Submitted:

21 June 2024

Posted:

24 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

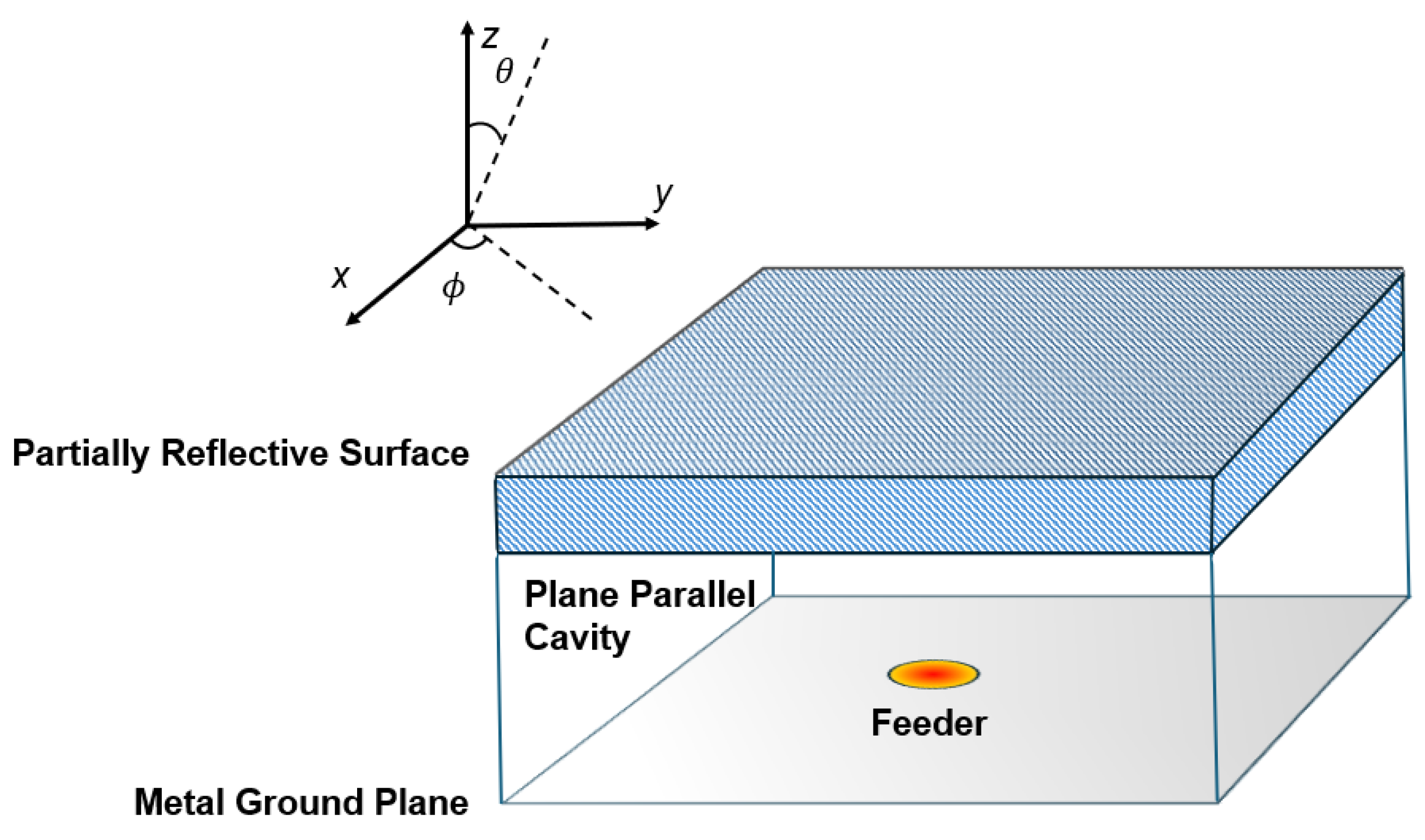

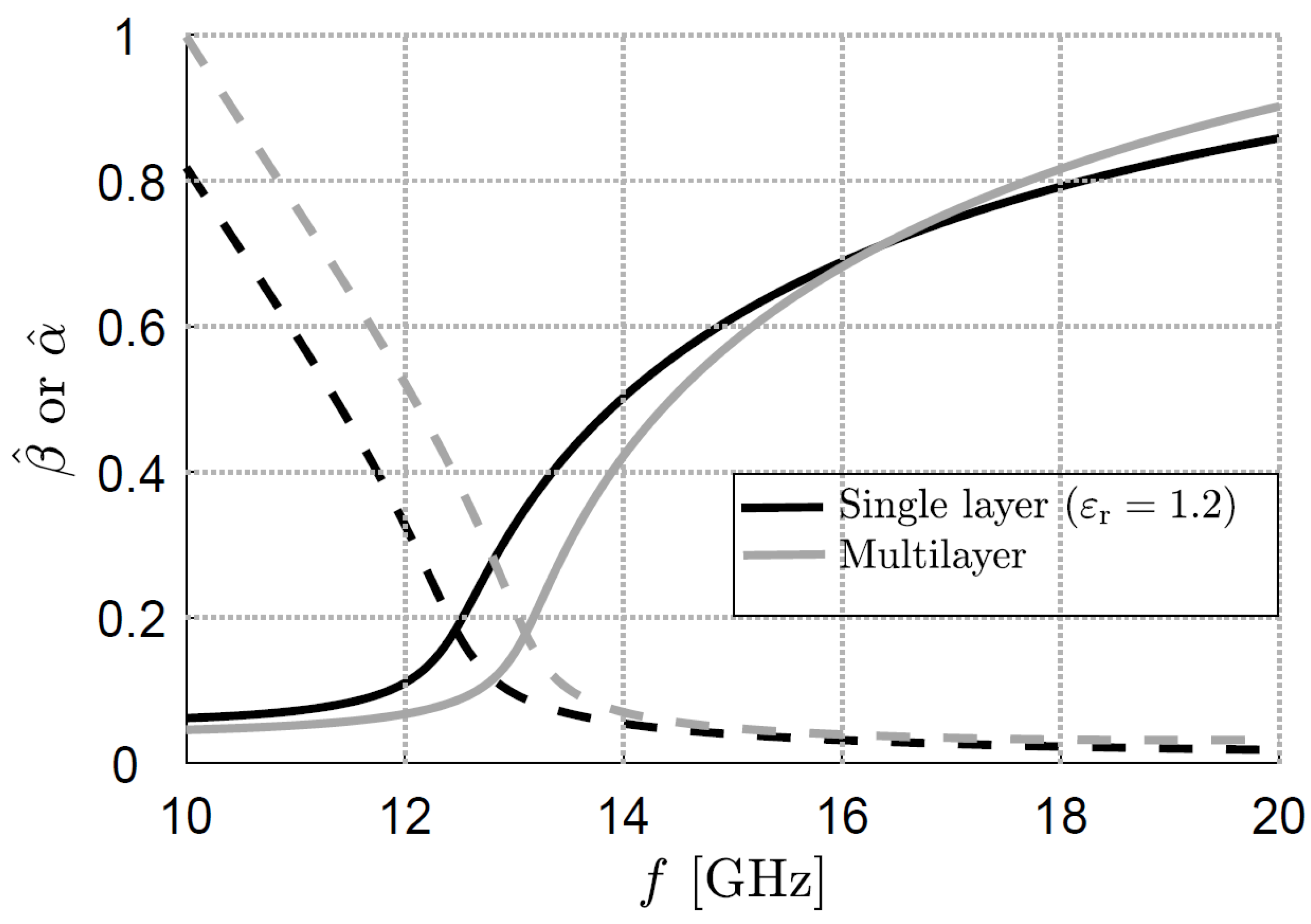

2. Fabry–Perot Cavity Antennas

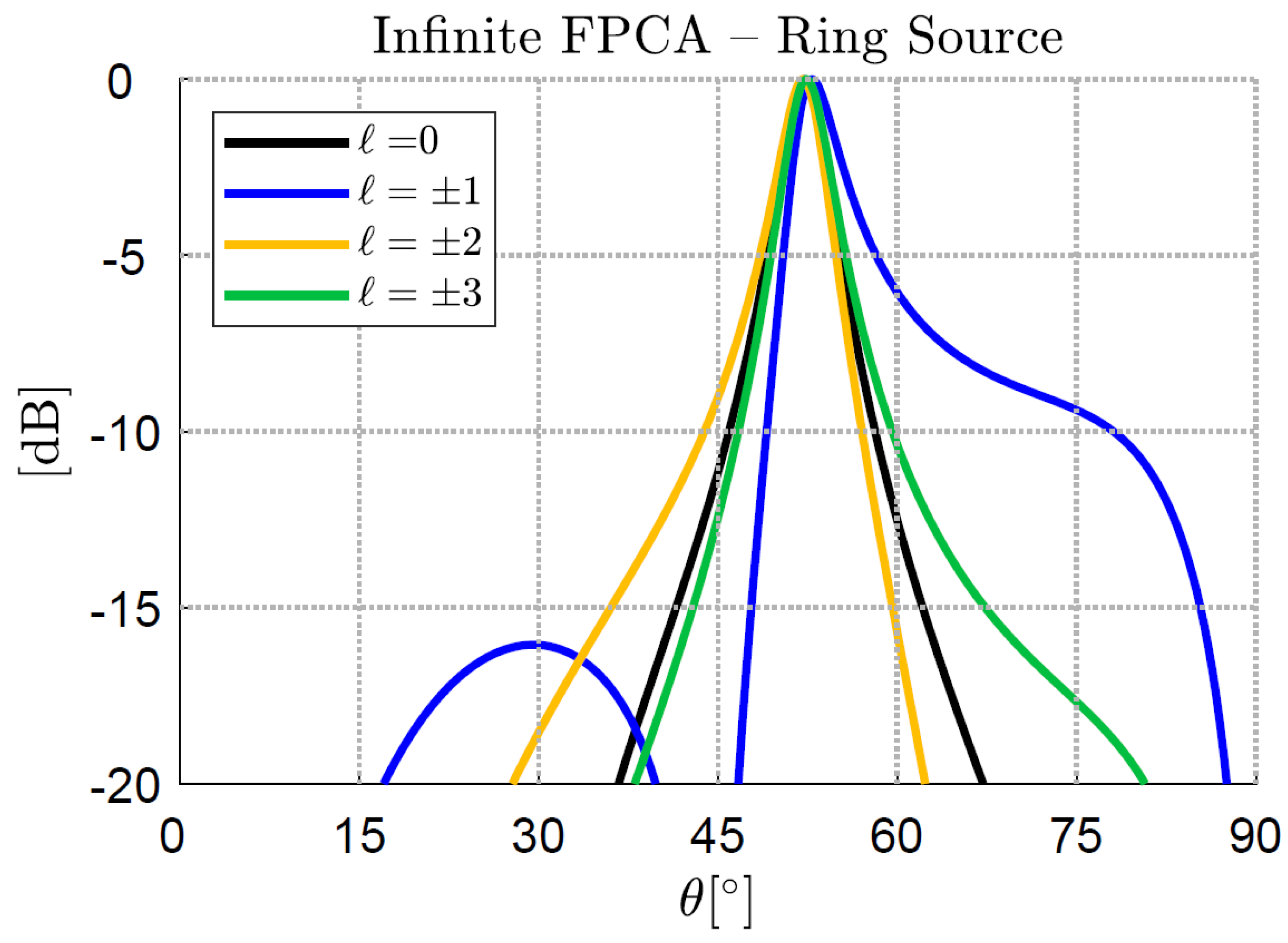

