Submitted:

09 July 2024

Posted:

11 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. CoQ10 Ubiquinol

3. Potential Mechanisms

4. Materials and Methods

5. Results

5.1. Females

5.2. Males

6. Discussion and Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. World Health Organisation. Infertility Prevalence Estimates, 1990–2021. Available online: (accessed on.

- Silva, A.B.P.; Carreiro, F.; Ramos, F.; Sanches-Silva, A. The role of endocrine disruptors in female infertility. Mol Biol Rep 2023, 50, 7069–7088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaliere, G. Involuntary Childlessness, Suffering, and Equality of Resources: An Argument for Expanding State-funded Fertility Treatment Provision. J Med Philos 2023, 48, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnoth, C.; Godehardt, E.; Frank-Herrmann, P.; Friol, K.; Tigges, J.; Freundl, G. Definition and prevalence of subfertility and infertility. Hum Reprod 2005, 20, 1144–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vander Borght, M.; Wyns, C. Fertility and infertility: Definition and epidemiology. Clin Biochem 2018, 62, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sang, Q.; Ray, P.F.; Wang, L. Understanding the genetics of human infertility. Science 2023, 380, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kicinska, A.M.; Maksym, R.B.; Zabielska-Kaczorowska, M.A.; Stachowska, A.; Babinska, A. Immunological and Metabolic Causes of Infertility in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornos Carneiro, M.F.; Colaiacovo, M.P. Beneficial antioxidant effects of Coenzyme Q10 on reproduction. Vitam Horm 2023, 121, 143–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, M.L.; Esteves, S.C.; Lamb, D.J.; Hotaling, J.M.; Giwercman, A.; Hwang, K.; Cheng, Y.S. Male infertility. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2023, 9, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belenkaia, L.V.; Lazareva, L.M.; Walker, W.; Lizneva, D.V.; Suturina, L.V. Criteria, phenotypes and prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome. Minerva Ginecol 2019, 71, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaffarino, F.; Cipriani, S.; Dalmartello, M.; Ricci, E.; Esposito, G.; Fedele, F.; La Vecchia, C.; Negri, E.; Parazzini, F. Prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in European countries and USA: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2022, 279, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njagi, P.; Groot, W.; Arsenijevic, J.; Dyer, S.; Mburu, G.; Kiarie, J. Financial costs of assisted reproductive technology for patients in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Hum Reprod Open 2023, 2023, hoad007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdogan, K.; Sanlier, N.T.; Sanlier, N. Are epigenetic mechanisms and nutrition effective in male and female infertility? J Nutr Sci 2023, 12, e103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirilli, I.; Damiani, E.; Dludla, P.V.; Hargreaves, I.; Marcheggiani, F.; Millichap, L.E.; Orlando, P.; Silvestri, S.; Tiano, L. Role of Coenzyme Q(10) in Health and Disease: An Update on the Last 10 Years (2010-2020). Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelton, R. Coenzyme Q(10): A Miracle Nutrient Advances in Understanding. Integr Med (Encinitas) 2020, 19, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Acosta, M.J.; Vazquez Fonseca, L.; Desbats, M.A.; Cerqua, C.; Zordan, R.; Trevisson, E.; Salviati, L. Coenzyme Q biosynthesis in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 2016, 1857, 1079–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arenas-Jal, M.; Sune-Negre, J.M.; Garcia-Montoya, E. Coenzyme Q10 supplementation: Efficacy, safety, and formulation challenges. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2020, 19, 574–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carneiro, M.; Colaiacovo, M. Chapter Six - Beneficial antioxidant effects of Coenzyme Q10 on reproduction. Vitamins and Hormones 2023, 121, 143–167. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, C.; Bysted, A.; Holmer, G. Coenzyme Q10 in the diet--daily intake and relative bioavailability. Mol Aspects Med 1997, 18 Suppl, S251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, R. Coenzyme Q10: The essential nutrient. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2011, 3, 466–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcazar-Fabra, M.; Navas, P.; Brea-Calvo, G. Coenzyme Q biosynthesis and its role in the respiratory chain structure. Biochim Biophys Acta 2016, 1857, 1073–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derbyshire, E. Micronutrient Intakes of British Adults Across Mid-Life: A Secondary Analysis of the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey. Front Nutr 2018, 5, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitsopoulou, A.V.; Magriplis, E.; Michas, G.; Micha, R.; Chourdakis, M.; Chrousos, G.P.; Roma, E.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Zampelas, A.; Karageorgou, D.; et al. Micronutrient dietary intakes and their food sources in adults: The Hellenic National Nutrition and Health Survey (HNNHS). J Hum Nutr Diet 2021, 34, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhu, X.; Fulda, K.G.; Chen, S.; Tao, M.H. Comparison of Dietary Micronutrient Intakes by Body Weight Status among Mexican-American and Non-Hispanic Black Women Aged 19-39 Years: An Analysis of NHANES 2003-2014. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

