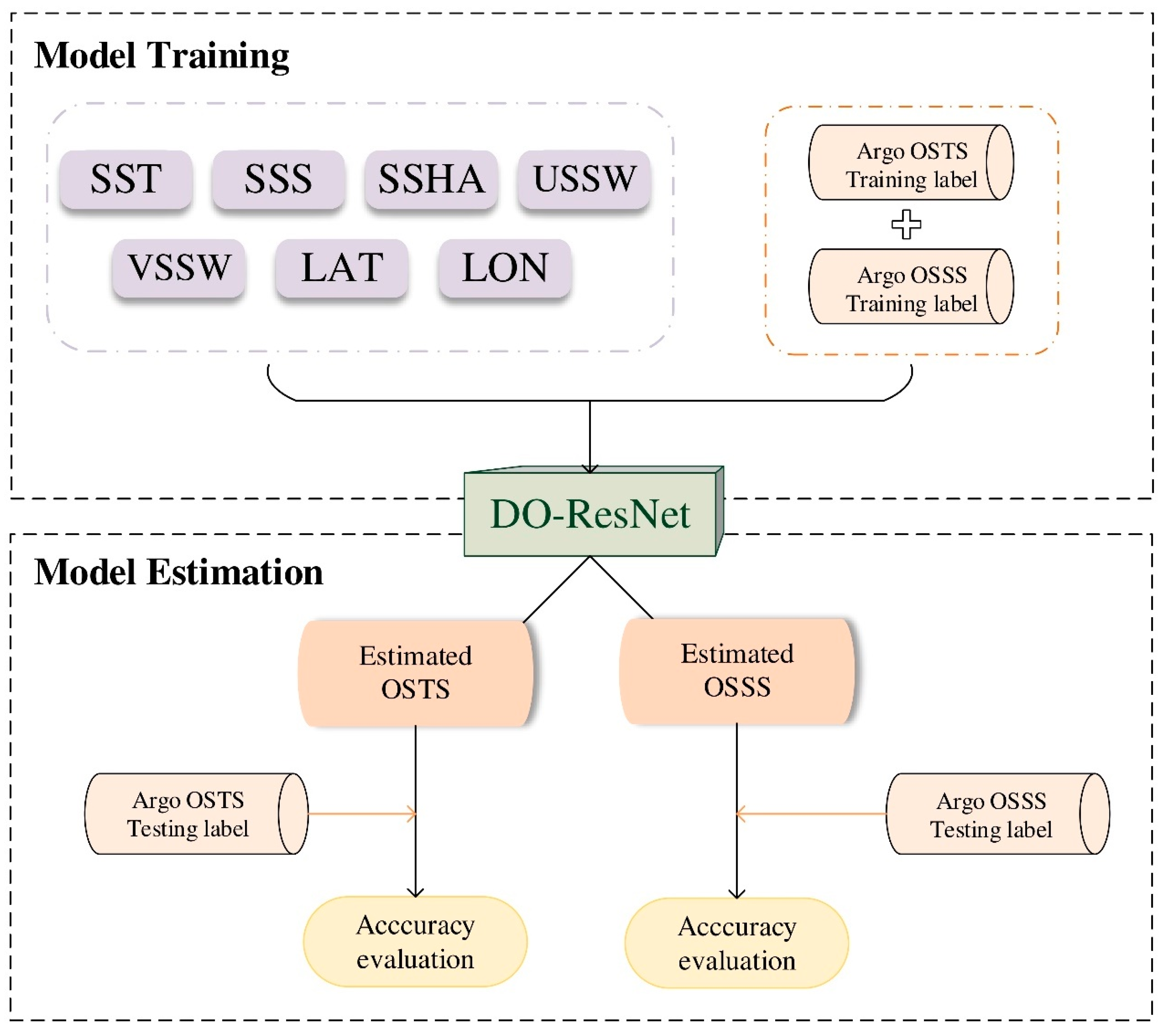

3.1. The DO-ResNet Model

3.2. Experimental Setup

4. Results

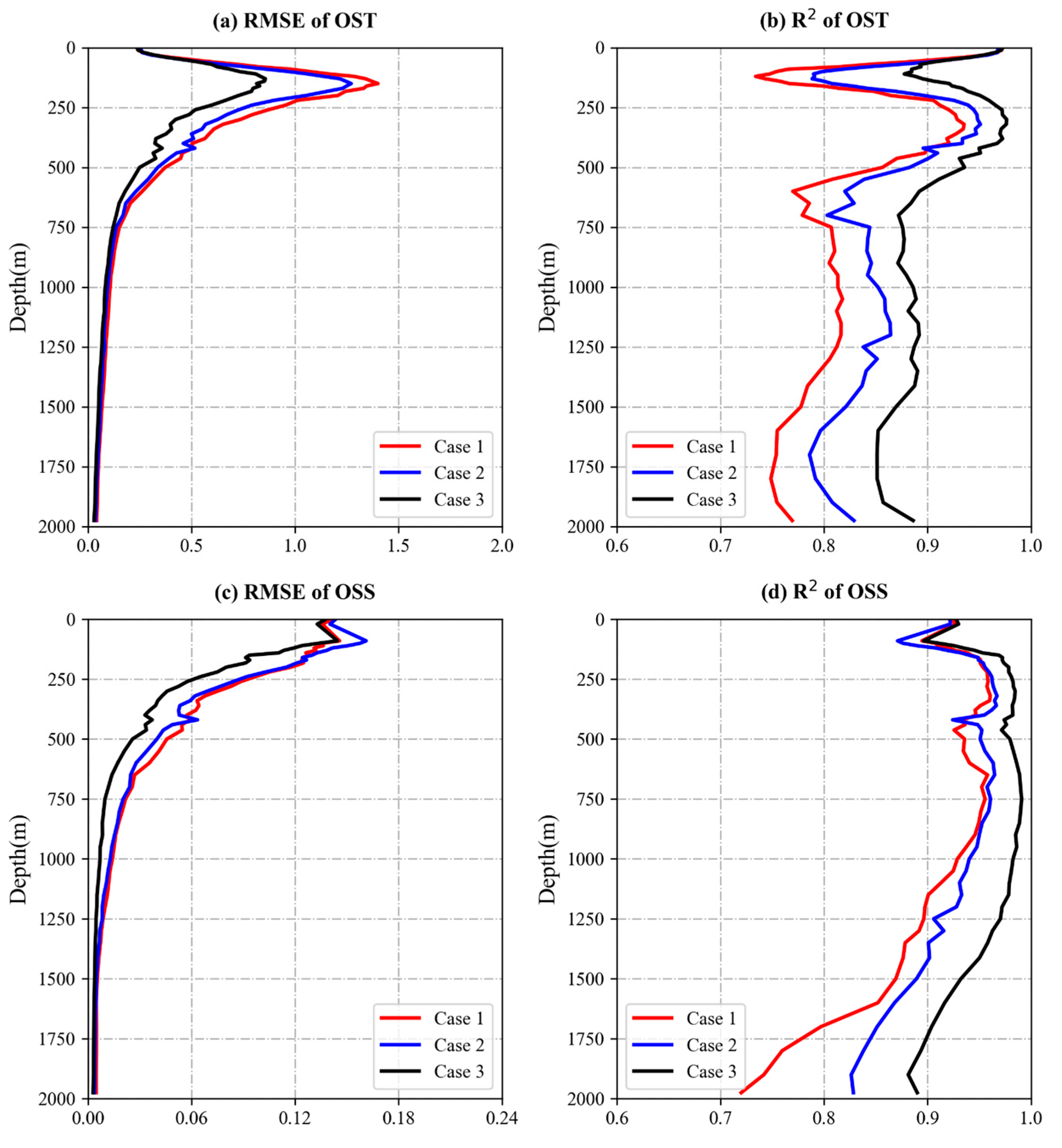

4.1. Identification of Input Variable

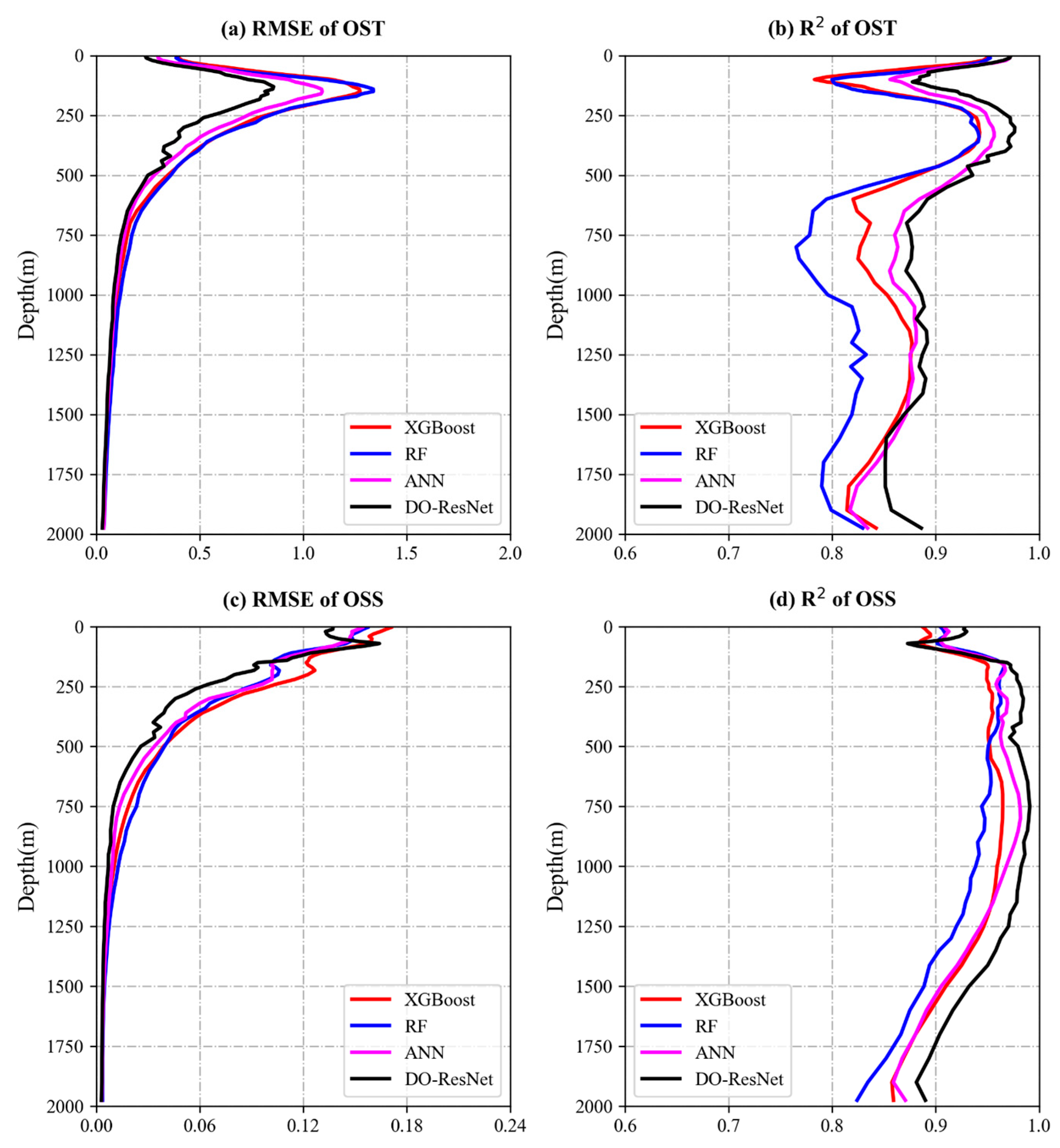

4.2. Accuracy Comparison between the DO-ResNet Model and Other Model

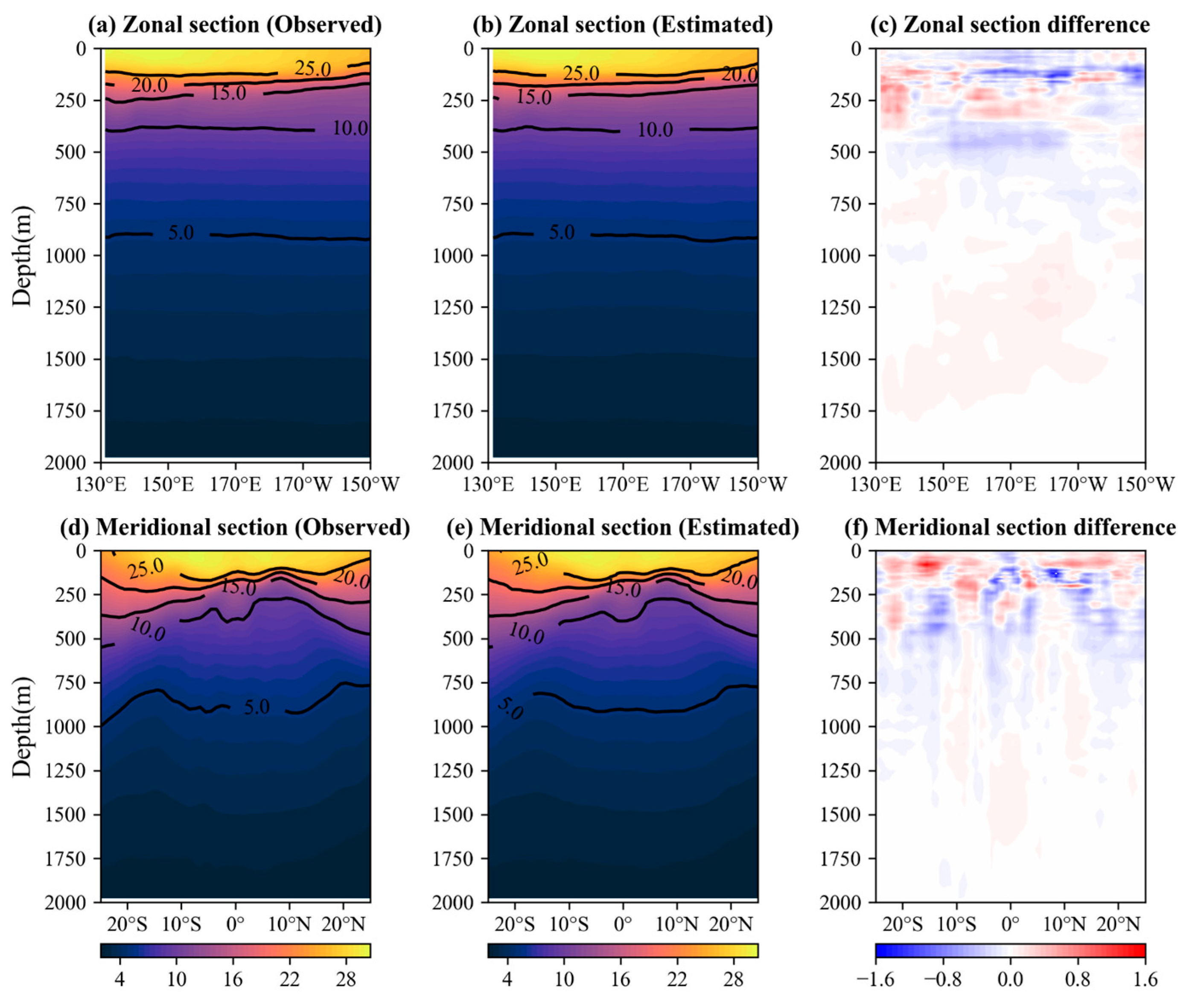

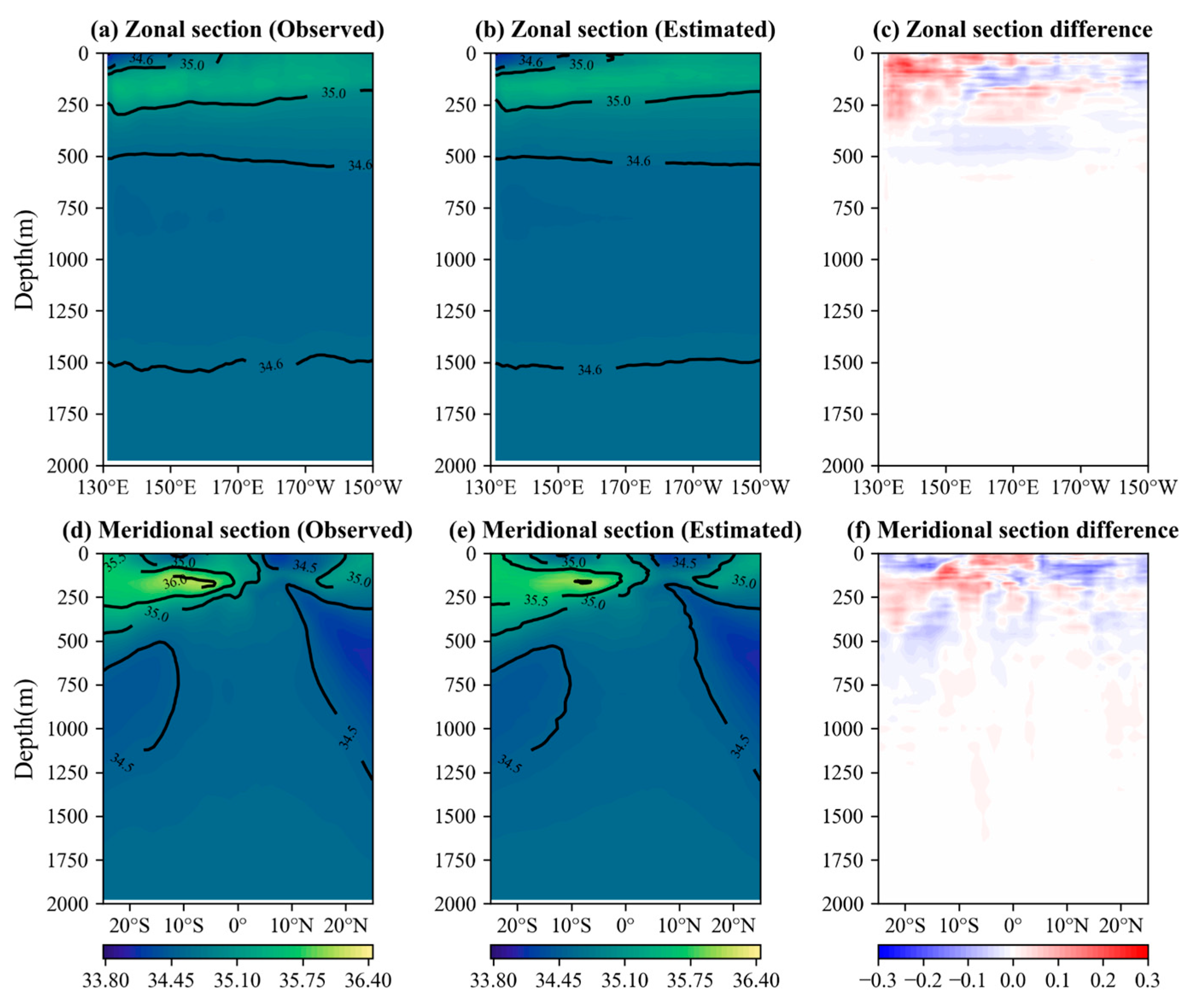

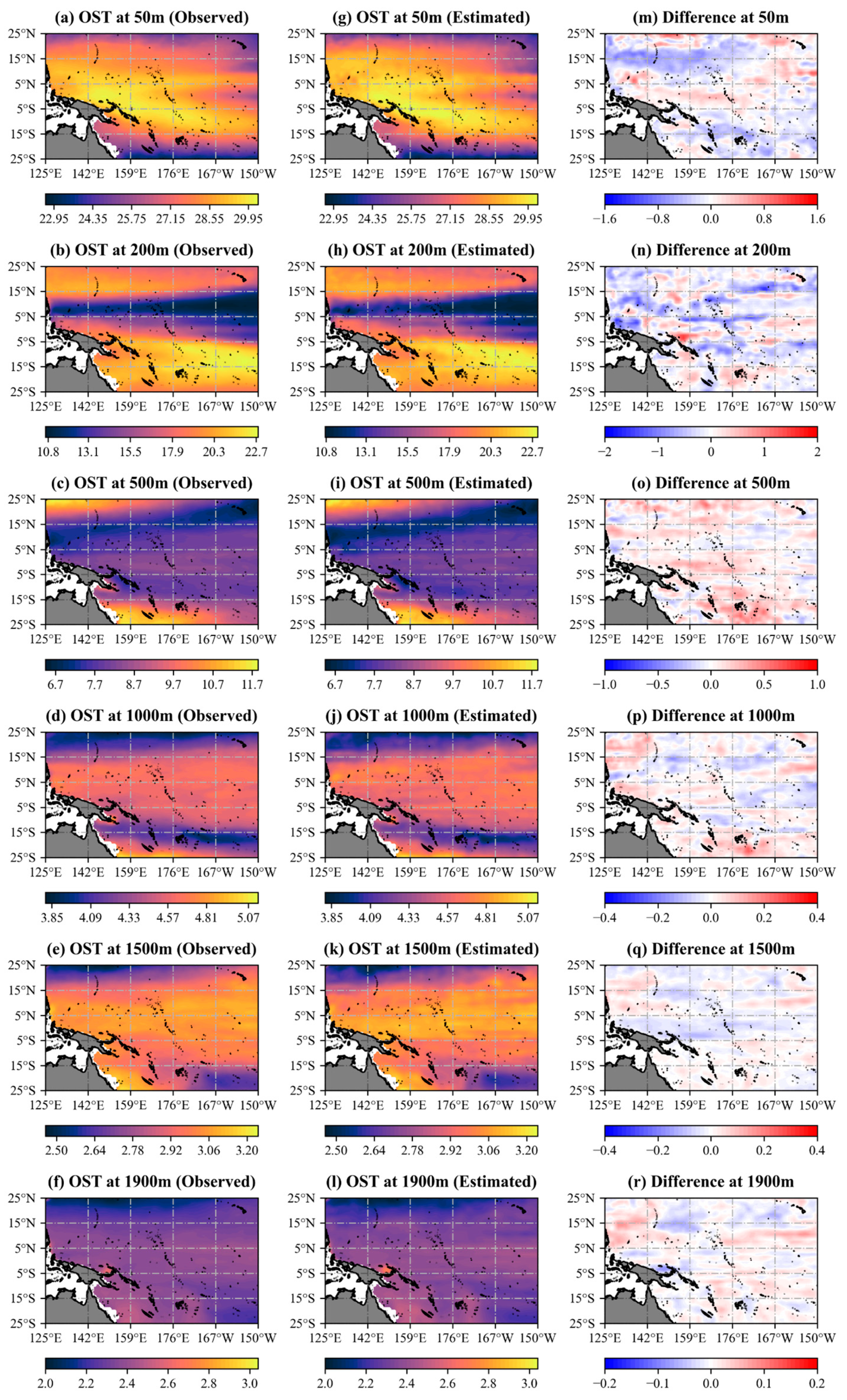

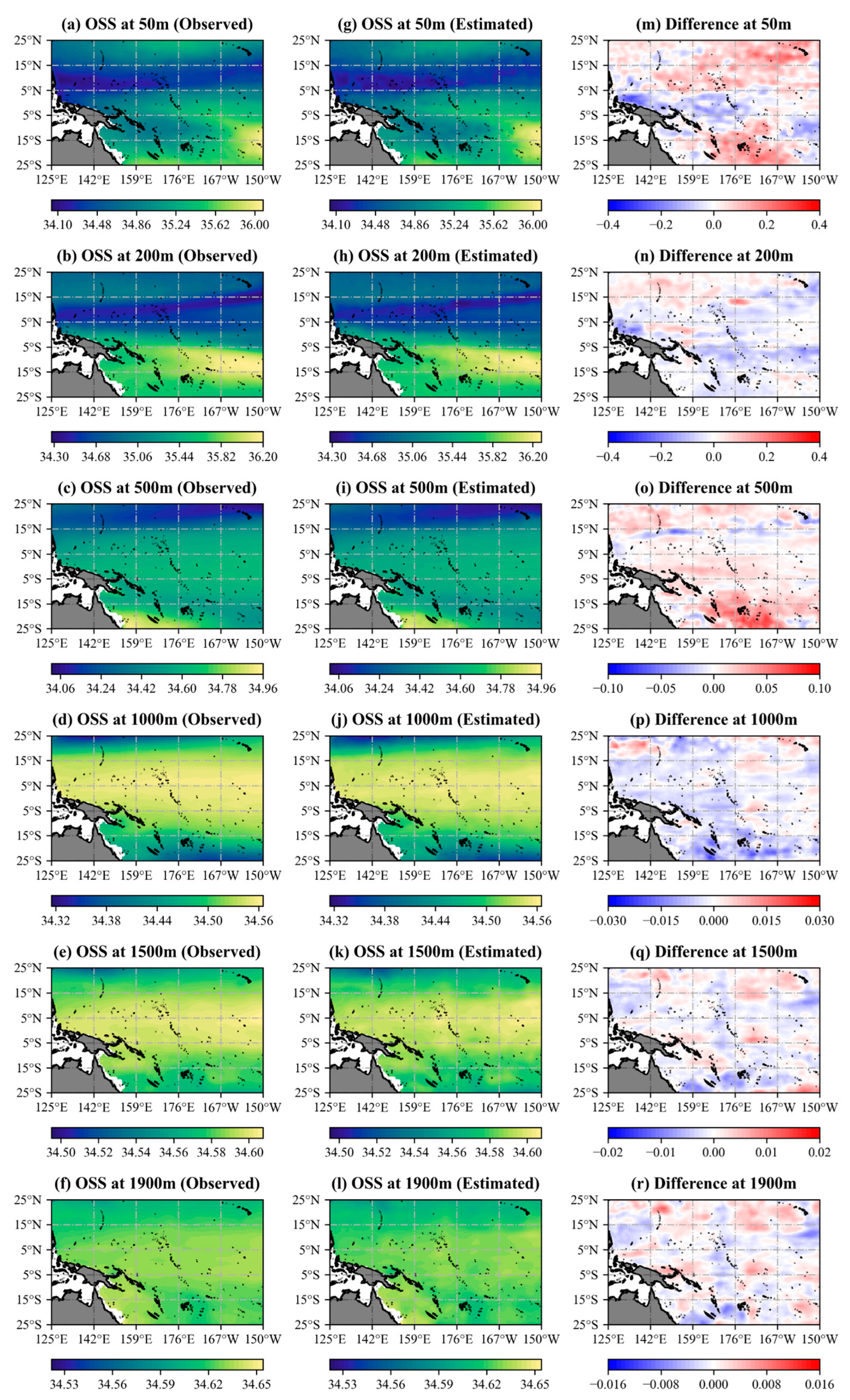

4.3. Vertical Performance Evaluation of the DO-ResNet Model

4.4. Seasonal Performance of the DO-ResNet Model

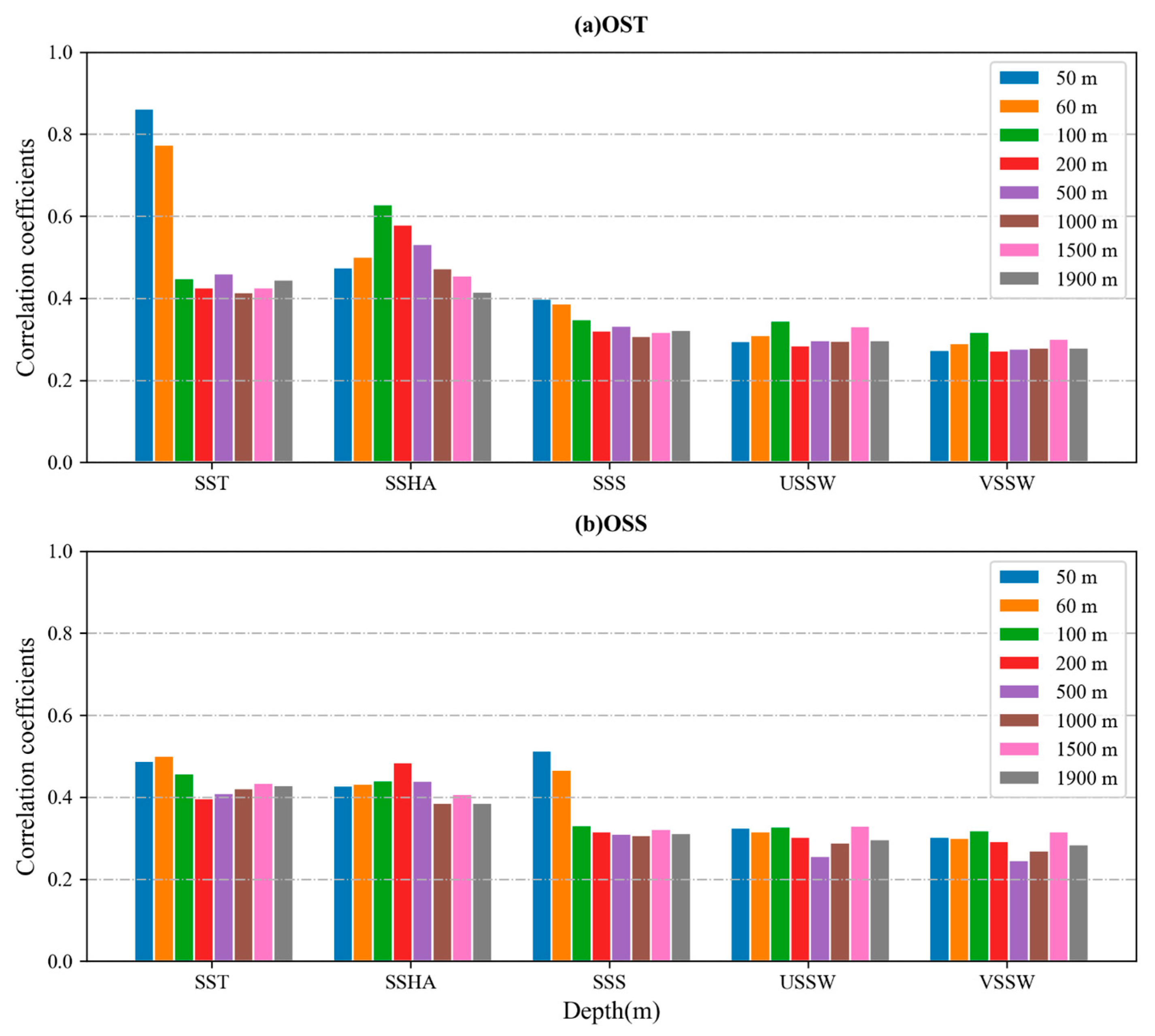

4.5. Correlation Analysis between the OST (OSS) and Surface Parameters

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smale, D.A.; Wernberg, T.; Oliver, E.C.J.; Thomsen, M.; Harvey, B.P.; Straub, S.C.; Burrows, M.T.; Alexander, L.V.; Benthuysen, J.A.; Donat, M.G.; et al. Marine Heatwaves Threaten Global Biodiversity and the Provision of Ecosystem Services. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2019, 9, 306–312. [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.-Y.; Tozuka, T.; Ng, B.; Cai, W. Thermocline Warming Induced Extreme Indian Ocean Dipole in 2019. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47. [CrossRef]

- Planton, Y.Y.; Vialard, J.; Guilyardi, E.; Lengaigne, M.; McPhaden, M.J. The Asymmetric Influence of Ocean Heat Content on ENSO Predictability in the CNRM-CM5 Coupled General Circulation Model. J. Clim. 2021, 34, 5775–5793. [CrossRef]

- Durack, P.J.; Wijffels, S.E.; Matear, R.J. Ocean Salinities Reveal Strong Global Water Cycle Intensification During 1950 to 2000. Science 2012, 336, 455–458. [CrossRef]

- Stark, S.; Wood, R.A.; Banks, H.T. Reevaluating the Causes of Observed Changes in Indian Ocean Water Masses. J. Clim. 2006, 19, 4075–4086. [CrossRef]

- Barreiro, M.; Fedorov, A.; Pacanowski, R.; Philander, S. Abrupt Climate Changes: How Freshening of the Northern Atlantic Affects the Thermohaline and Wind-Driven Oceanic Circulations. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2008, 36, 33–58. [CrossRef]

- Ghil, M.; Malanotte-Rizzoli, P. Data Assimilation in Meteorology and Oceanography. Adv. Geophys. 1991, 33, 141–266. [CrossRef]

- Troccoli, A.; Haines, K. Use of the Temperature–Salinity Relation in a Data Assimilation Context. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 1999, 16, 2011–2025. [CrossRef]

- Vossepoel, F.C.; Behringer, D.W. Impact of Sea Level Assimilation on Salinity Variability in the Western Equatorial Pacific. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2000, 30, 1706–1721. [CrossRef]

