Submitted:

19 June 2024

Posted:

20 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

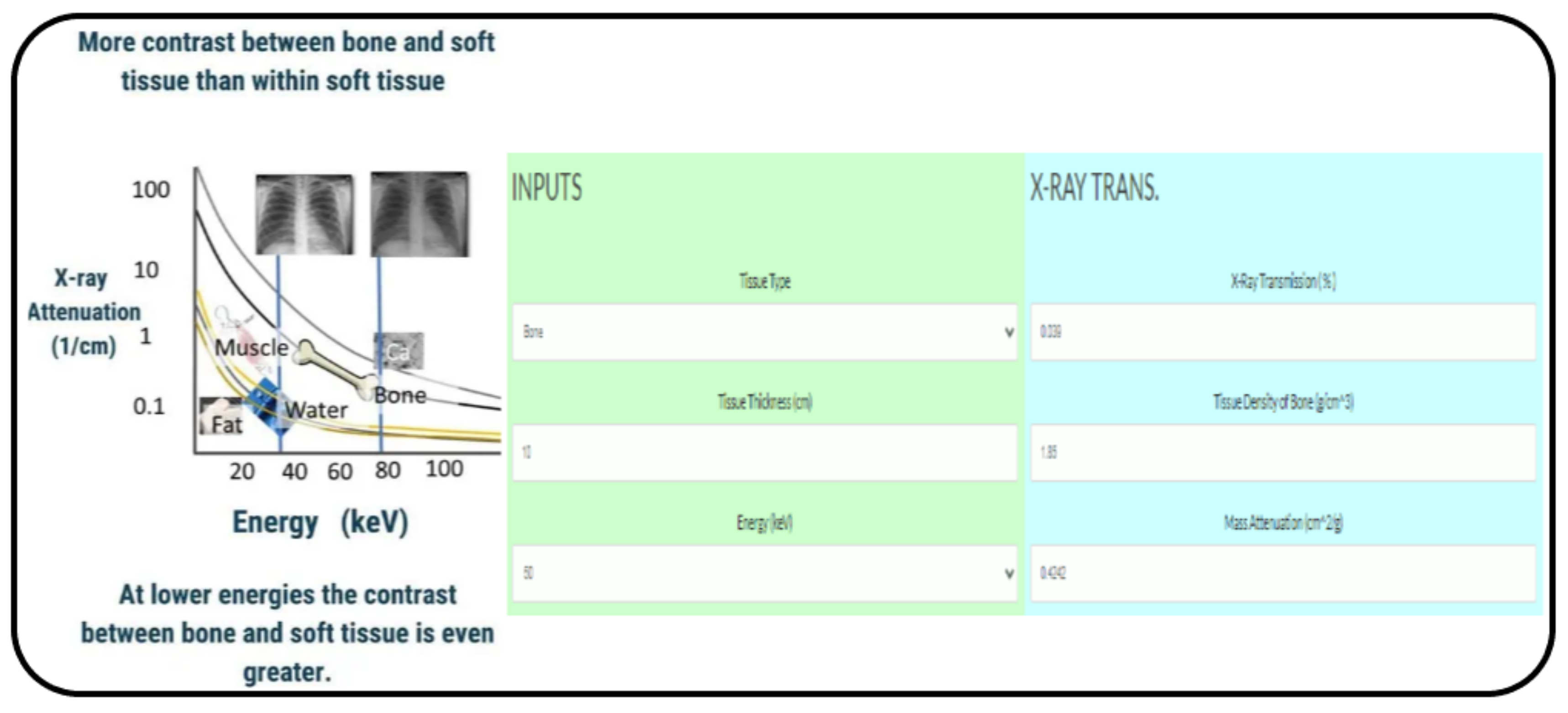

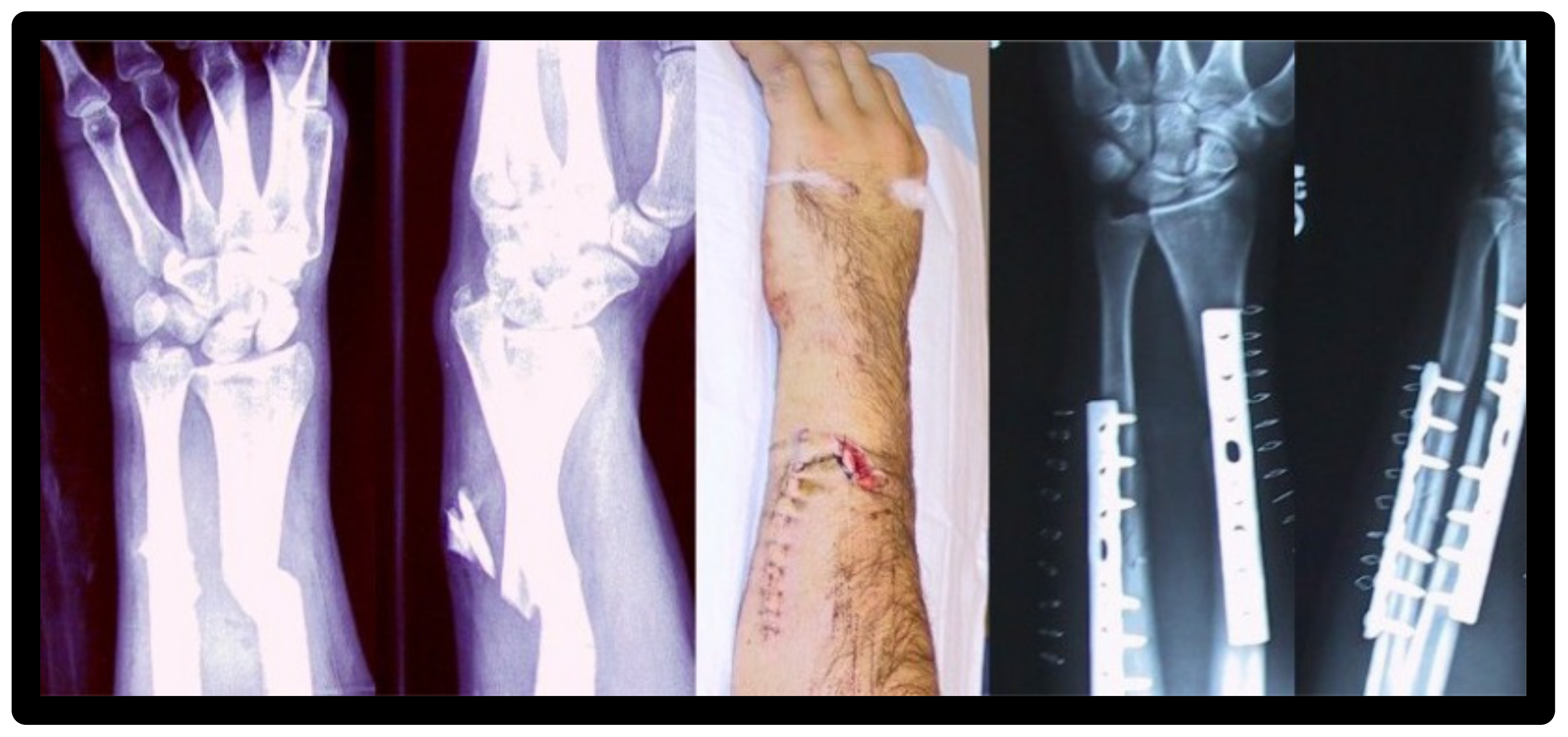

2. Principles and Effects of Radiopacity

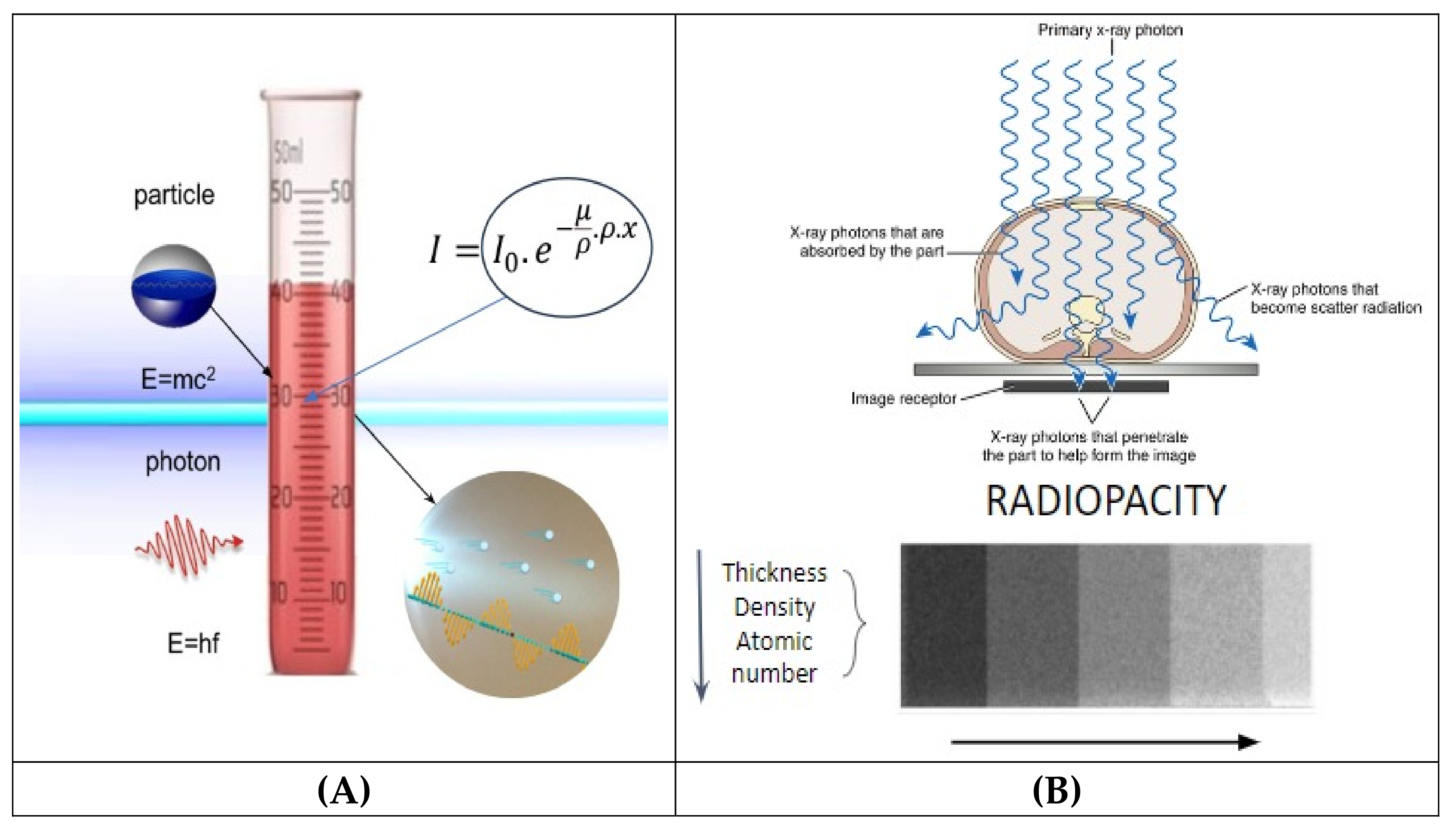

2.1. Beer and Beer-Lambert Law

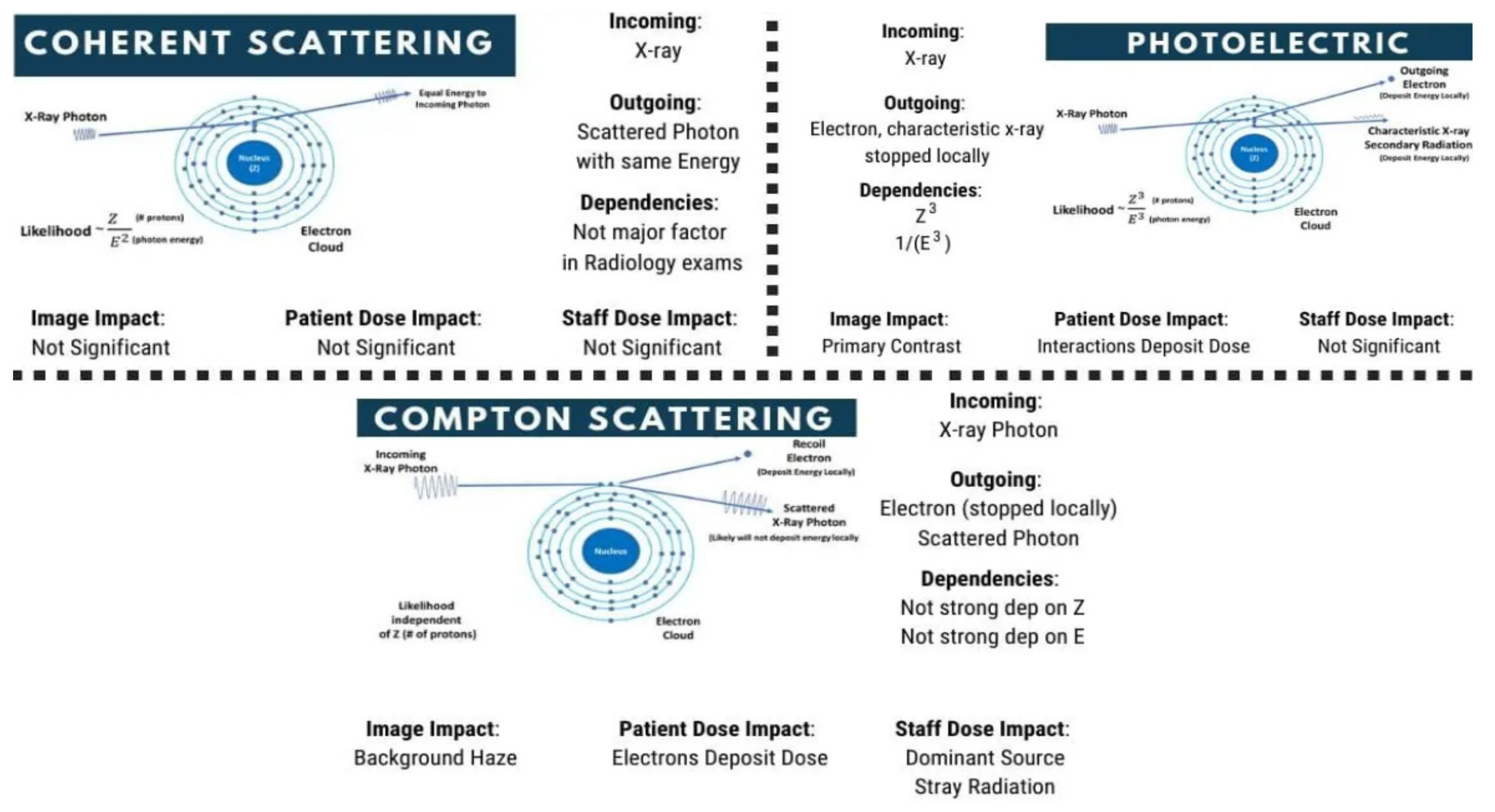

2.2. Photoelectric, Compton, and Rayleigh Effects

