Submitted:

11 July 2024

Posted:

11 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

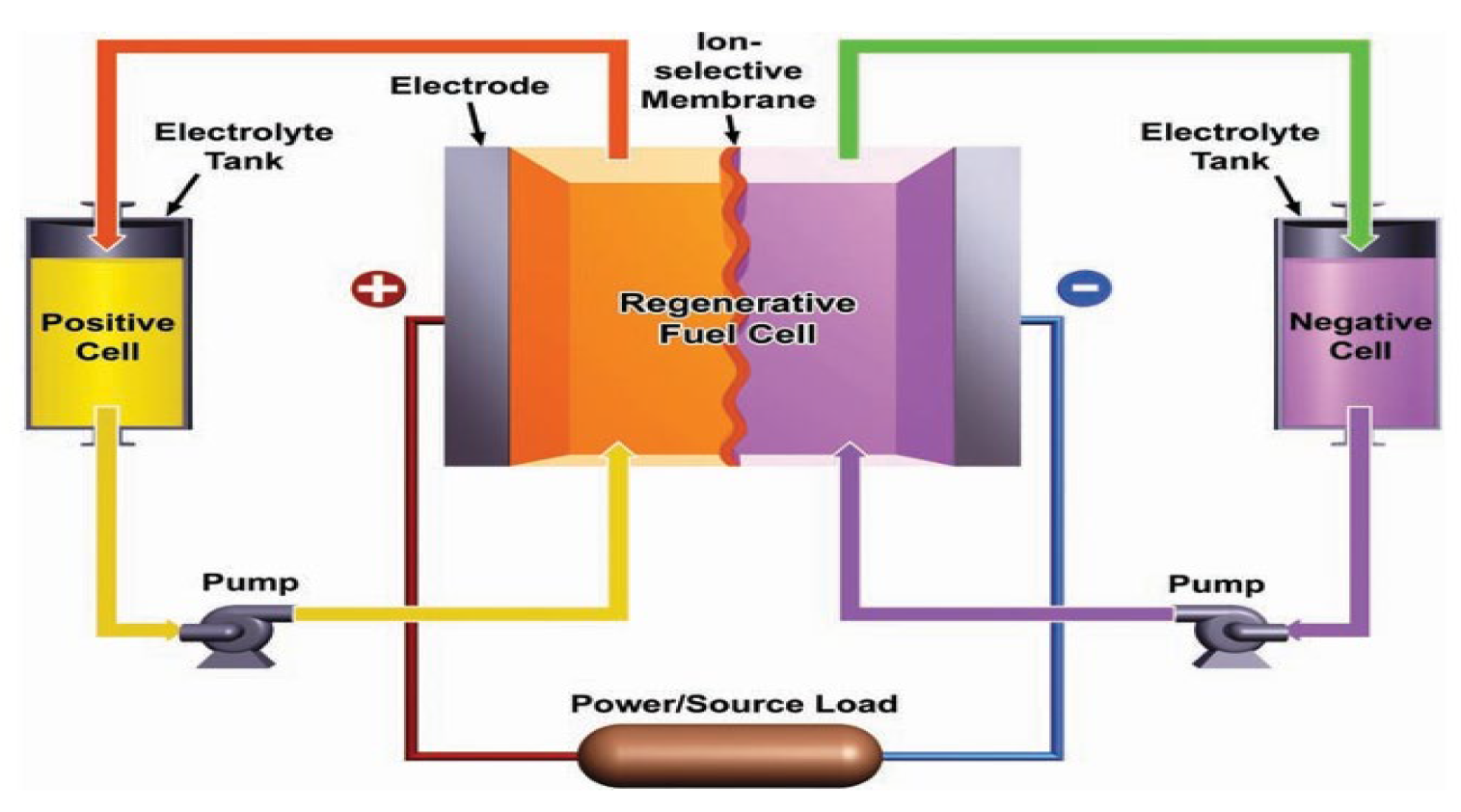

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Chemicals

