1. Introduction

Canine lymphomas (CLs) are among the most commonly diagnosed neoplasms in the canine population. They primarily occur in animals between 6 and 9 years of age, regardless of sex [

1]. Although certain breeds exhibit genetic predisposition to the development of these malignancies [

2], lymphomas can arise in dogs of any breed. The estimated incidence of CLs ranges from approximately 20 to 100 cases per 10,000 animals [

3]

CLs are categorized into three main groups according to the size of neoplastic cells: small-cell lymphomas (with a slow, indolent course), intermediate-cell lymphomas (of moderate aggressiveness), and large-cell lymphomas (characterized by a rapid and aggressive progression) [

4] An essential component of classification is also immunophenotypic analysis [

5] and the stage of disease progression, incorporating both clinical and histological staging, which facilitates precise prognostication and treatment optimization [

6]. The phenotypic distribution of CLs observed in dogs closely mirrors that seen in humans. The majority of CLs (78%) are of B-cell origin, whereas a smaller proportion are identified as T-cell lymphomas (10%) or classified as non-B, non-T-cell lymphomas (12%) [

7]. The growing demand for more effective therapeutic approaches for CLs underscores their potential as a valuable translational research model [

8,

9]. Namely, the studies on CLs contribute to a deeper understanding of oncogenesis and the development of innovative therapies in humans [

10].

In veterinary medicine, CLs are treated with multidrug chemotherapy protocols that are adaptations of therapies employed in human medicine. One of the most commonly used regimens is the CHOP protocol, which includes: cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin (hydroxydaunorubicin), vincristine (Oncovin), and prednisone/prednisolone [

11]. The MOPP chemotherapy protocol, comprising mechlorethamine, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone, has been utilized in cases resistant to initial treatments [

12]. The CHOP and MOPP chemotherapy protocols used in the treatment of CLs can be administered either with or without the addition of L-asparaginase [

13]

In the late 1990s, rituximab [

14]—a monoclonal antibody targeting the CD20 protein, which is present on the surface of most B-cell-derived cancer cells—was introduced to the pharmaceutical market. Rituximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody that consists of mouse-derived variable regions targeting CD20 and a human IgG1 constant/Fc region responsible for immune system activation. Its primary mechanism of action involves the depletion of CD20-expressing B cells, mainly through antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) [

15]. Long-term clinical studies and observations have confirmed that combination therapy integrating chemotherapy with targeted treatment (R-CHOP) significantly improves treatment outcomes compared to standard chemotherapy alone (CHOP). Analyses have demonstrated that R-CHOP is associated with a higher overall response rate (85.1% vs. 72.3%), an increased complete remission rate (29.5% vs. 15.6%), and significantly prolonged progression-free survival (33.1 vs. 20.2 months). Furthermore, the use of R-CHOP translates into a higher 3-year overall survival rate (82.5% vs. 71.9%) [

16].

Following the successes of rituximab therapy, attempts were made to adapt this treatment for canine lymphoma, to integrate it into veterinary clinical practice [

17]. However, due to differences in the amino acid sequences of the CD20 protein between humans and dogs, and the resulting lack of conservation of the rituximab epitope in the canine protein, the direct application of mAbs targeting human CD20 in canine therapy has proven unfeasible [

18]. To address this limitation, caninized anti-CD20 antibodies were developed for the treatment of B-cell lymphomas in dogs. The antibodies 1E4-cIgGB and 1E4-cIgGC (anti-canine CD20) demonstrated positive outcomes in both in vitro assays and in vivo studies using a xenograft mouse model of the canine lymphoma cell line CLBL1. Furthermore, they were shown to significantly deplete B-cell levels in healthy Beagle dogs [

15,

17,

19].

In the context of alternative therapeutic targets, MHC class II (MHC-II) has emerged as a promising option for the treatment of lymphomas. Compared to CD20, MHC-II–targeted therapy has demonstrated significant potential, particularly in B-cell lymphomas, where in both humans and dogs, MHC-II DR is expressed on most lymphoid neoplasms originating from precursor cells at levels higher than CD20 [

20]

Classical MHC-II proteins are constitutively expressed on antigen-presenting cells, including monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and B cells, where they play a pivotal role in presenting peptide antigens derived from exogenous proteins to T cells. MHC-II is essential for antigen presentation to CD4(+) T lymphocytes [

21] whose role in antitumor immunity is increasingly recognized. Moreover, reduced MHC-II molecule expression has been correlated with poor survival outcomes in patients with B-cell lymphoma [

20].

In human hematologic malignancies, three murine antibodies targeting human leukocyte antigen DR (HLA-DR) – Lym-1, h1D10, and L243 (IMMU-114) – have demonstrated therapeutic efficacy. IMMU-114 has also been administered to dogs with lymphoma without causing renal insufficiency or generalized immune deficiency, contrary to initial concerns based on DLA-DR expression profiles.

In the context of veterinary and comparative studies on CL-associated antigens, two novel mouse mAbs targeting pan dog leukocyte antigen DR (DLA-DR) epitopes, designated B5 and E11, have been developed [

22]. These antibodies are species-specific and bind to DLA-DR antigens with significantly higher affinity than IMMU-114. In vivo studies conducted using the B5 mAb demonstrated therapeutic efficacy using immunodeficient NOD-SCID mice xenotransplanted with the canine CLBL-1 cell line (a canine model of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) [

23].

Engineering smaller antibody fragments has shown an improvement in their tumor uptake rate and intratumoral distribution, while maintaining the full specificity and binding affinity to the antigen characteristic of the intact antibodies [

24]. Furthermore, the absence of the Fc region has additional implications, as fragments can exert therapeutic effects solely through binding to either the ligand or receptor; they do not trigger Fc-dependent functions, such as antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) or complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) [

25].

To study therapeutic efficacy and adverse effects associated with anti-DLA-DR cancer immunotherapy, in the present study, we assessed E11 mAb Fab and F(ab’)2 fragments in an in vivo mouse model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Enzymatic Fragmentation of Antibodies

Monoclonal antibody at 1mg/ml was subjected to enzymatic fragmentation using immobilized papain resin (Immobilized Papain Agarose Resin, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in the presence or absence of 1mM cysteine for generating Fab or F(ab’)2 fragments, respectively. The enzymatic reactions were carried out for 5 hours at 37 °C. Then, Protein A affinity chromatography was used to trap the Fc antibody fragments as well as undigested mAbs. SDS-PAGE was used to estimate the purity of the fragment preparation.

2.2. Downmodulation of DLA-DR upon Binding of E11 mAb to CLBL1 and CLB70 Cell Lines

The cells were incubated with 10μg/ml of full E11 mAb or recombinant E11-scFv fragments for 4 hrs at 37 °C. Then, after washing the cells with ice-cold FACS buffer (Phosphate Buffered Saline supplemented with 2% Fetal Bovine Serum and 0.05% NaN3), the cells were stained with FITC-labeled B5 mAb for 20 minutes on ice and analyzed on BD FACS Calibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

2.3. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assessment of E11-Fab and E11-F(ab’)2 Towards CLBL1 and CLB70 Cell Lines

The cells were incubated with antibodies and their fragments at concentration 10 ug/ml for 48 hours, then the cells were fixed in 75% ethanol at 4 °C 30 min, and then incubated with 50 ng/mL PI staining solution and 0.2 mg/mL RNase in the dark overnight at 4 °C. Data was acquired on a BD LSRFortessa™ flow cytometer (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and analyzed with CellQuest™ 3.1f software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

2.4. Development of CLBL1 Cell Line Stably Transduced with a Secreted Nanoluciferase (CLBL1-sLuc)

The CLBL1 cell line was kindly provided by Dr. Barbara Rutgen from the Institute of Immunology, Department of Pathobiology, University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna, Austria. The cells were cultured in RPMI1640 medium (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 20% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Biowest, Nuaillé, France) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Transduction of the CLBL1 cells to confer the ability to produce secreted luciferase (CLBL1-sLuc) was performed using a lentiviral system (GNT-LVP377-PBS, Holzel-biotech, Germany). Lentiviral particles were added to the cells (1 × 10^6) at a ratio of 10 μl of virus per 0.5 ml of cells. After 72 hours post-transduction, antibiotic selection was initiated by changing the culture medium to complete medium containing puromycin (Puromycin dihydrochloride 10 mg/ml, Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at a concentration of 1 µg/ml.

