Submitted:

12 July 2024

Posted:

14 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Arduino-Based Sensor Systems

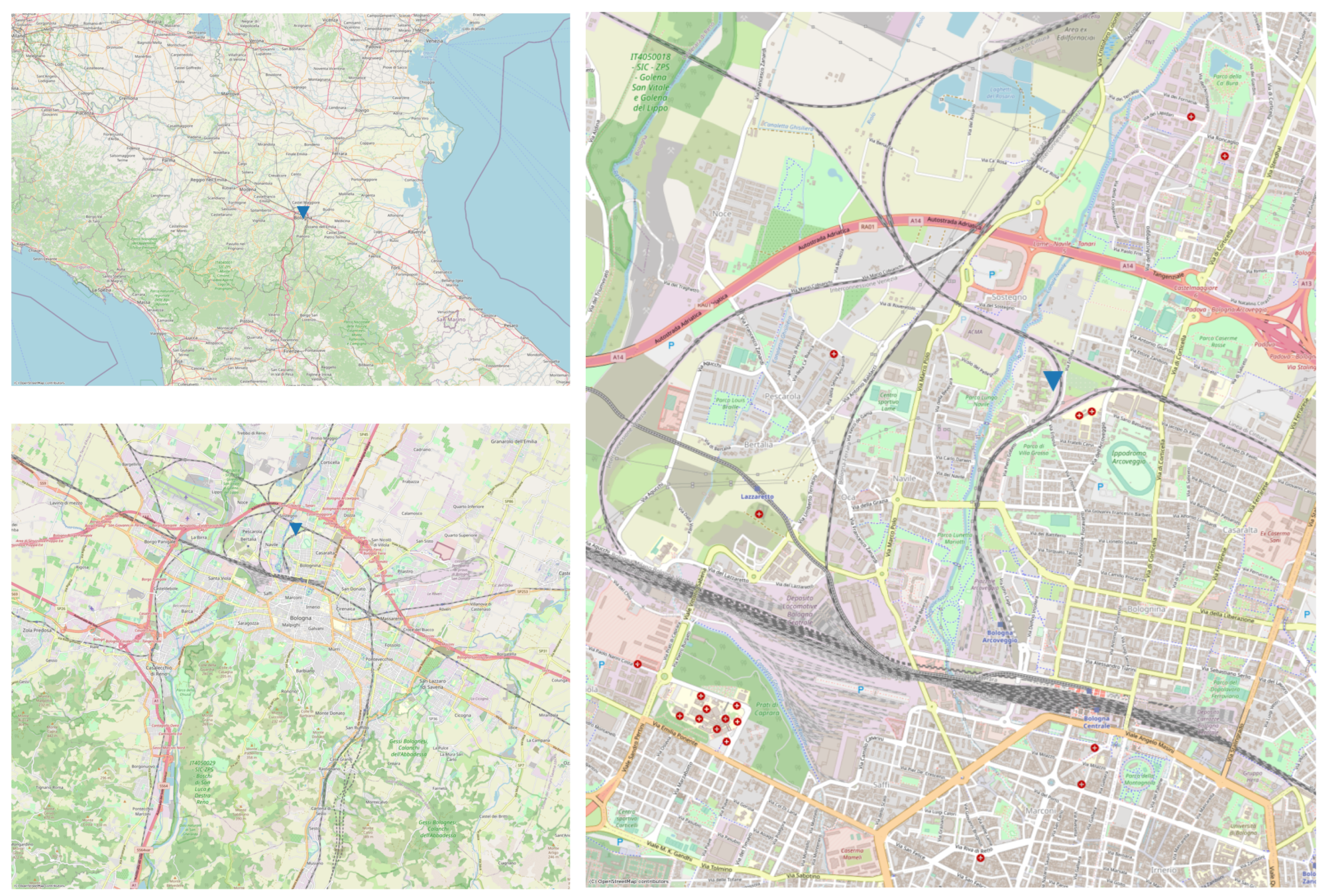

2.2. Measurement Site and Reference Instrumentation

2.3. Measurement Campaign with Sensors Arrangement

- A good coupling with ambient air and a proper exposition to external conditions

