Submitted:

29 July 2024

Posted:

30 July 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

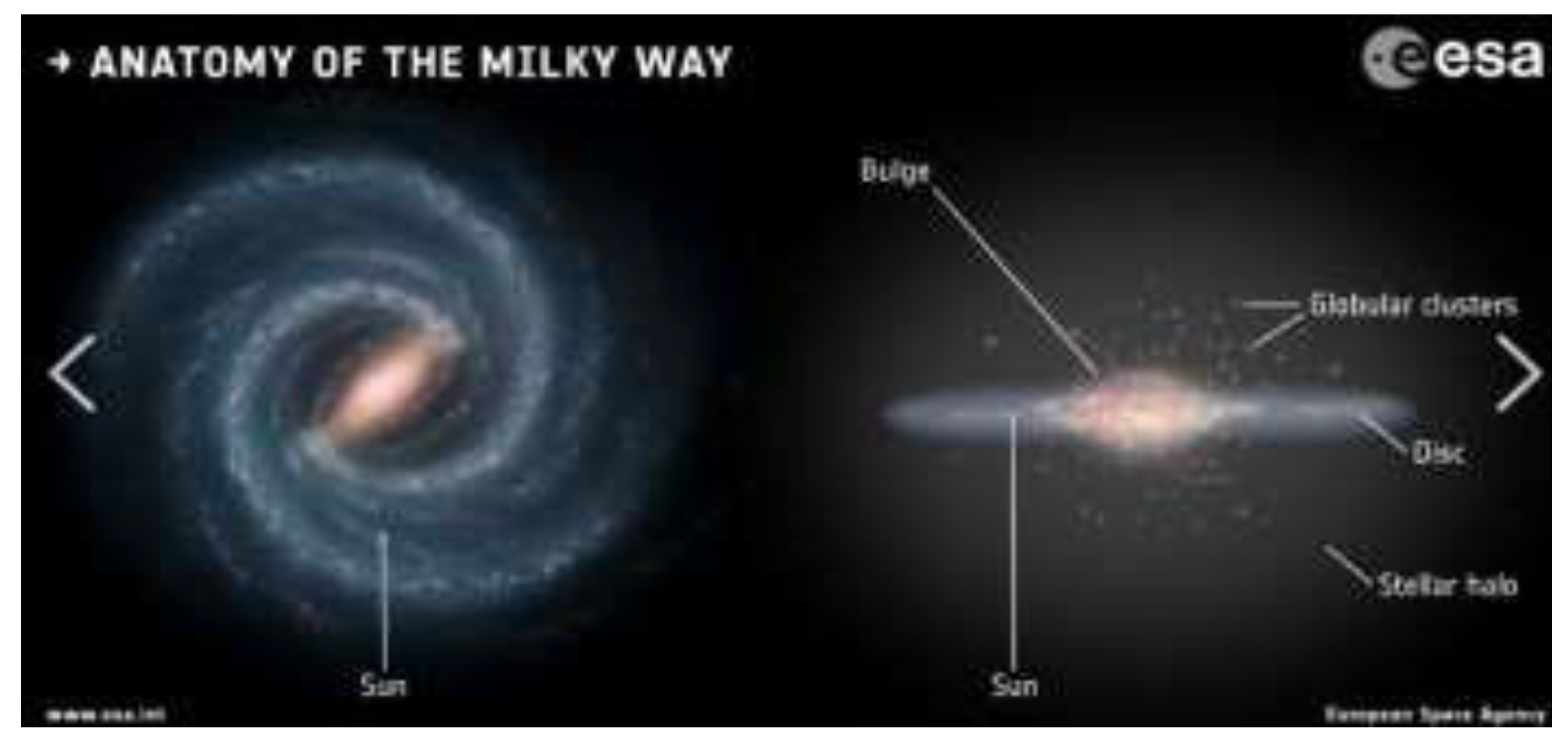

