Submitted:

08 July 2024

Posted:

08 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Instrumentation and Methodology

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Instrumentation

2.3. Computational Techniques and Description

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Clustering Analysis

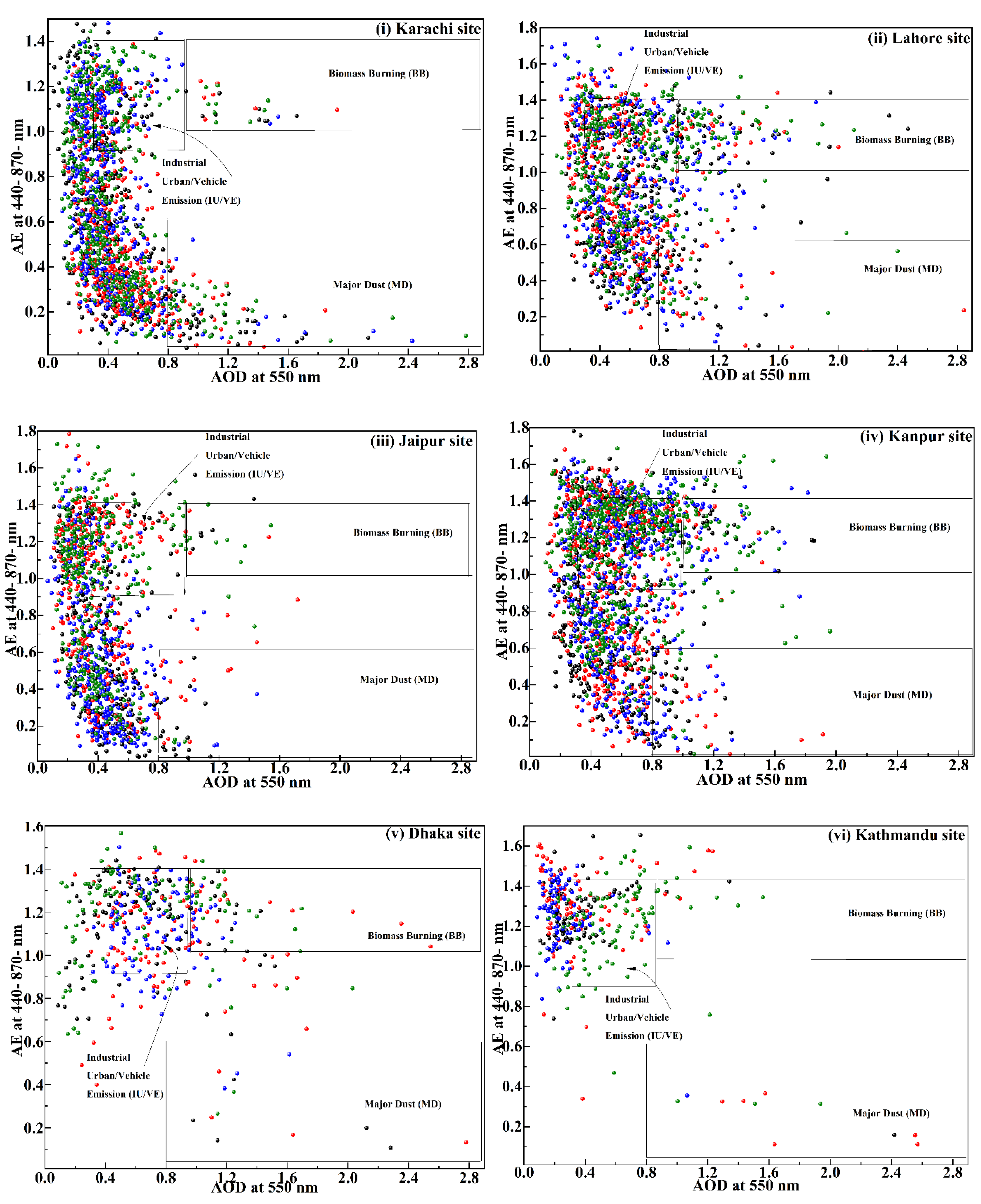

3.1.1. AOD and AE

| Location | AOD | AE | Aerosol Type | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Asia | 0.8 – 2.9 | 0.01 – 0.6 | Major Dust (MD) | current study |

| 0.3 – 0.9 | 0.9 – 1.4 | Industrial Urban (IU)/VE | ||

| 0.9 – 2.9 | 1 – 1.4 | Biomass Burning (BB) | ||

| Nanjing | < 0.2 | 1.0 > | Clean continental | Kumar et al. (2018) [52] |

| < 0.2 | < 0.6 | Marine | Kumar et al. (2018) [52] | |

| > 0.3 | 1.0 > | Biomass Burning/Urban Industrial | Kumar et al. (2018) [52] | |

| 0.5 > | < 0.7 | Desert Dust | Kumar et al. (2018) [52] | |

| Varanasi | 0.7 >刘0.3 – 0.7刘0.3 – 1.0刘1.0 > | < 0.6刘< 0.9刘0.9 >刘1.0 > | Mostly Dust (MD)刘Polluted continental (PC)刘Anthropogenic Aerosol刘Biomass Burning (BB) | Tiwari et al. (2015) [53]. |

