Submitted:

05 September 2025

Posted:

08 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background

Rationale and Study Objective

Aim of the Work

Patients and Methods

Study Design and Setting

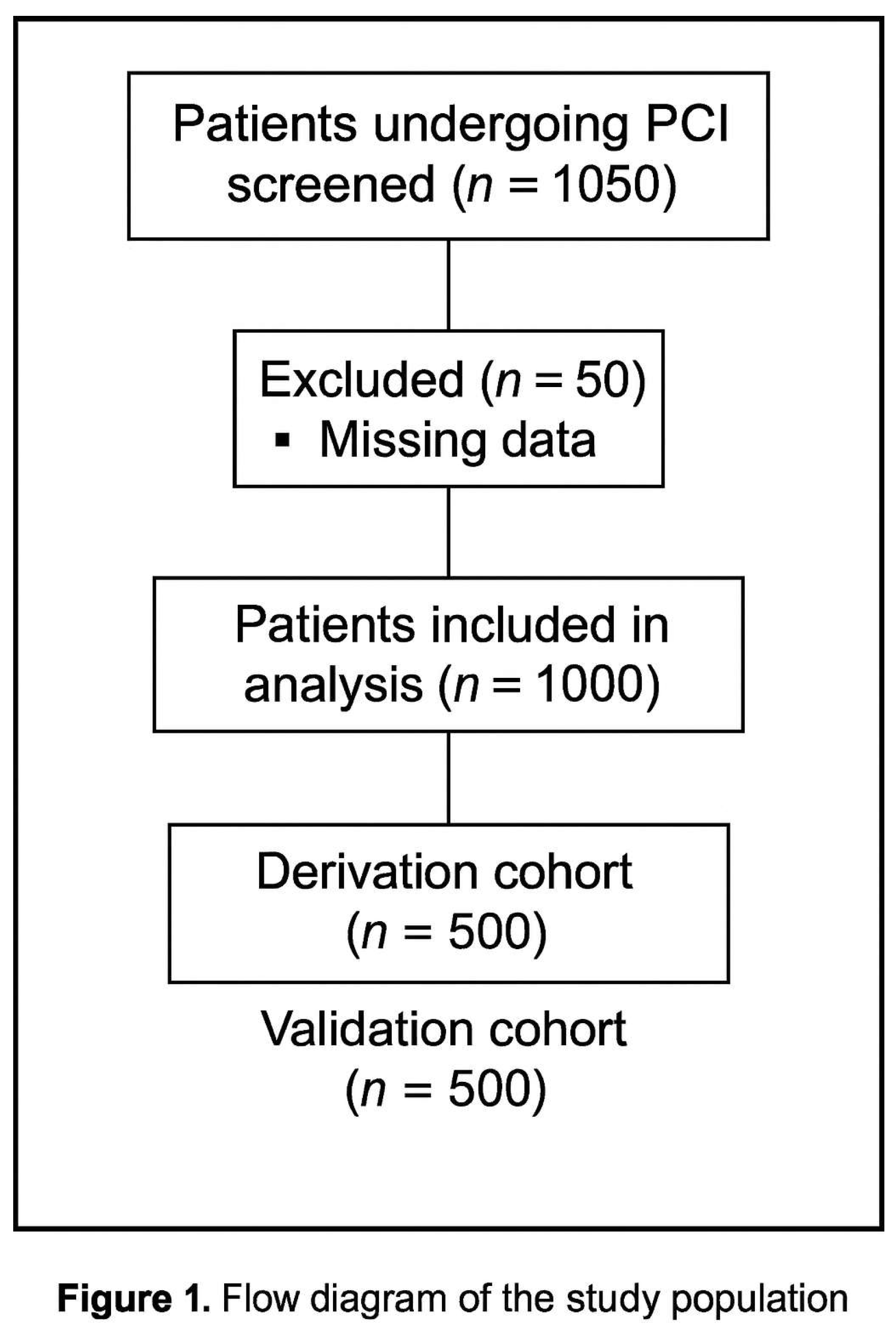

Study Population

- Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Clinical Evaluation

History

Physical Examination

- Class I: No heart failure.

- Class II: Rales or S3.

- Class III: Acute pulmonary edema.

