Submitted:

27 June 2024

Posted:

28 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experiment

3. Results

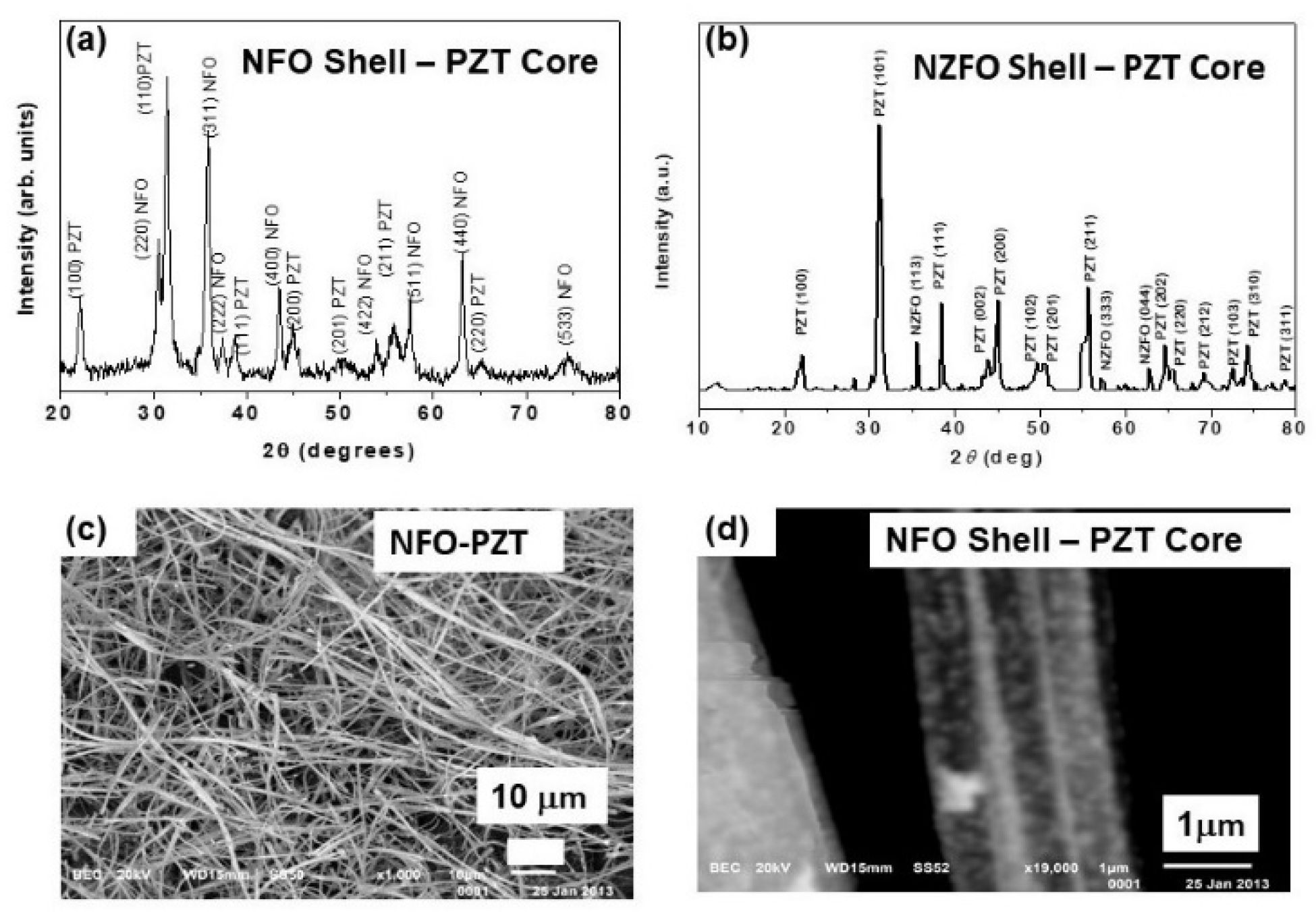

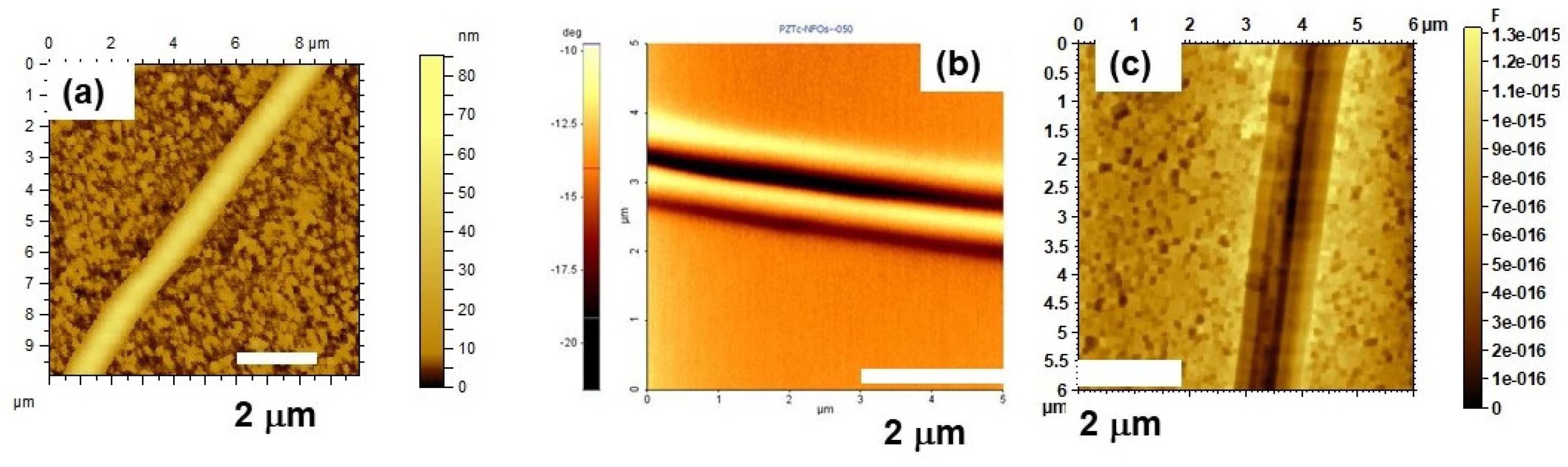

3.1. Structural Measurements

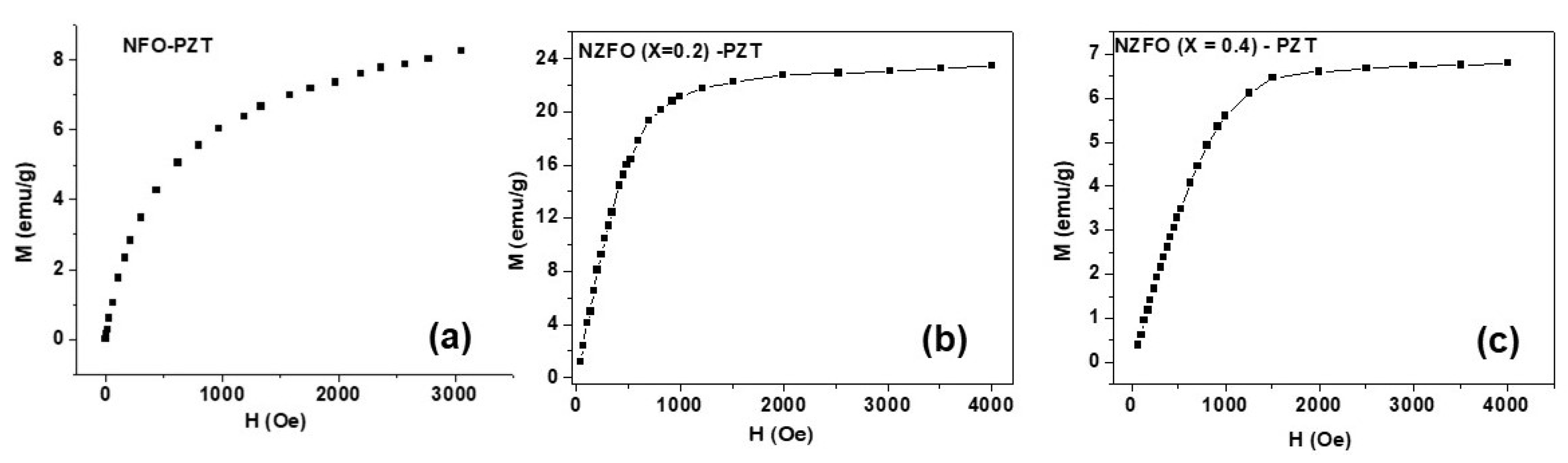

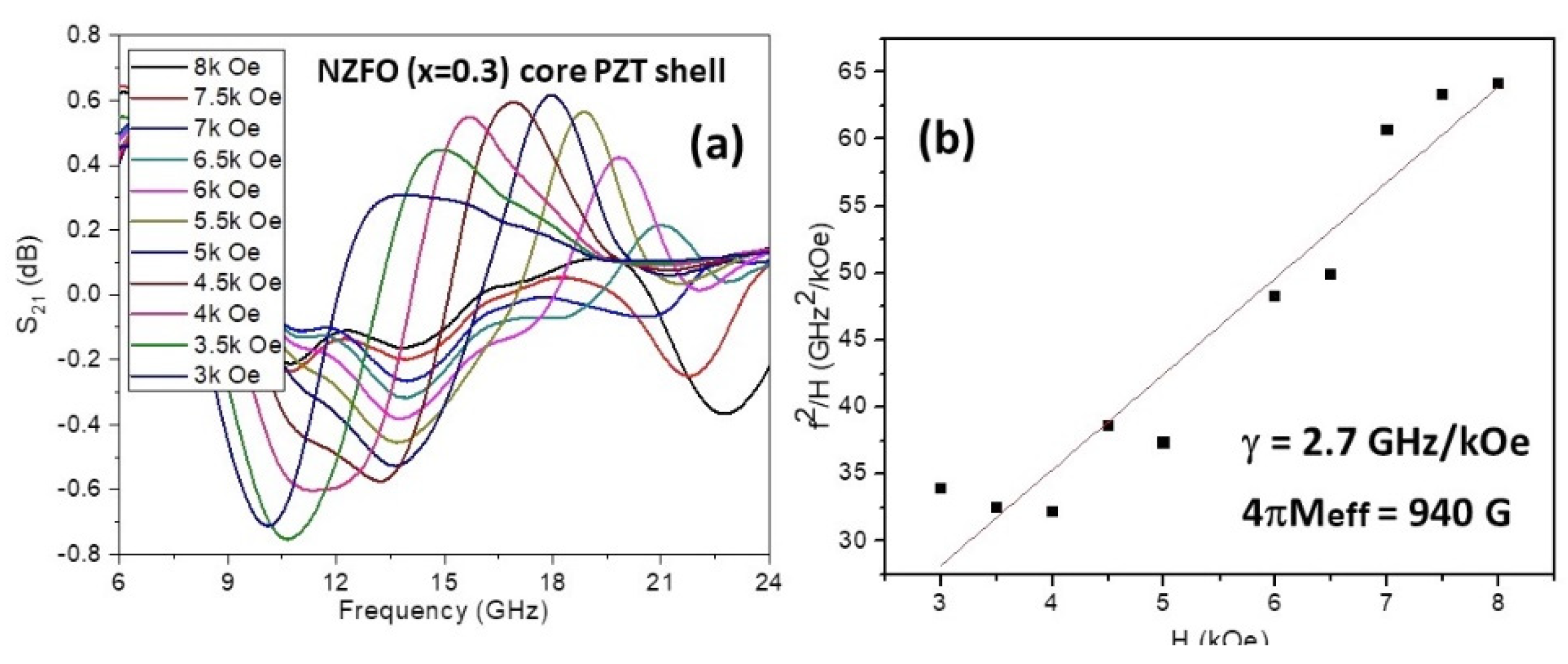

3.2. Magnetic Characterization

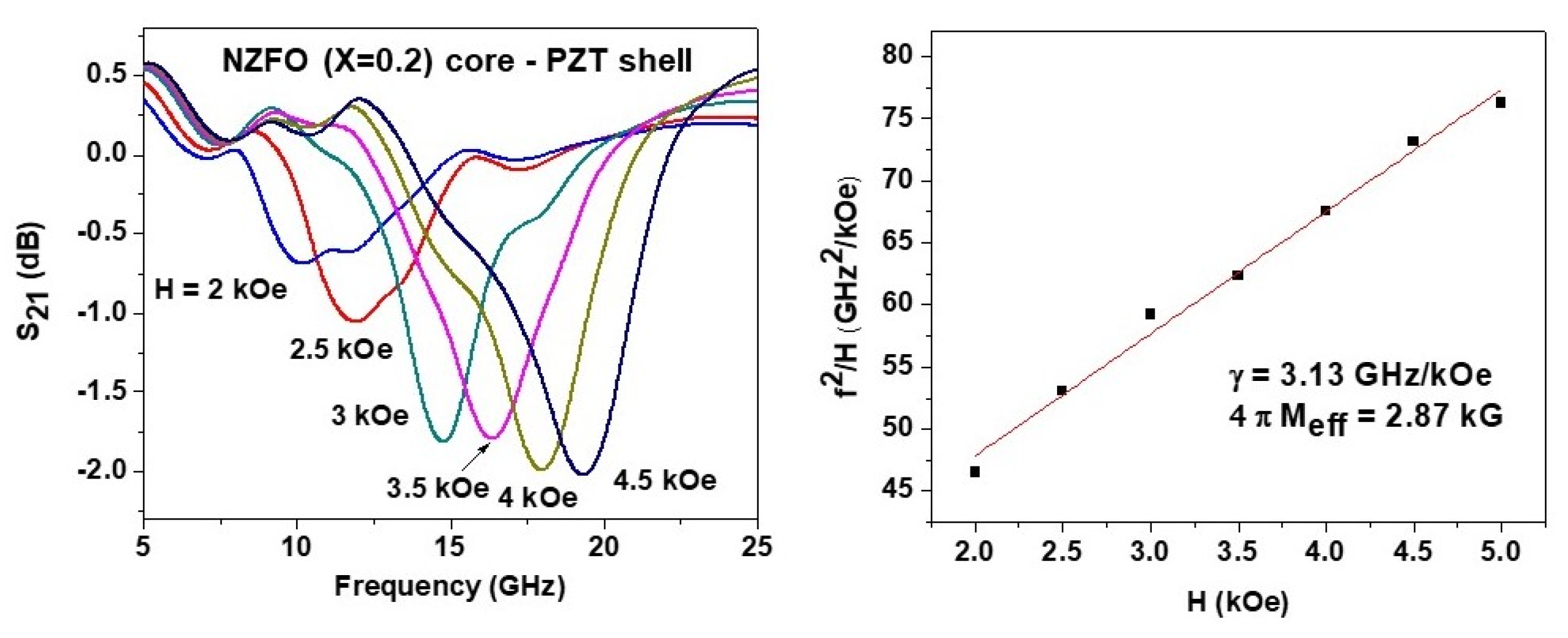

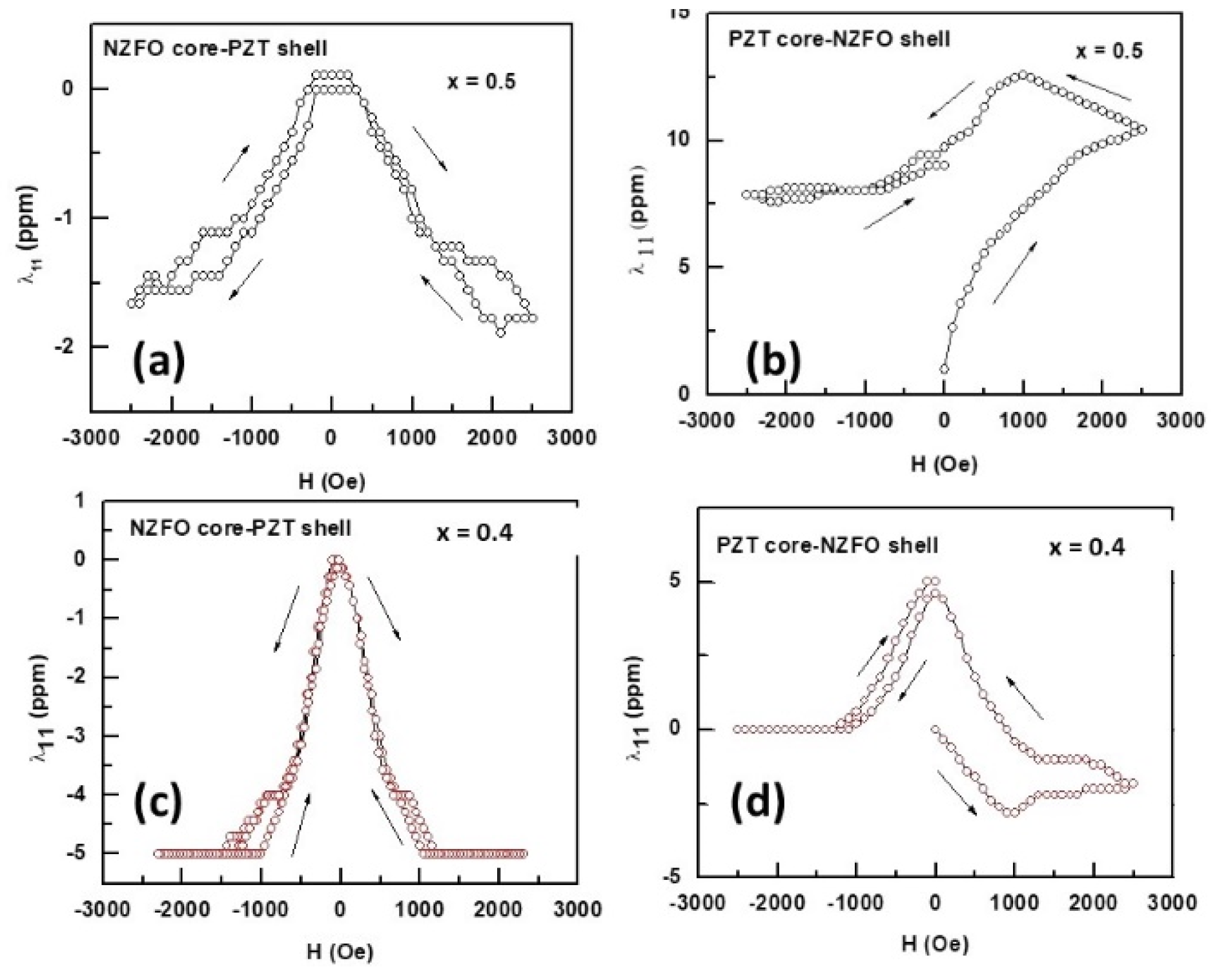

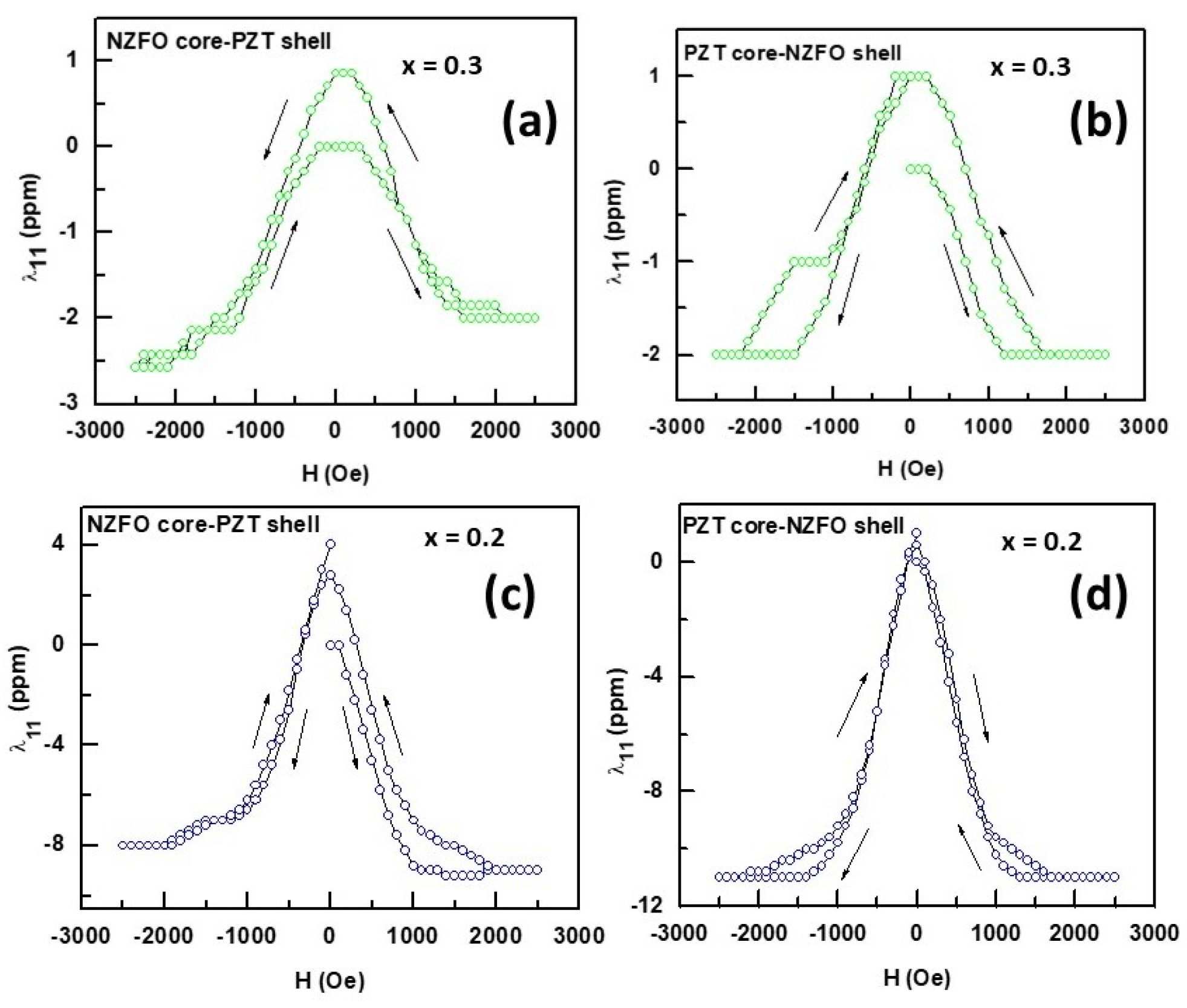

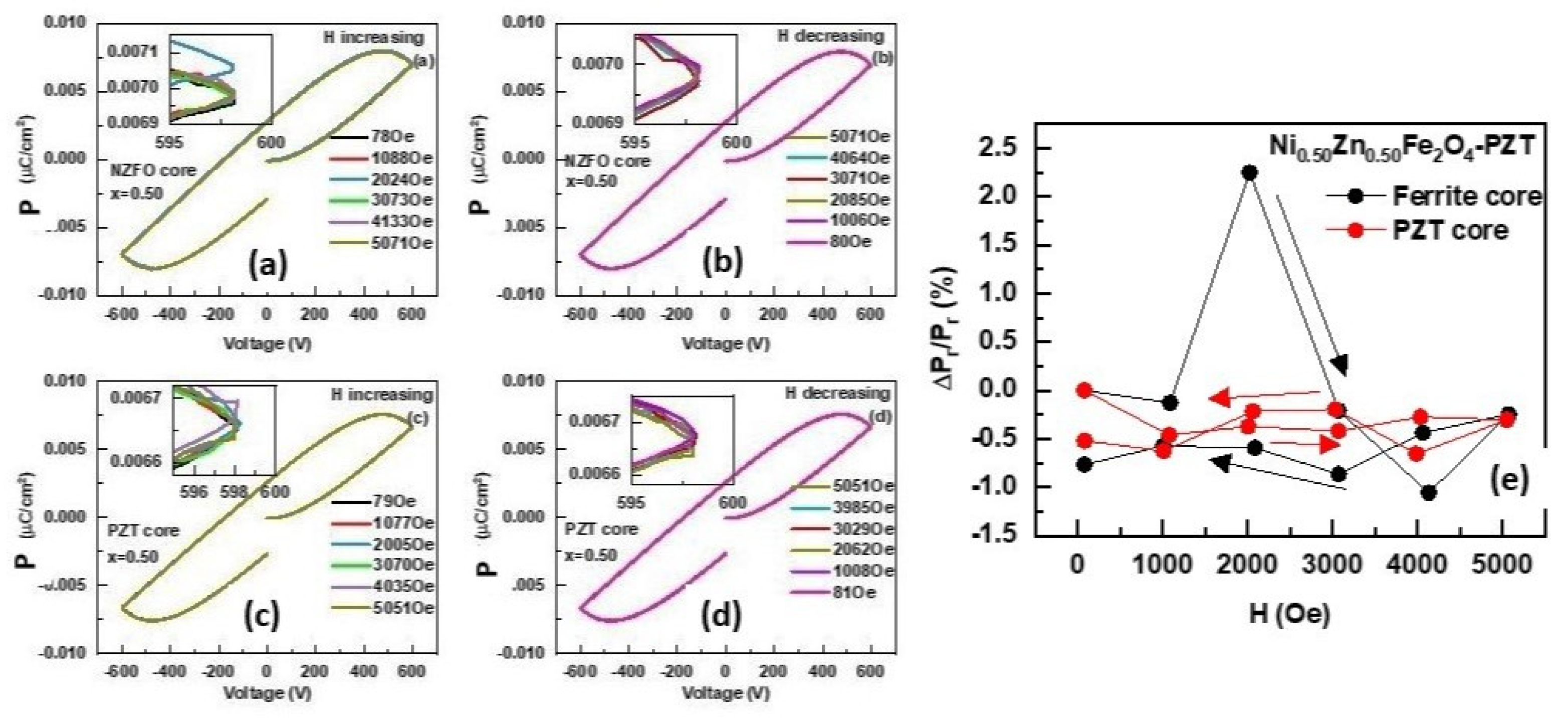

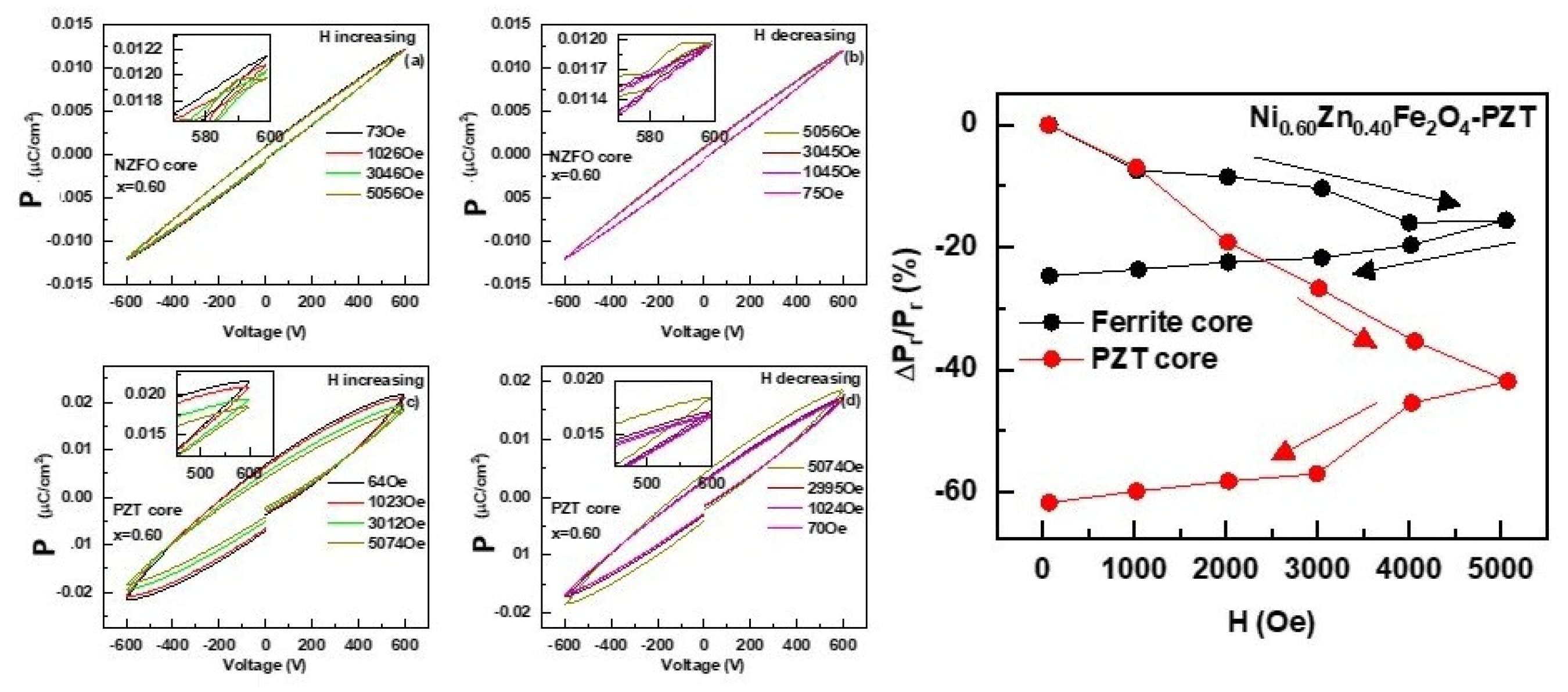

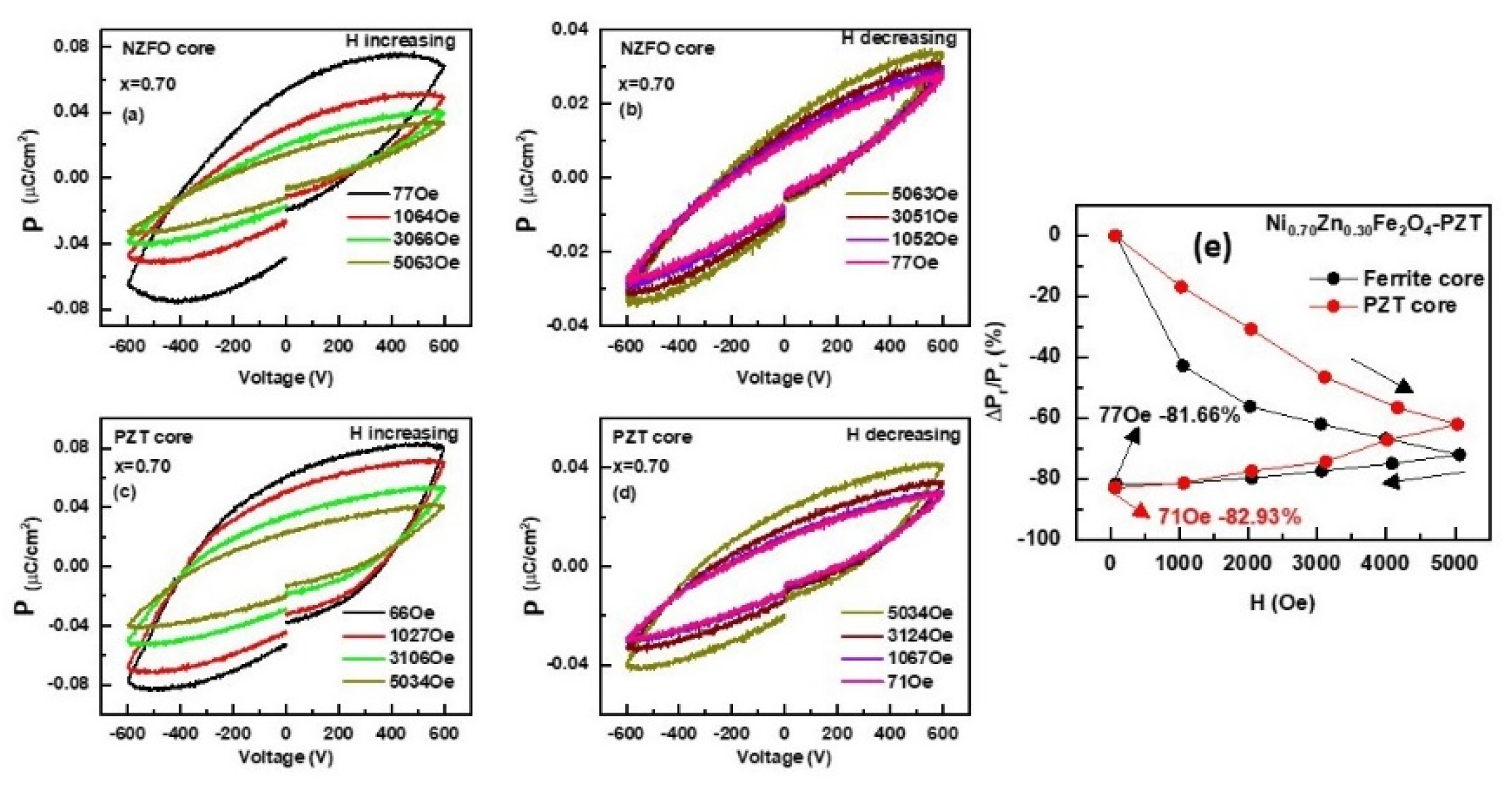

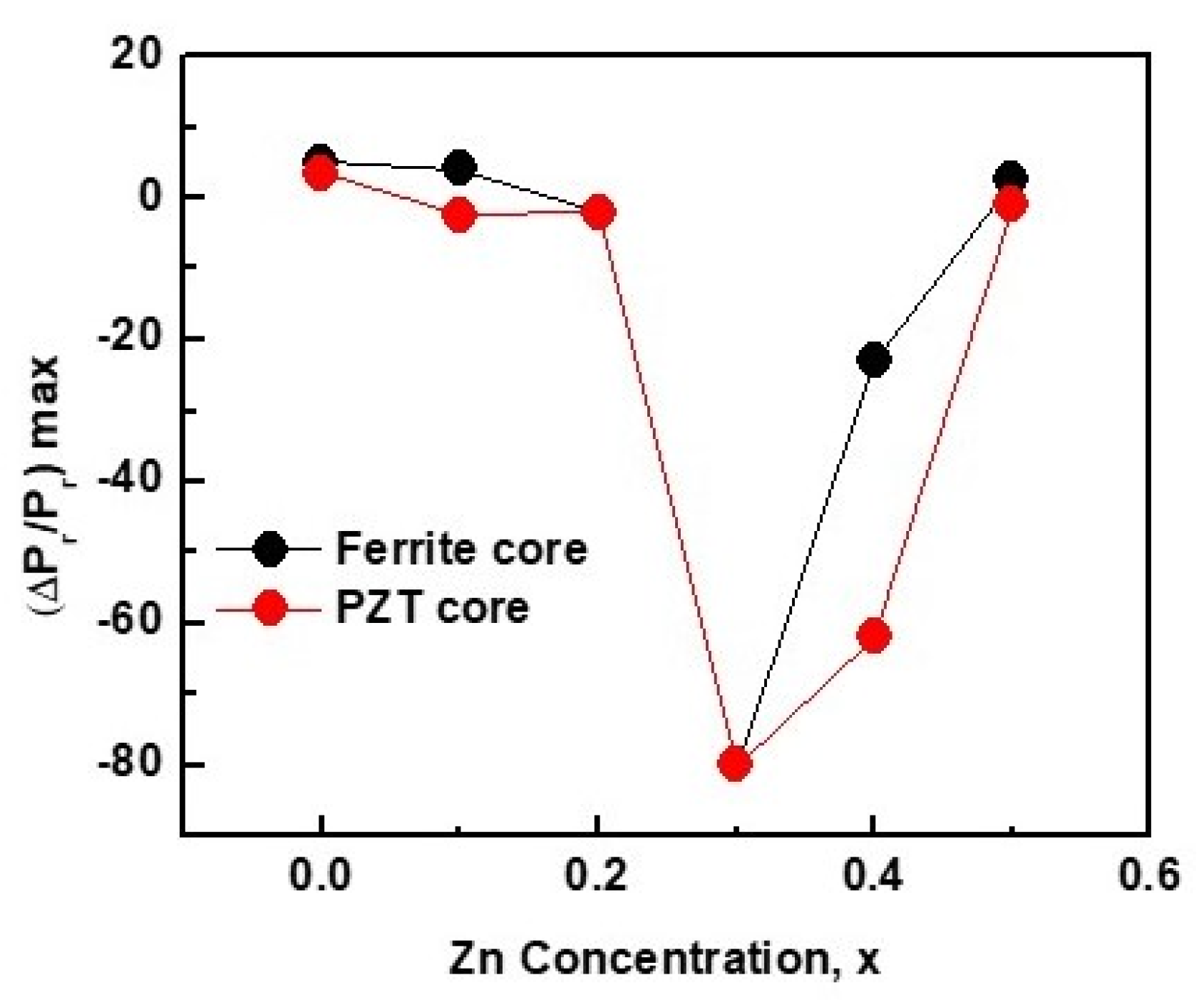

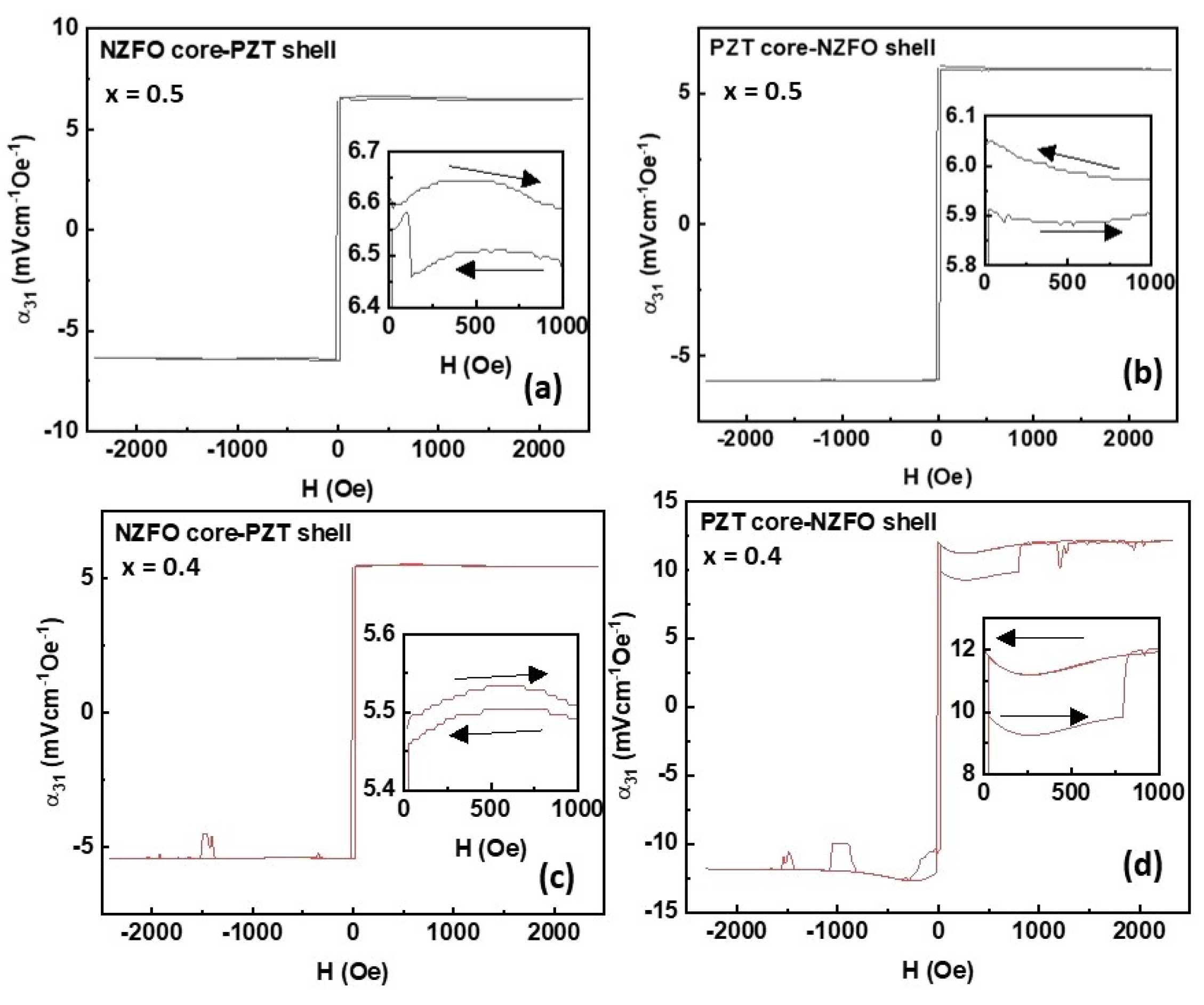

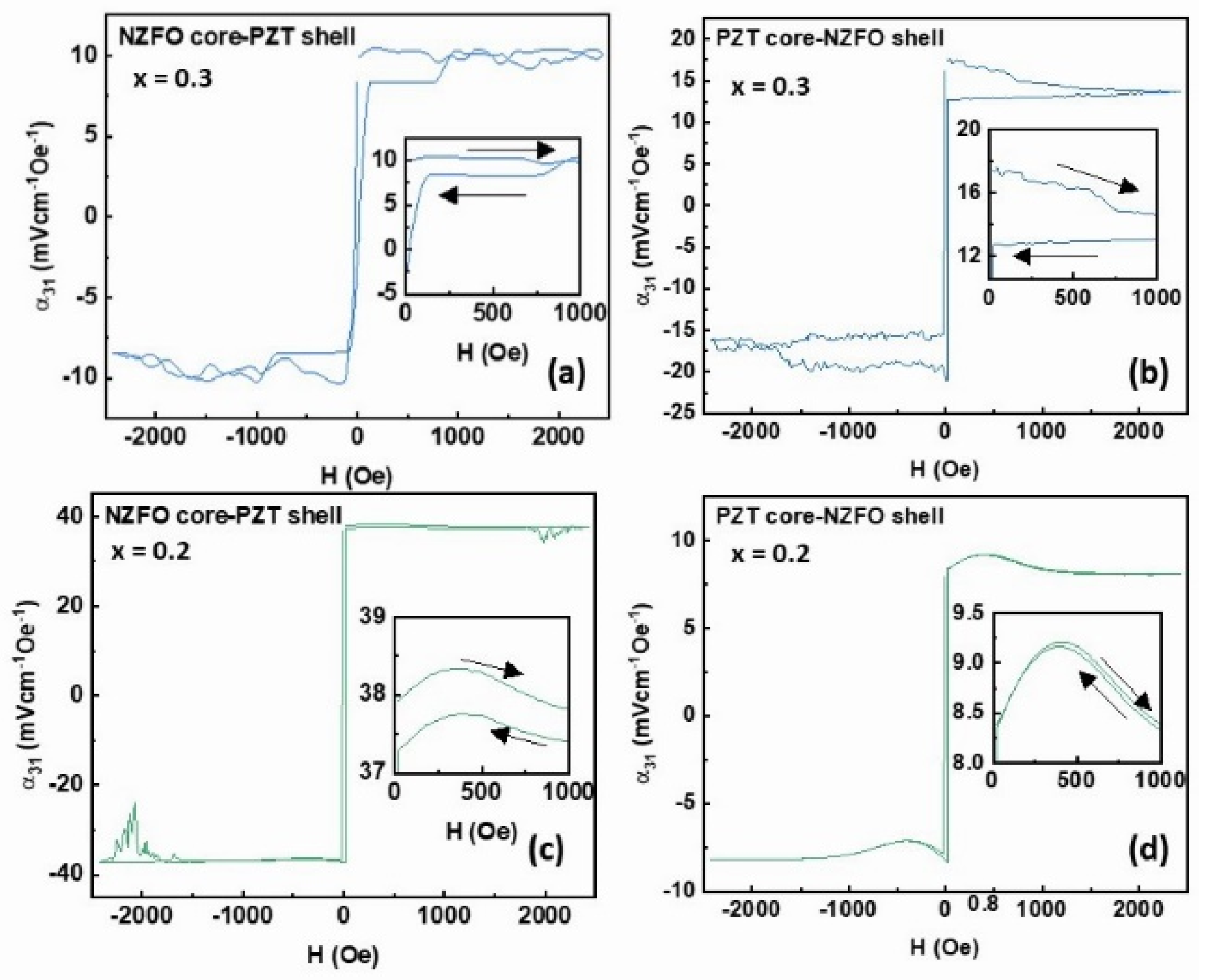

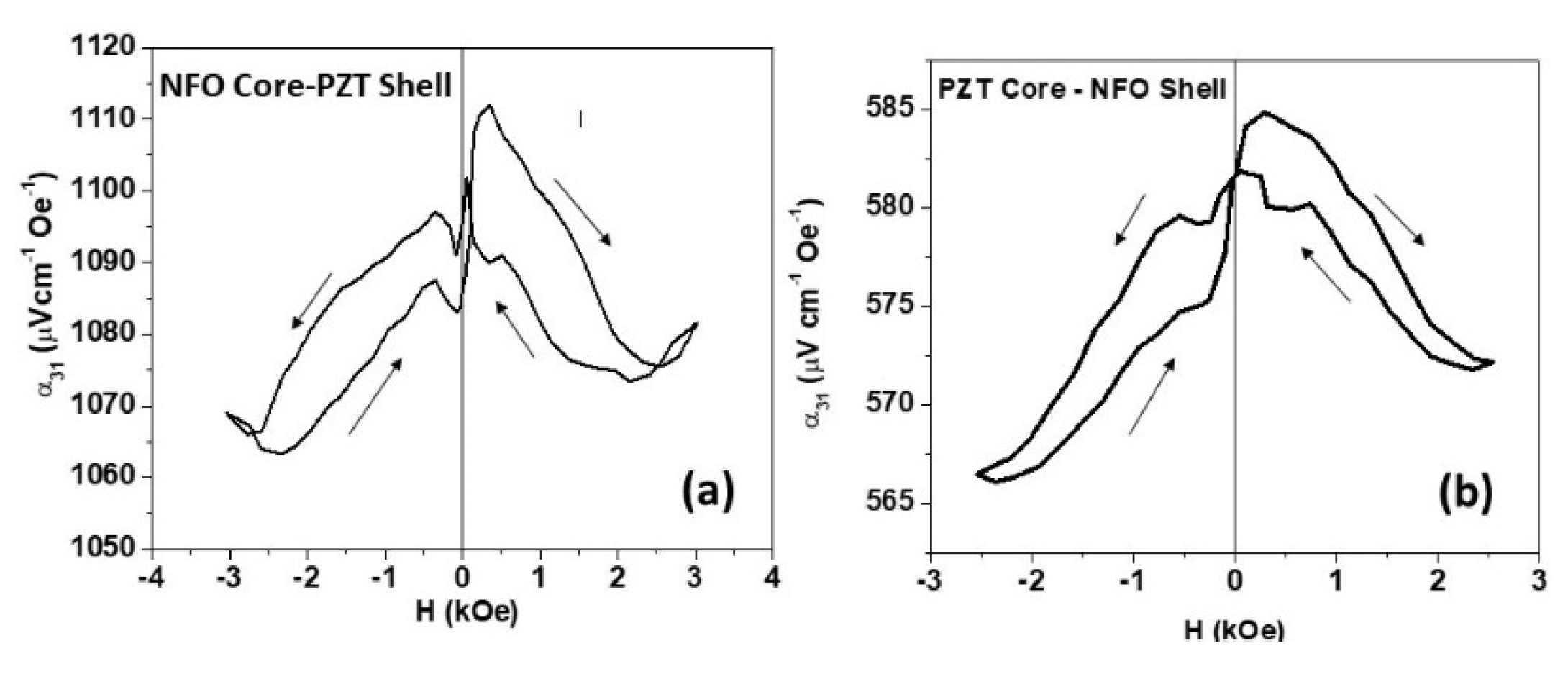

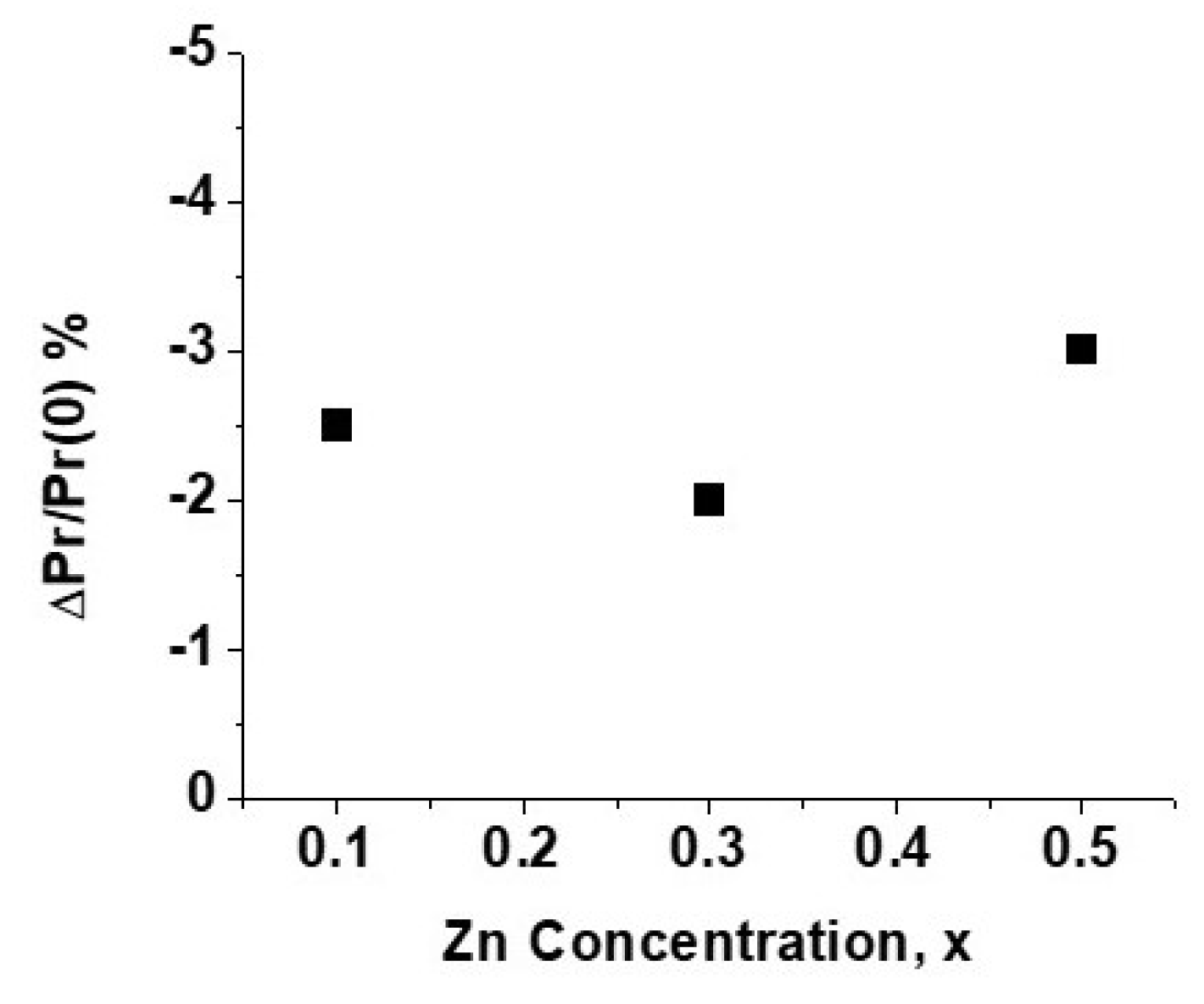

3.3. Ferroelectric and Magneto-Electric Characterization

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, N.; Priya, S.; Srinivasan, G. (Eds.) Composite magnetoelectrics: materials, structures, and applications; Elsevier: New York, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.M.; Nan, C.W. Opportunities and challenges for magnetoelectric devices. APL Materials. 2019, 7, 080905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichurin, M.; Petrov, R.; Sokolov, O.; Leontiev, V.; Kuts, V.; Kiselev, D.; Wang, Y. Magnetoelectric magnetic field sensors: A review. Sensors. 