1. Introduction

Enterococci are aerobic gram-positive bacteria that typically inhabit the human gastrointestinal tract (1). Among human enterococcal infections, the predominant causative agents are Enterococcus faecalis (E. faecalis) and Enterococcus faecium (E. faecium), with the latter being less prevalent, though proportions may vary among studies(2). Despite generally low virulence, these bacteria can precipitate severe infections, particularly in immunocompromised individuals (2). Notably, enterococcal species demonstrate intrinsic resistance to various antibiotic classes, encompassing cephalosporins and most carbapenems. While E. faecalis typically remains sensitive to ampicillin and subsequently piperacillin, over 80% of E. faecium isolates in Sweden exhibit penicillin resistance (3). Enterococci can acquire additional resistance rendering them insensitive to vancomycin (4), which is of critical concern globally, albeit still rare in Sweden where vancomycin resistance is reported in less than one percent of enterococcal blood culture isolates (3). Enterococcal bacteraemia (EB) has increased globally and is associated with high in-hospital mortality rate, ranging from 11-36%, with comorbidities and previous antibiotic exposure emerging as risk factors (5-7).

In Sweden, efforts to limit antibiotic resistance through stringent antibiotic policies favoring narrow-spectrum antibiotics has a longstanding tradition. During the early 2000-ies, in face of the emerging occurrence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) in Enterobactereales and the first reported outbreak of multiresistant ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae in Scandinavia, a reduction of cephalosporin use was strongly favoured(8). Consequently, there was an upsurge in the utilization of alternative antibiotics effective against gram-negative or polymicrobial infections, such as piperacillin/tazobactam (pip/taz) (9). However, this shift in antibiotic protocols may inadvertently contribute to the selective pressure favoring ampicillin-resistant enterococci, including E. faecium.

The objective of this study was twofold: firstly, to evaluate whether the incidence of E. faecium bacteremia (EfmB) relative to E. faecalis bacteremia (EfsB) increased between 2015 and 2021; secondly, to analyze the risk factors associated with acquiring EfmB, with a particular focus on prior antibiotic exposure.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at Sahlgrenska University Hospital, a 1,500 bed university hospital in Western Sweden. All patients over 18 years, with positive blood cultures for E. faecium or E. faecalis between 2015–2021, were included in the patient population while only patients with an EB in 2015, 2018 and 2021 were included in the medical record review and in the risk factor analysis. Each patient was included only once per year. Patient data, including demographic and medical information, was collected through medical record review. An episode of EB was defined as the presence of at least one positive blood culture containing either E. faecium or E. faecalis. The day of bacteremia onset was defined as the day of collection of the positive blood culture. Bacteremia was classified as hospital-acquired if the positive blood culture was obtained 48 hours or more after hospital admission; otherwise, it was considered community-acquired. Variables of interest included hospital vs. community-acquired bacteraemia, predisposing factors, comorbidities, prior hospital antibiotic exposure within 90 days preceding the positive blood culture, and mortality rates in-hospital and at 30 days, 90 days, and 1 year.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Patients were categorized based on whether they had EfmB or EfsB. Continuous data were presented as median and interquartile ranges, while categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages. The statistical analysis was performed in SPSS statistics version 29 and a p-value below 0.05 was considered significant. Pearson Chi-square was used to compare categorical variables, and the Mann-Whitney U test was employed to compare medians between continuous data. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression model were used to identify risk factors for contracting EfmB over EfsB. Variables that exhibited statistical significance in the univariate analysis were incorporated into the multivariate regression analysis to ascertain their persistent significance after adjusting for potential confounding factors.

3. Results

3.1. Epidemiology and Demographics

In the years 2015, 2018 and 2021, 171 patients with bacteraemia caused by

E. faecium and 189 with

E. faecalis were included in the study (

Table 1). In 2015, 98 unique patients had an episode of EB compared to 113 patients in 2020 and 149 patients in 2021. Simultaneously, the total number of blood cultures processed at the Microbiological Laboratory at Sahlgrenska University Hospital increased from 46 573 in 2015 to 49 264 in 2018 and 52 790 in 2021 (data not shown).

