1. Introduction

Stroke is a leading cause of mortality and morbidity.[

1] Fortunately, thrombolysis treatment for acute ischemic stroke was proven in 1995.[

2] This led healthcare systems to create pre-hospital stroke bypass systems, where emergency medical services (EMS) bypassed closer hospitals to take suspected stroke patients to hospitals capable of thrombolysis treatment. In 2015, there was a significant leap forward in the treatment of the most severe ischemic stroke patients, as a series of randomized controlled trials proved endovascular thrombectomy (EVT) to be highly efficacious.[

3,

4] This treatment is provided to patients with a target large vessel occlusion (LVO); approximately 30-40% of all ischemic strokes are due to a LVO.[

5] EVT is highly effective; approximately 26.9% of EVT treated stroke patients will recover with no disability compared to 12.9% of patients who did not receive EVT, or 46.0% of EVT treated patients will have only minor disability compared to 26.5% of patients who did not receive EVT.[

3] This results in a NNT (number needed to treat) for a reduction in disability of 2.6.[

6] Unfortunately, EVT requires specialized equipment and personnel, which limits its availability to larger centers. Patients that are eligible for EVT but arrive at a hospital that is only capable of thrombolysis need to be urgently transferred to the EVT center for treatment. This creates significant hurdles to provide EVT to transferred patients, as not only does the efficacy of treatment decay with time,[

7] but eligibility for EVT treatment also decays with time.[

8]

Eligibility for EVT is primarily determined using imaging; yet despite this there is uncertainty around how to best select patients for transfer from remote hospitals only capable of thrombolysis treatment to an EVT-capable center. A study from Ontario showed that 34% of stroke patients with LVO that were transferred for EVT from a peripheral site end up receiving EVT. In other words, there is great waste of resources with 66% of those transferred for EVT being deemed ineligible for the treatment upon arrival.[

9] Similar data from the US shows that only 27% of transferred patients received EVT.[

10] While over selecting patients for transfer to receive EVT may lead to a greater number of patients that will receive the treatment, this may also lead to a larger number of patients that turn out to be ineligible for treatment upon arrival. This essentially uses the philosophy of “casting a wide net”; however, over selection comes at a significant cost to the health care system due to the resources required for the urgent transport of a large proportion of severe stroke patients from a remote hospital to an EVT center for a patient who will ultimately not receive treatment, which is called a futile transfer. On the other hand, under selection or being more discriminant in selection results in missed cases and an overall lower number of patients from remote hospitals that will receive EVT, but the overall cost of transfer is lower since fewer patients are transferred.

Machine learning (ML) may be able to predict patients to transfer for EVT with information available at the time of decision making. ML is being increasingly used in stroke research. However, studies using ML have been limited to predicting outcomes based on patient demographic data, pre-morbidity and stroke feature such as stroke severity.[

11,

12,

13,

14] Some studies have used univariate analysis to assess predictors for EVT eligibility for patients arriving at an EVT capable center, [

15,

16] but not for transferred patients, and the effect of inter-hospital transfer as a single predictor of EVT eligibility has been studied from the receiving hospital perspective.[

17] Additionally, the application of ML has been explored to predict outcomes for acute stroke patients generally,[

18,

19,

20,

21,

22] to forecast the outcome of EVT treatment,[

23,

24,

25,

26] to interpret imaging in order to identify patients for treatment,[

27,

28,

29] to select older adults for EVT,[

30] and to help streamline the treatment process using in-hospital tracking system at an endovascular hospital.[

31]

In this study, we will apply ML to predict acute ischemic stroke patients with an LVO to transfer for EVT. The input variables will include information that is available at the time of transfer decision, and the response variable will be if EVT was performed. The objective of the study is to determine if ML can provide more accurate selection of patients to transfer for EVT.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context

The province of Nova Scotia in Canada is used as a case study for this research, which has a single universal health system. Nova Scotia is a small Canadian province of approximately one million people and a land size of 52,942 km2; a size that is similar to the European country of Slovakia and half the size of the US state of Virginia. Nova Scotia has a significant coastline of approximately 7500 km, which makes road transport often much longer than air transport. Nova Scotia has one EVT-capable center and ten centers that are only capable of thrombolysis treatment. A map of Nova Scotia with all 10 thrombolysis-only centers and the single EVT-capable center is shown on

Figure 1.

2.2. Data Collection

All ischemic stroke patients from Nova Scotia who were admitted to a hospital from January 1 2018 to December 31 2022 were identified using the provincial stroke registry. From these patients, those that arrived at one of the 10 thrombolysis centers and were subsequently transferred to the EVT-capable center within 24 hours of arrival were filtered. The variables from the registry used in this study are sex, age at time of stroke, and time from onset of stroke to CT at thrombolysis-only center, thrombolysis received. The time the patients left the thrombolysis-only center and the modality of transfer (ground or helicopter) were obtained from Nova Scotia Emergency Health Services (EHS), which is the single universal ambulance system for the province; the departure time was then used to obtain door-in-door-out time at the thrombolysis-only center. For these patients, the imaging from the thrombolysis-only centers were reread to obtain ASPECTS (Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score), thrombus location, and collateral status. For collateral status, a radiologist read the multi-phase CTA images from the thrombolysis centres and assessed the collaterals as good, intermediate, or poor. We also obtained the driving distance and Euclidean distance between each thrombolysis-only center and the EVT-capable center, and for distance we used the driving distance when the patient was transferred by ground ambulance and Euclidean distance when the patient was transferred by helicopter. The full list of variables is provided on

Table 1.