- Class IV: Cardiogenic shock.

Investigations

- ECG: Baseline 12-lead ECG to identify ACS type (STEMI or NSTEMI) and dynamic changes.

- Echocardiography: Assessment of ejection fraction (EF ≤40% considered systolic heart failure) and other findings (e.g., hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, aortic plaque).

- Laboratory tests: HbA1c (DM: ≥6.5%), hemoglobin/hematocrit (anemia: <13 g/dL for men, <12 g/dL for women), serial cardiac biomarkers, and serum creatinine (baseline and daily up to 72 hours).

Angiographic and Procedural Details

Pre-Procedure

Intra-Procedural

- Unfractionated heparin (70–100 U/kg) was administered.

- Use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors and periprocedural hydration was left to operator discretion.

- Hypotension was defined as an SBP drop ≥20 mmHg to ≤90 mmHg.

Post-Procedure

Ethical Considerations

Statistical Analysis

- Categorical variables were expressed as counts and percentages.

- Derivation of the score: Variables with p <0.1 in univariate analysis (odds ratio) were entered into a multivariable logistic regression (backward stepwise method). Variables with p <0.05 were retained.

- A point-based scoring system was constructed using the Framingham method [19]:

- Binary variables were coded as 0/

- Each coefficient was normalized by dividing it by the smallest regression coefficient (Constant B).

- The resulting points were rounded to the nearest integer.

Score Validation

Data Cleaning and Handling of Missing Data

MENT Score Study—Results

Results

Discussion

Clinical Utility and Implications

Future Directions

Conclusion

Limitations

Data Sharing Statement

References

- Pugh CW, Dance DR, Khawaja AZ, et al. Risk models for predicting contrast-induced nephropathy in contemporary practice. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;16(4):375–386.

- Li M, Liu Y. A systematic review of contrast-induced acute kidney injury: mechanisms, risk factors, and clinical outcomes. Open J Nephrol. 2024;14(2):35–48.

- Brar, S.S.; Shen, A.Y.-J.; Jorgensen, M.B.; Kotlewski, A.; Aharonian, V.J.; Desai, N.; Ree, M.; Shah, A.I.; Burchette, R.J. Sodium Bicarbonate vs Sodium Chloride for the Prevention of Contrast Medium–Induced Nephropathy in Patients Undergoing Coronary Angiography. JAMA 2008, 300, 1038–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbieri, L.; Verdoia, M.; Marino, P.; Suryapranata, H.; De Luca, G. ; on behalf of the Novara Atherosclerosis Study Group Contrast volume to creatinine clearance ratio for the prediction of contrast-induced nephropathy in patients undergoing coronary angiography or percutaneous intervention. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2015, 23, 931–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caiazza, A.; Russo, L.; Sabbatini, M.; Russo, D. Hemodynamic and Tubular Changes Induced by Contrast Media. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berns, AS. Nephrotoxicity of contrast media. Kidney Int. 1989;36(4):730–40.

- Azzalini, L.; Spagnoli, V.; Ly, H.Q. Contrast-Induced Nephropathy: From Pathophysiology to Preventive Strategies. Can. J. Cardiol. 2016, 32, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lip GYH, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, Lane DA, Crijns HJ. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the Euro Heart Survey on Atrial Fibrillation. Chest. 2010;137(2):263–72.

- Bartlett RJ, McCullough PA, Mehran R, Brar SS, Gray WA, Hillege HL, et al. Consensus statement for the prevention of contrast-associated acute kidney injury. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14(6):622–34.

- Liu FD, Shen XL, Zhao R. Predictive role of CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores on stroke and thromboembolism in patients without atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Ann Med. 2016;48(5):367–75.

- Ipek, G.; Onuk, T.; Karatas, M.B.; Gungor, B.; Osken, A.; Keskin, M.; Oz, A.; Tanik, O.; Hayiroglu, M.I.; Yaka, H.Y.; et al. CHA2DS2-VASc Score is a Predictor of No-Reflow in Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Who Underwent Primary Percutaneous Intervention. Angiology 2016, 67, 840–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehran, R.; Aymong, E.; Nikolsky, E.; Lasic, Z.; Iakovou, I.; Fahy, M.; Mintz, G.; Lansky, A.; Moses, J.; Stone, G. A simple risk score for prediction of contrast-induced nephropathy after percutaneous coronary interventionDevelopment and initial validation. JACC 2004, 44, 1393–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee HJ, Kim S, Park JY, Bae SY, Han Y, Lim YH, et al. Biomarkers in contrast-induced nephropathy: advances in early detection and personalized risk assessment. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(7):2869.

