Submitted:

08 July 2024

Posted:

09 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Apparatus and Methods

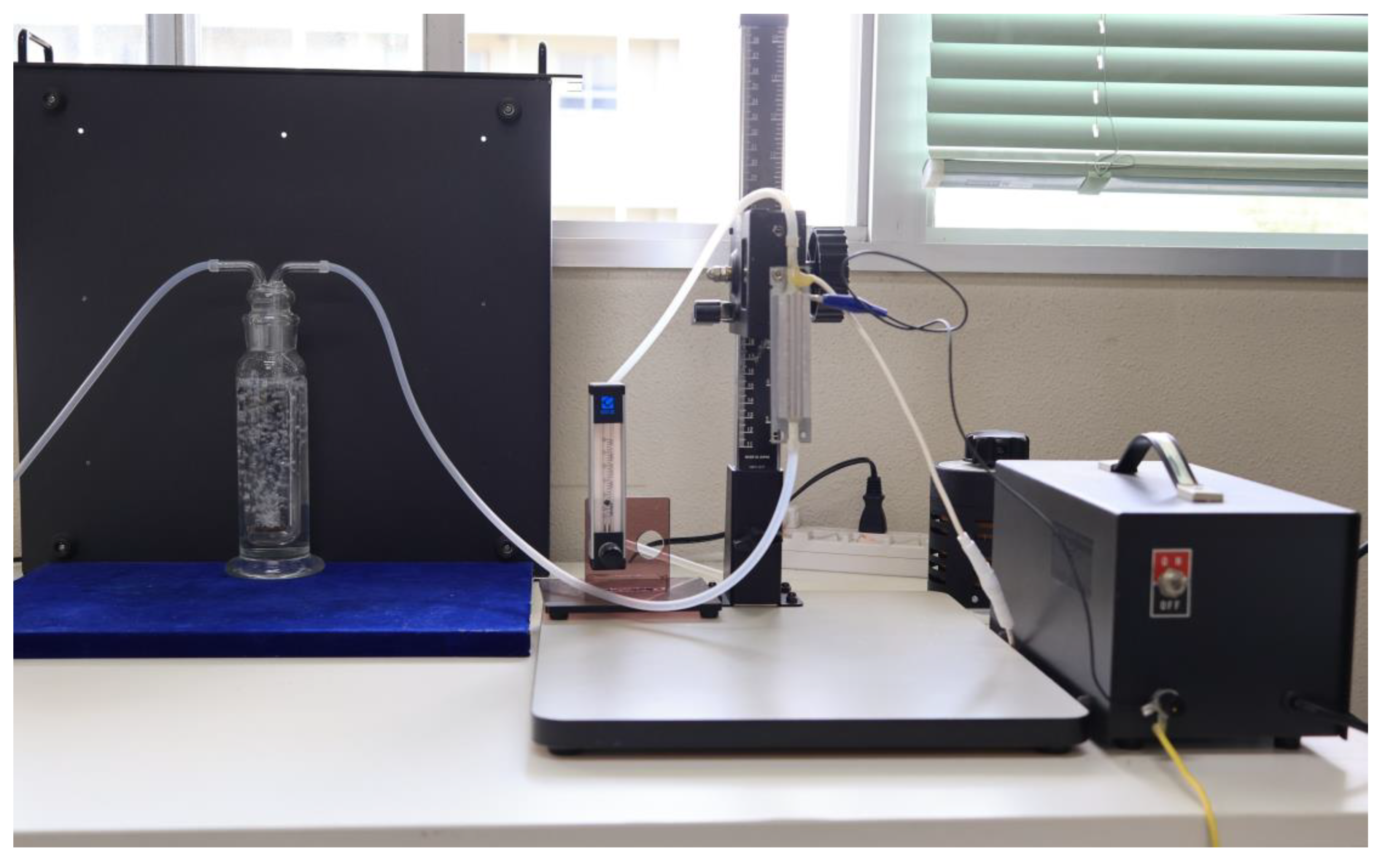

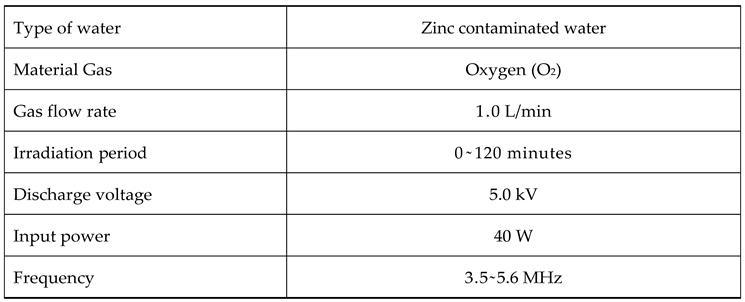

2.1. Preparation of Irrigation Water

2.2. Growth Performance Analysis

2.3. Gene Expression Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Growth Response of Plant

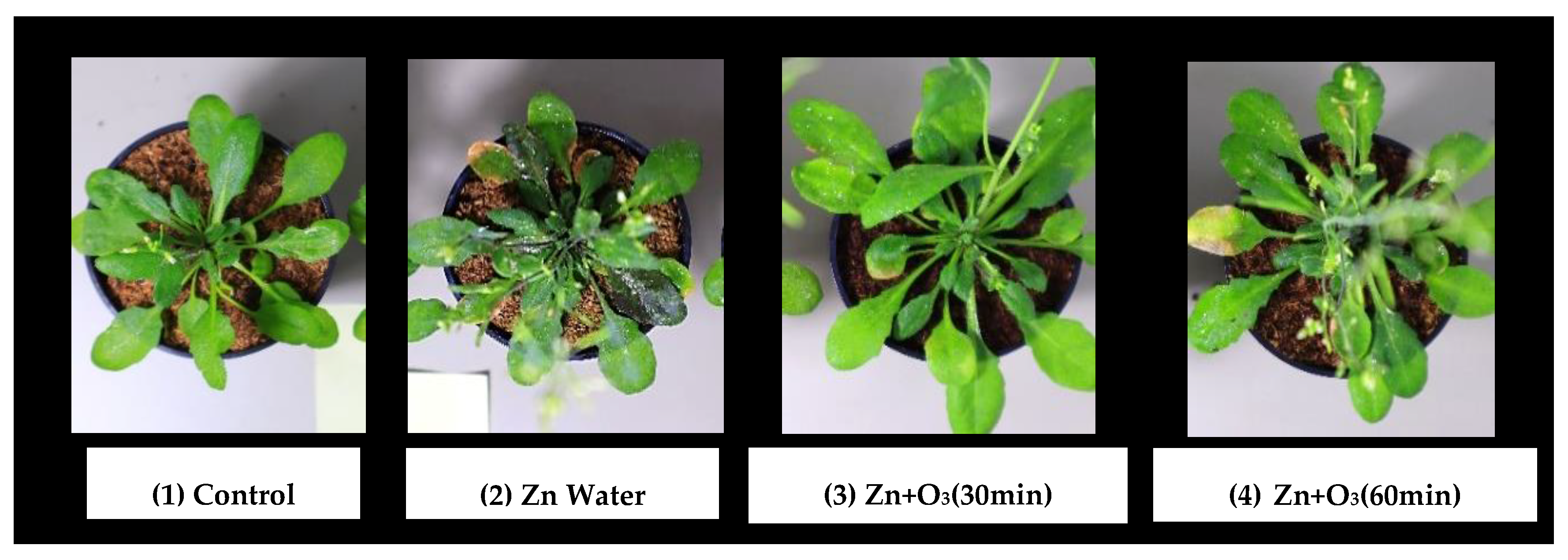

3.1.1. Visual Effect on Plant Growth

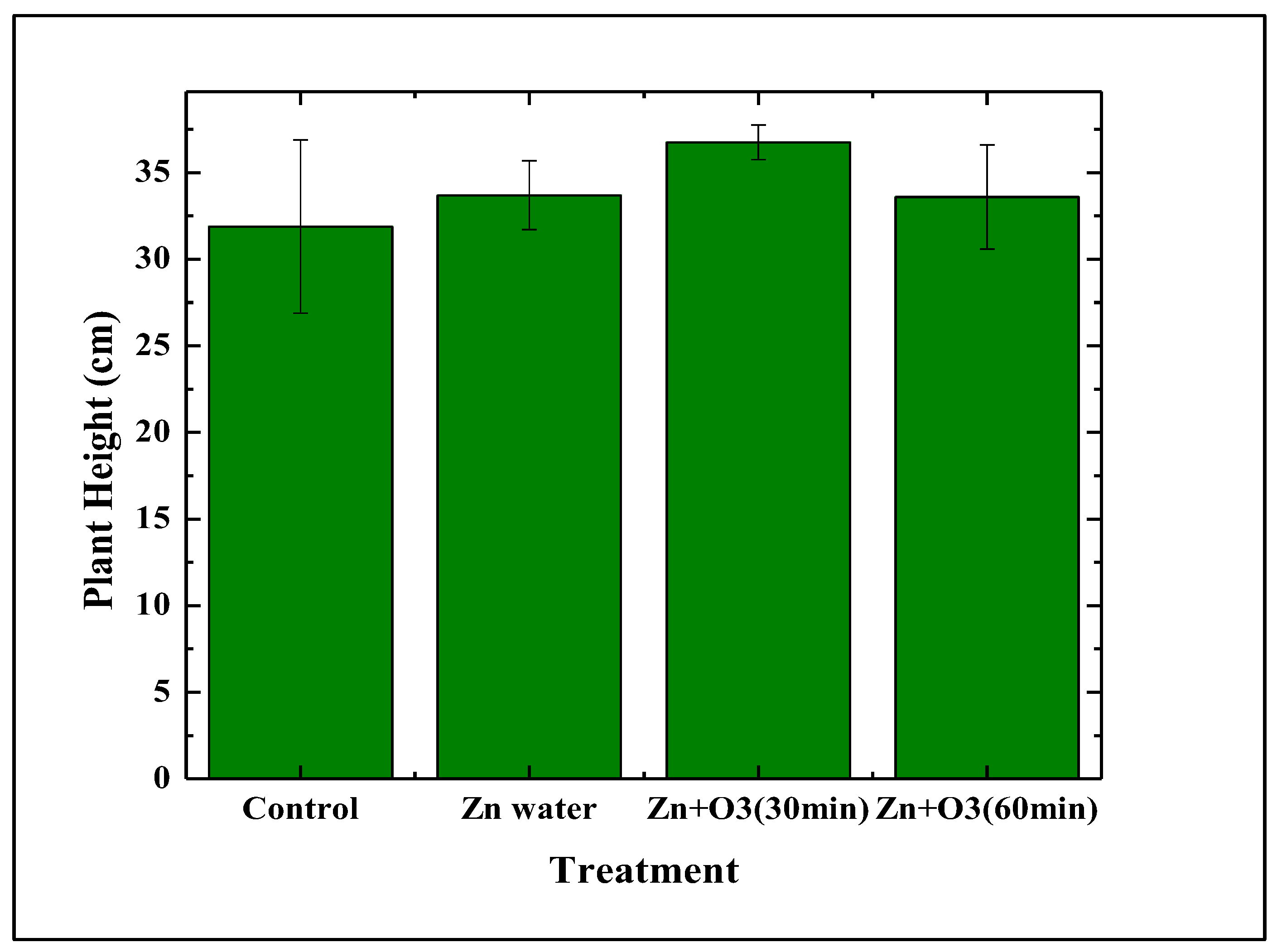

3.1.2. Effect on Plant Height

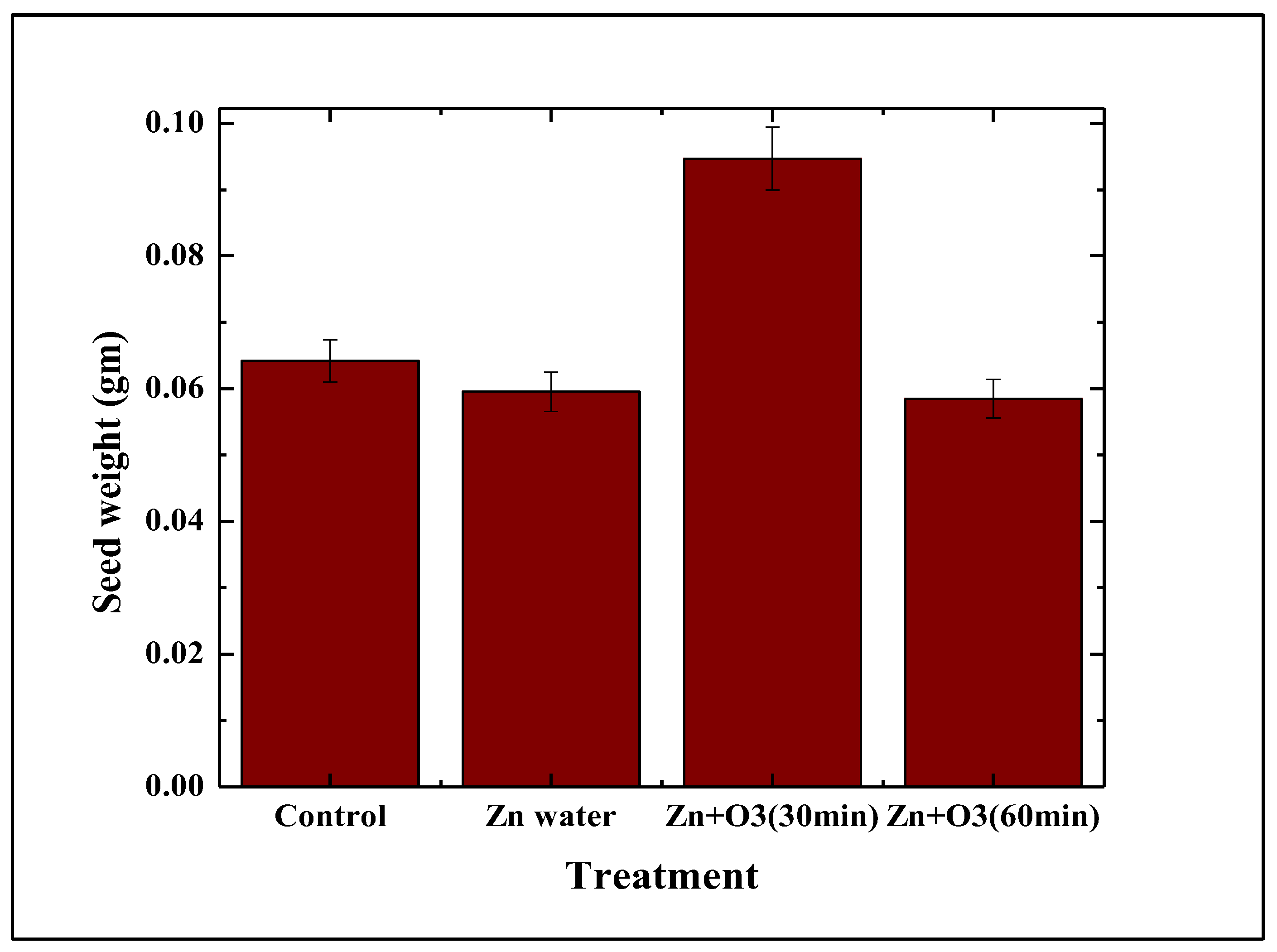

3.1.3. Effect on Seed Weight

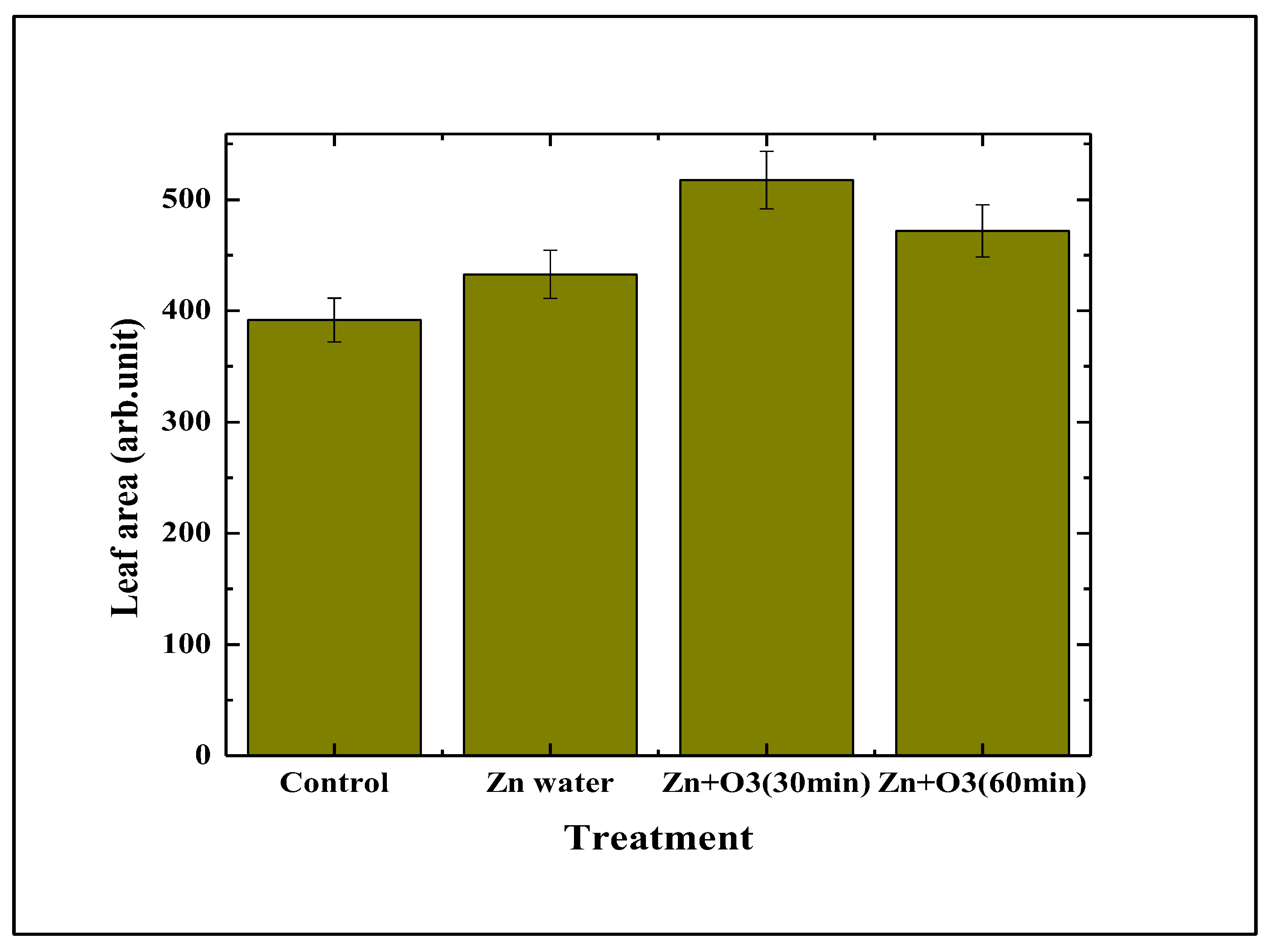

3.1.4. Effect on Leaf Area

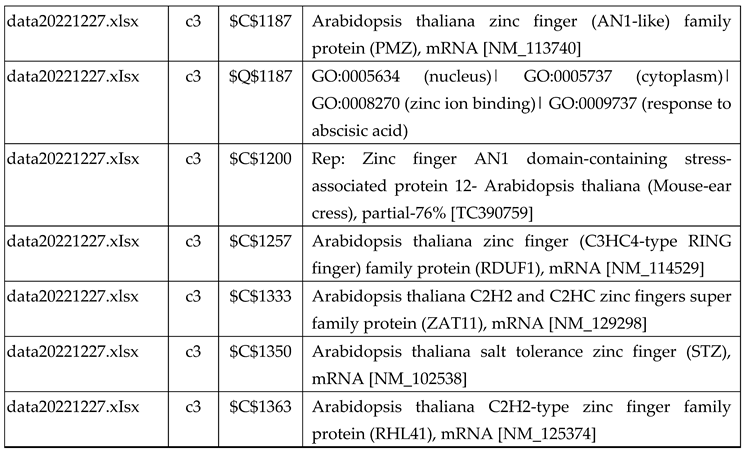

3.2. Evaluation of Zinc Effects on Biological Reactions of Plant

