1. Introduction

Solar mirrors play a crucial role in concentrating sunlight for various applications, such as solar power generation and industrial processes [

1]. However, the efficiency of these mirrors can be significantly compromised by accumulation of dirt, dust, and other contaminants on their surfaces, leading to reduced reflectivity and overall performance [

2]. To address this challenge, the development of advanced surface coatings, known as self-cleaning, has gained prominence in the field of solar mirror technology [

3]. A lot of materials specifically designed to modulate wettability (for reducing water consumption in washing maintenance operations) ensuring optimal reflectivity and sustained energy capture over time have been proposed on a laboratory scale, or on an intermediate scale of the small prototype [

4]. No one of these coatings has reached the commercial state for different reasons: passing from a laboratory scale to industrial one is not a simple task when there are strict optical requisites to be considered, the external positioning of covered mirrors determines degradation of the exposed layer, and above all, adding a further step to existing production lines of solar mirrors has to be evaluated in economic terms as trade-off between its cost and real benefits in terms of performance [

5]. This last aspect of the economic evaluation of water saving in ordinary solar field maintenance operations is difficult because each site has its own peculiarities, that make comparison and an absolute evaluation difficult, but which nevertheless allow to draw an indication of the fact that any water saving, especially in desert areas, is always profitable [

6]. In a previous work it has been explored the feasibility of changing alumina, that is the most diffuse last layer in all mirror architectures, with AlN compounds obtained by means of sputtering deposition [

7].

Different auxetic AlN politypoids have been fabricated with the purpose of tailoring wettability (from 52° to 100 °WCA due to major covalent character of Al-N bond with respect to Al-O one), preserving optical clarity in the desired solar range and granting durability over time in consideration of inorganic nature of AlN.

Such promising results have been obtained on a laboratory scale but conceived for a following scaling-up in consideration of the fact that they are produced with an intrinsically scalable technique.

Often, although research products studied on a laboratory scale exhibit interesting properties, their effective utilization in a real world requires a lot of applied research, devoted to verifying if the same properties obtained on the small scale can be preserved when dimensional and performance requirements have to be satisfied. The first problem to solve is the selection of a fabrication technique that grants the same chemical-physical properties of the small case. For example, in case of polymeric products this occurs with coating obtained on the lab scale by means of spinning that is a clearly non scalable technique and it has to be necessary changed.

This work aims to extend the fabrication of inorganic self-cleaning auxetic and transparent aluminum nitrides coatings, selected among the family of materials previously developed with sputtering processes, from laboratory to pre-industrial scale to the purpose of uniformly covering 50 cm x 40 cm prototypes, useful to be tested as BSM solar mirrors in the demonstrative CSP Fresnel plant, named ENEASHIP and located in Casaccia (Rome) ENEA research centre. When a plant component, like a solar mirror, is modified by means of adding another layer (e.g. a self-cleaning layer) the testing of its performance on field is crucial. Not even a coating material that is stable indoor or in climatic chamber testing campaign preserves its performance when positioned outdoor exposed to adverse and in any case variable weather conditions for a long time. For this reason, tests on field of solar mirrors prototypes stability and performance are part of this work.

2. Materials and Methods

AlN layers have been deposited by sputtering technique using a proprietary multi-cathode sputtering apparatus equipped with magnetron and dual magnetron cathodes operating in DC or pulsed DC and in medium frequency mode, respectively. The mirror substrate has been positioned in front of the target in a planar configuration and the fabrication process has been a reactive sputtering at Ar+N2 pressure of 3 Pa with power supplied to Al cathode of 1800W.

Silicon substrates for homogeneity tests have been purchased by Merk SpA.

Solar mirrors of 50x40x1cm have been purchased by Società vetraria biancaldese Spa.

UV-VIS-NIR analysis has been performed using a double beam Perkin-Elmer mod. Lambda 900 instrument, equipped with a 15 cm integrating sphere to measure global spectral reflectance and transmittance. Vibrational analysis of materials has been performed by means of micro-RAMAN and Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) FTIR techniques. FTIR spectra have been recorded with a Bruker Fourier transform spectrometer model Equinox 55, equipped with a Deuterated triglycine sulphate detector operating in the 400–4000 cm−1 range with 4 cm−1.resolution and a MCT detector operating in the 560–8000 cm−1 with 8 cm−1 resolution. Raman spectra have been collected with a Renishaw visible Raman spectrometer system, equipped with a confocal microscope. Laser excitation at 514 nm (green) was supplied by a YAG double-diode pumped laser (20 mW). The Static Water Contact Angle (WCA) was measured with the direct optical method of drop-shape analysis, by means of the contact angle meter KRUSS DSA-100.

Tests on field have been performed on prototypes obtained gluing coated mirrors panels on BSM commercial constitutive mirrors (as better explained in following paragraphs) outdoor in the demonstrative Fresnel plant ENEASHIP, located in Casaccia (Rome) ENEA research center. Reflectance measurements on site have been performed by means of a portable D&S R15-USB, averaging 3 values for each 50x40 panel and 9 values for the entire solar mirror.

3. Results

For obtaining self-cleaning solar mirrors of big dimensions that can be positioned in a real CSP plant two important aspects have been studied and described in the following paragraphs: the scaling-up from laboratory to pre-industrial scale of the magnetron sputtering fabrication process of auxetic AlN (3.1) and the testing outdoor of fabricated prototypes (3.2).

3.1. Scaling-Up

The scaling-up from laboratory scale to pre-industrial one requires the optimization of magnetron sputtering processes for obtaining on a large scale auxetic AlN coatings with the desired performance in terms of optical and wettability properties by means of robust and repeatable procedures.