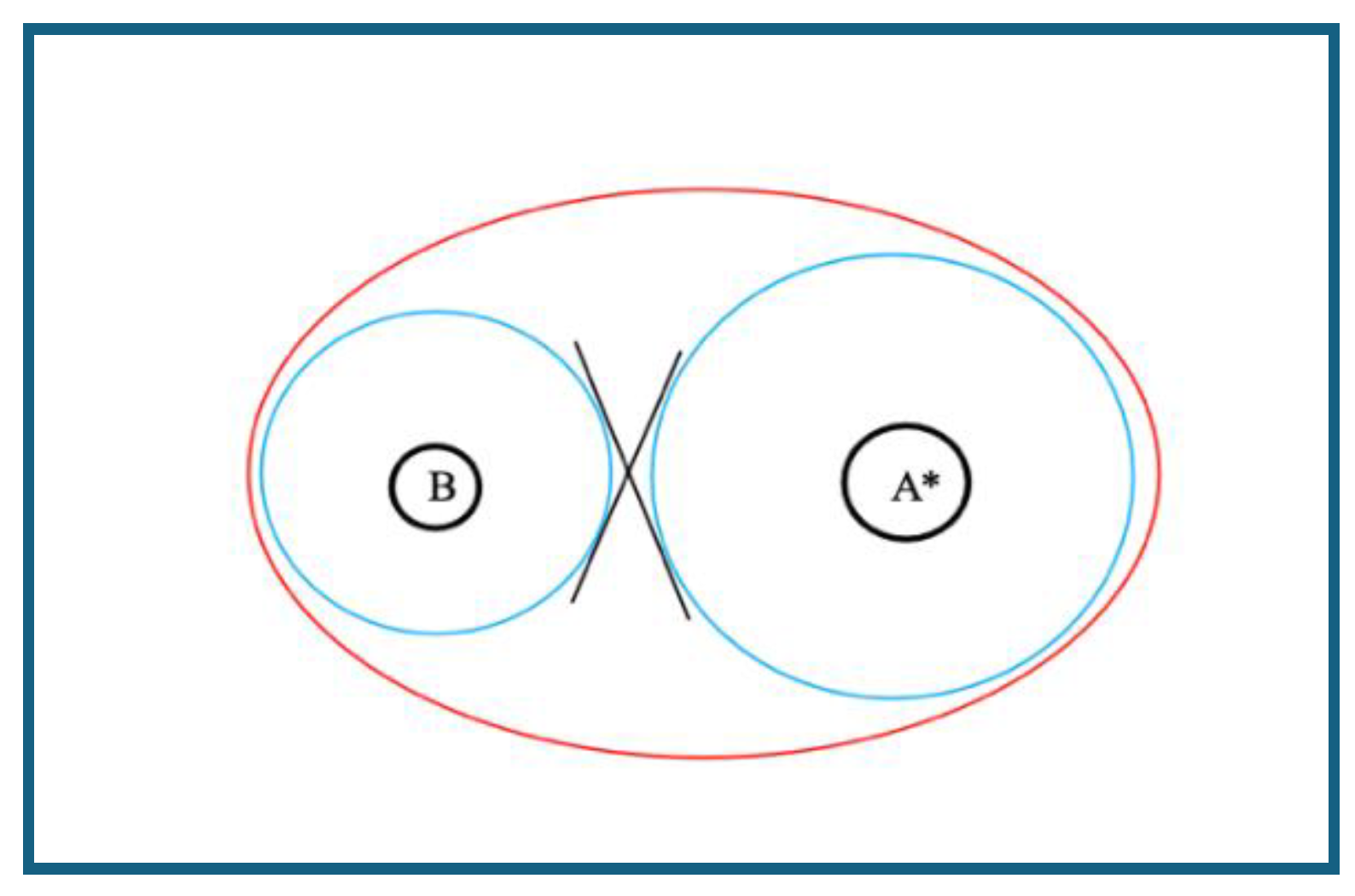

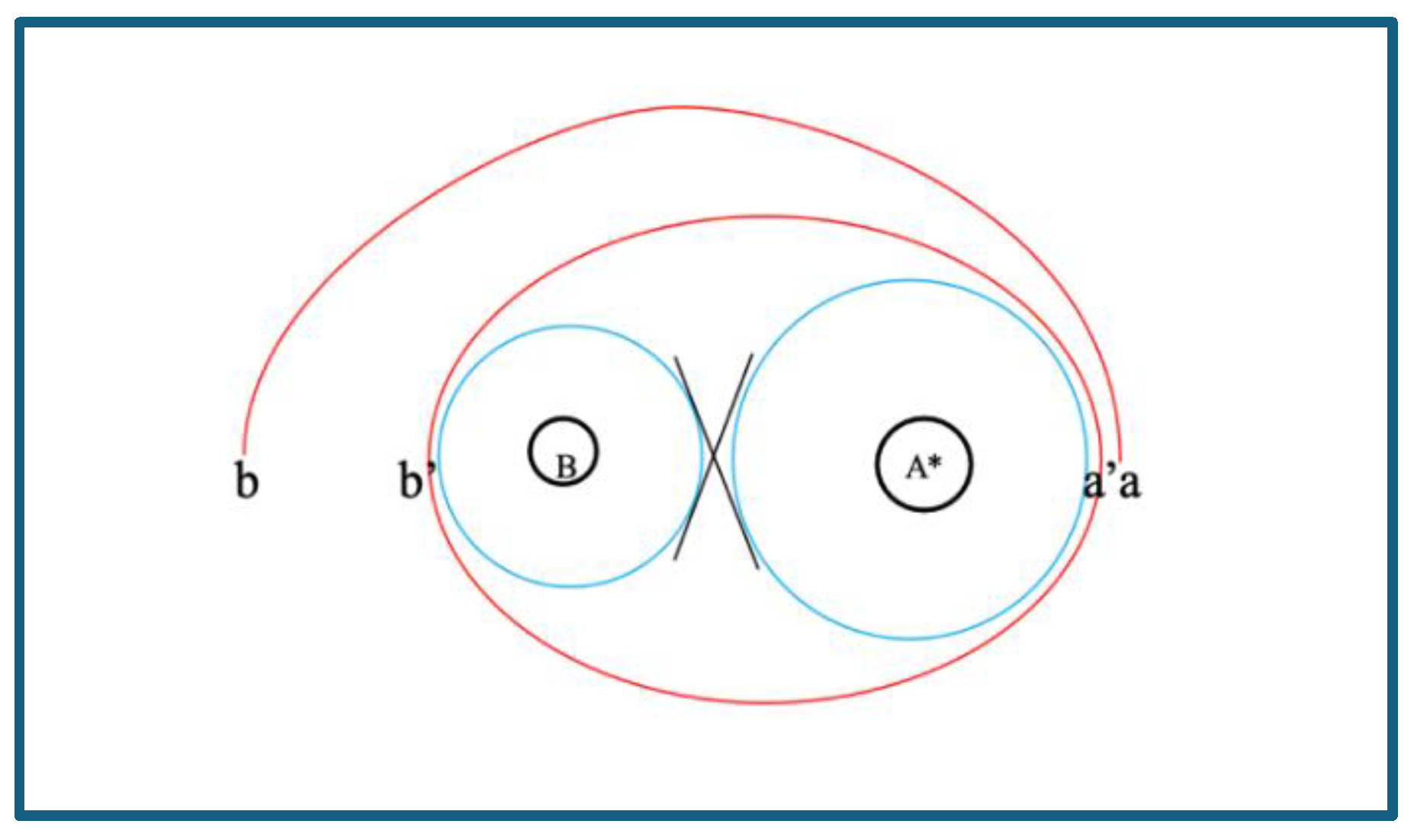

2. The Peanut Shape with the “x-Shaped Structure” or Boxy Core of the Bar: the Possible Another Supermassive Black Hole in the Bar of the Milky Way