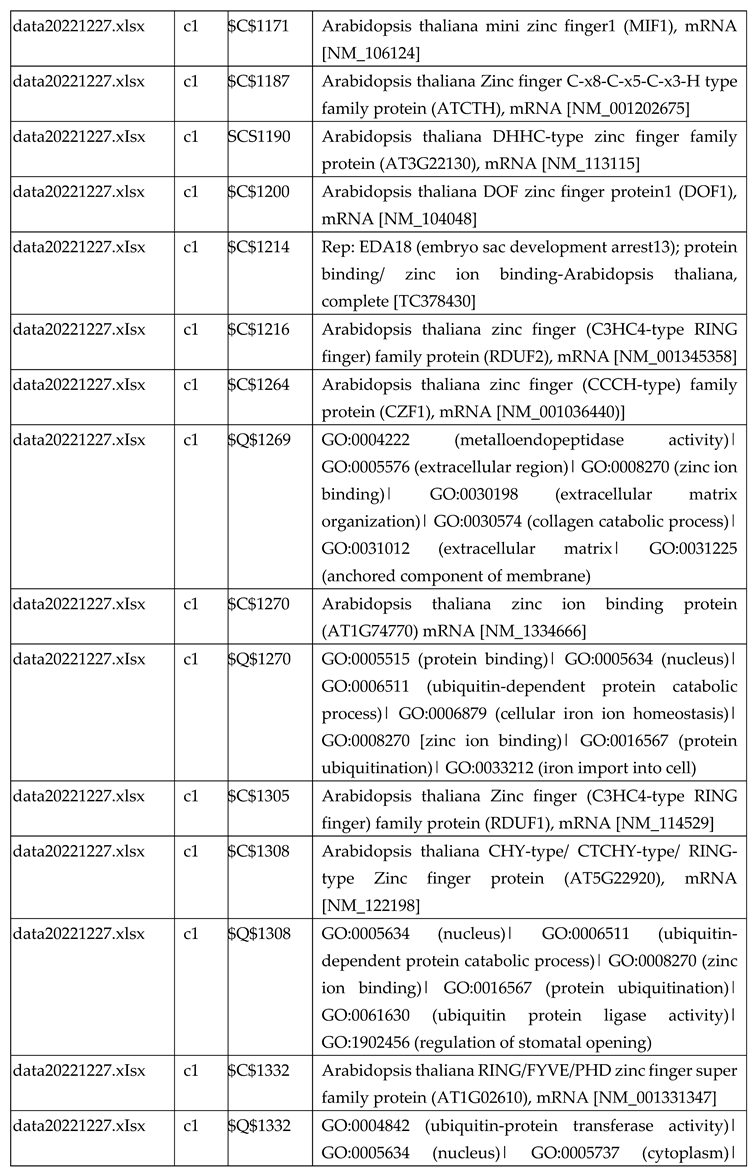

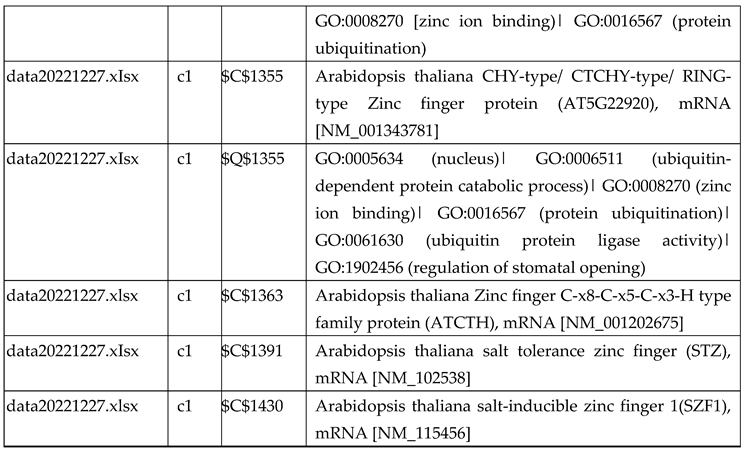

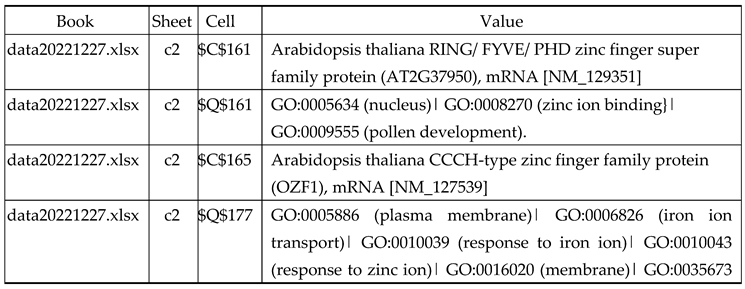

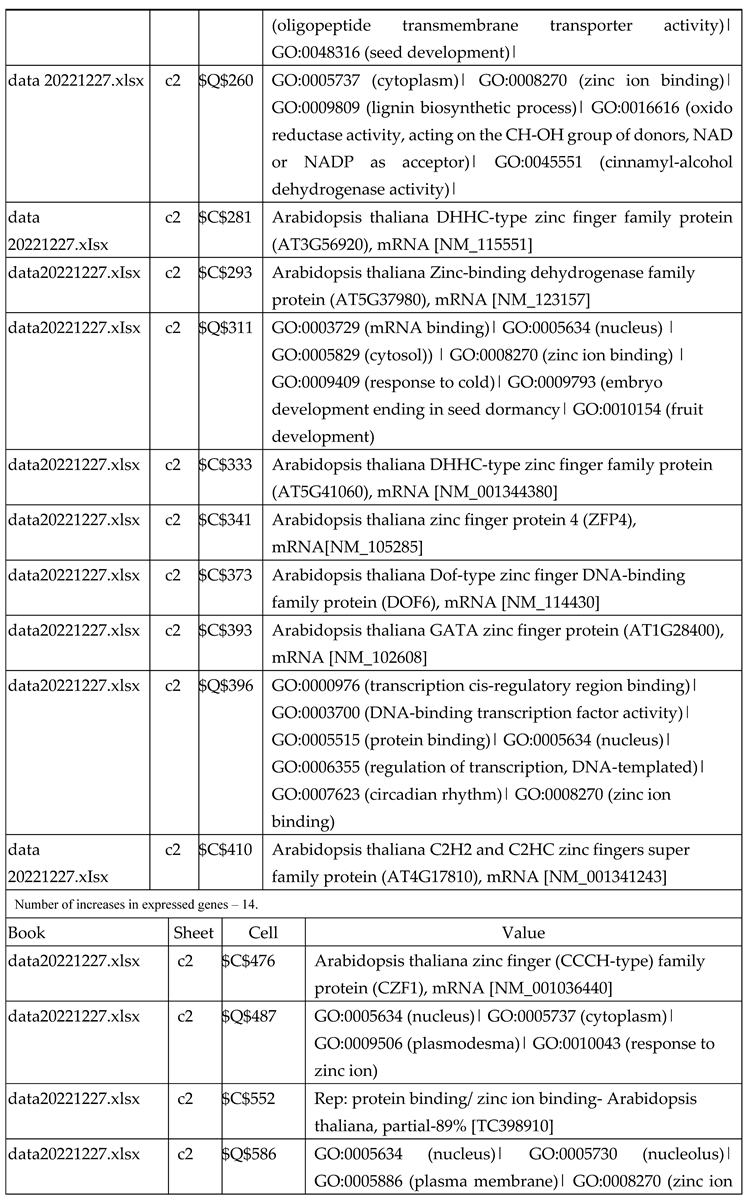

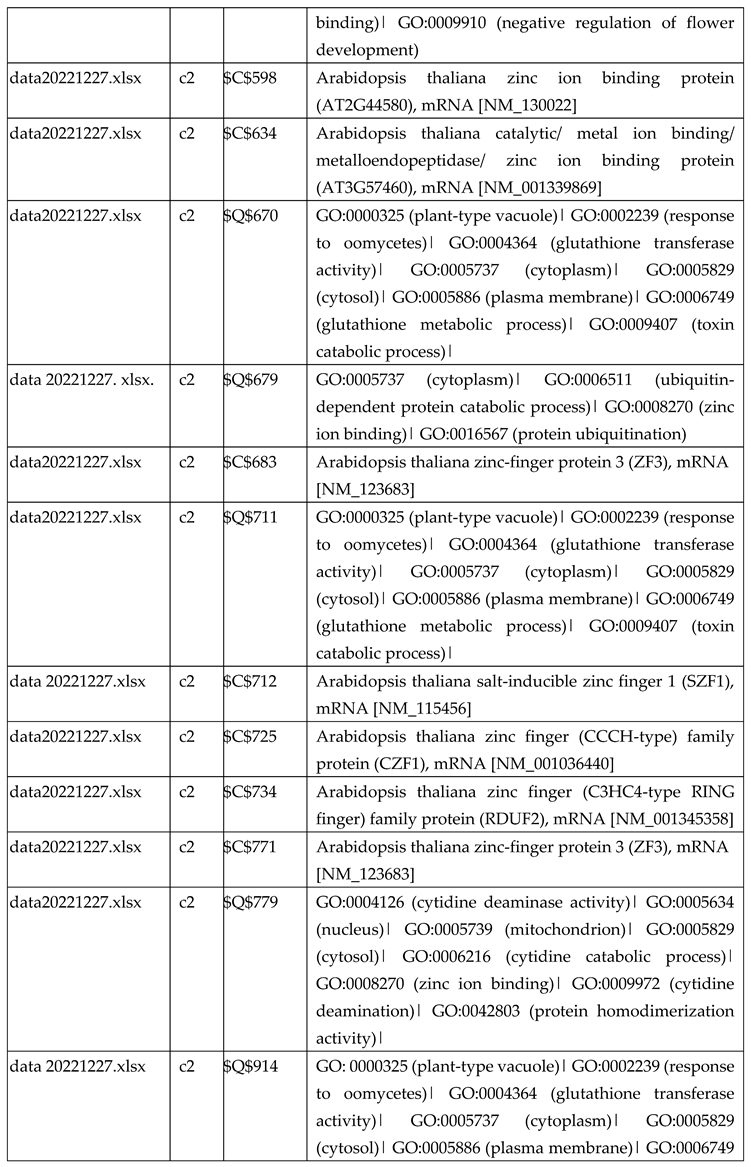

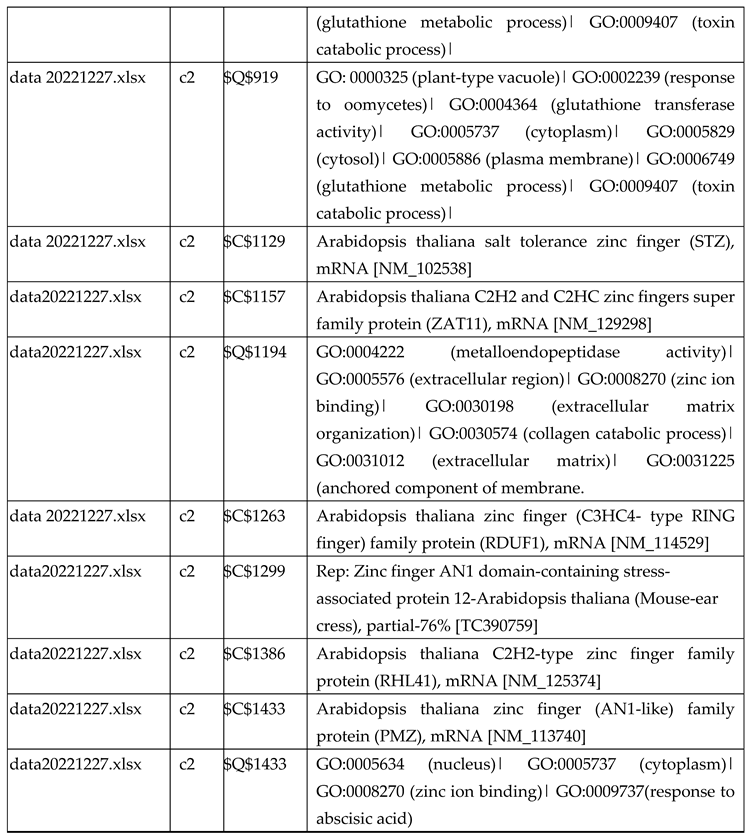

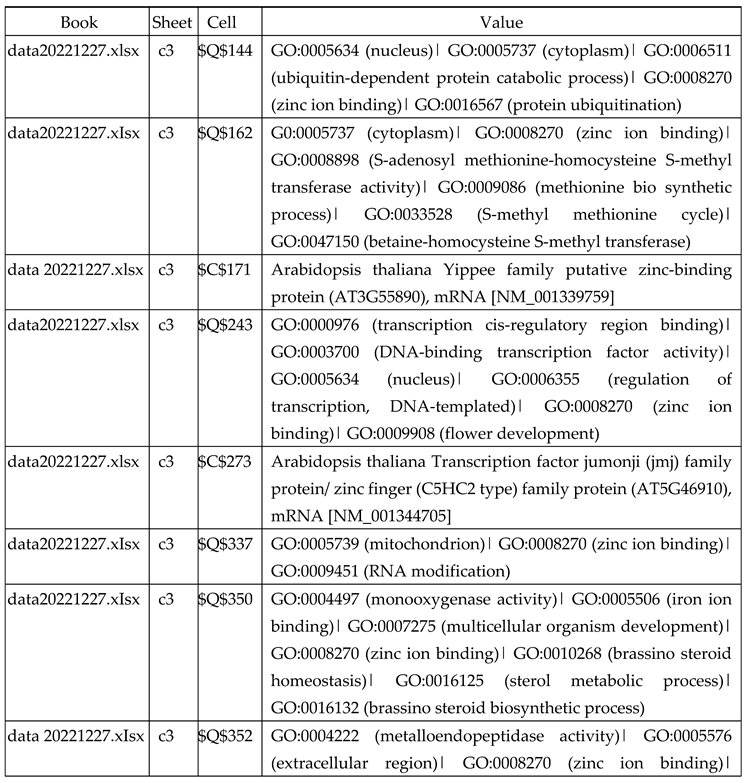

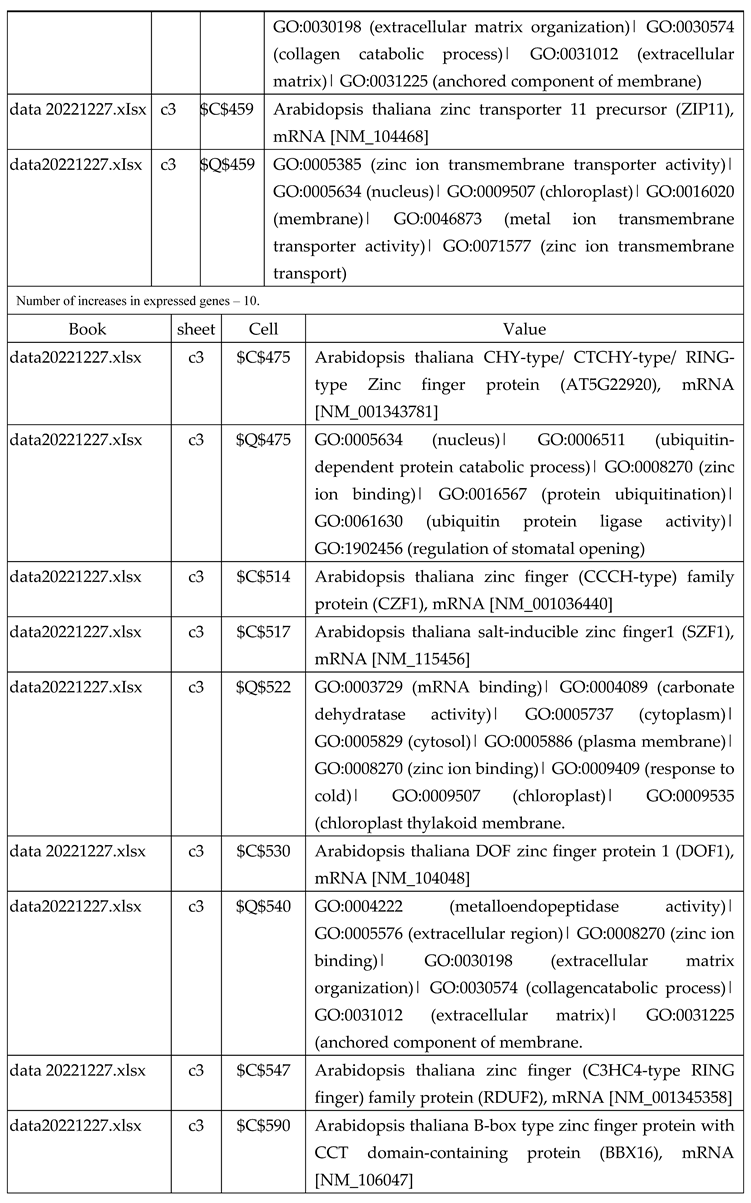

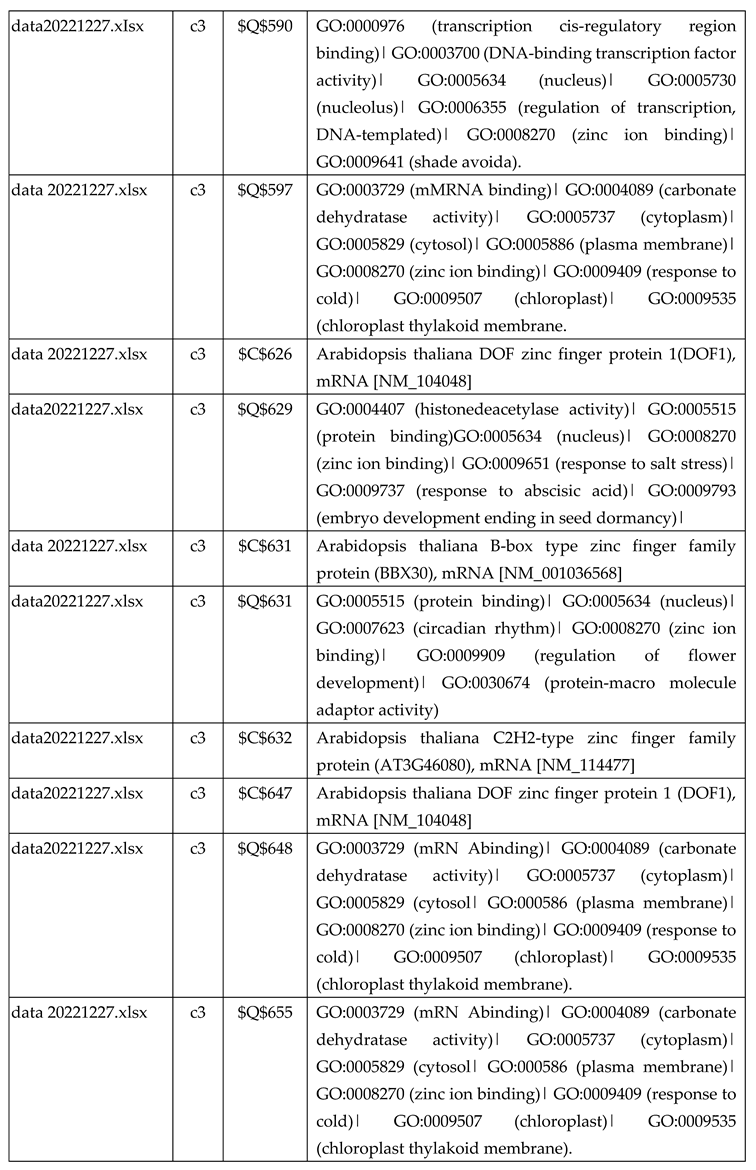

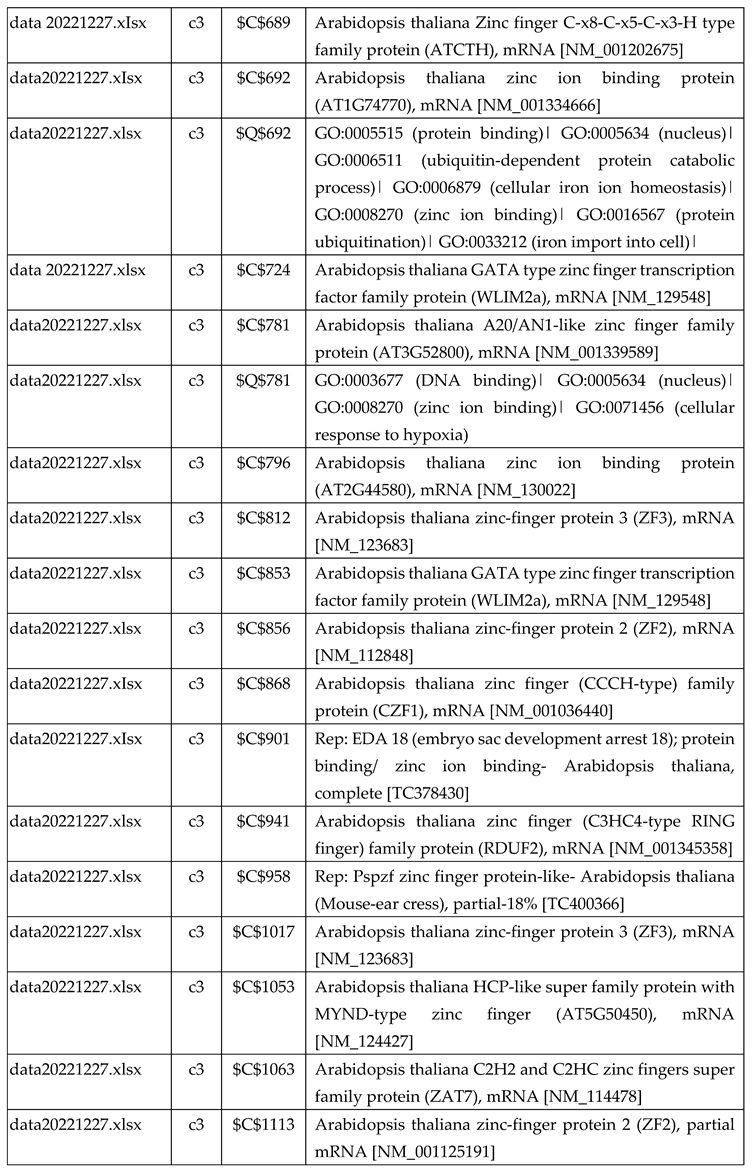

3.2.1. Gene Expression Analysis of Plant Fed with Zn Water

3.2.2. Gene Expression Analysis of Plant Fed with Zn+O3(30min)

3.2.3. Gene Expression Analysis of Plant Fed with Zn+O3(60min)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Charles Pereira, H. Food production and population growth. Land Use Policy, Volume 10(3) 187-190 (1993). [CrossRef]