Patients that did not have an LVO were removed from the dataset, as they were transported for a reason other than EVT. Furthermore, patients with a posterior stroke were excluded, thus limiting the study to anterior ischemic stroke patients. The reason for this is because the clinical trials for EVT were limited to anterior stroke patients, and there is less evidence for EVT in posterior circulation stroke patients.[

32,

33]

2.3. Data Analysis

Supervised binary classification ML algorithms were applied to the dataset because the response variable of whether the patient received EVT is binary. The binary classification algorithms were applied to predict if the patient should be transferred for EVT. Four different supervised learning algorithms specializing in binary classification were applied along with an ensemble model to the preprocessed dataset: logistic regression, decision tree, random forest, and support vector machine (SVM). The ensemble model was built using a voting classifier that combines the four supervised models. These models account for data non-linearity, and they work reasonably well for small datasets that have a mix of numerical and categorical variables.

The data was split into training (80%) and testing (20%) with 5-fold cross-validation, which is a method that splits the dataset into 5 unique sets of 80-20 split. We train the model on each subsets and use the remaining subset as the testing set to evaluate the model. This process is repeated 5 times, and each subset is used as the testing set exactly once. Finally, the evaluation result is averaged over 5 trials. [

34]

Missing data were accounted by the K-Nearest Neighbour’s Algorithm (k-NN), a multi variate approach. It identifies k nearest neighbours for a missing data point from all complete instances in a dataset by calculating the Euclidean distance between them. The Euclidean distance calculates a straight line between the missing point and the other numbers, given by the following equation.

The k value in k-NN represents the number of neighbouring points that are considered for missing value imputation. In the case of a categorical variable, the missing datum is filled with the most frequent value occurring in the neighbours. Whereas for missing numerical variables, the missing information is imputed with the mean of the neighbours.[

35]

We performed hyperparameter tuning and balanced the class weights to prevent overfitting and biases and improve overall model performance. We used a grid search with a range of predefined values to find the optimal hyperparameters for all the models.

The accuracy of the models were determined by comparing the accuracy, ROC AUC (receiver operating characteristics area under the curve), F1 Score, and precision for all the models. We also ran each patient data through the model to determine if the model indicated that the patient was a candidate for transfer and compared this to the actual data. From this, the futile transfer rate is calculated for the model to compare with the actual data to determine if the model was able to reduce the futile transfer rate. A similar process was used to calculate the total rate of false negatives that the model outputted. A false negative has the greatest negative impact in the use of the ML for decision-making; therefore, we also compared the false negative rate for each model. A feature importance analysis was completed for the best two performing models. All hyperparameters that were selected for this study is provided in the supplementary table. All analyses was performed with Python version 3.2 using the following libraries: pandas, numpy, sklearn, matplotlib, and random.

2.4. Ethical Approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Nova Scotia Health Research Ethics Board (File Number: 1028274).

