1. Introduction

To treat hematologic malignancies chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells are increasingly used due to their safety and high efficacy [

1,

2,

3]. Clinically approved CAR therapies are directed against B cell malignancies such as multiple myeloma (MM), acute lymphocytic leukemia, and lymphomas, resistant to conventional treatments [

4,

5,

6,

7]. These second-generation CARs consist of an antibody-derived extracellular ligand-binding domain, linked to a spacer- and transmembrane domain (CD8a, CD28, or IgG) and two cytoplasmic domains providing co-stimulatory and activating signals to the T-cell (4-1BB/CD3ζ or CD28/CD3ζ, respectively) [

8]. The ligand-binding domains are most engineered as single chain variable fragments (scFv) able to bind to a tumor antigen. The CAR redirects the T- cell to identify and kill the antigen-carrying tumor cell. In our cancer center we applied all CAR T-cell therapies currently approved for clinical use in Europe: tisagenlecleucel (Tisa-cel; Kymriah

®), axicabtagene ciloleucel (Axi-cel; Yescarta

®), brexucabtagene autoleucel (Brexu-cel; Tecartus

®), and lisocabtagene maraleucel (Liso-cel; Breyanzi

®), idecabtagene vicleucel (Ide-cel; Abecma

®), ciltacabtagene autoleucel (Cilta-cel; Carvykti

®) [

9,

10]. These CAR T-cell products used to treat B-cell leukemias and lymphomas (Tisa-cel, Axi-cel, Brexu-cel, and Liso-cel) or MM (Ide-cel, and Cilta-cel) bind to the extracellular domain of CD19 antigen or the B cell maturation antigen (BCMA), respectively.

The manufacturing process of autologous CAR T-cell products includes lymphocyte apheresis, lentiviral transfection of the CAR into the T-cells, followed by cell expansion and subsequent infusion into the patient [

11]. To monitor the course of CAR T-cell treatment numbers and frequencies of CAR T-cells in individual patient’s play a pivotal role as diagnostic parameter [

1,

12,

13]. Therefore, antigen-based flow cytometric CAR T-cell detection methods are feasible for clinical routine diagnostics [

12,

14]. These assays recognize the binding of a biotin-labeled recombinant antigen to the antigen-binding site of the CAR, detected by a fluorescent labeled anti-biotin antibody [

12,

15].

Besides CAR T-cells, another therapeutic strategy that redirects the patient’s T-cell cytotoxic activity to cancer cells consists of artificial bispecific antibodies (bispecific T-cell engagers, BiTEs) and bispecific antibodies (bsAbs) [

16,

17,

18].

One arm of a BiTE/bsAb binds to a surface antigen of a tumor cell (e.g., CD19 orBCMA) whereas the other arm binds to the CD3 receptor of a T-cell initiating a T-cell receptor independent killing of cancer cells. As the combination of BiTE/bsAb and CAR T-cells has been demonstrated to improve the effectiveness of CAR T-cell therapy, either as bridging or as combined therapeutic approaches, both are now increasingly used in practice or in clinical trials [

19], respectively.

Previously, we have demonstrated that teclistamab, a BCMAxCD3 bsAb [

20], interfere with flow cytometry based BCMA CAR T-cell detection in the blood of MM patients, thus leading to false positive results [

12]. Teclistamab binds to all T-cells via CD3, irrespective of the presence of a CAR, while the other arm (even in the absence of a CAR) binds the soluble biotinylated BCMA used for CAR detection. More general, CAR monitoring during the presence of BiTEs/bsAbs is not possible for CARs/BiTEs/bsAbs combinations recognizing the same antigen (e.g., anti-CD19 CARs/CD19xCD3 BiTEs), if antigen-based CAR detection methods are applied [

12].

To circumvent this critical diagnostic problem, we here evaluate a new detection strategy by using anti-CAR linker monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) [

13,

21,

22], targeting the linker sequence between the variable heavy and variable light domains of the scFv.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Antibodies

Biotin-labeled BCMA CAR detection reagent, biotin-labeled CD19 CAR detection reagent, and anti-Biotin APC were obtained from Miltenyi Biotec (Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany). Anti-G4S CAR linker rabbit mAb (E7O2V), anti-Whitlow CAR linker rabbit mAb (E3U7Q) (biotinylated or Alexa Fluor® 647-conjugated), and rabbit IgG XP® isotype-Alexa Fluor® 647 (DA1E) were from Cell Signaling Technology Europe B.V. (Leiden, Netherlands). Anti CD3-FITC Ab (SK7), anti CD45-V500C Ab (2D1), BD FACS™ lysing solution, and BD Pharm Lyse™ lysing buffer were obtained from Becton Dickinson (Heidelberg, Germany). Anti-CD3 Ab and anti-CD28 Ab for T-cell stimulation are from eBioScience (distributed via Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.2. Patient Samples

EDTA- or Heparin-anticoagulated blood was obtained from patients suffering from B cell malignancies (MM, leukemia, or lymphoma) at day 7-23 after application of CAR T-cell therapy with idecabtagene vicleucel (Ide-cel, n=5), ciltacabtagene autoleucel (Cilta-cel, n=5), tisagenlecleucel (Tisa-cel, n=4), axicbtagene ciloleucel (Axi-cel, n=4), brexucabtagene autoleucel (Brexu-cel, n=3), or lisocabtagene maraleucel (Liso-cel, n=2). Ethical approval was granted by the ethics committee of Leipzig University (429/21-lk).