Selection of transduced cells was carried out based on their resistance to puromycin for a period of 7 days, as well as by verifying the expression of the introduced gene, specifically by measuring the secreted luciferase production capacity. Luminescence of the cell culture supernatant was measured using the Pierce Cypridina Luciferase Glow Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Luminescence measurements were conducted starting 72 hours post-transfection. A total of 20 µl of culture medium was transferred to each well of a black 96-well plate, followed by the addition of 50 µl of working solution to each well. The readings were taken 10 minutes after the addition of reagents, once the luminescent signal had stabilized.

Luminescence measurements were conducted starting 72 hours post-transfection. A total of 20 µl of collected culture medium was transferred to each well of a black 96-well plate, followed by the addition of 50 µl of working solution to each well. The readings were taken 10 minutes after the addition of reagents, once the luminescent signal had stabilized. The readout was performed using a microplate reader (Spark; Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland).

2.5. Establishment of CLBL1-sLuc In Vivo Growth in NOD-SCID Immunodeficient Mice

The Local Ethical Committee approved all animal experiments presented in this study (Approval no. 04/2023P1). NOD/SCID [

26] mice were purchased from Janvier Labs (Le Genest-Saint-Isle, France) and housed in a standard SPF laboratory environment with a 12-hour light/dark cycle, providing ad libitum access to food and water. The experiment was conducted on 34 mice, divided into groups of 8 animals (except for a group of 2 sham-treated naive mice). At the time of the experiment, the mice were 8 weeks old.

At the time of cell collection, the cell culture reached 80% confluence. The culture medium was collected and centrifuged at 300 g for 5 minutes to pellet the cells. The cells were then resuspended in PBS, and the centrifugation and washing were repeated three times. Finally, the cells were resuspended in PBS at a concentration of 75 × 106 cells/ml. The average cell viability, measured using trypan blue, was 92-94%. A 27-gauge needle and a 1 ml syringe were used for cell injection. The cells were administered intravenously through the caudal vein (vena caudalis) as a single injection on day “0” of the experiment. To achieve proper visualization of the vein, the animals were placed in a cage with a heating lamp positioned above them. Subsequently, the mice were transferred to a restraining device that allows easy access to the tail vein. Each mouse received 15 × 106 CLBL1-sLuc cells in 200 μL of PBS.

2.6. Antibody Infusion to Mice

On the fourth day after transplanting CLBL1-sLuc cells, the NOD-SCID mice were stratified into a control group, which did not receive any therapeutic antibodies, and experimental groups treated with either full E11 antibody, E11-Fab fragments, or E11-F(ab’)2 fragments. Randomization was performed based on individual body weight, ensuring that comparable average body weights were achieved within each group.

The first administration of the antibodies occurred on day four following the injection of tumor cells. Throughout the experiment, the antibodies were administered seven times, twice per week. The specific days of administration are indicated in the experimental timeline (blue arrows). The antibody preparations were at a concentration of 1 mg/1 ml. Prior to each administration, the mice were weighed, and the dose for each individual was calculated based on their body weight. The dosing regimen was 1 mg per 1 kg of body weight (1 μg/g body weight). After weighing the mice [g], the appropriate volume of the antibody preparation [μl] was measured and the dose was adjusted with sterile saline for injection to a final volume of 100 μl.

The control group received a similarly prepared suspension, but containing mouse irrelevant antibodies of the same isotype as E11 mAb (IgG2a) that were not directed against antigens expressed on the administered tumor cells.

The preparations were administered intraperitoneally using a 27-gauge needle and a 1 ml syringe. After proper restraint of the mice to facilitate access to the abdominal cavity, the drugs were administered in a volume of 100 μl to the lower left quadrant of the abdomen, slightly off the midline.

2.7. Monitoring Tumor Progression in Xenotransplanted NOD-SCID Mice

Due to the ability of the cells to produce secreted luciferase [

27] it became possible to monitor tumor progression by measuring luciferase released from tumor cells into blood. Additionally, during the experiment, body weight changes of the mice were monitored, and regular clinical observations of the animals’ health status were conducted. After the experiment, bone marrow isolation was performed, and the luminescence levels were measured in the marrow suspensions as well.

The experiment was designed to last for three weeks following the implantation of tumor cells. In a subset of control irrelevant IgG treated mice, approximately 16 days post-procedure, a marked deterioration in clinical condition was observed, prompting the early euthanasia of these animals humanely. Euthanasia was performed by placing the mice in an anesthetic chamber, where a flow of 5% isoflurane was administered for a minimum of 5 minutes. Once full sedation was achieved, the mice were euthanized by decapitation [

28,

29]. During necropsy, a thorough examination of the internal organs was conducted, including an evaluation of their gross morphology and any pathological changes. Additionally, bone marrow was carefully extracted for subsequent analysis.

2.8. Luminescence Measurements

For the measurement of luminescence variability in blood, samples were collected from the tail vein of the mice. The animals were placed under a heating lamp, and once a stress response was observed, characterized by the animal distancing itself from the heat source, they were transferred to the restrainer. Blood collection was performed through a single puncture of the tail vein using a 30G needle. For the measurement of secreted luciferase activity produced by tumor cells, analysis can be performed in all biological fluids as well as in homogenates obtained post-mortem from tissues. The results for a given sample of collected biological fluids were obtained through luminescence measurements, conducted according to the following protocol: to 10 µl of the sample, 50µl of reagent Cypridina Luciferase Glow Assay Working Solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was added. Luminescence readings were recorded using a luminometer within 10 minutes after mixing the two components. Measurements were performed using the GloMax® 20/20 luminometer (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The obtained values are expressed as relative light units [RLU].

