Submitted:

05 July 2024

Posted:

08 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

2.2. RNA Extraction

2.3. Extraction of Virion dsRNA

2.4. RT-qPCR

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

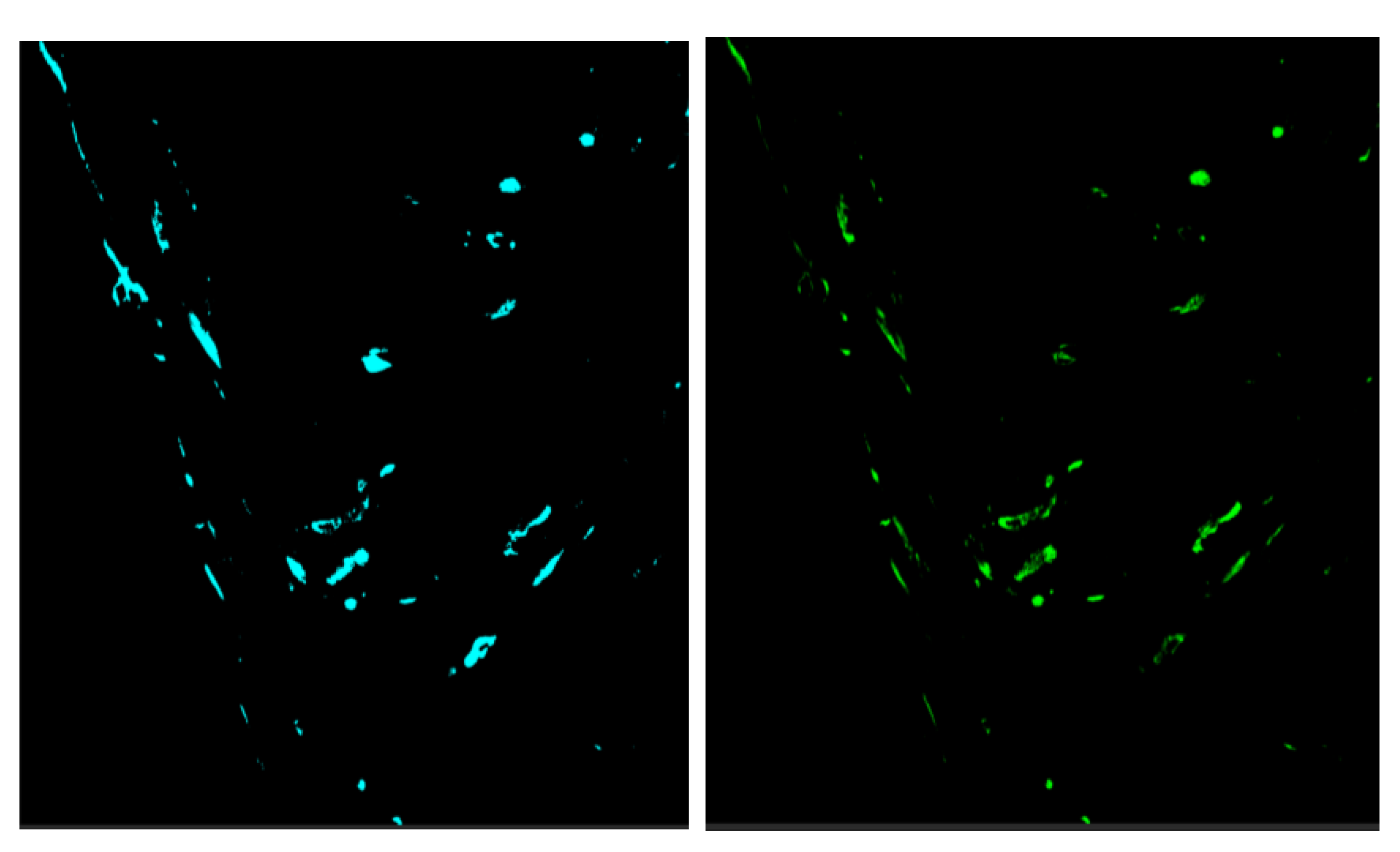

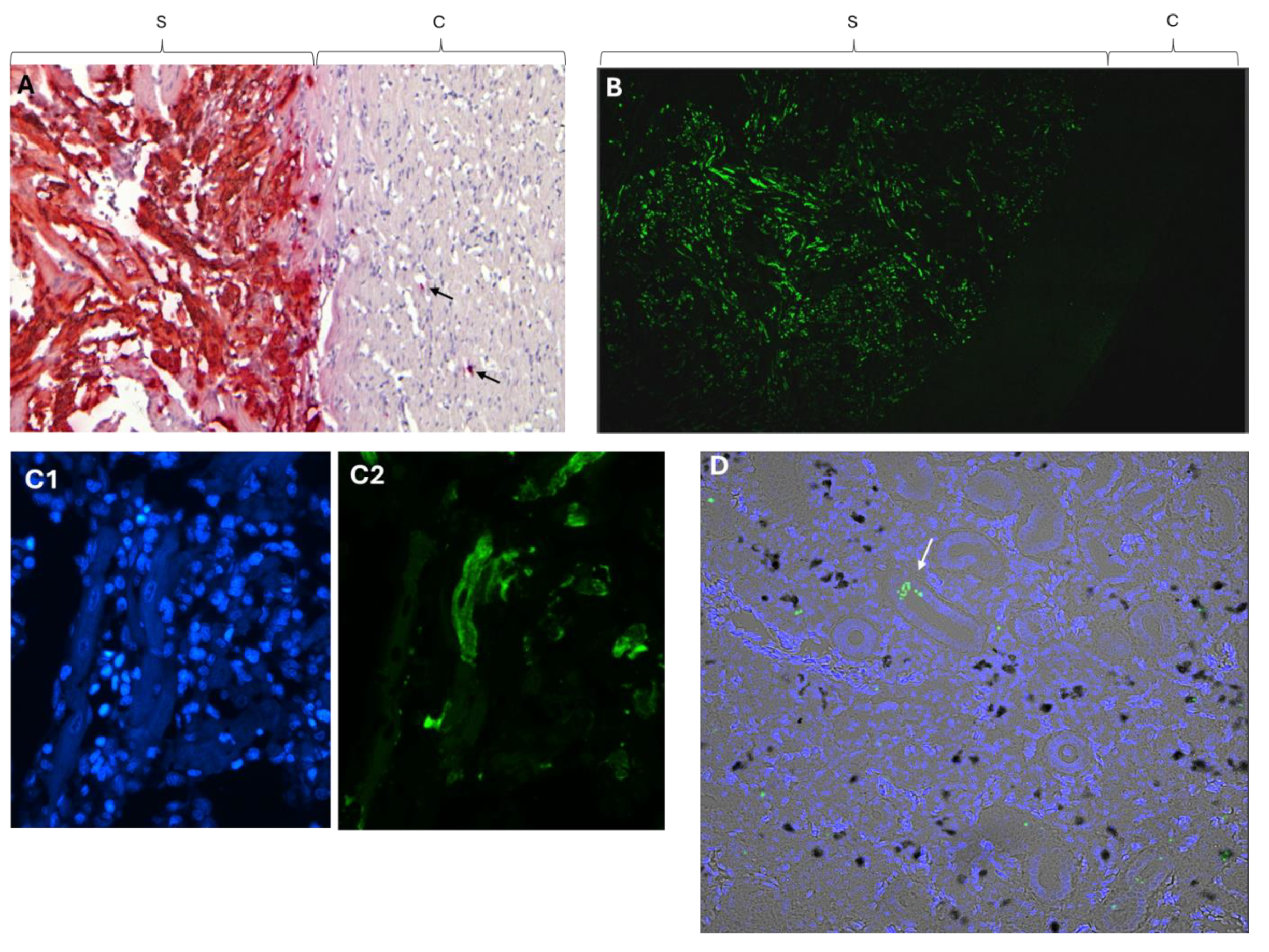

3.1. In Situ Localization of PMCV RNA In Heart Ventricle And Kidney

3.2. PMCV RNA Load in Different Organs

3.3. PMCV RNA form In Various Organs At Low And High Viral Load

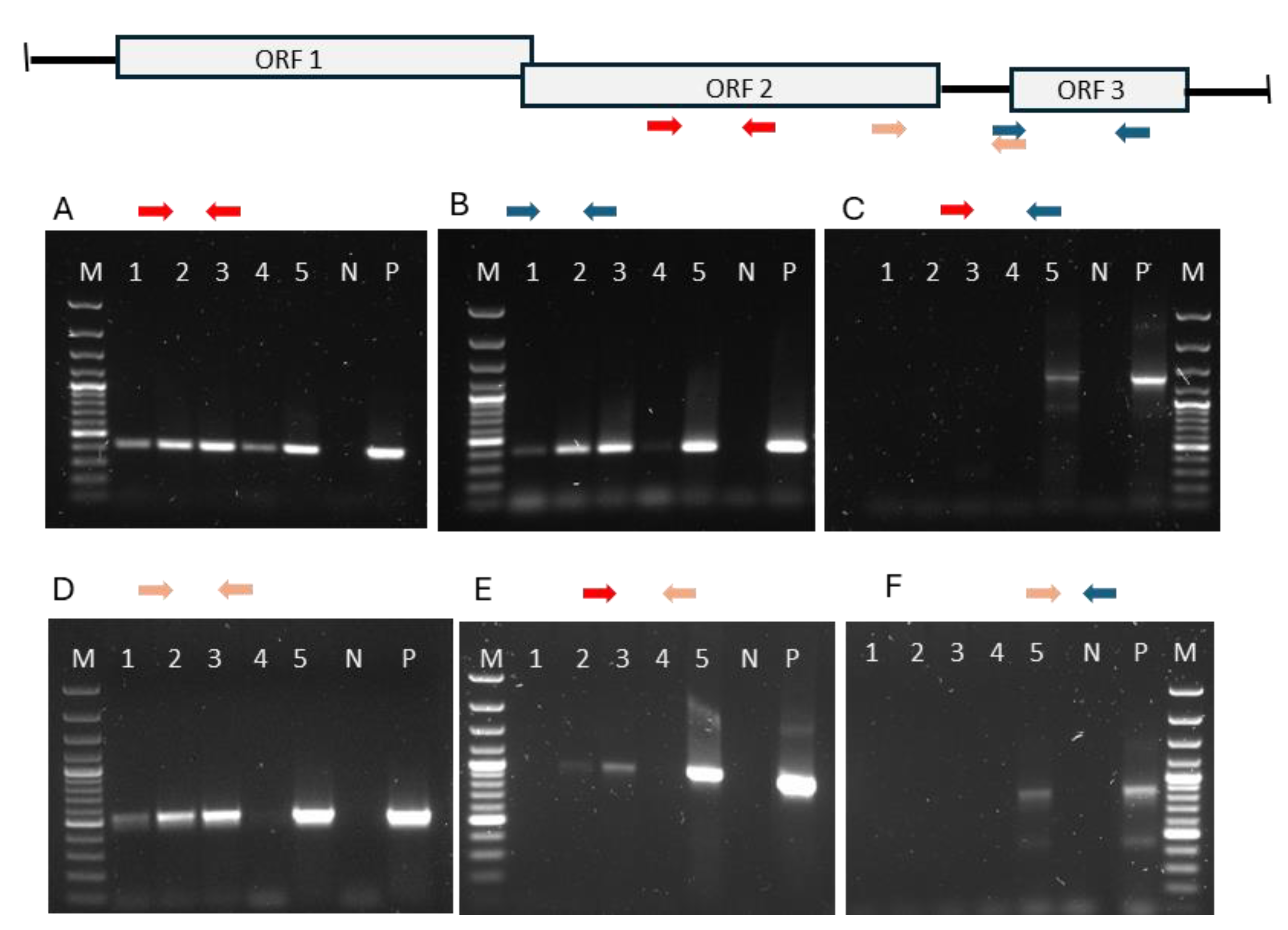

3.4. Genomic Organization of PMCV.

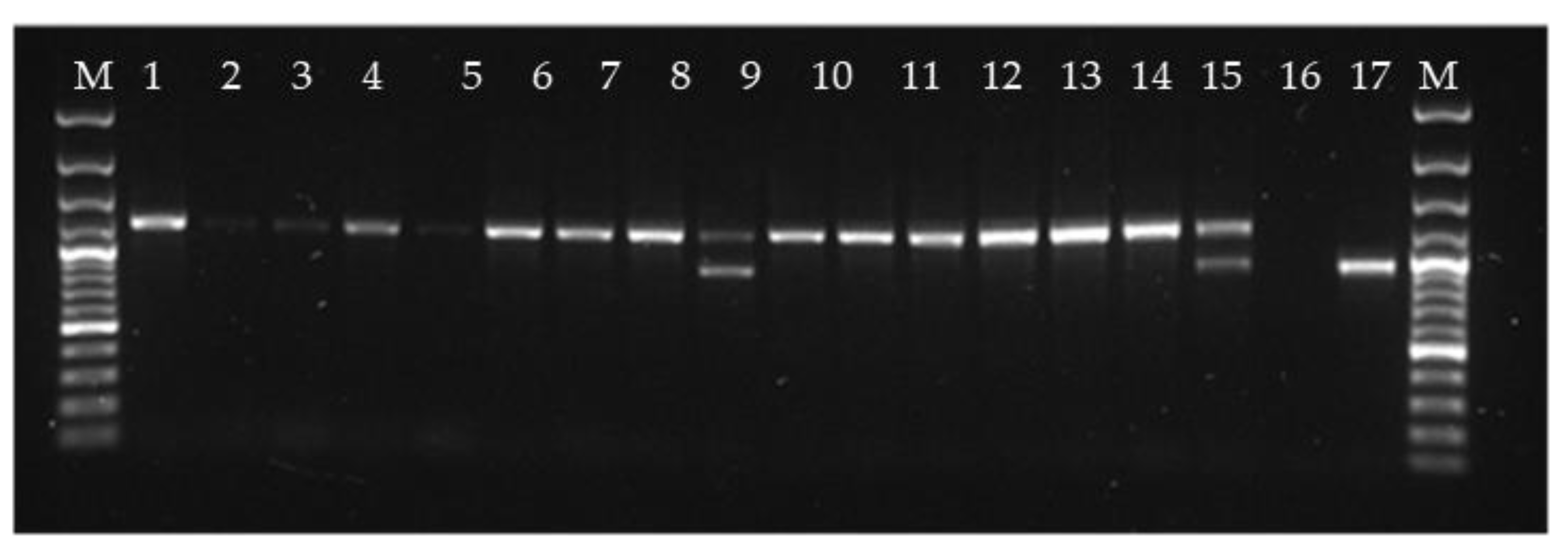

