1. Innovations on Brain Stimulation and Their Applications in Psychiatry and Neurodegeneration

Neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders represent a significant portion of the causes of mortality worldwide, and most importantly, include a detrimental impact on patients´ quality of life. Additionally, dealing with these disorders involves billions of dollars across the world in every country´s healthcare system. The heterogeneity of the brain and, therefore, the complexity of psychiatric and neurological pathologies, in addition to limited efficacy of available treatments and the big percentage of clinical trial failure, pushed for the need and investment in innovative resources.

Currently, we have over 60 million patients worldwide facing neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer´s Disease (AD), Parkinson´s Disease (PD) and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). The rising prevalence and incidence of neurodegenerative disorders highlight the critical necessity for intensified research, improved diagnostic methodologies, and the development of more efficacious therapeutic interventions. Presently, most available treatments are palliative, primarily aimed at symptom management rather than offering a cure for these diseases. Therefore, there is still a need for additional research focused on a better understanding of the alterations mediating those devastating disorders.

We are currently in an evolving era where non-pharmacological approaches for the treatment of neurological conditions are on the rise, either in combination with well-established drug treatments, or on their own [

1,

2].

As far as innovative treatments, electric stimulation has a long history of medical applications. Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is a well-established non-pharmacological treatment approved for its use in a variety of conditions, such as depression, compulsive disorders and PD [

3,

4]. It involves the use of electrodes placed near deep structures of the brain, and connected to a wire and pulse generator, which will fire the electrodes when instructed by a computer [

5]. Additionally, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), approved for unipolar depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) [

6], is capable of inducing small electric currents in a contained area via application of a rapidly changing magnetic field to the superficial layers of the cerebral cortex. Less invasive neuromodulation techniques are being used, including transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), whose way of working is by direct weak electric currents through scalp electrodes to induce changes in cortical excitability near the anode or the cathode, respectively [

7,

8]. In parallel, ultrasound approaches have been 'rediscovered' as an advanced engineering technique, which has unprecedented accuracy for reaching small areas of the brain [

9]. Additionally, ultrasound is not sensitive to changes in conductivity, which makes this approach unique from other methods that require significant changes in normal conductance [

10]. Currently, Transcranial Pulse Stimulation (TPS), an ultrasound-based technique that uses ultrashort pressure pulses (3 μs), has been approved for AD treatment [

10].

Going even further, brain-computer interfaces (BCI) have provided a great potential in the treatment of a wide array of neurological disorders [

11,

12,

13] via new output pathways [

14]. Since 1973 progress has slowly been made to bring the technology to a point where it can potentially be used in a clinical environment [

15]. Indeed, there are several BCI technologies that as of 2021 were being tested in clinical trials, targeting different neurological conditions [

16].

As of today, perhaps the most well-known BCI technology is Neuralink, Elon Musk’s foray into medical sciences. This technology is composed of ultra-fine polymer probes or “threads”, a neurosurgical robot, and customized high-density electronics. The threads record neuronal activity and send it to the custom chip, which decodes the electrical signal from the brain and transmits it to a digital device. Testing of this technology in Long-Evans rats allowed for the recording of widespread neuronal activity [

17]. Testing for the Neuralink implant has also been done in primates, and even in the first human. However, there is not much information readily available on the results of either trial. Neuralink reported that the monkeys were able to play Pong without the use of physical controllers, although the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM) raised an issue on the treatment and death of the primates [

18,

19].

As for the first human patient, Noland Arbaugh, he was able to utilize Neuralink’s implant to control digital devices. Recently though, it seems as if most of the implant’s threads have become unresponsive, limiting his control of external devices [

20]. Even so, the FDA has green-lit the implant for clinical trials and the company is currently recruiting participants for their N1 implant and R1 robot. If successful, it would allow tetraplegia patients to control digital devices through their implants [

21].

However, according to Zhang & Dai (2024)[

22], the day after Tesla CEO Elon Musk announced his successful implantation, China's Tsinghua University announced that they had successfully rehabilitated the first BCI patient with their wireless device, meeting the highest safety standards. Interesting discussions are taking place in regard to the invasiveness of current BCI with promising outcomes. Additional BCI implants continue to gain attention, such as Synchron with their new endovascular electrode, the Stentrode, which is currently being used in the clinic, and enables neuroprosthetics, neuromodulation and neurodiagnostics [

23,

24].

How far have we arrived in regards to the use of those innovative approaches into neurodegeneration treatment? Neurofeedback (neurorehabilitation using BCI) provides real-time information of neural activity that is made available to the patient, therefore, allowing learning to control neural activity and, consequently, target symptomatology. Limited and promising data demonstrated that BCI improved independence and autonomy in ALS patients, despite the progressive decline of their neuromuscular functions [

25,

26]. Several studies tested BCI in PD, where BCI showed to improve locomotor ability and alleviate some additional symptoms [

11,

12]. As recently reviewed [

27], BCI requires additional studies before we can implement it in clinical setup. Neuralink also proposes to target neurodegenerative diseases, but lots of questions are still raised on regards to its safety and efficacy of the device due to the requirement of neurosurgical robots to implant the device’s magnitude of electrodes [

28].

Although promising, most of the innovative approaches mentioned above still have limited data supporting its use for neurodegenerative disorders. Even though TMS has been around for decades, it is still only approved for psychiatric conditions such as depression [

29] and OCD [

30]. DBS remains the “gold-standard” technique when considering stimulation approaches for brain targeting.

The development of more sophisticated and precise techniques, such as neural interfaces, has opened new frontiers in neurology and neuroscience, providing opportunities to understand the brain and develop therapeutic devices to restore or replace lost functions. A potentially more significant societal contribution lies in elucidating the benefits conferred by these technologies to patients, as well as the underlying mechanisms responsible for these effects. For that purpose, it is mandatory to better understand the electrical characteristics of the brain, which includes identifying the specific brain regions and neurotransmitter pathways involved, which respond to both chemical and electrical inputs. Targeting those neurotransmitters is instrumental in achieving such remarkable therapeutic outcomes.