2.9. Bone Marrow Isolation and Analysis

Murine bone marrow was isolated by mechanical disruption of the femurs. The femurs were separated from the hip joint, detached from the tibia, and the surrounding muscle tissue was excised. Bones were disrupted in 3 mL sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to release bone marrow cells. Following thorough homogenization, the suspension was passed through a 70 µm cell strainer mounted on a 50 mL Falcon tube, with additional PBS added to maximize cell recovery. At this stage, cells were resuspended in equal volumes of PBS, and a fraction was collected for direct luminescence analysis in bone marrow preparations. The remaining cell suspension was centrifuged at 350 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. The pellet was resuspended in 1.5 ml Ammonium-Chloride-Potassium lysis buffer (CTS™ ACK Lysing Buffer, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and incubated for 3 min at room temperature to lyse residual red blood cells. Lysis was quenched by adding PBS to a final volume of 15 mL, followed by centrifugation under the same conditions. The final cell pellet was resuspended in a FACS buffer (PBS supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum and 0,05% sodium azide) for flow cytometry. Cell staining for analysis by flow cytometry was performed using primary anti-dog MHC class II antibodies and secondary Phytoerythrin (PE)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibodies. The control group was stained with irrelevant mouse IgG2a and secondary antibodies as above. The analysis was conducted using BD FACSLyric™ flow cytometer (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The primary B5 antibody [

1] was applied to the cell suspension in the form of hybridoma cell culture supernatant in a volume of 200 µl. Incubation was performed on ice for 30 minutes, followed by two washes with FACS solution. The cell pellets were then resuspended in 200 µl of FACS solution, and a secondary antibody (F(ab’)

2 Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L), polyclonal, Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA; lot 1923631) was added at a dilution of 1:200. The incubation was carried out on ice, in the dark, for 30 minutes. After incubation, the cells were washed twice with FACS solution. Until analysis, cells were suspended in 500 µl of 4% formaldehyde solution.

3. Results

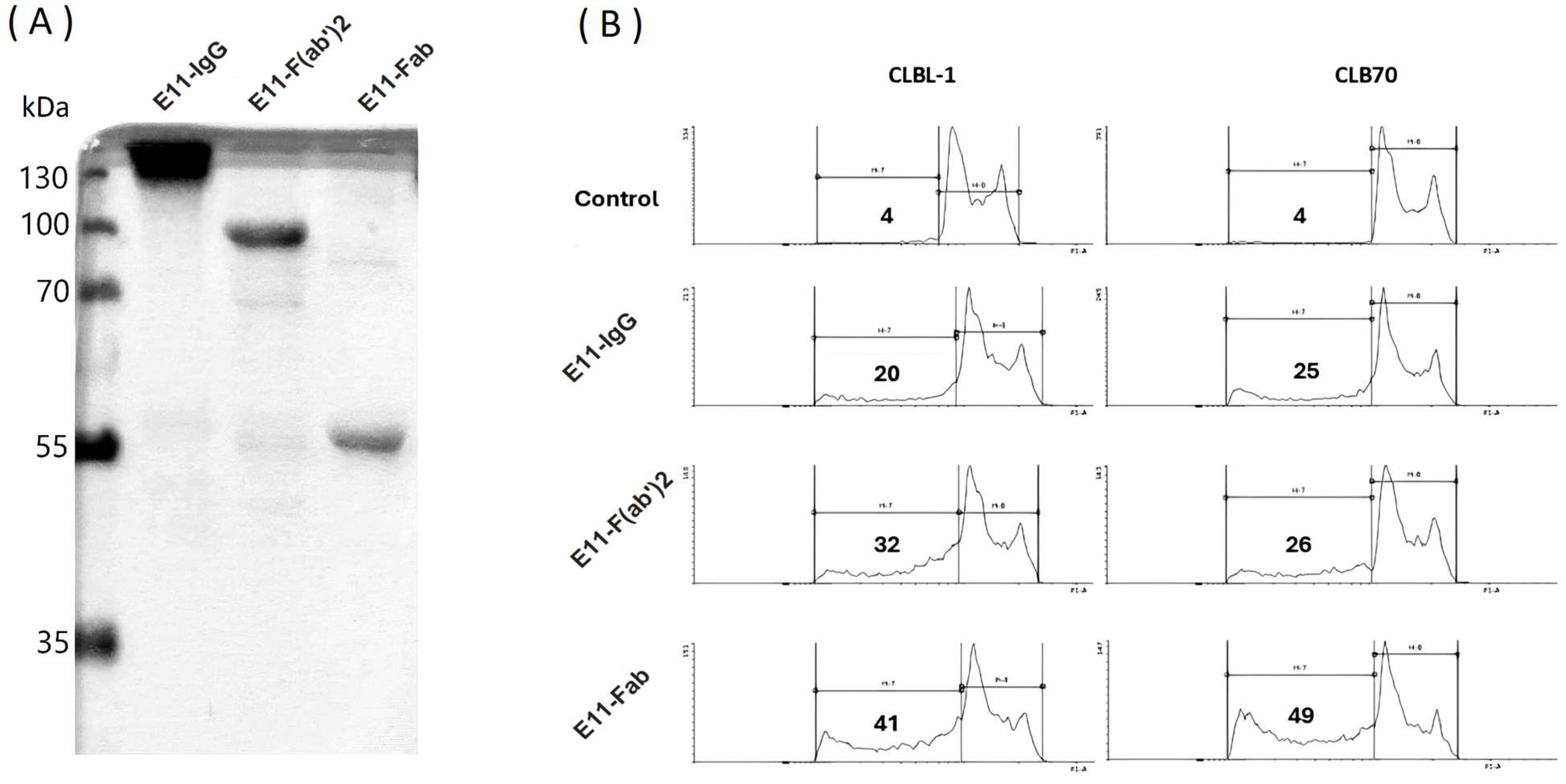

To evaluate the purity and biological activity of E11 antibody fragments, we first conducted sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Analysis of preparations designated for in vitro and in vivo studies (

Figure 1A) confirmed that the antibody preparations migrated at their expected apparent molecular weights. Only trace amounts of contaminating degradation products were detected, indicating a high level of purity. To assess the biological activity of the E11 antibody fragments, their cytotoxicity was compared to that of the full E11 monoclonal antibody (mAb) using a sub-G1 assay. This assay measured cell death in canine lymphoid tumor cell lines CLBL1 and CLB70 (

Figure 1B). At a concentration of 10 μg/mL, the E11-Fab, E11-F(ab)

2 fragments, and the full E11 mAb induced cell death in over 40%, 30%, and 20% of the cells, respectively, within 48 hours. These findings demonstrate that the fragmentation of the E11 mAb effectively preserves its cytotoxic activity in vitro. The observed increase in cytotoxicity for the fragments compared to the full mAb is likely due to the higher molar amounts of antigen-binding sites present in the fragmented preparations at the same mass concentration.