- Reed, S. C., Crites, R. W. & Middlebrooks, E. J. Natural systems for waste management and treatment. (2nd edition) McGraw-Hill, New York, USA. (1995).

- Bjuhr, J. Trace metals in soils irrigated with waste water in a periurban area downstream Hanoi city, Vietnam. Seminar Paper, Institutionen för markvetenskap, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet (SLU), Uppsala, Sweden. (2007).

- Sobhanardakani, S., Tayebi, L. & Farmany, A. Toxic metal (Pb, Hg, and As) contamination of muscle, gill and liver tissues of Otolithes ruber, Pampus argenteus, Parastromateus niger, Scomberomorus commerson and Onchorynchus mykiss. World Appl. Sci. J. 14, 1453-1456 (2011).

- Barakat, M. A. New trends in removing heavy metals from industrial wastewater. Arabian J. Chem. 4, 361-377 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Rai, P. K., Lee, S. S., Zhang, M., Tsang, Y. F. & Kim, K. H. Heavy metals in food crops: Health risks, fate, mechanisms, and management. Environ. Int. 125, 365-385 (2019). [CrossRef]

- El-Sherif, I. Y., Tolani, S., Ofosu, K., Mohamed, O. A. & Wanekaya, A. K. Polymeric nanofibers for the removal of Cr(III) from tannery waste water. J. Environ. Manag. 129, 410-413 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Borba, C. E., Guirardello, R., Silva, E. A., Veit, M. T. & Tavares, C. R. G. Removal of nickel(II) ions from aqueous solution by biosorption in a fixed bed column: Experimental and theoretical breakthrough curves. Biochem. Eng. J. 30, 184-191 