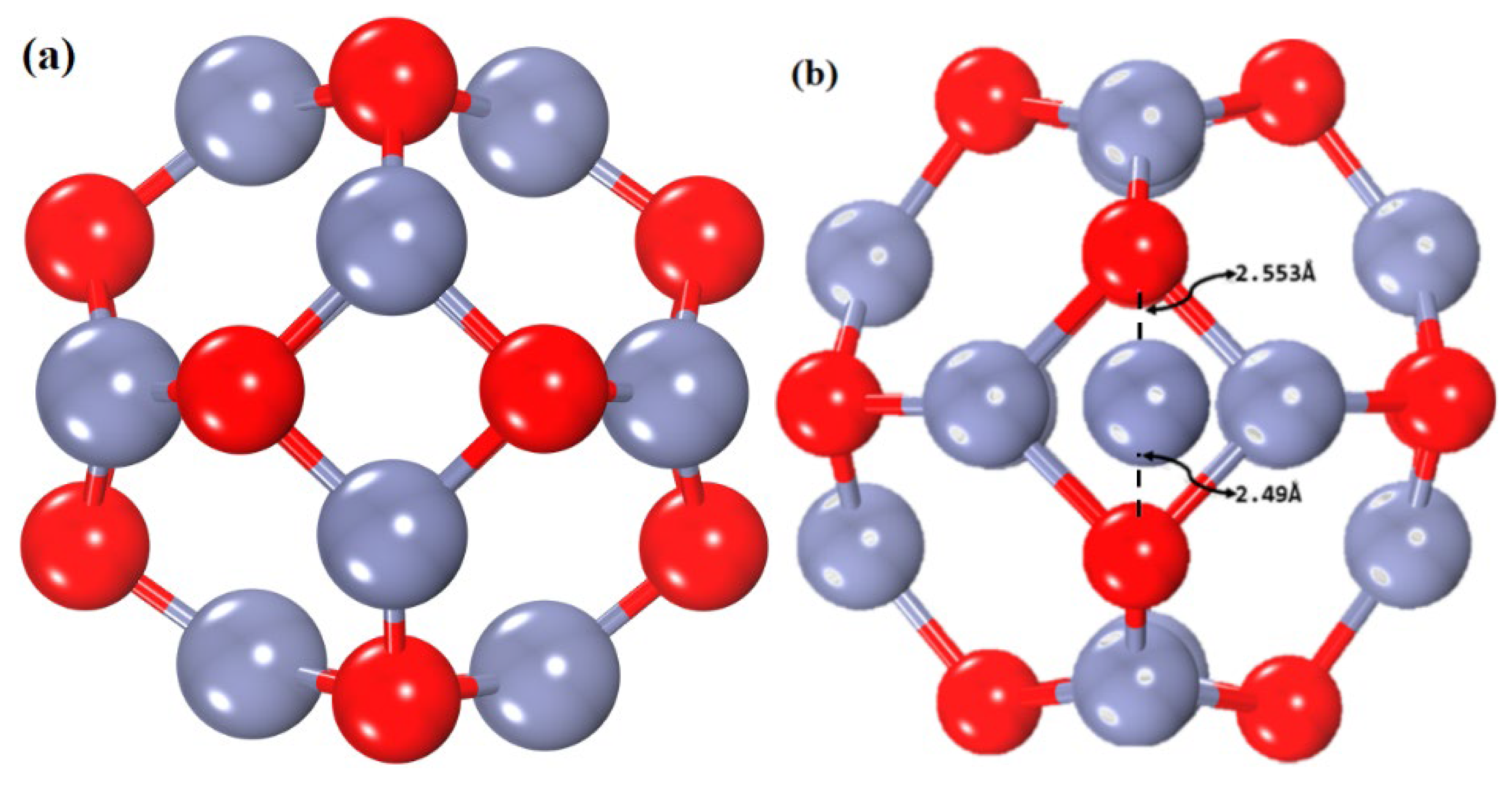

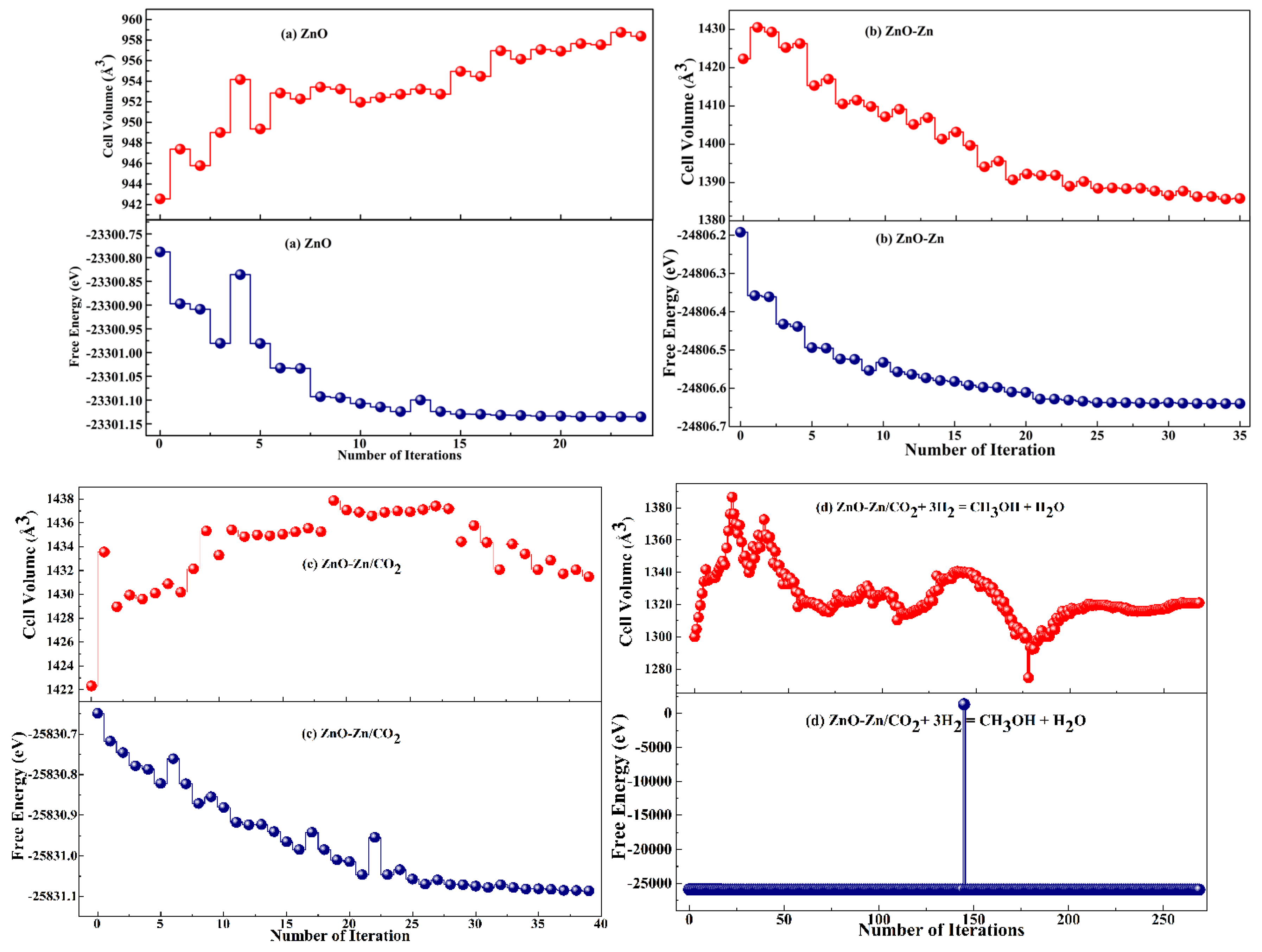

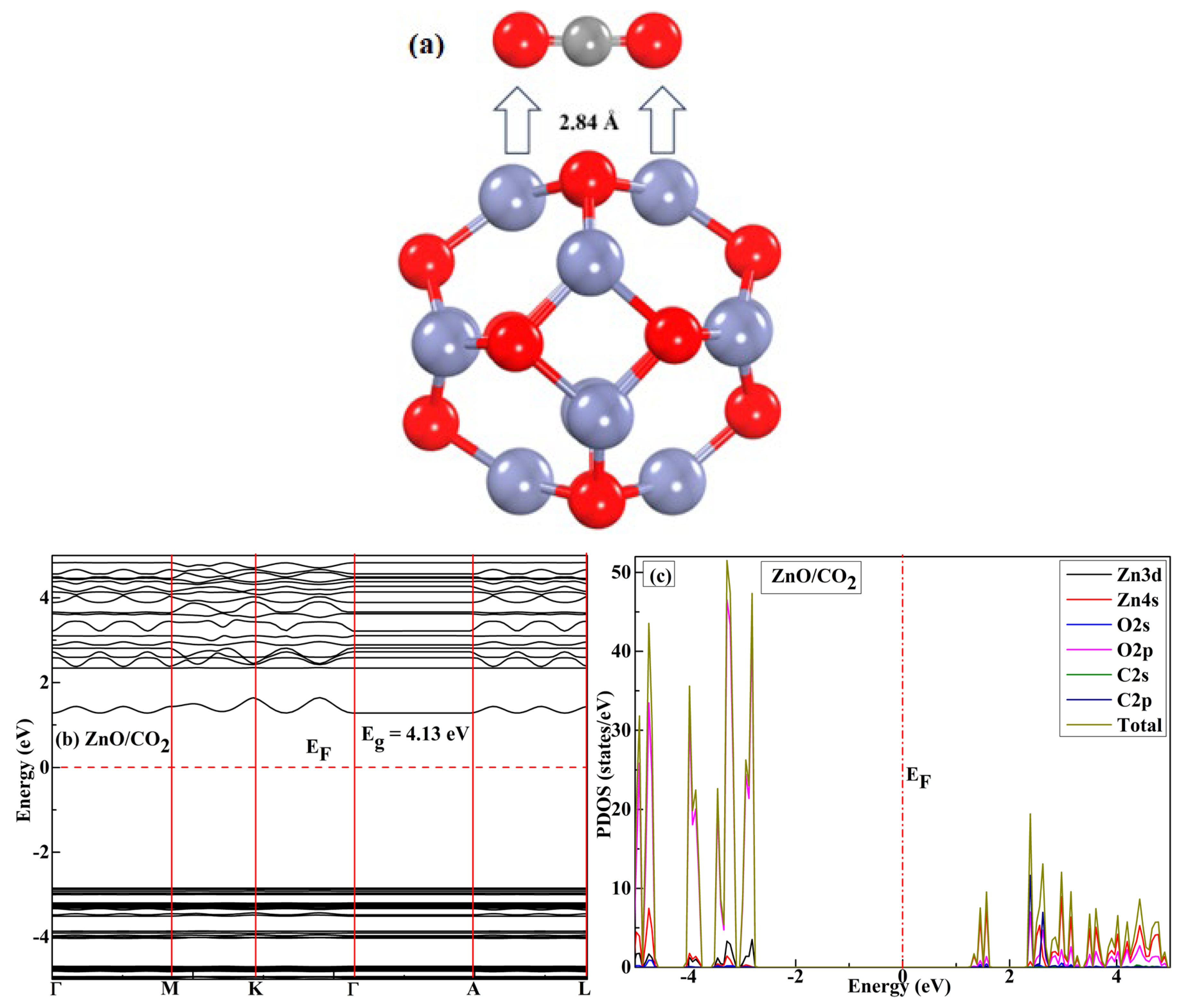

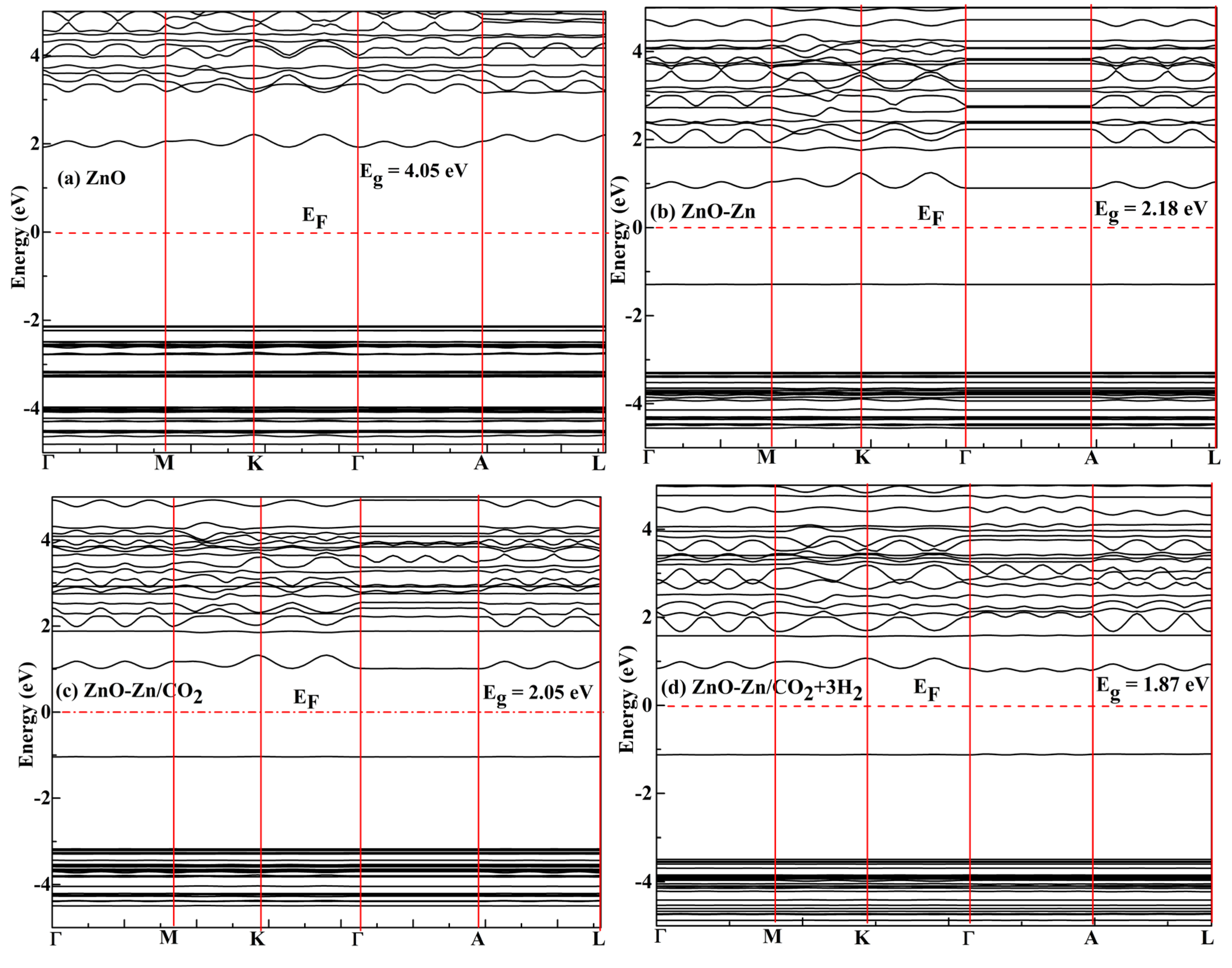

3.2. Geometrical Study of Pristine and Zn-Decorated ZnO Nanocages

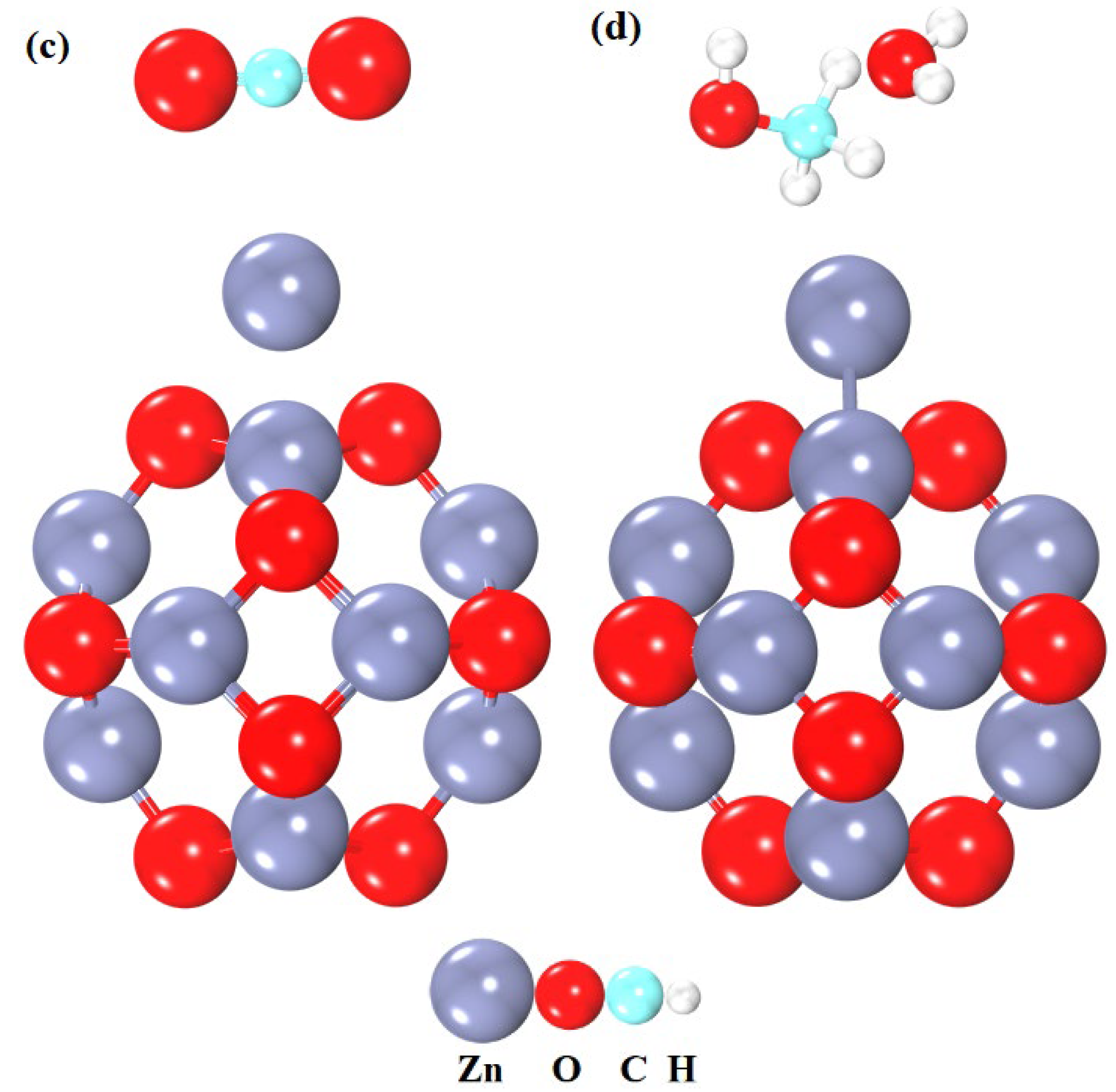

3.3. Adsorption Energies for CO2 Gas and Complex on the ZnO–Zn Nanocage

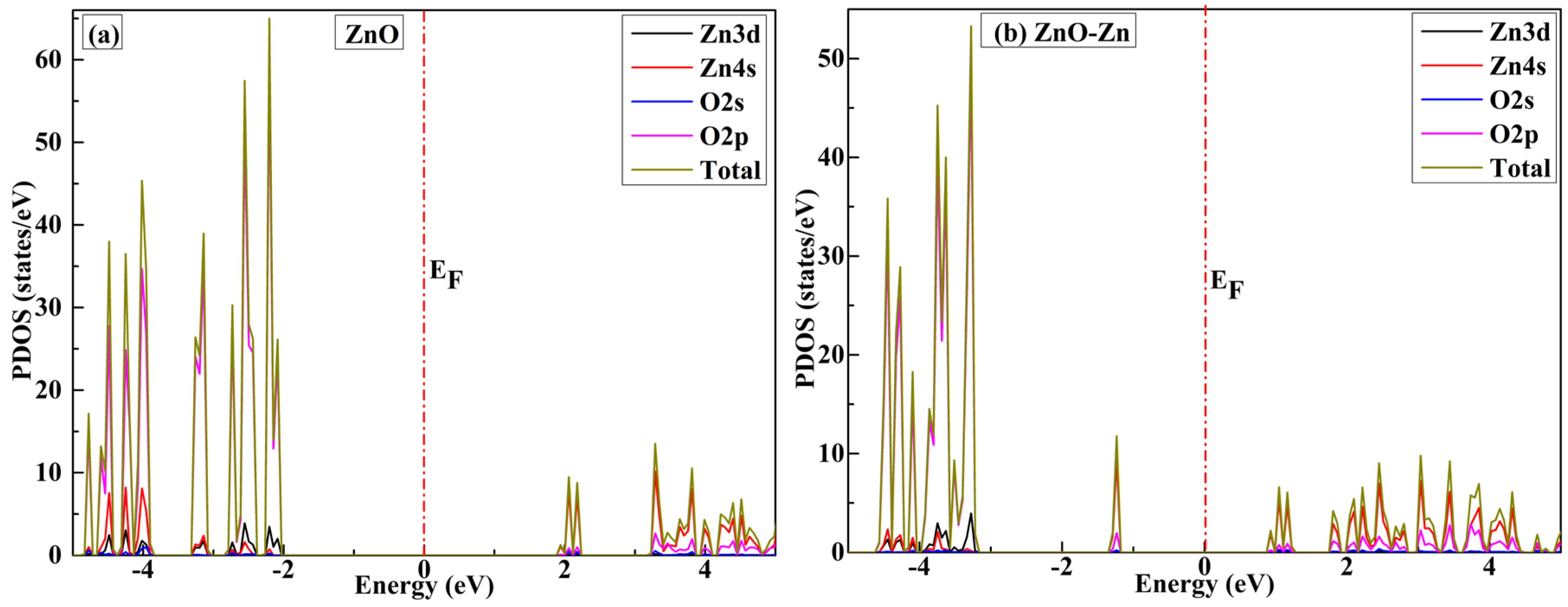

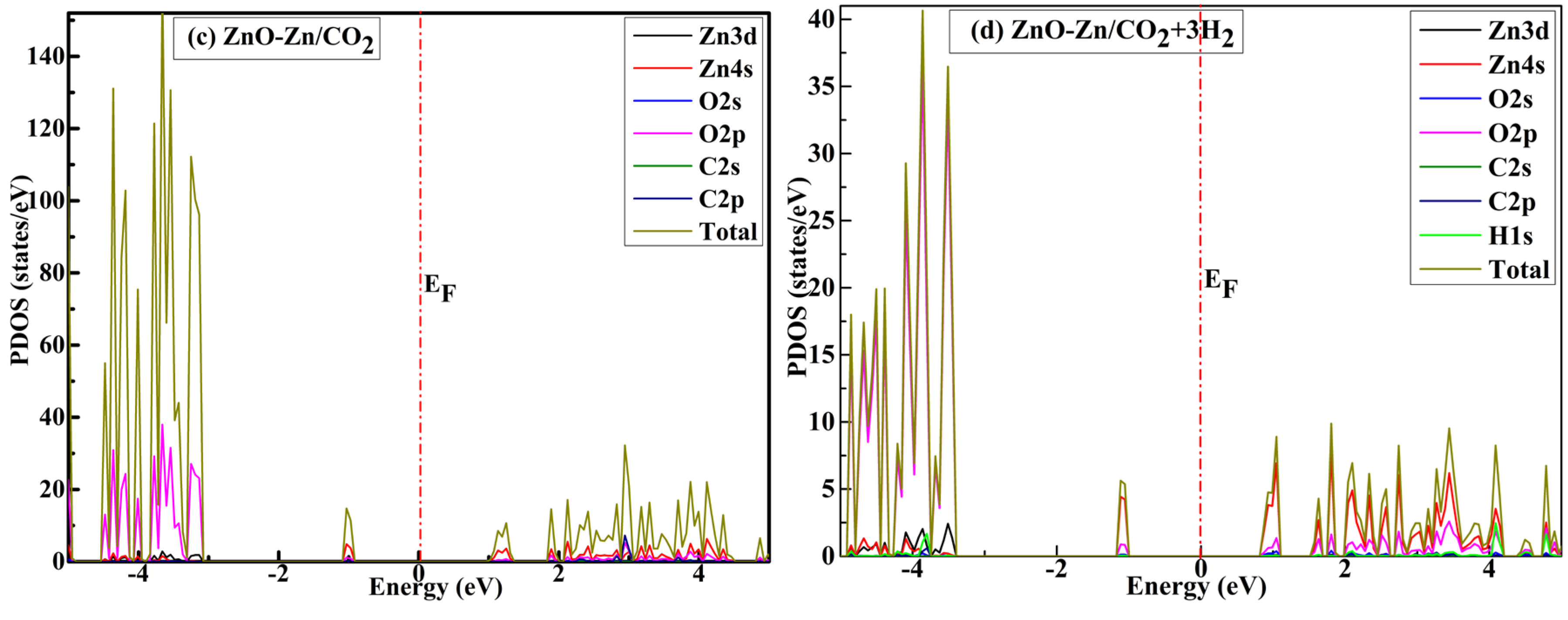

3.4. Molecular-Level Analysis of Orbitals

3.5. ZnO–Zn Nanocage Sensitivity

