Submitted:

30 June 2024

Posted:

02 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

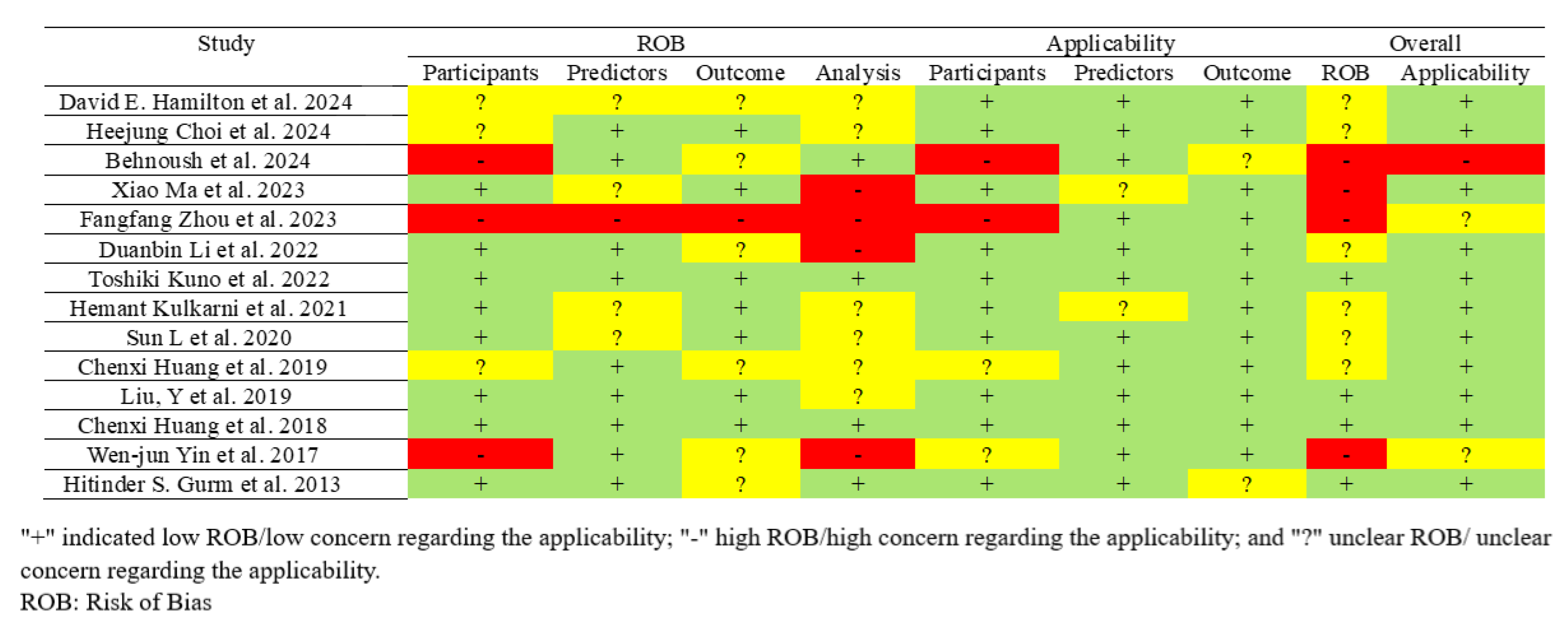

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction

- Outcomes: AUC with 95%CI, and any additional performance metrics reported (Accuracy, Sensitivity, Specificity, Precision) for each ML model (Supplementary Table S2 and Table 4).

2.4. Quality and Risk of Bias Assessment

2.5. Study Outcomes

2.6. Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

- is the number of cases with kidney complication

- is the number of cases without kidney complication

- and are constants calculated as:

2.7. Protocol Registration

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

- AKI: according to the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria is defined as an increase in serum creatinine by ≥0.3 mg/dL within 48 hours; or an increase in serum creatinine to ≥1.5 times baseline, which is known or presumed to have occurred within the prior 7 days; or Urine volume <0.5 mL/kg/h for 6 hours; is reported in 28.57% of studies [71,72,74,76].

- Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN): An abrupt (within 48 hours) reduction in kidney function, defined as an absolute increase in serum creatinine of ≥0.3 mg/dL, a percentage increase in serum creatinine of ≥50%, or a reduction in urine output (documented oliguria of <0.5 mL/kg/h for >6 hours); which is reported in 14.28% of studies (65, 67).

