Submitted:

10 June 2024

Posted:

11 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design

4.2. Definitions

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022 Feb 12;399(10325):629-655. [CrossRef]

- Yigit, Hesna, et al. "Novel carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase, KPC-1, from a carbapenem-resistant strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae." Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 45.4 (2001): 1151-1161.

- Lee, Chang-Ro et al. “Global Dissemination of Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: Epidemiology, Genetic Context, Treatment Options, and Detection Methods.” Frontiers in microbiology vol. 7 895. 13 Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Voulgari, Evangelia, et al. "The Balkan region: NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST11 clonal strain causing outbreaks in Greece." Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 69.8 (2014): 2091-2097.

- Spyropoulou, Aikaterini, et al. "The first NDM metallo-β-lactamase producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate in a University Hospital of Southwestern Greece." Journal of Chemotherapy 28.4 (2016): 350-351.

- Robert A Bonomo, Eileen M Burd, John Conly, Brandi M Limbago, Laurent Poirel, Julie A Segre, Lars F Westblade, Carbapenemase-Producing Organisms: A Global Scourge, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 66, Issue 8, 15 April 2018, Pages 1290–1297.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Antimicrobial resistance in the EU/EEA (EARS-Net) - Annual Epidemiological Report 2022. Stockholm: ECDC; 2023.

- Giakkoupi P, Tryfinopoulou K, Kontopidou F, Tsonou P, Golegou T, Souki H, Tzouvelekis L, Miriagou V, Vatopoulos A. Emergence of NDM-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Greece. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013 Dec;77(4):382-4. [CrossRef]

- Polemis M, Mandilara G, Pappa O, et al. COVID-19 and Antimicrobial Resistance: Data from the Greek Electronic System for the Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance-WHONET-Greece (January 2018-March 2021). Life (Basel). 2021 Sep 22;11(10):996. [CrossRef]

- Tryfinopoulou K, Linkevicius M, Pappa O, Alm E, Karadimas K, Svartström O, Polemis M, Mellou K, Maragkos A, Brolund A, Fröding I, David S, Vatopoulos A, Palm D, Monnet DL, Zaoutis T, Kohlenberg A; Greek CCRE study group; Members of the Greek CCRE study group. Emergence and persistent spread of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae high-risk clones in Greek hospitals, 2013 to 2022. Euro Surveill. 2023 Nov;28(47):2300571. [CrossRef]

- The Lancet. Antimicrobial resistance: an agenda for all. Lancet. 2024 Jun 1;403(10442):2349. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Minggui et al. “Clinical outcomes and bacterial characteristics of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae complex among patients from different global regions (CRACKLE-2): a prospective, multicentre, cohort study.” The Lancet. Infectious diseases vol. 22,3 (2022): 401-412. [CrossRef]

- Falcone M, Tiseo G, Carbonara S, et al. Mortality Attributable to Bloodstream Infections Caused by Different Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacilli: Results From a Nationwide Study in Italy (ALARICO Network). Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76(12):2059-2069. [CrossRef]

- Reyes J, Komarow L, Chen L, et al. Global epidemiology and clinical outcomes of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and associated carbapenemases (POP): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Microbe. 2023;4(3):e159-e170. [CrossRef]

- Baek, M.S., Kim, J.H., Park, J.H. et al. Comparison of mortality rates in patients with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales bacteremia according to carbapenemase production: a multicenter propensity-score matched study. Sci Rep 14, 597 (2024). [CrossRef]

- CDC/NHSN surveillance definitions for specific types of infections. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/PDFs/pscManual/17pscNosInfDef_current.pdf. Accessed 1 December 2023.