- Jun T, Zhao L, Chen K, Li S, Zhou L, Li Y, et al. Prediction models for contrast-associated acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;6(3):e2310112.

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Fu, L.; Mei, C.; Dai, B.; Ashton, N. Efficacy of Short-Term High-Dose Statin in Preventing Contrast-Induced Nephropathy: A Meta-Analysis of Seven Randomized Controlled Trials. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e34450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killip, T.; Kimball, J.T. Treatment of myocardial infarction in a coronary care unit. Am. J. Cardiol. 1967, 20, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboyans V, Criqui MH, Abraham P, Allison MA, Creager MA, Diehm C, et al. Measurement and interpretation of the ankle-brachial index: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;126(24):2890–909.

- Neumann, F.-J.; Sousa-Uva, M.; Ahlsson, A.; Alfonso, F.; Banning, A.P.; Benedetto, U.; Byrne, R.A.; Collet, J.-P.; Falk, V.; Head, S.J.; et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Russ. J. Cardiol. 2019, 151–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan LM, Massaro JM, D’Agostino RB Sr. Presentation of multivariate data for clinical use: The Framingham Study risk score functions. Stat Med. 2004;23(10):1631–60.

- McCullough PA, Wolyn R, Rocher LL, Levin RN, O’Neill WW. Acute renal failure after coronary intervention: incidence, risk factors, and relationship to mortality. Am J Med. 1997;103(5):368–75.

- Iakovou, I.; Dangas, G.; Mehran, R.; Lansky, A.J.; Ashby, D.T.; Fahy, M.; Mintz, G.S.; Kent, K.M.; Pichard, A.D.; Satler, L.F.; et al. Impact of gender on the incidence and outcome of contrast-induced nephropathy after percutaneous coronary intervention. . 2003, 15, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marenzi, G.; Lauri, G.; Assanelli, E.; Campodonico, J.; De Metrio, M.; Marana, I.; Grazi, M.; Veglia, F.; Bartorelli, A.L. Contrast-induced nephropathy in patients undergoing primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. JACC 2004, 44, 1780–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtul, A.; Duran, M.; Yarlioglues, M.; Murat, S.N.; Demircelik, M.B.; Ergun, G.; Acikgoz, S.K.; Sensoy, B.; Cetin, M.; Ornek, E. Association Between N-Terminal Pro-Brain Natriuretic Peptide Levels and Contrast-Induced Nephropathy in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Acute Coronary Syndrome. Clin. Cardiol. 2014, 37, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelrahman A, Shen Y, Liu J, Huang J, Zhang L, Ma R, et al. Association of contrast volume with nephropathy risk: a personalized contrast dose strategy study. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):10935.

| Variable | N | % | |

| Age category | <65 years | 318 | 63.6% |

| 65-74 years | 146 | 29.2% | |

| >75 years | 36 | 7.2% | |

| + | 182 | 36.4% | |

| Sex | Female | 160 | 32.0% |

| Male | 340 | 68.0% | |

| Hypertension | - | 188 | 37.6% |

| + | 312 | 62.4% | |

| DM | - | 264 | 52.8% |

| + | 236 | 47.2% | |

| DVT | - | 492 | 98.4% |

| + | 8 | 1.6% | |

| TIA | - | 500 | 100.0% |

| + | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Stroke | - | 476 | 95.2% |