2021, 21, 6232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera Diez, L.; Kruk, R.; Leistner, K.; Sort, J. Magnetoelectric materials, phenomena, and devices. APL Materials. 2021, 9, 05040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narita, F.; Fox, M. A review on piezoelectric, magnetostrictive, and magnetoelectric materials and device technologies for energy harvesting applications. Advanced Engineering Materials. 2018, 20, 1700743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annapureddy, V.; Palneedi, H.; Hwang, G.T.; Peddigari, M.; Jeong, D.Y.; Yoon, W.H.; Kim, K.H.; Ryu, J. Magnetic energy harvesting with magnetoelectrics: an emerging technology for self-powered autonomous systems. Sustainable Energy & Fuels. 2017, 1, 2039–2052. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, C.M.; Li, J.; Viehland, D.; Zhuang, X. A review on applications of magnetoelectric composites: From heterostructural uncooled magnetic sensors, energy harvesters to highly efficient power converters. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics. 2018, 51, 263002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Gao, J.Q.; Li, M.H.; Shen, Y.; Hasanyan, D.; Li, J.F.; Viehland, D. A review on equivalent magnetic noise of magnetoelectric laminate sensors. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 2014, 372, 20120455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Geng, L.D.; Tan, Y.; Ma, J.; Zhang, L.; Sanghadasa, M.; Ngo, K.; Ghosh, A.W.; Wang, Y.U.; Priya, S. Colossal tunability in high frequency magnetoelectric voltage tunable inductors. Nature communications. 2018, 9, 4998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Chen, H.; Sun, N.X. Magnetoelectric materials and devices. APL Materials. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palneedi, H.; Maurya, D.; Kim, G.Y.; Annapureddy, V.; Noh, M.S.; Kang, C.Y.; Kim, J.W.; Choi, J.J.; Choi, S.Y.; Chung, S.Y.; Kang, S.J. Unleashing the full potential of magnetoelectric coupling in film heterostructures. Advanced Materials. 2017, 29, 1605688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Dong, C.; Chen, H.; Wang, J.; Wei, Y.; Zaeimbashi, M.; He, Y.; Matyushov, A.; Sun, C.; Sun, N. A review of thin-film magnetoelastic materials for magnetoelectric applications. Sensors. 2020, 20, 1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, S.H.; Liu, Y.Y.; Li, J.Y. Synthesis, microstructures, and magnetoelectric couplings of electrospun multiferroic nanofibers. Frontiers of Physics. 2012, 7, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viehland, D.; Li, J.F.; Yang, Y.; Costanzo, T.; Yourdkhani, A.; Caruntu, G.