1. Introduction

Resurrection plants are highly adapted to withstand desiccation tolerance and can revive from vegetative tissue with a relative water content of less than 10% or a water potential of less than -100 MPa [

1]. Present on all continents except Antarctica, resurrection plants have been able to pioneer extreme environments such as inselbergs, which experience periodic or seasonal drying [

2,

3]. On the African continent, these plants are present in deserts and semi-deserts to montane rainforests and can have a broad geographic range or be highly localised [

3,

4].

Craterostigma plantagineum, a dicotyledonous plant, covers a large area from East Africa extending into Niger, Sudan, Ethiopia and Southern Africa that is characterised by restricted water availability and a low-to-moderate elevation. In contrast,

Lindernia brevidens, a related desiccation-tolerant plant described in 2008, is localized to the montane rainforests of Tanzania and Kenya, which experiences high precipitation (>1500 mm per year). A close relative of

L. brevidens,

L. subracemosa, occupies a similar habitat in western Tanzania, Kenya, Eastern Congo and Ethiopia, is desiccation sensitive [

4].

Resurrection plants use various strategies to achieve desiccation tolerance, be it constitutive or inducible and involving changes to primary and secondary metabolites [

3]. The plant cell wall, comprised mainly of cellulose, hemicellulose and pectin polymers, constitutes a significant proportion of the cell biomass and is responsible for maintaining structural integrity. Therefore, any strategies for desiccation tolerance will likely incorporate dynamic changes to the cell wall to preserve cell integrity during periods of desiccation and subsequent hydration [

5]. In

Oryza sativa, cell wall irreversibility has been identified as a limiting factor to drought tolerance, highlighting the dynamic nature of the changes that occur in the cell wall during water deficit stress [

6]. Understanding these mechanisms in resurrection plants will expand the repertoire available to researchers in the development of drought-tolerant crop plants and novel cell-wall-based biomaterials [

7].

The desiccation of plant vegetative tissues leads to cell plasmolysis, which generates mechanical stress. In resurrection plants, such mechanical stress can be reduced through vacuolation and reversible cell wall folding. The latter involves dynamic changes of the cell wall polysaccharide composition. These changes include the increased presence of de-methylesterified homogalacturonan upon desiccation, which has been proposed to strengthen the cell wall. In

C. plantagineum, xyloglucan levels have been shown to increase upon desiccation which is thought to provide increased strength. Furthermore, changes to rhamnogalacturonan-II levels have also been reported for

C. plantagineum [

8]. These changes are required to enable reversible cell wall expansion and folding during dissection. Cell wall folding has also been reported in

L. brevidens and

L. subracemosa, in spite of the latter being desiccation-sensitive [

9].The literature provides limited information on which of the changes that occur in cell wall composition and architecture during desiccation and hydration are associated with desiccation tolerance. In the present study we compare the cell wall composition and architectural properties of two desiccation tolerant plants,