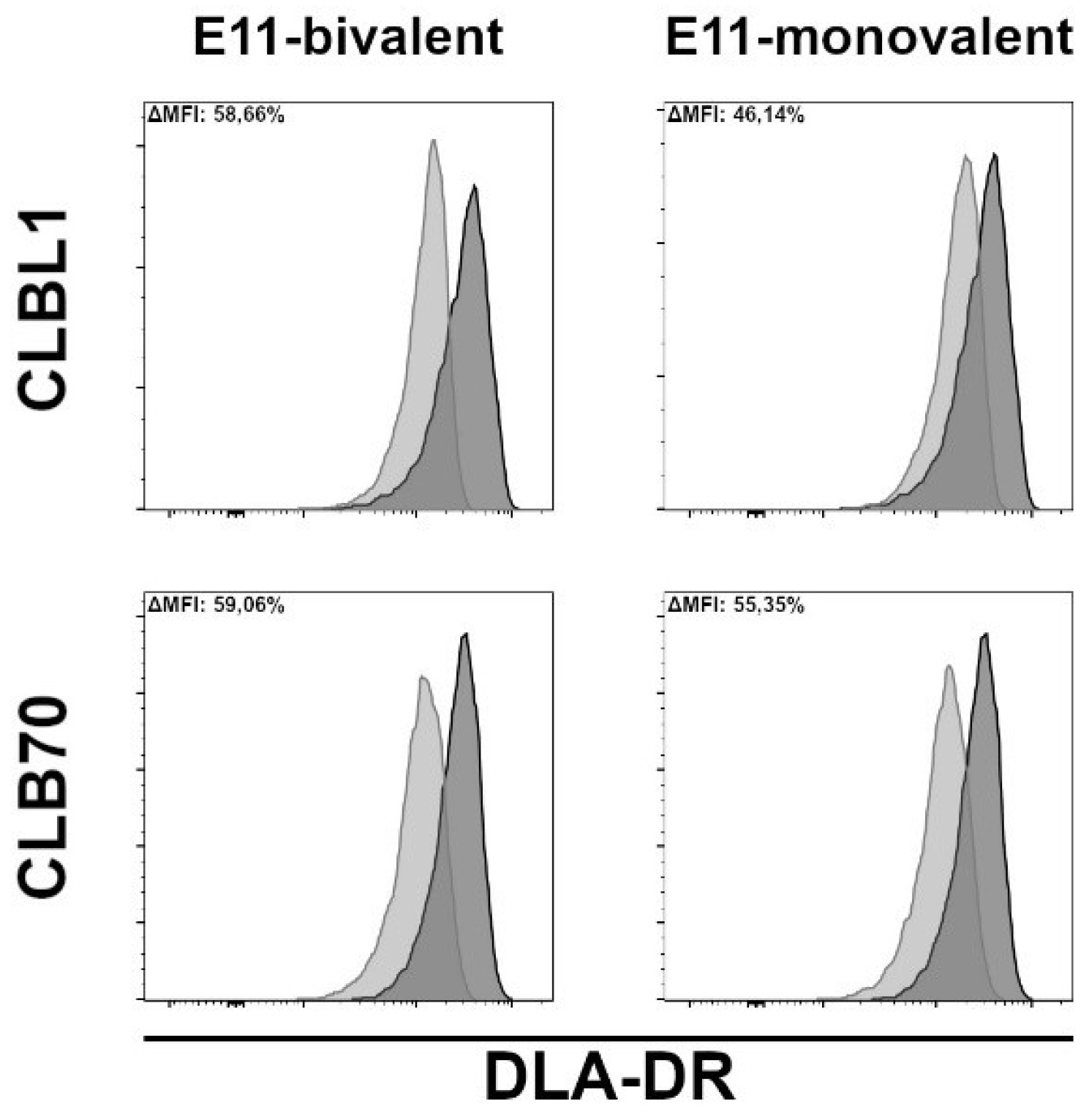

One prerequisite for MHC II-induced cell death is that antibodies must be able to downregulate MHC II DR expression upon binding their cognate epitope, as demonstrated by Vidović et al. (1995) [

30]. As shown in

Figure 2, both bivalent and monovalent engagement of DLA-DR by the E11 antibodies resulted in a marked downmodulation of DLA-DR cell surface expression levels after four hours of incubation. The monovalent E11 binding, however, consistently induced slightly lower DLA-DR downregulation.

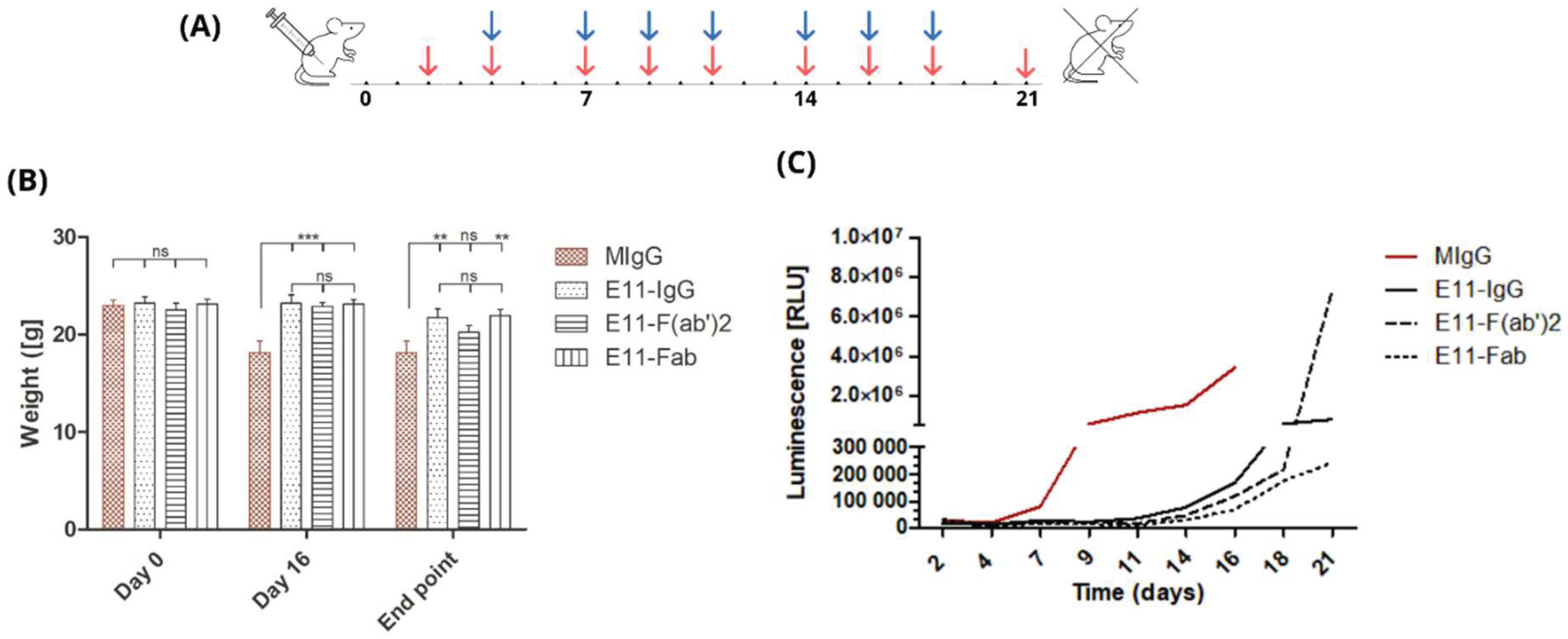

To assess the in vivo efficacy in killing tumor cells, we infused E11-mAb and its fragments into NOD-SCID mice previously implanted with the CLBL1-sLuc, a canine B cell lymphoma cell line genetically modified to secrete nanoluciferase. The experiment was designed to span three weeks following the implantation of tumor cells (

Figure 3A). During this period, disease progression was monitored through regular body weight measurements and blood luminescence readings.

To standardize the results, weight change readings were compared at three selected time points: day 0 (baseline), day 16 (at the time of experiment conclusion for the control groups), and day 21 (termination of the experiment for all mice) (

Figure 3B). At the outset of the experiment, mice were assigned to groups to minimize differences in average initial body weights.

In the control group, which received irrelevant, isotype-matched mouse immunoglobulin (MIgG), a significant deterioration in clinical condition was observed approximately 16 days post CLBL1-sLuc transplantation. Notable symptoms, including substantial weight loss (approximately 15-20%), prompted the early euthanasia of these animals. Experimental groups, euthanized according to the planned schedule, 5 days after the control group, also exhibited significant weight loss by the end of the experiment. Mice treated with full E11 mAb experienced an average weight loss of 7.01%, while mice in the E11-Fab group showed a reduction of 4.78%. The greatest weight loss was observed in the E11-F(ab’)2 group, with a decrease of 12.02%.