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, T.; Li, T.; Gupta, A.; Popov, M.; et al. Tutorial: Product properties in multiferroic nanocomposites. Journal of Applied Physics 2018, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, R.Q. Growth of nanowires. Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports. 2008, 60, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, M.; Singh, R.; Negi, P.; Tiwari, K.; Singh, Y. A comprehensive review on carbon nano-tube synthesis using chemical vapor deposition. Materials Today: Proceedings. 2021, 46, 11250–11253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhu, J.; Cheng, H.; Li, G.; Cho, H.; Jiang, M.; Gao, Q.; Zhang, X. Developments of advanced electrospinning techniques: A critical review. Advanced Materials Technologies. 2021, 6, 2100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piraux, L. Magnetic nanowires. Applied Sciences. 2020, 10, 1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Yang, C.; Chen, X.; Xue, W.; Hutchins-Crawford, H.J.; Yu, Q.; Topham, P.D.; Wang, L. A review on electrospun magnetic nanomaterials: methods, properties and applications. Journal of Materials Chemistry C. 2021, 9, 9042–9082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Kang, X.; Sang, Y.; Liu, H. One-dimensional ferroelectric nanostructures: synthesis, properties, and applications. Advanced Science. 2016, 3, 1500358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S. Ferrolectric nanofibers: principle, processing and applications. Advanced Materials Letters. 2013, 4, 522–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Dai, J.; Feng, W.; Cheng, C.; Huang, D. SrFe12O19@ ZnFe2O4 core–shell composite fiber with enhanced exchange coupling interaction. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials. 2023, 568, 170278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Wen, X.; Feng, W.; Cheng, C.; Huang, D. Correlation of the heat treatment feature and magnetic properties of the SrFe12O19@ ZnFe2O4 core-shell nanofibers. Materials Chemistry and Physics. 2022, 276, 125393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Wen, X.; Dai, J.; Wang, Q.; Liu, H.; Li, Z. Magnetic Properties and Exchange Coupling Effects of SrFe12O19@ MFe2O4 (M= Co, Ni, Zn) as Hard-Soft Magnetic Ferrite Core–Shell Nanofibers. Journal of Superconductivity and Novel Magnetism. 2023, 36, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, T. Magneto-electric effects in coaxial nanofibers of hexagonal ferrites and ferroelectrics. Ferroelectrics. 2023, 611, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Zhou, Z.; Song, F.; Meng, X. Synthesis and magnetic properties of nanocomposite Ni1− x CoxFe2O4–BaTiO3 fibers by organic gel-thermal decomposition process. Journal of sol-gel science and technology. 