Submitted:

04 July 2024

Posted:

08 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods and experiments

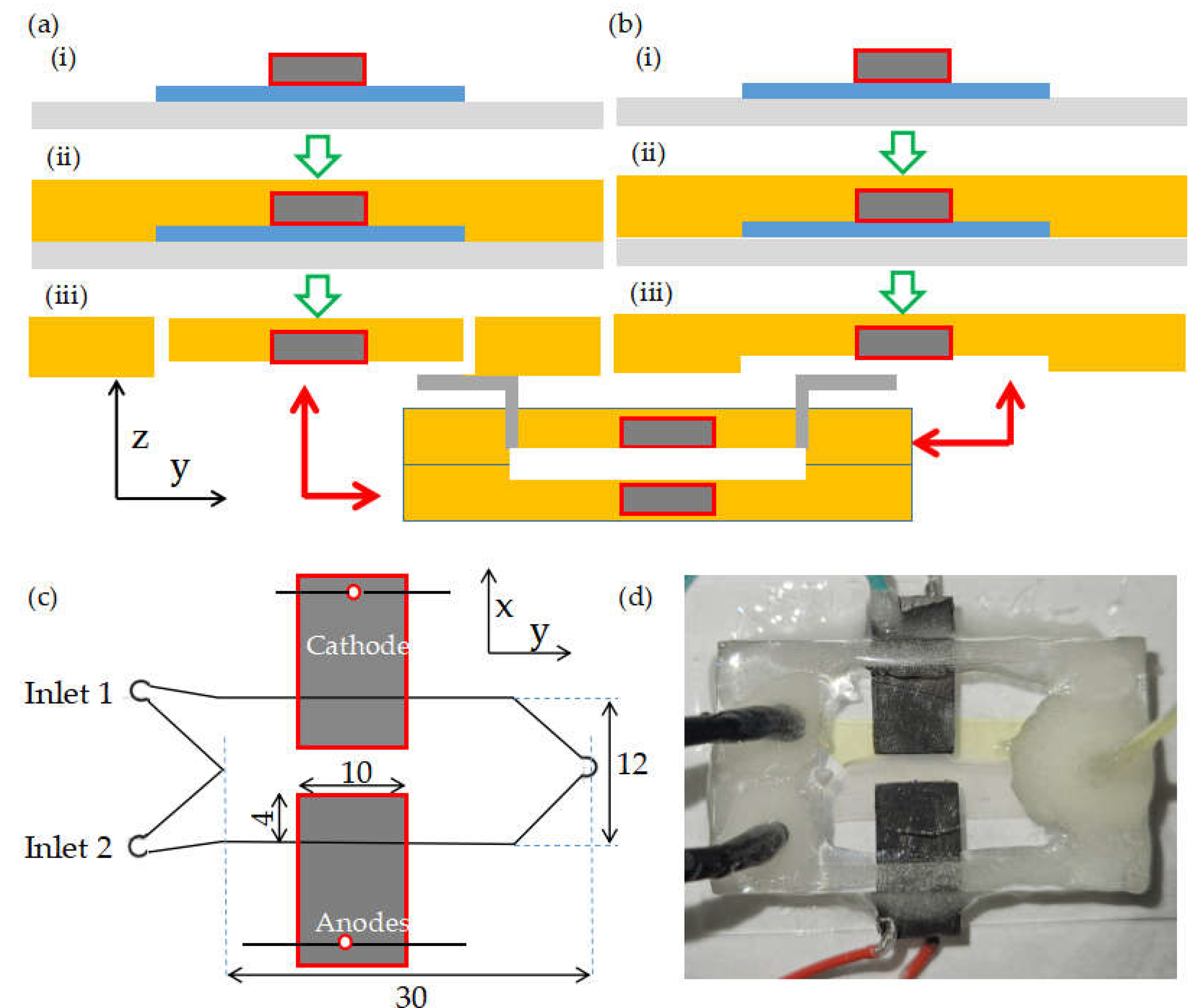

2.1. Fabrication of 4-electrode microfluidic MFC

2.2. Preparation of G. sulfurreducens electrogenic bacteria and medium solution

2.3. Calculations

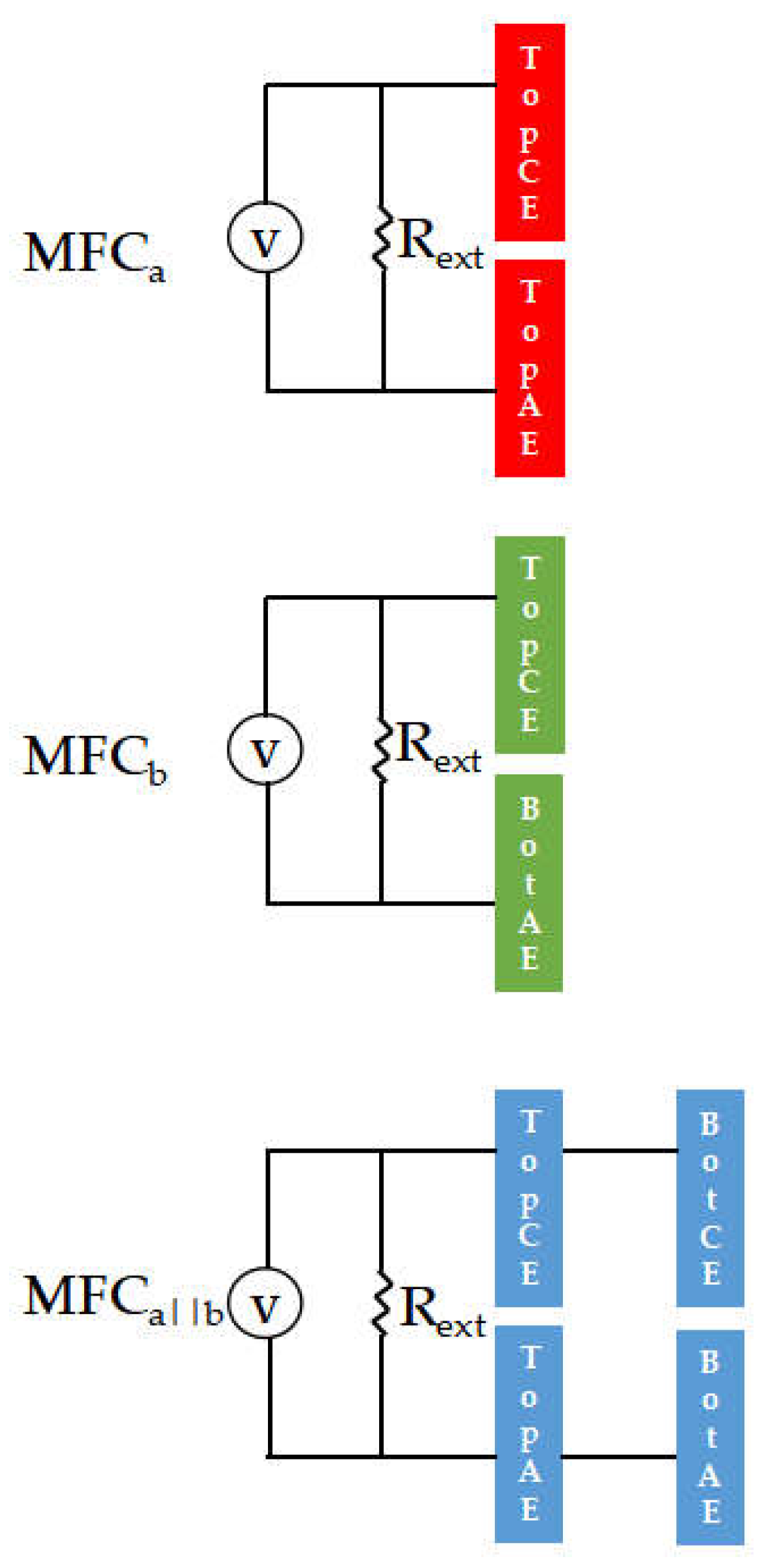