3.5. Are There Alternative Host Organisms for PMCV?

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Target | Primer name | Sequence 5’- 3’ | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fungi | ITS1ITS4 (ytre) | TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC |

[37] |

| Fungi | ITS2ITS3 | GCTGCGTTCTTCCATCGATGC GCATCGATGAAGAACGCAGC |

[37] |

| Fungi | NL-1NL-4 | GCATATCAATAAGCGGAGGAAAAG GGTCCGTGTTTCAAGACGG |

[37] |

| Fungi | EF1-1018F EF1-1620R | GAYTTCATCAAGAACATGAT GACGTTGAADCCRACRTTGTC |

[37] |

| Fungi | ITS5ITS4 | GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC |

[38] |

| Trypanozoma | Try-FwTry-Rw | CCAWACAACAAACATATGATGCTGC TCCHGATATGGTWTTKCCYCG |

[39] |

| Apicomplexa | Api-FwApi-Rw | GAAACTGCGAATGGCTCATT CTTGCGCCTACTAGGCATTC |

[40] |

| Mikrosporidia | CM-V5FCM-V5R | GATTAGANACCNNNGTAGTTC TAANCAGCACAMTCCACTC |

[41] |

| Mikrosporidia | bcdF01bcdR06 | CATTTTCHACTAAYCATAARGATATTGG GGDGGRTAHACAGTYCAHCCNGT |

[41] |

| Myxozoa | Myxo_617FMyxo_2313R_all | CGCGCAAATTACCCAMTCCA CGTTACCGGAATRRCCTGACAG |

[42] |

| Ichtyophonus | NS1-FNS8 deg-R | GTAGTCATATGCTTGTCTC TCCGCAGGTTCACCWACGGA |

[43] |

| Ichtyophonus | vc7Fvc5R | GTCTGTACTGGTACGGCAGTTTC TCCCGAACTCAGTAGACACTCAA |

[43] |

| Ichthyophonus | Out ITS1-FOut-ITS2-R | GCGGAAGGATCATTACCAAATAACG GCCTGAGTTGAGGTCAAATTT |

[43] |

| Ichthyophonus | Ich7fIch6r | GCTCTTAATTGAGTGTCTAC CATAAGGTGCTAATGGTGTC |

[43] |

| Malassezia | LRORLR5 | ACCCGCTGAACTTAAGC TCCTGAGGGAAACTTCG |

[44] |

| Malassezia | Mal63 Fw Mal487 Rw | TTGGCTACAGCGGCGACGACCTG CATCGCCTTGCCGACCGTCG |

[44] |

| Malassezia | LR5 - 2LROR-2 | ATCCTGAGGGAAACTTC GTACCCGCTGAACTTAAGC |

[44] |

| Malassezia | Mala_28S_F2 Mala_28S_R2 | CGCGTTGTAATCTCGAGACG CCACCCAAAAACTCGCACA |

[44] |

| Debaryomyces | Deb FwDeb Rw | TCACCATCTTTCGGGTCCCAACAGC CCCGTGCGATGAGATGCCCAATTC |

