1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of computer technology, deep learning has found extensive applications in various domains, particularly excelling in tasks like image classification. However, their high accuracy and robustness can be compromised by adversaries who deliberately manipulate the input data to deceive the model. Such attacks could have severe implications in real-world applications, such as autonomous driving and security systems [

1]. Alternatively, they can deceive security systems employing Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) for face recognition [

2]. Understanding the vulnerabilities of DNNs to adversarial attacks and developing effective defense mechanisms has become a crucial research area in the field of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and computer security. Adversarial samples are constructed by introducing minor perturbations to the original data, which trick the classifier into making incorrect classifications. By investigating the generation algorithms of adversarial examples, research can advance defenses against such examples, consequently bolstering the security of deep neural network models.

Adversarial sample generation algorithms play a crucial role in understanding the limitations of neural networks and enhancing network security. A growing number of startups are involved in a diverse range of computer vision tasks. DeepFool is an algorithm proposed by Moosavi-Dezfooli et al. [

3] that iteratively determines the minimum perturbation needed to move a given input image into a misclassified region of the feature space. Although the DeepFool generation process typically requires multiple iterations to achieve high attack success rates, conducting numerous iterations to generate adversarial samples substantially escalates computational complexity. This necessitates greater computational resources, particularly in the present era characterized by rapid growth in big data and large-scale models. For startups, this presents a significant challenge in improving model security. Therefore, a pressing need exists for a rapid and efficient method to seek adversarial perturbations, to bolster adversarial training techniques, fortify model security, and investigate model robustness against adversarial perturbations. Within the domain of adversarial attacks, methods for generating adversarial samples through single-step iteration remain relatively scarce. In this study, we have modified the iteration direction of the DeepFool algorithm. By leveraging gradient differences to identify the direction of samples closest to the decision boundary and searching for adversarial samples along this direction, we can accelerate the generation speed of adversarial samples.

While the DeepFool algorithm is effective in identifying minimal perturbations for misclassifying data, a more expedited methodology is imperative. our main contributions are as follows:

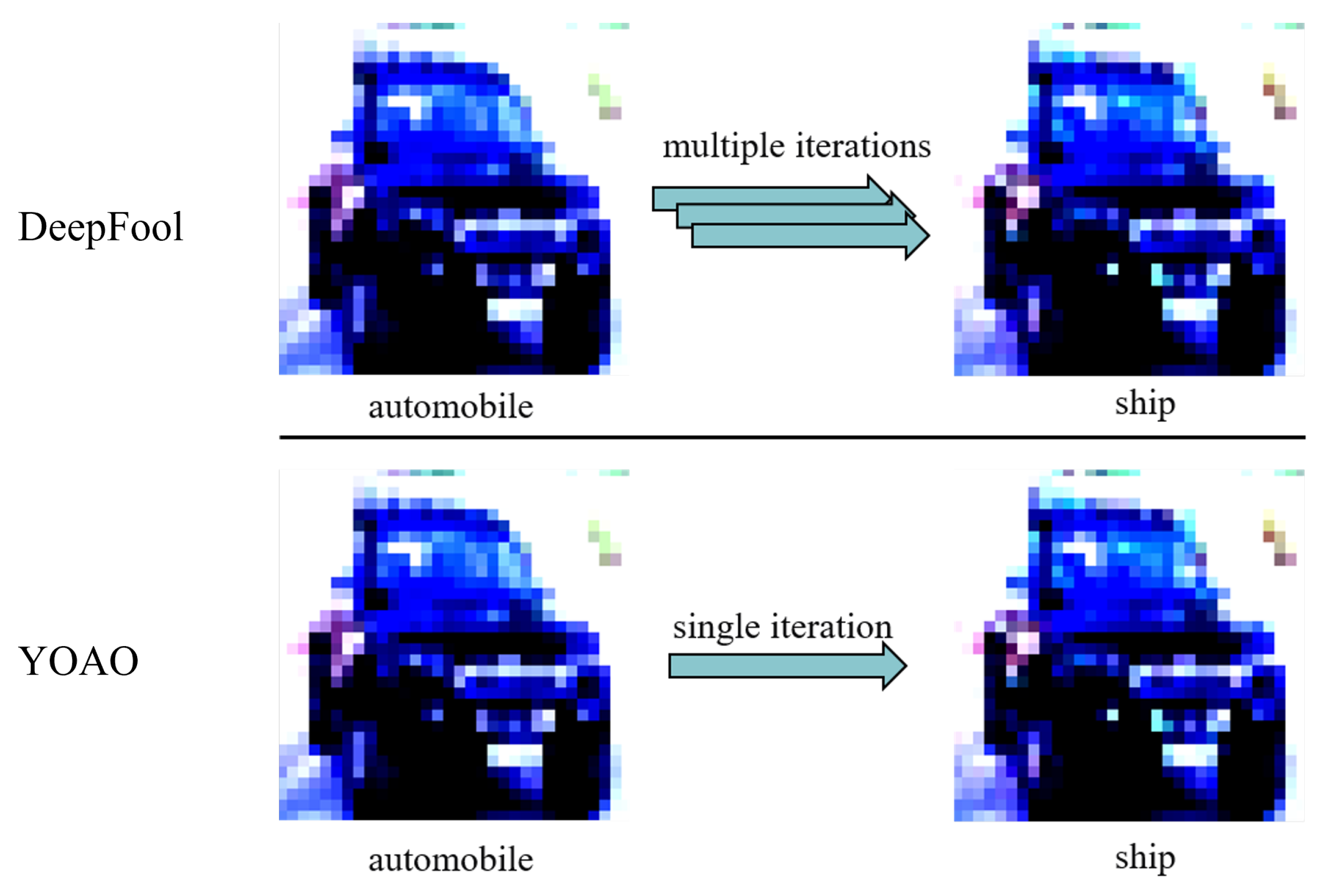

As shown in

Figure 1, We have enhanced the DeepFool algorithm by computed the gradient information of each class in input samples and comparing these gradient differences with the true class that generates adversarial samples in a single iteration, achieved a significant 68% increase in the success rate of adversarial sample generation compared to the original algorithm.

We have demonstrated through experiments that the algorithm has a simpler time complexity than the DeepFool algorithm. By conducted comparative experiments with other related research, we have shown that the YOAO algorithm exhibits superior attack efficiency and is more effective at having misled various deep neural networks into misclassification.

Figure 1.

This Figure illustrates the disparity between the DeepFool algorithm and the algorithm introduced in this study. Initially, a sample is classified as belonging to the "automobile" class by the classifier. Following the creation of adversarial samples using both the DeepFool and YOAO algorithms, the resulting adversarial sample is misclassified as belonging to the "ship" class by the classifier. The upper subfigure illustrates the necessity for multiple iterations by the DeepFool algorithm to progressively approach the decision boundary and generate adversarial samples. In contrast, the lower subfigure presents the YOAO algorithm introduced in this study, which requires only a single iteration to effectively generate an adversarial sample. Clearly, the YOAO algorithm notably enhances computational efficiency and practical applicability.

Figure 1.

This Figure illustrates the disparity between the DeepFool algorithm and the algorithm introduced in this study. Initially, a sample is classified as belonging to the "automobile" class by the classifier. Following the creation of adversarial samples using both the DeepFool and YOAO algorithms, the resulting adversarial sample is misclassified as belonging to the "ship" class by the classifier. The upper subfigure illustrates the necessity for multiple iterations by the DeepFool algorithm to progressively approach the decision boundary and generate adversarial samples. In contrast, the lower subfigure presents the YOAO algorithm introduced in this study, which requires only a single iteration to effectively generate an adversarial sample. Clearly, the YOAO algorithm notably enhances computational efficiency and practical applicability.

2. Related Works

2.1. Adversarial Attacks

Adversarial attacks can be categorized into distinct types based on various criteria. Segregated by the understanding of the model’s internal architecture, they are delineated as white-box attacks and black-box attacks [

4]. A white-box attack constitutes an adversarial attack algorithm that requires understanding the model’s internal structure and gradients to generate adversarial samples. Conversely, a black-box attack operates without needing knowledge of the internal structure and gradient information of the targeted model. Further classification of adversarial attacks is based on whether the attack algorithm can misclassify the model into a specific class, leading to the distinction between targeted attacks and non-targeted attacks. Targeted attacks aim to misclassify input data into a specific target class by following certain constraints. In contrast, non-targeted attacks focus solely on potentially misclassifying input data without aiming for a specific target class.

The defense of adversarial samples has driven the evolution of adversarial sample attacks. Likewise, ensuring the robust and security of deep learning models requires a more powerful adversarial attack algorithm. A significant breakthrough has been achieved in uncovering vulnerabilities in multiple state-of-the-art Deep Neural Networks (DNNs), signifying notable advancements in the domain of adversarial machine learning. Despite being trained meticulously, DNNs exhibit distinct blind spots and are vulnerable to adversarial attacks. Adversaries exploit these weaknesses to generate adversarial examples, capable of misleading machine learning models through slight alterations to the input data distribution. This intrinsic feature of DNNs is utilized in various adversarial attack algorithms to produce adversarial examples.

