1. Introduction

In tissue engineering, achieving precise and uniform cell seeding on scaffolds is crucial for the development of functional tissue constructs [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Conventional methods such as drop-wise seeding have limitations in accuracy and consistency, prompting the exploration of automated techniques using liquid handling systems [

5,

6]. These systems offer advantages in controlling droplet volume and spatial distribution, enhancing seeding precision over manual methods [

7,

8].

Previous studies have compared manual drop-wise seeding to alternative techniques, including seeding by adherence where scaffolds are placed in confluent cell cultures to allow cells to migrate upwards [

9,

10]. Other advanced methods involve perfusion seeding, where cells are circulated through scaffolds to improve distribution [

11,

12,

13]. Centrifugal force has also been utilized to enhance cell penetration into porous scaffolds [

14].

The architectural design of scaffolds significantly influences cell seeding efficiency and tissue formation [

15]. Factors such as pore size, interconnectivity, and surface characteristics dictate cell attachment, proliferation, and differentiation [

16,

17]. Optimization of seeding protocols considers these scaffold properties to maximize tissue integration and functionality [

18,

19,

20].

Emerging technologies in liquid handling robotics, like the OpenLH system, enable precise manipulation of biological fluids for various experimental setups [

21,

22,

23]. Such platforms support customizable protocols for seeding multiple cell types and dispensing growth factors, enhancing the scalability and reproducibility of tissue engineering processes [

24]. In addition computational methods to improve cell seeding on scaffolds were developed [

25,

26].

In this study, we introduce an innovative seeding method using the OpenLH system to seed cells on large scaffolds with high accuracy and reproducibility. By leveraging robotic automation, we aim to optimize cell distribution and enhance the efficiency of scaffold-based tissue engineering. The insights gained from this research could advance both biomedical research and applications in fields such as cultured meat production, where precise control over cell seeding is critical [

1,

2,

11,

14,

15,

17,

21,

24].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Robotic liquid dispensing platform

We used the OpenLH system as described [

21]. The system utilizes 200 micorliter filter tips, can remove tips and pick up a new tip from a tip box. The system is programmable in python or by block interface or directly by printing a picture (as described in [

21]. For seeding scaffolds we used a 3 new protocols that were coded in python. The systems dimensions afforded the introduction of the whole system into a basic laminar flow hood, the system was washed with ethanol and UV radiated in the laminar flow hood for 1 hour before introducing cells and scaffolds.

2.2. Robotic Liquid Dispensing Protocols

To visualize the deposition locations of droplets on the scaffold boundary, we used the OpenLH system programmed with specific protocols to dispense droplets at designated points. For the deposition of a single droplet, the OpenLH system was programmed to deposit one droplet on the scaffold boundary, with the location represented by a blue square and the Eppendorf tube position indicated by a blue dot. To test multiple droplets, the system was configured to dispense four droplets at specified points, visualized using the plot_points() program, ensuring even distribution across the scaffold. For nine droplets, the system was similarly programmed and visualized. We also validated the system’s precision by depositing nine points using double-distilled water (DDW) on an empty Petri dish as a control. The deposition paths for four and nine droplets were visualized using the plot_sorted() program, which printed the sequence and spatial distribution of the droplets, demonstrating the OpenLH system’s path planning and execution accuracy. The actual robot operation was conducted using the print_points() program. print_points() indludes a step of pippeting up and down the cells in the Eppendorf before proceeding to deposit the cell solution on the scaffold. The OpenLH system was operated under sterile conditions within a laminar flow hood, sanitized with ethanol, and UV radiated for one hour prior to use. Specific Python scripts controlled the system, including commands for picking up tips, aspirating the cell solution, and dispensing droplets at designated coordinates. These steps ensured precise control over the droplet deposition process, enabling detailed analysis and optimization of cell seeding protocols on scaffolds.

To run the experiments, we used the OpenLH robotic system to deposit varying numbers of liquid droplets onto a predefined area. Three experiments were performed three times on nine different scaffolds, guided by inputs for grid dimensions (1x1, 2x2, and 3x3), extrusion speed (5000 mm/min), pipette volume (60 units), dispensing height (30.5 mm), boundary coordinates (a=(207, 40), b=(220, 40), c=(220, 51), d=(207, 51)), and point-to-point distance (3 mm). The initial experiment involved depositing a single droplet in a 1x1 grid configuration with specific parameters, followed by scaling up to deposit four droplets in a 2x2 grid with a 3 mm distance between adjacent droplets. Subsequently, nine droplets were deposited in a 3x3 grid with the same 3 mm distance between adjacent droplets. The deposition volumes in units for 1, 4, and 9 points in the respective 1x1, 2x2, and 3x3 grid configurations are 60 units, 15 units, and 6.67 units, making the total volume distributed across each grid to 86 microliters. The OpenLH is linear above 1.5 microliter [

21].