Monitoring luminescence levels in peripheral blood over time (

Figure 3C) allows for the minimally invasive assessment of lymphoma progression dynamics in vivo as the level of luciferase activity directly correlates with tumor cell burden. The initial luminescence measurements taken on day 2 post CLBL1-sLuc implantation showed a homogenous background luciferase activity in all transplanted animals with no statistically significant differences between the groups (Supplementary

Table 1). Based on the luminescence level changes over time, as shown in

Figure 3C, we observed that in the irrelevant MIgG-treated group, the rise in the luminescence was observed as early as on day seven post CLBL1-sLuc implantation whereas in E11 treated groups, similar increase in the luminescence appeared on average around day fifteen and peaked within next 4-5 days (

Figure 3C).

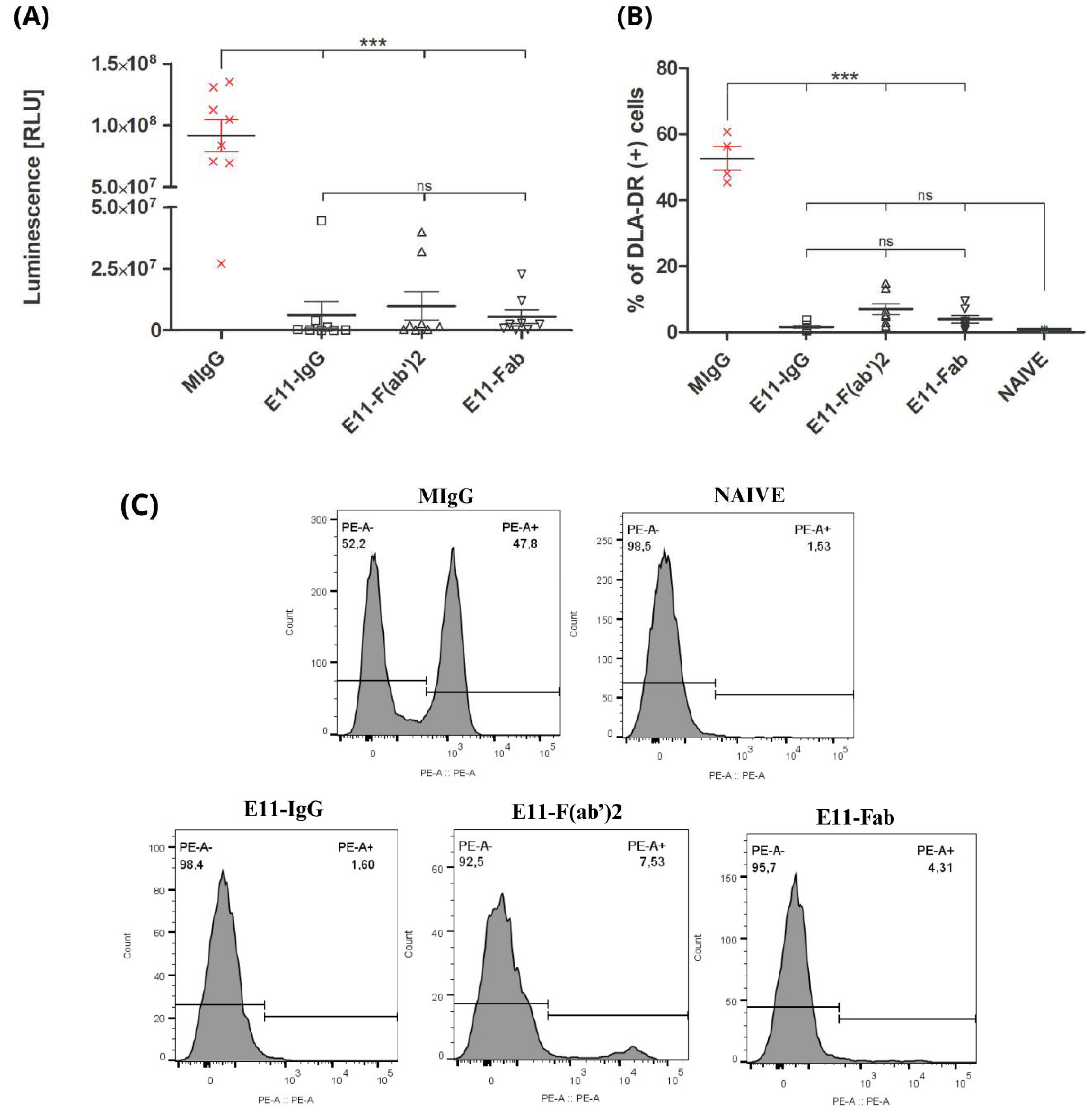

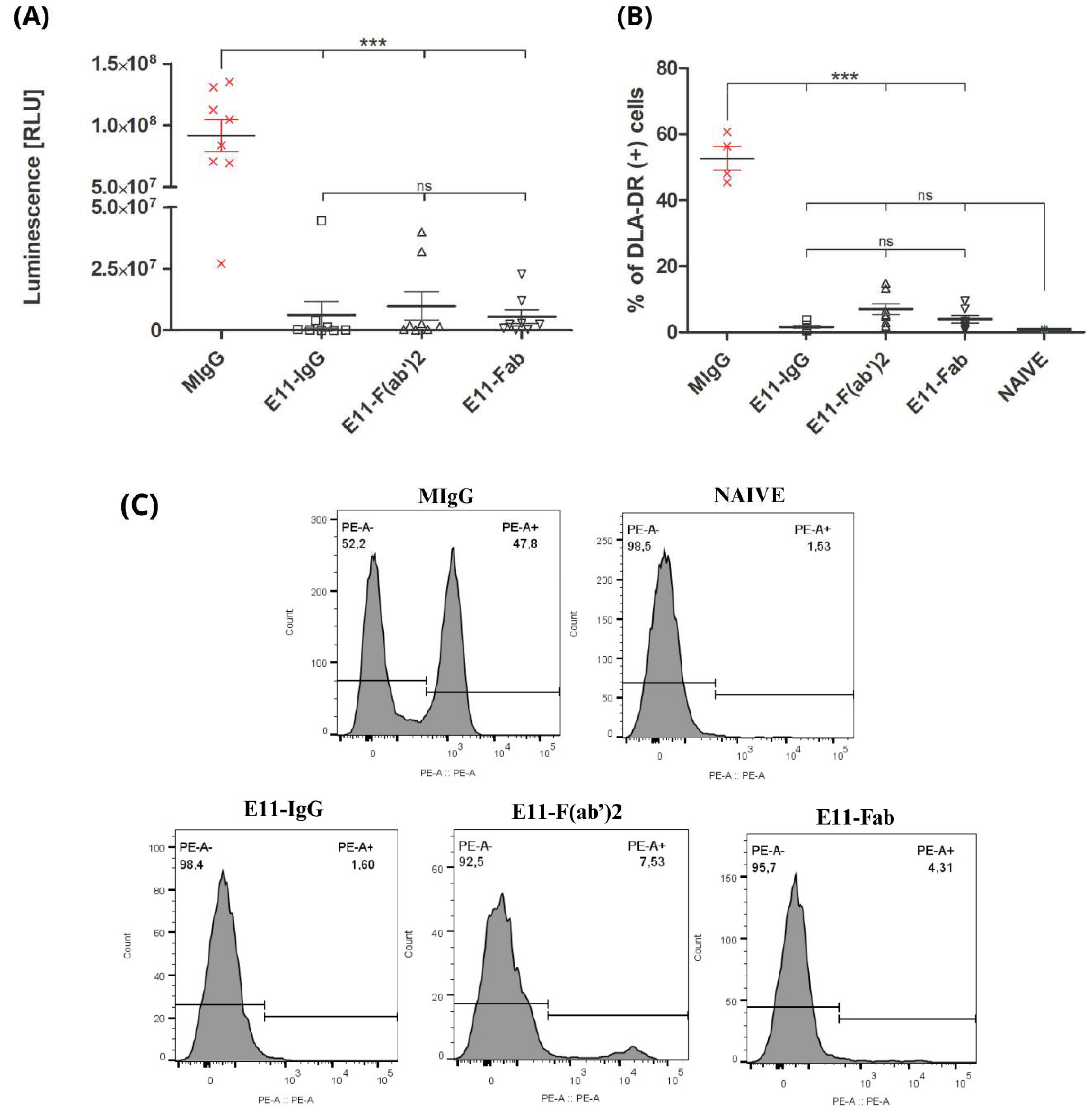

The osteotropic potential of the CLBL1-Luc cell line was previously established by its consistent formation of metastatic bone foci in NOD-SCID mice [

22]. We assessed the therapeutic efficacy of E11 antibody preparations by quantifying tumor spread in the bone marrow of treated mice, using both luciferase activity and CLBL1-sLuc cell counts. The control group, treated with an irrelevant mouse immunoglobulin (MIgG), showed the highest luminescence signal. All E11 antibody treatments significantly reduced luminescence levels (p<0.001), despite a 5-day delay in treatment initiation. The E11-Fab fragment group showed the most profound effect, with the lowest luminescence signal overall. The full E11 mAb and E11-F(ab’)

2 fragments reduced luminescence by approximately 15-fold and 9-fold, respectively, compared to the control, with no significant difference between them. Flow cytometric analysis, using the DLA-DR specific mAb (B5) for canine tumor cells, confirmed these findings. All E11 antibody variants significantly reduced the CLBL1 tumor cell burden in the bone marrow relative to the MIgG control (

Figure 3B and 3C).

Figure 4.

(A) Post-mortem luminescence measurements of bone marrow. Luminescence was measured in bone marrow homogenates and is expressed in relative light units (RLU). Group sizes: MIgG n = 8, E11-IgG n = 8 E11-F(ab’)2 n = 8, E11-Fab n = 8. (B) Quantification of DLA-DR-positive cells in the bone marrow cell fraction. The DLA-DR antigen is expressed on the surface of CLBL1 and CLBL1-sLuc cells, but is absent from murine cells. Naive (non-inoculated) mice show a background-level DLA-DR signal in flow cytometry analysis. Group sizes: MIgG n = 4, E11-IgG n = 8, E11-F(ab’)2 n = 8, E11-Fab n = 8, Naive n = 2. (C) Representative histograms depicting flow cytometry analysis of bone marrow cell isolates. Detection of engrafted CLBL1 lymphoma cells was based on the expression of canine major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II; DLA-DR), using the primary monoclonal antibody B5 (anti-DLA-DR), followed by a PE-conjugated secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse IgG). The PE-A+ population corresponds to DLA-DR-positive (CLBL1: DLA-DR+) cells. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Individual data points represent results from individual mice. Statistical significance: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, ns = not significant.

Figure 4.

(A) Post-mortem luminescence measurements of bone marrow. Luminescence was measured in bone marrow homogenates and is expressed in relative light units (RLU). Group sizes: MIgG n = 8, E11-IgG n = 8 E11-F(ab’)2 n = 8, E11-Fab n = 8. (B) Quantification of DLA-DR-positive cells in the bone marrow cell fraction. The DLA-DR antigen is expressed on the surface of CLBL1 and CLBL1-sLuc cells, but is absent from murine cells. Naive (non-inoculated) mice show a background-level DLA-DR signal in flow cytometry analysis. Group sizes: MIgG n = 4, E11-IgG n = 8, E11-F(ab’)2 n = 8, E11-Fab n = 8, Naive n = 2. (C) Representative histograms depicting flow cytometry analysis of bone marrow cell isolates. Detection of engrafted CLBL1 lymphoma cells was based on the expression of canine major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II; DLA-DR), using the primary monoclonal antibody B5 (anti-DLA-DR), followed by a PE-conjugated secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse IgG). The PE-A+ population corresponds to DLA-DR-positive (CLBL1: DLA-DR+) cells. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Individual data points represent results from individual mice. Statistical significance: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, ns = not significant.

