Submitted:

03 July 2024

Posted:

04 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

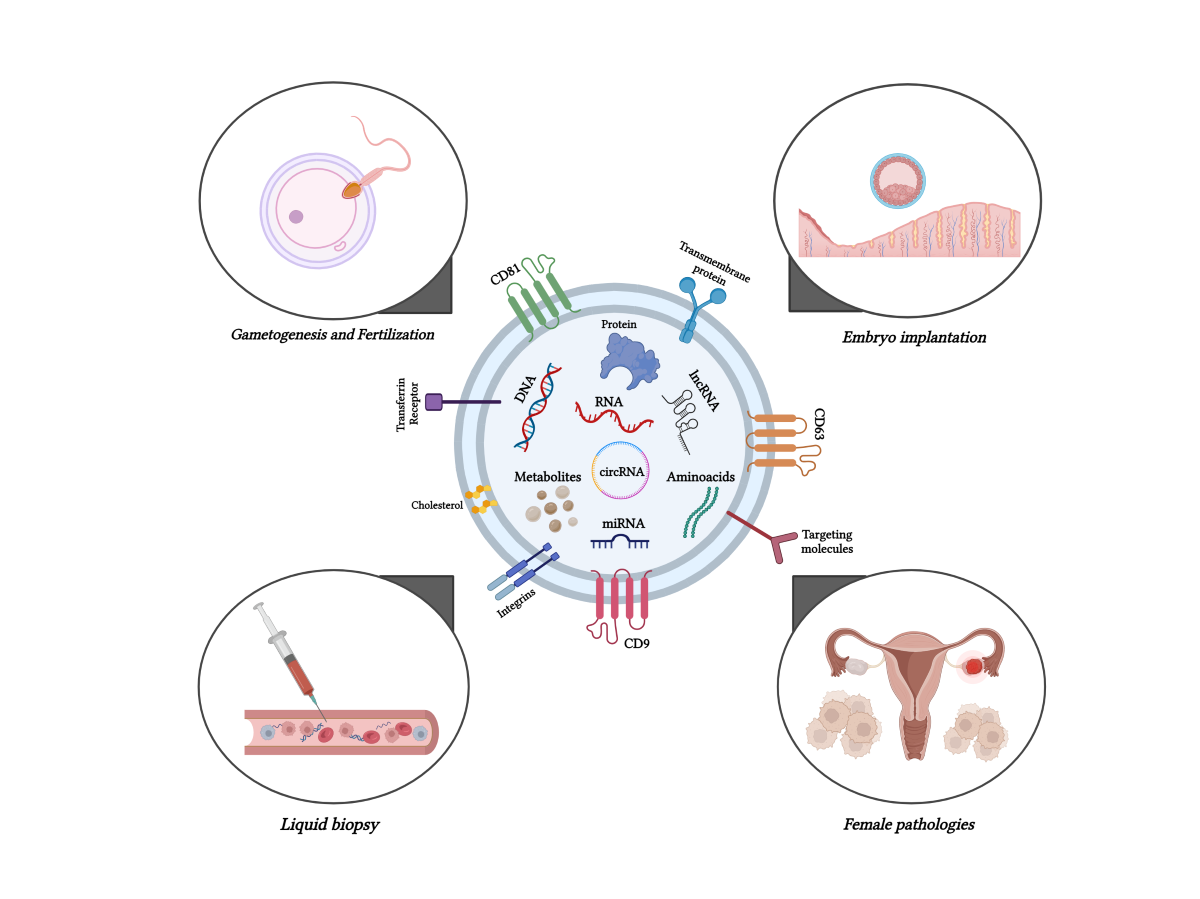

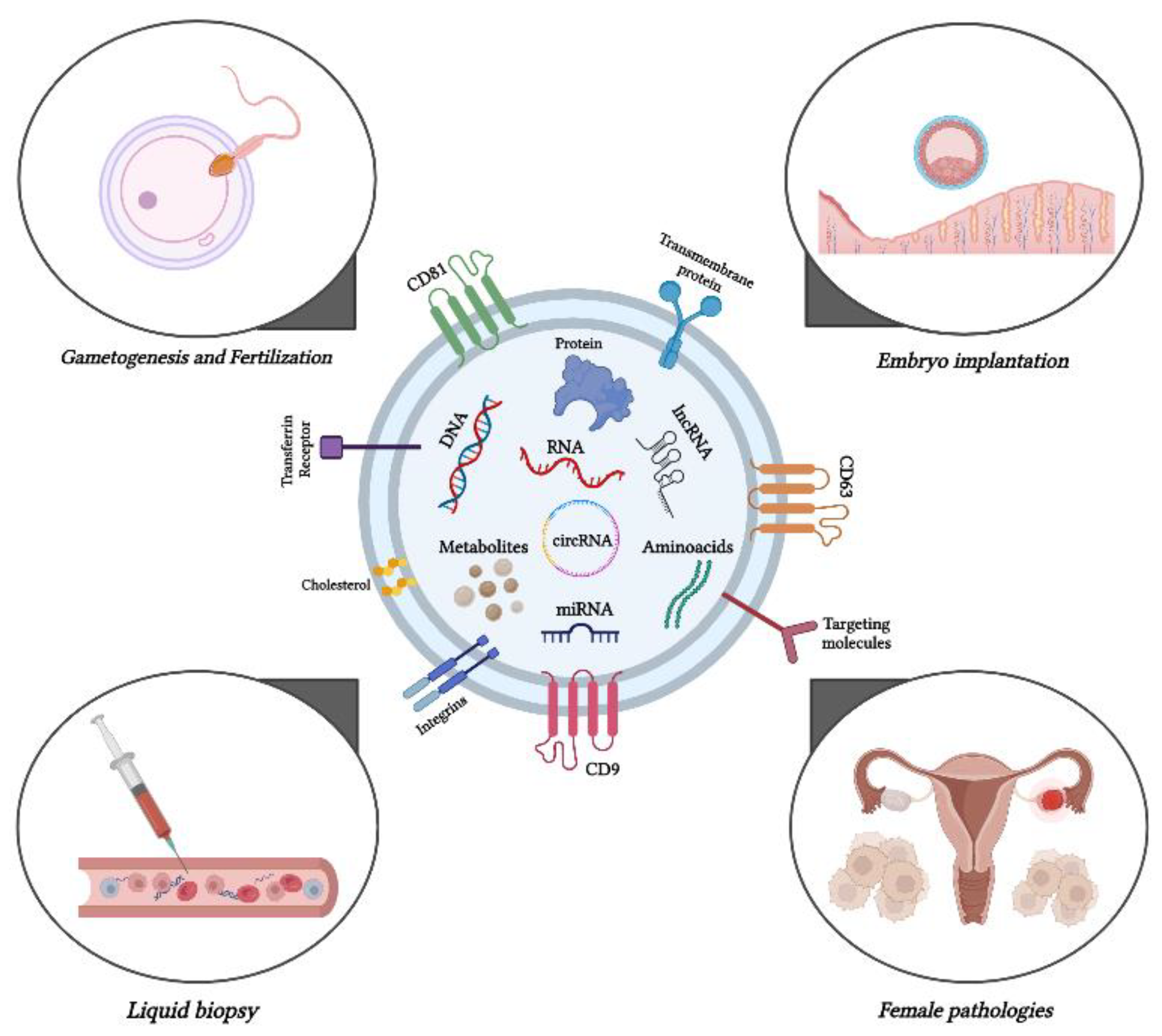

1. Introduction

2. Exploring the activity of exosomes in gametogenesis and fertilization

3. Exosomes and embryo implantation

4. Exosomes involved in female pathologies

5. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, B.H.; Parent, C.A.; Weaver, A.M. Extracellular vesicles: Critical players during cell migration. Dev. Cell 2021, 56, 1861–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginini, L.; Billan, S.; Fridman, E.; Gil, Z. Insight into Extracellular Vesicle-Cell Communication: From Cell Recognition to Intracellular Fate. Cells 2022, 11, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yáñez-Mó, M.; Siljander, P.R.-M.; Andreu, Z.; Bedina Zavec, A.; Borràs, F.E.; Buzas, E.I.; Buzas, K.; Casal, E.; Cappello, F.; Carvalho, J.; et al. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 27066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Bella, M. A. , Overview and Update on Extracellular Vesicles: Considerations on Exosomes and Their Application in Modern Medicine. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11, (6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willms, E.; Cabañas, C.; Mäger, I.; Wood, M.J.A.; Vader, P. Extracellular Vesicle Heterogeneity: Subpopulations, Isolation Techniques, and Diverse Functions in Cancer Progression. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramowicz, A.; Widłak, P.; Pietrowska, M. Different Types of Cellular Stress Affect the Proteome Composition of Small Extracellular Vesicles: A Mini Review. Proteomes 2019, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menck, K.; Bleckmann, A.; Schulz, M.; Ries, L.; Binder, C. , Isolation and Characterization of Microvesicles from Peripheral Blood. J Vis Exp 2017, (119).