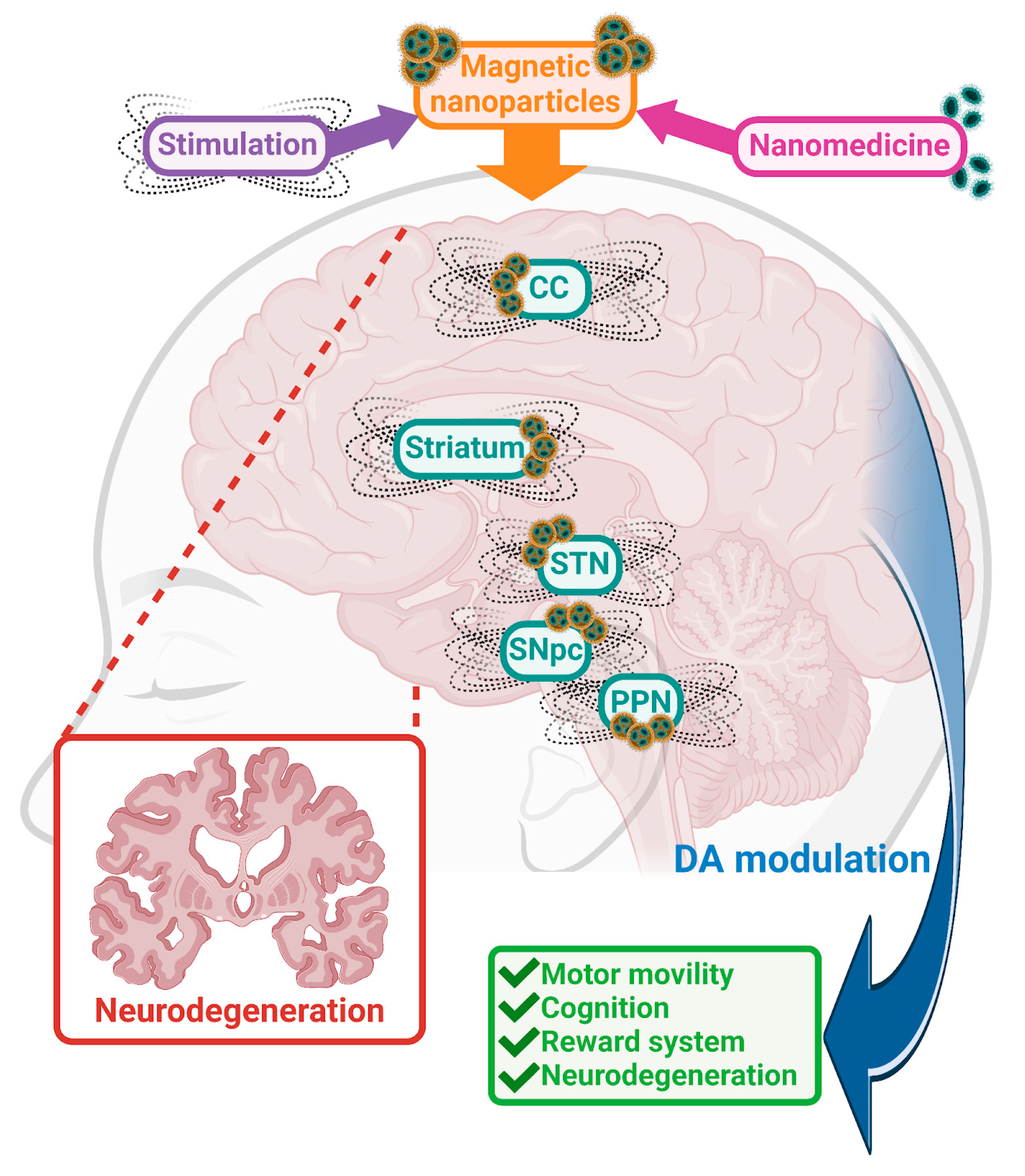

The expanded sections of this review integrate contemporary insights essential for the prudent application of brain stimulation in complex contexts like neurodegenerative disorders. Our understanding of how electric and magnetic stimulation elicits responses in the brain, along with the biochemical pathways involved in neurodegeneration, remains actively investigated. Moreover, identifying the specific brain regions implicated in these processes holds significant importance. Notably, given dopamine's (DA) pivotal role across various neurodegenerative conditions, particular emphasis is placed on elucidating alterations within the dopaminergic system.

2. Brain Stimulation Therapeutic Intervention in Neurodegenerative and Psychiatric Conditions

Due to the complexity of the brain, we continue to uncover underlying mechanisms that mediate specific symptoms of these disorders. Improved characterization of specific targets and their roles within distinct brain regions in pathological conditions could enhance the development and efficacy of innovative treatment approaches.

2.1. Therapeutic Targets: Dopaminergic Alterations

The DArgic system, through various circuitries, has been strongly associated with neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders. DA is a key neurotransmitter involved in numerous processes, including motor function, cognition and reward. The DArgic system has been proposed for decades as a target for neuromodulation to control symptoms in patients with various pathologies. In the following section, we will describe DArgic implication in the most relevant neurodegenerative disorders as well as in drug addiction. In addition, section 2.2 will focus on the brain areas that are being studied to impact the DArgic system in such disorders.

2.1.1. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) Symptomatology and Underlying Mechanisms: Hyperexcitability and Dopaminergic Implication

ALS is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by progressive motor symptoms and cognitive behavioral changes via its alterations on superior and inferior motor neurons (MNs). The inclusion of pathological TDP-43 aggregations (hallmark of the disease) spread initially from MNs in motor cortex, spinal cord and brainstem motor nuclei to other brain regions, such as neocortical areas, cerebellum and striatum [

31]. With no cure or even a fully effective treatment available, current stimulation devices have helped its pathophysiological understanding and the development of new diagnostic approaches [

32].

Current treatments for ALS are based in pharmacological approaches targeting glutamate excitotoxicity (FDA-approved riluzole), oxidative stress (for example edaravone), inflammation, or therapies trying to clear the TDP-43 formation [

33,

34]. Due to its complexity, stimulation approaches have also made their way to clinical trials [

32] highlighting which brain area they focus on: the motor cortex). TMS offers a promising approach for the treatment of ALS, with the potential to alleviate symptoms and improve the patients ‘quality of life [

35]. However, some research suggests that DBS may have potential therapeutic effect in ALS by targeting specific brain regions associated with symptom management or by modulating neuroplasticity and neural networks.

DA and glutamate are two of the main mediators of the characteristic cortical hyperexcitability, an early feature of ALS patients. It affects mostly the corticomotor neurons, the key factor of this devastating neurodegenerative disorder [

36,

37]. DArgic imbalance on the nigrostriatal and mesolimbic pathways is crucial in ALS pathology [

37,

38], contributing to motor and nonmotor symptoms. Reduced DA levels were found using PET in ALS patients [

37] and preclinical animal models [

39]. Additionally, decreased D2 receptors in striatal areas were reported in ALS patients [

40]. Recently, D2 receptors have been confirmed as modulators of ALS motor neuron excitability in clinical trials [

41,

42]. Notably, in the ALS mouse model, 50% of the DAergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) were lost, highlighting the severe involvement of the DArgic system in late-stage disease, and suggesting significant implications for understanding and treatment of ALS [

39]. The use of D2 DA agonist improved motoneuronal function in animal models as well as human trials [

41,

42,

43]. Target of the DArgic pathway using cerebral DA neurotrophic factors (CDNF) also seems to be an innovative and effective treatment for ALS which has shown promise in increasing DA activity via neuroprotective and neurorestorative effects on DA neurons [

44].

Since the motor neuron degeneration in ALS is not localized [

45], the principal aim of DBS when used in ALS patients is to provide symptomatology relief, especially regarding movement-related symptoms, muscle stiffness and tremors.

2.1.2. Huntington Disease (HD) Symptomatology and Underlying Mechanisms: Dopaminergic Hyperactivity

Another deadly neurodegenerative disorder, Huntington disease (HD), is an hereditary disorder with an early onset [30-50 years, [

46] characterized by involuntary choreatic movements, in addition to cognitive problems [

47]. The progressive loss of neurons has been localized in several brain areas, which could explain the variety of symptoms involving motor, cognitive, and even sleep disturbances [

48].

Preclinical and clinical studies have shown that the DA system plays a crucial role in HD development. Abnormal DA/glutamate interactions may explain why the cortex and striatum are so vulnerable in the HD [

49]. Research in HD patients and in rodent genetic models has revealed changes in DA level and its receptors in the striatum, as well as alterations in DArgic receptor signaling [

50] Research in human brains affected by the disease has revealed that, in the early stages of progression, DA levels increase, while in advanced stages it decreases [

48]. This increase in early phases may contribute to the involuntary movements characteristic of the disease, known as chorea [

51]. Positron emission tomography (PET) studies of HD mouse models show significant reductions in D2 receptor density in the striatum, cortex and dentate gyrus, even before the onset of overt symptoms [

52]. Alterations in DA homeostasis seems crucial on the disease, especially in the motor and cognitive symptomatology, with previously described aberrant DA receptor mediation and DA release even before symptoms are evident [

52].

DA stabilizers were proposed as a promising new treatment option for HD [

53]. One of the most commonly used pharmacological treatments in HD is the use of anti-dopaminergic agents [

54]. Pripodine, a DA stabilizer, via its action on the DA D2 receptor belongs to a new class of compounds called dopidines, which has been found to regulate motor activity in HD models. In experiments with R6/2 transgenic mice (model of HD), pridopidine has been shown to improve motor function [

53]. Depending on the stage of the disease and the increase or decrease of DA levels, pripodine stabilizes DA levels and brings them to control levels [

55]. Preclinical research indicated that pridopidine can normalize motor function by reducing locomotor hyperactivity caused by DA or by increasing low locomotor activity in habituated animals, without influencing normal locomotor activity [

56]. Tetrabenazine (TBZ) (via inhibition of monoamine uptake into granular vesicles of presynaptic neurons) is commonly used to reduce brain monoamines and treat chorea in the disease [

57,

58]

Brain stimulation in HD patients has also been used as a means to restore aberrant signaling associated with the disorder [

59,

60]. This intervention is expected to impact the aforementioned dysregulated DArgic pathway.

2.1.3. Alzheimer´s Disease (AD) Symptomatology and Underlying Mechanisms: DA and DA Receptor Reduction

AD is the most common form of dementia, being responsible for 60-70% of the diagnosed cases. As a progressive neurodegenerative disorder, there is an ongoing cognitive decline characterized as mild, moderate and severe. DArgic dysfunction has gained attention in the etiology of AD. Between the well characterized neuronal lose present in AD, the association of DA and DA receptors levels to AD are still a matter of discussion. There is agreement on altered DA levels, but contradicting evidence points towards both increased and decreased DA levels depending on the patient [reviewed in 61] However, the authors highlight the more prominent set of data towards hypodopaminergic function (reduced DA and DA receptor levels) in AD. Important sex differences have also been described in regards to DA levels in AD patients, which seems relevant due to the higher risk of AD development in women [

62]. A marked decrease of D2 receptors in hippocampus and frontal cortex were found in AD patients ́ brains [

63]. The use of pharmacological agents targeting the DA system seems to be beneficial for those patients at different stages of neurodegeneration; with some acting as DA agonists [

64,

65,

66,

67] while some others seem to act as inhibitors [

68,

69]

Approved medication to treat AD includes Donepezil, Rivastigmine and Galantamine (cholinergic enhancers) as well as memantine (NMDA antagonist). Interestingly, most of those drugs have shown to increase DA release [

70,

71]. Lecanemab is the most recently (2023) approved treatment for AD, which has shown to slow the cognitive as well as functional decline in patients at the early-stage of the disease progression [

72]. However, lots of discussion has followed its approval [

73].