The Fast Gradient Sign Method (FGSM), proposed by Goodfellow et al. [

5], is based on the concept of gradients and can rapidly and effectively generate adversarial examples. However, this method requires the manual selection of a perturbation coefficient, leading to the addition of relatively large perturbations. Iterative Fast Gradient Sign Method (I-FGSM), proposed by Kurakin et al. [

6], enhances FGSM by iteratively applying perturbations, typically resulting in smaller perturbations and stronger white-box attack capabilities compared to FGSM. However, this approach demands more computational resources and time to achieve the iterations. Trans-IFFT-FGSM (Transformer Inverse Finite Fourier Transform Fast Gradient Sign Method) , presented in Naseem [

7], incorporates multiple modules and retains input noise information, enhancing the attack success rate (ASR) with smaller perturbations, but at the cost of increased algorithm complexity and computational expense.

DeepFool, proposed by Moosavi-Dezfooli et al. [

3], aims to introduce the minimal perturbation necessary to generate adversarial examples. As a white-box untargeted attack, the fundamental concept of DeepFool involves perturbing the input image in a manner that guides it across the separating boundary. While this algorithm can generate adversarial examples with minimal perturbations, its high computational cost arises from the need for multiple iterations. Building upon the concept of DeepFool, Moosavi-Dezfooli et al. [

8] proposed a universal perturbation method that calculates the sum of vectors representing the distances from multiple original inputs to the decision boundary to generate a universal perturbation. This algorithm successfully perturbs a majority of images in the dataset, demonstrating a certain level of generalization. By iteratively finding the minimal perturbation and summing the found minimal perturbations, the final universal perturbation is obtained. To address the shortcomings of the DeepFool algorithm, Gajjar et al. [

9] proposed a targeted version called Targeted DeepFool, which can misdirect misclassification towards a specific target class, realizing a targeted attack approach for DeepFool. Labib et al. [

10] introduced an enhanced version of Targeted DeepFool, which increases the ability to misclassify specific classes and introduces a minimum confidence score requirement hyperparameter to enhance flexibility, albeit at the cost of increased algorithm complexity. In the latest research on adversarial sample transferability, Ling et al. [

11] proposed a simple channel switching method called CS-MI-FGSM, which obtains variants of the input image and mixes them during momentum updating to improve the transferability of adversarial samples.

In our study comparing the strengths and limitations of existing algorithms, we propose the YOAO (You Only Attack Once) algorithm, which not only rapidly generates adversarial examples but also ensures their potent attack capability. This algorithm is a gradient-based, fast DeepFool method that calculates the maximum gradient disparity across different classes to more swiftly identify the minimal perturbation. By generating adversarial samples in a single-step iteration, it addresses the slow attack speed issue of the original DeepFool algorithm, significantly enhancing the algorithm’s attack efficiency.

2.2. Adversarial Defense

Adversarial sample defense refers to the measures taken to protect Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) from adversarial attacks, which are maliciously crafted input samples aimed at misleading the neural network’s output [

12]. The significance of adversarial sample defense lies in ensuring that DNNs can maintain robustness and reliability when faced with adversarial attacks, thereby ensuring their correct operation and resilience against malicious manipulations in practical applications [

13]. By implementing effective adversarial sample defense mechanisms, the security of deep learning systems can be enhanced.

Adversarial training is the most direct and commonly used defense technique to enhance the adversarial robustness of models. The fundamental principle involves augmenting training data by introducing additional adversarial samples. Initially proposed by Szegedy et al. [

14], this concept aimed at training neural networks with robustness for classification tasks. Adversarial training aids in reducing the loss curvature in both input space and model parameter space, thereby narrowing the adversarial robustness gap between train and test data. These findings have spurred the development of a range of regularization techniques that enhance adversarial defense capabilities by explicitly addressing the curvature of the loss function or other geometric features [

13]. Many regularization techniques can reduce computational complexity without increasing the training set, such as Local Linear Regularization (LLR) [

15]and Input Gradient Regularization (IGR) [

16].

In addition to adversarial training, there exist alternative approaches to improve model’s adversarial robustness, such as Topology-Aligned Adversarial Training (TAAT) [

17], Feature-Decoupled Networks (FDNet), and Attention-Guided Reconstruction Loss (AIAF-Defense) [

18], which aim to smooth out the loss landscape in the model parameter space. Other defense strategies include feature denoising [

19], domain adaptation [

20], and ensemble defenses [

13].

3. Method

3.1. Introduction to the Primitive Method

3.1.1. Mathematical Representation of Adversarial Examples

With the goal of carefully crafting extremely small perturbations to be applied to the original samples, thereby creating adversarial examples. The characteristic of these perturbations is their tiny magnitude, such that they are nearly imperceptible to human vision, yet for machine learning models, they lead to inconsistent classification results compared to the original class. The task of generating adversarial examples is as follows:

Where represents the class predicted by the classifier for the original image sample, represents the class predicted by the classifier for the adversarial sample with added perturbation, and represents a predefined very small parameter.

3.1.2. The Relationship Between Adversarial Examples and Decision Boundaries

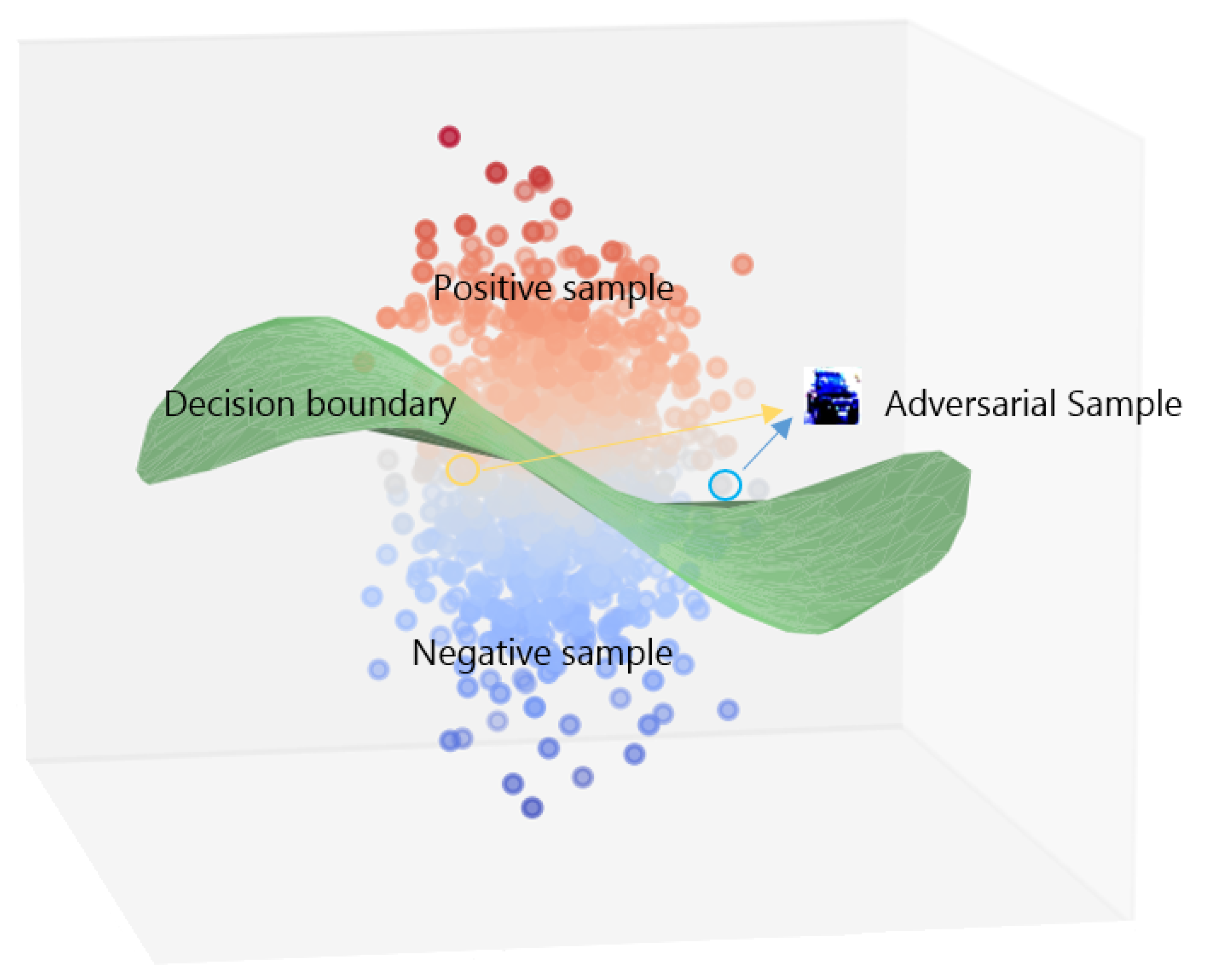

In the training process of neural networks, original low-dimensional data such as hand-written digits or images from natural scenes undergo multi-layered, non-linear transformations. During this process, the data gradually maps from a low-dimensional space to a high-dimensional feature space, forming feature maps. These feature maps not only contain basic information from the original images, such as edges, textures, and shapes, but also integrate complex patterns learned by the neural network during the training process and the inherent relationships between classes, such as abstract concepts and different ways of combining features. In the high-dimensional feature space, the neural network gradually learns one or multiple decision boundaries by optimizing the loss function. As shown in

Figure 2, these decision boundaries partition the feature space into different regions, with each region corresponding to a class. The shapes and positions of these boundaries depend on the distribution of the training data, the architecture of the network, and the choice of optimization algorithm. By continuously adjusting network parameters, the neural network can find the optimal decision boundaries, thus achieving accurate differentiation between different classes.