In a previous work we described a family of AlN politypoids fabricated by means of magnetron sputtering on 3x7 cm mirror substrates, using the tubular geometry of ENEA2 proprietary apparatus and demonstrating that auxetic phases simulated from Kilic and colleagues [

8] can be experimentally obtained, both working on a saturation and on a transition regimen of aluminum target, doping the hexagonal AlN lattice with metals (Al or Ag) or Oxygen.

Among such interesting family of materials, the criterion for fabricating a prototype has been selecting the most transparent in UV-VIS-NIR and with higher WCA° material, obtainable by means of a stable, robust and advantageous process and then to scale up it for obtaining the maximum dimensions possible with proprietary apparatus in dotation of applied research laboratory. In particular, the reactive sputtering of aluminum with nitrogen in transition regime has been preferred to the saturation one because the deposition rate is higher and occurs at low energy and low target consumption, at the same time preserving stability and repeatability of a production process. So, the selected starting experimental conditions to scale up have been: power supplied to the Aluminum target 1500 W, p=1.0 × 10−3 mbar, gas flows: 200 sccm Ar + 25 sccm N2 and last but not least process on the laboratory scale performed with a rotating holder.

Here the main goal of the work has been to reproduce on a planar arrangement the same material property. In general, the sputtering deposition process involves many parameters, which introduce different complexities. The pre-industrial ENEA 2 plant allows the processing of a maximum of 500x400 mm substrate in planar configuration, but to do this, the sample housing has to be replaced, removing the tubular sample holder (designed to fabricate the receiver tubes of a solar CSP plant [

9] and utilized for the previous experiments on auxetics) and redefining process conditions such that the deposition on a flat plate reproduces the optical properties of the samples obtained on the small rotating flat substrates typically housed in tubular sample holders. Since Fresnel implants have mirrors with a slightly concave geometry and are equipped with a secondary concentrator, it is still possible to widen the range of the angle of acceptance of the reflected radiation, which translates into less stringent requirements on coating roughness, thickness uniformity and specularity component.

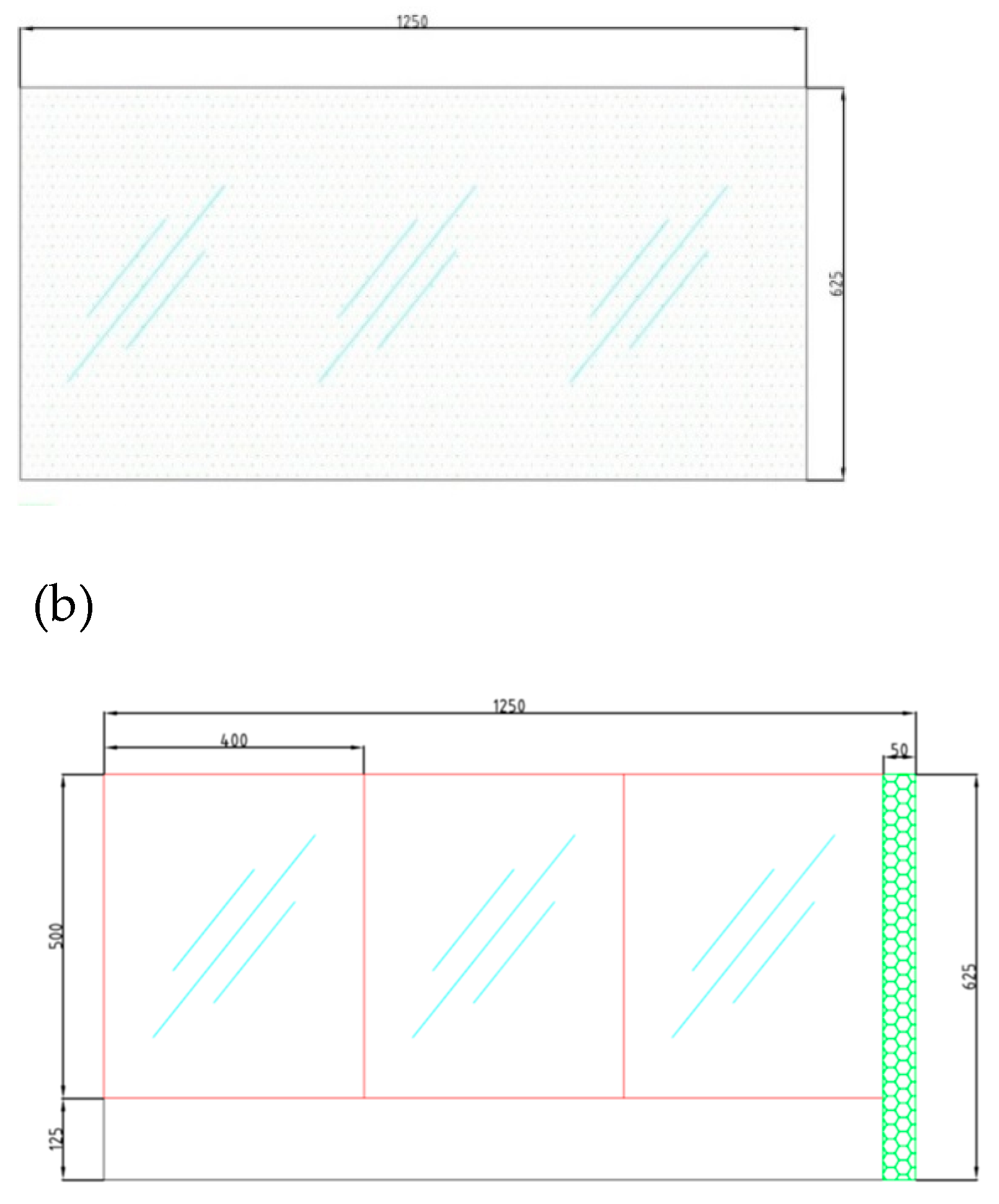

Figure 1 shows a photo of the flat plate with the mirror mounted, using the modification. This operation carried out on a support (the carrier) that must interact with a plasma is not trivial at all. The modification, if not carefully studied, can destabilize the plasma that is generated during the process, triggering discharges that affect uniformity and, in some cases, cause it to shut down.