3. Results

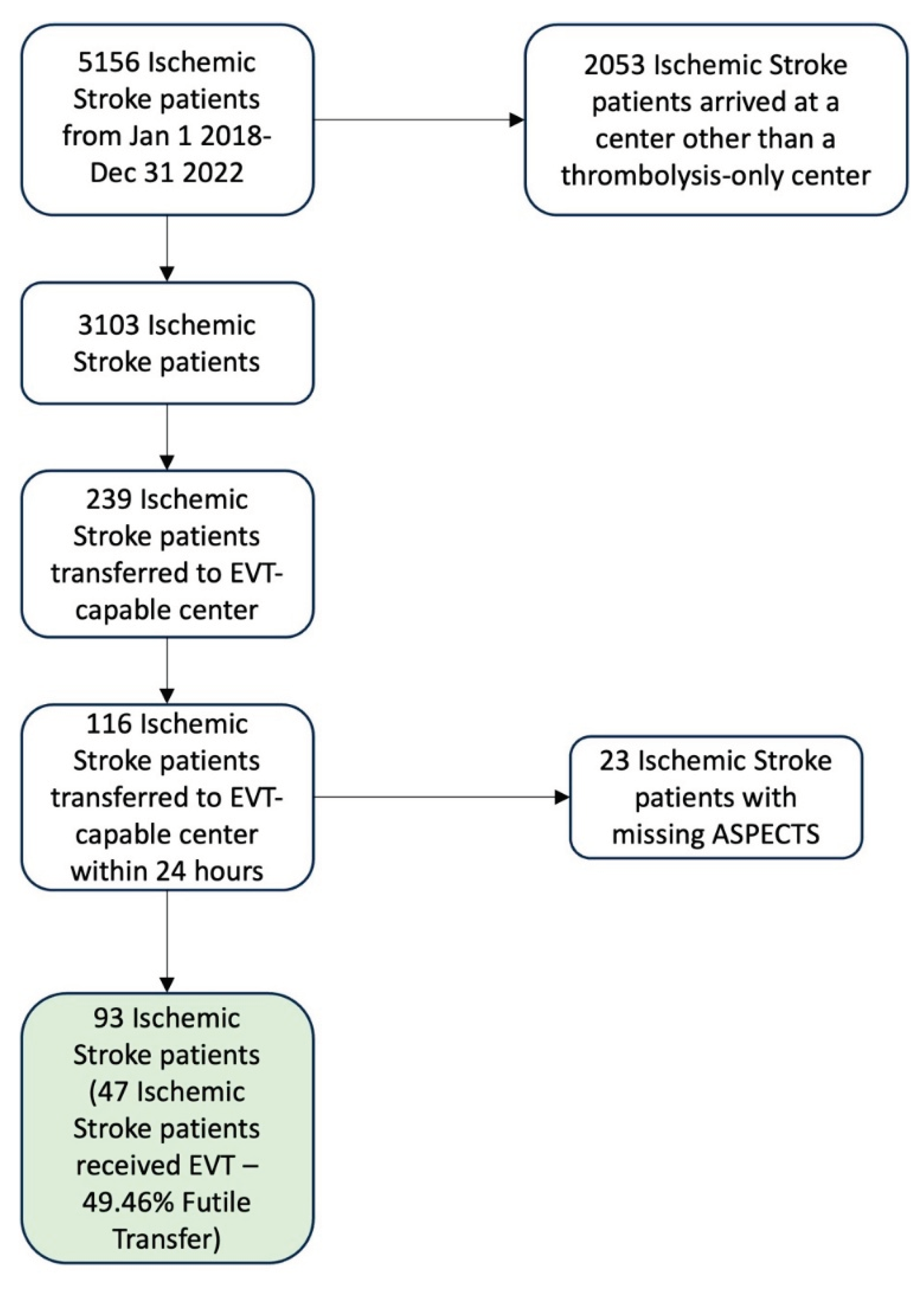

There were 5156 ischemic stroke patients identified in the Provincial Stroke Registry from January 1 2018 to December 31 2022. Out of these patients, 3103 arrived at one of the ten thrombolysis-only centers, and 239 of these patients were transferred to the EVT-capable center. There were 116 patients that were transferred within 24 hours, and 23 patients were missing ASPECTS, where 18 were because the thrombus was in a posterior circulation vessel. The final dataset had 93 patients. The total futile transfer rate for the final 93 records was 49.46% (46 patients were transferred without receiving EVT). The data exclusion and inclusion is shown on

Figure 2.

Descriptive statistics of the key parameters used in this study are provided in

Table 2. The data for the final dataset had 77 records (83%) with an ASPECTS of 8 to 10. The most common occlusion location was M1 with 37 records (40%) followed by 27 (29%) with a tandem or tandem ICA occlusion; there were 15 records (16%) with an M2 occlusion. Most of the patients had good collaterals 51 (55%), while only 8 (9%) had poor collaterals. There were 10 (10.75%) cases with where collaterals grading was not assessed; 3 (3.22%) with missing mode of transfer; 12 (12.90%) with missing door-in-door-out times.

