Submitted:

03 July 2024

Posted:

04 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Datasets

2.2. Preprocessing

- Loading the Dataset: The first step involves loading the datasets. This is done by accessing the data files containing the EEG recordings, metadata, and necessary labels. For both the Nakanishi2015 and Lee2019_SSVEP datasets, we use appropriate functions to load the data into our working environment.

- Fetching Data: Once the datasets are loaded, we fetch the raw EEG data, associated labels, and metadata. This includes extracting the dataset’s EEG signal values, trial information, and class labels.

- Creating MNE Info Structure: Using the MNE-Python library, we create an info structure that contains metadata about the EEG data, such as the names of the channels, the sampling rate, and the type of data (e.g., EEG, stim). This info structure is essential for further processing and analysis using MNE functions.

- Reshaping Data for MNE RawArray: The EEG data is reshaped to fit the format required by the MNE RawArray object. This involves organizing the data into a 2D array where each row represents a channel, and each column represents a time point.

- Setting Montage: We set the montage, which defines the spatial arrangement of the EEG electrodes on the scalp. The standard 10-20 system ensures accurate spatial representation of the EEG data.

- Setting Common Average Reference: A common average reference (CAR) is applied to the EEG data. This involves re-referencing the data by subtracting the average of all channels from each channel. CAR helps reduce the influence of common noise and improve signal quality.

- Applying Bandpass Filter: A bandpass filter is applied to the EEG data to retain only the frequencies of interest. For SSVEP data, this typically involves filtering the data to keep frequencies within the range of the SSVEP stimuli (4-16 Hz). This step helps in removing noise and irrelevant frequency components.

- Normalizing the EEG Data: Normalization is performed to standardize the EEG data, ensuring all signals have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. This step reduces variability due to different measurement scales and improves the performance of subsequent analysis methods. While it is acknowledged that this process may lead to the loss of information regarding possible differences in EEG amplitude distribution on the scalp, the benefits of normalization, such as improved comparability and enhanced performance of ML algorithms, outweigh this limitation. Furthermore, advanced techniques could be explored in future work to preserve some amplitude distribution information while still achieving the desired standardization.

- Creating Event Array: An event array is created to mark specific events in the EEG data, such as the onset of a stimulus. This array is essential for segmenting the continuous EEG data into epochs corresponding to individual trials.

- Creating Epochs: The continuous EEG data is segmented into epochs, time-locked segments around the events of interest (the presentation of SSVEP stimuli). Each epoch corresponds to a single trial and contains the EEG data from a specified time window around the event.

- Creating Reference Signals: Reference signals for the SSVEP stimuli are created based on the known flicker frequencies. These reference signals are used for subsequent analysis and classification of the SSVEP responses.

- Reshaping Data for CNN: The EEG data epochs are reshaped into a format suitable for input to a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). This typically involves organizing the data into 3D arrays where each dimension represents time points, channels, and epochs.

- Mapping Frequency Labels to Numerical Indices: The frequency labels associated with the SSVEP stimuli are mapped to numerical indices to facilitate their use in Deep Learning (DL) algorithms. Each unique frequency is assigned a distinct numerical index.

- Converting Labels to One-Hot Encoding: The numerical labels are converted to one-hot encoding, a binary representation of categorical data. This step is necessary for training the CNN, allowing the network to output probabilities for each class.

- Splitting Data into Training and Testing Sets: Finally, the preprocessed data is split into training (80%) and testing (20%) sets. This ensures that the model can be trained on one subset of the data and evaluated on another unseen subset, enabling an unbiased assessment of its performance.

