1. Introduction

Incorporating natural materials, such as plant-based food-grade scaffolds, into bioreactor design aligns with sustainable practices to use renewable animal-free materials, though cost implications remain a challenge [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Current research, influenced by seminal works such as [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11], emphasizes the potential of minimally processed plant-based food-grade scaffolds and the need for cost-effective and innovative solutions for bio-processing such as single-use bioreactors [

12,

13,

14]. Puffed rice has a highly porous and airy structure due to the expansion of the rice grains during the puffing process. This porosity can provide a three-dimensional environment for cell adherence, proliferation, and nutrient exchange [

14,

15]. The gelatinization of starches during the production process can render the surface of Puffed rice hydrophilic and its nutritional composition changes [

16,

17,

18]. This property is beneficial for promoting cell adhesion and spreading, as many cells prefer a hydrophilic environment [

19,

20,

21,

22]. Puffed rice can be broken down or processed into various sizes and shapes allowing the scaffold to be customized according to the specific requirements of the bioprocess. The food industry is interested in "clean lables", scaffolds such as puffed rice can be manufactured without additives or harmful substances, thus may provide a clean and inert substrate suitable for for cell culture, fit within the regulatory framework of the food industry and be in line with consumer perception [

23]. Puffed rice is a relatively inexpensive, it is produced globally in tons at a cost of 0.69 - 0.86 USD/kg [

24,

25]. Reliable and cost-effective methods to create tailor-made bioreactor systems are vital for advancing biotechnology, for proliferating cells in suspension and cultivating cells on scaffolds. In addition there is a great need for versatility and the ability to culture cells on unconventional scaffolds [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. This is the case for existing industries such as pharma but also for the emerging cultured meat industry [

31,

41]. However, the high construction cost of bioreactors hinders scalability[

5,

6,

42], and few commercially available large-scale bioreactors support cell cultivation on food-grade scaffolds [

26,

31].

In this study, we evaluated the use of laser welding to incorporate nylon bilayers, the main component of the macrofluidic single-use bioreactor (MSUB) construction. Our primary goal is to demonstrate compatibility with cell culture and utility as a rapid prototyping method for large-scale fluidics, similar to microfoudics only at a large scale [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48]. Significantly, we demonstrate that cells can proliferate and potentially differentiate on scaffolds within macrofluidic systems. Using our approach, we demonstrate a decrease in overall bioreactor prototyping and construction costs and potentially answer the need for scalable bioreactor solutions for research and industry [

49,

50,

51]. This study addresses this gap by leveraging laser welding to integrate nylon bilayers, potentially enabling affordable single-use bioreactors for laboratory-scale and industrial use[

52,

53,

54,

55,

56]. Converging affordable single-use bioreactors with minimal shear forces and maximizing cell adherence by adding macro carriers such as puffed rice may increase biomass production in a scaled-out model [

26]. In summary, our research showcases the potential of laser fabrication of plastic films into macrofluidics, a novel single-use bioreactor fabrication method. This advancement aims to bridge the gap in bioprocessing infrastructure and foster sustainable growth and innovation in cell cultivation for diverse biotechnological applications and uniquely fitting for cultured meat.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fabrication of Macrofluidic Devices

2.1.1. Laser Fabrication of Macrofluidic Devices from Thermoplastic Film

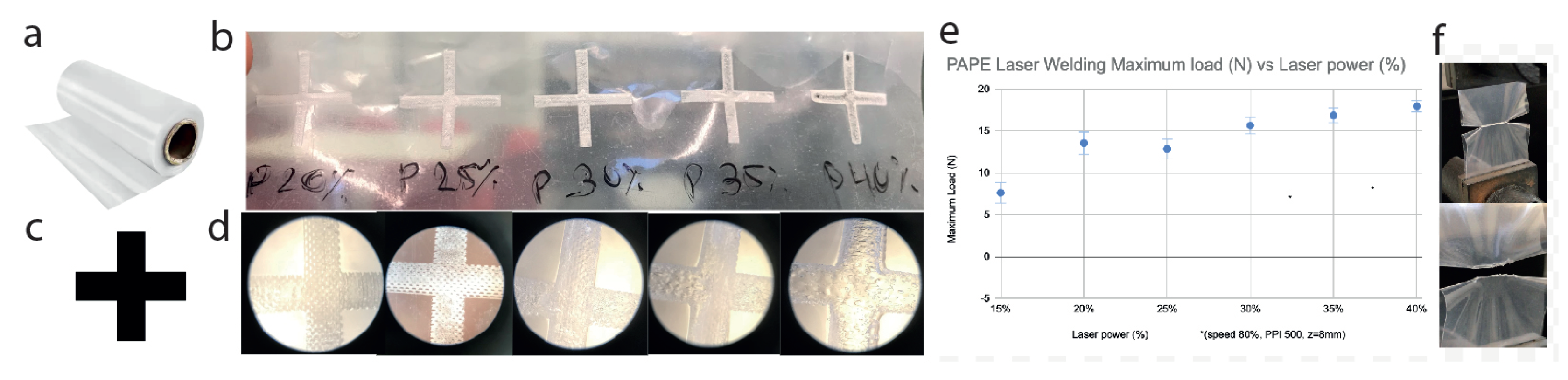

A laser cutter machine (Universal Laser Systems, Inc., model VLS 3.6) equipped with A 60 W CO2 laser with programmable focus was used to cut and weld the film. The thermoplastic film bilayer was a polyamide polyethylene (PAPE) (Plastopil, Israel) as shown in

