1. Introduction

1.1. The Relationship Among Biomimetic Design, Art Design, and Design

Biomimetics emerged in the twentieth century as an interdisciplinary science born of rapid advances in biology and the technological sciences. Since its inception, it has demonstrated lasting vitality and relentless innovation, swiftly extending into numerous domains of the natural, technical, and engineering sciences while profoundly influencing the humanities and social sciences. This discipline, defined as the emulation of biological systems to create or enhance artificial systems, has evolved into a vital force for innovation across diverse domains.

At its core, biomimetic design involves systematically studying and applying the remarkable forms, structures, functions, materials, and behavioral strategies honed by organisms over millions of years of evolution. By analyzing natural phenomena—such as color, structural configuration, and acoustic patterns—designers translate these principles into concrete design solutions, enabling them to transcend conventional formal invention, instead embracing deep insight into evolutionary processes and their artistic transformation. Rather than merely replicating superficial shapes, biomimetic design engages with the functional and structural mechanisms of biological systems and the “hyper-rational” principles of natural efficiency and adaptability.

As an integrative methodology that unites scientific rigor and artistic sensibility, biomimetic design draws its theoretical foundation from the broader discipline of biomimetics, defined as “the science of imitating the principles of biological systems in constructing technical systems, or endowing artificial systems with features analogous to those of living organisms.”(Sun and Dong 2010) By systematically embedding features such as structure, function, materiality, coloration, and texture into human-made artifacts, biomimetic design embodies the ethos of “learning from nature, borrowing from life,” and serves as a nexus between human production activities and the natural world.

The impulse to imitate nature dates back to humanity’s earliest decorative arts. Primitive tools—wooden clubs and stone axes—directly mimicked the functional morphology of animal horns and claws; bone needles mirror the form of fish bones; and boat hulls derive from observations of fish bodies. In architecture, the Doric order of ancient Greece mirrors the sturdy physique of the mature male human form, whereas the Ionic order evokes the slender grace of the matured female silhouette. In ancient China, everyday vessels—such as tiger-shaped jars, zoomorphic ewers, eagle-shaped teapots, and ox-form lamps—and garment motifs like tortoise shell or fish scale patterns not only carried ritual or symbolic meaning (e.g., fertility, talismanic protection, or totemic worship) but also exemplified the transformation of real biological forms into decorative design elements.

Before the formal establishment of art and design as academic disciplines, decorative arts and art design existed in a state of natural unity. During the Renaissance, Giorgio Vasari introduced the concept of Arti del disegno, encompassing painting, sculpture, and architecture under a single rubric of “design,” thereby recognizing decorative arts as an intrinsic component of art design. Crafts of the period—pottery and bronze ornamentation, for instance—combined utility with decoration, making ornamentation the primary means of artistic expression and reflecting an original synthesis of function and aesthetics. Although later art history often relegated decorative arts to the status of “minor arts” or “crafts,” distinct from the “major arts” of painting and sculpture, their essential roles in beautifying objects, communicating meaning, and embodying the spirit of an era remained indispensable dimensions of design activity.

The late nineteenth-century Arts and Crafts movement, led by William Morris, marked a pivotal reevaluation of decorative art’s status. Reacting against the inferior quality engendered by industrial mass production, the movement championed “truth to materials” and the social responsibility of the designer—views that profoundly reshaped subsequent understandings of ornament’s value. Throughout history, natural flora and fauna have long served as fertile sources for decorative motifs. Owen Jones, in his seminal The Grammar of Ornament (1856), explicitly asserted that the forms found in nature constitute the fundamental resources of ornament design—a perspective that resonates strongly with the foundational tenets of contemporary biomimetic design.

The “Art Nouveau Movement” of the late 19th and early 20th centuries marked a pinnacle in the development of decorative arts, characterized by its veneration of the vital force inherent in nature and its endeavor to embody this vitality in creative expression. Designers within the movement extensively employed exaggerated, sinuous organic linear patterns and motifs, emulating the morphological characteristics of climbing vines and plants, thereby manifesting vigorous upward vitality. Notable exemplars include Victor Horta’s residential design at 12 Rue de Turin in Brussels, and Casa Milà and Sagrada Família in Barcelona, all of which epitomized the integration of natural forms into architectural design through decorative language. Antoni Gaudí, a devoted advocate of nature, regarded nature as the most perfect designer. His works were replete with biomimetic curves and organic forms, establishing the foundation for modern biomimetic design in both morphological language and emotional expression.

The early 20th century witnessed the emergence of the Bauhaus school, whose core principle of “form follows function” marked a paradigmatic shift in modern art and design theory. The principle of “unity of art and technology,” advocated by Walter Gropius, positioned traditional decorative arts as impediments to functional realization, thereby catalyzing a revolution toward design de-ornamentation. This ideological transformation manifested in fundamental changes to design language: geometric forms and standardized production supplanted elaborate ornamentation, exemplified by Marcel Breuer’s Wassily Chair as a quintessential representative of functionalist design. As design disciplines separated from fine arts and developed independently, decorative arts were relegated to the category of “minor arts,” while emerging disciplines such as industrial design and visual communication became the mainstream of modern design education. The biomimetic focus in design shifted from superficial morphological decoration to the emulation of organisms’ intrinsic mechanisms of high efficiency, low consumption, structural rationality, and functional superiority. This functional biomimicry emphasized addressing practical problems and enhancing product performance, reflecting a fundamental transition from “decoration for decoration’s sake” to “form expressing function.”

In the manifestation of formal aesthetic principles, biomimetic design and decorative arts demonstrate remarkable commonalities. Whether through formal principles such as symmetry, rhythm, and gradation, or visual elements like proportion, color, and texture, perfect exemplars can be found within natural biological forms. The geometric order embodied in plant structures such as lotus seed pods and sunflowers not only inspired the functional design of biomimetic products but also provided a rich formal vocabulary for decorative arts. This concrete or abstract treatment of natural forms constituted both an important technique in decorative arts and the nascent form of early biomimetic design.

Contemporary design exhibits pluralistic tendencies, with biomimetic design and decorative arts achieving profound integration within new contexts. This synthesis transcends simple morphological imitation, placing greater emphasis on conveying nature’s emotional resonance, cultural symbols, and ecological principles. Biomimetic design imbues products with natural charm, symbolic vitality, and affinity, satisfying contemporary humanity’s emotional yearning for a return to nature. The biomimetic forms themselves possess inherent decorative qualities and emotional value. In contrast, decorative artistic techniques are employed to express the deeper implications and cultural identity of biomimetic designs, as exemplified in bamboo-inspired cup designs that embody profound Eastern cultural heritage.

With the transition of design philosophy from pure functionalist aesthetics toward humanistic and ecologically-oriented approaches, biomimetic design has gradually emerged as a significant methodology in contemporary design. It effectively resolves the dichotomy between form and function that plagued traditional design, thereby achieving genuine organic unity between form and function. Biomimetic art design represents a comprehensive manifestation of purposiveness, not merely constituting formal beauty but also possessing profound theoretical foundations and technical underpinnings. This comprehensive characteristic enables biomimetic design to carry deeper cultural connotations and spiritual pursuits while fulfilling practical functions.

