Submitted:

08 July 2024

Posted:

09 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Dualistic Nature of the Genus Acinetobacter

3. Virulence and Pathogenicity Genetic Determinants

3.1. Antibiotic Resistance Genes

3.2. Error-Prone DNA Polymerases

3.3. Biofilm Formation

3.4. Other Outer Membrane Proteins

3.5. Toxins Secretion

3.6. Siderophores

4. Acinetobacter in the Environment

4.1. Soil

4.2. Waters

4.3. Acinetobacter as an Animal Skin Commensal

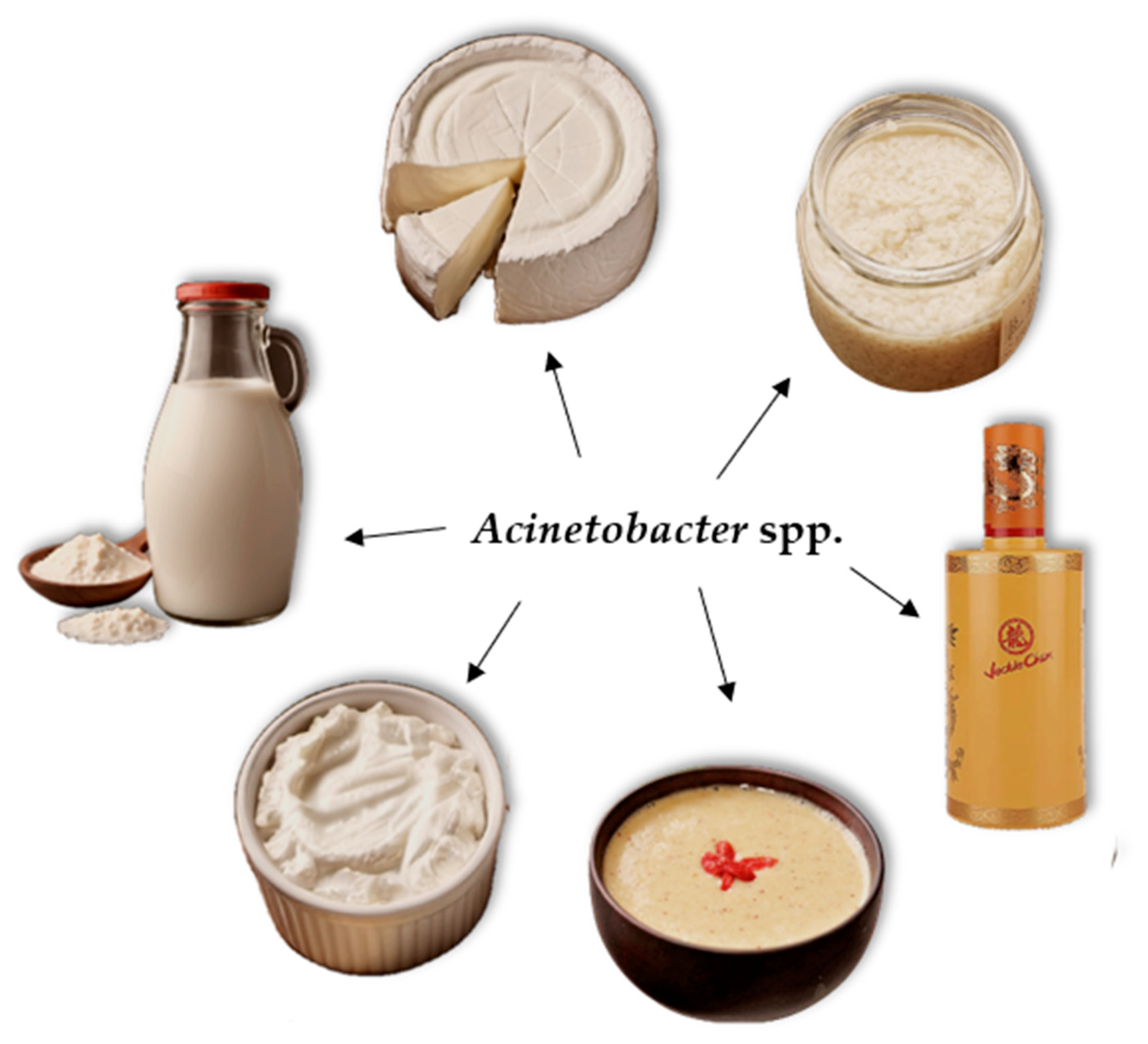

5. Acinetobacter in Fermented Foods

5.1. Presence in Fermented Non-Dairy Foods

5.2. Presence in Fermented Dairy Foods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Yang, X. Moraxellaceae. Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology 2014, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalheira, A.; Casquete, R.; Silva, J.; Teixeira, P. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Acinetobacter spp. isolated from meat. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2017, 243, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veress, A.; Nagy, T.; Wilk, T.; Kömüves, J.; Olasz, F.; Kiss, J. Abundance of mobile genetic elements in an Acinetobacter lwoffii strain isolated from Transylvanian honey sample. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valizade, K.M.; Rezazad, B.M.; Mehrnoosh, F.; Alizade, K.A.M. A research on existence and special activities of Acinetobacter in different cheese. 2014.

- Kim, P.S.; Shin, N.-R.; Kim, J.Y.; Yun, J.-H.; Hyun, D.-W.; Bae, J.-W. Acinetobacter apis sp. nov., isolated from the intestinal tract of a honey bee, Apis mellifera. Journal of microbiology 2014, 52, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamouda, A.; Findlay, J.; Al Hassan, L.; Amyes, S.G.B. Epidemiology of Acinetobacter baumannii of animal origin. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 2011, 38, 314–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-El-Haleem, D. Acinetobacter: environmental and biotechnological applications. African journal of Biotechnology 2003, 2, 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Abd-El-Haleem, D.; Beshay, U.; Abdelhamid, A.O.; Moawad, H.; Zaki, S. Effects of mixed nitrogen sources on biodegradation of phenol by immobilized Acinetobacter sp. strain W-17. African Journal of Biotechnology 2003, 2, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Amorim, A.M.B.d.; Nascimento, J.d.S. Acinetobacter: an underrated foodborne pathogen? The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries 2017, 11, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visca, P.; Seifert, H.; Towner, K.J. Acinetobacter infection – an emerging threat to human health. IUBMB Life 2011, 63, 1048–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, G.M.; Peleg, A.Y. Insights into Acinetobacter baumannii pathogenicity. IUBMB Life 2011, 63, 1055–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirel, L.; Bonnin, R.A.; Nordmann, P. Genetic basis of antibiotic resistance in pathogenic Acinetobacter species. IUBMB life 2011, 63, 1061–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Sun, D. Detection of NDM-1 carbapenemase-producing Acinetobacter calcoaceticus and Acinetobacter junii in environmental samples from livestock farms. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2014, 70, 611–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, W.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, T.; Ding, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Zeng, Z. Antibiotics, Antibiotic Resistance Genes, and Bacterial Community Composition in Fresh Water Aquaculture Environment in China. Microbial Ecology 2015, 70, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ababneh, Q.; Al-Rousan, E.; Jaradat, Z. Fresh produce as a potential vehicle for transmission of Acinetobacter baumannii. International Journal of Food Contamination 2022, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sablé, S.; Portrait, V.; Gautier, V.; Letellier, F.; Cottenceau, G. Microbiological changes in a soft raw goat’s milk cheese during ripening. Enzyme and Microbial Technology 1997, 21, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coton, M.; Delbés-Paus, C.; Irlinger, F.; Desmasures, N.; Le Fleche, A.; Stahl, V.; Montel, M.-C.; Coton, E. Diversity and assessment of potential risk factors of Gram-negative isolates associated with French cheeses. Food Microbiology 2012, 29, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alessandria, V.; Ferrocino, I.; Filippis, F.D.; Fontana, M.; Rantsiou, K.; Ercolini, D.; Cocolin, L. Microbiota of an Italian Grana-Like Cheese during Manufacture and Ripening, Unraveled by 16S rRNA-Based Approaches. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2016, 82, 3988–3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addis, E.; Fleet, G.H.; Cox, J.M.; Kolak, D.; Leung, T. The growth, properties and interactions of yeasts and bacteria associated with the maturation of Camembert and blue-veined cheeses. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2001, 69, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brisou, J.; Prevot, A.R. [Studies on bacterial taxonomy. X. The revision of species under Acromobacter group]. Ann Inst Pasteur (Paris) 1954, 86, 722–728. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Touchon, M.; Cury, J.; Yoon, E.J.; Krizova, L.; Cerqueira, G.C.; Murphy, C.; Feldgarden, M.; Wortman, J.; Clermont, D.; Lambert, T.; et al. The genomic diversification of the whole Acinetobacter genus: origins, mechanisms, and consequences. Genome Biol Evol 2014, 6, 2866–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genus Acinetobacter. LSPN - List of prokaryitic names with standing in nomenclature, Accesses on May 2024.