3.2. Feature of Importance and Predictors

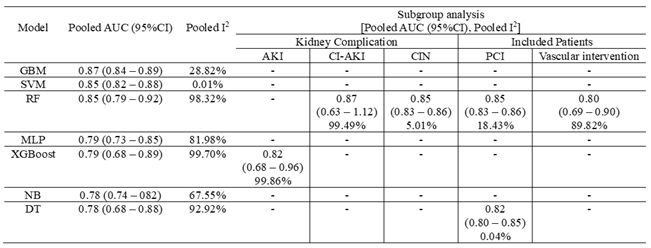

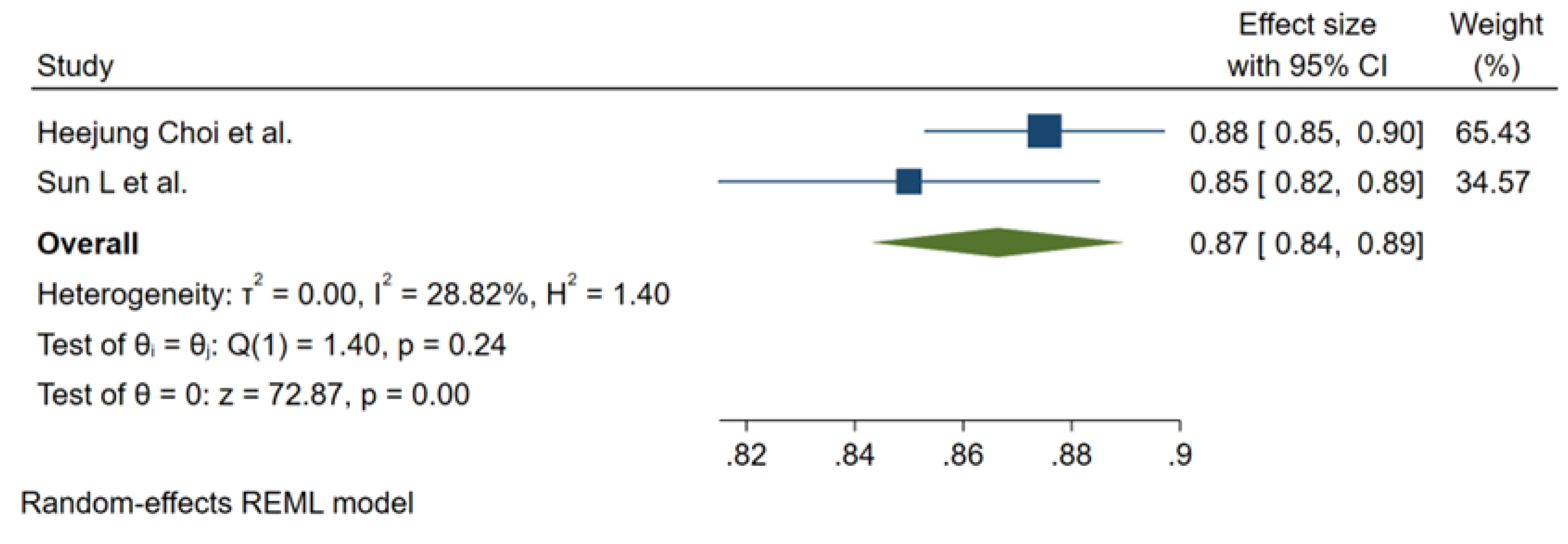

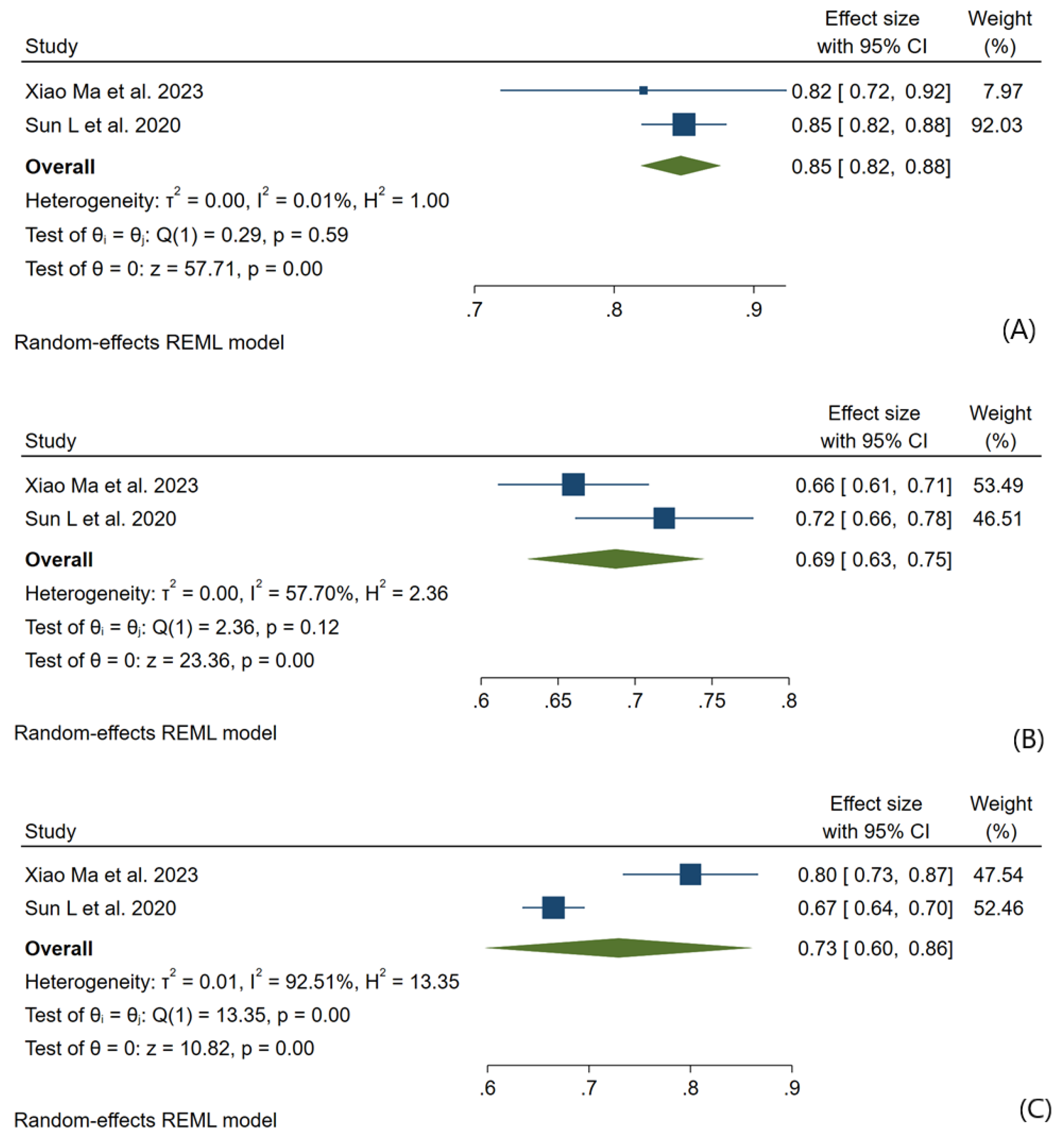

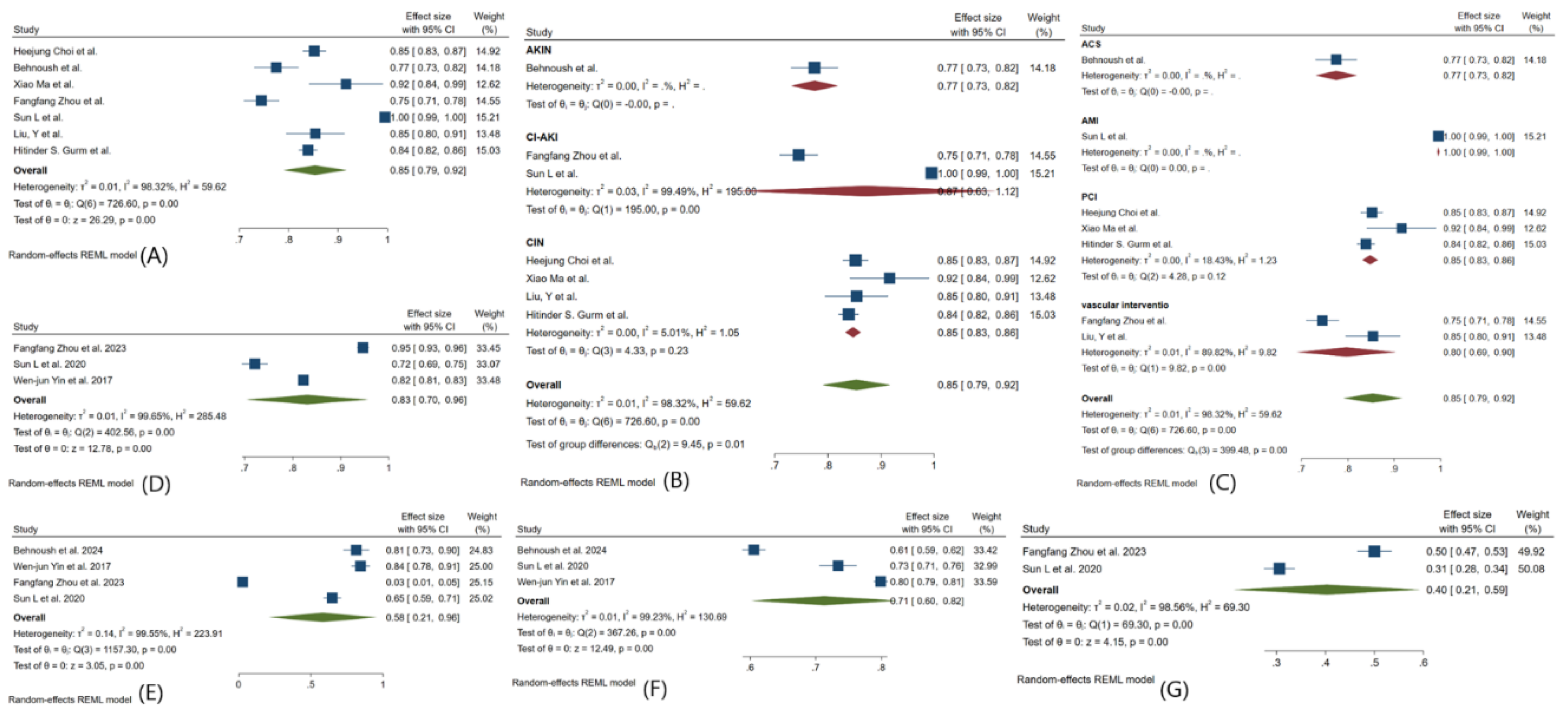

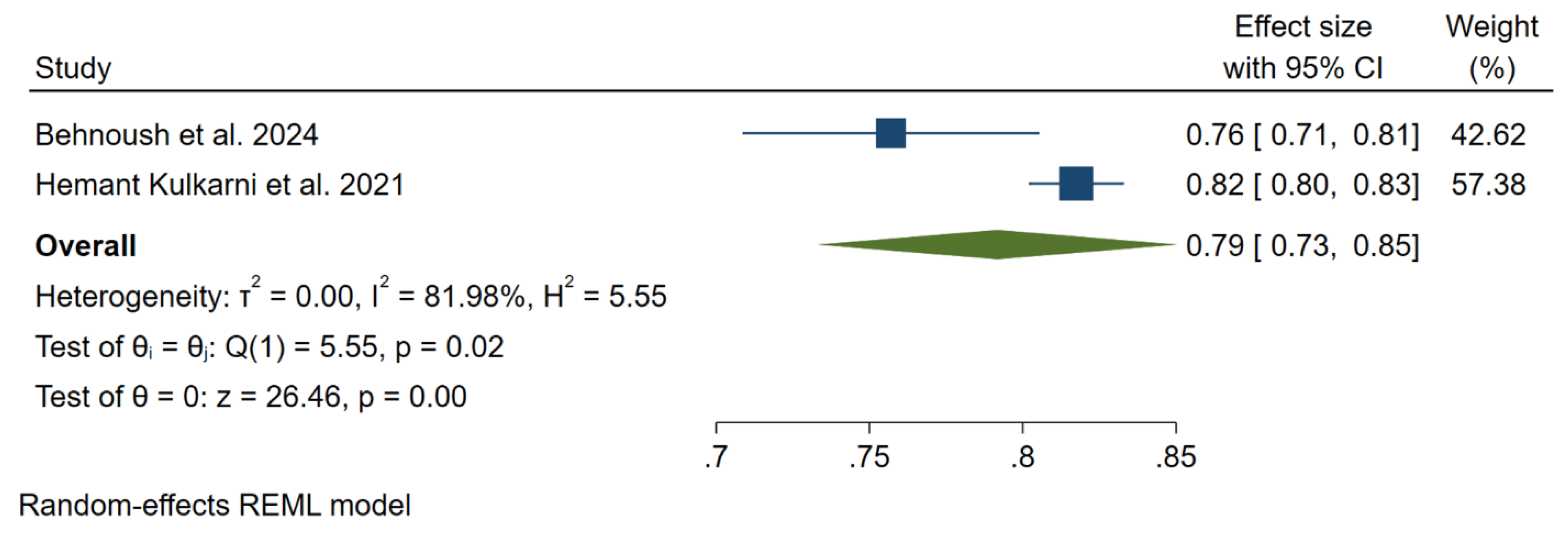

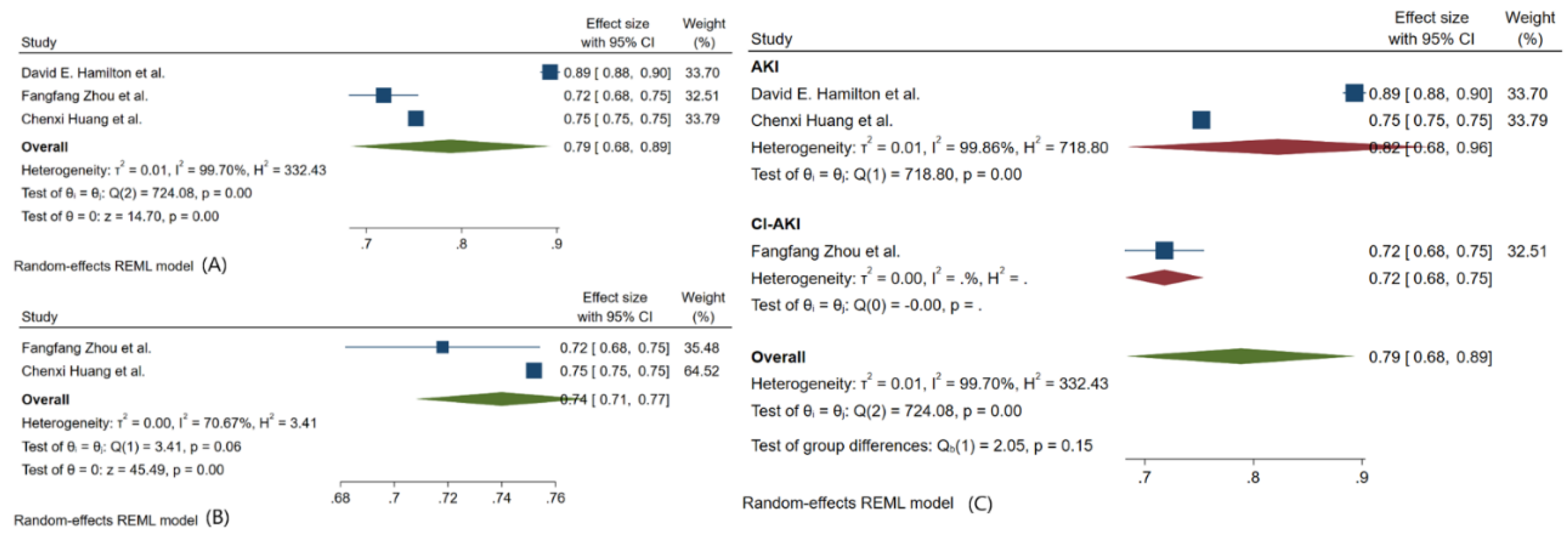

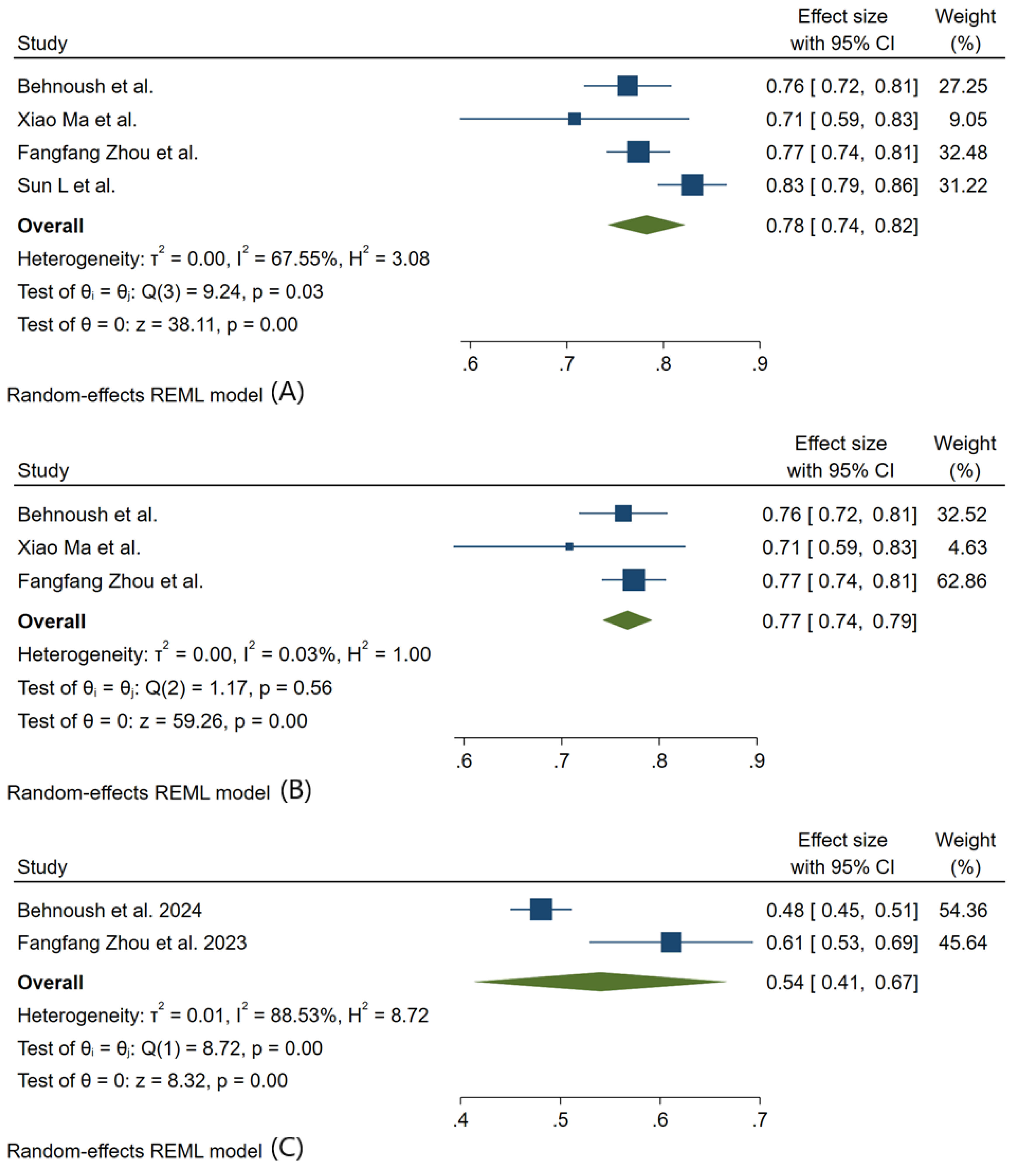

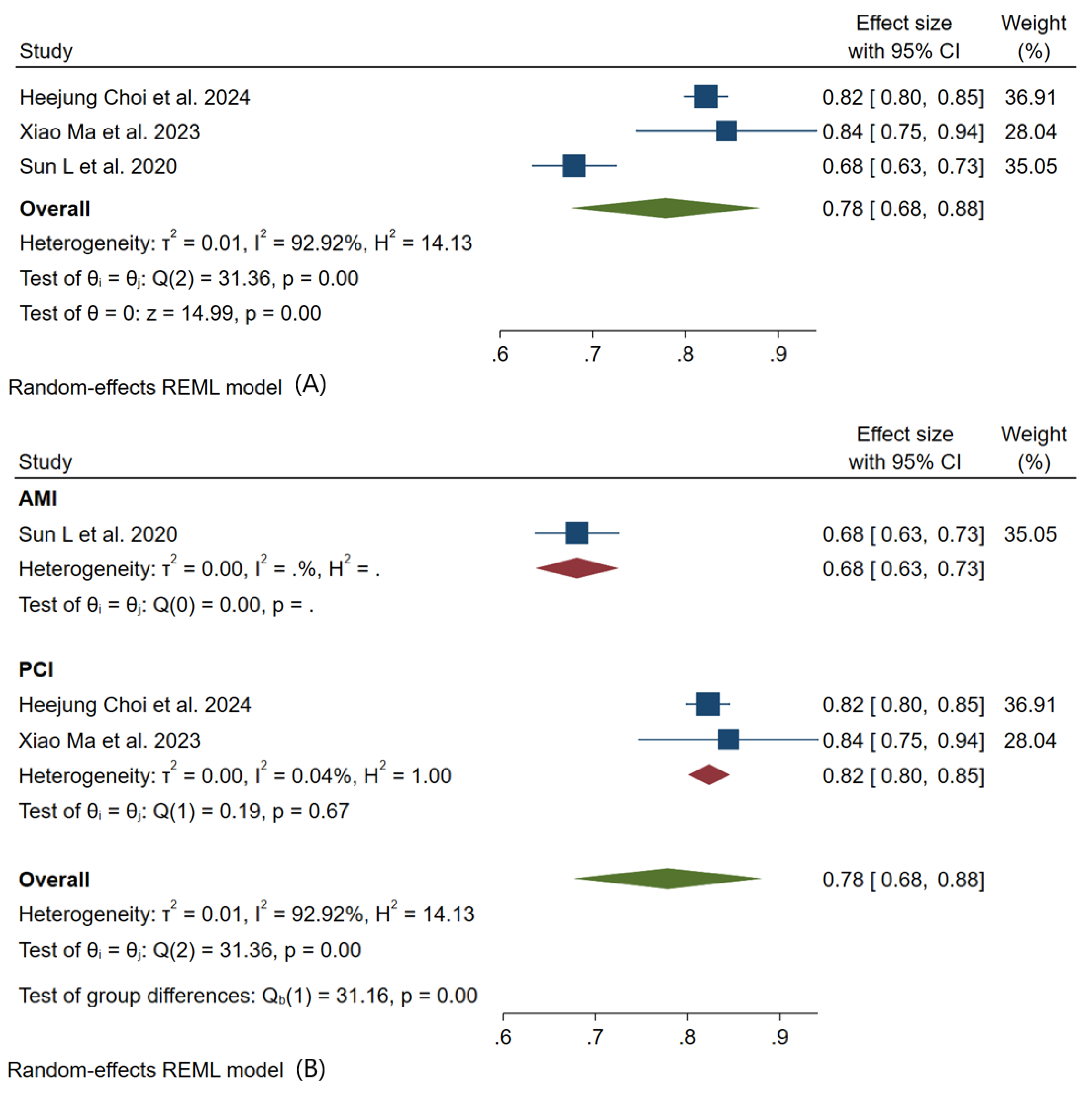

3.3. Meta-Analysis Outcomes

3.4. Pooled Analysis of Machine Learning Models Metrics

| Reference | Country | Model Type | Predictors | Included Patients | AKI definition |

| David E. Hamilton et al. 2024 [65] | USA | XGBoost LR |

Age, Sex, Body Mass Index (BMI), Smoking Status, Diabetes Mellitus, Hypertension, Hyperlipidemia, Prior Myocardial Infarction, Prior Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG), Prior Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI), Congestive Heart Failure, Peripheral Vascular Disease, Chronic Lung Disease, Chronic Kidney Disease, Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA), Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF), Systolic Blood Pressure, Diastolic Blood Pressure, Heart Rate, Hemoglobin, Platelet Count, Creatinine, and Cholesterol | patients undergoing PCI procedures | AKIN stage 1 or greater with absolute Cr increase of ≥0.3mg/dL or relative Cr increase ≥50%. |

| Heejung Choi et al. 2024 [66] | Korea | GBM RF LR DT Adaboost |