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Taseidifar, M., Makavipour, F., Pashley, R. M. & Rahman, A. F. M. M. Removal of heavy metal ions from water using ion flotation. Environ. Technol. Innov. 8, 182-190 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y., Wang, X., Khan, A., Wang, P., Liu, Y., Alsaedi, A., Hayat, T. & Wang, X. Environmental remediation and application of nanoscale zero-valent iron and its composites for the removal of heavy metal ions: A review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 7290-7304 (2016). [CrossRef]

- García-Niño, W. R. & Pedraza-Chaverrí, J. Protective effect of curcumin against heavy metals-induced liver damage. Food Chem. Toxicol. 69, 182-201 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Tjandraatmadja, G. & Diaper, C. Sources of critical contaminants in domestic wastewater: contaminant contribution from household products. CSIRO: Water for a healthy country national research flagship. Australia. (2006). https://publications.csiro.au/rpr/download?pid=procite:e8e1f460-b821-4c47-871c-3a2eb7a77c5d&dsid=DS1.

- Mansourri, G. & Madani, M. Examination of the level of heavy metals in wastewater of Bandar Abbas Wastewater Treatment Plant. Open J. Ecol. 6, 55-61 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Lebourg, A., Sterckeman, T., Ciesielski, H. & Proix, N. Trace metal speculation in three unbuffered salt solutions used to assess their bioavailability in soil. J. Environ. Qual. 27, 584-590 (1998). [CrossRef]

- Alloway, B. J. Zinc in soils and crop nutrition. (second ed.), IZA and IFA, Brussels Belgium, Paris, France. (2008).

- Cakmak, I. Enrichment of cereal grains with zinc: agronomic or genetic biofortification. Plant Soil. 302, 1-17 (2008). [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Ambient water quality criteria for silver, EPA-440/5-80-071. Office of water regulations and standards, Criteria and standard division. Washington, DC. (1980).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Exposure and risk assessment for zinc, EPA 440/4-81-016. Office of water regulations and standards, (WH-553). Washington, DC. (1980).

- FAO/WHO. Evaluation of certain food additives and contaminants. Joint FAO/WHO expert committee on food additives, (WHO Food Additives Series, No. 17). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. (1982).

