1. Introduction

Due to their unique characteristics and excellent thermomechanical properties, polyimides (PI) are highly desired by scientists and engineers. Polyimides have excellent thermal and mechanical properties, are easy to produce as thin films and coatings from soluble precursors. They have excellent dielectric properties, high optical transparency, low refractive index, and high glass transition temperature [

1,

2,

3]. Due to their usefulness as membranes, composite matrix material, films, fibers, foams, coatings, and adhesives in the microelectronics and photoelectric industries, they are among the most desirable high-performance and high-temperature polymers [

4,

5,

6,

7]. It is important to highlight that the right combination of the polymer matrix and the nanofiller reinforcement can produce polymer nanocomposites with novel structures and improved mechanical, electrical, and thermal properties [

8,

9,

10]. Polyimides have less chain flexibility than aliphatic polymers, which results in higher glass transition temperature, T

g, greater heat resistance, and good mechanical properties. Plyimides are made up of planar rigid monomers joined end-to-end to each other at set bond angles [

11,

12]. As a result, polyimides, which are used as high temperature insulators and dielectrics, are one of the most widely used polymers in microelectronics [

7,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. A common polymer precursor utilized in the production of high performance polyimides is poly(amic acid) (PAA).

The PAA is made up of aromatic rings joined together by amide (-CONH-) functional group [

18]. Outstanding thermal resistance, superior chemical resistance, low creep, and outstanding mechanical strength are the characteristics of polyimides produced from poly(amic acid). These characteristics make them useful for a variety of applications, including high temperature coatings, electronics packaging, aerospace fuselage, and automotive chasis [

7,

19]. Hybrids materials constituted of polyimide matrix and nanoclay reinforcement have recently been investigateed [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. The study of polyimide-clay nanocomposites were primarily focused on determining the impact of nanoclay filler on the barrier properties and coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) of the polyimide films. In comparison to neat polyimide, the gas permeability of the polyimide-clay nanocomposites is lower [

25,

26,

27], and the CTE of the nanocomposite is significantly reduced [

28,

29,

30]. The addition of nanoclay fillers to poly(amic acid) can influence the rheological properties of poly(amic acid) suspension. The presence of clay can increase the viscosity of the polymer suspension, and lead to increased densification and enhanced thermomechanical properties of the polyimide matrix. The nanofillers can also affect the flow behavior of the poly(amic acid) suspension, there-by altering its rheological characteristics [

31,

32,

33]. It is a usual practice to use rheological tools such as the oscillatory rheometer and concentric cylinder couette to inveestigate the rheological behavior of poly(amic acid) nanocomposites. The data obtained from such tests offer useful insights into the response of the material to shear deformation, temperature and frequency [

34,

35]. The rheological behavior of poly(amic acid) nanocomposites can be influenced by various factors, including the nanofiller concentration, dispersion, polymer matrix properties, and processing conditions. Therefore, understanding and controlling these factors can help tailor the processability and mechanical properties of the nanocomposite for desired applications [

36,

37,

38,

39]. The nature of the solvent, processing temperature, and filler concentration affect the solution properties of a polymer suspension. At low concentrations, the polymer chains are isolated from one another, with each chain occupying a sphere with a radius R

g. The volume of the polymer coil is dictated by the thermodynamic interactions between the polymer and the solvent in the solution. The intrinsic viscosity, [η], a parameter that can be determined by measuring the viscosity of dilute polymer solutions, is the hydrodynamic volume occupied by a given polymer mass, which best represents the interaction of the polymer with the solvent. [

40,

41]. The intrinsic viscosity is typically determined by measuring the viscosity of a polymer solution at different concentrations and extrapolating the data to zero concentration. A higher intrinsic viscosity indicates a larger polymer size and higher molecular weight [

42].

Graphene, an atomic-scale carbon atom lattice has attracted a great deal of interest due to its remarkable mechanical strength, electrical conductivity, and surface area [

43,

44]. Graphene reinforced polyimide should have improved electrical and electrochemical properties. Polyimide-graphene nanocomposites, therefore, provide a special combination of properties appropriate for advanced electrode materials. The same is true for polyimide/ carbon nanotubes (CNTs) composites [

45,

46,

47]. The electrical properties of polyimide can be greatly improved by addition of CNTs because of the later’s high electrical conductivity [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50]. Polypyrrole (PPy) is a conductive polymer with the inherent ability to store energy through the formation of an electric double layer [

51]. Polypyrrole (PPy) displays a pseudocapacitive behavior in addition to its electric double-layer storage mechanism. Its structure, characterized by conjugated double bonds, enables electroactivity in both aqueous and organic media, with an electrical conductivity range of 10

−4 to 10

−2 S/cm [

52,

53]. Doping, PPy with inorganic and organic acids, as well as polymeric stabilizers, has been shown to enhance PPy's electrical and electrochemical properties by influencing its morphology [

52,

53].

The purpose of this study is to comprehensively investigate the rheological, thermal, and electrochemical properties of polyimide obtained poly(amic acid) (PAA) solution and its suspension containing 5wt% polyaniline-modified montmorillonite clay and nanographene sheets, respectively. Specifically, this study aims to elucidate how various additives and processing conditions influence the flow behavior, thermal stability, fire retardancy, and electrochemical properties of the nanocomposites. This study seeks to optimize the processability, and energy storage ability of PI and its nanocomposite electrodes for application in high-temperature and safety-critical applications in a sustainable energy storage system.

2. Experimental Method

2.1. Material

4,4-oxydianiline, ODA (97% purity), pyromellitic dianhydride, PMDA (99% purity), and N-methylpyrrolidone, NMP (99% purity) were the reagents used in this investigation. They were bought from the Sigma-Aldrich Company. Cloisite 30B clay used in this study is natural montmorrilonite clay, MMT modified with polyaniline copolymer. Nanographene sheets, NGS (98.48% purity) was purchased from Angstron Materials, Inc, Dayton, OH, USA. All the materials were used as received.

2.2. Synthesis and Fabrication of the Nanocomposites

2.2.1. Poly(Amic Acid)/Clay Nanocomposites

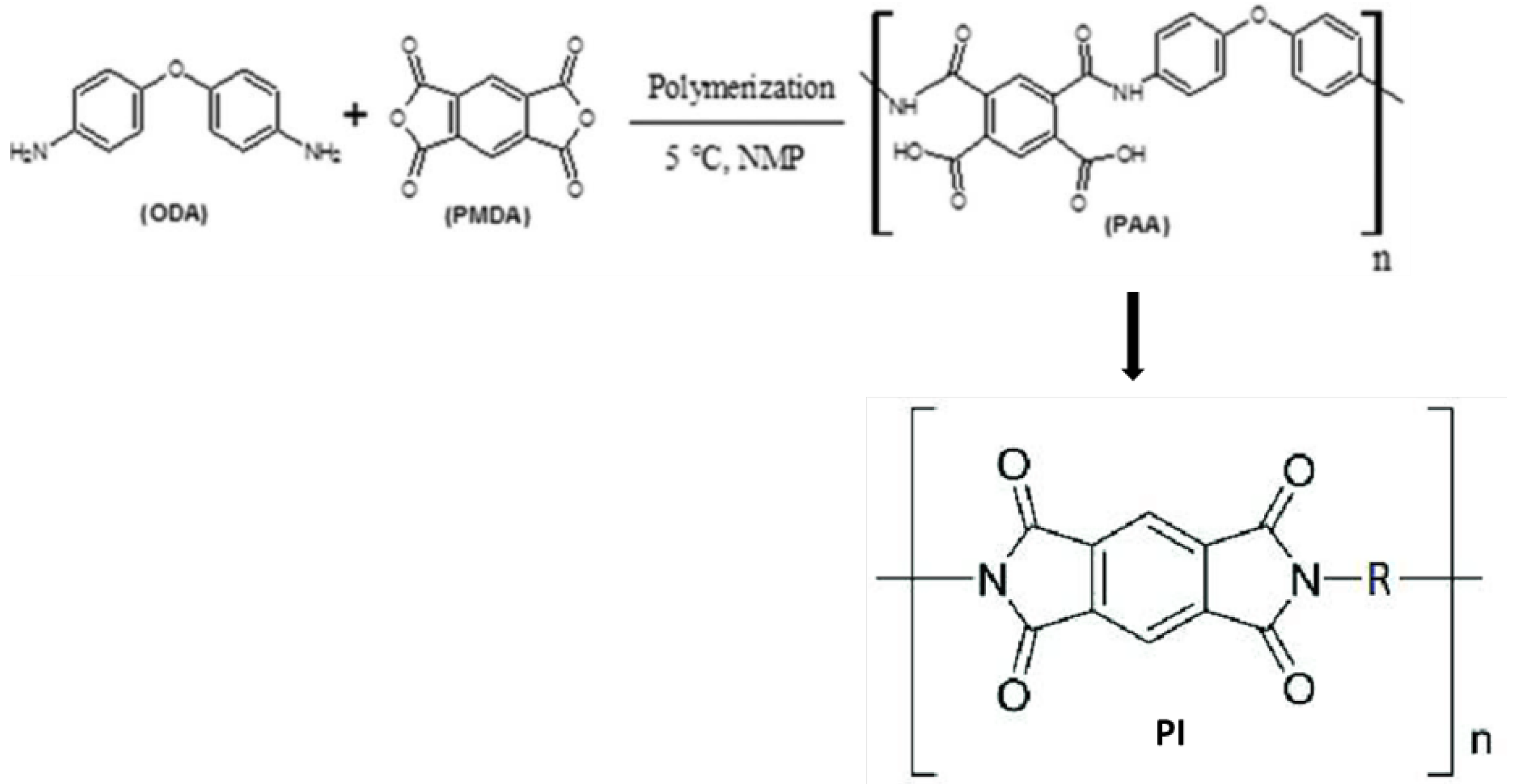

Poly(amic acid) was synthesized by the reaction of pyromellitic dianhydride, PMDA with 4,4'-diaminodiphenyl ether, ODA. The resulting poly(amic acid) was dissolved in N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP), to form a viscous solution. To prepare the neat PAA solutions, 0.025 mol of ODA was dissolved in 100 mL of NMP in a three-necked flask and the solution was maintained at 5˚C with stirring for 30 minutes. Then, an equimolar amount of PMDA was added to the solution. Polymerization was carried out for 15 hours with continuous stirring. To prepare the polyimide clay nanocomposite, clay was dispersed in the ODA solution and stirred for 6 hours after which equimolar amount of PMDA was added, and stirring continued for another 15 hours. The reaction mixture contained 5wt% clay. Both the neat poly(amic acid) and the poly(amic acid)-clay suspension were ultrasonnicated for 5-minute before they were cast onto a glass substrate and rectangular steel (Fe3C) coupons, respectively, and thermally treated to form thin film (Scheme I). Dilute solution viscometry of poly(amic acid) and PAA solution containing polyaniline copolymer modified clay was performed by using the Ubbelohde viscometer. The solvent used to carry out dilute solution viscometry is N-Methyl-Pyrrolidone, NMP, and the solution concentrations ranged from 1 to 0.4 g/dL. The time taken by the solvent and the respective solutions to pass through the marked section of the viscometer was measured and each run was repeated until a deviation of less than 2 seconds was obtained.

