Submitted:

22 June 2024

Posted:

24 June 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Glucose - hexokinase method,

- Triglycerides - GPO-PAP method,

- Urea - Uryase/GLDH method,

- Total protein - Biuret End Point method,

- ASAT, ALAT, GGT, and alkaline phosphatase - enzymatic IFCC method at 37°C,

- Cortisol - ECLIA method,

- Inorganic phosphorus and calcium - ammonium phosphomolybdate UV method and Arsenaso III method.

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Renaudeau, D.; Collin, A.; Yahav, S.; de Basilio, V.; Gourdine, J.L.; Collier, R.J. Adaptation to hot climate and strategies to alleviate heat stress in livestock production. Animal 2012, 6, 707–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segnalini, M.; Bernabucci, U.; Vitali, A.; et al. Temperature humidity index scenarios in the Mediterranean basin. Int. J Biometeorol. 2013, 57, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fournel, S.; Ouellet, V.; Charbonneau, É. Practices for Alleviating Heat Stress of Dairy Cows in Humid Continental Climates: A Literature Review. Animals 2017, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wankar, A.K.; Rindhe, S.N.; Doijad, N.S. Heat stress in dairy animals and current milk production trends, economics, and future perspectives: The global scenario. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2021, 53, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mezzetti, M.; Cattaneo, L.; Passamonti, M.M.; Lopreiato, V.; Minuti, A.; Trevisi, E. The transition period updated: A review of the new insights into the adaptation of dairy cows to the new lactation. Dairy 2021, 2, 617–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammad, A.; Wang, Y.J.; Umer, S.; Lirong, H.; Khan, I.; Khan, A.; Ahmad, B.; Wang, Y. Nutritional Physiology and Biochemistry of Dairy Cattle under the Influence of Heat Stress: Consequences and Opportunities. Animals 2020, 10, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigeri, K.D.M.; Kachinski, K.D.; Ghisi, N.d.C.; Deniz, M.; Damasceno, F.A.; Barbari, M.; Herbut, P.; Vieira, F.M.C. Effects of Heat Stress in Dairy Cows Raised in the Confined System: A Scientometric Review. Animals 2023, 13, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, R.; Hristev, H.; Gergovska, Z. Influence of the level of daily milk yield on some blood biochemical parameters in dairy cows reared under the same temperature and humidity conditions. Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2022, 28 (Suppl. S1), 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Mylostyvyi, R.V.; Sejian, V. Welfare of dairy cattle in conditions of global climate change. Theor. Appl. Vet. Med. 2019, 7, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndlovu, T.; Chimonyo, M.; Okoh, A.I.; Muchenje, V.; Dzama, K.; Raats, J.G. Assessing the nutrititional status of beef cattle: Current practices and future prospects. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2007, 6, 2727–273. [Google Scholar]

- Correa-Calderon, A.; Armstrong, D.; Ray, D.; DeNise, S.; Enns, M.; Howison, C. Thermoregulatory responses of Holstein and Brown Swiss Heat-Stressed dairy cows to two different cooling systems. Int. J Biometeorol. 2004, 48, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.G.; Dale, V.H.; Gardner, R.H. Predicting across scales: Theory development and testing. Landscape ecology 1989, 3, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantner, V.; Mijić, P.; Kuterovac, K.; Solić, D.; Gantner, R. Temperature-humidity index values and their significance on the daily production of dairy cattle. Mljekarstvo 2011, 61, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, D.V. Heat stress interaction with shade and cooling. J. Dairy Sci. 1994, 77, 2044–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravagnolo, O.; Misztal, I.; Hoogenboom, G. Genetic component of heat stress in dairy cattle, development of heat index function. J. Dairy Sci. 2000, 83, 2120–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadzere, C.T.; Murphy MRSilanikove, N.; Maltz, E. Heat stress in lactating dairy cows: A review. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2002, 77, 59–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brügemann, K.; Gernand, E.; König von Borstel, U.; König, S. Defining and evaluating heat stress thresholds in different dairy cow production systems. Archives Animal Breeding 2012, 55, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorniak, T.; Meyer, U.; Südekum, K.H.; Dänicke, S. Impact of mild heat stress on dry matter intake, milk yield and milk composition in mid-lactation Holstein dairy cows in a temperate climate. Arch Anim Nutrit 2014, 68, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blond, B.; Majkić, M.; Spasojević, J.; Hristov, S.; Radinović, M.; Nikolić, S.; Anđušić, L.; Čukić, A.; Došenović Marinković, M.; Vujanović, B.D.; et al. Influence of Heat Stress on Body Surface Temperature and Blood Metabolic, Endocrine, and Inflammatory Parameters and Their Correlation in Cows. Metabolites 2024, 14, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbelman, R.B.; Rhoads, R.P.; Rhoads, M.L.; Duff, G.C.; Baumgard, L.H.; Collier, R.J. A re-evaluation of the impact of temperature humidity index (THI) and black globe humidity index (BGHI) on milk production in high producing dairy cows. Pages 158–169 in Proceedings of the Southwest Nutrition Conference. Accessed Feb. 2, 2009.

