Submitted:

11 July 2024

Posted:

12 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chevalier, J.; Gremillard, L.; Virkar, A.V.; Clarke, D.R. The tetragonal-monoclinic transformation in zirconia: Lessons learned and future trends. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2009, 92, 1901–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannink, R.H. J; Kelly PM; Muddle, B.C. Transformation toughening in zirconia-containing ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2000, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogstad, J.A.; Krämer, S.; Lipkin, D.M.; Johnson, C.A.; Mitchell, D.R.G.; Cairney, J.M.; Levi, C.G. Phase stability of t′-zirconia-based thermal barrier coatings: Mechanistic insights. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2011, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisbergues, M; Vendeville, S; Vendeville, P. Review zirconia: J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2009, 88. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Wang, C.; Xu, X.; Li, H. Machine learning potential for Ab Initio phase transitions of zirconia. Theoretical and Applied Mechanics Letters. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuer, A.H. Transformation Toughening in ZrO2-Containing Ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1987, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Martin, C; Ajay, O.O; Singh, D; Routbort, J.L. Evaluation of scuffing behavior of single-crystal zirconia ceramic materials. Wear 2007, 263. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J; Tian, C; Yang, J; He, J. Electrical and mechanical properties of Sm2O3 doped Y-TZP electrolyte ceramics. Ceram Int. 2018, 44. [CrossRef]

- Bejugama, S; Chameettachal, S; Pati, F;. Pandey, A.K. Tribology and in-vitro biological characterization of samaria doped ceria stabilized zirconia ceramics. Ceram Int, 2021; 47. [CrossRef]

- Grathwohl, G; Liu, T. Crack Resistance and Fatigue of Transforming Ceramics: II, CeO2-Stabilized Tetragonal ZrO2. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1991, 74. [CrossRef]

- Rauchs, G; Fett, T; Munz, D; Oberacker R. Tetragonal-to-monoclinic phase transformation in CeO2-stabilised zirconia under uniaxial loading. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2001, 21. [CrossRef]

- Palmero, P; Fornabaio, M; Montanaro, L; Reveron, H.; Esnouf, C.; Chevalier, J. Towards long lasting zirconia-based composites for dental implants: Part I: Innovative synthesis, microstructural characterization and invitro stability. Biomaterials. 2015, 50. [CrossRef]

- Savin, A; Craus, M.L; Turchenko, V; Bruma, A.; Dubos, P.A.; Malo, S; Konstantinova, T.E.; Burkhovetsky, V.V. Monitoring techniques of cerium stabilized zirconia for medical prosthesis. Applied Sciences. 2015, 5. [CrossRef]

- Reveron, H; Fornabaio, M; Palmero, P; Fürderer, T.; Adolfsson, E.; Lughi, V.; Bonifacio, A.; Sergo, V.; Montanaro, L.; Chevalier, J. Towards long lasting zirconia-based composites for dental implants: Transformation induced plasticity and its consequence on ceramic reliability. Acta Biomater. 2017, 48. [CrossRef]

- Borik, M.A; Kulebyakin, A.V.; Lomonova, E.E; Milovich, F.O.; Myzina, V.A.; Ryabochkina, P.A.; Sidorova, N.V.; Tabachkova, N.Yu.; Chislov, A.S. Effect of heat treatment on the structure and mechanical properties of zirconia crystals partially stabilized with samarium oxide. Modern Electronic Materials. 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisi, E.H; Howard, C.J. Crystal structures of zirconia phases and their inter-relation. Key. Eng. Mater 1998, 153–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Li, M.; Zhang, C.; Huang, X.; Ye, F. Dy2O3 stabilized ZrO2 as a toughening agent for Gd2Zr2O7 ceramic. Mater. Lett. 2017, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W; Nakashima, S; Marin, E; Gu H.; Pezzotti, G. Annealing-induced off-stoichiometric and structural alterations in ca2+ - and y3+ - stabilized zirconia ceramics. Materials. 2021, 14. [CrossRef]

