Submitted:

24 June 2024

Posted:

26 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

9.1. Introduction

9.2. The Metabolic Network Linking Carbohydrates to Lipids

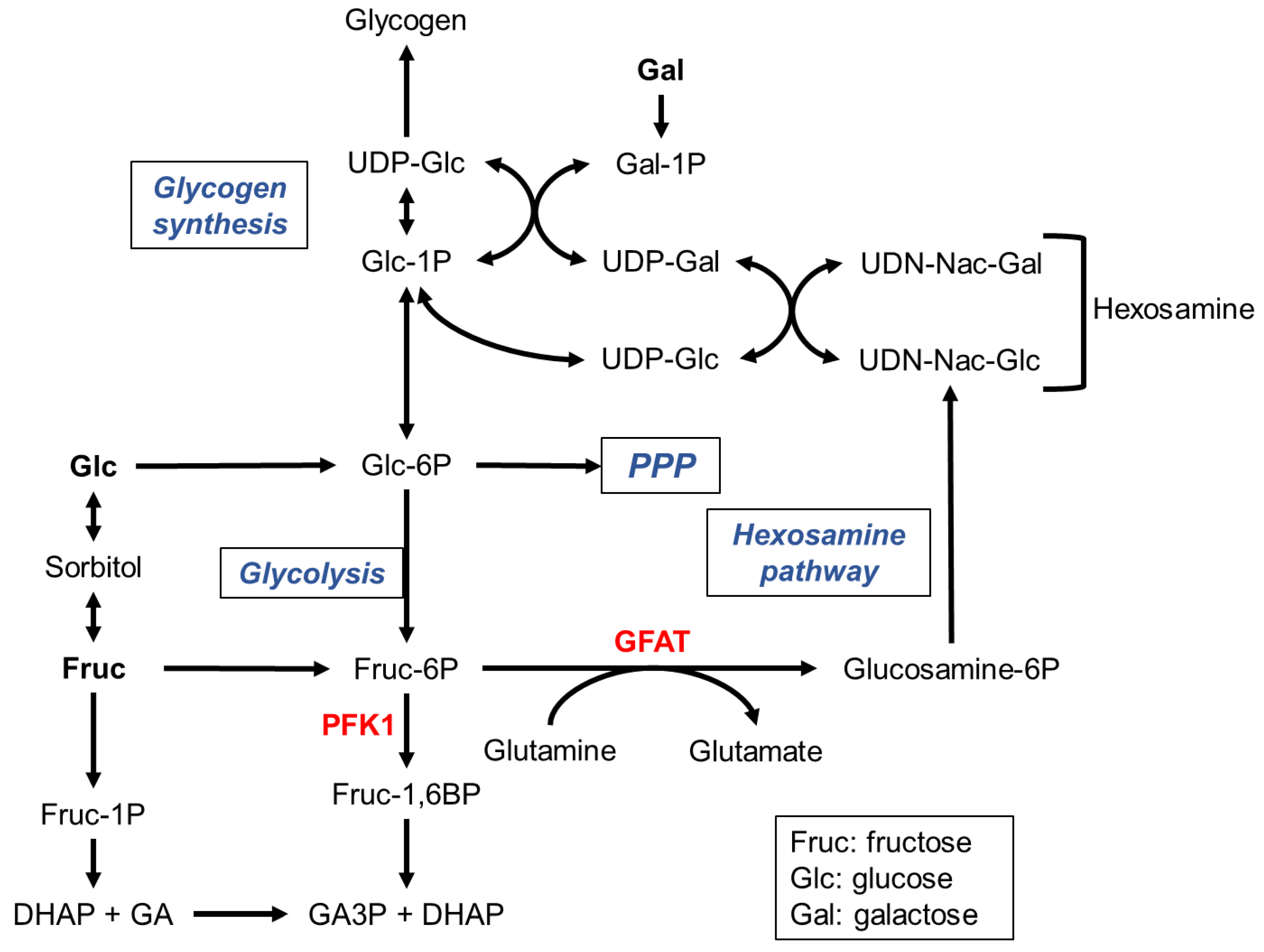

9.2.1. Monosaccharide Fates

9.2.2. Glycolytic Products and Byproducts

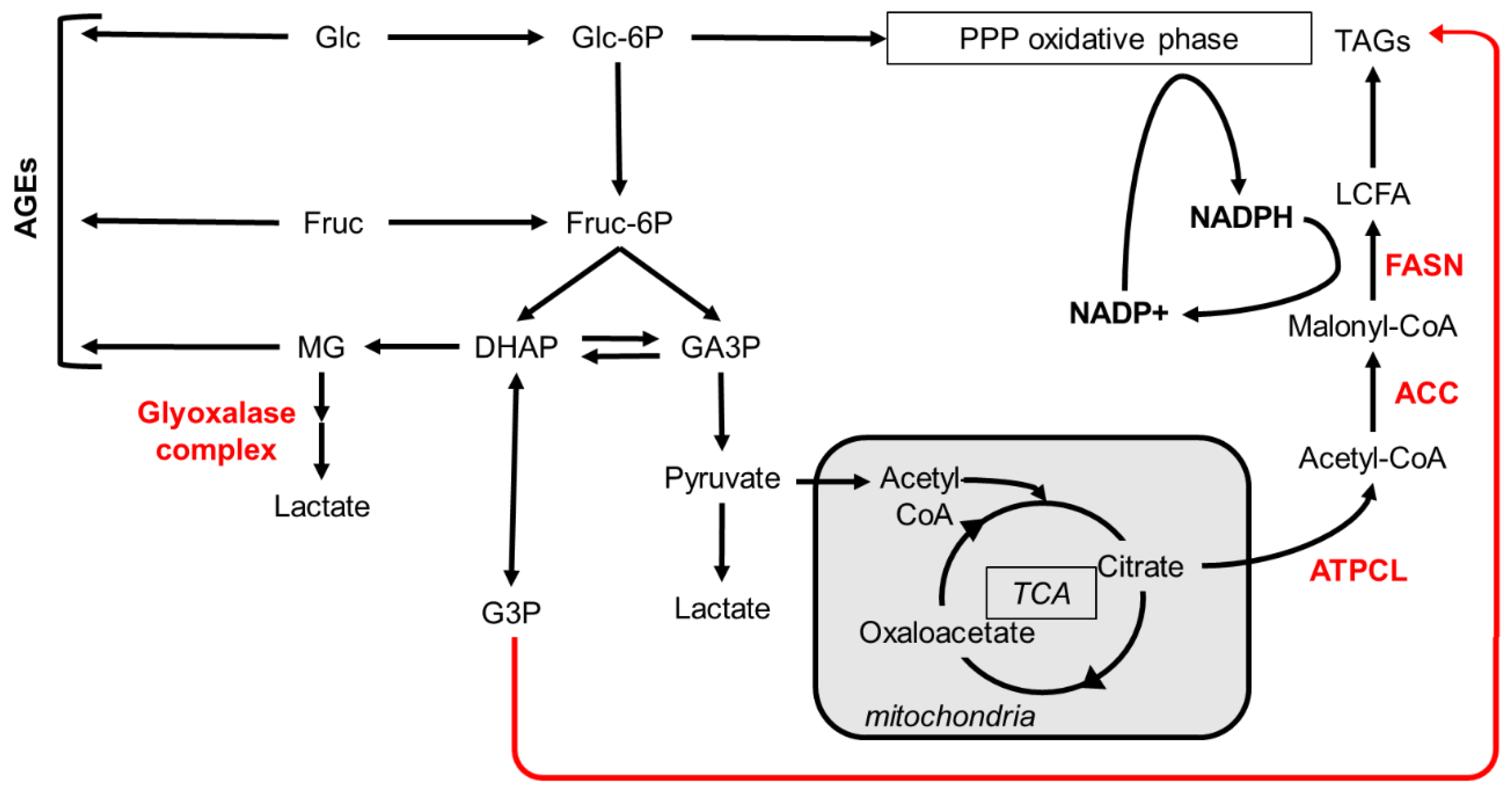

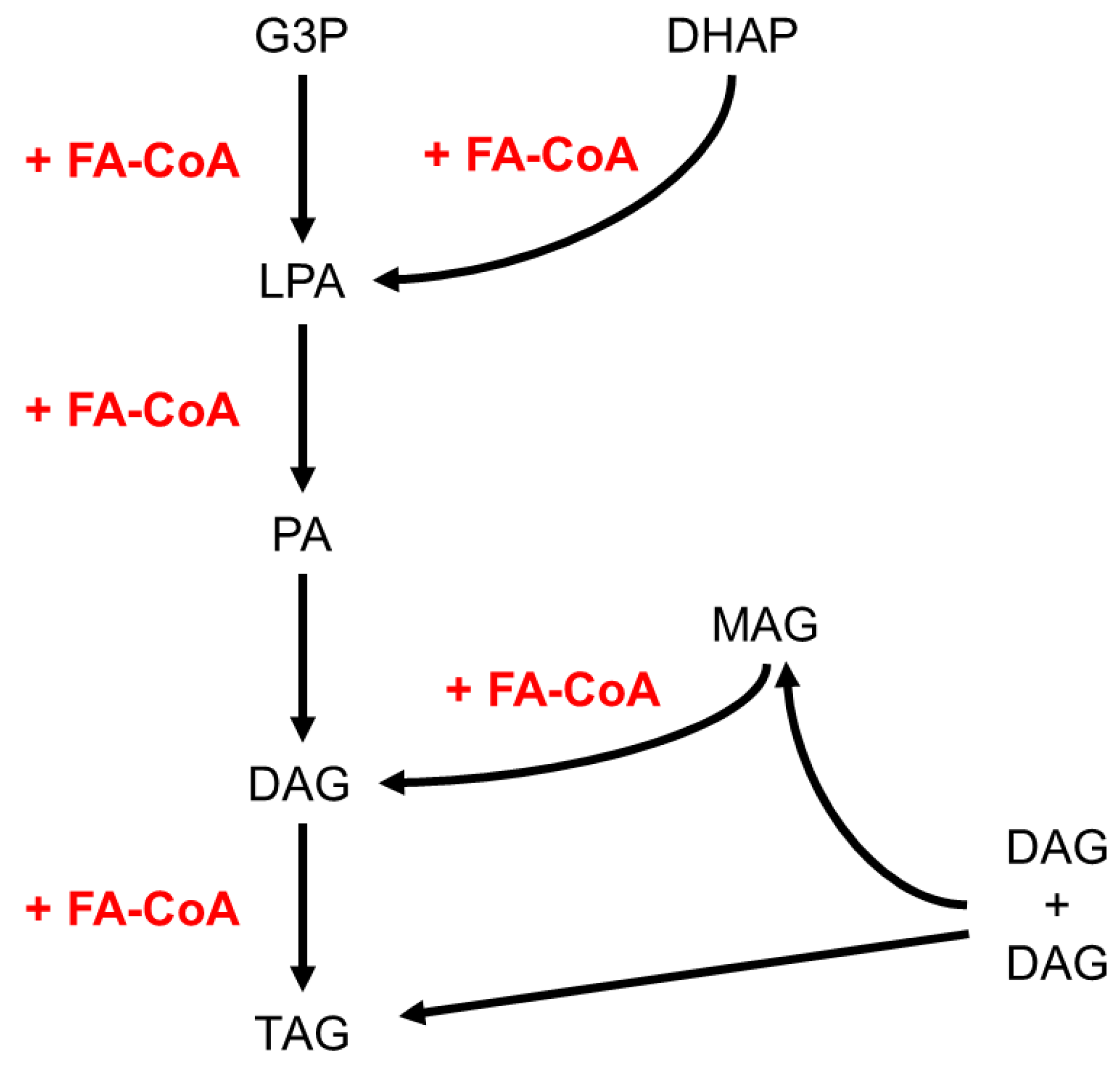

9.2.3. Lipid Metabolism

9.3. Major Organs Implicated

9.3.1. Digestive Tract

9.3.2. Fat Body and Oenocytes

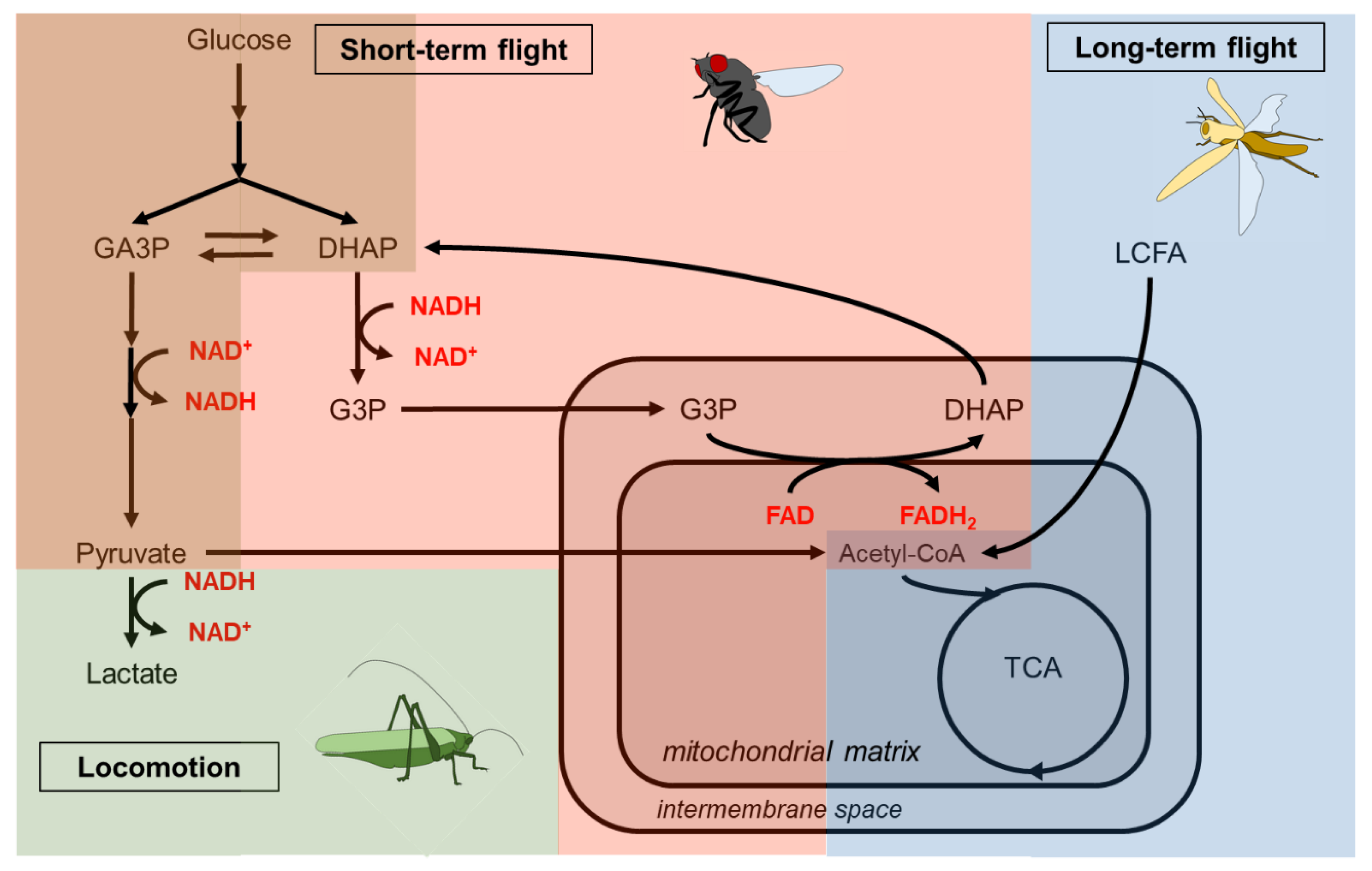

9.3.3. Muscles

9.4. Integration of Carbohydrate/Lipid Metabolism at the Body Level

9.4.1. Carbohydrate and Lipid Homeostasis

9.4.2. Sugar Diet and Type 2 Diabetic-Like Syndrome in D. melanogaster

9.4.3. Sugar Toxicity and Lipogenesis

References

- Adeva-Andany, M.M.; González-Lucán, M.; Donapetry-García, C.; Fernández-Fernández, C.; Ameneiros-Rodríguez, E. Glycogen metabolism in humans. BBA Clin. 2016, 5, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeva-Andany, M.M.; Pérez-Felpete, N.; Fernández-Fernández, C.; Donapetry-García, C.; Pazos-García, C. Liver glucose metabolism in humans. Biosci. Rep. 2016, 36, e00416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbanyo, M.; Taylor, N.F. Incorporation of 3-deoxy-3-fluoro-D-glucose into glycogen and trehalose in fat body and flight muscle in Locusta migratoria. Biosci. Rep. 1986, 6, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Finley, C.; Steele, J. Evidence for the participation of arachidonic acid metabolites in trehalose efflux from the hormone activated fat body of the cockroach (Periplaneta americana). J. Insect Physiol. 1998, 44, 1119–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Steele, J. Fatty Acids Stimulate Trehalose Synthesis in Trophocytes of the Cockroach (Periplaneta americana) Fat Body. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1997, 108, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.L.; Mertens, J.A. Molecular Cloning and Expression of Three Polygalacturonase cDNAs from the Tarnished Plant Bug,Lygus lineolaris. J. Insect Sci. 2008, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves-Bezerra, M.; De Paula, I.F.; Medina, J.M.; Silva-Oliveira, G.; Medeiros, J.S.; Gäde, G.; Gondim, K.C. Adipokinetic hormone receptor gene identification and its role in triacylglycerol metabolism in the blood-sucking insect Rhodnius prolixus. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016, 69, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves-Bezerra, M.; Gondim, K.C. Triacylglycerol biosynthesis occurs via the glycerol-3-phosphate pathway in the insect Rhodnius prolixus. