Submitted:

28 June 2024

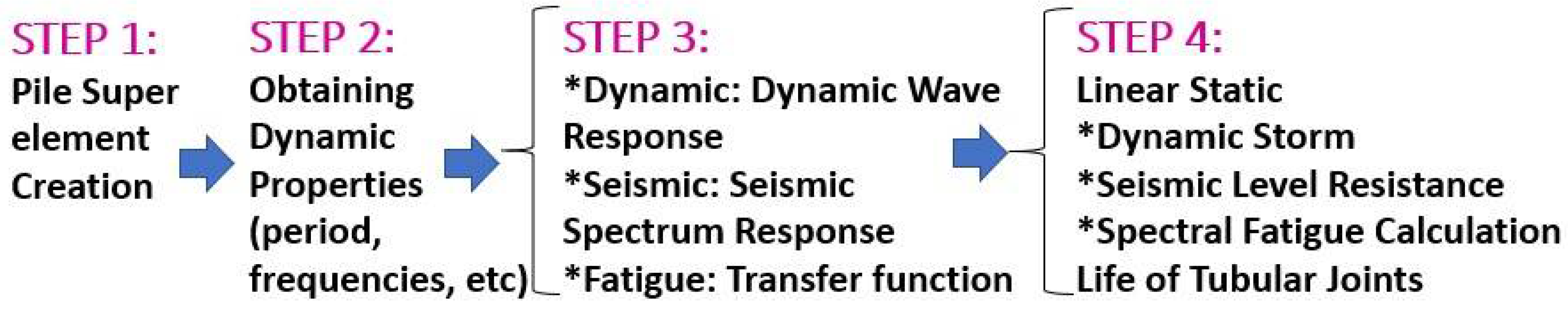

Posted:

01 July 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1. Related Works

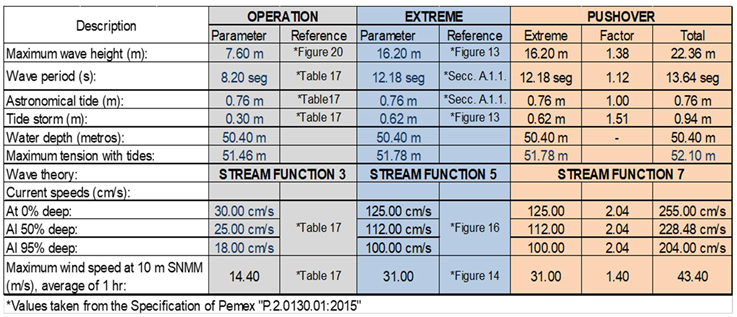

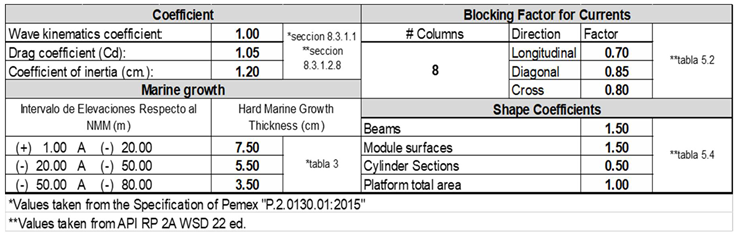

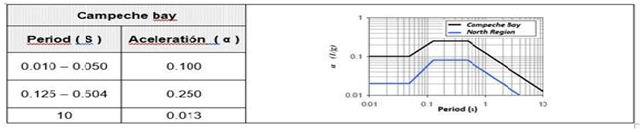

2. Material and Methods

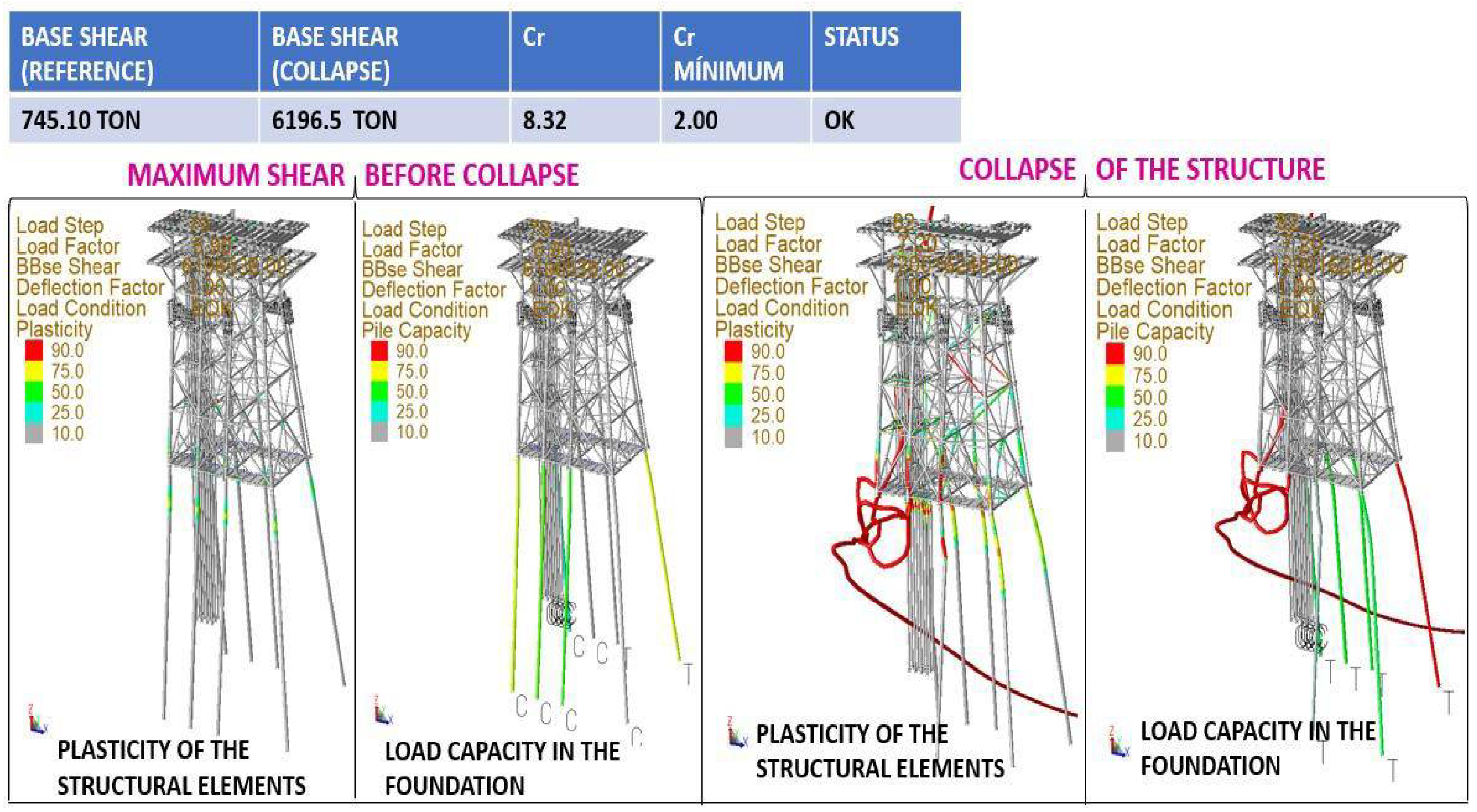

4. The Ultimate Strength Analysis

- The Reference Basal Shear is got from the analysis in Operation and Static Storm site, for the eight directions of incidence in Storm conditions considered in the analysis.

- Gradual application of Gravity Loads (Self Weight, Dead Loads and Live Loads) on the platform. It is applied, for example, in 10 steps with a 10% increment.

- Gradual application of the meteorological loads for the Ultimate Strength Analysis.

- Increments of 2% in the magnitude of such loads have been defined; so that to reach 140%, 70 steps are needed. The percentage of 100% corresponds to the magnitude of the loads defined in table A.1.1 of the Pemex standards for Ultimate Strength.

- Identification of the platform collapse mechanism in each direction.

- Getting the basal shear and RSR for the meteorological conditions that generate platform collapse.

- The ductility analysis should be performed by an ultimate strength analysis using an incremental load (pushover) method. Cr is defined as the ratio between the ultimate lateral load resisting the platform before collapse (obtained in this analysis) and the reference lateral load (calculated in the seismic analysis by resistance), it has been performed for each of the 20 directions of occurrence, the analysis has been executed as follows.

- The gravity load is applied in 10% increments until 100% of the gravity load is reached.

- The seismic load is applied in 5% increments until 100% of the seismic load is reached.

- Seismic loading continues to be applied in 5% increments until the collapse mechanism of the structure is reached.