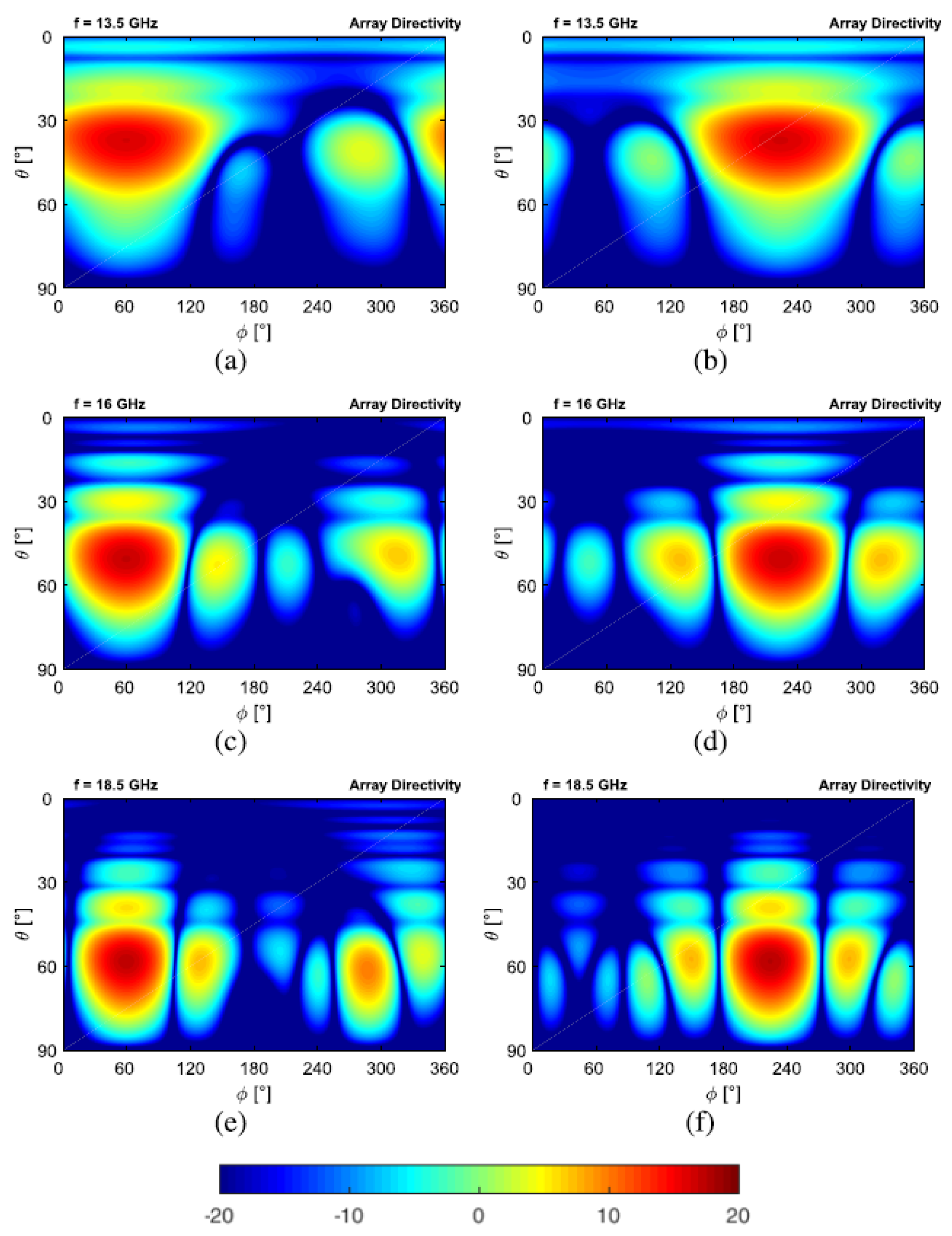

2.1. Fabry–Perot Cavities and Far-Field Twisted Beams

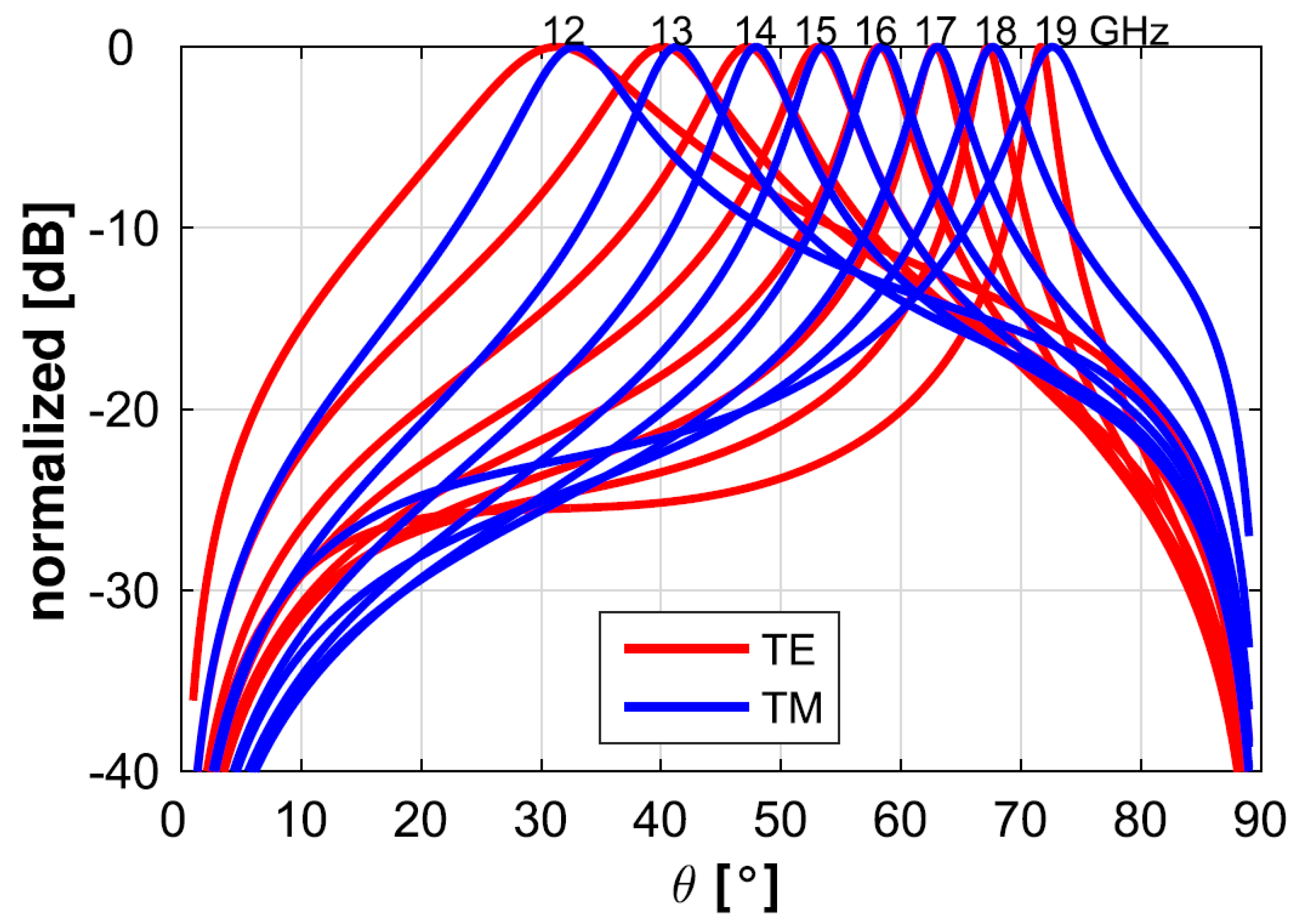

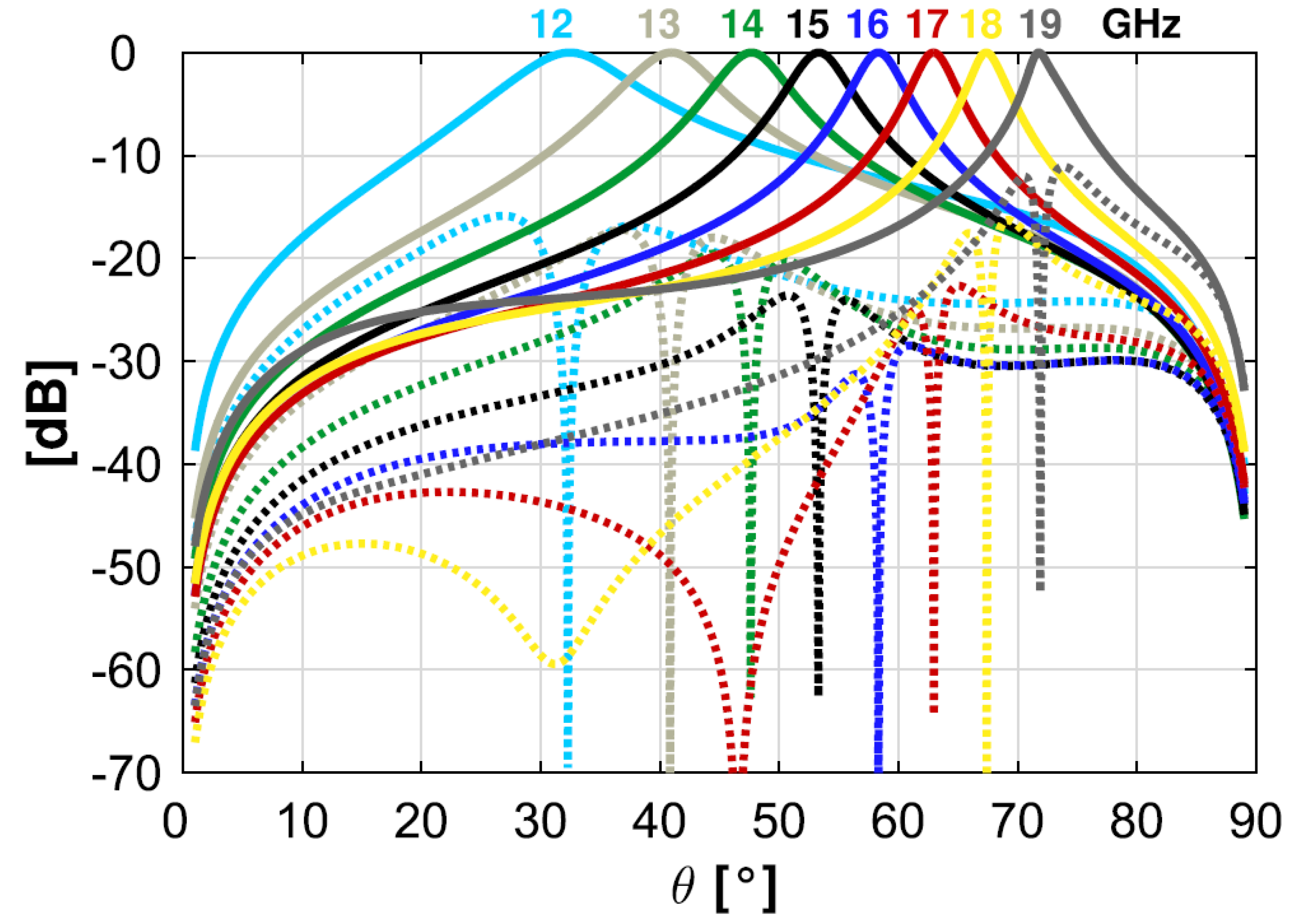

2.2. Fabry–Perot Cavities for Far-Field Polarization Reconfiguration