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2012, 1821, 1462–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, A.N.; Lorenz, M.W. Age-dependent changes of fat body stores and the regulation of fat body lipid synthesis and mobilisation by adipokinetic hormone in the last larval instar of the cricket, Gryllus bimaculatus. J. Insect Physiol. 2008, 54, 1404–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annandale, M.; Daniels, L.J.; Li, X.; Neale, J.P.H.; Chau, A.H.L.; Ambalawanar, H.A.; James, S.L.; Koutsifeli, P.; Delbridge, L.M.D.; Mellor, K.M. Fructose Metabolism and Cardiac Metabolic Stress. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 695486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrese, E.L.; Soulages, J.L. Insect Fat Body: Energy, Metabolism, and Regulation. Annu. Rev. Èntomol. 2010, 55, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerswald, L. & G, G. A. 1995. Energy substrates for flight in the blister beetle Decapotoma lunata (Meloidae). J Exp Biol, 198(Pt 6), pp 1423-31.

- Auerswald, L.; Schneider, P.; Gäde, G. Utilisation of Substrates During Tethered Flight with and without Lift Generation in the African Fruit Beetle Pachnoda Sinuata (Cetoniinae). J. Exp. Biol. 1998, 201, 2333–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, S.H.; Kaufman, R.J. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Type 2 Diabetes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2012, 81, 767–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, E.; A Horne, J.; Izarr, M.E.G.; Hill, L. The role of ketone bodies in the metabolism of the adult desert locust. Biochem. J. 1972, 128, 79P–79P. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, M. C. , Price, N. T. & Travers, M. T. 2005. Structure and regulation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase genes of metazoa. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1733(1), pp 1-28.

- Bartok, O.; Teesalu, M.; Ashwall-Fluss, R.; Pandey, V.; Hanan, M.; Rovenko, B.M.; Poukkula, M.; Havula, E.; Moussaieff, A.; Vodala, S.; et al. The transcription factor Cabut coordinates energy metabolism and the circadian clock in response to sugar sensing. EMBO J. 2015, 34, 1538–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, A.; Schlöder, P.; Steele, J.E.; Wegener, G. The regulation of trehalose metabolism in insects. Experientia 1996, 52, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beenakkers, A. Carbohydrate and fat as a fuel for insect flight. A comparative study. J. Insect Physiol. 1969, 15, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkel, B.F.; A Hickey, D. GLUCOSE REPRESSION OF AMYLASE GENE EXPRESSION IN DROSOPHILA MELANOGASTER. Genetics 1986, 114, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bifano, T.D.; Alegria, T.G.; Terra, W.R. Transporters involved in glucose and water absorption in the Dysdercus peruvianus (Hemiptera: Pyrrhocoridae) anterior midgut. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B: Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010, 157, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, M.L.; Lee, R.J.; Magallanes, J.M.; Foskett, J.K.; Birnbaum, M.J. AMPK supports growth in Drosophila by regulating muscle activity and nutrient uptake in the gut. Dev. Biol. 2010, 344, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomquist, G.J.; Ginzel, M.D. Chemical Ecology, Biochemistry, and Molecular Biology of Insect Hydrocarbons. Annu. Rev. Èntomol. 2021, 66, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, P. H. & Hickey, D. A. 1986. The alpha-amylase gene in Drosophila melanogaster: nucleotide sequence, gene structure and expression motifs. Nucleic Acids Res, 14(21), pp 8399-411.

- Braz, V.; Selim, L.; Gomes, G.; Costa, M.L.; Mermelstein, C.; Gondim, K.C. Blood meal digestion and changes in lipid reserves are associated with the post-ecdysis development of the flight muscle and ovary in young adults of Rhodnius prolixus. J. Insect Physiol. 2023, 146, 104492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briegel, H.; Hefti, M.; DiMarco, E. Lipid metabolism during sequential gonotrophic cycles in large and small female Aedes aegypti. J. Insect Physiol. 2002, 48, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookheart, R. T. , Michel, C. I. & Schaffer, J. E. 2009. As a matter of fat. Cell Metab, 10(1), pp 9-12.

- Brooks, G.A. Amino acid and protein metabolism during exercise and recovery. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1987, 19, S150–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bursell, E. 1981. The Role of Proline in Energy Metabolism. In: Downer, R. G. H. (ed.) Energy Metabolism in Insects. Plenum Press, New York.

- Caccia, S.; Leonardi, M.; Casartelli, M.; Grimaldi, A.; de Eguileor, M.; Pennacchio, F.; Giordana, B. Nutrient absorption by Aphidius ervi larvae. J. Insect Physiol. 2005, 51, 1183–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Cortés, N.; Quesada, M.; Watanabe, H.; Cano-Camacho, H.; Oyama, K. Endogenous Plant Cell Wall Digestion: A Key Mechanism in Insect Evolution. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2012, 43, 45–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Canavoso, L.; Stariolo, R.; Rubiolo, E.R. Flight metabolism in Panstrongylus megistus (Hemiptera: Reduviidae): the role of carbohydrates and lipids. Mem. Do Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2003, 98, 909–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel, N. S. 2022. Carbohydrate Metabolism. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 13(a040568.