In

Table 1, we summarised the experimental outcomes presented above. Data indicate that the full E11-mAb and its fragments significantly increased the proportion of tumor progression-free mice at day 21 (%PR = 50%) compared to the MIgG control group (12%). Time to tumor progression (TTP), assessed based on body weight loss, luminescence increase, and integrated composite indicators, was significantly prolonged in the treated groups relative to controls (p < 0.001). The control group exhibited a TTP range of 9.8–12.3 days, whereas mice receiving E11 antibody variants showed extended TTP values around 18–20 days.

These findings indicate the in vivo intrinsic cytotoxic potency of E11 antibody fragments towards the canine lymphoma cell line CLBL1-sLuc.

4. Discussion

We have previously reported on the development of two murine antibodies to dog leukocyte antigen DR (DLA-DR) that exhibit both direct and immune-mediated cytotoxicity against canine lymphoma and leukemia cell lines in vitro and in vivo [

22,

23]. Several other murine and human monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) targeting MHC Class II (MHC II) have also been shown to exert direct cytotoxic effects against B cell neoplasms or activated B cells [

31,

32,

33].

It has been widely accepted that crosslinking of MHC II with full-length antibodies is generally necessary to elicit efficient cell death. Consistent with this, certain bivalent F(ab’)

2 fragments, although sometimes less potent, have demonstrated cytotoxicity, whereas monovalent Fab fragments have consistently failed to induce cell death, even at high concentrations or following extended co-culture times [

30,

34]. Furthermore, as demonstrated by Gross and co-workers, a proper spatial orientation of dimerized MHC II was considered essential for apoptotic signaling, as homotypic aggregation of human leukocyte antigen DR HLA-DRα chains by an antibody L243 induced apoptosis in monocyte cell lines, while heterotypic aggregation of HLA-DRαand DRβ chains by staphylococcal enterotoxin A (SEA) did not [

35].

In the present report, we demonstrate for the first time that monovalent binding of the E11-Fab fragment to canine CLBL1 and CLB70 cells can induce direct cell death (

Figure 1B). The cytotoxic activity of the monovalent E11-Fab fragment is highly unusual. We were able to identify only one other published example of a monovalent interaction with MHC II inducing a direct cell death: the T-cell Receptor (TCR) binding to MHC II expressed on naive B cells by some Th0 cell clones [

36].

We hypothesize that the E11-Fab fragment, which recognizes a unique conformational epitope formed by both DLA-DRα and DLA-DRβ chains [

22], elicits intracellular signaling events comparable in their downstream effects to those of the aforementioned TCR engagement.

This in vitro observation is strongly supported by an in vivo mouse model that confirmed the potent therapeutic activity of the monovalent E11-Fab fragment. We observed significant suppression of both tumor growth and bone marrow metastasis (

Figure 3). Intriguingly, the E11-Fab activity was comparable to the full E11 mAb - even though the full antibody (IgG2a) is capable of activating Fc-dependent immune mechanisms - and to the bivalent F(ab’)

2 fragment, which can still crosslink MHC II molecules. This result strongly suggests that the crosslinking of MHC II by E11 is not critically important for its direct cytotoxic function.

