Submitted:

01 July 2024

Posted:

02 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research

2.2. Customized Design

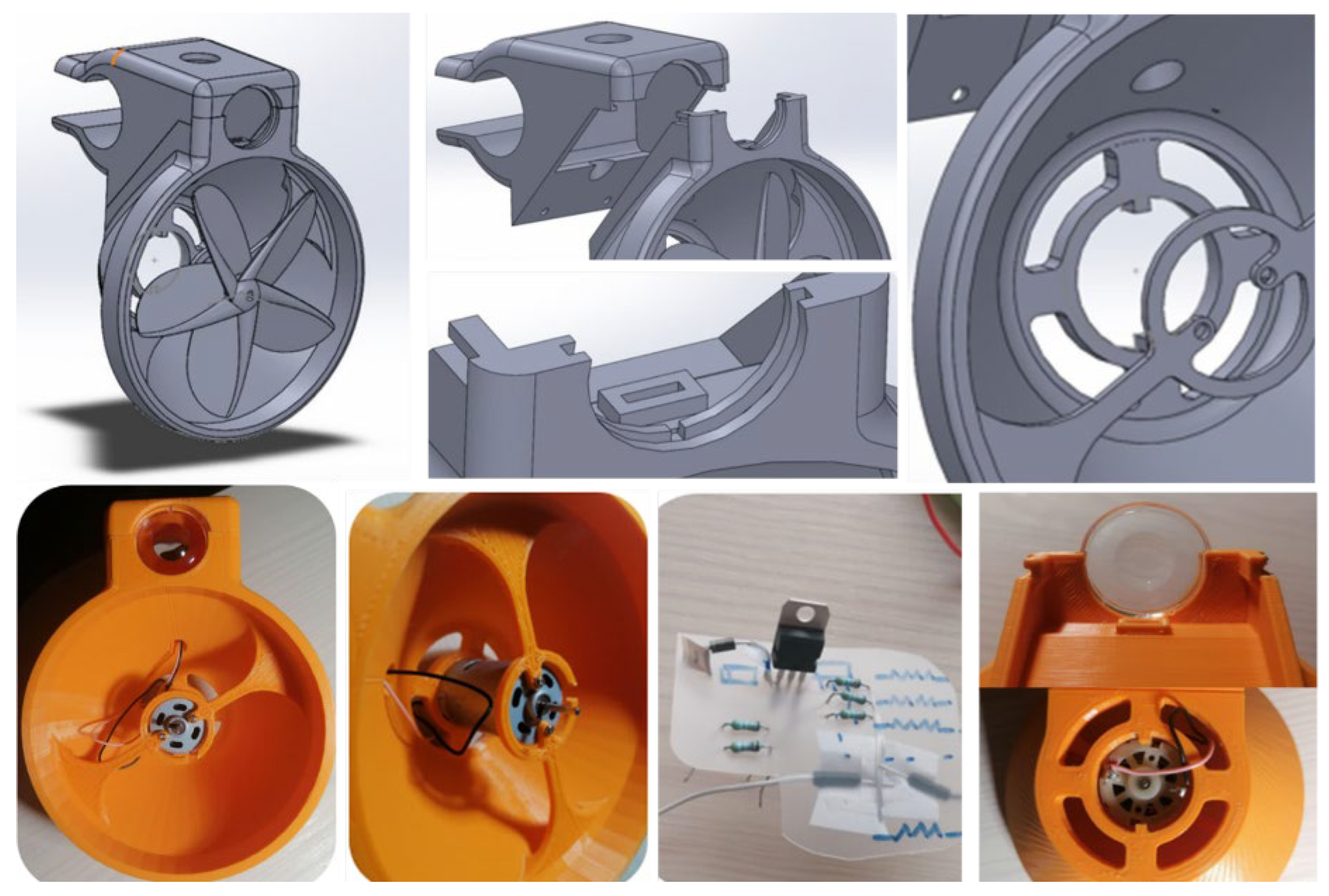

2.3. Prototyping

2.4. Manufacturing

2.5. Validation

3. Results

3.1. Research

3.1.1. The Bicycle Flashlight Market

3.1.2. Understanding Microturbines Operation and Performance

3.1.3. Bioinspired Design

3.1.4. Design Brief

3.2. Custom-Made Design

3.3. Prototyping

3.3.1. Conceptual Design Review

3.4. Experimentation and Final Validation

3.5. Manufacturing and Home Fabrication

3.5.1. Final Assembly. Adjustment and Validation

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Whitesides, G.M. Bioinspiration: Something for Everyone. Interface Focus 2015, 5, 20150031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, K.; Moreno, D.; Yang, M.; Wood, K.L. Bio-Inspired Design: An Overview Investigating Open Questions From the Broader Field of Design-by-Analogy. Journal of Mechanical Design 2014, 136, 111102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanieck, K.; Fayemi, P.E.; Maranzana, N.; Zollfrank, C.; Jacobs, S. Biomimetics and Its Tools. Bioinspired, Biomimetic and Nanobiomaterials 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzer, G.; Dean, P.; Jurgenson, N. The Coming of Age of the Prosumer. American Behavioral Scientist 2012, 56, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiş Erümit, S.; Karakuş Yılmaz, T. Gamification Design in Education: What Might Give a Sense of Play and Learning? Technology, Knowledge and Learning 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millard, J.; Sorivelle, M.N.; Katsikis, O.K.; Unterfrauner, E.; Voigt, C. The Maker Movement in Europe: Empirical and Theoretical Insights into Sustainability. In Proceedings of the EPiC Series in Computing. ICT4S2018. 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technology for Sustainability; Penzenstadler, B., Easterbrook, S., Venters, C., Ahmed, S.I., Eds.; Epic Computing: Toronto, May 14, 2018; pp. 227–210. [Google Scholar]

