1. Introduction

Grain

Amaranthus (

Amaranthus hypochondriacus) is a future crop in African agricultural systems due to its nutritional supremacy and drought tolerance [

3,

23]. Considerable interest warranting cultivation of genetic pure grain

Amaranthus (grain Amaranth) has increased due to the crop’s gluten-free, anti-cancer, somewhat higher in nutrients than typical cereals and its hardy, low-input nature including ability to withstand salt, stress, and drought [

21]. Although significant yields are being attained in many countries, the grain Amaranth seed system is still informal in the Zimbabwean agricultural landscape a scenario that will affect the genetic purity of Amaranth seeds in the long run [

12,

14]. Increased production of this pseudo-cereal crop must begin with the availability of quality seeds that are free from contamination. However, conspecificity between cultivated and weedy species widens the risk of seed contamination leading to loss of genetic purity in seeds [

9,

19]. There are both monoecious and dioecious species within the Amaranthaceae family with species like pigweed being obligate outcrossers [

8].

Genetic contamination remains a huge problem in most cross-pollinated seed crops and concerning grain Amaranth, varying degrees of contamination have been recorded in several studies [

13,

15,

22]. According to [

15]

A. hybridus,

A. palmeri,

A. powell,

A. retroflexus, and

A. quitensis constitute the wild relatives that represent the secondary gene pool of grain Amaranth that can cause seed contamination of the pseudo-cereal crop through cross-pollination. Although grain Amaranth has perfect flowers, varying degrees of contamination of the crop from weedy species have also been reported in Mexico [

6,

19]. The cultivated white-seeded grain is less valuable if contaminated by the wild relatives' off-type seeds through cross-pollination [

18]. Crop weedy hybrids remain a seed purity problem for the cultivated grain Amaranth and they produce off-type seeds that reduce the marketability of the grains [

16]. It is therefore important to prevent weedy Amaranth and any other wild relatives from cross-pollinating the cultivated grain varieties.

An investigation carried out by [

7] indicated that grain Amaranth seeds harvested from crops contaminated by weedy Amaranth species can produce crop-weedy hybrids that reduce both the quality and yield of grain types. However, in trying to minimise outcrossing and maintaining genetic purity among varieties of different seed crops including grain Amaranth, several strategies ranging from physical, temporal, and spatial isolation have been put in place [

20]. Isolation distance is a minimum separation required between two varieties of the same species to prevent seed contamination [

2]. Several studies have shown that isolation by distance is the most reliable method whereby enough distance is provided between a variety and any possible source of contamination [

13,

15].

The major problem associated with isolation by distance is that a lot of space is needed especially when the species are predominantly cross-pollinated of which land scarcity is naturally common. In a field trial done at Rodale Research Center in America, strips of maize were planted between Amaranth lines to reduce pollen movement between the lines [

11]). This technique is known as physical isolation through the use of barriers. The technique has proven to lack depth in fighting seed contamination as significant pollen intrusion has been noted in several studies [

4].

Literature for recommended separation distances is scarce and controversial as shown by many debates among researchers [

1,

10]. It is therefore important to treat these recommended isolation distances as general guidelines and seed savers in their respective areas of operation have to research through field trials in a bid to establish separation distances that best suit their unique geographic areas [

7]. This is very important because pollinating agents, environmental conditions as well as landscape features differ from place to place. This research, therefore, seeks to investigate a minimum isolation distance sufficient enough to prevent contamination of grain Amaranth from both weedy and vegetable species, smooth pigweed

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

Field experiments were carried out at two sites during the 2020/21 rainy season. The first site was at the Zimbabwe Republic Police’s (ZRP) Worcestershire Farm in Gweru which is under Natural Region (NR) III at 1429 m above sea level, latitude 18

o47’ S and 30

o84’ E and has red clay (Montmorillonite) soils [

17]. The site received an average rainfall of 670 mm [

24] and a mean daily temperature of 18

oC. The second experimental site was at Stella Farm, located in Bindura. It is 1,070 m above sea level under NR11b and receives an average annual rainfall of 850 mm [

24]. The latitude of the site is 17

o 20' S and 19

o 13' E and has red clay soils [

17]. The minimum and maximum temperatures of the site are 19

oC and 28

oC respectively.

The third experiment was laid at Save Our Souls (SOS) Farm in Shamva during the 2021/22 rain season. The site falls under Natural Agroecological Region IIa at 1,070 m above sea level. It contains red clay soils [

17], and lies on compass coordinates 16

o47' S and 31

o19' E, receiving an annual rainfall of 850 mm. The minimum and maximum temperatures of this site are 19

oC and 28

oC respectively.