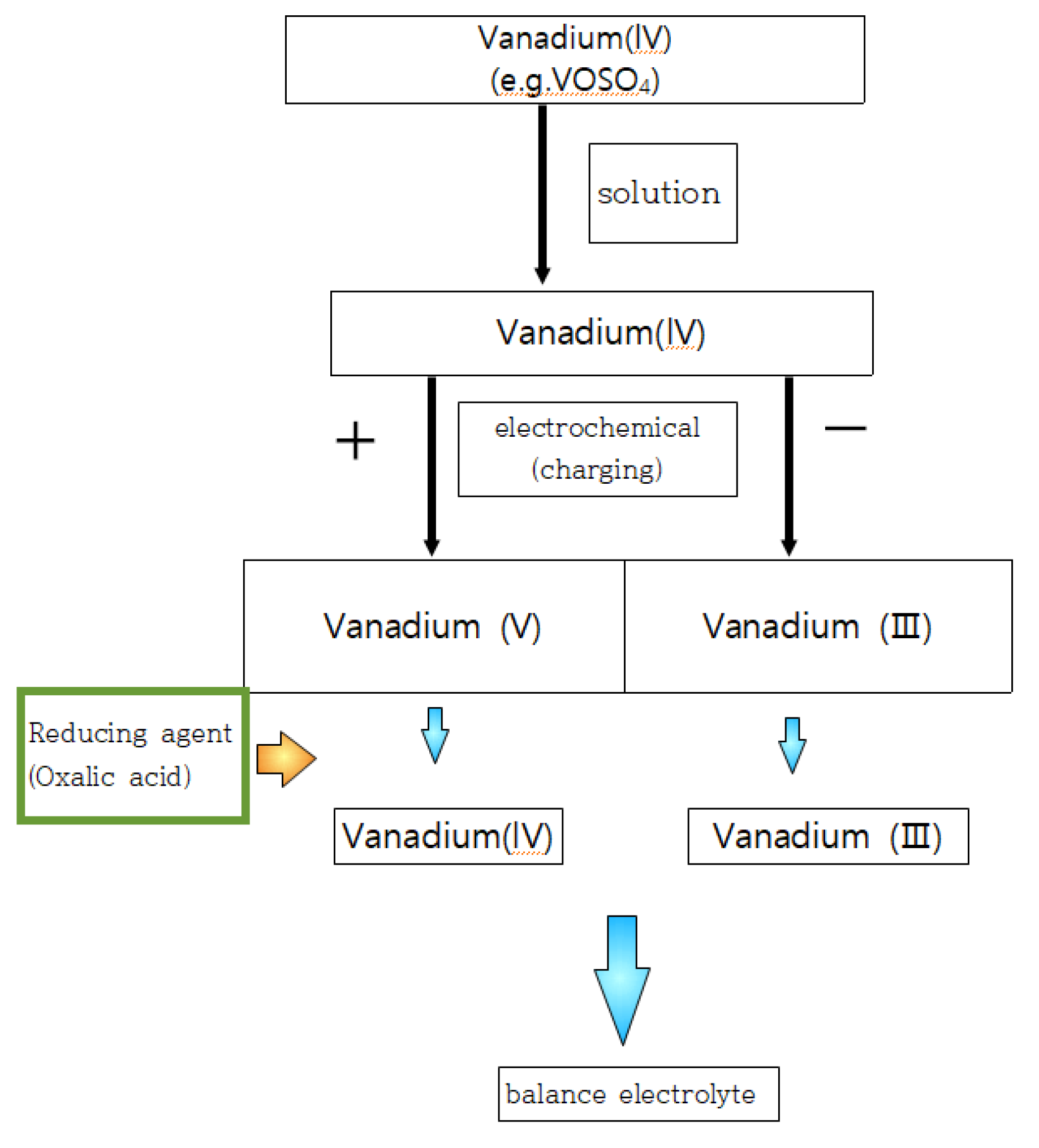

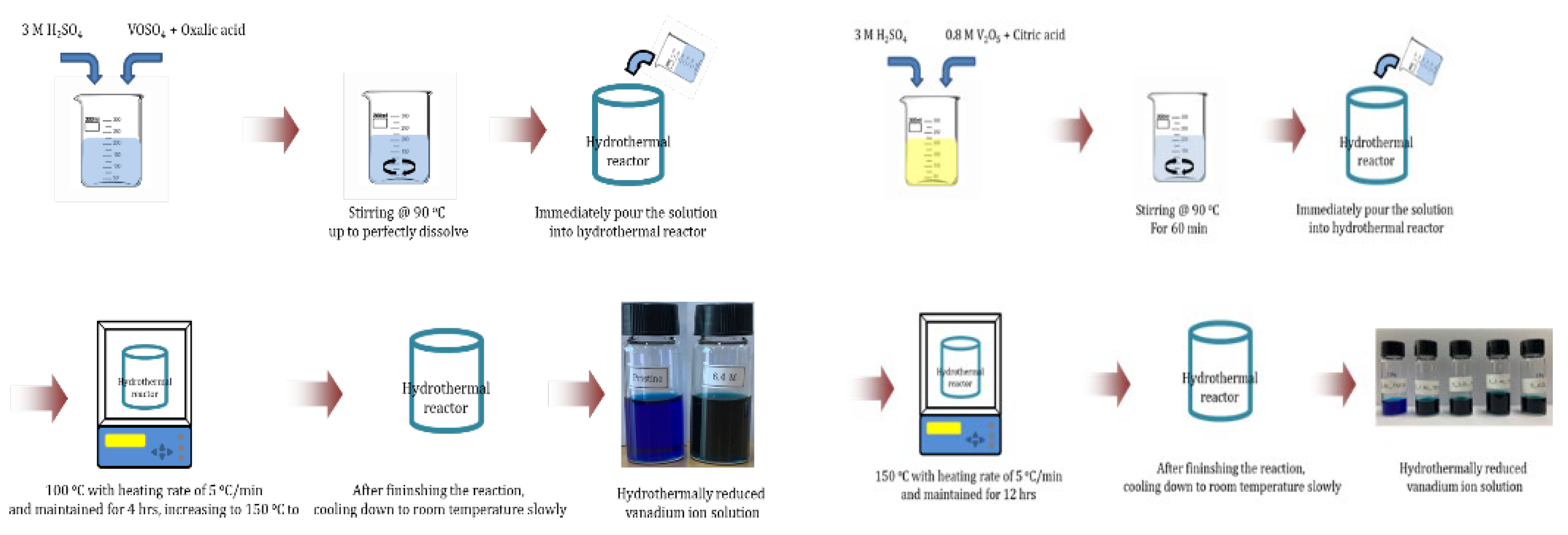

2.2. Preparation of Vavadium(3.5+)Electrolyte from Vanadium(4+)

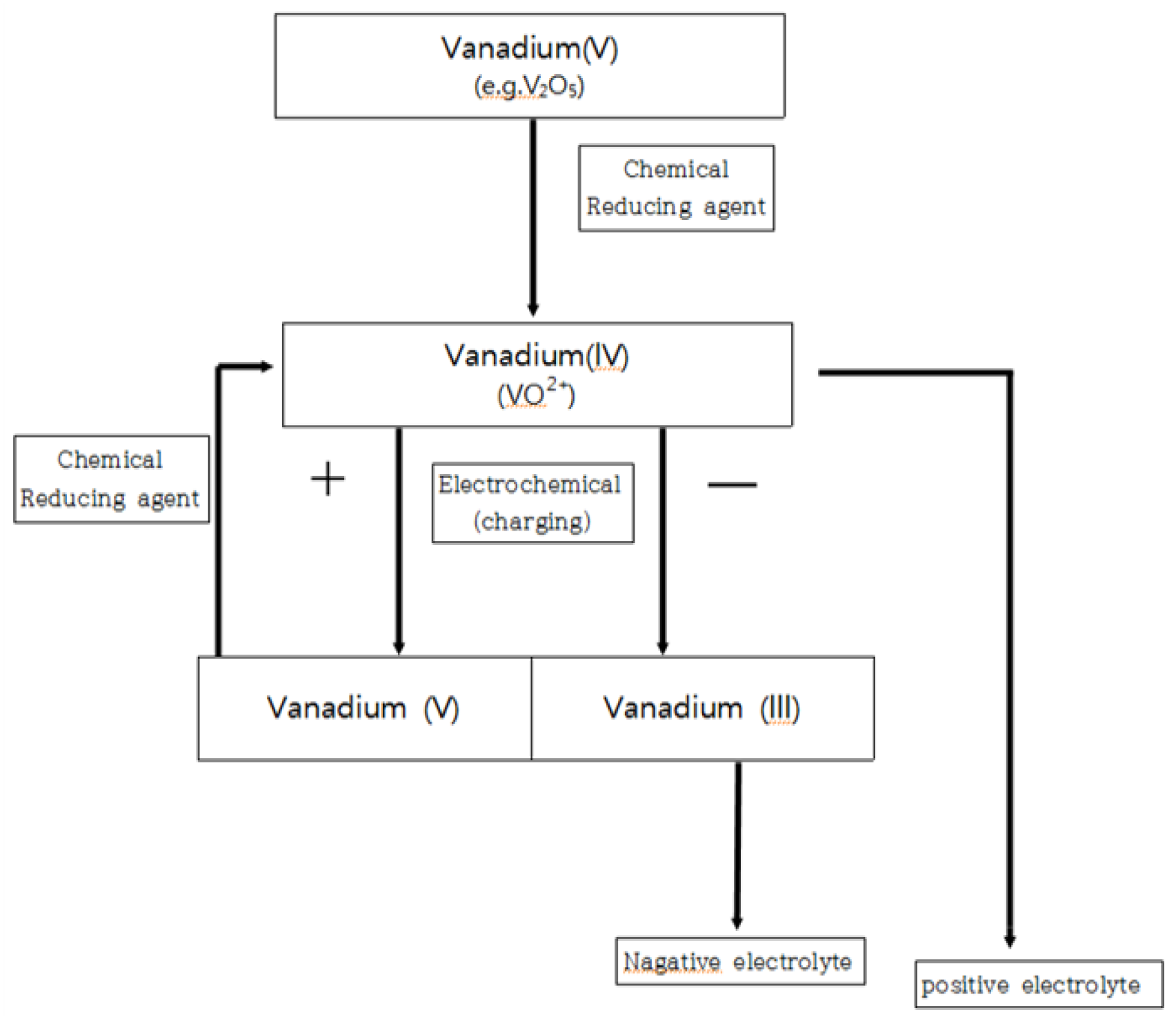