2.3. Separation of PBMC from Whole Blood and T-Cell Subculture

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from patient’s EDTA- or Heparin-anticoagulated blood were obtained by Lymphoprep™ (Progen Biotechnik GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) density centrifugation. After repeated washing with cold PBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) 1 x 106 PBMCs were cultured overnight in 1 ml X-VIVO 10™ media (Lonza, Walkersville, USA) supplemented with 2% heat inactivated human AB-sera (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) and human IL2 (200 U/ml, Peprotech, Hamburg, Germany).

To activate the isolated T-lymphocytes, cells were transferred to a culture plate precoated with anti-human CD3 (5 µg/ml) and costimulated with soluble anti-CD28 Ab (2 µg/ml). After 2 – 3 days, cells were transferred to X-VIVO 10™ media (supplemented with human AB-sera and human IL2) without stimulus. All cell cultures steps were performed at 37°C, 5% CO2.

2.4. Bispecific Antibody Treatment

Blood samples from CAR T-cell treated patients (1 ml) or T-cells subcultured from patients’ blood (1 x 106 cells in 1 ml PBS) were incubated with or without teclistamab (10 µg/ml) for 10 min at RT. Cells were washed twice with 1 ml PBS containing 2% heat inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS; Gibco distributed via Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and analyzed by flow cytometry.

2.5. Antigen-Based CAR T-Cell Detection by Flow Cytometry

Biotin-labeled BCMA CAR detection reagent (2 µl) or biotin-labeled CD19 CAR detection reagent (2µl) were added to EDTA-anticoagulated blood (100 µl) or to T-cells subcultures from patients’ blood (2 x 105 cells in 100 µl PBS) and incubated for 15 min at room temperature (RT). After addition of PBS and centrifugation (400g, 5 min, RT), cells were resuspended in 100 µl PBS and incubated with 2µl anti-biotin-APC Ab, 5µl anti CD3-FITC Ab and 2.5µl anti CD45-V500C Ab for 15 min at RT.

In assays using blood specimens 2 ml of BD FACS™ lysing solution (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) or 2 ml BD Pharm Lyse™ lysing buffer (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) was added for 10 min or 15 min, respectively. After washing and fixation, the cells were analyzed using a FACSLyric flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). FlowJo 10.8.1 software (Becton Dickinson) was used for data analysis.

Cultured T-cells were subsequently washed twice and resuspended in 100 µl PBS with 5 µl of 7-AAD. After 10 min at RT the cells were analyzed using a FACSLyric flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). FlowJo 10.8.1 software (Becton Dickinson) was used for data analysis.

2.6. CAR Linker-Based CAR T-Cell Detection by Flow Cytometry

Biotin-labeled anti-G4S CAR linker mAb (4µl), biotin-labeled anti-Whitlow CAR linker mAb (4 µl), anti-G4S CAR linker-Alexa Fluor® 647 mAb (4µl), anti-Whitlow CAR linker-Alexa Fluor® 647 mAb (4 µl) or rabbit IgG XP® isotype-Alexa Fluor® 647 were added to EDTA-anticoagulated blood (100 µl) or to T-cells subcultures from patients’ blood (2 x 105 cells in 100 µl PBS) and incubated for 15 min at RT. After addition of PBS and centrifugation (400g, 5 min, RT), cells were resuspended in 100 µl PBS and incubated with 5µl anti CD3-FITC Ab, 2.5µl anti CD45-V500C Ab, and 2µl anti-biotin antibody APC (in case of the biotin-labeled Abs) for 15 min at RT.

In assays using blood specimens 2 ml of BD FACS™ lysing solution (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) or 2 ml BD Pharm Lyse™ lysing buffer (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) was added for 10 min or 15 min, respectively. After washing and fixation the cells were analyzed using a FACSLyric flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). FlowJo 10.8.1 software (Becton Dickinson) was used for data analysis.

Cultured T-cells were subsequently washed twice and resuspended in 100 µl PBS with 5 µl of 7-AAD. After 10 min at RT the cells were analyzed using a FACSLyric flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). FACSLyric software (Becton Dickinson) was used for data analysis.

2.7. Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using SigmaPlot software (Systat Software, Erkrath, Germany). Statistical significance was calculated with the Student´s t-test and classified as follows: * p ≤ 0.05: ** p ≤ 0.01; *** p ≤ 0.001.