Figure 1a. The film had a thickness of 140 µm and consisted of two layers, each 70 µm thick, which were layered together with high proximity. To weld the film bilayer, The laser cutting machine was set to a power output of 12-24 watts at maximal speed. The film was placed in the laser cutter, and the laser was focused onto the film layers z = 0.2 mm for cutting and 8 mm for welding with power according to the calibration assay and microscopy analysis (

Figure 1b–f). The laser was then operated over the thermoplastic film bilayer in a continuous motion, generating heat that welds the two film layers together. To calibrate the laser. A raster shape was designed on an Adobe illustrator and was laser welded. with different power settings; the same procedure was used for cutting. The welded and cut film was inspected for any defects or imperfections using a microscope (model 70,Magiscope) with a 5x Eyepiece and 4x objective (

Figure 1d. The maximum load of the welded film bilayers were tested using an Instron testing machine (Instron 3345 tester, Norwood, MA, USA) equipped with a 100 N load cell (

Figure 1e,f). Under optimal settings, This method allowed for precise and reliable welding and cutting of the PAPE film bilayer with minimal heat-induced damage to the film. The resulting welds were strong and leak-tight, making them suitable for use in fluidic systems and therefore for cell cultivation.

2.1.2. Fabrication Back Board

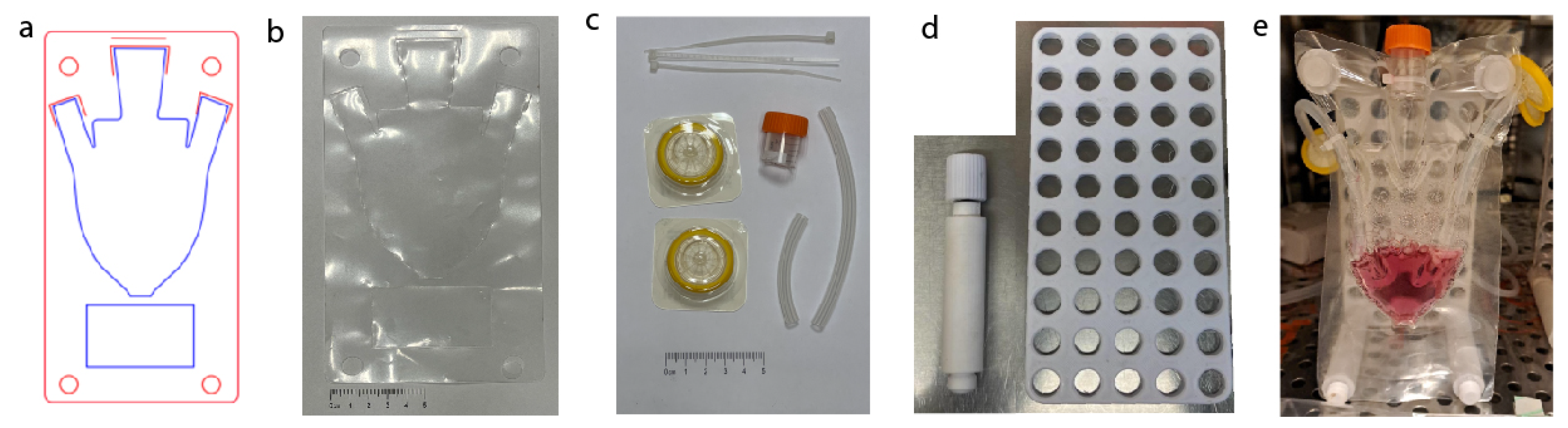

The macrofluidic design is RGB-red for cutting and blue for welding (

Figure 2a,b,e). The back board was 3D printed from ABS, with 14 mm diameter holes (14 mm width). and 3d Printed pegs (Prusa i3 MK3S+, ABS), were used to secure the welded macrofluidic in place and to support the Backboard (

Figure 2d). Unlike a stirred tank bioreactor that has high shear forces, this macrofluidic design is useful for cultivating brittle scaffolds while maintaining overhead gas exchange and allowing manual media exchange. The resulted fluidic did not undergo any internal sterilization post-fabrication. Previous work demonstrated the design and implementation of a ,macrofluidic device for the cultivation of bacteria with a peristaltic pump, a controlled heater and real-time optical sensing [

57].