2.2.2. Preparation of Polyimide-Carbonnanotube/Polyvinylidene Fluoride Nanocomposites (PI-CNT/PVDF)

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) sheets containing upto 90 wt% of CNT dispersed onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) matrix was used to prepare polyimide-CNT-PVDF composite. PAA solution synthesized by reacting equimolar amounts of PMDA and ODA in an N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) was used. The PAA solution was uniformly applied onto the nanotube sheet by solution casting method. The coated CNT sheet was initially cured in a vacuum oven at 90 °C for several hours to remove the solvent. This was followed by a stepwise thermal treeatment process, raising the temperature to 250 °C for an additional six hours under a vacuum of 28 in.Hg. The thermal treatment converts the PAA into polyimide, resulting in a stable and robust composite material. After cooling, the composite sheet was carefully peeled off the substrate. The final product is a CNT/PVDF sheet uniformly covered with polyimide. The composite sheet was subsequently used as the working electrode in electrochemical deposition of polypyrrole, PPy. This meticulous process ensures the film's stability and integrity, preventing shrinkage and defects.

2.2.3. Polyimide-Nanographene Composites (PI-NGC)

About 10 mL of the PAA-NGC mixture was evenly cast onto a glass substrate and thermally treated in a vacuum oven. The thermal treatment process involved heating at 120 °C for 2 hours, followed by increasing the temperature to 200 °C for 1 hour, to form polyimide-nanographene sheet composite. This stepwise approach ensured that the films remained stable without shrinkage. Subsequent mixtures containing 10, 20, 40 and 60 wt.% NGS were prepared, and the samples were designated based on the graphene sheet content in the composites as PI-NGC-10, PI-NGC-20, PI-NGC-40, and PI-NGC-60. The fully cured films had a thickness ranging from 100 to 200 µm.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of polyimide (PI).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of polyimide (PI).

2.2.4. Polypyrrole Electrodeposition and Doping

Pyrrole (Py) was dissolved in 100 mL of water to make a 0.5 M solution, to which 0.0225 M p-Toluene sulfonic acid was added. The mixture was stirred until it completely dissolved, resulting in a clear solution. CNT/PVDF/PI film was used as the working electrode. Each electrode was immersed in 0.5 M pyrrole solution in a three-electrode cell configuration connected to a Gamry 3000 potentiostat. A glassy carbon counter electrode and Ag/AgCl reference electrode were used to perform potentiostatic electrochemical polymerization by applying 2 V for 60s. After the deposition of polypyrrole was completed, each electrode was rinsed with ethanol, dried in a vacuum oven at 100 °C to remove moisture, and weighed.

2.3. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) was used to investigate the thermal behavior of the samples. DSC was conducted at a heating rate of 5°C/min in two temperature ranges of 25 to 350˚C and 25 to 725˚C, respectively, for the samples designated based on the nanographene sheet composition as PI-NGC-10, PI-NGC-10(100RPM), and PI-NGC-40(100RPM).

2.4. Cyclic Voltammetry, CV

Electrochemical characterization was carried out using the Gamry 3000 potentiostat in a 3-electrode cell configuration with an Ag/AgCl reference electrode. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) was carried out at a voltage range between 0 to 1 V using two different scan rates of 5, and 25 mV/s for 1 to 10 cycles to determine the peak current, total charge storage stored and specific capacitance of the nanocomposite electrode.

3.0. Result and Discussion

3.1. Rheology

The concentric cylinder rotary viscometer (Brookfield Viscometer) was used to measure the viscosity of poly(amic acid) (PAA) solution and PAA suspension containing 5wt% polyaniline copolymer, PNEA modified Cloisite 30B clay. The spindle speed was varied from 0.5 to 100 rpm. The viscometer measured the viscosity in centipoise (cP) and torque % as a function of temperatures and spindle speed. The simplified version of the constitutive equation (equation 1) for the concentric cylinder viscometer, was used to calculate the shear stress at the bob surface. Calderbank and Moo-Young equation (equation 2) was used to calculate the shear rate at the bob surface.

The rheological behavior of poly(amic acid) (PAA) solution and its suspension containing 5wt% polyaniline copolymer modified (PNEA) clay was fitted by using the power law model (equations 3 & 4). The power law model, also known as the Ostwald-de Waele model, is used to describe the flow behavior of fluids that exhibit non-Newtonian behavior:

where η is the viscosity, K is the consistency index,

is the shear rate, n is the flow behavior index,

is the shear stress at the bob, N spindle speed,

is the bob radius,

is the cup radius, and T is the torque.

Viscosity measurement was made at temperatures between 25 and 95°C and at a spindle speeds between 0.5 and 100 rpm.

Effect of Modified Nanoclay on the Viscosity of PAA Solution

Equation 4 was used to fit the data obtained and calculate the Power law parameters, K and n.

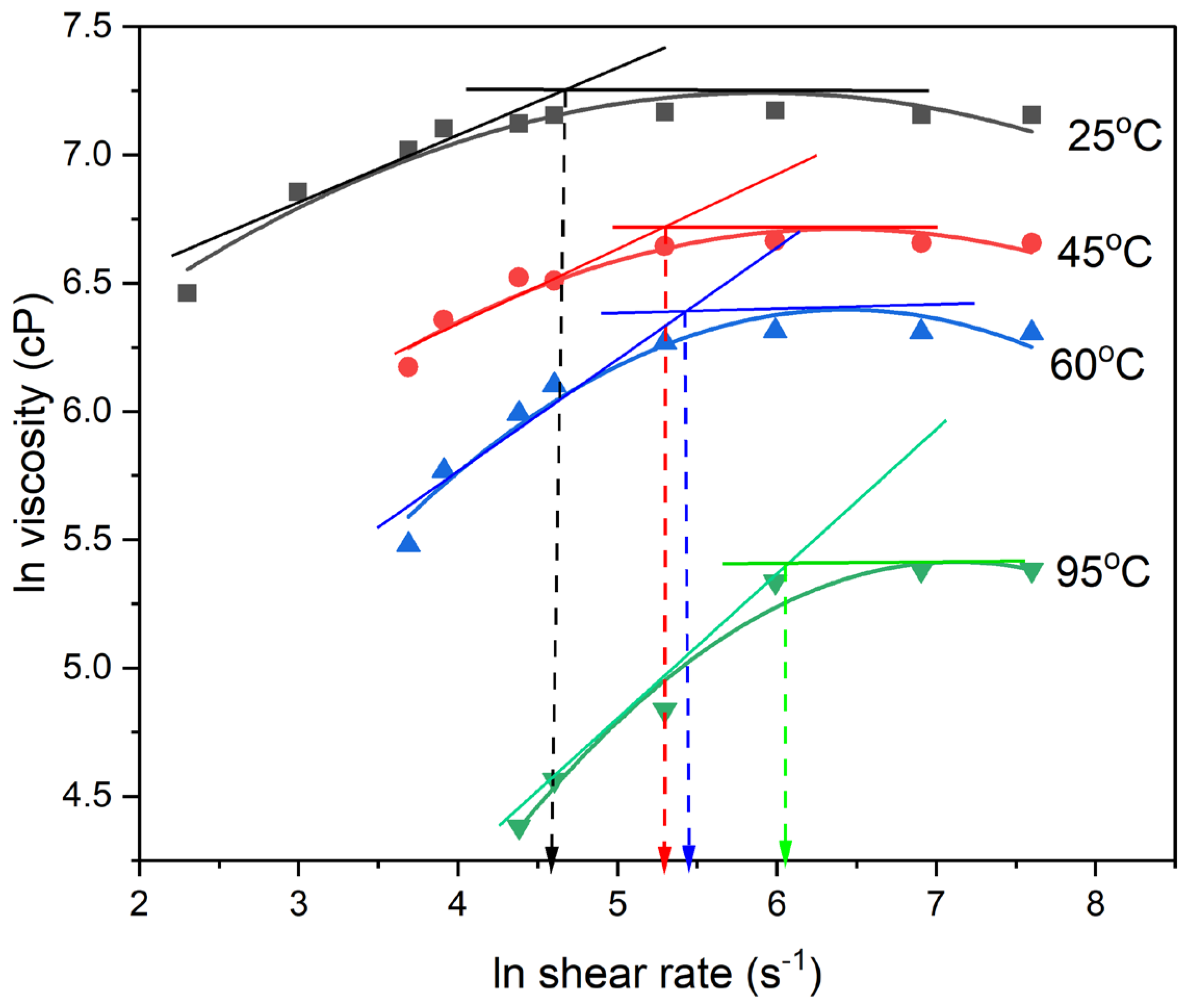

From

Figure 1, it is shown that at 25°C, the viscosity of the neat PAA shows two important thrends of initially increasing viscosity up to a shear rate of about 100 s

-1 followed by a levelling-off region with a constant viscosity of about 1500 cP.

Figure 1 shows that PAA solution behaves as a dilatant fluid at low temperature and low shear rate, and transitioned into a Newtonian behavior at moderate shear rates ≥ 100 s

-1 (

Figure 1). By fitting the first region of rheological behavior with the Power Law model, the exponent n value of about 2 was obtained which is indicative of rheological dilatancy behavior. As the testing temperature was increased to 45°C, 60°C, and 95°C, respectively, the shear rate at which the transition from dilatant to Newtonian behavior increased from 100 s

-1 at 25˚C to 400 s

-1 at 95˚C. The transition from Power Law to Newtonian behavior is associated with both the critical shear rate and the levelling-off viscosity (

Figure 1). At 45°C the transition occurs at a critical shear rate of about 200 s

−1, with and a levelling-off viscosity of about 800 cP. At 60°C the transition occurred at critical shear rate and viscosity of about 240 s

−1, and 544 cP, respectively. As shown in

Figure 1, higher testing temperatures increase the critical shear rate for the onset of Newtonian behavior and decreases the steady-state Newtonian viscosity. The increasing steepness of the curves at higher temperatures signifies more pronounced shear-thickening behavior, due to faster evaporation of the solvent.