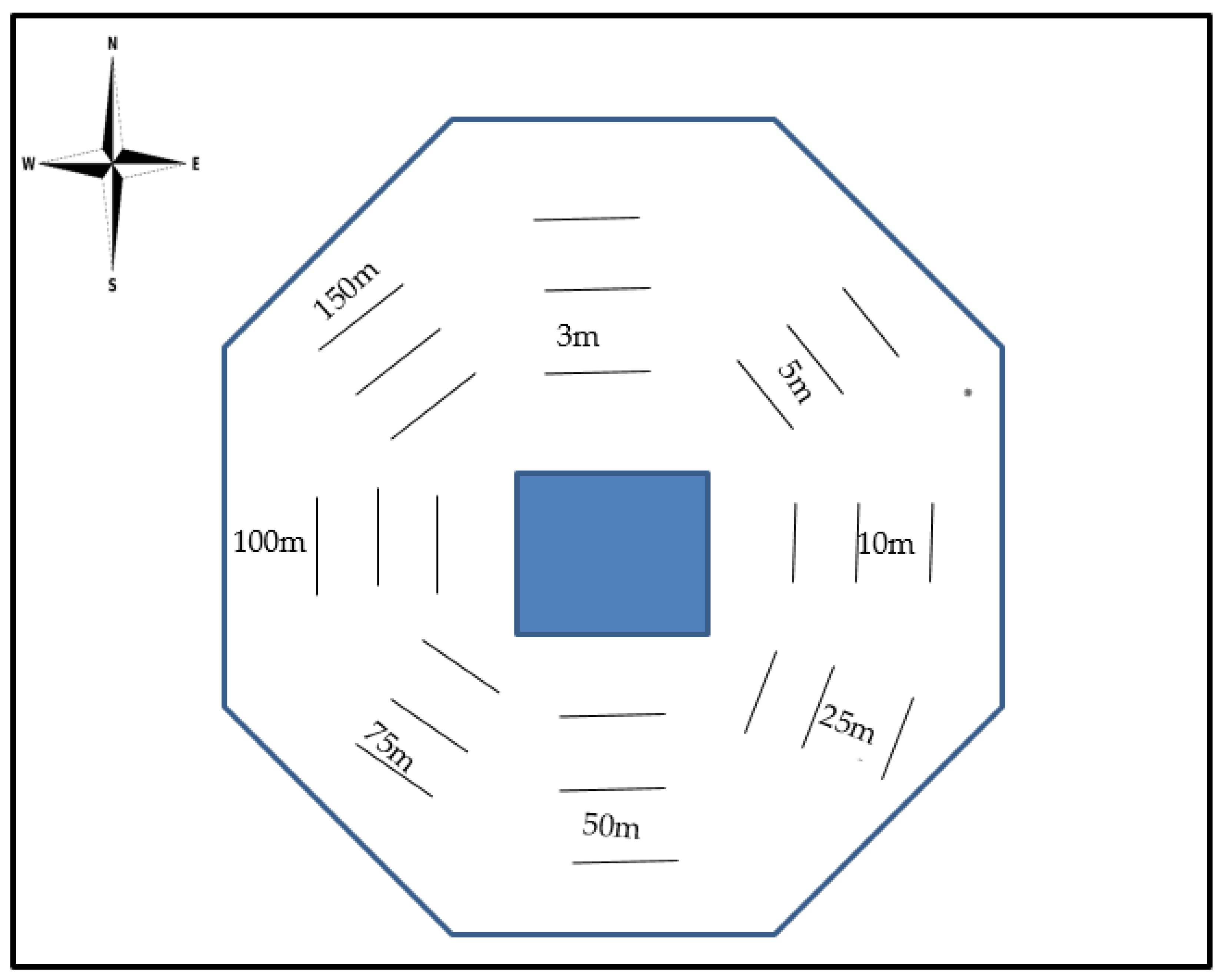

2.2. Pollen Source and Pollen Recipient Materials

At each site, the Smooth pigweed was planted in the centre on a plot measuring 40 m

2 as a pollen donor while

A.hypochondriacus was planted right around the donor plot at several distinct distances. Across the sites, pollen source plots had a density of 177 plants and the recipient plots were 20 m

2 with 88 plants each (

Figure 1).

2.3. Cultivation Procedures and Crop Management

2.3.1. Land Preparation

Both of the Amaranthus species under this study are small-seeded therefore a fine tilth seedbed was a must. Due to the size of the plots, a pick was used to dig the land manually. Soil clods were broken down until a reasonable fine tilth was achieved and the site was then leveled. In preparing land for small-seeded crops like grain Amaranth, a fine tilth is recommended to promote soil seed contact for improving seed germination. A hoe was used to make planting stations and a garden line aided in straightening planting station rows within each plot. Experimental plots measuring 8 x 5 m and 5 x 4 m were constructed for pollen donor crops and recipient plants respectively. An inter-row spacing of 75 cm by 30 cm in-row were used across all the sites.

2.3.2. Planting and Fertiliser Application

Planting across all the sites was staggered with the aim of ensuring synchronicity between the pollen donor and the recipient crop. The Smooth pigweed was planted on the 13th of January while grain Amaranthus on the 27th of January during both seasons. Shallow furrows which are 75 cm apart were made at each of the plots and a seed rate of 2 g per plot was used in all of the contamination plots while 0.5 g for grain Amaranth per plot. The Amaranth seeds were then mixed with dry sand at a ratio of 1: 12 (1 part seed to 12 parts sand) to ensure even seed placement and also avoid unnecessary wastage. The sand-seed mixture was then evenly drilled into the well-prepared furrows.

The depth of the furrows was within the range of 1 cm to 2 cm as seed burial beyond this level will compromise germination. For accurate reasons, a ruler was used to measure this depth across all the sites. The Amaranth seeds possess an aroma that mostly attracts ants therefore, the seeds were covered immediately after sowing so that they were not eaten or carried away by these pests. When soil moisture condition is adequate for a prolonged period, Amaranth seeds tend to germinate within a period of three to four days after sowing and once the plant is fully established, it is relatively tolerant to water shortages. Compound D fertiliser was used as a basal at a rate of 3 kg per donor plot and 2 kg per recipient plot. The fertiliser was drilled into the furrows before seed sowing. Ammonium Nitrate (AN) was used a top dresser at a rate of 3 kg and 2 kg on pollen donor and recipient plots respectively.