| + | 24 | 4.8% | |

| Aortic plaque | - | 500 | 100.0% |

| + | 0 | 0.0% | |

| PAD | - | 472 | 94.4% |

| + | 28 | 5.6% | |

| Old MI | - | 96 | 19.2% |

| + | 404 | 80.8% | |

| HCM | - | 500 | 100.0% |

| + | 0 | 0.0% | |

| NYHA III/IV | - | 440 | 88.0% |

| + | 60 | 12.0% | |

| EF ≤40% | - | 340 | 68.0% |

| + | 160 | 32.0% | |

| IABP | - | 498 | 99.6% |

| + | 2 | 0.4% | |

| Type of PCI | Secondary | 288 | 57.6% |

| Primary | 212 | 42.4% | |

| Contrast volume | <100 ml | 28 | 5.6% |

| 100 ml | 242 | 48.4% | |

| 200 ml | 182 | 36.4% | |

| 300 ml | 30 | 6.0% | |

| 400 ml | 14 | 2.8% | |

| 500 ml | 0 | 0.0% | |

| 600 ml | 4 | 0.8% | |

| Contrast volume ≥200 ml | - | 270 | 54.0% |

| + | 230 | 46.0% | |

| SBP ≤80 mmHg / Need for inotropes | - | 478 | 95.6% |

| + | 22 | 4.4% | |

| eGFR | ≥60 ml/min | 176 | 70.4% |

| 40 - <60 ml/min | 49 | 19.6% | |

| 20 - <40 ml/min | 15 | 6.0% | |

| <40 ml/min | 10 | 4.0% | |

| eGFR <60 ml/min | - | 352 | 70.4% |

| + | 148 | 29.6% | |

| Baseline creatinine >1.5 mg/dl | - | 432 | 86.4% |

| + | 68 | 13.6% | |

| Anemia | - | 334 | 66.8% |

| + | 166 | 33.2% | |

| CHA2DS2-VASc risk for CIN | Nil | 10 | 2.0% |

|

Low |

180 | 36.0% | |

| Moderate | 112 | 22.4% | |

| High | 124 | 24.8% | |

| Very high | 74 | 14.8% | |

| Mehran risk for CIN | Low | 284 | 56.8% |

| Moderate | 136 | 27.2% | |

| High | 74 | 14.8% | |

| Very high | 6 | 1.2% | |

| Creatinine rise ≥0.5 mg/dl | - | 440 | 88.0% |

| + | 60 | 12.0% | |

| Creatinine increase ≥25% above baseline | - | 394 | 78.8% |

| + | 106 | 21.2% | |

| Criteria for CIN | Nil (No CIN) | 382 | 76.4% |

| Creatinine rise ≥0.5 mg/dl only | 12 | 2.4% | |

| Creatinine rise ≥25% above baseline only | 58 | 11.6% | |

| Creatinine rise ≥0.5 mg/dl and ≥25% above baseline | 48 | 9.6% | |

| CIN (Creatinine rise ≥0.5 mg/dl or Creatinine increase ≥25% above baseline) | No CIN | 382 | 76.4% |

| CIN | 118 | 23.6% |

| Variable | No CIN (N=382) | CIN (N=118) |

Unadjusted odds ratio |

Z | p-value | ||||

| N | % | N | % | OR | 95% CI | ||||

| Age ≥65 years | - | 258 | 81.1% | 60 | 18.9% | 2.011 | 1.111 to 3.641 | 2.308 | 0.021 |

| + | 124 | 68.1% | 58 | 31.9% | |||||

| Male sex | - | 104 | 65.0% | 56 | 35.0% | 0.414 | 0.227 to 0.756 | 2.869 | 0.004 |

| + | 278 | 81.8% | 62 | 18.2% | |||||

| Hypertension | - | 158 | 84.0% | 30 | 16.0% | 2.069 | 1.077 to 3.975 | 2.183 | 0.029 |

| + | 224 | 71.8% | 88 | 28.2% | |||||

| DM | - | 228 | 86.4% | 35 | 13.6% | 3.372 | 1.805 to 6.301 | 3.812 | 0.0001 |

| + | 154 | 65.3% | 82 | 34.7% | |||||

| DVT | - | 376 | 76.4% | 116 | 23.6% | 1.081 | 0.110 to 10.587 | 0.0665 | 0.947 |

| + | 6 | 75.0% | 2 | 25.0% | |||||

| TIA | - | 382 | 76.4% | 118 | 23.6% | NC | - | - | - |

| + | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |||||

| Stroke | - | 362 | 76.1% | 114 | 23.9% | 0.635 | 0.135 to 2.984 | 0.575 | 0.565 |