3.1.3. Introduction to the DeepFool Algorithm

Moosavi-Dezfooli et al. [

3] proposed a sophisticated adversarial attack technique designed to introduce imperceptible small perturbations to benign inputs. Based on the concept of hyperplane-based classification, it iteratively linearizes the classifier to generate minimal perturbations sufficient to alter the classification label. Moosavi-Dezfooli et al. systematically investigate the minimal perturbations required to traverse the decision boundary of the target classifier. For binary classification problems, it identifies the nearest decision boundary and computes the minimal perturbation from the current point to that boundary to determine the adversarial sample. In the case of multiclass classification problems, the issue is decomposed into multiple binary classification problems, with the minimum perturbation calculated for each class individually.

In order to extend the applicability of this approach to nonlinear classifiers, DeepFool employs an iterative strategy that approximates the boundary of the initial correct class label associated with the point of interest. This iterative process draws inspiration from Newton’s iterative algorithm, enhancing the algorithm’s capacity to navigate the complex decision boundaries inherent in nonlinear classification scenarios.

3.2. Algorithm Improvement

3.2.1. Search for the Sample Point Closest to the Decision Boundary

The core idea of the DeepFool algorithm is to find the adversarial examples that are closest to the classification boundary. In this work, the proposed algorithmic improvements to the DeepFool algorithm to enhance its efficiency in finding adversarial examples and constructing effective universal perturbations.

We have proposed improvements to the iterative process for finding the sample point closest to the decision boundary. In each iteration step, we calculate the gradient information of the input sample with respect to each class, quantifying the sensitivity of each class to small changes in the input sample. We then compare the gradient differences between different classes to identify the largest one. These large gradient differences typically indicate that the decision boundary for these classes is more sensitive to the input sample. Therefore, searching along the direction of the class with the largest gradient difference can efficiently find the sample point that has a significant impact on the classification decision.

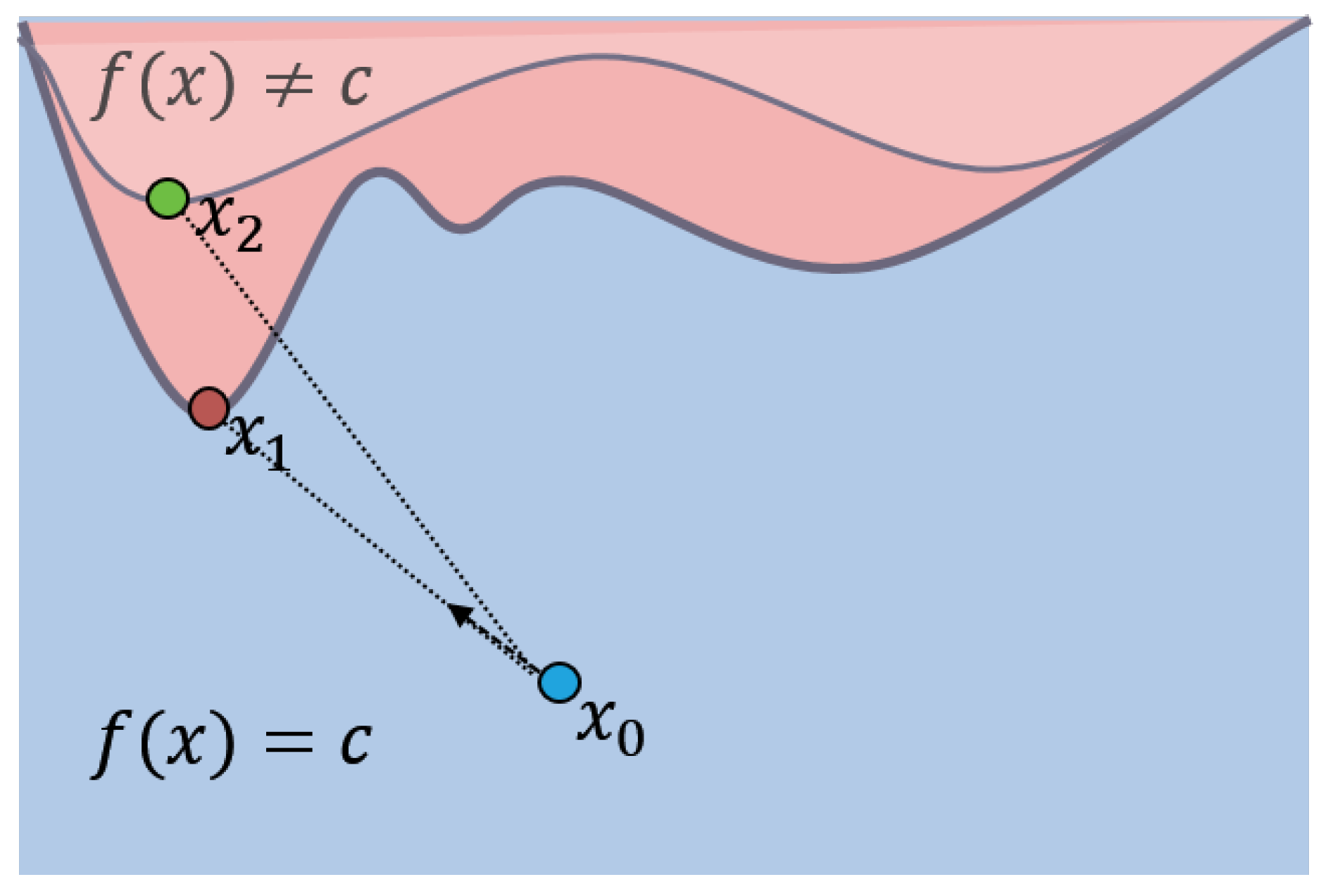

Figure 3 illustrates the algorithmic process, we take a three-class classification task as an example. We calculate the gradient differences between other classes and the original sample class, quantifying the sensitivity of each class to small changes in the input sample. Specifically, we determine the distances of the sample point

from the class regions where sample points

and

are located. This allows us to identify the point

that has the greatest discrepancy from the current image class. Subsequently, by computing in the direction from the original sample point

towards

, we can rapidly and effectively generate adversarial samples.

We have improved the process of finding adversarial samples that are closest to the classification boundary in the DeepFool algorithm. In this work, we utilized gradient information by computing the gradients of the input sample with respect to each class, thereby quantifying the sensitivity of each class to small perturbations in the input sample. This information enables the identification of the class most sensitive to variations in the input samples. By comparing the gradient differences among different classes, we can more effectively search for and locate sample points that significantly impact the classification decision, thereby finding points closest to the decision boundary. Having identified sample points closest to the decision boundary, we employ a minimal number of iterations (even potentially just one iteration) to generate adversarial samples, a method referred to as "You Only Attack Once" (YOAO). The aim of this approach is to enhance the efficiency of finding effective adversarial samples while reducing the number of iterations required.

The gradient difference between classes can be expressed as follows:

Where x represents the original image, represents the current class, c represents the original class, and represents the gradient information of input x with respect to the current class .

The perturbation direction is computed using the following formula:

Where

represents the difference in the gradient between the current class

and the original class

c for input

x, and

denotes its norm.

The formula for determining the direction of perturbation in the adversarial optimization process is as follows:

The variable signifies the perturbation at the the i-th iteration, while represents the perturbation at the -th iteration.

We can restate the optimization problem as follows:

where represents the Euclidean norm (L2 norm) of the perturbation r, which indicates the magnitude of the perturbation. is a constraint that ensures the perturbed sample has a different classification result from the original sample. is another constraint that ensures the magnitude of the perturbation r is within a pre-defined threshold , which defines the "smallness" of the perturbation. represents the difference between the gradients of the original class c and the current class . is a scalar that controls the step size or magnitude of the perturbation. The sign function applied to , denoted as , ensures that the direction of perturbation is aligned with the gradient difference direction.