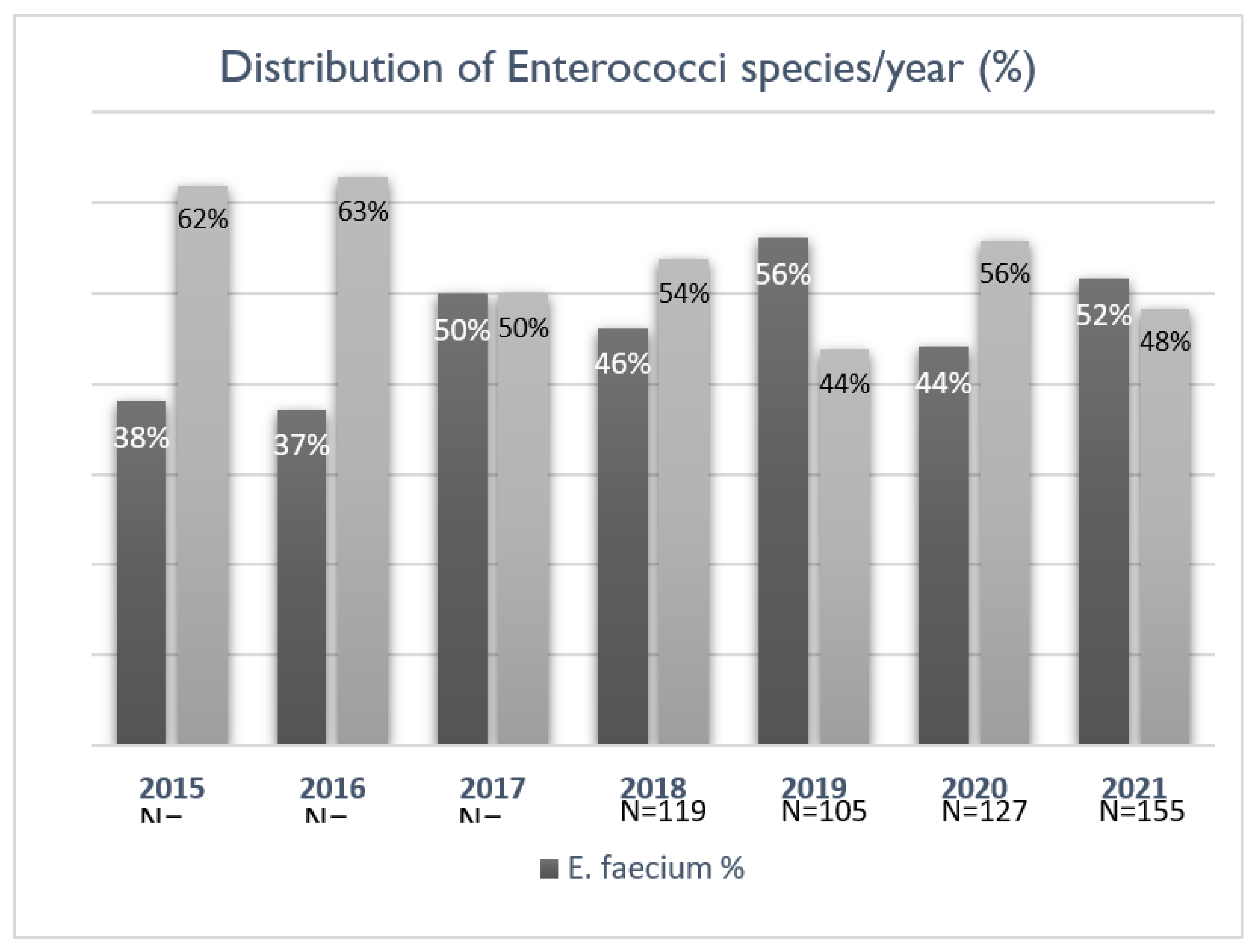

The occurrence and distribution of bacteraemia caused by

E. faecium and

E. faecalis were evaluated for the entire study period from 2015 to 2021 (n=840). Although there was a rise in the number of EB cases over the years, this did not correspond to a statistically significant increase. Initially, the proportion of cases attributed to