The maximum operable dimension is 50x 40 cm but being target dimension only 20 cm it is conceivable a not uniform coverture.

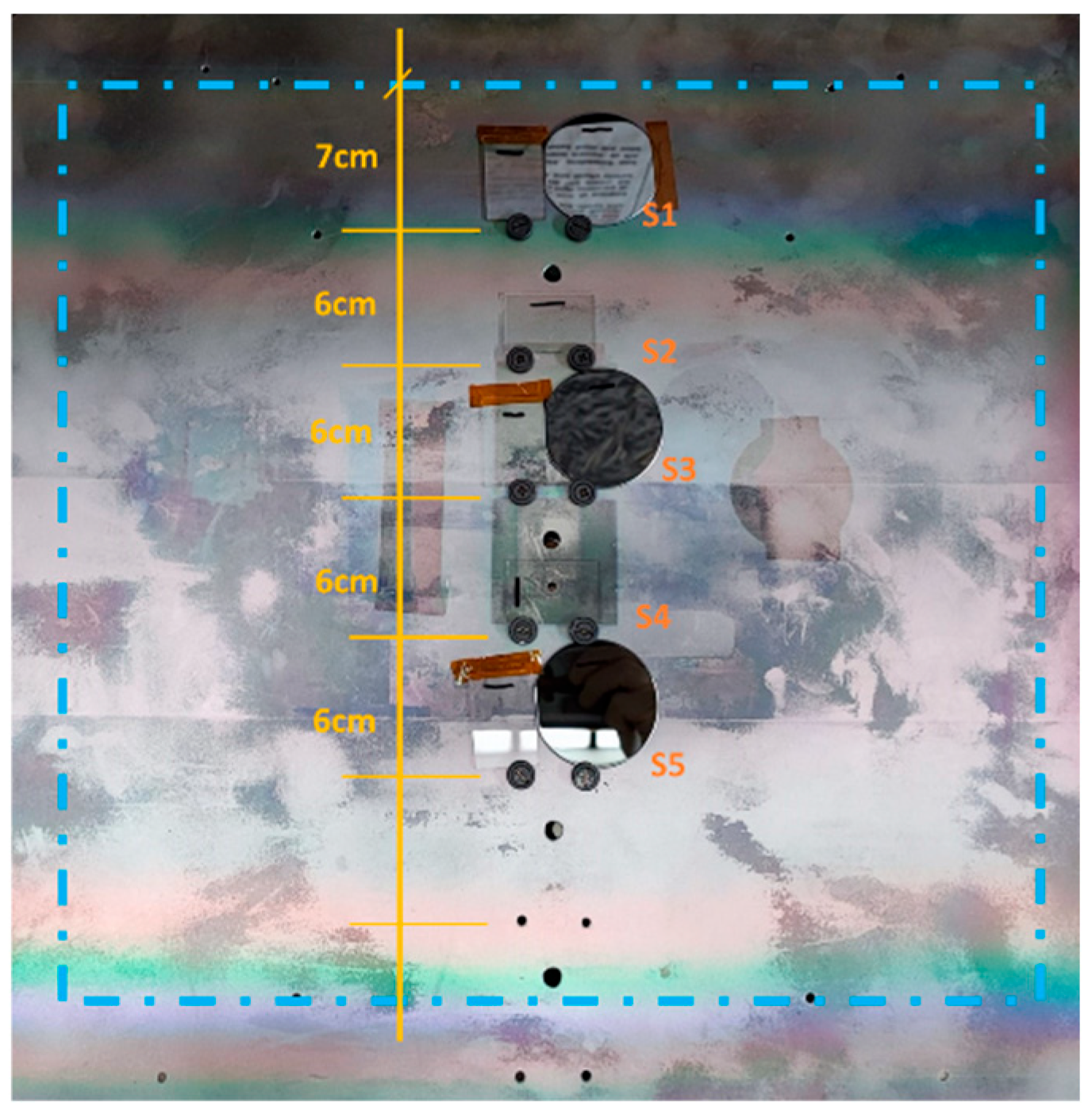

For studying the properties of thin films at different heights on the holder during the sputtering process five silicon test substrates have been positioned at distances of 6 cm each other inside the frame of the mirror position, as shown in

Figure 2.

Thicknesses and water contact angles of test samples have been measured for studying the homogeneity of material obtained on the large area and reported in

Table 1.