2.1. The Possible Structure of the Bar of the Milky Way

2.2. The Galactic Spiral Arms and Hill Sphere

2.3. The Mass and Position of the Black Hole B

3. Discussions

3.1. The Complicated Orbits in the Bar: The Strong Evidence for the Possible Another Supermassive Black Hole

3.2. The Supermassive Black Holes Binaries in a Galaxy

3.3. The Newtonian Theory of Orbit and the Galactic Dynamics

4. Conclusion

References

- Oort, J.H.; Kerr, F.J.; Westerhout, G. The galactic system as a spiral nebula (Council Note). MNRAS 1958, 118, 379. [Google Scholar]

- Georgelin, Y.M.; Georgelin, Y.P. The spiral structure of our Galaxy determined from H II regions. A&A 1976, 49, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Oort, J.H.; Rougoor, G.W. The interstellar gas in the central part of the galaxy. AJ 1959, 64, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rougoor, G.W.; Oort, J.H. Distribution and Motion of Interstellar Hydrogen in the Galactic System with Particular Reference to the Region Within 3 Kiloparsecs of the Center. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science 1960, 46, 1. [Google Scholar]

- de Vaucouleurs, G. 1964, in IAU Symposium, Vol. 20, The Galaxy and the Magellanic Clouds, ed. F. J. Kerr, 195.

- McWilliam, A.; Zoccali, M. Two Red Clumps and the X-shaped Milky Way Bulge. ApJ 2010, 724, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-Y.; Shen, J. Mapping the Three-Dimensional “X-Shaped Structure” in Models of the Galactic Bulg. ApJL 2015, 815, L20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegg, C.; Gerhard, O. Mapping the three-dimensional density of the Galactic bulge with VVV red clump stars. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2013, 435, 1874–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattia, M.C.; Gerhard, O.; Portail, M.; Vasiliev, E.; Clarke, J. The stellar mass distribution of the Milky Way’s bar: an analytical model. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters 2022, 514, L1–L5. [Google Scholar]

- Skokos, C.; Patsis, P.A.; Athanassoula, E. Orbital dynamics of three-dimensional bars – I. The backbone of three-dimensional bars. A fiducial case. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2002, 333, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genzel, R.; Eisenhauer, F.; Gillessen, S. The Galactic Center Massive Black Hole and Nuclear Star Cluster. Reviews of Modern Physics 2010, 82.4, 3121–3195. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Zheng, X. The bar and spiral arms in the Milky Way: structure and kinematics. RAA 2020, 20, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, D.; Ekers, R.D. Tracing Black Hole Mergers Through Radio Lobe Morphology. Science 2002, 297, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, H. R.; et al. The Abundance of X-Shaped Radio Sources: Implications for the Gravitational Wave Background. ApJ 2015, 810, L6. [Google Scholar]

