Submitted:

15 July 2024

Posted:

16 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

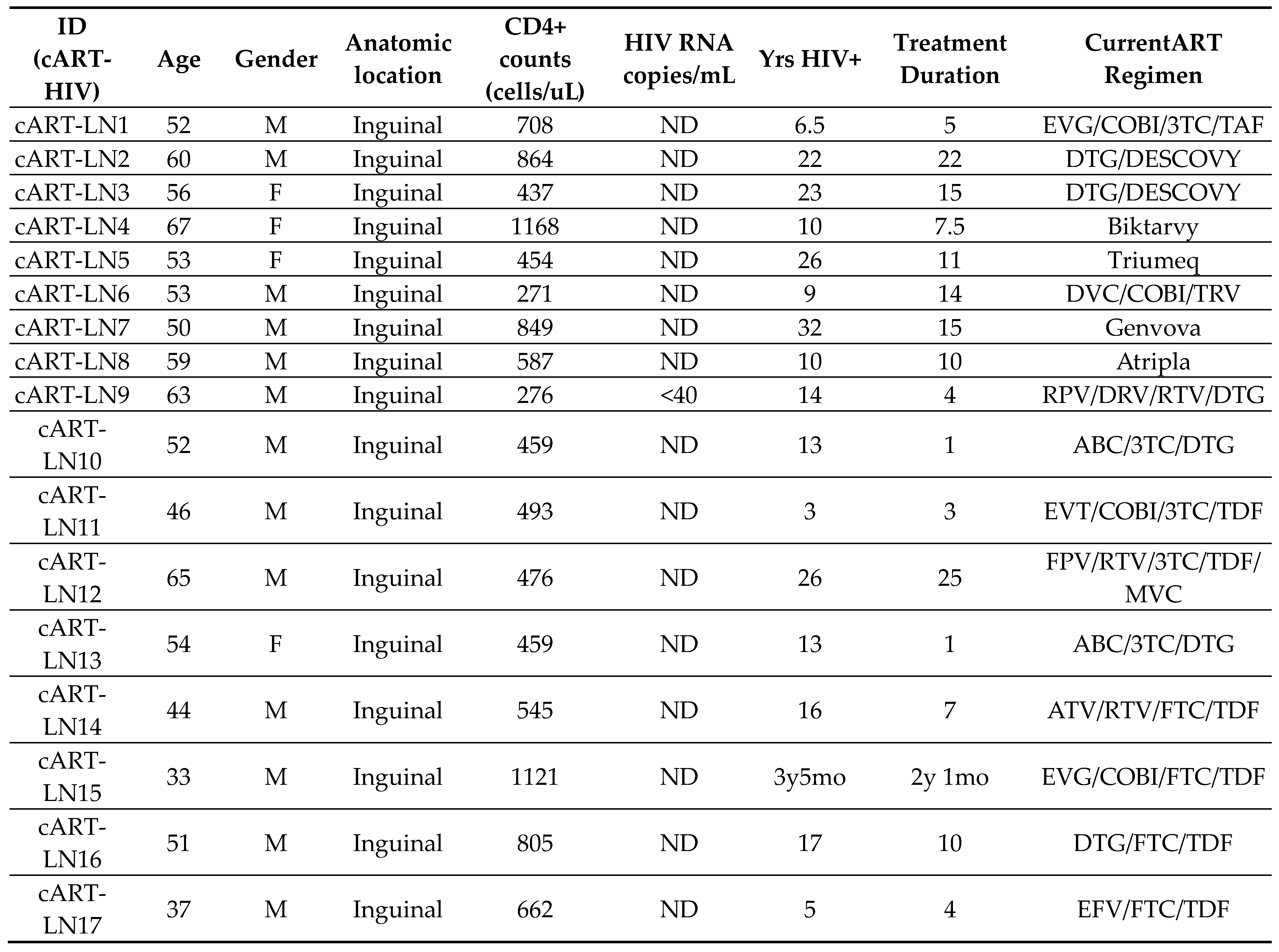

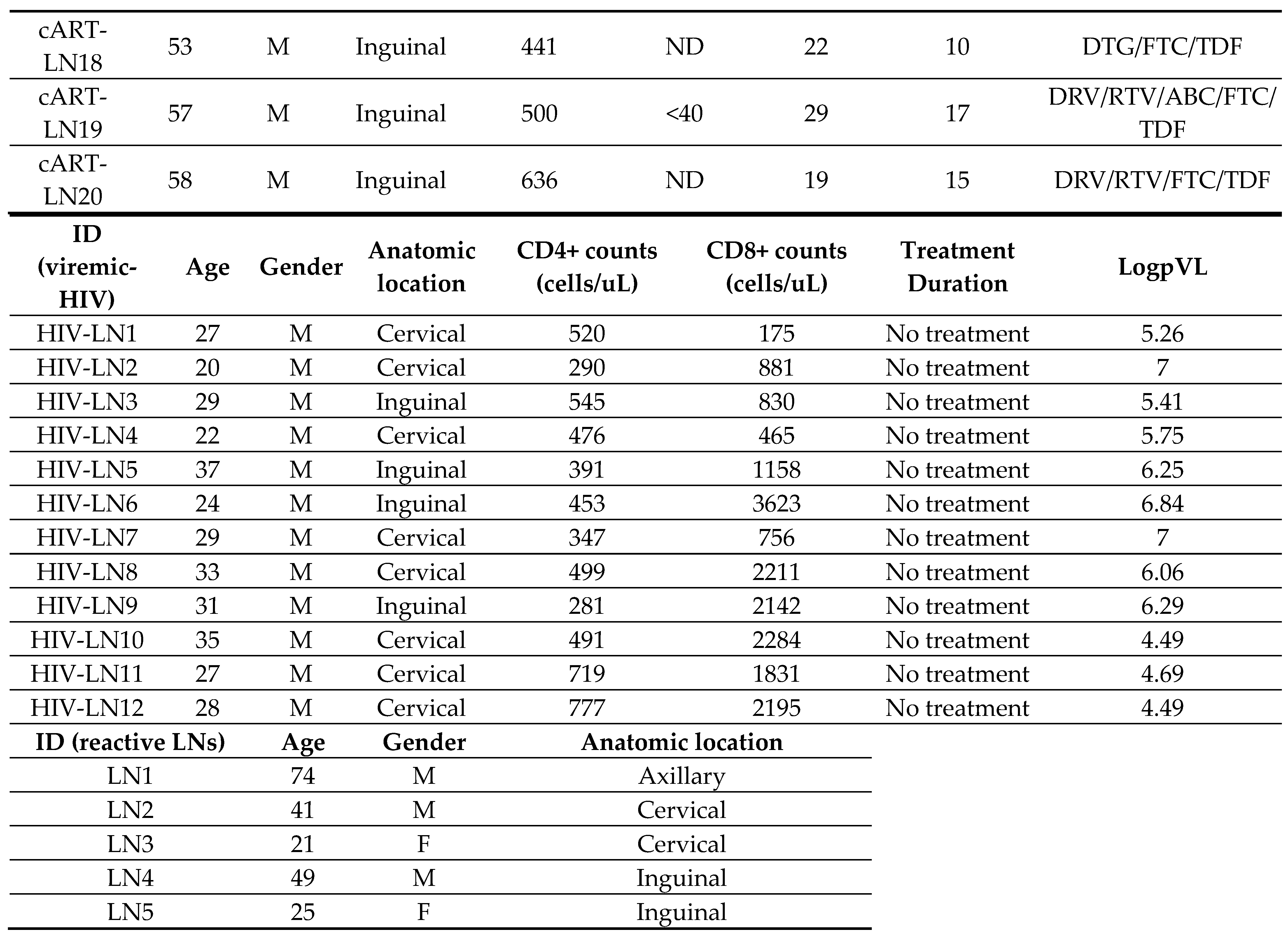

2.1. Human Material

2.2. Tissue Processing

2.3. Confocal Imaging Assays

2.3.1. Tissue Staining & Data Acquisition

2.3.2. Quantitative Imaging Analysis (Histocytometry)

2.3.3. Data analysis-Neighboring Analysis

2.3.4. Viral Load Measurement

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

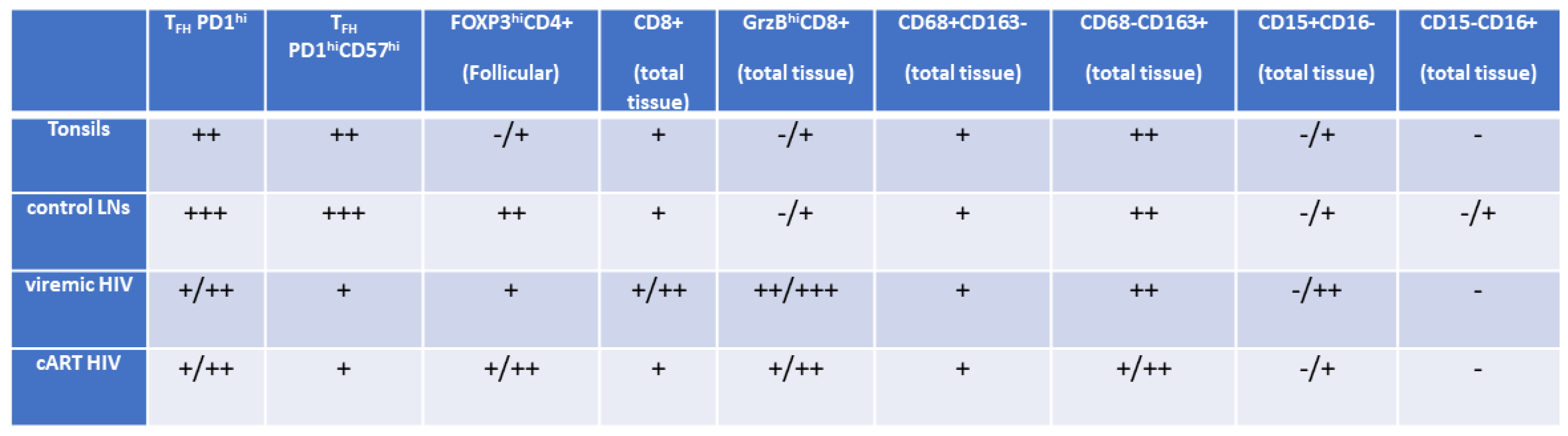

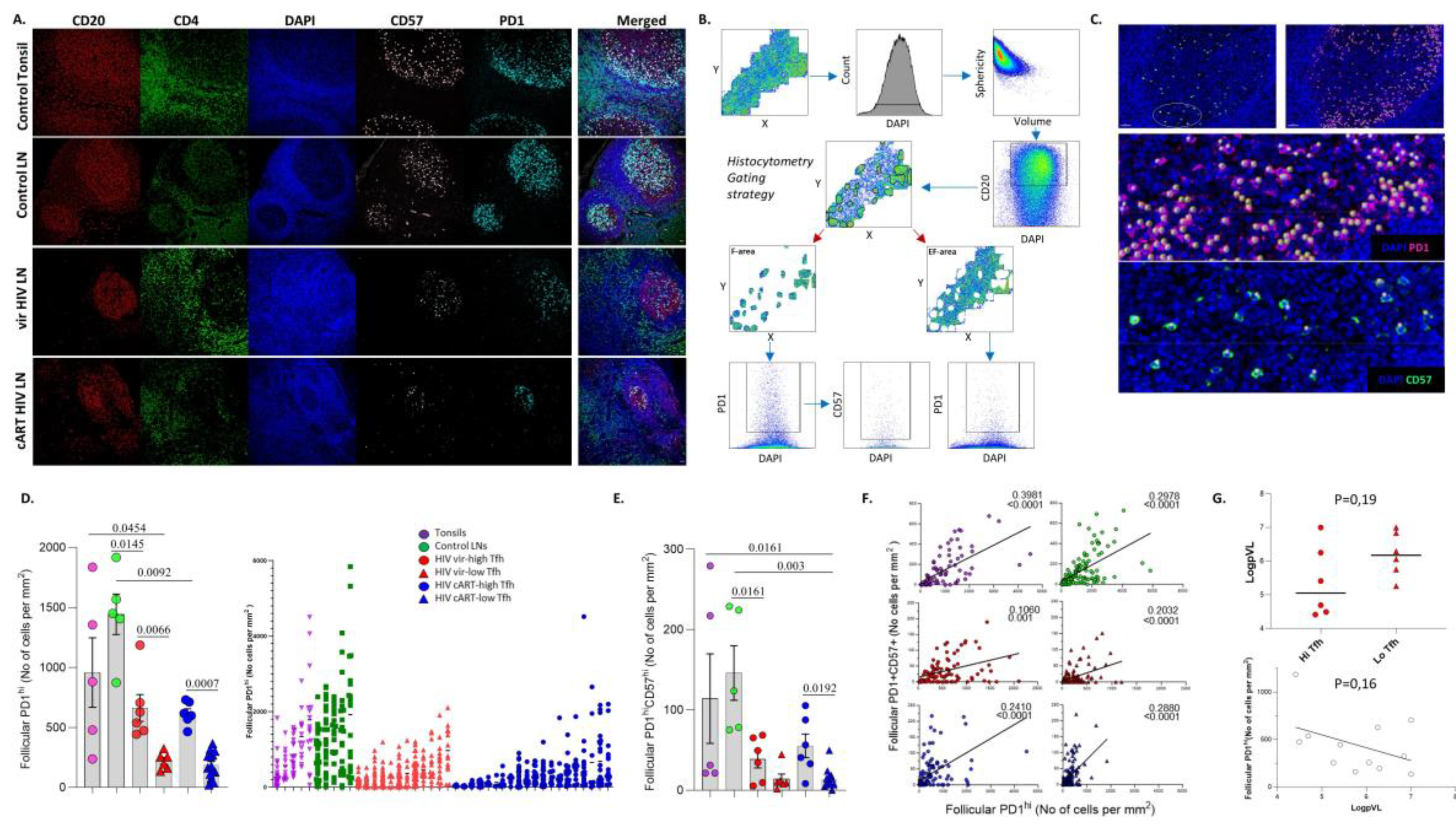

3.1. Similar Profiles of Follicular Helper CD4+ T Cell Densities in Viremic and cART HIV LNs

3.2. A Distinct Positioning Profile of TFH cells in HIV-Infected Compared to Non-Infected Tissues

3.3. Significant Accumulation of Follicular compared to Extrafollicular FOXP3hi CD4+ T Cells in cART low-TFH LNs

3.4. LN GrzBhiCD8+ T Cells Are Negatively Associated with Blood Viral Load

3.5. Differential Modulation of Innate Immune Cell Subsets by cART

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Authorship Contributions

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest

Data Sharing Statement

References

- Dey, B.; Berger, E.A. Towards an HIV cure based on targeted killing of infected cells: different approaches against acute versus chronic infection. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2015, 10, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maldarelli, F. The role of HIV integration in viral persistence: no more whistling past the proviral graveyard. J Clin Invest 2016, 126, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Flora, S.; Serra, D.; Basso, C.; Zanacchi, P. Mechanistic aspects of chromium carcinogenicity. Arch Toxicol Suppl 1989, 13, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dufour, C.; Ruiz, M.J.; Pagliuzza, A.; Richard, C.; Shahid, A.; Fromentin, R.; Ponte, R.; Cattin, A.; Wiche Salinas, T.R.; Salahuddin, S.; et al. Near full-length HIV sequencing in multiple tissues collected postmortem reveals shared clonal expansions across distinct reservoirs during ART. Cell Rep 2023, 42, 113053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estes, J.D. Pathobiology of HIV/SIV-associated changes in secondary lymphoid tissues. Immunol Rev 2013, 254, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudd, P.A.; Minervina, A.A.; Pogorelyy, M.V.; Turner, J.S.; Kim, W.; Kalaidina, E.; Petersen, J.; Schmitz, A.J.; Lei, T.; Haile, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination elicits a robust and persistent T follicular helper cell response in humans. Cell 2022, 185, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noto, A.; Suffiotti, M.; Joo, V.; Mancarella, A.; Procopio, F.A.; Cavet, G.; Leung, Y.; Corpataux, J.M.; Cavassini, M.; Riva, A.; et al. The deficiency in Th2-like Tfh cells affects the maturation and quality of HIV-specific B cell response in viremic infection. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 960120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aid, M.; Dupuy, F.P.; Moysi, E.; Moir, S.; Haddad, E.K.; Estes, J.D.; Sekaly, R.P.; Petrovas, C.; Ribeiro, S.P. Follicular CD4 T Helper Cells As a Major HIV Reservoir Compartment: A Molecular Perspective. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perreau, M.; Savoye, A.L.; De Crignis, E.; Corpataux, J.M.; Cubas, R.; Haddad, E.K.; De Leval, L.; Graziosi, C.; Pantaleo, G. Follicular helper T cells serve as the major CD4 T cell compartment for HIV-1 infection, replication, and production. J Exp Med 2013, 210, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovas, C.; Yamamoto, T.; Gerner, M.Y.; Boswell, K.L.; Wloka, K.; Smith, E.C.; Ambrozak, D.R.; Sandler, N.G.; Timmer, K.J.; Sun, X.; et al. CD4 T follicular helper cell dynamics during SIV infection. J Clin Invest 2012, 122, 3281–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, X.; Malam, N.; Lackner, A.A.; Veazey, R.S. Persistent Simian Immunodeficiency Virus Infection Causes Ultimate Depletion of Follicular Th Cells in AIDS. J Immunol 2015, 195, 4351–4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chirila, T.V.; Russo, A.V.; Constable, I.J. Chemical investigations of ultraviolet-absorbing hydrogel material for soft intraocular lenses. J Cataract Refract Surg 1989, 15, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graff-Dubois, S.; Rouers, A.; Moris, A. Impact of Chronic HIV/SIV Infection on T Follicular Helper Cell Subsets and Germinal Center Homeostasis. Front Immunol 2016, 7, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, B.; Miller, S.M.; Folkvord, J.M.; Kimball, A.; Chamanian, M.; Meditz, A.L.; Arends, T.; McCarter, M.D.; Levy, D.N.; Rakasz, E.G.; et