2.3. Preparation of Vanadium (3.5+) from Vanadium (5+)

2.4. Hydrothermal Reduction (HRR) of Vanadium(4+) and Vanadium (5+) Solution

2.4. Electrochemical Analysis

2.5. VRFB Cell Test

3. Result and Discussion

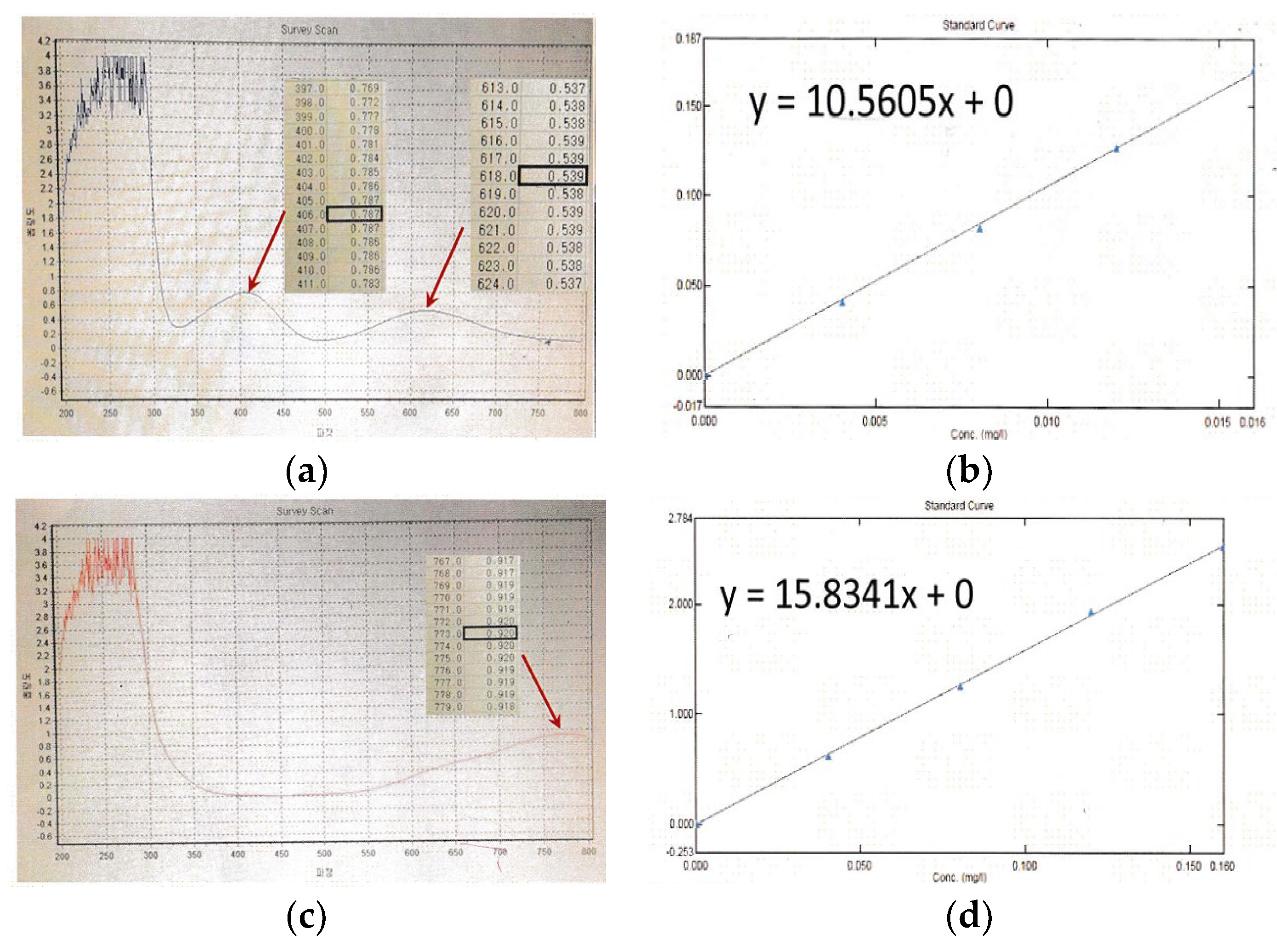

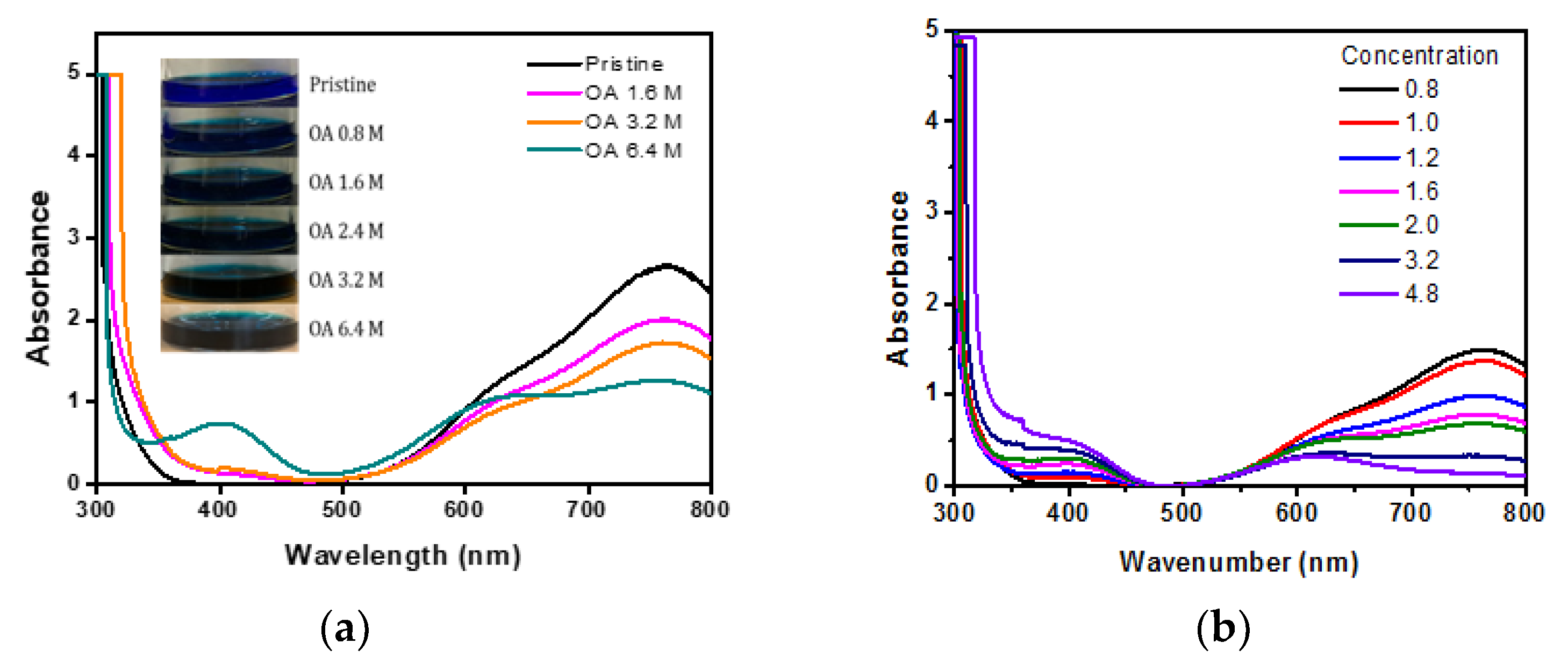

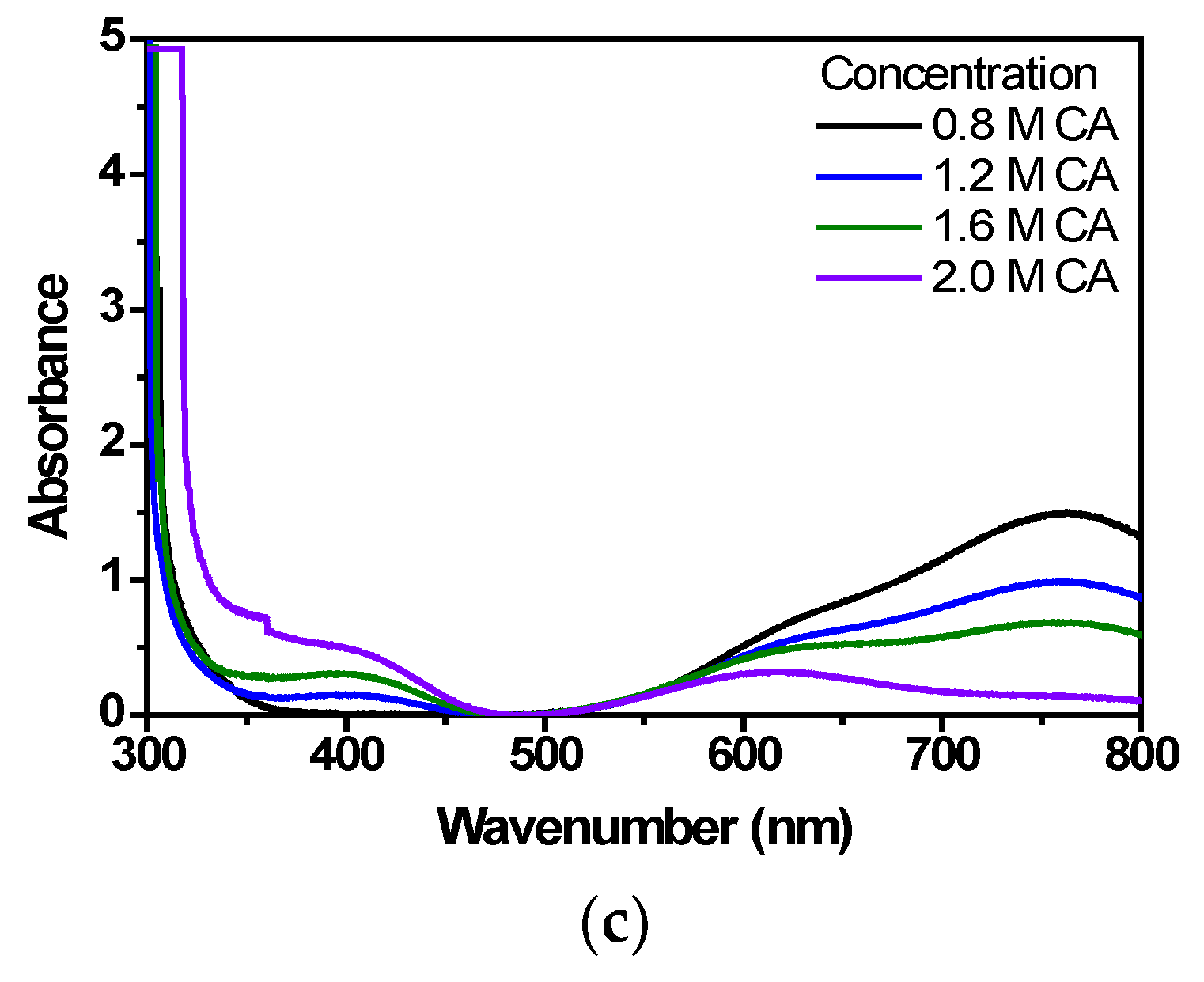

3.1. UV Characteristics and