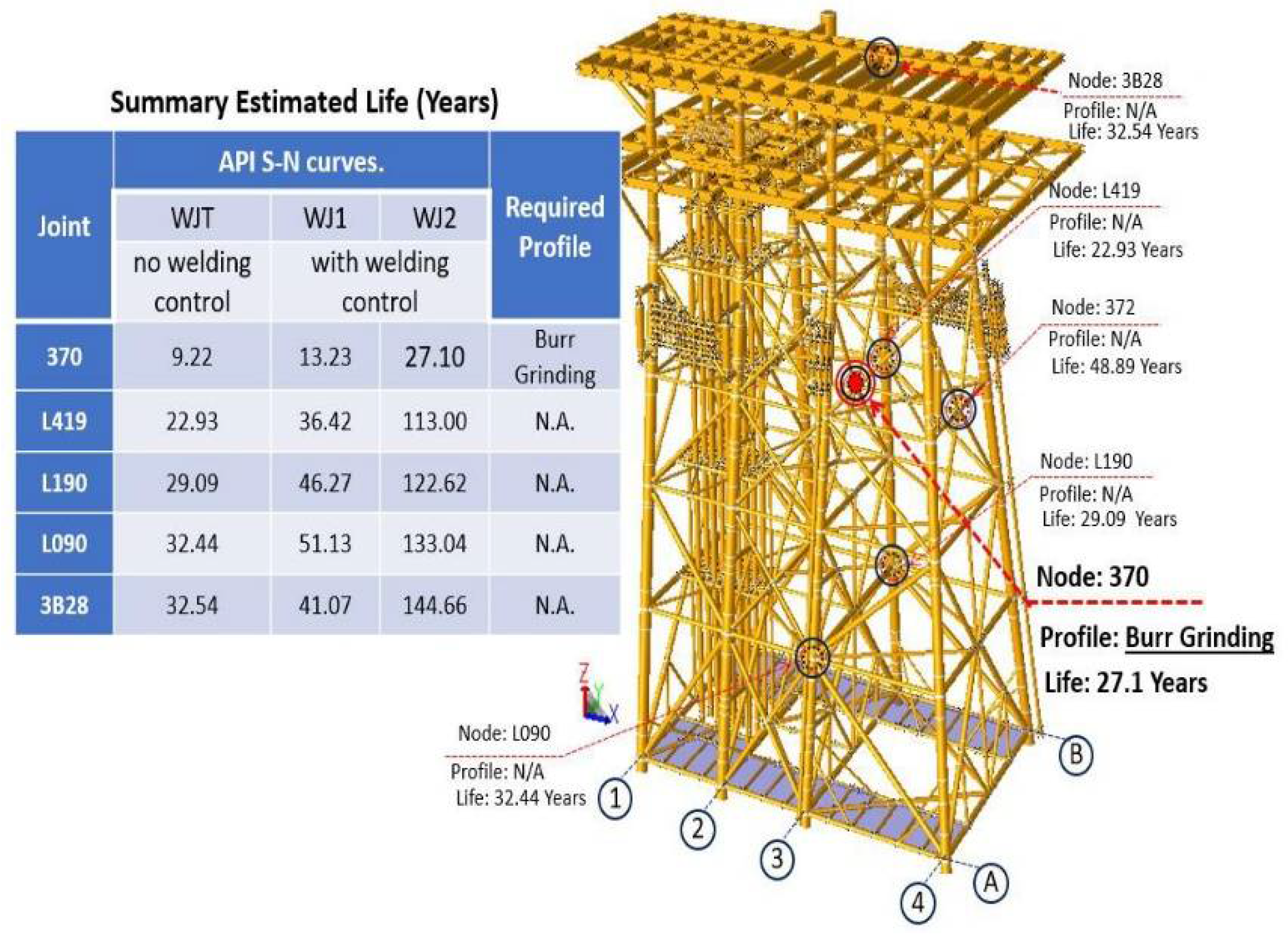

5. Results and Discussion

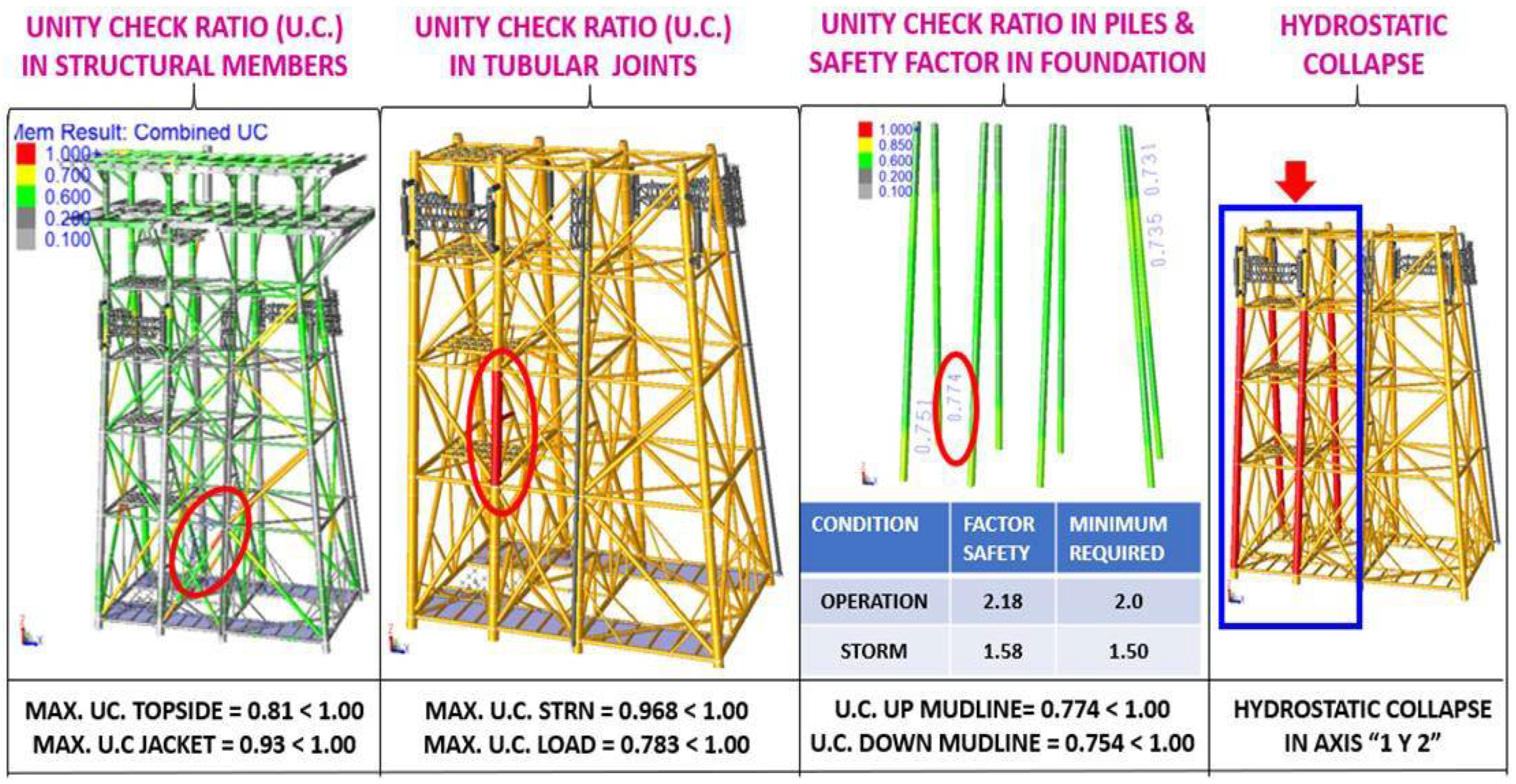

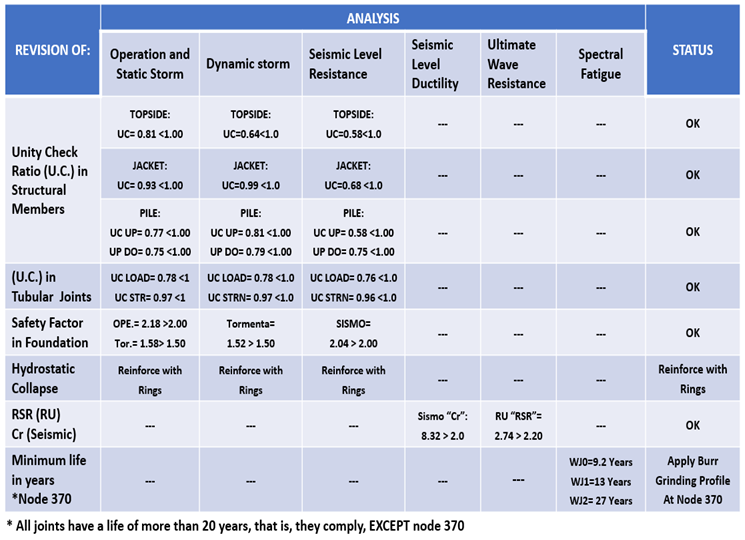

5.1. Operational and Static Storm Analysis

- UC stress interaction relationships: The maximum UC was presented in the substructure (jacket) with a value of 0.93, and in the superstructure (topside) with a value of 0.81, both cases less than 1.0, the UC are less than unity, thus complying with current regulations.

- Tubular Joint Penetration: Tubular joints were checked for penetration (Load) and resistance (STRN), getting values of 0.968 and 0.783 respectively, in both cases, the UC. In both cases, the UC are less than the unit, so they comply with current standards.