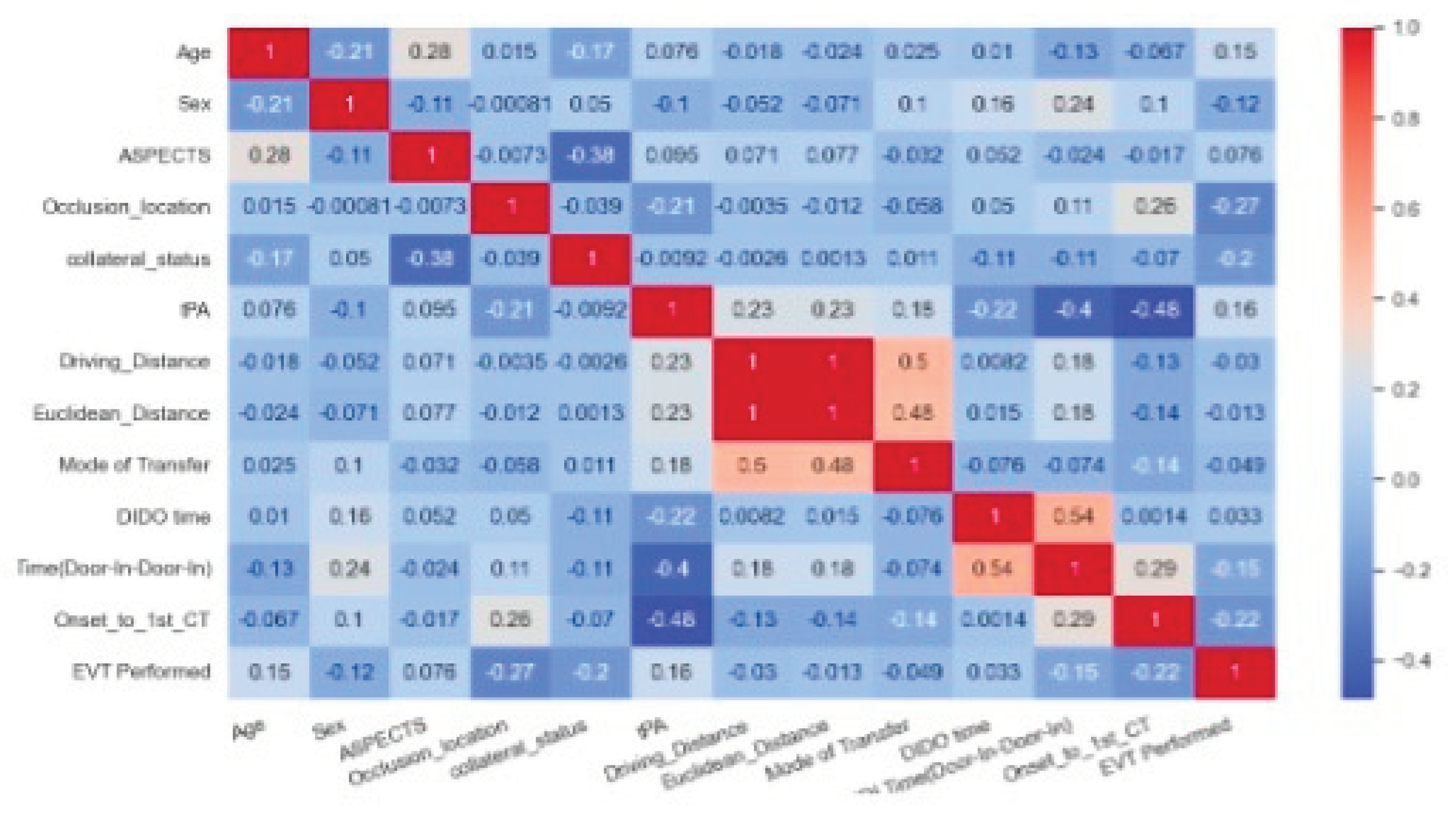

The correlation matrix is shown on

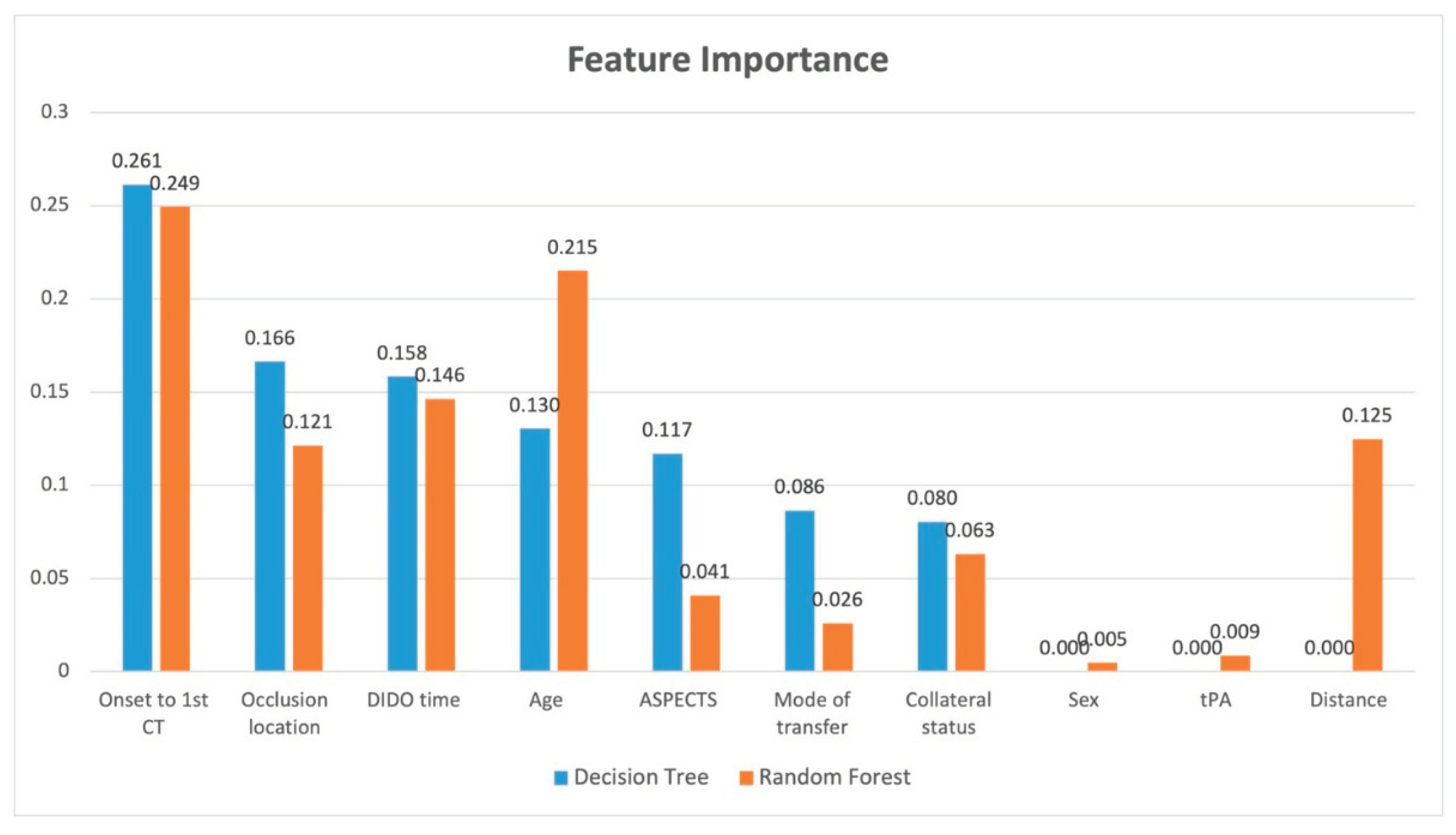

Figure 3. The highest correlation to receiving EVT was given by the occlusion location followed by onset-to-first-CT. In other words, shorter times from onset to CT were more favourable for transfer, and occlusion locations in the ICA and M1 vessels rather than M2 or MCA resulted in a more favourable transfer. The feature importance analysis for decision tree and random forest is provided in

Figure 4. The features that showed the greatest importantce in both models were onset to first CT time and DIDO time. Occlusion location was important in both models, but showed greater importance with decision tree. Conversely, age showed more importance with random forest. ASPECTS and mode of transfer showed greater importance with decision tree, while distance showed importance only with random forest.