- Yu, L.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, Y.; Zeng, L.; Xu, Z.; Weng, J.; Xia, J.; Li, J.; Pathak, J.L. Apoptotic bodies: bioactive treasure left behind by the dying cells with robust diagnostic and therapeutic application potentials. J. Nanobiotechnology 2023, 21, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajput, A.; Varshney, A.; Bajaj, R.; Pokharkar, V. Exosomes as New Generation Vehicles for Drug Delivery: Biomedical Applications and Future Perspectives. Molecules 2022, 27, 7289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andronico, F.; Battaglia, R.; Ragusa, M.; Barbagallo, D.; Purrello, M.; Di Pietro, C. Extracellular Vesicles in Human Oogenesis and Implantation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Ji, J.; Jin, D.; Wu, Y.; Wu, T.; Lin, R.; Zhu, S.; Jiang, F.; Ji, Y.; Bao, B.; et al. The biogenesis and secretion of exosomes and multivesicular bodies (MVBs): Intercellular shuttles and implications in human diseases. Genes Dis. 2023, 10, 1894–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, K.H.W.; Krzyzaniak, O.; Al Hrout, A.; Peacock, B.; Chahwan, R. Assessing Extracellular Vesicles in Human Biofluids Using Flow-Based Analyzers. Adv. Heal. Mater. 2023, 12, e2301706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvani, R.; Picca, A.; Guerra, F.; Coelho-Junior, H.J.; Bucci, C.; Marzetti, E. Circulating extracellular vesicles: friends and foes in neurodegeneration. Neural Regen. Res. 2022, 17, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hánělová, K.; Raudenská, M.; Masařík, M.; Balvan, J. Protein cargo in extracellular vesicles as the key mediator in the progression of cancer. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donoso-Quezada, J.; Ayala-Mar, S.; González-Valdez, J. The role of lipids in exosome biology and intercellular communication: Function, analytics and applications. Traffic 2021, 22, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Jang, H.; Cho, H.; Choi, J.; Hwang, K.Y.; Choi, Y.; Kim, S.H.; Yang, Y. Recent Advances in Exosome-Based Drug Delivery for Cancer Therapy. Cancers 2021, 13, 4435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnstone, R.M.; Adam, M.; Hammond, J.R.; Orr, L.; Turbide, C. Vesicle formation during reticulocyte maturation. Association of plasma membrane activities with released vesicles (exosomes). J. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262, 9412–9420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghafourian, M.; Mahdavi, R.; Jonoush, Z.A.; Sadeghi, M.; Ghadiri, N.; Farzaneh, M.; Salehi, A.M. The implications of exosomes in pregnancy: emerging as new diagnostic markers and therapeutics targets. Cell Commun. Signal. 2022, 20, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.-Y.; Liu, S.-P.; Dai, X.-F.; Lan, D.-F.; Song, T.; Wang, X.-Y.; Kong, Q.-H.; Tan, J.; Zhang, J.-D. The emerging role of exosomes in the development of testicular. Asian J. Androl. 2023, 25, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, A.E.; Sneider, A.; Witwer, K.W.; Bergese, P.; Bhattacharyya, S.N.; Cocks, A.; Cocucci, E.; Erdbrügger, U.; Falcon-Perez, J.M.; Freeman, D.W.; et al. Biological membranes in EV biogenesis, stability, uptake, and cargo transfer: an ISEV position paper arising from the ISEV membranes and EVs workshop. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1684862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, A.A.; Battaglia, R.; Morganti, D.; Faro, M.J.L.; Fazio, B.; De Pascali, C.; Francioso, L.; Palazzo, G.; Mallardi, A.; Purrello, M.; et al. A Novel Silicon Platform for Selective Isolation, Quantification, and Molecular Analysis of Small Extracellular Vesicles. Int. J. Nanomed. 2021, ume 16, 5153–5165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Théry, C.; Witwer, K.W.; Aikawa, E.; Alcaraz, M.J.; Anderson, J.D.; Andriantsitohaina, R.; Antoniou, A.; Arab, T.; Archer, F.; Atkin-Smith, G.K.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): A position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1535750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, J. A.; Goberdhan, D. C. I.; O'Driscoll, L.; Buzas, E. I.; Blenkiron, C.; Bussolati, B.; Cai, H.; Di Vizio, D.; Driedonks, T. A. P.; Erdbrugger, U.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (MISEV2023): From basic to advanced approaches. J Extracell Vesicles 2024, 13, e12404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konoshenko, M.Y.; Lekchnov, E.A.; Vlassov, A.V.; Laktionov, P.P. Isolation of Extracellular Vesicles: General Methodologies and Latest Trends. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 8545347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reclusa, P.; Verstraelen, P.; Taverna, S.; Gunasekaran, M.; Pucci, M.; Pintelon, I.; Claes, N.; de Miguel-Pérez, D.; Alessandro, R.; Bals, S.; et al. Improving extracellular vesicles visualization: From static to motion. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szatanek, R.; Baj-Krzyworzeka, M.; Zimoch, J.; Lekka, M.; Siedlar, M.; Baran, J. The Methods of Choice for Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) Characterization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schageman, J.; Zeringer, E.; Li, M.; Barta, T.; Lea, K.; Gu, J.; Magdaleno, S.; Setterquist, R.; Vlassov, A.V. The Complete Exosome Workflow Solution: From Isolation to Characterization of RNA Cargo. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovičová, J.; Sečová, P.; Michalková, K.; Antalíková, J. Tetraspanins, More than Markers of Extracellular Vesicles in Reproduction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lyden, D. Asymmetric-flow field-flow fractionation technology for exomere and small extracellular vesicle separation and characterization. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 1027–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020, 367, eaau6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.; Im, H.; Castro, C.M.; Breakefield, X.; Weissleder, R.; Lee, H. New Technologies for Analysis of Extracellular Vesicles. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 1917–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Ren, W.; Wang, W.; Han, W.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, D.; Guo, M. Exosomal targeting and its potential clinical application. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2021, 12, 2385–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, A.; Costa-Silva, B.; Shen, T.-L.; Rodrigues, G.; Hashimoto, A.; Mark, M.T.; Molina, H.; Kohsaka, S.; Di Giannatale, A.; Ceder, S.; et al. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature 2015, 527, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, S.; Iinuma, H.; Wada, K.; Takahashi, K.; Minezaki, S.; Kainuma, M.; Shibuya, M.; Miura, F.; Sano, K. , Exosome-encapsulated microRNA-4525, microRNA-451a and microRNA-21 in portal vein blood is a high-sensitive liquid biomarker for the selection of high-risk pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2019, 26, (2), 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Janku, F.; Zhan, Q.; Fan, J.-B. Accessing Genetic Information with Liquid Biopsies. Trends Genet. 2015, 31, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadi, H.; Ekström, K.; Bossios, A.; Sjöstrand, M.; Lee, J.J.; Lötvall, J.O. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Li, P.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, M. , Insights Into Exosomal Non-Coding RNAs Sorting Mechanism and Clinical Application. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 664904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Gu, J.; Xu, W.; Cai, H.; Fang, X.; Zhang, X. Exosomes as a new frontier of cancer liquid biopsy. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irmer, B.; Chandrabalan, S.; Maas, L.; Bleckmann, A.; Menck, K. Extracellular Vesicles in Liquid Biopsies as Biomarkers for Solid Tumors. Cancers 2023, 15, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Kaslan, M.; Lee, S.H.; Yao, J.; Gao, Z. Progress in Exosome Isolation Techniques. Theranostics 2017, 7, 789–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Zheng, S.; Luo, Y.; Wang, B. Exosome Theranostics: Biology and Translational Medicine. Theranostics 2018, 8, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwar, S.S.; Dunlay, C.J.; Simeone, D.M.; Nagrath, S. Microfluidic device (ExoChip) for on-chip isolation, quantification and characterization of circulating exosomes. Lab a Chip 2014, 14, 1891–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, A.; Wrzecińska, M.; Czerniawska-Piątkowska, E.; Kupczyński, R. Exosomes – Spectacular role in reproduction. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 148, 112752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, Z.; Gu, X.; Sheng, X.; Xiao, L.; Wang, X. Exosomes: New regulators of reproductive development. Mater. Today Bio 2023, 19, 100608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machtinger, R.; Laurent, L.C.; Baccarelli, A.A. Extracellular vesicles: roles in gamete maturation, fertilization and embryo implantation. Hum. Reprod. Update 2016, 22, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamar, A.Y.; Mahiddine, F.Y.; Bang, S.; Fang, X.; Shin, S.T.; Kim, M.J.; Cho, J. Extracellular Vesicle Mediated Crosstalk Between the Gametes, Conceptus, and Female Reproductive Tract. Front. Veter- Sci. 2020, 7, 589117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capra, E.; Lange-Consiglio, A. , The Biological Function of Extracellular Vesicles during Fertilization, Early Embryo-Maternal Crosstalk and Their Involvement in Reproduction: Review and Overview. Biomolecules 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksejeva, E.; Zarovni, N.; Dissanayake, K.; Godakumara, K.; Vigano, P.; Fazeli, A.; Jaakma, U.; Salumets, A. , Extracellular vesicle research in reproductive science: Paving the way for clinical achievementsdagger. Biol Reprod 2022, 106, 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervasi, M.G.; Visconti, P.E. Molecular changes and signaling events occurring in spermatozoa during epididymal maturation. Andrology 2017, 5, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, R.; Saez, F.; Girouard, J.; Frenette, G. Role of exosomes in sperm maturation during the transit along the male reproductive tract. Blood Cells, Mol. Dis. 2005, 35, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.Y.; Mruk, D.D. The Blood-Testis Barrier and Its Implications for Male Contraception. Pharmacol. Rev. 2011, 64, 16–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimmer, M.P.; Gregory, C.D.; Mitchell, R.T. The transformative impact of extracellular vesicles on developing sperm. Reprod. Fertil. 