2.1.3. Air Pump

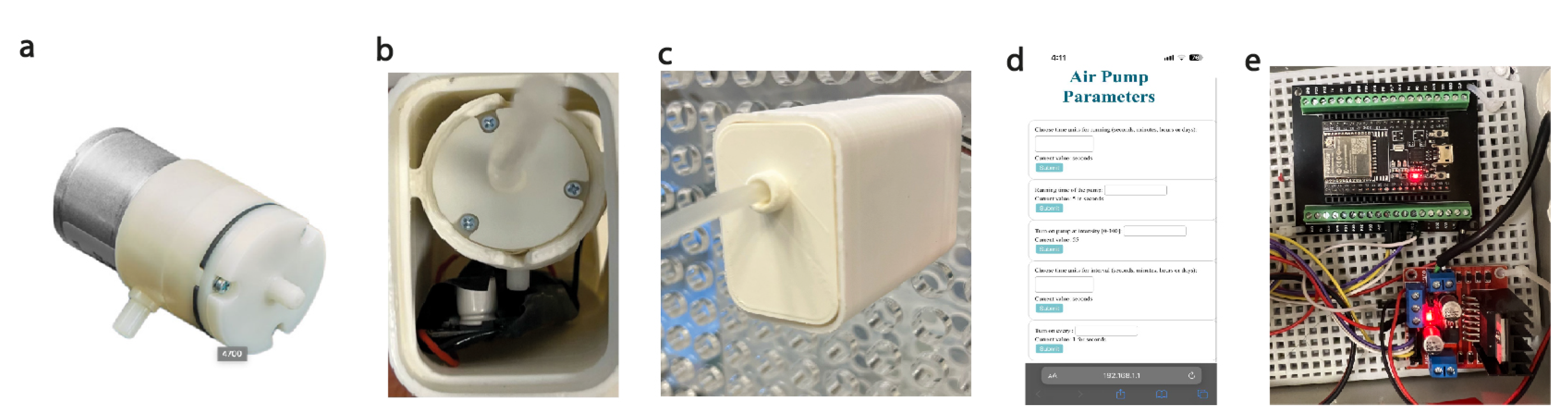

To supply cells with oxygen and CO2 from the incubator environment, we used a 12 V DC 370 mini air pump was used for 3D printing, and an ESP32 microcontroller was used to interface with the H-bridge motor driver (

Figure 3). Using its GPIO (General Purpose Input/Output) pins affords control over the direction and speed of the air pump. Power supply connections were established for both the ESP32 and L298N H-bridge, ensuring proper grounding. Additionally, a user interface accessible via WiFi was implemented on the ESP32, providing a wireless control mechanism. We developed a program utilizing pulse width modulatio(PWM)) to achieve a precise control over the air pump. Upon successful code compilation and upload, the integrated system allowed for versatile and programmable control of the air pump, accessible remotely through the WiFi-enabled user interface.

2.1.4. Macrofluidic Prototyping for Plant Based Scaffolds

The components in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 afford the assembly of a macrofluidic single-use bioreactor tailored for integration within conventional tissue culture laboratories. The primary objective of this design is to maintain a temperature of 37 degrees Celsius, while continuously facilitating the delivery of CO2-enriched air from the incubator. The system incorporates meticulously designed ports to introduce flexible tubes. Each affixed with 0.22-micron filters to enable controlled and filtered air exchange secured by zip ties (

Figure 2c). A specific port, employing a screw cap derived from a 15 ml tube, is allocated at the top for the introduction and extraction of media and scaffolds, The tubes and tube caps were autoclaved and assembled in a laminar flow hood. The inclusion of a conical bottom augments the system’s functionality, allowing for versatile applications from 1-50 ml In addition we designed an area for a label under the conical bottom so that the user can write or put a printed sticker on the MSUB.

2.1.5. Cell Culture and Immortalization

Bovine mesenchymal stem cells (bMSCs), were isolated, cultured, and characterized based on generally accepted criteria [

58,

59] as in [

60]. The bMSC-SV40-hTERT cell line immortalization was achieved by introducing simian virus 40 large T antigen (SV40T, a kind gift from Prof. Sara Selig) by transient transfection, and the human telomerase gene hTERT [

61] by retrovirus-mediated transduction. The cells were grown in low-glucose Dulbecco modified eagle medium (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and a penicillin–streptomycin mixture (3%), and cryopreserved in fetal bovine serum containing 10% DMSO. GFP-expressing cells were acquired using pLKO_047 (Broad Institute) lentiviral vector and Puromycin selection. The cells were cultured in multi-well plates with low glucose DMEM and detached using trypsin. Cell counts were determined with a cell counter (TC20 automated cell counter, Bio-Rad).