Age, history of chronic kidney disease (CKD), hematocrit result, troponin I level, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) level, base excess, and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) level. | Patients underwent PCI at After excluding patients due to a history of ESRD, HD, or recent PCI, and those without medical records for at least one year prior | individual creatinine test results higher than the minimum creatinine test value of the past 2 days by ≥0.3 mg/dL or an increase in creatinine ≥1.5× the average value of the past seven days. |

| Behnoush et al. 2024 [67] | Iran | RF LR CatBoost MLP NB |

Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF), Age, Fasting Plasma Glucose (FPG), Last Creatinine before PCI, Acute Myocardial Infarction (MI), Aborted Cardiac Arrest, CPR in PCI, Mean Creatinine, eGFR, Body Mass Index (BMI) | Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) patients undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI) | Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) defined by the acute kidney injury necrosis (AKIN) criteria: absolute increase of ≥ 0.3 mg/dL or a relative increase of ≥ 50% in serum creatinine after the procedure |

| Xiao Ma et al. 2023 [68] | China | LR RR NB KNN SVM DT RF XGBoost |

uric acid, peripheral vascular disease, cystatin C, creatine kinase-MB, haemoglobin, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, age, diabetes, systemic immune-inflammatory index, total protein, and low-density lipoprotein | Patients with coronary heart disease undergoing elective PCI | increase in serum creatinine (SCr) level by ≥0.5 mg/dL (≥44.2 µmol/L) or increase in SCr to ≥25% over baseline within 48–72 hours after contrast agent administration, or urine volume <0.5 mL/kg/h for 6 hours |