2.3.3. Irrigation Water

The amount of rainfall received across all the experimental sites during the 2020/21 rain season was not sufficient to effect an excellent percentage of germination and ensure a good crop stand. A prolonged dry spell also started around mid-January 2022 as a result this triggered the application of supplementary irrigation water across all the seasons. However, each pollen recipient plot received 4 x 10 liters of watering cans and 8 x 10 liters for contamination plots across all the sites after every four days. This was done to make sure that water scarcity did not compromise the general growth of the plants as this had a negative bearing on the efficacy of the research. Since planting furrows were shallow, all the experimental plots were covered with grass during the first four days in a bid to protect the unearthing of Amaranth seeds from heavy downpours.

2.3.4. Weed Control

All the experimental plots on all of the sites remained weed-free throughout the growing periods. Inside the plots, hoe weeding was used while a few meters around each plot a slasher was used to cut the weeds. Removing weeds around the plots aids in effective pests and disease management.

2.3.5. Thinning

Thinning was done as soon as the crops were 10 cm high and this height was reached two weeks after crop emergence. This operation was performed through uprooting weak plants thereby leaving the healthy and strong ones. The exercise which usually provides many advantages was done in compliance with the 30 cm space between individual plants. On the contamination plot which measures 40 m2, a final plant density of 177 plants was maintained and on pollen-receiving plots, a plant population of 88 plants was also achieved.

2.3.6. Pests and Disease Control

Scouting for both pests and diseases was frequently done during the early or late hours after every two days. Although Amaranth species do not suffer much from insect damage, regular scouting of pests like pigweed beetles, leaf miners, and flea beetles was done accordingly. Pigweed beetles were prevalent in all of the experimental plots and an insecticide called Bullock Star 262.5 EC was used as a control measure. An integrated pest and disease management approach was used to ensure that the experimental results were not affected by pest and disease damage. Measures like the use of clean healthy seeds in addition to chemicals were employed in a bid to minimise seed-borne and other diseases. Diseases such as leaf spot, panicle black mold, and dumping off were also closely monitored and none were found across all the experimental sites.

2.3.7. Rouging

Rouging was done throughout the whole growing period by uprooting off-type plants. This operation was done to ensure that the seed lot produced contained the highest genetic, sanitary, and physiological qualities. The exercise was achieved by regular inspection of the experimental plots and removal of any off-types or diseased plants. Characteristics that were used during rouging include general appearance, leaf shape and color, plant height, characteristics of the spike, floral color in the spike, and maturity period. Any member of the Amaranthaceae family found within a 500 m radius of the experimental sites was rouged out.

2.4. Data Collection

2.4.1. Synchronisation of Flowering

To achieve maximum synchronisation of flowering between the two species, the Smooth pigweed was grown fourteen days before grain Amaranth planting. The period of flowering was defined as the time frame between the commencing of the first pollen shedding and the last few remaining pollen grains. The data were recorded for all the grain Amaranth plots while for the Smooth pigweed that only acted as pollen donor, only the period of pollen shedding was recorded. The main flowering period of the grain Amaranth took about ten days on average. However, because of variations in individual plant development, the complete flowering period across all the sites ranges from 12 to 16 days.

Table 1.

Experimental sites showing planting material, plot dimension, anthesis, and sowing dates.

Table 1.

Experimental sites showing planting material, plot dimension, anthesis, and sowing dates.

| Gweru site |

Seed colour |

Plot size (m) |

Planting dates |

Flowering dates |

Pollen shedding (50%) |

| Smooth pigweed |

Black |

40 m2

|

13 January 2021 |

10 March 2021 |

12 March 2021 |

| G. Amaranth |

White |

20 m2

|

27 January 2021 |

12 March 2021 |

15 March 2021 |

Bindura site

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Smooth pigweed |

Black |

40 m2

|

13 January 2021 |

06 March 2021 |

10 March 2021 |

| G. Amaranth |

White |

20 m2

|

27 January 2021 |

09 March 2021 |

13 March 2021 |

| Shamva site |

|

|

|

|

|

| Smooth pigweed |

Black |

40 m2

|

13 January 2022 |

11 March 2022 |

14 March 2022 |

| G. Amaranth |

White |

20 m2

|

27 January 2022 |

12 March 2022 |

15 March 2022 |

2.4.2. Climate Monitoring during the Flowering Period

The meteorological data including wind direction, air temperature, and wind speed that covers the entire flowering period were obtained from the nearest Meteorological Services Departments (

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4). Wind speed and direction were recorded seven days before and after flowering of the recipient crop with “knot cal miles/hour” and “degrees” as the units of record respectively. The hours evaluated were only restricted to the time between 6 a.m. and 4 p.m. a period when nearly all pollen shedding took place [

4]. This time frame was therefore taken as the actual pollination period where possible cross-pollination will occur.