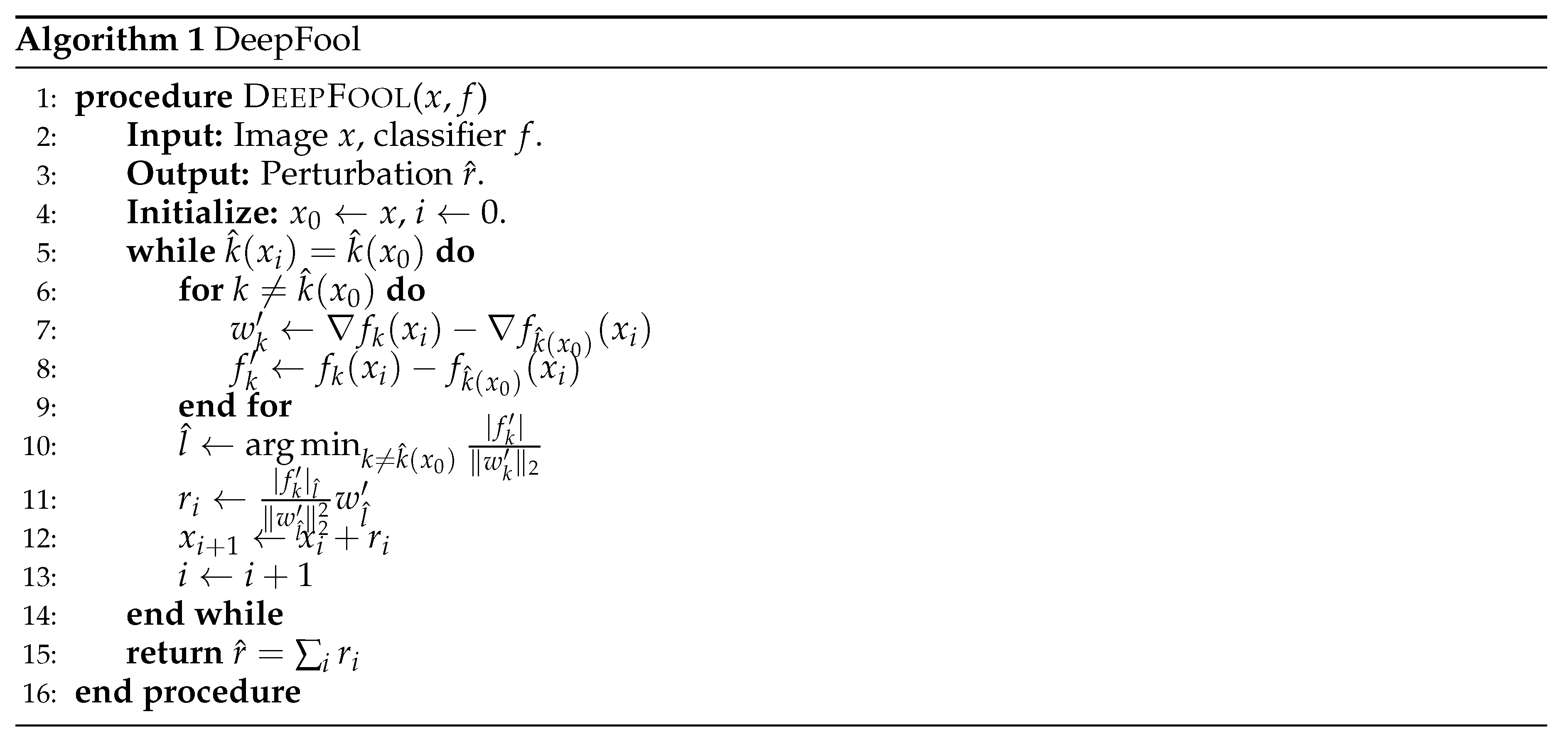

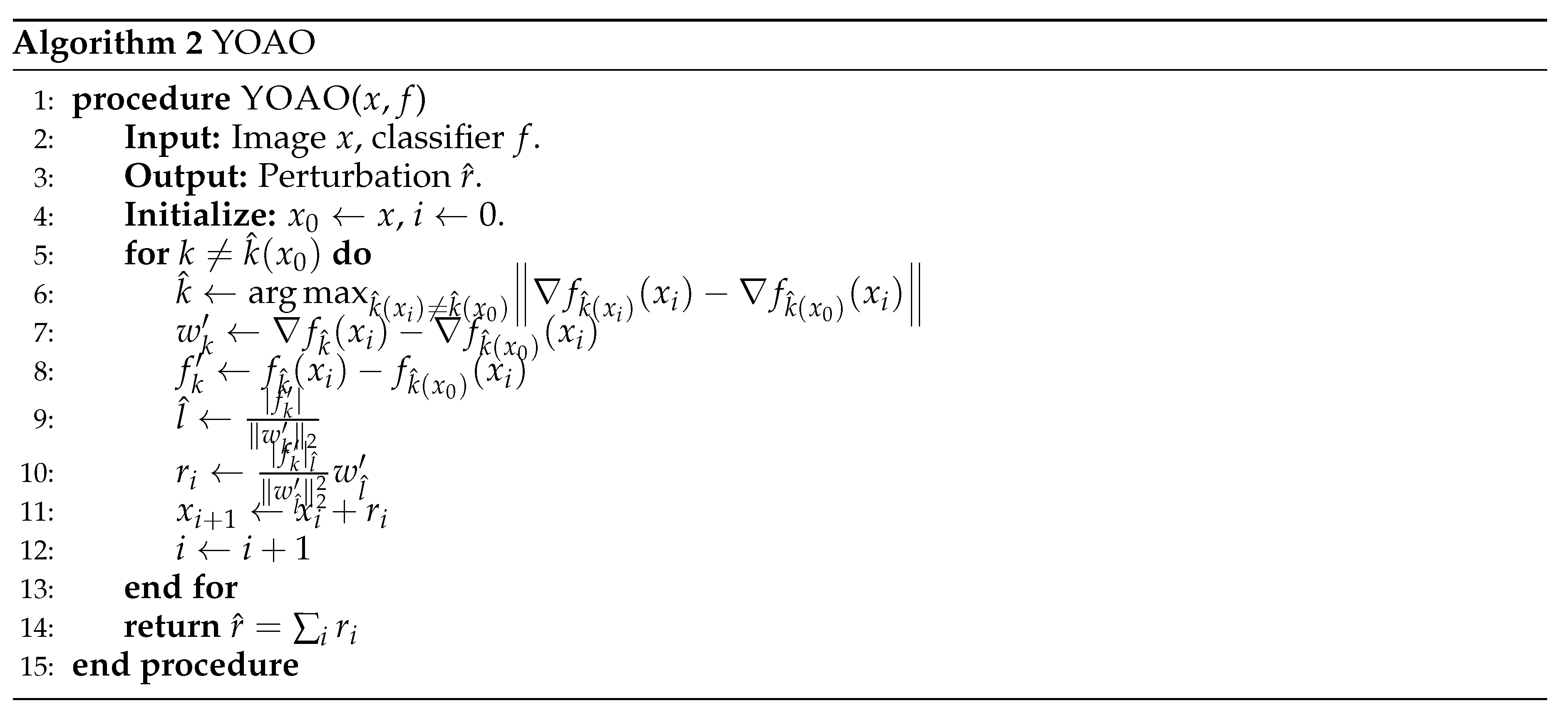

As shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, by introducing a single-step iterative generation scheme, we have successfully eliminated the cumbersome loop structure in the algorithm. Specifically, we have streamlined the loop condition in the line 5 and the for loop in the line 6 of the original DeepFool algorithm, no longer tediously calculating gradient information for the top

n non-target classes with the highest probabilities. Instead, we directly compute gradients for the class that exhibits the maximum gradient difference from the original class, thereby significantly reducing the time complexity. This step is crucial as it provides us with the most sensitive class information regarding the input sample. Subsequently, we utilize the gradient information

w and confidence information

f of this class to perform iterative calculations. This process not only enhances the efficiency of the algorithm but also ensures that we can accurately pinpoint the sample points that have the most significant impact on classification decisions.

This enhancement has endowed the proposed algorithm with the ability to rapidly and efficiently obtain adversarial samples, even when limiting the maximum number of iterations to 1.

Figure 4.

DeepFool Algorithm

Figure 4.

DeepFool Algorithm

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets

In the context of classification tasks, we employ the validation images from the ILSVRC2012 [

21], CIFAR-10 [

22], and MNIST [

23] datasets for our experiments. As target classifiers, we utilize pretrained ResNet18, VGG16 models.

ILSVRC2012 [21]: The dataset comprises 50,000 images spanning a thousand distinct classes. Widely recognized as a benchmark dataset in the field of computer vision, it has been instrumental in driving the progress of deep learning models. With its extensive size and diversity, the dataset serves as a comprehensive depiction of real-world visual data.

CIFAR-10 [22]:The CIFAR-10 dataset comprises 60,000 color images, each with a resolution of 32×32 pixels distributed across 10 distinct classes. Specifically, the dataset is partitioned into 50,000 images designated for training purposes and 10,000 images reserved for testing.

MNIST [23]:The MNIST dataset is a well-known dataset in the field of machine learning and computer vision. It consists of a large collection of handwritten digits (0 to 9) that are commonly used for training and testing machine learning models, particularly for image classification tasks. Each image in the MNIST dataset is a grayscale image with a resolution of 28x28 pixels.

4.2. Experimental Settings

We conduct experiments on the experimental settings to evaluate the classifiers against this attack. The experimental configurations includes an Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 6148 CPU @ 2.40GHz processor, an NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPU, and 16 GB of RAM. PyTorch 2.0.1 and Torchmetrics 0.15.2 libraries are installed on these experimental settings systems, with Python version 3.6 being utilized.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

The Success Rate of Adversarial Attacks:

Where represents the success rate of adversarial attacks on the classifier f, and N represents all the image samples used for testing, n represents the number of samples that, generated by the adversarial attack algorithm, successfully induce misclassification by the classifier.