- Avoidance of exposure to direct sunlight or external heat sources

2.4. Methods Used to Acquire and Manipulate Data

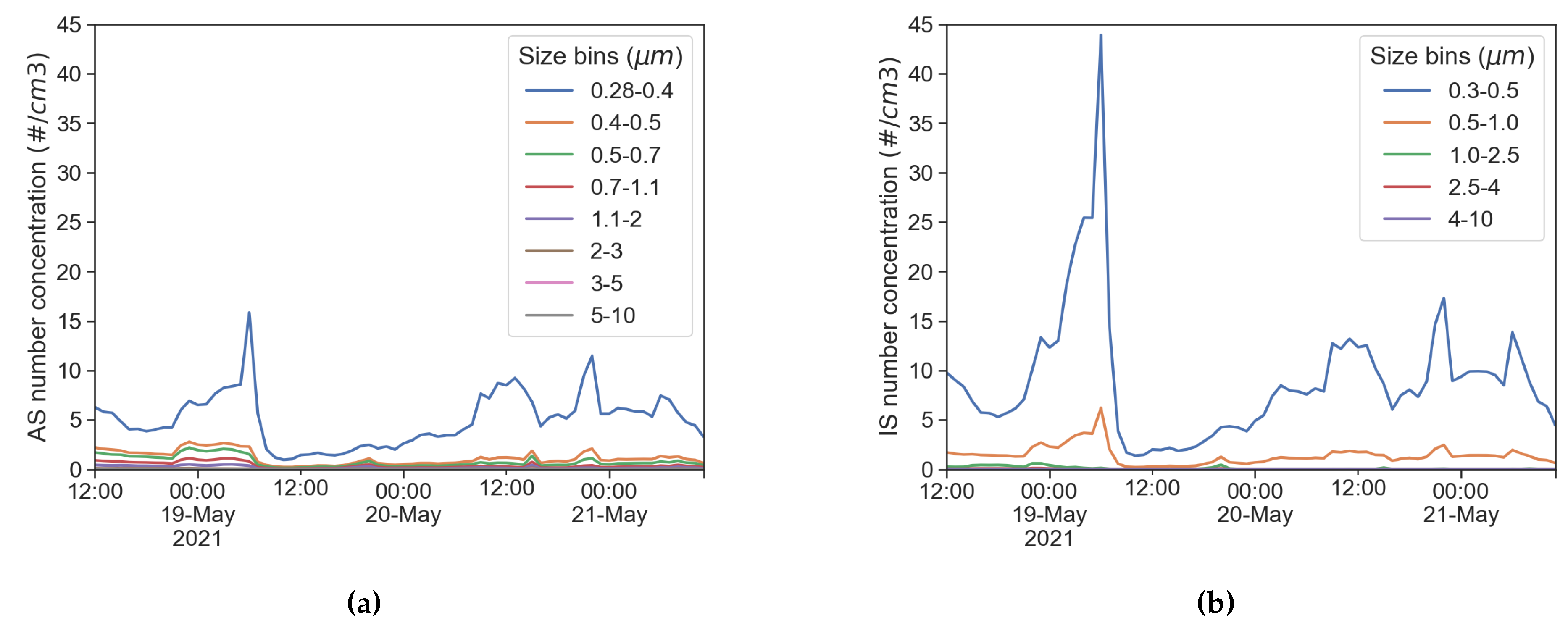

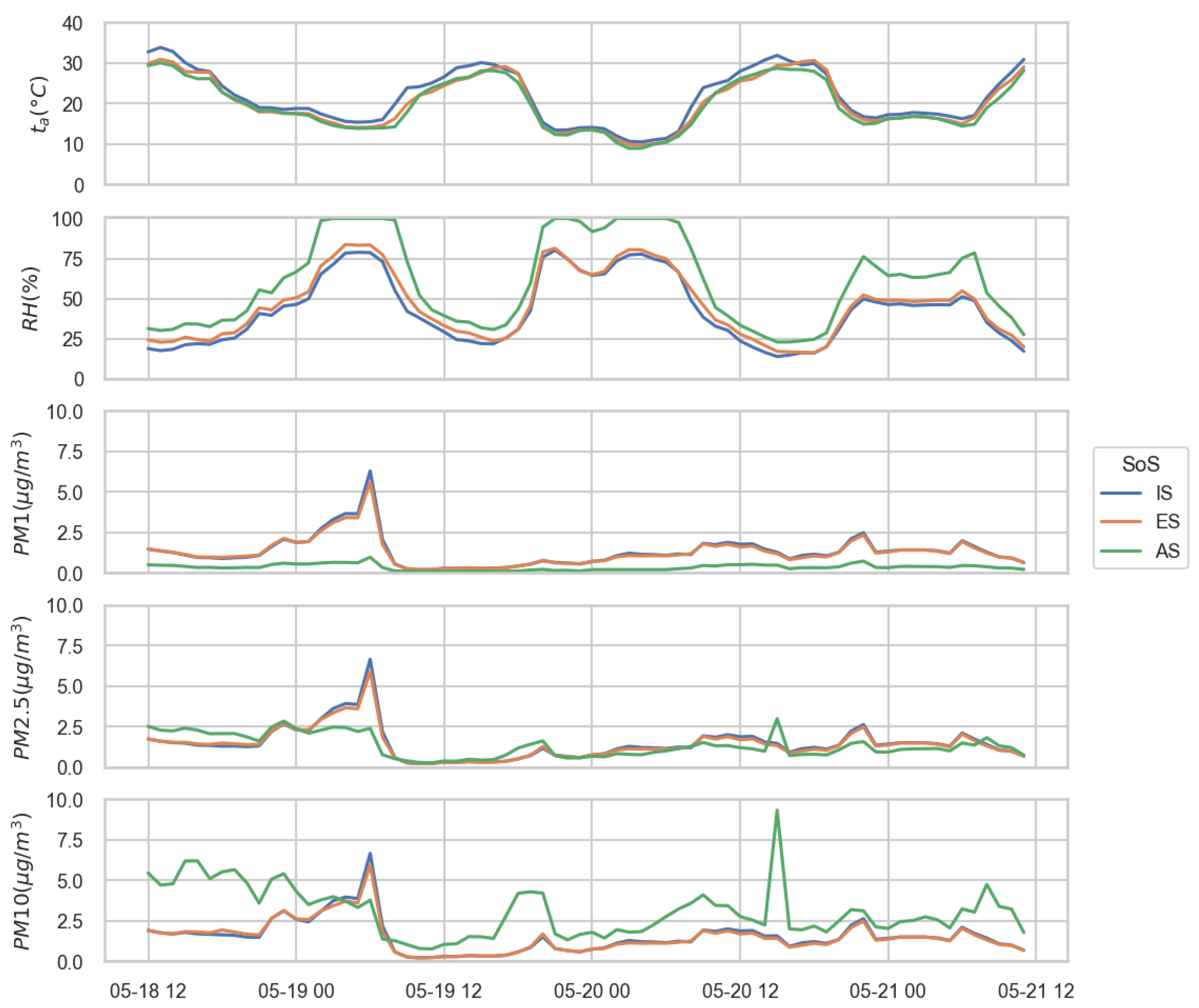

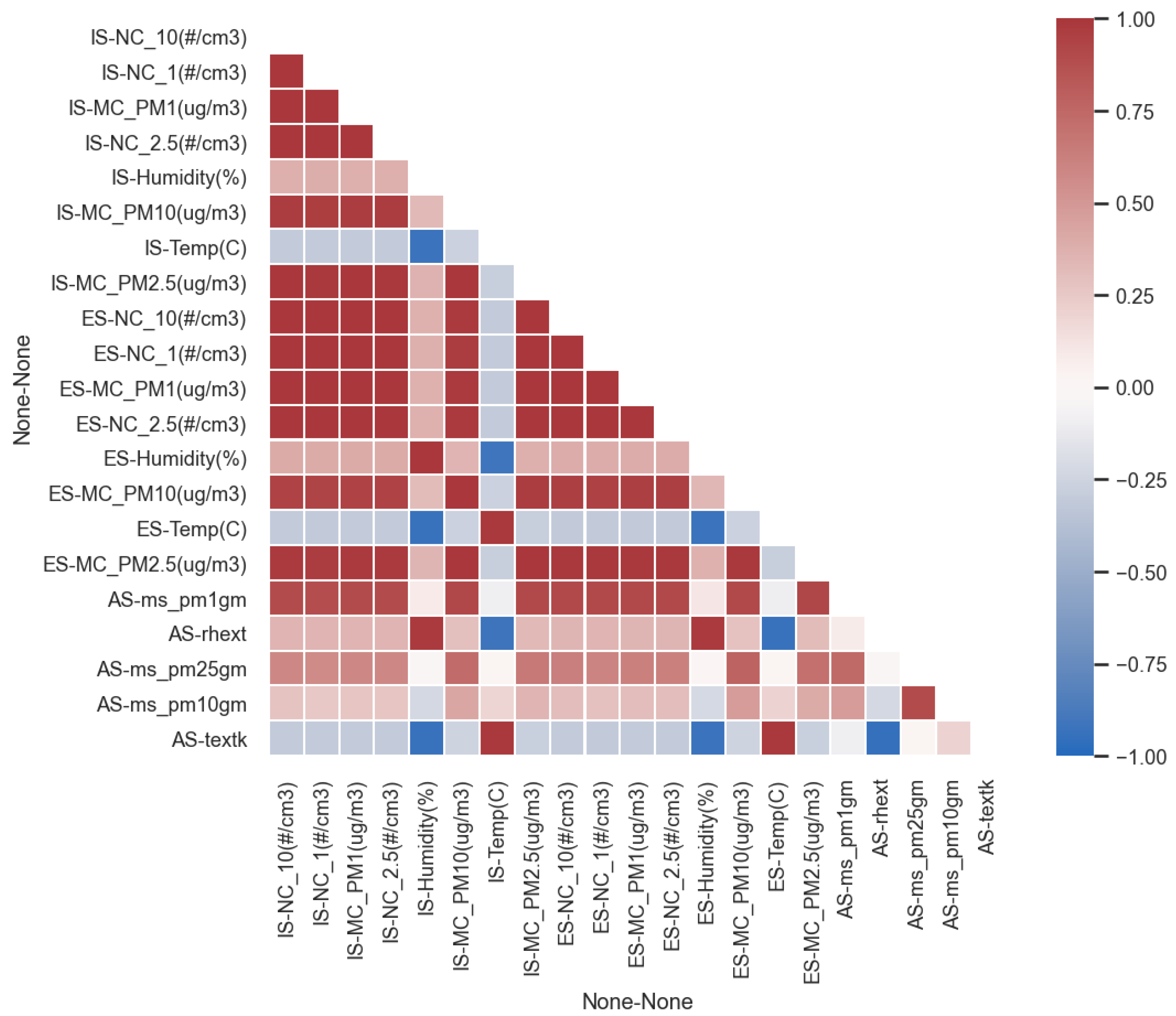

3. Results

3.1. Time Granularity

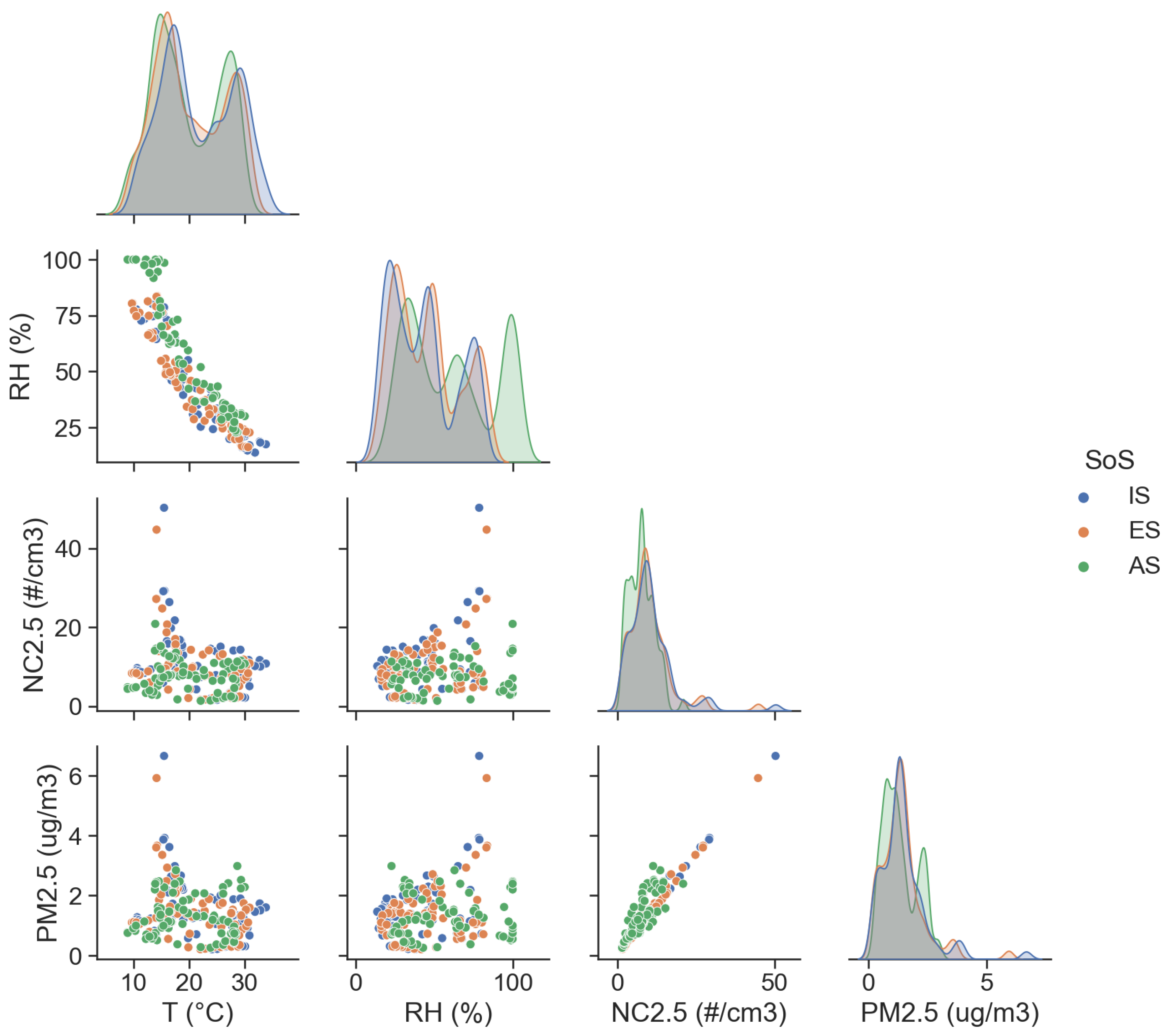

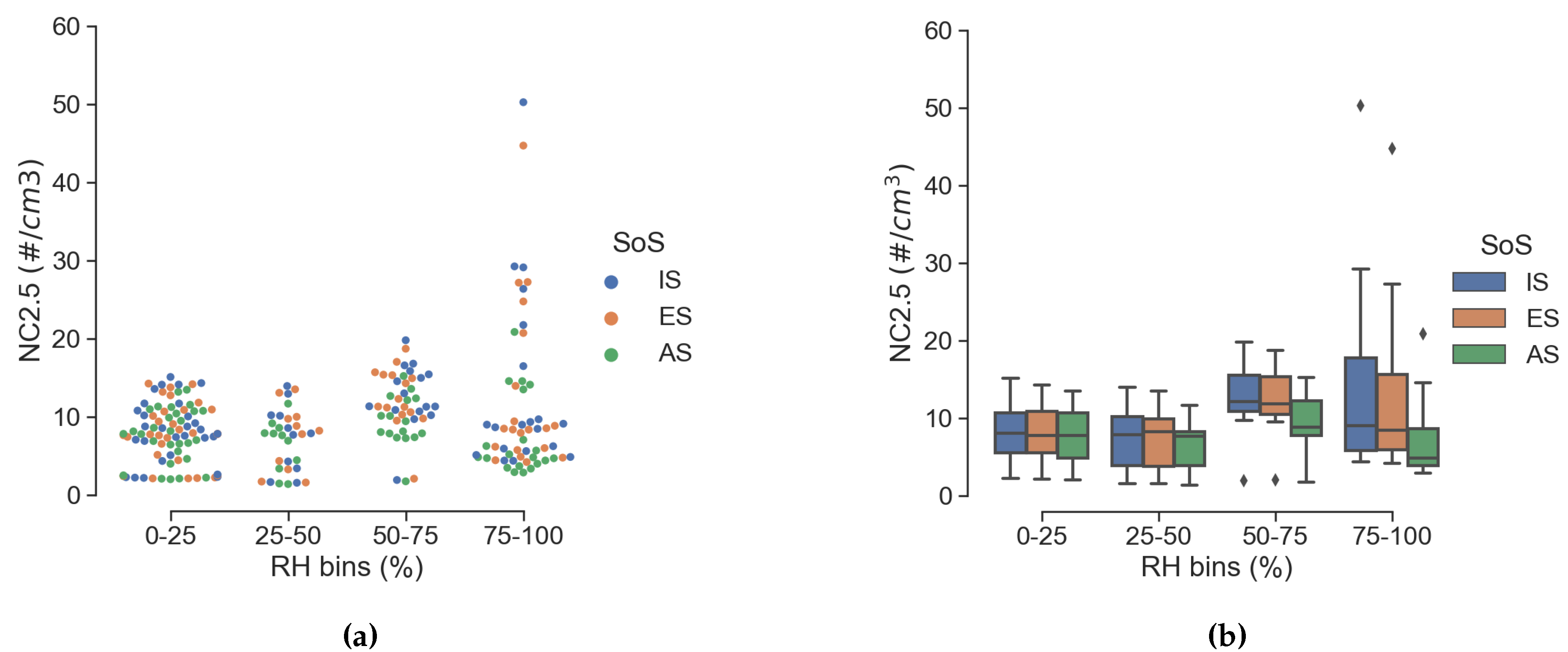