2.5. Data Analysis and Calculation of Cross-Pollination Rates (%)

At maturity, seeds from pollen recipient plots were harvested and threshed plot by plot and then subjected to examination. Seed contamination analysis was done using grain Amaranth seed color as a morphological marker and the cross-pollination rate method was used for statistical calculations. Workable samples of 5 g per plot were randomly selected and the contamination rate was calculated as the ratio of off-white Amaranth grains to all grains of the sample using the formula below:

CPp% = [Sum (off-white grains in the sample)/Sum (total grains in the sample)] x 100

The cross-pollination data with distance to the pollen donor of Smooth pigweed were then fitted to the “Exponential Decline Model”

Y = Y0e – BX

Where Y is cross-pollination (%), Y0 is cross-pollination extrapolated to X = 0. B is the shape coefficient, and X is the distance (m) of the sampled plot from the pollen source.

3. Results

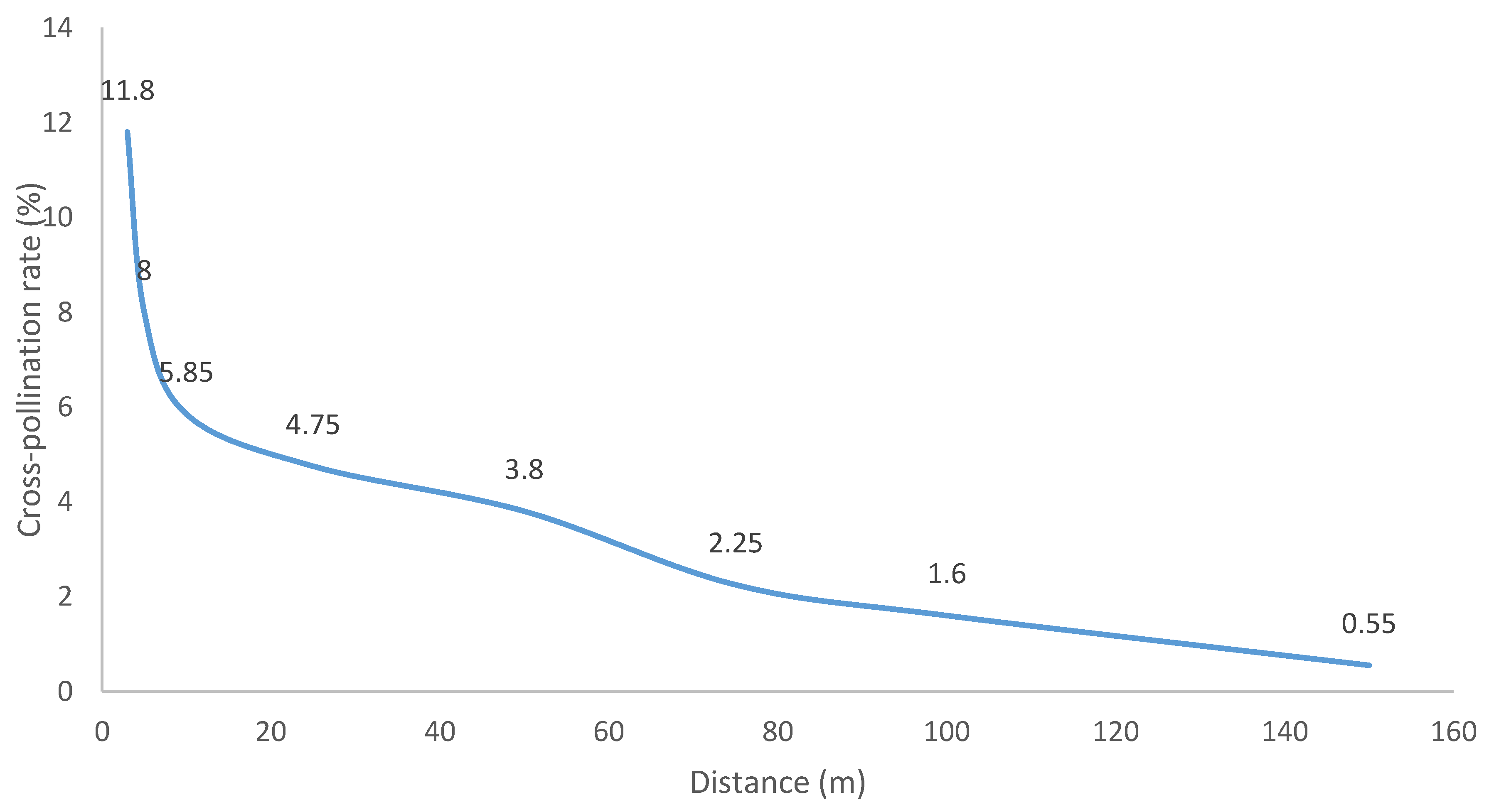

3.1. Effect of Isolation Distance on Genetic Purity of Grain Amaranthus at Gweru Site during 2020/21 Rain Season

Synchronisation during the anthesis period between pollen donor and pollen recipient plants varied at the Gweru site (

Table 1). The pollen recipient plot reached 50 % pollen shedding by March 15 and the pollen donor plot on the 12th of March 2021. Plants on the contaminant plot flowered 2 days earlier than those on the pollen recipient plots (

Table 1). The prevailing wind mostly originated from the south and south-east directions during the flowering period with an average daily wind speed of 8.1 knotcalmiles/hr (

Table 2). This weather pattern was in agreement with common wind patterns observed in the area for the past two years. The average wind speed was higher (7.1 knotcalmiles/hr) from 15 to 24 March compared to (5.8 knotcalmiles/hr) from 05 to 14 March 2021. The meteorological data pattern indicated that the recipient grain

Amaranth in the north direction was in the downwind side (

Table 2). The highest contamination rate (11.8 %) occurred at 3 m and the lowest (0.55 %) at 150 m. There was a significant difference (p<0.05) between outcrossing rates recorded at 3 m up to 75 m while no significant difference (p>0.05) on cross pollination rates recorded at 100 and 150 m. The adjusted r

2 was 0.9622.