3.6. Conductivity of the ZnO–Zn Nanocage

3.7. Recovery Time

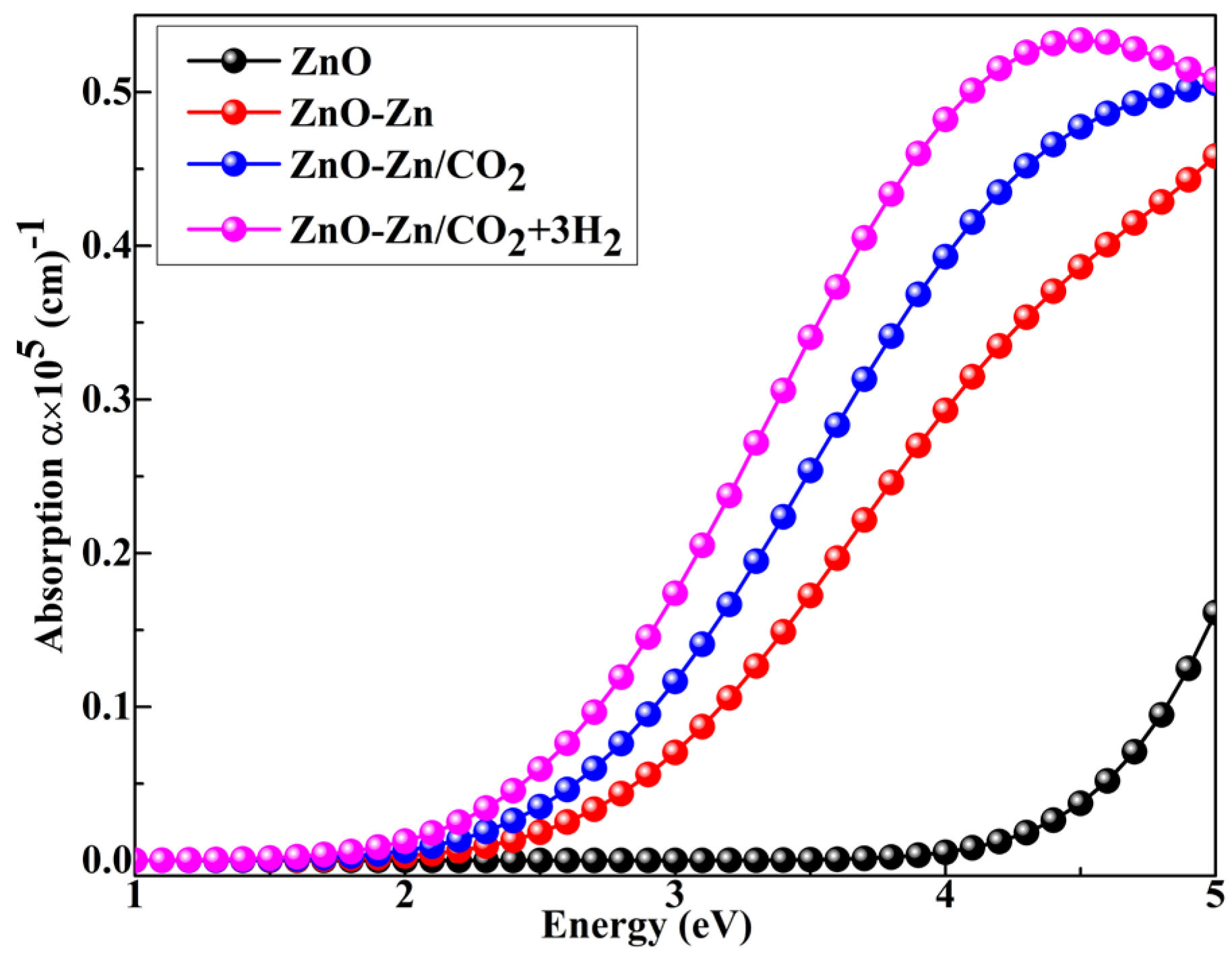

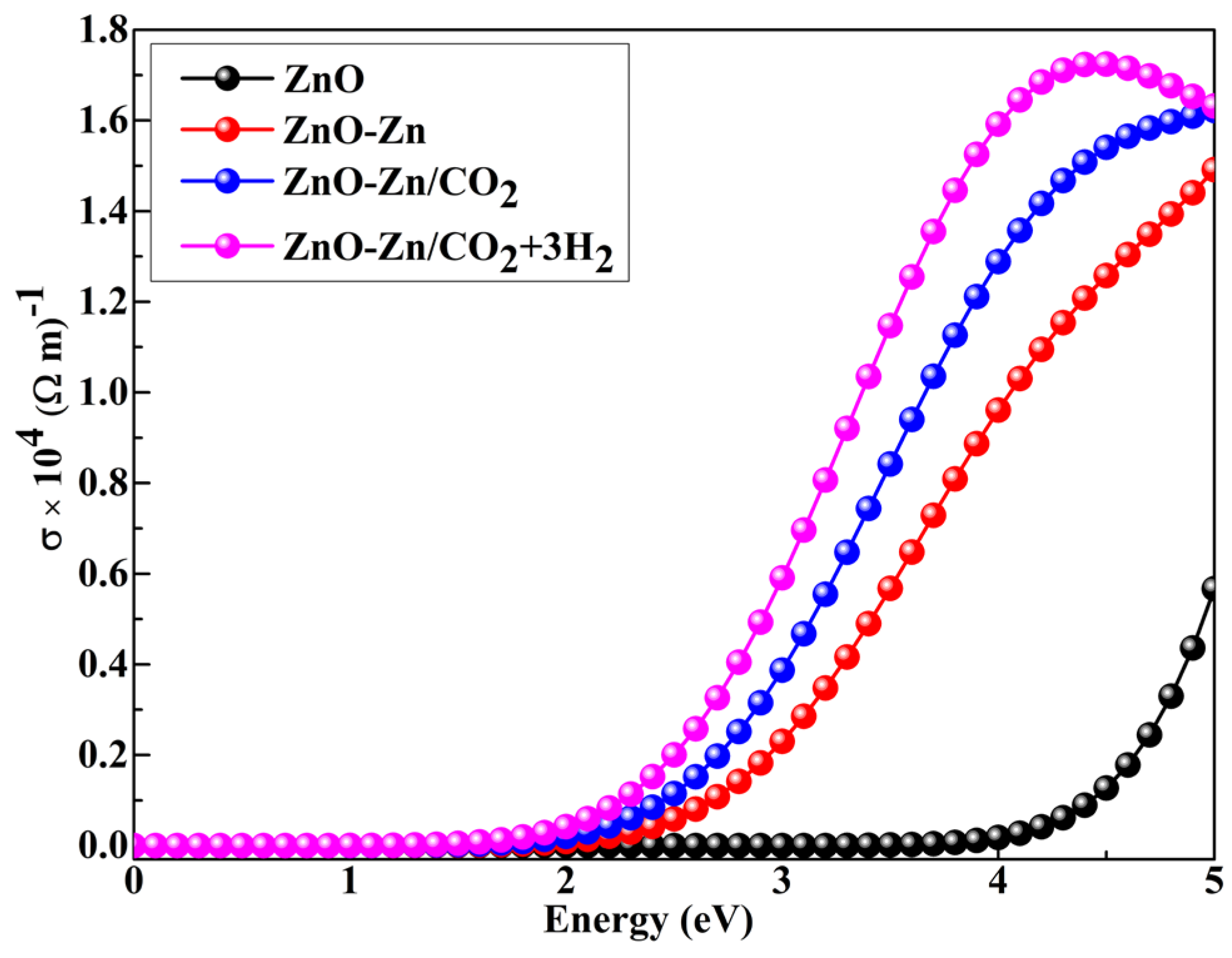

3.8. Optical Property Calculations of the Zn-Decorated ZnO Nanocage

3.9. Quantum-Molecular Explanation

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bibi, H.; Alam, K.; Blaschke, T.; Bibi, S.; Iqbal, M.J. Long-term (2007–2013) analysis of aerosol optical properties over four locations in the Indo-Gangetic plains. Applied optics 2016, 55, 