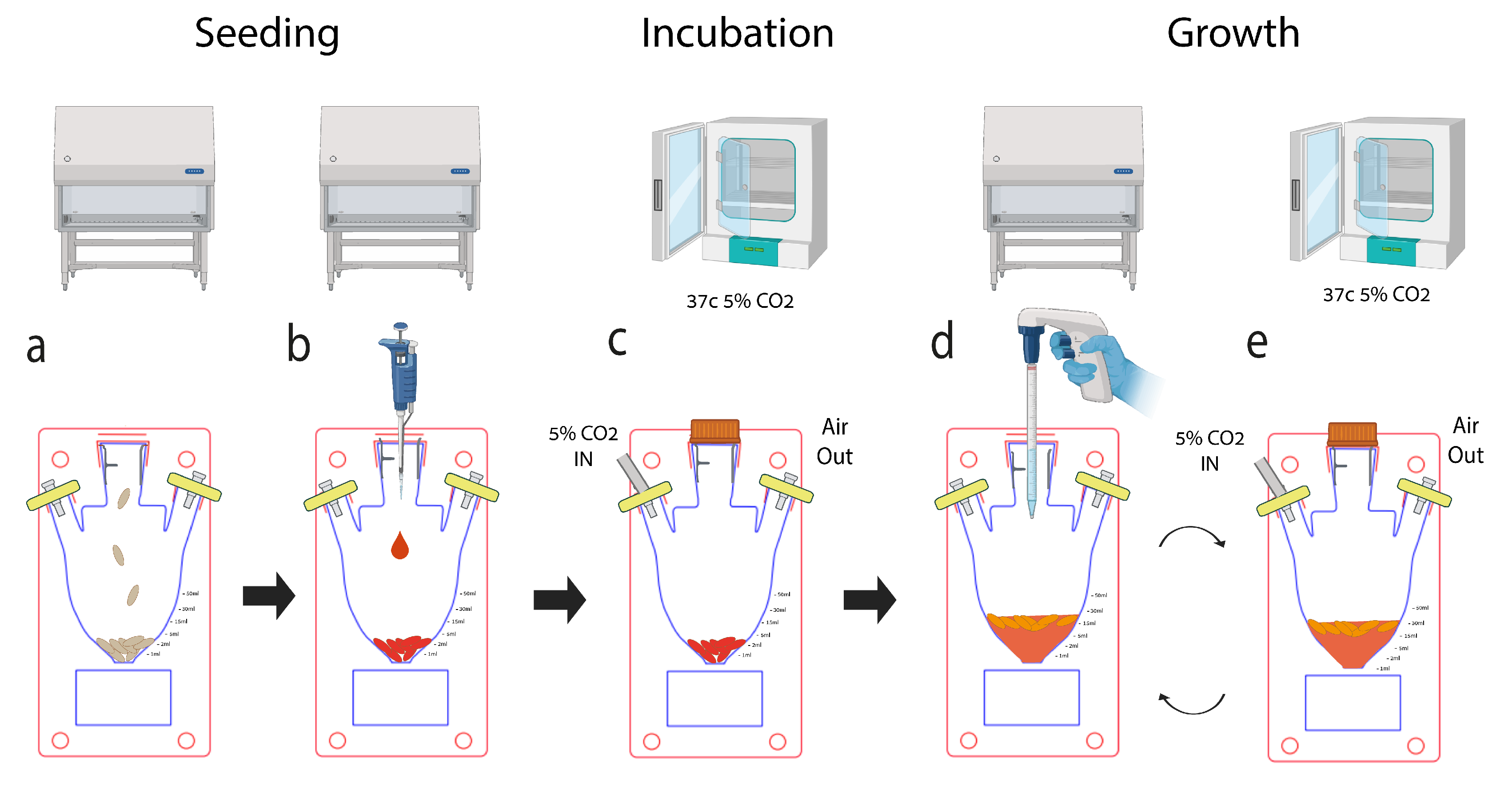

2.1.6. Experimental Setup

Cells were seeded at 5,000 (5K) to 500,000 (500K) cells per scaffold, in 40 µl seeding volume. Following seeding, the scaffolds were placed in a 24-well plate and incubated for 45 minutes at 37°C. Then, 1 ml of growth medium was added to each rice puff scaffold. The scaffolds were carefully transferred to a new 24-well plate using sterile tweezers three days later. Subsequently, 800 µl of a solution comprising a 10:1 ratio of growth medium to Alamar Blue reagent stock solution (3.6% Alamar Blue in PBS) and a 4-hour incubation period. Subsequently, in the MSUB’s and flasks we introduced 10 puffed rice and seeded them with 400 µl of nutristem culture media containing 500K cells in three MSUB as described in

Figure 4 and three 125 ml flasks with vent caps. The cells were maintained in 4 ml of NutriStem® MSC XF Medium (Satorius) in 5% CO2 and 37°C in the MSUB. The air pump was programmed to provide intermittent CO2 enriched air from the incubator passed through the filter into the MSUB. Alamar Blue assay was conducted in the MSUB and flasks in a total volume of 2 ml to determine cell metabolic activity. After 4h of incubation, 100 µl of the medium was transferred to a clear a 96-well plate, and fluorescence readings were taken using a plate reader (BioTek Synergy HT Multi-Mode Microplate Reader; Agilent Technologies, Inc) was used, and the fluorescence was measured at 590 nm following excitation at 520 nm. then, the medium in each well was replaced with 1 ml of fresh medium and 4 ml in the MSUB and flasks. For positive control we seeded 5,000 and 50,000 cells on 2D culture plates without scaffolds 24 hours before plate reader analysis. The negative control consisted of the growth medium, Alamar Blue reagent, and Puffed rice.

2.1.7. Expression of MSC Surface Markers

The expression of MSC positive surface proteins CD29, CD44, CD90, CD105 and CD166 and negative krt19 [

58,

59] was determined using quantitative PCR. The procedure was carried out as described in [

60]. In brief, RNA extraction from cells was carried out using PureLink RNA Midikit (12183018A, Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using High-Capacity cDNA Reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). Real-Time PCR was performed using Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) in an ABI Step-One Plus Real-time PCR system. To ensure validity, each sample was tested in triplicate (technical replicates). The relative mRNA fold change was calculated with the delta ct method, and the levels were normalized against those for bovine PSMB2.

2.1.8. Microscopy

Scaffolds were stained at room temperature using Calcofluor white (3 µl/ml and washed with PBS). Fluorescence imaging was preformed using an Inverted Nikon ECLIPSE TI-DH fluorescent microscope. Confocal imaging was preformed using a Leica SP8 Confocal Microscope. SEM images were acquired by a JSM-7800F A field emission scanning electron microscope, Puffed rice were dryed with a K850 critical point dryer and coated with a Q150T ES Plus at 18mA for 90 sec with 2 nm AuPd. Confocal images were acquired using a Leica SP8 Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope.

3. Results

3.1. Rice-Based Scaffold Microscopy, Water Absorption and pH Assay

Puffed rice is already a dry porous material [

62], each scaffold fitted in a 48 multi-well plate. We used a locally available brand without additives imported in vacuum from Gujarat india (

Figure 5a,d) and autoclaved the scaffolds before use. Scaffold staining with calcofluor white revealed its surface porous structure. The scaffold was tested for pH and liquid retention by conducting a water absorbance assay as shown in

Figure 5 b,e. Water absorption dynamics of the scaffold were determined by ,measuring the dry weight to establish as a baseline (n=5). Controlled water additions and subsequent wet weight measurements allowed for the calculation of percent water absorption. Wet weight measurements following each addition facilitated the calculation of percent water absorption using the formula [(wet weight - dry weight) / dry weight] x 100],which yields insights into the hygroscopic properties of the scaffolds and determination of the seeding volume of 40 µl per rice puff. The pH of DDW was compared to the pH of one rice puff in 1ml of DDW (Eutech pH 700), and no significant alteration in pH was observed (DDW - 6.21, DDW + Rice Puff - 5.98).

