Submitted:

13 June 2025

Posted:

16 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Populations

2.2. Multicolor Phenotyping Analysis of Surface Markers

2.3. Mitochondrial Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Basic Demographic and Immune Parameters of the Studied Groups

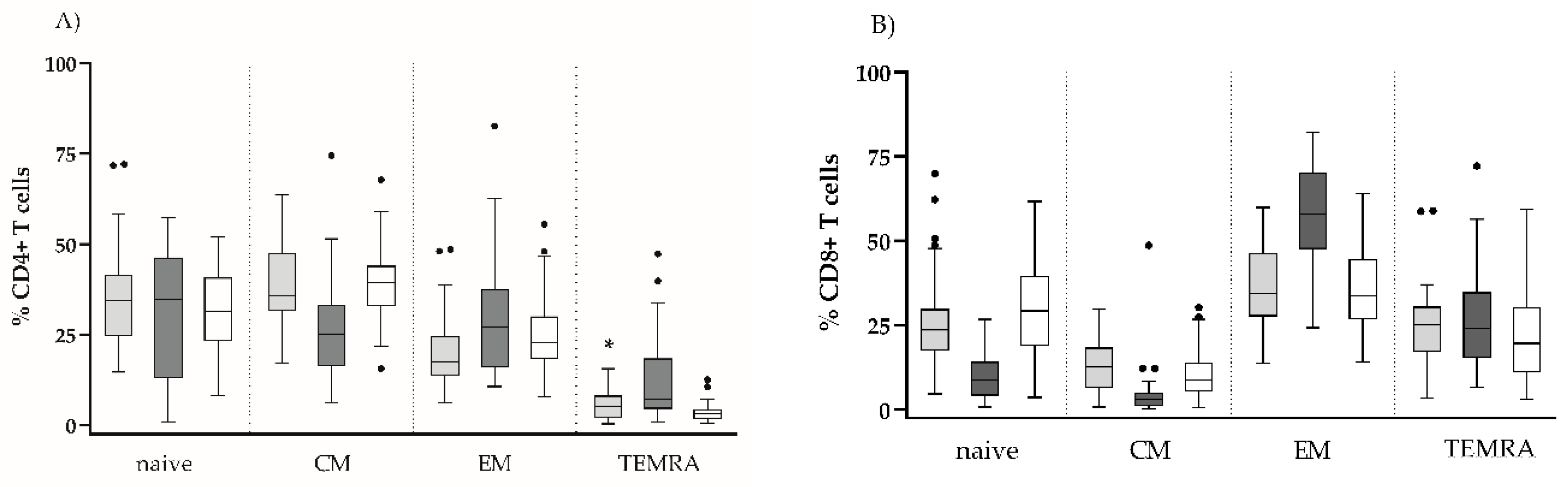

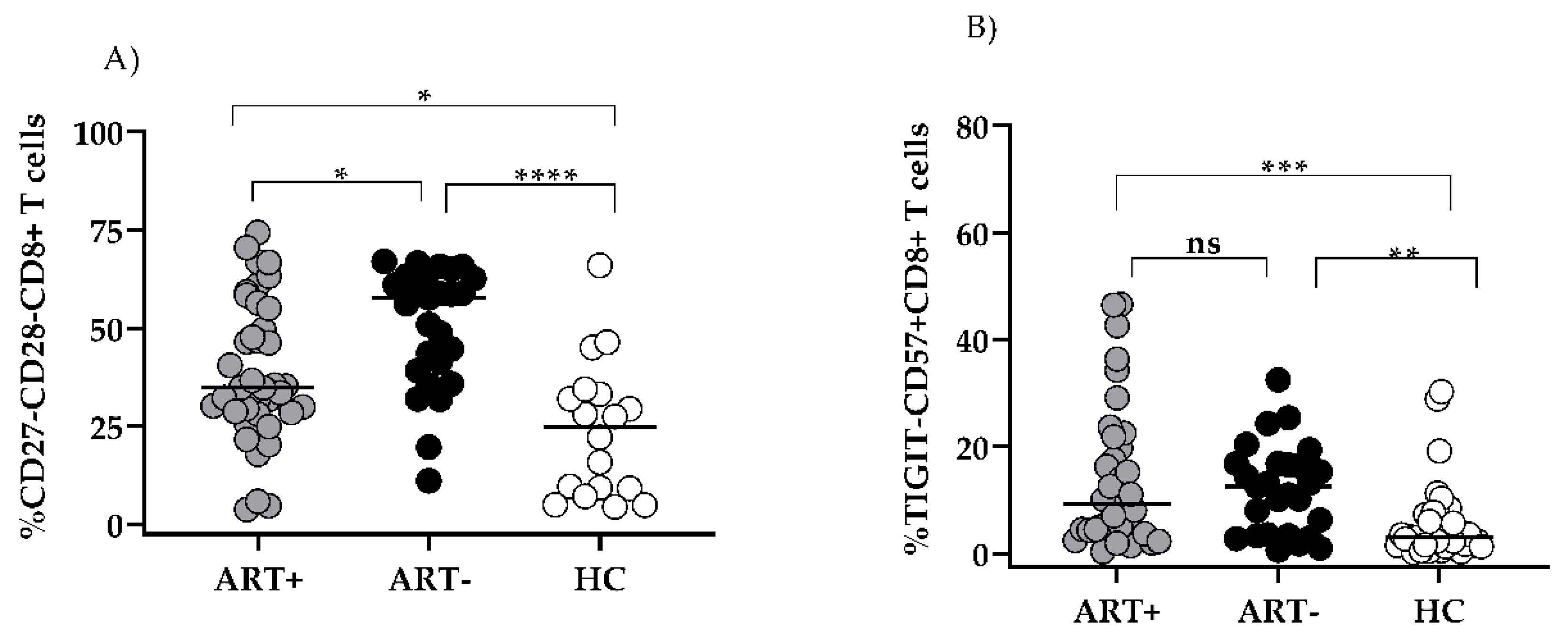