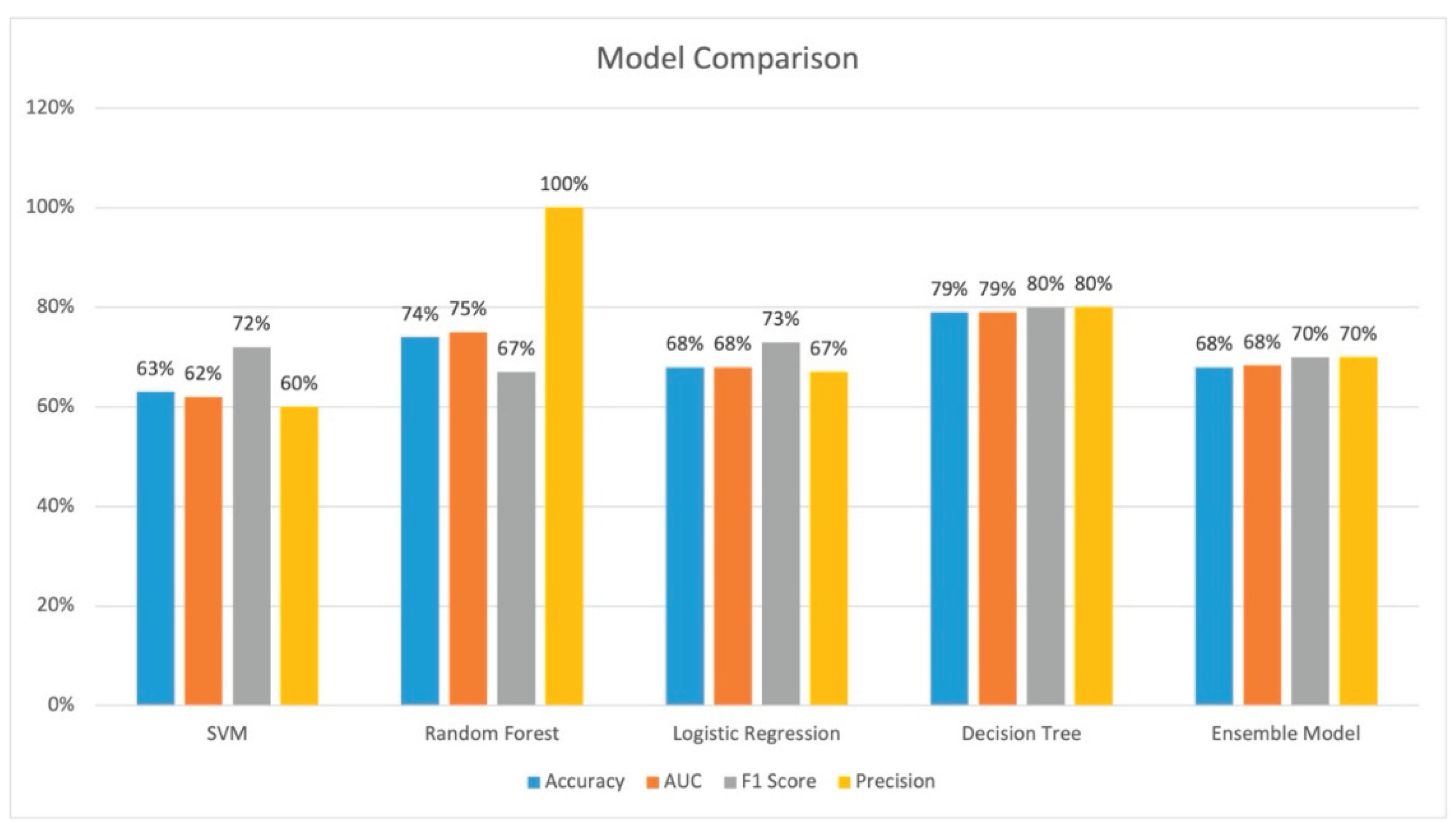

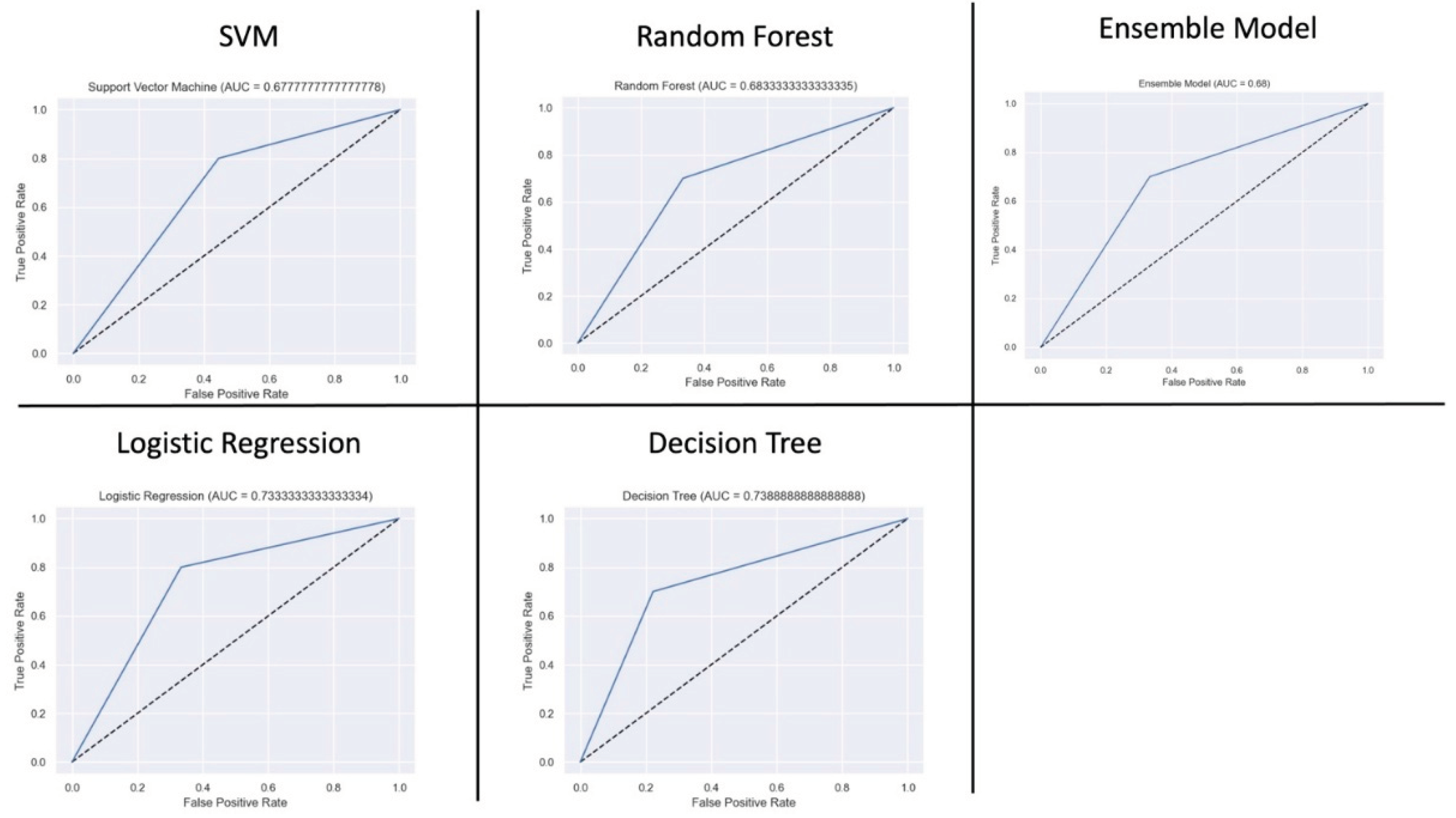

The performance of all models is provided on

Figure 5. Decision tree and random forest performed the best across all evaluation parameters. Decision tree had the best accuracy of 79.0%, an AUC of 79.0%, and precision of 80%. Random forest had an accuracy of 74%, an AUC of 75%, and a precision of 100%. The AUC curves is shown on

Figure 6. SVM had the worst performance.