3.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

SEM images of dry Puffed rice in cross-section and of the surface. the porous structure of a rice puff is revealed in the cross section (

Figure 6, top row) and on the surface (

Figure 6 bottom row).

3.3. Cell Line Properties in 2D

The primary culture of bovine umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells was extracted as described in [

60]. These cells have a limited number of divisions, after which their division rate slows until they reach a state of cellular aging (senescence) and cease to divide. To obtain a stable line and high proliferation efficiency of cells, we disrupted the cell cycle control of the cells using SV40T, and the telomerase gene (hTERT) was added to allow cells to continue dividing without damaging genomic integrity. Our immortalized bMSC cell line presented a normal morphology (

Figure 7a), and could be subcultured for approximately 150 days at a gradually decreasing rate with high survival rates (

Figure 7b). The results indicated that SV40-hTERT cells, with or without the GFP reporter, had strong proliferation ability and no obvious senescence. Expression of the MSC-markers CD29, CD44, CD90, CD105 and CD166, and the absence of the epithelial marker KRT19, were similar in the transformed and primary cells (

Figure 7c).

3.3.1. Proliferation on Assay in Wells and in MSUB

The cells were evaluated for proliferation in 3D on a rice puff scaffold in wells, the cells proliferated on the rice puff scaffold and reached maximum growth after 10 days (

Figure 8a). When cultured in MSUB and compared to flaks with vented caps there was a triple fold change from day 2 to day 9 in fluorescence measurement of Alamar blue (

Figure 8b). These findings demonstrated that the MSUB can support proliferation of the SV40-hTERT-GFP-GFP cell line on multiple rice puff scaffolds cultivated in one chamber with overhead gas exchange. To investigate cell coverage, we took seeded Puffed rice after 12 days in the MSUB, and then examined under a florescent and confocal microscopes(

Figure 8c,d). this revealed cell penetration and growth throughout the entire scaffold; In addition we used a SEM to evaluate a rice puffs without cells and with cells after 12 days of cultivation (

Figure 8e,f). There was a clear difference in Puffed rice post cultivation imaged by a SEM, the cells adhered to the surface and inside the scaffold and on its surface and they appear as dried sheets and as they are dehydrated in the preparation process, the extra cellular matrix between the cells can also be seen as thin strings stretching between the cell membranes.

4. Discussion

In this study, we introduced a novel method to fabricate macrofluidic systems for cell cultivation, with a specific focus on bioreactor construction and the incorporation of food-grade rice-based scaffolds. The laser welding method we employed demonstrated high efficiency and reliability, creating robust and leak-free seals within polyamide polyethylene (PAPE) films, all while minimizing heat-induced damage to the film. A noteworthy feature of PAPE is its clarity, which enables microscopy and spectral sensing applications. This versatility enhances its applicability across diverse cell cultivation methods and other bioprocesses. It is crucial to highlight that PAPE is extruded in high heat and pressure as a blow film. This process leads to sterility between the sheets, which the laser welding process preserves. Notably, PAPE is already designated and used globally as a food-grade packaging material [

63]. To further enhance environmental sustainability, PET-based films are affordable, recyclable and produced industrially globally [

64,

65].

The integration of rice-based scaffolds into our system exemplifies the versatility of our macrofluidic fabrication method. Companies and researchers use different cells and different growth methods, production pipelines requires different solutions for different stages such as proliferation-expansion in suspension or differentiation-maturation on scaffolds, therefore the versatility of the macrofluidics fabrication method is useful for startup companies that are in the development stage. Harmonizing with its sustainability and scalability objectives through the use of plant-based materials, an MSUB can be designed to fit scaffolds in different shapes and sizes with designated insertion ports that can be welded under sterile conditions after scaffold insertion. We chose Puffed rice as an example to show that our method can answer the unmet needs of a specific scaffold. However, the technology can be tailored to the needs of various scaffolds and processes. Under cultivation over time scaffolds may face shear forces that may cause damage to them, macrofluidics supports the design and implementation of a bioprocess with minimal shear forces to answer these needs. Aeration can be overhead or through the media in the culture area or a separate gas exchange chamber. The volume can be adjusted according to need by the design of the macroluific chamber and by adding media manually or automatically with a pump. Supervision over cultivation in real-time can provide insights into scaled-out MSUBs in the bioprocess. For example, an MSUB that has low seeding efficiency can be monitored in the first days of cultivation using microscopy or with a reagent such as Alamar Blue and be replaced or reseeded, an MSUB that got contaminated can be sensed by sampling the media for turbidity manually or through the film with a light sensor [

57] discarded, potentially saving time and resources for a bioproduction facility that operates in a scale-out model. This supervision can be achieved by adding real time sensors to each MSUB or by a monitoring station. Most cultured meat cultivation is currently carried out in stirred-tank bioreactors without large 3D scaffolds [

26]. The absence of an affordable commercial tissue bioreactor tailored for cultured meat applications that allows for customization presents a significant economic challenge in this field. However, cost-effective materials such as PAPE film, as demonstrated in our study,can substantially reduce bioreactor costs by scaling out and not up. Using a sterile film during production eliminates the need for a separate sterilization step for the culture vessel, streamlining the process and contributing to cost efficiency. Potentially fitting for an aseptic VFFS (vertical form/fill/seal) [

66] system supporting the scaffold insertion and sealing of the MSUB before downstream cultivation. Moreover, the rapid prototyping capabilities afforded by this technique open the door to further research needed to address this critical hurdle in the cultured meat production process.