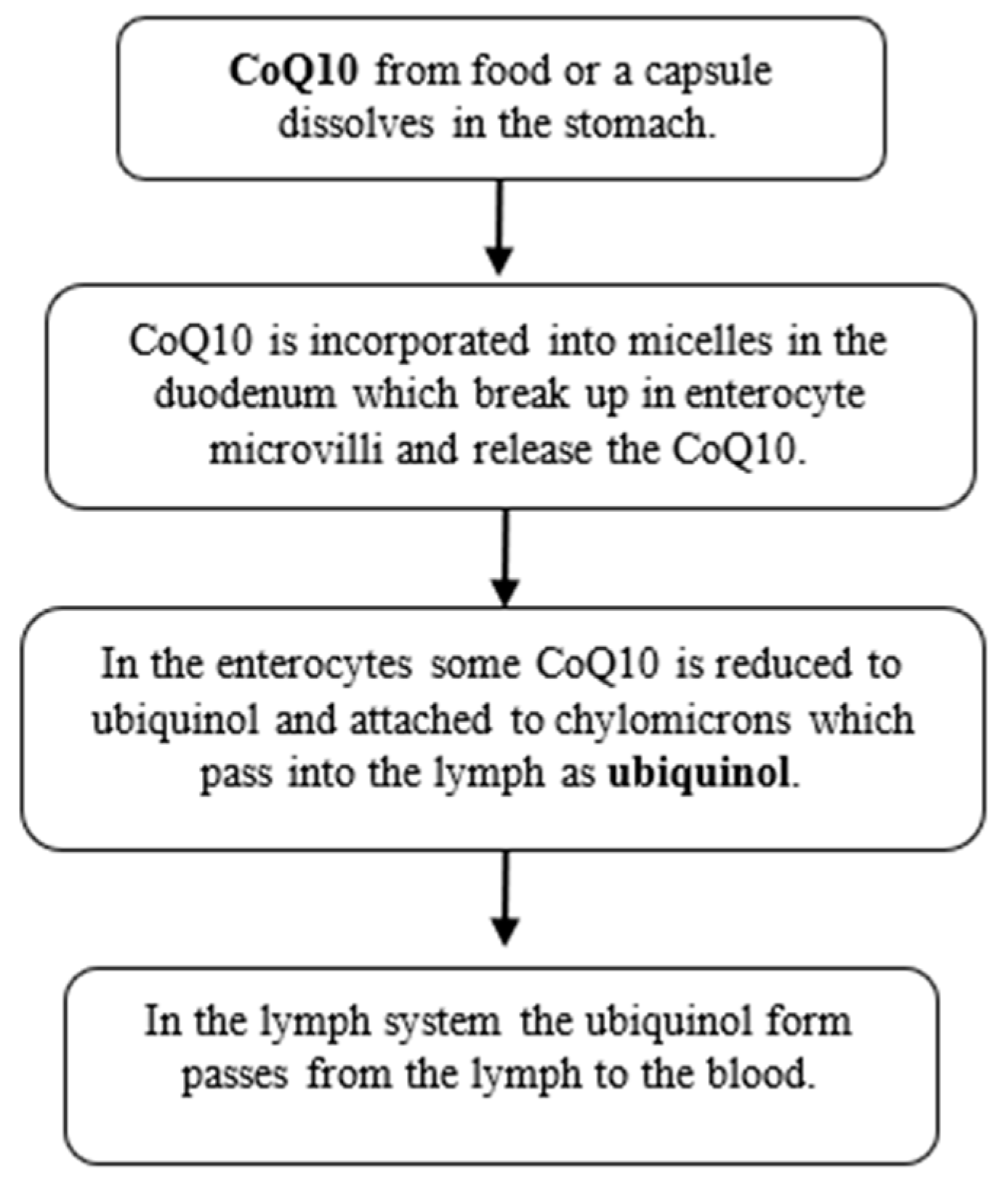

- Mantle, D.; Dybring, A. Bioavailability of Coenzyme Q(10): An Overview of the Absorption Process and Subsequent Metabolism. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagavan, H.N.; Chopra, R.K.; Craft, N.E.; Chitchumroonchokchai, C.; Failla, M.L. Assessment of coenzyme Q10 absorption using an in vitro digestion-Caco-2 cell model. Int J Pharm 2007, 333, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langsjoen, P.H.; Langsjoen, A.M. Comparison study of plasma coenzyme Q10 levels in healthy subjects supplemented with ubiquinol versus ubiquinone. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev 2014, 3, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.Q.; Oliver Chen, C.Y. Ubiquinol is superior to ubiquinone to enhance Coenzyme Q10 status in older men. Food Funct 2018, 9, 5653–5659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosoe, K.; Kitano, M.; Kishida, H.; Kubo, H.; Fujii, K.; Kitahara, M. Study on safety and bioavailability of ubiquinol (Kaneka QH) after single and 4-week multiple oral administration to healthy volunteers. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2007, 47, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikematsu, H.; Nakamura, K.; Harashima, S.; Fujii, K.; Fukutomi, N. Safety assessment of coenzyme Q10 (Kaneka Q10) in healthy subjects: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2006, 44, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babayev, E.; Seli, E. Oocyte mitochondrial function and reproduction. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2015, 27, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzorno, J. Mitochondria-Fundamental to Life and Health. Integr Med (Encinitas) 2014, 13, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Labarta, E.; de Los Santos, M.J.; Escriba, M.J.; Pellicer, A.; Herraiz, S. Mitochondria as a tool for oocyte rejuvenation. Fertil Steril 2019, 111, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Meir, A.; Burstein, E.; Borrego-Alvarez, A.; Chong, J.; Wong, E.; Yavorska, T.; Naranian, T.; Chi, M.; Wang, Y.; Bentov, Y.; et al. Coenzyme Q10 restores oocyte mitochondrial function and fertility during reproductive aging. Aging Cell 2015, 14, 887–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skoracka, K.; Eder, P.; Lykowska-Szuber, L.; Dobrowolska, A.; Krela-Kazmierczak, I. Diet and Nutritional Factors in Male (In)fertility-Underestimated Factors. J Clin Med 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirata, S.; Hoshi, K.; Shoda, T.; Mabuchi, T. Spermatozoon and mitochondrial DNA. Reprod Med Biol 2002, 1, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmar, A.T.; Calogero, A.E.; Singh, R.; Cannarella, R.; Sengupta, P.; Dutta, S. Coenzyme Q10, oxidative stress, and male infertility: A review. Clin Exp Reprod Med 2021, 48, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Huetos, A.; Rosique-Esteban, N.; Becerra-Tomas, N.; Vizmanos, B.; Bullo, M.; Salas-Salvado, J. The Effect of Nutrients and Dietary Supplements on Sperm Quality Parameters: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Adv Nutr 2018, 9, 833–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariton, E.; Locascio, J.J. Randomised controlled trials - the gold standard for effectiveness research: Study design: Randomised controlled trials. BJOG 2018, 125, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, H.; Waheed, K.; Mazhar, R.; Sarwar, M.Z. Comparative Study Of Combined Co-Enzyme Q10 And Clomiphene Citrate Vs Clomiphene Citrate Alone For Ovulation Induction In Patients With Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. J Pak Med Assoc 2023, 73, 1502–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamali, M.; Gholizadeh, M. The effects of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on metabolic profiles and parameters of mental health in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol 2022, 38, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadi, A.; Ebrahimi, S.; Shirazi, S.; Taghizadeh, S.; Parizad, M.; Farzadi, L.; Gargari, B.P. Hormonal and Metabolic Effects of Coenzyme Q10 and/or Vitamin E in Patients With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019, 104, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Nisenblat, V.; Lu, C.; Li, R.; Qiao, J.; Zhen, X.; Wang, S. Pretreatment with coenzyme Q10 improves ovarian response and embryo quality in low-prognosis young women with decreased ovarian reserve: A randomized controlled trial. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2018, 16, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammar, I.; Abdou, A. Effect of Ubiquinol supplementation on ovulation induction in Clomiphene Citrate resistance. Middle East Fertility Society Journal 2021, 26, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, A.; Ayas, B.; Guven, D.; Bakay, A.; Karlh, P. Antioxidant Supplement Improves the Pregnancy Rate in Patients Undergoing in Vitro Fertilization for Unexplained Infertility. Open Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2019, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen Sharma, D. Co-enzyme Q10-A mitochondrial antioxidant – a new hope for success in infertility in clomiphene-citrate-resistant polycystic ovary syndrome. Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Oral Commun. [CrossRef]