| + | 20 | 83.3% | 4 | 16.7% | |||||

| Aortic plaque | - | 382 | 76.4% | 118 | 23.6% | NC | - | - | - |

| + | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |||||

| PAD | - | 370 | 78.4% | 102 | 21.6% | 4.837 | 1.605 to 14.573 | 2.801 | 0.005 |

| + | 12 | 42.9% | 16 | 57.1% | |||||

| Old MI | - | 76 | 79.2% | 20 | 20.8% | 1.217 | 0.565 to 2.621 | 0.502 | 0.616 |

| + | 306 | 75.7% | 98 | 24.3% | |||||

| HCM | - | 382 | 76.4% | 118 | 23.6% | NC | - | - | - |

| + | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |||||

| EF ≤40% | - | 276 | 81.2% | 64 | 18.8% | 2.197 | 1.203 to 4.012 | 2.562 | 0.010 |

| + | 106 | 66.3% | 54 | 33.8% | |||||

| IABP | - | 382 | 76.7% | 118 | 23.3% | 9.821 | 0.395 to 244.326 | 1.393 | 0.164 |

| + | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 100.0% | |||||

| NYHA III/IV | - | 342 | 77.7% | 98 | 22.3% | 1.745 | 0.766 to 3.973 | 1.326 | 0.185 |

| + | 40 | 66.7% | 20 | 33.3% | |||||

| Primary PCI | - | 234 | 81.3% | 54 | 18.8% | 1.874 | 1.040 to 3.378 | 2.089 | 0.037 |

| + | 148 | 69.8% | 64 | 30.2% | |||||

| Contrast volume≥200 ml | - | 220 | 81.5% | 50 | 18.5% | 1.847 | 1.023 to 3.334 | 2.035 | 0.042 |

| + | 162 | 70.4% | 68 | 29.6% | |||||

| SBP ≤80 mmHg | - | 378 | 79.1% | 100 | 20.9% | 17.010 | 3.562 to 81.238 | 3.552 | 0.0004 |

| + | 4 | 18.2% | 18 | 81.8% | |||||

| eGFR <60 ml/min | - | 284 | 80.7% | 68 | 19.3% | 2.131 | 1.158 to 3.922 | 2.431 | 0.015 |

| + | 98 | 66.2% | 50 | 33.8% | |||||

| Baseline creatinine >1.5 mg/dl | - | 346 | 80.1% | 86 | 19.9% | 3.576 | 1.686 to 7.584 | 3.323 | 0.001 |

| + | 36 | 52.9% | 32 | 47.1% | |||||

| Anemia | - | 274 | 82.0% | 60 | 18.0% | 2.453 | 1.346 to 4.468 | 2.932 | 0.003 |