The integration of biomimetic design and decorative arts not only manifests at the visual formal level but also embodies profound cultural values and symbolic significance. It reflects humanity’s reverence for and learning attitude toward the natural world, representing the concrete practice of the traditional Chinese philosophical concept of “unity of heaven and humanity” (天人合一) in modern design. Within the context of globalization, biomimetic design serves as a universal design language capable of transcending cultural boundaries to convey humanity’s shared ecological consciousness and aesthetic pursuits. Simultaneously, biomimetic design practices under different cultural backgrounds also reflect the unique natural concepts and aesthetic traditions of various peoples, promoting the pluralistic development of design culture. More importantly, the philosophical outlook of “learning from nature” and “harmonious coexistence” embodied in biomimetic design aligns closely with contemporary green design and sustainable design principles. Emulating the operational principles and material characteristics of natural ecosystems not only constitutes decoration or form but also represents an important pathway toward environmental friendliness and resource conservation, transforming design itself into a form of “ecological decoration.”

According to the theoretical frameworks of modern design, design development should embody the unity of science, technology, and art. Biomimetic design, guided by this principle, has achieved systematic transcendence and innovative development of traditional decorative arts. Traditional decorative arts often remained at the level of superficial imitation and decorative application of natural forms, whereas biomimetic design penetrates deeper into the structural principles, functional mechanisms, and material characteristics of biological systems, fundamentally transforming from “formal resemblance” to “spiritual resemblance” and from “decorative function” to “functional utility.”

Traditional decorative arts’ appropriation of biological forms remained predominantly at the level of concrete imitation or abstract symbolism, as exemplified by the widespread circulation of decorative elements such as scrolling grass patterns, honeysuckle patterns, and lotus patterns. Contemporary designers frequently draw inspiration from natural forms such as bird nests and lotus flowers, creating designs that possess both decorative aesthetic appeal and functional satisfaction through the analysis and reconstruction of their structural characteristics. This transformative process transcends simple morphological imitation, constituting profound excavation and artistic sublimation of natural aesthetic principles.

The application of biomimetic design in contemporary art and design extends far beyond functional-level imitation, encompassing multiple artistic dimensions, including cultural connotation, emotional expression, and aesthetic experience. Designers imbue their works with unique aesthetic characteristics and cultural connotations through artistic refinement of animal and plant morphology and texture. Japanese designer Issey Miyake’s integration of shell textures and the layered sensibility of wood ear mushrooms into women’s fashion design fully demonstrates the artistic expressiveness of biomimetic design in the fashion domain. Across various categories, including packaging design, architectural design, and product design, biomimetic design presents rich artistic forms with the capacity for “artistic recreation of natural imagery,” enabling design works to carry profound emotional value, cultural connotation, and aesthetic significance while fulfilling functional requirements.

From early morphological decorative appropriation, through the Art Nouveau movement’s ultimate veneration of natural motifs, to the rise of functional biomimicry during the modernist period, and finally to the profound contemporary integration across emotional, symbolic, and sustainable dimensions, biomimetic design and decorative arts have continuously influenced and permeated each other. Biomimetic design both inherits the traditional focus on natural forms from decorative arts and achieves innovation through modern scientific and technological means, rendering it an extremely vital and promising methodology in contemporary art and design.

Biomimetic design provides decorative arts with an inexhaustible source of inspiration and scientific foundation, while decorative arts endow biomimetic designs with aesthetic value, emotional warmth, and cultural depth. Within the modern design context, “biomimicry” has become more than merely a means of achieving function or beautifying form; it has evolved into a design philosophy and aesthetic paradigm that connects humanity with nature, technology with the humanities, and the past with the future. It not only constructs morphology and structure through natural language but also endows design works with the threefold value of natural philosophy, aesthetic experience, and technological efficiency, representing the profound integration of design aesthetics and biological wisdom, thereby opening new pathways for the development of modern art and design.

1.2. Literature Review

The concept of “natural philosophy” has deep historical roots in China; however, the introduction and development of biomimetics as a modern discipline occurred relatively late. In 1960, the United States Air Force Aviation Agency first convened a biomimetics conference, where Steele proposed the concept of “bionics,” a term derived from Greek, meaning “the science of studying life systems.” Subsequently, industry and research domains began to strongly emphasize the theoretical construction and practical application of biomimetics. Early research was primarily concentrated in the field of industrial design, particularly in aircraft and vehicle design, providing innovative solutions for achieving high-efficiency and energy-saving objectives. Renowned designer Luigi Colani proposed a design philosophy inspired by nature, emphasizing the enhancement of products’ functionality and aesthetic value through the emulation of natural structures and morphologies. Colani’s “human-centered design” concept advanced the development of biomimetic design, enabling it to transcend the simple imitation of nature and evolve into an innovative design methodology.

In 1963, the term “bionics” was translated as “仿生学” (biomimicry, literally “imitating biology”) in Chinese, and systematic biomimetics research commenced around 1964. Subsequently, biomimetics reached several significant milestones: in January 1976, the Chinese Academy of Sciences successfully hosted China’s first biomimetics symposium in Beijing; in 1977, China’s biomimetics research plan was formally established at the “National Natural Science Discipline Planning Conference”; in 1979, the China Institute of Intelligence was established with biomimetic perception and intelligent technology as its primary research directions; in December 2003, an academic symposium titled “The Scientific Significance and Frontiers of Bionics” was convened; in 2010, the International Society of Bionic Engineering was formally established.

Regarding theoretical research on the developmental stages of biomimetics, scholars have proposed various classification models. In 2004, Yang divided the historical development of biomimetic design into five stages: prehistoric, ancient Chinese, ancient foreign, modern, and contemporary, providing a reference framework for tracing the historical trajectory of biomimetic design. In 2007, Lu Yongxiang, former President of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and President of Zhejiang University, pointed out that the biological world serves as a continuous source of human learning and that emulating the natural world possesses infinite potential for enhancing human creativity. In the same year, Wang proposed that “biomimetic design thinking originates from the combination of biomimetics and creative thinking,” exploring pathways for cultivating students’ biomimetic design thinking in industrial design education by integrating theory and practice. In 2008, Jing summarized the history of biomimetic design into three developmental stages: direct biomimicry (perceptual biomimicry), indirect biomimicry (rational biomimicry), and comprehensive biomimicry (scientific biomimicry), reflecting the historical inevitable trend of design development from ancient to contemporary periods.

In the realm of theoretical research and methodological construction, scholars have conducted in-depth exploration. In 2004, Yu summarized five core characteristics of biomimetic design science, systematically introducing biomimetic design from six dimensions, including color biomimicry, structural biomimicry, and morphological biomimicry, while proposing research pathways for biological models and technological models. In 2007, Ding employed cognitive psychology and product semantics theory to interpret product morphological biomimetic design, proposing a design process of “biological morphological observation and cognition–simplification–product design transformation.” During the same period, Dai analyzed biomimetic morphology, color, and texture in product design, constructing a comprehensive research framework from demand analysis to design evaluation.

In 2012, Gao proposed a philosophically elevated viewpoint, arguing that one should “develop systematic and macroscopic cognition of nature in practice, incorporating humanity into the ‘natural’ system” and pointing out that Laozi’s concept of “unity of heaven and humanity” enables design practice to connect with philosophy, with “biomimicry” functioning both as a methodology for morphological creation and as a holistic guiding principle. In 2013, Yu systematically discussed the philosophy, reasoning, and methods of biomimetic design, foreseeing that biomimetic design would profoundly influence people’s daily lives and values.