[45] |

| Oomycetea | Cox2-FCox2-R | GGCAAATGGGTTTTCAAGATCC CCATGATTAATACCACAAATTTCACTAC |

[46] |

| Crusteacea | LCO1490HCO2198 | GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG TAAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAAAATCA |

[47] |

References

- Brun, E.; Poppe, T.; Skrudland, A.; Jarp, J. Cardiomyopathy syndrome in farmed atlantic salmon salmo salar: Occurrence and direct financial losses for norwegian aquaculture. Dis Aquat Organ 2003, 56, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritsvold, C.; Mikalsen, A.B.; Poppe, T.T.; Taksdal, T.; Sindre, H. Characterization of an outbreak of cardiomyopathy syndrome (cms) in young atlantic salmon, salmo salar l. J Fish Dis 2021, 44, 2067–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.; Trasti, J. Endomyocarditis in atlantic salmon in norwegian seafarms. Bull Eur Assoc Fish Pathol 1988, 8, 70–71. [Google Scholar]

- Fritsvold, C.; Kongtorp, R.T.; Taksdal, T.; Orpetveit, I.; Heum, M.; Poppe, T.T. Experimental transmission of cardiomyopathy syndrome (cms) in atlantic salmon salmo salar. Dis Aquat Organ 2009, 87, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haugland, O.; Mikalsen, A.B.; Nilsen, P.; Lindmo, K.; Thu, B.J.; Eliassen, T.M.; Roos, N.; Rode, M.; Evensen, O. Cardiomyopathy syndrome of atlantic salmon (salmo salar l.) is caused by a double-stranded rna virus of the totiviridae family. Journal of Virology 2011, 85, 5275–5286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovoll, M.; Wiik-Nielsen, J.; Grove, S.; Wiik-Nielsen, C.R.; Kristoffersen, A.B.; Faller, R.; Poppe, T.; Jung, J.; Pedamallu, C.S.; Nederbragt, A.J. , et al. A novel totivirus and piscine reovirus (prv) in atlantic salmon (salmo salar) with cardiomyopathy syndrome (cms). Virol J 2010, 7, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, H.; van Eerde, A.; Steen, H.S.; Heldal, I.; Haugslien, S.; Ørpetveit, I.; Wüstner, S.C.; Inami, M.; Løvoll, M.; Rimstad, E. Establishment of a piscine myocarditis virus (pmcv) challenge model and testing of a plant-produced subunit vaccine candidate against cardiomyopathy syndrome (cms) in atlantic salmon salmo salar. Aquaculture 2021, 541, 736806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinman, J.D.; Icho, T.; Wickner, R.B. A -1 ribosomal frameshift in a double-stranded rna virus of yeast forms a gag-pol fusion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1991, 88, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Cousiño, N.; Esteban, R. Relationships and evolution of double-stranded rna totiviruses of yeasts inferred from analysis of la-2 and l-bc variants in wine yeast strain populations. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2017, 83, e02991–02916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermin, G.; Mazumdar-Leighton, S.; Tennant, P. Viruses of prokaryotes, protozoa, fungi, and chromista. Viruses, Academic Press, London 2018, 217-244.

- Wickner, R.B.; Ribas, J.C. Totivirus. In The springer index of viruses, 2011.