2.3. Scaffolds

Scaffolds were prepared as in [

27]. Briefly, fresh Aloe vera (Aloe barbadensis Miller) leaves were obtained from a local farm (Just Aloe, Ein Yahav, Israel). Aloe vera parenchyma tissue was separated from the rind using a knife, then the tissue was autoclaved for 30 minutes in glass jars, the gel was removed with a vacuum pump in a laminar flow hood and the remaining parenchymal cellulose was placed in a lidded 15 cm petri plate to maintain sterility, the plate was then stored for 30 minutes at -80 Celsius. When it was completely frozen the plate was put in a freeze dryer (Biobase, BK-FD102) for 48 hours until the plate was not cold indicating complete dehydration. The lyophilized tissue was then placed in a laminar flow hood under UV for 30 minutes. Following UV sterilization. The scaffolds were cut to fit 6 well Corning Costar Multiple Well Plates. Scaffolds were incubated for 24 hours in DMEM low glucose media. The media was removed and the scaffolds were left in a laminar flow hood in open 6 well plates for 1 hour before seeding with the OpenLH system.

2.4. Cells and Media

Bovine mesenchymal stem cells (bMSCs), were isolated, cultured, and characterized as described in [

28], the cells were immortalized and engineered to express GFP. All cells were plated in a low-glucose Dulbecco modified eagle medium (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, United States) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 1% L-glutamine and a penicillin–streptomycin mixture (1%). Cells were trypsinized, counted and % live cells was determined using trypan blue and a cell counter (TC20 automated cell counter, Bio-Rad). The cell concentration was 3M cells per ml, 1ml was transferred to a sterile 1.5 ml Eppendorf tube and was placed in the OpenLH system at the location defined by the user.

2.5. Metabolic Activity Assay

The scaffolds were transferred to a new 6-well plate and then incubated for 4 hours in a solution containing 2 ml of growth medium mixed with Alamar Blue reagent stock solution at a 10:1 ratio, with the reagent concentration being 3.6% Alamar Blue (Thermo Scientific, 88951) in PBS. After the 4-hour incubation period, 100 µl of the medium from each well was transferred to a clear 96-well plate. Fluorescence readings were obtained using a BioTek Synergy HT Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (Agilent Technologies, Inc.), measuring fluorescence at 590 nm following excitation at 520 nm. Subsequently, the medium in each well was replaced with 2 ml of fresh medium. To normalize the results, fluorescence readings were divided by the fluorescent reading obtained from a scaffold incubated in medium without cells.

2.6. Microscopy

Fluorescence imaging was performed using an Inverted Nikon ECLIPSE TI-DH fluorescent microscope.