C. plantagineum and

L. brevidens, with the desiccation-sensitive

L. subracemosa with the aim of establishing which cell wall features determine desiccation tolerance.

2. Results

2.1. Analysis of Cell Wall Composition

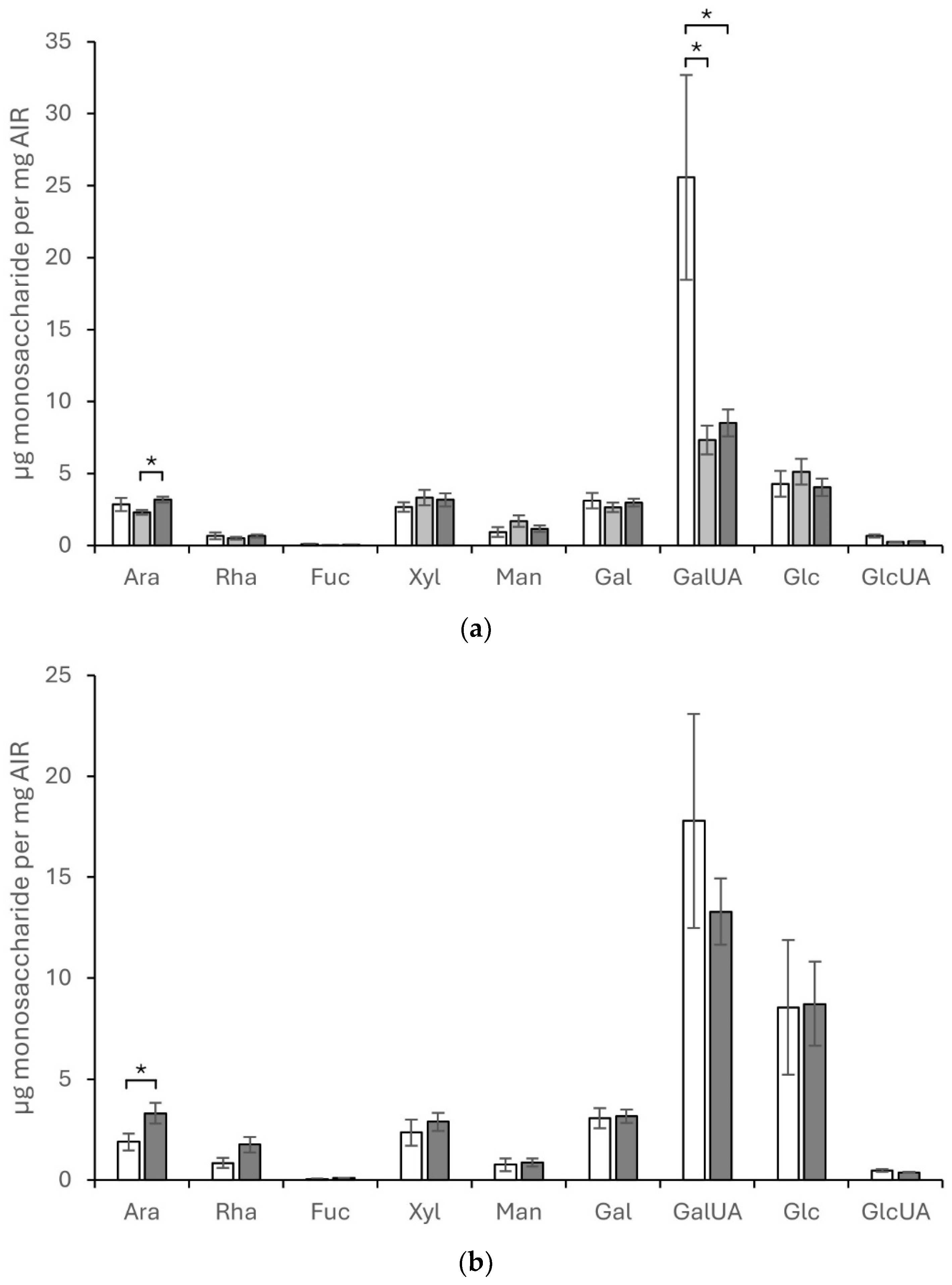

Total monosaccharide composition of cell wall fractions was analyzed for

C. plantagineum and

L. brevidens using alcohol-insoluble residue (AIR) isolated from hydrated with relative water content (RWC) ~ ca. 90%, partially hydrated with RWC ~ ca. 45% (in the case of

C. plantagineum), and desiccated leaf material with RWC ~ ca. 5% (

Figure 1). For

C. plantagineum, the main monosaccharides detected were GalUA, Glc, Xyl, Gal, and Ara, indicating that the cell wall is pectin-rich (

Figure 1a). Significant changes in main monosaccharides between hydration states were detected for Ara between the partially hydrated and desiccated states and for GalUA between the hydrated state and the partially hydrated and desiccated states. Ara concentrations increased from partially hydrated to the desiccated state. GalUA concentrations decreased considerably from the hydrated state to the partially hydrated and desiccated states. No significant differences in Glc, Xyl, and Gal were observed

For

L. brevidens, the main monosaccharides detected were also GalUA, Glc, Gal, Xyl, and Ara, indicating that the cell wall is also pectin-rich (

Figure 1b). Significant changes in main monosaccharides between hydration states were only detected for Ara, which increased concentration from the hydrated state to the dehydrated state. No significant differences in GalUA, Glc, Gal, and Xyl were detected. The ratios of the different monosaccharides present in the cell wall for

C. plantagineum and

L. brevidens were the same. Saccharification analysis of the AIR sourced from the different species (see supplementary datasets) was performed; however, no clear patterns were discernible.