The relevant role of DA in cognitive processes is undeniable [

74,

75] as well as how alterations on the DA system correlate with memory disturbances found in AD in clinical and preclinical studies, specially due to its role in the hippocampus [

76,

77]. Unsurprisingly, targeting on that brain area and the DArgic system on AD patients has been the focus of interest of many researchers across the years. Stimulation approaches such as DBS and transcranial current stimulation (tACS) show promising beneficial results in AD, although they also have limitations [

78,

79,

80,

81].

2.1.4. Parkinson's Disease (PD) Symptomatology and Underlying Mechanisms: Dopaminergic Loss

PD is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder, currently understood by an interplay of genetic and environmental factors [

82]. PD has been related to defects on the direct DArgic pathway, whose main role is to boost movement [

83]. PD is characterized by motor disturbances such as tremor and bradykinesia associated with Lewy bodies, and the loss of DArgic neurons in the Substantia Nigra pars compacta (SNpc) [

84,

85].

The primary treatment option for PD focuses on targeting the DA system, aiming to increase its levels in the synaptic cleft. The drug treatment by excellence is L-DOPA, a DA precursor that has been shown to reduce altered motor disturbances in PD [

86]. However, it suffers from lots of limitations, such as a quite short effect on the patients and adverse reactions such as dyskinesias [

87]. For decades, direct modulation of the DA pathway, through the use of agonists on D1,D2, D5 receptors, has proved efficacy in alleviating PD symptoms in clinical trials [

88,

89,

90]. Polymorphisms on multiple DA D3 receptors have also been linked to PD susceptibility [

91].

Additional pharmacological agents targeting the DArgic system are still booming. Produodopa (acting as DA precursor) was recently approved in some countries [

92] but displays some limitations that are currently slowing down its approval for its use worldwide, as it also happens with so many other agents [

93]. However, alternative treatments using brain stimulation continue to be explored, focusing on relevant brain areas for motor control [for more detail see 94–95].

2.1.5. Drug Addiction: Underlying Mechanism Related to Dopaminergic Implication

Drug addiction processes share altered neurobiological pathways with neurodegenerative disorders. There are genetic, as well as environmental factors, that can contribute to both groups of disorders. DArgic alterations in neurodegenerative disorders, and, therefore, treatment focused on boosting DA levels, could lead to addictive behaviors. It could increase likely to additional substance abuse or vice versa, drug addiction could enhance vulnerability to neurodegenerative disorders. For example, in PD treatment with DA precursors, patients develop addiction to DA agents due to the rewarding effects perceived after treatment [

96]. However, drug abuse, such as under alcohol addiction, has been shown to hasten AD progression [

97]. Notably, the impact of environmental circumstances, such as those inducing oxidative stress, have proved to alter underlying mechanisms common to both conditions, inducing neurodegeneration [for example 98] as well as addiction [

99]. Therefore, a review on the role of DA in drug addiction is included in this section.

Drug addiction is a chronic psychiatric disorder characterized by compulsive drug-seeking and drug-abusing behavior. As discussed previous sections, the DArgic reward system (mesolimbic DA) is a key driver of addiction, and its dysfunction is a defining characteristic of drug addiction. The effects of most drugs of abuse are mediated by large and rapid increases in the level of DA in the Nucleus Accumbens (Nacb). D2 receptors as well as DA signaling have been proposed as biomarkers of drug vulnerability due to their link to impulsivity [

100]. Decreases in D2 receptors and DA release have been described in individuals with substance use disorders [

101]. A general hypodopaminergic state has also been described after prolonged use of drugs [

102]. This reduction in DArgic response is implicated in the neurobiological alterations associated with addiction, contributing to the compulsive drug-seeking behavior and decreased sensitivity to natural rewards observed in these patients. Decreases in DA function have also been associated with reduced regional activity in the orbitofrontal cortex (involved in salience attribution; its disruption results in compulsive behaviors), cingulate gyrus (involved in inhibitory control; its disruption results in impulsivity) and dorsolateral PFC (involved in executive function; its disruption results in impaired regulation of intentional actions) [

103]. Additionally, DA transporter (DAT), crucial mechanisms for physiological DA homoeostasis, is the principal target site for multiple psychostimulant drugs, including cocaine and amphetamine [

104]. Interestingly, mutations on the DAT gene have been related to vulnerability to drugs such as alcohol [

105] or heroin [

106].

For most of the addictive drugs there are currently approved medications to stop or even reduce the intake. There are some promising compounds that have some efficacy reducing craving, intake or relapse (f.e. antatbus for alcohol, methadone or naltrexone for opioids). Even though it is limited, stimulation approaches are being tested for drug addiction [

107]. It has been hypothesized that DBS may alleviate addiction symptoms through normalizing DA levels and restore the functioning of the reward system [Kuhn et al., 2013]. Additional studies are necessary to confirm the efficacy of DBS in treating substance use disorders, and to establish its long-term safety and effectiveness [

108]. It has been hypothesized that DBS may alleviate addiction symptoms through normalizing DA levels and restore the functioning of the reward system [

109].

2.2. Brain Localization of Aberrant Signaling

After reviewing the primary alterations in neurodegenerative disorders involving DArgic disturbances, it is crucial to identify specific brain regions where these alterations take place, in order to guide treatment strategies. Pharmacotherapy has been instrumental in elucidating the role of neurotransmitters in these pathologies. However, considering the specific functions of brain regions and their connectivity, is also a critical aspect of effective treatment, particularly when employing stimulation approaches.

DArgic cell bodies are located mostly in the midbrain, in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and Substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc), areas that play crucial roles as modulators of their projecting areas. Most of the SNpc neurons project to the cerebral cortex (CC) and the dorsal striatum (referred to as the nigrostriatal pathway). Additional projections from the VTA also connect to the ventral striatum, including Nacb, the DArgic pathway can cause a variety of symptoms depending on their origin. Due to the presence of DA across the brain, it is crucial to know each brain area, its functions and the role of DA in order to investigate new targets, thus helping to improve and reverse symptoms.

Clinical trials and preclinical animal models employing brain area stimulation have provided significant insights into the DArgic system, highlighting its importance as a therapeutic target for neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders.

Despite the innovations mentioned in

Section 1, knowledge in regards to the specific role mediated by stimulation approaches in neurodegenerative and psychiatric conditions pertains mostly to the use of DBS. The year 1987 marked a pivotal moment in the understanding of the brain as an electrical circuit, with the first publication reporting the use of the subthalamic nucleus (STN) as a target for alleviating motor symptoms in PD patients. Almost 40 years later DBS continues to be the main stimulation technique used in clinical setting to treat motor disturbances. Since then, numerous studies have helped providing support to the use of brain stimulation on neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders. Importantly, recently an algorithm has been created to generate personalized and symptom-specific DBS treatment plans, which ensures a more beneficial use of DBS [

110].

Although initial studies focused on the STN, it is crucial to review the literature to better understand the roles that various brain regions can play as targets for symptom recovery in neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders. Despite limited supporting data on some of these brain areas, it is important to explore the findings related to them, given their known roles in the symptoms of these pathologies. As discussed, DA is distributed throughout the brain, and disruptions in DA homeostasis have been implicated in neurodegeneration. Therefore, identifying the most effective brain targets could significantly benefit future patients. Deciphering alterations in specific brain signaling using correlational studies could help identify aberrant activity of brain areas that could serve as reliable biomarkers of individual disease [

111].

2.2.1. Subthalamic Nucleus (STN)

The STN is one relevant area inside the basal ganglia, recognized as a clinical target for treating motor symptoms in disorders such as PD [

112]. It continues to be the most common target for stimulation directed to treat neurodegenerative disorders, such as PD [

113]. Importantly for its role in motor control, the STN has projections to the cerebellar cortex [

114]. STN-DBS also correlated with decreased glucose metabolism in the striatum and thalamus, and with increases of metabolism in cortical and limbic cortex [

115] giving support to the important of the role that these brain areas have in mediating effects on projection sites. Stimulation of the STN influences the DArgic system, for example, by decreasing VMAT2 in additional brain areas such as the caudate, putamen and cortical and limbic regions, areas strongly implicated in movement control [

115]. STN-DBS, in preclinical studies, resulted in increased survival and firing of DArgic neurons in PD rodent models [

116,

117,

118,

119,

120], which also leads to an increase of production of DA in other brain areas such as the SNpc, reducing the motor symptoms [

121]. Increase and normalization in D1 receptor levels, as well as strong decreases in D2 and D3 receptor expression, in Nacb and striatum were also found after STN-DBS stimulation in PD rodent models [

122].