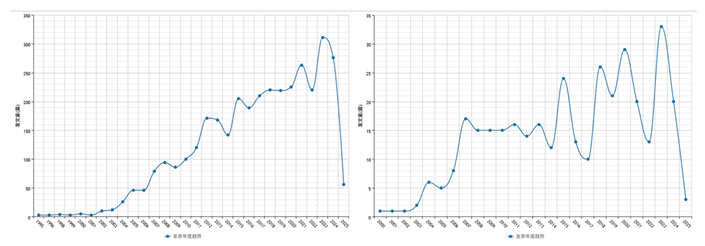

According to statistical data from China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), as of July 2025, 3,557 journal articles, 185 doctoral dissertations, and 997 master’s theses have “biomimetic design” as a keyword. The temporal distribution of publication volume presented in

Table 1 shows that with technological development and improved living standards, people’s demand for biomimetic product design and biomimetic products has been increasing. However, according to

Table 2, current research on biomimetic theory (philosophy) and artistic dimensions remains relatively insufficient. For example, search results using “biomimetic philosophy” and “biomimetic art” as keywords show that 113 and 30 related articles, respectively, were published from 2004 to July 2025, reflecting the sustained attention that biomimetic philosophy has received over the past two decades, with research fields gradually expanding from the initial focus on biology and mechanical engineering to the domain of art and design.

Among highly cited literature, Zhang (cited 292 times) focuses on design theory and control strategies for flexible exoskeleton systems, while Luo et al. (cited 177 times) systematically elaborate on the developmental status of six major domains—morphological biomimicry, functional biomimicry, structural biomimicry, textural biomimicry, color biomimicry, and conceptual biomimicry—providing theoretical guidance and methodological support for biomimetic design.

The field of biomimetic research has experienced remarkable growth and institutional development over recent decades, with numerous internationally renowned higher education institutions actively participating in both theoretical research and practical applications. Among these, the Center for Biomimetic Biology at the University of California, Berkeley, has achieved particularly noteworthy results and enjoys a prestigious reputation in the international academic community. As research has deepened and diversified, influential biomimetic works have successively shaped the field’s theoretical foundations, establishing it as a rigorous interdisciplinary field.

Contemporary biomimetic research demonstrates remarkable diversity and sophistication, as evidenced by recent comprehensive reviews and original research contributions. Reviews such as that by Rosellini et al. have advanced our understanding of scaffold design that mimics the layered structure of natural vascular walls, while Cui et al.’s analysis has elucidated the complex coordination mechanisms in biological and artificial ciliary systems. Original research has produced equally impressive innovations, including Fang et al.’s investigation of tail dynamics in gecko-inspired robots, Casagualda et al.’s development of mussel-inspired multifunctional polyethylene glycol nanoparticle interfaces using catechol-based adhesion strategies, and Ehrlich et al.’s groundbreaking discovery of silactins in sponge biosilica structures through desilicified analysis. Additional notable contributions include Winand et al.’s TriTrap robotic gripper inspired by insect tarsal chains, Chen et al.’s capillary wicking surfaces mimicking Heliamphora minor trichomes, and Saint-Sardos et al.’s development of the taxonomy-driven “Bioinspire-Explore” tool for biodiversity data analysis. These diverse research endeavors collectively demonstrate how biomimetic principles are being systematically applied across disciplines, from robotics and materials science to fluid dynamics and biotechnology, establishing biomimetics as a cornerstone of contemporary innovation in engineering and biological sciences.

Systematically examining the developmental trajectory and research status of biomimetic design both domestically and internationally shows that this field is currently at a critical stage of profound integration from theoretical construction to practical application, possessing broad developmental prospects and significant practical significance.

Statistical data reveal that although thousands of papers related to “biomimetic design” have been published in China and internationally, literature concerning “biomimetic art” remains extremely limited, indicating a notable deficiency in biomimetics research within the art and design domain. International research has primarily focused on specific technical applications, such as biological materials, robotics technology, and medical applications. For instance, the latest articles published in the journal Biomimetics are primarily concentrated in biomimetic mechanisms and design, biomimetic robotics, biofabrication and characterization, biomimetic and bioinspired chemistry, bioinspired sensing, nanotribology, nanomechanics, micro/nanoscale studies on biological systems, biomimetics inspired by animal and plant biomechanics, synthetic and biohybrid systems, self-organization and cooperative behavior, biomimetic aspects of tissue engineering, and bioinspired, biomedical and biomolecular materials, among other core research areas. However, the present study takes a distinctive approach, focusing specifically on applications within the art and design domain. Unlike existing research that emphasizes technical functionality, this study infuses biomimetic design with cultural and artistic connotations, thereby exploring how biomimetics can achieve both “imitating nature” and “creating aesthetic appeal” in art and design. This approach not only expands the application boundaries of biomimetics but also provides the art and design field with innovative creative approaches and methodologies, extending its scope from traditional engineering and technical applications into the realm of artistic creation.

2. The Concept and Application of Biomimetic Art Design

The German philosopher Hegel proposed that “beauty is the sensuous manifestation of the idea,” thus laying the theoretical foundation for design aesthetics. Designing according to the principles of beauty allows the creation of works with profound aesthetic significance. In this context, “beauty” encompasses not only the visual aspect of attractiveness but also the functional aspect of usability. In the design field, a truly “beautiful” product should meet users’ needs to the greatest extent and achieve an organic unity of form and function.

As a design methodology that integrates scientific rationality and artistic sensibility, biomimetic design has its aesthetic theory rooted in a deep understanding of and innovative application to the aesthetic laws found in nature. This theoretical system is based on profound insights into natural laws and artistic reconstruction, achieved through systematic imitation of biological forms, structural mechanisms, functional processes, and cultural imagery. Ultimately, it strives for the harmonious unity of “human–nature–machine.” The value of biomimetic design aesthetics is reflected not only in the surface imitation of biological forms but also in the abstract extraction and innovative reconstruction of natural aesthetic principles, resulting in a unique and comprehensive aesthetic system.

Biomimetic design goes beyond the decorative aspects of traditional design by effectively addressing functional pain points through structural biomimicry. Functional aesthetics theory asserts that true beauty is not merely found in the visual presentation of form but is embodied in the perfect realization of function. This theory emphasizes the harmonious unity of form and function, deeply embodying the classical aesthetic principle that “form follows function.”

Biomimetic design can be categorized into several directions, such as morphological biomimetics, functional biomimetics, structural biomimetics, color biomimetics, texture biomimetics, and cultural biomimetics, which is more inclined toward the arts. It also includes material biomimetics, a technical implementation method for structural or functional biomimetics. The specific carriers of these categories (morphology, function, structure, etc.) can be divided into animal biomimetics, plant biomimetics, and ecological biomimetics. Naturally, these fields often overlap in practical design because biological organisms are unified in form–function–structure, necessitating multidimensional coordination in biomimetic design.

Morphological biomimetics constitutes the core component of biomimetic design aesthetics. Biological forms in nature have evolved over millions of years under selective pressures, forming structures that are highly functional while maintaining visual appeal. Biomimetic design uses curves as the aesthetic vehicle, effectively overcoming the mechanical feel of geometric straight lines and imbuing products with organic vitality. From an aesthetic typology perspective, geometric curves (such as spheres and cones) embody the aesthetic characteristics of rational order, while free curves (such as biological textures) convey the aesthetic connotations of dynamic emotions.

German designer Luigi Colani proposed the design concept that “there are no straight lines in the universe,” exemplified in his signature egg-shaped tea set that uses smooth curves to simulate the harmonious forms found in nature—a classic example of morphological biomimetic design. Colani also applied this concept in his design of the Canon T90 camera, which provided important practical validation for morphological biomimetic theory. The design advocates that curved shapes are more in line with ergonomic principles and natural aesthetic laws. Specifically, the streamlined curved design of the pentaprism top mimics the organic forms of biological bodies (such as insect exoskeletons), replacing traditional straight-edged structures and significantly enhancing the comfort of grip. Moreover, the plastic casing undergoes precise curved surface transitions, optimizing hand fit and reducing fatigue during prolonged use.