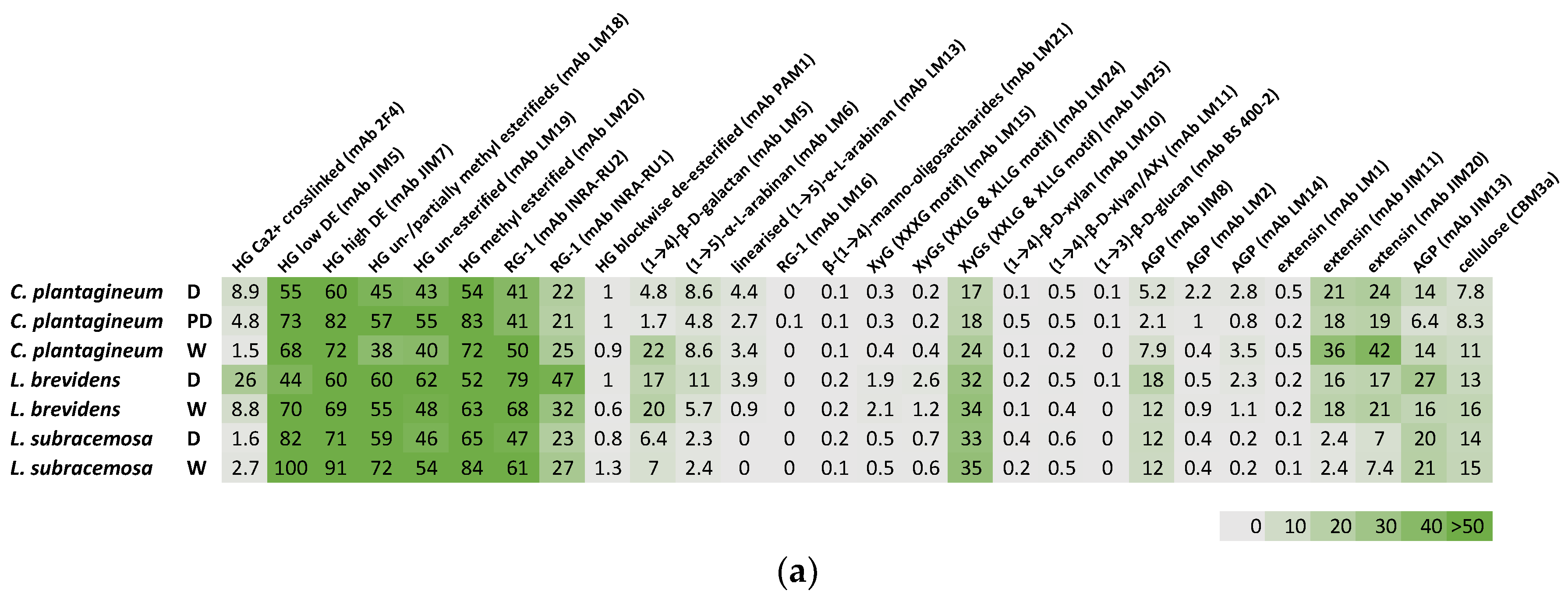

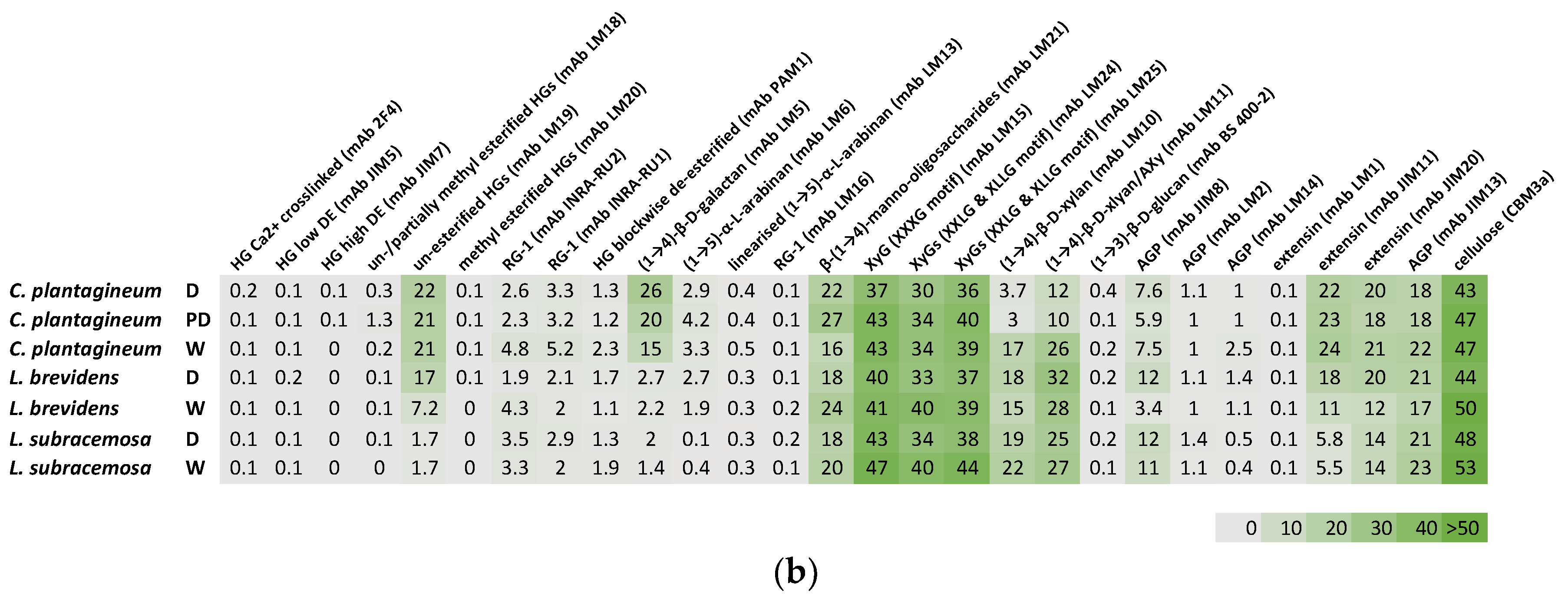

2.2. CoMPP Analysis of Cell Wall Material

Plant leaf cell wall fractions from CDTA-extractable material and NaOH-extractable material isolated from the three species at different hydration states were compared (

Figure 2). All three species,

C. plantagineum and

L. brevidens and the desiccation-sensitive

L. subracemosa, demonstrated a high abundance of homogalacturonan (HG), rhamnogalacturonan (RG-I) and cellulose epitopes. Moderate levels of xyloglucan (XyG) epitopes and epitopes for manno-oligosaccharides, xylan, extensin and arabinogalactan protein (AGP) were detected. Arabinan epitopes were detected at low levels, while the glucan epitope (mAb BS 400-2) was not present. A galactan epitope was present at moderate levels in

C. plantagineum and

L. brevidens but not in

L. subracemosa.

In C. plantagineum inspection of the datasets suggest the levels of HG epitopes varied upon desiccation. Calcium ion crosslinked HG levels (mAb 2F4) increased, and levels of partially unesterified and esterified HG (mAbs LM18 and LM19) were slightly elevated. In contrast, levels of high and low DE HG (mAbs JIM5 and JIM7) and esterified HG (mAb LM20) were decreased upon desiccation. Blockwise deesterified HG (mAb PAM1) was not detected. Levels of detectable RG-I epitopes (mAbs INRA-RU1 and INRA-RU2) decreased slightly in response to desiccation. Galactan (mAb LM5) was found to increase in level in the CDTA-extracted material and decrease in the NaOH-extracted material upon desiccation. Levels of arabinan (mAbs LM6 and LM13) remained fairly constant irrespective of hydration status. Levels of manno-oligosaccharides (mAb LM 21) were also slightly elevated in desiccated C. plantagineum. A small decrease was observed for xyloglucan (mAbs LM15, LM24 and LM25) and AGP (mAbs JIM8, LM2, LM14 and JIM13) between hydration states. In contrast, there was a decrease in levels of xylan (mAb LM10) and arabinoxylan (AX, mAb LM11) upon desiccation. A decrease in levels of extensin (mABs JIM11 and JIM 20) was detected in the CDTA-extracted material but not in the NaOH-extracted material. The levels of cellulose (mAbs CBM3a) decreased slightly in response to desiccation.