- Berman, A. Estimates of heat stress relief needs for Holstein dairy cows. J. Anim. Sci. 2005, 83, 1377–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rensis, F.; Garcia-Ispierto, I.; Lopez-Gatius, F. Seasonal heat stress: Clinical implications and hormone treatments for the fertility of dairy cows. Theriogenology 2015, 84, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avendaño-Reyes, L. Heat stress management for milk production in arid zones. In: Narongsak Chaiyabutr editor. Milk production - An up-to-date overview of animal nutrition, management and health. Intech Open, London UK 2012, 165–184.

- Carter, B.H.; Friend, T.H.; Sawyer, J.A.; Garey, S.M.; Alexander, M.B.; Carter, M.J.; et al. Effect of feed-bunk sprinklers on attendance at unshaded feed bunks in drylot dairies. Prof. Anim. Sci. 2011, 27, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorniak, T.; Meyer, U.; Südekum, K.H.; Dänicke, S. Impact of mild heat stress on dry matter intake, milk yield and milk composition in mid-lactation Holstein dairy cows in a temperate climate. Arch Anim Nutrit 2014, 68, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, M.L.; Bignardi, A.B.; Pereira, R.J.; Stefani, G.; El Faro, L. Genetics of heat tolerance for milk yield and quality in Holsteins. Animal 2017, 11, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Li, L.; Chen, X.; Lu, Y.; Wang, D. Effects of heat stress on body temperature, milk production, and reproduction in dairy cows: A novel idea for monitoring and evaluation of heat stress—A review. Asian Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 32, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turk, R.; Rošić, N.; Vince, S.; Perkov, S.; Samardžija, M.; Beer-Ljubić, B.; Belić, M.; Robić, M. The influence of heat stress on energy metabolism in Simmental dairy cows during the periparturient period. Vet. Arh. 2020, 90, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, Z.; Sammad, A.; Hu, L.; Fang, H.; Xu, Q.; Wang, Y. Glucose Metabolism and Dynamics of Facilitative Glucose Transporters (GLUTs) under the Influence of Heat Stress in Dairy Cattle. Metabolites 2020, 10, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendall, P.E.; Webster, J.R. Season and physiological status affects the circadian body temperature rhythm of dairy cows. Livest. Sci. 2009, 125, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, R.J.; Baumgard, L.H.; Lock, A.L.; Bauman, D.E. Physiological limitations, nutrient partitioning. Yield of farmed species. Constraints and opportunities in the 21st Century (ed. R Sylvester-Bradley and J Wiseman) 2005, 351–377.