Additionally, STN stimulation modulates DA metabolism by increasing vesicular DA release and increasing DOPAC/dopamine ratio [

123]. Effects of DBS in STN on DArgic cells in pre-clinical models could involve reduced excitotoxicity and increased dendritic spine density [

124]. DBS in STN has also been considered a promising therapeutic strategy in the treatment of specific addictions where DA levels have been described to be altered; DBS may thus lower the basal level of DArgic neuron activity in these structures and ultimately alter the patient´s reactivity to the stimuli [

125].

However, some results differ consistently in regards to STN-DBS impact on the DArgic system, depending on the methods being used. Level of stimulation is important and should be considered when choosing a brain area to be stimulated. For example, STN-DBS significantly reduced the spiking activity of DArgic cells in the SNpc PD pharmacological rat model when using 150 Hz, 60 us, 400 uA [

126] compared to the increased DA firing rate after SNT stimulation in Benazzouz et al. work [

127] that used 130Hz and 300 uA using a lesion PD model.

There is strong support from clinical trials showing its beneficial effects of STN-DBS in patients. A lot has been explored with the stimulation of STN for PD. STN- DBS also improved gait parameters in PD patients [

128]. Specifically, there have been reported improvements in tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, gait, postural stability and additional activities of daily living in those patients [

129]. SPECT images showed that STN-DBS in PD patients undergoing simultaneous L-Dopa treatment showed increased postsynaptic striatal D2R availability, accompanied by a lack of progression of the motor symptoms [

130]. More recently, STN-DBS had beneficial effects improving motor symptoms in PD patients, benefits that were further enhanced when combined with DArgic treatment [

131]. Importantly, the stimulation of the STN had broader effects on PD patients, aside from motor improvements, cognitive function and mood also increased, with depression scores reduced by 40% [

115].

However, targeting the STN is not exclusive to PD studies. STN-DBS could decrease the response to cocaine [

125]. Moreover, DBS of the STN is also proposed in HD cases where response to medication does not improve motor symptoms, with efficacy in chorea symptoms [

132,

133].

2.2.2. Substantia Nigra Pars Compacta (SNpc)

The SNpc is a critical brain region due to its role in the production of DA. The most important function of the SNpc could be its role producing DA and its connections and DA distribution across other brain areas. SNpc releases DA to the striatum, which later on projects to basal ganglia. Additionally, this last brain area connects to the thalamus and motor cortex [

134]. Due to the projections connecting SNpc and other relevant structures, it has an important role modulating mainly motor control and coordination. However, the SNpc is also involved in the control of reward processing, which implicates learning as well as motivation aspects.

Alterations of DA in the SNpc have been previously described in neurodegenerative disorders. For example, loss of DA in the SNpc projections to VTA have been described in mice models of ALS [

135]. It has also been suggested that there is an excess of DA production from the SNpc on HD [

136]. Increased numbers of DArgic cells have been found in the SNpc after treatment with tetrabenazine (inhibitor of monoamine uptake) in HD rat model [

58]. One of the main hallmarks of PD is the loss of DA neurons in this area, the main factor of the imbalance of DA levels found on its projection sites on these patients [

137]. Pathological lesions in the SNpc were also confirmed decades ago in patients diagnosed with AD, where a loss of neurons was demonstrated [

138]

Even though the SNpc has been recognized as a relevant brain area due to its role mediating DA levels, has mainly been the target of stimulation to recover motor impairments in PD. For instance, DBS on the SNpc showed to have therapeutic effects on PD preclinical models, protecting SN neurons [

139] and improving akinesia [

140] in PD rat models, as well as in clinical trials where, for example, SN stimulation showed to improve gait parameters [

128]. Moreover, High frequency DBS of the SN, more precisely the SN reticulata (SNr) could promote extinction and prevent reinstatement of methamphetamine-induced CPP in drug addiction [

141].

2.2.3. Cortical Cortex (CC)

As the largest brain structure, as well as a highly complex one, targetting the CC could be used to mediate in a wide variety of neural functions. The CC contains areas related to sensory and motor control and additionally boasts countless connections to other relevant brain areas. Therefore, lots of attention has been set on its possible role as a target of stimulation approaches in neurodegenerative disorders. It is particularly relevant that cortical areas can be directly altered by DBS as well as by stimulation in projected areas such as the STN [

142,

143].

In the context of ALS, rTMS has been investigated as a potential therapeutic intervention to address changes in cortical excitability and improve some of the symptoms of the disease [

144]. A study used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to measure grey matter atrophy (cortical and subcortical) in ALS patients. Compared to healthy individuals, ALS patients experience significant grey matter loss that worsens with disease progression, regardless of the rate of progression [

111]. This fact gives support to the hypothesis about the beneficial effects of stimulating such areas in those patients. By regulating cortical excitability, motor neuron degeneration can be prevented. Repetitive stimulation may encourage the formation of new neural connections and brain restructuring, which could compensate for the loss of MNs in ALS patients [

144]. In the context of addiction, direct stimulation of the cortex provided important effects on extinction processes as well as on relapse [

145,

146].

2.2.4. Striatum

Communication from the CC to the subcortical region in the basal ganglia, the striatum, takes place mainly via glutamate. However, this connection is ultimately regulated by the DA [

147]. The striatal structure plays a crucial role in the coordination of movement [Cataldi et al., 2022], as well as in various cognitive and emotional functions [

148].

Increasing data supports targeting the striatum for its beneficial effects in several disorders where DA plays a main role. Compared to levels observed in healthy individuals, in ALS patients DA receptor levels were markedly reduced in some brain regions: Nacb, part of the striatum, the superior frontal gyrus on both sides of the frontal lobe, the left temporal lobe and the angular gyrus region. This reduction what was associated with mild cognitive impairment in ALS [

149]. Functional and structural changes also occur in the striatum of HD patients [

58]. Previous studies using striatal DBS show its effect increasing well-being and reducing craving in addictive patients [

150,

151]. Consistently, DA levels are decreased after DBS stimulation of the striatum, more precisely the Nacb [

152].

In drug addiction treatment, the Nacb is a primary target site for stimulation, impacting both the reward and the aversion processes, playing a role in neurobiological circuits for withdrawal or cravings [

108]. Precisely, Nacb stimulation has shown beneficial effects in treatment of heroin [

153], morphine [

154,

155], cocaine [

156,

157], alcohol [

158,

159,

160] and opioids [

161] due to its direct impact in DA and DA receptor action.

2.2.5. Pedunculopontine Nucleus (PPN)

The PPN is another relevant brain area of the mesencephalic locomotor system, playing a modulatory effect in many motor and non-motor features [

162]. It has been the focus of attention due to its role in axial motor functions, specifically in symptoms such as gait freezing and falls in PD conditions where PPN-DBS showed beneficial effects [

163]. Its DBS is recommended mostly in severe medication refractory gait freezing only at low stimulation frequencies.

The stimulation of the PPN has shown to be an effective treatment of postural instability and gait disorders [

164]. Dayal et al., [

165] summarizes relevant cases where PNN stimulation yielded significant results in PD patient´s symptomatology; however, they describe the relevance of the subtype of the disorder to better benefit from the stimulation.

The PPN stimulation has been considered for other neurodegenerative disorders such as Multiple System Atrophy (MSA), Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP) [

166,

167], due to the prevalence of movement symptoms including gait and postural issues and loss of balance. However, the data supporting its DBS is limited.

2.2.6. Globus Pallidus (GP)

The GP is an additional subcortical structure of the brain, a component of the basal ganglia. This brain region has been targeted for electrical stimulation due to its known role in the control of conscious and proprioceptive movements [

168]. So far, DBS of the GP has shown beneficial effects on PD patients, raising from 28 to 64% the time with good mobility (without the presence of dyskinesia) [

129]. Its beneficial effects in PD models have been linked to its effects on striatal DA [

169]. Clinical trials on HD patients are also using GP DBS, with encouraging improvements in some motor symptoms present on the course of the disease [clinical trial NCT02535884]. HD patients with late onset also benefit from pallidal DBS, decreasing the choreatic symptoms [

59,

170,

171].

2.2.7. Additional Brain Areas

The dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN), the lateral hypothalamus (LH), the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and the spinal cord (SC) have also been considered for brain stimulation when treating some neurodegenerative disorders as well as drug addiction.

The SC serves as a connection area, whose primary role is to send motor and sensory information between the brain and the rest of the body [

172]. The SC has been the target of treatment for chronic pain for decades. However, in preclinical studies, SC-DBS improved motor deficits [

173,

174]. Stimulation of the SC in PD patients with postural instability and gait disorders that have resistance to more standardized treatments, have shown positive results and a reduction of the symptoms [

175,

176]. Moreover, if the stimulation of the SC is maintained, there is an improvement in the Unified Parkinson Disease Rated Scale (UPDRS-III) motor scale scores, a reduction of gait episodes and self-reported quality of life.