| Fangfang Zhou et al. 2023 [69] | China | LR RF GBDT XGBoost NB |

Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR), serum creatinine concentration, fasting plasma glucose concentration, use of β-blocker | patients who underwent elective vascular intervention, coronary angiography, and percutaneous coronary intervention | An increase in serum creatinine (Scr) ≥ 26.5 μmol/L within 48 hours of contrast medium (CM) administration or ≥ 1.5 times the baseline value. |

| Duanbin Li et al. 2022 [70] | China | RF | Age, Hemoglobin, N-terminal of the prohormone brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), cardiac troponin I (cTnI), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), C-reactive protein (CRP), eGFR (estimated filtration rate). | patients undergoing coronary angiography (CAG) | An increase in serum creatinine (Scr) ≥44 µmol/L (0.5 mg/dL) or ≥25% within 72 hours after intravascular administration of iodinated contrast agents. |

| Toshiki Kuno et al. 2022 [71] | Japan | Light GBM LR |

Age, chronic kidney disease (eGFR), previous heart failure, diabetes mellitus, cerebrovascular disease, heart failure at admission, cardiogenic shock at admission, cardiopulmonary arrest at admission, use of intra-aortic balloon pump, ST-elevation myocardial infarction, non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction/unstable angina, and preprocedural hemoglobin. | Patients undergoing PCI | AKI defined as an absolute increase of 0.3 mg/dL or a relative increase of 50% in serum creatinine |