- Fox, D.G.; Tylutki, T.P. Accounting for the Effects of Environment on the Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 1998, 81, 3085–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheelock, J.B.; Rhoads, R.P.; VanBaale, M.J.; Sanders, S.R.; Baumgard, L.H. Effects of heat stress on energetic metabolism in lactating Holstein cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2010, 93, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgard, L.H.; Rhoads, R.P. Effects of Heat Stress on Postabsorptive Metabolism and Energetics. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2013, 1, 311–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahzad, K.; Akbar, H.; Vailati-Riboni, M.; Basirico, L.; Morera, P.; Rodriguez-Zas, S.L.; Loor, J.J. The effect of calving in the summer on the hepatic transcriptome of Holstein cows during the peripartal period. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 5401–5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Loor, J.J.; Piccioli-Cappelli, F.; Librandi, F.; Lobley, G.E.; Trevisi, E. Circulating amino acids in blood plasma during the peripartal period in dairy cows with different liver functionality index. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 2257–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Gao, S.; Quan, S.; Zhang, Y.; Bu, D.; Wang, J. Blood amino acids profile responding to heat stress in dairy cows. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 31, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, A.W.; Burhans, W.S.; Overton, T.R. Protein nutrition in late pregnancy, maternal protein reserves and lactation performance in dairy cows. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2000, 59, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shwartz, G.; Rhoads, M.L.; Vanbaale, M.J.; Rhoads, R.P.; Baumgard, L.H. Effects of a supplemental yeast culture on heat-stressed lactating Holstein cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, P.L.; Beede, D.K.; Wilcox, C.J. Nycterohemeral Patterns of Acid-Base Status, Mineral Concentrations and Digestive Function of Lactating Cows in Natural or Chamber Heat Stress Environments2. J. Anim. Sci. 1988, 66, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowley, F.C.; Barber, D.G.; Houlihan, A.V.; Poppi, D.P. Immediate and residual effects of heat stress and restricted intake on milk protein and casein composition and energy metabolism. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 2356–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joo, S.S.; Lee, S.J.; Park, D.S.; Kim, D.H.; Gu, B.-H.; Park, Y.J.; Rim, C.Y.; Kim, M.; Kim, E.T. Changes in Blood Metabolites and Immune Cells in Holstein and Jersey Dairy Cows by Heat Stress. Animals 2021, 11, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahen, P.J.; Williams, H.J.; Smith, R.F.; Grove-White, D. Effect of blood ionised calcium concentration at calving on fertility outcomes in dairy cattle. Vet. Rec. 2018, 183, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roti, J.L. Cellular responses to hyperthermia (40–46°C): Cell killing and molecular events. Int. J. Hyperth. 2008, 24, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhoads, R.P.; La Noce, A.J.; Wheelock, J.B.; Baumgard, L.H. Short communication: Alterations in expression of gluconeogenic genes during heat stress and exogenous bovine somatotropin administration. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 1917–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamer, M. The role of prolactin in thermoregulation and water balance during heat stress in domestic ruminants. Asian J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 2011, 6, 1153–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, S.; Mackay, B.J. Plasma prolactin levels and body fluid deficits in the rat: Causal interactions and control of water intake. J. Physiol. 1983, 336, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blake, M.J.; Buckley, A.R.; Zhang, M.; Buckley, D.J.; Lavoi, K.P. A novel heat shock response in prolactin-dependent Nb2 node lymphoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 29614–29620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collier, R.J.; Beede, D.K.; Thatcher, W.W.; Israel, L.A.; Wilcox, C.J. Influences of environment and its modification on dairy animal health and production. J. Dairy Sci. 1982, 65, 2213–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foizik, K.; Langan, E.A.; Paus, R. Prolactin and the skin: A dermatological perspective on an ancient pleiotropic peptide hormone. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2009, 129, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Jonathan, N.; Hugo, E.R.; Brandebourg, T.D.; LaPensee, C.R. Focus on prolactin as a metabolic hormone. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 17, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arumugam, R.; Horowitz, E.; Noland, R.C.; Lu, D.; Fleenor, D.; Freemark, M. Regulation of islet b-cell pyruvate metabolism: Interactions of prolactin, glucose, and dexamethasone. Endocrinology 2010, 149, 5401–5414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Li, S.; Zhai, Y.; Chang, H.; Han, Z. Preliminary Transcriptome Analysis of Long Noncoding RNA in Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Mammary Gland Axis of Dairy Cows under Heat Stress. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, H.A. Hormones, mammary growth, and lactation: A 41-year perspective. J. Dairy Sci. 2000, 83, 874–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacasse, P.; Zhao, X.; Vanacker, N.; Boutinaud, M. Review: Inhibition of prolactin as a management tool in dairy husbandry. Animal 2019, 13, s35–s41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auchtung, T.L. , and G. E. Dahl. Prolactin mediates photoperiodic immune enhancement: Effects of administration of exogenous prolactin on circulating concentrations, receptor expression, and immune function in steers. Biol. Reprod. 2004, 71, 1913–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, J.M.; Frohn, C.; Cziupka, K.; Brockmann, C.; Kirchner, H.; Luhm, J. Prolactin triggers pro-inflammatory immune responses in peripheral immune cells. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 2004, 15, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Díaz, L.; Muñoz, M.D.; González, L.; Lira-Albarrán, S.; Larrea, F.; Méndez, I. Prolactin in the immune system. In Prolactin.G. M. Nagy and B. E. Toth, ed. Intech Open 2013. [CrossRef]

- do Amaral, B.C.; Connor, E.E.; Tao, S.; Hayen, J.; Bubolz, J.; Dahl, G.E. Heat stress abatement during the dry period influences prolactin signaling in lymphocytes. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2010, 38, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- do Amaral, B.C.; Connor, E.E.; Tao, S.; Hayen, M.J.; Bubolz, J.W.; Dahl, G.E. Heat stress abatement during the dry period influences metabolic gene expression and improves immune status in the transition period of dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marins, N.T.; Gao, J.; Yang, Q.; Binda, R.M.; Pessoa, C.M.B.; Rivas, R.M.O.; Garrick, M.; Melo, V.H.L.R.; Chen, Y.; Bernard, J.K.; et al. Impact of heat stress and a feed supplement on hormonal and inflammatory responses of dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 104, 8276–8289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cincovic, M.R.; Belic, B.; Toholj, B.; Potkonjak, A.; Stevancevic, M.; Lako, B.; Radovic, I. Metabolic acclimation to heat stress in farm housed Holstein cows with different body condition scores. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 10293–10303. [Google Scholar]

- Mezzetti, M.; Bionaz, M.; Trevisi, E. Interaction between inflammation and metabolism in periparturient dairy cows. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 98, S155–S174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Chen, L.; Huang, D.; Peng, Z.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, G. Elevated apoptosis in the liver of dairy cows with ketosis. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 43, 568–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ding, H.Y.; Wang, X.C.; Feng, S.B.; Li, X.B.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.W. An association between the level of oxidative stress and the concentrations of NEFA and BHBA in the plasma of ketotic dairy cows. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2016, 100, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Season | Number of records | Statistics | |||