Figure 2.

Exponential decline curve showing genetic purity of grain Amaranthus as a function of distance at Gweru site (2020/21 season).

Figure 2.

Exponential decline curve showing genetic purity of grain Amaranthus as a function of distance at Gweru site (2020/21 season).

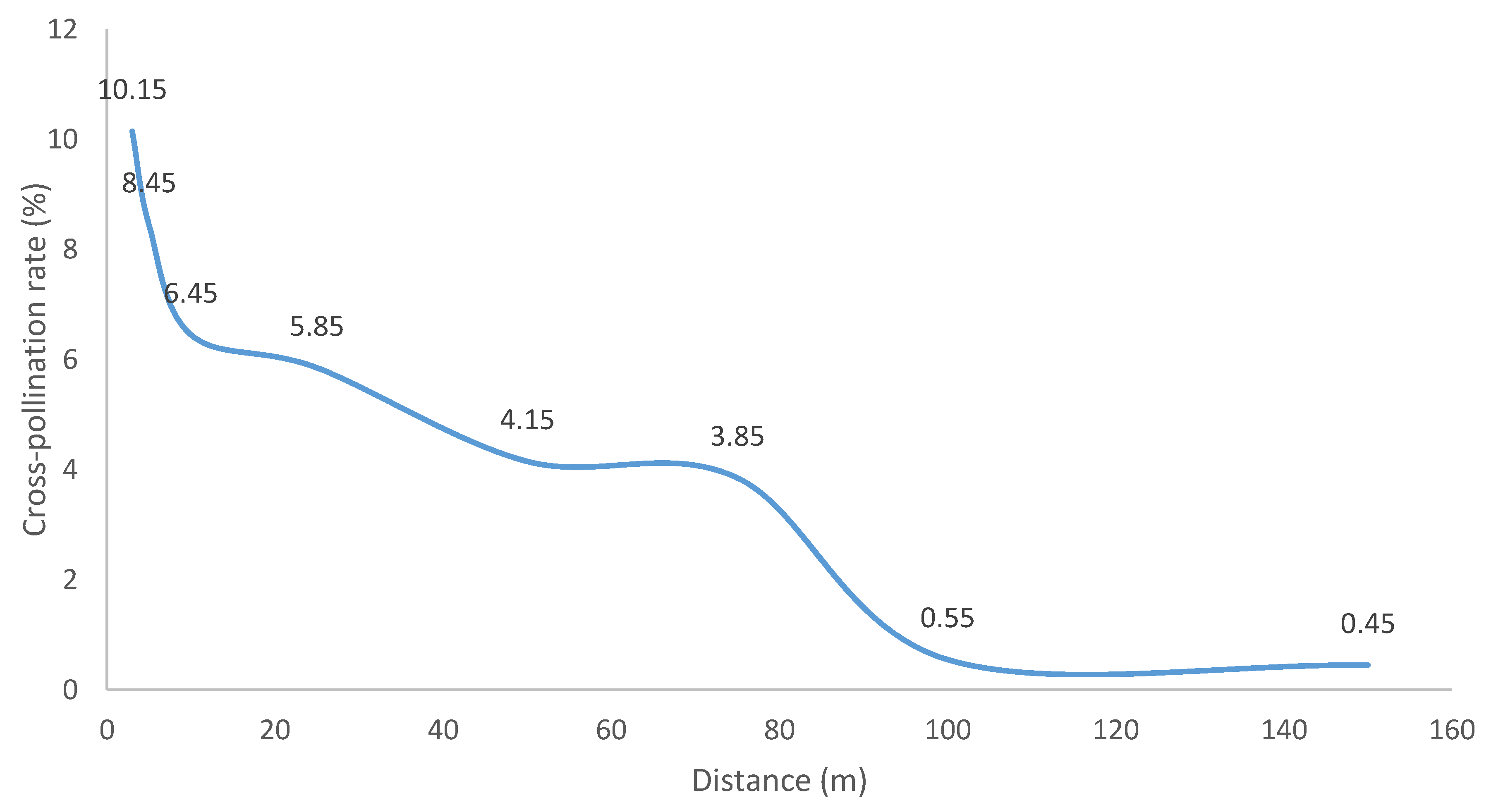

3.2. Effect of Isolation Distance on Genetic Purity of Grain Amaranthus at Bindura Site during 2020/21 Rain Season

At the pollen donor plot flowering started on 6 March 2021 and was delayed by 3 days on the recipient plot (

Table 3). By 10 March, a 50 % pollen shedding was recorded on the donor plot and grain Amaranth started shedding pollen on the 13th of March. The majority of the winds originated from the southern side of the site while a total of 7 days recorded winds of non-distinctive origin (VRB). From 5 to 14 March, an average wind speed of 7.6 knotcalmiles/hr was recorded and the velocity increased to an average of 10 knotcalmiles/hr from the 15th to the 24th of March (

Table 3). The highest cross-pollination rate (10.15 %) was recorded at 3 m and exponentially decreased to 0.45 % at 150 m. There was a significant difference (p<0.05) between cross pollination values recorded at 3 and 75 m and conversely no significant difference (p>0.05) between outcrossing rates recorded at 100 and 150 m. The adjusted r

2 was 0.8478.