Similar changes in HG epitope level were observed for L. brevidens. In contrast, levels of detectable RG-1 epitopes (mAbs INRA-RU1 and INRA-RU2) were seen to increase in response to desiccation. No major change in galactan (mAb LM5) levels were observed. In contrast to C. plantagineum, in L. brevidens, the levels of arabinan (mAbs LM6 and LM13) were seen to increase slightly in response to desiccation, while manno-oligosaccharides (mAb LM 21) levels declined slightly. Similar to C. plantagineum, a small decrease was observed for xyloglucan (mAbs LM15, LM24 and LM25). Xylan (mAb LM10), arabinoxylan (AXy, mAb LM11) and AGP (mAbs JIM8, LM2, LM14 and JIM13) increased slightly upon desiccation in contrast to the change in levels seen in C. plantagineum. A decrease in levels of extensin (mABs JIM11 and JIM 20) was detected. The levels of cellulose (mAbs CBM3a) also decreased slightly in response to desiccation.

For the desiccation-sensitive L. subracemosa, changes in HG epitope levels were similar to those in the resurrection plants, except for the levels of partially unesterified and esterified HG (mAbs LM18 and LM19), which were found to decrease in response to desiccation. Levels of detectable RG-1 epitopes (mAbs INRA-RU1 and INRA-RU2) were seen to increase, similar to that observed for C. plantagineum. In contrast to the resurrection plants, L. subracemosa had lower levels of galactan (mAb LM5) and arabinan (mAbs LM6 and LM13) overall and these levels did not change in response to desiccation. Levels of manno-oligosaccharides (mAb LM 21) declined slightly with desiccation. Similar to the resurrection plants there was a small decrease in the levels of xyloglucan (mAbs LM15, LM24 and LM25). Xylan (mAb LM10) and arabinoxylan (AXy, mAb LM11) levels decreased slightly upon desiccation similar to C. plantagineum. Levels of extensin (mABs JIM11 and JIM 20) and AGP (mAbs JIM8, LM2, LM14 and JIM13) remained constant in contrast to the changes observed in the resurrection plants.

3. Discussion and Conclusions

The first detailed cell wall analysis of an angiosperm resurrection plant was reported by Vicré and colleagues on

Craterostigma wilmsii [

10,

11]. The initial study was a microscopy and immunocytochemical analyses [

10] followed by a biochemical analysis of the cell walls at different states of hydration or desiccation [

11] These studies implicated unesterified pectins and xyloglucan as well as substitutional changes in the hemicellulose fraction as factors important upon desiccation [

10,

11]. A later study on

Craterostigma plantagineum plants suggested that expansins may be upregulated upon desiccation and play a role in vegetative desiccation tolerance of resurrection plants [

12]. Moore et al. (2006) proposed RG-I linked arabinans and arabinogalactan proteins as ‘pectic plasticizers’ protecting the cell wall of the southern African resurrection plant species

Myrothamnus flabellifolia against mechanical stresses induced by complete dehydration [

13]. Moore et al. (2013) surveyed a range of southern African resurrection plant species using CoMPP technology [

14]. The study proposed potential cell wall strengthening mechanisms having evolved in parallel in angiosperm evolution i.e., considering that vegetative desiccation tolerance re-evolved as a genetic trait in different lineages during evolutionary time [

14,

15,

16]. A recent review of vegetative desiccation tolerance and resurrection plant cell wall changes proposed a glycine rich protein–wall associated kinase–arabinogalactan protein–FERONIA–pectin complex as crucial in releasing stored calcium ions during desiccation for release upon rehydration facilitating ‘resurrection’ in these remarkable species [