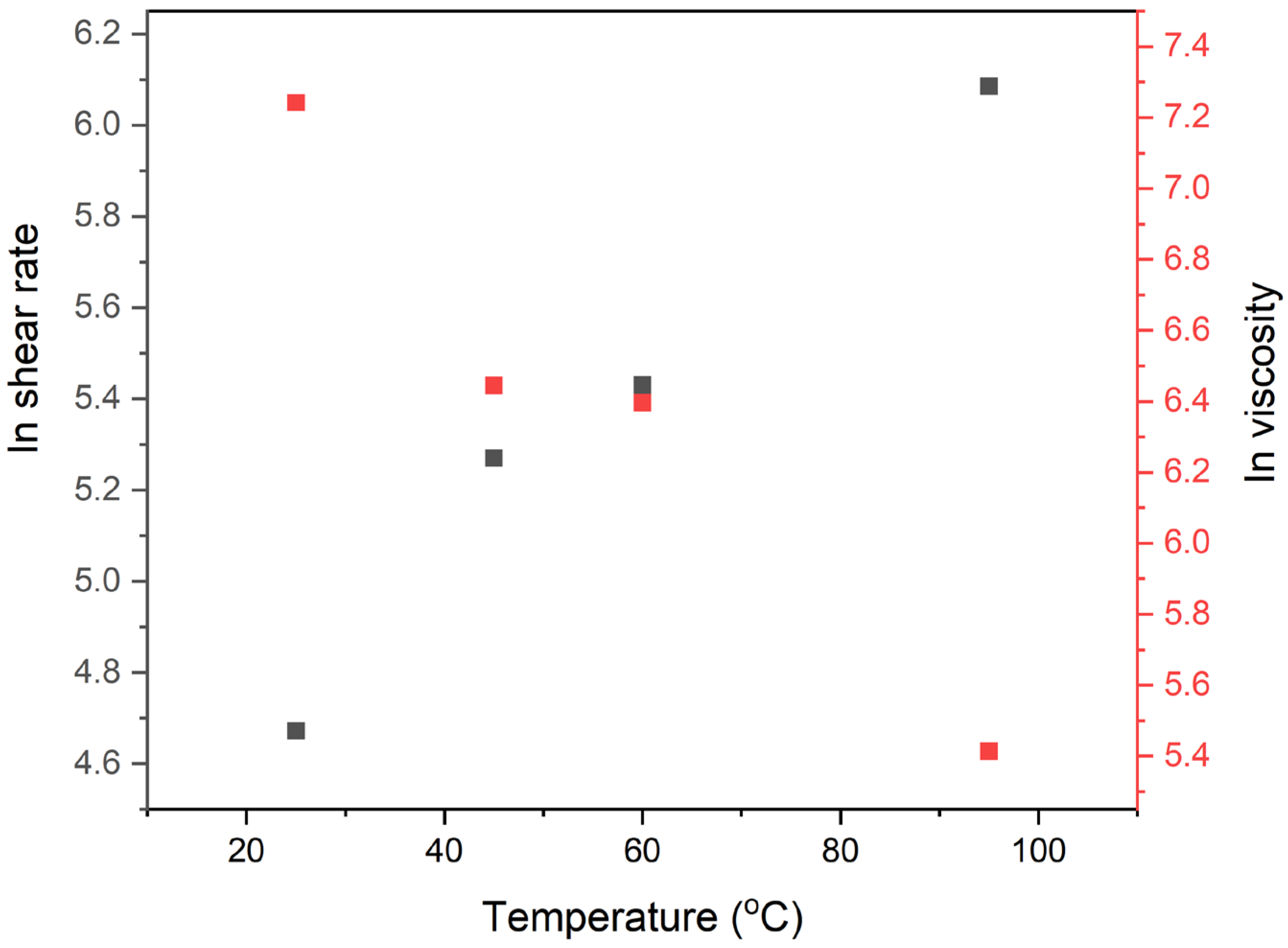

Figure 2 shows the variation of the critical shear rate and Newtonian (plateau) viscosity with the testing temperature. The steady-state plateau viscosity decreases while the critical shear rate increases with increasing temperature. The intersection of the critical shear rate versus temperature curve and the steady state viscosity versus temperature curve which occurred at 60°C corresponding to the critical shear rate of 220 s

-1 and viscosity of 600 cP, is indicative of the optimal rheological condition.

Figure 2 also shows that as testing temperature increases, the steady-state viscosity decreases from approximately 1000 cP at 25°C to 300 cP at 95°C, indicating that the polymer fluid flows better at higher temperatures. Concurrently, the critical shear rate, marking the transition from Power Law flow behavior to Newtonian flow behavior, increases from about 120 s

−1 at 25°C to 365 s

−1 at 95°C. These observations indicate that PAA solution shows a distinctive two regions of rheological behavior composed of a rheological dilatancy region at low shear rates followed by a steady-state Newtonian region characterized by invariant viscosity at moderate to higher shear rates.

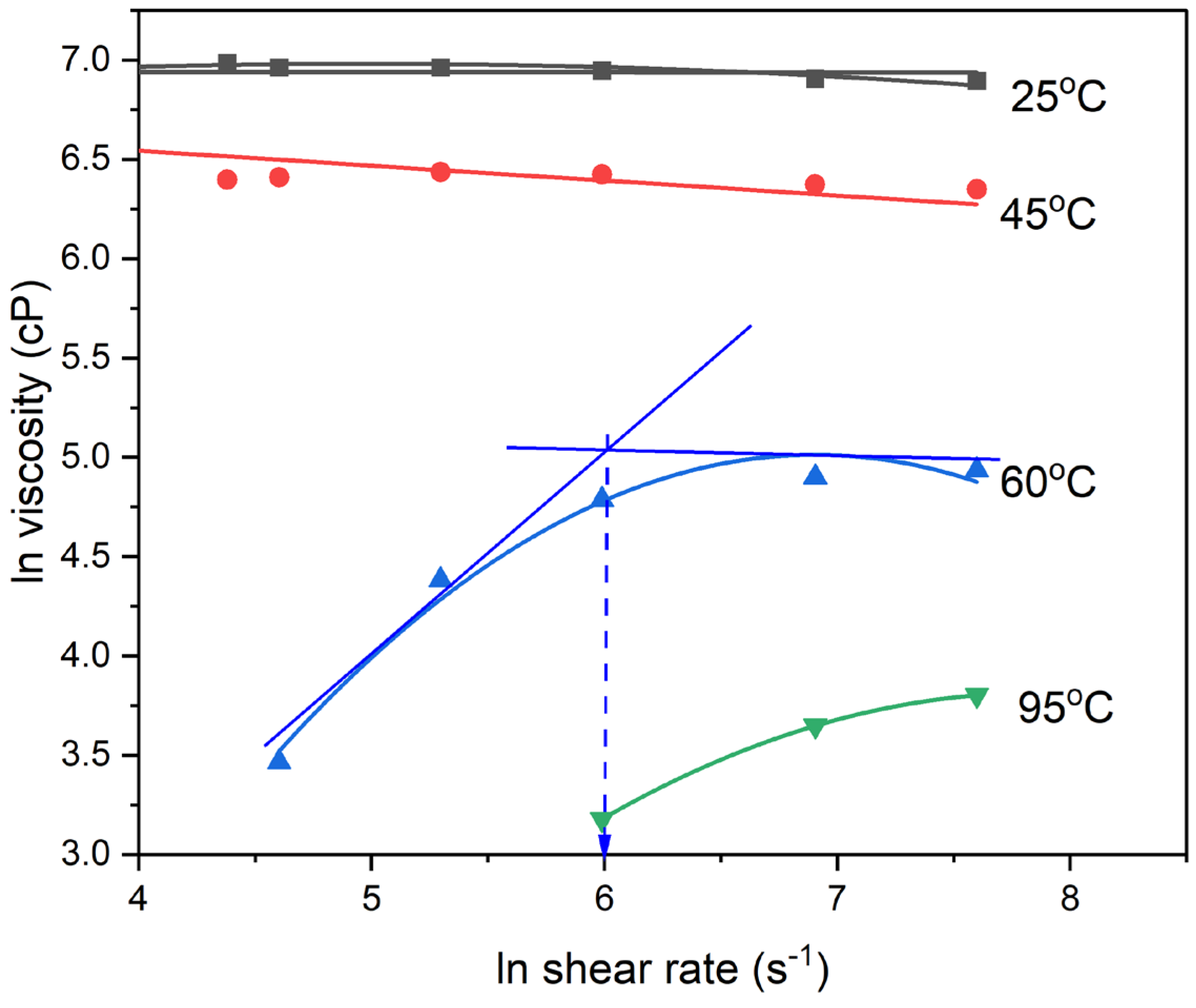

Figure 3 shows the dependence of viscosity on shear rate and testing temperature for PAA-PNEA suspension. It shows a nearly Newtonian behavior at low testing temperatures of 25 and 40˚C and a shear thickening-to-Newtonian flow behavior at higher testing temperatures, of 60 and 95˚C. Analysis of the first region of rheological behavior of the PAA/PNEA clay suspension at 60 and 95˚C, indicate a Power Law index of about 2, which is consistent with shear thickening behavior. The inclusion of PNEA clay into PAA solution significantly reduces the steady state viscosity. This suggests that the modified clay particles disrupt the polymer matrix, facilitating polymer chain mobility and reducing resistance to flow. The addition of PNEA clay reduces the viscosity of the PAA solution across all temperatures and significantly modifies the rheological behavior of the solution. This behavior can be attributed to the modified clay particles' ability to facilitate poly(amic acid) chain mobility and reduce chain entanglement, leading to decreased flow resistance.

Figure 3 also shows that as the testing temperature increases, the PAA's solution transition from Power Law flow to Newtonian flow behavior becomes more pronounced. At higher temperatures (60°C and 95°C), both neat PAA solution and the PAA/PNEA clay suspension are characterized by lower plateau Newtonian viscosity and higher critical shear rates, indicating compliance with both the Arrhenius law and Oswald-de Waele Law.