3. Results

3.1. Operation and Testing

By running the program

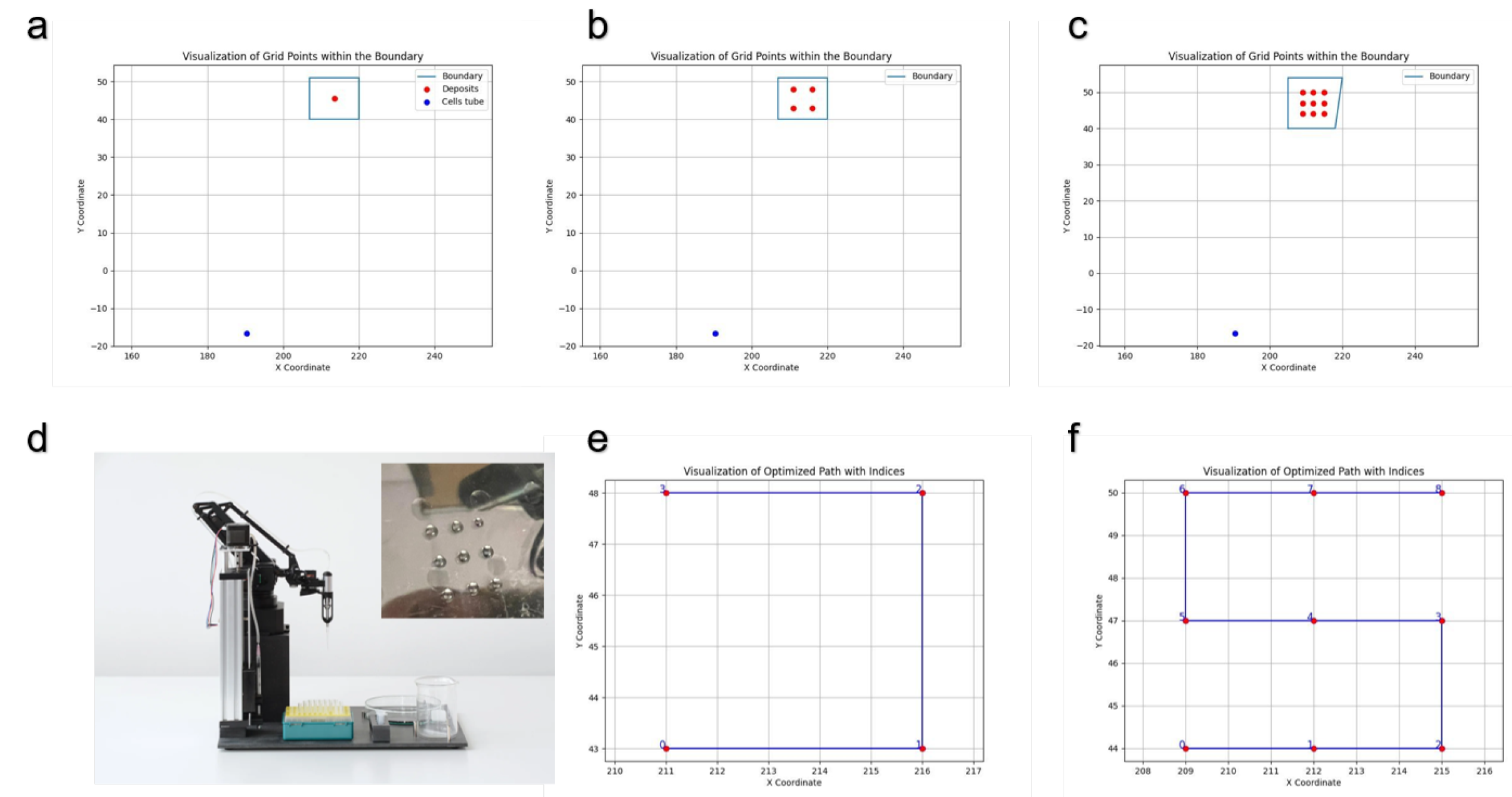

plot_points(), we can visualize the deposition locations of the droplets over the scaffold boundary as defined by the user. The blue dot represents the location of the Eppendorf containing the solution deposited (

Figure 1a-c). We tested the deposition for nine points using the OpenLH with DDW on an empty Petri dish (

Figure 1d). Additionally, running the program

plot_sorted() will display the deposition path of the OpenLH for 4 drops (

Figure 1e) and for 9 drops (

Figure 1f).