Perturbation:The magnitude of perturbations added to an image, known as "perturbation", quantifies the level of changes required to deceive a classifier. We calculate the difference between the perturbed image and the original image, and then take the L2 norm to quantify the amount of change in the image.

Steps:The number of iterations needed to perturb an image is recorded. This metric indicates the average number of iterations required to achieve a successful misclassification.

Time:This metric is used to denote the computational time needed to execute an attack against a single image.

4.4. Experimental Results

4.4.1. Experimental Comparison with Classical Algorithms

As shown in

Table 1, we conducted a comparative analysis of various adversarial attack algorithms to assess their efficacy in classification tasks. The algorithms under consideration include PGD (Projected Gradient Descent) [

24], FGSM (Fast Gradient Sign Method) [

5], BIM (Basic Iterative Method) [

25], FFGSM (Fast Fourier Gradient Sign Method) [

26], APGD (Adaptive Projected Gradient Descent) [

27], SparseFool [

28], OnePixel [

29], Pixel [

30], PIFGSMPP (Patch-based Iterative Fast Gradient Sign Method with Patch Prior) [

31], and DeepFool [

3]. These algorithms encompass a spectrum of adversarial attack strategies, ranging from gradient-based methods to iterative approaches, as well as techniques leveraging image patches and sparsity. The selection of these algorithms is justified by their distinct attack mechanisms and their significant impact within the academic community, allowing us to challenge and evaluate the robustness of classification models from multiple perspectives. Through these comparative experiments, we aim to gain a comprehensive understanding of the effectiveness of different attack strategies and to provide valuable insights for enhancing model robustness.

We trained a classifier with an accuracy rate of 60% on the CIFAR dataset. It can be observed that the performance of various adversarial attack algorithms is high. Our YOAO algorithm ranked second, surpassing the DeepFool algorithm, and was only next to the PIFGSMPP algorithm. On the other hand, we trained a classifier on the MNIST dataset to achieve an accuracy rate of 99%. Interestingly, when the classifier accuracy is high, the success rate of adversarial attack algorithms significantly decreases. However, both the proposed algorithm and the Pixel algorithm maintained high attack success rates on high-accuracy classifiers. Compared to the Pixel algorithm, our method generates each adversarial sample image in just 0.091 seconds, making it 7.9 times faster. This demonstrates significant progress in both efficiency and attack performance of the proposed algorithm.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of adversarial attack algorithms on classifiers

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of adversarial attack algorithms on classifiers