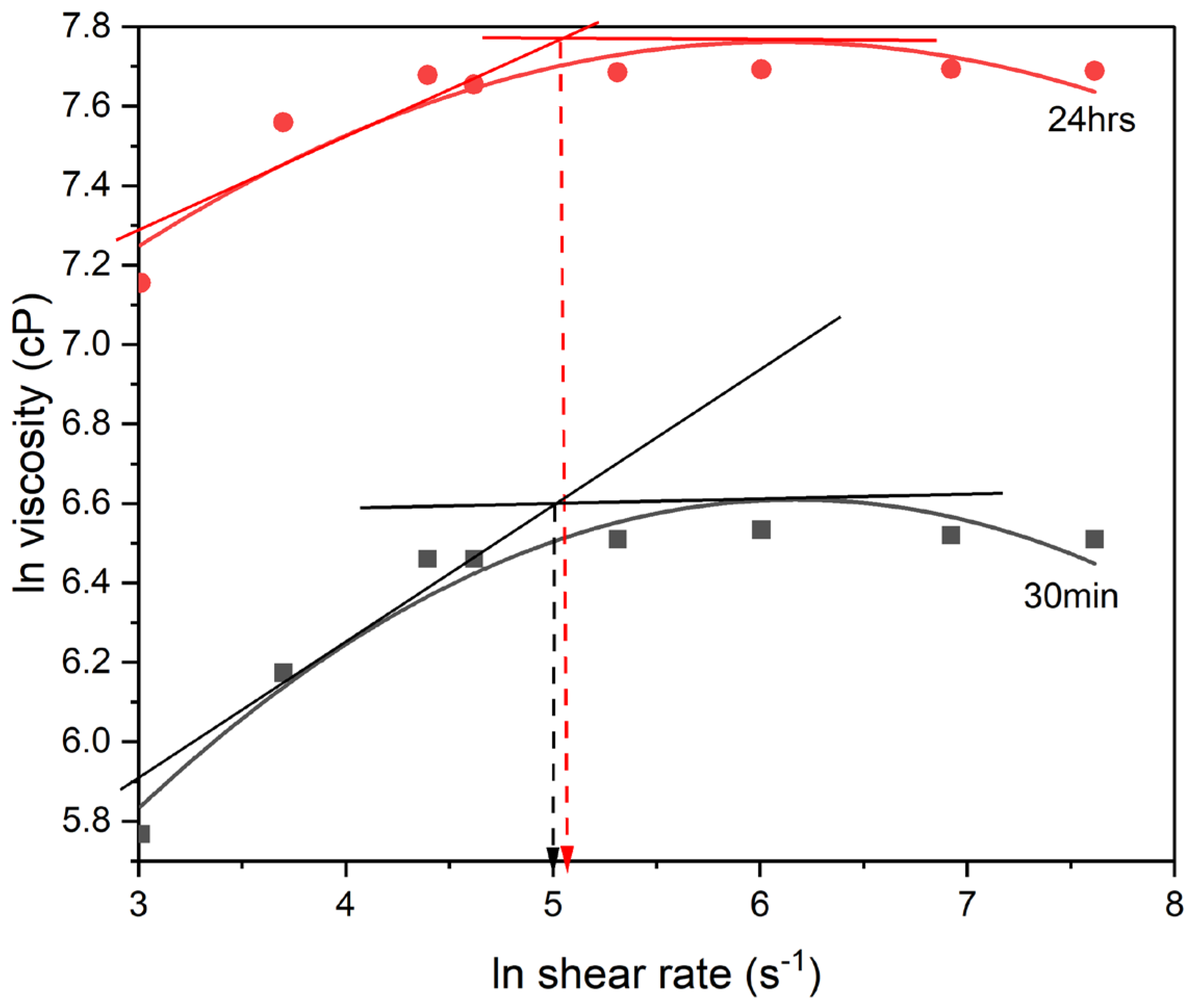

Figure 4 shows the dependence of viscosity on polymerization time and shear rate. Viscosity of the polymerizing solution increases with polymerization time and shear rate.

Figure 4 also compares the rheological behavior of neat poly(amic acid) (PAA) polymerizing solution at two different polymerization time intervals of 30 and 1440 minutes of polymerization, respectively. It provides a useful insight into how the viscosity of the PAA polymerizing solution changes over reaction time. It is shown that the viscosity of the PAA reaction solution increases significantly after 30 minutes of polymerization. This is evident from the higher steady-state viscosity obtained after 24 hours of polymerization of 2440 cP when compared to that obtained at one 1/2 hour of polymerization of 735 cP. The increase in viscosity with polymerization time, suggests that the molecular weight of the PAA polymerizing solution increased with polymerization time in accordance with the step growth polymerization kinetic model. The Carothers kinetic model for step growth polymerization shows that the molecular weight (Mw) of the polymer formed will increase with increasing polymerization time (t):

, Where

is the molar mass of the repeat unit, k is the rate constant for polycondensation,

is the initial monomer concentration and t is the polymerization time. The variation of viscosity with shear rate shows a common pattern of initially increasing viscosity with shear rate up to a critical shear rate beyond which viscosity remains constant and does not change significantly with increasing shear rate. The first region of rheological behavior maybe due to a combination of factors including increasing molecular weight and solvent removal as a result of increasing shear rate. The second region where Newtonian flow behavior is observed, can be associated with the existence of some form of structural equilibrium in the system.

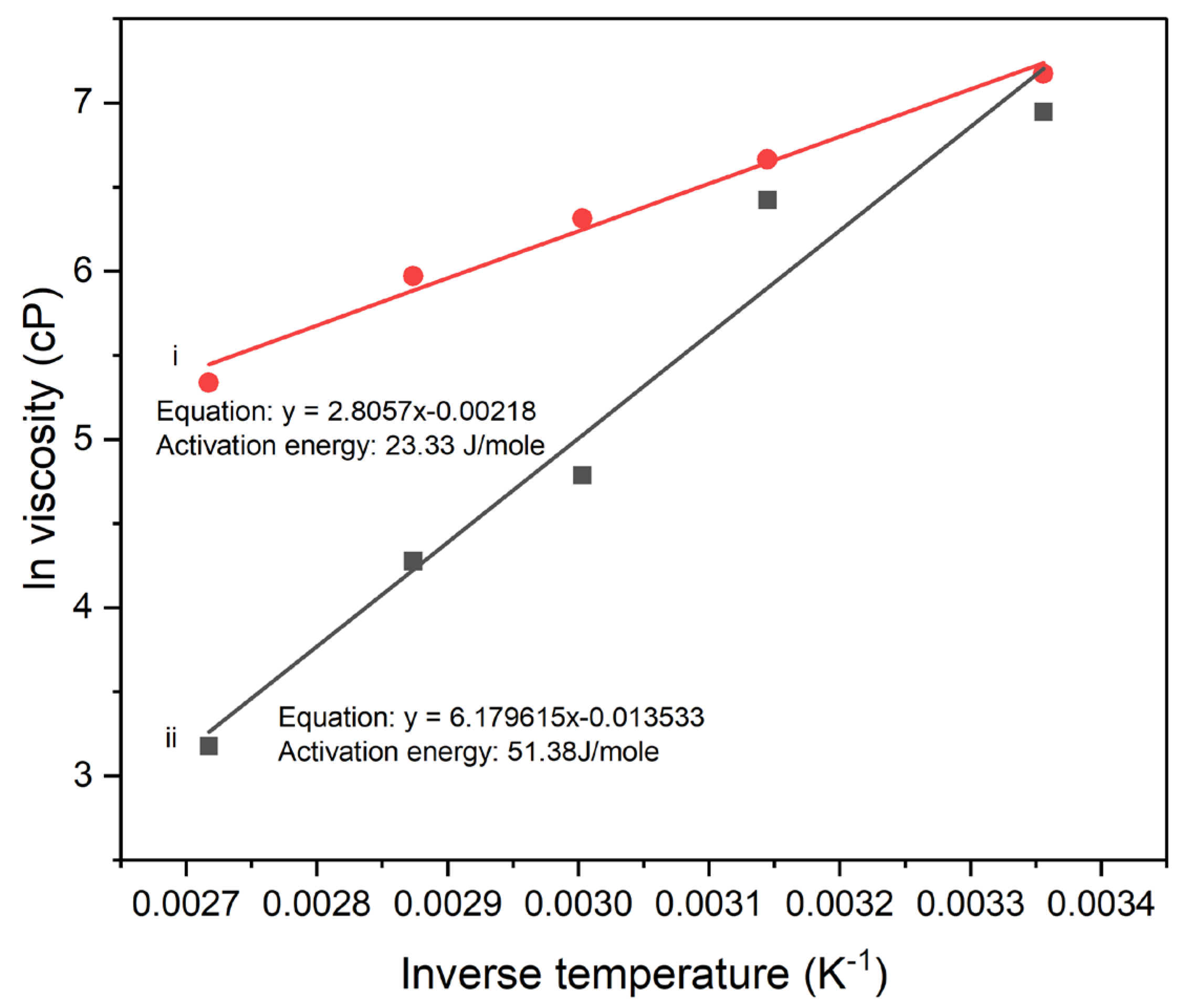

Figure 5 shows the relationship between viscosity and temperature for the neat poly(amic acid) (PAA) solution and PAA solution mixed with 5wt% polyaniline copolymer (PNEA) modified clay, respectively. Both systems show an inverse relationship between viscosity and temperature in accordance with the Arrhenius Law:

, Where h is the temperature dependent viscosity,

is the zero shear rate viscosity,

is the activation energy, R is the gas constant and T is the absolute temperature. This behavior is typical for polymer solutions, where higher temperatures reduce the viscosity, facilitating easier flow. The neat PAA solution, shows a higher initial viscosity at lower temperatures and a steeper decrease as temperature increases. The zero-shear rate viscosity for neat PAA solution is about 1480 cP. PAA/PNEA clay suspension has a slightly lower initial viscosity compared to neat PAA solution and shows a sharper decrease in viscosity with increasing temperature. The zero-shear rate viscosity for the PAA/PNEA clay suspension is 990 cP. The activation energy for viscous flow for neat PAA solution is 23 J/mole which is lower than that for PAA solution containing 5wt.% polyaniline copolymer modified clay of 51 J/mole, suggesting that the presence of 5wt.% polyaniline modified clay may reduce processability of PAA.