- Bergogne-Bérézin, E.; Towner, K.J. Acinetobacter spp. as nosocomial pathogens: microbiological, clinical, and epidemiological features. Clin Microbiol Rev 1996, 9, 148–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peleg, A.Y.; Seifert, H.; Paterson, D.L. Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev 2008, 21, 538–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemec, A.; Krizova, L.; Maixnerova, M.; van der Reijden, T.J.; Deschaght, P.; Passet, V.; Vaneechoutte, M.; Brisse, S.; Dijkshoorn, L. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-Acinetobacter baumannii complex with the proposal of Acinetobacter pittii sp. nov. (formerly Acinetobacter genomic species 3) and Acinetobacter nosocomialis sp. nov. (formerly Acinetobacter genomic species 13TU). Res Microbiol 2011, 162, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doughari, H.J.; Ndakidemi, P.A.; Human, I.S.; Benade, S. The ecology, biology and pathogenesis of Acinetobacter spp.: an overview. Microbes Environ 2011, 26, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glew, R.H.; Moellering, R.C., Jr.; Kunz, L.J. Infections with Acinetobacter calcoaceticus (Herellea vaginicola): clinical and laboratory studies. Medicine (Baltimore) 1977, 56, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grotiuz, G.; Sirok, A.; Gadea, P.; Varela, G.; Schelotto, F. Shiga Toxin 2-Producing Acinetobacter haemolyticus Associated with a Case of Bloody Diarrhea. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2006, 44, 3838–3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prashanth, K.; Badrinath, S. Nosocomial infections due to Acinetobacter species: clinical findings, risk and prognostic factors. Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology 2006, 24, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ku, S.C.; Hsueh, P.R.; Yang, P.C.; Luh, K.T. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of bacteremia caused by Acinetobacter lwoffii. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2000, 19, 501–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Zhang, S.; Guan, G.; Wan, Z.; Wang, R.; Li, P.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Jiao, G.; Wang, H. A specific and rapid method for detecting Bacillus and Acinetobacter species in Daqu. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2023, 11, 1261563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, Q.; Li, D.; Wu, X.; Li, P.; Zhou, Q.; Cai, W.; Zhang, J.; Du, G. Effects of inoculation with Acinetobacter on fermentation of cigar tobacco leaves. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13, 911791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wu, R.; Zhang, P.; Liu, Y.; Tao, D.; Yue, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Wu, J. Structure and diversity of bacterial communities in the fermentation of da-jiang. Annals of microbiology 2018, 68, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalheira, A.; Silva, J.; Teixeira, P. Acinetobacter spp. in food and drinking water – A review. Food Microbiology 2021, 95, 103675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Wintersdorff, C.J.; Penders, J.; van Niekerk, J.M.; Mills, N.D.; Majumder, S.; van Alphen, L.B.; Savelkoul, P.H.; Wolffs, P.F. Dissemination of Antimicrobial Resistance in Microbial Ecosystems through Horizontal Gene Transfer. Front Microbiol 2016, 7, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manchanda, V.; Sanchaita, S.; Singh, N. Multidrug resistant acinetobacter. J Glob Infect Dis 2010, 2, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partridge, S.R.; Kwong, S.M.; Firth, N.; Jensen, S.O. Mobile Genetic Elements Associated with Antimicrobial Resistance. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2018, 31, 10.1128/cmr.00088–00017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, M.; Shen, X.; Frank, E.G.; O’Donnell, M.; Woodgate, R.; Goodman, M.F. UmuD′2C is an error-prone DNA polymerase, Escherichia coli pol V. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1999, 96, 8919–8924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Pham, P.; Shen, X.; Taylor, J.-S.; O’Donnell, M.; Woodgate, R.; Goodman, M.F. Roles of E. coli DNA polymerases IV and V in lesion-targeted and untargeted SOS mutagenesis. Nature 2000, 404, 1014–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, M.A.; Grice, A.N.; Hare, J.M. A corepressor participates in LexA-independent regulation of error-prone polymerases in Acinetobacter. Microbiology 2020, 166, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candra, B.; Cook, D.; Hare, J. Repression of Acinetobacter baumannii DNA damage response requires DdrR-assisted binding of UmuDAb dimers to atypical SOS box. Journal of Bacteriology 2024, 206, e00432–00423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.; Flannigan, M.D.; Candra, B.V.; Compton, K.D.; Hare, J.M. The DdrR Coregulator of the Acinetobacter baumannii Mutagenic DNA Damage