E. faecium was below 40%, with an upward trend in the later years of the study (

Figure 1). All

E. faecalis isolates and 9.9% of the

E. faecium isolates were sensitive to ampicillin.

Patients with EfsB were older (76 vs. 67 years, p<0.001) compared to those with EfmB. The two enterococcal species were both more prevalent in males. Among comorbidities, hypertension was more prevalent in patients with EfsB (96/189, 51%) compared to those with EfmB (67/171, 39%) (p=0.027). Hematological malignancy (28/179, 16% vs. 12/196, 6%, p=0.003) and immunosuppression (48/171, 28% vs. 27/189, 14%, p=0.002) were more common in patients with EfmB. Regarding predisposing procedures, the presence of a urinary catheter at the onset of bacteremia did not differ between the two sub-populations, while the use of a drain port, central vascular catheter, or recent surgery was more prevalent in patients with EfmB. Bacteraemia was monomicrobial in a majority of the patients (137/189, 72% of EfsB vs. 138/171, 81% of EfmB, ns).

The unadjusted in-hospital mortality rates were 22% (42/189) and 20% (35/171) in the E. faecalis and E. faecium groups (ns). At 90-days post bacteraemia onset, mortality reached 34% (65/189) in the E. faecalis group and 33% (56/171) in the E. faecium group. One year mortality (assessed 2015 and 2018) was 47% and 54%, respectively.