| x ± Se | SD | min | max | ||

| Average air temperature, ºC | |||||

| Spring | 82 | 12,28 ± 0,79 | 7,15 | -1,10 | 23,8 |

| Summer | 92 | 24,27 ± 0,25 | 2,40 | 18,0 | 28,6 |

| Autumn | 90 | 14,80 ± 0,52 | 4,95 | 4,70 | 24,9 |

| Winter | 90 | 4,84 ± 0,36 | 3,42 | -4,0 | 12,7 |

| Average maximum air temperatures | |||||

| Spring | 82 | 18,75 ± 0,95 | 8,64 | 1,5 | 32,4 |

| Summer | 92 | 30,89 ± 0,38 | 3,65 | 20,7 | 38,6 |

| Autumn | 90 | 21,51 ± 0,65 | 6,13 | 6,10 | 35,9 |

| Winter | 90 | 9,48 ± 0,47 | 4,44 | -0,60 | 21,10 |

| Average air humidity, % | |||||

| Spring | 82 | 66,32 ± 1,35 | 12,22 | 33 | 96 |

| Summer | 92 | 63,21 ± 1,12 | 10,70 | 45 | 93 |

| Autumn | 90 | 69,16 ± 1,20 | 11,38 | 50 | 96 |

| Winter | 90 | 77,00 ± 1,37 | 12,99 | 46 | 97 |

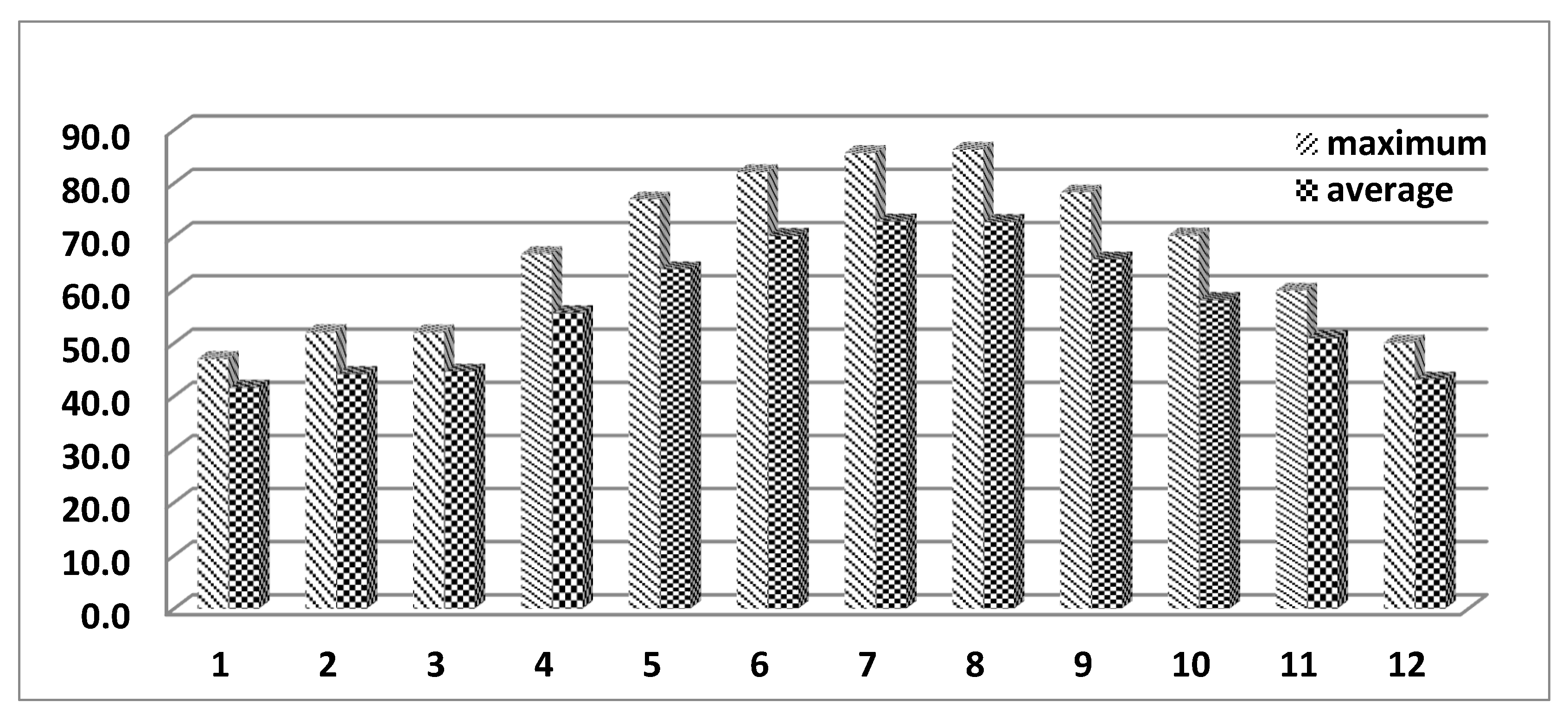

| Average THI values | |||||

| Spring | 82 | 54,54 ± 1,89 | 10,77 | 34,36 | 71,74 |

| Summer | 92 | 71,78 ± 0,30 | 2,89 | 64,15 | 76,96 |

| Autumn | 90 | 58,23 ± 0,80 | 7,55 | 41,29 | 72,52 |

| Winter | 90 | 42,91 ± 0,56 | 5,36 | 30,97 | 55,37 |

| Average maximum THI values | |||||

| Spring | 82 | 65,01 ± 1,59 | 14,40 | 36,76 | 89,24 |

| Summer | 92 | 84,78 ± 0,58 | 5,55 | 69,07 | 94,97 |

| Autumn | 90 | 69,41 ± 1,07 | 10,17 | 43,31 | 91,85 |

| Winter | 90 | 49,62 ± 0,79 | 7,53 | 32,41 | 69,71 |

| Average values for THI | Study March | Study July | Study November | |||

| February | March | June | July | October | November | |

| Daily | 44,17±0,87 | 44,63±1,39 | 70,09±0,50 | 72,81±0,48 | 58,07±0,65 | 50,95±0,97 |