- Carrassi, A.; Bocquet, M.; Bertino, L.; Evensen, G. Data Assimilation in the Geosciences: An Overview of Methods, Issues, and Perspectives. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2018, 9, e535. [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.M.; Martin, M.J.; Akella, S.; Arango, H.G.; Balmaseda, M.; Bertino, L.; Ciavatta, S.; Cornuelle, B.; Cummings, J.; Frolov, S.; et al. Synthesis of Ocean Observations Using Data Assimilation for Operational, Real-Time and Reanalysis Systems: A More Complete Picture of the State of the Ocean. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6. [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Bertino, L.; Zhu, J. Assimilating Altimetry Data into a HYCOM Model of the Pacific: Ensemble Optimal Interpolation versus Ensemble Kalman Filter. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2010, 27, 753–765. [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Yan, X.-H. Remote Sensing for Subsurface and Deeper Oceans: An Overview and a Future Outlook. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 10, 72–92. [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, P.C. Surface Manifestations of Subsurface Thermal Structure in the California Current. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 1988, 93, 4975–4983. [CrossRef]

- Chu, P.C.; Fan, C.; Liu, W.T. Determination of Vertical Thermal Structure from Sea Surface Temperature. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2000, 17, 971–979. [CrossRef]

- Willis, J.K.; Roemmich, D.; Cornuelle, B. Combining Altimetric Height with Broadscale Profile Data to Estimate Steric Height, Heat Storage, Subsurface Temperature, and Sea-Surface Temperature Variability. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2003, 108. [CrossRef]

- Carnes, M.R.; Mitchell, J.L.; de Witt, P.W. Synthetic Temperature Profiles Derived from Geosat Altimetry: Comparison with Air-Dropped Expendable Bathythermograph Profiles. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 1990, 95, 17979–17992. [CrossRef]

- Carnes, M.R.; Teague, W.J.; Mitchell, J.L. Inference of Subsurface Thermohaline Structure from Fields Measurable by Satellite. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 1994, 11, 551–566. [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, R.; Chen, J.; Bao, S.; Wang, G. A Dynamical-Statistical Approach to Retrieve the Ocean Interior Structure From Surface Data: SQG-mEOF-R. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2020, 125. [CrossRef]