2.4. MFC configurations

2.5. SEM Imaging and image analysis

2.6. Computational fluid dynamics simulations

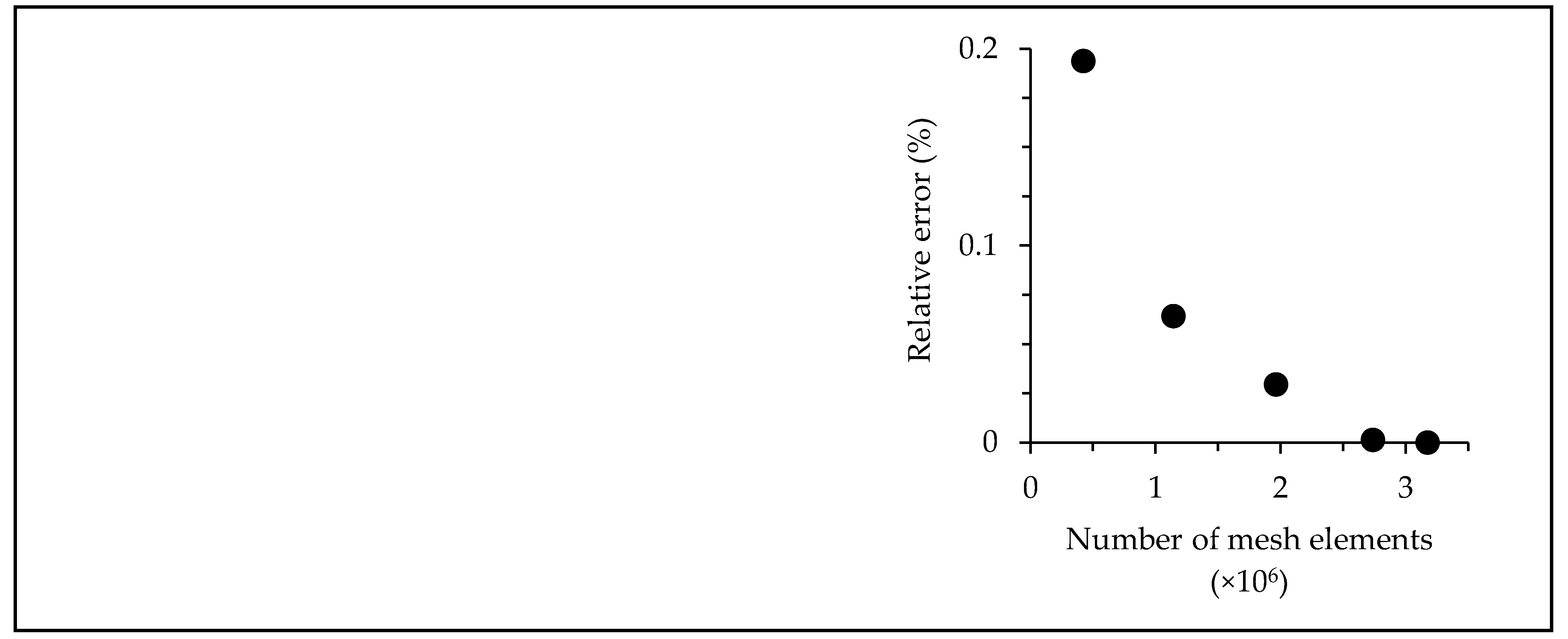

| Pre-set mesh density | Number of mesh elements | Relative error (%) |

| Coarse | 421,983 | 0.19379 |

| Normal | 1,142,143 | 0.06420 |

| Fine | 1,964,457 | 0.02939 |

| Finer | 2,738,854 | 0.00130 |