- Tang, J.; Ochoa, W.F.; Sinkovits, R.S.; Poulos, B.T.; Ghabrial, S.A.; Lightner, D.V.; Baker, T.S.; Nibert, M.L. Infectious myonecrosis virus has a totivirus-like, 120-subunit capsid, but with fiber complexes at the fivefold axes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008, 105, 17526–17531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Q.; Jia, X.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Tan, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, H.; Li, Y.; Wu, D. Cryo-em reveals a previously unrecognized structural protein of a dsrna virus implicated in its extracellular transmission. PLoS pathogens 2021, 17, e1009396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lima, J.G.; Lanza, D.C. 2a and 2a-like sequences: Distribution in different virus species and applications in biotechnology. Viruses 2021, 13, 2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantas, M.D.A.; Cavalcante, G.H.O.; Oliveira, R.A.; Lanza, D.C. New insights about orf1 coding regions support the proposition of a new genus comprising arthropod viruses in the family totiviridae. Virus research 2016, 211, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulos, B.T.; Tang, K.F.; Pantoja, C.R.; Bonami, J.R.; Lightner, D.V. Purification and characterization of infectious myonecrosis virus of penaeid shrimp. Journal of General Virology 2006, 87, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Marucci, G.; Munke, A.; Hassan, M.M.; Lalle, M.; Okamoto, K. High-resolution comparative atomic structures of two giardiavirus prototypes infecting g. Duodenalis parasite. PLoS Pathog 2024, 20, e1012140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessel, O.; Olsen, C.M.; Rimstad, E.; Dahle, M.K. Piscine orthoreovirus (prv) replicates in atlantic salmon (salmo salar l.) erythrocytes ex vivo. Vet Res 2015, 46, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodneland, K.; Endresen, C. Sensitive and specific detection of salmonid alphavirus using real-time pcr (taqman). J Virol Methods 2006, 131, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Raines, R.T. Origin of the 'inactivation' of ribonuclease a at low salt concentration. FEBS Lett 2000, 468, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinski, M.P.; Marty, G.D.; Snyman, H.N.; Garver, K.A. Piscine orthoreovirus demonstrates high infectivity but low virulence in atlantic salmon of pacific canada. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, H.; Poppe, T.; Speare, D.J. Cardiomyopathy in farmed norwegian salmon. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 1990, 8, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti, E.; Ferrary-Américo, M.; Barardi, C.R.M. Detection of potential infectious enteric viruses in fresh produce by (rt)-qpcr preceded by nuclease treatment. Food Environ Virol 2017, 9, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickner, R.B. Double-stranded rna viruses of saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiological reviews 1996, 60, 250–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Applen Clancey, S.; Ruchti, F.; LeibundGut-Landmann, S.; Heitman, J.; Ianiri, G. A novel mycovirus evokes transcriptional rewiring in the fungus malassezia and stimulates beta interferon production in macrophages. mBio 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickner, R.B.; Tang, J.; Gardner, N.A.; Johnson, J.E.; Patton, J. The yeast dsrna virus la resembles mammalian dsrna virus cores. Caister Academic Press: 2008.

- Timmerhaus, G.; Krasnov, A.; Nilsen, P.; Alarcon, M.; Afanasyev, S.; Rode, M.; Takle, H.; Jørgensen, S.M. Transcriptome profiling of immune responses to cardiomyopathy syndrome (cms) in atlantic salmon. BMC Genomics 2011, 12, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiik-Nielsen, J.; Løvoll, M.; Fritsvold, C.; Kristoffersen, A.B.; Haugland, Ø.; Hordvik, I.; Aamelfot, M.; Jirillo, E.; Koppang, E.O.; Grove, S. Characterization of myocardial lesions associated with cardiomyopathy syndrome in a tlantic salmon, s almo salar l., using laser capture microdissection. Journal of Fish Diseases 2012, 35, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenorio, R.; Fernández de Castro, I.; Knowlton, J.J.; Zamora, P.F.; Sutherland, D.M.; Risco, C.; Dermody, T.S. Function, architecture, and biogenesis of reovirus replication neoorganelles. Viruses 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieperhoff, S.; Bennett, W.; Farrell, A.P. The intercellular organization of the two muscular systems in the adult salmonid heart, the compact and the spongy myocardium. J Anat 2009, 215, 536–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garseth, A.H.; Fritsvold, C.; Svendsen, J.C.; Jensen, B.B.; Mikalsen, A.B. Cardiomyopathy syndrome in atlantic salmon salmo salar l.: A review of the current state of knowledge. Journal of Fish Diseases 2018, 41, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevan, E.; Herring, A.; Mitchell, D.J. Preliminary characterization of two species of dsrna in yeast and their relationship to the “killer” character. Nature 1973, 245, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandlund, L.; Mor, S.K.; Singh, V.K.; Padhi, S.K.; Phelps, N.B.D.; Nylund, S.; Mikalsen, A.B. Comparative molecular characterization of novel and known piscine toti-like viruses. Viruses 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tighe, A.J.; Ruane, N.M.; Carlsson, J. Potential origins of fish toti-like viruses in invertebrates. Journal of General Virology 2022, 103, 001775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinbach, R.M.; El Baidouri, F.; Mitchison-Field, L.M.; Lim, F.Y.; Ekena, J.; Vogt, E.J.; Gladfelter, A.; Theberge, A.B.; Amend, A.S. Malassezia is widespread and has undescribed diversity in the marine environment. Fungal Ecology 2023, 65, 101273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengs, T.; Rimstad, E. Emerging pathogens in the fish farming industry and sequencing-based pathogen discovery. Dev Comp Immunol 2017, 75, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uyaguari-Diaz, M.I.; Chan, M.; Chaban, B.L.; Croxen, M.A.; Finke, J.F.; Hill, J.E.; Peabody, M.A.; Van Rossum, T.; Suttle, C.A.; Brinkman, F.S. A comprehensive method for amplicon-based and metagenomic characterization of viruses, bacteria, and eukaryotes in freshwater samples. Microbiome 2016, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bal, J.; Yun, S.-H.; Yeo, S.-H.; Kim, J.-M.; Kim, D.-H. Metagenomic analysis of fungal diversity in korean traditional wheat-based fermentation starter nuruk. Food Microbiology 2016, 60, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, M.S.; Morelli, K.A.; Jansen, A.M. Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 gene as a DNA barcode for discriminating trypanosoma cruzi dtus and closely related species. Parasites & vectors 2017, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Renoux, L.P.; Dolan, M.C.; Cook, C.A.; Smit, N.J.; Sikkel, P.C. Developing an apicomplexan DNA barcoding system to detect blood parasites of small coral reef fishes. Journal of Parasitology 2017, 103, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzebny, A.; Slodkowicz-Kowalska, A.; Becnel, J.J.; Sanscrainte, N.; Dabert, M. A new method of metabarcoding microsporidia and their hosts reveals high levels of microsporidian infections in mosquitoes (culicidae). Molecular Ecology Resources 2020, 20, 1486–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartikainen, H.; Bass, D.; Briscoe, A.G.; Knipe, H.; Green, A.J.; Okamura, B. Assessing myxozoan presence and diversity using environmental DNA. International Journal for Parasitology 2016, 46, 781–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaDouceur, E.E.; Leger, J.S.; Mena, A.; Mackenzie, A.; Gregg, J.; Purcell, M.; Batts, W.; Hershberger, P. Ichthyophonus sp. Infection in opaleye (girella nigricans). Veterinary pathology 2020, 57, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancey, S.A.; Ruchti, F.; LeibundGut-Landmann, S.; Heitman, J.; Ianiri, G. A novel mycovirus evokes transcriptional rewiring in malassezia and provokes host inflammation and an immunological response. bioRxiv [Preprint].