- Protonotariou, Efthymia et al. “Polyclonal Endemicity of Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in ICUs of a Greek Tertiary Care Hospital.” Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland) vol. 11,2 149. 25 Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Iacchini, Simone et al. “Bloodstream infections due to carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Italy: results from nationwide surveillance, 2014 to 2017.” Euro surveillance : bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin vol. 24,5 (2019): 1800159. [CrossRef]

- Cristina ML, Alicino C, Sartini M, et al. Epidemiology, management, and outcome of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infections in hospitals within the same endemic metropolitan area. J Infect Public Health. 2018;11(2):171-177. [CrossRef]

- Alicino C, Giacobbe DR, Orsi A, et al. Trends in the annual incidence of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infections: a 8-year retrospective study in a large teaching hospital in northern Italy. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:415. Published 2015 Oct 13. [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou-Olivgeris M, Bartzavali C, Karachalias E, et al. A Seven-Year Microbiological and Molecular Study of Bacteremias Due to Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae: An Interrupted Time-Series Analysis of Changes in the Carbapenemase Gene's Distribution after Introduction of Ceftazidime/Avibactam. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022;11(10):1414. Published 2022 Oct 14. [CrossRef]

- Falcone M, Giordano C, Leonildi A, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of infections caused by metallo-β-lactamases producing Enterobacterales: a 3-year prospective study from an endemic area. Clin Infect Dis. Published online November 30, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Falcone M, Daikos GL, Tiseo G, et al. Efficacy of Ceftazidime-avibactam Plus Aztreonam in Patients With Bloodstream Infections Caused by Metallo-β-lactamase-Producing Enterobacterales. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(11):1871-1878. [CrossRef]

- Paul M, Carrara E, Retamar P, et al. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) guidelines for the treatment of infections caused by multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacilli (endorsed by European Society of Intensive Care Medicine). Clin Microbiol Infect 2022; 28:521–47.

- Tamma PD, Aitken SL, Bonomo RA, Mathers AJ, van Duin D, Clancy CJ. Infectious Diseases Society of America 2023 guidance on the treatment of antimicrobial resistant gram-negative infections. Clin Infect Dis 2023. [CrossRef]

- Tiseo G, Brigante G, Giacobbe DR, et al. Diagnosis and management of infections caused by multidrug-resistant bacteria: guideline endorsed by the Italian Society of Infection and Tropical diseases (SIMIT), the Italian Society of Anti-infective Therapy (SITA), the Italian Group for Antimicrobial stewardship (GISA), the Italian Association of Clinical Microbiologists (AMCLI) and the Italian Society of Microbiology (SIM). Int J Antimicrob Agents 2022; 60:106611.

- Shields RK, Nguyen MH, Chen L, et al. Ceftazidime-avibactam is superior to other treatment regimens against carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017; 61:8.

- van Duin D, Lok JJ, Earley M, et al. ; Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group. Colistin versus ceftazidime-avibactam in the treatment of infections due to carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66:163–71.

- Jorgensen SCJ, Trinh TD, Zasowski EJ, et al. Real-world experience with ceftazidime-avibactam for multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019; 6:ofz522.

- Tumbarello M, Raffaelli F, Giannella M, et al. Ceftazidime-Avibactam Use for Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase-Producing K. pneumoniae Infections: A Retrospective Observational Multicenter Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(9):1664-1676. [CrossRef]

- Papp-Wallace KM, Barnes MD, Taracila MA, et al. The Effectiveness of Imipenem-Relebactam against Ceftazidime-Avibactam Resistant Variants of the KPC-2 β-Lactamase. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023;12(5):892. Published 2023 May 11. [CrossRef]

- Shields RK, McCreary EK, Marini RVet al.. Early experience with meropenem-vaborbactam for treatment of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 71: 667–71.