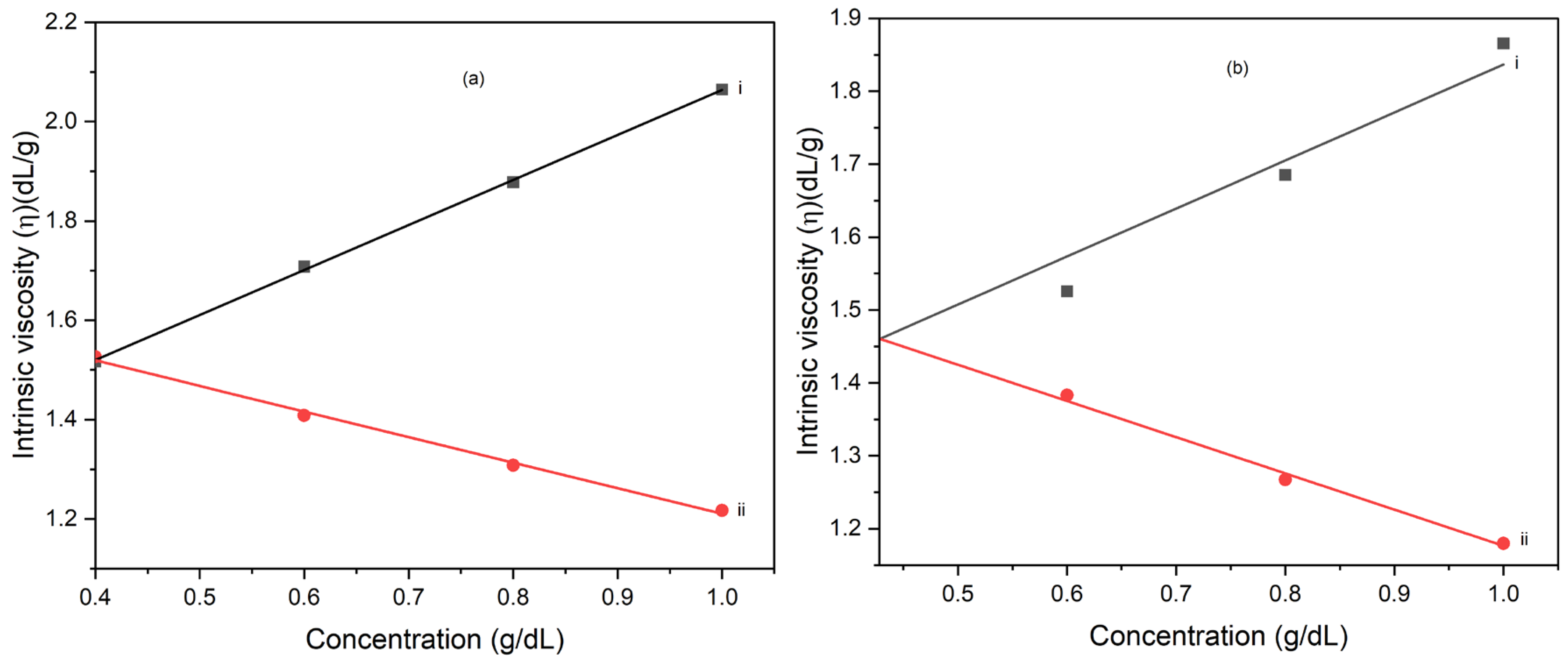

Figure 6a and b show the dependence of the reduced viscosity, and inherent viscosity on solution concentration for the neat poly(amic acid), PAA solution (a) and poly(amic acid) suspension containing 5wt% polyaniline copolymer modified clay, PNEA (b). The intercept of the reduced viscosity versus concentration curve and that for inherent viscosity versus concentration curve gives the intrinsic viscosity, [h]. The intrinsic viscosity, for the PAA solution is about 1.52 dL/g. This value reflects the hydrodynamic volume occupied by the polymer chains in the solution.

Figure 6b shows the analysis of the dilute solution viscometry of PAA suspension containing 5wt% PNEA. The intrinsic viscosity for the PAA/5wt.% PNEA clay suspension is about 1.46 dL/g, which is slightly lower than that for neat PAA solution. The presence of PNEA modified clay in the PAA solution slightly decreases the later’s intrinsic viscosity. This result suggests that the modified clay fillers may interfere with the solvent-polymer interaction, resulting in slightly lowered hydrodynamic volume of the polymer chain.

3.2. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

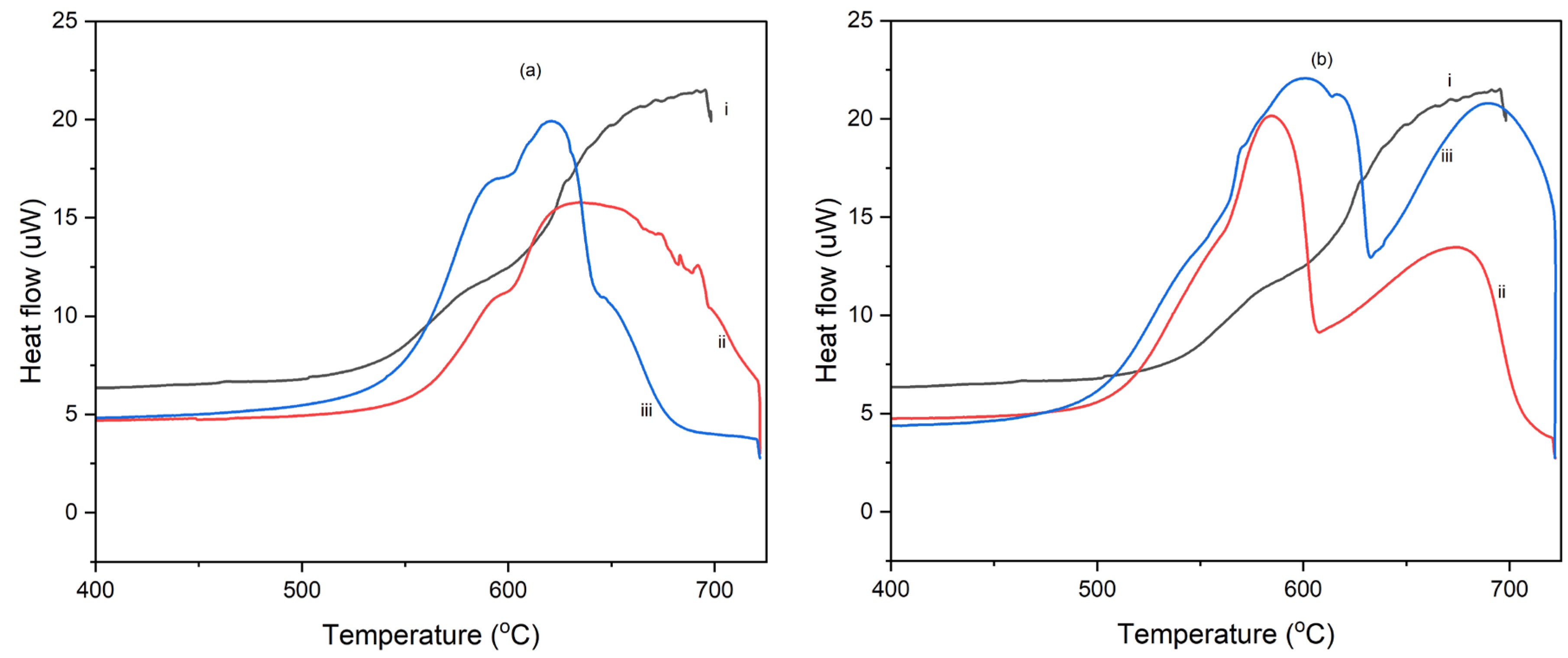

Figure 7a and b show the DSC thermograms of polyimide-nanographene sheet composites (PI-NGC) containing 10 and 40 wt.% graphene produced following the standard solution casting method and those produced by initially shearing the mixture in a Brookfield Viscometer at spindle speed of 100 rpm for 30 minutes, before solution casting.

Figure 7a shows the DSC thermograms for polyimide nanocomposite containing 10 wt.% nanographene sheets, PI-10 wt.%. The composite film obtained after subjecting the mixture to high speed shearing of 100 rpm in the Brookfield viscometer, has a lower decomposition energy peak height and lower total heat of decomposition than the nanographene sheets/polyimide nanocomposites of the same composition, PI-10 wt.% graphene produced without high speed shearing. This indicates that exposure of the mixture to high shearing after the standard processing protocol, improved the composite thermal properties by enhancing solvent removal resulting in a dense and oriented film structure. Similar to

Figure 7a, the DSC thermograms for the nanocomposite containing 40 wt.% graphene sheets, PI-40 wt.% has a lower decomposition energy peak height and lower energy of decomposition than the PI-40 wt.% nanocomposite processed without the additional high spindle speed shearing step (

Figure 7b). This improvement in thermal stability of the high speed sheared composites is believed to be due to enhanced graphene sheet distribution and orientation, and improved densification of the composite material. Comparing the two figures, it is evident that the nanocomposite with higher graphene content (40 wt.%) had higher thermal stability (

Figure 7b). The combination of high graphene concentration and high spindle speed shearing improved the thermal stability and fire-retardant properties of the composites. The neat PI matrix has a higher decomposition energy peak height, indicating lower thermal stability compared to the polyimide-nanographene sheets composites. The presence of nanographene sheets significantly increased the total decomposition time and lowered the heat of decomposition, and therefore enhanced the thermal stability of the PI matrix.