3.2. Visual Inspection of Scaffolds and Robotic Operation Before, During, and After Cell Seeding

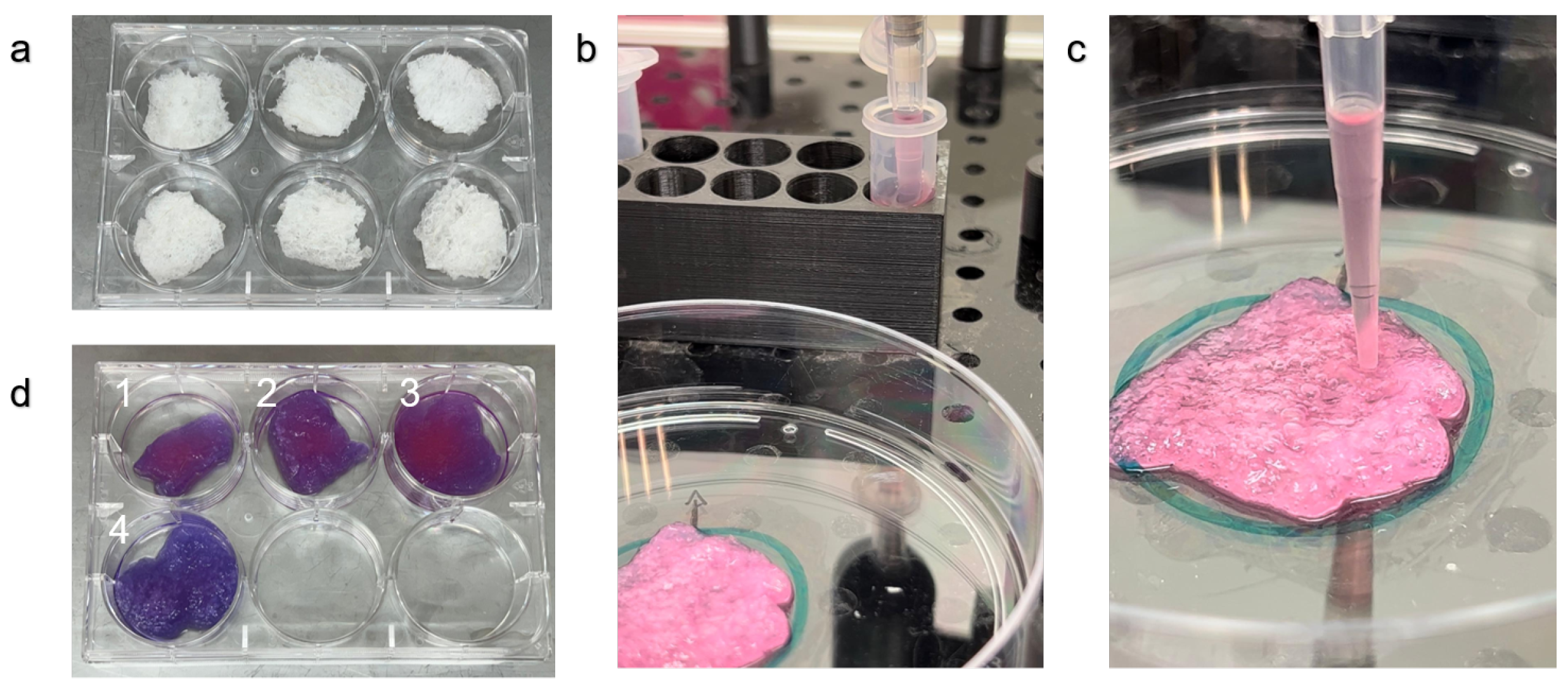

The AVPC scaffolds (

Figure 2a) were submerged in DMEM as described. The OpenLH pipetted up and down the liquid in the tube (

Figure 2b), then performed the droplet deposition on the scaffolds according to the user’s definitions. After the Alamar Blue assay, there is a visible difference between the scaffolds that were seeded (

Figure 2d(1-3)) and the negative control that was not seeded with cells (

Figure 2d(4)).

3.3. Metabolic Assay and Microscopy

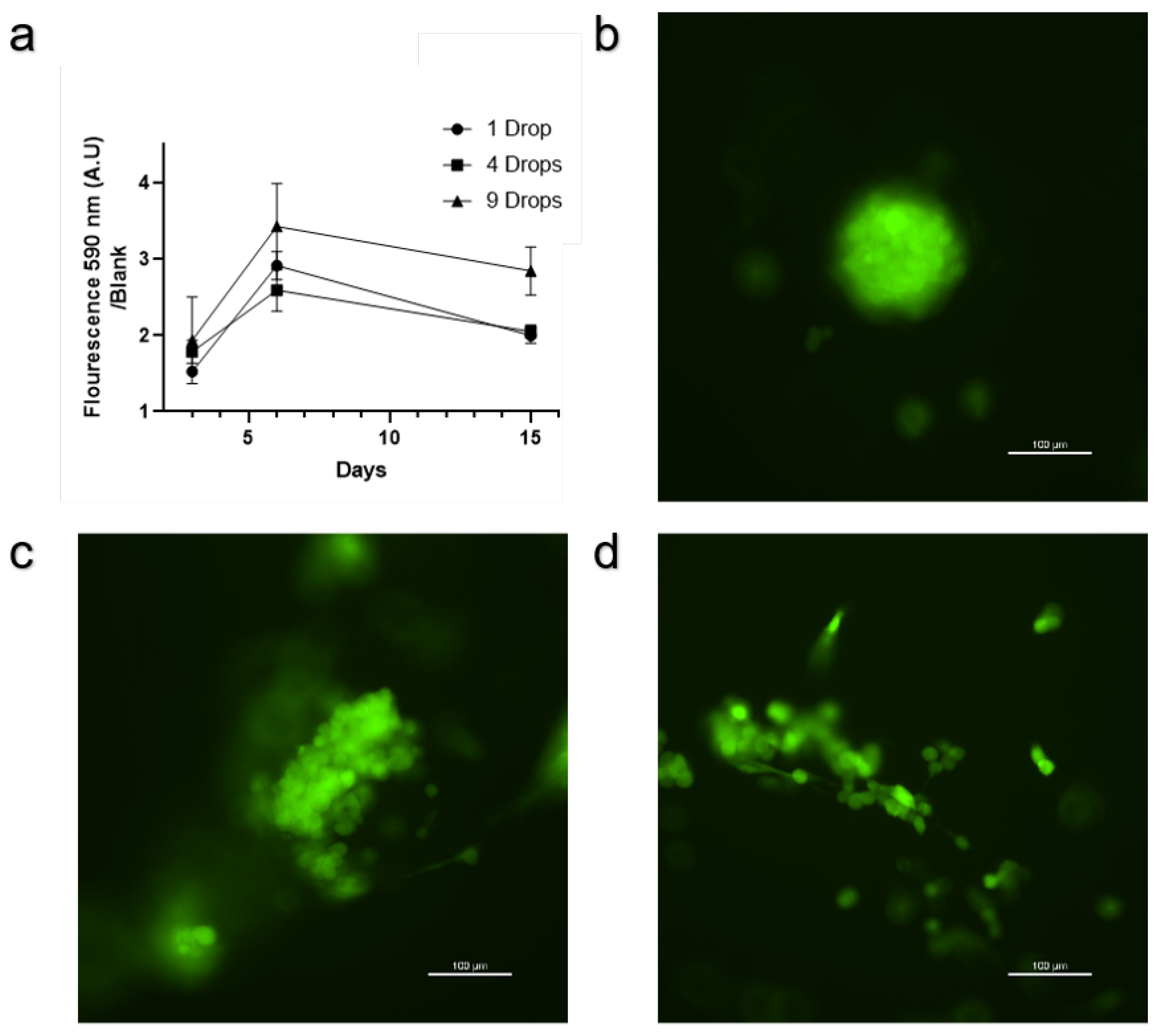

The results from the Alamar Blue assay show a clear visual difference observable to the naked eye between scaffolds with and without cells (