6199–6211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, H.; Alam, K.; Chishtie, F.; Bibi, S.; Shahid, I.; Blaschke, T. Intercomparison of MODIS, MISR, OMI, and CALIPSO aerosol optical depth retrievals for four locations on the Indo-Gangetic plains and validation against AERONET data. Atmospheric Environment 2015, 111, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dabbas, M.A.; Abbas, M.A.; Al-Khafaji, R.M. Dust storms loads analyses—Iraq. Arabian Journal of Geosciences 2012, 5, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, H.; Alam, K.; Bibi, S. In-depth discrimination of aerosol types using multiple clustering techniques over four locations in Indo-Gangetic plains. Atmospheric Research 2016, 181, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higurashi, A.; Nakajima, T. Detection of aerosol types over the East China Sea near Japan from four-channel satellite data. Geophysical research letters 2002, 29, 17–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arola, A.; Schuster, G.; Myhre, G.; Kazadzis, S.; Dey, S.; Tripathi, S. Inferring absorbing organic carbon content from AERONET data. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2011, 11, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, K.; Trautmann, T.; Blaschke, T.; Majid, H. Aerosol optical and radiative properties during summer and winter seasons over Lahore and Karachi. Atmospheric Environment 2012, 50, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, A.J.; Ganderton, D. Pharmaceutical process engineering; CRC Press: 2016.