3.3. Cyclic Voltammetry

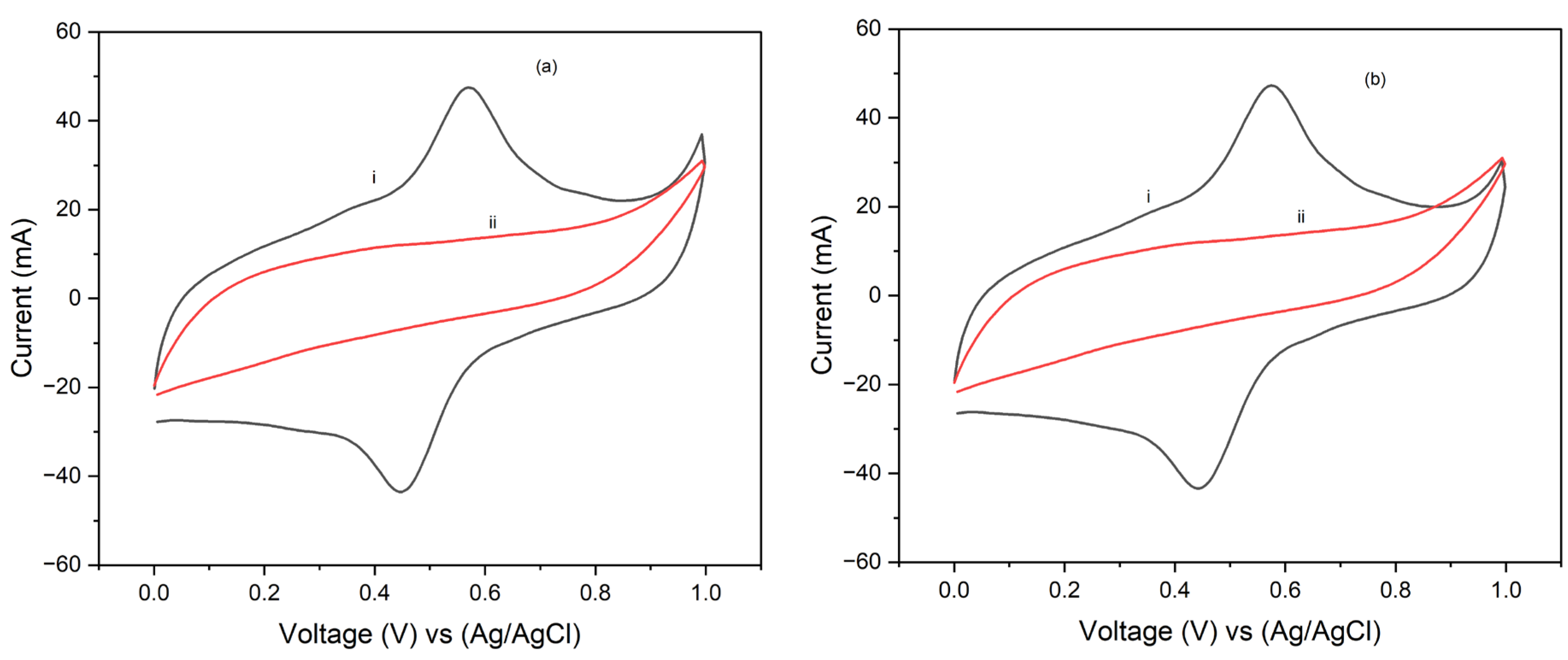

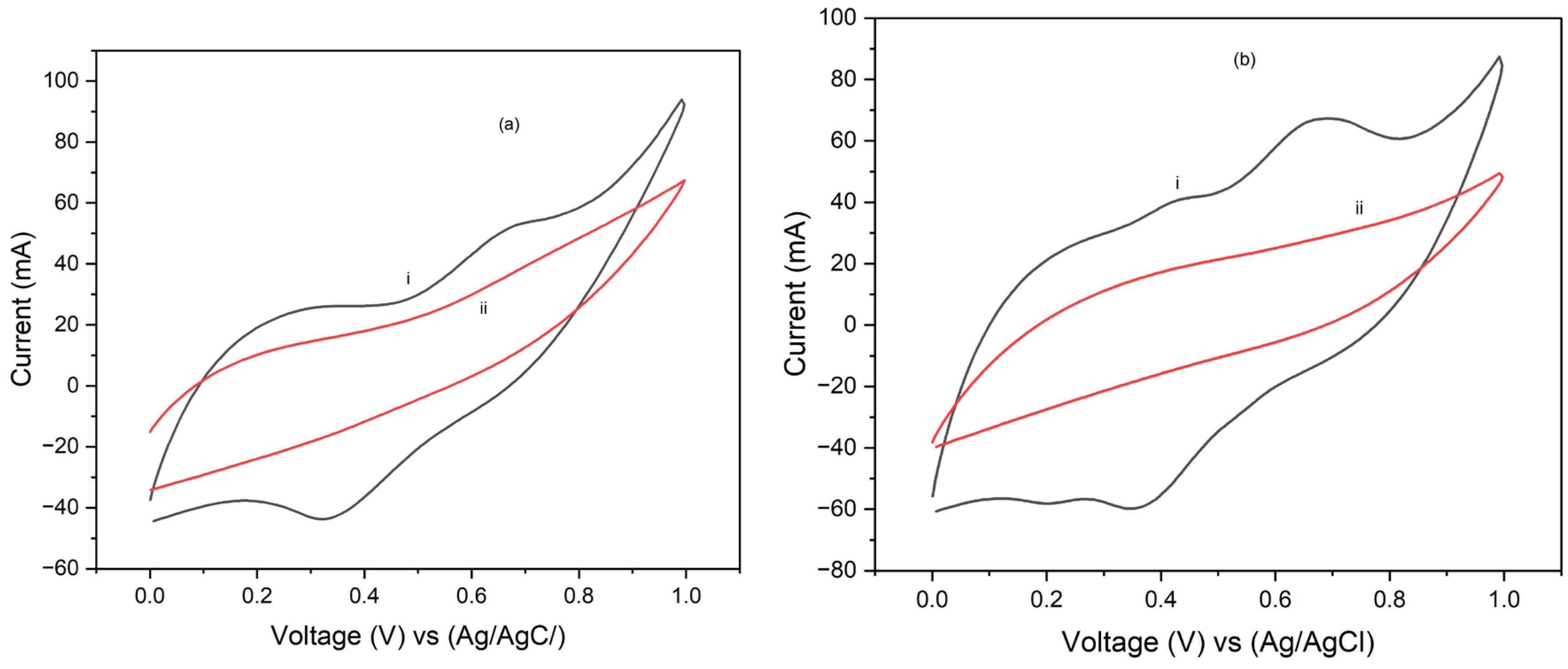

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 show the cyclic voltammgrams (CV) for PI/carbon nanotube (CNT) sheets hybrid nanocomposites processed at 90°C and 250°C, respectively, and coated with electropolymerized polypyrrole (PPy). The CV results show that the hybrid nanocomposite electrode processed at 90°C is pseudosupercapacitive characterized by both redox reactions and double layer capacitive behavior. It also produced higher stored charge and consequently higher specific capacitance than to that processed at 250°C. Specifically, at a scan rate of 5 mV/s, the specific capacitance for the PPy coated sample processed at 90°C was about 858.154 F/g after one cycle. The specific capacitance for this composite decreased slightly to 802 F/g after 10 cycles. However, at a scan rate of 25 mV/s, the specific capacitance for the PPy coated electrode processed at 90°C was 345 F/g after one cycle but increased to 374 F/g after 10 cycles. Interestingly, the composites processed at 250°C produced a specific capacitance of 136 F/g after 1 cycle at a scan rate of 5 mV/s, which increased to 156 F/g after 10 cycles of testing. However, tests done at a scan rate of 25 mV/s, produced specific capacitance of 74 F/g after 1 cycle which decreased slightly to 61 F/g in 10 cycles. These results indicate that increasing scan rate, resulted in decreased specific capacitance. However, a slight decrease in the specific capacitance with increasing number of cycles of CV test was observed. The observed increase in the total stored charge and specific capacitance at the low scan rate is attributed to the longer time available for the electrochemical processes. Conversely, the low specific capacitance obtained at higher scan rate is attributed to the shorter time that is available for the electrochemical processes. It is suggested that controlling the processing temperature and time is crucial to optimizing the performance of the composite electrode materials for application in pseudosupercapacitors and batteries, where high specific capacitance and efficient charge-discharge cycles are desirable.

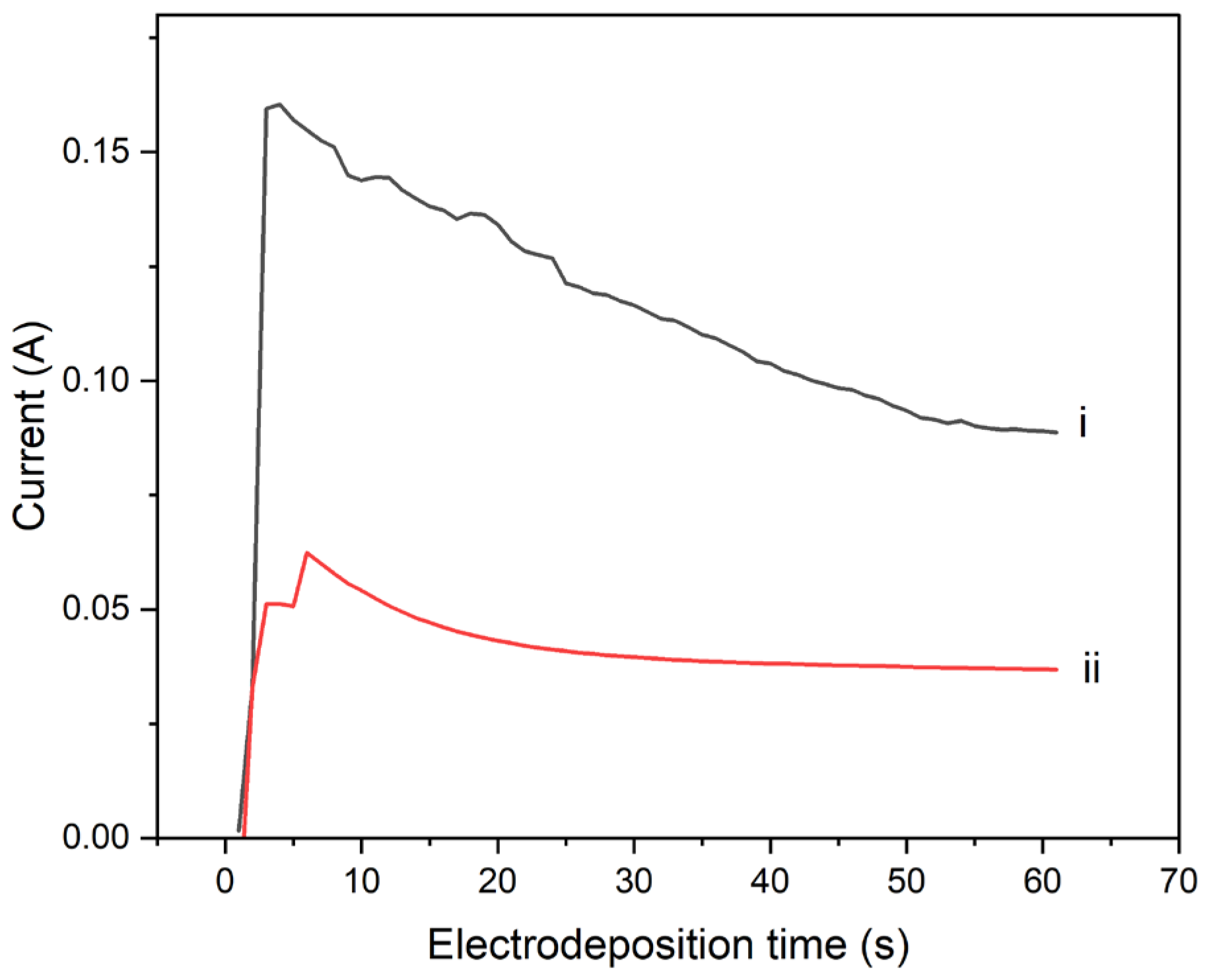

Current-time, I-t Transient Curves

Figure 10 shows the transient current–time curves obtained during the potentiostatic electrochemical polymerization of pyrrole onto composite PI/CNT/PVDF working electrode processed at 90°C and 250°C, respectively. The composite electrode processed at 90˚C has a peak and a steady-state current of 0.15 A and 0.10 A, respectively, which are higher than the peak current and steady-state current of 0.06A and 0.04A, respectively, obtained for composite working eelectrode processed at 250°C. This finding suggests that the electropolymerization of pyrrole is favored on the composite electrode processed at lower temperature of 90°C, than the electrode material processed at 250˚C. Potentiostatic polymerization of pyrrole onto the hybrid CNT-PVDF-PI electrode at an applied voltage of 2V, for 60 seconds, resulted in a lower electrode resistance for the composite processed at 90˚C than that processed at 250˚C. The current-time transient curve for polymerization conducted by using the hybrid electrode processed at 90°C has higher peak current and higher steady-state current than those for the hybrid working electrode processed at 250˚C. These results, therefore, underscore the importance of processing temperature, in controlling the electrochemical properties of the electrode material.