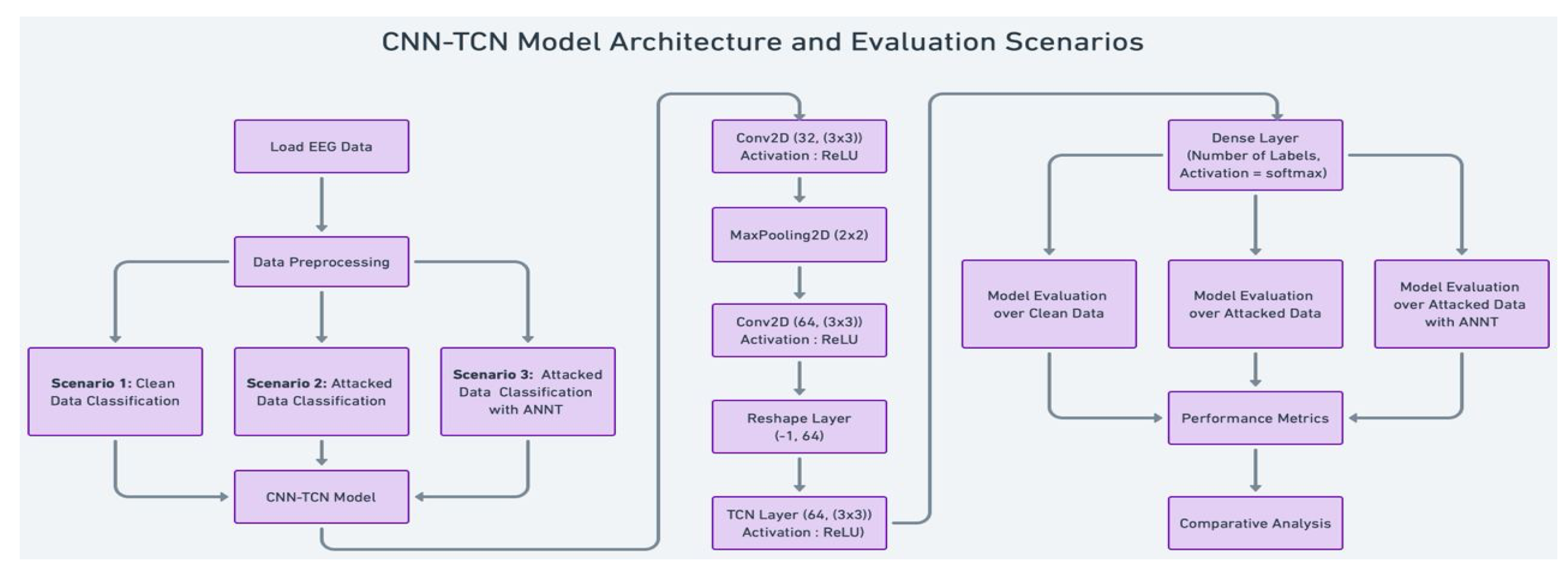

2.3. System Model

-

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- –

- We start by loading the SSVEP EEG data from our chosen datasets, Nakanishi2015 and Lee2019_SSVEP.

- –

- Data preprocessing is done as described in the previous section.

-

Convolutional Neural Network (CNN):

- –

- The first layer is a Conv2D layer with 32 filters and a (3x3) kernel size, followed by a ReLU activation function.

- –

- This is followed by a MaxPooling2D layer with a (2x2) pool size to reduce the spatial dimensions.

- –

- Another Conv2D layer with 64 filters and a (3x3) kernel size, again with ReLU activation, is applied to extract more complex features.

- Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN): The reshaped data is passed through a TCN layer with 64 filters and a (3x3) kernel size, focusing on capturing the temporal dependencies in the EEG signals.