- Kabir, M.; Habiba, U.E.; Khan, W.; Shah, A.; Rahim, S.; Farooqi, Z.U.R.; Iqbal, M.Z.; Shafiq, M. Climate change due to increasing concentration of carbon dioxide and its impacts on environment in 21st century; A mini review. Journal of King Saud University-Science 2023, 2, 102693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalair, A.; Abas, N.; Saleem, M.S.; Kalair, A.R.; Khan, N. Role of energy storage systems in energy transition from fossil fuels to renewables. Energy Storage 2021, 3, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gilio, A.; Palmisani, J.; Pulimeno, M.; Cerino, F.; Cacace, M.; Miani, A.; de Gennaro, G. CO2 concentration monitoring inside educational buildings as a strategic tool to reduce the risk of Sars-CoV-2 airborne transmission. Environmental research 2021, 202, 111560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ju, P.; Zhu, Q.; Xu, X.; Wu, N.; Gao, Y.; Feng, X.; Tian, J.; Niu, S.; Zhang, Y. Carbon and nitrogen cycling on the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Nature Reviews Earth Environment 2022, 3, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, K.; Upadhyayula, S. Influence of reduction temperature on the formation of intermetallic Pd2Ga phase and its catalytic activity in CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. Greenhouse Gases: Science Technology 2019, 9, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liangruksa, M.; Sukpoonprom, P.; Junkaew, A.; Photaram, W.; Siriwong, C. Gas sensing properties of palladium-modified zinc oxide nanofilms: A DFT study. Applied Surface Science 2021, 544, 148868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.; Taha, K.; Modwi, A.; Khezami, L. ZnO nanoparticles: Surface and X-ray profile analysis. Ovonic Res 2018, 14, 381–393. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Sun, L.; Gao, Y.; Wang, T.; Huang, Y.; Lv, C.; Zhang, Y.-F.; Huang, Q.; Chen, X.; Wu, H. Synthesis of ZnO nanoparticle-anchored biochar composites for the selective removal of perrhenate, a surrogate for pertechnetate, from radioactive effluents. Journal of hazardous materials 2020, 387, 121670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, H.; Alam, K.; Bibi, S. In-depth discrimination of aerosol types using multiple clustering techniques over four locations in Indo-Gangetic plains. Atmospheric Research 2016, 181, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.R.; Yin, Y.; Sivakumar, V.; Kang, N.; Yu, X.; Diao, Y.; Adesina, A.J.; Reddy, R. Aerosol climatology and discrimination of aerosol types retrieved from MODIS, MISR and OMI over Durban (29.88 S, 31.02 E), South Africa. Atmospheric Environment 2015, 117, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, A.H.; Won, J.G.; Winker, D.M.; Yoon, S.C.; Dubovik, O.; McCormick, M.P. Development of global aerosol models using cluster analysis of Aerosol Robotic Network (AERONET) measurements. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2005, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, B.; Bhuyan, P.K.; Gogoi, M.; Bhuyan, K. Seasonal heterogeneity in aerosol types over Dibrugarh-North-Eastern India. Atmospheric environment 2012, 47, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedia, S.; Ramachandran, S.; Holben, B.N.; Tripathi, S. Quantification of aerosol type, and sources of aerosols over the Indo-Gangetic Plain. Atmospheric Environment 2014, 98, 607–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.-h.; Zhang, M.-y.; Zhao, Y.-y.; Chen, B.-g.; Zhang, J.; Sun, C.-C. Stability and property of planar (BN) x clusters. Chemical physics letters 2006, 423, 212–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcaro, G.; Monti, S.; Sementa, L.; Carravetta, V. Modeling nucleation and growth of ZnO nanoparticles in a low temperature plasma by reactive dynamics. Journal of Chemical Theory Computation 2019, 15, 2010–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Liu, Z.; Liu, T.; Duo, S.; Huang, L.; Yi, S.; Cai, L. Well-organized assembly of ZnO hollow cages and their derived Ag/ZnO composites with enhanced photocatalytic property. Materials Characterization 2020, 160, 110125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohidi, S.; Tohidi, T.; Mohammadabad, P.H. CuO-decorated ZnO nanotube–based sensor for detecting CO gas: a first-principles study. Journal of Molecular Modeling 2021, 27, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Cao, H.; Chen, H.; Yang, Y.; Sarkar, A. Sensing the cathinone drug concentration in the human body by using zinc oxide nanostructures: a DFT study. Structural Chemistry 2021, 32, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Hu, D.; Yao, A.; Gao, Y.; Asadi, H.; Nanostructures. A computational study on the Pd-decorated ZnO nanocluster for H2 gas sensing: A comparison with experimental results. Physica E: Low-dimensional Systems Nanostructures 2020, 124, 114237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalenko Mariya, B.O. , Dzikovskyi Viktor, Bovhyra Rostyslav. A DFT study for adsorption of CO and H2 on Pt-doped ZnO nanocluster. Applied Sciences 2020, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mian, S.A.; Hussain, A.; Basit, A.; Rahman, G.; Ahmed, E.; Jang, J. Molecular modeling and simulation of transition metal–doped molybdenum disulfide biomarkers in exhaled gases for early detection of lung cancer. Journal of Molecular Modeling 2023, 29, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, F.; Shohag, S.; Uddin, M.J.; Islam, M.R.; Nafady, M.H.; Akter, A.; Mitra, S.; Roy, A.; Emran, T.B.; Cavalu, S. Exploring the journey of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) toward biomedical applications. Materials 2022, 15, 2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.K.; Mohan, S.; Valdez, M.; Lozano, K.; Mao, Y. Enhanced sensitivity of caterpillar-like ZnO nanostructure towards amine vapor sensing. Materials Research Bulletin 2021, 142, 111419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, F.; Bakar, N.A.; Bakar, M.A. Current advancements on the fabrication, modification, and industrial application of zinc oxide as photocatalyst in the removal of organic and inorganic contaminants in aquatic systems. Journal of hazardous materials 2022, 424, 127416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mage, D.; Ozolins, G.; Peterson, P.; Webster, A.; Orthofer, R.; Vandeweerd, V.; Gwynne, M. Urban air pollution in megacities of the world. Atmospheric Environment 1996, 30, 681–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.; Dey, S.; Tare, V.; Satheesh, S. Aerosol black carbon radiative forcing at an industrial city in northern India. Geophysical Research Letters 2005, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.K.; Singh, S.; Tiwari, S.; Bisht, D. Contribution of anthropogenic aerosols in direct radiative forcing and atmospheric heating rate over Delhi in the Indo-Gangetic Basin. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2012, 19, 1144–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, R.B.; Murayama, Y. Urban growth modeling of Kathmandu metropolitan region, Nepal. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 2011, 35, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, B.A.; Kim, E.; Biswas, S.K.; Hopke, P.K. Investigation of sources of atmospheric aerosol at urban and semi-urban areas in Bangladesh. Atmospheric Environment 2004, 38, 3025–3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubovik, O.; Smirnov, A.; Holben, B.; King, M.; Kaufman, Y.; Eck, T.; Slutsker, I. Accuracy assessments of aerosol optical properties retrieved from Aerosol Robotic Network (AERONET) Sun and sky radiance measurements. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2000, 105, 9791–9806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, K.; Trautmann, T.; Blaschke, T. Aerosol optical properties and radiative forcing over mega-city Karachi. Atmospheric Research 2011, 101, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, A.; Holben, B.; Eck, T.; Dubovik, O.; Slutsker, I. Cloud-screening and quality control algorithms for the AERONET database. Remote sensing of environment 2000, 73, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, A.; Adil, M.; Mian, S.A.; Rahman, G.; Ahmed, E.; Mohy Ud Din, Z.; Qun, W. Tuning the optoelectronic properties of hematite with rhodium doping for photoelectrochemical water splitting using density functional theory approach. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, F.; Govender, K.K.; van Sittert, C.G.C.E.; Govender, P.P. Recent progress in the development of semiconductor-based photocatalyst materials for applications in photocatalytic water splitting and degradation of pollutants. Advanced Sustainable Systems 2017, 1, 1700006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, M.; Hussain, A.; Rauf, A.; Rahman, I.U.; Naveed, A.; Basit, M.A.; Rabbani, F.; Khan, S.U.; Ahmed, E.; Hussain, M. Tailoring the antifouling agent titanium dioxide in the visible range of solar spectrum for photoelectrochemical activity with hybrid DFT & DFT+ U approach. Materials Today Communications 2021, 27, 102366. [Google Scholar]

- Mamoun, S.; Merad, A.; Guilbert, L. Energy band gap and optical properties of lithium niobate from ab initio calculations. Computational Materials Science 2013, 79, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltsoyannis, N.; McGrady, J.; Harvey, J.; I, a.o.d.f.t.i.i.c. DFT computation of relative spin-state energetics of transition metal compounds. Principles 2004, 5, 151–184. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Luo, W.; Crespi, V.H.; Cohen, M.L.; Louie, S.G. Doping effects on the electronic and structural properties of CoO 2: An LSDA+ U study. Physical Review B 2004, 70, 085108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, C.; Barone, V. Physically motivated density functionals with improved performances: The modified Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof model. The Journal of chemical physics 2002, 116, 5933–5940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Prakash, D.; Ricaud, P.; Payra, S.; Attié, J.-L.; Soni, M. A new classification of aerosol sources and types as measured over Jaipur, India. Aerosol Air Quality Research 2015, 15, 985–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, P.; Ramaswamy, V.; Artaxo, P.; Berntsen, T.; Betts, R.; Fahey, D.W.; Haywood, J.; Lean, J.; Lowe, D.C.; Myhre, G. Changes in atmospheric constituents and in radiative forcing. Chapter 2. In Climate Change 2007. The Physical Science Basis, 2007.

- Wang, Z.; Liu, D.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Khatri, P.; Zhou, J.; Takamura, T.; Shi, G. Seasonal characteristics of aerosol optical properties at the SKYNET Hefei site (31.90 N, 117.17 E) from 2007 to 2013. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2014, 119, 6128–6139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Kumar, K.R.; Lü, R.; Ma, J. Changes in column aerosol optical properties during extreme haze-fog episodes in January 2013 over urban Beijing. Environmental Pollution 2016, 210, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. Global warming, climate change and greenhouse gas mitigation. In Biofuels: Greenhouse gas mitigation and global warming, Springer: 2018; Vol. 2, pp. 1–16.