3. Results

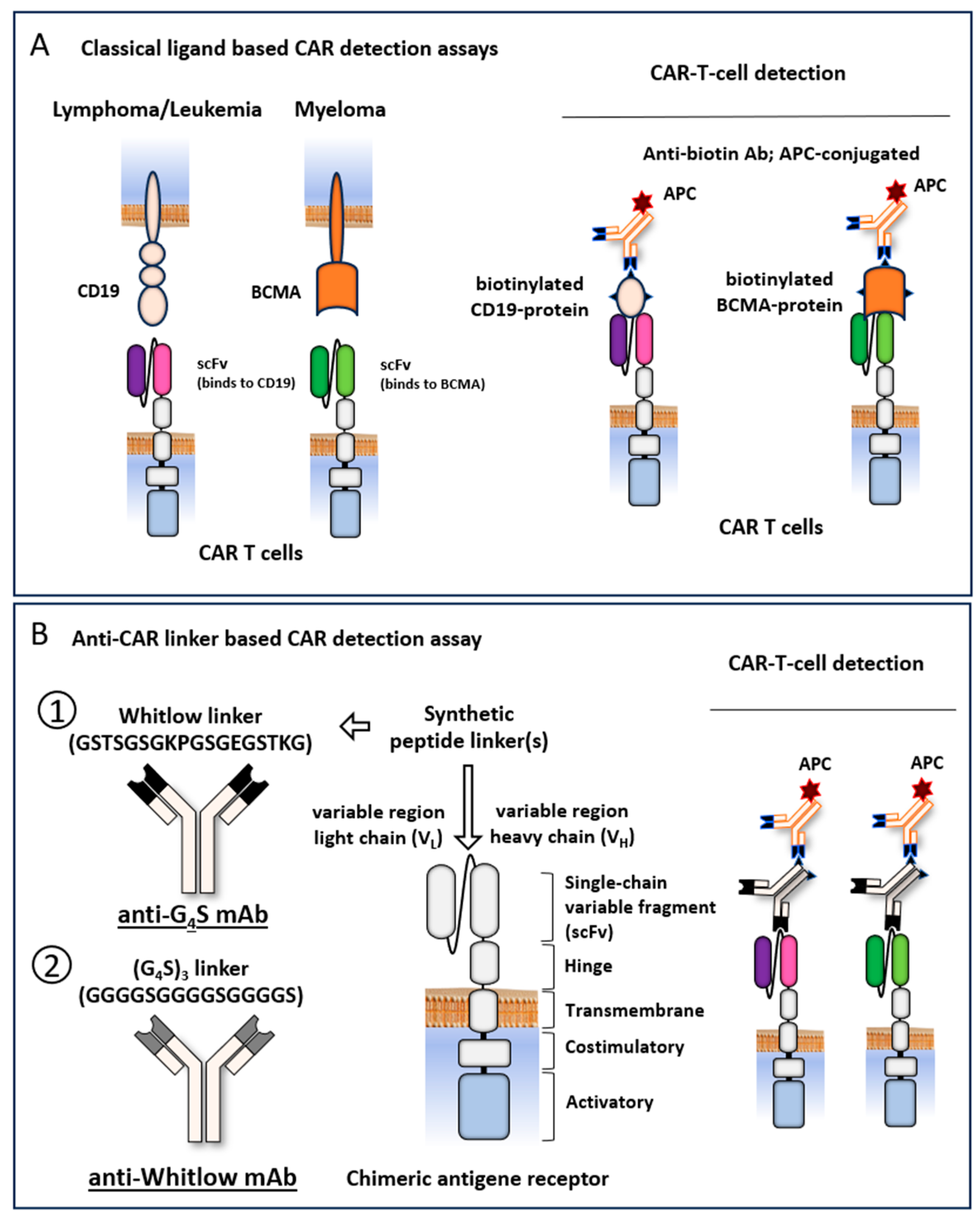

Antigen-based flow cytometric CAR T-cell detection methods are most frequently used for clinical routine diagnostics. These methods are based on the binding of a biotin-labeled recombinant ligand to the antigen-binding site of the CAR, detected by a fluorescent labeled anti-biotin antibody. For each CAR recognizing a different target-antigen a separate biotin-labeled recombinant antigen is required (

Figure 1A). Most scFv-based CARs contain either a Whitlow linker (GSTSGSGKPGSGEGSTKG) or a (G

4S)

3 linker (GGGGSGGGGSGGGGS), targeted by anti-Whitlow mAb or by anti-G

4S mAb , respectively [

13,

21,

22] (

Figure 1B). To test whether these antibodies allow for an universal CAR detection in

real life, we performed flow cytometry CAR detection analyses of all approved CD19 and BCMA targeting CAR T-cell products, using isolated lymphocyte specimens from patient’s blood (

Figure 2A).