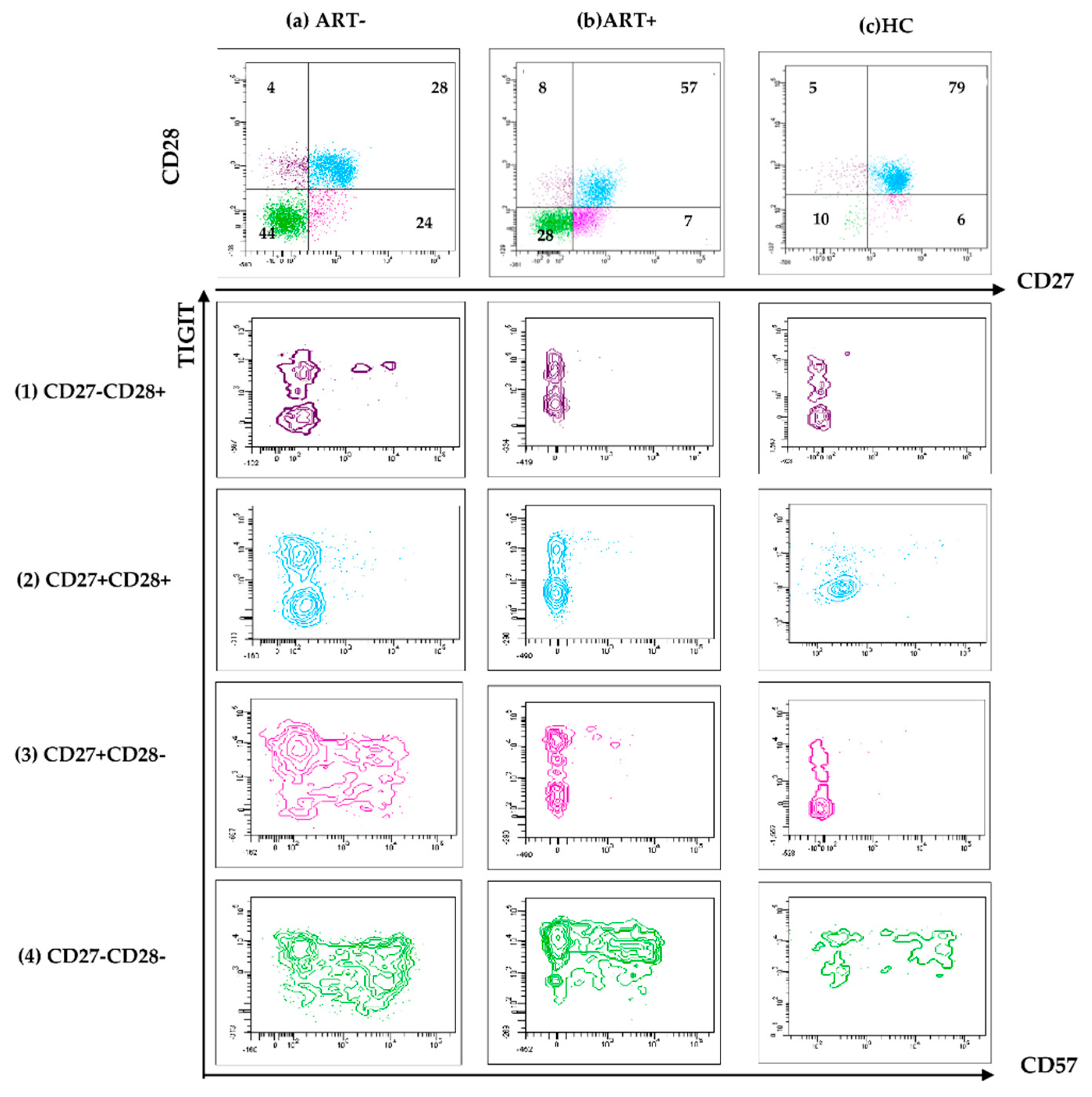

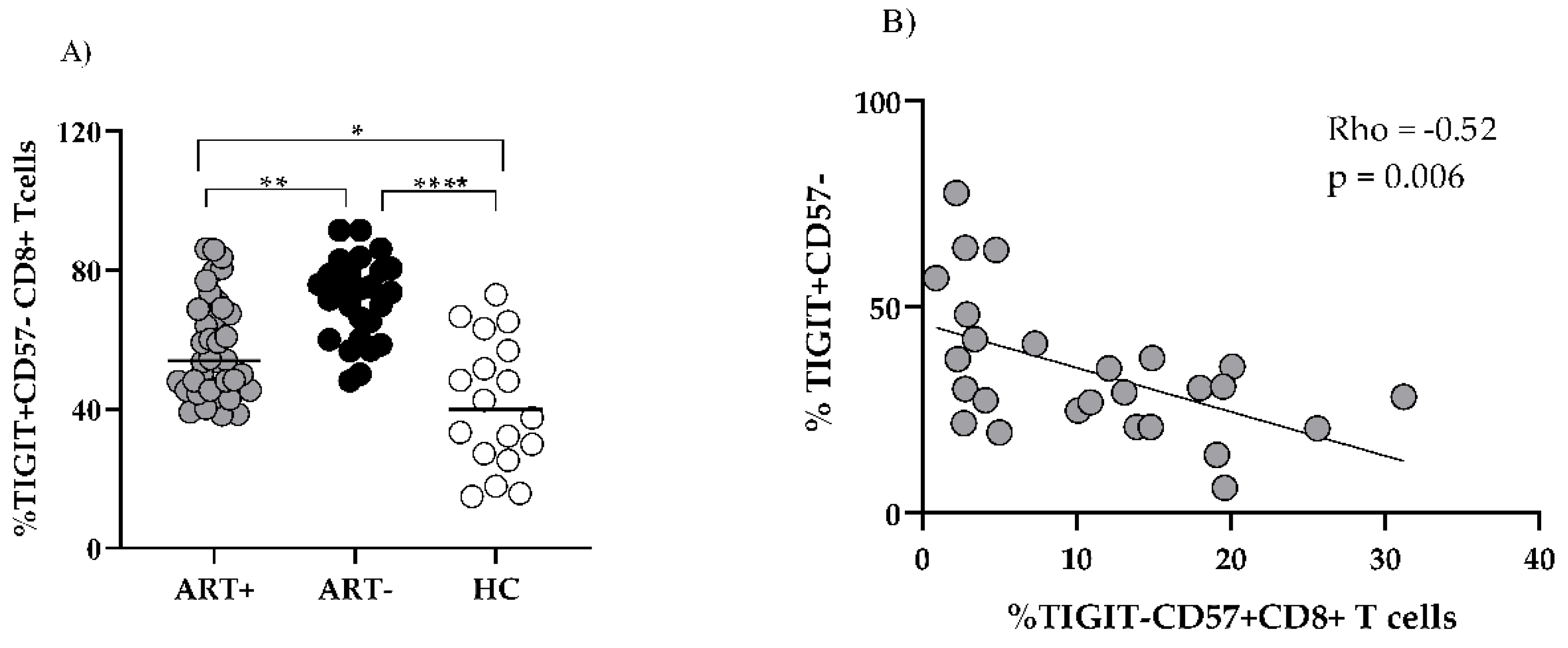

3.2. Expression of Activation, Exhaustion and Senescence Markers by CD4 and CD8 T Cells of PLHIV on Successful ART