| MAX | 52,02±1,30 | 52,01±1,98 | 82,04±0,96 | 85,64±1,04 | 70,18±0,74 | 59,81±1,61 |

| MIN | 38,22±0,77 | 39,38±0,84 | 60,78±0,49 | 62,33±0,40 | 49,98±0,76 | 44,95±0,81 |

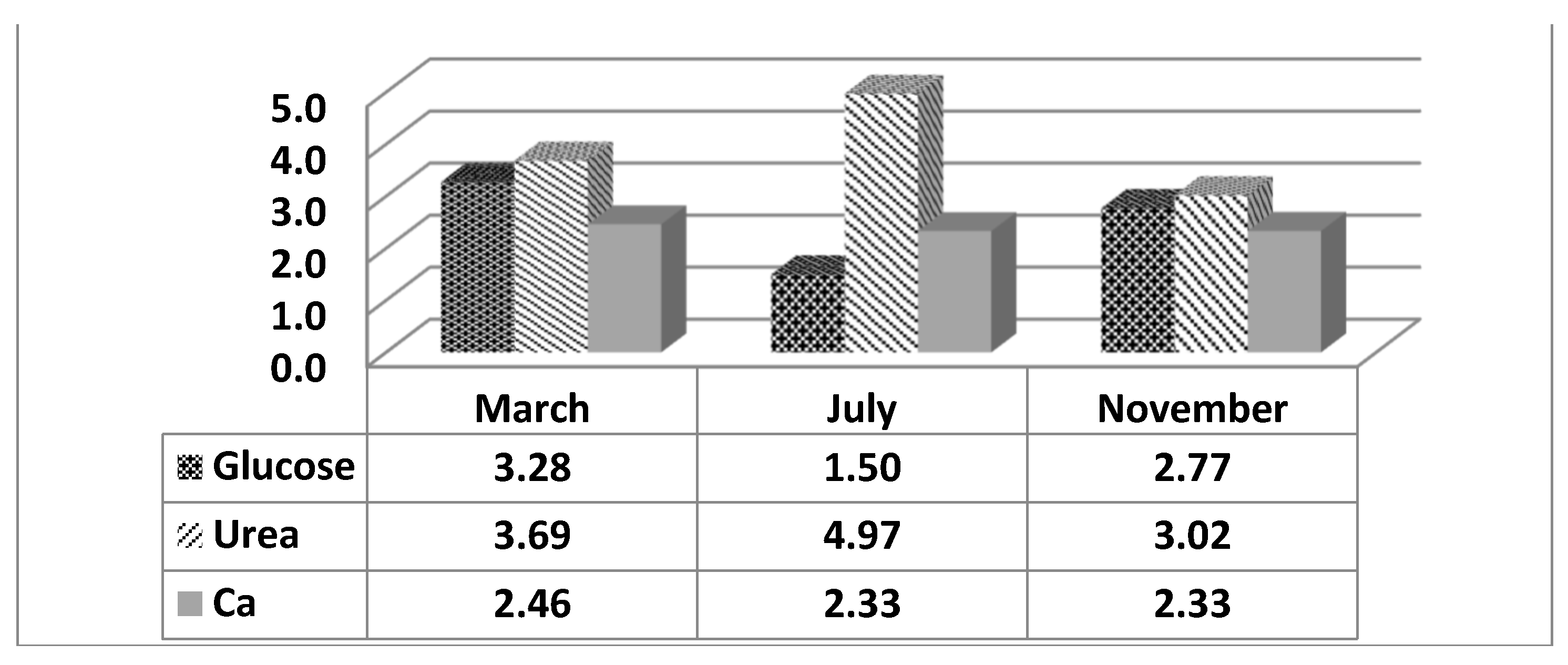

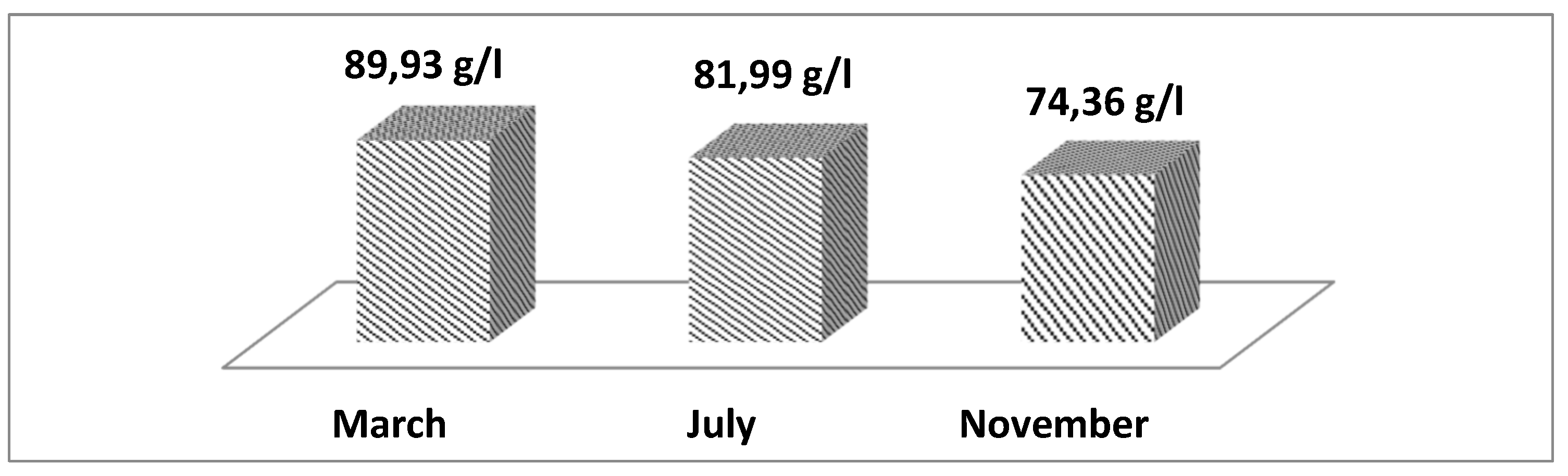

| Biochemical indicator | Reference ranges | Variational statistical indicators | |||