- Chapman, R. F. , Simpson, S. J. & Douglas, A. E. 2013. The Insects. Structure and Function., Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Childress, C.C.; Sacktor, B. Regulation of glycogen metabolism in insect flight muscle. Purification and properties of phosphorylases in vitro and in vivo.. 1970, 245, 2927–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childress, C. C. , Sacktor, B., Grossman, I. W. & Bueding, E. 1970. Isolation, ultrastructure, and biochemal characterization of glycogen in insect flight muscle. J Cell Biol, 45(1), pp 83-90.

- Chino, H. & Downer, R. G. H. 1979. The role of diacylglycerol in absorption of dietary glyceride in the american cockroach Periplanata americana L.. Insect Biochem., 9(379-382.

- Chng, W. A. , Sleiman, M. S. B., Schupfer, F. & Lemaitre, B. 2014. Transforming growth factor beta/activin signaling functions as a sugar-sensing feedback loop to regulate digestive enzyme expression. Cell Rep, 9(1), pp 336-348.

- Chowański, S.; Walkowiak-Nowicka, K.; Winkiel, M.; Marciniak, P.; Urbański, A.; Pacholska-Bogalska, J. Insulin-Like Peptides and Cross-Talk With Other Factors in the Regulation of Insect Metabolism. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 701203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christeller, J.T.; Amara, S.; Carrière, F. Galactolipase, phospholipase and triacylglycerol lipase activities in the midgut of six species of lepidopteran larvae feeding on different lipid diets. J. Insect Physiol. 2011, 57, 1232–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.J.; Block, K. The absence of sterol synthesis in insects. . 1959, 234, 2578–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, A. N. 1959. Studies on the metabolism of locust fat body J. Exptl. Biol., 36(665-.

- Coleman, R.A. It takes a village: channeling fatty acid metabolism and triacylglycerol formation via protein interactomes. J. Lipid Res. 2019, 60, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, R.A.; Mashek, D.G. Mammalian Triacylglycerol Metabolism: Synthesis, Lipolysis, and Signaling. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 6359–6386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombani, J.; Raisin, S.; Pantalacci, S.; Radimerski, T.; Montagne, J.; Léopold, P. A Nutrient Sensor Mechanism Controls Drosophila Growth. Cell 2003, 114, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csibi, A.; Fendt, S.-M.; Li, C.; Poulogiannis, G.; Choo, A.Y.; Chapski, D.J.; Jeong, S.M.; Dempsey, J.M.; Parkhitko, A.; Morrison, T.; et al. TThe mTORC1 pathway stimulates glutamine metabolism and cell proliferation by repressing SIRT4. Cell 2013, 153, 840–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daenzer, J. M. & Fridovich-Keil, J. L. 2017. Drosophila melanogaster Models of Galactosemia. Curr Top Dev Biol, 121(377-395.

- Deng, D.; Yan, N. GLUT, SGLT, and SWEET: Structural and mechanistic investigations of the glucose transporters. Protein Sci. 2015, 25, 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devilliers, M. , Garrido, D., Poidevin, M., Rubin, T., Le Rouzic, A. & Montagne, J. 2021. Differential Metabolic Sensitivity of Insulin-like-response- and mTORC1-Dependent Overgrowth in Drosophila Fat Cells. Genetics, 217(1), pp 1-12.

- Downer, R.; Matthews, J. Glycogen depletion of thoracic musculature during flight in the American cockroach, Periplaneta americana L. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B: Comp. Biochem. 1976, 55, 501–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drahun, I.; Poole, E.A.; Hunt, K.A.; van Herk, W.G.; LeMoine, C.M.; Cassone, B.J. Seasonal turnover and insights into the overwintering biology of wireworms (Coleoptera: Elateridae) in the Canadian Prairies. Pest Manag. Sci. 2023, 79, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eanes, W.F.; Merritt, T.J.S.; Flowers, J.M.; Kumagai, S.; Sezgin, E.; Zhu, C.-T. Flux control and excess capacity in the enzymes of glycolysis and their relationship to flight metabolism inDrosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006, 103, 19413–19418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, D.E.; de Paula, F.F.P.; Rodrigues, A.; Henrique-Silva, F. Pectinases From Sphenophorus levis Vaurie, 1978 (Coleoptera: Curculionidae): Putative Accessory Digestive Enzymes. J. Insect Sci. 2015, 15, 5–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Ye, J.; Kamphorst, J.J.; Shlomi, T.; Thompson, C.B.; Rabinowitz, J.D. Quantitative flux analysis reveals folate-dependent NADPH production. Nature 2014, 510, 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faust, J.E.; Manisundaram, A.; Ivanova, P.T.; Milne, S.B.; Summerville, J.B.; Brown, H.A.; Wangler, M.; Stern, M.; McNew, J.A. Peroxisomes Are Required for Lipid Metabolism and Muscle Function in Drosophila melanogaster. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Febvay, G. , Pageaux, J. & G., B. 1992. Lipid Composition of the Pea Aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum (Harris) (Hornoptera: Aphididae), Reared on Host Plant and on Artificial Media. Archives of Insect Biochemistry and Physiology, 21(103-118.

- Febvay, G.; Rahbé, Y.; Rynkiewicz, M.; Guillaud, J.; Bonnot, G. Fate of dietary sucrose and neosynthesis of amino acids in the pea aphid,Acyrthosiphon pisum, reared on different diets. J. Exp. Biol. 1999, 202, 2639–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogle, K.J.; Smith, A.R.; Satterfield, S.L.; Gutierrez, A.C.; Hertzler, J.I.; McCardell, C.S.; Shon, J.H.; Barile, Z.J.; Novak, M.O.; Palladino, M.J. Ketogenic and anaplerotic dietary modifications ameliorate seizure activity in Drosophila models of mitochondrial encephalomyopathy and glycolytic enzymopathy. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2019, 126, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, P. S. & Van Heusden, M. C. 1994. Triglyceride-rich lipophorin in Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol, 31(3), pp 435-41.

- Gäde, G. Glycogen Phosphorylase in the Fat Body of Two Cockroach Species, Periplaneta americana and Nauphoeta cinerea: Isolation, Partial Characterization of Three Forms and Activation by Hypertrehalosaemic Hormones. Z. Fur Naturforschung Sect. C-A J. Biosci. 1991, 46, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gade, G. 2009. Peptides of the adipokinetic hormone/red pigment-concentrating hormone family: a new take on biodiversity. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 1163(125-36.

- Gade, G. & Auerswald, L. 2002. Beetles' choice--proline for energy output: control by AKHs. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol, 132(1), pp 117-29.