DArgic fibers projecting to the motor cortex originates from the VTA and are mostly directed to the deep layer of the cortex. The VTA contains mesolimbic and mesocortical DArgic neurons. Therefore, the VTA is really important for its involvement in the reward system, which could be compromised in neurological diseases as well as some psychiatric conditions such as addiction. Abnormalities in the function of VTA DA neurons and the targets they influence are implicated in several prominent neuropsychiatric disorders including addiction [

177]. In stimulation studies involving the VTA, the stimulation typically does not target the VTA directly; instead, researchers study VTA activation resulting from connections with other areas. However, the VTA has shown to be a relevant target area for stimulation in anxiety and depression studies [

178]. Due to the main projections of the VTA, such as the Nacb, the VTA has also been stimulated to check its effects on disorders such addiction [

179]. DBS stimulation of the VTA induced a persistent suppression of Nacb tonic DA levels [

180]. Its stimulation was able to suppress reinstatement and seeking behavior caused by amphetamine [

179]. The stimulation of the LH, brain area involved on the DArgic pathway relevant for reward processing, facilitated extinction of morphine place preference and disrupted drug priming- and stress-induced renewal of morphine place preference [

181].

To bring this section to a close, it is essential to recognize the valuable insights gained from these stimulation studies. Nevertheless, significant work remains to accurately target the mechanisms underlying the adverse symptoms associated with neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders. The promising results offer hope, particularly for patients who do not respond adequately to less invasive pharmacological treatments.

3. Innovations on Nanomedicine to Target Aberrant Signaling in Neurodegeneration: Focus on the Dopaminergic Pathway

As reviewed in section 1, current technologies are offering exciting new approaches to treat a broad spectrum of diseases by targeting various brain regions and, consequently, the associated neurotransmitter systems. However, the use of non-invasive ways to treat neurodegenerative disorders remains elusive.

Section 2 emphasized the current data on stimulation related to neurodegeneration, which mostly is limited to the use of DBS. Despite advancements, challenges such as device-related complications and medication side effects persist, indicating that significant progress is still required. The pace of knowledge advancement is not as rapid as desired.

When we first heard about Neuralink, people reported being the start of a new era. Are we in an evolving landscape of innovation or science fiction? Neuralink has placed brain stimulation on the top of the iceberg and has become the point of reference for most research laboratories. We have made significant strides in neuroscience; however, the knowledge about the brain is far from complete. We presume deep knowledge of pathological mechanisms mediating disorders such as AML, PD and AD. However we still face several complex and interrelated challenges due to the multifaceted interactions between brain areas as well as between neurotransmitter systems.

Due to our current incomplete understanding of the mechanisms underlying those disorders, the challenge in diagnosis and early detection as well as in drug development keep clinical trials far away from a “magic” treatment. But, there is still great support to research groups that continue to fascinate the audience with promising results and additional innovative approaches.

In the early 2000s, the concept of nanomedicine began to gain significant attention [

182]. The use of nanoparticles has, since then, started exploring their use for medical applications, including but not limited to targeted drug delivery [

183].

3.1. Nanotechnology Highlights

Thanks to nanoformulation and conjugation, we have gained enhanced drug solubility and bioavailability due to the nanoparticle ability to encapsulate hydrophobic drugs. This achievement has therefore ensured a higher amount of the pharmacological agent to reach the brain. Most nanoparticles are designed to overcome the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) penetration. Additionally, as previously mentioned, the functionalization of nanoparticles with targeting ligands (that can include specific peptides or even antibodies with high affinity), could reduce off-target effects, minimizing unwanted side effects. Importantly, nanoparticles can also be developed to provide sustained therapeutic effects, therefore reducing the need of repeated dosing frequently. Several laboratories have focused on the use of temperature-responsive nanoparticles (for example hydrogel nanoparticles) that allow the release of the conjugated compounds in response to temperature changes, therefore, allowing on demand drug release in the brain [

184].

3.2. Nanotechnology for DArgic Target in Neurodegeneration and Addiction

Main aspects of innovative nanomaterials are their surface properties and surface functionality, which play relevant roles in the operational characteristics of such materials. A new era is now being exploited focusing on such nanoparticle characteristics.

There have been few efforts to target the DArgic system with the use of nanoparticles. Due to DA relevance in several disorders (as previously discussed) Kook et al. [

185] designed magnetic nanoparticles to specifically target DA molecules, and thus use them to quantify DA physiological levels, highlighting its possible role as indicator for early disease diagnosis. As mentioned, nanotechnology is evolving and allows the surface modification of the pertinent nanoparticles for specific conjugation and, therefore, in this case, DA target. Recent efforts to target the DA system with magnetic nanoparticles also showed the potency of nanoparticle surface modification by DA derivatives in-situ polymerization to produce bioactive nanocomposites [

186]. These authors highlight the reduced spontaneous release of the DA derivatives from the nanoparticles due to the high stability of the synthesized coatings. Mayeen et al., [

187] produced nanocomposites functionalized with DA, which enhanced the electrical and magnetoelectric properties of their BaTiO3 nanoparticles.

On the other hand, a growing body of evidence explored the use of nanoparticles to directly target the DArgic system via nano conjugation with specific pharmacological agents, with encouraging results. For example, nanoparticles directly conjugated with DA [

188] or conjugated with L-Dopa to enhance its delivery for the treatment of PD, showed promising results in improving symptoms in PD models. Those studies highlight the increased delivery and release of the DA precursor using polymeric nano delivery systems [

189]. These investigations reveal better therapeutic efficacy and extended L-Dopa release [

190,

191]. Several types of nanoparticles have also been used to increase DA levels in AD models [

192,

193]. Other manipulations using nanoparticles, for example, mesoporous silica nanoparticles, have been used to convert fibroblasts into DArgic neuron-like cells, which could be a relevant approach for neurodegenerative diseases including ALS [

194].

However, current knowledge does not limit the use of nanoparticles for the aforementioned disorders. For example, while the application of nanoparticles specifically for addiction treatment is still emerging, their potential to deliver precise doses of DA-regulating agents could be significant for future therapies aimed at modulating DA levels to treat addiction. Because some addictive drugs such as cocaine and amphetamine exerts their effects via direct impact on DA transporters (DAT), new nanomaterials aimed to target DAT are being considered.

Does nanomedicine go in parallel to the brain stimulation approach? Could we benefit from both treatment options? As reviewed in

Section 2, integrating nanomedicine with targeted testing in specific brain regions known to mediate motor, cognitive, and other critical processes altered in neurodegenerative disorders presents a promising approach.

4. Introduction of Upcoming Technologies for Brain Stimulation: Magnetoelectric Nanoparticles, the Missing Link between Nanoformulation and Stimulation Approaches

4.1. Current Limitations

Even though such innovative nanoparticle approaches discussed in section 3 are encouraging and are providing new ways to target neurodegenerative disorders, they present relevant limitations that require attention. Briefly, it is important to note that crossing the BBB continues to be a handicap on drug efficacy, even with the use of some innovative nanoparticles. Additionally, due to the complexity and heterogeneity of the brain, achieving precise delivery into brain areas of interest (due to their individual relevance in the aforementioned disorders previously discussed) is challenging with current nanoparticles. Also, controlling the adequate rate of release represents a major issue in this field. As with other biochemical compounds it is always a concern for long-term biocompatibility due to the possibility of potential toxicity at long term. Even though we recognize the tremendous potential of current nanoparticles in development, we are still far from the “divine” treatment. All these aspects could limit the clinical use of currently available nanomaterials [

195,

196].

Revising the previously discussed stimulation approaches (section 1-2 above), we face the same situation, we have promising results but are surrounded by numerous limitations. We would like to highlight that we encounter a tremendous challenge, the full knowledge of the underlying mechanisms by which the “electric” brain works, and therefore, the mechanism by which all stimulation approaches can affect those neural circuits. Let's briefly summarize relevant barriers of current stimulation devices. In most of the stimulation cases introduced across this review the invasiveness that they represent limits their use to severe cases where the anticipated benefits could outweigh the risks of such intervention. The need for surgical implantations involve several possible complications (infections, hardware-related complications, bleeding, etc), which additionally brings the difficulty for accurate targeting and, therefore, precise stimulation of the brain area of interest. Due to the side effects present in the patients, short-term as well as long-term, they are still not totally described. Additionally, some devices that use magnetic induction or optoelectronic signaling have strong limitations related to the tissue penetration [

197,

198,

199]. This incomplete knowledge calls for additional work focused on how the brain works and how we can improve its functioning via neural stimulation. Due to the variability observed in response to stimulation interventions, nowadays it is still really complicated to confirm that a patient would benefit from such treatment. And, finally, it is extremely relevant to mention that the access to these technologies remain restricted in so many countries due to the high cost derived from expenses of the surgical procedure itself between other costs.