| Total N=118 |

Pseudomonas NDM N=17 |

CREs NDM N=29 |

CREs KPC N=72 |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender | 71 (60.2) | 9 (52.9) | 20 (69) | 42 (58.3) | 0.495 | |

| Age (years) | 67.8±14.7 | 73.1±13.8 | 73±15.7 | 64.5±13.7 | 0.009 | |

| Cancer history | 53 (44.9) | 3 (17.6) | 9 (31) | 41 (56.9) | 0.003 | |

| LOS before index culture (days) | 7 [1–19] | 11 [1–20] | 1 [0–6] | 12 [2–25] | 0.011 | |

| Ward | 0.031 | |||||

| Medical | 88 (74.6) | 11 (64.7) | 23 (79.3) | 54 (75) | ||

| Surgical | 19 (16.1) | 1 (5.9) | 4 (13.8) | 14 (19.4) | ||

| ICU | 11 (9.3) | 5 (29.4) | 2 (6.9) | 4 (5.5) | ||

| Hospital acquired infection | 93 (78.8) | 2 (11.8) | 20 (69) | 58 (80.6) | 0.257 | |

| Central venous catheter | 65 (55.1) | 10 (71.4) | 14 (70) | 41 (71.9) | 0.987 | |

| Foley catheter | 67 (56.8) | 13 (92.9) | 15 (75) | 39 (68.4) | 0.175 | |

| Mechanical ventilation | 14 (11.9) | 5 (33.3) | 4 (20) | 5 (8.5) | 0.042 | |

| Previously in ICU | 20 (16.9) | 6 (35.3) | 4 (13.8) | 10 (13.9) | 0.093 | |

| Antibiotic resistance | ||||||

| Colistin | 37 (31.4) | 1 (5.9) | 15 (51.7) | 21 (29.2) | 0.004 | |

| Meropenem | 116 (98.3) | 17 (100) | 28 (96.6) | 71 (98.6) | 0.648 | |

| Aztreonam | 107 (90.7) | 10 (58.8) | 25 (86.2) | 72 (100) | <0.001 | |

| Treatment | ||||||

| Colimycin | 57 (48.3) | 15 (88.2) | 19 (65.5) | 23 (31.9) | <0.001 | |

| Ceftolozane/ tazobactam | 3 (2.5) | 1 (5.9) | 1 (3.4) | 1 (1.4) | 0.536 | |

| Meropenem | 20 (16.9) | 7 (41.2) | 7 (24.1) | 6 (8.3) | 0.003 | |

| Ceftazidime/ avibactam | 49 (41.5) | 3 (17.6) | 1 (3.4) | 45 (62.5) | <0.001 | |

| Meropenem/ vaborbactam | 10 (8.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (6.9) | 8 (11.1) | 0.315 | |

| Imipenem/ relebactam | 5 (4.2) | 1 (5.9) | 3 (10.3) | 1 (1.4) | 0.121 | |

| Tigecycline | 15 (12.7) | 1 (5.9) | 7 (24.1) | 7 (9.7) | 0.095 | |

| Active Drugs | 0.001 | |||||

| None | 28 (23.7) | 2 (11.8) | 14 (48.3) | 12 (16.7) | ||

| One | 71 (60.2) | 15 (88.2) | 10 (34.5) | 46 (63.9) | ||

| Two | 19 (16.1) | 0 (0) | 5 (17.2) | 14 (19.4) | ||

| Laboratory values | ||||||

| White blood cells (103/μl) | 8.1 [3-16.2] | 8.2 [4-16.4] | 11.9 [5.2-22.1] | 7.3 [1.4-13.4] | 0.071 | |

| Neutrophils (103/μl) | 6.7 [2.2-14.2] | 6.6 [2.4-14.6] | 11.2 [4.5-18] | 5.6 [1-12.3] | 0.067 | |

| Neutropenia | 23 (19.5) | 2 (11.8) | 3 (10.3) | 18 (25) | 0.167 | |

| Gamma globulins (g/l) | 9.8 [6.8-13] | 10 [7.7-12] | 10 [6.7-16] | 9.7 [6.1-13] | 0.713 | |

| Hypogamma-globulinemia | 24 (20.3) | 1 (11.1) | 6 (31.6) | 17 (31.5) | 0.447 | |