- Gäde, G.; Auerswald, L. Mode of action of neuropeptides from the adipokinetic hormone family. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2003, 132, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gáliková, M.; Diesner, M.; Klepsatel, P.; Hehlert, P.; Xu, Y.; Bickmeyer, I.; Predel, R.; Kühnlein, R.P. Energy Homeostasis Control in Drosophila Adipokinetic Hormone Mutants. Genetics 2015, 201, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gáliková, M.; Klepsatel, P. Endocrine control of glycogen and triacylglycerol breakdown in the fly model. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 138, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, D.; Rubin, T.; Poidevin, M.; Maroni, B.; Le Rouzic, A.; Parvy, J.-P.; Montagne, J. Fatty Acid Synthase Cooperates with Glyoxalase 1 to Protect against Sugar Toxicity. PLOS Genet. 2015, 11, e1004995–e1004995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaviraghi, A.; Soares, J.B.C.; Mignaco, J.A.; Fontes, C.F.L.; Oliveira, M.F. Mitochondrial glycerol phosphate oxidation is modulated by adenylates through allosteric regulation of cytochrome c oxidase activity in mosquito flight muscle. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019, 114, 103226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A.C.; O’connor, M.B. Systemic Activin signaling independently regulates sugar homeostasis, cellular metabolism, and pH balance in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014, 111, 5729–5734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girard, C.; Jouanin, L. Molecular cloning of cDNAs encoding a range of digestive enzymes from a phytophagous beetle, Phaedon cochleariae. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1999, 29, 1129–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, J.T.; Betts, J.A. Dietary sugars, exercise and hepatic carbohydrate metabolism. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2018, 78, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govindaraj, L.; Gupta, T.; Esvaran, V.G.; Awasthi, A.K.; Ponnuvel, K.M. Genome-wide identification, characterization of sugar transporter genes in the silkworm Bombyx mori and role in Bombyx mori nucleopolyhedrovirus (BmNPV) infection. Gene 2016, 579, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grillo, L.; Pontes, E.; Gondim, K. Lipophorin interaction with the midgut of Rhodnius prolixus: characterization and changes in binding capacity. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2003, 33, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez, E.; Wiggins, D.; Fielding, B.; Gould, A.P. Specialized hepatocyte-like cells regulate Drosophila lipid metabolism. Nature 2006, 445, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haj-Ahmad, Y.; Hickey, D.A. A molecular explanation of frequency-dependent selection in Drosophila. Nature 1982, 299, 350–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasygar, K.; Deniz, O.; Liu, Y.; Gullmets, J.; Hynynen, R.; Ruhanen, H.; Kokki, K.; Käkelä, R.; Hietakangas, V. Coordinated control of adiposity and growth by anti-anabolic kinase ERK7. Embo Rep. 2020, 22, e49602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatting, M.; Tavares, C.D.; Sharabi, K.; Rines, A.K.; Puigserver, P. Insulin regulation of gluconeogenesis. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2017, 1411, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havula, E. & Hietakangas, V. 2018. Sugar sensing by ChREBP/Mondo-Mlx-new insight into downstream regulatory networks and integration of nutrient-derived signals. Curr Opin Cell Biol, 51(89-96.

- Havula, E. , Teesalu, M., Hyotylainen, T., Seppala, H., Hasygar, K., Auvinen, P., Oresic, M., Sandmann, T. & Hietakangas, V. 2013. Mondo/ChREBP-Mlx-regulated transcriptional network is essential for dietary sugar tolerance in Drosophila. PLoS Genet, 9(4), pp e1003438.

- Heier, C.; Klishch, S.; Stilbytska, O.; Semaniuk, U.; Lushchak, O. The Drosophila model to interrogate triacylglycerol biology. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2021, 1866, 158924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heier, C.; Kühnlein, R.P. Triacylglycerol Metabolism in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 2018, 210, 1163–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hines, W.; Smith, M. Some aspects of intermediary metabolism in the desert locust (Schistocerca gregaria Forskål). J. Insect Physiol. 1963, 9, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horecker, B. L. 2002. The pentose phosphate pathway. J Biol Chem, 277(50), pp 47965-71.

- Hori, K. Digestive carbohydrases in the salivary gland and midgut of several phytophagous bugs. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B: Comp. Biochem. 1975, 50, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, K.; Chen, W.; Zhu, F.; Li, P.W.-L.; Kapahi, P.; Bai, H. RiboTag translatomic profiling of Drosophila oenocytes under aging and induced oxidative stress. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, K.; Liu, Y.; Perrimon, N. Roles of Insect Oenocytes in Physiology and Their Relevance to Human Metabolic Diseases. Front. Insect Sci. 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inagaki, S.; Yamashita, O. Metabolic shift from lipogenesis to glycogenesis in the last instar larval fat body of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem. 1986, 16, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inigo, M.; Deja, S.; Burgess, S.C. Ins and Outs of the TCA Cycle: The Central Role of Anaplerosis. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2021, 41, 19–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, R.J.; Stenvinkel, P.; Andrews, P.; Sánchez-Lozada, L.G.; Nakagawa, T.; Gaucher, E.; Andres-Hernando, A.; Rodriguez-Iturbe, B.; Jimenez, C.R.; Garcia, G.; et al. Fructose metabolism as a common evolutionary pathway of survival associated with climate change, food shortage and droughts. J. Intern. Med. 2019, 287, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jutsum, A.; Goldsworthy, G. Fuels for flight in Locusta. J. Insect Physiol. 1976, 22, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanamori, Y.; Saito, A.; Hagiwara-Komoda, Y.; Tanaka, D.; Mitsumasu, K.; Kikuta, S.; Watanabe, M.; Cornette, R.; Kikawada, T.; Okuda, T. The trehalose transporter 1 gene sequence is conserved in insects and encodes proteins with different kinetic properties involved in trehalose import into peripheral tissues. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010, 40, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastari, T. & Turunen, S. 1977. Lipid utilization in Pieris brassicae reared on meridic and natural diest: implication for dietary improvement. Ent. exp. & appl., 22(71-80.

- Katewa, S.D.; Demontis, F.; Kolipinski, M.; Hubbard, A.; Gill, M.S.; Perrimon, N.; Melov, S.; Kapahi, P. Intramyocellular Fatty-Acid Metabolism Plays a Critical Role in Mediating Responses to Dietary Restriction in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Metab. 2012, 16, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, C.; Brown, M.R. Regulation of carbohydrate metabolism and flight performance by a hypertrehalosaemic hormone in the mosquito Anopheles gambiae. J. Insect Physiol. 2007, 54, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikuta, S.; Nakamura, Y.; Hattori, M.; Sato, R.; Kikawada, T.; Noda, H. Herbivory-induced glucose transporter gene expression in the brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015, 64, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Neufeld, T.P. Dietary sugar promotes systemic TOR activation in Drosophila through AKH-dependent selective secretion of Dilp3. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, B.; Li, S.; Liu, C.; Kim, S.J.; Sim, C. Suppression of glycogen synthase expression reduces glycogen and lipid storage during mosquito overwintering diapause. J. Insect Physiol. 2019, 120, 103971–103971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkton, S. D. & Tyler, S. K. 2021. American locust (Schistocerca americana) post-exercise lactate fate dataset. Data Brief, 37(107263.

- Ko, C.-W.; Qu, J.; Black, D.D.; Tso, P. Regulation of intestinal lipid metabolism: current concepts and relevance to disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokki, K.; Lamichane, N.; Nieminen, A.I.; Ruhanen, H.; Morikka, J.; Robciuc, M.; Rovenko, B.M.; Havula, E.; Käkelä, R.; Hietakangas, V. Metabolic gene regulation by Drosophila GATA transcription factor Grain. PLOS Genet. 2021, 17, e1009855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, N.; Wegner, A. Fructose Metabolism in Cancer. Cells 2020, 9, 2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Yu, X.; Feng, Q. Fat Body Biology in the Last Decade. Annu. Rev. Èntomol. 2019, 64, 315–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, K. Biological Characteristics and Energy Metabolism of Migrating Insects. Metabolites 2023, 13, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Lim, H.-Y. Drosophila Solute Carrier 5A5 Regulates Systemic Glucose Homeostasis by Mediating Glucose Absorption in the Midgut. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Pan, S.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y. Role of advanced glycation end products in diabetic vascular injury: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives. Eur. J. Med Res. 2023, 28, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K. , Dong, Y., Huang, Y., Rasgon, J. L. & Agre, P. 2013. Impact of trehalose transporter knockdown on Anopheles gambiae stress adaptation and susceptibility to Plasmodium falciparum infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 110(43), pp 17504-9.