| Algorithms |

Datasets |

Success rate |

L2 norm |

Steps |

Time |

| PGD[24] |

CIFAR-10 |

72.5% |

41.25 |

10 |

0.005s |

| FGSM[5] |

CIFAR-10 |

63.5% |

41.26 |

1 |

0.003s |

| BIM[25] |

CIFAR-10 |

55.2% |

17.49 |

10 |

0.004s |

| FFGSM[26] |

CIFAR-10 |

72.1% |

41.25 |

1 |

0.003s |

| APGD[27] |

CIFAR-10 |

58.19% |

10.42 |

10 |

0.004s |

| Sparsefool[28] |

CIFAR-10 |

91.0% |

54.18 |

10 |

1.962s |

| OnePixel[29] |

CIFAR-10 |

47.9% |

2.58 |

10 |

0.076s |

| Pixel[30] |

CIFAR-10 |

52.9% |

12.66 |

10 |

0.129s |

| PIFGSMPP[31] |

CIFAR-10 |

82.3% |

0.05 |

10 |

0.003s |

| DeepFool[3] |

CIFAR-10 |

23.15% |

0.05 |

1 |

0.056s |

| YOAO(Ours) |

CIFAR-10 |

93.81% |

3.83 |

1 |

0.062s |

| PGD |

MNIST |

3.5% |

0.61 |

10 |

0.003s |

| FGSM |

MNIST |

3.5% |

0.65 |

1 |

0.003s |

| BIM |

MNIST |

4.1% |

0.63 |

10 |

0.003s |

| FFGSM |

MNIST |

3.4% |

0.64 |

1 |

0.003s |

| APGD |

MNIST |

4.1% |

0.02 |

10 |

0.003s |

| OnePixel |

MNIST |

1.7% |

0.16 |

10 |

0.616s |

| Pixel |

MNIST |

89.9% |

6.04 |

10 |

0.723s |

| DeepFool |

MNIST |

30.2% |

1.53 |

1 |

0.040s |

| YOAO(Ours) |

MNIST |

66.5% |

9.01 |

1 |

0.091s |

4.4.2. Performance Comparison Between the YOAO (You Only Attack Once) Algorithm and the DeepFool Algorithm

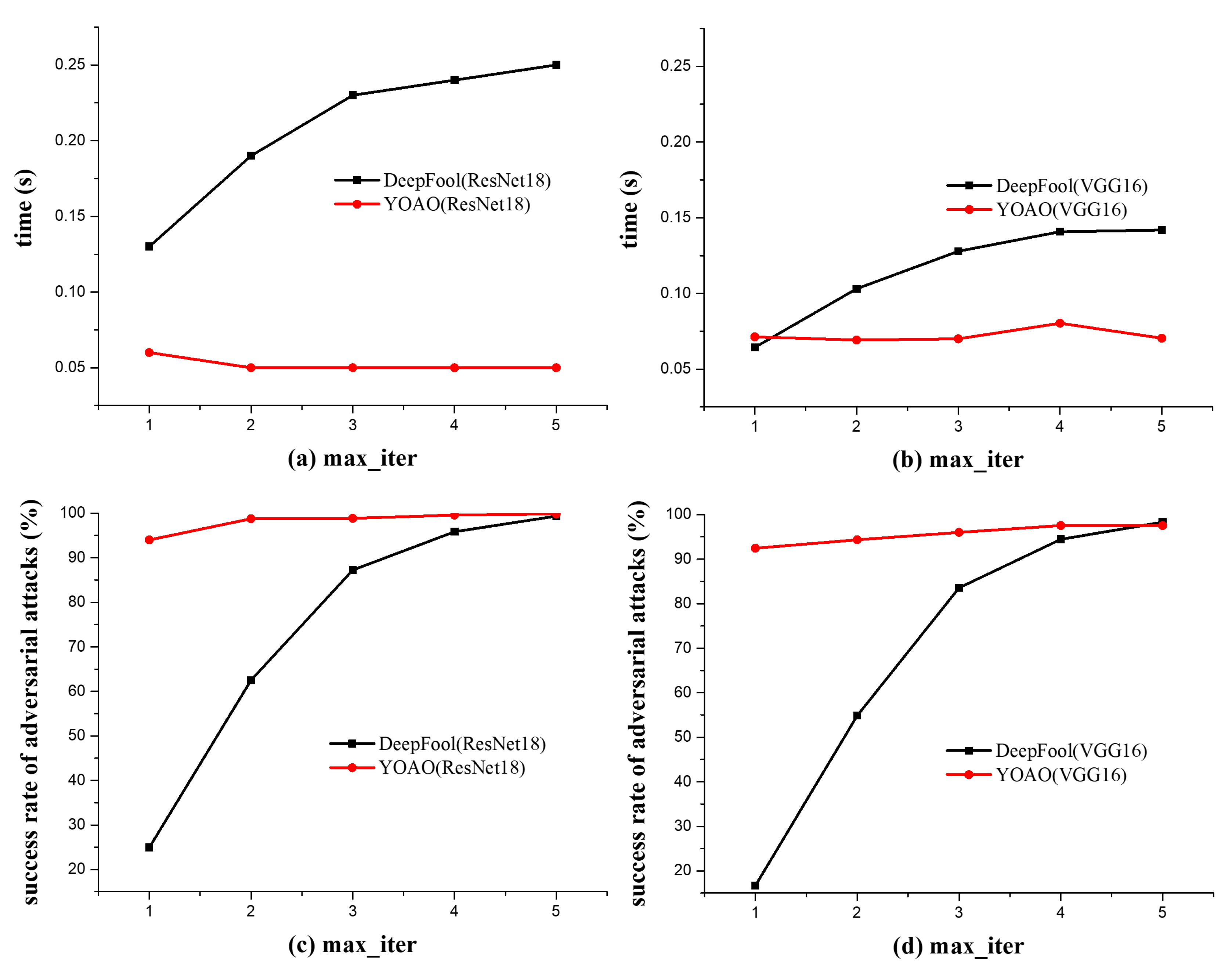

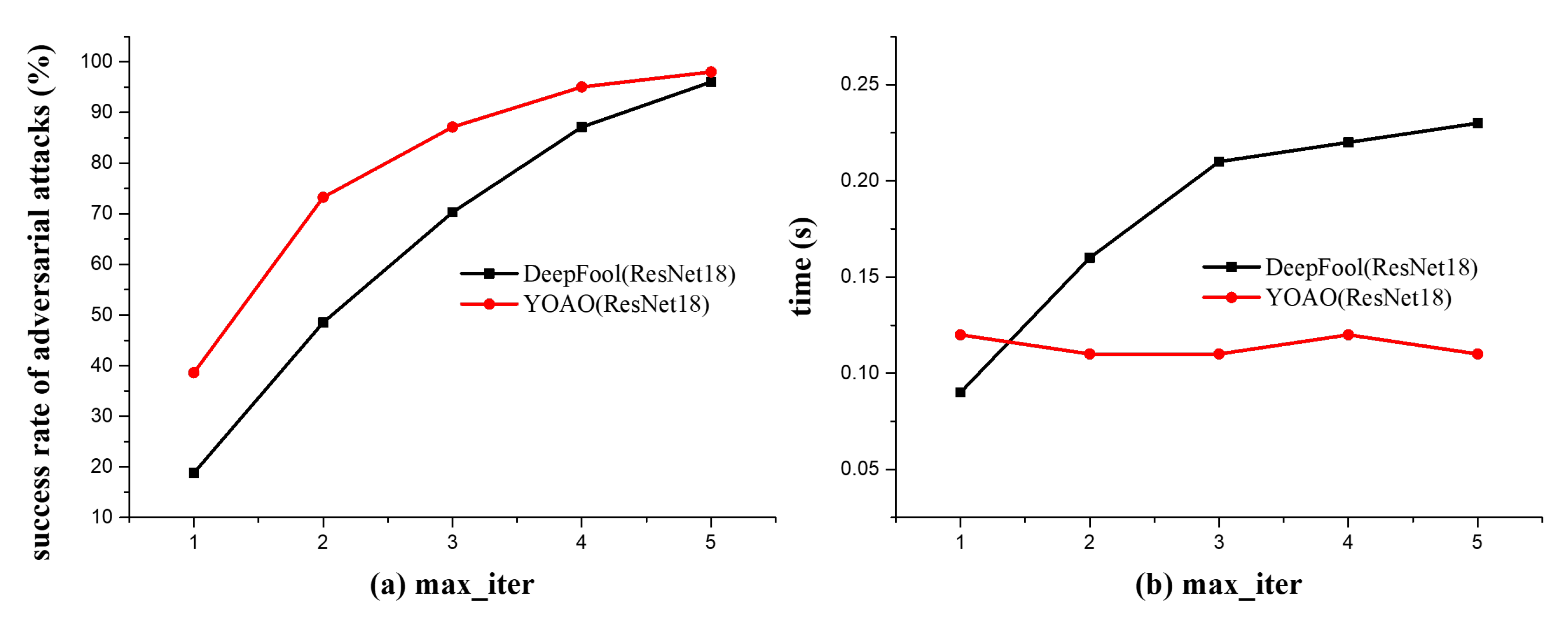

As shown in

Figure 6, based on the data presented in

Figure 6(a) and

Figure 6(b), it is observed that the proposed algorithm (YOAO) exhibits an increase in the time required to generate a single adversarial sample as the maximum number of iterations increases, relative to the original DeepFool algorithm. Further observation of

Figure 6(c) and

Figure 6(d) reveals that the algorithm maintains a high attack success rate across different maximum iteration settings. Particularly noteworthy is that in the case of a single iteration, the algorithm achieves a higher attack success rate compared to the original algorithm, which is one of the reasons why we named the proposed algorithm as "You Only Attack Once (YOAO) ".

These data are sourced from the CIFAR-10 dataset, from which 500 images were selected for experimentation, leading to the aforementioned conclusions. These results demonstrate that the YOAO algorithm has more efficient and effective characteristics than the traditional DeepFool algorithm when generating adversarial examples. By dynamically selecting the gradient update direction for each input data and reducing the search space, The YOAO algorithm can quickly find perturbations that cause misclassification to the target class.

Figure 6.

The impact of the maximum iteration parameter (max-iter) on the original DeepFool algorithm and the YOAO algorithm is illustrated in the four subfigures.

Figure 6(a) and

Figure 6(b) demonstrate the speed of generating a single adversarial sample at different maximum iteration values, while

Figure 6(c) and

Figure 6(d) show the success rate of the algorithm’s attacks under varying maximum iteration settings. In our experiments, we employed two classifiers, ResNet18 and VGG16.

Figure 6.

The impact of the maximum iteration parameter (max-iter) on the original DeepFool algorithm and the YOAO algorithm is illustrated in the four subfigures.

Figure 6(a) and

Figure 6(b) demonstrate the speed of generating a single adversarial sample at different maximum iteration values, while

Figure 6(c) and

Figure 6(d) show the success rate of the algorithm’s attacks under varying maximum iteration settings. In our experiments, we employed two classifiers, ResNet18 and VGG16.

4.4.3. Performance Variation of YOAO and DeepFool Algorithm Under Different Parameters

As shown in

Figure 7, to investigate the impact of classifier accuracy on adversarial attack algorithms, experiments were conducted using ResNet and VGG networks with an accuracy of 60% as classifiers, comparing the performance of the DeepFool algorithm and the YOAO algorithm on the CIFAR-10 dataset. In this section, we employed the ResNet classifier with an accuracy of 95.45% to evaluate the attack success rates and efficiency of both the DeepFool and YOAO algorithms on the CIFAR-10 dataset. It was observed that at a maximum iteration count (max-iter) of 1, the attack success rate of YOAO algorithm dropped to 38%. This indicates that on well-trained classifiers, the attack success rate of YOAO algorithm may decrease. However, as the max-iter parameter is increased, the attack success rate for YOAO algorithm also improves. Notably, under the same parameter settings, the attack success rate of YOAO algorithm consistently surpasses that of DeepFool algorithm. Additionally, the time required to generate a single adversarial sample was calculated for both algorithms, revealing that even with high-accuracy classifiers, YOAO algorithm requires significantly less time to produce a single adversarial sample compared to DeepFool algorithm. This underscores the superior performance of the proposed YOAO algorithm.