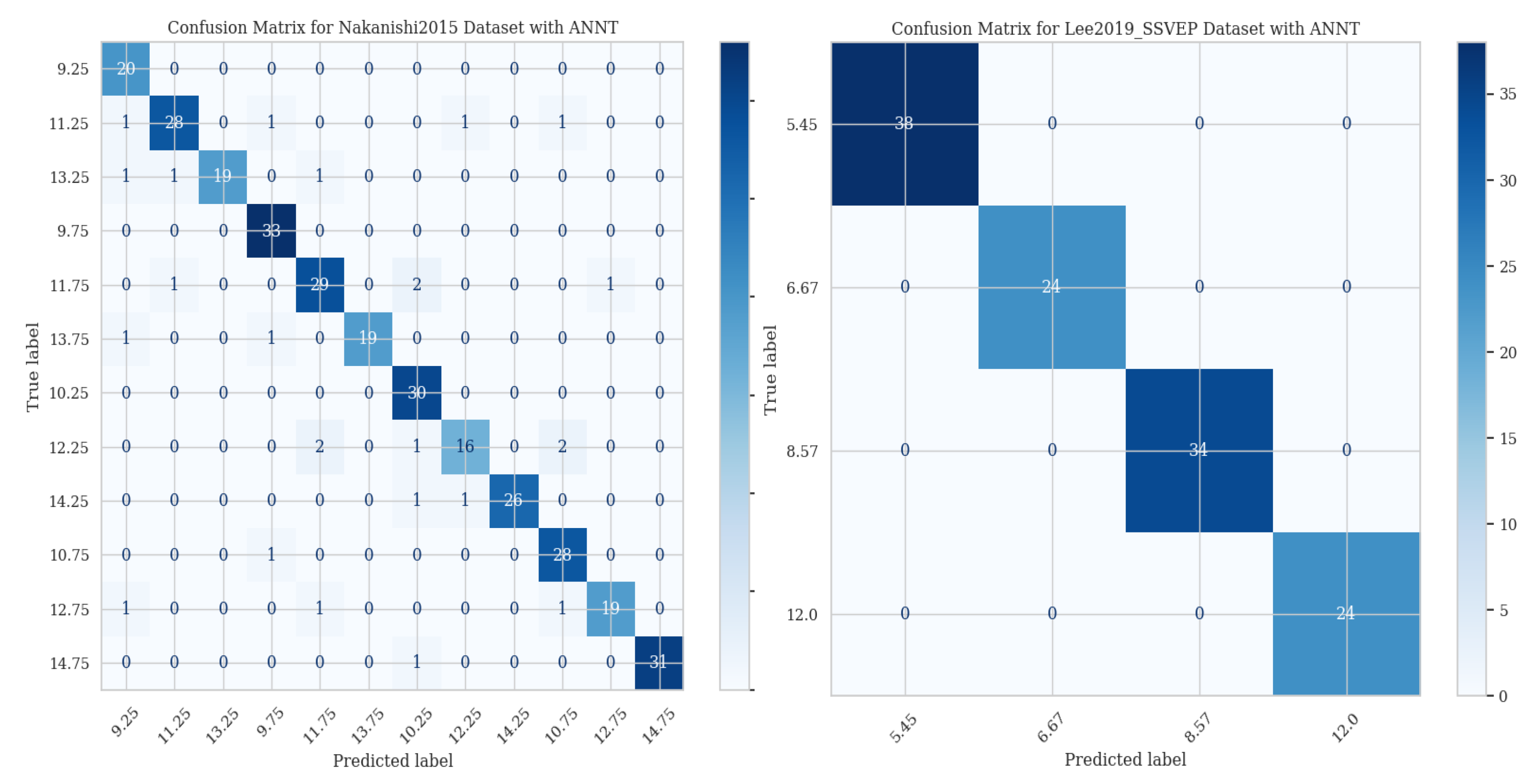

- Dense Layer: Finally, a Dense layer with a number of units equal to the number of classes (12 for Nakanishi2015 and 4 for Lee2019_SSVEP) and a softmax activation function is used for classification.

- Evaluation: The model’s robustness is tested across three scenarios: classification of clean data, classification of adversarially attacked data, and classification of attacked data using ANNT.

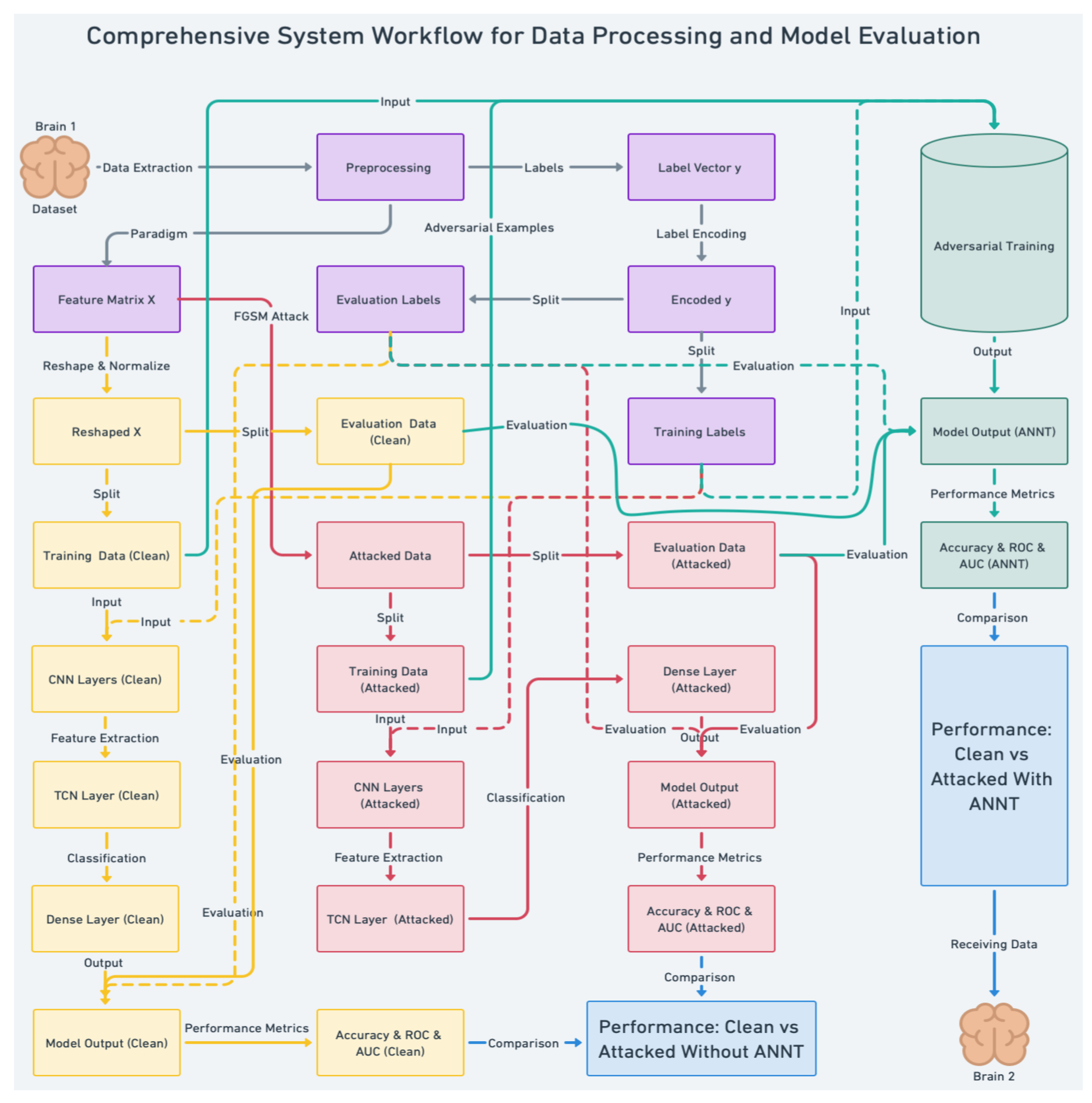

2.4. System Flow Process

- Data Extraction: EEG data is extracted from Brain 1, capturing the neural responses to visual stimuli flickering at specific frequencies.