| x ± Se | SD | MIN | MAX | ||

| Glucose | 2-3 (mmol/l) | 2,51 ± 0,091 | 0,865 | 0,52 | 3,84 |

| Triglycerides | 0,2-0,5 (mmol/l) | 0,09 ± 0,003 | 0,030 | 0,03 | 0,20 |

| Urea | 2,8-8,5 (mmol/l) | 3,89 ± 0,126 | 1,187 | 1,83 | 7,45 |

| Total protein | 65-80 (g/l) | 82,11 ± 1,058 | 9,986 | 59,73 | 105,53 |

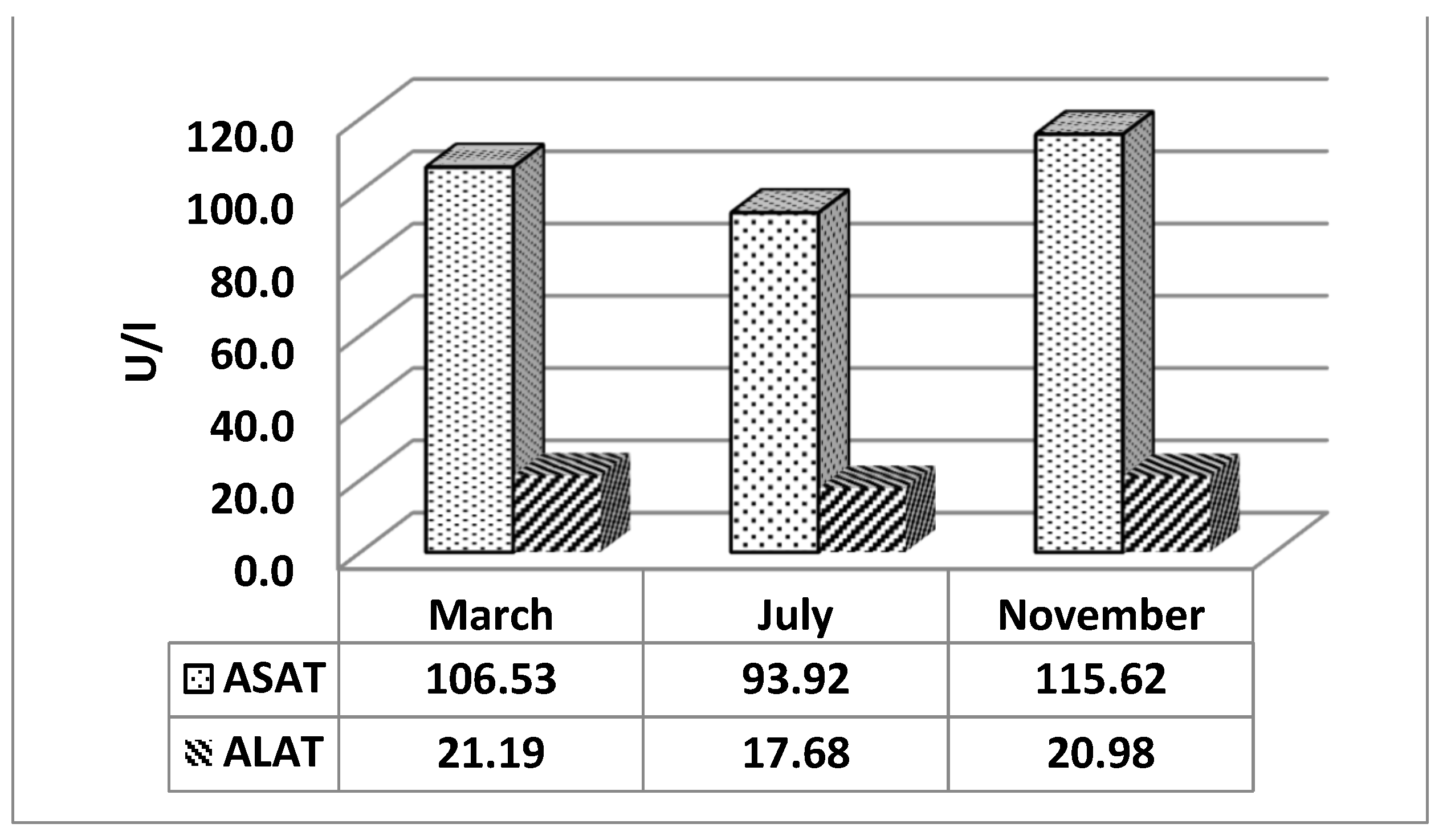

| Asat | 45-110 (U/I) | 104,83 ± 3,704 | 34,941 | 8,13 | 249,04 |

| Alat | 7-35 (U/I) | 19,87 ± 0,661 | 6,234 | 8,55 | 38,47 |

| GGT | 4,9-26 (U/I) | 32,61 ± 2,471 | 23,314 | 6,20 | 171,90 |

| Alkaline posphatase | 18-153 (U/I) | 63,05 ± 2,835 | 26,744 | 2,50 | 186,70 |

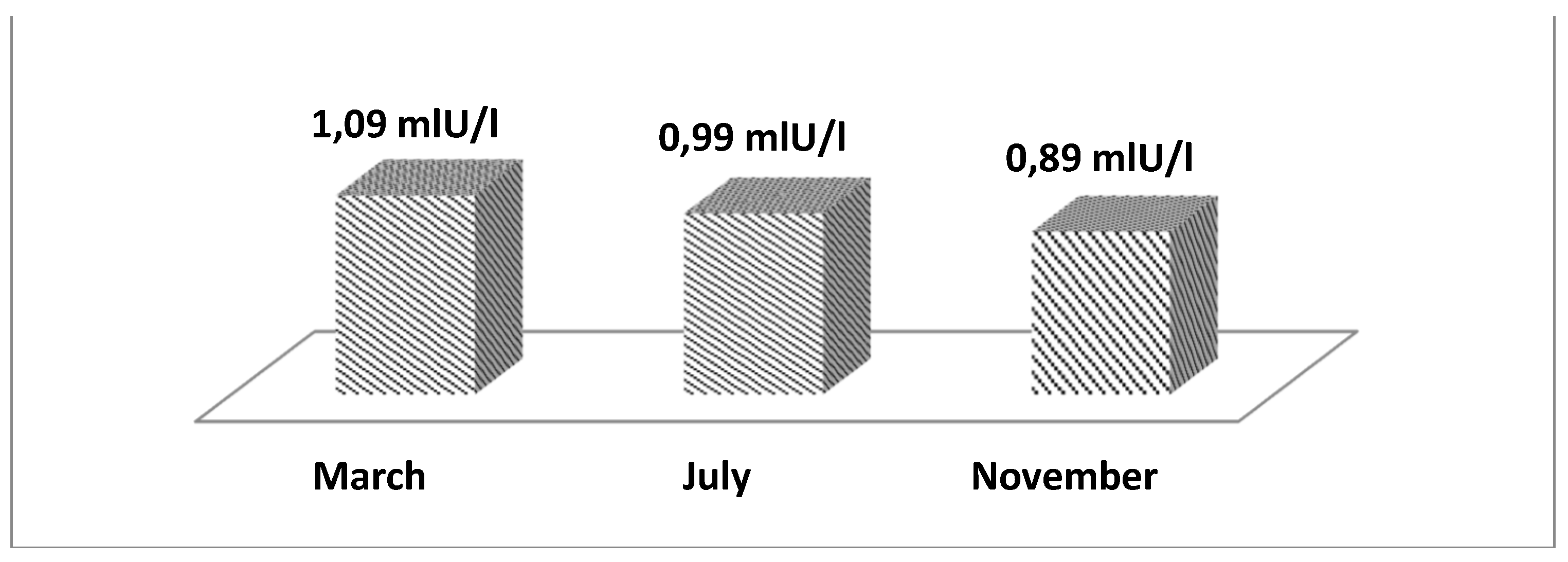