| Hemant Kulkarni et al. 2021 [72] | USA | MLP | Not being on dialysis, having CKD, undergoing emergent PCI as an inpatient, and pre-PCI troponin T levels | Patients undergoing PCI | Acute kidney injury network (AKIN) stage 1 or greater or a new requirement for dialysis following PCI |

| Sun L et al. 2020 [73] | China | DT SVM RF KNN NB GB LR |

Neutrophil percentage, Age, Free triiodothyronine (FT3), Preoperation hypotension, Serum creatinine, Hemoglobin, Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, Total triglycerides, Brain natriuretic peptide, White blood cell count, High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, Heart rate, Body mass index, Cardiac troponin I, Systolic blood pressure, HbA1c, Diastolic blood pressure, Total cholesterol, Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), Weight. | Patients diagnosed with AMI undergoing PCI | Increase in creatinine by ≥0.3 mg/dl within 48 hours. Increase in creatinine to ≥1.5 times baseline within the prior 7 days. Urine volume <0.5 ml/kg/h for 6 hours. |

| Chenxi Huang et al. 2019 [74] | USA | GAM | Age, Prior heart failure, Cardiogenic shock w/in 24 hours, Cardiac arrest w/in 24 hours, Diabetes mellitus composite, CAD presentation composite, Heart failure w/in 2 weeks composite, Pre-procedure GFR, Pre-procedure hemoglobin, Admission source, Body mass index, PCI status, Pre-PCI ventricular ejection fraction | Patients undergoing PCI | Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) was defined using three thresholds for pre-procedure to post-procedure creatinine level increase: ≥0.3 mg/dL ≥0.5 mg/dL ≥1.0 mg/dL |

| Liu, Y et al. 2019[75] | China | RF | Age (years), Log BNP (pg/mL), SBP (mmHg), LVEF (%), Serum creatinine (mg/dL), Serum albumin (g/L), Serum urea nitrogen (mg/L), Haemoglobin (g/L), Heart rate (b.p.m.), CKMB (U/L), Haematocrit (%), K (mmol/L), Uric acid (mmol/L) | Patients aged ≥ 18 years undergoing PCI or CAG between January 2010 and December 2013 | Increase in SCr ≥ 0.5 mg/dL from baseline within 48–72 h after Procedure |

| Chenxi Huang et al. 2018 [76] | USA | LightGBM XGBoost LR |

Age, Prior heart failure, Cardiogenic shock within 24 hours (no versus yes), Cardiac arrest within 24 hours (no versus yes), Diabetes mellitus composite (no versus yes, insulin versus yes, others), CAD presentation composite (non-STEMI versus others), Heart failure within 2 weeks composite (no versus yes, NYHA class IV versus yes, others), Preprocedure GFR, Preprocedure hemoglobin, Admission source (emergency department versus others), Body mass index, PCI status (elective versus emergency versus others), Pre-PCI left ventricular ejection fraction | Patients undergoing PCI | Post-PCI AKI defined by Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN) Increase in serum creatinine ≥ 0.3 mg/dL or 1.5-fold from baseline |

| Wen-jun Yin et al. 2017 [77] | China | RF | Baseline eGFR, RDW, Triglycerides, Most recent serum creatinine before the procedure, HDL, Total cholesterol, LDL, BUN, P-LCR, Serum sodium, Plateletocrit (PCT), INR, Blood glucose | Treated patients with CM for CAG or PCI or received intravenous CM such as for CT or endovascular procedures | Increase in serum creatinine of 0.5 mg/dl (44.2 µmol/L) or 25% relative increase in serum creatinine within 72 hours after exposure to CM |

| Hitinder S. Gurm et al. 2013 [60] | USA | RF | PCI indication, PCI status, CAD presentation, cardiogenic shock, heart failure within 2 weeks, pre-PCI left ventricular ejection fraction, Diabetes mellitus/diabetes therapy, Age, weight, height, Creatine kinase-MB, serum creatinine, hemoglobin, troponin I, troponin T. | patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) | an impairment in renal function resulting in a ≥0.5 mg/dl increase in serum creatinine from baseline within a week following the procedure |

| Reference | Best Performing Model | Training Data set | Validation Data set | Testing Data set | AUC in Training Dataset Mean, (95%CI) |

|||

| With Kidney Complication | Without Kidney Complication | With Kidney Complication | Without Kidney Complication | With Kidney Complication | Without Kidney Complication | |||

| David E. Hamilton et al. 2024 [65] | XGBoost | 1623 | 63052 | 1082 | 42035 | - | - | 0.893 (0.883-0.903) |

| Heejung Choi et al. 2024 [66] | GBM | 1185 | 37296 | 460 | 10645 | - | - | 0.875 (0.853–0.897) |

| Behnoush et al. 2024 [67] | RF | 517 | 3155 | - | - | 129 | 791 | 0.775 (0.730–0.818) |

| Xiao Ma et al. 2023 [68] | SVM | 26 | 142 | - | - | 11 | 61 | 0.821 (0.719 – 0.923) |

| Fangfang Zhou et al. 2023 [69] | NB | 84 | 1477 | - | - | 36 | 633 | 0.774 (0.742, 0.806) |

| Duanbin Li et al. 2022 [70] | RF | 680 | 2828 | - | - | 280 | 1385 | 0.766 (0.737– 0.794) |

| Toshiki Kuno et al. 2022 [71] | Light GBM | 1587 | 15057 | - | - | 213 | 2365 | 0.790 (0.776, 0.804) |

| Hemant Kulkarni et al. 2021 [72] | MLP | 1532 | 19472 | - | - | 482 | 6519 | 0.8175 (0.8023 – 0.8326) |

| Sun L et al. 2020 [73] | RF | 169 | 953 | 57 | 316 | - | - | 0.995 (0.993–0.998) |

| Chenxi Huang et al. 2019 [74] | GAM | 228310 | 1848384 | 112697 | 849146 | - | - | 0.777 (0.775-0.779)1 0.839 (0.837-0.841)2 0.870 (0.867-0.873)3 |

| Liu, Y et al. 2019[75] | RF | 78 | 2350 | 37 | 1004 | - | - | 0.854 (0.796–0.913) |

| Chenxi Huang et al. 2018 [76] | XGBoost | 48878 | 614085 | 20948 | 263180 | - | - | 0.752 (0.749–0.754) |

| Wen-jun Yin et al. 2017[77] | RF | 942 | 6098 | 231 | 1529 | - | - | N.A. |

| Hitinder S. Gurm et al. 2013 [60] | RF | 1243 | 46758 | - | - | 505 | 20067 | 0.839 (0.821 – 0.857) |