The percentage of anti-CD19 CAR T-cells detected by biotinylated anti-Whitlow mAb from lymphoma patients treated with Brexu-cel, Liso-cel and Axi-cel was comparable to that obtained with CD19 antigen-based CAR detection assays (96 ± 2%; 96 ± 4%; and 87 ± 15%; respectively) (

Figure 2B). Using biotinylated anti-G4S mAb, the percentage of Tisa-cel CAR T-cells detected in blood cell isolates from treated leukemia patients, only amounted to 68 ± 3% (

Figure 2B). The use of fluorochrome-conjugated anti-CAR linker mAbs results in a reduced sensitivity of 79 ± 6%; 83 ± 15%; 62 ± 24%; and 61 ± 5% for Brexu-cel, Liso-cel, Axi-cel, and Tisa-cel, respectively (

Figure 2C). These results indicate that detection with an anti-biotin secondary antibody amplifies the signal with respect to fluorochrome-conjugated anti-inker mAbs.

We furthermore performed flow cytometry CAR detection analyses of all approved BCMA CAR T-cell products (Ide-cel, and Cilta-cel) (

Figure 2A-C). As result, anti-BCMA CAR T-cells were also successfully detected by anti-Whitlow mAb from myeloma patients treated with Ide-cel. In comparison to the results obtained with BCMA antigen-based CAR detection assays the percentage of detected CAR T-cells was reduced (69 ± 10% and 53 ± 10% for biotinylated and Alexa 647-conjugated anti-Whitlow mAb, respectively). However, the detection of Cilta-cel (featuring two single domain antibodies, connected by a single G4S linker) was not possible by any CAR linker mAb.

As a technical remark, CAR detection with Alexa-conjugated anti-G

4S mAb leads to false positive results in whole blood specimens, if red blood cells are lysed by BD FACS™ Lysing solution (

Figure S1). This phenomenon occurs in all analyzed cells, but not with the corresponding Alexa-conjugated isotype, anti-CD3 Ab and anti-CD45 Ab. We speculate that an artificial binding site for that antibody may be created through simultaneous fixation by the lysing buffer in the diagnostic routine protocol. This artifact can be avoided by using BD Pharm Lyse™ lysing solution, devoid of fixation reagent (

Figure S1).