- Vu, D.; Groenewald, M.; Szöke, S.; Cardinali, G.; Eberhardt, U.; Stielow, B.; De Vries, M.; Verkleij, G.; Crous, P.; Boekhout, T. DNA barcoding analysis of more than 9 000 yeast isolates contributes to quantitative thresholds for yeast species and genera delimitation. Studies in mycology 2016, 85, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robideau, G.P.; De Cock, A.W.; Coffey, M.D.; Voglmayr, H.; Brouwer, H.; Bala, K.; Chitty, D.W.; Desaulniers, N.; Eggertson, Q.A.; Gachon, C.M. DNA barcoding of oomycetes with cytochrome c oxidase subunit i and internal transcribed spacer. Molecular ecology resources 2011, 11, 1002–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raupach, M.J.; Barco, A.; Steinke, D.; Beermann, J.; Laakmann, S.; Mohrbeck, I.; Neumann, H.; Kihara, T.C.; Pointner, K.; Radulovici, A. The application of DNA barcodes for the identification of marine crustaceans from the north sea and adjacent regions. PloS one 2015, 10, e0139421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Virus | Primer/Probe | Sequence (5’ → 3’) | Amplicon (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMCV | ||||

| ORF2 | PMCV-F | TTCCAAACAATTCGAGAAGCG | 140 | [6] |

| PMCV-R | ACCTGCCATTTTCCCCTCTT | |||

| PMCV probe | FAM-CCGGGTAAAGTATTTGCGTC- MGBNFQ | |||

| ORF3 | Orf3-3’Fw | TTACAGAGGGCGGGAACCTGTGTGG | ||

| Orf3-3’Rw | TGGCTTCTTGTGAATTGTCAACAC | 114 | ||

| Orf3 probe | FAM -TCTTCGATAATACGCAGTGTA- MGBNFQ | |||

| SYBR primers | SP3-orf2Fw | CTAAGGCCAGTGGCGGAATC | 264 | |

| Orf2 Rw | TGGTGGCATACTTACCCATG | |||

| Orf3 Fw | GGCGAGAATGGTGTTTGTGCACTGC | 266 | ||

| SP3-orf3Rw | GAATGAAGCAAGATGGAACC | |||

| Orf2-3’Fw | TTGGGTTCAAGAGGATAGAG | 122 | ||

| Orf2-3’Rw | GAATTTTGGTACCTGTGATG | |||

| PRV 1 | Sigma3 659 Fw | TGCGTCCTGCGTATGGCACC | [18] | |

| Sigma3 801Rw | GGCTGGCATGCCCGAATAGCA | |||

| Sigma3_693 probe | FAM-ATCACAACGCCTACCT–MGBNFQ | |||

| SAV | QnsP1 17F | CCGGCCCTGAACCAGTT | [19] | |

| QnsP1 122R | GTAGCCAAGTGGGAGAAAGCT | |||

| QnsP1_53probe | FAM-CTGGCCACCACTTCGA-MGBNFQ |

| Probe | Accession no. | Target region (bp) | Catalogue no. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V-Piscine-myocarditis-ORF1-C2) | JQ728724.1 | 1050-1757 | 812021-C2 | |