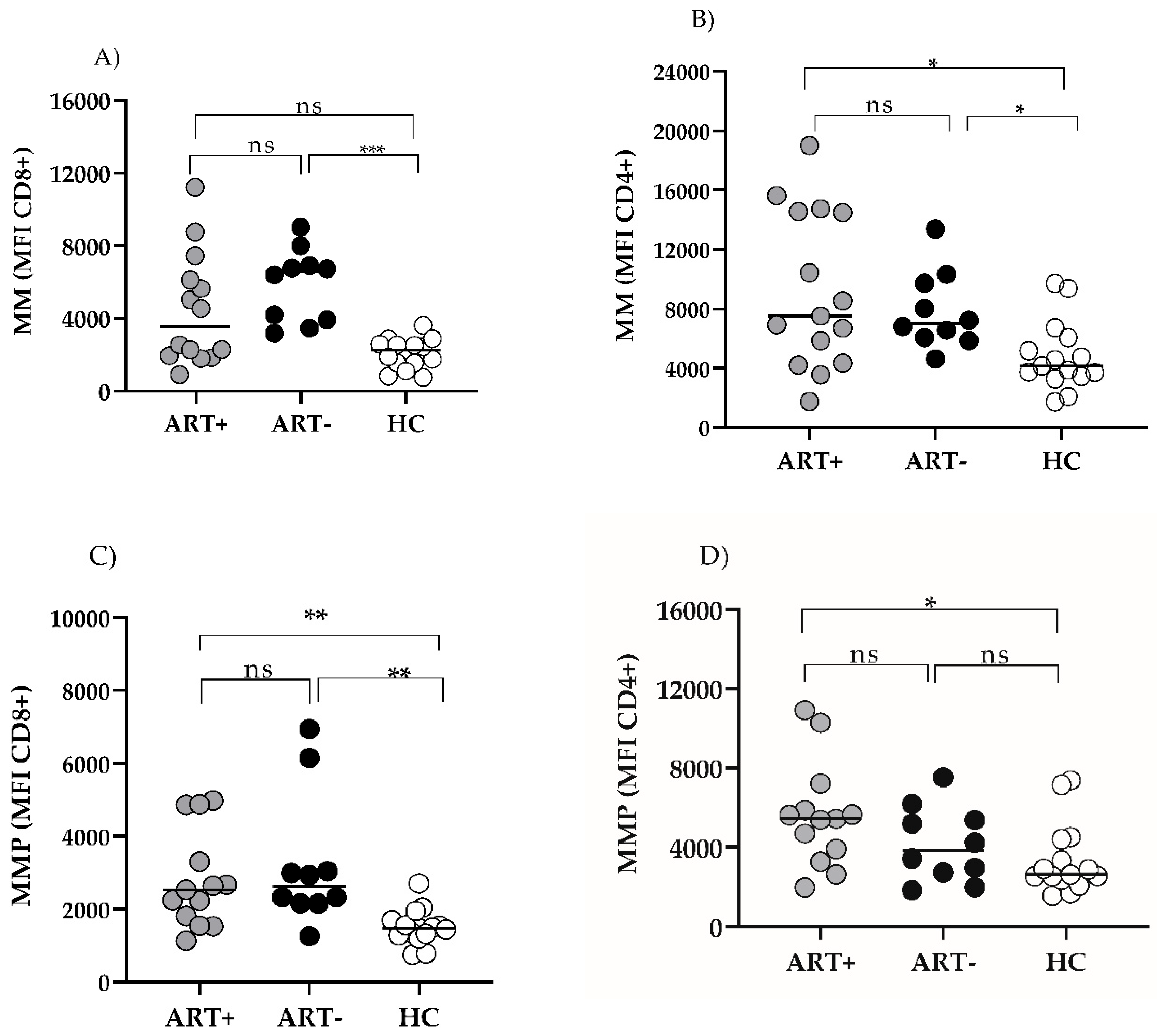

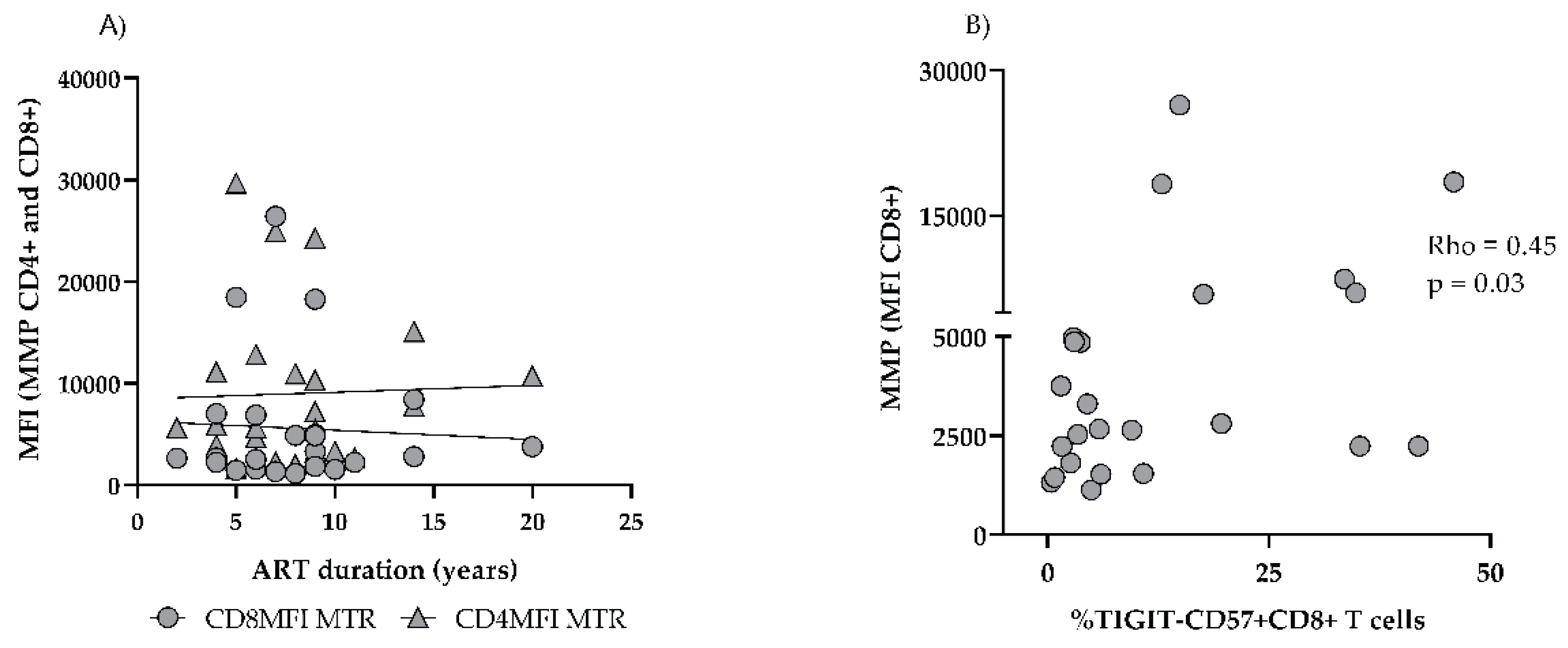

3.3. Mitochondrial Function in CD4 and CD8 T Cells of PLHIV on Successful ART

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ART | Contemporary antiretroviral therapy |

| PLHIV | People living with HIV |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency viruses |