- Preprocessing: The raw EEG data undergoes preprocessing steps, including normalization and filtering, to retain the relevant frequency components associated with SSVEP.

- Label Vector Creation: Labels corresponding to the SSVEP stimuli are created and encoded for model training.

-

Feature Extraction:

- –

- The preprocessed EEG data is split into training and evaluation sets.

- –

- The CNN layers extract spatial features from the clean and attacked data.

- –

- The TCN layers capture temporal dependencies in the EEG signals.

-

Adversarial Training:

- –

- Adversarial examples are generated using the FGSM to simulate potential attacks, a method chosen for its effectiveness in challenging the model’s resilience, thereby evaluating its robustness against potential threats.

- –

- The model is trained on clean and adversarially perturbed data using ANNT, enhancing its ability to recognize and resist adversarial patterns.

-

Classification and Model Output:

- –

- The Dense layer classifies the EEG signals into the respective classes based on the extracted features.

- –

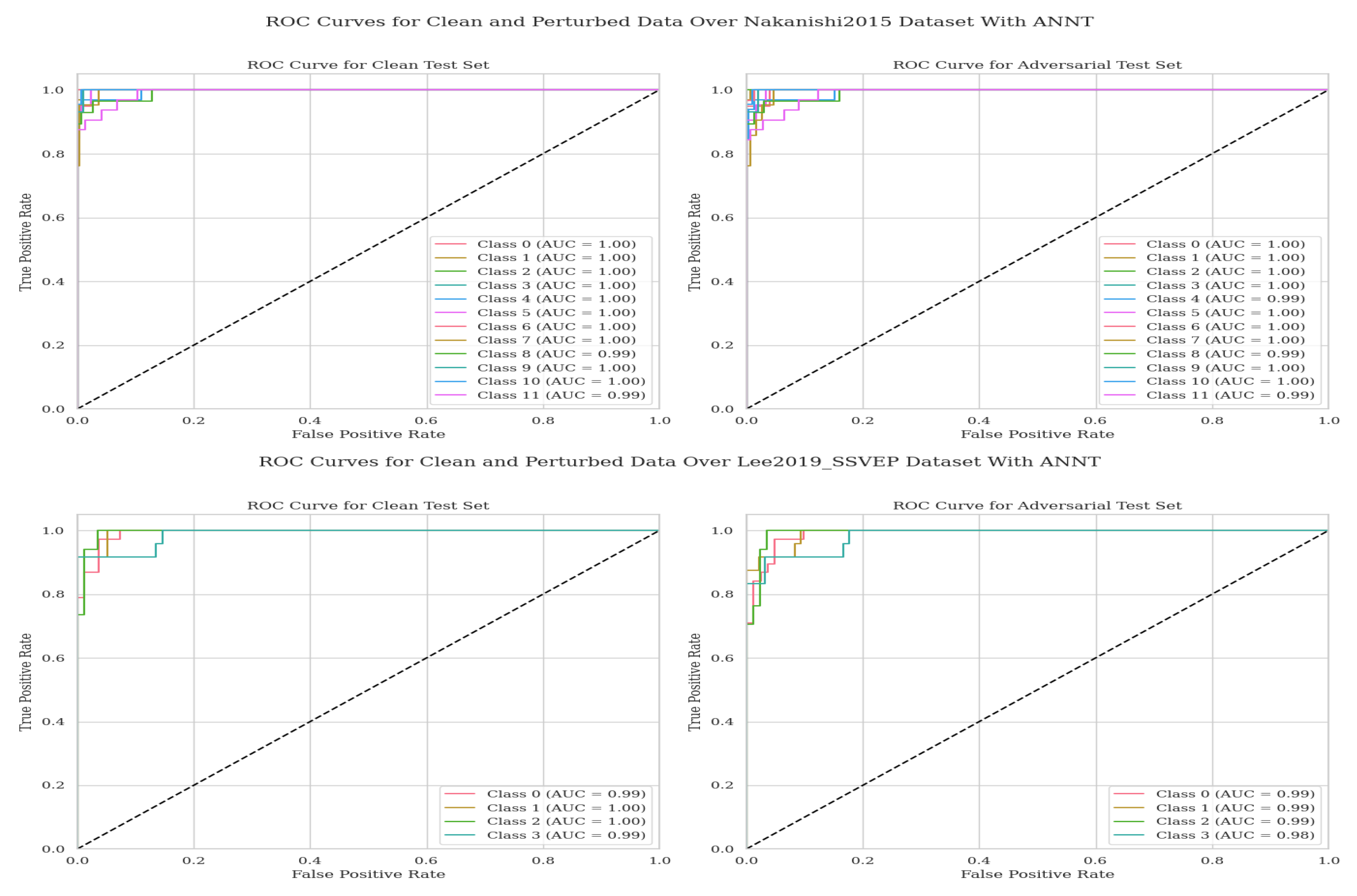

- The model’s performance is evaluated using accuracy and AUC under clean and attacked scenarios.