- López-Forniés, I.; Asión-Suñer, L. Analysing the Prosumer Opportunity. Prosumer Products’ Success or Failure. Journal of Engineering Design 2024, 35, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, B.; Botha, E.; Robertson, J.; Kemper, J.A.; Dolan, R.; Kietzmann, J. How to Grow the Sharing Economy? Create Prosumers! Australasian Marketing Journal 2020, 28, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metta, J.; Bachus, K. Mapping the Circular Maker Movement: From a Literature Review to a Circular Maker Passport. Deliverable 2020, 2, 68. [Google Scholar]

- Jorquera Ortega, A. Fabricación Digital: Introducción al Modelado e Impresión 3D. Serie diseño y autoedición, Jorquera O. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- López-Forniés, I. Concept Assessment Using Objective-Based Metrics on Functional Models. In Design Tools and Methods in Industrial Engineering II; Rizzi, C., Campana, F., Bici, M., Gherardini, F., Ingrassia, T., Cicconi, P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp. 320–327. [Google Scholar]

- Benyus, J.M. Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature; Perennial: New York, 2000; ISBN 0060533226. [Google Scholar]

- Speck, O.; Speck, D.; Horn, R.; Gantner, J.; Sedlbauer, K.P. Biomimetic Bio-Inspired Biomorph Sustainable? An Attempt to Classify and Clarify Biology-Derived Technical Developments. Bioinspir Biomim 2017, 12, 011004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asión Suñer, L.; López Forniés, I. El Diseño Modular En La Creación de Productos Para Prosumer, Universidad de Zaragoza: Zaragoza, 2022.