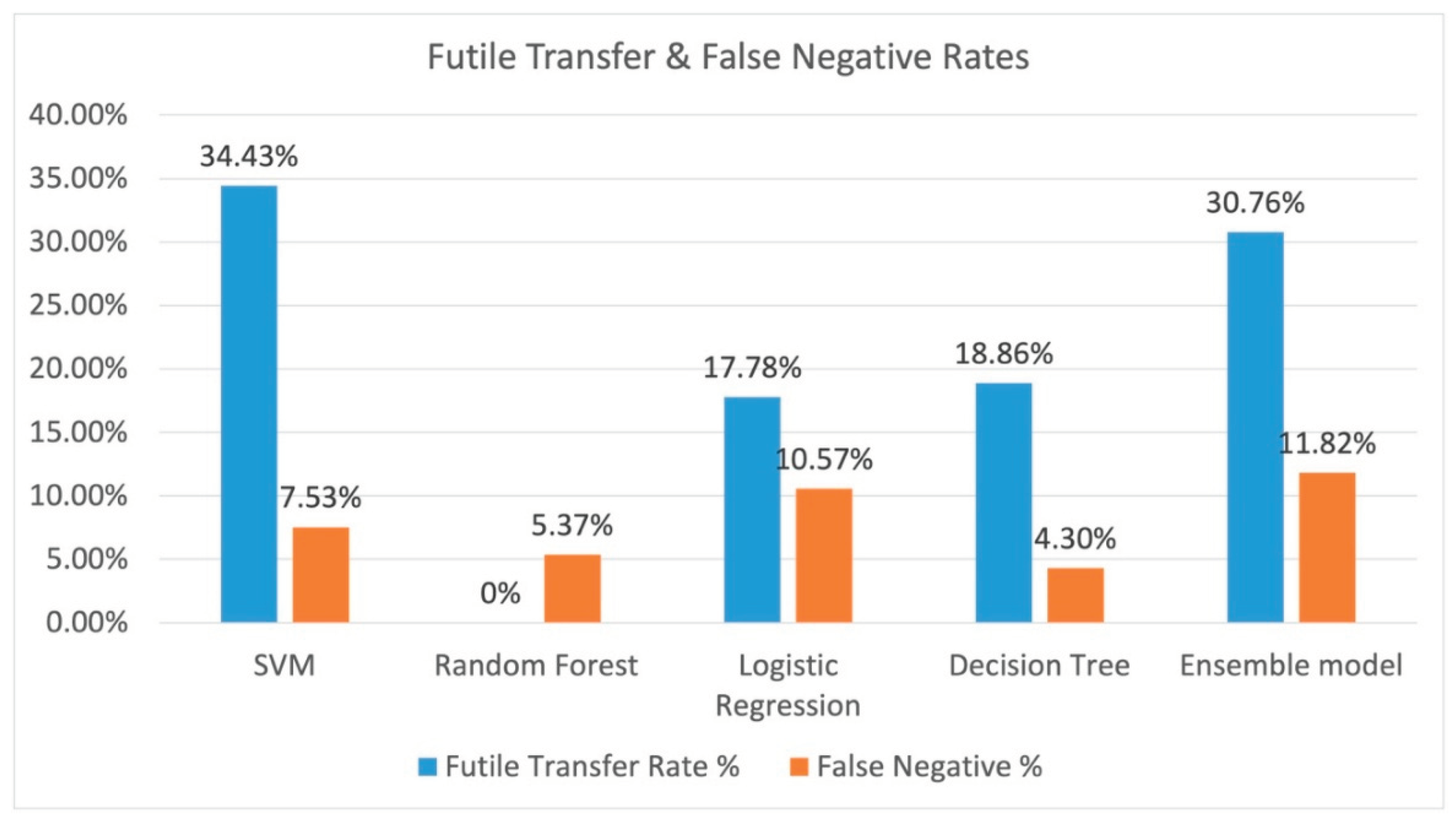

The resulting futile transfer rate (or those that the model indicated to transfer incorrectly) and the total false negative rate (the patient that should have been transferred out of the entire dataset) is shown on

Figure 7. Random forest performed the best with a 0% futile transfer rate, and random forest has a false negative rate of 5.37%. Decision tree had a futile transfer rate of 18.86%, and it had the lowest false negative rate of 4.3%.

4. Discussion

This case study with a small number of patients indicate that ML can potentially lower futile transfer rates. The decision tree model and the random forest model both had good performance with an accuracy of 79.0% and and 74% respectively. The futile transfer rate for the decision tree model and random rorest resulted in a 31.1% and 49.5% reduction of futile transfers respectively compared with physician decision alone; however, this comes as a cost of a 4.3% and 5.4% false negative rate respectively. This shows that a ML model can potentially provide decision support to physicians making EVT transfer decisions for acute ischemic stroke patients.

The feature importance analysis allows us to provide model explanation for the contribution of each feature. Both of these models show that the time from onset to first CT is most important along with the occlusion location. Upon review of the data with the feature importance information show us that ICA and M1 occlusion locations and onset to first CT time of less than 100 minutes tends to result in a favourable transfer. For longer onset to CT times, the patient should have good collateral status and a high ASPECTS score. Furthermore, the important of shorter DIDO times indicate that all thrombolysis centres should be working to reduce their transfer times to ensure favourable transfers for EVT.