2.3. Radiopacity Measurement

3. Biomedical Applications of NPs

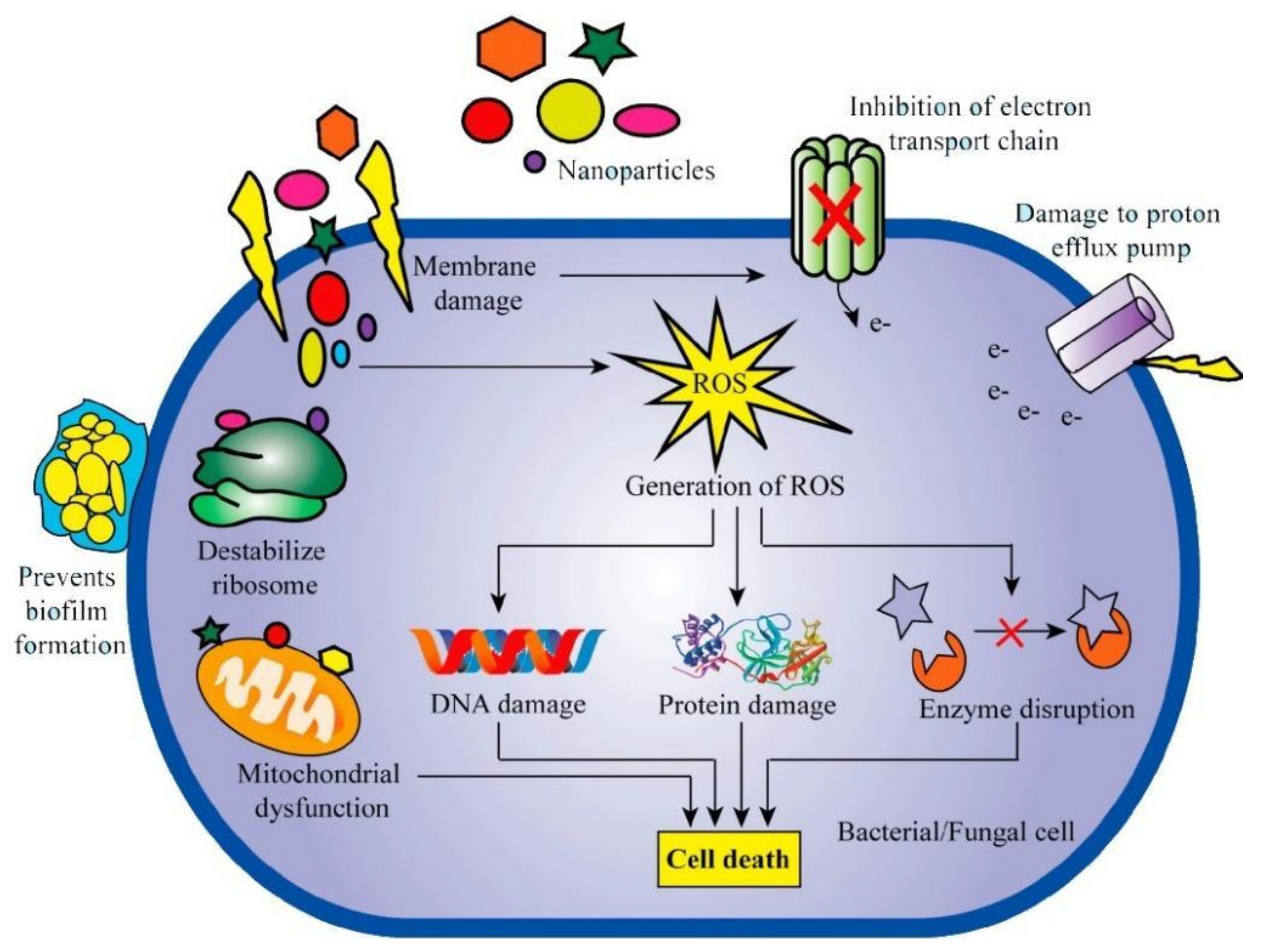

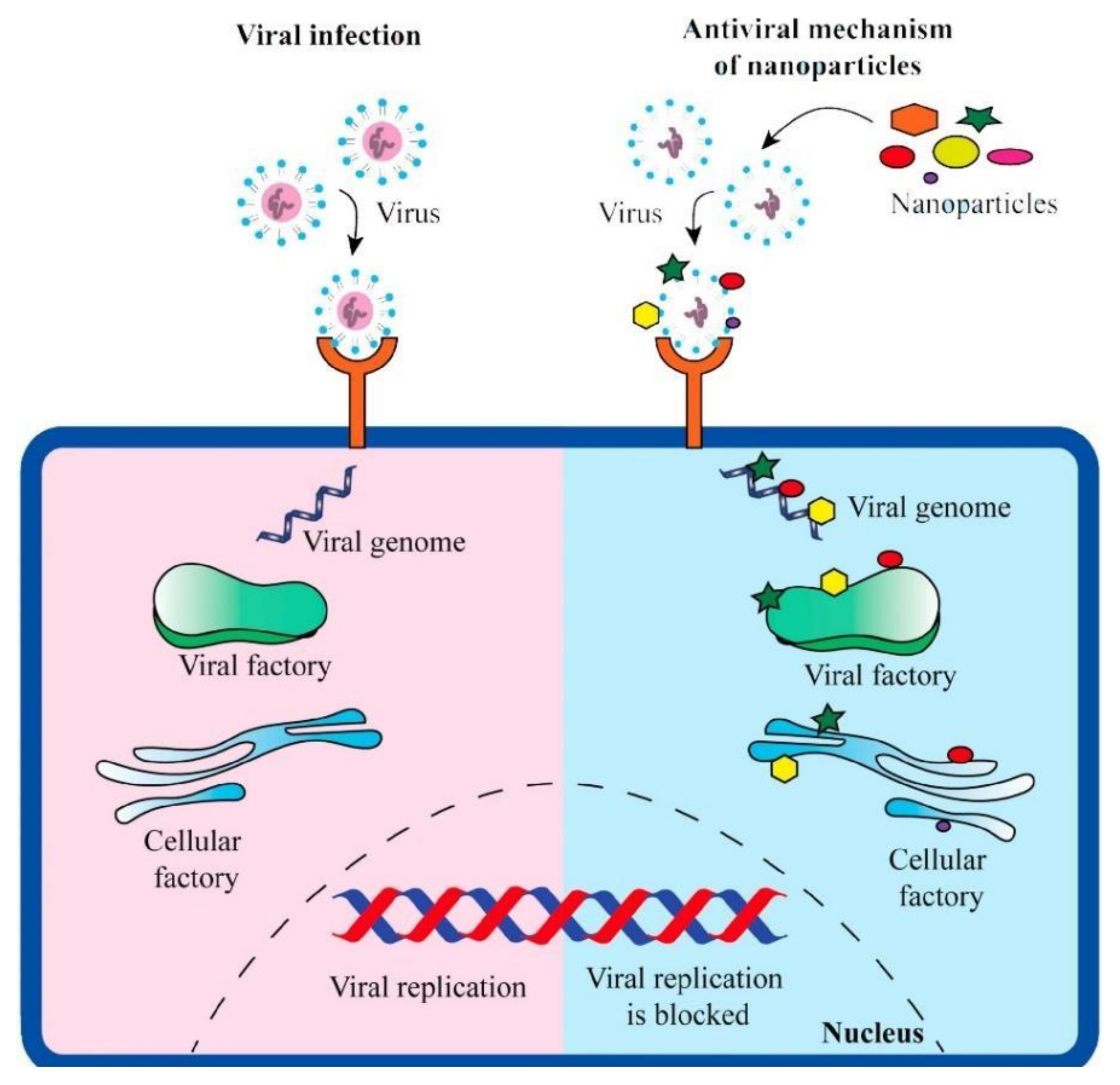

3.1. Antimicrobial Activity of Metallic and Ceramic Nanoparticles and the Influence of Their Particle Characteristics

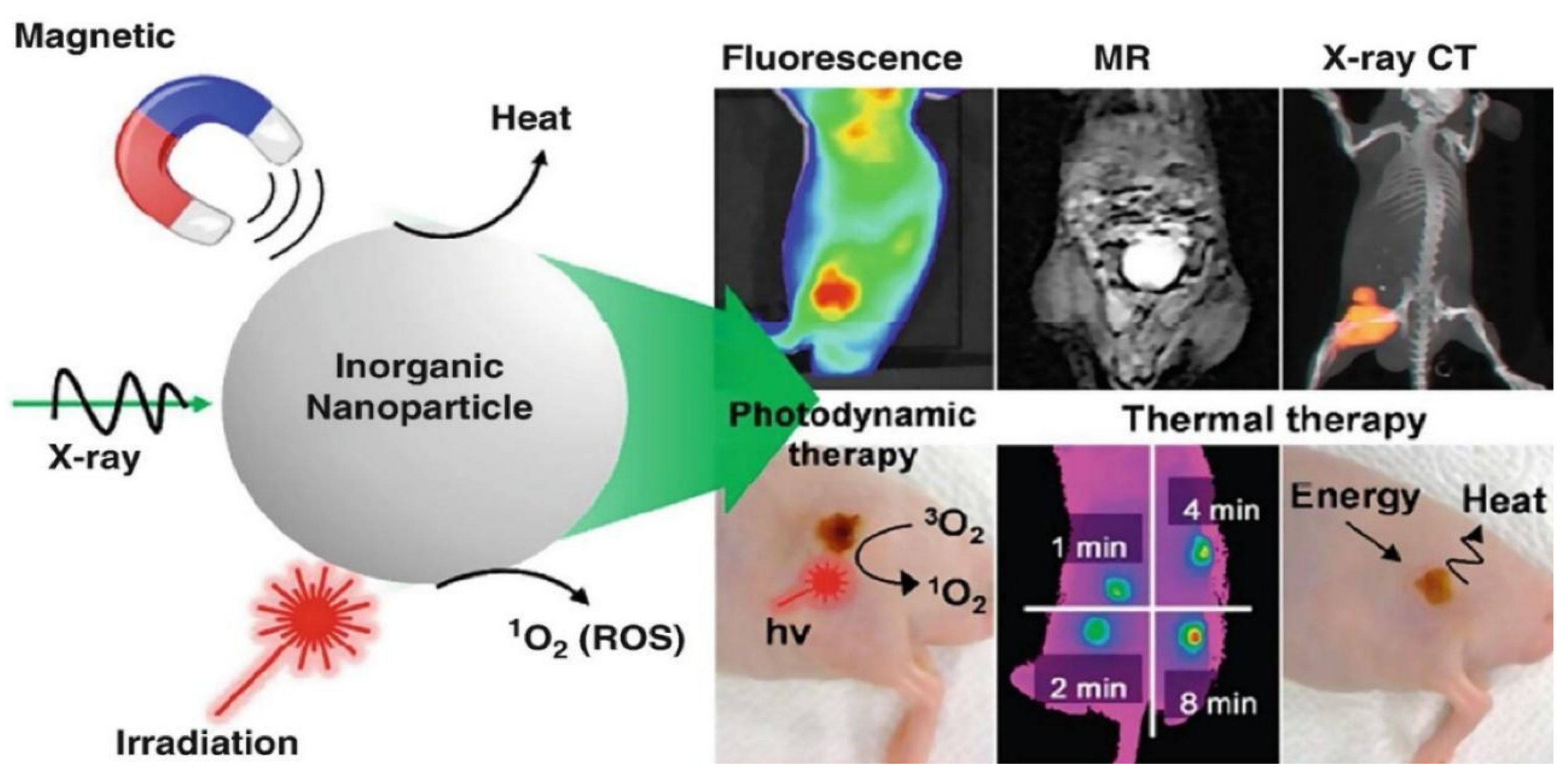

3.2. Metallic Nanomaterials Characteristics on Bio-Imaging and Its Effects

4. Polymers with Intrinsic Radiopacity

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Das, A.; Mahanwar, P. A Brief Discussion on Advances in Polyurethane Applications. Advanced Industrial and Engineering Polymer Research 2020, 3 (3). [CrossRef]

- Wienen, D.; Gries, T.; Cooper, S.L.; Heath, D.E. An Overview of Polyurethane Biomaterials and Their Use in Drug Delivery. Journal of Controlled Release 2023, 363, 376–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas Dall Agnol; Heitor Luiz Ornaghi; Monticeli, F.; Trindade, F.; Bianchi, O. Polyurethanes Synthetized with Polyols of Distinct Molar Masses: Use of the Artificial Neural Network for Prediction of Degree of Polymerization. SPE transactions/Polymer engineering and science 2021, 61 (6), 1810–1818. [CrossRef]

- Alves, F.C.; Vanessa; Monticeli, F.M.; Heitor Ornaghi; Barud, S.; Mulinari, D.R. Efficiency of Castor Oil–Based Polyurethane Foams for Oil Sorption S10 and S500: Influence of Porous Size and Statistical Analysis. Polymers and polymer composites/Polymers & polymer composites 2021, 29 (9_suppl), S1063–S1074. [CrossRef]