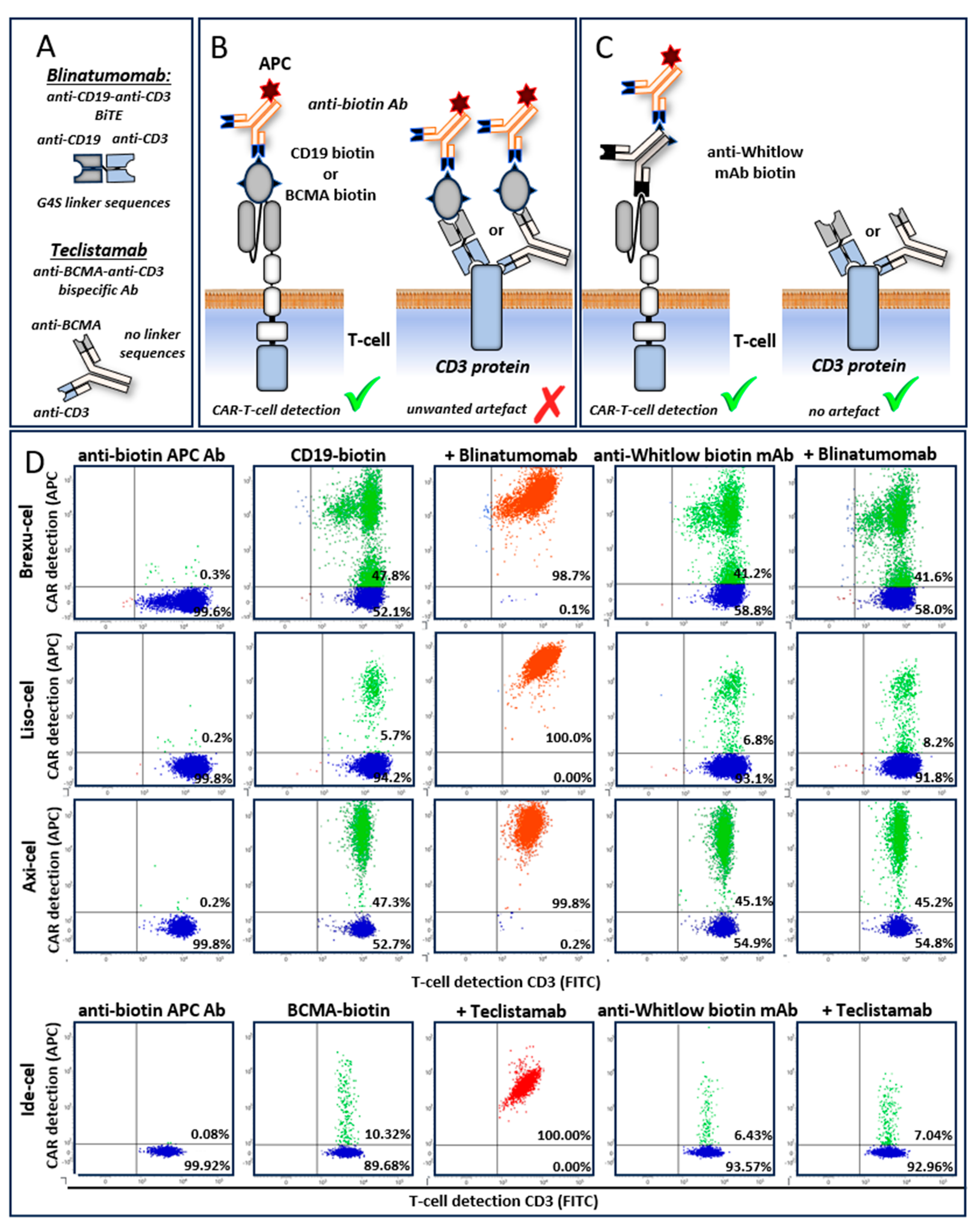

We next determined whether CAR linker mAb allows for specific detection of CAR T-cells by the simultaneous presence of bsAbs/BiTE recognizing the same tumor antigen (e.g., CD19xCD3 BiTE blinatumomab and anti-CD19 CAR T-cells).

Here were show, that detection of anti-CD19 CAR T-cells with biotinylated anti-Whitlow mAbs in blood specimens of lymphoma patients treated with Brexuc-cel is unaffected by the presence or absence of blinatumomab (41% versus 42%, respectively), in contrast to the CD19-based CAR detection assay (artificially 99% versus 48%, respectively) (

Figure 3B). Similar results were obtained using Liso-cel and Axi-cel anti-CD19 CAR T-cells and blinatumomab (

Figure 3B). Furthermore, the detection of a BCMA specific CAR T-cells after prior treatment with BCMAxCD3 bsAb teclistamab is also impaired if BCMA antigen-based CAR detection reagents are used. We show that Ide-cel (anti-BCMA) CAR T-cell detection by biotinylated anti-Whitlow Abs is also unaffected in the presence or absence of teclistamab (7% versus 6%, respectively), in contrast to the BCMA-based CAR detection assay (artificially 100% versus 10%, respectively) (

Figure 3B).

Finally, the real-world feasibility for anti-CAR linker antibodies is identical to classical CAR detection, but the costs are considerably lower. In our laboratory, the costs per application are € 40.80 and € 30.90 for the classical CD19 and BCMA based CAR detection assays, respectively, in contrast to € 23.00 and € 21.83 for anti-Whitlow and anti-G4S linker mAb based CAR detection assay, respectively.

4. Discussion

In the domain of cellular immunotherapy, the concurrent administration of bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTEs) or bispecific antibodies (bsAbs) and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies targeting the same antigen presents a significant challenge for the accurate monitoring of CAR T-cell populations. Monitoring of a CAR T-cell therapy during the presence of BiTEs/bsAbs recognizing the same antigen is not possible by antigen-based CAR detection methods. The BiTEs/bsAbs bind to CD3 on all T-cells irrespective if they carry a CAR or not. In this case, antigen-based CAR detection does not only bind to the CAR but also to the antigen-specific free arm of the bound BiTEs/bsAbs. These non-selective binding results in the misidentification of non-CAR-bearing T-cells as CAR-positive, thereby producing false positive results in clinical therapy monitoring.

For clinical diagnostics, this is a serious problem as the combination of BiTE/bsAbs and CAR T-cells enter the clinic either as bridging therapy or as combined therapeutic approaches in clinical practice or clinical trials, respectively [

19]. We still observed in our clinical routine diagnostic false-positive results on day 9 after the last teclistamab treatment.

The removal of the BiTEs/bsAbs from the cells before detecting the CAR might solve that problem. However, in-vitro application of reducing agent dithiothreitol [

23] failed to completely disrupt teclistamab binding during CAR detection [

12]. Alternative CAR-detection strategies based on Protein L, polyclonal anti-F(ab) fragment Abs (

Figure S2), and anti-isotype antibodies are less specific [

24], and would also label BiTEs/bsAbs bound to all T-cells in most cases. In addition, anti-idiotype antibodies are only available for the detection of a limited number of CARs [

12,

24].

Here we evaluated to our knowledge for the first-time anti-CAR linker specific monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) as a CAR detection strategy to circumvent artificial staining of T-cells in the presence of corresponding BiTEs/bsAbs. These mAb targeting the linker sequence between the variable heavy and variable light domains of the scFv [

13,

21,

22]. The scFv of the clinically applied CARs mostly contain a Whitlow protein linker (Ide-cel, Axi-cel, Brexu-cel, and Liso-cel) and were specifically detected by anti-Whitlow mAb. Tisa-cel is the only one CAR product, containing a (G

4S)

3 linker and was specifically detected by anti-G

4S mAb. Surprisingly, the detection of Cilta-cel is not possible with anti-CAR linker antibodies. Cilta-cel uses instead of a scFv two nanobodies (single domain antibody, naturally found in sharks and camels) to recognize two epitopes of BCMA [

25,

26]. Both nanobodies are connected by a G

4S linker instead of a (G

4S)

3 linker, which was not recognized by the G

4S mAbs. It is conceivable that either this short motif can’t be recognized by the antibody in general or that it may not be accessible due to protein folding.