4.2. The Progress and Evolution of the New Era: Magnetoelectric Nanoparticles (MENPs)

Given our current understanding and comprehensive grasp of the strengths and constraints inherent in existing treatment modalities, we are strategically positioned to progress and innovate, leveraging novel tools to effectively surmount prevailing challenges.

In pursuit of cutting-edge technologies to surpass current scientific limitations, over the past decade, Dr. Khizroev pioneered the development of magnetoelectric nanoparticles (MENPs), often referred to as "magic tools," originally outlined in a computational study [

200]. Following that initial study, a decade of research supports the innovative use of MENPs for their application in medical science. MENPs are recognized as a non-invasive alternative to present treatment approaches with a potential for widespread therapeutic use in a variety of psychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases [

201]. There are currently numerous laboratories engaged in this advanced nanotechnology worldwide. From our knowledge, few research groups located across the world (Spain, Germany, Switzerland, Russia, Korea, China, USA) are now optimizing the composition and use of MENPs for targeting the brain. Are MENPs the “magic” bullet we have been looking for? Achieving targeted drug release upon request, coupled with precise wireless onsite stimulation for on-demand control, represents the envisioned solution.

Briefly, MENPs could overcome most of the limitations of current nanotechnology as well as stimulation approaches. MENPs can generate electric fields through the application of magnetic fields, allowing their use as non-invasive devices for biomedical applications that can include brain precise stimulation upon request as well as targeted drug delivery as desired [

202]. The detailed characteristics of MENPs and their potential in medicine has recently been reviewed [

201,

202,

203,

204]. Between relevant aspects to overcome, MENPs would not produce heat generated by other devices, thus eliminating high temperatures as a source of off-target neuromodulation [

205,

206].

During the last few years, we are receiving strong evidence supporting the ability of MENPs to induce neuronal response. Under physiological conditions a neuron’s maximum firing rate is typically 500 Hz [

207]. In response to wireless magnetic stimulation, MENPs increase neuronal calcium channel response, in vitro and in vivo

[205,208,209,210] comparable to conventional wired DBS. The use of several frequencies, below the approved conventional stimulation parameters used in clinical trials with DBS (<500 Hz), at frequencies that vary between 10-20 Hz [

208], 100 Hz [

210] to 140 Hz [

205,

206], have shown to stimulate the neurons, non-invasively and without inducing neuronal damage or inflammation.

4.3. Magnetoelectric Nanoparticles (MENPs) for DArgic Target

Ongoing research has shown the ability to locate MENPs in the brain. Crossing the BBB with MENPs was initially achieved by exposing the rodents to a magnetic field after intravenous MENPs administration [

211]. Later, Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was used to achieve the effective delivery of intravenously administered MENPs to the brain in baboons [

212]. It was the first time that behavioral parameters were considered when studying MENPs effects in vivo. More recently, we showed MENPs direct capability to reach the brain via intranasal administration [

213]. With no doubt, at doses tested, MENPs seem to be safe and non-toxic when located in the brain [

205,

208,

213,

214,

215].

However, how MENPs can directly affect several underlying pathways controlling a patient's behavior is still at initial stages of study. We previously discussed the relevant role of specific brain areas on behavioral control and, precisely, the DArgic paper on that modulation (see

Section 2 above). It was not until 2021 when Kozielski´s group [

205,

206] targeted a specific brain area (STN) with MENPs. Importantly, those studies showed that bilateral STN injection of MENPs do not induce detrimental effects on rodents' behavior. As previously discussed, STN is an important brain area regarding DArgic implication in neurodegenerative disorders such as PD and HD, that involve motor deterioration. Therefore, it was not surprising that magnetic stimulation of STN, at frequencies shown to induce neuronal modulation (140-280 Hz), induced locomotor activity in MENPs (average size 250 nm)-treated animals [

205,

206]. Additional work from our group (in preparation) also showed the ability of MENPs, when directly administered in motor areas, to induce behavioral activation in rats. We show the ability of MENPs to induce motor response in a msec range after stimulation. Additionally, we demonstrate micron spatial resolution of wirelessly induced MENPs local stimulation. Therefore, even though current studies are limited, the impact of MENPs stimulation on motor control is irrefutable, and its role on the DArgic system seems unquestionable. Alosaimi et al., [

206] confirmed that stimulation of STN using MENPs induced additional changes in neuronal activity on projection areas such as motor cortex (MC) and the paraventricular region of the thalamus (PV-thalamus). They confirmed that STN stimulation modulated the neuronal activity of the mesolimbic VTA DArgic neurons. More precisely, TH cells activity was changed (but not cell count) after MENPs stimulation [

206]. Previously, MENPs magnetic stimulation of the STN also led to higher neuronal activity in projection areas from the cortico-basal ganglia-thalamocortical circuit, including the motor cortex and thalamus [

205].

There are significant points to discuss regarding these recent studies: MENPs used by the Kozielsi did not migrate from the site of administration for up to 7 weeks post-injection. It's challenging to determine whether this is advantageous or disadvantageous. On one hand, it could be considered beneficial as it allows for repeated stimulation of MENPs without the need of more invasive administration. In this respect, MENPs would closely mimic the function of DBS (device-related), which involves an “initial” administration and positioning and long-term sustained use. Conversely, previous studies using intravenous and intranasal administration showed that MENPs dispersed and were eliminated from the system within days to weeks. Additionally, it is important to note that the nano composition of MENPs can vary, leading to slight differences between laboratories.

Figure 1 summarizes the potential of MENPs for the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders based on current knowledge of these innovative nanoparticles.

5. Conclusions: Peculiarity of the DArgic System and Its Target Using MENPs

DA is unequivocally a critical target for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. How can we target a neurotransmitter that is everywhere and has an essential role in brain functioning avoiding undesired effects? The nature of DA itself represents a challenge. With its main 5 pathways, each of them with different roles in human behavior, to target on demand DA only present in a specific pathway, in a specific brain area, is difficult obstacle to overcome. DArgic neurons respond to electrical stimulation (see previous section 2). We previously revised how stimulation of different specific brain areas could differ in their relevance to restore brain circuitry in neurodegenerative disorders, with some emphasis on DA modulation.

DA depletion or aberrant functioning plays a relevant role in neurodegenerative, as well as several psychiatric, disorders. DA dysregulation and imbalance in neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders can be mediated by DAT dysregulation. DAT is a vital mediator controlling DA levels and its dysfunction has closely been linked to disease. Preserving DArgic neurons and their proper regulation is crucial to prevent disease progression, involving motor and non-motor (cognitive) symptomatology.

Therefore, MENPs ability to be guided to specific brain areas where DA has been described to play an important role, allows for targeted therapy in a way not previously possible. MENPs ability to stimulate neurons and their direct role on neurotransmission has just started to be tested [

206]. Because MENPs have shown their ability to be conjugated with specific antibodies or pharmacological compounds [

217,

218,

219,

220], the hypothesis of MENPs for specific DA target is not questionable. The precision previously described about these nanoparticles allows for designing MENPs to specifically deliver agents with neuroprotective and neurorestorative characteristics directly to neurons where, for example, DA receptors are located. MENPs could be conjugated with agents like L-DOPA or DAT inhibitors to prolong DA action to, for example, compensate DA loss in PD. This approach at early stages of neurodegeneration could, per se, reverse the progression of aggressive disorders as previously introduced. Current funded projects are evaluating MENPs´ role in rodent models of PD, therefore, it is just a matter of time to give additional support to the hypothesis mentioned.

Nanometer-size neural stimulators can be seamlessly and fully implanted into specific brain areas through stereotaxic injections, therefore leveraging the benefits of nanomaterials with minimal invasiveness [

210]. To conclude, MENPs represent an innovative approach far away from current treatment interventions. MENPs can be used as nanocarriers as well as stimulation devices. As seen with DBS, where medication in addition to DBS showed additive effects in improving motor performance in PD [

221], MENPs beneficial effects are promising. Previous and ongoing studies confirm the reliable biocompatibility, biosafety and feasibility of MENPs. Therefore, as recently discussed, a new era is ensured where side effects of current pharmacological (including nanomedicine) and stimulation approaches could be minimized with less invasive proposals. With the increasing amount of data regarding the brain heterogeneity and its functions, the close future is encouraging. We emphasize individualized treatment, with in vivo real time MRI for MENPs localization and, therefore, non-invasive on demand stimulation, with, if desired, additional drug release on the selected brain area.