- Maes, C.; Behringer, D.; Reynolds, R.W.; Ji, M. Retrospective Analysis of the Salinity Variability in the Western Tropical Pacific Ocean Using an Indirect Minimization Approach. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2000, 17, 512–524. [CrossRef]

- Guinehut, S.; Dhomps, A.-L.; Larnicol, G.; Le Traon, P.-Y. High Resolution 3-D Temperature and Salinity Fields Derived from in Situ and Satellite Observations. Ocean Science 2012, 8, 845–857. [CrossRef]

- Maes, C.; Behringer, D.; Reynolds, R.W.; Ji, M. Retrospective Analysis of the Salinity Variability in the Western Tropical Pacific Ocean Using an Indirect Minimization Approach. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2000, 17, 512–524. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Li, X.; Zhang, R.-H.; Liu, B. Purely Satellite Data–Driven Deep Learning Forecast of Complicated Tropical Instability Waves. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba1482. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, X. Combination of Satellite Observations and Machine Learning Method for Internal Wave Forecast in the Sulu and Celebes Seas. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 2822–2832. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Zheng, Q. A Machine-Learning Model for Forecasting Internal Wave Propagation in the Andaman Sea. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 3095–3106. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Song, J.; Li, X.; Zhong, G.; Zhang, B. Carbon Sinks and Variations of pCO2 in the Southern Ocean From 1998 to 2018 Based on a Deep Learning Approach. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 3495–3503. [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.M.; Swain, D.; Weller, R.A. Estimation of Ocean Subsurface Thermal Structure from Surface Parameters: A Neural Network Approach. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2004, 31. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Yan, X.-H.; Jo, Y.-H.; Liu, W.T. Estimation of Subsurface Temperature Anomaly in the North Atlantic Using a Self-Organizing Map Neural Network. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2012, 29, 1675–1688. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Yang, K.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Y. Reconstructing the Subsurface Temperature Field by Using Sea Surface Data Through Self-Organizing Map Method. IEEE Geosci. Remote. Sens. Lett. 2018, 15, 1812–1816. [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Qi, J.; Yin, B.; Zhi, H.; Li, D.; Yang, S.; Wang, W.; Cai, H.; Xie, B. Reconstruction of Subsurface Salinity Structure in the South China Sea Using Satellite Observations: A LightGBM-Based Deep Forest Method. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3494. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Su, H.; Wang, X.; Yan, X. Estimation of Global Subsurface Temperature Anomaly Based on Multisource Satellite Observations. J. Remote Sens. 2017, 21, 881–891. [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Li, W.; Yan, X.-H. Retrieving Temperature Anomaly in the Global Subsurface and Deeper Ocean From Satellite Observations. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2018, 123, 399–410. [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Wu, X.; Yan, X.-H.; Kidwell, A. Estimation of Subsurface Temperature Anomaly in the Indian Ocean during Recent Global Surface Warming Hiatus from Satellite Measurements: A Support Vector Machine Approach. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 160, 63–71. [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Yang, X.; Lu, W.; Yan, X.-H. Estimating Subsurface Thermohaline Structure of the Global Ocean Using Surface Remote Sensing Observations. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1598. [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Yan, C.; Zhuang, W.; Zhang, W.; Geng, X.; Yan, X.-H. Reconstructing High-Resolution Ocean Subsurface and Interior Temperature and Salinity Anomalies From Satellite Observations. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Zhang, T.; Lin, M.; Lu, W.; Yan, X.-H. Predicting Subsurface Thermohaline Structure from Remote Sensing Data Based on Long Short-Term Memory Neural Networks. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 260, 112465. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Sun, L.; Li, J. Neural Network Approach to Retrieving Ocean Subsurface Temperatures from Surface Parameters Observed by Satellites. Water 2021, 13, 388. [CrossRef]

- Mao, K.; Liu, C.; Zhang, S.; Gao, F. Reconstructing Ocean Subsurface Temperature and Salinity from Sea Surface Information Based on Dual Path Convolutional Neural Networks. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1030. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Song, T.; Zhu, S.; Yang, S.; Feng, L. Subsurface Temperature Estimation from Sea Surface Data Using Neural Network Models in the Western Pacific Ocean. Mathematics 2021, 9, 852. [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Xu, J.; Tie, X.; Wu, J. Impact of the 2015 El Nino Event on Winter Air Quality in China. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34275. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, P.; Yu, R.; Guo, Y.; Li, Q.; Ren, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, W.; Liu, Y.; Ding, Y. The Strong El Niño of 2015/16 and Its Dominant Impacts on Global and China’s Climate. J. Meteorol. Res. 2016, 30, 283–297. [CrossRef]

- Cane, M.A. A Role for the Tropical Pacific. Science 1998, 282, 59–61. [CrossRef]

- Picaut, J.; Ioualalen, M.; Menkes, C.; Delcroix, T.; McPhaden, M.J. Mechanism of the Zonal Displacements of the Pacific Warm Pool: Implications for ENSO. Science 1996, 274, 1486–1489. [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, T.; Yumoto, M.; Iizuka, S. A Mechanism of Interdecadal Variability of Tropical Cyclone Activity over the Western North Pacific. Clim. Dyn. 2003, 21, 105–117. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.-H.; Zhou, G.; Zhi, H.; Gao, C.; Wang, H.; Feng, L. Salinity Interdecadal Variability in the Western Equatorial Pacific and Its Effects during 1950–2018. Clim. Dyn. 2023, 60, 1963–1985. [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Sun, F. Impacts of the Tropical Western Pacific on the East Asian Summer Monsoon. J. Meteorol. Soc. Japan 1992, 70, 243–256. [CrossRef]

- Boutin, J.; Vergely, J.L.; Marchand, S.; D’Amico, F.; Hasson, A.; Kolodziejczyk, N.; Reul, N.; Reverdin, G.; Vialard, J. New SMOS Sea Surface Salinity with Reduced Systematic Errors and Improved Variability. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 214, 115–134. [CrossRef]