Figure 3.

Exponential decline curve showing genetic purity of grain Amaranthus as a function of distance at Bindura site (2020/21 season).

Figure 3.

Exponential decline curve showing genetic purity of grain Amaranthus as a function of distance at Bindura site (2020/21 season).

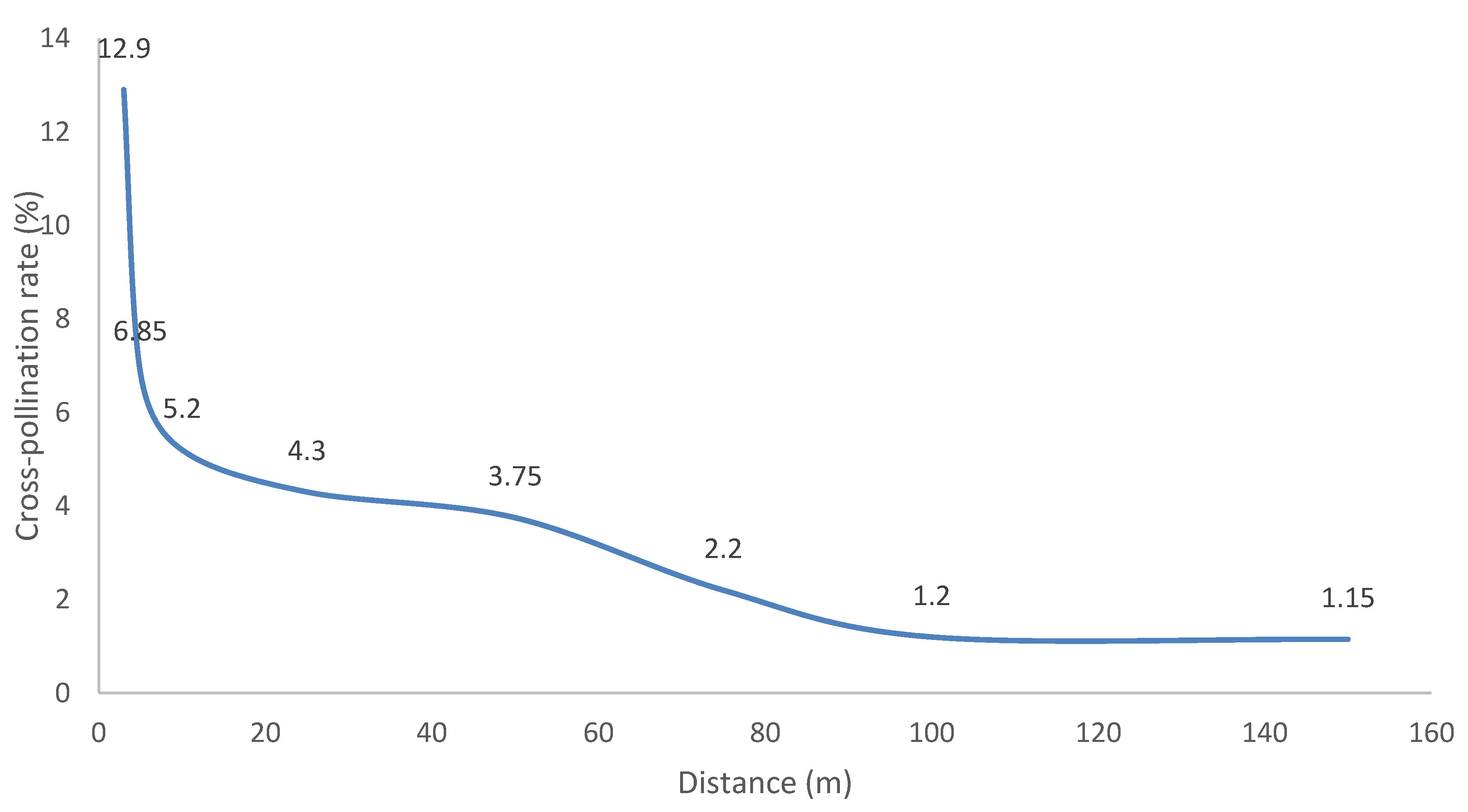

3.3. Effect of Isolation Distance on Genetic Purity of Grain Amaranthus at Shamva Site during 2021/22 Rain Season

High synchronisation during the anthesis period between pollen donor and pollen recipient plants was recorded at the Shamva site (

Table 4). The pollen donor plot started flowering on March 11, 2022 and a day later flowering commenced on the pollen recipient plot. Synchronicity of pollen shedding was also high. The pollen donor plot started shedding pollen on the 14th of March and the pollen recipient commenced on March 15. The site was characterised by variable wind directions. An average wind speed of 6.6 knotcalmiles/hr was recorded from 5 to 14 March and 10.4 knotcalmiles/hr was recorded from 15 to 24 March. The maximum cross-pollination rate (12.9 %) was recorded at 3 m and declined exponentially to 1.15 % at 150 m. There was a significant difference (p<0.05) between cross-pollination rates recorded at 3 m up to 75 m while no significant difference existed between contamination rates at 100 and 150 m. The adjusted r

2 was 0.8413.