There are likely missed patients in real world as well who should have been transferred for EVT (false negatives). This dataset does not account for potential patients that should have been transferred for EVT, but were not transferred. False negatives were not included in the dataset because it is difficult to assess which patients would have received the EVT procedure if they had been transferred, as it is difficult to predict their status upon arrival at the EVT center. Future studies should include patients who were not transferred.

Decision to treat patients with EVT is highly physician dependent.[

36] Some physicians are more aggressive with treating patients that are outside of known guidelines (e.g. low ASPECTS at the EVT center), while other physicians may be more conservative. Therefore, a ML model cannot account for these types of variations, but it may be well suited to provide decision support to physicians when making transfer decisions.

The outcome measure of receiving EVT for transferred patients has some limitations. The decision to treat a transferred patient with EVT is affected by information that is not available at the time of transfer, as additional information is obtained after arrival at the EVT centre. Examples of this includes: resolution of the stroke with thrombolysis, evolution to a symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, and additional information obtained about the patient’s pre-morbid status.

This study uses a small dataset of only 93 patients, and the results may shift significantly with changes to guidelines or other changes. This is partly because of the small population of Nova Scotia resulting in fewer patients that were transferred. Therefore, the results of this study can only provide a signal of whether ML can be used to develop software models to assist physicians with EVT transfer decisions. It is too early to use the Decision Tree model from this study to develop a decision support software application. Future studies with larger datasets are needed to further validate this study and to develop a more robust model that can then be used in a decision support software application. Furthermore, the NIHSS variable could not be used in our model due to a large number of missing values, which is potentially a strong predictor of patients to transfer for EVT. A future study should include this variable in the dataset. Additionally, this data is limited to a single health system with a single EVT center. The generalizability of these results to other health systems that may have multiple EVT centers is unknown.

5. Conclusions

The Decision Tree ML model resulted in over 31-49% fewer futile transfers with a cost of 4.3-5.4% false negatives. ML models can potentially be used to develop decision support software applications for EVT transfer decision making. However, future studies are needed with larger datasets and in different health systems to create a more robust model that can be generalized to other health systems.

Author Contributions

NK, EAC, JG, PF, MDH, and J N-S all provided input into the study design. BT and EAC assisted with collecting imaging data. JG provided transfer data. AD provided data cleaning and analytic support. J-HH and SA developed the ML models and conducted the analyses. SA provided assistance with ML methodology. NK drafted the original manuscript and held funding. All authors provided editorial input into the manuscript.

Funding

Funding for this project is provided by the Nova Scotia Health Research Fund 2022 (Account # 894025).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Nova Scotia Health Research Ethics Board (File Number: 1028274).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the impracticability due to a large sample size, loss of study participants due to relocation or death, and lack of continuing relationship between participants.

Conflicts of Interest

NK is part-owner of DESTINE Health Inc.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EMS |

Emergency medical services |

| EVT |

Endovascular thrombectomy |

| LVO |

Large vessel occlusion |

| NNT |

Number needed to treat |

| ML |

Machine learning |

| ASPECTS |

Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score |

| k-NN |

K-nearest neighbour |

| ROC |

Receiver operating characteristics |

| AUC |

Area under the curve |

| DIDO |

Door-In-Door-Out |

References

- Feigin, V.L. , Forouzanfar, M.H., Krishnamurthi, R., Mensah, G.A., Connor, M., Bennett, D.A., Moran, A.E., Sacco, R.L., Anderson, L., Truelsen, T. and O’Donnell, M. Global and regional burden of stroke during 1990–2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet 2014, 383, 245–255. [Google Scholar]

- The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke RT-PA stroke study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 1995, 333, 1581–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, M. , Menon B.K., Van Zwam W.H., Dippel D.W., Mitchell P.J., Demchuk A.M., Dávalos A., Majoie C.B., van der Lugt A., De Miquel M.A., Donnan G.A., et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. The Lancet 2016, 387, 1723–1731. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, M. , Demchuk A.M., Menon B.K., Eesa M., Rempel J.L., Thornton J., Roy D., Jovin T.G., Willinsky R.A., Sapkota B.L., Dowlatshahi D., et al. Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. NEJM 2015, 372, 1019–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, K. , Gornbein J., Saver J.L. Ischemic strokes due to large-vessel occlusions contribute disproportionately to stroke-related dependence and death: a review. Frontiers in neurology 2017, 8, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal M, Menon B. K., van Zwam W.H., Dippel D.W., Mitchell P.J., Demchuk A.M., Dávalos A., Majoie C.B., van der Lugt A., De Miquel M.A., Donnan G.A. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. The Lancet 2016, 387, 1723–1731. [Google Scholar]

- Saver, J.L. , Goyal M., Van der Lugt A.A., Menon B.K., Majoie C.B., Dippel D.W., Campbell B.C., Nogueira R.G., Demchuk A.M., Tomasello A., Cardona P. Time to treatment with endovascular thrombectomy and outcomes from ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2016, 316, 1279–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saver, J.L. Time is brain—quantified. Stroke 2006, 37, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.M. , Wang J.Z., Liao J., Reiter S.D., Vyas M.V., Linkewich E., Swartz R.H., da Costa L., Kassardjian C.D., Amy Y.X. Delayed Thrombectomy Center Arrival is Associated with Decreased Treatment Probability. CJNS 2020, 47, 770–774. [Google Scholar]

- Regenhardt, R.W. , Mecca A.P., Flavin S.A., Boulouis G., Lauer A., Zachrison K.S., Boomhower J., Patel A.B., Hirsch J.A., Schwamm L.H., Leslie-Mazwi T.M. Delays in the air or ground transfer of patients for endovascular thrombectomy. Stroke 2018, 49, 1419–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girot, J.B. , Richard S., Gariel F., Sibon I., Labreuche J., Kyheng M., Gory B., Dargazanli C., Maier B., Consoli A., Daumas-Duport B. Predictors of unexplained early neurological deterioration after endovascular treatment for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2020, 51, 2943–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, Y. , Yamagami H. , Sakai N., Yoshimura S. Predictors of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage after endovascular therapy in acute ischemic stroke with large vessel occlusion. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2017, 26, 766–771. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ozdemir O,, Giray S,, Arlier Z,, Baş D,F,, Inanc Y,, Colak E. Predictors of a good outcome after endovascular stroke treatment with stent retrievers. The Scientific World Journal 2015.