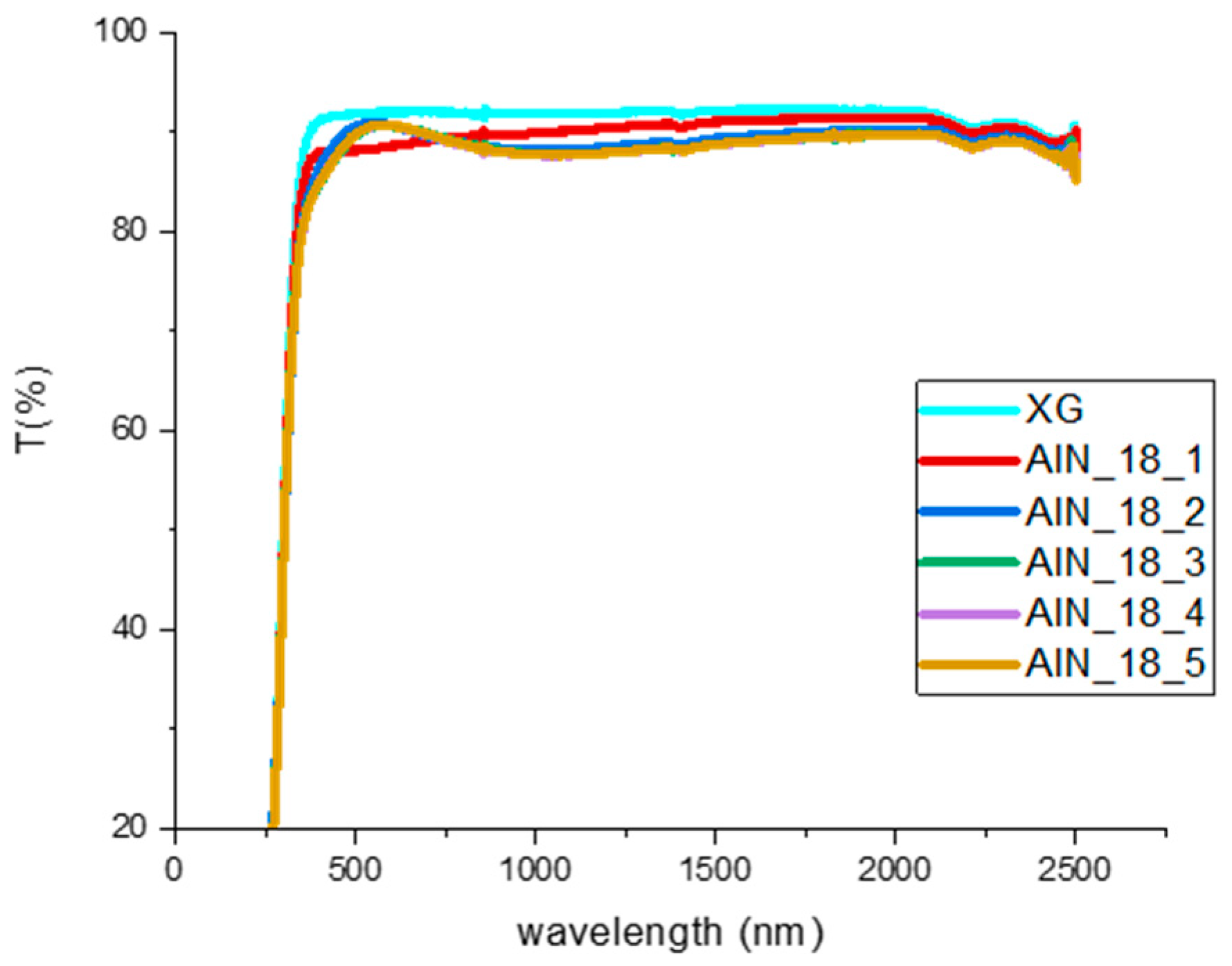

Transmittance of test samples deposited on glass substrates has been reported in

Figure 3.