Figure 4.

Exponential decline curve showing genetic purity of grain Amaranthus as a function of distance at Shamva site (2021/22 rain season).

Figure 4.

Exponential decline curve showing genetic purity of grain Amaranthus as a function of distance at Shamva site (2021/22 rain season).

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Isolation Distance on Genetic Purity of Grain Amaranthus at Gweru Site during 2020/21 Rain Season

The rate of cross-pollination as a function of distance from the pollen source was well explained by the exponential decline curve (p<0.05) and r2 = 0.9622. The r2 value obtained was very large indicating that 96 % of the variation in cross-pollination rates was attributed to differences in isolation distances. It therefore means, isolation distance significantly affected cross-pollination rates and the model was perfect as only 4 % of the variations in cross-pollination rates can be explained by other variables other than distance. The highest cross-pollination rates can be attributed to the shorter distances from the pollen donor plot as the major factor. High synchronicity in flowering and pollen shedding between the donor and recipient plants contributed to high cross-pollination rates.

However, other variables such as wind direction and wind speed also contributed to such increased contamination rates. All plots on the downwind side recorded high cross-pollination rates which also shows the effect of wind direction on outcrossing rates. These results strongly correlated with empirical work done by Bannert and Stamp [

4], who recorded as high as 15 % cross-pollination rates on the downwind side. Lower cross-pollination rates can be attributed to increased isolation distance as the major contributing factor. Since the cross-pollination data had fitted well to produce a perfect model, outcrossing rates declined with an increase in isolation distance.

Effect of isolation distance on genetic purity of grain Amaranthus at Bindura site during 2020/21 rain season

The contamination rate in the grain Amaranth population with distance to the pollen source was well explained by the exponential decline function (p<0.05) and adjusted r2 = 0.8478. Isolation distance represented 84 % differences on cross-pollination rates and about 16 % of the variations in outcrossing rates were explained by other variables. High cross-pollination can be attributed to shorter distances of the pollen recipient plots from the pollen donor plot [

4]. Apart from close-range distances, high cross-pollination can be attributed to the high synchronization of flowering and pollen shedding between the pollen donor and recipient populations. Wind speed and direction also contributed to high cross-pollination rates as the highest contamination was recorded on the downwind side. However, low cross-pollination rates can be attributed to greater distances of the pollen recipient from the donor plot. And again wind direction significantly contributed to reduced outcrossing rates as the plots that recorded the least values were on the upwind direction.

4.2. Effect of Isolation Distance on Genetic Purity of Grain Amaranthus at Shamva Site during 2021/22 Rain Season

The cross-pollination data fitted well to produce a perfect model (p<0.05) and adjusted r2 = 0.8413. The r2 value is very large therefore indicating that about 84 % of the variation in outcrossing rates was significantly explained by differences in isolation distances as the major factor and only 16 % was explained by other variables. The highest cross-pollination rates can be attributed to the short distance between the pollen donor and recipient plants as the exponential curve indicated an increase in contamination rate due to a decrease in isolation distance. The high synchronisation during anthesis between the pollen donor and pollen recipient also contributed to high outcrossing rates as the donor plant was earlier with one day for both flowering and pollen shedding.

Cross-pollination rates at both minimum and maximum measured distances were high at Shamva site, a scenario that can be attributed to high pollinator pressure due to a bio-diverse environment. Again the prevailing winds during flowering were variable therefore all directions were both upwind and downwind sides a case that can be attributed to increased outcrossing rates at both minimum and maximum distances investigated in this study. Low cross-pollination rates can be attributed to the closeness of the pollen recipient plants to the donor plot as the decline curve indicated lower outcrossing rates with increased isolation distance.

5. Conclusion

From the results obtained in this study, it can be concluded that the genetic purity of seeds is dependent on distance from the pollen donor as all of the results across the sites fitted well into the exponential decline curve. Seed purity increases with an increase in isolation distance and exponentially decreases as we go closer to the pollen donor. Isolation distances of 100 and 150 m produce the most pure seed with less than 2 % cross-pollination rate. Furthermore, it can be concluded that genetic purity analysis using morphological markers like seed color may be used as a potential tool for resolving the problems that arise in seed certification programs owing to genetic impurity and also provide a rapid determination of the genetic purity of grain Amaranthus.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, Tendai Madanzi, Canaan Nyambo and Francis Mukoyi. Methodology Francis Mukoyi, Canaan Nyambo, Nomsa Shoko and Tendai Madanzi. Software Canaan Nyambo, Francis Mukoyi and Nomsa Shoko.; validation, Raymond Mugandani, Wendy Mutsa Pilime and Paramu Mafongoya., writing—original draft preparation, Canaan Nyambo and Wendy Mutsa Chiota.; writing—review and editing James Chitamba, Raymond Mugandani and Paramu Mafongoya.; supervision, Tendai Madanzi.; Nomsa Shoko,; funding acquisition, All Authors.