| AIDS | Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome |

| ARV | Antiretroviral drugs |

| NRTIs | Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors |

| NNRTIs | Non-nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors |

References

- Bloch, M.; John, M.; Smith, D.; Rasmussen, T.A.; Wright, E. Managing HIV-associated inflammation and ageing in the era of modern ART. HIV Med 2020, 21 (Suppl 3), 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano-Villar, S.; Gutierrez, C.; Vallejo, A.; Hernandez-Novoa, B.; Diaz, L.; Abad Fernandez, M.; Madrid, N.; Dronda, F.; Zamora, J.; Munoz-Fernandez, M.A.; et al. The CD4/CD8 ratio in HIV-infected subjects is independently associated with T-cell activation despite long-term viral suppression. J Infect 2013, 66, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streeck, H.; Maestri, A.; Habermann, D.; Crowell, T.A.; Esber, A.L.; Son, G.; Eller, L.A.; Eller, M.A.; Parikh, A.P.; Horn, P.A.; et al. Dissecting drivers of immune activation in chronic HIV-1 infection. EBioMedicine 2022, 83, 104182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gergen, M.; Hewitt, A.; Sanger, C.B.; Striker, R. Monitoring immune recovery on HIV therapy: Critical, helpful, or waste of money in the current era? AIDS 2024, 38, 937–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okulicz, J.F.; Le, T.D.; Agan, B.K.; Camargo, J.F.; Landrum, M.L.; Wright, E.; Dolan, M.J.; Ganesan, A.; Ferguson, T.M.; Smith, D.M.; et al. Influence of the timing of antiretroviral therapy on the potential for normalization of immune status in human immunodeficiency virus 1-infected individuals. JAMA Intern Med 2015, 175, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ron, R.; Moreno, E.; Martinez-Sanz, J.; Branas, F.; Sainz, T.; Moreno, S.; Serrano-Villar, S. CD4/CD8 Ratio During Human Immunodeficiency Virus Treatment: Time for Routine Monitoring? Clin Infect Dis 2023, 76, 1688–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppe, J.P.; Desprez, P.Y.; Krtolica, A.; Campisi, J. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype: The dark side of tumor suppression. Annu Rev Pathol 2010, 5, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelbrunn, M.; Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of T cell aging. Nat Immunol 2021, 22, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubser, C.; Chiu, C.; Lewin, S.R.; Rasmussen, T.A. Immune checkpoint blockade in HIV. EBioMedicine 2022, 76, 103840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yero, A.; Shi, T.; Farnos, O.; Routy, J.P.; Tremblay, C.; Durand, M.; Tsoukas, C.; Costiniuk, C.T.; Jenabian, M.A. Dynamics and epigenetic signature of regulatory T-cells following antiretroviral therapy initiation in acute HIV infection. EBioMedicine 2021, 71, 103570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias Junior, E.; Gubert, V.T.; Bonin-Jacob, C.M.; Puga, M.A.M.; Gouveia, C.G.; Sichinel, A.H.; Tozetti, I.A. CD57 T cells associated with immunosenescence in adults living with HIV or AIDS. Immunology 2024, 171, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, C.; Jiang, X. The role of mitochondria in aging, cell death, and tumor immunity. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1520072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundgren, J.D.; Borges, A.H.; Neaton, J.D. Serious Non-AIDS Conditions in HIV: Benefit of Early ART. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2018, 15, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schank, M.; Zhao, J.; Moorman, J.P.; Yao, Z.Q. The Impact of HIV- and ART-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Cellular Senescence and Aging. Cells 2021, 10, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaunzaran-Zamudio, P.F.; Naranjo, L.; Caro-Vega, Y.; Castillo-Mancilla, J.R.; Camiro-Zuniga, A.; Fuentes-Garcia, R.; Crabtree-Ramirez, B.E.; Sierra-Madero, J.G. Incomplete Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence Is Associated with Lower CD4-CD8 Ratio in Virally Suppressed Patients with HIV Infection in Mexico. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2023, 39, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantz-Naeem, N.; Bottcher-Loschinski, R.; Borucki, K.; Mitchell-Flack, M.; Bottcher, M.; Schraven, B.; Mougiakakos, D.; Kahlfuss, S. TIGIT signaling and its influence on T cell metabolism and immune cell function in the tumor microenvironment. Front Oncol 2023, 13, 1060112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R.J.; Comps-Agrar, L.; Hackney, J.; Yu, X.; Huseni, M.; Yang, Y.; Park, S.; Javinal, V.; Chiu, H.; Irving, B.; et al. The immunoreceptor TIGIT regulates antitumor and antiviral CD8(+) T cell effector function. Cancer Cell 2014, 26, 923–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvin, J.M.; Pagliano, O.; Fourcade, J.; Sun, Z.; Wang, H.; Sander, C.; Kirkwood, J.M.; Chen, T.H.; Maurer, M.; Korman, A.J.; et al. TIGIT and PD-1 impair tumor antigen-specific CD8(+) T cells in melanoma patients. J Clin Invest 2015, 125, 2046–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, G.M.; Fujita, T.; Webb, G.M.; Burwitz, B.J.; Wu, H.L.; Reed, J.S.; Hammond, K.B.; Clayton, K.L.; Ishii, N.; Abdel-Mohsen, M.; et al. TIGIT Marks Exhausted T Cells, Correlates with Disease Progression, and Serves as a Target for Immune Restoration in HIV and SIV Infection. PLoS Pathog 2016, 12, e1005349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomont, N.; El-Far, M.; Ancuta, P.; Trautmann, L.; Procopio, F.A.; Yassine-Diab, B.; Boucher, G.; Boulassel, M.R.; Ghattas, G.; Brenchley, J.M.; et al. HIV reservoir size and persistence are driven by T cell survival and homeostatic proliferation. Nat Med 2009, 15, 893–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvet-Mirabent, M.; Sanchez-Cerrillo, I.; Martin-Cofreces, N.; Martinez-Fleta, P.; de la Fuente, H.; Tsukalov, I.; Delgado-Arevalo, C.; Calzada, M.J.; de Los Santos, I.; Sanz, J.; et al. Antiretroviral therapy duration and immunometabolic state determine efficacy of ex vivo dendritic cell-based treatment restoring functional HIV-specific CD8+ T cells in people living with HIV. EBioMedicine 2022, 81, 104090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strioga, M.; Pasukoniene, V.; Characiejus, D. CD8+ CD28- and CD8+ CD57+ T cells and their role in health and disease. Immunology 2011, 134, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.C.; Hwu, P.; Radvanyi, L.G. New insights on the role of CD8(+)CD57(+) T-cells in cancer. Oncoimmunology 2012, 1, 954–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoji, A.; Connolly, N.C.; Buchanan, W.G.; Rinaldo, C.R., Jr. CD27 and CD57 expression reveals atypical differentiation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific memory CD8+ T cells. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2007, 14, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.A.; Sinclair, E.; Hatano, H.; Hsue, P.Y.; Epling, L.; Hecht, F.M.; Bangsberg, D.R.; Martin, J.N.; McCune, J.M.; Deeks, S.G.; et al. Impact of HIV on CD8+ T cell CD57 expression is distinct from that of CMV and aging. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cencioni, M.T.; Magliozzi, R.; Nicholas, R.; Ali, R.; Malik, O.; Reynolds, R.; Borsellino, G.; Battistini, L.; Muraro, P.A. Programmed death 1 is highly expressed on CD8(+) CD57(+) T cells in patients with stable multiple sclerosis and inhibits their cytotoxic response to Epstein-Barr virus. Immunology 2017, 152, 660–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Jeong, I.; Joh, J.S.; Jung, Y.W.; Sim, S.Y.; Choi, B.; Jee, H.G.; Lim, D.G. Differential expression of CD57 in antigen-reactive CD4+ T cells between active and latent tuberculosis infection. Clin Immunol 2015, 159, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albareda, M.C.; Laucella, S.A. Modulation of Trypanosoma cruzi-specific T-cell responses after chemotherapy for chronic Chagas disease. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2015, 110, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arguello, R.J.; Albareda, M.C.; Alvarez, M.G.; Bertocchi, G.; Armenti, A.H.; Vigliano, C.; Meckert, P.C.; Tarleton, R.L.; Laucella, S.A. Inhibitory receptors are expressed by Trypanosoma cruzi-specific effector T cells and in hearts of subjects with chronic Chagas disease. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, N.; Takaku, T.; Takeda, K.; Shirane, S.; Toyota, T.; Koike, M.; Noguchi, M.; Hirano, T.; Fujiwara, H.; Komatsu, N. Dasatinib-induced anti-leukemia cellular immunity through a novel subset of CD57 positive helper/cytotoxic CD4 T cells in chronic myelogenous leukemia patients. Int J Hematol 2018, 108, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Hao, Y.; Zhao, H.; Xiao, J.; Han, N.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, G.; Chong, X.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, F. Distinct Mitochondrial Disturbance in CD4+T and CD8+T Cells From HIV-Infected Patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017, 74, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callender, L.A.; Carroll, E.C.; Bober, E.A.; Akbar, A.N.; Solito, E.; Henson, S.M. Mitochondrial mass governs the extent of human T cell senescence. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, J.J.R.; Murphy, A.J.; Lee, M.K.S.; Ostrowski, M.; Crowe, S.M.; Palmer, C.S. Assessment of metabolic and mitochondrial dynamics in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in virologically suppressed HIV-positive individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrovas, C.; Mueller, Y.M.; Dimitriou, I.D.; Altork, S.R.; Banerjee, A.; Sklar, P.; Mounzer, K.C.; Altman, J.D.; Katsikis, P.D. Increased mitochondrial mass characterizes the survival defect of HIV-specific CD8(+) T cells. Blood 2007, 109, 2505–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternfeld, T.; Tischleder, A.; Schuster, M.; Bogner, J.R. Mitochondrial membrane potential and apoptosis of blood mononuclear cells in untreated HIV-1 infected patients. HIV Med 2009, 10, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, S.; Grefte, S.; van de Westerlo, E.; Lauwen, S.; Paters, A.; Prehn, J.H.M.; Gan, Z.; Keijer, J.; Adjobo-Hermans, M.J.W.; Koopman, W.J.H. Performance of TMRM and Mitotrackers in mitochondrial morphofunctional analysis of primary human skin fibroblasts. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg 2024, 1865, 149027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matarrese, P.; Gambardella, L.; Cassone, A.; Vella, S.; Cauda, R.; Malorni, W. Mitochondrial membrane hyperpolarization hijacks activated T lymphocytes toward the apoptotic-prone phenotype: Homeostatic mechanisms of HIV protease inhibitors. J Immunol 2003, 170, 6006–6015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gergely, P., Jr.; Niland, B.; Gonchoroff, N.; Pullmann, R., Jr.; Phillips, P.E.; Perl, A. Persistent mitochondrial hyperpolarization, increased reactive oxygen intermediate production, and cytoplasmic alkalinization characterize altered IL-10 signaling in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol 2002, 169, 1092–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarrese, P.; Di Biase, L.; Santodonato, L.; Straface, E.; Mecchia, M.; Ascione, B.; Parmiani, G.; Belardelli, F.; Ferrantini, M.; Malorni, W. Type I interferon gene transfer sensitizes melanoma cells to apoptosis via a target activity on mitochondrial function. Am J Pathol 2002, 160, 1507–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, L.; Desquiret-Dumas, V.; Nagot, N.; Rapenne, C.; Van de Perre, P.; Reynier, P.; Moles, J.P. Long-term persistence of mitochondrial dysfunctions after viral infections and antiviral therapies: A review of mechanisms involved. J Med Virol 2024, 96, e29886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | A (HIV+ART+) |

B (HIV+ART-) |

HC | p1 | p2 | p3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M/F (n) |

26/13 | 22/5 | 21/14 | ns | ns | ns |

| Age (years) |

45 (34–51) |

40 (32–48) |

37 (29–45.5) |

ns | ns | ns |

| CD4 T AC (Cells/µL) |

856 (711–1224) |

302 (136–527) |

902 (784–1334) |

**** | ns | **** |

| CD8 T AC (Cells/µL) |

702 (528–878) |

965 (441–1221) |

505 (405–731) |

ns | ns | ** |

| CD4/CD8 Ratio | 1.31 (1.13–1.71) |

0.31 (0.19–45) |

1.8 (1.5–2.21) |

**** | ns | **** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).