3.2. Changing Antibiotic Prescription Practices

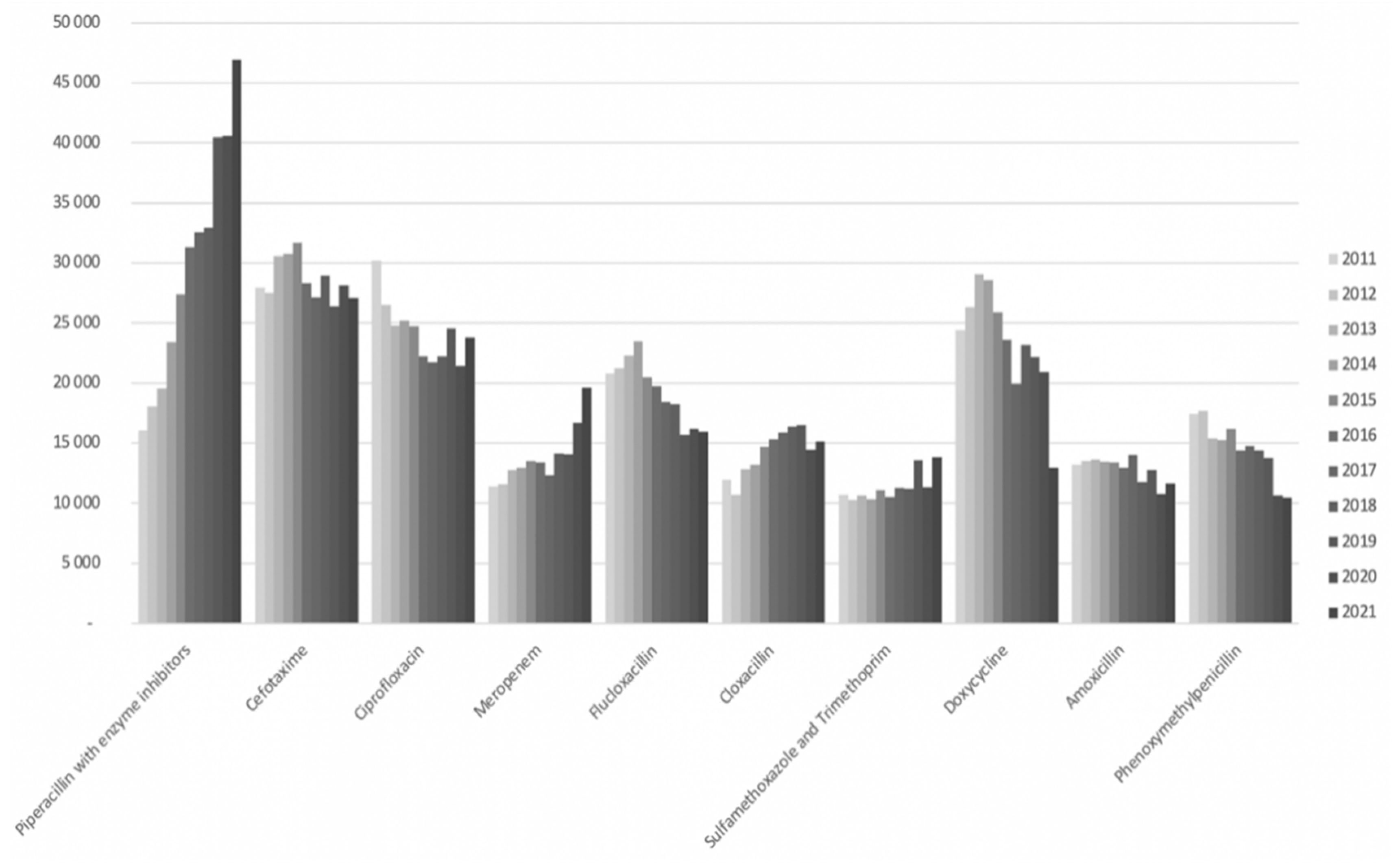

From 2011 to 2021, the consumption of pip/taz increased from 16,000 to 47,000 daily defined doses (DDD) per year at Sahlgrenska University Hospital as shown in

Figure 2. Notably, in 2016, pip/taz emerged as the most prescribed antibiotic in the hospital, with its prescription rate steadily escalating thereafter. This increase was partially offset by a reduction in the use of cephalosporins and ciprofloxacin, although not entirely compensated. Furthermore, there was a notable rise in meropenem usage over the years, with a particularly steep incline observed from 2020 to 2021, partly attributed to revised standard dose recommendations.

3.3. Antibiotic Use Prior To Bacteraemia Onset

Data on antibiotic usage within 90 days before collection of the first positive blood culture with

E. faecalis or

E. faecium is presented in

Table 2. Among patients with EfsB, 40 (21%) had received pip/taz, while the corresponding number was higher in patients with EfmB, 95 (56%) (p<0.001). The use of meropenem, the preferred carbapenem in the hospital, and ciprofloxacin, the predominant flouroquinolone in use, was also more prevalent in patients with EfmB. A minority of the patients in both groups had not been prescribed any antibiotics within three months before the onset of bacteraemia, and this was less common in the EfmB compared to the EfsB patients (9% vs. 38%; p<0.001).

3.4. Variables Associated with E. faecium bacteraemia

In the logistic regression analysis, several variables were found to be associated with an increased odds ratio (OR) of having bacteremia with

E. faecium compared to

E. faecalis (

Table 3). Hospital acquisition exhibited an unadjusted OR of 5.02 (95% confidence interval (CI) 3.19-7.90) and an adjusted OR (aOR) of 2.23 (95% CI 1.19–4.15) for EfmB in comparison to EfsB. Other factors related to hospital care, such as prior surgery, the presence of a central venous catheter, urinary catheter, or surgical drain, demonstrated increased ORs for

E. faecium in univariate comparison but not after adjusting for covariates.

If the patient had received pip/taz within 90 days before the date of the positive blood culture aOR for E faecium was 2.63 (95% CI 1.49–4.67). Similarly, if the patient had received meropenem, the aOR was 4.26, 95% CI 2.12–8.56. The univariate OR for E. faecium associated with the use of ciprofloxacin was 2.44 (95% CI 1.46–4.10), but this was not significant after adjusting for other variables (aOR 1.88, 95% CI 0.98–3.63, p=0.059).

4. Discussion

Our study, conducted over a six-year period 2015–2021 at Sahlgrenska University Hospital, aimed to investigate the potential increase in bacteraemia caused by E. faecium in relation to changes in antibiotic use. While our findings did not establish a significant rise, a trend towards a higher proportion of E. faecium compared to E. faecalis in the later years of the study was observed. This trend aligns with similar observations documented internationally, indicating a global increase in the prevalence of E. faecium bacteraemia (9-12). Moreover, the overall number of EB appeared to increase over the study period. Similar trends of rising prevalence of bacteraemia caused by E. faecium have been documented internationally including in studies conducted in the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Denmark, and the United States (10-13) although opposite trends have been reported (13). It is worth noting that vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) are uncommon in Sweden, unlike in the United States, where VRE accounts for a majority of EB cases. In contrast to the findings of rising EfmB incidence, a study from Switzerland reported an increase in E. faecalis cases (14). Notably, the reasons behind these shifts in enterococcal epidemiology remain complex and likely vary across different regions and patient cohorts.