3.2. Field Positioning and Testing

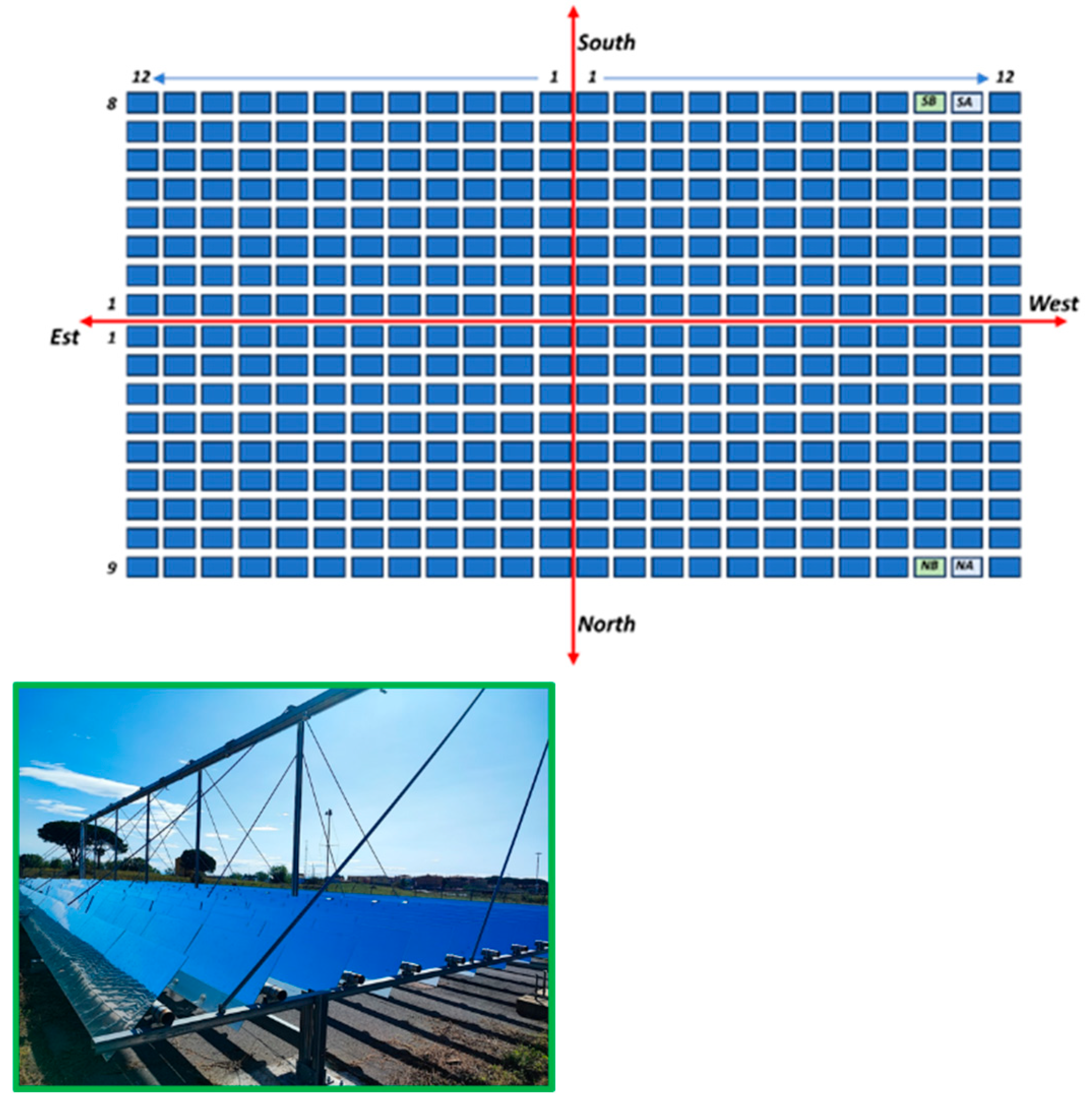

The ENEA FLAGSHIP demonstrative CSP plant (see

Figure 4) utilizes commercial BSM of 1250x 625x 4cm. For testing self-cleaning mirrors prototypes of such work some of commercial mirrors have to be removed, placing in their positions samples to be studied.

Bearing in mind that the pre-industrial ENEA 2 sputtering equipment in dotation of the applied research laboratory allows the processing of a maximum of 50x40 cm substrate; in order to obtain a larger mirror, it is necessary to manufacture several identical sheets (and therefore through the robust and repeatable process described in previous paragraph) and properly joining them. An integration scheme useful for field tests has been proposed, consisting in gluing the mirror panels 50x40 cm obtained by sputtering on BSM solar mirrors substrates previously removed, according to the diagram shown in

Figure 5, where the entire surface of a BSM mirror can be covered with three panel of 50x 40 cm.