Concentration Analysis of Vanadium Electrolyte

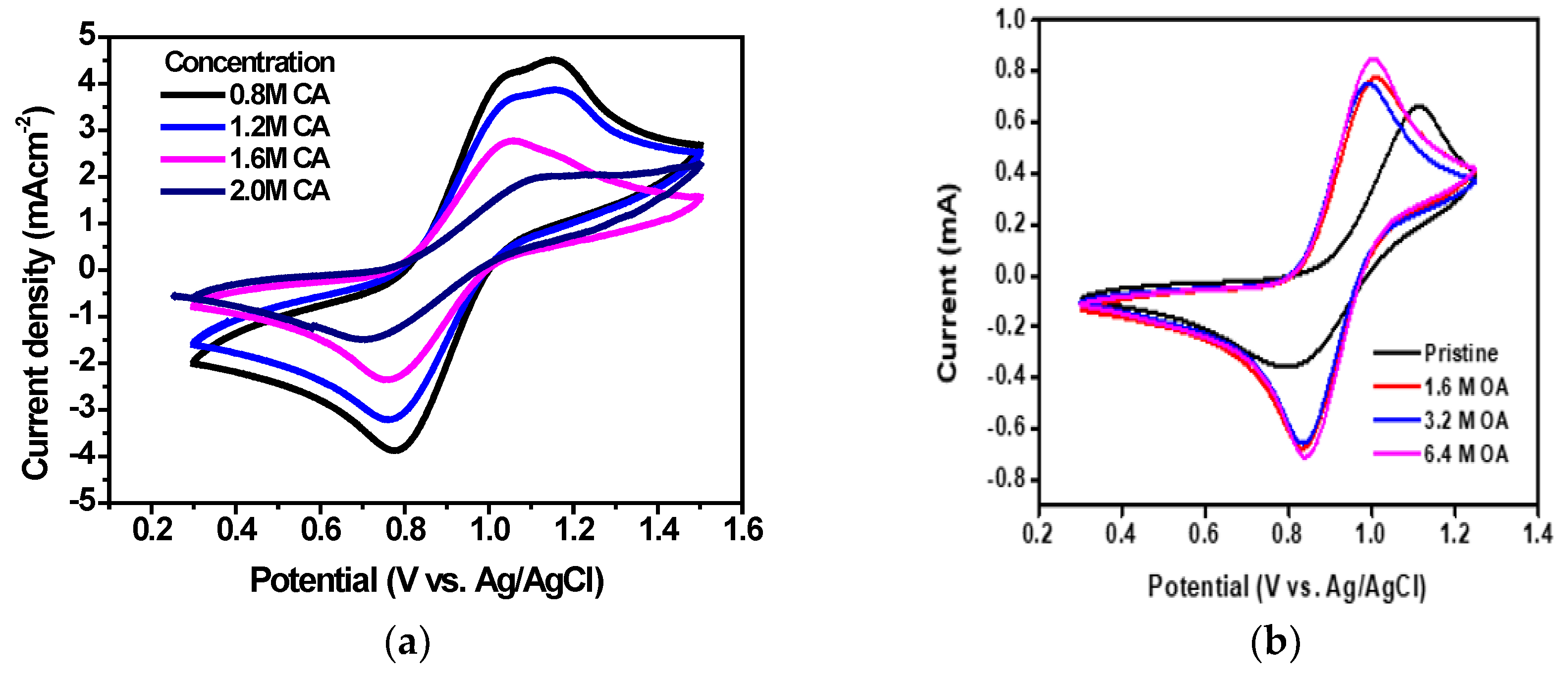

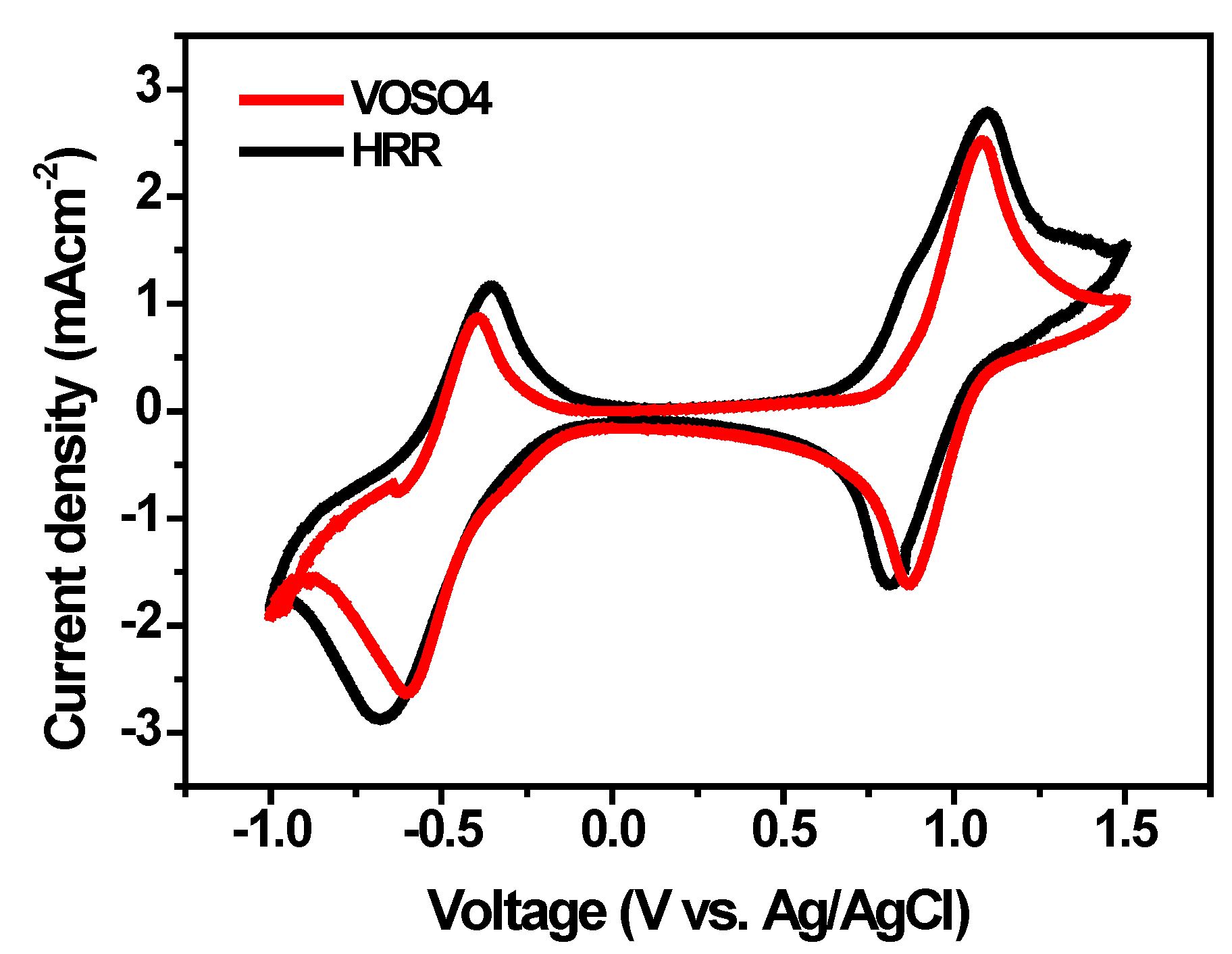

3.2. Electrochemical Properties of the Vanadium (3.5+) Electrolytes by HRR