| + | 108 | 65.1% | 58 | 34.9% | |||||

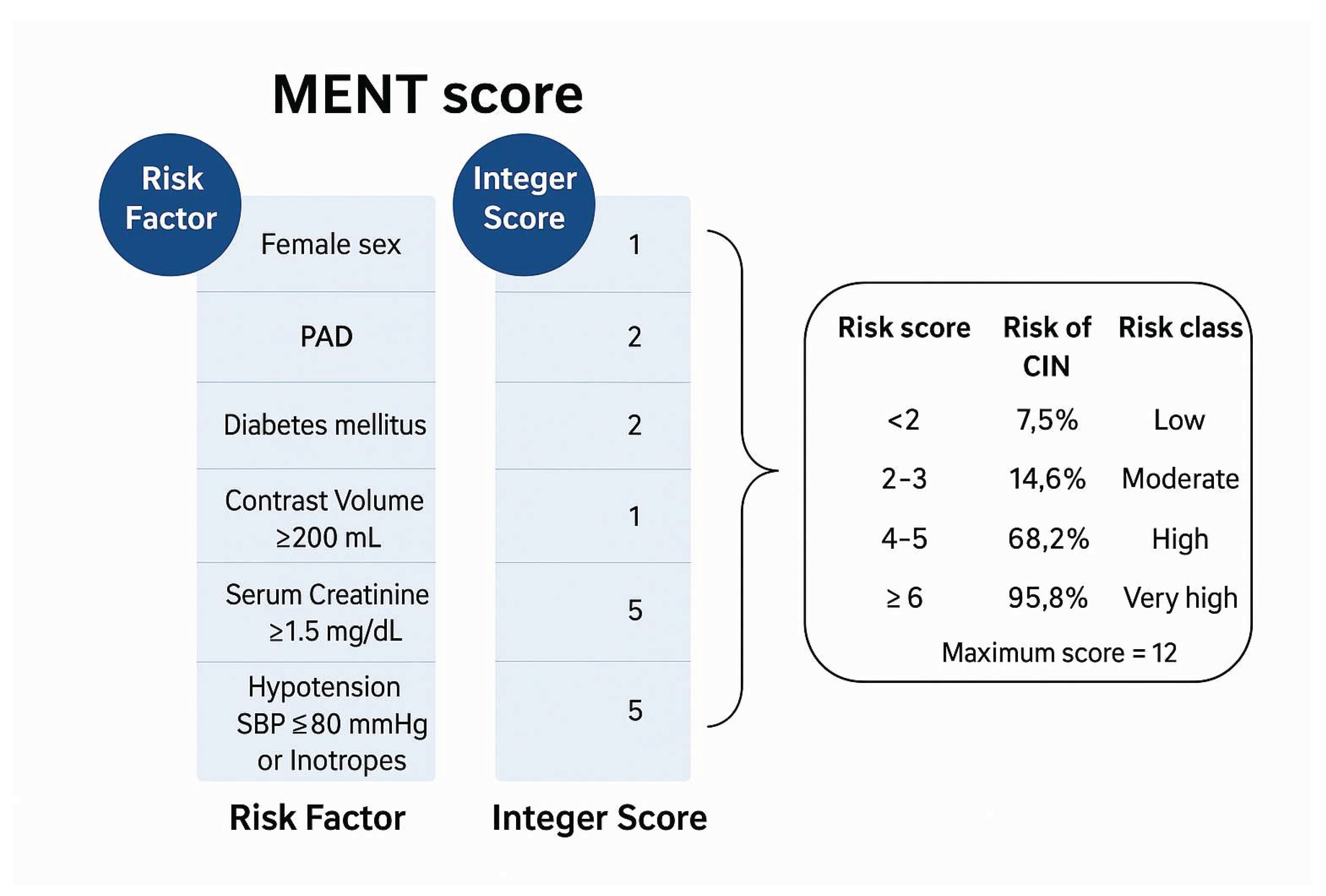

| Variable* | 95% CI for Exp (B) | |||||||

| B | SE | Wald | Df | p-value | Exp (B) | Lower | Upper | |

| Female sex (=1) | 0.918 | 0.352 | 6.824 | 1 | 0.009 | 2.505 | 1.258 | 4.989 |

| DM (=1) | 1.124 | 0.365 | 9.494 | 1 | 0.002 | 3.077 | 1.505 | 6.290 |

| PAD (=1) | 1.436 | 0.623 | 5.314 | 1 | 0.021 | 4.206 | 1.240 | 14.263 |

| Contrast volume ≥200 ml (=1) | 0.650 | 0.345 | 3.542 | 1 | 0.060 | 1.916 | 0.973 | 3.770 |

| SBP ≤80 mmHg or need for inotropes (=1) | 3.038 | 0.873 | 12.116 | 1 | 0.0005 | 20.864 | 3.771 | 115.426 |

| Baseline creatinine >1.5 mg/dl (=1) | 0.905 | 0.446 | 4.110 | 1 | 0.043 | 2.471 | 1.030 | 5.925 |

| Constant | -2.892 | 0.392 | 54.576 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.055 | ||