- Biobased Polyurethanes for Biomedical Applications. Bioactive Materials 2021, 6(4), 1083–1106. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trhlíková, O.; Vlčková, V.; Abbrent, S.; Valešová, K.; Kanizsová, L.; Skleničková, K.; Paruzel, A.; Bujok, S.; Walterová, Z.; Innemanová, P.; et al. Microbial and Abiotic Degradation of Fully Aliphatic Polyurethane Foam Suitable for Biotechnologies. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2021, 194, 109764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specialty Chemicals—The Lubrizol Corporation. Lubrizol.com. Available online: https://www.lubrizol.com/ (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Medical Polyurethanes. @Biomedical. Available online: https://www.dsm.com/biomedical/en_US/biomaterials-solutions/medical-polyurethanes.html (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Medical Polyurethane Market Research Report: Market size, Industry outlook, Market Forecast, Demand Analysis, Market Share, Market Report 2021-2026. www.industryarc.com. Available online: https://www.industryarc.com/Report/18850/medical-polyurethane-market (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Calloway, D. Beer-Lambert Law. Journal of Chemical Education 1997, 74(7), 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-L. Electromagnetic Fields, Size, and Copy of a Single Photon. arXiv (Cornell University) 2016. [CrossRef]

- Facebook, N. Interactive X-Ray Transmission Calculator For Radiologic Technologists (Beer’s Law Equation) • How Radiology Works. Available online: https://howradiologyworks.com/x-ray-transmission (accessed on 19 January 2024).

- Gaillard, F.; Goel, A. Photoelectric Effect. Radiopaedia.org 2014. [CrossRef]

- Maziar Montazerian; Geovanna, V. S. Gonçalves; Maria; Eunice; Glauber; Sousa, J.A.; Adrine Malek Khachatourian; Souza, S.; Silva; Marcus; Baino, F. Radiopaque Crystalline, Non-Crystalline and Nanostructured Bioceramics. Materials 2022, 15 (21), 7477–7477. [CrossRef]

- Nett, B. X-Ray Interactions, Illustrated Summary (Photoelectric, Compton, Coherent) For Radiologic Technologists And Radiographers • How Radiology Works. How Radiology Works. Available online: https://howradiologyworks.com/x-ray-interactions/ (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Berger, M.; Yang, Q.; Maier, A. X-Ray Imaging. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 2018, 119–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nett, B. PhD. X-ray attenuation of tissues for Radiologic Technologists. How Radiology Works. Available online: https://howradiologyworks.com/x-ray-attenuation-of-tissues/ (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- J. Seibert, J. Anthony; Boone, John, M. X-Ray Imaging Physics for Nuclear Medicine Technologists. Part 2: X-Ray Interactions and Image Formation; Issue 1; Journal of Nuclear Medicine Technology; 1850 Samuel Morse Drive, Reston, VA 20190, USA, March 2005; Vol. 33, pp. 3-18.

- Victor Manuel Ochoa-Rodríguez; Homero, J.; Roma, B.; Hernán Coaguila-Llerena; Mário Tanomaru-Filho; Andréa Gonçalves; Rubens Spin-Neto; Faria, G. Radiopacity of Endodontic Materials Using Two Models for Conversion to Millimeters of Aluminum. Brazilian Oral Research 2020, 34. [CrossRef]

- Crystal Kayaro Emonde; Eggers, M.-E.; Wichmann, M.; Christof Hurschler; Ettinger, M.; Berend Denkena. Radiopacity Enhancements in Polymeric Implant Biomaterials: A Comprehensive Literature Review. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2024. [CrossRef]

- Solmaz Valizadeh; Mohammad Amin Tavakoli; Zarabian, T.; Esmaeili, F. Diagnostic Accuracy of Digitized Conventional Radiographs by Camera and Scanner in Detection of Proximal Caries. PubMed 2009. [CrossRef]

- Paiva, M.A.A. de; Mangueira Leite, D.F.B.; Farias, I.A.P.; Costa, A. de P. C.; Sampaio, F.C. Dental Anatomical Features and Caries: A Relationship to Be Investigated. Dental Anatomy 2017. [CrossRef]

- Bryant, J.A.; Drage, N.A.; Richmond, S. CT Number Definition. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 2012, 81(4), 358–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneha, K.R.; Sailaja, G.S. Intrinsically Radiopaque Biomaterial Assortments: A Short Review on the Physical Principles, X-Ray Imageability, and State-of-The-Art Developments. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2021, 9(41), 8569–8593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusic, H.; Grinstaff, M.W. X-Ray-Computed Tomography Contrast Agents. Chemical Reviews 2012, 113(3), 1641–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, M.J.; Billingsley, M.M.; Haley, R.M.; Wechsler, M.E.; Peppas, N.A.; Langer, R. Engineering Precision Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2020, 20(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Potocny, A.M.; Rosenthal, J.; Day, E.S. Gold Nanoshell-Linear Tetrapyrrole Conjugates for near Infrared-Activated Dual Photodynamic and Photothermal Therapies. ACS Omega 2019, 5(1), 926–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laxminarayan, R.; Duse, A.; Wattal, C.; Zaidi, A.K.M.; Wertheim, H.F.L.; Sumpradit, N.; Vlieghe, E.; Hara, G.L.; Gould, I.M.; Goossens, H.; et al. Antibiotic Resistance—the Need for Global Solutions. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2013, 13(12), 1057–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, H.; Newton, C.; Klein, T.W. Microbial Infections, Immunomodulation, and Drugs of Abuse. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2003, 16(2), 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, I.; Saeed, K.; Khan, I. Nanoparticles: Properties, Applications and Toxicities. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2017, 12(7), 908–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Bayati, P.; Gupta, M.; Elahinia, M.; Haghshenas, M. Fracture of Magnesium Matrix Nanocomposites—a Review. International Journal of Lightweight Materials and Manufacture 2021, 4(1), 67–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vert, M.; Doi, Y.; Hellwich, K.-H.; Hess, M.; Hodge, P.; Kubisa, P.; Rinaudo, M.; Schué, F. Terminology for Biorelated Polymers and Applications (IUPAC Recommendations 2012). Pure and Applied Chemistry 2012, 84(2), 377–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-López, E.; Gomes, D.; Esteruelas, G.; Bonilla, L.; Lopez-Machado, A.L.; Galindo, R.; Cano, A.; Espina, M.; Ettcheto, M.; Camins, A.; et al. Metal-Based Nanoparticles as Antimicrobial Agents: An Overview. Nanomaterials 2020, 10 (2). [CrossRef]