Compared to a Danish study from 2014, our cohort exhibited a slightly higher proportion of E. faecium cases (6). In another cohort study conducted over 10 years in Japan, E. faecalis accounted for 48% of cases, E. faecium for 30%, and other enterococcal species for 22% (15).

Additionally, our study identified several demographic and clinical factors differing patients with bacteraemia caused by E. faecium compared to E. faecalis. Patients with EfsB were older and exhibited a higher prevalence of hypertension while hematological malignancy and immunosuppression was more common in the EfmB patients. Additionally, certain predisposing procedures, including the presence of a central vascular catheter or recent surgery, were more commonly observed in patients with EfmB. The relatively high frequency of E. faecium in our cohort can be attributed to the tertiary care setting at Sahlgrenska University Hospital, which includes facilities for solid organ transplantation, stem cell transplantation and specialized oncology units, among other highly advanced medical facilities. These units treat highly vulnerable and immunodeficient patients prone to nosocomial infections, and there was an independent higher OR for nosocomial aquistion of bacteraemia caused E. faecium

In our population, the trend towards a higher proportion of EfmB coincided with increased use of the antibiotic piperacillin/tazobactam, which from 2016 was the most commonly used antibiotic in the hospital. Pip/taz has an excellent antimicrobial effect against E. faecalis while 90% of E. faecium strains in the study are resistant, thus likely being favored by this shift in antibiotic prescription practices. The substantial increase in the utilization of pip/taz over the study period, coupled with a concurrent rise in meropenem usage, reflects dynamic changes in antimicrobial stewardship practices and treatment preferences (15). To what extent the adoption of pip/taz as the most prescribed antibiotic in the hospital may have contributed to the observed trends in EB epidemiology remains unclear. Alternative broad-spectrum antibiotics that may be used also exert selective pressure on microbial populations. Therefore, further investigations are warranted to elucidate the complex interplay between antibiotic utilization patterns and the emergence of antimicrobial resistance.

Antibiotic exposure within 90 days prior to the onset of bloodstream infection was very common, observed in 91% of patients with EfmB and 62% of patients with EfsB. Notably, exposure to pip/taz was independently associated with a higher risk of E. faecium, with an adjusted odds ratio of 2.63 in the logistic regression model. The relationship between previous meropenem exposure and increased odds for E. faecium was even stronger, which was somewhat unexpected but consistent with recent studies. The findings suggest a potential effect of meropenem, particularly at high concentrations, on ampicillin-susceptible enterococci, despite this antibiotic being considered ineffective against E. faecalis(16). The sequential use of both antibiotics in individual patients and other unaccounted patient-related factors may also contribute to this association. Although there was a association between previous ciprofloxacin use and subsequent EfmB in the univariate comparison, it did not remain significant after adjustment. However, the selective pressure of fluoroquinolone use on enterococci, regardless of species, is likely.

Our study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. Firstly, it is a retrospective study, which inherently comes with certain limitations including reliance on existing medical records and potential for bias in data collection. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly the second wave which occurred during the final years of the study may have influenced our findings. The pandemic likely led to changes in healthcare-seeking behavior, hospital admissions, and antibiotic prescribing practices, which could have impacted the incidence and characteristics of EB cases included in our study. Moreover, there are inherent differences between patients prone to bacteremia caused by E. faecium and those prone to E. faecalis, including underlying comorbidities, immune status, and healthcare exposures, among others. Additionally, our study was conducted at a single tertiary care center, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other healthcare settings or populations. Despite these limitations, our study provides valuable insights into the epidemiology and clinical characteristics of enterococcal bacteremia, contributing to the existing body of literature on this topic. Future research, including prospective studies and multi-center collaborations, is warranted to further elucidate the factors influencing the incidence and outcomes of enterococcal bacteremia and to inform evidence-based interventions for its prevention and management.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study reveals an upward trend in the proportion of bacteraemia caused by E. faecium over the study period of 2015 to 2021. Although the reasons for this shift remain unclear, one possible contributing factor could be changes in antibiotic usage patterns. Notably, our analysis identified three independent variables associated with a higher likelihood of acquiring EfmB compared to EfsB. These variables include nosocomial infection and prior exposure to either pip/taz or meropenem within 90 days before the diagnosis of EfmB.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, U.S.M.; formal analysis, G.A., E.S. U.S.M; data curation, G.A, E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, G.A.; writing—review and editing, E.S, U.S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No external funding

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Anna Stoopendahl, senior pharmacist at Sahlgrenska University Hospital, for her assistance in data extraction and creating one of the figures for this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chenoweth, C.; Schaberg, D. The epidemiology of enterococci. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1990, 9, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jubeh, B.; Breijyeh, Z.; Karaman, R. Resistance of Gram-Positive Bacteria to Current Antibacterial Agents and Overcoming Approaches. Molecules 2020, 25, 2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folkhälsomyndigheten. Swedres-Svarm 2022 2022 [Available from: https://www.sva.se/media/ticcp2zu/swedres-svarm-2022-edit-230808.pdf.