- Lorenz, M.W. Oogenesis-flight syndrome in crickets: Age-dependent egg production, flight performance, and biochemical composition of the flight muscles in adult female Gryllus bimaculatus. J. Insect Physiol. 2007, 53, 819–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenz, M.W.; Anand, A.N. Changes in the biochemical composition of fat body stores during adult development of female crickets, Gryllus bimaculatus. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2004, 56, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, N.; Wang, L.; Sang, W.; Liu, C.-Z.; Qiu, B.-L. Effects of Endosymbiont Disruption on the Nutritional Dynamics of the Pea Aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum. Insects 2018, 9, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier, T.; Leibundgut, M.; Boehringer, D.; Ban, N. Structure and function of eukaryotic fatty acid synthases. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2010, 43, 373–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masson, S.W.C.; Hedges, C.P.; Devaux, J.B.L.; James, C.S.; Hickey, A.J.R. Mitochondrial glycerol 3-phosphate facilitates bumblebee pre-flight thermogenesis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, J.; Havula, E.; Suominen, E.; Teesalu, M.; Surakka, I.; Hynynen, R.; Kilpinen, H.; Väänänen, J.; Hovatta, I.; Käkelä, R.; et al. Mondo-Mlx Mediates Organismal Sugar Sensing through the Gli-Similar Transcription Factor Sugarbabe. Cell Rep. 2015, 13, 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattila, J.; Hietakangas, V. Regulation of Carbohydrate Energy Metabolism in Drosophila melanogaster. . 2017, 207, 1231–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michitsch, J.; Steele, J.E. Carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in cockroach (Periplaneta americana) fat body are both activated by low and similar concentrations of Peram-AKH II. Peptides 2008, 29, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagne, J. & Wicker-Thomas, C. 2020. Drosophila pheromone production. In: Blomquist G. & Vogt R. G. (eds.) Insect Pheromone Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. Elsevier Academic Press, London.

- Mor, I.; Cheung, E.C.; Vousden, K.H. Control of Glycolysis through Regulation of PFK1: Old Friends and Recent Additions. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2011, 76, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraes, K.C.M.; Montagne, J. Drosophila melanogaster: A Powerful Tiny Animal Model for the Study of Metabolic Hepatic Diseases. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraru, A.; Wiederstein, J.; Pfaff, D.; Fleming, T.; Miller, A.K.; Nawroth, P.; Teleman, A.A. Elevated Levels of the Reactive Metabolite Methylglyoxal Recapitulate Progression of Type 2 Diabetes. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 926–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, N.R.; Cardoso, C.; Dias, R.O.; Ferreira, C.; Terra, W.R. A physiologically-oriented transcriptomic analysis of the midgut of Tenebrio molitor. J. Insect Physiol. 2017, 99, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mráček, T.; Drahota, Z.; Houštěk, J. The function and the role of the mitochondrial glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in mammalian tissues. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Bioenerg. 2013, 1827, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, T.A.; Wyatt, G. The Enzymes of Glycogen and Trehalose Synthesis in Silk Moth Fat Body. J. Biol. Chem. 1965, 240, 1500–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musselman, L.P.; Fink, J.L.; Narzinski, K.; Ramachandran, P.V.; Hathiramani, S.S.; Cagan, R.L.; Baranski, T.J. A high-sugar diet produces obesity and insulin resistance in wild-type Drosophila. Dis. Models Mech. 2011, 4, 842–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musselman, L.P.; Fink, J.L.; Ramachandran, P.V.; Patterson, B.W.; Okunade, A.L.; Maier, E.; Brent, M.R.; Turk, J.; Baranski, T.J. Role of Fat Body Lipogenesis in Protection against the Effects of Caloric Overload in Drosophila. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 8028–8042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustard, J.A.; Alvarez, V.; Barocio, S.; Mathews, J.; Stoker, A.; Malik, K. Nutritional value and taste play different roles in learning and memory in the honey bee (Apis mellifera). J. Insect Physiol. 2018, 107, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, J.; Musselman, L.P.; Pendse, J.; Baranski, T.J.; Bodmer, R.; Ocorr, K.; Cagan, R. A Drosophila Model of High Sugar Diet-Induced Cardiomyopathy. PLOS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishihara, S. Functional analysis of glycosylation using Drosophila melanogaster. Glycoconj. J. 2019, 37, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oguri, E.; Steele, J.E. A novel function of cockroach (Periplaneta americana) hypertrehalosemic hormone: translocation of lipid from hemolymph to fat body. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2003, 132, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olademehin, O.P.; Liu, C.; Rimal, B.; Adegboyega, N.F.; Chen, F.; Sim, C.; Kim, S.J. Dsi-RNA knockdown of genes regulated by Foxo reduces glycogen and lipid accumulations in diapausing Culex pipiens. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olzmann, J.A.; Carvalho, P. Dynamics and functions of lipid droplets. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palm, W. , Sampaio, J. L., Brankatschk, M., Carvalho, M., Mahmoud, A., Shevchenko, A. & Eaton, S. 2012. Lipoproteins in Drosophila melanogaster--assembly, function, and influence on tissue lipid composition. PLoS Genet, 8(7), pp e1002828.

- Parvy, J. P. , Napal, L., Rubin, T., Poidevin, M., Perrin, L., Wicker-Thomas, C. & Montagne, J. 2012. Drosophila melanogaster Acetyl-CoA-carboxylase sustains a fatty acid-dependent remote signal to waterproof the respiratory system. PLoS Genet, 8(8), pp e1002925.

- Pasco, M.Y.; Leopold, P. High sugar-induced insulin resistance in Drosophila relies on the lipocalin Neural Lazarillo. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, P.; Abate, N. Role of Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue in the Pathogenesis of Insulin Resistance. J. Obes. 2013, 2013, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick, J.W.; Botha, F.C.; Birch, R.G. Metabolic engineering of sugars and simple sugar derivatives in plants. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2012, 11, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, X.; Bai, T.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, S.; Fan, Y.; Liu, T. Acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase modulates lipogenesis and sugar homeostasis in Blattella germanica. Insect Sci. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, J. E. & Wells, M. A. 2002. Triacylglycerol-rich lipophorins are found in the dipteran infraorder Culicomorpha, not just in mosquitoes. J Insect Sci, 2(15.

- Pimentel, A.C.; Barroso, I.G.; Ferreira, J.M.; Dias, R.O.; Ferreira, C.; Terra, W.R. Molecular machinery of starch digestion and glucose absorption along the midgut of Musca domestica. J. Insect Physiol. 2018, 109, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, D.R.; Wilkinson, H.S.; Gatehouse, J.A. Functional expression and characterisation of a gut facilitative glucose transporter, NlHT1, from the phloem-feeding insect Nilaparvata lugens (rice brown planthopper). Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2007, 37, 1138–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbani, N.; Thornalley, P.J. Methylglyoxal, glyoxalase 1 and the dicarbonyl proteome. Amino Acids 2010, 42, 1133–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabbani, N. & Thornalley, P. J. 2013. Glyoxalase in diabetes, obesity and related disorders. Semin Cell Dev Biol, 22(3), pp 309-17.