9,

16,

17] In summary, this study revealed that in all three species, no major changes in cell wall composition were detected using the profiling technologies employed. This is not to say there are no significant but more likely subtle changes occurring, which suggests that wholesale reorganisation of the cell wall in these plants is not a requirement for surviving desiccation. This would indicate that more efforts should be employed in the evaluation of wall-membrane signalling processes during dehydration to elucidate the mechanisms by which these factors contribute to vegetative desiccation tolerance in angiosperm resurrection plants.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

Lindernia brevidens and Linderna subracemosa were originally collected from the Taita Hills, Kenya and then propagated at the IMBIO lab of the University of Bonn (Germany). Four voucher specimens were deposited at Koblenz University (Germany). L. brevidens seeds were germinated directly in potting compost and maintained in climate chamber at day/night temperatures of 22 °C and 18 °C. Plants were grown under a 16 h day/8 h night regime at growth chambers in the IMBIO, University of Bonn (Germany). Craterostigma plantagineum plants were collected and grown as described previously [

18]. Plants were gradually dried in pots over a period of 12–21 days. Relative water content measurements were determined according to the method described previously [

14].

4.2. Isolation of Cell Wall Material

Lyophilised leaf material was ground to a fine powder under liquid nitrogen using a Retsch Mixer-Mill (Retsch, Haan, Germany). Powdered lyophilate was suspended in boiling 80 % (v/v) aqueous ethanol for 15 minutes to deactivate endogenous enzymes present. A series of organic solvent extractions were performed to remove low molecular weight metabolites from the cell wall containing residues. Residues were extracted for 2 h at room temperature twice with methanol-chloroform (1:1, v/v), twice with methanol-acetone (1:1, v/v), and finishing with acetone–water (4:1, v/v). The residues were then freeze-dried (Christ Lyophilizer, Martin Christ Gefriertrocknungsanlagen GmbH, Osterode am Harz, Germany). Solvent reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, Johannesburg, South Africa.

4.3. Saccharification Analysis

Saccharifcation efficiency was determined following the method described by Gómez and coauthors at the Centre for Novel Agricultural Products (CNAP) [

19]. Ground material was weighed into 96-well plates, each well contained 4 mg of each sample using a custom-made robotic platform (Labman Automation, Stokesley, North Yorkshire, UK). Pretreatment, enzymatic hydrolysis and sugar determination were performed automatically by a robotic platform (Tecan Evo 200; Tecan Group Ltd. Männedorf, Switzerland). The amount of released sugars was assessed against a glucose standard curve using the 3-methyl-2-benzothiazolinone hydrozone method (MTBH, Sigma-Aldrich, UK) [

20].

4.4. Monosaccharide Composition of Cell Walls

Cell wall monosaccharide analysis was performed as described previously [

21]. Cell walls were prepared by homogenizing plant materials in liquid phenol and washing with chloroform: methanol (2:1) before sedimentation by centrifugation. The pellets were washed twice with 95% ethanol and left to dry. To analyse the monosaccharide content of non-cellulosic polysaccharides, wall material was hydrolyzed with 2 M TFA for 4 h at 100 °C before separation by high-performance anion-exchange chromatography (HPAEC) on a CarboPac PA-20 column with pulsed amperometric detection. Separated monosaccharides were quantified by external calibration using an equimolar mixture of monosaccharide standards, which had also been treated with 2 M TFA in the same way.

4.5. CoMPP Analysis of Cell Wall Material

CoMPP (comprehensive microarray polymer profiling) involves the use of monoclonal antibodies and carbohydrate-binding modules to detect plant cell wall-specific epitopes as detailed previously [

22]. AIR was extracted sequentially using an aqueous 50 mM 1,2-cyclo-hexylene-dinitrilo-tetra-acetic acid (CDTA; Merck Darmstadt, Germany) solution followed by a 4 M aqueous NaOH solution (Merck Darmstadt, Germany). Each fraction is spotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane using an arrayjet printer (Marathon, Arrayjet, Edinburgh, United Kingdom). Individual microarrays were probed with a list of specific antibodies and other probes (see Supplementary Table 1 for probes used and references) and developed using buffered aqueous 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate and nitrotetrazolium blue solution (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Microarrays, after drying, are scanned using a flatbed scanner (Canon 8800, Søborg, Denmark) and then processed using array detection software (Array-Pro Analyzer v 6.3, MediaCybernetics, Rockville, Maryland, United States). The result is displayed as a heatmap using Excel software (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, United States).