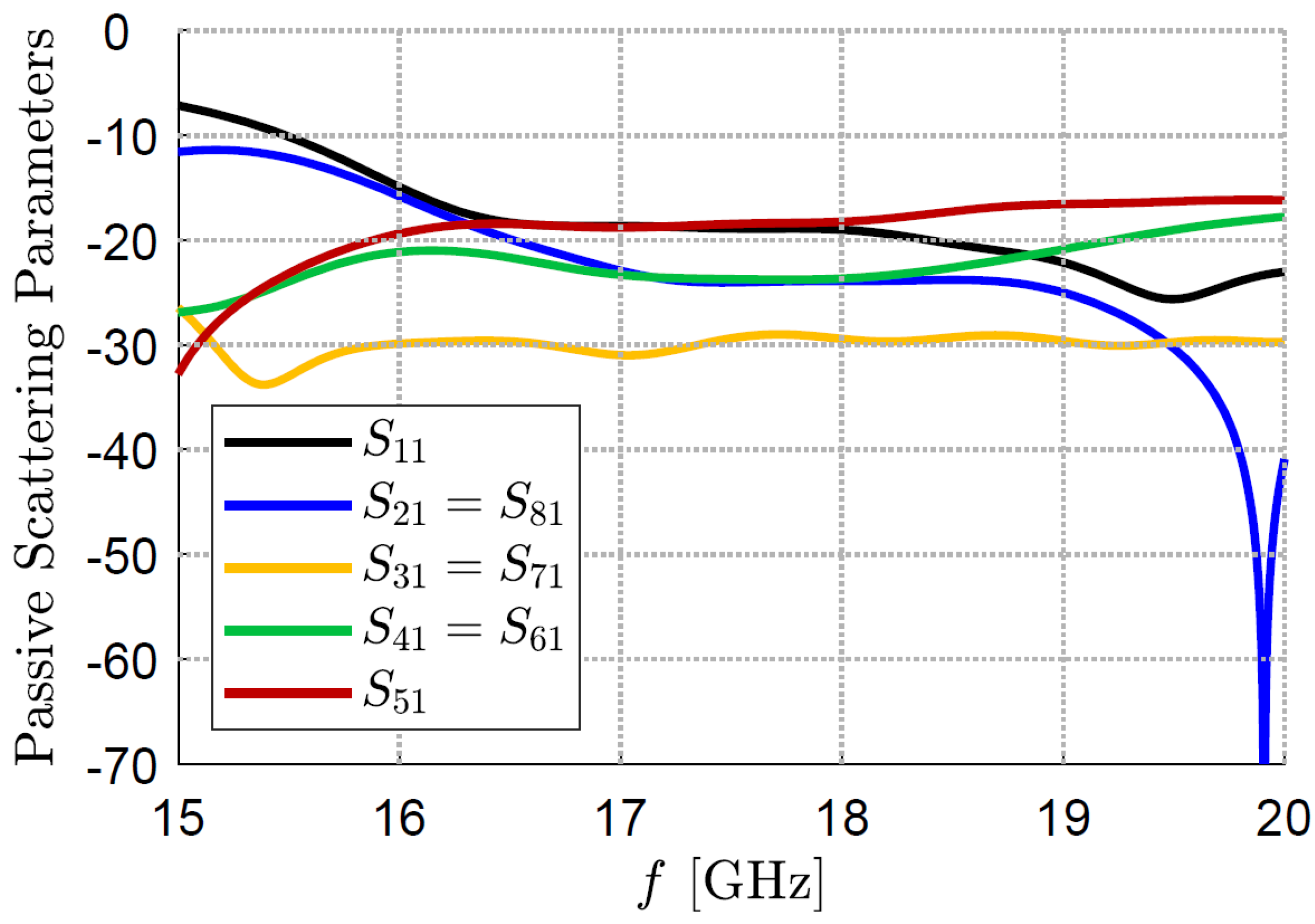

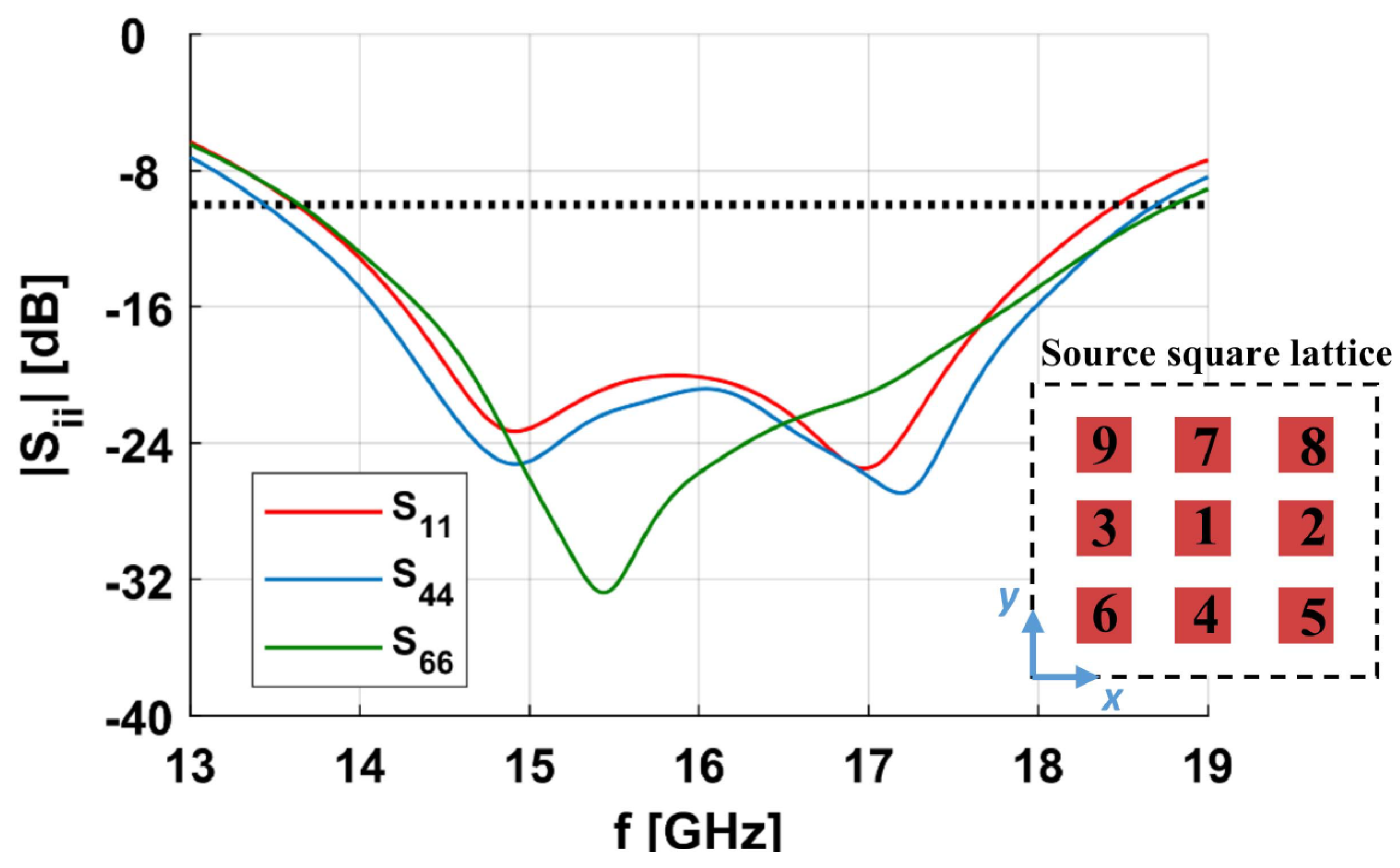

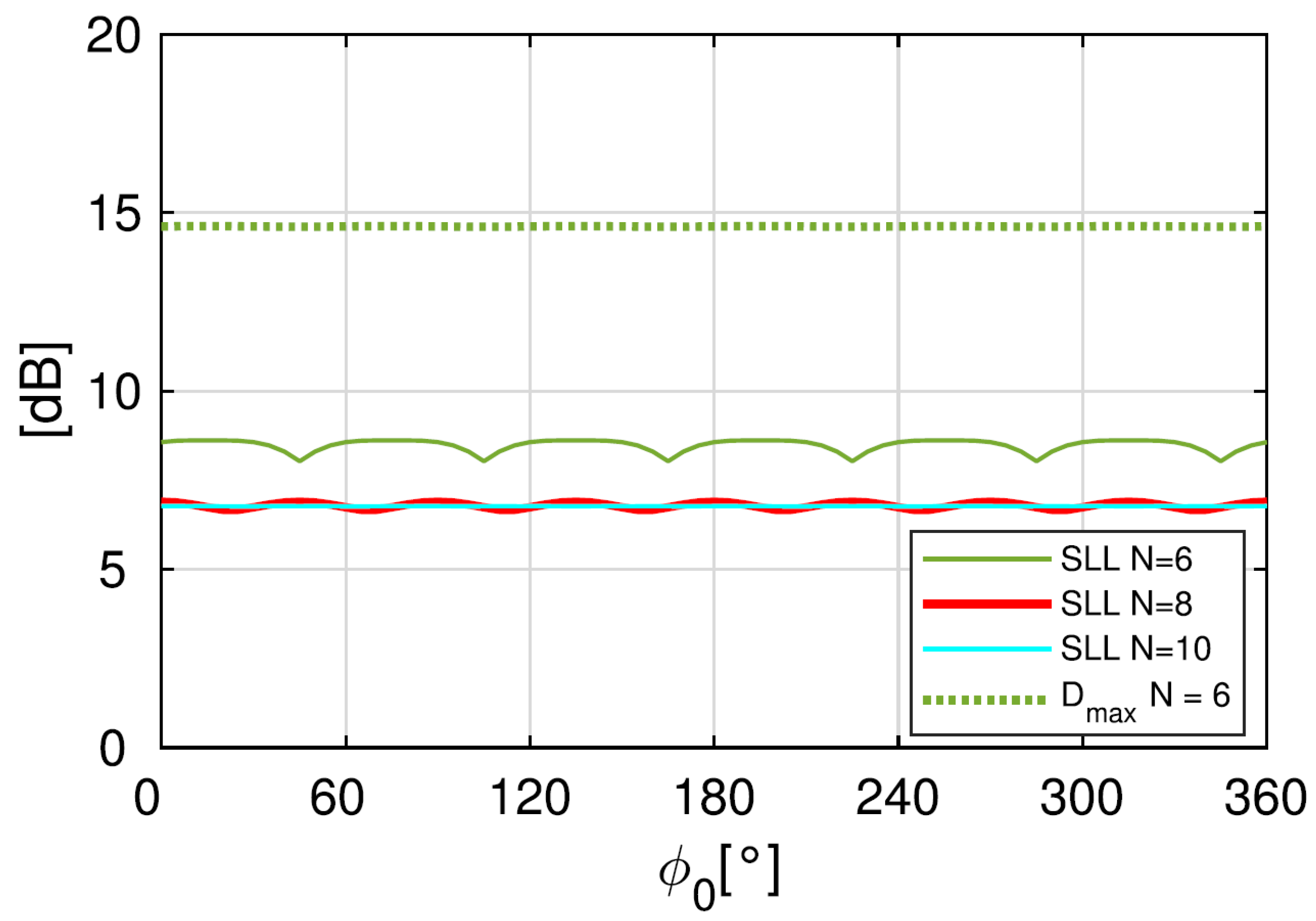

2.3. Fabry–Perot Cavities for Beam Scanning in Elevation and Azimuth

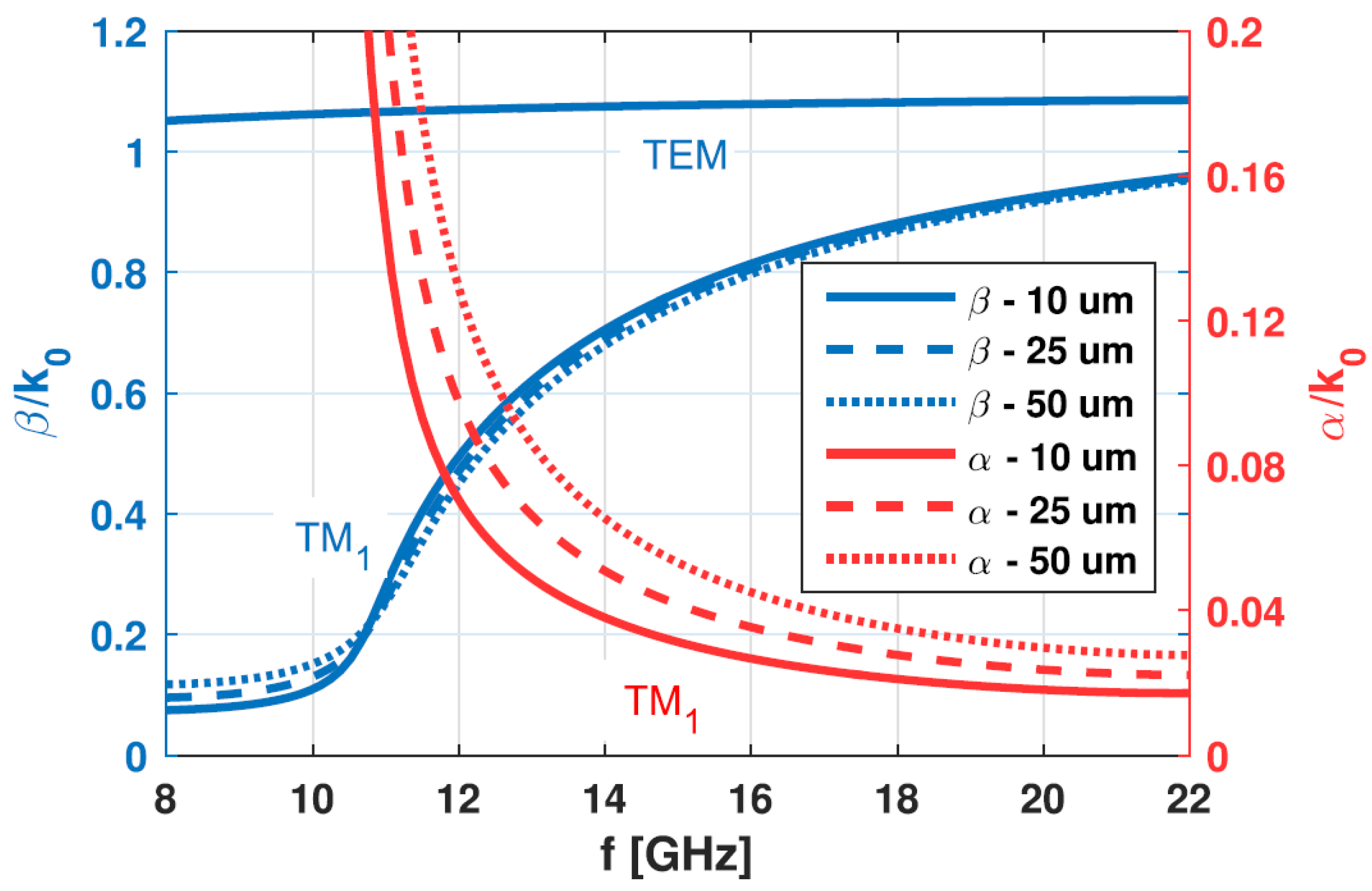