- Stress Interaction Relationships U.C. in Piles and Load Safety Factors in the foundation: The piles were reviewed, for the piles above the seabed (mudline) the U.C. max was 0.774 and for the piles below the seabed the U.C. max was 0.754, both cases less than unity. 754, both cases less than unity, as regards the safety factors for axial load on the piles the values are higher than the minimum required by the standard had factors for operation of 2.18 >

- 2.00 (min required) and for storm of 1.58 > 1.50 (min required), which shows that the foundation complies with the parameters established in the standards in force.

- Hydrostatic collapse: there are over stresses in the columns of axis 1 and 2, for which the following solutions can be recommended:

- ➢

- Rings of 1.00" (25.4 mm) thick by 12" (305 mm), for the separation of the rings you

- ➢

- can use as a guide the separation proposed by the program in the redesign that the Sac's program performs, the above for the cases of structures already built but not installed, i.e.: Relocations and service changes, this type of solution is complicated in structures already installed because of the cost of underwater welding.

- ➢

- With offshore platforms that are in the design phase, the proposed solution is to

- ➢

- redesign the elements, i.e. to increase the thickness of the pipe or to install anchor bolts.

- ➢

- For structures already installed on site, the solution may be to cement the elements, as this solution increases the properties of the element.

- ➢

- It is worth mentioning that this document shows the results of a structural proposal and intends to show the solutions, the structural civil engineer together with his working group will determine which is the best technical and economical solution for the

- ➢

- project, in this case study hydrostatic collapse rings will be used as a solution.

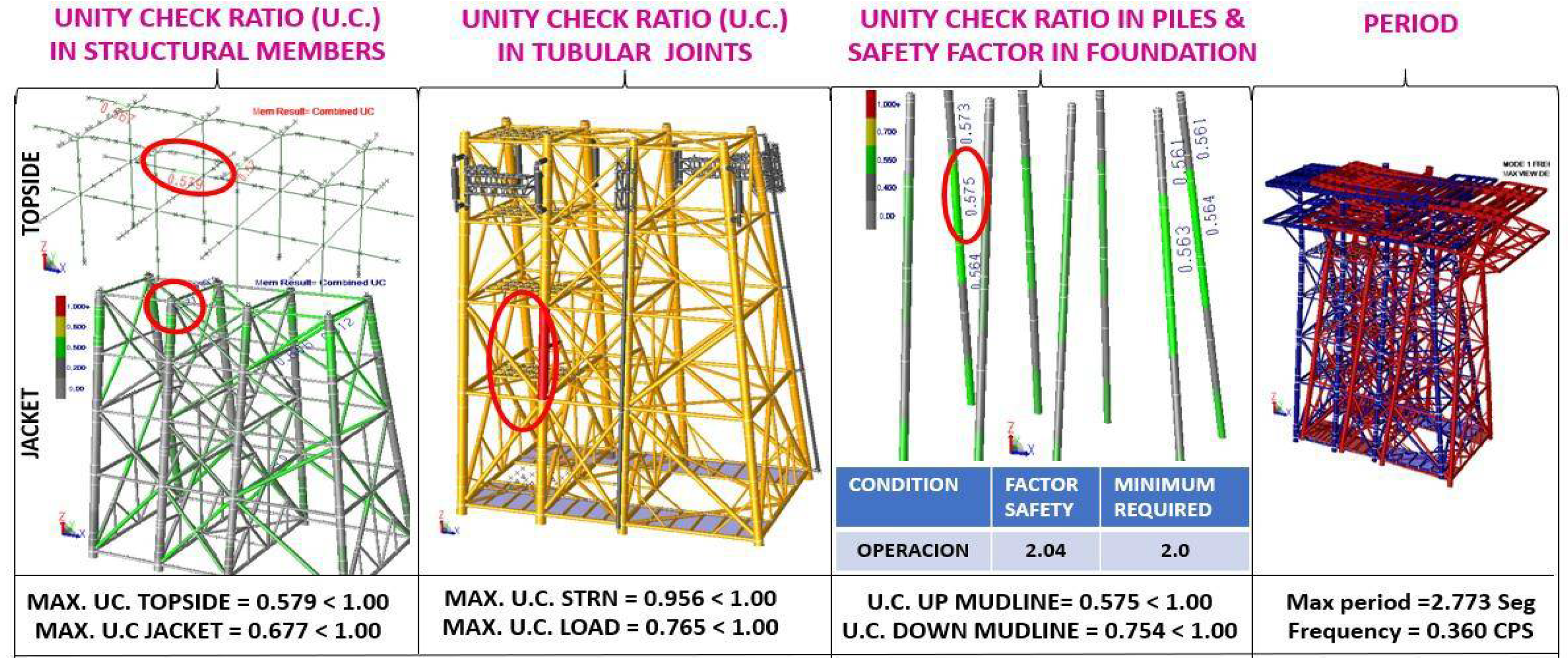

5.2. Dynamic Storm Analysis

- U.C. stress interaction ratios: The maximum U.C. occurred in the substructure (jacket) with a value of 0.987, and in the superstructure with a value of 0.638, both cases less than 1.0, the U.C. are less than unity, thus complying with current regulations.