As reported by Vidović et al., the majority of cytotoxic mAbs directed MHC II also possess the capacity to induce the downregulation of DR molecules from the cell surface of antigen-presenting cells (APCs). This downmodulating capacity is observed for both full antibodies and their monovalent fragments and is generally dependent on the antibody’s binding epitope on MHC II. It has been proposed that cytotoxic anti-MHC II mAbs often target the first, N-terminal, peptide-binding domain of MHC II DR molecules, although not all antibodies binding this region are downmodulating [

30].

The binding of E11 mAb to CLBL1 and CLB70 cells is accompanied by a downmodulation of approximately 50% of the initial cell surface expression of MHC II within 4 hours of incubation (

Figure 2). Prolonged 12-hour incubation does not significantly alter these initial values (data not shown). This level of MHC II downmodulation was significantly lower than that induced by the L243 Fab on EBV-LCL cells (~80%) [

30] and by an anti-DLA-DRα Fab B5 on CLBL1 cells (~75%) (Moniakowski, L. and Miazek, A., manuscript in preparation).

These comparative results suggest that the degree of MHC II downmodulation may be directly related to the specific MHC II epitope engaged by the anti-MHC II antibody. For E11 mAb, the conformational epitope requires co-expression of both DLA-DRα and DLA-DRβ chains, whereas the binding sites of L243 and B5 mAbs are within the DRα chain [

22,

37].

The intermediate level of DR downregulation induced by E11 mAb may be regarded as a favorable feature for potential clinical veterinary use. Since MHC II downmodulation on the surface of APCs inhibits antigen presentation and subsequent T-cell activation, the use of anti-MHC II antibodies to kill B-cell neoplasms carries a risk of adverse effects related to the loss or transient depletion of normal APC function—a kind of “double-edged sword” effect. Published data confirm a transient depletion of peripheral blood HLA-DR-positive APCs following infusion of human anti-MHC II agents like 1D09C and IMMU-114 [

33,

38]. In this context, the E11-Fab fragment’s lower propensity for downmodulation could better preserve MHC II expression on APCs following infusion and thereby limit systemic immune suppression.

5. Conclusions

In this report, we demonstrated for the first time that monovalent binding of the E11-Fab fragment to DLA-DR can cause direct cell death of the canine lymphoma cell line CLBL1 in vitro and can effectively suppress tumor growth in vivo.

Previously, the crosslinking of MHC II molecules by bivalent antibodies or F(ab’)2 fragments was generally considered a prerequisite for inducing death signaling in cancerous B cells. Our observation challenges this paradigm and strongly points to the existence of unique conformational epitopes on the DLA-DR heterodimer. The engagement of this specific epitope by a monovalent antibody fragment is sufficient to trigger cell death signaling, functionally analogous to the pathway elicited by TCR-MHC II interactions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M. and A.R.; methodology, A.M., A.S., M.P., A.U., A.K., A.R.; resources, A.M., A.R.; data curation, L.M., M.P., A.K., A.U. writing—original draft preparation, A.M., A.S.; writing—review and editing, A.M., A.S., M.P..; visualization, L.M. M.P.; supervision, A.M.; funding acquisition, A.M., A.R., All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Center for Research and Development (NCBiR), project number POIR.04.01.04-00-0025/20. The APC/BPC is financed by Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Local Ethics Committee in Wroclaw (Poland) for studies involving animals, protocol code 040/2023/P1 from 21.06.2023.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets from the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| APCs |

Antigen presenting cells |

| cDLBL |

Canine diffuse large B cell lymphoma |

| DLA-DR |

Dog leukocyte antigen DR |

| HLA DR |

Human Leukocyte antigen DR |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

| MHC II |

Major histocompatibility complex class II |

| SEA |

Staphylococcal Enterotoxin A |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| TTP |

Tıme to tumor progression |

References

- Schneider R. Comparison of age- and sex-specific incidence rate patterns of the leukemia complex in the cat and the dog. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1983, 70(5), 971-7. [CrossRef]

- Comazzi, S.; Marelli, S.; Cozzi, M.; Rizzi, R.; Finotello, R.; Henriques, J.; Pastor, J.; Ponce, F.; Rohrer-Bley, C.; Rütgen, B.C.; Teske, E. Breed-associated risks for developing canine lymphoma differ among countries: an European canine lymphoma network study. BMC Vet. Res. 2018, 6;14(1), 232. [CrossRef]

- Merlo, D.F.; Rossi, L.; Pellegrino, C.; Ceppi, M.; Cardellino, U.; Capurro, C.; Ratto, A.; Sambucco, P.L.; Sestito, V.; Tanara, G.; Bocchini, V. Cancer incidence in pet dogs: findings of the Animal Tumor Registry of Genoa, Italy. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2008, 22, 976–984. [CrossRef]

- Vezzali, E.; Parodi, A. L.; Marcato, P. S.; Bettini, G. Histopathologic classification of 171 cases of canine and feline non-Hodgkin lymphoma according to the WHO. Vet. Comp. Oncol. 2010, 8(1), 38-49. [CrossRef]

- Wilkerson, M.J.; Dolce, K.l.; Koopman, T.; Shuman, W.; Chun, R.; Garrett, L.; Barber, L.; Avery, A. Lineage differentiation of canine lymphoma/leukemias and aberrant expression of CD molecules. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2005, 15;106(3-4), 179-96. [CrossRef]

- Rocha, M.D.C.P.; Araújo, D.; Carvalho, F.; Vale, N.; Pazzini, J.M.; Feliciano, M.A.R.; De Nardi, A.B.; Amorim, I. Canine Multicentric Lymphoma: Diagnostic, Treatment, and Prognostic Insights. Animals (Basel) 2025, 30;15(3), 391. [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, F.R.; Sale, G.E.; Storb, R.; Charrier, K.; Deeg, H.J.; Graham, T.; Wulff, J.C. Phenotyping of canine lymphoma with monoclonal antibodies directed at cell surface antigens: classification, morphology, clinical presentation and response to chemotherapy. Hematol. Oncol. 1984, 2(2), 151-68. [CrossRef]

- Richards, K.L.; Suter, S.E. Man’s best friend: what can pet dogs teach us about non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma? Immunol. Rev. 2015, 263(1), 173-91. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.E.; Cameron, T.P.; Kinard, R. Canine lymphoma as a potential model for experimental therapeutics. Cancer Res. 1968, 28(12), 2562-4.

- Ito, D.; Frantz, A.M.; Modiano, J.F. Canine lymphoma as a comparative model for human non-Hodgkin lymphoma: recent progress and applications. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2014, 15;159(3-4), 192-201. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, P.; Williamson, P.; Taylor, R. Review of Canine Lymphoma Treated with Chemotherapy - Outcomes and Prognostic Factors. Vet Sci. 2023, 11;10(5), 342. [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, T.; Kato, Y.; Kaneko, M.K.; Sakai, Y.; Shiga, T.; Kato, M.; Tsukui, T.; Takemoto, H.; Tokimasa, A.; Baba, K.; Nemoto, Y.; Sakai, O.; Igase, M. Generation of a canine anti-canine CD20 antibody for canine lymphoma treatment. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10;10(1), 11476. [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, V.S.; Thamm, D.H.; Kurzman, I.D.; Turek, M.M.; Vail, D.M. Does L-asparaginase influence efficacy or toxicity when added to a standard CHOP protocol for dogs with lymphoma? J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2005, 19(5), 732-6.