| >Extra fine | 3,173,758 | 0 |

3. Results and Discussion

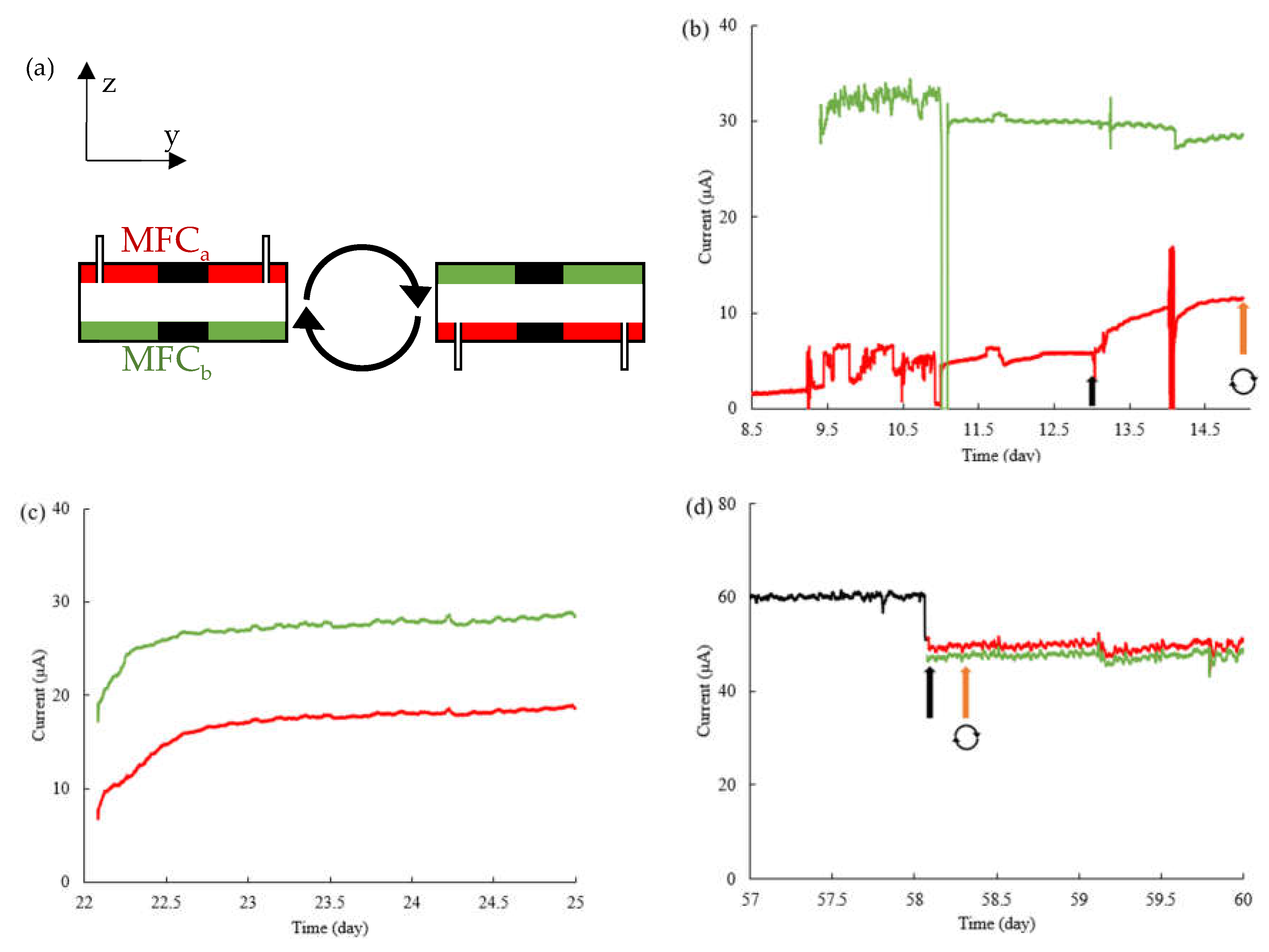

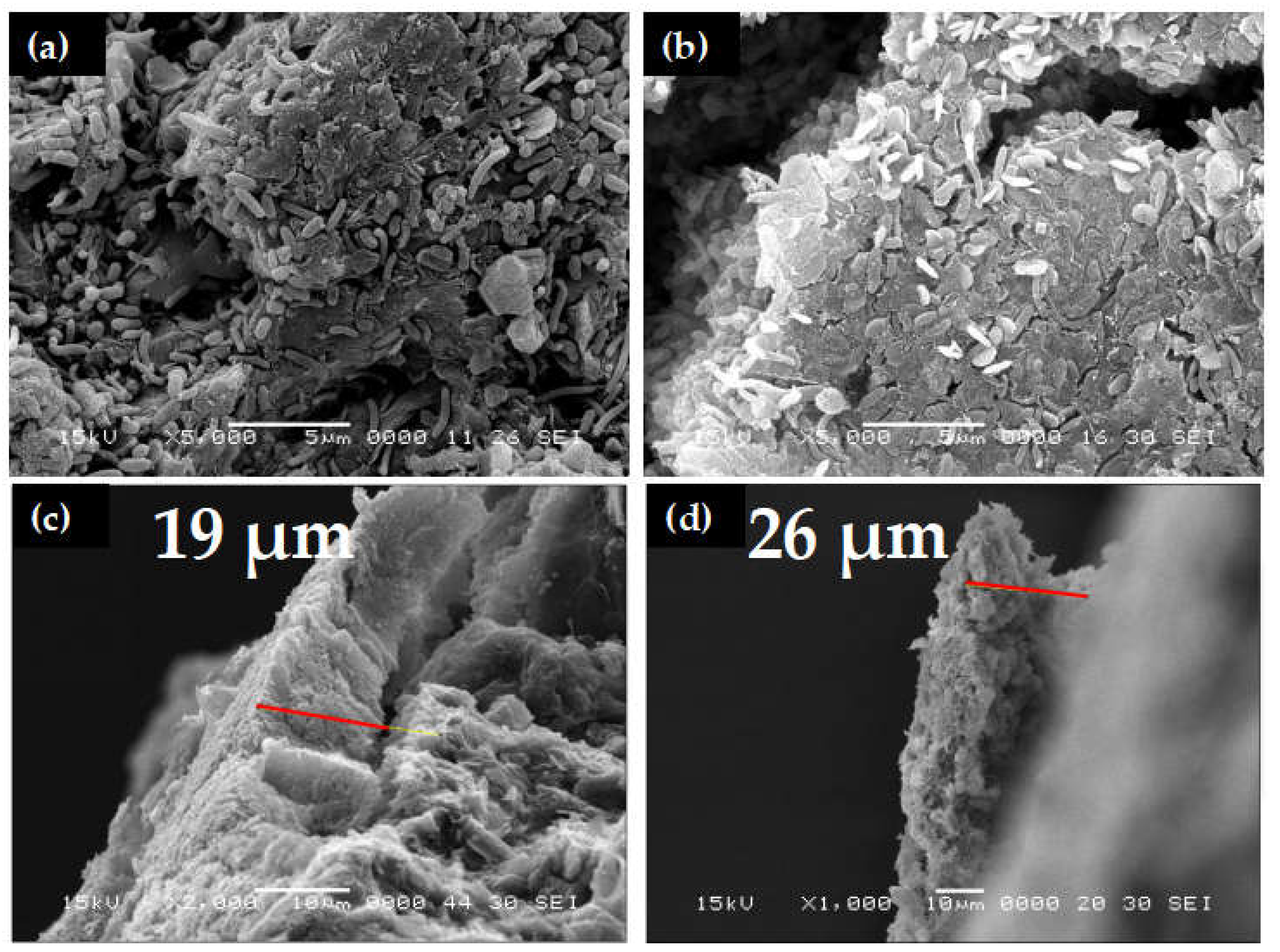

3.1. Growth of G. sulfurreducens in 4-electrode MFC

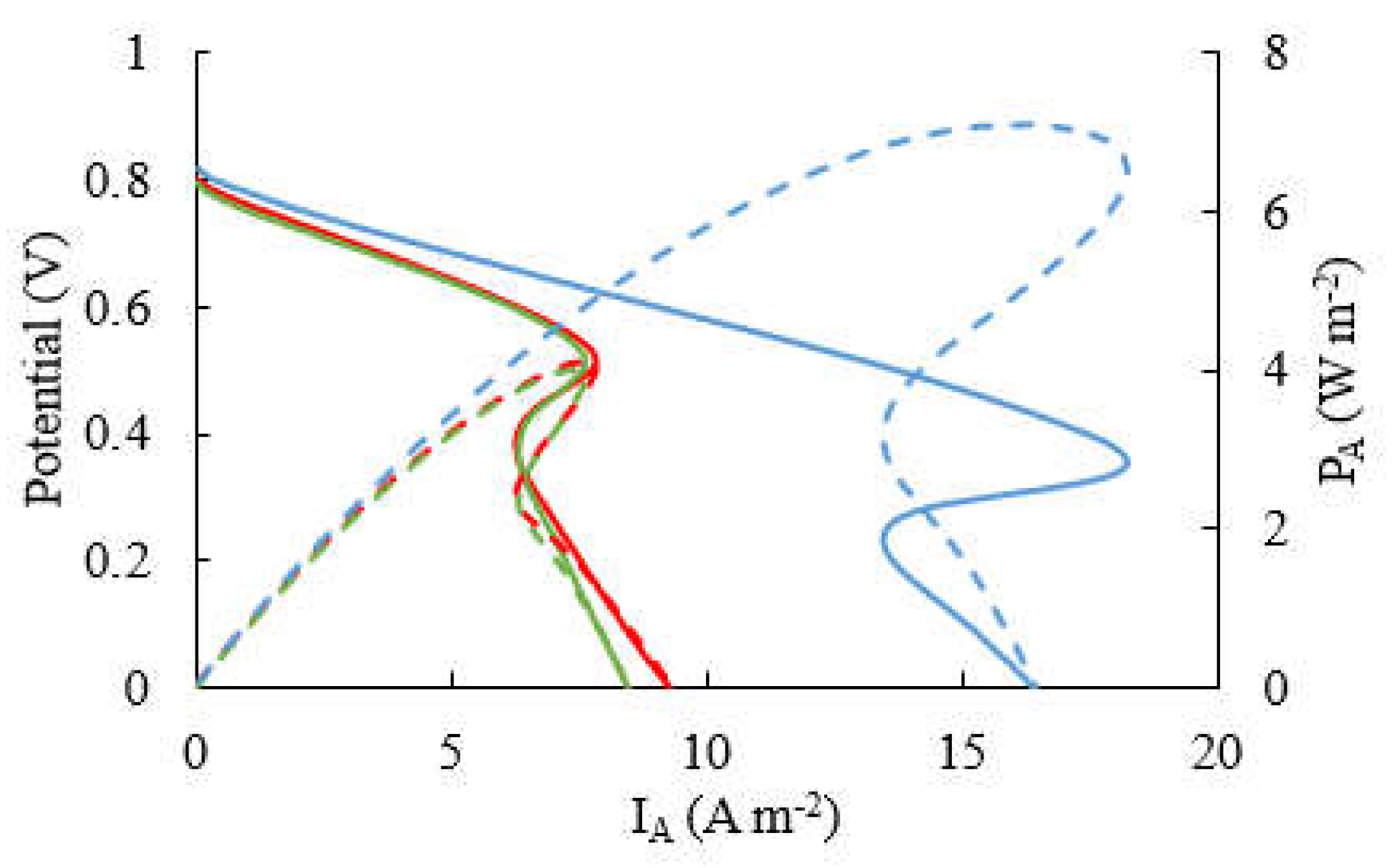

3.2. Power and current outputs at different ages

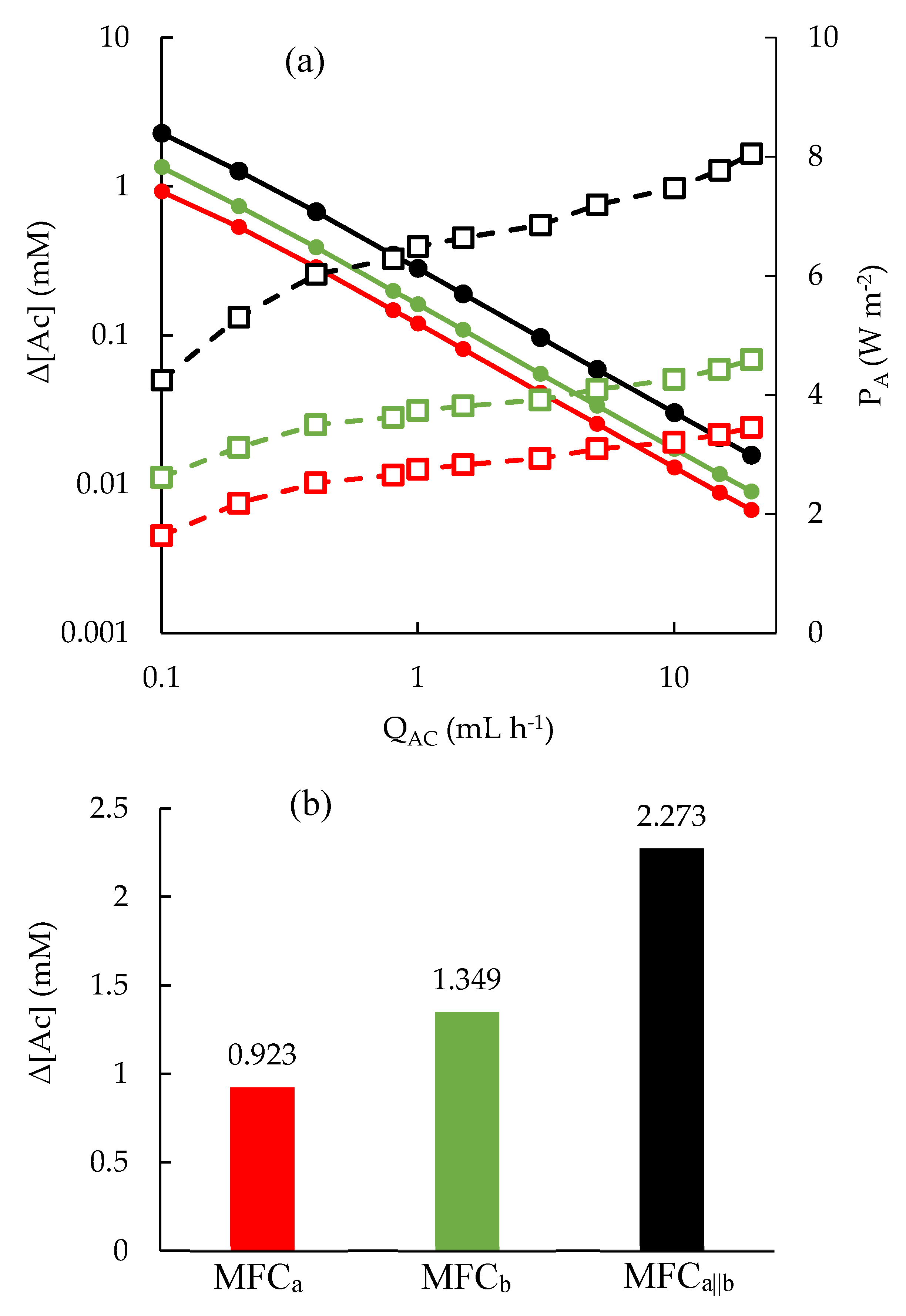