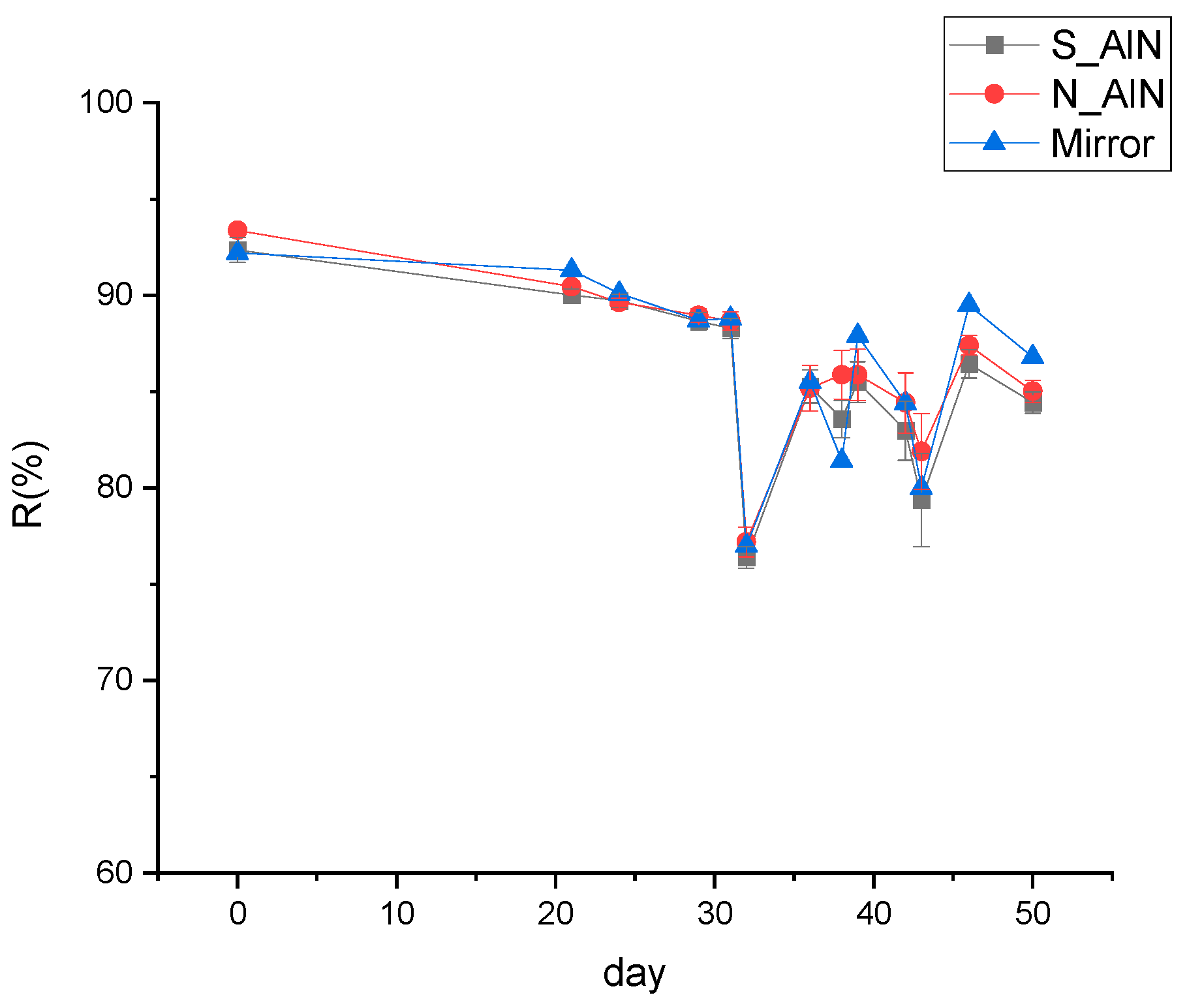

Two mirror prototypes fabricated as described have been placed in the solar Fresnel field positions indicated in

Figure 4 and labeled as S_AlN and N_AlN. By means of a portable reflectometer their reflectance has been measured and compared with the value of adjacent uncovered mirrors labeled SB and NB. Initial reflectance averaged values have been reported in

Table 2.

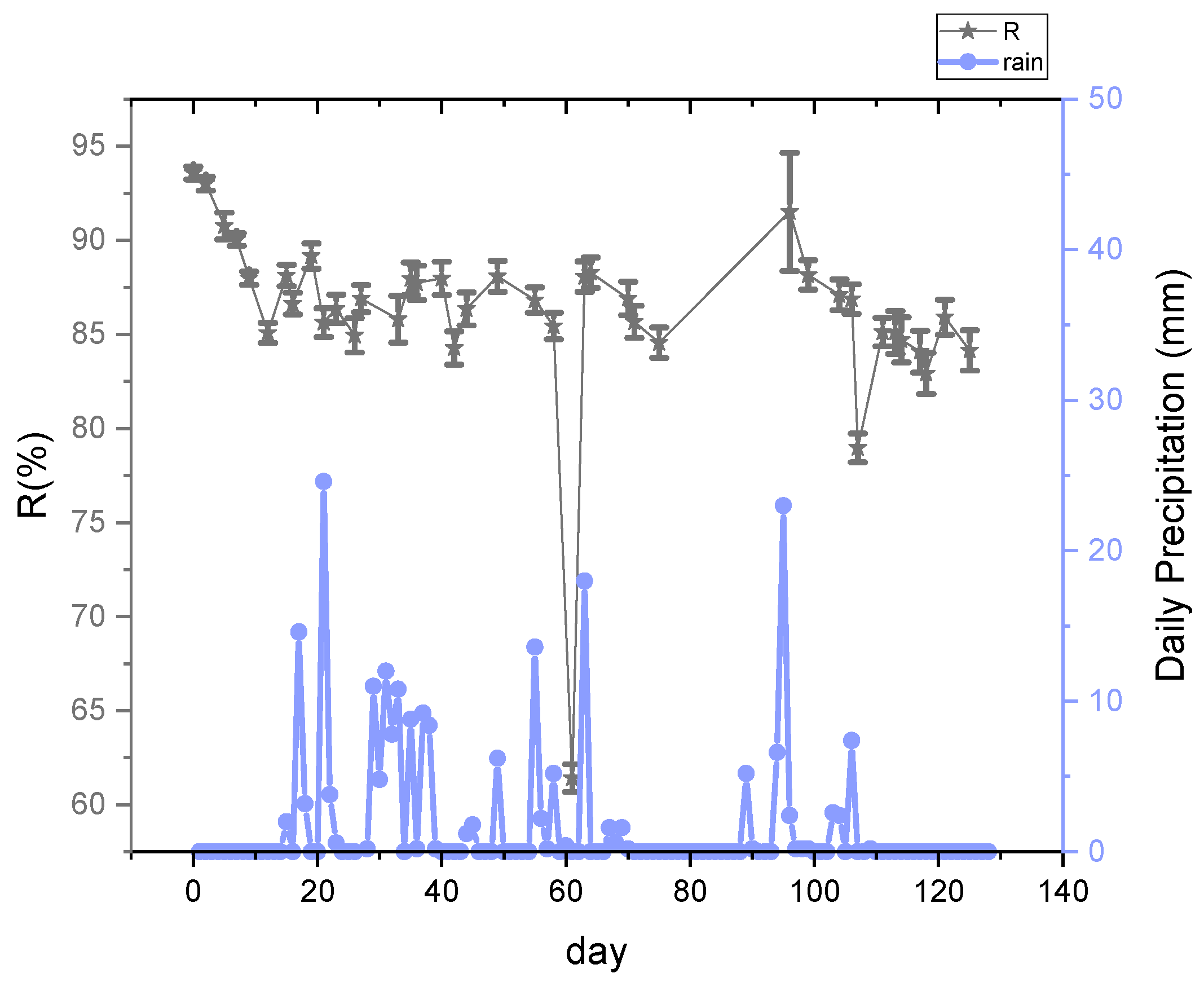

Prototypes have been exposed for three months to the external conditions of the plant site and the results of external measurements campaign are reported in

Figure 6.

In

Figure 7 two prototypes have been compared to their uncovered substrate.