In the automotive industry, sharks have become significant referential objects for morphological biomimicry due to their streamlined physiology and low-drag characteristics. Such designs are characterized primarily by elongated engine hoods, low-profile front fascias, and fluid contours, with design inspiration drawn directly from the streamlined morphology of shark heads. From a historical developmental perspective, classic BMW models from the 1960s to 1970s, the Ferrari F430’s “shark nose” intake design, and the Hyundai Genesis Coupe’s gill-like ventilation apertures all employed sharks as sources of biomimetic inspiration. Notably, BMW’s latest-generation 3 Series (designated G20 and subsequent models) has formally departed from the traditional kidney grille design, returning to the “shark nose” design style of the 1960s–1970s era, demonstrating the inheritance and evolution of biomimetic design.

Textural biomimicry, as a significant branch of biomimetic design, has opened innovative domains that emphasize functional and aesthetic values in contemporary art and design through precise simulation of surface textures, tactile qualities, and structural characteristics of biological organisms or natural objects. This design methodology not only achieves breakthroughs in visual effects but also demonstrates unique value across dimensions such as materials science, technological craftsmanship, and user experience.

In the realm of fashion and textile design, the application of textural biomimicry has evolved from simple visual imitation to a sophisticated system of technological innovation. McQueen’s 2010 reptilian texture collection represents a classic achievement in this domain. The collection created striking visual effects by simulating the tactile texture and iridescent luster of ancient reptilian scales. The designer employed digital drawing techniques to precisely convert biological dermal textures into print patterns, combining laser cutting and three-dimensional sewing techniques to recreate the complex layering of snake and lizard skins on leather and textile materials.

The development of synthetic fur and bark-textured fabrics has further expanded the application scope of textural biomimicry in textiles. Leopard print and snakeskin fabrics, through the organic integration of jacquard weaving and printing technologies, precisely simulate the patterns and tactile sensations of animal fur, providing innovative solutions for luxury fashion design that balance ethical considerations with visual effects. This technological development not only satisfies consumers’ pursuit of aesthetic quality but also reflects the design industry’s positive response to and practice of animal protection principles.

Biomimetic materials, through appropriation and simulation of structural characteristics, functional mechanisms, and formation pathways developed by natural organisms during prolonged evolutionary processes, drive the design and fabrication of novel intelligent materials. This approach not only directly utilizes the superior properties of natural materials (such as shells and spider silk) but also transforms complex biological microstructures into controllable artificial synthetic systems through biomimetic design. With natural components as the foundation, it integrates sustainable development concepts and achieves organic coupling of functions, including high strength, self-cleaning, and self-adaptation. Designers draw inspiration from biological morphology, structural functions, and color textures in nature, employing advanced technologies such as digital simulation, parametric modeling, and additive manufacturing to endow works with an organic unity of functionality and aesthetics. This fusion not only embodies reverence for and inheritance of natural wisdom but also demonstrates the profound alignment between sustainable development and innovative aesthetics, providing new creative paradigms and practical pathways for modern products, architecture, and public art.

The integration of biomimetic materials with artistic design centers on appropriating nature’s “form” (morphology/texture), borrowing nature’s “force” (structure/function), and conveying nature’s “spirit” (ecological concepts/emotional resonance). Typical cases address environmental concerns while creating artistic experiences that combine scientific rigor with poetic sensibility through waste material regeneration (wood chip ceramics), biological structure transformation (leaf veins and vertebrae), or intelligent responsive design (thermochromic color-changing materials), thereby advancing design toward the evolution of “coexistence with nature.”

Through mimicking the chromatic patterns and coloration mechanisms of organisms in nature, biomimetic coloration enables designers to create works that possess visual aesthetic appeal and functional richness, forming distinctive designs across multiple domains, including product packaging, spatial environments, and fashion brands.

The formation of biological color primarily relies on three natural mechanisms, providing the scientific foundation for biomimetic coloration technologies. The first is structural color biomimicry, whose principle lies in organisms generating colors through the interference, diffraction, or scattering of light waves by microstructures (such as photonic crystals, multilayer films, and diffraction gratings), rather than relying on chemical pigments. Typical examples include the iridescent effects of peacock feathers and the metallic luster of morpho butterfly wings. In biomimetic applications, this principle is employed in designing environmentally friendly materials that require no dyes, such as anti-counterfeiting labels and dynamic displays. The second is pigmentary color biomimicry, based on the mechanism whereby pigments within organisms (such as melanin and carotenoids) produce color through the absorption of specific wavelengths of light, exemplified by the chameleon’s color-changing ability through the contraction and expansion of pigment cells. Corresponding biomimetic applications include thermochromic coatings and emotion-responsive textiles. The third type is bioluminescent biomimicry, whose principle involves organisms converting chemical energy into light energy through biochemical reactions, producing cold light effects, such as the luciferase reaction in fireflies. This mechanism has inspired the development of biocompatible light sources and highly sensitive biosensors.

Based on the functional roles of biological color in nature, biomimetic design has established a clear functional classification system. Camouflage and defense functions originate from biological survival strategies, such as the octopus adjusting its pigment cells to simulate environmental textures, and the leaf butterfly’s wing coloration changing with environmental conditions. This function translates into dynamic adaptability in military camouflage uniforms and environmental coordination in architectural facade coatings within design applications. Information transmission and attraction functions are manifested in natural phenomena such as the vivid colors of flowers attracting pollinators and the feather displays of birds during courtship. Design applications include the use of saturated colors in children’s product packaging and the mimicry of bright poison frog coloration in warning signage. Environmental adaptation functions reflect intelligent biological responses to environmental conditions, such as the light-colored fur of camels reflecting sunlight for cooling and the bioluminescence of deep-sea creatures to lure prey. In the realm of product and packaging design, corresponding design practices include mimicking the gradient effects of natural coloration in children’s food packaging to enhance consumer appetite and trust; luxury anti-counterfeiting labels that utilize the optical properties of structural color to provide security assurance that is difficult to replicate. In architecture and materials science, smart windows achieve dynamic regulation of light transmission through electrochromic technology, while sports stadium roofs employ thermochromic materials to reduce energy consumption.

The core of functional biomimicry lies in the systematic transformation of biological adaptive mechanisms in nature into design language through in-depth research. This transformation process is not merely simple replication or imitation, but rather a profound understanding and innovative application of natural laws, fully embodying the effective integration of scientific rigor and artistic expression within biomimetic design aesthetic theory. Designers not only effectively solve complex problems in the real world but also imbue their works with profound aesthetic value and emotional resonance. This design philosophy transcends traditional functionalist frameworks, transforming the wisdom accumulated through millions of years of natural evolution into innovative solutions for human life, while simultaneously awakening people’s deep perceptual and emotional connection to natural aesthetics.

Structural biomimicry refers to a design methodology that systematically studies the internal structural characteristics of organisms (including skeletal systems, tissue textures, cellular arrangements, etc.), extracts their mechanical principles and organizational logic, and transforms these into engineering and technological solutions. Its core lies in simulating the performance advantages of biological structures, such as lightweight characteristics, strength–toughness properties, and energy efficiency, rather than merely remaining at the level of superficial morphological replication.