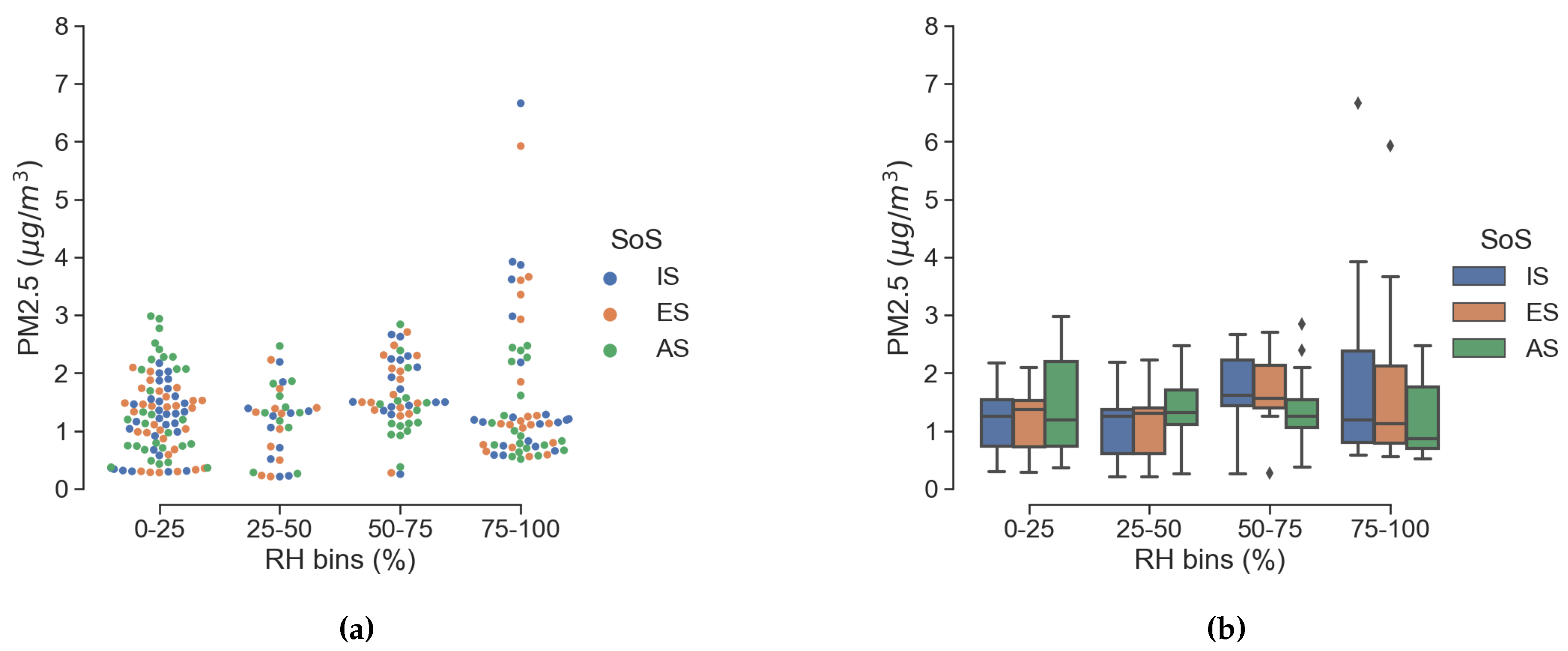

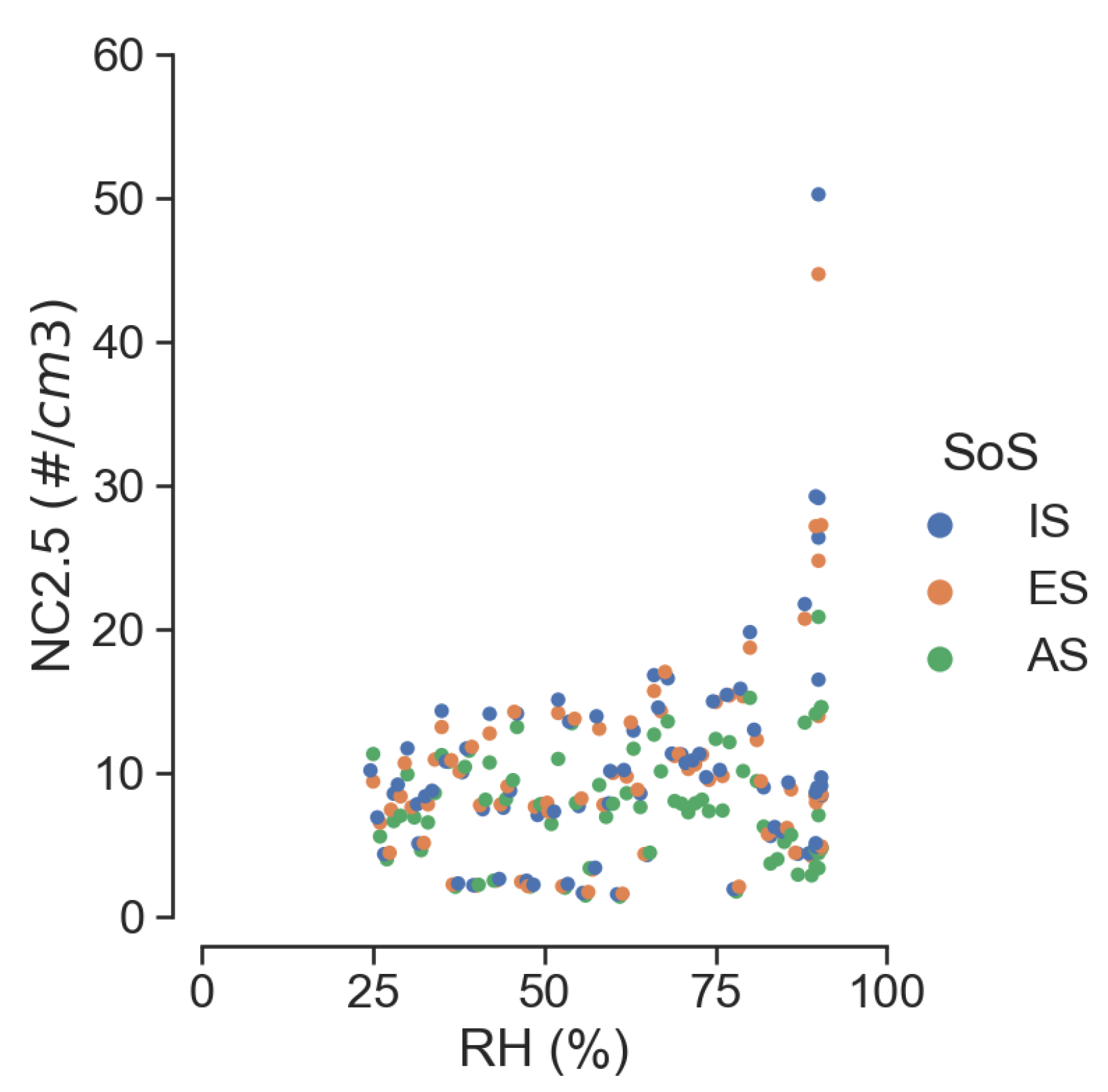

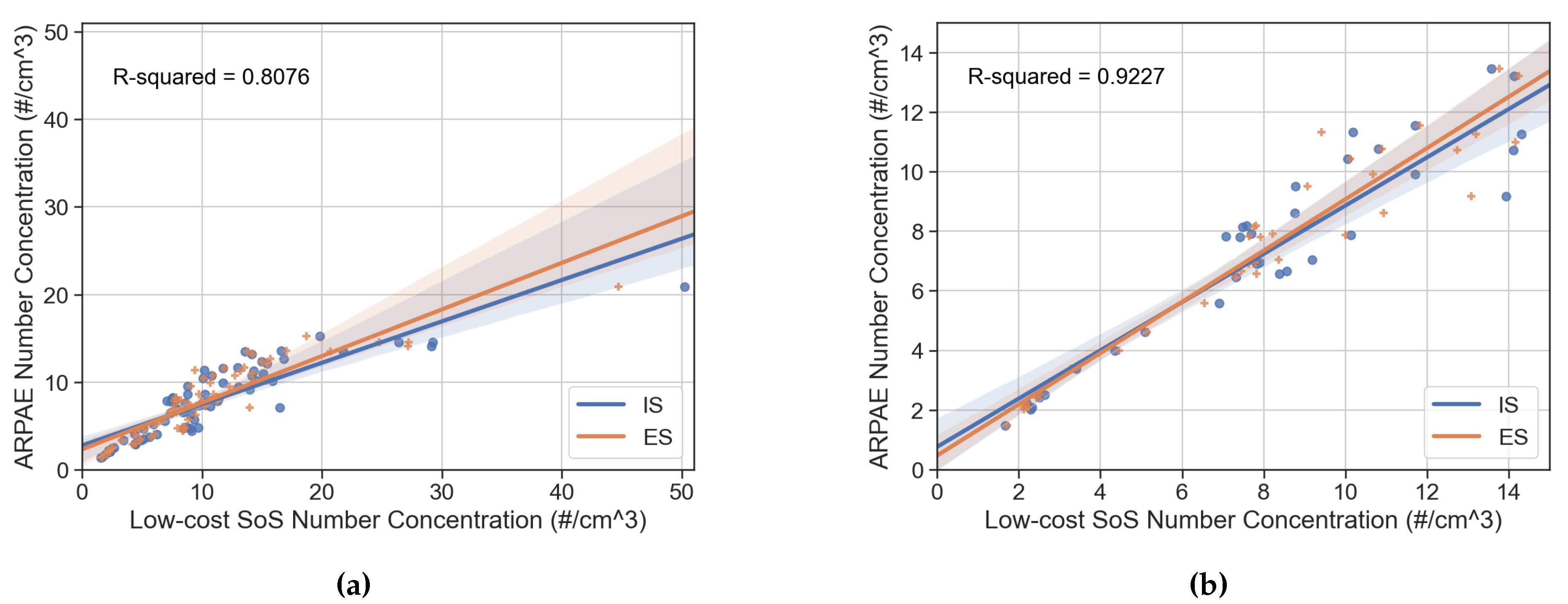

3.2. RH Sensitivity Analysis

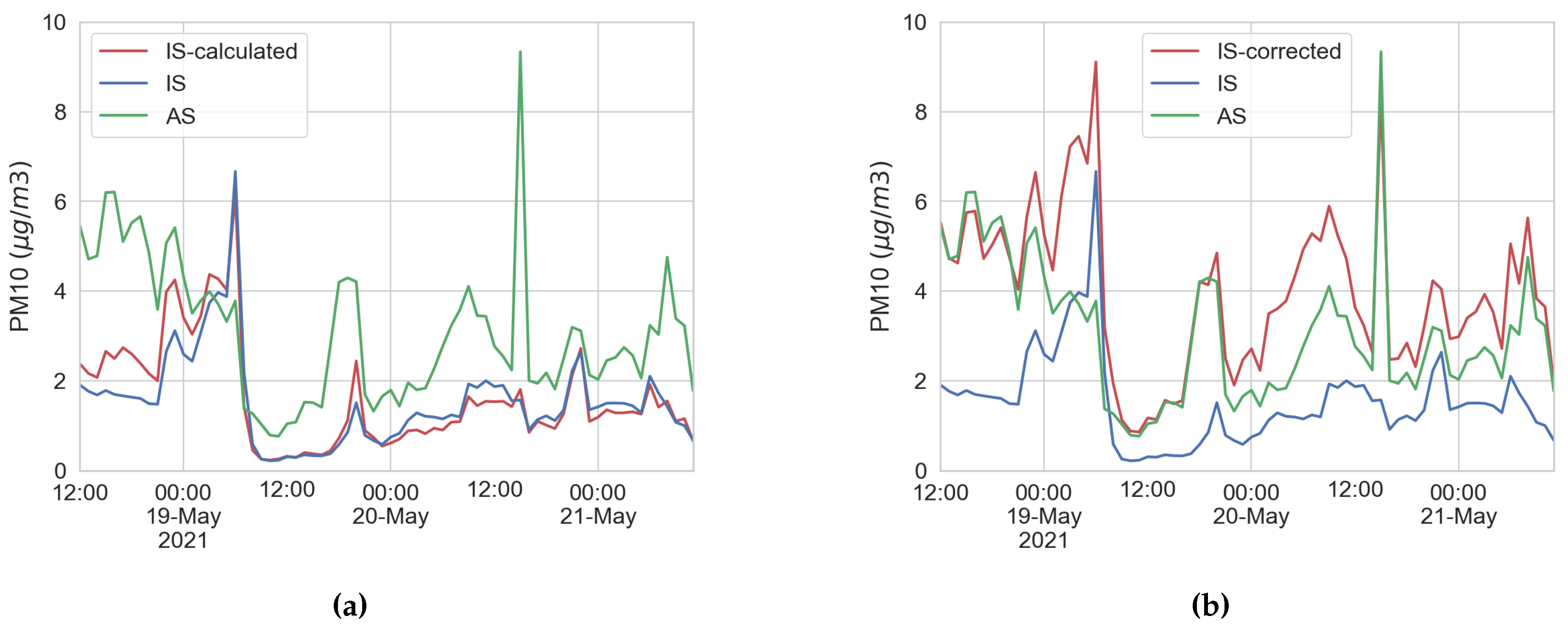

3.3. Mass Conversion Correction

4. Discussion

Abbreviations

| ARPAE | Agenzia regionale per la prevenzione, l’ambiente e l’energia |