4.4.4. Visualization of Adversarial Samples Generated by YOAO and DeepFool Algorithm

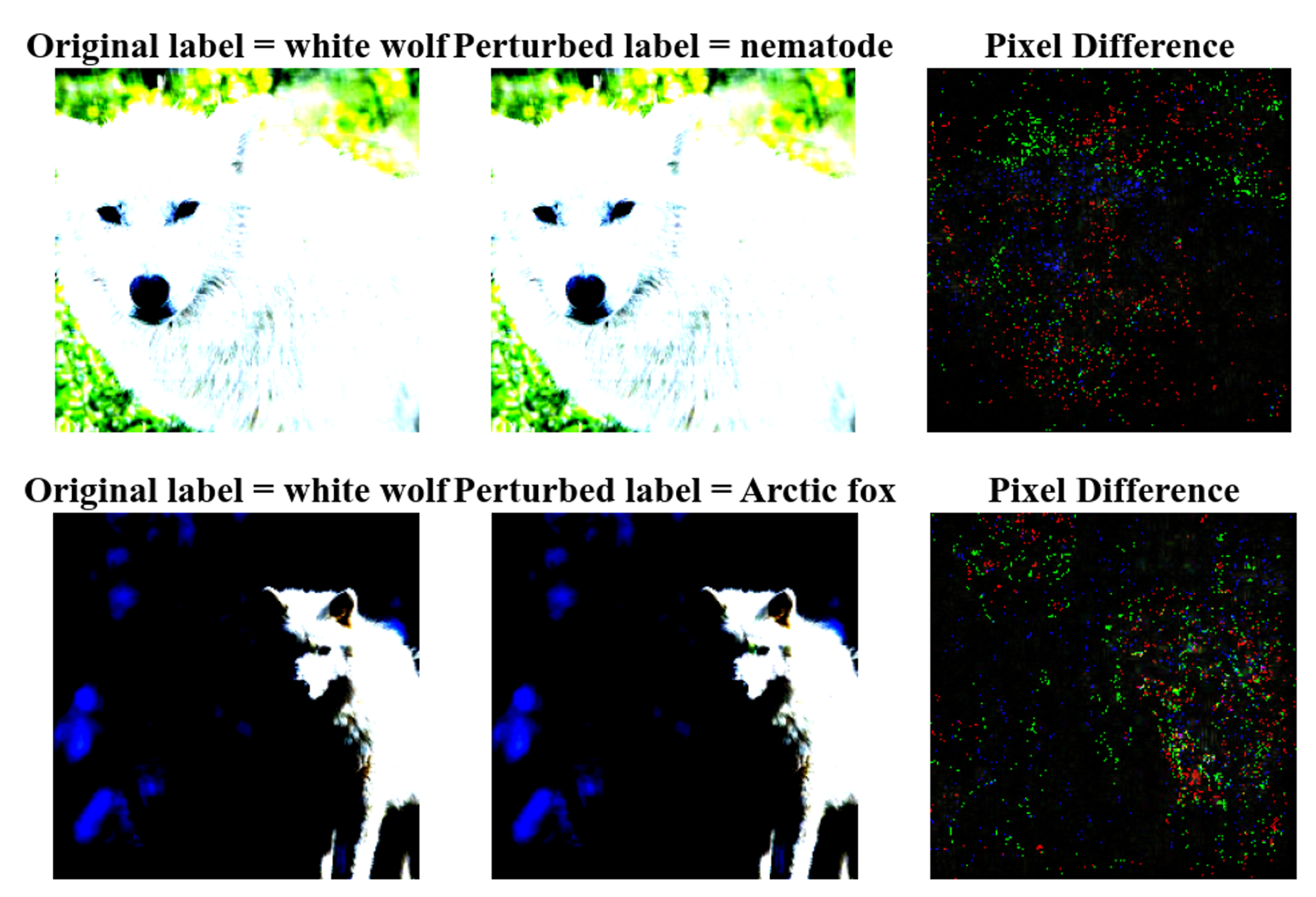

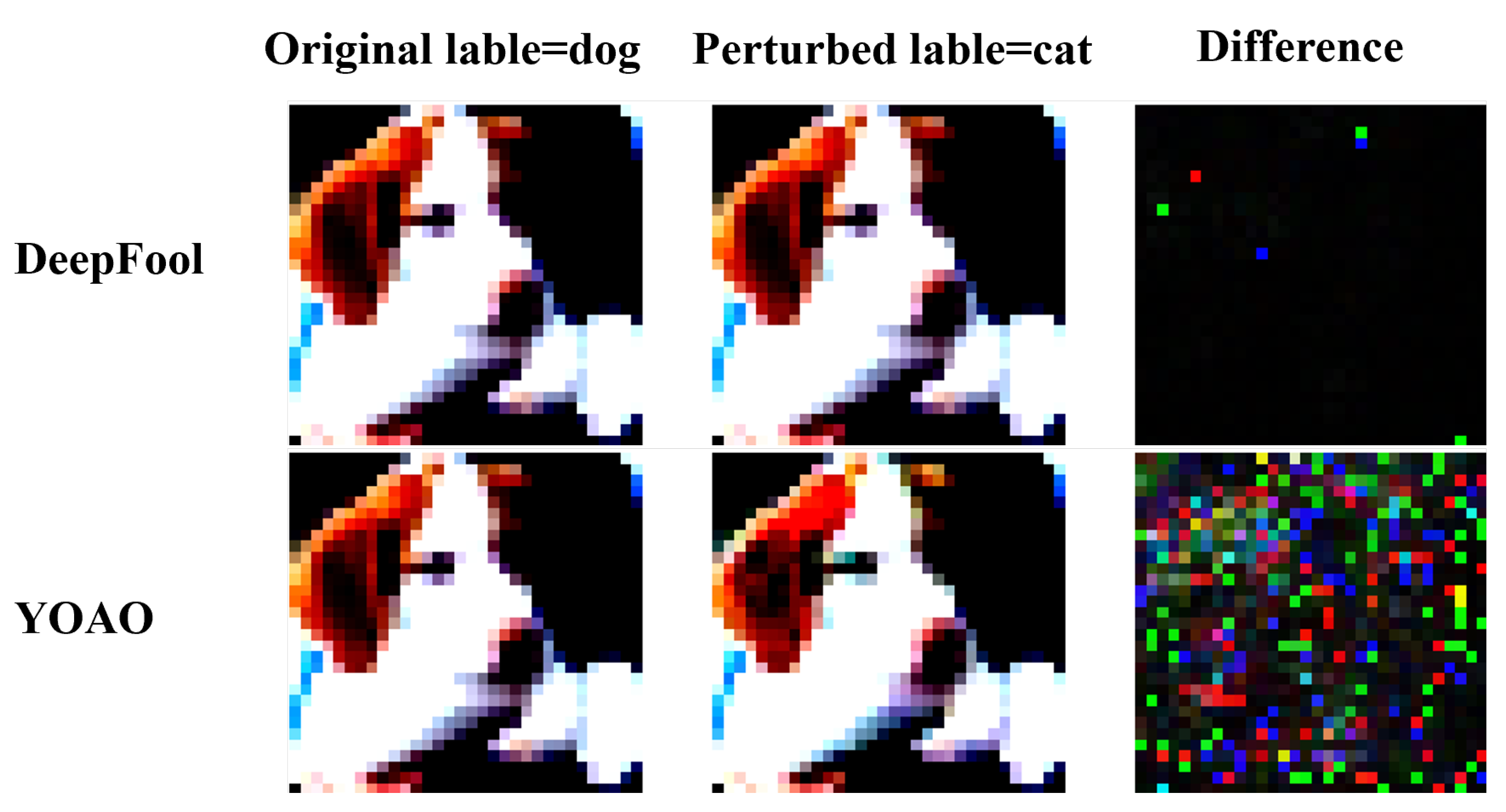

As shown in

Figure 8, in the two sets of comparison images provided, each set consists of three small subfigures: the original image, the adversarial example, and the pixel-wise difference map between them, the top labels clearly indicate the classification results by their corresponding classifiers. It is evident that the classification result of the adversarial example significantly differs from that of the original image, indicating the efficacy of the algorithm used to generate the adversarial sample.

These results were obtained with the max-iter parameter set to 1, signifying that the algorithm underwent a single-step iteration. This suggests that both the YOAO algorithm and the DeepFool algorithm can find adversarial samples within a single iteration, with the algorithm demonstrating higher computational efficiency under this single-step iteration scenario. Despite a slight increase in the magnitude of perturbation, it remains effectively constrained within a small range, making it imperceptible to human observers. This breakthrough not only demonstrates the efficiency of the algorithm, but also underscores its potential in the field of adversarial example generation through optimized algorithmic design. We have achieved results comparable to or even surpassing traditional methods in just a single iteration. Such efficiency improvements not only save computational resources, but also accelerate the application and research progress of adversarial example generation.

In order to extend the applicability of the algorithm to broader domains, we have chosen to employ the ImageNet dataset, which closely mirrors real-world scenarios. As shown in

Figure 9, it is evident that the adversarial samples we generate bear a striking resemblance to the original images, rendering them nearly imperceptible to the naked eye and possessing a high degree of obfuscation. Furthermore, we have conducted a comparative analysis of the differences between the original images and the adversarial samples, visualizing these differences. Through visualization, we are able to discern that the colored regions represent the added perturbation pixels, which closely align with the original image and are predominantly concentrated on the image’s class-specific features. The algorithm perturbs crucial feature components, resulting in misclassification of the images. It is precisely due to the interference with vital features by the algorithm that it exhibits robust adversarial capabilities, even on classifiers boasting an accuracy as high as 99%, while significantly reducing the time required for generating adversarial samples.

By delving into the mechanisms of adversarial sample generation algorithms, we have delved into how classifiers are perturbed, a pursuit that holds significant implications for elucidating the operational principles of models and enhancing their security. A thorough exploration of adversarial sample generation algorithms not only aids in comprehending the vulnerabilities of model, but also offers crucial insights for bolstering model robustness. We are not merely attacking models, we are continuously deepening our understanding of the intrinsic mechanisms of machine learning models, thereby laying a foundation for constructing AI systems that are more secure and reliable.

Figure 9.

This figure illustrates the performance of the proposed algorithm on the Imagenet dataset. The three columns present distinct information: the left column displays the original images, the middle column showcases the adversarial samples generated by the YOAO algorithm, and the right column illustrates the differences between the adversarial samples and the original images.

Figure 9.

This figure illustrates the performance of the proposed algorithm on the Imagenet dataset. The three columns present distinct information: the left column displays the original images, the middle column showcases the adversarial samples generated by the YOAO algorithm, and the right column illustrates the differences between the adversarial samples and the original images.

5. Discussion and Future Work

In this section, we extensively discussed our contributions and highlighted directions for future research. Additionally, we briefly outlined the limitations and fundamental assumptions of our model.

5.1. Discussion on Experiments

We have carefully designed a series of experiments to evaluate the effectiveness of the YOAO (You Only Attack Once) algorithm. Initially, we conducted a thorough comparison between YOAO and other advanced algorithms, assessing their performance in terms of attack success rates, attack times, and L2 norm perturbation sizes. The experiments confirmed that YOAO algorithms performs better than other algorithms, achieving not only a higher success rate in attacks, but also quicker attack times.

Subsequently, we conducted a detailed comparison between YOAO algorithm and DeepFool algorithms across different datasets and classifiers, validating the reasons behind YOAO’s superior attack efficiency. This further emphasizes the importance of optimizing the search for the maximum gradient differences, while also confirming that classes with the greatest gradient differences from the original sample are more likely to impact the classifier’s decisions.

Lastly, we visualized and compared the adversarial samples created by YOAO algorithms and DeepFool algorithms. While YOAO algorithms introduced more changes to the pixels in the generated adversarial samples, we noticed that the perturbation size remained within a small range, making it undetectable to the human eye. This observation underscores the strong attack capabilities of YOAO algorithms, as the perturbations, although slightly higher than those of DeepFool algorithms, are still subtle enough to avoid visual detection.

5.2. Discussion on the Model

In algorithm design, the FGSM (Fast Gradient Sign Method) algorithms computes the sign of the gradient, seeking the direction in each input dimension that maximally increases the loss function, and adds perturbations along that direction to generate adversarial samples. We observe that FGSM algorithms leverages the model’s sensitivity to input variations, where directions with the largest gradients are more sensitive to inputs and thus more likely to produce adversarial samples. Inspired by this observation, we make a similar assumption that in the DeepFool algorithm, directions with the largest gradient differences are more sensitive to inputs. Therefore, we have enhanced the DeepFool algorithm by searching for the class that maximizes the gradient difference from the original sample’s class, enabling faster generation of adversarial samples. Our enhancement leverages the maximization of gradient differences to expedite the generation of adversarial samples. This method exploits the sensitivity differences of the model across different classes, enhancing the targeted and effective generation of adversarial samples.