- David, H. R.; et al. The Abundance of X-Shaped Radio Sources I. VLA Survey of 52 Sources With Off-Axis Distortions. ApJS 2015, 220, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, K.; et al. Constraining the Orbit of the Supermassive Black Hole Binary 0402+379. ApJ 2017, 843, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y. Observational signatures of close binaries of supermassive black holes in active galactic nuclei. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 20, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komossa, S.; et al. Supermassive Binary Black Holes and the Case of OJ 287. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.12901. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, S.; et al. The Unanticipated Phenomenology of the Blazar PKS 2131–021: A Unique Supermassive Black Hole Binary Candidate. ApJL 2022, 926, L35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, J.L.; Traianou, E.; et al. Probing the innermost regions of AGN jets their magnetic fields with Radio Astron, V. Space and ground millimeter-VLBI imaging of OJ 287. APJ 2022, 924, 122. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, W.; et al. Observational Evidence of a Centi-parsec Supermassive Black Hole Binary Existing in the Nearby Galaxy M81. ApJ 2023, 959, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magallanes-Guijón, G.; Mendoza, S. A Supermassive Binary Black Hole Candidate in Mrk 501. Galaxies 2024, 2, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foord, A.; Cappelluti, N.; Liu, T.; Volonteri, M.; et al. Tracking Supermassive Black Hole Mergers from kpc to sub-pc Scales with AXIS. Universe 2024, 10, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busetti, F.; Beust, H.; Harley, C. Stability of planets in triple star systems. A&A 2018, 619, A91. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.; et al. Assembling the Milky Way Bulge from Globular Clusters: Evidence from the Double Red Clump. ApJL 2018, 862, L8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwanek, P.; et al. A Three-dimensional Map of the Milky Way Using 66,000 Mira Variable Stars. ApJS 2023, 264, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Corredoira, M. Absence of an X-shaped Structure in the Milky Way Bulge Using Mira Variable Stars. ApJ 2017, 836, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, A. A.; Guillen, L. J. Z.; Yepez, M. A.; Fierro, I. H. B.; et al. The variable stars in the field of the bulge cluster NGC 6558. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2024, 532, 2159–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; et al. The Circular Velocity Curve of the Milky Way from 5–25 kpc Using Luminous Red Giant Branch Stars. ApJ 2023, 946, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Hammer, F.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; et al. Detection of the Keplerian decline in the Milky Way rotation curve. A&A 2023, 678, A208. [Google Scholar]

- Eilers, A.; Hogg, D.W.; Rix, H.; Ness, M.K. The Circular Velocity Curve of the Milky Way from 5 to 25 kpc. ApJ 2019, 871, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, D.; et al. The Bulge Radial Velocity Assay (BRAVA). I. Sample Selection and a Rotation Curve. ApJ 2008, 688, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunder, A.; et al. The bulge radial velocity assay (BRAVA). II. Complete sample and data release. AJ 2012, 143, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peißker, F.; Eckart, A.; Parsa, M. S62 on a 9.9 yr Orbit around SgrA*. ApJ 2020, 889, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peißker, F.; Eckart, A.; Zajaček, M.; Britzen, S. Observation of S4716- A star with a 4 year orbit around Sgr A*. ApJ 2022, 933, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peißker, F.; Eckart, A.; Zajaček, M.; Britzen, S.; Ali, B.; Parsa, M. S62 and S4711: Indications of a Population of Faint Fast-moving Stars inside the S2 Orbit—S4711 on a 7.6yr Orbit around Sgr A*. ApJ 2020, 899, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peißker, F.; Eckart, A.; Ali, B. Observation of the Apoapsis of S62 in 2019 with NIRC2 and SINFONI. APJ 2021, 918, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GRAVITY Collaboration; et al. Deep images of the Galactic center with GRAVITY. A&A 2022, 657, A82. [Google Scholar]

- GRAVITY Collaboration; et al. Mass distribution in the Galactic Center based on interferometric astrometry of multiple stellar orbits. A&A 2022, 657, L12. [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama, S.; et al. A Distinct Structure inside the Galactic Bar. ApJ 2005, 621, L105. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.; Ho, L.C. The Statistical Properties of Spiral Arms in Nearby Disk Galaxies. ApJ 2020, 900, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, D.; Chattopadhyay, T. Role of galactic bars in the formation of spiral arms: a study through orbital and escape dynamics—I. Celest Mech Dyn Astr 2021, 133, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblad, P.A. B.; Kristen, H. Hydrodynamical simulations of the barred spiral galaxy NGC 1300. Dynamical interpretation of observations. Astronomy and Astrophysics 1996, 313, 733–749. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, Y.; Lee, M. I.; et al. Observational evidence for bar formation in disk galaxies via cluster–cluster interaction. Nat Astron 2019, 3, 844–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshan, M.; Ghafourian, N.; Kashfi, T.; Banik, I.; Haslbauer, M.; et al. Fast galaxy bars continue to challenge standard cosmology. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2021, 508, 926–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, D.; Chattopadhyay, T. Role of galactic bars in the formation of spiral arms: a study through orbital and escape dynamics—I. Celest Mech Dyn Astr 2021, 133, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).