6. Materials and Methods

The current review has been prepared using Pubmed, Embase, and Scopus databases. We searched for the following keywords: neurodegeneration, dopamine, Alzheimer, Parkinson, Huntington, sclerosis, addiction, nanoparticles, magnetoelectric nanoparticles, neuromodulation, subthalamic nucleus, globus pallidus, striatum, pedunculopontine nucleus, cortex, substantia nigra, deep brain stimulation, transcranial magnetic stimulation, brain-computer-interfaces.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization MP; methodology, SG,AM,AMM,NA,IGJ and MP; resources, SG,AM,AMM,NA,IGJ and MP; data curation, MP; writing—original draft preparation, SG,AM,AMM,NA,IGJ and MP.; writing—review and editing, MP.; supervision, MP.; project administration, MP.; funding acquisition, MP. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research was funded by Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, grant number RYC2022-035438-I.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no acknowledgments to make.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wu, C.; Yang, L.; Feng, S.; Zhu, L.; Yang, L.; Liu, T.C.Y.; Duan, R. Therapeutic non-invasive brain treatments in Alzheimer’s disease: Recent advances and challenges. Inflamm. Regen. 2022, 42, 31.

- Van Wamelen, D.J.; Rukavina, K.; Podlewska, A.M.; Chaudhuri, K.R. Advances in the pharmacological and non-pharmacological management of non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease: an update since 2017. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2023, 21, 1786.

- Frey, J.; Cagle, J.; Johnson, K.A.; Wong, J.K.; Hilliard, J.D.; Butson, C.R.; Okun, M.S.; de Hemptinne, C. Past, present, and future of deep brain stimulation: Hardware, software, imaging, physiology and novel approaches. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Fariba, K.A. Deep Brain stimulation. StatPearls [Internet]. 2023, July 24. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557847/.

- Deep Brain stimulation. AANS. (n.d.). https://www.aans.org/en/Patients/Neurosurgical-Conditions-and-Treatments/Deep-Brain-Stimulation.

- Saini, R.; Chail, A.; Bhat, P.; Srivastava, K.; Chauhan, V. Transcranial magnetic stimulation: A review of its evolution and current applications. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2018, 27, 172. [CrossRef]

- Woods, A.J.; Antal, A.; Bikson, M.; Boggio, P.S.; Brunoni, A.R.; Celnik, P.; Cohen, L.G.; Fregni, F.; Herrmann, C.S.; Kappenman, E.S.; Knotkova, H.; Liebetanz, D.; Miniussi, C.; Miranda, P.C.; Paulus, W.; Priori, A.; Reato, D.; Stagg, C.; Wenderoth, N.; Nitsche, M.A. A technical guide to tDCS, and related non-invasive brain stimulation tools. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2016, 127, 1031-1048. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chase, H.W.; Boudewyn, M.A.; Carter, C.S.; Phillips, M.L. Transcranial direct current stimulation: a roadmap for research, from mechanism of action to clinical implementation. Mol. Psychiatry. 2020, 25, 397-407. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Beisteiner, R.; Lozano, A.M. Transcranial ultrasound innovations ready for broad clinical application. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 2002026.

- Beisteiner, R.; Hallett, M.; Lozano, A.M. Ultrasound neuromodulation as a new brain therapy. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2205634.

- Miladinovic, A.; Ajcevic, M.; Busan, P.; Jarmolowska, J.; Silveri, G.; Deodato, M.; Mezzarobba, S.; Battaglini, P.P.; Accardo, A. Evaluation of Motor Imagery-Based BCI methods in neurorehabilitation of Parkinson's Disease patients. Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2020, 2020, 3058-3061. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arlotti, M.; Colombo, M.; Bonfanti, A.; Mandat, T.; Lanotte, M.M.; Pirola, E.; Borellini, L.; Rampini, P.; Eleopra, R.; Rinaldo, S.; Romito, L.; Janssen, M.L.F.; Priori, A.; Marceglia, S. A New Implantable Closed-Loop Clinical Neural Interface: First Application in Parkinson's Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 763235. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pirasteh, A.; Shamseini Ghiyasvand, M.; Pouladian, M. EEG-based brain-computer interface methods with the aim of rehabilitating advanced stage ALS patients. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2024, 24, 1-11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolpaw, J.R. Brain–computer interfaces as new brain output pathways. J. Physiol. 2007, 579, 613-619.

- Vidal, J.J. Toward direct brain-computer communication. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Bioeng. 1973, 2, 157-80. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, M.J.; Lin, D.J.; Hochberg, L.R. Brain-Computer Interfaces in Neurorecovery and Neurorehabilitation. Semin. Neurol. 2021, 41, 206-216. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Musk, E.; Neuralink. An Integrated Brain-Machine Interface Platform With Thousands of Channels. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e16194. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Original records of each monkey used by Neuralink at UC Davis. Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine. (n.d.). https://www.pcrm.org/ethical-science/animals-in-medical-research/original-records-neuralink.

- Ryan, H. Elon Musk’s Neuralink confirms monkeys died in project, denies animal cruelty claims. CNN Bus. 2022, February 17. https://edition.cnn.com/2022/02/17/business/elon-musk-neuralink-animal-cruelty-intl-scli/index.html.

- Winkler, R. Elon Musk's Neuralink Gets FDA Green Light for Second Patient, as First Describes His Emotional Journey. Wall Street J. 2024, May 20.

- Neuralink Corp. Precise Robotically IMplanted Brain-Computer InterfacE (PRIME). Clin. Trials.gov (n.d.). https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06429735?term=neuralink&rank=1.

- Zhang, Z.; Dai, J. Fully implantable wireless brain-computer interface for humans: Advancing toward the future. Innov. 2024, 5, 100595. [CrossRef]

- John, S.E.; Grayden, D.B.; Yanagisawa, T. The future potential of the Stentrode. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2019, 16, 841-843.

- Aguilar-Pérez, M.; Martinez-Moreno, R.; Kurre, W.; et al. Endovascular treatment of idiopathic intracranial hypertension: retrospective analysis of immediate and long-patients. Neuroradiology 2017, 59, 277-287. [CrossRef]

- Vansteensel, M.J.; Klein, E.; van Thiel, G.; Gaytant, M.; Simmons, Z.; Wolpaw, J.R.; et al. Towards clinical application of implantable brain-computer interfaces for people with late-stage ALS: medical and ethical considerations. J. Neurol. 2023, 270, 1323-1336.

- Pirasteh, A.; Shamseini Ghiyasvand, M.; Pouladian, M. EEG-based brain-computer interface methods with the aim of rehabilitating advanced stage ALS patients. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2024, 24, 1-11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tayebi, H.; Azadnajafabad, S.; Maroufi, S.F.; Pour-Rashidi, A.; Khorasanizadeh, M.; Faramarzi, S.; Slavin, K.V. Applications of brain-computer interfaces in neurodegenerative diseases. Neurosurg. Rev. 2023, 46, 131.

- Fiani, B.; Reardon, T.; Ayres, B.; Cline, D.; Sitto, S.R.; Reardon, T.K.; et al. An examination of prospective uses and future directions of Neuralink: the brain-machine interface. Cureus 2021, 13, e13836.

- Sonmez, A.I.; Camsari, D.D.; Nandakumar, A.L.; Voort, J.L.V.; Kung, S.; Lewis, C.P.; Croarkin, P.E. Accelerated TMS for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 273, 770-781.

- Maia, A.; Almeida, S.; Cotovio, G.; Rodrigues da Silva, D.; Viana, F.F.; Grácio, J.; Oliveira-Maia, A.J. Symptom provocation for treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder using transcranial magnetic stimulation: A step-by-step guide for professional training. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 924370. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reyes-Leiva, D.; Dols-Icardo, O.; Sirisi, S.; Cortés-Vicente, E.; Turon-Sans, J.; de Luna, N.; Blesa, R.; Belbin, O.; Montal, V.; Alcolea, D.; Fortea, J.; Lleó, A.; Rojas-García, R.; Illán-Gala, I. Pathophysiological Underpinnings of Extra-Motor Neurodegeneration in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: New Insights From Biomarker Studies. Front. Neurol. 2022, 12, 750543. [CrossRef]

- Vucic, S.; Ziemann, U.; Eisen, A.; Hallett, M.; Kiernan, M.C. Transcranial magnetic stimulation and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: pathophysiological insights. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2013, 84, 1161-1170.

- Batra, G.; Jain, M.; Singh, R.S.; Sharma, A.R.; Singh, A.; Prakash, A.; Medhi, B. Novel therapeutic targets for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2019, 51, 418-425.

- Tzeplaeff, L.; Wilfling, S.; Requardt, M.V.; Herdick, M. Current state and future directions in the therapy of ALS. Cells 2023, 12, 1523.

- Hoogendam, J.M.; Ramakers, G.M.; Di Lazzaro, V. Physiology of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the human brain. Brain Stimul. 2010, 3, 95-118. [CrossRef]

- Blasco, H.; Mavel, S.; Corcia, P.; Gordon, P.H. The glutamate hypothesis in ALS: pathophysiology and drug development. Curr. Med. Chem. 2014, 21, 3551-3575. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, H.; Snow, B.J.; Bhatt, M.H.; Peppard, R.F.; Eisen, A.; Calne, D.B. Evidence for a dopaminergic deficiency in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis on positron emission scanning. Lancet 1993, 342, 1016-1018.