- Zinicovscaia, I., Yushin, N., Grozdov, D., Abdusamadzoda, D., Safonov, A. & Rodlovskaya, E. Zinc-containing effluent treatment using shewanella xiamenensis biofilm formed on zeolite. Materials. 14, 1760 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Pozdniakova, T. A., Mazur, L. P., Boaventura, R. A. R. & Vilar, V. J. P. Brown macro-algae as natural cation exchangers for the treatment of zinc containing wastewaters generated in the galvanizing process. J. Clean Prod. 119, 38-49 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Zueva, S. B., Ferella, F., Innocenzi, V., De Michelis, I., Corradini, V., Ippolito, N.M. & Vegliò, F. Recovery of zinc from treatment of spent acid solutions from the pickling stage of galvanizing plants. Sustainability. 13, 407 (2021). [CrossRef]

- John, M., Heuss-Assbichler, S. & Ulrich, A. Recovery of Zn from wastewater of zinc plating industry by precipitation of doped ZnO nanoparticles. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 13, 2127-2134 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M., Kozik, V., Bąk, A., Barbusiński, K., Jazowiecka-Rakus, J. & Jampilek, J. Removal of heavy metal ions from wastewaters: an application of sodium trithiocarbonate and wastewater toxicity assessment. Materials. 14, 655 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Zinicovscaia, I., Yushin, N., Abdusamadzoda, D., Grozdov, D. & Shvetsova, M. Efficient removal of metals from synthetic and real galvanic zinc-containing effluents. Brewer’s Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Materials. 13, 3624 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Lebourg, A., Sterckeman, T., Ciesielski, H. & Proix, N. Trace metal speculation in three unbuffered salt solutions used to assess their bioavailability in soil. J. Environ. Qual., 27, 584-590 (1998). [CrossRef]

- Pratt, P. F. Quality criteria for trace elements in irrigation waters. University of California, Division of Agricultural Sciences, California Agricultural Experiment Station, p.46. (1972).

- Available online: https://www.dcceew.gov.au/environment/protection/npi/substances/fact-sheets/zinc-and compounds.

- Kang, G. D. & Cao, Y. M. Development of antifouling reverse osmosis membranes for water treatment: A review. Water Research. 46(3), 584-611 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A., Mandal, T., Ganguly, A. & Chatterjee, P.K. Lignin degradation in the production of bioethanol-A review. Chem. Bio. Eng. Rev. 3(2), 86-96 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V. K. & Ali, I. Environmental Water (Ed: V. K. G. Ali), Elsevier, Amsterdam (2013).

- Ipek, U. Removal of Zn2+ and Ni2+ from an Aqueous Solution by Reverse Osmosis. Desalination. 174(2),161-169 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Muataz, A., Atieh, Ji, Y. & Kochkodan, V. Metals in the Environment: Toxic Metals Removal, Bioinorganic Chemistry and Applications. Volume 2017, Article ID 4309198. [CrossRef]

- Gupta DA. Implication of environmental flows in river basin management. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth. 33(5), 298-303 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Adhoum, N., Monser, L., Bellakhal, N. & Belgaied, J. E. Treatment of electroplating wastewater containing Cu2+, Zn2+ and Cr (VI) by electrocoagulation. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 112(3), 207-213 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Hunsom, M., Pruksathorn, K., Damronglerd, S., Vergnes, H. & Duverneuil, P. Electrochemical treatment of heavy metals (Cu2+, Cr6+, Ni2+) from industrial effluent and modeling of copper reduction. Water Research. 39(4), 610-616 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Brusick, D. Genotoxicity of Phenolic Antioxidants. Toxicol. Ind. Health. 9 (1-2), 223-230 (1993). [CrossRef]

- Merzouk, B., Yakoubi, M., Zongo, I., Leclerc, J. P., Paternotte, G., Pontvianne, S. & Lapicque, F. Effect of modification of textile wastewater composition on electrocoagulation efficiency. Desalination. 275(1), 181-186 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Grimm, J., Bessarabov, D. & Sanderson, R. Review of electro-assisted methods for water purification. Desalination. 115(3), 285-294 (1998). [CrossRef]

- De Zuane, J. Handbook of Drinking Water Quality: Standards and Controls. Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York, Van Nostrand Reinhold. (1990).

- Kurniawan, T. A., Gilbert, Y. S., Chan, Lo, W. H. & Babel, S. Physico-chemical treatment techniques for wastewater laden with heavy metals. Chemical Engineering Journal. 118 (1-2), 83-98 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Oyaro, N., Juddy, O., Murago, E. N. M. & Gitonga, E. The contents of Pb, Cu, Zn and Cd in meat in Nairobi, Kenya. Journal of Food, Agriculture and Environment. 5(3&4), 119-121 (2007).

- Borba, C. E., R. Guirardello, R., Silva, E. A., Veit, M. T. & Tavares, C. R. G. Removal of nickel (II) ions from aqueous solution by biosorption in a fixed bed column: Experimental and theoretical breakthrough curves. Biochemical Engineering Journal. 30(2), 184-191 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. & Choi, W. Photocatalytic Oxidation of Arsenite in TiO2 Suspension: Kinetics and Mechanisms. Environmental Science & Technology. 36(17), 3872-3878 (2002). [CrossRef]

- Fry, L. M., Mihelcic, J. R. & Watkins, D. W. Water and non-water related challenges of achieving global sanitation coverage. Environmental Science & Technology. 42(12), 4298-4304 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, M. A. & Elimelech, M. Water and sanitation in developing countries: including health in the equation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41(1), 17-24 (2007). PMID: 17265923. [CrossRef]

- Hahladakis, J., Smaragdaki, E., Vasilaki, G. & Gidarakos, E. Use of Sediment Quality Guidelines and pollution indicators for the assessment of heavy metal and PAH contamination in Greek surficial sea and lake sediments. Environ. Monit. Assess. 185(3), 2843-2853 (2013). Epub 2012 Jul 22. PMID: 22821321. [CrossRef]

- Khanom, S. & Hayashi, N. Removal of metal ions from water using oxygen plasma. Scientific Reports. 11, 9175 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Shibata, S. Solvent extraction behavior of some metal-1-(2-pyridylazo)-2-naphthol chelates. Analytica Chimica Acta. 23, 367-369 (1960). [CrossRef]

- Huang, D. W., Sherman, B. T. & Lempicki, R. A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID Bioinformatics Resources. Nat. Protoc. 4, 44-57 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Huang, D. W., Sherman, B. T. & Lempicki, R. A. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: Paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 1-13 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K., Wani, S. H., Razzaq, A., Skalicky, M., Samantara, K., Gupta, S., Pandita, D., Goel, S., Grewal, S., Hejnak, V., Shiv, A., El-Sabrout, A. M., Elansary, H. O., Alaklabi, A. & Brestic, M. Abscisic Acid: Role in fruit development and ripening. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 817500 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Dorion, S., Ouellet, J. C. & Rivoal, J. Glutathione Metabolism in Plants under Stress: Beyond Reactive Oxygen Species Detoxification. Metabolites. 11(9), 641 (2021). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).