Response Potentiates UmuDAb Repression of Error-Prone Polymerases. Journal of Bacteriology 2022, 204, e00165–00122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedefie, A.; Demsis, W.; Ashagrie, M.; Kassa, Y.; Tesfaye, M.; Tilahun, M.; Bisetegn, H.; Sahle, Z. Acinetobacter baumannii biofilm formation and its role in disease pathogenesis: a review. Infection and drug resistance 2021, 3711–3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.H.; Tian, X. Quorum sensing and bacterial social interactions in biofilms. Sensors (Basel) 2012, 12, 2519–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Encinales, V.; Álvarez-Marín, R.; Pachón-Ibáñez, M.E.; Fernández-Cuenca, F.; Pascual, A.; Garnacho-Montero, J.; Martínez-Martínez, L.; Vila, J.; Tomás, M.M.; Cisneros, J.M. Overproduction of outer membrane protein A by Acinetobacter baumannii as a risk factor for nosocomial pneumonia, bacteremia, and mortality rate increase. The Journal of infectious diseases 2017, 215, 966–974. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smani, Y.; McConnell, M.J.; Pachón, J. Role of fibronectin in the adhesion of Acinetobacter baumannii to host cells. PloS one 2012, 7, e33073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, D.C.; Choi, C.H.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, C.-W.; Kim, H.-Y.; Park, J.S.; Kim, S.I.; Lee, J.C. Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein A modulates the biogenesis of outer membrane vesicles. The Journal of Microbiology 2012, 50, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rumbo, C.; Tomás, M.; Moreira, E.F.; Soares, N.C.; Carvajal, M.; Santillana, E.; Beceiro, A.; Romero, A.; Bou, G. The Acinetobacter baumannii Omp33-36 Porin Is a Virulence Factor That Induces Apoptosis and Modulates Autophagy in Human Cells. Infection and Immunity 2014, 82, 4666–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uppalapati, S.R.; Sett, A.; Pathania, R. The Outer Membrane Proteins OmpA, CarO, and OprD of Acinetobacter baumannii Confer a Two-Pronged Defense in Facilitating Its Success as a Potent Human Pathogen. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, A.C.; Sayood, K.; Olmsted, S.B.; Blanchard, C.E.; Hinrichs, S.; Russell, D.; Dunman, P.M. Characterization of the Acinetobacter baumannii growth phase-dependent and serum responsive transcriptomes. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2012, 64, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, B.S.; Kinsella, R.L.; Harding, C.M.; Feldman, M.F. The secrets of Acinetobacter secretion. Trends in microbiology 2017, 25, 532–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repizo, G.D.; Gagné, S.; Foucault-Grunenwald, M.-L.; Borges, V.; Charpentier, X.; Limansky, A.S.; Gomes, J.P.; Viale, A.M.; Salcedo, S.P. Differential Role of the T6SS in Acinetobacter baumannii Virulence. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0138265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troxell, B.; Hassan, H.M. Transcriptional regulation by Ferric Uptake Regulator (Fur) in pathogenic bacteria. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology 2013, 3, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miethke, M.; Marahiel, M.A. Siderophore-Based Iron Acquisition and Pathogen Control. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 2007, 71, 413–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, S.C.; Robinson, A.K.; Rodríguez-Quiñones, F. Bacterial iron homeostasis. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 2003, 27, 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Lu, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.; Yu, H.H.; Velkov, T.; Li, J. Complete genome sequence and genome-scale metabolic modelling of Acinetobacter baumannii type strain ATCC 19606. International Journal of Medical Microbiology 2020, 310, 151412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbe, V.; Vallenet, D.; Fonknechten, N.; Kreimeyer, A.; Oztas, S.; Labarre, L.; Cruveiller, S.; Robert, C.; Duprat, S.; Wincker, P.; et al. Unique features revealed by the genome sequence of Acinetobacter sp. ADP1, a versatile and naturally transformation competent bacterium. Nucleic Acids Research 2004, 32, 5766–5779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.-Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Huang, F.-M.; Chen, R.-C.; Xiao, Y.-H.; Zhou, K. Sporadic Dissemination of tet(X3) and tet(X6) Mediated by Highly Diverse Plasmidomes among Livestock-Associated Acinetobacter. Microbiology Spectrum 2021, 9, e01141–01121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiester, S.E.; Actis, L.A. Stress Responses in the Opportunistic Pathogen Acinetobacter Baumannii. Future Microbiology 2013, 8, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alyamani, E.J.; Khiyami, M.A.; Booq, R.Y. Acinetobacter baylyi Biofilm Formation Dependent Genes. Journal Of Pure And Applied Microbiology 2014, 8, 379–382. [Google Scholar]