- Schulz, U. Phase transformation in EB-PVD yttria partially stabilized zirconia thermal barrier coatings during annealing. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2000, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Fujiwara, A.; Nishiike, N.; Nakashima, S.; Gu, H.; Marin, E.; Sugano, N.; Pezzotti, G. Mechanisms induced by transition metal contaminants and their effect on the hydrothermal stability of zirconia-containing bioceramics: An XPS study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W; Nakashima, S; Marin, E; Gu, H.; Pezzotti, G. Microscopic mapping of dopant content and its link to the structural and thermal stability of yttria-stabilized zirconia polycrystals. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 55. [CrossRef]

- Turon-Vinas, M; Roa, J.J; Marro, F.G; Anglada, M. Mechanical properties of 12Ce-ZrO2/3Y-ZrO2 composites. Ceram. Int. 2015;41. [CrossRef]

- Borik, M; Kulebyakin V; Myzina V; Lomonova, Е.Е.; Milovich, F.О.; Ryabochkina P.A.; Sidorova, N.V.; Shulga, N.Y.; Tabachkova, N.Y. Mechanical characteristics, structure, and phase stability of tetragonal crystals of ZrO2–Y2O3 solid solutions doped with cerium and neodymium oxides. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 2021;150. [CrossRef]

- Borik, M; Chislov, A; Kulebyakin, A; Lomonova, Е.Е.; Milovich, F.О.; Myzina V; Ryabochkina P.A.; Sidorova, N.V.; Tabachkova, N.Y. Phase Composition and Mechanical Properties of Sm2O3 Partially Stabilized Zirconia Crystals. Crystals. 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Niihara, K. A fracture mechanics analysis of indentation-induced Palmqvist crack in ceramics. J. Mater. Sci. Lett. 1983, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niihara, K; Morena R; Hasselman D.P.H. Evaluation of KIc of brittle solids by the indentation method with low crack-to-indent ratios. J. Mater. Sci. Lett. 1982, 1. [CrossRef]

- Moradkhani, A; Baharvandi, H. Effects of additive amount, testing method, fabrication process and sintering temperature on the mechanical properties of Al2O3/3Y-TZP composites. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2018, 191. [CrossRef]