The design of the Japanese Shinkansen train nose provides a typical example of the successful application of structural biomimicry in the transportation sector. In the 1990s, Japanese engineer Eiji Nakatsu obtained design inspiration by observing the kingfisher’s specialized ability to dive into water for fishing while addressing the technical challenge of “tunnel boom” generated by the Shinkansen train during high-speed travel. The unique structure of the kingfisher’s slender, conical beak enables it to penetrate water with virtually no splash, thereby minimizing water flow resistance. Based on this biomimetic principle, the new nose design adopted a graduated longitudinal section structure to buffer airflow, replacing the original bullet-shaped nose design, successfully achieving the technical objective of “silent acceleration.” This design not only realized optimization at the functional level but also presented elegant, streamlined aesthetics at the visual level, fully demonstrating that curved surface aesthetics possesses the dual characteristics of technical rationality and natural dynamism.

The similarities, differences, or overlapping aspects between structural biomimicry and “morphological biomimicry” (focusing on aesthetic symbolic expression) and “functional biomimicry” (simulating biological behavioral mechanisms) lie in the fact that structural biomimicry concentrates on the engineering translation of physical construction, emphasizing technical breakthroughs through deep-level structural analysis. The design logic of structural biomimicry is manifested in the following key aspects:

The first is multi-scale structural analysis. The scale transition from micro to macro constitutes an important characteristic of structural biomimicry. For example, the “brick-mortar” layered structure of shells (microscopic level) has been successfully applied to increase the toughness of bulletproof ceramics; the hexagonal structure of honeycombs (macroscopic level) is widely applied in the development of lightweight materials for spacecraft.

The second is topological optimization and mechanical efficiency. Through topological analysis of biological structures, optimal material distribution is achieved. For instance, the skeletal distribution characteristics of flying fish pectoral fins inspired the carbon fiber structural design of unmanned aerial vehicle wing ribs, achieving ultra-high performance with a lift-to-drag ratio of 25. For example, the flying fish-inspired unmanned aerial vehicle designed by Professor Shen Haijun and his team from the School of Aerospace Engineering and Applied Mechanics at Tongji University as an example (

Figure 1) features a wingspan of 1.5 meters, body length of 1.8 meters, tricycle landing gear configuration, and high-efficiency twin-blade propellers, powered by a high-power electric motor and 6S lithium battery.

The primary technical challenges facing structural biomimicry include the necessity for interdisciplinary knowledge integration, involving the comprehensive application of biological anatomy, materials mechanics, and computer simulation technologies (such as computational fluid dynamics analysis and finite element simulation), while simultaneously requiring extremely high manufacturing precision, such as 3D printing technologies for micrometer-scale porous structures.

Structural biomimicry not only plays a significant role in the engineering and technological domains but also demonstrates unique value in the artistic design field. Through in-depth research and transformation of biological structures, structural biomimicry provides contemporary design practice with dual pathways of technological innovation and aesthetic expression, propelling design toward more intelligent, ecological, and humanistic directions of development.

In addition to the aforementioned biomimetic designs related to natural organisms, the aesthetic theory of biomimetic design carries profound cultural and artistic implications. This connotation extends beyond merely external imitation of natural forms, representing instead an innovative practice that integrates specific human cultural symbols and traditions with natural design—this is cultural biomimicry—transforming biological imagery into cultural symbols and effectively conveying national spirit and philosophical essence.

Regarding the relationship between cultural biomimicry and biomimetic design, two primary perspectives exist within academic discourse. The first perspective considers cultural biomimicry as a new form of biomimetic design. Scholars such as Song define cultural biomimicry as “the integration of traditional cultural design and biomimetic design,”(Song and Zhou 2007) achieving biomimicry through the functional, structural, and morphological aspects of cultural biomimetic objects (natural objects, artifacts, and cultural symbols imbued with cultural significance), thereby embodying the cultural connotations of these cultural biomimetic objects.

The second perspective regards cultural biomimicry as a subset of symbolic biomimicry within morphological biomimicry. Scholars such as Fang contend that cultural biomimicry employs biomimetic thinking to extract forms from entities in the cultural domain, engaging in innovative integration with product forms, behaviors, and contexts. They define cultural biomimetic objects as encompassing entities from the cultural domain that extend beyond natural phenomena. From the perspective of product morphological biomimetic design, scholars define symbolic biomimicry as the extraction of biological characteristics and their symbolic meanings(Song and Zhou 2007).

Regarding the focus of cultural biomimicry, both perspectives concentrate on the cultural domain, yet the second perspective is limited to attention on the morphological characteristics of culture. From the perspective of cultural spatiality, mid-layer culture centered on human behavioral activities can embody cultural connotations through dynamic behavioral characteristics. Compared to the second perspective, the first perspective provides a more comprehensive analysis of cultural biomimicry, advocating for multidimensional attention to cultural presentation methods encompassing form, function, structure, and other dimensions. Consequently, two approaches emerge in defining cultural biomimetic objects: the first defines them as entities from the cultural domain; the second defines them as natural organisms possessing cultural significance.

Taking the China Unicom logo as an example (

Figure 2), its core element derives from the Buddhist “Panchang pattern” (also known as the “Chinese knot “), whose interlocking and interconnected linear structure symbolizes the infinite connectivity and information flow of communication networks, aligning with the philosophical concepts of Eastern cyclical cosmology. The English design of “China Unicom” also incorporates the connotations of dual “i” (representing “I” (individual user) and “Information”), embodying the service philosophy of “customer-centricity” and reinforcing the symbiotic relationship between tradition and modernity.

In contrast, the Bank of China logo (

Figure 3) is prototyped after ancient Chinese copper coins, with its outer circle and inner square symbolizing the traditional cosmological view that “Heaven is round, Earth is square” (天圆地方). The central square aperture is transformed into the Chinese character “Zhong” (Central), simultaneously referencing “Bank of China” and implying the financial ethics of “centrality and harmony” (中正平和). This circular contour conveys stability and trustworthiness, while the square aperture reinforces a sense of order, aligning with the attribute requirements of the banking industry. This design elevates the physical form of currency into a cultural symbol, achieving unity between function and aesthetics.

In addition to the aforementioned common fields of biomimetic design, the aesthetic theory of contemporary biomimetic design also profoundly embodies important concepts such as ecological aesthetics. This concept emphasizes the harmonious coexistence of design with the natural environment, pursuing aesthetic values aligned with sustainable development. Ecological aesthetics posits that true beauty should harmonize with the natural environment, satisfying human needs while preserving the ecological balance of nature, thus achieving the harmonious development of humanity and nature.

Several design works by Luigi Colani fully demonstrate the integration of multidisciplinary fields, creating innovative products that possess both aesthetic value and functional requirements. Colani explicitly articulated his design philosophy: “What I do is simply imitate the truths that nature reveals to us.” This design philosophy profoundly embodies the core idea of ecological aesthetics: by emulating the wisdom of nature, he creates design works that are both beautiful and environmentally friendly. In the early 2000s, Colani was invited to participate in the overall conceptual design of the Shanghai Chongming Island Ecological Science and Technology City. Centered on “biodynamic” principles, he proposed an urban morphological concept that simulated the structure of the human torso, emphasizing a design philosophy that combined “unity of heaven and humanity” with sustainable development. This urban planning proposal adopted a biomimetic structure of a “reclining female human body”: left hand (airport), right hand (harbor), feet (information center), breasts (shopping district), heart (energy center), and lungs (sanatorium). Colani chose the female body because “earth and femininity belong to yin,” aligning with the Chinese concept of yin-yang harmony, and planned to design a complementary “male city” to achieve yin-yang balance. The design planning of Chongming City precisely positioned architectural clusters according to meridian pathways, thereby simulating energy flow between the human body and the city. This design mapped the physiological functions of human organs (such as cardiac energy supply and pulmonary respiration) onto the sustainable operations of urban systems (energy production and air purification), fully embodying the core concept of “ecological science and technology city.” Although this concept was ultimately not implemented due to multiple factors, including technology, funding, and policy, its “biomimetic organic” appearance and integrated renewable energy system framework have profoundly influenced the design and ecological planning fields.