4.6. Statistical and Univariate Tools

Statistical analyses were performed in consultation and collaboration with Professor Martin Kidd of the Centre for Statistical Consultation (Stellenbosch University). Descriptive statistical analyses and analysis of the variance (ANOVA) were performed with the statistical package of Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, United States) and Statistica (Statsoft, Southern African Analytics Pty Ltd., Johannesburg, South Africa) software.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website this paper posted on Preprints.org, Raw datasets: Supplementary Table 1, Moore et al. 2024 Plants monosacch. raw datasets.xlsx and Moore et al. 2024 Plants CoMPP raw datasets.xlsx

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P.M and D.B.; provision of plant material, D.B.; performing all experiments, J.P.M. and B.K.; writing—original draft preparation, all authors; writing—review and editing, all authors.; L.G. and B.K. saccharification and monosaccharide analysis; J.H. and B.J. CoMPP analysis; supervision, J.P.M.; funding acquisition, J.P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Royal Society (London, United Kingdom), Newton Mobility Grant 2018 Round 1 – NMG\R1\180336 to J.P.M. This research was partially funded by Stellenbosch University. The funders were not involved in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the paper; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Martin Kidd of the Centre of Statistical Consultation (Stellenbosch University) is thanked for assistance with statistical analyses. Valentino Giarola is thanked for helpful advice and assistance. The authors wish to dedicate this research article to the memory of the late Professor Simon McQueen-Mason.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Marks, R.A.; Pas, L.V.D.; Schuster, J.; Gilman, I.S.; VanBuren, R. Convergent Evolution of Desiccation Tolerance in Grasses 2024, 2023.11.29.569285.

- VanBuren, R.; Wai, C.M.; Giarola, V.; Župunski, M.; Pardo, J.; Kalinowski, M.; Grossmann, G.; Bartels, D. Core Cellular and Tissue-Specific Mechanisms Enable Desiccation Tolerance in Craterostigma. The Plant Journal 2023, 114, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djilianov, D.; Moyankova, D.; Mladenov, P.; Topouzova-Hristova, T.; Kostadinova, A.; Staneva, G.; Zasheva, D.; Berkov, S.; Simova-Stoilova, L. Resurrection Plants—A Valuable Source of Natural Bioactive Compounds: From Word-of-Mouth to Scientifically Proven Sustainable Use. Metabolites 2024, 14, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, J.R.; Fischer, E.; Baron, M.; Van Den Dries, N.; Facchinelli, F.; Kutzer, M.; Rahmanzadeh, R.; Remus, D.; Bartels, D. Lindernia Brevidens: A Novel Desiccation-Tolerant Vascular Plant, Endemic to Ancient Tropical Rainforests. The Plant Journal 2008, 54, 938–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, J.P.; Vicré, M.; Nguema-Ona, E.; Driouich, A.; Farrant, J.M. Drying Out Walls: How Do the Cell Walls of Resurrection Plants Survive Desiccation? In Plant Cell Walls; CRC Press, 2023 ISBN 978-1-00-317830-9.