al. Follicular regulatory T cells impair follicular T helper cells in HIV and SIV infection. Nat Commun 2015, 6, 8608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrando-Martinez, S.; Moysi, E.; Pegu, A.; Andrews, S.; Nganou Makamdop, K.; Ambrozak, D.; McDermott, A.B.; Palesch, D.; Paiardini, M.; Pavlakis, G.N.; et al. Accumulation of follicular CD8+ T cells in pathogenic SIV infection. J Clin Invest 2018, 128, 2089–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Xu, W.; Tu, B.; Hong, W.G.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, W.W.; Zhao, M. Alterations of the frequency and functions of follicular regulatory T cells and related mechanisms in HIV infection. J Infect 2020, 81, 776–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luster, A.D. The role of chemokines in linking innate and adaptive immunity. Curr Opin Immunol 2002, 14, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Chan, C.N.; Rovira-Clave, X.; Chen, H.; Bai, Y.; Zhu, B.; McCaffrey, E.; Greenwald, N.F.; Liu, C.; Barlow, G.L.; et al. Combined protein and nucleic acid imaging reveals virus-dependent B cell and macrophage immunosuppression of tissue microenvironments. Immunity 2022, 55, 1118–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banga, R.; Procopio, F.A.; Lana, E.; Gladkov, G.T.; Roseto, I.; Parsons, E.M.; Lian, X.; Armani-Tourret, M.; Bellefroid, M.; Gao, C.; et al. Lymph node dendritic cells harbor inducible replication-competent HIV despite years of suppressive ART. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 1714–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Board, N.L.; Moskovljevic, M.; Wu, F.; Siliciano, R.F.; Siliciano, J.D. Engaging innate immunity in HIV-1 cure strategies. Nat Rev Immunol 2022, 22, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neidleman, J.; Luo, X.; Frouard, J.; Xie, G.; Hsiao, F.; Ma, T.; Morcilla, V.; Lee, A.; Telwatte, S.; Thomas, R.; et al. Phenotypic analysis of the unstimulated in vivo HIV CD4 T cell reservoir. Elife 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, J.M. Keeping the ill at ease. Postgrad Med 1990, 88, 44–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo, P.A.; Levitin, H.M.; Miron, M.; Snyder, M.E.; Senda, T.; Yuan, J.; Cheng, Y.L.; Bush, E.C.; Dogra, P.; Thapa, P.; et al. Single-cell transcriptomics of human T cells reveals tissue and activation signatures in health and disease. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 4706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrovas, C.; Ferrando-Martinez, S.; Gerner, M.Y.; Casazza, J.P.; Pegu, A.; Deleage, C.; Cooper, A.; Hataye, J.; Andrews, S.; Ambrozak, D.; et al. Follicular CD8 T cells accumulate in HIV infection and can kill infected cells in vitro via bispecific antibodies. Sci Transl Med 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moysi, E.; Del Rio Estrada, P.M.; Torres-Ruiz, F.; Reyes-Teran, G.; Koup, R.A.; Petrovas, C. In Situ Characterization of Human Lymphoid Tissue Immune Cells by Multispectral Confocal Imaging and Quantitative Image Analysis; Implications for HIV Reservoir Characterization. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 683396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, K.J.; van der Walt, S.J.; Gommers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J.; et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovell, D.P. Biological importance and statistical significance. J Agric Food Chem 2013, 61, 8340–8348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, B.; Connick, E. TFH in HIV Latency and as Sources of Replication-Competent Virus. Trends Microbiol 2016, 24, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havenar-Daughton, C.; Lee, J.H.; Crotty, S. Tfh cells and HIV bnAbs, an immunodominance model of the HIV neutralizing antibody generation problem. Immunol Rev 2017, 275, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biberfeld, P.; Ost, A.; Porwit, A.; Sandstedt, B.; Pallesen, G.; Bottiger, B.; Morfelt-Mansson, L.; Biberfeld, G. Histopathology and immunohistology of HTLV-III/LAV related lymphadenopathy and AIDS. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand A 1987, 95, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crotty, S. Follicular helper CD4 T cells (TFH). Annu Rev Immunol 2011, 29, 621–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.H.; Rott, L.S.; Clark-Lewis, I.; Campbell, D.J.; Wu, L.; Butcher, E.C. Subspecialization of CXCR5+ T cells: B helper activity is focused in a germinal center-localized subset of CXCR5+ T cells. J Exp Med 2001, 193, 1373–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhan, K.; Moysi, E.; Noto, A.; Chassiakos, A.; Ghneim, K.; Perra, M.M.; Shah, S.; Papaioannou, V.; Fabozzi, G.; Ambrozak, D.R.; et al. Acquisition of optimal TFH cell function is defined by specific molecular, positional, and TCR dynamic signatures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parra, E.R. Methods to Determine and Analyze the Cellular Spatial Distribution Extracted From Multiplex Immunofluorescence Data to Understand the Tumor Microenvironment. Front Mol Biosci 2021, 8, 668340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenchley, J.M.; Price, D.A.; Schacker, T.W.; Asher, T.E.; Silvestri, G.; Rao, S.; Kazzaz, Z.; Bornstein, E.; Lambotte, O.; Altmann, D.; et al. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nat Med 2006, 12, 1365–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, P.W.; Lee, S.A.; Siedner, M.J. Immunologic Biomarkers, Morbidity, and Mortality in Treated HIV Infection. J Infect Dis 2016, 214 Suppl 2, S44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austermann, J.; Roth, J.; Barczyk-Kahlert, K. The Good and the Bad: Monocytes' and Macrophages' Diverse Functions in Inflammation. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeap, W.H.; Wong, K.L.; Shimasaki, N.; Teo, E.C.; Quek, J.K.; Yong, H.X.; Diong, C.P.; Bertoletti, A.; Linn, Y.C.; Wong, S.C. CD16 is indispensable for antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity by human monocytes. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 34310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, E.; Mhaonaigh, A.U.; Wubben, R.; Dwivedi, A.; Hurley, T.; Kelly, L.A.; Stevenson, N.J.; Little, M.A.; Molloy, E.J. Neutrophils: Need for Standardized Nomenclature. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 602963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boritz, E.A.; Darko, S.; Swaszek, L.; Wolf, G.; Wells, D.; Wu, X.; Henry, A.R.; Laboune, F.; Hu, J.; Ambrozak, D.; et al. Multiple Origins of Virus Persistence during Natural Control of HIV Infection. Cell 2016, 166, 1004–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doitsh, G.; Cavrois, M.; Lassen, K.G.; Zepeda, O.; Yang, Z.; Santiago, M.L.; Hebbeler, A.M.; Greene, W.C. Abortive HIV infection