-

Comparison and Analysis:

- –

- The model’s performance is compared across different scenarios, with and without ANNT, to assess its robustness and security.

- –

- The results are analyzed to identify the optimal conditions under which ANNT enhances the security and robustness of SSVEP-based B2B-C systems.

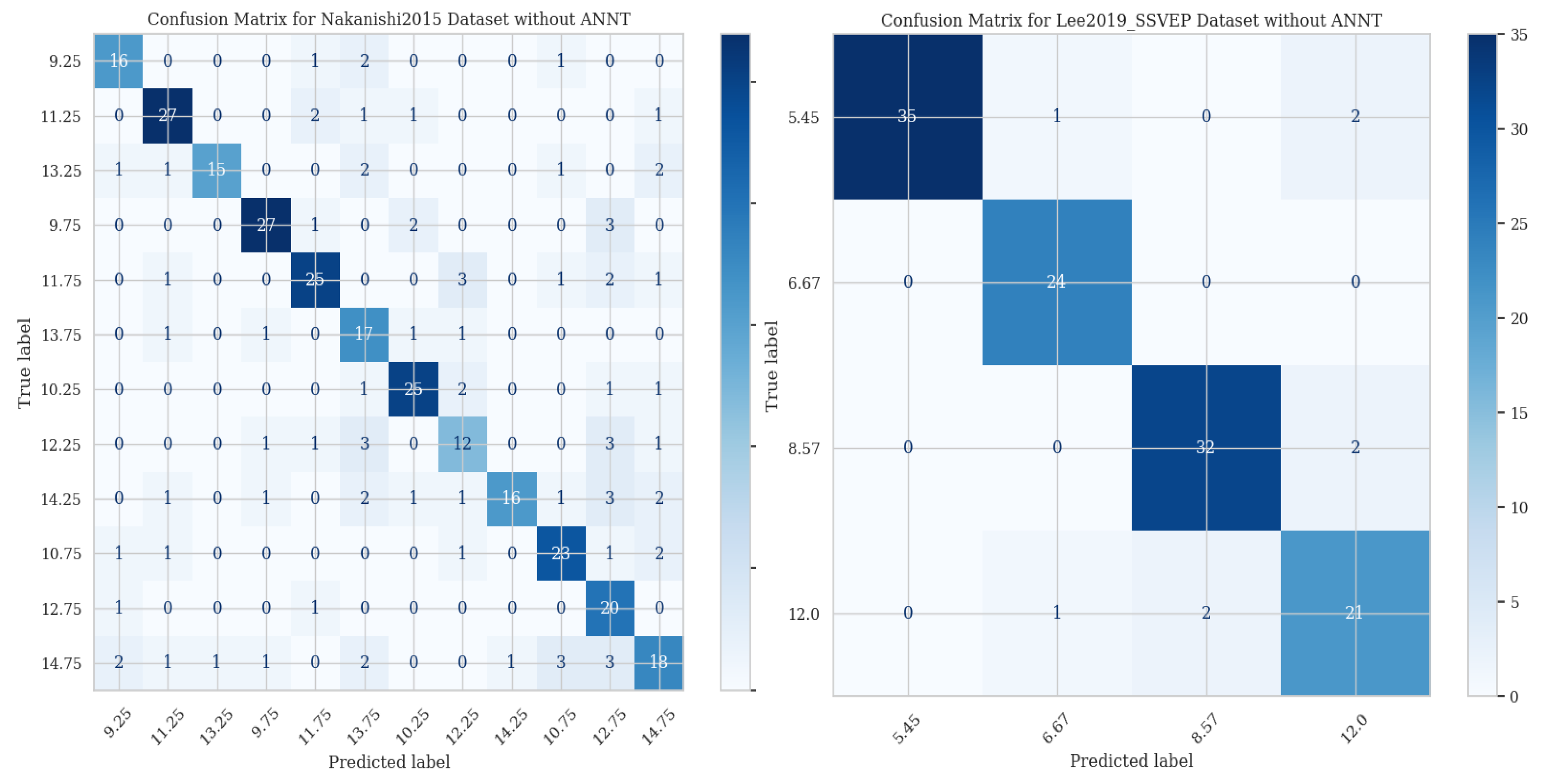

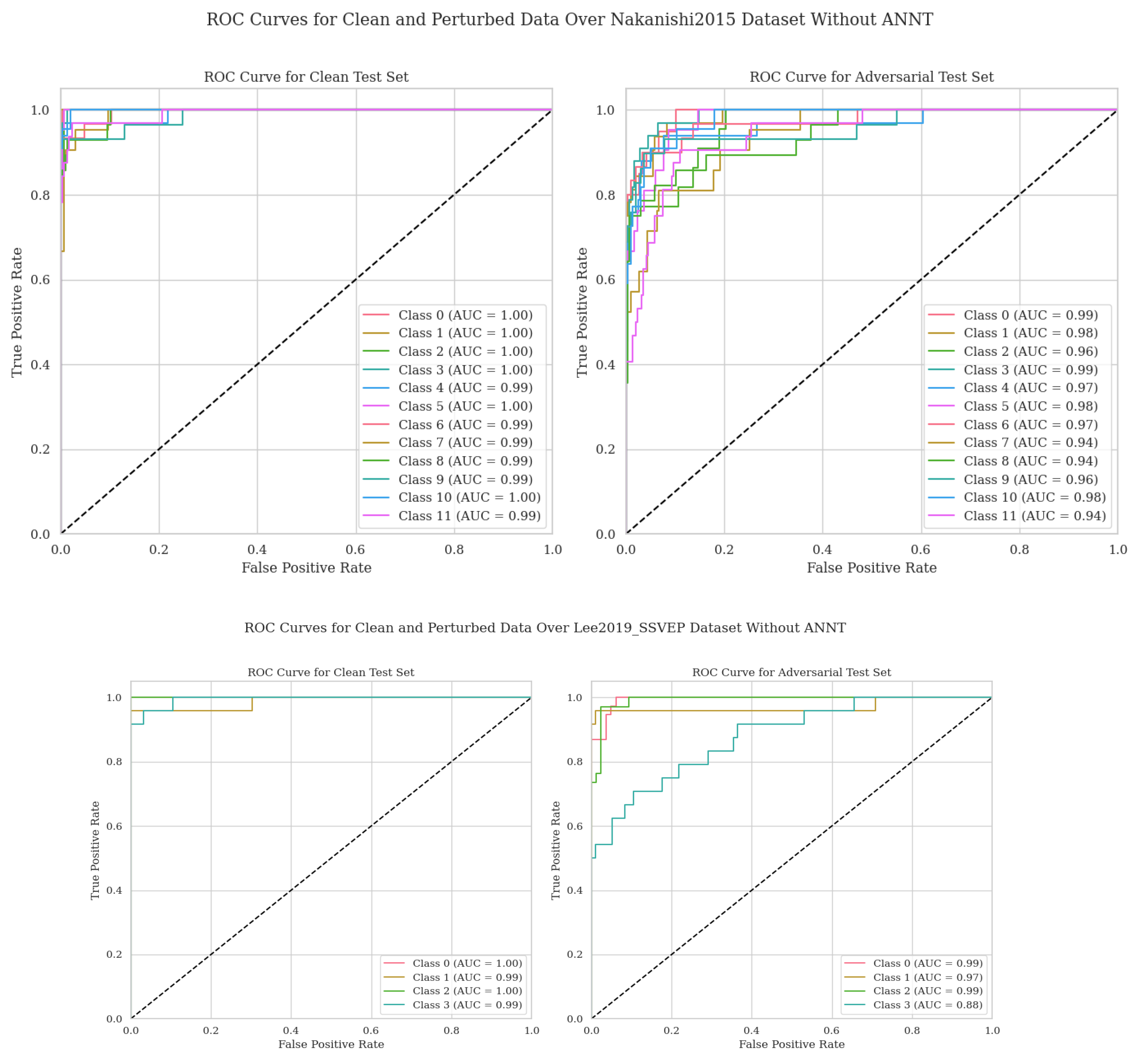

3. Results

4. Discussion

| Dataset | Condition | Class | AUC without ANNT | AUC with ANNT | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nakanishi2015 | Clean | 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 3 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 5 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.01 | ||

| 6 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 7 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.01 | ||

| 8 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.01 | ||

| 9 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.00 | ||

| 10 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.01 | ||

| 11 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 12 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.00 | ||

| Nakanishi2015 | Attacked | 1 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.01 |

| 2 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.02 | ||

| 3 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.04 | ||

| 4 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.01 | ||

| 5 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.02 | ||

| 6 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.02 | ||

| 7 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.03 | ||

| 8 | 0.94 | 1.00 | 0.06 | ||

| 9 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.05 | ||

| 10 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.04 | ||

| 11 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.02 | ||

| 12 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.05 | ||

| Lee2019_SSVEP | Clean | 1 | 1.00 | 0.99 | -0.01 |

| 2 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.01 | ||

| 3 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 4 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.00 | ||

| Lee2019_SSVEP | Attacked | 1 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.02 | ||