With technological advancement, the artistic application of biomimetic design is evolving toward intelligent aesthetics. Intelligent aesthetics emphasizes that design works should not only possess static visual appeal but also dynamic interactive aesthetic characteristics. Through the integration of advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence and sensing technology, biomimetic design can create aesthetic works with adaptive and intelligent features. This developmental trend indicates that the aesthetic theory of biomimetic design is progressing from traditional morphological imitation toward higher levels, such as functional biomimicry and behavioral biomimicry, reflecting the profound integration of aesthetic theory and technological progress.

In summary, the artistic theory and application of biomimetic design constitute a multidimensional, multi-layered theoretical system that not only encompasses the recognition and application of natural aesthetic laws but also embodies the unity of multiple values, including science, art, culture, and ecology. Biomimetic aesthetics achieves the four-dimensional unity of function, form, psychology, and culture: it follows the rational principle of “form follows function” (such as the fluid dynamics optimization of the Shinkansen ), while awakening emotional resonance through curved language and natural symbols (such as the life metaphor in oval teapots ), and constructs a symbiotic philosophy of “human–nature–machine” at the cultural level. This provides abundant aesthetic resources and innovative ideas for contemporary art design, promoting the development and advancement of design aesthetics. Biomimetic design will continue to penetrate interdisciplinary fields, using natural wisdom to drive the aesthetic revolution of “technological poeticization” and deeply integrate human design practices with natural laws.

4. Development Trends and Innovation Directions in Bionic Art Design

Biomimetic art design is undergoing a profound transformation from morphological imitation to systematic integration. Traditional biomimetic design primarily focused on simulating apparent characteristics such as form and color, whereas contemporary trends are shifting toward multidisciplinary, collaborative, and systematic integration models. Biomimetics has deeply intersected with disciplines such as mathematics, biology, and materials science, forming specialized branches such as “biomimetic mathematics,” “biomimetic electronics,” and “biomimetic art.”

4.1. Construction of Ecological Biomimetic Systems Oriented Toward Sustainable Development

Ecological biomimetic design promotes the development of sustainable engineering systems through circular self-organization. Its core lies in drawing inspiration from nature’s efficient material and energy cycles—from biomimetic materials at the molecular level to systematic symbiosis at the urban scale—achieving “waste-free “ production and full life-cycle closed-loop management. This paradigm has transcended superficial imitation of natural forms, shifting toward multi-scale, multi-hierarchical ecological system integration. Chinese designers must not only adhere to environmental risk assessments stipulated by GB/T 42444-2023 GB/T 42444-2023 Biomimetics: Terminology, Concepts and Methodology is a standard issued by the Standardization Administration of China. This standard aims to systematically organize and standardize terminology, concepts, and methodology in the field of biomimetics, providing a unified foundation for research, application, and communication in related fields. but also avoid secondary disturbance to ecosystems during the innovation process, ensuring biomimetic technologies resonate harmoniously with nature. GB/T 42444-2023 requires designers to implement environmental risk assessments in material selection, morphological biomimicry, and end-of-life cycle phases, incorporating considerations of cultural and ecological sensitivity, such as avoiding the use of fungal materials in specific religious domains, or guiding user participation in ecological restoration through seed paper packaging. In morphological biomimicry, it is also necessary to avoid interfering with wildlife behavior, such as avoiding bird courtship color frequencies when developing chameleon-inspired biomimetic skins.

In the field of material innovation, biomimetic biodegradable materials form the foundation of ecological biomimetic systems. Different types of biomimetic materials, including fungal mycelium packaging, spider silk protein sutures, and mollusk biomineralization layers, each possess distinct advantages and limitations. Biodegradable packaging inspired by fungal mycelium has achieved commercialization. In addition, spider silk proteins are gaining prominence in the medical field due to their ultra-high strength, while biomimetic nacre remains difficult to produce at scale due to high energy consumption and costs, despite possessing superior structural properties. Future research is needed to improve degradation controllability, reduce manufacturing costs, and reveal industrialization pathways.

In the field of fashion, contemporary designers actively adopt renewable materials and environmentally friendly processes in their creative endeavors, addressing the urgent demands of contemporary society for ecological environmental protection while also demonstrating a commitment to social responsibility. Through in-depth research into plant growth mechanisms and the ecological circulation patterns of the natural world, designers have developed various bio-based materials and biodegradable, eco-friendly fabrics. These innovative materials not only meet the fundamental requirements of modern clothing in terms of functionality but also achieve significant advancements in environmental friendliness. Novel bio-based fibers developed through mimicking plant fiber structures (such as polylactic acid fibers extracted from corn and sugarcane, as well as bio-based materials that imitate plant fiber structures, including abaca and bamboo fibers) maintain excellent wearing comfort while possessing fully biodegradable characteristics, fully realizing the design philosophy of “from nature, returning to nature.”

In energy conversion and environmental resource utilization, ecological biomimetic design has likewise demonstrated numerous practical applications. Building photovoltaic skins based on photosynthesis principles (such as the Munich BIO facade) and artificial photosynthesis devices are making energy conversion processes “visible,” while fog-harvesting technology inspired by desert beetle water collection principles has achieved daily water production of approximately 10 liters per square meter in arid regions, though maintenance costs and cultural adaptability require optimization. The systematic symbiosis concept further integrates waste-energy-material systems: although “sponge city” and industrial ecology park cases each have distinct focuses, they all embody cross-disciplinary, multi-scale cascaded utilization approaches.

Art design plays a triple role in ecological biomimetic systems, connecting technology with the public, and nature with cities. First, it transforms cold biomimetic materials into tangible narrative symbols—such as packaging surfaces that preserve the natural texture of mycelium, or mineralization layers that simulate pearl luster through laser etching; second, artists integrate technical facilities such as photovoltaic facades, fog-harvesting devices, and rainwater retention systems into cultural contexts through scenario-based design, such as “atrapanieblas” fog nets with Andean weaving patterns and the ecological corridor landscape transformation at Beijing Olympic Park; finally, artistic intervention provides spatial narratives for urban-scale systems, combining energy flow, material circulation, and dynamic data visualization to shape embodied “industrial metabolic atlases.”

Looking forward, the sustainable development pathway of ecological biomimetic design must rely on interdisciplinary collaboration and policy support. To bridge the gap between laboratory and industrialization, designers, biologists, materials scientists, and urban planners should jointly establish transparent energy efficiency and environmental impact indicators; simultaneously, innovative mechanisms such as carbon trading systems and biomimetic materials community craft workshops can be leveraged to achieve true closed loops from technological efficiency to social acceptance. Only within the triangular framework of “policy–science–art “ can we advance toward a biomimetic paradigm of “ecology art” symbiosis, providing viable and sustainable solutions for addressing global environmental challenges.

4.2. Technological Innovation and Interdisciplinary Development

With continuous technological advancement, biomimetic art design demonstrates tremendous innovative potential in technical applications. Increased understanding of biological materials and electronic systems is expanding the capabilities of this field, enabling design works not only to imitate natural forms but also to achieve functional breakthroughs. The progress in biomimetic design relies on the development of multidisciplinary knowledge networks. For example, at the basic research level, biologists decode the mechanical advantages of hexagonal honeycomb structures, which engineers then transform and apply to aircraft honeycomb composite panels; neuroscientists explore octopus arm movement algorithms, providing control models for soft robotics. At the technological transformation level, a three-tier research and development system of “biological prototype–technical deconstruction–product realization” is established. For instance, antibacterial materials based on shark skin microstructures, optimized through fluid dynamics, are applied to biomimetic swimwear and antibacterial surface treatments for medical devices. Interdisciplinary collaboration not only resolves technical isolation problems but also catalyzes emerging professions such as biological architects and biomimetic materials engineers, driving a paradigm shift across industries.