- Caballero, T.; Fiameni, F.; Valcarcel, A.; Buzzi, J. Dietary supplementation with coenzyme Q10 in poor responder patients undergoing IVF-ICSI Treatment. Fertility and Sterility 2016, 106, E58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmar, A.T.; Naemi, R. Predictors of pregnancy and time to pregnancy in infertile men with idiopathic oligoasthenospermia pre- and post-coenzyme Q10 therapy. Andrologia 2022, 54, e14385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alahmar, A.T.; Sengupta, P. Impact of Coenzyme Q10 and Selenium on Seminal Fluid Parameters and Antioxidant Status in Men with Idiopathic Infertility. Biol Trace Elem Res 2021, 199, 1246–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadjarzadeh, A.; Shidfar, F.; Amirjannati, N.; Vafa, M.R.; Motevalian, S.A.; Gohari, M.R.; Nazeri Kakhki, S.A.; Akhondi, M.M.; Sadeghi, M.R. Effect of Coenzyme Q10 supplementation on antioxidant enzymes activity and oxidative stress of seminal plasma: A double-blind randomised clinical trial. Andrologia 2014, 46, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarinejad, M.R.; Safarinejad, S.; Shafiei, N.; Safarinejad, S. Effects of the reduced form of coenzyme Q10 (ubiquinol) on semen parameters in men with idiopathic infertility: A double-blind, placebo controlled, randomized study. J Urol 2012, 188, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadjarzadeh, A.; Sadeghi, M.R.; Amirjannati, N.; Vafa, M.R.; Motevalian, S.A.; Gohari, M.R.; Akhondi, M.A.; Yavari, P.; Shidfar, F. Coenzyme Q10 improves seminal oxidative defense but does not affect on semen parameters in idiopathic oligoasthenoteratozoospermia: A randomized double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Endocrinol Invest 2011, 34, e224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balercia, G.; Buldreghini, E.; Vignini, A.; Tiano, L.; Paggi, F.; Amoroso, S.; Ricciardo-Lamonica, G.; Boscaro, M.; Lenzi, A.; Littarru, G. Coenzyme Q10 treatment in infertile men with idiopathic asthenozoospermia: A placebo-controlled, double-blind randomized trial. Fertil Steril 2009, 91, 1785–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safarinejad, M.R. Efficacy of coenzyme Q10 on semen parameters, sperm function and reproductive hormones in infertile men. J Urol 2009, 182, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skakkebaek, N.E.; Lindahl-Jacobsen, R.; Levine, H.; Andersson, A.M.; Jorgensen, N.; Main, K.M.; Lidegaard, O.; Priskorn, L.; Holmboe, S.A.; Brauner, E.V.; et al. Environmental factors in declining human fertility. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2022, 18, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.C.; Li, C.J.; Lin, L.T.; Wen, Z.H.; Cheng, J.T.; Tsui, K.H. Examining the Effects of Nutrient Supplementation on Metabolic Pathways via Mitochondrial Ferredoxin in Aging Ovaries. Nutrients 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, P.H.; Su, W.P.; Li, C.J.; Lin, L.T.; Sheu, J.J.; Wen, Z.H.; Cheng, J.T.; Tsui, K.H. Investigating the Role of Ferroptosis-Related Genes in Ovarian Aging and the Potential for Nutritional Intervention. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, A.S.; Littaru, G.P.; Funahashi, I.; Painkara, U.S.; Dange, N.S.; Chauhan, P. Effect of Ubiquinol on Serum Reproductive Hormones of Amenorrhic Patients. Indian J Clin Biochem 2016, 31, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiseo, B.C.; Gaskins, A.J.; Hauser, R.; Chavarro, J.E.; Tanrikut, C.; Team, E.S. Coenzyme Q10 Intake From Food and Semen Parameters in a Subfertile Population. Urology 2017, 102, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Hosoe, K.; Funahashi, I. Lower plasma coenzyme Q10 concentrations in healthy vegetarians and vegans compared with omnivores. Nutrafoods 2022, 1, 379–386. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, I.; Heaton, R.A.; Mantle, D. Disorders of Human Coenzyme Q10 Metabolism: An Overview. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantle, D.; Millichap, L.; Castro-Marrero, J.; Hargreaves, I.P. Primary Coenzyme Q10 Deficiency: An Update. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. European Food Safety Authority. Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to coenzyme Q10 and contribution to normal energy-yielding metabolism (ID 1508, 1512, 1720, 1912, 4668), maintenance of normal blood pressure (ID 1509, 1721, 1911), protection of DNA, proteins and lipids from oxidative damage (ID 1510), contribution to normal cognitive function (ID 1511), maintenance of normal blood cholesterol concentrations (ID 1721) and increase in endurance capacity and/or endurance performance (ID 1913) pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/20061. EFSA Journal 2010, 8, 1793. [Google Scholar]