- Kristich CJ RL, Arias CA. Enterococcal Infection—Treatment and Antibiotic Resistance.. In: Gilmore MS CD, Ike, Y., et al., editors, editor. Enterococci: From Commensals to Leading Causes of Drug Resistant Infection [Internet]. Boston: Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary2014 Feb 6.

- Cabiltes, I.; Coghill, S.; Bowe, S.J.; Athan, E. Enterococcal bacteraemia ‘silent but deadly’: a population-based cohort study. Intern Med J. 2020, 50, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinholt, M.; Østergaard, C.; Arpi, M.; Bruun, N.; Schønheyder, H.; Gradel, K.; Søgaard, M.; Knudsen, J. Incidence, clinical characteristics and 30-day mortality of enterococcal bacteraemia in Denmark 2006–2009: a population-based cohort study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 20, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBride, S.J.; Upton, A.; Roberts, S.A. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with vancomycin-susceptible Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium bacteraemia—a five-year retrospective review. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2010, 29, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lytsy, B.; Sandegren, L.; Tano, E.; Torell, E.; Andersson, D.I.; Melhus, A. The first major extended-spectrum beta-lactamase outbreak in Scandinavia was caused by clonal spread of a multiresistant Klebsiella pneumoniae producing CTX-M-15. Apmis 2008, 116, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- STRAMA. 10-punktsprogram mot antibiotikaresistens inom.

- vård och omsorg 2022 [Available from: https://strama.se/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/10-punktsprogrammet-uppdaterad-kort-version-juni-2022.pdf.

- Horner, C.; Mushtaq, S.; Allen, M.; Hope, R.; Gerver, S.; Longshaw, C.; Reynolds, R.; Woodford, N.; Livermore, D.M. Replacement of Enterococcus faecalis by Enterococcus faecium as the predominant enterococcus in UK bacteraemias. JAC-Antimicrobial Resist. 2021, 3, dlab185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lester, C.H.; Sandvang, D.; Olsen, S.S.; Schønheyder, H.C.; Jarløv, J.O.; Bangsborg, J.; Hansen, D.S.; Jensen, T.G.; Frimodt-Møller, N.; Hammerum, A.M.; et al. Emergence of ampicillin-resistant Enterococcus faecium in Danish hospitals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008, 62, 1203–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Top, J.; Willems, R.; Blok, H.; de Regt, M.; Jalink, K.; Troelstra, A.; Goorhuis, B.; Bonten, M. Ecological replacement of Enterococcus faecalis by multiresistant clonal complex 17 Enterococcus faecium. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2007, 13, 316–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Top, J.; Willems, R.; Bonten, M. Emergence of CC17Enterococcus faecium: from commensal to hospital-adapted pathogen. FEMS Immunol. Med Microbiol. 2008, 52, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piezzi, V.; Gasser, M.; Atkinson, A.; Kronenberg, A.; Vuichard-Gysin, D.; Harbarth, S.; Marschall, J.; Buetti, N.; on behalf of the Swiss Centre for Antibiotic Resistance (ANRESIS). Increasing proportion of vancomycin resistance among enterococcal bacteraemias in Switzerland: a 6-year nation-wide surveillance, 2013 to 2018. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25, 1900575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, H.; Hase, R.; Otsuka, Y.; Hosokawa, N. A 10-year profile of enterococcal bloodstream infections at a tertiary-care hospital in Japan. J. Infect. Chemother. 2017, 23, 390–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endtz, H.P.; van Dijk, W.C.; Verbrugh, H.A. Comparative in-vitro activity of meropenem against selected pathogens from hospitalized patients in The Netherlands. MASTIN Study Group. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1997, 39, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).