| Prolactin | - | 1,01 ± 0,026 | 0,241 | 0,80 | 3,10 |

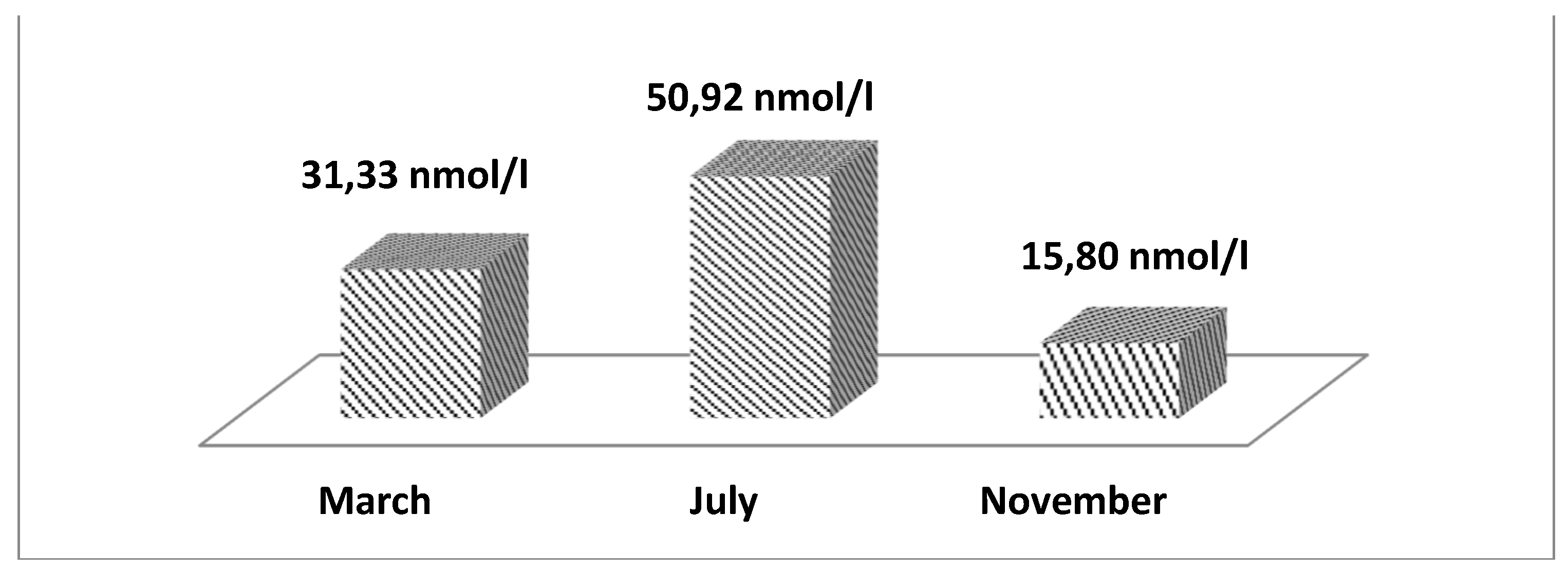

| Cortisol | 40-50 (nmol/l) | 32,90 ± 2,839 | 26,790 | 2,10 | 129,50 |

| P | 1,52-2,25 (mmol/l) | 2,99 ± 1,125 | 10,616 | 1,19 | 10,20 |

| Ca | 2.3-3.2 (mmol/l) | 2,37 ± 0,014 | 0,128 | 2,00 | 2,66 |

| Biochemical indicator | Overall for the model | Sample month | Number of lactation | Error | |||

| MS | F P | MS | F P | MS | F P | MS | |

| Glucose | 12,47 | 65,73*** | 24,92 | 131,36*** | 0,19 | 1,01 | 0,190 |

| Triglycerides | 0,0006 | 0,67 | 0,0004 | 0,49 | 0,0008 | 0,86 | 0,001 |

| Urea | 14,75 | 19,03*** | 28,87 | 47,30*** | 1,37 | 1,76 | 0,774 |

| Total protein | 970,50 | 16,66*** | 1786,0 | 30,66*** | 170,0 | 2,92 | 58,2 |

| Asat | 4021,3 | 3,70** | 3484,9 | 3,20* | 4219,8 | 3,88* | 1087,6 |

| Alat | 133,18 | 3,87** | 115,0 | 3,45* | 131,69 | 3,83* | 34,38 |

| GGT | 1421,34 | 2,83* | 768,83 | 1,53 | 1830,1 | 3,85* | 501,84 |

| Alkaline posphatase | 617,44 | 0,78 | 612,3 | 0,75 | 654,5 | 0,91 | 718,9 |

| Prolactin | 0,012 | 9,62*** | 0,089 | 68,78*** | 0,003 | 1,93* | 0,002 |

| Cortisol | 5139,82 | 10,14*** | 9082,6 | 17,91*** | 712,34 | 1,40 | 597,13 |

| P | 0,039 | 0,654 | 0,061 | 1,03 | 0,022 | 0,37 | 0,059 |

| Ca | 0,102 | 8,37*** | 0,166 | 13,48*** | 0,038 | 3,08 | 0,012 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).