- Kaikkonen, J.; Tuomainen, T.P.; Nyyssonen, K.; Salonen, J.T. Coenzyme Q10: Absorption, antioxidative properties, determinants, and plasma levels. Free Radic Res 2002, 36, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villalba, J.M.; Parrado, C.; Santos-Gonzalez, M.; Alcain, F.J. Therapeutic use of coenzyme Q10 and coenzyme Q10-related compounds and formulations. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2010, 19, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, A.F.; Soares, M.; Almeida-Santos, T.; Ramalho-Santos, J.; Sousa, A.P. Aging and oocyte competence: A molecular cell perspective. WIREs Mech Dis 2023, 15, e1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author | Sample population | Type and duration of study | Outcome of focus | Supplement dosage | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | |||||

| [40] | n=136 females with PCOS | 45-day randomized controlled trial | Ovulation induction | 50mg CoQ10 in soft gel capsules thrice per day | In the CoQ10 plus Clomiphene citrate group ovulation induction was observed in 23.5% patients, indicating that with the addition of CoQ10 improved the chances of ovulation induction. |

| [41] | n=55 PCOS women (aged 18-40 yrs) | 12-week double-blinded, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial | Hormonal indices, oxidative stress | 100mg/day of CoQ10 | The CoQ10 group had a significant drop in total testosterone (p = .004), DHEAS (p < .001), hirsutism (p = .002) and MDA (p = .001) levels & a significant rise in SHBG (p < .001) & TAC (p < .001) levels in serum than the placebo group. |

| [44] | n=148 PCOS patients with Clomiphene Citrate resistance (75 treated with ubiquinol and Clomiphene Citrate, and 73 with human menopausal gonadotropins) | Randomized controlled trial | Ovarian responsiveness | 100mg/d of CoQ10 as ubiquinol added to Clomiphene Citrate | No statistically significant differences (P > 0.05) between studied groups regarding ovarian responsiveness. |

| [42] | n=86 females with PCOS | 8-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Hormonal markers | 200mg/d CoQ10 | CoQ10 with or without vitamin E supplementation among women with PCOS had beneficial effects on total testosterone levels (p<0.001). |