5.3. Limitations and Future Works

The proposed algorithm requires computing the class with the maximum gradient difference from the original sample class in each run to expedite the generation of adversarial samples. In datasets with fewer classes, we observed faster attack speeds and higher attack success rates. However, when dealing with datasets with a large number of classes, such as image datasets, the process of computing class gradient differences consumes a significant amount of time, resulting in slower attack speeds. We propose the introduction of precomputed gradients or gradient caching mechanisms. Before conducting adversarial attacks, we can perform a single forward and backward pass on samples in the dataset, calculating and storing the gradient of each sample with respect to its correct class. During actual adversarial attack execution, we can directly utilize these precomputed gradients, eliminating the need for repeated forward and backward passes. In terms of adversarial sample detection, the algorithm generates more targeted and effective adversarial samples. Adversarial training, as a crucial defense mechanism, effectively enhances a model’s resilience against adversarial attacks. In the future, we aim to explore further into the field of adversarial training, integrating the proposed YOAO algorithm with existing techniques to strengthen the robustness and security of classifier models. Additionally, we plan to expand our work focus to the robustness and security of object detection models, which is equally critical. By applying our adversarial training approach to object detection models, we hope to enhance their performance when facing adversarial attacks and provide more reliable protection for practical application scenarios.

6. Conclusion

Adversarial attacks expose the latent vulnerabilities within artificial intelligence systems, compelling a reevaluation and enhancement of model robustness to ensure the reliability and security of deep learning models against malicious attacks. The "You Only Attack Once" (YOAO) algorithm, which is central to our research, exploits gradient differences to accurately pinpoint the most susceptible class and effectively craft adversarial examples using a minimal iteration approach. The algorithm plays a role in augmenting the accuracy and efficiency of adversarial attack strategies, as empirical data showcases its superior performance compared to the DeepFool algorithm across a variety of scenarios, particularly in resource-constrained environments. With just a single iteration, the YOAO algorithm achieves a notable 50% improvement in adversarial success rates and a significant 15% reduction in computational overhead. These enhancements are crucial for both defensive and attack strategies in a myriad of machine learning models.

This work further explores the relationship between classifier accuracy and the effectiveness of attacks, comparing the proposed algorithm with existing methods. The experimental results confirm the higher success rate and speed of the proposed approach. Additionally, visualizing data on the ImageNet dataset demonstrates the ability of YOAO algorithm to target important features. In summary, this study not only addresses current algorithmic challenges, but also sets the stage for future research endeavors, promising to enhance the overall understanding and protection of machine learning model security.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and Y.X.; methodology, J.L.; Software, Y.X.; validation, Y.X., Y.H., and Y.M.; formal analysis, J.L. and Y.X.; investigation, X.Y.; resources, J.L.; data curation, Y.X.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L. and Y.X.; writing—review and editing, J.L. and Y.X.; visualization, Y.X.; supervision, J.L. and Y.X.; project administration, J.L. and Y.X.; funding acquisition, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the Jilin Province Budgetary Capital Construction Fund Project (No. 2024C008-4).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ali, M.A.M.; Isa, H.N.; others. Balancing Efficiency and Effectiveness: Adversarial Example Generation in Pneumonia Detection. 2024 IEEE Symposium on Wireless Technology & Applications (ISWTA). IEEE, 2024, pp. 206–210. [CrossRef].

- Vyas, D.; Kapadia, V.V. Designing defensive techniques to handle adversarial attack on deep learning based model. PeerJ Computer Science 2024, 10, e1868. [CrossRef] . [CrossRef]

- Moosavi-Dezfooli, S.M.; Fawzi, A.; Frossard, P. Deepfool: a simple and accurate method to fool deep neural networks. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 2574–2582. [CrossRef].

- Chakraborty, A.; Alam, M.; Dey, V.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Mukhopadhyay, D. A survey on adversarial attacks and defences. CAAI Transactions on Intelligence Technology 2021, 6, 25–45. [CrossRef] . [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Shlens, J.; Szegedy, C. Explaining and harnessing adversarial examples. arXiv 2015, arXiv: 1412.6572. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/1412.6572 (accessed on 20 Mar 2015).

- Kurakin, A.; Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, S. Adversarial machine learning at scale. arXiv 2017, arXiv: 1611.01236. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/1611.01236 (accessed on 11 Feb 2017).

- Naseem, M.L. Trans-IFFT-FGSM: a novel fast gradient sign method for adversarial attacks. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2024, pp. 1–21. [CrossRef].

- Moosavi-Dezfooli, S.M.; Fawzi, A.; Fawzi, O.; Frossard, P. Universal adversarial perturbations. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 1765–1773. [CrossRef].

- Gajjar, S.; Hati, A.; Bhilare, S.; Mandal, S. Generating Targeted Adversarial Attacks and Assessing their Effectiveness in Fooling Deep Neural Networks. 2022 IEEE International Conference on Signal Processing and Communications (SPCOM). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef].

- Labib, S.; Mondal, J.J.; Manab, M.A. Tailoring Adversarial Attacks on Deep Neural Networks for Targeted Class Manipulation Using DeepFool Algorithm. arXiv 2024, arXiv: 2310.13019. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/2310.13019 (accessed on 30 Aug 2024).

- Ling, J.; Chen, X.; Luo, Y. Improving the transferability of adversarial samples with channel switching. Applied Intelligence 2023, 53, 30580–30592. [CrossRef] . [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.C.; Roxo, T.; Proença, H.; Inácio, P.R. How deep learning sees the world: A survey on adversarial attacks & defenses. IEEE Access 2024. [CrossRef] . [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Mu, T. Understanding and improving ensemble adversarial defense. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [CrossRef].

- Szegedy, C.; Zaremba, W.; Sutskever, I.; Bruna, J.; Erhan, D.; Goodfellow, I.; Fergus, R. Intriguing properties of neural networks. arXiv 2014, arXiv: 1312.6199. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/1312.6199 (accessed on 19 Feb 2014).

- Qin, C.; Martens, J.; Gowal, S.; Krishnan, D.; Dvijotham, K.; Fawzi, A.; De, S.; Stanforth, R.; Kohli, P. Adversarial robustness through local linearization. Advances in neural information processing systems 2019, 32. [CrossRef].

- Najafi, A.; Maeda, S.i.; Koyama, M.; Miyato, T. Robustness to adversarial perturbations in learning from incomplete data. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2019, 32. [CrossRef].

- Kuang, H.; Liu, H.; Lin, X.; Ji, R. Defense against adversarial attacks using topology aligning adversarial training. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2024. [CrossRef] . [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Pun, C.M.; Miao, Q. Attack-invariant attention feature for adversarial defense in hyperspectral image classification. Pattern Recognition 2024, 145, 109955. [CrossRef] . [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Chung, M.; Shin, Y.G.; others. Adversarial example denoising and detection based on the consistency between Fourier-transformed layers. Neurocomputing 2024, 606, 128351. [CrossRef] . [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Liu, W. Adversarial self-training improves robustness and generalization for gradual domain adaptation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [CrossRef].

- Russakovsky, O.; Deng, J.; Su, H.; Krause, J.; Satheesh, S.; Ma, S.; Huang, Z.; Karpathy, A.; Khosla, A.; Bernstein, M.; others. Imagenet large scale visual recognition challenge. International journal of computer vision 2015, 115, 211–252. [CrossRef] . [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Hinton, G.; others. Learning multiple layers of features from tiny images 2009.

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [CrossRef] . [CrossRef]

- Mądry, A.; Makelov, A.; Schmidt, L.; Tsipras, D.; Vladu, A. Towards deep learning models resistant to adversarial attacks. stat 2017, 1050.

- Kurakin, A.; Goodfellow, I.J.; Bengio, S. Adversarial examples in the physical world. In Artificial intelligence safety and security; Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2018; pp. 99–112. [CrossRef].

- Wong, E.; Rice, L.; Kolter, J.Z. Fast is better than free: Revisiting adversarial training. arXiv 2020, arXiv: 2001.03994. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/2001.03994 (accessed on 12 Jan 2020).

- Croce, F.; Hein, M. Reliable evaluation of adversarial robustness with an ensemble of diverse parameter-free attacks. International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2020, pp. 2206–2216. [CrossRef].

- Modas, A.; Moosavi-Dezfooli, S.M.; Frossard, P. Sparsefool: a few pixels make a big difference. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019, pp. 9087–9096. [CrossRef].

- Su, J.; Vargas, D.V.; Sakurai, K. One pixel attack for fooling deep neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 2019, 23, 828–841. [CrossRef] . [CrossRef]

- Pomponi, J.; Scardapane, S.; Uncini, A. Pixle: a fast and effective black-box attack based on rearranging pixels. 2022 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef].

- Gao, L.; Zhang, Q.; Song, J.; Shen, H.T. Patch-wise++ perturbation for adversarial targeted attacks. arXiv 2020, arXiv: 2012.15503. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/2012.15503 (accessed on 8 Jun 2021).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).