|

|

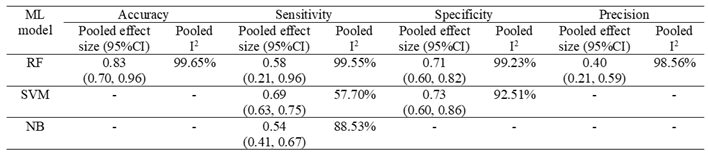

3.5. Quality Assessment

4. Discussion

4.1. Pathophysiology of Kidney Complications after PCI

4.2. Predictors of AKI/CIN post-PCI/CAG

4.2.1. Clinical Predictors

4.2.2. Biochemical Predictors

4.2.3. Preprocedural Predictors

4.3. Best performing ML Model

4.4. Study Limitations

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

List of abbreviations

References

- Xiao, C.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, K.; Liu, S.; He, N.; He, Y.; et al. Prognostic Value of Machine Learning in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofighi, S.; Poorhosseini, H.; Jenab, Y.; Alidoosti, M.; Sadeghian, M.; Mehrani, M.; et al. Comparison of machine-learning models for the prediction of 1-year adverse outcomes of patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Clinical Cardiology. 2023, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Murugiah, K.; Mahajan, S.; Li, S.-X.; Dhruva, S.S.; Haimovich, J.S.; et al. Enhancing the prediction of acute kidney injury risk after percutaneous coronary intervention using machine learning techniques: A retrospective cohort study. PLoS Medicine. 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niimi, N.; Shiraishi, Y.; Sawano, M.; Ikemura, N.; Inohara, T.; Ueda, I.; et al. Machine learning models for prediction of adverse events after percutaneous coronary intervention. Scientific Reports. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.R.; Mackenzie, T.; Maddox, T.M.; Fly, J.; Tsai, T.; Plomondon, M.E.; et al. Acute Kidney Injury Risk Prediction in Patients Undergoing Coronary Angiography in a National Veterans Health Administration Cohort With External Validation. Journal of the American Heart Association: Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Disease 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, P.-Y.; Chen, Y.-T.; Wang, C.-H.; Chiu, K.M.; Peng, Y.-S.; Hsu, S.-P.; et al. Prediction of the development of acute kidney injury following cardiac surgery by machine learning. Critical Care. 2020, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Feng, J.; Mei, S.; Zhong, H.; Tang, R.C.P.; Xing, S.; et al. MACHINE LEARNING MODELS FOR PREDICTING ACUTE KIDNEY INJURY IN PATIENTS WITH SEPSIS-ASSOCIATED ACUTE RESPIRATORY DISTRESS SYNDROME. Shock. 2023, 59, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H. A Machine Learning-Based Prediction Model for Acute Kidney Injury in Patients With Congestive Heart Failure. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, C.; Dong, W.; Li, B.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; et al. An Explainable Machine Learning Model to Predict Acute Kidney Injury After Cardiac Surgery: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Clinical Epidemiology. 2023, 15, 1145–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, H.; Ye, F.; Chen, D.; Wang, Q.; Liu, R.; Zhang, P.; et al. A predictive model based on a new CI-AKI definition to predict contrast induced nephropathy in patients with coronary artery disease with relatively normal renal function. Frontiers in cardiovascular medicine. 2021, 8, 762576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelhard, M.M.; Navar, A.M.; Pencina, M.J. Incremental benefits of machine learning—When do we need a better mousetrap? JAMA cardiology. 2021, 6, 621–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christodoulou, E.; Ma, J.; Collins, G.S.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Verbakel, J.Y.; Van Calster, B. A systematic review shows no performance benefit of machine learning over logistic regression for clinical prediction models. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2019, 110, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. bmj. 2021, 372. [Google Scholar]

- Moons, K.G.; Wolff, R.F.; Riley, R.D.; Whiting, P.F.; Westwood, M.; Collins, G.S.; et al. PROBAST: A tool to assess risk of bias and applicability of prediction model studies: Explanation and elaboration. Annals of internal medicine. 2019, 170, W1–W33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyerberg, E.W.; Vickers, A.J.; Cook, N.R.; Gerds, T.; Gonen, M.; Obuchowski, N.; et al. Assessing the performance of prediction models: A framework for traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology. 2010, 21, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Bmj. 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanley, J.A.; McNeil, B.J. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982, 143, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.; Xiao, T.; Zou, A.; Mao, L.; Chi, B.; Wang, Y.; et al. Predicting acute kidney injury risk in acute myocardial infarction patients: An artificial intelligence model using medical information mart for intensive care databases. Frontiers in cardiovascular medicine. 2022, 9, 964894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, M.; Wang, X.; Liu, S.; Xie, B.; Xue, S.; Yan, Y.; et al. A clinical score to predict severe acute kidney injury in Chinese patients after cardiac surgery. Nephron. 2019, 142, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiofolo, C.; Chbat, N.; Ghosh, E.; Eshelman, L.; Kashani, K., editors. Automated continuous acute kidney injury prediction and surveillance: A random forest model. Mayo Clinic Proceedings; 2019: Elsevier.

- Cox, M.; Panagides, J.; Di Capua, J.; Dua, A.; Kalva, S.; Kalpathy-Cramer, J.; Daye, D. An interpretable machine learning model for the prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy in patients undergoing lower extremity endovascular interventions for peripheral arterial disease. Clinical Imaging. 2023, 101, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Wang, X.-Z.; Wu, W.-D.; Shi, H.-P.; Yang, X.-J.; Wu, W.-J.; Chen, S.-X. Predicting the risk of acute kidney injury in patients after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) surgery: Development and assessment of a nomogram prediction model. Medical Science Monitor: International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research. 2021, 27, e929791-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, F.; Yang, H.; Wang, W.; Bi, X.; Dai, Y.; Zhu, A.; Guo, P. Acute kidney injury prediction model utility in premature myocardial infarction. Iscience 2024, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thongprayoon, C.; Hansrivijit, P.; Bathini, T.; Vallabhajosyula, S.; Mekraksakit, P.; Kaewput, W.; Cheungpasitporn, W. Predicting acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery by machine learning approaches. MDPI; 2020. p. 1767.

- Wu, L.; Hu, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, W.; Yu, A.S.; et al. Feature ranking in predictive models for hospital-acquired acute kidney injury. Scientific reports. 2018, 8, 17298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, D.; Cho, S.; Kim, Y.C.; Kim, D.K.; Oh, K.-H.; Joo, K.W.; et al. Use of deep learning to predict acute kidney injury after intravenous contrast media administration: Prediction model development study. JMIR Medical Informatics. 2021, 9, e27177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.; Li, Y.; Luo, C.; Chen, F.; Ling, G.; Zheng, B. Machine Learning for Predicting the Development of Postoperative Acute Kidney Injury After Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Without Extracorporeal Circulation. Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al'Aref, S.J.; Singh, G.; van Rosendael, A.R.; Kolli, K.K.; Ma, X.; Maliakal, G.; et al. Determinants of in-hospital mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention: A machine learning approach. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2019, 8, e011160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.-C.; Chen, K.-Y.; Li, S.-J.; Liu, C.-K.; Lin, Y.-C.; Chen, M. Implementing an ensemble learning model with feature selection to predict mortality among patients who underwent three-vessel percutaneous coronary intervention. Applied Sciences. 2022, 12, 8135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuno, T.; Numasawa, Y.; Mikami, T.; Niimi, N.; Sawano, M.; Kodaira, M.; et al. Association of decreasing hemoglobin levels with the incidence of acute kidney injury after percutaneous coronary intervention: A prospective multi-center study. Heart and vessels. 2021, 36, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Chan, T.-M.; Feng, J.; Tao, L.; Jiang, J.; Zheng, B.; et al. A pattern-discovery-based outcome predictive tool integrated with clinical data repository: Design and a case study on contrast related acute kidney injury. BMC medical informatics and decision making. 2022, 22, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheny, M.E.; Miller, R.A.; Ikizler, T.A.; Waitman, L.R.; Denny, J.C.; Schildcrout, J.S.; et al. Development of inpatient risk stratification models of acute kidney injury for use in electronic health records. Medical Decision Making. 2010, 30, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhu, M.X.; Yang, T.; Yin, Q.; Hou, Y. Risk prediction of major adverse cardiovascular events occurrence within 6 months after coronary revascularization: Machine learning study. JMIR Medical Informatics. 2022, 10, e33395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weisenthal, S.J.; Quill, C.; Farooq, S.; Kautz, H.; Zand, M.S. Predicting acute kidney injury at hospital re-entry using high-dimensional electronic health record data. PLoS ONE. 2018, 13, e0204920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, T.; Tian, C. Artificial Intelligence Algorithm-Based Computed Tomography Image in Assessment of Acute Renal Insufficiency of Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Contrast Media & Molecular Imaging. 2022, 2022, 2214583. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Zhang, P.; Jiang, H.; Kuang, J.; Wu, L. Using the Super Learner algorithm to predict risk of major adverse cardiovascular events after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with myocardial infarction. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2024, 24, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen P-y Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; Xian, Y.; Chen, J.-y.; Tan, N. A NOVEL TOOL FOR PRE-PROCEDURAL RISK STRATIFICATION FOR CONTRAST-INDUCED NEPHROPATHY AND ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN HYDRATION VOLUME AND CLINICAL OUTCOMES FOLLOWING CORONARY ANGIOGRAPHY AT DIFFERENT RISK LEVELS. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2018, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Fanous, H.; Mohammad, K.O.; Patel, A.P.; Liu, Y. SIMPLIFYING HEART-CATHETERIZATION, CONTRAST-INDUCED ACUTE KIDNEY INJURY PREDICTIVE MODELS, USING MACHINE LEARNING. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuno, T.; Mikami, T.; Sahashi, Y.; Numasawa, Y.; Suzuki, M.; Noma, S.; et al. TCT-332 Machine Learning Methods in Prediction of Acute Kidney Injury: Application of the US National Cardiovascular Data Registry Model on Japanese Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Patients. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhou, F.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Luo, Q. The Correlation Between Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Contrast-Induced AKI and Establishment of New Predictive Models by Machine Learning: FR-PO077. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2022, 33, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsutsui, R.S.; Johnston, J.D.; Felix, C.; Alberts, J.L.; Reed, G.W.; Puri, R.; et al. TCT-615 A Supervised Machine Learning Approach for Predicting Acute Kidney Injury Following Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, N.; Ebinger, J. A New Multivariate Model for Safe Contrast Limits to Prevent Contrast Induced Nephropathy After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Circulation 2019, 140 (Suppl_1), A15026-A. [Google Scholar]