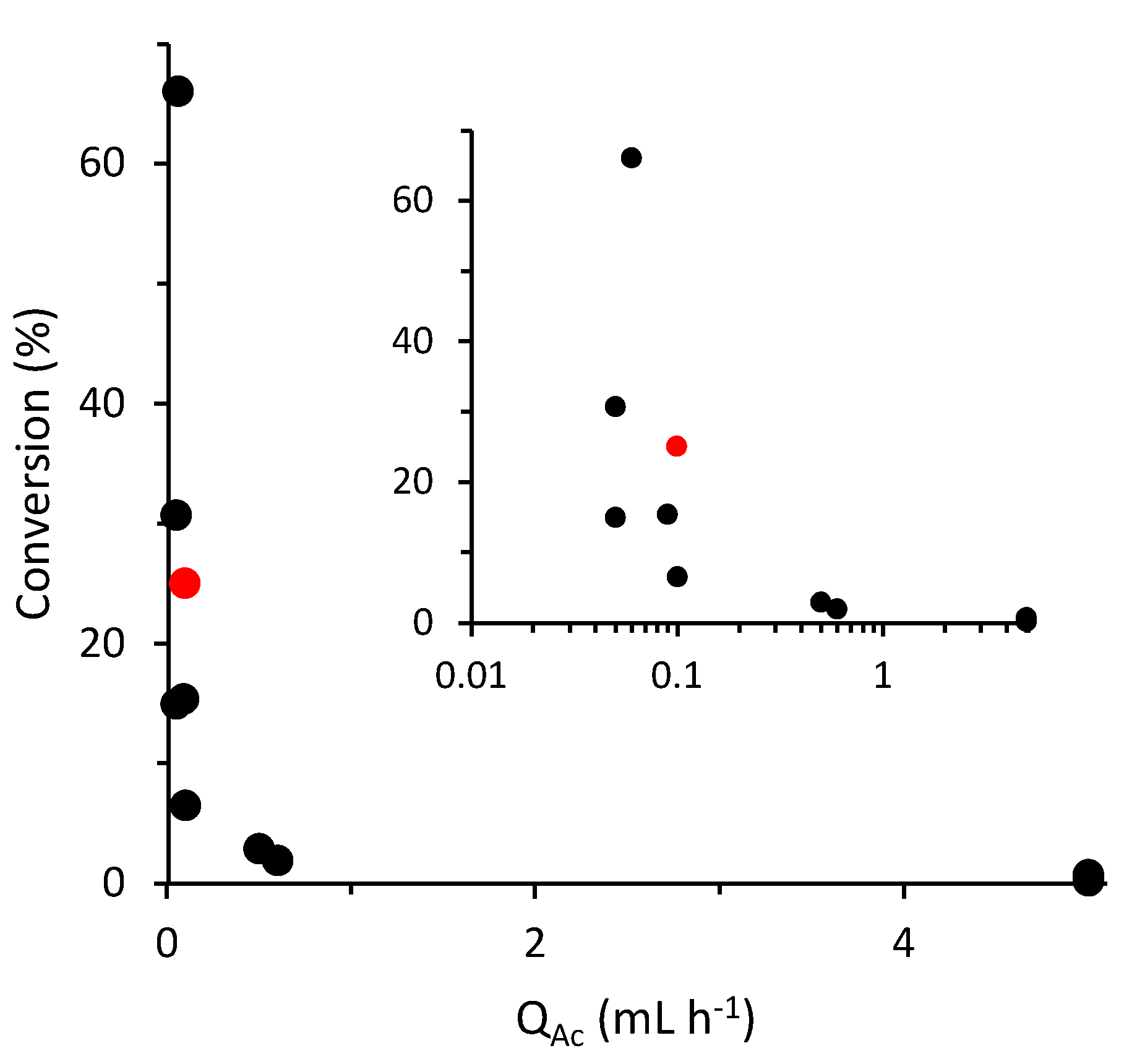

3.3. Flow effect on MFC performance

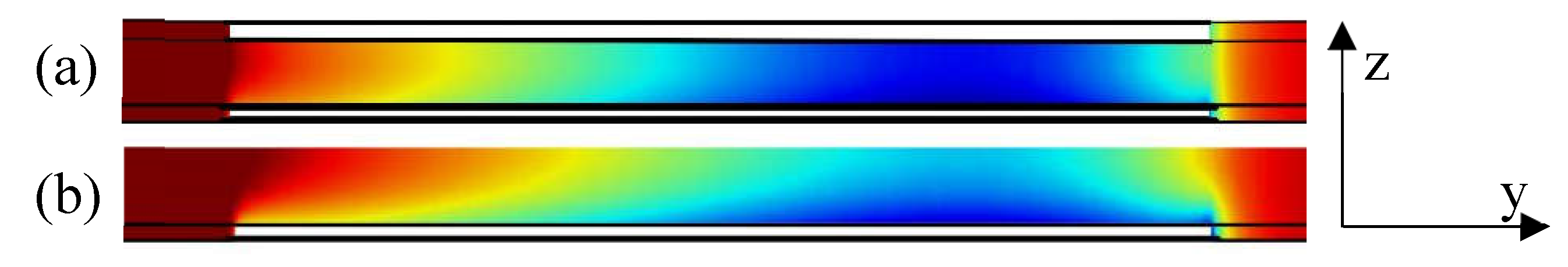

3.4. Simulated concentration profiles

3.5. SEM imaging

3.6. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Angelaalincy, M.J.; Navanietha Krishnaraj, R.; Shakambari, G.; Ashokkumar, B.; Kathiresan, S.; Varalakshmi, P. Biofilm engineering approaches for improving the performance of microbial fuel cells and bioelectrochemical systems. Frontiers in Energy Research 2018, 6, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, S.; Sinharoy, A.; Pakshirajan, K.; Lens, P.N. Algae based microbial fuel cells for wastewater treatment and recovery of value-added products. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2020, 132, 110041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asim, A.Y.; Mohamad, N.; Khalid, U.; Tabassum, P.; Akil, A.; Lokhat, D.; Siti, H. A glimpse into the microbial fuel cells for wastewater treatment with energy generation. Desalination and Water Treatment 2021, 214, 379–389. [Google Scholar]