5. Conclusions

Our results demonstrate the potential of laser welding of PAPE for rapid fabrication of macrofluidic systems for cell cultivation. Combined with immortalized bovine stem cells cultured growing on plant-based-food-grade scaffolds, these findings support broader objectives of sustainable, cost-effective, and scalable cultured meat production, presenting promising possibilities for the future of the cultured meat industry and related fields.

6. Patents

WO2020105044 - BIOLOGICAL FLUIDIC SYSTEM

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.S. and G.G.; methodology, O.S ,SS.; software, I.B, C.W.; validation, G.G., B.C.; formal analysis, O.S. and S.A.; coordination, J.G.; resources G.G, J.G, O.S and S.A.; data curation, G.G.; writing—original draft preparation, G.G.; writing—review and editing, S.A and O.S.; visualization, G.G.; supervision, S.A and O.S.; Cell line preparation and quantification, S.T. D.S; 3D design. A.G; electrical engineering oversight and fabrication I.B, Coding I.B and C.W; project administration, G.G.; funding acquisition, G.G., J.G, S.A and O.S All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Israeli MINISTRY OF INNOVATION, SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, grant number 1001593854 and partially supported by the Israeli Innovation Authority through the cultivated Meat consortium (file number 82446).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

Laser welding of macrofluidics is supported by and sprouted at the media innovation lab (milab) at Reichman University led by prof’ Oren Zuckerman.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PAPE |

Polyethylene-Polyamide |

| MSUB |

Macrofluidic Single-use Bioreactor |

References

- Levi, S.; Yen, F.C.; Baruch, L.; Machluf, M. Scaffolding technologies for the engineering of cultured meat: Towards a safe, sustainable, and scalable production. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2022, 126, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H.; Choi, J. Three-dimensional scaffolds, materials, and fabrication for cultured meat applications: A scoping review and future direction. Food Hydrocolloids, 2024; 109881. [Google Scholar]

- Bomkamp, C.; Skaalure, S.C.; Fernando, G.F.; Ben-Arye, T.; Swartz, E.W.; Specht, E.A. Scaffolding biomaterials for 3D cultivated meat: prospects and challenges. Advanced Science 2022, 9, 2102908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seah, J.S.H.; Singh, S.; Tan, L.P.; Choudhury, D. Scaffolds for the manufacture of cultured meat. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 2022, 42, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Sood, A.; Han, S.S. Technological and structural aspects of scaffold manufacturing for cultured meat: recent advances, challenges, and opportunities. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2023, 63, 585–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhao, X.; Li, X.; Du, G.; Zhou, J.; Chen, J. Challenges and possibilities for bio-manufacturing cultured meat. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2020, 97, 443–450. [Google Scholar]

- Modulevsky, D.J.; Lefebvre, C.; Haase, K.; Al-Rekabi, Z.; Pelling, A.E. Apple derived cellulose scaffolds for 3D mammalian cell culture. PloS one 2014, 9, e97835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Arye, T.; Shandalov, Y.; Ben-Shaul, S.; Landau, S.; Zagury, Y.; Ianovici, I.; Lavon, N.; Levenberg, S. Textured soy protein scaffolds enable the generation of three-dimensional bovine skeletal muscle tissue for cell-based meat. Nature Food 2020, 1, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, N.; Yuen Jr, J.S.; Stout, A.J.; Rubio, N.R.; Chen, Y.; Kaplan, D.L. 3D porous scaffolds from wheat glutenin for cultured meat applications. Biomaterials 2022, 285, 121543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-Shai, N.; Sharabani-Yosef, O.; Zollmann, M.; Lesman, A.; Golberg, A. Seaweed cellulose scaffolds derived from green macroalgae for tissue engineering. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 11843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, M.; Jung, S.; Lee, H.; Choi, B.; Choi, M.; Lee, J.M.; Yoo, K.H.; Han, D.; Lee, S.T. ; others. Rice grains integrated with animal cells: A shortcut to a sustainable food system. Matter, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- De Wilde, D.; Dreher, T.; Zahnow, C.; Husemann, U.; Greller, G.; Adams, T.; Fenge, C. Superior scalability of single-use bioreactors. Innovations in Cell Culture 2014, 14, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kurt, T.; Höing, T.; Oosterhuis, N. The Potential Application of Single-Use Bioreactors in Cultured Meat Production. Chemie Ingenieur Technik 2022, 94, 2026–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodiou, V.; Moutsatsou, P.; Post, M.J. Microcarriers for upscaling cultured meat production. Frontiers in nutrition 2020, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, S.; Roy, A. Selecting high amylose rice variety for puffing: A correlation between physicochemical parameters and sensory preferences. Measurement: Food 2022, 5, 100021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Huang, R.; Wang, S.; Dong, Y.; Lv, J.; Zhong, W.; Yan, F. Effects of Explosion Puffing on the Composition, Structure, and Functional Characteristics of Starch and Protein in Grains. ACS Food Science & Technology 2021, 1, 1869–1879. [Google Scholar]