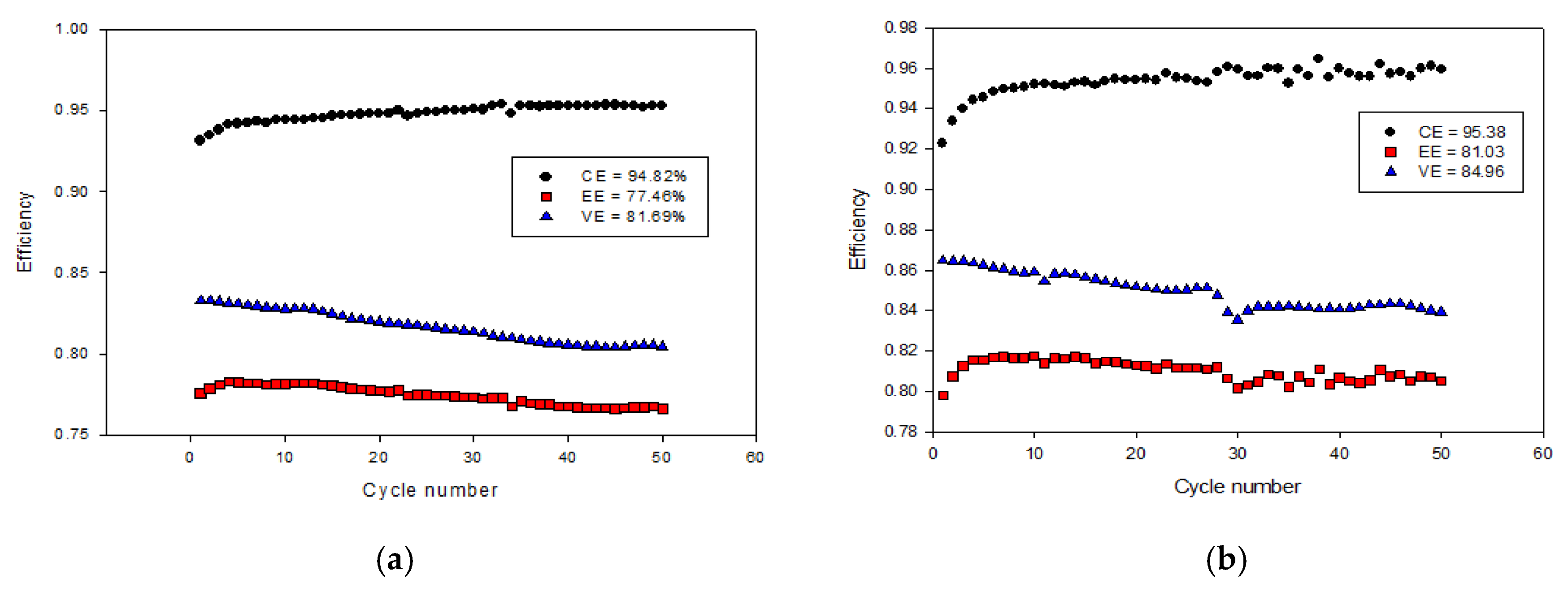

3.3. Performance of VRFB Using Vanadium (3.5+) Electrolytes by Electricity Reduction and HRR

4. Conclusion

References

- Frost & Sullivan. Emerging Technologies in the Energy Storage Market. www. Frost.com: 01/05/2016.

- IEA (International Energy Agency). Energy Storage Technology Roadmap. www.iea.org: 12/06/2024.