- Pentelovitch, N.; Nagel, J.K. Understanding the Use of Bio-Inspired Design Tools by Industry Professionals. Biomimetics 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Forniés, I.; Asión-Suñer, L. PROSUMER CONCEPT: CURRENT STATUS AND POSSIBLE FUTURE DEVELOPMENTS. Dyna (Spain) 2023, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Forniés, I.; Asión-Suñer, L. Self-Commissioning, Intuition and Prosumer. Proyecta56, an Industrial Design Journal 2023, 109–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, T.; Coley, D.; Borden, D.S. Navigating the Tower of Babel: The Epistemological Shift of Bioinspired Innovation. Biomimetics 2020, 5, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, J.; Arruda, A.; Laila, T.; Moura, E. Biomimicry as Metodological Tool for Technical Emancipation of Peripheral Countries. In Advances in Ergonomics in Design; Rebelo, F., Soares, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 349–356. [Google Scholar]

- Bobbe, T.; Krzywinski, J.; Woelfel, C. A Comparison of Design Process Models from Academic Theory and Professional Practice. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of International Design Conference, DESIGN; 2016; Vol. DS 84.

- Fayemi, P.E.; Wanieck, K.; Zollfrank, C.; Maranzana, N.; Aoussat, A. Biomimetics: Process, Tools and Practice. Bioinspir Biomim 2017, 12, 011002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salgueiredo, C.F.; Hatchuel, A. Beyond Analogy: A Model of Bioinspiration for Creative Design. Artificial Intelligence for Engineering Design, Analysis and Manufacturing 2016, 30, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.R. Policymakers’ Views on Sustainable End-User Innovation: Implications for Sustainable Innovation. J Clean Prod 2020, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BenMahmoud-Jouini, S.; Midler, C. Unpacking the Notion of Prototype Archetypes in the Early Phase of an Innovation Process. Creativity and Innovation Management 2020, 29, 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, S.; Fraser, M. Citizen Manufacturing: Unlocking a New Era of Digital Innovation. IEEE Pervasive Computing, Pervasive Computing, IEEE, IEEE Pervasive Comput. 2022, 21, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asión-Suñer, L.; López-Forniés, I. Review of Product Design and Manufacturing Methods for Prosumers. In International Joint Conference on Mechanics, Design Engineering & Advanced Manufacturing; Springer, 2021; pp. 128–134.

- Asión-Suñer, L.; López-Forniés, I. Adoption of Modular Design by Makers and Prosumers. A Survey. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Design Society. 2021; Vol. 1, 355–364. [Google Scholar]

- Asión-Suñer, L.; López-Forniés, I.; Rostomyan, G. CONCEPTUALIZATION OF MODULAR PRODUCTS FOR THE PROSUMER. A DESIGN WORKSHOP. Dyna (Spain) 2023, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autodesk, Inc. Instructables.

- Autodesk Instructables Wind Turbine Available online:. Available online: https://www.instructables.com/search/?q=wind%20turbine&projects=all (accessed on 27 June 2024).