At the digital technology level, artificial intelligence and algorithmic design serve as core tools by simulating biological intelligent systems through neural networks to achieve adaptive morphological generation; utilizing ant colony algorithms to optimize product structural pathways and enhance functional efficiency; and combining evolutionary algorithms to drive iterative evolution of biomimetic forms, such as product morphological derivation models based on principles of genetic mutation.

Biomimetic research in the social sciences further expands design dimensions. Future innovative development requires dismantling disciplinary barriers and constructing a tripart integration model of “natural sciences–social sciences–art design” to transition from singular morphological biomimicry to ecosystem biomimicry. Therefore, biomimetic art design demonstrates clear interdisciplinary development trends, increasingly emerging as a comprehensive interdisciplinary field that integrates knowledge systems from art, engineering, biology, and other disciplines. This interdisciplinary fusion not only broadens design perspectives but also provides greater possibilities for innovation.

The development trends of biomimetic art design are also evident in the enrichment of cultural connotations and the deepening of humanistic emotional dimensions. Modern biomimetic design no longer pursues mere functionality but integrates cultural elements, making it not only functional but also rich in symbolic meaning and emotional appeal. This emotional value creation manifests in three major transitions: natural sentiment awakening, life dynamic resonance, and cultural gene translation. French designer Philippe Starck’s branch-form faucet uses inverted tree branch morphology to evoke users’ subconscious associations with forests, transforming the daily act of handwashing into a poetic experience; the Exocet Chair mimics the dynamic curves of fish tails through wooden slats, allowing users to achieve different resting postures by adjusting angles, experiencing life rhythms through interaction. Chinese designers combine “bamboo node growth” morphology with traditional mortise and tenon craftsmanship, creating furniture products that conform to mechanical structures while embodying Eastern philosophy. Such designs construct spiritual healing spaces beyond the functional level through biological metaphors and emotional interaction mechanisms, responding to modern people’s psychological need to connect with nature.

In summary, the development trends of biomimetic art design exhibit diversified and integrated characteristics, with prospects presenting multi-dimensional fusion patterns. The dissolution of disciplinary barriers between art, engineering, and biology will stimulate innovation, while development consistently revolves around two core propositions: how technology can more deeply reveal and apply life wisdom, and how design can promote human–nature symbiosis.

By mimicking the operational mechanisms of natural ecosystems, biomimetic art design will increasingly influence works that are both aesthetically pleasing and environmentally friendly. Future designers need to develop a deeper understanding of the morphological structures and patterns of natural phenomena, integrating ecological thinking into every aspect of design to achieve harmonious unity between artificial and natural environments. Only by infusing ecological ethics and humanistic care into technological innovation can biomimetic design truly bridge civilization and nature, providing richer theoretical guidance and practical pathways for future design practice.

Table 1.

Annual publication quantity and trends of biomimetic design and biomimetic product-related papers in CNKI from left to right.

Table 1.

Annual publication quantity and trends of biomimetic design and biomimetic product-related papers in CNKI from left to right.

Table 2.

Annual publication quantity and trends of biomimetic clothing, biomimetic art, biomimetic concepts, and biomimetic notion papers in CNKI from left to right, top to bottom, respectively.

Table 2.

Annual publication quantity and trends of biomimetic clothing, biomimetic art, biomimetic concepts, and biomimetic notion papers in CNKI from left to right, top to bottom, respectively.

Figure 1.

The flying fish-like drone of the Shen Haijun team.

Figure 1.

The flying fish-like drone of the Shen Haijun team.

Figure 2.

From left to right: Chinese knot and China Unicom logo.

Figure 2.

From left to right: Chinese knot and China Unicom logo.

Figure 3.

From left to right: the copper coin “Kaiyuan Tongbao” and the Bank of China logo.

Figure 3.

From left to right: the copper coin “Kaiyuan Tongbao” and the Bank of China logo.

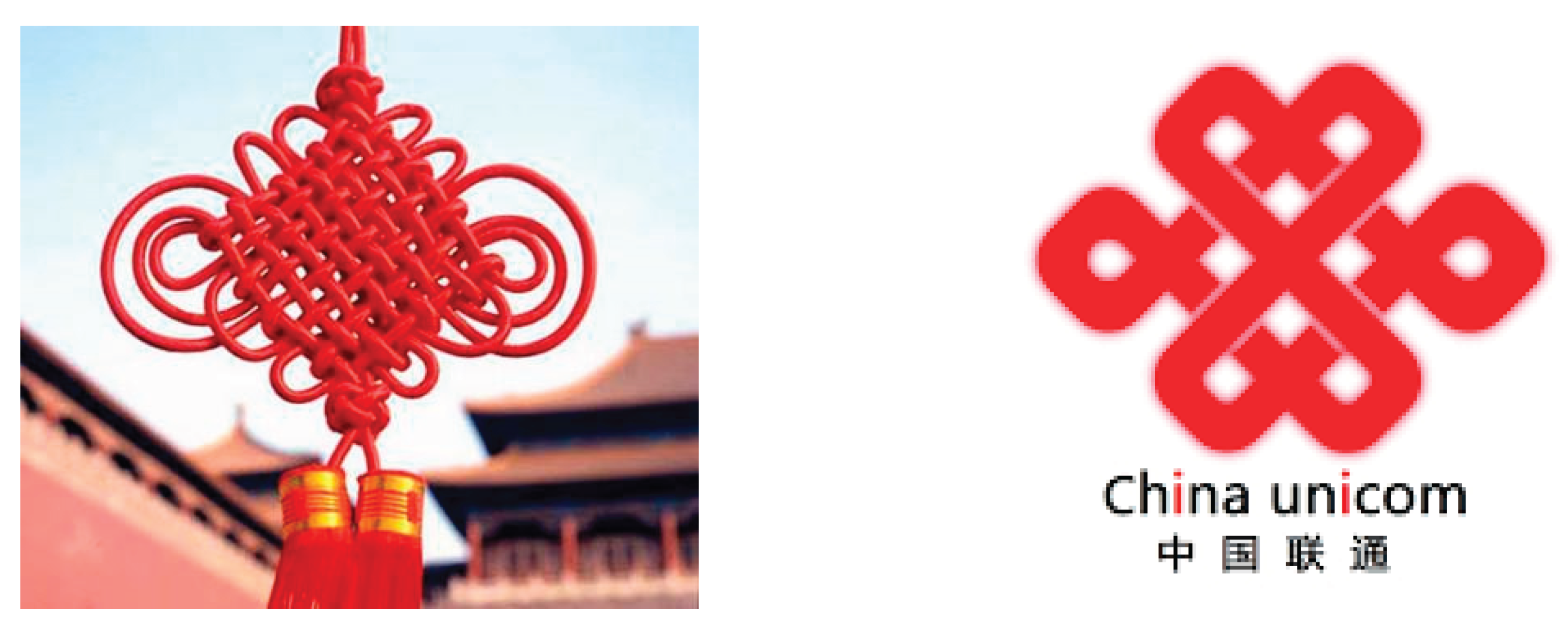

Figure 4.

“Derivative Floating Wetland” general layout.

Figure 4.