| Albumin (g/l) | 27.1 [22.9-32.3] | 27.3 [23.8-33] | 26.8 [23-33.9] | 27.1 [22.2-32] | 0.845 | |

| Recurrence of Bacteremia | 10 (8.5) | 2 (11.8) | 2 (6.9) | 6 (8.3) | 0.847 | |

| LOS after culture (days) | 13 [3–24] | 14 [4–31] | 12 [3–26] | 14 [5-24] | 0.976 | |

| Total LOS (days) | 24 [12-43] | 23 [15-49] | 18 [9-37] | 25 [13-46] | 0.523 | |

| In-hospital mortality | 61 (51.7) | 12 (70.6) | 15 (51.7) | 34 (47.2) | 0.222 | |

| 30-day mortality | 48 (40.7) | 8 (47.1) | 12 (41.4) | 28 (38.9) | 0.824 | |

| Survivors N=19 |

Non-Survivors N=27 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender | 12 (63.2) | 17 (63) | 1 |

| Age (years) | 74.5±15.2 | 72±14.9 | 0.579 |

| Cancer history | 7 (36.8) | 5 (18.5) | 0.19 |

| LOS before index culture (days) | 1 [0-8] | 4 [1-15] | 0.261 |

| Ward | 0.05 | ||

| Medical | 17 (89.5) | 17 (63) | |

| Surgical | 2 (10.5) | 3 (11.1) | |

| ICU | 0 (0) | 7 (25.9) | |

| Hospital acquired infection | 13 (68.4) | 22 (81.5) | 0.484 |

| Central venous catheter | 5 (38.5) | 19 (90.5) | 0.002 |

| Foley catheter | 7 (58.3) | 21 (95.5) | 0.014 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 0 (0) | 9 (40.9) | 0.013 |

| Previously in ICU | 1 (5.3) | 9 (33.3) | 0.031 |

| Bacterial isolate | 0.235 | ||

| Pseudomonas | 5 (26.3) | 12 (44.4) | |

| Enterobacterales | 14 (73.7) | 15 (55.6) | |

| Antibiotic resistance | |||

| Colistin | 8 (42.1) | 8 (29.6) | 0.531 |

| Meropenem | 19 (100) | 26 (96.3) | 1 |

| Aztreonam | 11 (57.9) | 24 (88.9) | 0.032 |

| Treatment | |||

| Colimycin | 14 (73.7) | 20 (74.1) | 1 |

| Ceftolozane/ tazobactam | 1 (5.3) | 1 (3.7) | 1 |

| Meropenem | 5 (26.3) | 9 (33.3) | 0.749 |

| Ceftazidime/ avibactam | 2 (10.5) | 2 (7.4) | 1 |

| Meropenem/ vaborbactam | 0 (0) | 2 (7.4) | 0.504 |

| Imipenem/ relebactam | 1 (5.3) | 3 (11.1) | 0.632 |

| Tigecycline | 3 (15.8) | 5 (18.5) | 1 |

| Active Drugs | 0.970 | ||

| None | 7 (36.8) | 9 (33.3) | |

| One | 10 (52.6) | 15 (55.6) | |

| Two | 2 (10.5) | 3 (11.1) | |

| Laboratory values | |||

| White blood cells (103/μl) | 9.9 [5.1-18.1] | 10.3 [4.2-20.5] | 0.885 |

| Neutrophils (103/μl) | 8.6 [4.5-15.9] | 8.6 [2.5-17.9] | 0.964 |

| Neutropenia | 1 (5.3) | 4 (14.8) | 0.387 |

| Gamma globulins (g/l) | 11 [6.6-13.3] | 9.6 [7.2-20] | 0.872 |

| Hypogammaglobulinemia | 4 (28.6) | 3 (21.4) | 1 |

| Albumin (g/l) | 31.3 [24.3-36.6] | 25.3 [22.4-29.5] | 0.029 |

| Recurrence of Bacteremia | 1 (5.3) | 3 (11.1) | 0.632 |

| LOS after culture (days) | 16 [10-21] | 9 [2-33] | 0.32 |

| Total LOS (days) | 20 [10-33] | 23 [12-63] | 0.482 |

| Survivors N=38 |

Non-Survivors N=34 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender | 21 (55.3) | 21 (61.8) | 0.637 |