mediates CD4 T cell depletion and inflammation in human lymphoid tissue. Cell 2010, 143, 789–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, M.; Smith, A.J.; Wietgrefe, S.W.; Southern, P.J.; Schacker, T.W.; Reilly, C.S.; Estes, J.D.; Burton, G.F.; Silvestri, G.; Lifson, J.D.; et al. Cumulative mechanisms of lymphoid tissue fibrosis and T cell depletion in HIV-1 and SIV infections. J Clin Invest 2011, 121, 998–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.Q.; Schuler, T.; Cavert, W.; Notermans, D.W.; Gebhard, K.; Henry, K.; Havlir, D.V.; Gunthard, H.F.; Wong, J.K.; Little, S.; et al. Reversibility of the pathological changes in the follicular dendritic cell network with treatment of HIV-1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999, 96, 5169–5172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvez, C.; Urrea, V.; Dalmau, J.; Jimenez, M.; Clotet, B.; Monceaux, V.; Huot, N.; Leal, L.; Gonzalez-Soler, V.; Gonzalez-Cao, M.; et al. Extremely low viral reservoir in treated chronically HIV-1-infected individuals. EBioMedicine 2020, 57, 102830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, M.; Southern, P.J.; Reilly, C.S.; Beilman, G.J.; Chipman, J.G.; Schacker, T.W.; Haase, A.T. Lymphoid tissue damage in HIV-1 infection depletes naive T cells and limits T cell reconstitution after antiretroviral therapy. PLoS Pathog 2012, 8, e1002437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumjohann, D.; Preite, S.; Reboldi, A.; Ronchi, F.; Ansel, K.M.; Lanzavecchia, A.; Sallusto, F. Persistent antigen and germinal center B cells sustain T follicular helper cell responses and phenotype. Immunity 2013, 38, 596–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayin, I.; Radtke, A.J.; Vella, L.A.; Jin, W.; Wherry, E.J.; Buggert, M.; Betts, M.R.; Herati, R.S.; Germain, R.N.; Canaday, D.H. Spatial distribution and function of T follicular regulatory cells in human lymph nodes. J Exp Med 2018, 215, 1531–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, A.; Del Rio Estrada, P.M.; Tharp, G.K.; Trible, R.P.; Amara, R.R.; Chahroudi, A.; Reyes-Teran, G.; Bosinger, S.E.; Silvestri, G. Decreased T Follicular Regulatory Cell/T Follicular Helper Cell (TFH) in Simian Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Rhesus Macaques May Contribute to Accumulation of