- Tubular Joint Penetration: Tubular joints were checked for penetration (Load) and resistance (STRN), getting values of 0.777 and 0.969 respectively, in both cases, the UC. They are less than the unit, so they comply with the current standards.

- Stress Interaction Relationships U.C. in Piles and Load Safety Factors in the foundation: The piles were reviewed, for the piles above the seabed (mudline) the U.C. max was 0.81 and for the piles below the seabed a U.C. max of 0.79, both cases less than unity. 79, both cases less than the unit, regarding the safety factors for axial load on the piles, a value for storm of 1.52 > 1.50 (min required) was obtained, which shows that the foundation complies with the parameters established in the current standards, described in Figure 6.

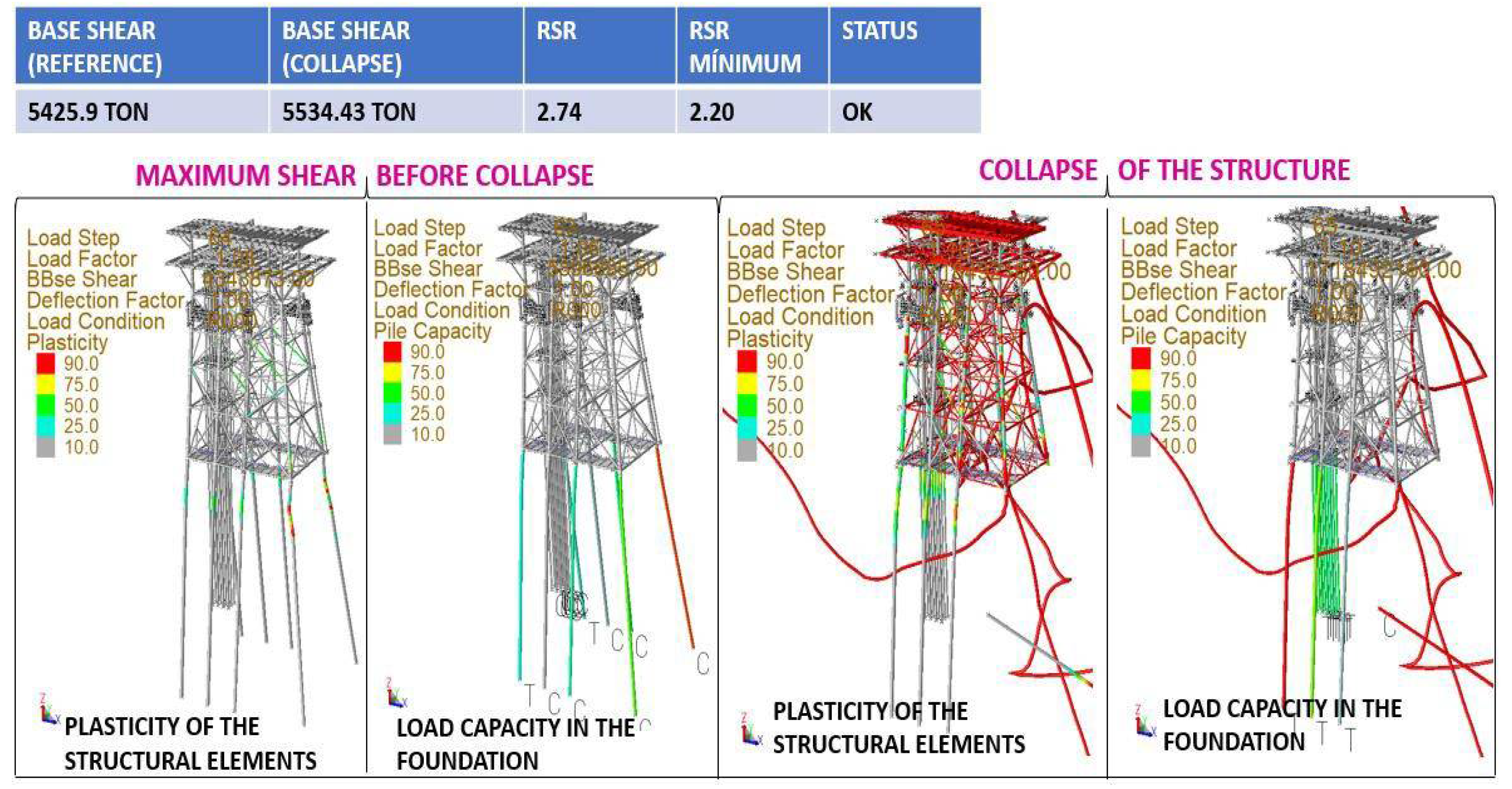

5.2. Ultimate Wave Resistance Analysis

6. Conclusions

References

- Kaiser, M.J.; Liu, M. Decommissioning cost estimation in the deepwater U.S. Gulf of Mexico Fixed platforms and compliant towers. Marine Structures 2014, 37, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.; Shafiee, M. An overview of maintenance management strategies for corroded steel structures in extreme marine environments. Marine Structures 2020, 71, 102718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassino, N.; Zordan, M.; Zandonini, R. Experimental study of the shear behavior of floor diaphragms in light steel residential buildings. Thin-Walled Structures 2021, 167, 108099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhaniaragh, B.; Afzalimir, S.H.; Ruggieri, C. Towards the prediction of hydrogen–induced crack growth in high–graded strength steels. Thin-Walled Structures 2021, 159, 107245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Pang, S.D.; Liew, J.Y. Axial load resistance of grouted sleeve connection for modular construction. Thin-Walled Structures 2020, 154, 106883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viero, P.F.; Roitman, N. Application of some damage identification methods in offshore platforms. Marine Structures 1999, 12, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onoufriou, T. Reliability based inspection planning of offshore structures. Marine Structures 1999, 12, 521–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotsberg, I.; Sigurdsson, G.; Fjeldstad, A.; et al. Probabilistic methods for planning of inspection for fatigue cracks in offshore structures. Marine Structures 2016, 46, 167–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojtahedi, A.; Yaghin, M.A.L.; Ettefagh, M.M.; et al. Detection of nonlinearity effects in structural integrity monitoring methods for offshore jacket-type structures based on principal component analysis. Marine Structures 2013, 33, 100–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, M.; Gardoni, P. A simplified method for reliability- and integrity-based design of engineering systems and its application to offshore mooring systems. Marine Structures 2014, 36, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotsberg, I.; Olufsen, O.; Solland, G.; et al. Risk assessment of loss of structural integrity of a floating production platform due to gross errors. Marine Structures 2004, 17, 551–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeran, A.; Siriwardane, S.C.; Mikkelsen, O.; et al. A framework to assess structural integrity of ageing offshore jacket structures for life extension. Marine Structures 2017, 56, 37–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, R.; Ibrahim, Z.; Chai, H.K. Screening method for platform conductor integrity assessment for life extension prioritisation. Marine Structures 2018, 58, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, M.A.; Cyrino, C.R.; Hernández, I.D.; et al. Experimental and numerical analyses of the ultimate compressive strength of perforated offshore tubular members. Marine Structures 2018, 58, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeinoddini, M.; Namin, Y.Y.; Nikoo, H.M.; et al. An