2010, 53, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schileo, G. Recent developments in ceramic multiferroic composites based on core/shell and other heterostructures obtained by sol–gel routes. Progress in Solid State Chemistry. 2013, 41, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Li, X.; Imrane, H.; Chen, Y.; Goodrich, T.; Cai, Z.; Ziemer, K.S.; Huang, J.Y.; Sun, N.X. Synthesis of ordered arrays of multiferroic NiFe2O4-Pb (Zr0.52 Ti0.48) O3 core-shell nanowires. Applied physics letters. 2007, 90, 152501. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J.C.; Shen, X.Q.; Min, C.Y.; Meng, X.F.; Liang, Q.R. Fabrication and characterization of heterostructural CoFe2O4/Pb (Zr0.52 Ti0.48) O3 nanofibers by electrospinning. Journal of composite materials. 2010, 44, 2135–2144. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S.H.; Liu, Y.Y.; Li, J.Y. Synthesis, microstructures, and magnetoelectric couplings of electrospun multiferroic nanofibers. Frontiers of Physics. 2012, 7, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viehland, D.; Li, J.F.; Yang, Y.; Costanzo, T.; Yourdkhani, A.; Caruntu, G.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, T.; Li, T.; Gupta, A.; Popov, M.; et al. Tutorial: Product properties in multiferroic nanocomposites. Journal of Applied Physics 2018, 124, 061101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, P.; Ge, B.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, T.; Srinivasan, G. Strain-mediated magneto-electric effects in coaxial nanofibers of Y/W-type hexagonal ferrites and ferroelectrics. Journal of Composites Science. 2021, 5, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrichs, L.F.; Mu, X.; Scherer, T.; Gerhards, U.; Schuppler, S.; Nagel, P.; Merz, M.; Kübel, C.; Fawey, M.H.; Hansen, T.C.; Hahn, H. First-time synthesis of a magnetoelectric core–shell composite via conventional solid-state reaction. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 15677–15686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sreenivasulu, G.; Popov, M.; Zhang, R.; Sharma, K.; Janes, C.; Mukundan, A.; Srinivasan, G. Magnetic field assisted self-assembly of ferrite-ferroelectric core-shell nanofibers and studies on magneto-electric interactions. Applied Physics Letters 2014, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, J.; Wijn, H. P. J. Ferrites; Wiley: New York, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, V.G. Modern microwave ferrites. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 2011, 48, 1075–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, P.; Taneja, S.; Chahar, D.; Ravelo, B.; Thakur, A. Recent advances on synthesis, characterization and high frequency applications of Ni-Zn ferrite nanoparticles. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 2021, 530, 167925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, K. I.; Tsuya, N. Magnetostriction measurements of Ni-Zn ferrite single crystals. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids 1975, 36, 463–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasulu, G.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, R.; Popov, M.; Petrov, V.; Srinivasan, G. Multiferroic core-shell nanofibers, assembly in a magnetic field, and studies on magneto-electric interactions. Materials 2017, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, S.K.; Hemalatha, J. Direct magnetoelectric and magnetodielectric studies of electrospun Ba2Ni2Fe12O22–Pb (Zr0. 52 Ti0. 48) O3 core–shell nanofibers. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials. 2022, 564, 170174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.K.; Hemalatha, J. Synthesis and characterization of magnetoelectric Ba2Zn2Fe12O22–PbZr0. 52 Ti0. 48 O3 electrospun core–shell nanofibers for the AC/DC magnetic field sensor application. Applied Physics A. 2024, 130, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).