In

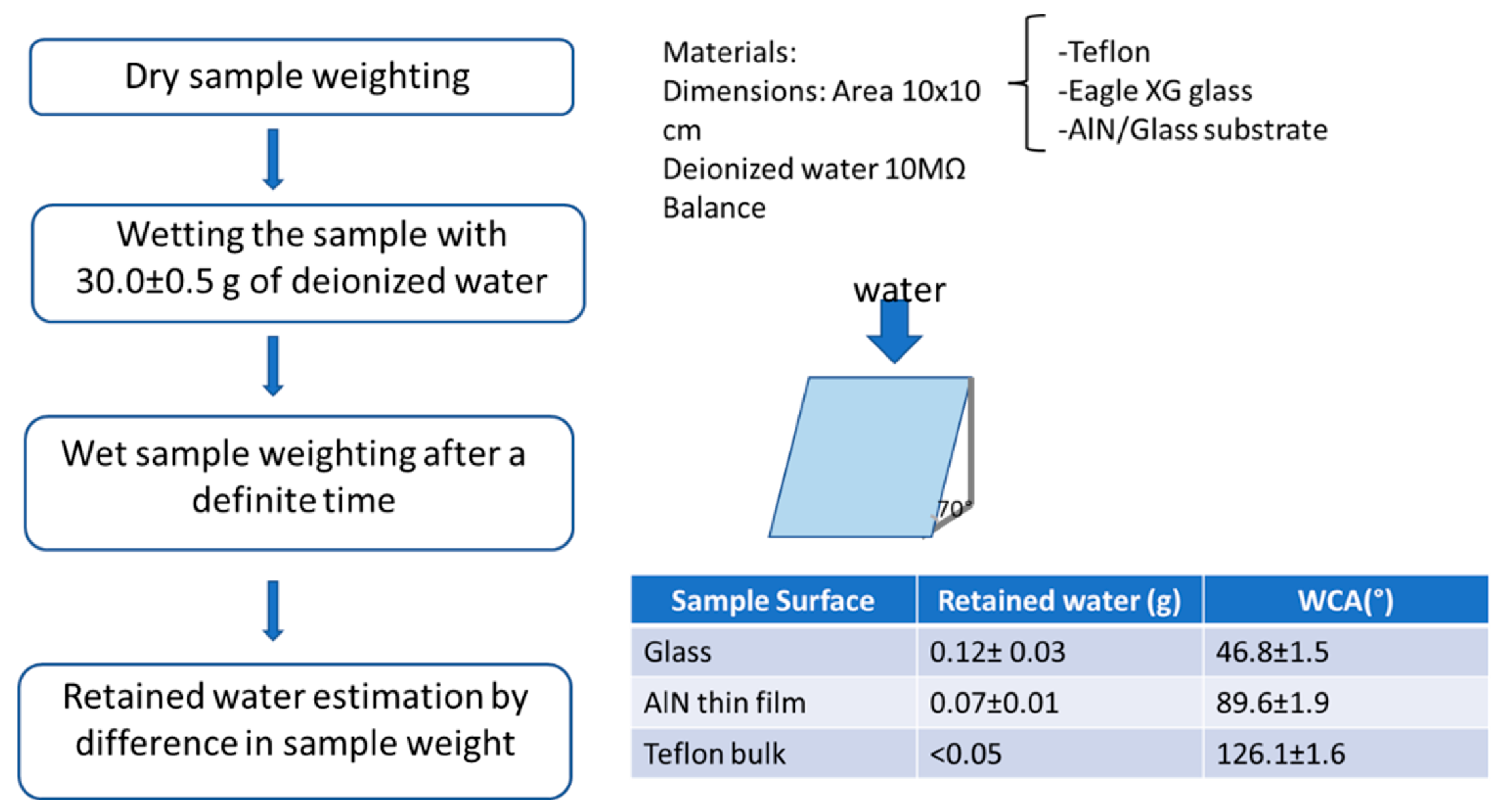

Figure 8 it has been reported the flow-chart of a procedure for estimating the relationship between WCA and water consumption in cleaning operation of coated samples.

A retention of 42% of used water on the washed surface when WCA passes from 46.8° to 89.6° and of 58% when WCA passes from 46.8° to 126.1° can be observed.

4. Discussion

Fabricating new materials on the laboratory scale requires the synthesis and characterization of various samples to obtain the desired physico-chemical properties. As already explained, in the case of auxetic AlN, this has led to a careful definition of different experimental conditions in a previous work. To move toward large-area fabrication of the material, it is necessary to select among these conditions the most profitably scalable. The scaling-up of the sputtering process of auxetic AlN deposition from a laboratory scale to a pre-industrial scale with the proprietary ENEA2 multi-cathode sputtering apparatus has been possible changing the tubular sample holder (utilized for obtaining materials on the lab scale) with a planar holder, as shown in

Figure 1. With this arrangement the rotation is not possible, so the goal has been changing process parameters for obtaining in a frontal geometry the desired film property (in terms of trade-off between optical clarity and WCA). Clearly, on substrates of large dimensions it is important to verify the homogeneity of coating properties. For this reason, a series of testing substrates have been positioned at different heights in the frame of the 50x 40 cm holder, that is the maximum area obtainable with such apparatus, as shown in

Figure 2. It is possible to observe that only the sample 1 has a littlest thickness for borders effects influence, while the other samples are comparable in terms of thicknesses and optical transmittance (reported in

Figure 3). The wetting contact angles, WCA, reported in

Table 2 differ from the medium value of 87° for a little amount. So, process conditions can be considered useful to produce prototypes.