EWA framework for the probabilistic-based structural integrity assessment of offshore platforms. Marine Structures 2018, 59, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guédé, F. Risk-based structural integrity management for offshore jacket platforms. Marine Structures 2019, 444–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabeshpour, R.; Fatemi, M. Optimum arrangement of braces in jacket platform based on strength and ductility. Marine Structures 2020, 71, 102734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamkowski, A.; Lewandowski, M. Stanisław Lewandowski, Fatigue life analysis of hydropower pipelines using the analytical model of stress concentration in welded joints with angular distortions and considering the influence of water hammer damping. Thin-Walled Structures 2021, 159, 107350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Guo, L.; Zhang, S.; et al. Performance degradation of circular thin-walled CFST stub columns in high-latitude offshore region. Thin-Walled Structures 2020, 154, 106906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yang, D.Y.; Frangopol, D.M. Ship service life extension considering ship condition and remaining design life. Marine Structures 2021, 78, 102940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabeshpour, M.R.; Fatemi, M. Optimum arrangement of braces in jacket platform based on strength and ductility. Marine Structures 2020, 71, 102734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojtahedi, A.; Yaghin, M.A.L.; Ettefagh, M.M.; et al. Detection of nonlinearity effects in structural integrity monitoring methods for offshore jacket-type structures based on principal component analysis. Marine Structures 2013, 33, 100–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, H.; Zavvar, E. Stress concentration factors induced by out-of-plane bending loads in ring-stiffened tubular KT-joints of jacket structures. Thin-Walled Structures 2015, 91, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, H.; Mohammadi, A.H.; Yeganeh, A. Probability density functions of SCFs in internally ring-stiffened tubular KT-joints of offshore structures subjected to axial loading. Thin- Walled Structures 2015, 94, 485–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leheta, H.W.; Badran, S.F.; Elhanafi, A.S. Ship structural integrity using new stiffened plates. Thin-Walled Structures 2015, 94, 545–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgarian, B.; Aghaeidoost, V.; Shokrgozar, H.R. Damage detection of jacket type offshore platforms using rate of signal energy using wavelet packet transform. Marine Structures 2016, 45, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S.F.; Galgoul, N.S.; Starossek, U.; et al. An efficient time domain fatigue analysis and its comparison to spectral fatigue assessment for an offshore jacket structure. Marine Structures 2016, 49, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, R.; Rodríguez, R.; Vázquez-Hernández, A.O. Damage detection in offshore jacket platforms with limited modal information using the Damage Submatrices Method. Marine Structures 2017, 55, 78–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeran, A.; Siriwardanea, S.C.; Mikkelsen, O.; et al. A framework to assess structural integrity of ageing offshore jacket structures for life extension. Marine Structures 2017, 56, 237–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodaran, N.A.; Ahmadi, H.; Lotfollahi-Yaghin, M. Parametric study on structural behavior of tubular K-joints under axial loading at fire-induced elevated temperatures. Thin- Walled Structures 2018, 130, 467–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeinoddini, M.; Namin, Y.Y.; Nikoo, H.M.; et al. An EWA framework for the probabilistic-based structural integrity assessment of offshore platforms. Marine Structures 2018, 59, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Muskulus, M. A global slamming force model for offshore wind jacket structures, Marine Structures 2018, 60, 201–217.