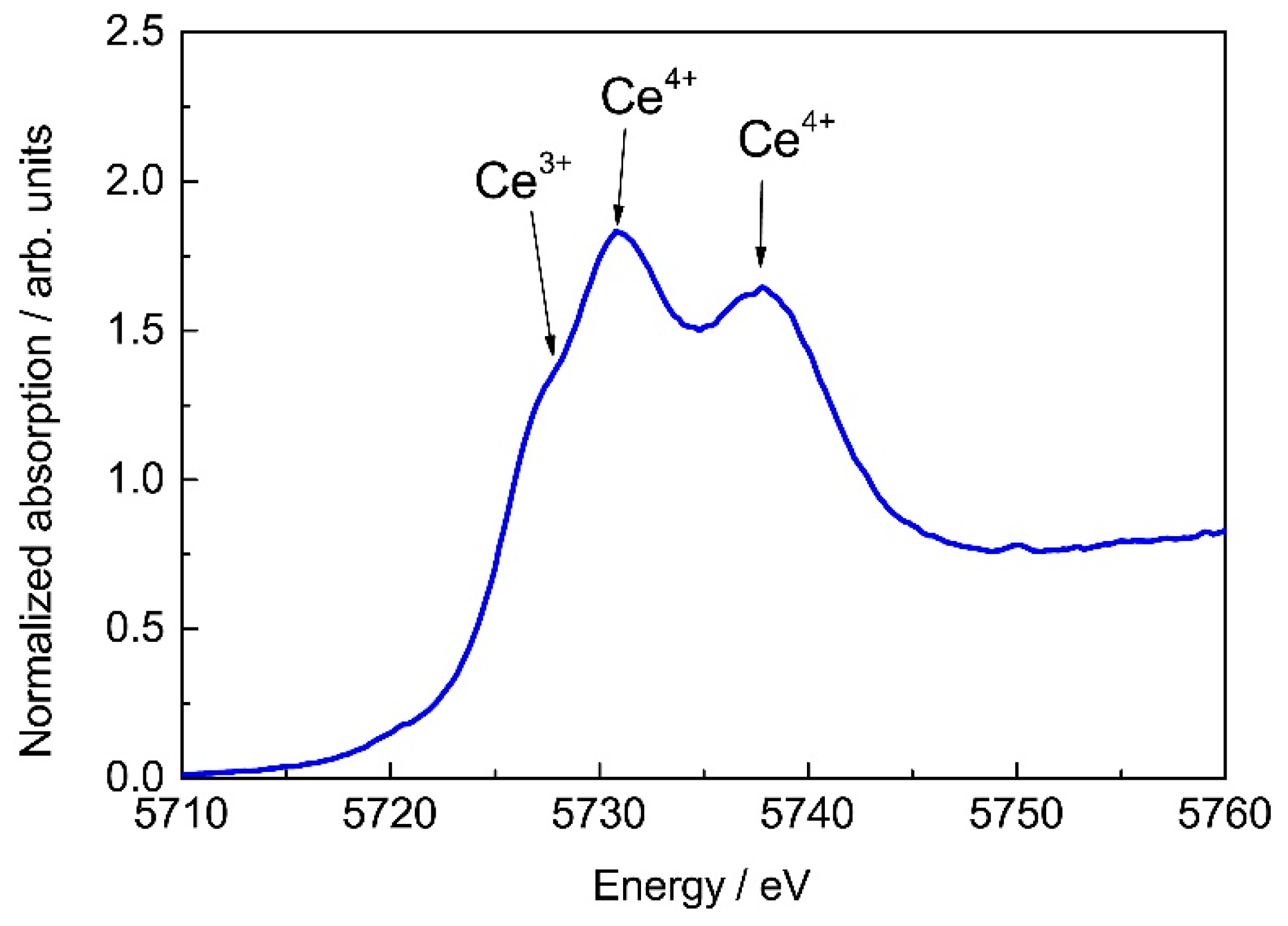

- Orera, V.M; Merino, R.I; Peña, F. Ce3+↔Ce4+ conversion in ceria-doped zirconia single crystals induced by oxido-reduction treatments. Solid State Ion. 1994, 72(PART 2). [CrossRef]

- Kozlova, A.P; Kasimova, V.M; Buzanov, O.A; Chernenko, K.; Klementiev, K.; Pankratov, V. Luminescence and vacuum ultraviolet excitation spectroscopy of cerium doped Gd3Ga3Al2O12 single crystalline scintillators under synchrotron radiation excitations. Results Phys. 2020, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, M; Yashima, M; Noma, T; Sōmiya, S. Formation of diffusionlessly transformed tetragonal phases by rapid quenching of melts in ZrO 2 -RO 1.5 systems (R = rare earths). J. Mater. Sci. 1990, 25. [CrossRef]

- Kern, F. Ytterbia-neodymia-costabilized TZP-Breaking the limits of strength-toughness correlations for zirconia? J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2013, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borik, M.A.; Chislov, A.S.; Kulebyakin, A.V.; Lomonova, Е.Е.; Milovich, F.О.; Myzina, V.A.; Ryabochkina, P.A.; Sidorova, N.V.; Tabachkova, N.Y. Effect of heat treatment on the structure and mechanical properties of partially gadolinia-stabilized zirconia crystals. J. Asian Ceram. Soc. 2021, 9, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, A.G; Cannon, R.M. Overview no. 48. Toughening of brittle solids by martensitic transformations. Acta Metallurgica. 1986, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, F.R; Ubic, F. J; Prakash; V, Heuer, A.H. Stress-induced martensitic transformation and ferroelastic deformation adjacent microhardness indents in tetragonal zirconia single crystals. Acta Mater 1998, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