Figure 2d). In addition, the fluorescent reading from the Alamar Blue assay conducted on the scaffolds shows that seeding the same number of cells or the same total volume from the tube containing 3M cells/ml in 9 points leads to more overall metabolic activity on the scaffold than seeding 1 or 4 drops (

Figure 3a). Fluorescent microscopy of the cells on the scaffold shows three distinct phenotypes: round aggregates (

Figure 3b), cell clusters along scaffold fibers (

Figure 3c), and single cells along scaffold fibers (

Figure 3d).

4. Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate the utilization of the OpenLH system in achieving precise and uniform cell seeding on scaffolds. Our experiments showed that automated seeding of multiple droplets on a scaffold can improve cell distribution and overall metabolic activity compared to seeding one droplet, equivalent to manual seeding, addressing the inherent limitations in accuracy and consistency found in conventional drop-wise seeding techniques. Other seeding methods that were described in the introduction including seeding by adherence under static conditions as described in [

27] may be effective and useful in different use cases in research and in industrial use.

The visualization of droplet deposition locations over the scaffold (Fig.

Figure 1a-c) allows the user to design the experiment that will be preformed by the OpenLH. The ability to program and execute specific deposition patterns ensures that the cells are evenly distributed across the scaffold, which is crucial for efficient cell seeding. Testing the deposition for nine points (

Figure 1d) demonstrate a simple test for the user to conduct before using cells and scaffolds, both valuable resources not to be wasted. The comparison of deposition paths for different numbers of droplets (

Figure 1e-f) further verifies the system’s procedure to be conducted, the current code can support larger and more complicated designs including multi material deposition and printing from picture as described in [

21]. In addition, the user may wish to use more than one cell type or to seed the scaffold in different cultivation times with cells and growth factors in a way that their location or the time of adding them will impact the tissue growing on the scaffold.

The subsequent metabolic activity assays (

Figure 3a) confirm that a higher number of seeding points enhances overall cell metabolic activity on the scaffold. This suggests that increasing the number of deposition points allows for more even cell distribution, likely leading to better cell survival and proliferation. The Alamar Blue assay results indicate that scaffolds seeded with nine droplets exhibit higher metabolic activity compared to those seeded with fewer droplets. This finding is crucial, as it suggests that optimized seeding can lead to more robust tissue formation. Fluorescence microscopy further revealed three distinct cell phenotypes on the scaffold: round aggregates (

Figure 3b), cell clusters along scaffold fibers (

Figure 3c), and single cells adhered to the scaffold fibers (

Figure 3d). It is possible that further calibrating the seeding density the deposition pattern, deposition volume and distance between the droplets can allow users to achieve a more homogeneous phenotype on the scaffold. The scaffold we use is anisotropic and potentially isotropic scaffolds will provide better results [

29].

The OpenLH system’s ability to operate within a laminar flow hood (

Figure 2b) ensures that the entire seeding process can be conducted under sterile conditions, minimizing the risk of contamination. This advantage is significant in tissue engineering, where maintaining a sterile environment is paramount for cell viability and experimental reproducibility. Various other liquid handling platforms, discussed in the literature, may or may not fit in a laminar flow hood, in this case sterility should be maintained by other means [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. In addition, although commercial bioprinters and liquid handlers are not specifically designed for cell seeding on scaffolds, they can potentially address this challenge while maintaining sterility [

36,

37].

Open-source code for liquid handlers may support more scientific experimentation by enabling customization of protocols, providing accessibility to non-programmers, and enhancing transparency that fosters reproducibility across multiple locations globally ([

38,

39,

40]). Our code is available on github [

41] and build instructions for the system are available on instructables [

42]. The current setup affords a working range of 50mm - 320mm [

43], however it can be extended further using a slide rail [

44].

Robotic seeding of droplets, demonstrated by OpenLH, represents a promising method for conducting tissue cultivation on large 3D scaffolds, particularly in addressing challenges such as neovascularization in tissue engineering [

24], by optimizing seeding deposition and parameters we discuss such as distance between droplets and droplet volume and grid shape and size. The evaluation for efficient seeding can be done in small scale by microscopy and histology however for large scaffolds it may be more useful to use methods such as multi-focal wide-field fluorescence microscopy or to consider immunolabeling and clearing to get the whole picture [

45,

46,

47].