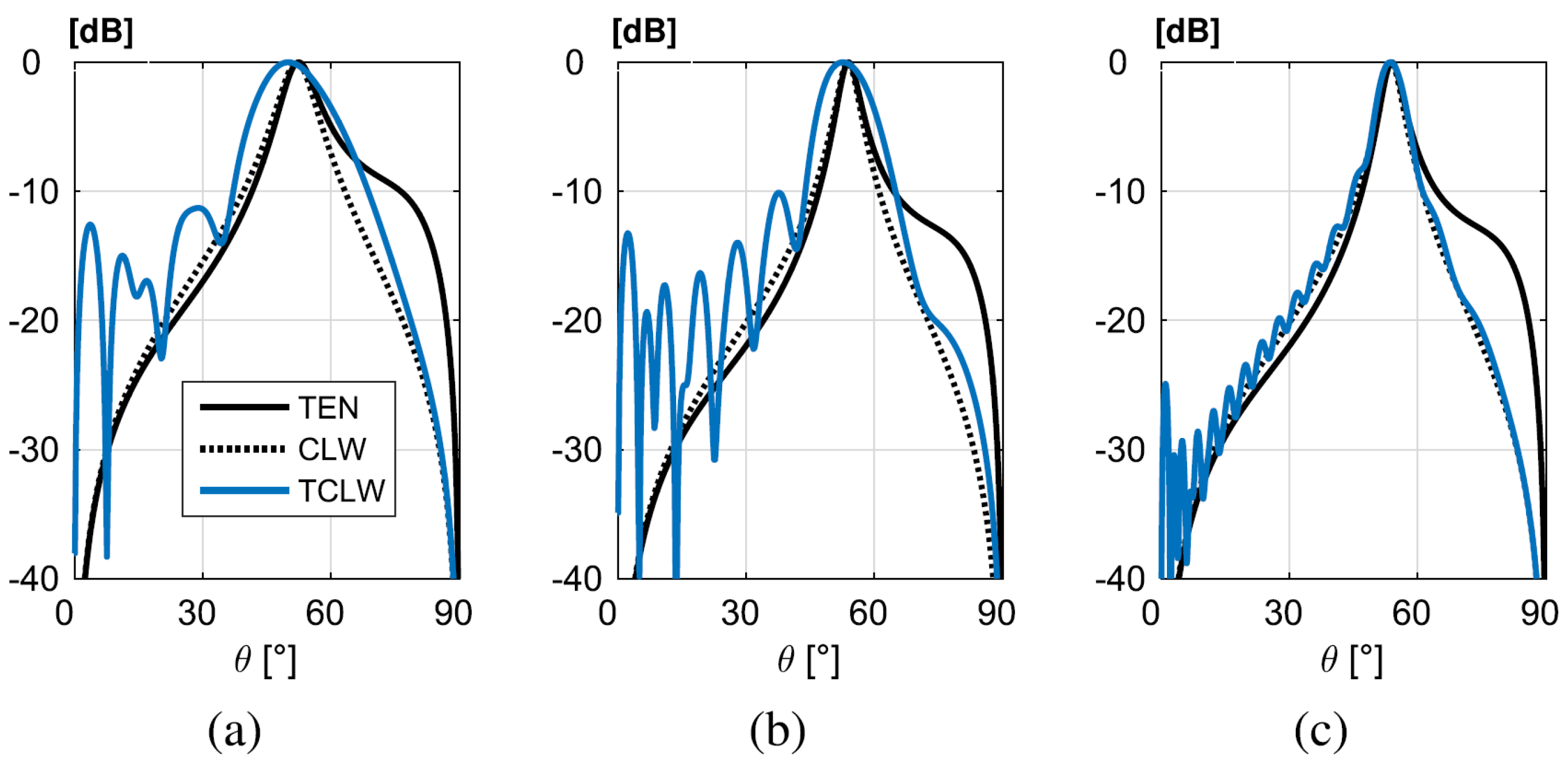

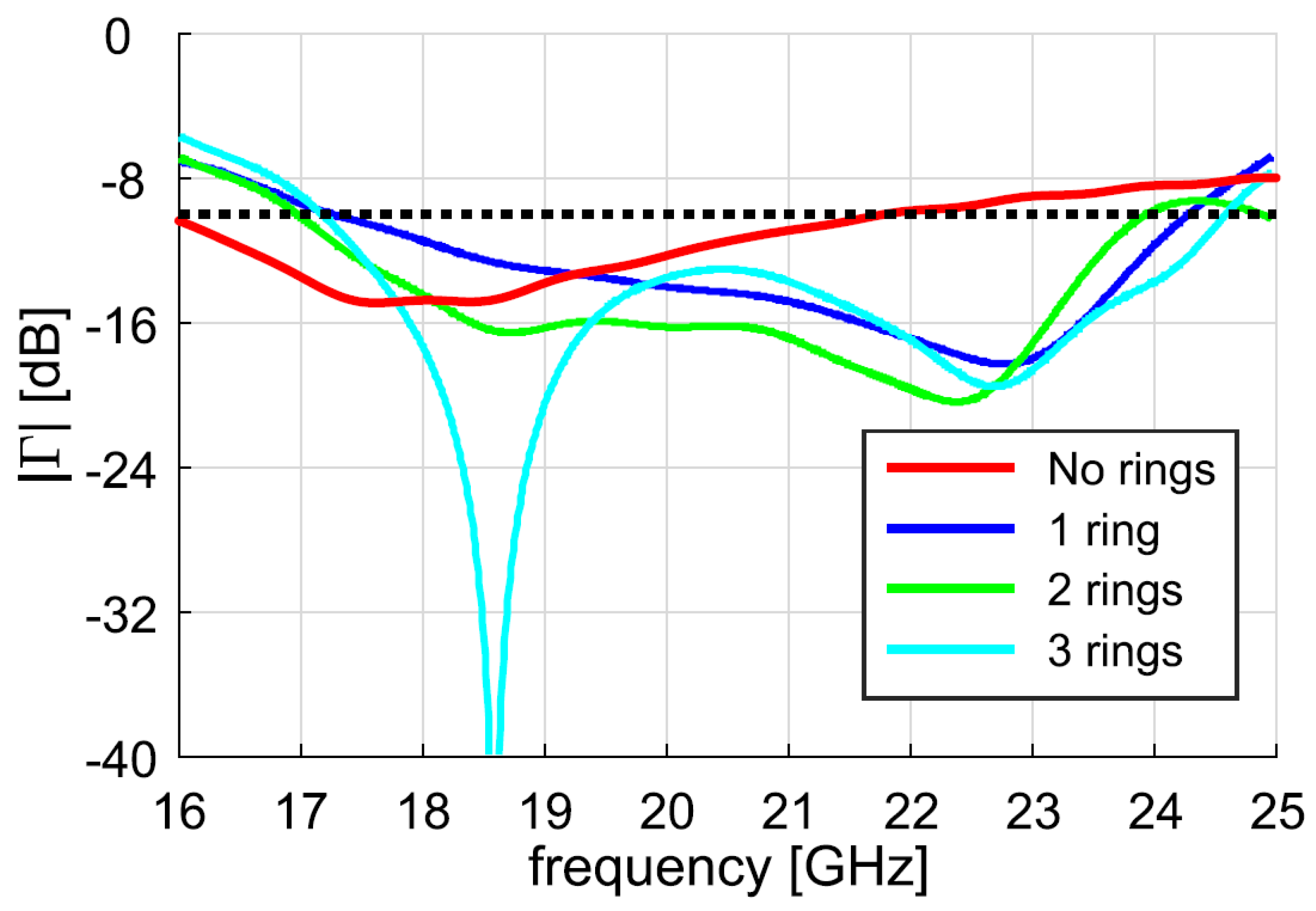

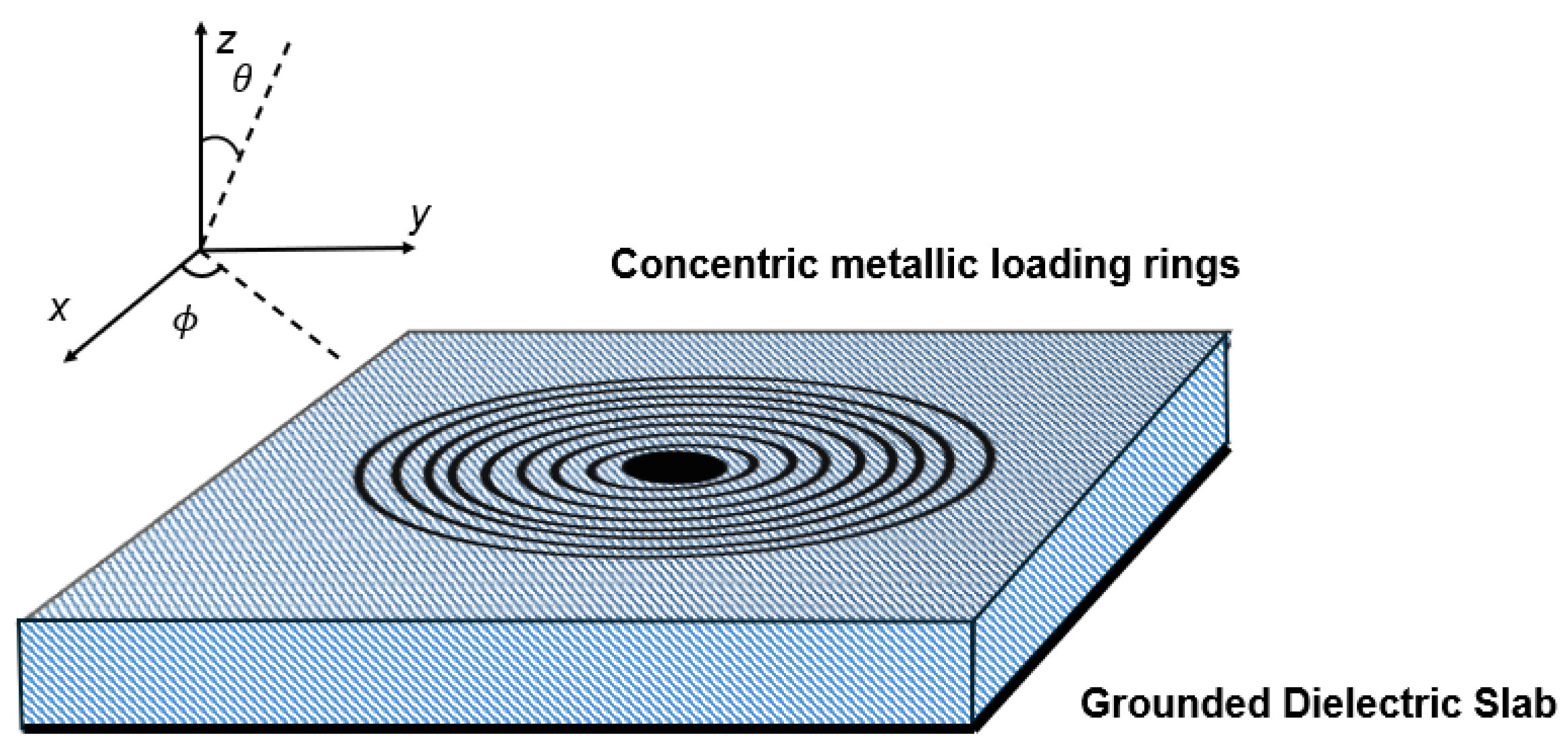

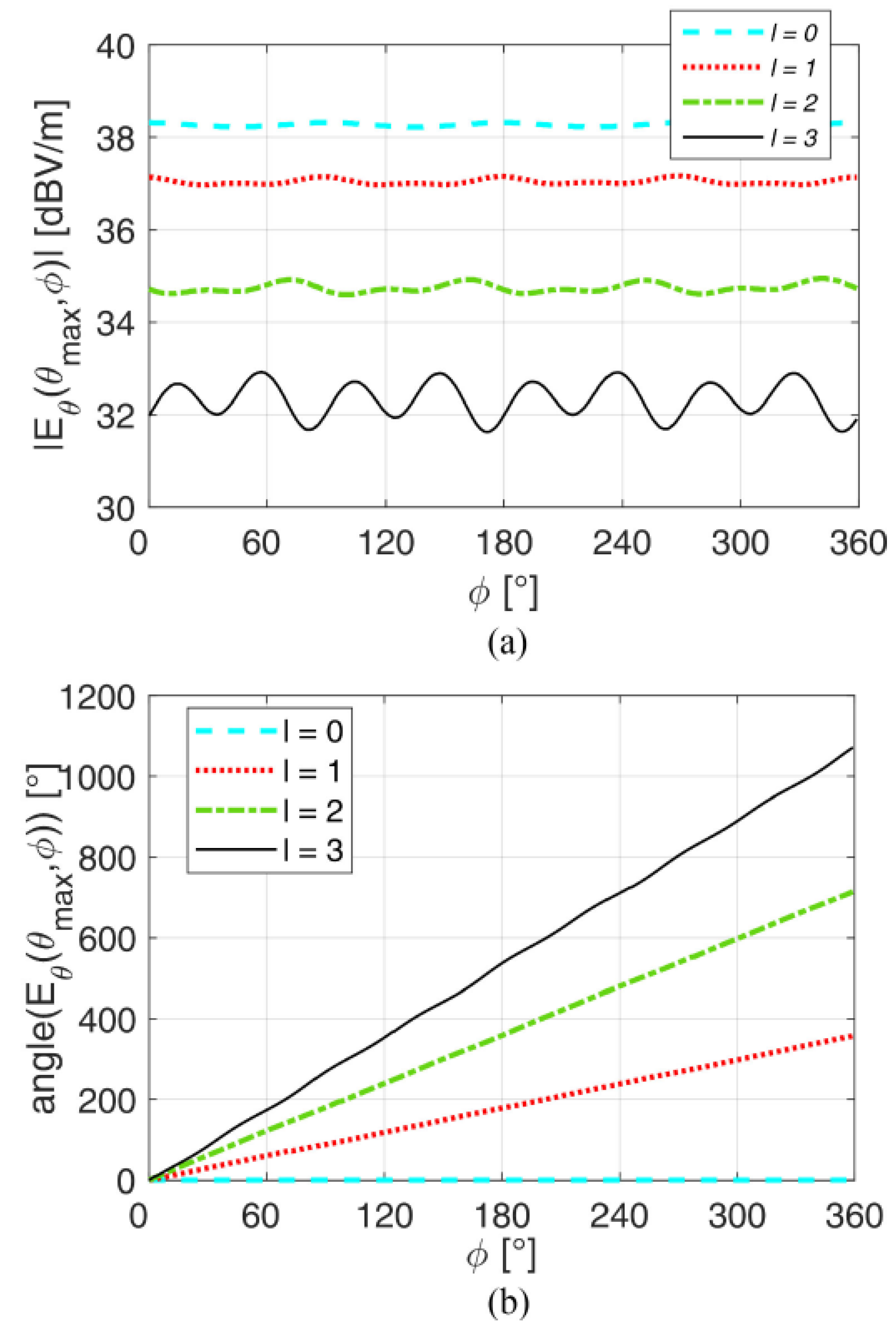

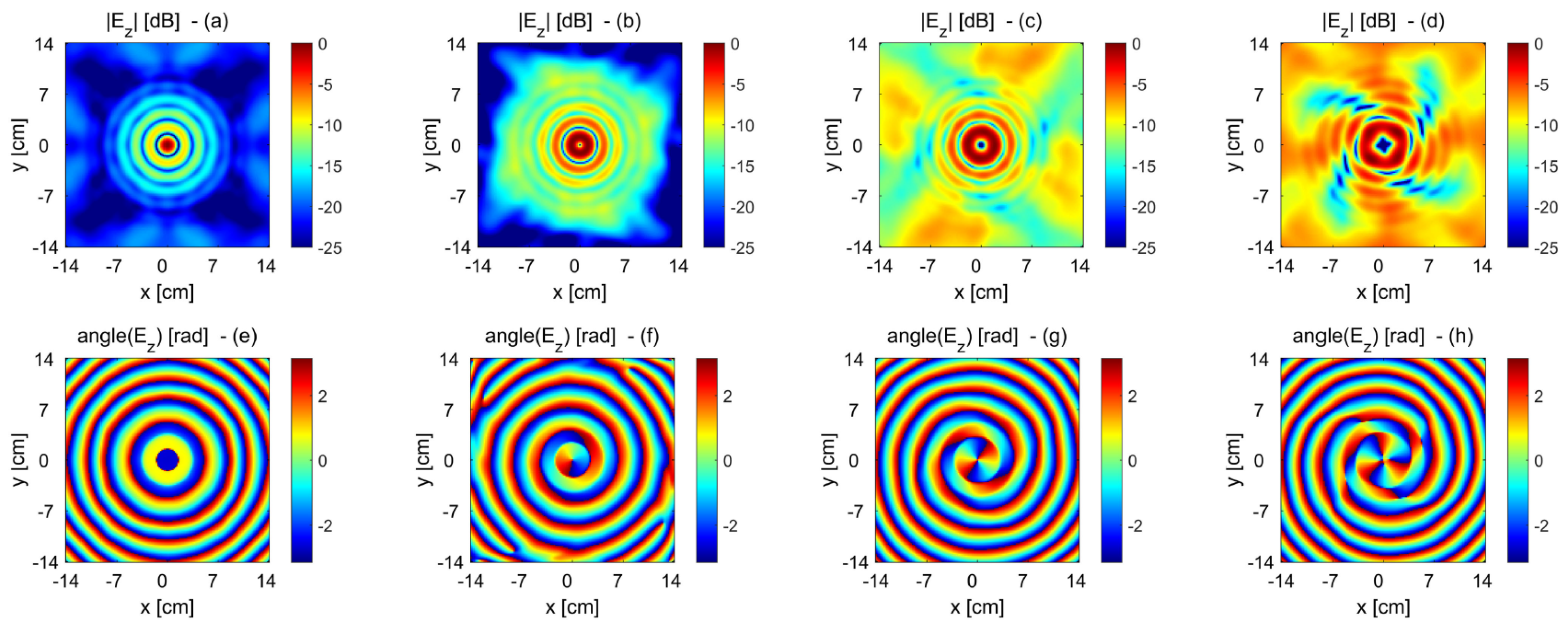

3. Bull’s-Eye Antennas

4. Conclusion

References

- Hessel, A. General characteristics of traveling-wave antennas. In Antenna Theory, Part 2; Collin, R.E., Zucker, F.J., Eds.; McGraw-Hill: New York, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Marcuvitz, N. On field representations in terms of leaky modes or eigenmodes. IRE Trans. Antennas Propag. 1956, 4, 192–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstone, L.; Oliner, A. Leaky-wave antennas I: Rectangular Waveguides. IRE Trans. Antennas Propag. 1959, 7, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstone, L.; Oliner, A. Leaky-wave antennas II: Circular Waveguides. IRE Trans. Antennas Propag. 1961, 9, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balanis, C.A. Advanced Engineering Electromagnetics; 2012.