Compared to ligand-based assays (Miltenyi), the use of biotinylated anti-CAR linker antibodies resulted in similar CAR T-cell detection rate for Axi-cel, Brexu-cel and Liso-cel, respectively. Both, Ide-cel and Tisa-cel CARs show a distinct lower sensitivity if detected by anti-CAR linker antibodies. It might be that CD8a hinge domain, exclusively present in both CARs, may decrease antibody accessibility to the linker by altered scFv conformation.

In general, an indirect CAR detection method using biotinylated antibodies is more sensitive, as it allows the binding of multiple fluorochrome conjugated anti-biotin Abs, which results in signal amplification.

Our data clearly shows that the specificity of anti-CAR linker antibodies is unaffected by the simultaneous presence of BiTEs/bsAbs targeting the same antigen as the CAR (Axi-cel, Liso-cel, Brexu-cel/blinatumomab and Ide-cel/teclistamab). These results conclusively demonstrate diagnostic superiority compared to the standard ligand-based detection assays by allowing clinical CAR monitoring in most combination therapies. As a limitation it should be noted, that Tisa-cel CARs (G

4S)

3 linker are not specifically detectable with anti-G

4S linker mAb in combination with blinatumomab, as this synthetic BiTE even contains a (G

4S)

3 linker in its scFv [

27,

28].

In conclusion, application of anti-CAR linker mAb provides the following benefits: a highly specific CAR detection, recognition of a broad range of CARs, easy incorporation into multiparametric flow panels, and considerably lower assay cost compared to ligand-based CAR detection assays by identical workload. In contrast to classical ligand-based CAR detection, they are applicable for blood analysis of patients simultaneously treated with both BiTEs/bsAbs and CAR T-cells, targeting the same antigen with just one exception. Nevertheless, we also identified the following restrictions for the application of anti-CAR linker mAb: CARs containing a monomeric G4S linker, are not recognized be anti-G4S linker mAbs, the specificity of CAR detection is influenced by BiTEs containing the same linker as the CAR, and in some cases the sensitivity (percentage of positive cells) is distinct lower compared to ligand-based CAR detection assays.

In view of the increasing number of bispecific antibodies and CAR T-cell products being applied [

29,

30], anti-CAR linker antibodies are a new valuable tool to detect CAR expression.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: CAR detection with Alexa-conjugated anti-G4S mAb leads to false positive results in whole blood specimens, if red blood cells are lysed by BD FACS™ Lysing solution; Figure S2: CAR T-cell detection by anti-F(ab) fragment antibodies leads to false positive results in the presence of bsAbs recognizing the same antigen as the CAR;.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F., A.G., S.S., and D.S; methodology, K.W., S.S., M.F., A.B.; validation, A.G., S.S., C.K., and M.F.; formal analysis, K.W., and S.S.; resources, U.K., C.K., V.V., D.S., and U.P.; data curation, K.W., and S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.F.; writing—review and editing, A.G., C.K., D.S, V.V., M.M., U.P., S.S, K.W., A.B., and U.K.; visualization, M.F., A.G., and C.K.; supervision, C.K., U.K., and U.P.; project administration, M.F.; funding acquisition, M.F., and U.K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was partially funded by the Fraunhofer Gesellschaft (Grant No. 600 071; SME REPRO project) and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (under the funding code 03ZU1111KA) as part of the Clusters4Future cluster SaxoCell which received funding from the Innovative Medicine Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking (grant agreement No. 853988) and by the project CREATIC funded from the European Union’s Horizon Europe Coordination and Support Action under the Grant agreement number 101059788. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Leipzig (Reference number 043/19-ek 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

For original data, please contact the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ronald Weiss and Bettina Glatte for supervision and technical support, and Sunna Hauschildt for critical reading the manuscript. The authors acknowledge support from the German Research Foundation (DFG) and Universität Leipzig within the program of Open Access Publishing.