- Sharmin, S.; Md Rahaman, M.; Sarkar, C.; Atolani, O.; Islam, M.T.; Adeyemi, O.S. Nanoparticles as Antimicrobial and Antiviral Agents: A Literature-Based Perspective Study. Heliyon 2021, 7(3), e06456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanoscale Materials in Targeted Drug Delivery, Theragnosis and Tissue Regeneration; Springer Nature, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Castañón, G.A.; Niño-Martínez, N.; Martínez-Gutierrez, F.; Martínez-Mendoza, J.R.; Ruiz, F. Synthesis and Antibacterial Activity of Silver Nanoparticles with Different Sizes. Journal of Nanoparticle Research 2008, 10(8), 1343–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manikandan, V.; Velmurugan, P.; Park, J.-H.; Chang, W.-S.; Park, Y.-J.; Jayanthi, P.; Cho, M.; Oh, B.-T. Green Synthesis of Silver Oxide Nanoparticles and Its Antibacterial Activity against Dental Pathogens. 3 Biotech 2017, 7 (1). [CrossRef]

- Bera, R.K.; Mandal, S.M.; Raj, C.R. Antimicrobial Activity of Fluorescent Ag Nanoparticles. Letters in Applied Microbiology 2014, 58(6), 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panáček, A.; Kolář, M.; Večeřová, R.; Prucek, R.; Soukupová, J.; Kryštof, V.; Hamal, P.; Zbořil, R.; Kvítek, L. Antifungal Activity of Silver Nanoparticles against Candida Spp. Biomaterials 2009, 30(31), 6333–6340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lara, H.H.; Ayala-Nuñez, N.V.; Ixtepan-Turrent, L.; Rodriguez-Padilla, C. Mode of Antiviral Action of Silver Nanoparticles against HIV-1. Journal of nanobiotechnology 2010, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, Y.; Ono, T.; Miyahira, Y.; Nguyen, V.Q.; Matsui, T.; Ishihara, M. Antiviral Activity of Silver Nanoparticle/Chitosan Composites against H1N1 Influenza a Virus. Nanoscale Research Letters 2013, 8 (1). [CrossRef]

- Haggag, E.; Elshamy, A.; Rabeh, M.; Gabr, N.; Salem, M.; Youssif, K.; Samir, A.; Bin Muhsinah, A.; Alsayari, A.; Abdelmohsen, U.R. Antiviral Potential of Green Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles of Lampranthus Coccineus and Malephora Lutea. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2019, Volume 14, 6217–6229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanhed, P.; Birla, S.; Gaikwad, S.; Gade, A.; Seabra, A.B.; Rubilar, O.; Duran, N.; Rai, M. In Vitro Antifungal Efficacy of Copper Nanoparticles against Selected Crop Pathogenic Fungi. Materials Letters 2014, 115, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, X.; Peng, H.; Song, H.; Qi, Z.; Miao, X.; Xu, W. Antiviral Activity of Cuprous Oxide Nanoparticles against Hepatitis c Virus in Vitro. Journal of Virological Methods 2015, 222, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shionoiri, N.; Sato, T.; Fujimori, Y.; Nakayama, T.; Nemoto, M.; Matsunaga, T.; Tanaka, T. Investigation of the Antiviral Properties of Copper Iodide Nanoparticles against Feline Calicivirus. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering 2012, 113(5), 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamady Hussein, M.A.; Baños, F.G.D.; Grinholc, M.; Abo Dena, A.S.; El-Sherbiny, I.M.; Megahed, M. Exploring the Physicochemical and Antimicrobial Properties of Gold-Chitosan Hybrid Nanoparticles Composed of Varying Chitosan Amounts. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 162, 1760–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wani, I.A.; Ahmad, T. Size and Shape Dependant Antifungal Activity of Gold Nanoparticles: A Case Study of Candida. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2013, 101, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayakumar, S.; Ganesan, S. Gold Nanoparticles as an HIV Entry Inhibitor. Current HIV Research 2012, 10(8), 643–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; He, Y.; Irwin, P.L.; Jin, T.; Shi, X. Antibacterial Activity and Mechanism of Action of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles AgainstCampylobacter Jejuni. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2011, 77(7), 2325–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Liu, Y.; Mustapha, A.; Lin, M. Antifungal Activity of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles against Botrytis Cinerea and Penicillium Expansum. Microbiological Research 2011, 166(3), 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Using Flower Extract of Nyctanthes Arbor-Tristis and Their Antifungal Activity. Journal of King Saud University—Science 2018, 30 (2), 168–175. [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, H.; Tavakoli, A.; Moradi, A.; Tabarraei, A.; Bokharaei-Salim, F.; Zahmatkeshan, M.; Farahmand, M.; Javanmard, D.; Kiani, S.J.; Esghaei, M.; et al. Inhibition of H1N1 Influenza Virus Infection by Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: Another Emerging Application of Nanomedicine. Journal of Biomedical Science 2019, 26 (1). [CrossRef]

- Mahdy, Saba A.; Qusay Jaffer Raheed; P. T. Kalaichelvan, Antimicrobial activity of zero-valent iron nanoparticles; Issue.1; International Journal of Modern Engineering Research; Jan-Feb 2012, Vol.2, pp. 578-581.