2021, 2, R51–R66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, N.; Mohammadi, P.; Allahgholi, A.; Salek, F.; Amini, E. The potential of sertoli cells (SCs) derived exosomes and its therapeutic efficacy in male reproductive disorders. Life Sci. 2023, 312, 121251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacheux, J.-L.; Belleannée, C.; Guyonnet, B.; Labas, V.; Teixeira-Gomes, A.-P.; Ecroyd, H.; Druart, X.; Gatti, J.-L.; Dacheux, F. The contribution of proteomics to understanding epididymal maturation of mammalian spermatozoa. Syst. Biol. Reprod. Med. 2012, 58, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belleannée, C. ; Calvo, ; Caballero, J.; Sullivan, R. Epididymosomes Convey Different Repertoires of MicroRNAs Throughout the Bovine EpididymisBiol. Reprod. 2013, 89, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, G.; Brody, I. The prostasome: its secretion and function in man. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Rev. Biomembr. 1985, 822, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, G.; Brody, I.; Gottfries, A.; Stegmayr, B. , An Mg2+ and Ca2+-stimulated adenosine triphosphatase in human prostatic fluid: part I. Andrologia 1978, 10, (4), 261–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist, K.G.; Ronquist, G.; Carlsson, L.; Larsson, A. Human prostasomes contain chromosomal DNA. Prostate 2009, 69, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagimachi, R.; Kamiguchi, Y.; Mikamo, K.; Suzuki, F.; Yanagimachi, H. Maturation of spermatozoa in the epididymis of the Chinese hamster. Am. J. Anat. 1985, 172, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, R.; Saez, F. Epididymosomes, prostasomes, and liposomes: their roles in mammalian male reproductive physiology. Reproduction 2013, 146, R21–R35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojtech, L.; Woo, S.; Hughes, S.; Levy, C.; Ballweber, L.; Sauteraud, R.P.; Strobl, J.; Westerberg, K.; Gottardo, R.; Tewari, M.; et al. Exosomes in human semen carry a distinctive repertoire of small non-coding RNAs with potential regulatory functions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 7290–7304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arienti, G.; Carlini, E.; Palmerini, C. Fusion of Human Sperm to Prostasomes at Acidic pH. J. Membr. Biol. 1997, 155, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arienti, G.; Carlini, E.; Nicolucci, A.; Cosmi, E.V.; Santi, F.; Palmerini, C.A. The motility of human spermatozoa as influenced by prostasomes at various pH levels. Biol. Cell 1999, 91, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, H.; Liang, J.; Mei, J.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, L.; Luo, J.; Tang, Y.; Huang, R.; Xia, H.; et al. Sertoli cell-derived exosomal MicroRNA-486-5p regulates differentiation of spermatogonial stem cell through PTEN in mice. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 3950–3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, R.-L.; Song, W.-P.; Gu, S.-J.; Tan, X.-H.; Gu, Y.-Y.; Song, W.-D.; Zeng, J.-Y.; Xin, Z.-C. Proteomic analysis and miRNA profiling of human testicular endothelial cell-derived exosomes: the potential effects on spermatogenesis. Asian J. Androl. 2021, 24, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Huetos, A.; James, E.R.; Aston, K.I.; Carrell, D.T.; Jenkins, T.G.; Yeste, M. The role of miRNAs in male human reproduction: a systematic review. Andrology 2019, 8, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Broi, M.G.; Giorgi, V.S.I.; Wang, F.; Keefe, D.L.; Albertini, D.; Navarro, P.A. Influence of follicular fluid and cumulus cells on oocyte quality: clinical implications. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2018, 35, 735–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppig, J.J.; Chesnel, F.; Hirao, Y.; O'Brien, M.J.; Pendola, F.L.; Watanabe, S.; Wigglesworth, K. Oocyte control of granulosa cell development: how and why. . 1997, 12, 127–32. [Google Scholar]

- Matzuk, M.M.; Burns, K.H.; Viveiros, M.M.; Eppig, J.J. Intercellular Communication in the Mammalian Ovary: Oocytes Carry the Conversation. Science 2002, 296, 2178–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buccione, R.; Schroeder, A.C.; Eppig, J.J. Interactions between Somatic Cells and Germ Cells Throughout Mammalian OogenesisBiol. Reprod. 1990, 43, 543–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adashi, E. Y. Endocrinology of the ovary. Hum Reprod 1994, 9, 815–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senbon, S.; Hirao, Y.; Miyano, T. Interactions between the Oocyte and Surrounding Somatic Cells in Follicular Development: Lessons from In Vitro Culture. J. Reprod. Dev. 2003, 49, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, M.; Dufort, I.; Robert, C.; Gravel, C.; Leveille, M.-C.; Leader, A.; Sirard, M.-A. Identification of differentially expressed markers in human follicular cells associated with competent oocytes. Hum. Reprod. 2008, 23, 1118–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, C. Exosome-mediated communication in the ovarian follicle. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2016, 33, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silveira, J.C.; Veeramachaneni, D.R.; Winger, Q.A.; Carnevale, E.M.; Bouma, G.J. Cell-Secreted Vesicles in Equine Ovarian Follicular Fluid Contain miRNAs and Proteins: A Possible New Form of Cell Communication Within the Ovarian Follicle1. Biol. Reprod. 