“Derivative Floating Wetland” general layout.

Figure 5.

From left to right: dovetail, linfan, pick up time, wooden road.

Figure 5.

From left to right: dovetail, linfan, pick up time, wooden road.

Figure 6.

Tokyo Yoyogi National Gymnasium.

Figure 6.

Tokyo Yoyogi National Gymnasium.

Figure 7.

China National Swimming Center “Water Cube”.

Figure 7.

China National Swimming Center “Water Cube”.

Figure 8.

Palazzetto dello Sport.

Figure 8.

Palazzetto dello Sport.

Figure 9.

Headquarters building of Shenzhen fashion brand Marisfrolg.

Figure 9.

Headquarters building of Shenzhen fashion brand Marisfrolg.

Figure 10.

Shanghai Natural History Museum New Hall.

Figure 10.

Shanghai Natural History Museum New Hall.

Figure 11.

India Lotus Temple.

Figure 11.

India Lotus Temple.

Figure 12.

Nakagin Capsule Tower.

Figure 12.

Nakagin Capsule Tower.

Figure 13.

Traffic Light Tree.

Figure 13.

Traffic Light Tree.

Figure 14.

Concrete petal sunshade pavilion in Confluence Park, USA.

Figure 14.

Concrete petal sunshade pavilion in Confluence Park, USA.

Figure 15.

Bowoos temporary pavilion.

Figure 15.

Bowoos temporary pavilion.

Figure 17.

Diffusion Choir.

Figure 17.

Diffusion Choir.

Figure 18.

From left to right, rainbow finch and Elie Saab 2014 gradient color garments.

Figure 18.

From left to right, rainbow finch and Elie Saab 2014 gradient color garments.

Figure 19.

Li Qingxuan’s extraction of jellyfish color elements.

Figure 19.

Li Qingxuan’s extraction of jellyfish color elements.

Figure 20.

Robert Wun 2023.

Figure 20.

Robert Wun 2023.

Figure 21.

Dior’s 1953 tulip series garments.

Figure 21.

Dior’s 1953 tulip series garments.

Figure 22.

Sha Zhenni’s Hug Me series.

Figure 22.

Sha Zhenni’s Hug Me series.

Figure 23.

NE·TIGER 2008 “Splendid National Colors: Chinese Formalwear” series.

Figure 23.

NE·TIGER 2008 “Splendid National Colors: Chinese Formalwear” series.

Figure 24.

Alexander McQueen Spring/Summer 2013 Women’s Show.

Figure 24.

Alexander McQueen Spring/Summer 2013 Women’s Show.

Figure 25.

Zuhair Murad Fall/Winter 2013 Women’s Collection.

Figure 25.

Zuhair Murad Fall/Winter 2013 Women’s Collection.

Figure 26.

Shark-skin Swimsuit.

Figure 26.

Shark-skin Swimsuit.

Figure 27.

FVM ‘JELLYFISH’ PUSHPIN.

Figure 27.

FVM ‘JELLYFISH’ PUSHPIN.

Figure 28.

“Living Sea Wall” developed through collaboration between Volvo, Sydney Institute of Marine Science, and Reef Design Lab.

Figure 28.

“Living Sea Wall” developed through collaboration between Volvo, Sydney Institute of Marine Science, and Reef Design Lab.

Figure 29.

Ceramic Corn USB Drive.

Figure 29.

Ceramic Corn USB Drive.

Figure 30.

“Radiolaria #1 “ Life-size 3D Printed Chair Model.

Figure 30.

“Radiolaria #1 “ Life-size 3D Printed Chair Model.

Figure 31.

“DIY Material Sustainable Design: Natural Resonance”.

Figure 31.

“DIY Material Sustainable Design: Natural Resonance”.

Figure 32.

2020 Tokyo Olympic Cherry Blossom Torch.

Figure 32.

2020 Tokyo Olympic Cherry Blossom Torch.

Figure 33.

“Juice Skin” by Naoto Fukasawa.

Figure 33.

“Juice Skin” by Naoto Fukasawa.

Figure 34.

Russian milk packaging “Soy Mamelle”.

Figure 34.

Russian milk packaging “Soy Mamelle”.

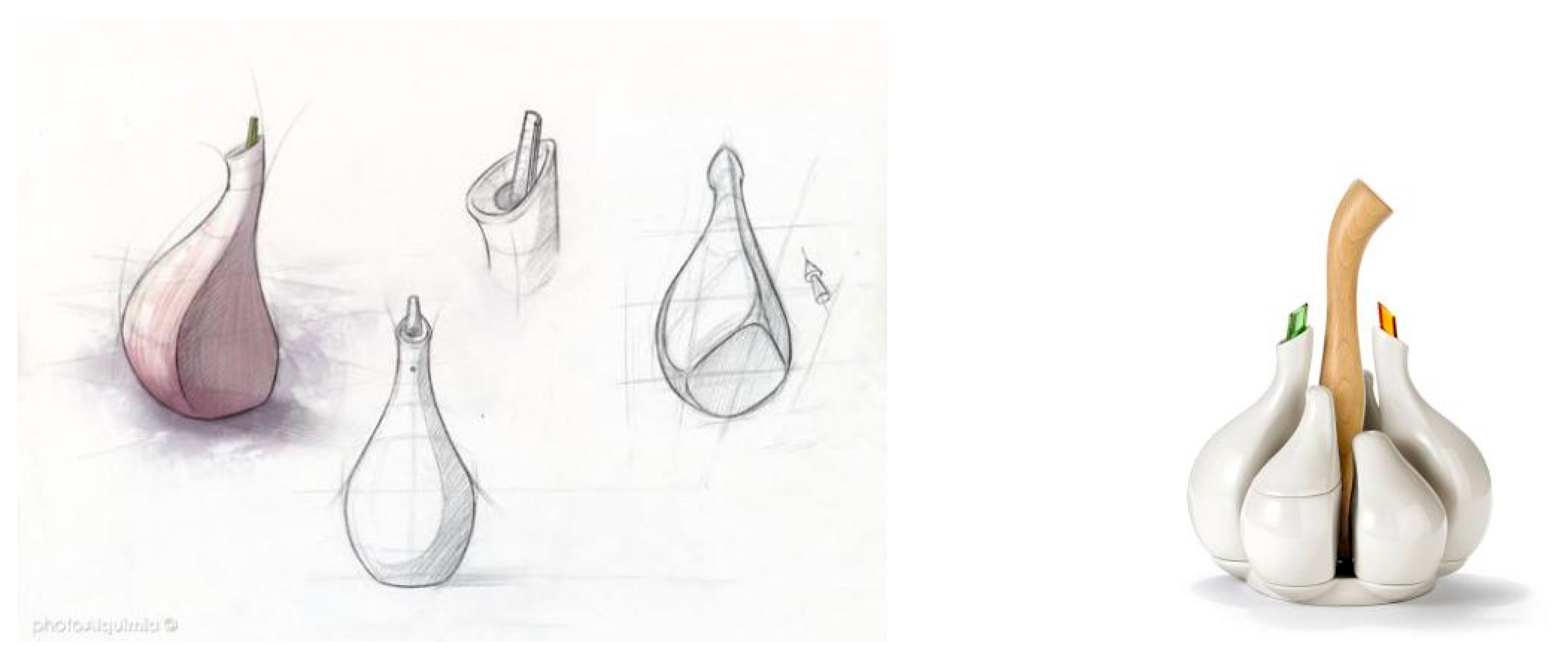

Figure 35.

Spanish Garlic Cruet “AJORí”.

Figure 35.

Spanish Garlic Cruet “AJORí”.