Beyond simply seeding cells, OpenLH can also effectively deposit growth factors before or during tissue cultivation. This capability allows for precise deposition of both cells and growth factors at various stages of tissue development, potentially enhancing proliferation, differentiation, and promoting angiogenesis under optimal conditions. Coupled with precise perfusion, this approach facilitates the targeted delivery of essential nutrients to tissues, thereby mitigating the risk of cell necrosis. By leveraging robotic technologies for controlled seeding, researchers can significantly enhance the functionality and viability of engineered tissues [

48]. Coupled with real-time measurements of tissue formation on the scaffold over time [

49,

50], it becomes feasible to establish feedback loops that guide the OpenLH or other robotic systems to perform temporospatial actions such as adding cells or growth factors aimed at enhancing tissue formation.

5. Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate that the OpenLH robotic liquid handling system offers a reliable and precise method for cell seeding on scaffolds, enhancing cell distribution and metabolic activity. This automated approach addresses the limitations of manual seeding techniques, providing a scalable and reproducible solution for tissue engineering applications. The improved cell seeding uniformity and higher metabolic activity observed with the OpenLH system could translate into better tissue construct quality, advancing both biomedical research and applications, especially when working with large scaffolds, such as cultured meat production. The OpenLH system’s code is open source and available on github [

41], allowing users to customize, utilize and enhance it for conducting their own experiments, thereby enhancing the versatility and applicability of this technology in tissue engineering and related fields.

6. Patents

The OpenLH system is open-sourced on Github and Instructables all code and fabrication methods are available [

41,

42].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.G. and O.S.; methodology, G.G.; software, J.W.; validation, G.G.; formal analysis, G.G.; investigation, G.G.; resources, G.G.; writing—original draft preparation, G.G.; writing—review and editing, G.G and O.S.; visualization, G.G.; supervision, O.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Israeli MINISTRY OF INNOVATION, SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, Levi Eshkol Scholarship, grant number 3031000233 and partially supported by the Israeli Innovation Authority through the cultivated meat consortium (file number 82446).

Data Availability Statement

The original code for this work is available on github [

41].

Acknowledgments

The OpenLH system was designed and built by Adnrey Grishko at the media innovation lab (milab) at Reichman University led by prof’ Oren Zuckerman.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OpenLH |