Conflicts of Interest

M.M., V.V. and U.P. receive honoraria from Janssen and BMS. M.M. is also supported by Janssen Research. U.K. is a consultant in immunooncology for AstraZeneca, Affimed, Glycostem, GammaDelta and Zelluna, and has collaborations with Novartis and Miltenyi Biotec regarding the production of CAR T-cells. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Selim, A. G.; Minson, A.; Blombery, P.; Dickinson, M.; Harrison, S. J.; Anderson, M. A. CAR-T cell therapy: practical guide to routine laboratory monitoring. Pathology 2021, 53(3), 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Yin, H.; Zhao, X.; Jin, D.; Liang, Y.; Xiong, T.; Li, L.; Tang, W.; Zhang, J.; Liu, M.; Yu, Z.; Liu, H.; Zang, S.; Huang, Z. High efficacy and safety of CD38 and BCMA bispecific CAR-T in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Journal of experimental & clinical cancer research : CR, 2022; 41, (1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, S. T.; Dholaria, B. R.; Sengsayadeth, S. M.; Savani, B. N.; Oluwole, O. O. Role of bridging therapy during chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy. EJHaem 2022, 3 (Suppl 1), 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullard, A. FDA approves first BCMA-targeted CAR-T cell therapy. Nature reviews. Drug discovery 2021, 20(5), 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westin, J. R.; Kersten, M. J.; Salles, G.; Abramson, J. S.; Schuster, S. J.; Locke, F. L.; Andreadis, C. Efficacy and safety of CD19-directed CAR-T cell therapies in patients with relapsed/refractory aggressive B-cell lymphomas: Observations from the JULIET, ZUMA-1, and TRANSCEND trials. American journal of hematology 2021, 96(10), 1295–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maude, S.L.; Laetsch, T.W.; Buechner, J.; Rives, S.; Boyer, M.; Bittencourt, H.; Bader, P.; Verneris, M.R.; Stefanski, H.E.; Myers, G D.; et al. Tisagenlecleucel in Children and Young Adults with B-Cell Lymphoblastic Leukemia. The New England journal of medicine 2018, 378(5), 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, B. D.; Ghobadi, A.; Oluwole, O. O.; Logan, A. C.; Boissel, N.; Cassaday, R. D.; Leguay, T.; Bishop, M. R.; Topp, M. S.; Tzachanis, D.; O’Dwyer, K. M.; Arellano, M. L.; Lin, Y.; Baer, M. R.; Schiller, G. J.; Park, J. H.; Subklewe, M.; Abedi, M.; Minnema, M. C.; Wierda, W. G.; DeAngelo, D. J.; Stiff, P.; Jeyakumar, D.; Feng, C.; Dong, J.; Shen, T.; Milletti, F.; Rossi, J. M.; Vezan, R.; Masouleh, B. K.; Houot, R. KTE-X19 for relapsed or refractory adult B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: phase 2 results of the single-arm, open-label, multicentre ZUMA-3 study. Lancet (London, England), 2021, 398 (10299), 491–502. [CrossRef]

- Sadelain, M.; Brentjens, R.; Rivière, I. The basic principles of chimeric antigen receptor design. Cancer discovery 2013, 3(4), 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murata, K.; McCash, S. I.; Carroll, B.; Lesokhin, A. M.; Hassoun, H.; Lendvai, N.; Korde, N. S.; Mailankody, S.; Landau, H. J.; Koehne, G.; Chung, D. J.; Giralt, S. A.; Ramanathan, L. V.; Landgren, O. Treatment of multiple myeloma with monoclonal antibodies and the dilemma of false positive M-spikes in peripheral blood. Clinical biochemistry 2018, 51, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munshi, N. C.; Anderson, L. D.; Shah, N.; Madduri, D.; Berdeja, J.; Lonial, S.; Raje, N.; Lin, Y.; Siegel, D.; Oriol, A.; Moreau, P.; Yakoub-Agha, I.; Delforge, M.; Cavo, M.; Einsele, H.; Goldschmidt, H.; Weisel, K.; Rambaldi, A.; Reece, D.; Petrocca, F.; Massaro, M.; Connarn, J. N.; Kaiser, S.; Patel, P.; Huang, L.; Campbell, T. B.; Hege, K.; San-Miguel, J. Idecabtagene Vicleucel in Relapsed and Refractory Multiple Myeloma. The New England journal of medicine 2021, 384(8), 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Rivière, I. Clinical manufacturing of CAR T cells: foundation of a promising therapy. Molecular therapy oncolytics 2016, 3, 16015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glatte, B.; Wenk, K.; Grahnert, A.; Friedrich, M.; Merz, M.; Vucinic, V.; Fischer, L.; Reiche, K.; Alb, M.; Hudecek, M.; Franz, P.; Fricke, S.; Platzbecker, U.; Koehl, U.; Sack, U.; Boldt, A.; Hauschildt, S.; Weiss, R. Teclistamab impairs detection of BCMA CAR-T cells. Blood advances 2023, 7(15), 3842–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sievers, S. A.; Kelley, K. A.; Astrow, S. H.; Bot, A.; Wiltzius, J. J. Abstract 1204: Design and development of anti-linker antibodies for the detection and characterization of CAR T cells. Cancer Research 2019, 79 (13_Supplement), 1204. [CrossRef]

- Blache, U.; Weiss, R.; Boldt, A.; Kapinsky, M.; Blaudszun, A.-R.; Quaiser, A.; Pohl, A.; Miloud, T.; Burgaud, M.; Vucinic, V.; Platzbecker, U.; Sack, U.; Fricke, S.; Koehl, U. Advanced Flow Cytometry Assays for Immune Monitoring of CAR-T Cell Applications. Frontiers in immunology 2021, 12, 658314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miltenyi Biotec. Datasheet BCMA CAR Detection Reagent, human, Biotin: Order no. 130-126-090 140-005-815.02. https://www.miltenyibiotec.com/upload/assets/IM0026786.PDF (accessed 2022-11-25).