- Chen R.; Kim S.; Chang Z. Redox flow batteries: Fundamentals and applications. 2017; pp. 103-118. [CrossRef]

- Ye, R.; Henkensmeier, D.; Yoon, SJ.; Huang, Z. ; D K, Kim.; Chang Z. Redox flow batteries for energy storage: A technology review. JEE Conversion and Storage. 2018; 15:010801. [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.; Xu, L.; Tao, T.; Huang, L.; Li, J.; Hong, J.; Li, H.; Chi, Y. Mechanical behavior of multiscale hybrid fiber reinforced recycled aggregate concrete subject to uniaxial compression. Journal of Building Engineering 2023, 71, 106504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.; Kim, S.; Kim, R.; Choi, Y.; Kim, S.; Jung, H.-Y.; Yang, J.H.; Kim, H.-T. A review of vanadium electrolytes for vanadium redox flow batteries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 69, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Lim, T.M.; Menictas, C.; Skyllas-Kazacos, M. Review of material research and development for vanadium redox flow battery applications. Electrochimica Acta 2013, 101, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skyllas-Kazacos, M.; Kazacos, G.; Poon, G.; Verseema, H. Recent advances with UNSW vanadium-based redox flow batteries. Int. J. Energy Res. 2009, 34, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minke, C.; Kunz, U.; Turek, T. Techno-economic assessment of novel vanadium redox flow batteries with large-area cells. J. Power Sources 2017, 361, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Skyllas-Kazacos, M.; Menictas, C.; Noack, J. A review of electrolyte additives and impurities in vanadium redox flow batteries. J. Energy Chem. 2018, 27, 1269–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minke, C.; Kunz, U.; Turek, T. Techno-economic assessment of novel vanadium redox flow batteries with large-area cells. J. Power Sources 2017, 361, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kear, G.; Shah, A.A.; Walsh, F.C. Development of the all-vanadium redox flow battery for energy storage: a review of technological, financial and policy aspects. Int. J. Energy Res. 2011, 36, 1105–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skyllaskazacos, M.; Chakrabarti, M.H.; Hajimolana, S.A.; Mjalli, F.S.; Saleem, M. Progress in Flow Battery Research and Development. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2011, 158, R55–R79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J.; Wu, Z.; Teng, X.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, L.; Qiu, X. Self-assembled polyelectrolyte multilayer modified Nafion membrane with suppressed vanadium ion crossover for vanadium redox flow batteries. J. Mater. Chem. 2008, 18, 1232–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, P.; Li, X.; de León, C.P.; Berlouis, L.; Low, C.T.J.; Walsh, F.C. Progress in redox flow batteries, remaining challenges and their applications in energy storage. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 10125–10156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Kim, S.; Wang, W.; Vijayakumar, M.; Nie, Z.; Chen, B.; Zhang, J.; Xia, G.; Hu, J.; Graff, G.; et al. A Stable Vanadium Redox-Flow Battery with High Energy Density for Large-Scale Energy Storage. Adv. Energy Mater. 2011, 1, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, C.; Cao, H.; Chng, M.; Han, M.; Birgersson, E. Pulsating electrolyte flow in a full vanadium redox battery. J. Power Sources 2015, 294, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, C.; Cao, H.; Chng, M.; Han, M.; Birgersson, E. Pulsating electrolyte flow in a full vanadium redox battery. J. Power Sources 2015, 294, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sum, E.; Rychcik, M.; Skyllas-Kazacos, M. Investigation of the V(V)/V(IV) system for use in the positive half-cell of a redox battery. J. Power Sources 1985, 16, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Jonshagen, B. Zincbromine battery for energy storage. J. Power Sources 1991, 35, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, M.; Li, L.; Graff, G.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Z.; Hu, J.Z. Towards understanding the poor thermal stability of V5+ electrolyte solution in Vanadium Redox Flow Batteries. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 3669–3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, F.; Skyllas-Kazacos, M. Solubility of vanadyl sulfate in concentrated sulfuric acid solutions. J. Power Sources 1998, 72, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.; Han, J.-Y.; Kim, S.; Yuk, S.; Choi, C.; Kim, R.; Lee, J.-H.; Klassen, A.; Ryi, S.-K.; Kim, H.-T. Catalytic production of impurity-free V3.5+ electrolyte for vanadium redox flow batteries. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skyllas-Kazacos, M. , Kazacos, M. & McDermott, R. Vanadium compound dissolution processes. Patent Application PCT/AU1988/000471 (1988).

- Li, W.; Zaffou, R.; Sholvin, C.C.; Perry, M.L.; She, Y. Vanadium Redox-Flow-Battery Electrolyte Preparation with Reducing Agents. ECS Trans. 2013, 53, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz, M. & Zu, G. Production of vanadium electrolyte for a vanadium flow cell. Patent Application US 14/526,435 (2015).

| Electrolyte |

Ipa Ipc Ipa/Ipc ΔE(V) |

Ipa Ipc Ipa/Ipc ΔE(V) |

|---|---|---|

| 1.6MVOSO4 +3MH2SO4 0.8MV2O5 +3MH2SO4by HRR |

2.28 1.10 2.07 0.36 2.00 0.85 2.35 0.20 |

1.62 2.81 0.57 0.39 1.60 1.90 0.84 0.45 |

| Electrolyte | CE | VE | EE |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.6M VOSO4 + 3M H2SO4 0.8M V2O5 + 3M H2SO4 by HRR |

94.82 | 81.69 | 77.48 |

| 95.38 | 84.96 | 81.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).