TFH in Chronic Infection. J Immunol 2015, 195, 3237–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amodio, D.; Cotugno, N.; Macchiarulo, G.; Rocca, S.; Dimopoulos, Y.; Castrucci, M.R.; De Vito, R.; Tucci, F.M.; McDermott, A.B.; Narpala, S.; et al. Quantitative Multiplexed Imaging Analysis Reveals a Strong Association between Immunogen-Specific B Cell Responses and Tonsillar Germinal Center Immune Dynamics in Children after Influenza Vaccination. J Immunol 2018, 200, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, J.T.; Hu, W.; TB, R.C.; Solem, S.; Galante, A.; Lin, Z.; Allon, S.J.; Mesin, L.; Bilate, A.M.; Schiepers, A.; et al. Expression of Foxp3 by T follicular helper cells in end-stage germinal centers. Science 2021, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brainard, D.M.; Tager, A.M.; Misdraji, J.; Frahm, N.; Lichterfeld, M.; Draenert, R.; Brander, C.; Walker, B.D.; Luster, A.D. Decreased CXCR3+ CD8 T cells in advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection suggest that a homing defect contributes to cytotoxic T-lymphocyte dysfunction. J Virol 2007, 81, 8439–8450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, D.R.; Gaiha, G.D.; Walker, B.D. CD8(+) T cells in HIV control, cure and prevention. Nat Rev Immunol 2020, 20, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Policicchio, B.B.; Cardozo-Ojeda, E.F.; Xu, C.; Ma, D.; He, T.; Raehtz, K.D.; Sivanandham, R.; Kleinman, A.J.; Perelson, A.S.; Apetrei, C.; et al. CD8(+) T cells control SIV infection using both cytolytic effects and non-cytolytic suppression of virus production. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 6657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, B.; Miller, S.M.; Folkvord, J.M.; Levy, D.N.; Rakasz, E.G.; Skinner, P.J.; Connick, E. Follicular Regulatory CD8 T Cells Impair the Germinal Center Response in SIV and Ex Vivo HIV Infection. PLoS Pathog 2016, 12, e1005924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pilato, M.; Palomino-Segura, M.; Mejias-Perez, E.; Gomez, C.E.; Rubio-Ponce, A.; D'Antuono, R.; Pizzagalli, D.U.; Perez, P.; Kfuri-Rubens, R.; Benguria, A.; et al. Neutrophil subtypes shape HIV-specific CD8 T-cell responses after vaccinia virus infection. NPJ Vaccines 2021, 6, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).