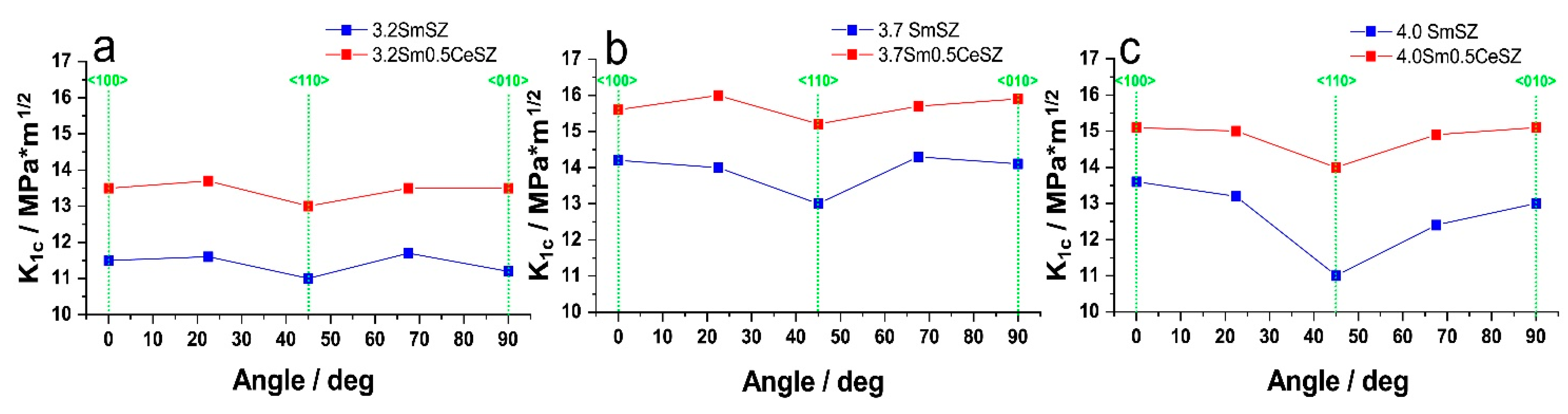

| Specimen | Phase | Content, wt.% | Lattice Parameters, Å | c/√2a |

| 3.7SmSZ [24] | t t’ |

85 ± 5 15 ± 5 |

a = 3.6062(2) c = 5.1866(2) a = 3.6426(5) c = 5.1695(2) |

1.0170 1.0035 |

| 3.7Sm0.5CeSZ | t t´ |

90 ± 5 10 ± 5 |

a = 3.6062(2) c = 5.1886(2) a = 3.6426(5) c = 5.1682(2) |

1.0174 1.0032 |

| 4.0SmSZ[24] | t t´ |

75 ± 5 25 ± 5 |

a = 3.6063(2); c = 5.1854(2) a = 3.6429(5); c = 5.1692(2) |

1.0167 1.0034 |

| 4.0Sm0.5CeSZ | t t´ |

85 ± 5 15 ± 5 |

a = 3.6063(1) c = 5.1877(2) a = 3.6427(5) c = 5.1685(2) |

1.0172 1.0033 |

| Composition | Microhardness, GPa | Composition | Microhardness, GPa |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.2SmSZ | 10.75 ± 0.30 | 3.2Sm0.5CeSZ | 10.54 ± 0.25 |

| 3.7SmSZ | 11.30 ± 0.30 | 3.7Sm0.5CeSZ | 11.15 ± 0.25 |

| 4.0SmSZ | 12.15 ± 0.30 | 4.0Sm0.5CeSZ | 11.70 ± 0.25 |

| Specimen | HV, GPa | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| As-Grown | Vacuum Annealed | Air Annealed | |

| 3.2Sm0.5CeSZ | 10.54 ± 0.25 | 8.55 ± 0.30 | 8.50 ± 0.30 |

| 3.7Sm0.5CeSZ | 11.15 ± 0.25 | 8.65 ± 0.30 | 8.60 ± 0.30 |

| 4.0Sm0.5CeSZ | 11.70 ± 0.25 | 9.25 ± 0.30 | 8.70 ± 0.30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).