- Einsele, H.; Borghaei, H.; Orlowski, R. Z.; Subklewe, M.; Roboz, G. J.; Zugmaier, G.; Kufer, P.; Iskander, K.; Kantarjian, H. M. The BiTE (bispecific T-cell engager) platform: Development and future potential of a targeted immuno-oncology therapy across tumor types. Cancer 2020, 126(14), 3192–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillarisetti, K.; Powers, G.; Luistro, L.; Babich, A.; Baldwin, E.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Mendonça, M.; Majewski, N.; Nanjunda, R.; Chin, D.; Packman, K.; Elsayed, Y.; Attar, R.; Gaudet, F. Teclistamab is an active T cell-redirecting bispecific antibody against B-cell maturation antigen for multiple myeloma. Blood advances 2020, 4(18), 4538–4549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Medicines Agency. Tecvayli epar product information. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/tecvayli-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed 2023-03-23).

- Xiao, X.; Wang, Y.; Zou, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Xin, X.; Tu, S.; Li, Y. Combination strategies to optimize the efficacy of chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy in haematological malignancies. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 954235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves teclistamab-cqyv for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-teclistamab-cqyv-relapsed-or-refractory-multiple-myeloma (accessed 2022-11-25).

- Huston, J. S.; Levinson, D.; Mudgett-Hunter, M.; Tai, M. S.; Novotný, J.; Margolies, M. N.; Ridge, R. J.; Bruccoleri, R. E.; Haber, E.; Crea, R. Protein engineering of antibody binding sites: recovery of specific activity in an anti-digoxin single-chain Fv analogue produced in Escherichia coli. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1988, 85(16), 5879–5883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitlow, M.; Bell, B. A.; Feng, S. L.; Filpula, D.; Hardman, K. D.; Hubert, S. L.; Rollence, M. L.; Wood, J. F.; Schott, M. E.; Milenic, D. E. An improved linker for single-chain Fv with reduced aggregation and enhanced proteolytic stability. Protein engineering 1993, 6(8), 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapuy, C. I.; Aguad, M. D.; Nicholson, R. T.; AuBuchon, J. P.; Cohn, C. S.; Delaney, M.; Fung, M. K.; Unger, M.; Doshi, P.; Murphy, M. F.; Dumont, L. J.; Kaufman, R. M. International validation of a dithiothreitol (DTT)-based method to resolve the daratumumab interference with blood compatibility testing. Transfusion 2016, 56(12), 2964–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Huang, J. The Chimeric Antigen Receptor Detection Toolkit. Frontiers in immunology 2020, 11, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berdeja, J.G.; Madduri, D.; Usmani, S.Z.; Jakubowiak, A.; Agha, M.; Cohen, A.D.; Stewart, A.K.; Hari, P.; Htut, M.; Lesokhin, A.; et al. Ciltacabtagene autoleucel, a B-cell maturation antigen-directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (CARTITUDE-1): a phase 1b/2 open-label study. Lancet (London, England), 2021; 398, 10297, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Jiang, G. The journey of CAR-T therapy in hematological malignancies. Molecular cancer 2022, 21(1), 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woessner, PhD, MS, Department of Pathology, St Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, David. Blinatumomab: A CD19/CD3-Bispecific T-Cell Engaging (BiTE) Antibody for B-Cell Leukemia Immunotherapy—A First-in-Class Agent that Directs T Cells to Tumor Cell Targets. In Goodman & Gilman’s: The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 12e; Brunton, L. L., Chabner, B. A., Knollmann, B. C., Eds.; McGraw-Hill Education, 2015.

- Brunton, L. L., Chabner, B. A., Knollmann, B. C., Eds. Goodman & Gilman’s: The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 12e; McGraw-Hill Education, 2015.

- Strassl, I.; Schreder, M.; Steiner, N.; Rudzki, J.; Agis, H.; Künz, T.; Müser, N.; Willenbacher, W.; Petzer, A.; Neumeister, P.; Krauth, M. T. The Agony of Choice-Where to Place the Wave of BCMA-Targeted Therapies in the Multiple Myeloma Treatment Puzzle in 2022 and Beyond. Cancers 2021, 13 (18). [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Dahiya, S.; Patel, S. A. Challenges and solutions to superior chimeric antigen receptor-T design and deployment for B-cell lymphomas. British journal of haematology 2023, 203(2), 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).