- Bagchi, T.; Chattopadhyay, K.; Sarkar, S.; Sanghamitra, P.; Kumar, A.; Basak, N.; Sivashankari, M.; Priyadarsini, S.; Pathak, H. Rice Products and their Nutritional Status. Research Bulletin 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pashkuleva, I.; López-Pérez, P.M.; Azevedo, H.S.; Reis, R.L. Highly porous and interconnected starch-based scaffolds: production, characterization and surface modification. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2010, 30, 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi-Mobarakeh, L.; Prabhakaran, M.P.; Tian, L.; Shamirzaei-Jeshvaghani, E.; Dehghani, L.; Ramakrishna, S. Structural properties of scaffolds: crucial parameters towards stem cells differentiation. World journal of stem cells 2015, 7, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okano, T.; Yamada, N.; Okuhara, M.; Sakai, H.; Sakurai, Y. Mechanism of cell detachment from temperature-modulated, hydrophilic-hydrophobic polymer surfaces. Biomaterials 1995, 16, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.H.; Khil, M.S.; Kim, H.Y.; Lee, H.U.; Jahng, K.Y. An improved hydrophilicity via electrospinning for enhanced cell attachment and proliferation. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials: An Official Journal of The Society for Biomaterials, The Japanese Society for Biomaterials, and The Australian Society for Biomaterials and the Korean Society for Biomaterials 2006, 78, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbett, T.A.; Schway, M.B.; Ratner, B.D. Hydrophilic-hydrophobic copolymers as cell substrates: Effect on 3T3 cell growth rates. Journal of colloid and interface science 1985, 104, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbardelotto, P.R.; Balbinot-Alfaro, E.; da Rocha, M.; Alfaro, A.T. Natural alternatives for processed meat: Legislation, markets, consumers, opportunities and challenges. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2023, 63, 10303–10318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- India, E. Puffed Rice Suppliers in India. https://www.exportersindia.com/indian-suppliers/puffed-rice.htm, year = 2024. Date Accessed: February 11, 2024.

- IndiaMART. Puffed Rice Suppliers on IndiaMART. https://dir.indiamart.com/impcat/puffed-rice.htm, year = 2024. Date Accessed: February 11, 2024.

- Chen, L.; Guttieres, D.; Koenigsberg, A.; Barone, P.W.; Sinskey, A.J.; Springs, S.L. Large-scale cultured meat production: Trends, challenges and promising biomanufacturing technologies. Biomaterials 2022, 280, 121274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djisalov, M.; Knežić, T.; Podunavac, I.; Živojević, K.; Radonic, V.; Knežević, N.Ž.; Bobrinetskiy, I.; Gadjanski, I. Cultivating multidisciplinarity: Manufacturing and sensing challenges in cultured meat production. Biology 2021, 10, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, G.L.; Biermacher, J.T.; Brorsen, B.W. How much will large-scale production of cell-cultured meat cost? Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2022, 10, 100358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomisto, H.L.; Allan, S.J.; Ellis, M.J. Prospective life cycle assessment of a bioprocess design for cultured meat production in hollow fiber bioreactors. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 851, 158051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, C.; Selvaganapathy, P.R.; Geng, F. Advancing our understanding of bioreactors for industrial-sized cell culture: health care and cellular agriculture implications. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology 2023, 325, C580–C591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, S.J.; De Bank, P.A.; Ellis, M.J. Bioprocess design considerations for cultured meat production with a focus on the expansion bioreactor. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2019, 3, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangadurai, M.; Srinivasan, S.S.; Sekar, M.P.; Sethuraman, S.; Sundaramurthi, D. Emerging perspectives on 3D printed bioreactors for clinical translation of engineered and bioprinted tissue constructs. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balakrishnan, H.K.; Doeven, E.H.; Merenda, A.; Dumée, L.F.; Guijt, R.M. 3D printing for the integration of porous materials into miniaturised fluidic devices: A review. Analytica chimica acta 2021, 1185, 338796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, C.; Patrick, W.G.; Kolb, D.; Hays, S.G.; Keating, S.; Sharma, S.; Dikovsky, D.; Belocon, B.; Weaver, J.C.; Silver, P.A.; others. Grown, printed, and biologically augmented: An additively manufactured microfluidic wearable, functionally templated for synthetic microbes. 3D Printing and Additive Manufacturing 2016, 3, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini, B.M.; Dikshit, V.; Zhang, Y. 3D-printed bioreactors for in vitro modeling and analysis. International Journal of Bioprinting 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkel, M.; Noll, P.; Lilge, L.; Hausmann, R.; Henkel, M. Design and evaluation of a 3D-printed, lab-scale perfusion bioreactor for novel biotechnological applications. Biotechnology Journal 2023, 18, 2200554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linz, G.; Rauer, S.B.; Kuhn, Y.; Wennemaring, S.; Siedler, L.; Singh, S.; Wessling, M. 3D-Printed Bioreactor with Integrated Impedance Spectroscopy for Cell Barrier Monitoring. Advanced Materials Technologies 2021, 6, 2100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.; Kurisawa, M. Integrating biomaterials and food biopolymers for cultured meat production. Acta Biomaterialia 2021, 124, 108–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Wu, J.Y.; Kennedy, K.M.; Yeager, K.; Bernhard, J.C.; Ng, J.J.; Zimmerman, B.K.; Robinson, S.; Durney, K.M.; Shaeffer, C.; others. Tissue engineered autologous cartilage-bone grafts for temporomandibular joint regeneration. Science translational medicine 2020, 12, eabb6683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borisov, V.; Gili Sole, L.; Reid, G.; Milan, G.; Hutter, G.; Grapow, M.; Eckstein, F.S.; Isu, G.; Marsano, A. Upscaled Skeletal Muscle Engineered Tissue with In Vivo Vascularization and Innervation Potential. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samandari, M.; Saeedinejad, F.; Quint, J.; Chuah, S.X.Y.; Farzad, R.; Tamayol, A. Repurposing biomedical muscle tissue engineering for cellular agriculture: challenges and opportunities. Trends in Biotechnology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humbird, D. Scale-up economics for cultured meat. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 2021, 118, 3239–3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, C.W. Polymer microfluidics: Simple, low-cost fabrication process bridging academic lab research to commercialized production. Micromachines 2016, 7, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Ou, J.; Wilbert, J.; Haben, A.; Mi, H.; Ishii, H. milliMorph–Fluid-Driven Thin Film Shape-Change Materials for Interaction Design. In Proceedings of the 32nd Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology; 2019; pp. 663–672. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelgawad, M.; Wheeler, A.R. Low-cost, rapid-prototyping of digital microfluidics devices. Microfluidics and nanofluidics 2008, 4, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, E.; Cesaria, M.; Zizzari, A.; Bianco, M.; Ferrara, F.; Raia, L.; Guarino, V.; Cuscunà, M.; Mazzeo, M.; Gigli, G.; others. Potential of CO2-laser processing of quartz for fast prototyping of microfluidic reactors and templates for 3D cell assembly over large scale. Materials Today Bio 2021, 12, 100163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadat, M.; Taylor, M.; Hughes, A.; Hajiyavand, A.M. Rapid prototyping method for 3D PDMS microfluidic devices using a red femtosecond laser. Advances in Mechanical Engineering 2020, 12, 1687814020982713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosic, S.; Bindas, A.J.; Puzan, M.L.; Lake, W.; Soucy, J.R.; Zhou, F.; Koppes, R.A.; Breault, D.T.; Murthy, S.K.; Koppes, A.N. Rapid prototyping of multilayer microphysiological systems. ACS biomaterials science & engineering 2020, 7, 2949–2963. [Google Scholar]