| dell´Emilia-Romagna | |

| AS | ARPAE System of Sensors |

| BEV | Battery Electric Vehicle |

| EDA | Exploratory Data Analysis |

| ES | Low cost measurement system 1 |

| IAQ | Internal Air Quality |

| IS | Low cost measurement system 2 |

| LCS | Low Cost Sensor |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NC | Number Concentration |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| OPC | Optical Particle Counter |

| PM | Particulate Matter |

| RH | Relative Humidity |

| SoS | System of Sensors |

References

- Commission), J.R.C.E.; Borowiak, A.; Barbiere, M.; Kotsev, A.; Karagulian, F.; Lagler, F.; Gerboles, M. Review of sensors for air quality monitoring; Publications Office of the European Union: LU, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Settimo, G.; Manigrasso, M.; Avino, P. Indoor Air Quality: A Focus on the European Legislation and State-of-the-Art Research in Italy. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tittarelli, A.; Borgini, A.; Bertoldi, M.; De Saeger, E.; Ruprecht, A.; Stefanoni, R.; Tagliabue, G.; Contiero, P.; Crosignani, P. Estimation of particle mass concentration in ambient air using a particle counter. Atmospheric Environment 2008, 42, 8543–8548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Gerboles.; L. Spinelle.; A. Borowiak. Measuring air pollution with low-cost sensors, 2017.