4.0. Conclusion

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of the rheological, thermal, and electrochemical behavior of poly(amic acid) (PAA) and PAA suspension containing nanofillers. The neat PAA solution exhibited a Power law to Newtonian rheological behavior. Irrespective of the test temperatures, a Power law exponent of 2 was obtained, which is indicative of shear thickening behavior. The critical shear rate for transition from shear thickening to the Newtonian behavior increased with increasing temperature, occurring at approximately (148 s-1) at 45°C, (244 s-1) at 60°C, and (403 s-1) at 95°C. The PAA/5wt% PNEA clay suspension also shows shear-thickening behavior at low shear rates at all temperatures. However, the plateau Newtonian viscosity for the suspension was significantly lower than that for the neat PAA solution tested at same temperature. This indicates enhanced polymer chain mobility and reduced flow resistance due to the modified clay particles.

DSC results indicate that the PI nanocomposites processed after an additional high spindle speed shearing of the suspension for 30 minutes, had lower total heat of decomposition, which is indicative of enhanced fire retardancy.

Cyclic voltammetry results for PPy-PI/CNT-PVDF nanocomposite electrodes show that the electrode material processed at 90°C was more conductive than that processed at 250˚C. The 90°C processed sample has higher current responses during potentiostatic electropolymerization of pyrrole and total charge stored in this system is significantly higher than that for the electrode processed at 250˚C, making it more suitable for energy storage applications.

The rheological data obtained suggests that PAA suspension containing polyaniline copolymer modified clay showed improved flow characteristics, making it easier to process. The reduction in the plateau viscosity and enhanced shear-thickening behavior of the suspension indicates improved proceessability of the composites.

The improved fire retardancy of nanographene sheets filled polyimide is particularly beneficial for safety-critical applications in the aerospace, automotive, and electronics industries.

The superior electrochemical performance of the 90°C processed PI hybrid nanocomposite makes it suitable for energy storage applications such as pseudosupercapacitors and batteries, where high specific capacitance and efficient charge-discharge cycles are essential. This work uniquely combines rheological analysis with thermal and electrochemical characterization to provide a comprehensive understanding of how nanofillers and processing conditions affect the performance of hybrid PI nanocomposites. This combinatorial approach offers valuable insights into optimizing material properties. The study highlights the impact of nanofillers on the rheological, thermal, and electrochemical properties of hybrid PI nanocomposites. The findings reveal that the nanofillers not only modify the flow properties but also enhance fire resistance, and electrochemical properties of the nanocomposites. By demonstrating the complex interplay between rheological, thermal, and electrochemical properties, this study paves the way for developing advanced PI-based materials with tailored properties for specific industrial applications, thus broadening the scope of PI usage in emerging technologies.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Acknowledgment

The support provided by the Mechanical and Materials Engineering Department and the Polymer Laboratory at the University of Cincinnati, is hereby acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ioan, S., Filimon, A., Hulubei, C. and Popovici, D., 2012. Rheological properties of some complex polymers containing alicyclic structures. HEFAT 2012.

- Jin, J.U., Hahn, J.R. and You, N.H., 2022. Structural Effect of Polyimide Precursors on Highly Thermally Conductive Graphite Films. ACS omega, 7(29), pp.25565-25572. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Iroh, J.O. and Long, A., 2012. Controlling the structure and rheology of polyimide/nanoclay composites by condensation polymerization. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 125(S1), pp.E486-E494. [CrossRef]

- Sezer Hicyilmaz, A. and Celik Bedeloglu, A., 2021. Applications of polyimide coatings: A review. SN Applied Sciences, 3, pp.1-22. [CrossRef]

- Ioan, S., Filimon, A., Hulubei, C., Stoica, I. and Dunca, S., 2013. Origin of rheological behavior and surface/interfacial properties of some semi-alicyclic polyimides for biomedical applications. Polymer bulletin, 70, pp.2873-2893. [CrossRef]

- Njuguna, J., Pielichowski, K. and Fan, J., 2012. Polymer nanocomposites for aerospace applications. Advances in Polymer Nanocomposites, pp.472-539. [CrossRef]

- Marashdeh, W.F., Longun, J. and Iroh, J.O., 2016. Relaxation behavior and activation energy of relaxation for polyimide and polyimide–graphene nanocomposite. Journal of applied polymer science, 133(28). [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, A.D. and Beatrice, C.A.G., 2018. Polymer nanocomposites with different types of nanofiller. Nanocomposites-Recent Evolutions, pp.103-104. [CrossRef]

- Armentano, I., Dottori, M., Fortunati, E., Mattioli, S. and Kenny, J.M., 2010. Biodegradable polymer matrix nanocomposites for tissue engineering: a review. Polymer degradation and stability, 95(11), pp.2126-2146. [CrossRef]

- Zou, H., Wu, S. and Shen, J., 2008. Polymer/silica nanocomposites: preparation, characterization, properties, and applications. Chemical reviews, 108(9), pp.3893-3957. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Ahmed, R. and Lee, S.J., 2001. Synthesis and linear viscoelastic behavior of poly (amic acid)–organoclay hybrid. Journal of applied polymer science, 80(4), pp.592-603. [CrossRef]

- Liaw, D.J., Wang, K.L., Huang, Y.C., Lee, K.R., Lai, J.Y. and Ha, C.S., 2012. Advanced polyimide materials: Syntheses, physical properties and applications. Progress in Polymer Science, 37(7), pp.907-974. [CrossRef]

- Mathews, A.S., Kim, I. and Ha, C.S., 2007. Synthesis, characterization, and properties of fully aliphatic polyimides and their derivatives for microelectronics and optoelectronics applications. Macromolecular Research, 15, pp.114-128. [CrossRef]

- Tafreshi, O.A., Ghaffari-Mosanenzadeh, S., Karamikamkar, S., Saadatnia, Z., Kiddell, S., Park, C.B. and Naguib, H.E., 2022. Novel, flexible, and transparent thin film polyimide aerogels with enhanced thermal insulation and high service temperature. Journal of Materials Chemistry C, 10(13), pp.5088-5108. [CrossRef]

- Hergenrother, P.M., 2003. The use, design, synthesis, and properties of high performance/high temperature polymers: an overview. High Performance Polymers, 15(1), pp.3-45. [CrossRef]

- Ma, P., Dai, C., Wang, H., Li, Z., Liu, H., Li, W. and Yang, C., 2019. A review on high temperature resistant polyimide films: Heterocyclic structures and nanocomposites. Composites Communications, 16, pp.84-93. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W., Yang, T., Qu, L., Liang, X., Liu, C., Qian, C., Zhu, T., Zhou, Z., Liu, C., Liu, S. and Chi, Z., 2022. Temperature resistant amorphous polyimides with high intrinsic permittivity for electronic applications. Chemical Engineering Journal, 436, p.135060. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.L., Song, C., Wei, M.H., Huang, Z.Z. and Sheng, S.R., 2019. Organosoluble and transparent cardo polyimides with high T g derived from 9, 9-bis (4-aminophenyl) xanthene. High Performance Polymers, 31(8), pp.909-918. [CrossRef]

- Woo, H.G., Li, H., Ha, C.S. and Mathews, A.S., 2011. Polyimides and high performance organic polymers. Advanced functional materials, pp.1-36. [CrossRef]

- Agag, T., Koga, T. and Takeichi, T., 2001. Studies on thermal and mechanical properties of polyimide–clay nanocomposites. Polymer, 42(8), pp.3399-3408. [CrossRef]

- Bourbigot, S., Devaux, E. and Flambard, X., 2002. Flammability of polyamide-6/clay hybrid nanocomposite textiles. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 75(2), pp.397-402. [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, S.H., Liou, G.S. and Chang, L.M., 2001. Synthesis and properties of organosoluble polyimide/clay hybrids. Journal of applied polymer science, 80(11), pp.2067-2072. [CrossRef]

- Akinyi, C., Longun, J., Chen, S. and Iroh, J.O., 2021. Decomposition and flammability of polyimide graphene composites. Minerals, 11(2), p.168. [CrossRef]

- Longun, J. and Iroh, J.O., 2023. Fabrication of High Impact-Resistant Polyimide Nanocomposites with Outstanding Thermomechanical Properties. Polymers, 15(22), p.4427. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.H., Yeh, J.M., Liou, S.J., Chen, C.L., Liaw, D.J. and Lu, H.Y., 2004. Preparation and properties of polyimide–clay nanocomposite materials for anticorrosion application. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 92(6), pp.3573-3582. [CrossRef]

- Khayankarn, O., Magaraphan, R. and Schwank, J.W., 2003. Adhesion and permeability of polyimide–clay nanocomposite films for protective coatings. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 89(11), pp.2875-2881. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadizadegan, H. and Esmaielzadeh, S., 2020. Synthesis and characterization of novel polyimide/clay nanocomposites and processing, properties and applications. International Journal of Polymer Analysis and Characterization, 25(8), pp.604-620. [CrossRef]

- Ni, H.J., Liu, J.G., Wang, Z.H. and Yang, S.Y., 2015. A review on colorless and optically transparent polyimide films: Chemistry, process and engineering applications. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, 28, pp.16-27. [CrossRef]

- Espuche, E., David, L., Rochas, C., Afeld, J.L., Compton, J.M., Thompson, D.W., Thompson, D.S. and Kranbuehl, D.E., 2005. In situ generation of nanoparticulate lanthanum (III) oxide-polyimide films: characterization of nanoparticle formation and resulting polymer properties. Polymer, 46(17), pp.6657-6665. [CrossRef]

- Chieruzzi, M., Miliozzi, A. and Kenny, J.M., 2013. Effects of the nanoparticles on the thermal expansion and mechanical properties of unsaturated polyester/clay nanocomposites. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing, 45, pp.44-48. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, F., Hojjati, M., Okamoto, M. and Gorga, R.E., 2006. Polymer-matrix nanocomposites, processing, manufacturing, and application: an overview. Journal of composite materials, 40(17), pp.1511-1575. [CrossRef]

- Mokhothu, T.H., Mtibe, A., Mokhena, T.C., Mochane, M.J., Ofosu, O., Muniyasamy, S., Tshifularo, C.A. and Motsoeneng, T.S., 2019. Mechanical, thermal and viscoelastic properties of polymer composites reinforced with various nanomaterials. Sustainable Polymer Composites and Nanocomposites, pp.185-213. [CrossRef]

- Panwar, V. and Pal, K., 2017. Dynamic mechanical analysis of clay–polymer nanocomposites. In Clay-polymer nanocomposites (pp. 413-441). Elsevier.