Funding

This research received no external funding. All funding was contributed equally by the authors. The Midlands State university and the Zimbabwe Republic Police Farms used in the study provided resources such as fertilisers and paid for labour.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this study was used to write a dissertation for Canaan Nyambo’s BSc in Agronomy. The submitted copies of the dissertation are kept in the Department of Agronomy and Horticulture at the Midlands State University. Raw data is attached to this manuscript submission.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Midlands State University and the Zimbabwe Republic Police’s Worcestershire Farm in Gweru and at Stella Farm for providing resources and support for this study over the two experimental seasons. We also want to thank Mrs Mutangabende, the laboratory supervisor at Seed Services Harare for the support she offered in carrying out physical purity analysis. Financial support for the study was equally contributed by authors involved in the study. There is no conflict of interest to report on this study. No innovations are expected from this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Agong S. G. and Ayiecho P. O. (1991). The rate of outcrossing in grain Amaranths. Journal of Plant Breeding 107: 156-160. [CrossRef]

- Aheto D. W. and Reuter H. (2011). A modelling assessment of gene flow in smallholder agriculture in West Africa. Journal Environmental Sciences Europe 23; 9.

- Alemayehu F. R., Bendevis M. A. and Jacobsen S. E. The potential for utilising the seed crop Amaranth in East Africa as an alternative crop to food security and climate change mitigation. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science 2015, 20, 321-9.

- Bannert M. and Stamp P. (2007). Cross pollination of maize at long distance. European Journal Agronomy 27, 44 - 51. [CrossRef]

- Brenner D. M. Johnso W. G., Sprague C. L., Tranel P. J. and Young B. G. (2013). Crop-weed hybrids are more frequent for the grain Amaranth-Plainsman: Genetic resources and crop evolution 60, 2201-2205.

- Ellstrand, N.C. 1988. Pollen as a vehicle for the escape of engineered genes?. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 3(4), pp.S30-S32. [CrossRef]

- Espitia-Rangel E. (2018). Breeding of grain Amaranth. Journal of Amaranth Biology, Chemistry, and Technology 60, 23-38.

- Forrest, J.R. 2014. Plant size, sexual selection, and the evolution of protandry in dioecious plants. The American Naturalist, 184(3), pp.338-351. [CrossRef]

- Jain S. K., Hauptil H. and Vaidya K. R. (1982). Outcrossing rate in grain Amaranths. Journal of Heredity 73, 71-72. [CrossRef]

- Jianyang L., Davis A. S. and Tranel P. J. (2012). Pollen biology and dispersal dynamics in waterhemp (Amaranthus tuberculatus). Journal of Weed Science 60, 416-422.

- Kauffman, C.S. and Weber, L.E. 1990. Grain amaranth. Advances in new crops. Timber Press, Portland, OR, pp.127-139.

- Kimenye L. (2014). Improving access to quality seeds in Africa. CABI Study Brief 7.

- Luna V, S., Figueroa M, J., Baltazar M, B., Gomez L, R., Townsend, R. and Schoper, J.B. 2001. Maize pollen longevity and distance isolation requirements for effective pollen control. Crop Science, 41(5), pp.1551-1557.

- Mabaya E., Mujaju C., Nyakanda P. and Mungoya M. (2017). The African Seed Access Index (TASAI), Zimbabwe Brief 2017. Available at: tasa.org/reports.

- Mccormack J. H. (2004). Principles and practices of isolation distances for seed crops: an organic seed production manual for seed growers in the Mid-Atlantic and Southern US. Earlyville, Virginia, America. p. 3.

- Ndinya, C., Onyango, E., Dinssa, F.F., Odendo, M., Simon, J.E., Weller, S., Thuranira, E., Nyabinda, N. and Maiyo, N. (2020). Participatory variety selection of three African leafy vegetables in Western Kenya. Journal of Medicinally Active Plants, 9(3), pp.145-156.

- Nyamapfene K. (1991). The soils of Zimbabwe. Nehanda Publishers, Harare, Zimbabwe.

- Oyekale K. O. (2014). Growing an effective seed management system: A case study of Nigeria. Journal of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences 3, 345-354.

- Raybould, A.F. and Gray, A.J., 1993. Genetically modified crops and hybridization with wild relatives: a UK perspective. Journal of Applied Ecology, pp.199-219.

- Raymond A. T. G. (2011). Agricultural seed production. CABI publishers, Croydon, America. p. 67.

- Rehman, I.U., Ayesha, N., Anam, K., Khalid, A., Ali, L., Nazir, H., Burhan, Z. and Sadique, U. 2024. Improving of Amaranth (Amaranthus Spp.) and Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) by Genetic Resources. Asian Journal of Research in Crop Science, 9(2), pp.1-9. [CrossRef]

- Sosnoskie L. M., Webster T. M., Dales D., Rains G. C., Grey T. L. and Culpepper A. S. (2017). Pollen Grain Size, Density, and Settling Velocity for Palmer Amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Vargas-Ortiz E., Espitia-Rangel E., Tiessen A. and Delano-Frier J. P. (2013). Grain Amaranths are defoliation tolerant crop species capable of utilizing stem and root carbohydrate reserves to sustain vegetative and reproductive growth after leaf loss. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology 5, 6-15. [CrossRef]

- 24. Vincent V. and Thomas R. G. (1961). An Agricultural Survey of Southern Rhodesia, Agro-Ecological Survey, 1. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).