| 3 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.00 | ||

| 4 | 0.88 | 0.98 | 0.10 |

| Dataset | Condition | Accuracy without ANNT | Accuracy with ANNT |

| Nakanishi2015 | Attacked | 0.75 | 0.92 |

| Lee2019_SSVEP | Attacked | 0.93 | 1.00 |

| Metric | Nakanishi2015 Improvement | Lee2019_SSVEP Improvement |

| Average AUC Improvement (Clean) | 0.003 | 0.00 |

| Average AUC Improvement (Attacked) | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Accuracy Improvement | 0.17 | 0.07 |

| Metric | Overall Improvement |

| Average AUC Improvement (Clean) | 0.0015 |

| Average AUC Improvement (Attacked) | 0.03 |

| Accuracy Improvement | 0.12 |

4.1. Key Findings

- Effectiveness of ANNT: Our study reaffirms the effectiveness of ANNT in enhancing the robustness and security of B2B-C systems. Consistent with our previous findings, ANNT significantly improves accuracy and AUC, particularly under adversarial conditions. This indicates that ANNT is reliable for fortifying B2B-C systems against potential attacks.

-

Impact of Dataset Characteristics:

- –

- Subject and Channel Count: The Lee2019_SSVEP dataset, with its higher subject and channel count, demonstrates superior baseline performance and significant improvement with ANNT. This suggests that datasets with more diverse and extensive data can benefit greatly from adversarial training.

- –

- Number of Classes: The Nakanishi2015 dataset highlights the challenges of complex classification tasks with its larger number of classes. The substantial accuracy improvement with ANNT for this dataset underscores the method’s effectiveness in handling multi-class scenarios.

- –

- Sampling Rate and Data Quality: The higher sampling rate of the Lee2019_SSVEP dataset contributes to better baseline performance. However, ANNT’s ability to enhance performance in the lower-resolution Nakanishi2015 dataset indicates its robustness across varying data quality levels.

- –

- Trial Length and Number of Trials: The significant number of trials in the Lee2019_SSVEP dataset supports better learning and generalization. ANNT’s effectiveness in the Nakanishi2015 dataset with fewer trials suggests its potential in limited-data scenarios.

4.2. Comparison with Previous Work

4.3. Broader Impact and Implications

- Robustness and Security: The consistent improvements in robustness and security with ANNT across different datasets highlight its potential as a standard approach for enhancing B2B-C systems. This is crucial for security applications, such as medical and military communications.

- Dataset Design Considerations: Our findings suggest that when designing datasets for B2B-C systems, factors such as the number of classes, channels, sampling rate, and trial length should be carefully considered. These factors influence baseline performance and how adversarial training can improve system robustness.

-

Future Research Directions:

- –

- Exploring Other Adversarial Techniques: While ANNT has proven effective, exploring other adversarial training techniques could further enhance robustness and security.

- –

- Larger and More Diverse Datasets: Future research should focus on larger and more diverse datasets to validate these findings and understand the limitations of ANNT.

- –

- Real-World Applications: Implementing ANNT in real-world B2B-C systems will be crucial to understanding its practical implications and any challenges that may arise.

- –

- Normalization Limitations: The normalization process, while reducing variability and improving analysis performance, may lead to the loss of information regarding differences in EEG amplitude distribution on the scalp. Future research could explore advanced techniques to preserve this amplitude distribution information while achieving the desired standardization.

- –

- Exploring Additional Attacks: Future work should consider and apply other types of attacks, such as jamming and eavesdropping, to further test the robustness and security of the B2B-C systems. Investigating countermeasures against these attacks will provide a more comprehensive understanding of system vulnerabilities and defenses.

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANNT | Adversarial Neural Network Training |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| B2B-C | Brain-to-Brain Communication |

| BCI | Brain-Computer Interface |

| CAR | Common Average Reference |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| ERP | Event-Related Potentials |

| FGSM | Fast Gradient Sign Method |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SSVEP | Steady-State Visually Evoked Potentials |

| TCN | Temporal Convolutional Network |

| WS-AIEC | Weighted and Stacked Adaptive Integrated Ensemble Classifier |

References

- Grau, C., Ginhoux, R., Riera, A., Nguyen, T. L., Chauvat, H., Berg, M., & Amengual, J. L. (2014). Conscious Brain-to-Brain Communication in Humans Using Non-Invasive Technologies. PLOS ONE, 9(8), e105225. [CrossRef]

- Lebedev, M., Kunicki, C., Wang, J., & Nicolelis, M. A. (2013). A Brain-to-Brain Interface for Real-Time Sharing of Sensorimotor Information. Scientific Reports 2013, 3, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Hindley, N., Sanchez Avila, A., & Henstridge, C. (2023). Bringing synapses into focus: Recent advances in synaptic imaging and mass-spectrometry for studying synaptopathy. Frontiers in Synaptic Neuroscience, 15, 1130198. [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, M., Karwowski, W., Farahani, F. V., Fiok, K., Taiar, R., & Hancock, P. A. (2021). Neural Decoding of EEG Signals with Machine Learning: A Systematic Review. Brain Sciences, 11(11), 1525. [CrossRef]