- Costa, F.R., Saphiannikova, M., Wagenknecht, U. and Heinrich, G., 2008. Layered double hydroxide based polymer nanocomposites. Wax Crystal Control· Nanocomposites· Stimuli-Responsive Polymers, pp.101-168. [CrossRef]

- Judah, H., 2020. The synthesis, characterisation and rheological properties of clay-polymer nanocomposites. Sheffield Hallam University (United Kingdom).

- Hamming, L.M., Qiao, R., Messersmith, P.B. and Brinson, L.C., 2009. Effects of dispersion and interfacial modification on the macroscale properties of TiO2 polymer–matrix nanocomposites. Composites science and technology, 69(11-12), pp.1880-1886. [CrossRef]

- Mousa, M., Evans, N.D., Oreffo, R.O. and Dawson, J.I., 2018. Clay nanoparticles for regenerative medicine and biomaterial design: A review of clay bioactivity. Biomaterials, 159, pp.204-214. [CrossRef]

- Szazdi, L., Pozsgay, A. and Pukanszky, B., 2007. Factors and processes influencing the reinforcing effect of layered silicates in polymer nanocomposites. European Polymer Journal, 43(2), pp.345-359. [CrossRef]

- Müller, K., Bugnicourt, E., Latorre, M., Jorda, M., Echegoyen Sanz, Y., Lagaron, J.M., Miesbauer, O., Bianchin, A., Hankin, S., Bölz, U. and Pérez, G., 2017. Review on the processing and properties of polymer nanocomposites and nanocoatings and their applications in the packaging, automotive and solar energy fields. Nanomaterials, 7(4), p.74. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. and Tripathi, A., 2005. Intrinsic viscosity of polymers and biopolymers measured by microchip. Analytical chemistry, 77(22), pp.7137-7147. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y., An, L. and Wang, Z.G., 2013. Intrinsic viscosity of polymers: General theory based on a partially permeable sphere model. Macromolecules, 46(14), pp.5731-5740. [CrossRef]

- Nunez, C.M., Chiou, B.S., Andrady, A.L. and Khan, S.A., 2000. Solution rheology of hyperbranched polyesters and their blends with linear polymers. Macromolecules, 33(5), pp.1720-1726. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q. and Zhou, Z., 2013. Graphene-analogous low-dimensional materials. Progress in materials science, 58(8), pp.1244-1315. [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, G., Bolton-Warberg, M. and Awaja, F., 2021. Graphene and graphene oxide for bio-sensing: General properties and the effects of graphene ripples. Acta biomaterialia, 131, pp.62-79. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Yang, H., Sui, L., Jiang, S. and Hou, H., 2020. Self-Adhesive Polyimide (PI)@ Reduced Graphene Oxide (RGO)/PI@ Carbon Nanotube (CNT) Hierarchically Porous Electrodes: Maximizing the Utilization of Electroactive Materials for Organic Li-Ion Batteries. Energy Technology, 8(9), p.2000397. [CrossRef]

- Rathod, V.T., Kumar, J.S. and Jain, A., 2017. Polymer and ceramic nanocomposites for aerospace applications. Applied Nanoscience, 7, pp.519-548. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, J.C., Fidalgo-Marijuan, A., Dias, J.C., Gonçalves, R., Salado, M., Costa, C.M. and Lanceros-Méndez, S., 2023. Molecular design of functional polymers for organic radical batteries. Energy Storage Materials, p.102841. [CrossRef]

- Guo, W., Liu, C., Sun, X., Yang, Z., Kia, H.G. and Peng, H., 2012. Aligned carbon nanotube/polymer composite fibers with improved mechanical strength and electrical conductivity. Journal of Materials Chemistry, 22(3), pp.903-908. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Dai, J., Li, W., Wei, Z. and Jiang, J., 2008. The effects of CNT alignment on electrical conductivity and mechanical properties of SWNT/epoxy nanocomposites. Composites science and technology, 68(7-8), pp.1644-1648. [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.C., Liu, M.Y., Zhang, H., Wang, S.Q., Wang, R., Wang, K., Wong, Y.K., Tang, B.Z., Hong, S.H., Paik, K.W. and Kim, J.K., 2009. Enhanced electrical conductivity of nanocomposites containing hybrid fillers of carbon nanotubes and carbon black. ACS applied materials & interfaces, 1(5), pp.1090-1096. [CrossRef]

- Jaworska, E.; Michalska, A.; Maksymiuk, K. Polypyrrole Nanospheres–Electrochemical Properties and Application as a Solid Contact in Ion-selective Electrodes. Electroanalysis 2017, 29, 123–130. [CrossRef]

- Gooneratne, R.; Iroh, J.O., Polypyrrole Modified Carbon Nanotube/Polyimide Electrode Materials for Supercapacitors and Lithium-ion Batteries. Energies 2022, 15, 9509. [CrossRef]

- Gooneratne, R., Iroh, J.O., The effect of organic acid dopants on the specific capacitance of electrodeposited polypyrrole-carbon nanotube/polyimide composite electrodes, Energies 2023, 16(7462). [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Dependence of viscosity on the shear rate and temperature for neat PAA solution.

Figure 1.

Dependence of viscosity on the shear rate and temperature for neat PAA solution.

Figure 2.

Effect of temperature on the critical shear rate c and the steady state viscosity for the neat poly(amic acid) solution.

Figure 2.

Effect of temperature on the critical shear rate c and the steady state viscosity for the neat poly(amic acid) solution.

Figure 3.

Effect of shear rate and temperature on the viscosity of poly(amic acid) suspension containing 5wt% of polyaniline copolymer, PNEA modified Cloisite 30B clay.

Figure 3.

Effect of shear rate and temperature on the viscosity of poly(amic acid) suspension containing 5wt% of polyaniline copolymer, PNEA modified Cloisite 30B clay.

Figure 4.

Effect of shear rate and polymerization time on the viscosity of poly(amic acid) after 30 minutes and 24 hours, respectively, of polymerization.

Figure 4.

Effect of shear rate and polymerization time on the viscosity of poly(amic acid) after 30 minutes and 24 hours, respectively, of polymerization.

Figure 5.

Plots of ln Viscosity (cP) Vs Inverse Temperature (K-1) at a spindle speed rate of 20 rpm for (i) neat PAA sample and (ii) PAA suspension containing 5w% PNEA.

Figure 5.

Plots of ln Viscosity (cP) Vs Inverse Temperature (K-1) at a spindle speed rate of 20 rpm for (i) neat PAA sample and (ii) PAA suspension containing 5w% PNEA.

Figure 6.

(a) Plot of (i) inherent viscosity and (ii) reduced viscosity against concentration for, (a) PAA solution and (b) PAA suspension containing 5 wt.% PNEA modified clay.

Figure 6.

(a) Plot of (i) inherent viscosity and (ii) reduced viscosity against concentration for, (a) PAA solution and (b) PAA suspension containing 5 wt.% PNEA modified clay.

Figure 7.

(a) DSC thermograms of (i) Neat PI, (ii) PI-10 wt.% nanographene sheet sheared at 100 rpm for 30 minutes, and (iii) PI-10 wt.% graphene and (b) DSC curves of (i) Neat PI, (ii) PI-40 wt.% graphene cast after shearing the suspension at 100rpm for 30 minutes, and (iii) PI-40 wt.% graphene cast without additional sheearing of the suspension. DSC test was conducted under nitrogen atmosphere at a heating rate of 5 °C/minute.

Figure 7.

(a) DSC thermograms of (i) Neat PI, (ii) PI-10 wt.% nanographene sheet sheared at 100 rpm for 30 minutes, and (iii) PI-10 wt.% graphene and (b) DSC curves of (i) Neat PI, (ii) PI-40 wt.% graphene cast after shearing the suspension at 100rpm for 30 minutes, and (iii) PI-40 wt.% graphene cast without additional sheearing of the suspension. DSC test was conducted under nitrogen atmosphere at a heating rate of 5 °C/minute.

Figure 8.

5 mV/s cyclic voltammograms of PI/CNT/PVDF samples cured at (i) 90oC and (ii) 250oC nanocomposite electrode with doped PPy using an Ag/AgCl reference electrode for (a) Cycle 1 and (b) Cycle 10.

Figure 8.

5 mV/s cyclic voltammograms of PI/CNT/PVDF samples cured at (i) 90oC and (ii) 250oC nanocomposite electrode with doped PPy using an Ag/AgCl reference electrode for (a) Cycle 1 and (b) Cycle 10.

Figure 9.

25 mV/s cyclic voltammograms of PPy-PI/CNT/PVDF hybrid composite electrode processed at (i) 90oC and (ii) 250oC, using an Ag/AgCl reference electrode and graphite rod counter electrode for the (a) 1st and (b) 10th cycles, respectively.

Figure 9.

25 mV/s cyclic voltammograms of PPy-PI/CNT/PVDF hybrid composite electrode processed at (i) 90oC and (ii) 250oC, using an Ag/AgCl reference electrode and graphite rod counter electrode for the (a) 1st and (b) 10th cycles, respectively.

Figure 10.

Transient i–t curves obtained during potentiostatic polymerization of 0.5 M pyrrole in a 0.0225M toluene sulphonic acid solution at an applied potential of 2V, onto the PI/CNT/PVDF composite working electrode processed at (i) 90oC and (ii) 250oC, respectively.

Figure 10.

Transient i–t curves obtained during potentiostatic polymerization of 0.5 M pyrrole in a 0.0225M toluene sulphonic acid solution at an applied potential of 2V, onto the PI/CNT/PVDF composite working electrode processed at (i) 90oC and (ii) 250oC, respectively.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).