- Hanga, M.P.; Ali, J.; Moutsatsou, P.; de la Raga, F.A.; Hewitt, C.J.; Nienow, A.; Wall, I. Bioprocess development for scalable production of cultivated meat. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 2020, 117, 3029–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirsch, M.; Morales-Dalmau, J.; Lavrentieva, A. Cultivated meat manufacturing: Technology, trends, and challenges. Engineering in Life Sciences 2023, 23, e2300227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klebe, R.J.; Lyn, S.; Magnuson, V.L.; Zardeneta, G. Cultivation of mammalian cells in heat-sealable pouches that are permeable to carbon dioxide. Experimental Cell Research 1990, 188, 316–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaegh, S.A.M.; Pourmand, A.; Nabavinia, M.; Avci, H.; Tamayol, A.; Mostafalu, P.; Ghavifekr, H.B.; Aghdam, E.N.; Dokmeci, M.R.; Khademhosseini, A.; others. Rapid prototyping of whole-thermoplastic microfluidics with built-in microvalves using laser ablation and thermal fusion bonding. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2018, 255, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truckenmüller, R.; Giselbrecht, S.; van Blitterswijk, C.; Dambrowsky, N.; Gottwald, E.; Mappes, T.; Rolletschek, A.; Saile, V.; Trautmann, C.; Weibezahn, K.F.; others. Flexible fluidic microchips based on thermoformed and locally modified thin polymer films. Lab on a Chip 2008, 8, 1570–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, H.; Lim, H.R.; Kim, Y.S.; Hoang, T.T.T.; Choi, J.; Jeong, G.J.; Kim, H.; Herbert, R.; Soltis, I.; others. Large-scale smart bioreactor with fully integrated wireless multivariate sensors and electronics for long-term in situ monitoring of stem cell culture. Science Advances 2024, 10, eadk6714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Griffin, M.; Cai, J.; Li, S.; Bulter, P.E.; Kalaskar, D.M. Bioreactors for tissue engineering: An update. Biochemical Engineering Journal 2016, 109, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryawanshi, P.L.; Gumfekar, S.P.; Bhanvase, B.A.; Sonawane, S.H.; Pimplapure, M.S. A review on microreactors: Reactor fabrication, design, and cutting-edge applications. Chemical Engineering Science 2018, 189, 431–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gome, G.; Fein, Y.; Waksberg, J.; Maayan, Y.; Grishko, A.; Wald, I.Y.; Zuckerman, O. My First Biolab: a System for Hands-On Biology Experiments. Extended Abstracts of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2019, pp. 1–6.

- Baksh, D.; Song, L.; Tuan, R.S. Adult mesenchymal stem cells: characterization, differentiation, and application in cell and gene therapy. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine 2004, 8, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, A.B.T.; Bressan, F.F.; Murphy, B.D.; Garcia, J.M. Applications of mesenchymal stem cell technology in bovine species. Stem Cell Research & Therapy 2019, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Shimoni, C.; Goldstein, M.; Ribarski-Chorev, I.; Schauten, I.; Nir, D.; Strauss, C.; Schlesinger, S. Heat shock alters mesenchymal stem cell identity and induces premature senescence. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 2020; 956. [Google Scholar]

- Addgene. Human telomerase gene hTERT.

- Wongsa, J.; Uttapap, D.; Lamsal, B.P.; Rungsardthong, V. Effect of puffing conditions on physical properties and rehydration characteristic of instant rice product. International Journal of Food Science & Technology 2016, 51, 672–680. [Google Scholar]

- Shinde, R.; Vinokur, Y.; Fallik, E.; Rodov, V. Effects of Genotype and Modified Atmosphere Packaging on the Quality of Fresh-Cut Melons. Foods 2024, 13, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.D.; Ren, P.G.; Zhong, G.J.; Olah, A.; Li, Z.M.; Baer, E.; Zhu, L. Promising strategies and new opportunities for high barrier polymer packaging films. Progress in Polymer Science, 2023; 101722. [Google Scholar]

- Horsthuis, E. The future of plastic packaging for the fresh food industry. Master’s thesis, University of Twente, 2023.

- Caldwell, D.G. Automation in Food Manufacturing and Processing. In Springer Handbook of Automation; Springer, 2023; pp. 949–971.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).