- Cray, J.A.; Bell, A.N.; Bhaganna, P.; Mswaka, A.Y.; Timson, D.J.; Hallsworth, J.E. The biology of habitat dominance; can microbes behave as weeds? Microbial biotechnology 2013, 6, 453–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, P. Isolation of Acinetobacter from Soil and Water. Journal of Bacteriology 1968, 96, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percival, S.L.; Williams, D.W. Acinetobacter. In Microbiology of waterborne diseases, Elsevier: 2014; pp. 35-48.

- Metzgar, D.; Bacher, J.M.; Pezo, V.; Reader, J.; Döring, V.; Schimmel, P.; Marliere, P.; de Crecy-Lagard, V. Acinetobacter sp. ADP1: an ideal model organism for genetic analysis and genome engineering. Nucleic acids research 2004, 32, 5780–5790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, S.M.; Ahn, E.; Ahn, S.; Cho, S.; Ryu, S. Prevalence of antibiotic-resistant Acinetobacter spp. on soil and crops collected from agricultural fields in South Korea. Food Science and Biotechnology 2024, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogut, M.; Er, F.; Kandemir, N. Phosphate solubilization potentials of soil Acinetobacter strains. Biology and fertility of soils 2010, 46, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kour, D.; Kaur, T.; Devi, R.; Chaubey, K.K.; Yadav, A.N. Co-inoculation of nitrogen fixing and potassium solubilizing Acinetobacter sp. for growth promotion of onion (Allium cepa). Biologia 2023, 78, 2635–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Shah, S.B.; Zanaroli, G.; Xu, P.; Tang, H. Phenol biodegradation by Acinetobacter radioresistens APH1 and its application in soil bioremediation. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2020, 104, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karumathil, D.P.; Yin, H.-B.; Kollanoor-Johny, A.; Venkitanarayanan, K. Effect of Chlorine Exposure on the Survival and Antibiotic Gene Expression of Multidrug Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in Water. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2014, 11, 1844–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bifulco, J.M.; Shirey, J.J.; Bissonnette, G.K. Detection of Acinetobacter spp. in rural drinking water supplies. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 1989, 55, 2214–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umezawa, K.; Asai, S.; Ohshima, T.; Iwashita, H.; Ohashi, M.; Sasaki, M.; Kaneko, A.; Inokuchi, S.; Miyachi, H. Outbreak of drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii ST219 caused by oral care using tap water from contaminated hand hygiene sinks as a reservoir. American Journal of Infection Control 2015, 43, 1249–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narciso-da-Rocha, C.; Vaz-Moreira, I.; Svensson-Stadler, L.; Moore, E.R.B.; Manaia, C.M. Diversity and antibiotic resistance of Acinetobacter spp. in water from the source to the tap. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2013, 97, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Wang, R.; Rao, P.; Wu, B.; Yan, L.; Hu, L.; Park, S.; Ryu, M.; Zhou, X. Bioremediation of Petroleum Hydrocarbons Using Acinetobacter sp. SCYY-5 Isolated from Contaminated Oil Sludge: Strategy and Effectiveness Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevak, P.; Pushkar, B.; Mazumdar, S. Mechanistic evaluation of chromium bioremediation in Acinetobacter junii strain b2w: A proteomic approach. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 328, 116978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Kolk, J.H.; Endimiani, A.; Graubner, C.; Gerber, V.; Perreten, V. Acinetobacter in veterinary medicine, with an emphasis on Acinetobacter baumannii. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance 2019, 16, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, K.E.; Turton, J.F.; Lloyd, D.H. Isolation and identification of Acinetobacter spp. from healthy canine skin. Veterinary Dermatology 2018, 29, 240–e287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maboni, G.; Seguel, M.; Lorton, A.; Sanchez, S. Antimicrobial resistance patterns of Acinetobacter spp. of animal origin reveal high rate of multidrug resistance. Veterinary Microbiology 2020, 245, 108702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotz, P.; Jacobmeyer, L.; Leidner, U.; Stamm, I.; Semmler, T.; Ewers, C. Acinetobacter pittii from Companion Animals Coharboring blaOXA-58, the tet(39) Region, and Other Resistance Genes on a Single Plasmid. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2017, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brachelente, C.; Wiener, D.; Malik, Y.; Huessy, D. A case of necrotizing fasciitis with septic shock in a cat caused by Acinetobacter baumannii. Veterinary dermatology 2007, 18, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klotz, P.; Higgins, P.G.; Schaubmar, A.R.; Failing, K.; Leidner, U.; Seifert, H.; Scheufen, S.; Semmler, T.; Ewers, C. Seasonal occurrence and carbapenem susceptibility of bovine Acinetobacter baumannii in Germany. Frontiers in microbiology 2019, 10, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Bayssari, C.; Dabboussi, F.; Hamze, M.; Rolain, J.