- Dodson, J.A.; Hajduk, A.; Curtis, J.; Geda, M.; Krumholz, H.M.; Song, X.; et al. Acute kidney injury among older patients undergoing coronary angiography for acute myocardial infarction: The SILVER-AMI study. The American Journal of Medicine. 2019, 132, e817–e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.; Allen, D.W.; Graham, M.M.; Har, B.J.; Tyrrell, B.; Tan, Z.; et al. Comparative performance of prediction models for contrast-associated acute kidney injury after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2019, 12, e005854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Li, Q.; He, Y.; Jia, C.; Liang, G.; Lu, H.; et al. Comparison of cardiac biomarkers on risk assessment of contrast-associated acute kidney injury in patients undergoing cardiac catheterization: A multicenter retrospective study. Nephrology. 2023, 28, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, H.; Zhu, Y.; Shen, G.; Wang, Z.; Li, W. A predictive model for contrast-induced acute kidney injury after percutaneous coronary intervention in elderly patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2023, 453–465–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzendu, A.; Kennedy, K.; Chertow, G.; Amin, A.P.; Giri, J.S.; Rymer, J.A.; et al. Contemporary methods for predicting acute kidney injury after coronary intervention. Cardiovascular Interventions. 2023, 16, 2294–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Z.F.; Shen, H.; Tang, M.N.; Yan, Y.; Ge, J.B. A novel risk assessment model of contrast-induced nephropathy after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with diabetes. Basic & clinical pharmacology & toxicology. 2021, 128, 305–314. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, N.E.; McCarthy, C.P.; Shrestha, S.; Gaggin, H.K.; Mukai, R.; Magaret, C.A.; et al. A clinical, proteomics, and artificial intelligence-driven model to predict acute kidney injury in patients undergoing coronary angiography. Clinical cardiology. 2019, 42, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.R.; MacKenzie, T.A.; Maddox, T.M.; Fly, J.; Tsai, T.T.; Plomondon, M.E.; et al. Acute kidney injury risk prediction in patients undergoing coronary angiography in a national veterans health administration cohort with external validation. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2015, 4, e002136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, T.T.; Patel, U.D.; Chang, T.I.; Kennedy, K.F.; Masoudi, F.A.; Matheny, M.E.; et al. Validated contemporary risk model of acute kidney injury in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions: Insights from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry Cath-PCI Registry. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2014, 3, e001380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehran, R.; Aymong, E.D.; Nikolsky, E.; Lasic, Z.; Iakovou, I.; Fahy, M.; et al. A simple risk score for prediction of contrast-induced nephropathy after percutaneous coronary intervention: Development and initial validation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2004, 44, 1393–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-Y.; Liu, C.-F.; Shen, Y.-T.; Kuo, Y.-T.; Ko, C.-C.; Chen, T.-Y.; et al. Development of real-time individualized risk prediction models for contrast associated acute kidney injury and 30-day dialysis after contrast enhanced computed tomography. European Journal of Radiology. 2023, 167, 111034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victor, S.M.; Gnanaraj, A.; VijayaKumar, S.; Deshmukh, R.; Kandasamy, M.; Janakiraman, E.; et al. Risk scoring system to predict contrast induced nephropathy following percutaneous coronary intervention. indian heart journal. 2014, 66, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartholomew, B.A.; Harjai, K.J.; Dukkipati, S.; Boura, J.A.; Yerkey, M.W.; Glazier, S.; et al. Impact of nephropathy after percutaneous coronary intervention and a method for risk stratification. The American journal of cardiology 2004, 93, 1515–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.L.; Fu, N.K.; Xu, J.; Yang, S.C.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.Y.; Cong, H.L. A simple preprocedural score for risk of contrast-induced acute kidney injury after percutaneous coronary intervention. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions. 2014, 83, E8–E16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, N.; Li, X.; Yang, S.; Chen, Y.; Li, Q.; Jin, D.; Cong, H. Risk score for the prediction of contrast-induced nephropathy in elderly patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Angiology. 2013, 64, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.-m.; Li, D.; Cheng, H.; Chen, Y.-p. Derivation and validation of a risk score for contrast-induced nephropathy after cardiac catheterization in Chinese patients. Clinical and experimental nephrology. 2014, 18, 892–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghani, A.A.; Tohamy, K.Y. Risk score for contrast induced nephropathy following percutaneous coronary intervention. Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and Transplantation. 2009, 20, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gurm, H.S.; Seth, M.; Kooiman, J.; Share, D. A novel tool for reliable and accurate prediction of renal complications in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013, 61, 2242–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.-h.; Chen, J.-y.; Tan, N.; Zhou, Y.-l.; Li, H.-l.; et al. A simple pre-procedural risk score for contrast-induced nephropathy among patients with chronic total occlusion undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. International journal of cardiology. 2015, 180, 69–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maioli, M.; Toso, A.; Gallopin, M.; Leoncini, M.; Tedeschi, D.; Micheletti, C.; Bellandi, F. Preprocedural score for risk of contrast-induced nephropathy in elective coronary angiography and intervention. Journal of cardiovascular medicine. 2010, 11, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenzi, G.; Lauri, G.; Assanelli, E.; Campodonico, J.; De Metrio, M.; Marana, I.; et al. Contrast-induced nephropathy in patients undergoing primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2004, 44, 1780–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tziakas, D.; Chalikias, G.; Stakos, D.; Altun, A.; Sivri, N.; Yetkin, E.; et al. Validation of a new risk score to predict contrast-induced nephropathy after percutaneous coronary intervention. The American journal of cardiology. 2014, 113, 1487–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, D.E.; Albright, J.; Seth, M.; Painter, I.; Maynard, C.; Hira, R.S.; et al. Merging machine learning and patient preference: A novel tool for risk prediction of percutaneous coronary interventions. European Heart Journal. 2024, 45, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.; Choi, B.; Han, S.; Lee, M.; Shin, G.-T.; Kim, H.; et al. Applicable Machine Learning Model for Predicting Contrast-induced Nephropathy Based on Pre-catheterization Variables. Internal Medicine. 2024, 63, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behnoush, A.H.; Shariatnia, M.M.; Khalaji, A.; Asadi, M.; Yaghoobi, A.; Rezaee, M.; et al. Predictive modeling for acute kidney injury after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndrome: A machine learning approach. European Journal of Medical Research. 2024, 29, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Mo, C.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Gui, C. Prediction of the development of contrast-induced nephropathy following percutaneous coronary artery intervention by machine learning. Acta Cardiologica. 2023, 78, 912–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Lu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Lin, Y.; Luo, Q. Correlation between neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and contrast-induced acute kidney injury and the establishment of machine-learning-based predictive models. Renal Failure. 2023, 45, 2258983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Jiang, H.; Yang, X.; Lin, M.; Gao, M.; Chen, Z.; et al. An online pre-procedural nomogram for the prediction of contrast-associated acute kidney injury in patients undergoing coronary angiography. Frontiers in Medicine. 2022, 9, 839856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuno, T.; Mikami, T.; Sahashi, Y.; Numasawa, Y.; Suzuki, M.; Noma, S.; et al. Machine learning prediction model of acute kidney injury after percutaneous coronary intervention. Scientific reports. 2022, 12, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, H.; Amin, A.P. Artificial intelligence in percutaneous coronary intervention: Improved risk prediction of PCI-related complications using an artificial neural network. BMJ Innovations 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhu, W.; Chen, X.; Jiang, J.; Ji, Y.; Liu, N.; et al. Machine learning to predict contrast-induced acute kidney injury in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Frontiers in medicine. 2020, 7, 592007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Li, S.-X.; Mahajan, S.; Testani, J.M.; Wilson, F.P.; Mena, C.I.; et al. Development and validation of a model for predicting the risk of acute kidney injury associated with contrast volume levels during percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA network open. 2019, 2, e1916021–e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; Ye, J.; Xian, Y.; Wang, X.; Xuan, J.; et al. Random forest for prediction of contrast-induced nephropathy following coronary angiography. The International Journal of Cardiovascular Imaging. 2020, 36, 983–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Murugiah, K.; Mahajan, S.; Li, S.-X.; Dhruva, S.S.; Haimovich, J.S.; et al. Enhancing the prediction of acute kidney injury risk after percutaneous coronary intervention using machine learning techniques: A retrospective cohort study. PLoS medicine. 2018, 15, e1002703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, W.j.; Yi, Y.h.; Guan, X.f.; Zhou, L.y.; Wang, J.l.; Li, D.y.; Zuo, X.c. Preprocedural Prediction Model for Contrast-Induced Nephropathy Patients. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2017, 6, e004498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashani, K.B.; Levin, A.; Schetz, M. Contrast-associated acute kidney injury is a myth: We are not sure. Intensive Care Medicine. 2017, 44, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasan, J.; Zhuo, M.; Khan, M.T.; Fugar, S.; Li, H.; Desai, P.V.; et al. ANEMIA AND PERIPROCEDURAL DROP IN HEMOGLOBIN AS A RISK FACTOR FOR CONTRAST-INDUCED ACUTE KIDNEY INJURY IN PATIENTS UNDERGOING CORONARY ANGIOGRAM (CA) AND/OR PERCUTANEOUS CORONARY INTERVENTION (PCI). Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2018, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Qiu, H.; Hu, X.; Luo, T.; Gao, X.; Zhao, X.; et al. Predictive value of inflammatory factors on contrast-induced acute kidney injury in patients who underwent an emergency percutaneous coronary intervention. Clinical cardiology. 2017, 40, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, G.-z.; Yu, D.-q.; Cai, Z.-x.; Ni, C.-m.; Xu, R.-h.; Lan, B.; et al. Contrast-induced nephropathy in postmenopausal women undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction. The Tohoku journal of experimental medicine. 2010, 221, 211–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtul, A.; Gok, M.; Esenboğa, K. Prognostic Nutritional Index Predicts Contrast-Associated Acute Kidney Injury in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Acta Cardiologica Sinica. 2021, 37, 496–503. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, H.; Ye, F.; Chen, D.; Wang, Q.; Liu, R.; Zhang, P.; et al. A Predictive Model Based on a New CI-AKI Definition to Predict Contrast Induced Nephropathy in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease With Relatively Normal Renal Function. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.; Choi, B.H.; Han, S.; Lee, M.-J.; Shin, G.-T.; Kim, H.; et al. Applicable Machine Learning Model for Predicting Contrast-induced Nephropathy Based on Pre-catheterization Variables. Internal Medicine. 2023, 63, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassir, F. Contrast-induced nephropathy in diabetic and non-diabetic patients after coronary intervention. J Babylon Univ/Pure Appl Sci. 2014, 22, 2530–2546. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, W.; Lu, B.; Sheng, X.; Jin, N. Cystatin C in prediction of acute kidney injury: A systemic review and meta-analysis. American journal of kidney diseases : The official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2011, 58, 356–365. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y.; Chi, R.; Chen S-l Ye, H.; Yuan, J.; Wang, L.; et al. Evaluation of clinically available renal biomarkers in critically ill adults: A prospective multicenter observational study. Critical Care. 2017, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- . !!! INVALID CITATION !!!