Open Source Liquid Handler |

References

- Maidhof, R.; Marsano, A.; Lee, E.J.; Vunjak-Novakovic, G. Perfusion seeding of channeled elastomeric scaffolds with myocytes and endothelial cells for cardiac tissue engineering. Biotechnology progress 2010, 26, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burg, K.; Holder, W., Jr.; Culberson, C.; Beiler, R.; Greene, K.; Loebsack, A.; Roland, W.; Eiselt, P.; Mooney, D.; Halberstadt, C. Comparative study of seeding methods for three-dimensional polymeric scaffolds. Journal of biomedical materials research 2000, 51, 642–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cámara-Torres, M.; Sinha, R.; Mota, C.; Moroni, L. Improving cell distribution on 3D additive manufactured scaffolds through engineered seeding media density and viscosity. Acta Biomaterialia 2020, 101, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaudez, F.; Ivanovski, S.; Ipe, D.; Vaquette, C. A comprehensive comparison of cell seeding methods using highly porous melt electrowriting scaffolds. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2020, 117, 111282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faina, A.; Nejati, B.; Stoy, K. Evobot: An open-source, modular, liquid handling robot for scientific experiments. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.; Lam, A.T.; Fuhrmann, T.; Erikson, L.; Wirth, M.; Miller, M.L.; Blikstein, P.; Riedel-Kruse, I.H. DIY liquid handling robots for integrated STEM education and life science research. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0275688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, L.C.; Calasanz-Kaiser, A.; Hyman, L.; Voitiuk, K.; Patil, U.; Riedel-Kruse, I.H. Liquid-handling Lego robots and experiments for STEM education and research. PLoS biology 2017, 15, e2001413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehesz, A.N.; Brown, J.; Hajdu, Z.; Beaver, W.; Da Silva, J.; Visconti, R.; Markwald, R.; Mironov, V. Scalable robotic biofabrication of tissue spheroids. Biofabrication 2011, 3, 025002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.J.; Jeong, I.; Noh, K.T.; Yu, H.S.; Lee, G.S.; Kim, H.W. Robotic dispensing of composite scaffolds and in vitro responses of bone marrow stromal cells. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine 2009, 20, 1955–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, L.; Feng, W.; Hutmacher, D.W.; San Wong, Y.; Tong Loh, H.; Fuh, J.Y. Direct writing of chitosan scaffolds using a robotic system. Rapid Prototyping Journal 2005, 11, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, D.; Marsano, A.; Jakob, M.; Heberer, M.; Martin, I. Oscillating perfusion of cell suspensions through three-dimensional scaffolds enhances cell seeding efficiency and uniformity. Biotechnology and bioengineering 2003, 84, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vunjak-Novakovic, G.; Obradovic, B.; Martin, I.; Bursac, P.M.; Langer, R.; Freed, L.E. Dynamic cell seeding of polymer scaffolds for cartilage tissue engineering. Biotechnology progress 1998, 14, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, N.; Fechner, C.; Voges, A.; Ott, R.; Stenzel, J.; Siewert, S.; Bergner, C.; Khaimov, V.; Liese, J.; Schmitz, K.P.; others. An optimized 3D-printed perfusion bioreactor for homogeneous cell seeding in bone substitute scaffolds for future chairside applications. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 22228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godbey, W.; Hindy, B.S.; Sherman, M.E.; Atala, A. A novel use of centrifugal force for cell seeding into porous scaffolds. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 2799–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melchels, F.P.; Barradas, A.M.; Van Blitterswijk, C.A.; De Boer, J.; Feijen, J.; Grijpma, D.W. Effects of the architecture of tissue engineering scaffolds on cell seeding and culturing. Acta biomaterialia 2010, 6, 4208–4217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holy, C.E.; Shoichet, M.S.; Davies, J.E. Engineering three-dimensional bone tissue in vitro using biodegradable scaffolds: Investigating initial cell-seeding density and culture period. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research: An Official Journal of The Society for Biomaterials, The Japanese Society for Biomaterials, and The Australian Society for Biomaterials and the Korean Society for Biomaterials 2000, 51, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, T.; Miwa, M.; Sakai, Y.; Niikura, T.; Lee, S.; Oe, K.; Iwakura, T.; Kurosaka, M.; Komori, T. Efficient cell-seeding into scaffolds improves bone formation. Journal of dental research 2010, 89, 854–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dettinger, P.; Kull, T.; Arekatla, G.; others. Open-source personal pipetting robots with live-cell incubation and microscopy compatibility. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, W.; Bowman, R.W.; Wang, H.; Bumke, K.E.; Collins, J.T.; Spjuth, O.; Carreras-Puigvert, J.; Diederich, B. An Open-Source Modular Framework for Automated Pipetting and Imaging Applications. Advanced biology 2022, 6, 2101063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nycz, C.J.; Strobel, H.A.; Suqui, K.; Grosha, J.; Fischer, G.S.; Rolle, M.W. A method for high-throughput robotic assembly of three-dimensional vascular tissue. Tissue Engineering Part A 2019, 25, 1251–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gome, G.; Waksberg, J.; Grishko, A.; Wald, I.Y.; Zuckerman, O. OpenLH: Open liquid-handling system for creative experimentation with biology. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction; 2019; pp. 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hoque, M.E. Robust formulation for the design of tissue engineering scaffolds: A comprehensive study on structural anisotropy, viscoelasticity and degradation of 3D scaffolds fabricated with customized desktop robot based rapid prototyping (DRBRP) system. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2017, 72, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Ahn, S.; Chun, W.; Kim, G. Enhancement of cell viability by fabrication of macroscopic 3D hydrogel scaffolds using an innovative cell-dispensing technique supplemented by preosteoblast-laden micro-beads. Carbohydrate polymers 2014, 104, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shokrani, H.; Shokrani, A.; Sajadi, S.M.; Seidi, F.; Mashhadzadeh, A.H.; Rabiee, N.; Saeb, M.R.; Aminabhavi, T.; Webster, T.J. Cell-seeded biomaterial scaffolds: the urgent need for unanswered accelerated angiogenesis. International journal of nanomedicine 2022, 1035–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Bloemen, V.; Impens, S.; Moesen, M.; Luyten, F.P.; Schrooten, J. Characterization and optimization of cell seeding in scaffolds by factorial design: quality by design approach for skeletal tissue engineering. Tissue Engineering Part C: Methods 2011, 17, 1211–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Tamaddon, M.; Gu, Y.; Yu, J.; Xu, N.; Gang, F.; Sun, X.; Liu, C. Cell seeding process experiment and simulation on three-dimensional polyhedron and cross-link design scaffolds. Frontiers in bioengineering and biotechnology 2020, 8, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- et al., G. Cultivation of Bovine Lipid Chunks on Aloe vera Scaffolds 2024. PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square.

- Gome, G.; Chak, B.; Tawil, S.; Shpatz, D.; Giron, J.; Brajzblat, I.; Shoseyov, O. Cultivation of Bovine Mesenchymal Stem Cells on Plant-Based Scaffolds in a Macrofluidic Single-Use Bioreactor for Cultured Meat. Foods 2024, 13, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonndorf, R.; Aibibu, D.; Cherif, C. Isotropic and anisotropic scaffolds for tissue engineering: Collagen, conventional, and textile fabrication technologies and properties. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 9561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobers, J.; Skopic, M.K.; Dinter, R.; Sakthithasan, P.; Neukirch, L.; Gramse, C.; Weberskirch, R.; Brunschweiger, A.; Kockmann, N. Design of an automated reagent-dispensing system for reaction screening and validation with DNA-tagged substrates. ACS Combinatorial Science 2020, 22, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keesey, R.; LeSuer, R.; Schrier, J. Sidekick: a low-cost open-source 3D-printed liquid dispensing robot. HardwareX 2022, 12, e00319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopyl, A.; Yew, Y.; Ong, J.W.; Hiscox, T.; Young, C.; Muradoglu, M.; Ng, T.W. Automated Liquid Handler from a 3D Printer, 2024.