- Ip, A.; Jackson, D.R. Radiation from cylindrical leaky waves. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 1990, 38, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felsen, L. Real spectra, complex spectra, compact spectra. JOSA A 1986, 3, 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuscaldo, W.; Jackson, D.R.; Galli, A. General formulas for the beam properties of 1-D bidirectional leaky-wave antennas. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2019, 67, 3597–3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Jackson, D.R.; Williams, J.T.; Oliner, A.A. General formulas for 2-D leaky-wave antennas. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2005, 53, 3525–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamir, T.; Oliner, A.A. Guided complex waves, Part 1: Fields at an interface Fields at an interface. Proc. Inst. Electr. Eng. 1963, 110, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamir, T.; Oliner, A.A. Guided complex waves, Part 2: Relation to radiation patterns. Proc. Inst. Electr. Eng. 1963, 110, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuscaldo, W.; Burghignoli, P.; Galli, A. Genealogy of Leaky, Surface, and Plasmonic Modes in Partially Open Waveguides. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2022, 17, 034–038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabry, C. Theorie et applications d’une nouvelle methods de spectroscopie intereferentielle. Ann. Chim. Ser. 7 1899, 16, 115–144. [Google Scholar]

- Trentini, G.V. Partially reflecting sheet arrays. IRE Trans. Antennas Propag. 1956, 4, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.; Oliner, A.; Ip, A. Leaky-wave propagation and radiation for a narrow-beam multiple-layer dielectric structure. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 1993, 41, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovat, G.; Burghignoli, P.; Jackson, D.R. Fundamental properties and optimization of broadside radiation from uniform leaky-wave antennas. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2006, 54, 1442–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burghignoli, P.; Fuscaldo, W.; Galli, A. Fabry–Perot Cavity Antennas: The Leaky-Wave Perspective. IEEE Antennas Propag. Mag. 2021, 63, 116–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burghignoli, P.; Fuscaldo, W.; Mancini, F.; Comite, D.; Baccarelli, P.; Galli, A. Twisted beams with variable OAM order and consistent beam angle via single uniform circular arrays. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 163006–163014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Shen, X.; Su, G.; Li, L.; Ding, J.; Liu, F.; Zhan, P.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z. Efficient generation of microwave plasmonic vortices via a single deep-subwavelength meta-particle. Laser Photon. Rev. 2018, 12, 1800010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Xie, G.; Lavery, M.P.; Huang, H.; Ahmed, N.; Bao, C.; Ren, Y.; Cao, Y.; Li, L.; Zhao, Z.; et al. High-capacity millimetre-wave communications with orbital angular momentum multiplexing. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, L.; Beijersbergen, M.W.; Spreeuw, R.; Woerdman, J. Orbital angular momentum of light and the transformation of Laguerre-Gaussian laser modes. Phys. Rev. Appl. 1992, 45, 8185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Sasaki, H.; Fukumoto, H.; Yagi, Y.; Shimizu, T. An evaluation of orbital angular momentum multiplexing technology. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trichili, A.; Park, K.H.; Zghal, M.; Ooi, B.S.; Alouini, M.S. Communicating using spatial mode multiplexing: Potentials, challenges, and perspectives. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2019, 21, 3175–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Wang, H.; Qin, Y.; Cheng, Y. Electromagnetic vortex imaging using uniform concentric circular arrays. IEEE Antennas and Wireless Propag. Lett. 2015, 15, 1024–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luukkonen, O.; Simovski, C.; Granet, G.; Goussetis, G.; Lioubtchenko, D.; Raisanen, A.V.; Tretyakov, S.A. Simple and accurate analytical model of planar grids and high-impedance surfaces comprising metal strips or patches. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2008, 56, 1624–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burghignoli, P.; Fuscaldo, W.; Comite, D.; Baccarelli, P.; Galli, A. Higher-Order Cylindrical Leaky Waves–Part I: Canonical sources and radiation formulas. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2019, 67, 6735–6747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burghignoli, P.; Comite, D.; Fuscaldo, W.; Baccarelli, P.; Galli, A. Higher-Order Cylindrical Leaky Waves–Part II: Circular Array Design and Validations. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2019, 67, 6748–6760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajiwara, A. Line-of-sight indoor radio communication using circular polarized waves. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 1995, 44, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comite, D.; Baccarelli, P.; Burghignoli, P.; Galli, A. Omnidirectional 2-D leaky-wave antennas with reconfigurable polarization. IEEE Antennas and Wireless Propag. Lett. 2017, 16, 2354–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuscaldo, W.; Galli, A.; Jackson, D.R. Optimization of 1-D unidirectional leaky-wave antennas based on partially reflecting surfaces. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2022, 70, 7853–7868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailloux, R.J. Phased array antenna handbook; Artech House, 2017.

- Borselli, L.; Di Nallo, C.; Galli, A.; Maci, S. Arrays with widely-spaced high-gain planar elements. Proc. IEEE Antennas Propag. Soc. Int. Symp. 1998 Digest. Antennas: Gateways to the Global Network. Held in conjunction with: USNC/URSI Nat. Radio Sci. Meeting (Cat. No. 98CH36). IEEE, 1998, Vol. 2, pp. 1142–1145.

- Gardelli, R.; Albani, M.; Capolino, F. Array thinning by using antennas in a Fabry–Perot cavity for gain enhancement. IEEE Trans. Antennas and Propag. 2006, 54, 1979–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scattone, F.; Ettorre, M.; Fuchs, B.; Sauleau, R.; Fonseca, N.J. Synthesis procedure for thinned leaky-wave-based arrays with reduced number of elements. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2015, 64, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, F.; Bianchi, D.; Monorchio, A.; Manara, G. Analytical design of extremely high-gain Fabry-Perot/leaky antennas by using multiple feeds. Proc. Int. Conf. Electromagn. Adv. Appl. (ICEAA), 2017. IEEE, 2017, pp. 1673–1675.

- Shahzadi, I.; Comite, D.; Kuznetcov, M.V.; Podilchak, S.K. Compact Dual-Polarized Fabry-Perot Leaky-Wave Antenna for Full-Duplex Broadband Applications. IEEE Antennas and Wireless Propag. Lett. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comite, D.; Burghignoli, P.; Baccarelli, P.; Galli, A. 2-D beam scanning with cylindrical-leaky-wave-enhanced phased arrays. IEEE Trans. Antennas and Propag. 2019, 67, 3797–3808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comite, D.; Podilchak, S.K.; Kuznetcov, M.; Buendía, V.G.G.; Burghignoli, P.; Baccarelli, P.; Galli, A. Wideband array-fed Fabry-Perot cavity antenna for 2-D beam steering. IEEE Trans. Antennas and Propag. 2020, 69, 784–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccarelli, P.; Burghignoli, P.; Lovat, G.; Paulotto, S. A novel printed leaky-wave’Bull’s-Eye’antenna with suppressed surface-wave excitation. Proc. IEEE Antennas Propag. Soc. Symp., 2004. IEEE, 2004, Vol. 1, pp. 1078–1081.

- Encinar, J.A. Mode-matching and point-matching techniques applied to the analysis of metal-strip-loaded dielectric antennas. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 1990, 38, 1405–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglielmi, M.; Jackson, D. Broadside radiation from periodic leaky-wave antennas. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 1993, 41, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burghignoli, P.; Baccarelli, P.; Frezza, F.; Galli, A.; Lampariello, P.; Oliner, A. Low-frequency dispersion features of a new complex mode for a periodic strip grating on a grounded dielectric slab. IEEE Trans. Microwave Theory Tech. 2002, 49, 2197–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albani, M.; Pavone, S.C.; Casaletti, M.; Ettorre, M. Generation of non-diffractive Bessel beams by inward cylindrical traveling wave aperture distributions. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 18354–18364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, B.G.; Li, Y.B.; Jiang, W.X.; Cheng, Q.; Cui, T.J. Generation of spatial Bessel beams using holographic metasurface. Opt. Express 2015, 23, 7593–7601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ettorre, M.; Grbic, A. Generation of propagating Bessel beams using leaky-wave modes. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2012, 60, 3605–3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuscaldo, W.; Comite, D.; Boesso, A.; Baccarelli, P.; Burghignoli, P.; Galli, A. Focusing Leaky Waves: A Class of Electromagnetic Localized Waves with Complex Spectra. Phys. Rev. Appl. 4005, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xue, H.; Liu, Y.; Feng, Q.; Li, L. Generation of high-order Bessel orbital angular momentum vortex beam using a single-layer reflective metasurface. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 126504–126510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Yang, J.; Meng, H.; Dou, W.; Hu, S. Generating millimeter-wave Bessel beam with orbital angular momentum using reflective-type metasurface inherently integrated with source. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2018, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.B.; Chan, K.F.; Chan, C.H. 3-D printed terahertz lens to generate higher order Bessel beams carrying OAM. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2020, 69, 3399–3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Mazzinghi, A.; Freni, A.; Hirokawa, J. Simultaneous generation of three OAM modes by using a RLSA fed by a waveguide circuit for 60 GHz-band radiative near-field region OAM multiplexing. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2020, 69, 1249–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comite, D.; Fuscaldo, W.; Merola, G.; Burghignoli, P.; Baccarelli, P.; Galli, A. Twisted Bessel beams via bull-eye antennas excited by a single uniform circular array. IEEE Antennas and Wireless Propag. Lett. 2021, 20, 663–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).