- Lin, Z.C.; Hong, G.E.; Cheng, P.F. A Study of Patent Analysis of LED Bicycle Light by Using Modified DEMATEL and Life Span. ADVANCED ENGINEERING INFORMATICS 2017, 34, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surya, S. Development of Wind Torch for Bicycles. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Region 10 Humanitarian Technology Conference (R10 HTC); IEEE, August 28 2014; Vol. 2015-January; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Tummala, A.; Velamati, R.K.; Sinha, D.K.; Indraja, V.; Krishna, V.H. A Review on Small Scale Wind Turbines. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 56, 1351–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arranz, G.; Moriche, M.; Uhlmann, M.; Flores, O.; García-Villalba, M. Kinematics and Dynamics of the Auto-Rotation of a Model Winged Seed. Bioinspir Biomim 2018, 13, 036011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Ahmed, M.R. Blade Design and Performance Testing of a Small Wind Turbine Rotor for Low Wind Speed Applications. Renew Energy 2013, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okda, Y.M. El Design Methods of Horizontal Axis Wind Turbine Rotor Blades. International Journal of Industrial Electronics and Drives 2015, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Cohen, Y. Biomimetics—Using Nature to Inspire Human Innovation. Bioinspir Biomim 2006, 1, P1–P12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Cohen, Y. Biomimetics: Biologically Inspired Technologies; Bar-Cohen, Y., Ed.; CRC/Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, 2006; ISBN 0849331633. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent, J.F.V.; Bogatyreva, O.A.; Bogatyrev, N.R.; Bowyer, A.; Pahl, A.-K. Biomimetics: Its Practice and Theory. J R Soc Interface 2006, 3, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, E.A.; Vogel, S. Cat’s Paws and Catapults: Mechanical Worlds of Nature and People. Foreign Affairs 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshwani, S.; Casakin, H. Comparing Analogy-Based Methods—Bio-Inspiration and Engineering-Domain Inspiration for Domain Selection and Novelty. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Full, R.J.; Bhatti, H.A.; Jennings, P.; Ruopp, R.; Jafar, T.; Matsui, J.; Flores, L.A.; Estrada, M. Eyes Toward Tomorrow Program Enhancing Collaboration, Connections, and Community Using Bioinspired Design. Integr Comp Biol 2021, 61, 1966–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakaria, M.Y.; dos Santos, C.R.; Dayhoum, A.; Marques, F.D.; Hajj, M.R. Modeling and Prediction of Aerodynamic Characteristics of Free Fall Rotating Wing Based on Experiments. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 2019, 610, 012098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, A.; Yasuda, K. Flight Performance of Rotary Seeds. J Theor Biol 1989, 138, 23–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, K.; Azuma, A. The Autorotation Boundary in the Flight of Samaras. J Theor Biol 1997, 185, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, A.; Okuno, Y. Flight of a Samara, Alsomitra Macrocarpa. J Theor Biol 1987, 129, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, K.; Azuma, A. The Autorotation Boundary in the Flight of Samaras. J Theor Biol 1997, 185, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, E.R.; Pines, D.J.; Humbert, J.S. From Falling to Flying: The Path to Powered Flight of a Robotic Samara Nano Air Vehicle. Bioinspir Biomim 2010, 5, 045009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nave, G.K.; Hall, N.; Somers, K.; Davis, B.; Gruszewski, H.; Powers, C.; Collver, M.; Schmale, D.G.; Ross, S.D. Wind Dispersal of Natural and Biomimetic Maple Samaras. Biomimetics 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nave, G.K.; Hall, N.; Somers, K.; Davis, B.; Gruszewski, H.; Powers, C.; Collver, M.; Schmale, D.G.; Ross, S.D. Wind Dispersal of Natural and Biomimetic Maple Samaras. Biomimetics 2021, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Makdah, A.M.; Sanders, L.; Zhang, K.; Rival, D.E. The Stability of Leading-Edge Vortices to Perturbations on Samara-Inspired Rotors: A Novel Solution for Gust Resistance. Bioinspir Biomim 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaitan-Aroca, J.; Sierra, F.; Contreras, J.U.C. Bio-Inspired Rotor Design Characterization of a Horizontal Axis Wind Turbine. Energies (Basel) 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, T.; Tanaka, H.; Yoshimura, R.; Noda, R.; Fujii, T.; Liu, H. A Robust Biomimetic Blade Design for Micro Wind Turbines. Renew Energy 2018, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, R. Bio-Inspired Aerofoils for Small Wind Turbines. Renewable Energy and Power Quality Journal 2020, 18, 753–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siram, O.; Saha, U.K.; Sahoo, N. Blade Design Considerations of Small Wind Turbines: From Classical to Emerging Bio-Inspired Profiles/Shapes. Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, C.; Correa, M.; Villada, V.; Vanegas, J.D.; García, J.G.; Nieto-Londoño, C.; Sierra-Pérez, J. Structural Design and Manufacturing Process of a Low Scale Bio-Inspired Wind Turbine Blades. Compos Struct 2019, 208, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKegney, J.M.; Shen, X.; Zhu, C.; Xu, B.; Yang, L.; Dala, L. Bio-Inspired Design of Leading-Edge Tubercles on Wind Turbine Blades. In Proceedings of the 2022 7th International Conference on Environment Friendly Energies and Applications: Renewable and Sustainable Energy Systems, Hybrid Transportation Systems, Energy Transition, and Energy Security, EFEA 2022 - Proceedings; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2022.