- Haase, M.; Bellomo, R.; Devarajan, P.; Schlattmann, P.; Haase-Fielitz, A. Accuracy of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) in diagnosis and prognosis in acute kidney injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American journal of kidney diseases : The official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2009, 54, 1012–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebetrau, C.; Gaede, L.; Doerr, O.; Blumenstein, J.; Rixe, J.; Teichert, O.; et al. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) for the early detection of contrast-induced nephropathy after percutaneous coronary intervention. Scandinavian Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation. 2014, 74, 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, J.; Dent, C.L.; Tarabishi, R.; Mitsnefes, M.M.; Ma, Q.; Kelly, C.; et al. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) as a biomarker for acute renal injury after cardiac surgery. The Lancet. 2005, 365, 1231–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wybraniec, M.T.; Chudek, J.; Bożentowicz-Wikarek, M.; Mizia-Stec, K. Prediction of contrast-induced acute kidney injury by early post-procedural analysis of urinary biomarkers and intra-renal doppler flow indices in patients undergoing coronary angiography. Journal of interventional cardiology. 2017, 30, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musiał, K.; Stojanowski, J.; Miśkiewicz-Bujna, J.; Kałwak, K.; Ussowicz, M. KIM-1, IL-18, and NGAL, in the machine learning prediction of kidney injury among children undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation—A pilot study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023, 24, 15791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Li, J.; Gu, J.; Li, S.; Dang, Y.; Wang, T. Plasma levels of IL-8 predict early complications in patients with coronary heart disease after percutaneous coronary intervention. Japanese heart journal. 2003, 44, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, R.; Li, Y.; Zink, D.; Loo, L.-H. Supervised prediction of drug-induced nephrotoxicity based on interleukin-6 and-8 expression levels. BMC bioinformatics. 2014, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Meyrier, A.Y. Renal complications associated with contrast media. European Radiology Supplements. 2006, 16, D11–D6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briguori, C.; Tavano, D.; Colombo, A. Contrast agent--associated nephrotoxicity. Progress in cardiovascular diseases. 2003, 45, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faucon, A.-L.; Bobrie, G.; Clément, O. Nephrotoxicity of iodinated contrast media: From pathophysiology to prevention strategies. European journal of radiology. 2019, 116, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, G.; Briguori, C.; Quintavalle, C.; Zanca, C.; Rivera, N.V.; Colombo, A.; Condorelli, G. Contrast agents and renal cell apoptosis. European heart journal. 2008, 29, 2569–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodama, A.; Watanabe, H.; Tanaka, R.; Tanaka, H.; Chuang, V.T.G.; Miyamoto, Y.; et al. A human serum albumin-thioredoxin fusion protein prevents experimental contrast-induced nephropathy. Kidney international. 2013, 83, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCullough, P.A.; Adam, A.; Becker, C.R.; Davidson, C.J.; Lameire, N.; Stacul, F.; Tumlin, J.A. Risk prediction of contrast-induced nephropathy. The American journal of cardiology. 2006, 98, 27K–36K. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, R.J.; Mehran, R.; Natarajan, M.K.; Doucet, S.; Katholi, R.E.; Staniloae, C.S.; et al. Contrast-induced nephropathy and long-term adverse events: Cause and effect? Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2009, 4, 1162–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspelin, P.; Aubry, P.; Fransson, S.G.; Strasser, R.H.; Willenbrock, R.; Berg, K.J. Nephrotoxic effects in high-risk patients undergoing angiography. The New England journal of medicine. 2003, 348, 491–499. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, M.C.; Häberle, L.; Müller, V.; Bautz, W.; Uder, M. Nephrotoxicity of iso-osmolar iodixanol compared with nonionic low-osmolar contrast media: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Radiology. 2009, 250, 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Ryu, J.Y.; Kang, M.W.; Seo, K.H.; Kim, J.; Suh, J.; et al. Machine learning-based prediction of acute kidney injury after nephrectomy in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Scientific Reports. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).