- Florian, D.C.; Odziomek, M.; Ock, C.L.; Chen, H.; Guelcher, S.A. Principles of computer-controlled linear motion applied to an open-source affordable liquid handler for automated micropipetting. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 13663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, K.C.; Kharma, N.; Jaunky, B.B.; Nie, K.; Aguiar-Tawil, G.; Berry, D. Bioclonebot: A Versatile, Low-Cost, and Open-Source Automated Liquid Handler. Nawwaf and Jaunky, Brandon B. and Nie, Kaiyu and Aguiar-Tawil, Gabriel and Berry, Daniel, Bioclonebot: A Versatile, Low-Cost, and Open-Source Automated Liquid Handler.

- Yao, L.; Ou, J.; Wang, G.; Cheng, C.Y.; Wang, W.; Steiner, H.; Ishii, H. bioPrint: A Liquid Deposition Printing System for Natural Actuators. 2015.

- Denning, C.; Borgdorff, V.; Crutchley, J.; Firth, K.S.; George, V.; Kalra, S.; Kondrashov, A.; Hoang, M.D.; Mosqueira, D.; Patel, A.; Prodanov, L.; Rajamohan, D.; Skarnes, W.C.; Smith, J.G.; Young, L.E. Cardiomyocytes from human pluripotent stem cells: From laboratory curiosity to industrial biomedical platform. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 2016, 1863, 1728–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CELLINK: 3D Bioprinting, Bioprinters, Bioinks, and Live Cell Imaging. Available online: https://www.cellink.com/ (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Sun, J.; Patil, A.; Li, Y.; Guo, J.L.; Zhou, S. How to Sustain a Scientific Open-Source Software Ecosystem: Learning from the Astropy Project. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.15081 2024. arXiv:2402.15081 2024.

- McKiernan, E.C.; Bourne, P.E.; Brown, C.T.; Buck, S.; Kenall, A.; Lin, J.; McDougall, D.; Nosek, B.A.; Ram, K.; Soderberg, C.K.; Spies, J.R.; Thaney, K.; Updegrove, A.; Woo, K.H.; Yarkoni, T. Point of View: How open science helps researchers succeed. eLife 2016, 5, e16800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter-Zinck, H.; de Siqueira, A.F.; Vásquez, V.N.; Barnes, R.; Martinez, C.C. Ten simple rules on writing clean and reliable open-source scientific software. PLOS Computational Biology 2021, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MiLab, I. OpenLH: Open Liquid Handling System. Available online: https://github.com/idc-milab/openlh (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Instructables. OpenLH. Available online: https://www.instructables.com/OpenLH/ (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- UFactory. uArm Swift Specifications, 2017. Accessed: 2024-06-20.

- Slide Rail Project Bundle - Includes uArm Swift Pro. 2024. Available online: https://coolcomponents.co.uk/products/slide-rail-project-bundle (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Xie, H.; Han, X.; Xiao, G.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Li, Q.; He, J.; Zhu, D.; Yu, X.; others, *!!! REPLACE !!!*. Multifocal fluorescence video-rate imaging of centimetre-wide arbitrarily shaped brain surfaces at micrometric resolution. Nature Biomedical Engineering.

- Zhou, Q.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.H.; El Amki, M.; Glück, C.; Droux, J.; Reiss, M.; Weber, B.; Wegener, S.; Razansky, D. Three-dimensional wide-field fluorescence microscopy for transcranial mapping of cortical microcirculation. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 7969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, R.; Kolabas, Z.I.; Pan, C.; Mai, H.; Zhao, S.; Kaltenecker, D.; Voigt, F.F.; Molbay, M.; Ohn, T.l.; Vincke, C.; others. Whole-mouse clearing and imaging at the cellular level with vDISCO. Nature Protocols 2023, 18, 1197–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, C.; Dai, C.; Shi, Q.; Fang, G.; Xie, D.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Y.J.; Wang, C.C.; Wang, X.J. A multi-axis robot-based bioprinting system supporting natural cell function preservation and cardiac tissue fabrication. Bioactive materials 2022, 18, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shohan, S.; Harm, J.; Hasan, M.; Starly, B.; Shirwaiker, R. Non-destructive quality monitoring of 3D printed tissue scaffolds via dielectric impedance spectroscopy and supervised machine learning. Procedia Manufacturing 2021, 53, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Liang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Liu, H.; Ji, J.; Fan, Y. A resazurin-based, nondestructive assay for monitoring cell proliferation during a scaffold-based 3D culture process. Regenerative biomaterials 2020, 7, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).