| Age (years) | 62.7±11.3 | 66.5±15.9 | 0.244 |

| Cancer history | 21 (55.3) | 20 (58.8) | 0.815 |

| LOS before index culture (days) | 9 [1-18] | 13 [4-31] | 0.057 |

| Ward | 0.186 | ||

| Medical | 27 (71.1) | 27 (79.4) | |

| Surgical | 10 (26.3) | 4 (11.8) | |

| ICU | 1 (2.6) | 3 (8.8) | |

| Hospital acquired infection | 27 (71.1) | 31 (91.2) | 0.039 |

| Central venous catheter | 16 (59.3) | 25 (83.3) | 0.075 |

| Foley catheter | 15 (55.6) | 24 (80) | 0.086 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 1 (3.7) | 4 (12.5) | 0.362 |

| Previously in ICU | 5 (13.2) | 5 (14.7) | 1 |

| Antibiotic resistance | |||

| Colistin | 8 (21.1) | 13 (38.2) | 0.127 |

| Meropenem | 38 (100) | 33 (97.1) | 0.472 |

| Treatment | |||

| Colimycin | 9 (23.7) | 14 (41.2) | 0.134 |

| Ceftolozane/tazobactam | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Meropenem | 3 (7.9) | 3 (8.8) | 1 |

| Ceftazidime/avibactam | 30 (78.9) | 15 (44.1) | 0.003 |

| Meropenem/vaborbactam | 4 (10.5) | 4 (11.8) | 1 |

| Imipenem/ relebactam | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | 0.472 |