- Ilias, I.A.; Wagiran, A.; Azizan, K.A.; Ismail, I.; Samad, A.F.A. Irreversibility of the Cell Wall Modification Acts as a Limiting Factor in Desiccation Tolerance of Oryza Sativa Ssp. Indica Cv MR303. Plant Stress 2024, 12, 100463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Legay, S.; Sergeant, K.; Zorzan, S.; Leclercq, C.C.; Charton, S.; Giarola, V.; Liu, X.; Challabathula, D.; Renaut, J.; et al. Molecular Insights into Plant Desiccation Tolerance: Transcriptomics, Proteomics and Targeted Metabolite Profiling in Craterostigma plantagineum. The Plant Journal 2021, 107, 377–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Jung, N.U.; Giarola, V.; Bartels, D. The Dynamic Responses of Cell Walls in Resurrection Plants During Dehydration and Rehydration. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, N.U.; Giarola, V.; Chen, P.; Knox, J.P.; Bartels, D. Craterostigma plantagineum Cell Wall Composition Is Remodelled during Desiccation and the Glycine-Rich Protein CpGRP1 Interacts with Pectins through Clustered Arginines. The Plant Journal 2019, 100, 661–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicré, M.; Sherwin, H.W.; Driouich, A.; Jaffer, M.A.; Farrant, J.M. Cell Wall Characteristics and Structure of Hydrated and Dry Leaves of the Resurrection Plant Craterostigma Wilmsii, a Microscopical Study. Journal of Plant Physiology 1999, 155, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicré, M.; Lerouxel, O.; Farrant, J.; Lerouge, P.; Driouich, A. Composition and Desiccation-Induced Alterations of the Cell Wall in the Resurrection Plant Craterostigma wilmsii. Physiol Plant 2004, 120, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, L.; McQueen-Mason, S. A Role for Expansins in Dehydration and Rehydration of the Resurrection Plant Craterostigma plantagineum. FEBS Lett 2004, 559, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, J.P.; Nguema-Ona, E.; Chevalier, L.; Lindsey, G.G.; Brandt, W.F.; Lerouge, P.; Farrant, J.M.; Driouich, A. Response of the Leaf Cell Wall to Desiccation in the Resurrection Plant Myrothamnus flabellifolius. Plant Physiol 2006, 141, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, J.P.; Nguema-Ona, E.E.; Vicré-Gibouin, M.; Sørensen, I.; Willats, W.G.T.; Driouich, A.; Farrant, J.M. Arabinose-Rich Polymers as an Evolutionary Strategy to Plasticize Resurrection Plant Cell Walls against Desiccation. Planta 2013, 237, 739–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, J.P.; Vicré-Gibouin, M.; Farrant, J.M.; Driouich, A. Adaptations of Higher Plant Cell Walls to Water Loss: Drought vs Desiccation. Physiol Plant 2008, 134, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dace, H.J.; Adetunji, A.E.; Moore, J.P.; Farrant, J.M.; Hilhorst, H.W. A Review of the Role of Metabolites in Vegetative Desiccation Tolerance of Angiosperms. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2023, 75, 102410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Giarola, V.; Bartels, D. The Craterostigma plantagineum Protein Kinase CpWAK1 Interacts with Pectin and Integrates Different Environmental Signals in the Cell Wall. Planta 2021, 253, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, D.; Schneider, K.; Terstappen, G.; Piatkowski, D.; Salamini, F. Molecular Cloning of Abscisic Acid-Modulated Genes Which Are Induced during Desiccation of the Resurrection Plant Craterostigma plantagineum. Planta 1990, 181, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, L.D.; Whitehead, C.; Barakate, A.; Halpin, C.; McQueen-Mason, S.J. Automated Saccharification Assay for Determination of Digestibility in Plant Materials. Biotechnology for Biofuels 2010, 3, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthon, G.E.; Barrett, D.M. Determination of Reducing Sugars with 3-Methyl-2-Benzothiazolinonehydrazone. Analytical Biochemistry 2002, 305, 287–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, L.; Milne, J.L.; Ashford, D.; McQueen-Mason, S.J. Cell Wall Arabinan Is Essential for Guard Cell Function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100, 11783–11788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kračun, S.K.; Fangel, J.U.; Rydahl, M.G.; Pedersen, H.L.; Vidal-Melgosa, S.; Willats, W.G.T. Carbohydrate Microarray Technology Applied to High-Throughput Mapping of Plant Cell Wall Glycans Using Comprehensive Microarray Polymer Profiling (CoMPP). In High-Throughput Glycomics and Glycoproteomics: Methods and Protocols; Lauc, G., Wuhrer, M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, 2017; pp. 147–165 ISBN 978-1-4939-6493-2.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).