| [45] | n=299 females undergoing IVF-ICSI (135 treated with OMEPA Q10 and 164 controls) | 2-months #break#retrospective case-controlled study | Pregnancy rate,#break#total amount of gonadotropins dose | 100mg/day of CoQ10 as ubiquinol together with omega-3 | Ubiquinol with omega-3 supplementation increased pregnancy rate (p<0.002) and reduced the total gonadotropin dose (p<0.001).#break# |

| [43] | n=169 females with POR (76 treated with CoQ10 and 93 controls) preceding IVF | 60-day randomized controlled trial | Ovarian response, embryo quality | 200mg CoQ10 thrice per day | The CoQ10 group had increased number of retrieved oocytes, higher fertilization rate (67.49%) and more high-quality embryos; p < 0.05. |

| [46] | n=62 infertile females with PCOS | Randomized controlled trial during cycle. | Size of matured follicle, endometrial thickness, clinical pregnancy, miscarriage rate | 60mg CoQ10 thrice per day | Follicle size, endometrial thickness and clinical pregnancy rate were improved in the group receiving CoQ10 and miscarriage rate was lower compared with the control group. |

| [47] | n=78 poor responders in a prior IVF cycle. | 12-week prospective randomized controlled study. | Oocytes retrieved, implantation rate, clinical pregnancy rate | 600 mg Co Q10 twice per day | No significant differences were detected between the CoQ10 and control group. |

| Author | Sample population | Type and duration of study | Outcome of focus | Supplement dosage | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | |||||

| [48] | n=178 male patients with idiopathic OAT and 84 fertile men (controls) | 6-month prospective controlled clinical study | Time to pregnancy | 200mg/d CoQ10 as ubiquinol | CoQ10 significantly improved semen parameters, antioxidant measures and reduced sperm DNA fragmentation. |

| [49] | n=70 men with idiopathic OAT | 3-month randomized controlled trial | Semen parameters | 200mg/d ubiquinol or selenium | Sperm concentration, progressive and total motility significantly increased with CoQ10 treatment (p<0.01) with this being most effective. |

| [50] | n=60 infertile men with idiopathic OAT | 3-month randomized placebo-controlled trial | Oxidative stress and antioxidant enzymes in seminal plasma | 200mg/d CoQ10 | CoQ10 levels significantly increased from 44.74 ± 36.47 to 68.17 ± 42.41 ng ml(-1) following supplementation (p < 0.001). CoQ10 group had higher catalase and SOD activity than the placebo. CoQ10 concentration and normal sperm morphology (p= 0.037), catalase (p= 0.041) and SOD (p < 0.001) were significantly & positively correlated. |

| [51] | n=228 men with unexplained infertility | 26-week double-blind, placebo controlled, randomized trial | Semen parameters | 200mg/d CoQ10 as ubiquinol | Correlation coefficients identified a positive association between ubiquinol treatment & sperm density (r = 0.74, p = 0.017), sperm motility (r = 0.66, p = 0.024) and sperm morphology (r = 0.57, p = 0.027). |

| [52] | n=47 infertile men with idiopathic OAT | 12-week double-blind placebo controlled clinical trial | Semen parameters | 200mg CoQ10 daily | There were non-significant changes in semen parameters in CoQ10 group, but total antioxidant capacity of seminal fluid increased significantly (p<0.05) |

| [53] | n=60 infertile patients (27-39 years of age) with specific baseline sperm selection criteria (idiopathic asthenozoospermia) | 6-month double-blind, placebo controlled, randomized trial | Semen parameters | 200mg/d CoQ10 | CoQ10 and ubiquinol increased significantly in sperm cells and seminal plasma, with males with reduced sperm motility at baseline responding and sperm kinetic features improving. |

| [54] | n=212 infertile men with idiopathic OAT | 26-week randomised controlled trial | Semen parameters, sperm function and reproductive hormones | 300mg/d CoQ10 | Sperm density and motility significantly improved with CoQ10 (p=0.01). Sperm morphology and count also improved. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).