- Guéde, F. Risk-based structural integrity management for offshore jacket platforms. Marine Structures 2019, 63, 444–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabeshpour, M.; Fatemi, M. Optimum arrangement of braces in jacket platform based on strength and ductility. Marine Structures 2020, 71, 102734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüsken, G.; Shamsuddoha, M.; Pirskawetz, S.; et al. Potential of a repair system for grouted connections in offshore structures: Development and experimental verification. Marine Structures 2021, 77, 102934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Fernandes, L.; Silvestre, N.; Correia, R.; et al. Fracture toughness-based models for damage simulation of pultruded GFRP materials. Composites Part B: Engineering 2020, 186, 107818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, D.; Gonilha, J.; Correia, J.R.; et al. Exterior beam-to-column bolted connections between GFRP I-shaped pultruded profiles using stainless steel cleats, Part 2: Prediction of initial stiffness and strength. Thin-Walled Structures 2021, 164, 107762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmanli, U.; Becque, J. . Stress concentration factors for multi-planar DKT tubular truss joints under axially balanced loads. Journal of Constructional Steel Research 2021, 184, 106781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; et al. Experimental and Numerical Investigations of Octagonal High- Strength Steel Tubular Stub Columns under Combined Compression and Bending. Journal of Structural Engineering American Society of Civil Engineers 2021, 147, 04020282. [Google Scholar]

- Pemex. Petróleos Mexicanos. Estadísticas petroleras [in Spanish]. 2021.

- Pemex. Informe mensual sobre producción y comercio de hidrocarburos [in Spanish]. 2021.

- Atkins Engineering Services (1990). Fluid Loading on Fixed Offshore Structures, OTH 90 322. URL: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/237397122.pdf.1990.

- API (2014). American Petroleum Institute, Recommended Practice for Planning, Designing and Constructing Fixed Offshore Platforms –Working Stress Design, API RP 2A-WSD, Twenty-second edition, November 2014. Recuperado 23 de julio del 2024, URL: https://store.accuristech.com/api/standards/api-rp-2a-wsd-r2020?product_id=1886617.

- Chakrabarti, S.K. (2005). Handbook of offshore engineering. Vol. 1. ELSEVIER.

- Fenton, J.D. A high-order cnoidal wave theory. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 1979, 94, 129–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaechi, C.V.; Reda, A.; Butler, H.O.; Ja’e, I.A.; An, C. Review on Fixed and Floating Offshore Structures. Part I: Types of Platforms with Some Applications. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidiq, R.B.; Utomo, C.; Silvianita. Determining Factors of Fixed Offshore Platform Inspections in Indonesia. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).