- Hanif, N,; Anwer, F. Rituximab. 2024 Feb 28. In: StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/books/NBK564374/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Rue, S.M.; Eckelman, B.P.; Efe, J.A.; Bloink, K.; Deveraux, Q.L.; Lowery, D.; Nasoff, M. Identification of a candidate therapeutic antibody for treatment of canine B-cell lymphoma. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2015, 15;164(3-4), 148-59. [CrossRef]

- Salles, G.; Barrett, M.; Foà, R.; Maurer, J.; O’Brien, S.; Valente, N.; Wenger, M.; Maloney, D.G. Rituximab in B-Cell Hematologic Malignancies: A Review of 20 Years of Clinical Experience. Adv. Ther. 2017, 34(10), 2232-2273. [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, T.; Kato, Y.; Kaneko, M.K.; Sakai, Y.; Shiga, T.; Kato, M.; Tsukui, T.; Takemoto, H.; Tokimasa, A.; Baba, K.; Nemoto, Y.; Sakai, O.; Igase, M. Generation of a canine anti-canine CD20 antibody for canine lymphoma treatment. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10;10(1), 11476. [CrossRef]

- Impellizeri, J.A.; Howell, K.; McKeever, K.P.; Crow, S.E. The role of rituximab in the treatment of canine lymphoma: an ex vivo evaluation. Vet. J. 2006, 171(3), 556-8. [CrossRef]

- McLinden, G.P.; Avery, A.C.; Gardner, H.L.; Hughes, K.; Rodday, A.M.; Liang, K.; London, C.A. Safety and biologic activity of a canine anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody in dogs with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2024, 38(3), 1666-1674.

- Stein, R.; Gupta, P.; Chen, X.; Cardillo, T.M.; Furman, R.R.; Chen, S.; Chang, C.H.; Goldenberg, D.M. Therapy of B-cell malignancies by anti-HLA-DR humanized monoclonal antibody, IMMU-114, is mediated through hyperactivation of ERK and JNK MAP kinase signaling pathways. Blood 2010, 24;115(25), 5180-90.

- Tay, R.E.; Richardson, E.K.; Toh, H.C. Revisiting the role of CD4+ T cells in cancer immunotherapy—new insights into old paradigms. Cancer Gene Ther. 2021, 28(1-2), 5-17. [CrossRef]

- Lisowska, M.; Pawlak, A.; Kutkowska, J.; Hildebrand, W.; Ugorski, M.; Rapak, A.; Miazek, A. Development of novel monoclonal antibodies to dog leukocyte antigen DR displaying direct and immune-mediated cytotoxicity toward canine lymphoma cell lines. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Lisowska, M.; Milczarek, M.; Ciekot, J.; Kutkowska, J.; Hildebrand, W.; Rapak, A.; Miazek, A. An Antibody Specific for the Dog Leukocyte Antigen DR (DLA-DR) and Its Novel Methotrexate Conjugate Inhibit the Growth of Canine B Cell Lymphoma. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 26;11(10), 1438. [CrossRef]

- Xenaki, K.T.; Oliveira, S.; van Bergen En Henegouwen, P.M.P. Antibody or Antibody Fragments: Implications for Molecular Imaging and Targeted Therapy of Solid Tumors. Front. Immunol. 2017, 12;8, 1287. [CrossRef]

- Sanz, L.; Cuesta, A.M.; Compte, M.; Alvarez-Vallina, L. Antibody engineering: facing new challenges in cancer therapy. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2005, 26(6), 641-8. [CrossRef]

- Miao, M.; Masengere, H.; Yu, G.; Shan, F. Reevaluation of NOD/SCID Mice as NK Cell-Deficient Models. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021, 10;2021, 8851986. [CrossRef]

- Jessen, S.B.; Özkul, D.C.; Özen, Y.; Gögenur, I.; Troelsen, J.T. Establishment of a luciferase-based method for measuring cancer cell adhesion and proliferation. Anal. Biochem. 2022 1;650, 114723. [CrossRef]

- Holson, R.R. Euthanasia by decapitation: evidence that this technique produces prompt, painless unconsciousness in laboratory rodents. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1992, 14(4), 253-7. [CrossRef]

- Underwood W, Leary S, Anthony R, Cartner S, Corey D, Grandin T, et al. AVMA guidelines for the euthanasia of animals: 2013 edition. Schaumburg (IL): American Veterinary Medical Association 2013. Available online: https://www.avma.org/resources-tools/avma-policies/avma-guidelines-euthanasia-animals (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Vidović, d.; Falcioni, F.; Siklodi, B.; Belunis, C.J.; Bolin, D.R.; Ito, K.; Nagy, Z.A. Down-regulation of class II major histocompatibility complex molecules on antigen-presenting cells by antibody fragments. Eur. J. Immunol. 1995, 25(12), 3349-3355 . [CrossRef]

- Bridges, S.H.; Kruisbeek, A.M.; Longo, D.L. Selective in vivo antitumor effects of monoclonal anti-I-A antibody on B cell lymphoma. J. Immunol. 1987, 139(12), 4242-4249 . [CrossRef]

- Vidović, D.; Toral, J.I. Selective apoptosis of neoplastic cells by the HLA-DR-specific monoclonal antibody. Cancer Lett. 1998, 128(2), 127-135 . [CrossRef]

- Nagy, Z.A.; Hubner, B.; Löhning, C.; Rauchenberger, R.; Reiffert, S.; Thomassen-Wolf, E.; Zahn, S.; Leyer, S.; Schier, E.M.; Zahradnik, A.; Brunner, C.; Lobenwein, K.; Rattel, B.; Stanglmaier, M.; Hallek, M.; Wing, M.; Anderson, S.; Dunn, M.; Kretzschmar, T.; Tesar, M. Fully human, HLA-DR-specific monoclonal antibodies efficiently induce programmed death of malignant lymphoid cells. Nat. Med. 2002, 8(8), 801-807. [CrossRef]

- Nagy, Z.A.; Mooney, N.A. A novel, alternative pathway of apoptosis triggered through class II major histocompatibility complex molecules. J. Mol. Med. 2003, 81, 757-765. [CrossRef]

- Gross, U.; Schroder, A.K.; Haylett, R.S.; Arlt, S.; Rink, L. The superantigen staphylococcal enterotoxin A (SEA) and monoclonal antibody L243 share a common epitope but differ in their ability to induce apoptosis via MHC-II. Immunobiol. 2006, 211, 807-814. [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhong, W.; Goronzy, J.J.; Weyand, C.M. Induction of B cell apoptosis by TH0, but not TH2, CD4+ T cells. J. Clin. Invest. 1995, 95, 564-570. [CrossRef]

- Dowd, J.E.; Karr, R.W.; Karp, D.R. Functional activity of staphylococcal enterotoxin a requires interactions with both the alpha and beta chains of HLA-DR. Mol. Immunol 1996, 33(16), 127-132. [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.D.; Bullock, C.; Hall, W.C.; Wescott, V.; Wang, H.; Levitt, D.J.; Klingbeil, C.K. In Vivo Pharmacodynamic Effects of Hu1D10 (Remitogen), a Humanized Antibody Reactive Against a Polymorphic Determinant of HLA-DR Expressed on B Cells. Leuk. Lymphoma 2002, 43(6), 1303-1312. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).