- Omidvarnia, F.; Sarhadi, A. Nature-Inspired Designs in Wind Energy: A Review. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Directorate-General for Mobility and Transport Traffic Rules and Regulations for Cyclists Available online:. Available online: https://road-safety.transport.ec.europa.eu/eu-road-safety-policy/priorities/safe-road-use/cyclists/traffic-rules-and-regulations-cyclists-and-their-vehicles_en (accessed on 22 November 2023).

| Phases | Objectives | Actions and methods |

| Research | Understanding the market for flashlights and microturbines Search for bioinspired references. Know the biological principle of the seeds. Understanding sustainability and Circular Economy issues Defining needs |

Market analysis, similar features/functionality. Microturbine analysis Bioinspired case studies Sustainable design rules integration Writing the brief |

| Customized Design | Conceptual design. Custom-made design Establish the dimensions of the blades for the first tests. Know how the wind tunnel works |

Conceptual design. Preliminary design of blades and schematic or grid of component blocks. Recover old motors, LED and lenses for testing. |

| Prototyping | Experimentation and Validation Tests with recovered generators and various LED Final tests Calculation of electrical components |

3D printing, first tests Wind tunnel laboratory experimentation Electrical circuit design and optimization |

| Manufacturing | Carrying out the geometric design Integrating all components 3D printing final aesthetic design |

3D printing aesthetic design Adjustment of anchorages on bicycles |

| Validation | Actual assembly, adjustment and testing | First real tests of the prosumer product |

| Component | Specifications |

| Light | One 1 to 3 W LED; Focusing/converging lens |

| Legal | A white light source that must reach at least 150m with an illumination of 4 to 60 candelas (12.6 Lm to 188.5 Lm at 120°) and facing forward in the direction of the axis of motion [59] |

| Power | Autonomous charging by bicycle movement. Micro-wind turbine. Use of rechargeable batteries type AA or AAA |

| Circuit | Electronic circuit board for battery charging and illumination; Selector for charging or charging with illumination |

| Generator | Recycled motors from old appliances |

| Fabrication | 3D printing; Recycled and recyclable materials |

| Sustainability | Introduce sustainability rules through the recovery and reuse of materials and components |

| b = c ·1,9 (m) |

Swept area (m2) |

Theoretical power P (W) |

Resistor (Ω) |

Voltage (V) | Current (mA) | Speed (r.p.m) |

Turbine Power Pt (W) |

Cp= Pt/P | |

| H5C30 (led 5w) | 0,057 | 0,0102 | 5,91 | 25 | 7,8 | 160 | 5762 | 1,248 | 0,211 |

| H5C30 (led 5w) | 0,057 | 0,0102 | 5,91 | 56 | 9,4 | 120 | 6153 | 1,128 | 0,191 |

| H2C25 (led 5w) | 0,048 | 0,0071 | 4,10 | 25 | 7,24 | 142 | 5075 | 1,028 | 0,250 |

| H2C30 (led 1w) | 0,057 | 0,0102 | 5,91 | 25 | 8,2 | 120 | 5870 | 0,984 | 0,166 |

| H5C30 (led 1w) | 0,057 | 0,0102 | 5,91 | 25 | 7,7 | 125 | 7000 | 0,963 | 0,163 |

| Dron (led 5w) | 0,025 | 0,0020 | 1,14 | 39 | 4,87 | 50 | 2860-2900 | 0,2435 | 0,214 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).