- Dattola, S., Morabito, F. C., Mammone, N., & La Foresta, F. Findings about LORETA Applied to High-Density EEG—A Review. Electronics, 9(4), 660. [CrossRef]

- Fares, A., Zhong, S. & Jiang, J. EEG-based image classification via a region-level stacked bi-directional deep learning framework. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 19(Suppl 6), 268 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Walther, D., Viehweg, J., Haueisen, J. & Mäder, P. (2023). A systematic comparison of deep learning methods for EEG time series analysis. Frontiers in Neuroinformatics, 17:1067095. [CrossRef]

- Rong, J., Sun, R., Guo, Y., & He, B. (2023). Effects of EEG Electrode Numbers on Deep Learning-Based Source Imaging. In: Liu, F., Zhang, Y., Kuai, H., Stephen, E.P., Wang, H. (eds) Brain Informatics. BI 2023. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 13974. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Orban, M., Elsamanty, M., Guo, K., Zhang, S., & Yang, H. (2022). A Review of Brain Activity and EEG-Based Brain–Computer Interfaces for Rehabilitation Application. Bioengineering, 9(12), 768. [CrossRef]

- Müller-Putz, G. R., Scherer, R., Brauneis, C., & Pfurtscheller, G. (2005). Steady-state visual evoked potential (SSVEP)-based communication: impact of harmonic frequency components. Journal of Neural Engineering, 2(4), 123. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Xu, P., Liu, T., Hu, J., Zhang, R., & Yao, D. (2012). Multiple Frequencies Sequential Coding for SSVEP-Based Brain-Computer Interface. PLOS ONE, 7(3), e29519. [CrossRef]

- Diez, P. F., Mut, V. A., Avila Perona, E. M. et al. (2011). Asynchronous BCI control using high-frequency SSVEP. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation, 8, 39. [CrossRef]

- Sergio, L. B., et al. (2021). Security in Brain-Computer Interfaces: State of the Art, Opportunities, and Future Challenges. ACM Computing Surveys, 54(1), Article 11. [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S., Kim, H., Filandrianos, E., Taghados, S. J., & Park, S. (2013). Non-Invasive Brain-to-Brain Interface (BBI): Establishing Functional Links between Two Brains. PLOS ONE, 8(4), e60410. [CrossRef]

- Dongrui, W., et al. (2023). Adversarial attacks and defenses in physiological computing: a systematic review. National Science Open, 2(1). [CrossRef]

- Adesina, D., Hsieh, C.-C., Sagduyu, Y. E., & Qian, L. (2023). Adversarial Machine Learning in Wireless Communications Using RF Data: A Review. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, 25(1), 77-100.

- Donchin, E., Spencer, K. M., & Wijesinghe, R. (2000). The mental prosthesis: assessing the speed of a P300-based brain-computer interface. IEEE Transactions on Rehabilitation Engineering, 8(2), 174-179. [CrossRef]

- Wolpaw, J. R., & McFarland, D. J. (2004). Control of a two-dimensional movement signal by a noninvasive brain-computer interface in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101(51), 17849-17854. [CrossRef]

- Buzsáki, G. (2006). Rhythms of the Brain. Oxford University Press.

- Ahmadi, H., & Mesin, L. (2024). Enhancing Motor Imagery Electroencephalography Classification with a Correlation-Optimized Weighted Stacking Ensemble Model. Electronics, 13(6), 1033. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, H., & Mesin, L. (2024). Enhancing MI EEG Signal Classification with a Novel Weighted and Stacked Adaptive Integrated Ensemble Model: A Multi-Dataset Approach, IEEE Access, submitted, 2024.

- Rao, R. P., Stocco, A., Bryan, M., Sarma, D., Youngquist, T. M., Wu, J., & Prat, C. S. (2014). A Direct Brain-to-Brain Interface in Humans. PLOS ONE, 9(11), e111332. [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, S., Paul, V., Menon, V. G., Jacob, S., & Vinod, P. (2020). Secure Brain-to-Brain Communication With Edge Computing for Assisting Post-Stroke Paralyzed Patients. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 7(4), 2531-2538. [CrossRef]

- Ajmeria, R., Sharma, N., Kalyani, N., Iyer, B., Kamal, M. K., & Pathan, M. (2023). A Critical Survey of EEG-Based BCI Systems for Applications in Industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, 25(1), 184-212. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, H., Kuhestani, A., & Mesin, L. (2024). Adversarial Neural Network Training for Secure and Robust Brain-to-Brain Communication. IEEE Access, 12, 39450-39469.

- Nakanishi, M., Wang, Y., Wang, T., & Jung, P. (2015). A Comparison Study of Canonical Correlation Analysis Based Methods for Detecting Steady-State Visual Evoked Potentials. PLOS ONE, 10(10), e0140703. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M., Kwon, O., Kim, Y., Kim, H., Lee, Y., Williamson, J., Fazli, S., & Lee, S. (2019). EEG dataset and OpenBMI toolbox for three BCI paradigms: An investigation into BCI illiteracy. GigaScience, 8(5). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).