| V-PMCV-ORF2 | HQ339954.1 | 3441 - 4500 | 555231 | |

| V-PMCV-ORF2-sense-C3 | HQ339954.1 | 3441 - 4500 | 1219761-C3 | |

| DapB (negative control) | EF191515 | 414 - 862 | 310043 | |

| PPIB (positive control) | NM_001140870 | 20 - 934 | 494421 |

| Fish no. | Heart | Gills | Kidney | Spleen | Liver | Muscle | Skin scrape | Pyloric ceca | Mid-gut | Hind-gut |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 35.9 | - | - | - |

| 2 | 24.5 | 26.0 | 22.9 | 21.9 | 29.9 | 27.4 | 26.4 | 27.5 | 25.7 | 27.5 |

| 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 4 | 16.4 | 28.6 | 22.5 | 22.7 | 26.7 | 26.8 | 28.4 | 26.3 | 25.3 | 26.3 |

| 5 | 36.9 | - | 35.0 | - | - | - | 37.4 | - | - | - |

| 6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 7 | 24.4 | 26.4 | 22.9 | 22.9 | 29.5 | 28.1 | 29.9 | 27.4 | 22.2 | 27.1 |

| 8 | 22.9 | 28.8 | 21.9 | 21.8 | 27.1 | 27.8 | 29.6 | 29.6 | 29.1 | 30.5 |

| 9 | 16.9 | 28.0 | 24.5 | 24.9 | 30.5 | 28.4 | 28.7 | 28.9 | 28.3 | 27.7 |

| 10 | 26.2 | 26.3 | 23.9 | 25.1 | 30.8 | 28.0 | 27.3 | 29.5 | 26.5 | 27.6 |

| Ave | 21.9 | 27.3 | 23.1 | 23.2 | 29.1 | 27.8 | 28.4 | 28.2 | 26.2 | 27.8 |

| Heat treated (ssRNA + dsRNA) |

Not heat treated (ssRNA) |

ΔCq for PMCV ssRNA versus total PMCV RNA |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fish# | Heart | Kidney | Heart | Kidney | Heart | Kidney |

| 1 | 17.05 | 21.66 | 17.23 | 25.47 | 0.18 | 3.81 |

| 2 | 13.36 | 20.20 | 13.32 | 23.06 | -0.04 | 2.86 |

| 3 | 14.19 | 20.26 | 14.49 | 24.24 | 0.3 | 3.94 |

| 4 | 12.79 | 21.74 | 12.78 | 25.27 | -0.01 | 3.53 |

| 5 | 17.70 | 19.00 | 18.65 | 23.21 | 0.95 | 4.21 |

| 6 | 21.8 | 23.5 | 21.6 | 24.5 | -0.2 | 1 |

| 7 | 17.7 | 20.6 | 17.6 | 24.2 | -0.1 | 3.6 |

| 8 | 13.6 | 19.3 | 13.7 | 22.9 | 0.1 | 3.6 |

| 9 | 17.4 | 22.7 | 17.3 | 25.9 | -0.1 | 3.2 |

| 10 | 17.5 | 20.4 | 17.6 | 24.5 | 0.1 | 4.1 |

| ORF 2 | ORF 3 | ΔCt | Relative amount of ORF3 ssRNA versus ORF2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart 2 | 12.08 | 15.36 | -3.28 | 10% |

| Heart 3 | 12.97 | 17.94 | -4.97 | 3% |

| Heart 4 | 11.34 | 16.60 | -5.26 | 3% |

| Heart 5 | 18.31 | 21.72 | -3.41 | 9% |

| Average | 13.675 | 17.90 | 6.25% | |

| Kidney 2 | 22.91 | 24.23 | -1.32 | 40% |

| Kidney 3 | 23.84 | 25.43 | -1.59 | 33% |

| Kidney 4 | 24.68 | 27.10 | -2.42 | 19% |

| Kidney 5 | 23.13 | 24.71 | -1.58 | 33% |

| Average | 23.64 | 25.37 | 31.25% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).