- Tiwari, S.; Srivastava, A.; Singh, A.; Singh, S. Identification of aerosol types over Indo-Gangetic Basin: implications to optical properties and associated radiative forcing. Environmental Science Pollution Research 2015, 22, 12246–12260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yari, S.; Mahdavian, L.; Dehghanpour, N. Computational Investigation for the Removal of Hydrocarbon Sulfur Compounds by Zinc Oxide Nano-Cage (Zn12O12-NC). Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds 2023, 43, 370–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Hu, D.; Yao, A.; Gao, Y.; Asadi, H. A computational study on the Pd-decorated ZnO nanocluster for H2 gas sensing: A comparison with experimental results. Physica E: Low-dimensional Systems Nanostructures 2020, 124, 114237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonam; Garg, S. ; Goel, N. Density functional study on electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide to C1 products using zinc oxide catalyst. Theoretical Chemistry Accounts 2023, 142, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Li, L.; Wen, J.; Zeng, Y.-R. Structural stability and ionic transport property of NaMPO4 (M= V, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni) as cathode material for Na-ion batteries. Journal of Power Sources 2019, 438, 227016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, R.; Thamaraichelvan, A.; Viswanathan, B. Methanol formation by catalytic hydrogenation of CO 2 on a nitrogen doped zinc oxide surface: an evaluative study on the mechanistic pathway by density functional theory. RSC advances 2015, 5, 60524–60533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalenko, M.; Bovgyra, O.; Dzikovskyi, V.; Bovhyra, R. A DFT study for adsorption of CO and H2 on Pt-doped ZnO nanocluster. SN Applied Sciences 2020, 2, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cretu, V.; Postica, V.; Mishra, A.; Hoppe, M.; Tiginyanu, I.; Mishra, Y.; Chow, L.; De Leeuw, N.H.; Adelung, R.; Lupan, O. Synthesis, characterization and DFT studies of zinc-doped copper oxide nanocrystals for gas sensing applications. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2016, 4, 6527–6539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Fattah, T.M.; Mahmoud, M.E. Selective extraction of toxic heavy metal oxyanions and cations by a novel silica gel phase functionalized by vitamin B4. Chemical engineering journal 2011, 172, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politzer, P.; Wiener, J.; Seminario, J. Density Functional Calculations of Heats of Reaction in Recent Developments and Applications of Modern Density Functional Theory. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier: 1996; pp 139-277.

- Fukui, K. Role of frontier orbitals in chemical reactions. science 1982, 218, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadipour, N.L.; Ahmadi Peyghan, A.; Soleymanabadi, H. Theoretical study on the Al-doped ZnO nanoclusters for CO chemical sensors. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2015, 119, 6398–6404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Rauf, A.; Ahmed, E.; Khan, M.S.; Mian, S.A.; Jang, J. Modulating Optoelectronic and Elastic Properties of Anatase TiO2 for Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. Molecules 2023, 28, 3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baei, M.T.; Tabar, M.B.; Hashemian, S. Zn12O12 fullerene-like cage as a potential sensor for SO2 detection. Adsorption Science Technology 2013, 31, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslanzadeh, S. Transition metal doped ZnO nanoclusters for carbon monoxide detection: DFT studies. Journal of molecular modeling 2016, 22, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyghan, A.A.; Noei, M. The alkali and alkaline earth metal doped ZnO nanotubes: DFT studies. Physica B: Condensed Matter 2014, 432, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Hu, D.; Yao, A.; Gao, Y.; Asadi, H. A computational study on the Pd-decorated ZnO nanocluster for H2 gas sensing: A comparison with experimental results. Physica E: Low-dimensional Systems Nanostructures 2020, 124, 114237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Mantas, P.; Senos, A. Effect of Al and Mn doping on the electrical conductivity of ZnO. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 2001, 21, 1883–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Hussain, A.; Mian, S.A.; Rahman, G.; Ali, S.; Jang, J. Sensing and conversion of carbon dioxide to methanol using Ag-decorated zinc oxide nanocatalyst. Materials Advances 2024, 5, 1119–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Singh Bhati, V.; Ranwa, S.; Singh, J. Pd/ZnO nanorods based sensor for highly selective detection of extremely low concentration hydrogen. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.-H.; Huang, G.-F.; Huang, W.-Q. Visible-light absorption and photocatalytic activity of Cr-doped TiO2 nanocrystal films. Advanced Powder Technology 2012, 23, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.R.; Hawkins, E.; Jones, P.D. CO2, the greenhouse effect and global warming: from the pioneering work of Arrhenius and Callendar to today's Earth System Models. Endeavour 2016, 40, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Qiu, H. Catalytic hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol: A review. Catalysts 2022, 12, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.Y.; Na, C.W.; Kang, J.H.; Park, J. Comparative structure and optical properties of Ga-, In-, and Sn-doped ZnO nanowires synthesized via thermal evaporation. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2005, 109, 2526–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Wang, P.; Mickley, L.J.; Xia, X.; Liao, H.; Yue, X.; Sun, L.; Xia, J. Positive relationship between liquid cloud droplet effective radius and aerosol optical depth over Eastern China from satellite data. Atmospheric Environment 2014, 84, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, S.A.; Khan, S.U.; Hussain, A.; Rauf, A.; Ahmed, E.; Jang, J. Molecular Modelling of Optical Biosensor Phosphorene-Thioguanine for Optimal Drug Delivery in Leukemia Treatment. Cancers 2022, 14, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, E.; Tandon, P.; Maurya, R.; Kumar, P. A theoretical study on molecular structure, chemical reactivity and molecular docking studies on dalbergin and methyldalbergin. Journal of Molecular Structure 2019, 1183, 100–106. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, L.; Wu, X.; Hu, W. Experimental sensing and density functional theory study of H2S and SOF2 adsorption on Au-modified graphene. Advanced Science 2015, 2, 1500101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, H.-J.; Messmer, R. On the bonding and reactivity of CO2 on metal surfaces. Surface science 1986, 172, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| System | sensitivity (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO | - | 1.92 | -2.13 | 4.05 | - | - |

| ZnO/CO2 | - | 1.28 | -2.85 | 4.13 | - | - |

| ZnO-Zn | -0.85 | 0.89 | -1.29 | 2.18 | 46 | - |

| ZnO-Zn/CO2 | -0.14 | 1.01 | -1.04 | 2.05 | 50 | -49.38 |

| ZnO-Zn/CO2 + 3H2 | -0.081 | 0.77 | -1.10 | 1.87 | 55 | - |

| System | Temperature | Sensing Response | Recovery time |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO-Zn/CO2 | 300 | ||

| 320 | |||

| 340 | |||

| 360 | |||

| 380 | |||

| 400 |

| Chemical characteristics | ZnO | ZnO/CO2 | ZnO-Zn | ZnO-Zn/CO2 | ZnO-Zn/CO2+3H2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ionization Energy I (eV) | 2.13 | 2.85 | 1.30 | 1.0351 | 1.1053 |

| Electron affinity A | -1.92 | -1.28 | -0.90 | -1.0112 | -0.773 |

| Chemical hardness η | 2.03 | 2.07 | 1.095 | 1.0232 | 0.948 |

| Chemical softness s (eV)-1 | 0.25 | 0.242 | 0.50 | 0.489 | 0.5343 |

| Electronegativity χ (eV) | 0.105 | 0.785 | 0.198 | 0.01195 | 0.169 |

| Chemical-potential µ (eV) | -0.105 | -0.785 | -0.198 | -0.01195 | -0.169 |

| Electrophilic-index ԝ (eV) | 0.011 | 0.64 | 0.0214 | 7.3054 x 10-05 | 0.0134 |

| Charge transfer (ΔN) | - | - | - | -0.046 | 0.0296 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).