- Banzon, V.; Smith, T.M.; Chin, T.M.; Liu, C.; Hankins, W. A Long-Term Record of Blended Satellite and in Situ Sea-Surface Temperature for Climate Monitoring, Modeling and Environmental Studies. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2016, 8, 165–176. [CrossRef]

- Hauser, D.; Tourain, C.; Hermozo, L.; Alraddawi, D.; Aouf, L.; Chapron, B.; Dalphinet, A.; Delaye, L.; Dalila, M.; Dormy, E.; et al. New Observations From the SWIM Radar On-Board CFOSAT: Instrument Validation and Ocean Wave Measurement Assessment. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 5–26. [CrossRef]

- Atlas, R.; Hoffman, R.N.; Ardizzone, J.; Leidner, S.M.; Jusem, J.C.; Smith, D.K.; Gombos, D. A Cross-Calibrated, Multiplatform Ocean Surface Wind Velocity Product for Meteorological and Oceanographic Applications. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2011, 92, 157–174. [CrossRef]

- Roemmich, D.; Gilson, J. The 2004–2008 Mean and Annual Cycle of Temperature, Salinity, and Steric Height in the Global Ocean from the Argo Program. Prog. Oceanogr 2009, 82, 81–100. [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; Las Vegas, NV, USA, June 27 2016.

- Chen, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, R.; Qiu, R.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, C.; Shang, H. ResNet18DNN: Prediction Approach of Drug-Induced Liver Injury by Deep Neural Network with ResNet18. Brief Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbab503. [CrossRef]

- Dzakmic, Š. Evaluation of ResNet Network for Semantic Segmentation of Coral Reefs. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2020, 8, 54–61. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Hua, X.; Liu, W.; Wickert, J. Sea Ice Detection from GNSS-R Data Based on Residual Network. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4477. [CrossRef]

- Eshaq, R.M.A.; Hu, E.; Qaid, H.A.A.M.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, T. Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks and Infrared Thermography to Identify Coal Quality and Gangue. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 147315–147327. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Ye, X.; Xu, Q.; Yin, X.; Xu, S. Sea Surface Chlorophyll-a Concentration Retrieval from HY-1C Satellite Data Based on Residual Network. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3696. [CrossRef]

- Nair, V.; Hinton, G.E. Rectified Linear Units Improve Restricted Boltzmann Machines. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on International Conference on Machine Learning; Haifa, Israel, June 21 2010.

- Talley, L.D.; Pickard, G.L.; Emery, W.J. Descriptive Physical Oceanography: An Introduction; 6th ed.; Academic Press: Amsterdam ; Boston, 2011; pp. 350-360.

- Gueye, M.B.; Niang, A.; Arnault, S.; Thiria, S.; Crépon, M. Neural Approach to Inverting Complex System: Application to Ocean Salinity Profile Estimation from Surface Parameters. Comput Geosci 2014, 72, 201–209. [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Lu, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, H.; Lu, W.; Wu, W. Estimating Coastal Chlorophyll-A Concentration from Time-Series OLCI Data Based on Machine Learning. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 576. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, R.-H.; Li, D.; Chen, D. The Thermocline Biases in the Tropical North Pacific and Their Attributions. J. Clim. 2021, 34, 1635–1648. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, F. Thermohaline Intrusions in the Thermocline of the Western Tropical Pacific Ocean. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2013, 32, 47–56. [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Zhang, L.; Yin, B.; Li, D.; Xie, B.; Sun, G. Advancing Ocean Subsurface Thermal Structure Estimation in the Pacific Ocean: A Multi-Model Ensemble Machine Learning Approach. Dyn. Atmospheres Oceans 2023, 104, 101403. [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Liu, C.; Chi, J.; Li, D.; Gao, L.; Yin, B. An Ensemble-Based Machine Learning Model for Estimation of Subsurface Thermal Structure in the South China Sea. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 3207. [CrossRef]

- Skliris, N.; Marsh, R.; Josey, S.A.; Good, S.A.; Liu, C.; Allan, R.P. Salinity Changes in the World Ocean since 1950 in Relation to Changing Surface Freshwater Fluxes. Clim. Dyn. 2014, 43, 709–736. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xu, F. Decadal Variability and Trends of Oceanic Barrier Layers in Tropical Pacific. Ocean Dyn. 2018, 68, 1155–1168. [CrossRef]

| Index | Contents | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Area | ) | |||

| Data | SSS | 2010-2020 | SMOS | Input |

| SST | 2010-2020 | NOAA | ||

| SSHA | 2010-2020 | AVISO | ||

| SSW | 2010-2020 | CCMP | ||

| OST | 2010-2020 | RG-Argo | Label | |

| OSS | 2010-2020 | RG-Argo | ||

| Resolution | monthly | |||

| Estimation Models | Parameter Values |

|---|---|

| DO-ResNet | convolutional layer: size = 3×3, stride = 1; adaptiveavgpool2d: output_size = 1×1; loss function: mse; optimizer: radam; learning rate: 0.02; reducelronplateau: mode = ‘min’, factor = 0.1, patience = 10; batch size: 2048; activation function: relu; batchnorm2d; validation frequency: per epoch earlystopping: patience = 7, verbose=False, delta=0 |

| Experiments | Training Methods |

|---|---|

| Case 1 (3 parameters) | OST (OSS) = Ensemble (SST, SSS, SSHA) |

| Case 2 (5 parameters) | OST (OSS) = Ensemble (SST, SSS, SSHA, USSW, VSSW) |

| Case 3 (7 parameters) | OST (OSS) = Ensemble (SST, SSS, SSHA, USSW, VSSW, LON, LAT) |

| Models | Parameter Values |

|---|---|

| XGBoost | eta = 0.02, min_child_weight = 2.0, max_depth = 5, subsample = 0.8 |

| RF | min_samples_split = 100, min_samples_leaf = 20, max_depth = 8, random_state = 10 |

| ANN | number of neural network layers = 3, learning rate = 0.002, number of neurons per layer = 30, loss function = MSE |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).