- Hardiman, O.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Chio, A.; et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2017, 3, 17071. [CrossRef]

- Brunet, A.; Stuart-Lopez, G.; Burg, T.; Scekic-Zahirovic, J.; Rouaux, C. Cortical Circuit Dysfunction as a Potential Driver of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 363. [CrossRef]

- Vogels, O.J.; Veltman, J.; Oyen, W.J.; Horstink, M.W. Decreased striatal dopamine D2 receptor binding in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and multiple system atrophy (MSA): D2 receptor down-regulation versus striatal cell degeneration. J. Neurol. Sci. 2000, 180, 62-65. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagata, E.; Ogino, M.; Iwamoto, K.; Kitagawa, Y.; Iwasaki, Y.; Yoshii, F.; Ikeda, J.E.; ALS Consortium Investigators. Bromocriptine Mesylate Attenuates Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Phase 2a, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Research in Japanese Patients. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149509; Erratum in: PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152845. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huang, X.; Roet, K.C.D.; Zhang, L.; Brault, A.; Berg, A.P.; Jefferson, A.B.; Klug-McLeod, J.; Leach, K.L.; Vincent, F.; Yang, H.; Coyle, A.J.; Jones, L.H.; Frost, D.; Wiskow, O.; Chen, K.; Maeda, R.; Grantham, A.; Dornon, M.K.; Klim, J.R.; Siekmann, M.T.; Zhao, D.; Lee, S.; Eggan, K.; Woolf, C.J. Human amyotrophic lateral sclerosis excitability phenotype screen: Target discovery and validation. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109224. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tanaka, K.; Kanno, T.; Yanagisawa, Y.; Yasutake, K.; Hadano, S.; Yoshii, F.; Ikeda, J.E. Bromocriptine methylate suppresses glial inflammation and moderates disease progression in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Exp. Neurol. 2011, 232, 41-52. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Lorenzo, F.; Lüningschrör, P.; Nam, J.; Beckett, L.; Pilotto, F.; Galli, E.; Lindholm, P.; Rüdt von Collenberg, C.; Mungwa, S.T.; Jablonka, S.; Kauder, J.; Thau-Habermann, N.; Petri, S.; Lindholm, D.; Saxena, S.; Sendtner, M.; Saarma, M.; Voutilainen, M.H. CDNF rescues motor neurons in models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis by targeting endoplasmic reticulum stress. Brain 2023, 146, 3783-3799. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cleveland, D.W.; Rothstein, J.D. From Charcot to Lou Gehrig: deciphering selective motor neuron death in ALS. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001, 2, 806-819.

- Roos, R.A. Huntington's disease: a clinical review. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2010, 5, 40. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cepeda, C.; Murphy, K.P.; Parent, M.; Levine, M.S. The role of dopamine in Huntington's disease. Prog. Brain Res. 2014, 211, 235-254. [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Lalonde, K.; Truesdell, A.; Gomes Welter, P.; Brocardo, P.S.; Rosenstock, T.R.; Gil-Mohapel, J. New avenues for the treatment of Huntington’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8363.

- André, V.M.; Cepeda, C.; Levine, M.S. Dopamine and glutamate in Huntington's disease: A balancing act. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2010, 16, 163-178. [CrossRef]

- Koch, E.T.; Raymond, L.A. Dysfunctional striatal dopamine signaling in Huntington's disease. J. Neurores. 2019, 97, 1636-1654. [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.S.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Bezprozvanny, I. Dopaminergic signaling and striatal neurodegeneration in Huntington's disease. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 7899-7910. [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.L.; Mason, S.L.; Vallin, B.; Barker, R.A. Reduced expression of dopamine D2 receptors on astrocytes in R6/1 HD mice and HD post-mortem tissue. Neurosci. Lett. 2022, 767, 136289.

- Squitieri, F.; Di Pardo, A.; Favellato, M.; Amico, E.; Maglione, V.; Frati, L. Pridopidine, a dopamine stabilizer, improves motor performance and shows neuroprotective effects in Huntington disease R6/2 mouse model. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2015, 19, 2540-2548. [CrossRef]

- Schwab, L.C.; Garas, S.N.; Drouin-Ouellet, J.; Mason, S.L.; Stott, S.R.; Barker, R.A. Dopamine and Huntington’s disease. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2015, 15, 445-458. [CrossRef]

- Jabłońska, M.; Grzelakowska, K.; Wiśniewski, B.; Mazur, E.; Leis, K.; Gałązka, P. Pridopidine in the treatment of Huntington’s disease. Rev. Neurosci. 2020, 31, 441-451. [CrossRef]

- Grachev, I.D.; Meyer, P.M.; Becker, G.A.; et al. Sigma-1 and dopamine D2/D3 receptor occupancy of pridopidine in healthy volunteers and patients with Huntington disease: a [18F] fluspidine and [18F] fallypride PET study. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2021, 48, 1103-1115. [CrossRef]

- Jankovic, J.; Clarence-Smith, K. Tetrabenazine therapy of dystonia, chorea, tics, and other dyskinesias and disorders of movement. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1993, 54 (Suppl), 25-28.

- Cepeda, C.; Levine, M.S. Synaptic Dysfunction in Huntington's Disease: Lessons from Genetic Animal Models. Neuroscientist 2022, 28, 20-40. [CrossRef]

- Bonomo, R.; Elia, A.E.; Bonomo, G.; Romito, L.M.; Mariotti, C.; Devigili, G.; Cilia, R.; Giossi, R.; Eleopra, R. Deep brain stimulation in Huntington's disease: a literature review. Neurol. Sci. 2021, 42, 4447-4457. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Xu, Y.Y.; Gao, Y.; Li, J.M.; Liu, X.W.; Wang, M.Q.; Deng, H.; Xiao, L.L.; Ren, H.B.; Xiong, B.T.; Pan, W.; Zhou, X.W.; Wang, W. Deep brain stimulation for chorea-acanthocytosis: a systematic review. Neurosurg. Rev. 2022, 45, 1861-1871. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, X.; Kaminga, A.C.; Wen, S.W.; Wu, X.; Acheampong, K.; Liu, A. Dopamine and Dopamine Receptors in Alzheimer's Disease: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 175.

- Ferretti, M.T.; Iulita, M.F.; Cavedo, E.; Chiesa, P.A.; Schumacher, D.A., et al. Sex Differences in Alzheimer Disease - the Gateway to Precision Medicine. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2018, 14, 457–469.

- Tiernan, C.T.; Ginsberg, S.D.; He, B.; Ward, S.M.; Guillozet-Bongaarts, A.L., et al. Pretangle Pathology within Cholinergic Nucleus Basalis Neurons Coincides with Neurotrophic and Neurotransmitter Receptor Gene Dysregulation during the Progression of Alzheimer's Disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2018, 117, 125–136.

- Koch, G.; Di Lorenzo, F.; Bonnì, S.; Giacobbe, V.; Bozzali, M., et al. Dopaminergic Modulation of Cortical Plasticity in Alzheimer's Disease Patients. Neuropsychopharmacology 2014, 39, 2654–2661.

- Martorana, A.; Mori, F.; Esposito, Z.; Kusayanagi, H.; Monteleone, F., et al. Dopamine Modulates Cholinergic Cortical Excitability in Alzheimer's Disease Patients. Neuropsychopharmacology 2009, 34, 2323–2328.

- Drayton, S.J.; Davies, K.; Steinberg, M.; Leroi, I.; Rosenblatt, A., et al. Amantadine for Executive Dysfunction Syndrome in Patients with Dementia. Psychosomatics 2004, 45, 205–209.

- Herrmann, N.; Rothenburg, L.S.; Black, S.E.; Ryan, M.; Liu, B.A., et al. Methylphenidate for the Treatment of Apathy in Alzheimer Disease: Prediction of Response Using Dextroamphetamine Challenge. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2008, 28, 296–301.

- Mintzer, J.; Greenspan, A.; Caers, I.; Van Hove, I.; Kushner, S., et al. Risperidone in the Treatment of Psychosis of Alzheimer Disease: Results from a Prospective Clinical Trial. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2006, 14, 280–291.

- Lanctôt, K.L.; Herrmann, N.; Black, S.E.; Ryan, M.; Rothenburg, L.S., et al. Apathy Associated with Alzheimer Disease: Use of Dextroamphetamine Challenge. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2008, 16, 551–557.

- Liang, Y.Q.; Tang, X.C. Comparative Studies of Huperzine A, Donepezil, and Rivastigmine on Brain Acetylcholine, Dopamine, Norepinephrine, and 5-Hydroxytryptamine Levels in Freely-Moving Rats. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2006, 27, 1127–1136.

- Schilström, B.; Ivanov, V.; Wiker, C.; et al. Galantamine Enhances Dopaminergic Neurotransmission In Vivo Via Allosteric Potentiation of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Neuropsychopharmacol 2007, 32, 43–53.