- Radimerski, T.; Montagne, J.; Hemmings-Mieszczak, M.; Thomas, G. Lethality of Drosophila lacking TSC tumor suppressor function rescued by reducing dS6K signaling. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 2627–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahbé, Y.; Delobel, B.; Febvay, G.; Chantegrel, B. Aphid-specific triglycerides in symbiotic and aposymbiotic Acyrthosiphon pisum. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1994, 24, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajapakse, S.; Qu, D.; Ahmed, A.S.; Rickers-Haunerland, J.; Haunerland, N.H. Effects of FABP knockdown on flight performance of the desert locust, Schistocerca gregaria. J. Exp. Biol. 2019, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ransom-Jones, E.; Jones, D.L.; McCarthy, A.J.; McDonald, J.E. The Fibrobacteres: an Important Phylum of Cellulose-Degrading Bacteria. Microb. Ecol. 2012, 63, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, T.; Van Gilst, M.R.; Hariharan, I.K. A Buoyancy-Based Screen of Drosophila Larvae for Fat-Storage Mutants Reveals a Role for Sir2 in Coupling Fat Storage to Nutrient Availability. PLOS Genet. 2010, 6, e1001206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, P.; Ourabah, S.; Montagne, J.; Burnol, A.-F.; Postic, C.; Guilmeau, S. MondoA/ChREBP: The usual suspects of transcriptional glucose sensing; Implication in pathophysiology. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2017, 70, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roach, P.J.; Depaoli-Roach, A.A.; Hurley, T.D.; Tagliabracci, V.S. Glycogen and its metabolism: some new developments and old themes. Biochem. J. 2012, 441, 763–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, N.; Goldsworthy, G. Adipokinetic hormone and the regulation of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in a working flight muscle preparation. J. Insect Physiol. 1977, 23, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeder, T. TYRAMINE AND OCTOPAMINE: Ruling Behavior and Metabolism. Annu. Rev. Èntomol. 2005, 50, 447–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovenko, B.M.; Perkhulyn, N.V.; Gospodaryov, D.V.; Sanz, A.; Lushchak, O.V.; Lushchak, V.I. High consumption of fructose rather than glucose promotes a diet-induced obese phenotype in Drosophila melanogaster. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A: Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2015, 180, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saggerson, D. Malonyl-CoA, a Key Signaling Molecule in Mammalian Cells. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2008, 28, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahaka, M.; Amara, S.; Wattanakul, J.; Gedi, M.A.; Aldai, N.; Parsiegla, G.; Lecomte, J.; Christeller, J.T.; Gray, D.; Gontero, B.; et al. The digestion of galactolipids and its ubiquitous function in Nature for the uptake of the essential α-linolenic acid. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 6710–6744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sano, H.; Nakamura, A.; Yamane, M.; Niwa, H.; Nishimura, T.; Araki, K.; Takemoto, K.; Ishiguro, K.-I.; Aoki, H.; Kato, Y.; et al. The polyol pathway is an evolutionarily conserved system for sensing glucose uptake. PLOS Biol. 2022, 20, e3001678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxton, R.A.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell 2017, 168, 960–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, E.; Thorat, L.J.; Nath, B.B.; Gaikwad, S.M. Insect trehalase: Physiological significance and potential applications. Glycobiology 2014, 25, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Oliveira, G.; De Paula, I.F.; Medina, J.M.; Alves-Bezerra, M.; Gondim, K.C. Insulin receptor deficiency reduces lipid synthesis and reproductive function in the insect Rhodnius prolixus. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2021, 1866, 158851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Witkowski, A.; Joshi, A.K. Structural and functional organization of the animal fatty acid synthase. Prog. Lipid Res. 2003, 42, 289–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, J.B.R.C.; Gaviraghi, A.; Oliveira, M.F. Mitochondrial Physiology in the Major Arbovirus Vector Aedes aegypti: Substrate Preferences and Sexual Differences Define Respiratory Capacity and Superoxide Production. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0120600–e0120600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stec, N.; Saleem, A.; Darveau, C.-A. Proline as a Sparker Metabolite of Oxidative Metabolism during the Flight of the Bumblebee, Bombus impatiens. Metabolites 2021, 11, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, J. Glycogen phosphorylase in insects. Insect Biochem. 1982, 12, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storelli, G.; Nam, H.-J.; Simcox, J.; Villanueva, C.J.; Thummel, C.S. Drosophila HNF4 Directs a Switch in Lipid Metabolism that Supports the Transition to Adulthood. Dev. Cell 2018, 48, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S. , Zhang, X., Jian, C., Huang, B., Peng, X., Vreysen, M. J. B. & Chen, M. 2022. Effects of Adult Feeding Treatments on Longevity, Fecundity, Flight Ability, and Energy Metabolism Enzymes of Grapholita molesta Moths. Insects, 13(8), pp.

- Suarez, R.K.; Darveau, C.-A.; Welch, K.C.; O'Brien, D.M.; Roubik, D.W.; Hochachka, P.W. Energy metabolism in orchid bee flight muscles: carbohydrate fuels all. J. Exp. Biol. 2005, 208, 3573–3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szyszka, P.; Galizia, C.G. The Role of the Sucrose-Responsive IR60b Neuron for Drosophila melanogaster: A Hypothesis. Chem. Senses 2018, 43, 311–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskinen, M.-R.; Packard, C.J.; Borén, J. Dietary Fructose and the Metabolic Syndrome. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terra, W.R.; Ferreira, C. Insect digestive enzymes: properties, compartmentalization and function. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B: Comp. Biochem. 1994, 109, 1–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terra, W. R. & Ferreira, C. 2012. Biochemistry and molecular biology of digestion. In: Gilbert, L. I. (ed.) Insect Molecular Biology and Biochemistry.. Academic Press/Elsevier, London.

- Thompson, S. N. 2003. Trehalose – The Insect ‘Blood’ Sugar. Advances in insect physiology, 31(.

- Thornalley, P.J. The glyoxalase system in health and disease. Mol. Asp. Med. 1993, 14, 287–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tietz, A. Fat synthesis in cell-free preparations of the locust fat-body. J. Lipid Res. 1961, 2, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toprak, U. The Role of Peptide Hormones in Insect Lipid Metabolism. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Towarnicki, S.G.; Ballard, J.W.O. Towards understanding the evolutionary dynamics of mtDNA. Mitochondrial DNA Part A 2020, 31, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turturro, A.; Shafiq, S.A. Quantitative Morphological Analysis of Age-Related Changes in Flight Muscle of Musca Domestica L. J. Gerontol. 1979, 34, 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turunen, S. Absorption and transport of dietary lipid in Pieris brassicae. J. Insect Physiol. 1975, 21, 1521–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turunen, S. Metabolic pathways in the midgut epithelium of Pieris brassicae during carbohydrate and lipid assimilation. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1993, 23, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turunen, S.; Kastari, T. Digestion and absorption of lecithin in larvae of the cabbage butterfly, Pieris brassicae. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A: Physiol. 1979, 62, 933–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Horst, D. J. , van Doorn, J. M., Passier, P. C., Vork, M. M. & Glatz, J. F. 1993. Role of fatty acid-binding protein in lipid metabolism of insect flight muscle. Mol Cell Biochem, 123(1-2), pp 145-52.

- Varghese, J. , Lim, S. F. & Cohen, S. M. 2010. Drosophila miR-14 regulates insulin production and metabolism through its target, sugarbabe. Genes Dev, 24(24), pp 2748-53.