Different samples of big dimensions have been fabricated by means of such process, glued on commercial BSM of the demonstrative plant substrates, according to the scheme of Fig.5 and positioned in the solar field of FLAGSHIP ENEA Fresnel plant in two homologue rows at North and South as indicated in

Figure 4, next to reference mirrors obtained gluing the same number of panels not coated. Their reflectance has been measured by means of a portable reflectometer following the measurements protocol described in session 2 for a three-month period. Initial values have been reported in

Table 2 and it can be noticed that there is only a little difference (R%-R

sub% < 5) with respect to uncovered solar mirror substrate, thanks to the research work on maximizing optical transmittance of coatings. The comparison between North and South positioned prototypes reflectance shows a little difference in their soiling outlining that each mirror in a field can be subject in a different extent to this discrete phenomenon. At the same time the external positioning does not deteriorate coatings (in

Figure 6 there is reflectance vs days for the entire exposure time), even in presence of Scirocco rain events. Idem washing procedures consisting in sprayed distilled water do not degrade self-cleaning layers and are able to restore their initial reflectance.

The relationship between WCA of the coatings and water consumption for 10x10 cm samples described in

Figure 7 let us confirm the self-cleaning effect, or in other terms the possibility of water savings during cleaning procedures.

Clearly, the overall washing policy depends on the decision of plant makers. A detailed estimation on how much water can be saved when all mirrors are self-cleaning can be of great interest for plant makers. It is obviously impossible at this stage to have the exact value (because there are not yet commercial self-cleaning solar mirrors nor plants with mirrors entirely coated), but in our opinion a useful approximation comes from this experimental work in the estimation of around 50% less water content when a commercial glass BSM mirror is substituted with a auxetic AlN one.

5. Conclusions

This work proposes a cheap and robust process for depositing by means of magnetron sputtering an auxetic transparent aluminum nitride based self-cleaning coating on solar mirrors of 50x40cm dimensions, facing the problem of scaling from lab to pre-industrial scale the promising self-cleaning performance of auxetic materials previously studied. Prototypes of produced self-cleaning solar mirrors have been positioned in a demonstrative Fresnel plant located in ENEA, Casaccia (Rome) research center and tested on field to the purpose of studying their performance. They have shown stability in external conditions: no degradation occurs during the test campaign. Moreover, it is possible to wash them, restoring the initial reflectance affected by soiling.

By addressing the issue of washing mirrors with a littlest amount of water with respect to glass utilized for back surface mirrors these coatings contribute to the overall efficiency and viability of solar mirror applications, making them a key component in the pursuit of sustainable and clean energy solutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.; methodology, A.C. and E.G.; software, E.G.; validation, A.C., E.G. and G.C.; formal analysis, E.G.; investigation, G.V. and G.C.; resources, A.C.; data curation, E.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.; writing—review and editing, A.C.; visualization, G.V.; supervision, A.C.; project administration, A.C.; funding acquisition, A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This work was funded by the Italian Ministry of Environment and Energy Security through the “National Electric System Research” Programme – Project 1.9 “CSP/CST technology”, 2022-2024 implementation plan.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Further data about measurement campaign will be published on the ENEA site.

Acknowledgments

In this section, we acknowledge Michela Lanchi, Valeria Russo and Walter Gaggioli for the possibility of installing self-clening solar mirrors in the demonstrative ENEASHIP plant.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Malwad D., Tungikar V. Development and performance testing of reflector materials for concentrated solar power: A review, Materials Today: Proceedings, 2021, Volume 46, Part 1, 539-544, ISSN 2214-7853. [CrossRef]

- Ilse K., Micheli L., Figgis B.W. et al Techno-Economic Assessment of Soiling Losses and Mitigation Strategies for Solar Power Generation, Joule, 2019 Volume 3, Issue 10, 2303-2321, ISSN 2542-4351. [CrossRef]

- Travis Sarver, Ali Al-Qaraghuli, Lawrence L. Kazmerski, A comprehensive review of the impact of dust on the use of solar energy: History, investigations, results, literature, and mitigation approaches, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Volume 22, 2013, 698-733, ISSN 1364-0321. [CrossRef]

- Adak D., Bhattacharyya R., Barshilia H.C. A state-of-the-art review on the multifunctional self-cleaning nanostructured coatings for PV panels, CSP mirrors and related solar devices, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2022 Volume 159, 112145, ISSN 1364-0321. [CrossRef]

- Maharjan S., Liao K-S, Wang A.J, et al Self-cleaning hydrophobic nanocoating on glass: A scalable manufacturing process, Materials Chemistry and Physics, 2020 Volume 239, 122000, ISSN 0254-0584. [CrossRef]

- Bergeron K.D, Freese J.M. Cleaning Strategies for Parabolic-Trough Solar Collector Fields: guidelines for decisions, Sandia National laboratories Technical report SAND81-0385 United States: N. p., 1981. Web. [CrossRef]

- Castaldo A., Gambale E., Vitiello G. Aluminum nitride doping for solar mirrors self-cleaning coatings, Energies 2021, 14, 6668. [CrossRef]

- Kilic, M.E.; Lee, K.-R. Auxetic, flexible, and strain-tunable two-dimensional th-AlN for photocatalytic visible light water splitting with anisotropic high carrier mobility. J. Mater. Chem. C 2021, 9, 4971–4977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonaia A., Addonizio M.L., Esposito S. et al Adhesion and structural stability enhancement for Ag layers deposited on steel in selective solar coatings technology, Surface and Coatings Technology, 2014 Volume 255, 96-101,ISSN 0257-8972. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).