2012, 86, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santonocito, M.; Vento, M.; Guglielmino, M.R.; Battaglia, R.; Wahlgren, J.; Ragusa, M.; Barbagallo, D.; Borzì, P.; Rizzari, S.; Maugeri, M.; et al. Molecular characterization of exosomes and their microRNA cargo in human follicular fluid: bioinformatic analysis reveals that exosomal microRNAs control pathways involved in follicular maturation. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 102, 1751–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, W.-T.; Hong, X.; Christenson, L.K.; McGinnis, L.K. Extracellular Vesicles from Bovine Follicular Fluid Support Cumulus Expansion1. Biol. Reprod. 2015, 93, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silveira, J.C.; de Ávila, A.C.F.C.M.; Garrett, H.L.; E Bruemmer, J.; A Winger, Q.; Bouma, G.J. Cell-secreted vesicles containing microRNAs as regulators of gamete maturation. J. Endocrinol. 2018, 236, R15–R27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Fraile, A.; Lammens, T.; Tilleman, K.; Witkowski, W.; Verhasselt, B.; De Sutter, P.; Benoit, Y.; Espeel, M.; D'Herde, K. , Age-associated differential microRNA levels in human follicular fluid reveal pathways potentially determining fertility and success of in vitro fertilization. Hum Fertil (Camb) 2014, 17, (2), 90–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, G.S.; Galileo, D.S.; Aravindan, R.G.; Martin-DeLeon, P.A. Clusterin Facilitates Exchange of Glycosyl Phosphatidylinositol-Linked SPAM1 Between Reproductive Luminal Fluids and Mouse and Human Sperm Membranes1. Biol. Reprod. 2009, 81, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdica, V.; Giacomini, E.; Alteri, A.; Bartolacci, A.; Cermisoni, G.C.; Zarovni, N.; Papaleo, E.; Montorsi, F.; Salonia, A.; Viganò, P.; et al. Seminal plasma of men with severe asthenozoospermia contain exosomes that affect spermatozoa motility and capacitation. Fertil. Steril. 2019, 111, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharazi, U.; Badalzadeh, R. A review on the stem cell therapy and an introduction to exosomes as a new tool in reproductive medicine. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 20, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskaran, S.; Panner Selvam, M. K.; Agarwal, A. , Exosomes of male reproduction. Adv Clin Chem 2020, 95, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Franasiak, J.M.; Alecsandru, D.; Forman, E.J.; Gemmell, L.C.; Goldberg, J.M.; Llarena, N.; Margolis, C.; Laven, J.; Schoenmakers, S.; Seli, E. A review of the pathophysiology of recurrent implantation failure. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 116, 1436–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehring, J.; Beltsos, A.; Jeelani, R. Human implantation: The complex interplay between endometrial receptivity, inflammation, and the microbiome. Placenta 2021, 117, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Qi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yan, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. Messenger roles of extracellular vesicles during fertilization of gametes, development and implantation: Recent advances. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 10, 1079387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomini, E.; Alleva, E.; Fornelli, G.; Quartucci, A.; Privitera, L.; Vanni, V.S.; Viganò, P. Embryonic extracellular vesicles as informers to the immune cells at the maternal–fetal interface. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2019, 198, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, K.; Kook, H.; Kang, S.; Lee, J. Study of immune-tolerized cell lines and extracellular vesicles inductive environment promoting continuous expression and secretion of HLA-G from semiallograft immune tolerance during pregnancy. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulmer, J.N.; Morrison, L.; Longfellow, M.; Ritson, A.; Pace, D. Granulated lymphocytes in human endometrium: histochemical and immunohistochemical studies. Hum. Reprod. 1991, 6, 791–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quenby, S.; Bates, M.; Doig, T.; Brewster, J.; Lewis-Jones, D.; Johnson, P.; Vince, G. Pre-implantation endometrial leukocytes in women with recurrent miscarriage. Hum. Reprod. 1999, 14, 2386–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-M.; Chen, L.-H.; Hsu, L.-T.; Lai, C.-H. Immune Tolerance of Embryo Implantation and Pregnancy: The Role of Human Decidual Stromal Cell- and Embryonic-Derived Extracellular Vesicles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminski, V.d.L.; Ellwanger, J.H.; Chies, J.A.B. Extracellular vesicles in host-pathogen interactions and immune regulation — exosomes as emerging actors in the immunological theater of pregnancy. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czernek, L.; Düchler, M. Exosomes as Messengers between Mother and Fetus in Pregnancy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Kusama, K.; Ideta, A.; Kimura, K.; Hori, M.; Imakawa, K. Effects of miR-98 in intrauterine extracellular vesicles on maternal immune regulation during the peri-implantation period in cattle. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, K.; Kusama, K.; Hori, M.; Imakawa, K. , The effect of bta-miR-26b in intrauterine extracellular vesicles on maternal immune system during the implantation period. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2021, 573, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poh, Q.H.; Rai, A.; Salamonsen, L.A.; Greening, D.W. Omics insights into extracellular vesicles in embryo implantation and their therapeutic utility. Proteomics 2023, 23, e2200107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallinger, E.; Bognar, Z.; Bogdan, A.; Csabai, T.; Abraham, H.; Szekeres-Bartho, J. PIBF+ extracellular vesicles from mouse embryos affect IL-10 production by CD8+ cells. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovács, .F.; Fekete, N.; Turiák, L.; Ács, A.; Kőhidai, L.; Buzás, E.I.; Pállinger. Unravelling the Role of Trophoblastic-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Regulatory T Cell Differentiation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.; Poh, Q.H.; Fatmous, M.; Fang, H.; Gurung, S.; Vollenhoven, B.; Salamonsen, L.A.; Greening, D.W. Proteomic profiling of human uterine extracellular vesicles reveal dynamic regulation of key players of embryo implantation and fertility during menstrual cycle. Proteomics 2021, 21, 2000211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, Y.; Mouillet, J.-F.; Coyne, C.; Sadovsky, Y. Review: Placenta-specific microRNAs in exosomes – Good things come in nano-packages. Placenta 2013, 35, S69–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguer-Dance, M.; Abu-Amero, S.; Al-Khtib, M.; Lefèvre, A.; Coullin, P.; Moore, G.E.; Cavaillé, J. The primate-specific microRNA gene cluster (C19MC) is imprinted in the placenta. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010, 19, 3566–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Sun, X.; Jiang, D.; Ding, Y.; Lu, Z.; Gong, L.; Liu, H.; Xie, J. Origin and evolution of a placental-specific microRNA family in the human genome. BMC Evol. Biol. 2010, 10, 346–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donker, R.B.; Mouillet, J.F.; Chu, T.; Hubel, C.A.; Stolz, D.B.; Morelli, A.E.; Sadovsky, Y. The expression profile of C19MC microRNAs in primary human trophoblast cells and exosomes. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2012, 18, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, S.-S.; Ishibashi, O.; Ishikawa, G.; Ishikawa, T.; Katayama, A.; Mishima, T.; Takizawa, T.; Shigihara, T.; Goto, T.; Izumi, A.; et al. Human Villous Trophoblasts Express and Secrete Placenta-Specific MicroRNAs into Maternal Circulation via Exosomes. Biol. Reprod. 2009, 81, 717–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Song, G.; Lim, W. Effects of extracellular vesicles on placentation and pregnancy disorders. Reproduction 2019, 158, R189–R196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kambe, S.; Yoshitake, H.; Yuge, K.; Ishida, Y.; Ali, M.; Takizawa, T.; Kuwata, T.; Ohkuchi, A.; Matsubara, S.; Suzuki, M.; et al. Human Exosomal Placenta-Associated miR-517a-3p Modulates the Expression of PRKG1 mRNA in Jurkat Cells1. Biol. Reprod. 2014, 91, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurian, N.K.; Modi, D. Extracellular vesicle mediated embryo-endometrial cross talk during implantation and in pregnancy. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2018, 36, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadeldin, I.; Oh, H.J; Lee, B. Embryonic–maternal cross-talk via exosomes: Potential implications. Stem Cells Clon. Adv. Appl. 2015, 8, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Y.H.; Rome, S.; Jalabert, A.; Forterre, A.; Singh, H.; Hincks, C.L.; Salamonsen, L.A. Endometrial Exosomes/Microvesicles in the Uterine Microenvironment: A New Paradigm for Embryo-Endometrial Cross Talk at Implantation. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e58502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Liang, J.; Qin, T.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, Z. The Role of Extracellular Vesicles in Embryo Implantation. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 809596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, R.T.; Upham, K.M.; Forman, E.J.; Zhao, T.; Treff, N.R. Cleavage-stage biopsy significantly impairs human embryonic implantation potential while blastocyst biopsy does not: a randomized and paired clinical trial. Fertil. Steril. 2013, 100, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomini, E.; Vago, R.; Sanchez, A.M.; Podini, P.; Zarovni, N.; Murdica, V.; Rizzo, R.; Bortolotti, D.; Candiani, M.; Viganò, P. Secretome of in vitro cultured human embryos contains extracellular vesicles that are uptaken by the maternal side. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhadarka, H.K.; Patel, N.H.; Patel, N.H.; Patel, M.; Patel, K.B.; Sodagar, N.R.; Phatak, A.G.; Patel, J.S. Impact of embryo co-culture with cumulus cells on pregnancy & implantation rate in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization using donor oocyte. 2017; 146, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallinger, E.; Bognar, Z.; Bodis, J.; Csabai, T.; Farkas, N.; Godony, K.; Varnagy, A.; Buzas, E.; Szekeres-Bartho, J. A simple and rapid flow cytometry-based assay to identify a competent embryo prior to embryo transfer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 39927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capalbo, A.; Ubaldi, F.M.; Cimadomo, D.; Noli, L.; Khalaf, Y.; Farcomeni, A.; Ilic, D.; Rienzi, L. MicroRNAs in spent blastocyst culture medium are derived from trophectoderm cells and can be explored for human embryo reproductive competence assessment. Fertil. Steril. 