- Gul, H.; Raza, W.; Lee, J.; Azam, M.; Ashraf, M.; Kim, K.-H. Progress in microbial fuel cell technology for wastewater treatment and energy harvesting. Chemosphere 2021, 281, 130828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khandaker, S.; Das, S.; Hossain, M.T.; Islam, A.; Miah, M.R.; Awual, M.R. Sustainable approach for wastewater treatment using microbial fuel cells and green energy generation–A comprehensive review. Journal of molecular liquids 2021, 344, 117795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Cupa, C.; Hu, Y.; Xu, C.; Bassi, A. An overview of microbial fuel cell usage in wastewater treatment, resource recovery and energy production. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 754, 142429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gude, V.G. Integrating bioelectrochemical systems for sustainable wastewater treatment. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy 2018, 20, 911–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varjani, S. Prospective review on bioelectrochemical systems for wastewater treatment: Achievements, hindrances and role in sustainable environment. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 841, 156691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Zhang, J.; Pi, J.; Gong, L.; Zhu, G. Long-term electricity generation and denitrification performance of MFCs with different exchange membranes and electrode materials. Bioelectrochemistry 2021, 140, 107748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Cai, Y.; Yang, X.-L.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Y.-L.; Song, H.-L. Microbial fuel cell-membrane bioreactor integrated system for wastewater treatment and bioelectricity production: overview. Journal of Environmental Engineering 2020, 146, 04019092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohyudin, S.; Farooq, R.; Jubeen, F.; Rasheed, T.; Fatima, M.; Sher, F. Microbial fuel cells a state-of-the-art technology for wastewater treatment and bioelectricity generation. Environ Res 2022, 204 (Pt D), 112387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saran, C.; Purchase, D.; Saratale, G.D.; Saratale, R.G.; Ferreira, L.F.R.; Bilal, M.; Iqbal, H.M.; Hussain, C.M.; Mulla, S.I.; Bharagava, R.N. Microbial fuel cell: A green eco-friendly agent for tannery wastewater treatment and simultaneous bioelectricity/power generation. Chemosphere 2023, 312, 137072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cecconet, D.; Sabba, F.; Devecseri, M.; Callegari, A.; Capodaglio, A.G. In situ groundwater remediation with bioelectrochemical systems: A critical review and future perspectives. Environment international 2020, 137, 105550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernando, E.Y.; Keshavarz, T.; Kyazze, G. The use of bioelectrochemical systems in environmental remediation of xenobiotics: a review. Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology 2019, 94, 2070–2080. [Google Scholar]