- Veenstra, J.A. Simulation of the activation of fat body glycogen phosphorylase and trehalose synthesis by peptide hormones in the American cockroach. Biosystems 1989, 23, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, J. Glucose transporter GLUT1 influences Plasmodium berghei infection in Anopheles stephensi. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Campbell, J.B.; Kaftanoglu, O.; Page, R.E.; Amdam, G.V.; Harrison, J.F. Larval starvation improves metabolic response to adult starvation in honey bees (Apis mellifera L.). J. Exp. Biol. 2016, 219, 960–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, H.; Noda, H.; Tokuda, G.; Lo, N. A cellulase gene of termite origin. Nature 1998, 394, 330–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, H.; Tokuda, G. Cellulolytic Systems in Insects. Annu. Rev. Èntomol. 2010, 55, 609–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegener, G. Flying insects: model systems in exercise physiology. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 1996, 52, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiglein, A.; Gerstner, F.; Mancini, N.; Schleyer, M.; Gerber, B. One-trial learning in larval Drosophila. Learn. Mem. 2019, 26, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wicker-Thomas, C.; Garrido, D.; Bontonou, G.; Napal, L.; Mazuras, N.; Denis, B.; Rubin, T.; Parvy, J.-P.; Montagne, J. Flexible origin of hydrocarbon/pheromone precursors in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Lipid Res. 2015, 56, 2094–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, J.D.; Oppert, B.; Oppert, C.; Klingeman, W.E.; Jurat-Fuentes, J.L. Identification, cloning, and expression of a GHF9 cellulase from Tribolium castaneum (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). J. Insect Physiol. 2011, 57, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wone, B. W. M. , Kinchen, J. M., Kaup, E. R. & Wone, B. 2018. A procession of metabolic alterations accompanying muscle senescence in Manduca sexta. Sci Rep, 8(1), pp 1006.

- Wood, J.G.; Schwer, B.; Wickremesinghe, P.C.; Hartnett, D.A.; Burhenn, L.; Garcia, M.; Li, M.; Verdin, E.; Helfand, S.L. Sirt4 is a mitochondrial regulator of metabolism and lifespan in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018, 115, 1564–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, E.M.; Hirayama, B.A.; Loo, D.F. Active sugar transport in health and disease. J. Intern. Med. 2007, 261, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Brown, M.R. SIGNALING AND FUNCTION OF INSULIN-LIKE PEPTIDES IN INSECTS. Annu. Rev. Èntomol. 2006, 51, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, G. R. & Kale, G. F. 1957. The chemistry of insect hemolymph. II. Trehalose and other carbohydrates. J Gen Physiol, 40(6), pp 833-47.

- Yamada, T.; Habara, O.; Kubo, H.; Nishimura, T. Fat body glycogen serves as a metabolic safeguard for the maintenance of sugar levels in Drosophila. Development 2018, 145, dev–158865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Habara, O.; Yoshii, Y.; Matsushita, R.; Kubo, H.; Nojima, Y.; Nishimura, T. Role of glycogen in development and adult fitness in Drosophila. Development 2019, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H. J. , Cui, M. Y., Zhao, X. H., Zhang, C. Y., Hu, Y. S. & Fan, D. 2023. Trehalose-6-phosphate synthase regulates chitin synthesis in Mythimna separata. Front Physiol, 14(1109661.

- Yang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, J.; Fan, Z.; Gong, S.-T.; Tang, H.; Pan, L. Sugar Alcohols of Polyol Pathway Serve as Alarmins to Mediate Local-Systemic Innate Immune Communication in Drosophila. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 26, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.-C.; Jiang, C.-J.; An, C.-J.; Zhang, Q.-W.; Zhao, Z.-W. Variations in Fuel Use in the Flight Muscles of Wing-Dimorphic Gryllus Firmus and Implications for Morph-Specific Dispersal. Environ. Èntomol. 2011, 40, 1566–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yuan, D.; Xie, J.; Lei, Y.; Li, J.; Fang, G.; Tian, L.; Liu, J.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, M.; et al. Evolution of the Cholesterol Biosynthesis Pathway in Animals. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2019, 36, 2548–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Li, X.; Shi, X.; Karpac, J. Diet-MEF2 interactions shape lipid droplet diversification in muscle to influence Drosophila lifespan. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.; Pennington, J.E.; Wells, M.A. Utilization of pre-existing energy stores of female Aedes aegypti mosquitoes during the first gonotrophic cycle. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004, 34, 919–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.J.; Fukumura, K.; Nagata, S. Effects of adipokinetic hormone and its related peptide on maintaining hemolymph carbohydrate and lipid levels in the two-spotted cricket, Gryllus bimaculatus. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2018, 82, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, R.; Eckart, K.; Law, J.H. Adipokinetic hormone controls lipid metabolism in adults and carbohydrate metabolism in larvae of Manduca sexta. Peptides 1990, 11, 1037–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, R.; Schulz, M. Regulation of lipid metabolism during flight in Manduca sexta. J. Insect Physiol. 1986, 32, 903–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinke, I.; Schütz, C.S.; Katzenberger, J.D.; Bauer, M.; Pankratz, M.J. Nutrient control of gene expression in Drosophila: microarray analysis of starvation and sugar-dependent response. EMBO J. 2002, 21, 6162–6173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Carbohydrate | Type | Main dietary source |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose | monosaccharide C6H12O6 | universal |

| Fructose | monosaccharide C6H12O6 | fruits |

| Galactose | monosaccharide C6H12O6 | milk, honey, plant galactolipids |

| Sucrose | 1 glucose + 1 fructose | plant roots, fruits and sap |

| Maltose | 2 glucose | germinating seeds |

| Trehalose | 2 glucose | insect haemolymph |

| Cellobiose | 2 glucose | cellulose digestion |

| Raffinose | 1 galactose + 1 glucose + 1 fructose | plant seeds |

| Melezitose | 2 glucose + 1 fructose | plant sap, honey |

| Glycogen | branched glucose polymer | animal stores |

| Starch | branched glucose polymer | plant stores |

| Inulin | branched fructose polymer | plant stores |

| Cellulose | linear glucose polymer | plant cell walls |

| Hemicellulose | branched monosaccharide polymer | plant cell walls |

| Pectin | galacturonic acid polymer | plant cell walls |

| Glycolipid | monosaccharide + diacylglycerol | cell membranes |

| Galactolipid | galactose + diacylglycerol | thylakoid membranes |

| Insect species | Flight muscle metabolism requirements | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| A. aegypti | proline, pyruvate and G3P | (Gaviraghi et al., 2019) |

| A. gambia | AKH-I dependent haemolymph trehalose | (Kaufmann and Brown, 2008) |

| Bombus impatiens | proline at flight onset shift to carbohydrate | (Stec et al., 2021) |

| B. terrestris | G3P shuttle to pre-warm flight muscle | (Masson et al., 2017) |

| D. melanogaster | Glycolytic metabolites AKH-dependent lipid metabolism Peroxisome-dependent lipid metabolism Carbohydrate |

(Eanes et al., 2006) (Katewa et al., 2012) (Faust et al., 2014) (Zhao et al., 2020) |

| Decapotoma lunata | Haemolymph carbohydrate | (Auerswald and G, 1995) |

| G. molesta | Carbohydrate | (Su et al., 2022) |

| G. firmus | Fat body glycogen, haemolymph trehalose | (Zhang et al., 2011) |

| L. migratoria | Trehalose and lipids Lipids, high FABP levels in flight muscles |

(Robinson and Goldsworthy, 1977) (van der Horst et al., 1993) |

| M. sexta | Haemolymph lipids FA oxidation shifts to glycolysis with aging |

(Ziegler and Schulz, 1986) (Wone et al., 2018) |

| Pachnoda sinuata | Proline and haemolymph carbohydrates | (Auerswald et al., 1998) |

| P. megistus | Carbohydrate first, shift to lipids | (Canavoso et al., 2003) |

| P.americana | Glycogen High expression of glycogen phosphorylase |

(Downer and Matthews, 1976) (Steele, 1982) |

| R. prolixus | Lipids | (Braz et al., 2023) |

| S. gregaria | Carbohydrate first, shift to lipids | (Rajapakse et al., 2019) |

| Orchid bees | Carbohydrate | (Suarez et al., 2005) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).