- Nagaraja, N. , Olasoji E. B., Patel U.K. Sex and racial disparity in utilization and outcomes of t-PA and thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2020, 29, 104954. [Google Scholar]

- Nannoni, S. , Strambo D., Sirimarco G., Amiguet M., Vanacker P., Eskandari A., Saliou G., Wintermark M., Dunet V., Michel P. Eligibility for late endovascular treatment using DAWN, DEFUSE-3, and more liberal selection criteria in a stroke center. JNIS 2020, 12, 842–847. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vanacker, P. , Lambrou D., Eskandari A., Mosimann P.J., Maghraoui A., Michel P. Eligibility and predictors for acute revascularization procedures in a stroke center. Stroke 2016, 47, 1844–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venema E, Groot A. E., Lingsma H.F., Hinsenveld W., Treurniet K.M., Chalos V., Zinkstok S.M., Mulder M.J., de Ridder I.R., Marquering H.A., Schonewille W.J. Effect of interhospital transfer on endovascular treatment for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2019, 50, 923–930. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y. , Bengio Y., Hinton G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine learning 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaka, S.A. , Menon B.K., Brobbey A., Williamson T., Goyal M., Demchuk A.M., Hill M.D., Sajobi T.T. Functional outcome prediction in Ischemic stroke: a comparison of machine learning algorithms and regression models. Frontiers in neurology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J. , Yoon J.G., Park H., Kim Y.D., Nam H.S., Heo J.H. Machine learning–based model for prediction of outcomes in acute stroke. Stroke 2019, 50, 1263–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, G. , Liu W., Wang L. A machine learning approach to select features important to stroke prognosis. Computational Biology and Chemistry 2020, 88, 107316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadi, H. , Dowling R., Yan B., Mitchell P. Machine learning for outcome prediction of acute ischemic stroke post intra-arterial therapy. PloS one 2014, 9, e88225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Os, H.J. , Ramos L.A., Hilbert A., Van Leeuwen M., van Walderveen M.A., Kruyt N.D., Dippel D.W., Steyerberg E.W., van der Schaaf I.C., Lingsma H.F., Schonewille W.J. Predicting outcome of endovascular treatment for acute ischemic stroke: potential value of machine learning algorithms. Frontiers in neurology 2018, 9, 784. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brugnara, G. , Neuberger U., Mahmutoglu M.A., Foltyn M., Herweh C., Nagel S., Schönenberger S., Heiland S., Ulfert C., Ringleb P.A., Bendszus M. Multimodal predictive modeling of endovascular treatment outcome for acute ischemic stroke using machine-learning. Stroke 2020, 51, 3541–3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, Y.H. , Lim I.C., Tseng F.S., Teo Y.N., Kow C.S., Ng Z.H., Ko N.C., Sia C.H., Leow A.S., Yeung W., Kong W.Y. Predicting Clinical Outcomes in Acute Ischemic Stroke Patients Undergoing Endovascular Thrombectomy with Machine Learning. Clinical Neuroradiology 2021, 1–0. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, W. , Kuang H., Teleg E., Ospel J.M., Sohn S.I., Almekhlafi M., Goyal M., Hill M.D., Demchuk A.M., Menon B.K. Machine learning for detecting early infarction in acute stroke with non–contrast-enhanced CT. Radiology 2020, 294, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, H. , Najm M. , Chakraborty D., Maraj N., Sohn S.I., Goyal M., Hill M.D., Demchuk A.M., Menon B.K., Qiu W. Automated ASPECTS on noncontrast CT scans in patients with acute ischemic stroke using machine learning. American journal of neuroradiology 2019, 40, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H. , Lee E.J., Ham S., Lee H.B., Lee J.S., Kwon S.U., Kim J.S., Kim N., Kang D.W. Machine learning approach to identify stroke within 4.5 hours. Stroke 2020, 51, 860–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawieh, A. , Zaraket F., Alawieh M.B., Chatterjee A.R., Spiotta A. Using machine learning to optimize selection of elderly patients for endovascular thrombectomy. JNIS 2019, 11, 847–851. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, D.Z. , Yeo M., Dahan A., Tahayori B., Kok H.K., Abbasi-Rad M., Maingard J., Kutaiba N., Russell J., Thijs V., Jhamb A. Development of a machine learning-based real-time location system to streamline acute endovascular intervention in acute stroke: a proof-of-concept study. JNIS 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Baik, S.H. , Kim J.Y., Jung C. A review of endovascular treatment for posterior circulation strokes. Neurointervention 2023, 18, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirson, F.A. , Boodt N., Brouwer J., Bruggeman A.A., den Hartog S.J., Goldhoorn R.J., Langezaal L.C., Staals J., van Zwam W.H., van der Leij C., Brans R.J. Endovascular treatment for posterior circulation stroke in routine clinical practice: results of the multicenter randomized clinical trial of endovascular treatment for acute ischemic stroke in the Netherlands registry. Stroke 2022, 53, 758–768. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.H. . Machine learning. Springer Nature 2021, Aug 20.

- Zhang, S. Nearest neighbor selection for iteratively kNN imputation. Journal of Systems and Software 2012, 85, 2541–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashani, N. , Ospel J.M., Menon B.K., Saposnik G., Almekhlafi M., Sylaja P.N., Campbell B.C., Heo J.H., Mitchell P.J., Cherian M., Turjman F. Influence of guidelines in endovascular therapy decision making in acute ischemic stroke: insights from UNMASK EVT. Stroke 2019, 50, 3578–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).