2015, 105, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbluth, E.M.; Shelton, D.N.; Wells, L.M.; Sparks, A.E.; Van Voorhis, B.J. Human embryos secrete microRNAs into culture media—a potential biomarker for implantation. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 101, 1493–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Halima, M.; Häusler, S.; Backes, C.; Fehlmann, T.; Staib, C.; Nestel, S.; Nazarenko, I.; Meese, E.; Keller, A. Micro-ribonucleic acids and extracellular vesicles repertoire in the spent culture media is altered in women undergoing In Vitro Fertilization. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13525–13525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battaglia, R.; Palini, S.; Vento, M.E.; La Ferlita, A.; Faro, M.J.L.; Caroppo, E.; Borzì, P.; Falzone, L.; Barbagallo, D.; Ragusa, M.; et al. Identification of extracellular vesicles and characterization of miRNA expression profiles in human blastocoel fluid. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Schjenken, J.; Panir, K.; A Robertson, S.; Hull, M.L. Exosome-mediated intracellular signalling impacts the development of endometriosis—new avenues for endometriosis research. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2018, 25, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Lian, Y.; Jiang, J.; Wang, L.; Ren, L.; Li, Y.; Yan, X.; Chen, Q. Differential expression of microRNA in exosomes derived from endometrial stromal cells of women with endometriosis-associated infertility. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2020, 41, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, R.; Xu, T.; Wang, J.; Cui, Z.; Cheng, F.; Wang, W.; Yang, X. Endometrial stem cell-derived exosomes repair cisplatin-induced premature ovarian failure via Hippo signaling pathway. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, R.; Hao, J.; Huang, X.; Liu, M.; Lv, M.; Su, C.; Mu, Y. L. , miRNA-122-5p in POI ovarian-derived exosomes promotes granulosa cell apoptosis by regulating BCL9. Cancer Med 2022, 11, (12), 2414–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandyari, S.; Elkafas, H.; Chugh, R.M.; Park, H.-S.; Navarro, A.; Al-Hendy, A. Exosomes as Biomarkers for Female Reproductive Diseases Diagnosis and Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobarak, H.; Rahbarghazi, R.; Lolicato, F.; Heidarpour, M.; Pashazadeh, F.; Nouri, M.; Mahdipour, M. Evaluation of the association between exosomal levels and female reproductive system and fertility outcome during aging: a systematic review protocol. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.-X.; Li, X.-L. The Complicated Effects of Extracellular Vesicles and Their Cargos on Embryo Implantation. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekanayake, D. L.; Malopolska, M. M.; Schwarz, T.; Tuz, R.; Bartlewski, P. M. , The roles and expression of HOXA/Hoxa10 gene: A prospective marker of mammalian female fertility? Reprod Biol 2022, 22, 100647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, H.; Taylor, H. S. , The Role of Hox Genes in Female Reproductive Tract Development, Adult Function, and Fertility. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2015, 6, a023002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimber, S.J. Leukaemia inhibitory factor in implantation and uterine biology. Reproduction 2005, 130, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, B.; Hu, J.; Ma, J.; Cui, L.; Chen, Z.-J. Differential expression profile of plasma exosomal microRNAs in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 115, 782–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Ouyang, Y.; Sadovsky, E.; Parks, W.T.; Chu, T.; Sadovsky, Y. Unique microRNA Signals in Plasma Exosomes from Pregnancies Complicated by Preeclampsia. Hypertension 2020, 75, 762–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.F.; Yan, S.; Wu, S.F. MicroRNA-153-3p suppress cell proliferation and invasion by targeting SNAI1 in melanoma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 487, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Guo, Q.; Li, L.; Cheng, Y.; Ren, C.; Zhang, G. MicroRNA-433 inhibits migration and invasion of ovarian cancer cells via targeting Notch1. Neoplasma 2016, 63, 696–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, A.S.; Bao, B.; Sarkar, F.H. Exosomes in cancer development, metastasis, and drug resistance: a comprehensive review. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2013, 32, 623–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Shen, H.; Yin, X.; Yang, M.; Wei, H.; Chen, Q.; Feng, F.; Liu, Y.; Xu, W.; Li, Y. Macrophages derived exosomes deliver miR-223 to epithelial ovarian cancer cells to elicit a chemoresistant phenotype. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Lu, W.; Qu, J.; Ye, L.; Du, G.; Wan, X. Loss of exosomal miR-148b from cancer-associated fibroblasts promotes endometrial cancer cell invasion and cancer metastasis. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 234, 2943–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Shen, W. , Extracellular vesicle encapsulated microRNA-320a inhibits endometrial cancer by suppression of the HIF1alpha/VEGFA axis. Exp Cell Res 2020, 394, 112113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).