-M. Emergence of carbapenemase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii in livestock animals in Lebanon. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2014, 70, 950–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şanlier, N.; Gökcen, B.B.; Sezgin, A.C. Health benefits of fermented foods. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2019, 59, 506–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gennari, M.; Lombardi, P. Comparative Characterization of Acinetobacter Strains Isolated from Different Foods and Clinical Sources. Zentralblatt für Bakteriologie 1993, 279, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Lu, F.; Qiu, M.; Ding, Y.; Zhou, X. Dynamics and Diversity of Microbial Community Succession of Surimi During Fermentation with Next-Generation Sequencing. Journal of Food Safety 2016, 36, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Wang, P.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Y.; Gao, L.; Wang, W. High-throughput sequencing approach to characterize dynamic changes of the fungal and bacterial communities during the production of sufu, a traditional Chinese fermented soybean food. Food Microbiology 2020, 86, 103340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhammed, N.S.; Hussin, N.; Lim, A.S.; Jonet, M.A.; Mohamad, S.E.; Jamaluddin, H. Recombinant Production and Characterization of an Extracellular Subtilisin-Like Serine Protease from Acinetobacter baumannii of Fermented Food Origin. The Protein Journal 2021, 40, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, S.; Pant, T.; Suryavanshi, M.; Antony, U. Microbiological diversity of fermented food Bhaati Jaanr and its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties: Effect against colon cancer. Food Bioscience 2023, 55, 102822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamang, J.P.; Watanabe, K.; Holzapfel, W.H. Review: Diversity of Microorganisms in Global Fermented Foods and Beverages. Frontiers in Microbiology 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuka, M.M.; Engel, M.; Skelin, A.; Redžepović, S.; Schloter, M. Bacterial communities associated with the production of artisanal Istrian cheese. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2010, 142, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Peng, C.; Kwok, L.-y.; Zhang, H. The Bacterial Diversity of Spontaneously Fermented Dairy Products Collected in Northeast Asia. Foods 2021, 10, 2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NM, S.; WF, A.; SM, M. Detection of Acinetobacter species in milk and some dairy products. Assiut Veterinary Medical Journal 2018, 64, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gennari, M.; Parini, M.; Volpon, D.; Serio, M. Isolation and characterization by conventional methods and genetic transformation of Psychrobacter and Acinetobacter from fresh and spoiled meat, milk and cheese. International Journal of Food Microbiology 1992, 15, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafei, R.; Hamze, M.; Pailhoriès, H.; Eveillard, M.; Marsollier, L.; Joly-Guillou, M.-L.; Dabboussi, F.; Kempf, M. Extrahuman Epidemiology of Acinetobacter baumannii in Lebanon. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2015, 81, 2359–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangallo, D.; Šaková, N.; Koreňová, J.; Puškárová, A.; Kraková, L.; Valík, L.; Kuchta, T. Microbial diversity and dynamics during the production of May bryndza cheese. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2014, 170, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| A. baumannii | A. baylyi | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size of genome | Approximately | Approximately | |

| 3.4 to 4.2 Mb | 3.5 Mb | [56,57] | |

| Mobile genetic elements | Plasmids, transposons, Insertion sequences |

More stable genome | [57,58] |

| Antibiotic resistance | A Plethora of genes such as blaOXA-51 and pmrA, efflux pumps such as AdeABC, aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes | Lack of many determinants, more susceptible to antibiotics | [12,57] |

| Virulence factors |

Various factors, such as |

||

| OmpA, CarO, T2SS and T6SS components | Significantly less or none | [49,57] | |

| Metabolic adaptability | |||

| Equipment for survival in hostile environments | More adaptive and versatile | [57,59] | |

| Biofilm formation | Bap, csu operon, quorum sensing system | Less developed strategies | [43,60] |

| Iron acquisition system | Ferric uptake regulator, siderophores - acinetobactin and baumannoferrin | Lack of advanced system | [55,57] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).