- Alfano, B.; Barretta, L.; Del Giudice, A.; De Vito, S.; Di Francia, G.; Esposito, E.; Formisano, F.; Massera, E.; Miglietta, M.L.; Polichetti, T. A Review of Low-Cost Particulate Matter Sensors from the Developers’ Perspectives. Sensors 2020, 20, 6819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zauli-Sajani, S.; Marchesi, S.; Pironi, C.; Barbieri, C.; Poluzzi, V.; Colacci, A. Assessment of air quality sensor system performance after relocation. Atmospheric Pollution Research 2021, 12, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belosi, F.; Santachiara, G.; Prodi, F. Performance Evaluation of Four Commercial Optical Particle Counters. Atmospheric and Climate Sciences 2013, 3, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franken, R.; Maggos, T.; Stamatelopoulou, A.; Loh, M.; Kuijpers, E.; Bartzis, J.; Steinle, S.; Cherrie, J.W.; Pronk, A. Comparison of methods for converting Dylos particle number concentrations to PM2.5 mass concentrations. Indoor Air 2019, 29, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, L. Calibrating low-cost sensors for ambient air monitoring: Techniques, trends, and challenges. Environmental Research 2021, 197, 111163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinoi, A.; Donateo, A.; Belosi, F.; Conte, M.; Contini, D. Comparison of atmospheric particle concentration measurements using different optical detectors: Potentiality and limits for air quality applications. Measurement 2017, 106, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Clark, J.D.; May, A.A. A systematic investigation on the effects of temperature and relative humidity on the performance of eight low-cost particle sensors and devices. Journal of Aerosol Science 2021, 152, 105715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vito, S.; Esposito, E.; Castell, N.; Schneider, P.; Bartonova, A. On the Robustness of Field Calibration for Smart Air Quality Monitors. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2020, 310, 127869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russi, L.; Guidorzi, P.; Pulvirenti, B.; Semprini, G.; Aguiari, D.; Pau, G. Air quality and comfort characterisation within an electric vehicle cabin. 2021 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Automotive (MetroAutomotive), 2021, pp. 169–174. [CrossRef]

- Kondaveeti, H.K.; Kumaravelu, N.K.; Vanambathina, S.D.; Mathe, S.E.; Vappangi, S. A systematic literature review on prototyping with Arduino: Applications, challenges, advantages, and limitations. Computer Science Review 2021, 40, 100364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Sai, K.B.; Mukherjee, S.; Parveen Sultana, H. Low Cost IoT Based Air Quality Monitoring Setup Using Arduino and MQ Series Sensors With Dataset Analysis. Procedia Computer Science 2019, 165, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sensortec, B. BME280 Combined humidity and pressure sensor. Bosch Sensortec 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Li, H.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Y.; Abokifa, A.A.; Lu, C.; Biswas, P. Spatiotemporal distribution of indoor particulate matter concentration with a low-cost sensor network. Building and Environment 2018, 127, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryner, J.; Mehaffy, J.; Miller-Lionberg, D.; Volckens, J. Effects of aerosol type and simulated aging on performance of low-cost PM sensors. Journal of Aerosol Science 2020, 150, 105654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuula, J.; Mäkelä, T.; Aurela, M.; Teinilä, K.; Varjonen, S.; González, Ó.; Timonen, H. Laboratory Evaluation of Particle-Size Selectivity of Optical Low-Cost Particulate Matter Sensors. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques 2020, 13, 2413–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO. BS ISO 16000-37:2019. Indoor Air - Part 37: Measurement of PM_{2,5} mass concentration; BSI Standards Publication, 2019.

- Guthrie, W.F. NIST/SEMATECH e-Handbook of Statistical Methods (NIST Handbook 151), 2020. type: dataset. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, K.E.; Whitaker, J.; Petty, A.; Widmer, C.; Dybwad, A.; Sleeth, D.; Martin, R.; Butterfield, A. Ambient and Laboratory Evaluation of a Low-Cost Particulate Matter Sensor. Environmental Pollution 2017, 221, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakim, N.I.; Braun, T.M.; Kaye, J.A.; Dodge, H.H.; Orcatech, F. Choosing the Right Time Granularity for Analysis of Digital Biomarker Trajectories. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions 2020, 6, e12094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhu, W.; Yao, J.; Gu, C.; Bai, D.; Wang, K. Time Granularity Transformation of Time Series Data for Failure Prediction of Overhead Line. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2017, 787, 012031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weijers, E.P.; Khlystov, A.Y.; Kos, G.P.A.; Erisman, J.W. Variability of Particulate Matter Concentrations along Roads and Motorways Determined by a Moving Measurement Unit. Atmospheric Environment 2004, 38, 2993–3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zikova, N.; Hopke, P.K.; Ferro, A.R. Evaluation of New Low-Cost Particle Monitors for PM2.5 Concentrations Measurements. Journal of Aerosol Science 2017, 105, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Specifications | Summary (Day2,Day3) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Unit) | Description | Sensor | IS | ES | AS | MSR |

| Air temp. | BME280 | (21.0,20.8) | (19.5,19.6) | (19.1,18.9) | (18.7,15.8) | |

| Air rel. hum. | BME280 | (51,43) | (55,46) | (71,62) | (42,57) | |

| PM1 conc. | SPS30 | (1,1) | (1,1) | (0,0) | n.d. | |

| PM2.5 conc. | SPS30 | (1.5,1.4) | (1.4,1.3) | (1.1,1.1) | (5.2,2.4) | |

| PM10 conc. | SPS30 | (2,1) | (1,1) | (2,3) | (15,6) | |

| Number conc. | SPS30 | (11,11) | (10,10) | (6,8) | n.d. | |

| Number conc. | SPS30 | (11,11) | (10,10) | (6,8) | n.d. | |

| Number conc. | SPS30 | (11,11) | (10,10) | (6,8) | n.d. | |

| a mv = measured value. | ||||||

| AS | IS, ES | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Channel | size range ( ) | Channel | size range ( ) |

| 1 | 0.28-0.4 | 1 | 0.3-0.5 |

| 2 | 0.4-0.5 | ||

| 3 | 0.5-0.7 | 2 | 0.5-1.0 |

| 4 | 0.7-1.1 | ||

| 5 | 1.1-2.0 | 3 | 1.0-2.5 |

| 6 | 2.0-3.0 | ||

| 7 | 3.0-5.0 | 4 | 2.5-4 |

| 8 | 5.0-10 | 5 | 4.0-10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).