| Tigecycline | 2 (5.3) | 5 (14.7) | 0.243 |

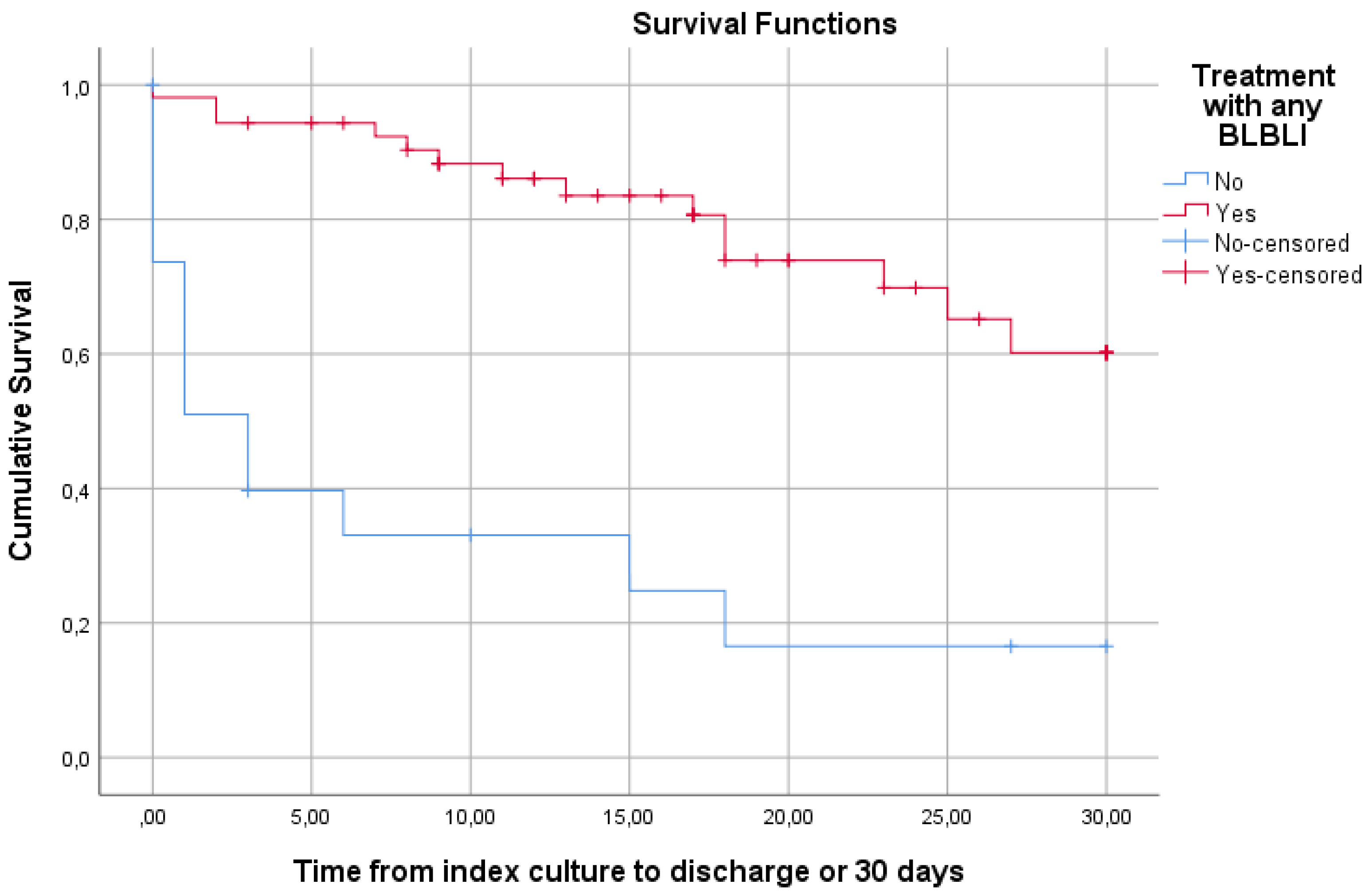

| Any BLBLI | 33 (86.8) | 20 (58.8) | 0.009 |

| Active Drugs | 0.083 | ||

| None | 3 (7.9) | 9 (26.5) | |

| One | 28 (73.7) | 18 (52.9) | |

| Two | 7 (18.4) | 7 (20.6) | |

| BLBLI monotherapy | 27 (81.8) | 13 (65) | 0.2 |

| Laboratory values | |||

| White blood cells (103/μl) | 8.2 [4.6-12.2] | 4.8 [0.8-15.4] | 0.391 |

| Neutrophils (103/μl) | 6.7 [3.4-10.9] | 3.9 [0.5-14.2] | 0.369 |

| Neutropenia | 7 (18.4) | 11 (32.4) | 0.188 |

| Gamma globulins (g/l) | 10.5 [8.1-17] | 8.3 [5.9-11] | 0.098 |

| Hypogammaglobulinemia | 5 (19.2) | 12 (42.9) | 0.082 |

| Albumin (g/l) | 30 [24.1-33.7] | 24.1 [20.4-30.8] | 0.011 |

| Recurrence of Bacteremia | 3 (7.9) | 3 (8.8) | 1 |

| LOS after culture (days) | 17 [10-25] | 9 [1-24] | 0.045 |

| Length of stay (days) | 23 [17-33] | 28 [9-55] | 0.743 |

| NDM N=54(%) | KPC N=79(%) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microbes | <0.001 | |||

| P. aeruginosa | 23 (42.6) | 0 (0) | ||

| K. pneumoniae | 30 (55.6) | 76 (95.2) | ||

| E. coli | 1 (1.9) | 2 (2.5) | ||

| K. aerogenes | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) | ||

| Antibiotic resistance | ||||

| Colistin | 17 (31.5) | 22 (27.8) | 0.7 | |

| Meropenem | 53 (98.1) | 78 (98.7) | 1 | |

| Aztreonam | 42 (77.8) | 79 (100) | <0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).