- Syed, Z.; Sogani, M.; Dongre, A.; Kumar, A.; Sonu, K.; Sharma, G.; Gupta, A.B. Bioelectrochemical systems for environmental remediation of estrogens: A review and way forward. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 780, 146544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidrich, E.; Dolfing, J.; Scott, K.; Edwards, S.; Jones, C.; Curtis, T. Production of hydrogen from domestic wastewater in a pilot-scale microbial electrolysis cell. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 2013, 97, 6979–6989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; An, J.; Wang, X.; Li, N. In-situ hydrogen peroxide synthesis with environmental applications in bioelectrochemical systems: a state-of-the-art review. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 3204–3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevda, S.; Garlapati, V.K.; Naha, S.; Sharma, M.; Ray, S.G.; Sreekrishnan, T.R.; Goswami, P. Biosensing capabilities of bioelectrochemical systems towards sustainable water streams: Technological implications and future prospects. Journal of bioscience and bioengineering 2020, 129, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Yu, W.; Graham, N.; Zhao, Y. Revisiting the bioelectrochemical system based biosensor for organic sensing and the prospect on constructed wetland-microbial fuel cell. Chemosphere 2021, 264, 128532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirdehi, M.A.; Khodaparastasgarabad, N.; Landari, H.; Zarabadi, M.P.; Miled, A.; Greener, J. A high-performance membraneless microfluidic microbial fuel cell for stable, long-term benchtop operation under strong flow. ChemElectroChem 2020, 7, 2227–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodaparastasgarabad, N.; Sonawane, J.M.; Baghernavehsi, H.; Gong, L.; Liu, L.; Greener, J. Microfluidic membraneless microbial fuel cells: new protocols for record power densities. Lab Chip 2023, 23, 4201–4212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, L.; Amirdehi, M.A.; Sonawane, J.M.; Jia, N.; de Oliveira, L.T.; Greener, J. Mainstreaming microfluidic microbial fuel cells: a biocompatible membrane grown in situ improves performance and versatility. Lab on a Chip 2022, 22, 1905–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarabadi, M.P.; Couture, M.; Charette, S.J.; Greener, J. A generalized kinetic framework applied to whole-cell bioelectrocatalysis in bioflow reactors clarifies performance enhancements for geobacter sulfurreducens biofilms. ChemElectroChem 2019, 6, 2715–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarabadi, M.P.; Charette, S.J.; Greener, J. Flow-Based Deacidification of Geobacter sulfurreducens Biofilms Depends on Nutrient Conditions: a Microfluidic Bioelectrochemical Study. ChemElectroChem 2018, 5, 3645–3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Regan, J.M. Comparison of anode bacterial communities and performance in microbial fuel cells with different electron donors. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2007, 77, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, R.; Logan, B.E. Using an anion exchange membrane for effective hydroxide ion transport enables high power densities in microbial fuel cells. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirkosh, M.; Hojjat, Y.; Mardanpour, M.M. Evaluation and optimization of the Zn-based microfluidic microbial fuel cells to power various electronic devices. Biosensors and Bioelectronics: X 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justin, G.A.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, M.; Sclabassi, R. Biofuel cells: a possible power source for implantable electronic devices. In The 26th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, 2004; IEEE: Vol. 2, pp 4096-4099. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.H.; Ha, H.; Ahn, Y.; Liu, H. Performance of single-layer paper-based co-laminar flow microbial fuel cells. Journal of Power Sources 2023, 580, 233456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Lee, K.K.; Choi, S. A laminar-flow based microbial fuel cell array. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2017, 243, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.L.; Erbay, C.; Sadr, R.; Han, A. Dynamic flow characteristics and design principles of laminar flow microbial fuel cells. Micromachines 2018, 9, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.-M.; Ha, H.; Ahn, Y. Co-laminar Microfluidic Microbial Fuel Cell Integrated with Electrophoretically Deposited Carbon Nanotube Flow-Over Electrode. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2022, 10, 1839–1846. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, L.; Khodaparastasgarabad, N.; Hall, D.M.; Greener, J. A new angle to control concentration profiles at electroactive biofilm interfaces: Investigating a microfluidic perpendicular flow approach. Electrochimica Acta 2022, 431, 141071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirdehi, M.A.; Gong, L.; Khodaparastasgarabad, N.; Sonawane, J.M.; Logan, B.E.; Greener, J. Hydrodynamic interventions and measurement protocols to quantify and mitigate power overshoot in microbial fuel cells using microfluidics. Electrochimica Acta 2022, 405, 139771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonawane, J.M.; Greener, J. Multiparameter optimization of microbial fuel cell outputs using linear sweep voltammetry and microfluidics. Journal of Power Sources 2024, 607, 234589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaglia, G.; Gerosa, M.; Agostino, V.; Cingolani, A.; Sacco, A.; Saracco, G.; Margaria, V.; Quaglio, M. Fluid dynamic modeling for microbial fuel cell based biosensor optimization. Fuel Cells 2017, 17, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardanpour, M.M.; Yaghmaei, S.; Kalantar, M. Modeling of microfluidic microbial fuel cells using quantitative bacterial transport parameters. Journal of Power Sources 2017, 342, 1017–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ye, D.; Li, J.; Zhu, X.; Liao, Q.; Zhang, B. Microfluidic microbial fuel cells: from membrane to membrane free. Journal of Power Sources 2016, 324, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, R.; Logan, B.E. Unraveling the contributions of internal resistance components in two-chamber microbial fuel cells using the electrode potential slope analysis. Electrochimica Acta 2020, 348, 136291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zarabadi, M.; Hall, D.; Dahal, S.; Greener, J.; Yang, L. Unification of cell-scale metabolic activity with biofilm behavior by integration of advanced flow and reactive-transport modeling and microfluidic experiments. bioRxiv, 2024; 2024.2001. 2025.577134. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Z.; Li, J.; Xiao, L.; Tong, Y.; He, Z. Recovery of electrical energy in microbial fuel cells: brief review. Environmental Science & Technology Letters 2014, 1, 137–141. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y. Effect of gravitational deposition on biofilm formation and development. Biofilms 2006, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, S.; Brodie, E.; Matin, A. Role and regulation of σs in general resistance conferred by low-shear simulated microgravity in Escherichia coli. Journal of bacteriology 2004, 186, 8207–8212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, J.W.; Ramamurthy, R.; Porwollik, S.; McClelland, M.; Hammond, T.; Allen, P.; Ott, C.M.; Pierson, D.L.; Nickerson, C.A. Microarray analysis identifies Salmonella genes belonging to the low-shear modeled microgravity regulon. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2002, 99, 13807–13812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logan, B.; Cheng, S.; Watson, V.; Estadt, G. Graphite fiber brush anodes for increased power production in air-cathode microbial fuel cells. Environmental science & technology 2007, 41, 3341–3346. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, B.; Yu, N.; Akbari, A.; Shi, L.; Zhou, X.; Xie, C.; Saikaly, P.E.; Logan, B.E. Using a non-precious metal catalyst for long-term enhancement of methane production in a zero-gap microbial electrosynthesis cell. Water Research 2024, 259, 121815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.; Chae, J. Optimal biofilm formation and power generation in a micro-sized microbial fuel cell (MFC). Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 2013, 195, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Lee, H.-S.; Yang, Y.; Parameswaran, P.; Torres, C.I.; Rittmann, B.E.; Chae, J. A μL-scale micromachined microbial fuel cell having high power density. Lab on a Chip 2011, 11, 1110–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Venkataraman, A.; Rosenbaum, M.A.; Angenent, L.T. A Laminar-Flow Microfluidic Device for Quantitative Analysis of Microbial Electrochemical Activity. ChemSusChem 2012, 5, 1119–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, D.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhu, X.; Liao, Q.; Deng, B.; Chen, R. Performance of a microfluidic microbial fuel cell based on graphite electrodes. international journal of hydrogen energy 2013, 38, 15710–15715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ye, D.; Li, J.; Zhu, X.; Liao, Q.; Zhang, B. Biofilm distribution and performance of microfluidic microbial fuel cells with different microchannel geometries. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 11983–11988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zheng, Z.; Yang, B.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Lei, L. A laminar-flow based microfluidic microbial three-electrode cell for biosensing. Electrochimica Acta 2016, 199, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).