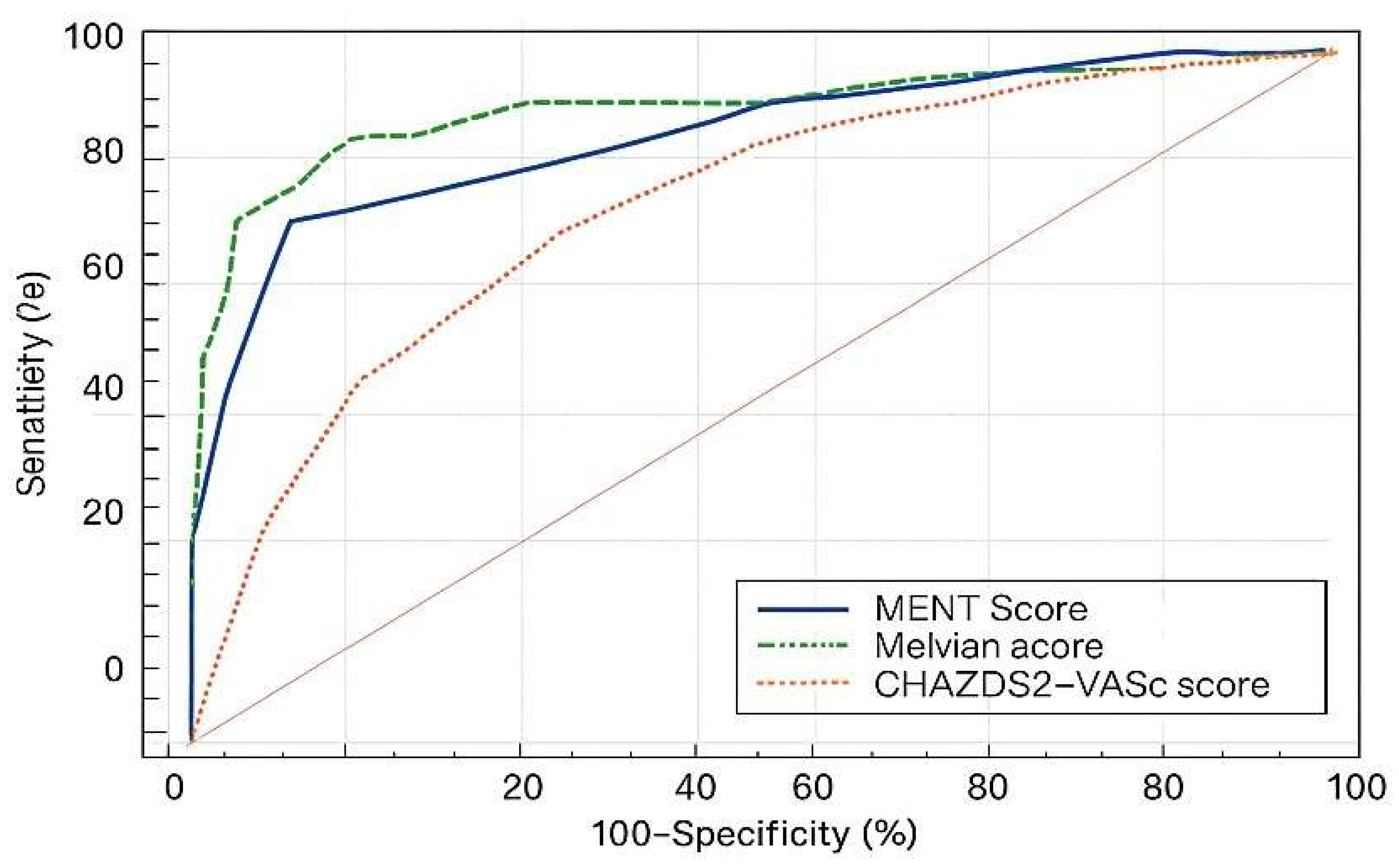

| Criterion | Sensitivity | 95% CI | Specificity | 95% CI | Youden index | Accuracy |

| >3 | 72.6 | 60.9 - 82.4 | 91.5 | 86.4 - 95.2 | 0.641 | 0.860 |

| New CIN Risk Score* | <2 | 2-3 | 4-5 | ≥6 |

| Risk class | Low | Moderate | High | Very high |

| Estimated risk of CIN | 7.5% | 14.6% | 68.2% | 95.8% |

| Variable |

AUC of study sample |

Variable |

AUC of validation sample |

| New CIN risk score | 0.770 | New CIN risk score | 0.861 |

| Mehran score | 0.737 | CHA2DS2-VASc score | 0.752 |

|

CHA2DS2- VASc score |

0.656 | Mehran score | 0.901 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).