- Ismail, R.A.; Sulaiman, G.M.; Abdulrahman, S.A.; Marzoog, T.R. Antibacterial Activity of Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Synthesized by Laser Ablation in Liquid. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2015, 53, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parveen, S.; Wani, A.H.; Shah, M.A.; Devi, H.S.; Bhat, M.Y.; Koka, J.A. Preparation, Characterization and Antifungal Activity of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Microbial Pathogenesis 2018, 115, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Nayak, M.; Sahoo, G.C.; Pandey, K.; Sarkar, M.C.; Ansari, Y.; Das, V.N.R.; Topno, R.K.; Bhawna; Madhukar, M.; Das, P. Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Based Antiviral Activity of H1N1 Influenza a Virus. Journal of Infection and Chemotherapy 2019, 25 (5), 325–329. [CrossRef]

- Haghighi, Farnoosh; S. Roudbar, Mohammadi et al. Antifungal activity of TiO2 nanoparticles and EDTA on Candida albicans biofilms; n.1; Infection, Epidemiology and Microbiology, ; 2013; Volume 1, pp. 33-38.

- Webster, T.J.; Stout; Aninwene II, G.E.; Yang. Nano-BaSO4: A Novel Antimicrobial Additive to Pellethane. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2013, 1197. [CrossRef]

- Gurunathan, S.; Han, J.W.; Kwon, D.-N.; Kim, J.-H. Enhanced Antibacterial and Anti-Biofilm Activities of Silver Nanoparticles against Gram-Negative and Gram-Positive Bacteria. Nanoscale Research Letters 2014, 9 (1). [CrossRef]

- Ing, L.Y.; Zin, N.M.; Sarwar, A.; Katas, H. Antifungal Activity of Chitosan Nanoparticles and Correlation with Their Physical Properties. International Journal of Biomaterials 2012, 2012, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhosale, S.V.; P.S. Ekambe; Bhoraskar, S.V.; Mathe, V.L. Effect of Surface Properties of NiFe2O4 Nanoparticles Synthesized by Dc Thermal Plasma Route on Antimicrobial Activity. 2018, 441, 724–733. [CrossRef]

- PREPARATION of BIO-NEMATICIDAL NANOPARTICLES of EUCALYPTUS OFFICINALIS for the CONTROL of CYST NEMATODE (HETERODERA SACCHARI). The Journal of Animal and Plant Sciences 2020, 30 (5). [CrossRef]

- Philip, D. Green Synthesis of Gold and Silver Nanoparticles Using Hibiscus Rosa Sinensis. Physica E: Low-dimensional Systems and Nanostructures 2010, 42 (5), 1417–1424. [CrossRef]

- Cha, S.-H.; Hong, J.; McGuffie, M.; Yeom, B.; VanEpps, J.S.; Kotov, N.A. Shape-Dependent Biomimetic Inhibition of Enzyme by Nanoparticles and Their Antibacterial Activity. ACS Nano 2015, 9(9), 9097–9105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias, L.; Pessan, J.; Vieira, A.; Lima, T.; Delbem, A.; Monteiro, D. Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications: A Perspective on Synthesis, Drugs, Antimicrobial Activity, and Toxicity. Antibiotics 2018, 7(2), 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marghalani, H.Y. Effect of Filler Characteristics on Radiopacity of Experimental Nanocomposite Series. Journal of Adhesion Science and Technology 2018, 32(14), 1599–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyooka, H.; Taira, M.; K. Wakasa; Yamaki, M.; Fujita, M.; Wada, T. Radiopacity of 12 Visible-Light-Cured Dental Composite Resins. Journal of oral rehabilitation 1993, 20 (6), 615–622. [CrossRef]

- Watts, D.C. Radiopacity vs. Composition of Some Barium and Strontium Glass Composites. Journal of Dentistry 1987, 15(1), 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moszner, N.; Klapdohr, S. Nanotechnology for Dental Composites. International Journal of Nanotechnology 2004, 1 (1/2), 130. [CrossRef]

- Beun, S.; Glorieux, T.; Devaux, J.; Vreven, J.; Leloup, G. Characterization of Nanofilled Compared to Universal and Microfilled Composites. Dental Materials 2007, 23(1), 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.-H.; Ong, J.L.; Okuno, O. The Effect of Filler Loading and Morphology on the Mechanical Properties of Contemporary Composites. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 2002, 87(6), 642–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harish, V.; Tewari, D.; Gaur, M.; Yadav, A.B.; Swaroop, S.; Bechelany, M.; Barhoum, A. Review on Nanoparticles and Nanostructured Materials: Bioimaging, Biosensing, Drug Delivery, Tissue Engineering, Antimicrobial, and Agro-Food Applications. Nanomaterials 2022, 12(3), 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, A.; Dierker, C.; Rommel, C.; Hahn, D.; Wohlleben, W.; Schulze-Isfort, C.; Göbbert, C.; Voetz, M.; Hardinghaus, F.; Schnekenburger, J. Cytotoxicity Screening of 23 Engineered Nanomaterials Using a Test Matrix of Ten Cell Lines and Three Different Assays. Particle and Fibre Toxicology 2011, 8 (1). [CrossRef]

- Manshian, B.B.; Jiménez, J.; Himmelreich, U.; Soenen, S.J. Personalized Medicine and Follow-up of Therapeutic Delivery through Exploitation of Quantum Dot Toxicity. Biomaterials 2017, 127, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhim, W.-K.; Kim, M.; Hartman, K.L.; Keon Wook Kang; Nam, J.-M. Radionuclide-Labeled Nanostructures for in Vivo Imaging of Cancer. Nano convergence 2015, 2 (1). [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, C.; Jiang, T.; Ran, G.; Song, Q. Cadmium Induced Aggregation of Orange–Red Emissive Carbon Dots with Enhanced Fluorescence for Intracellular Imaging. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2022, 427, 128092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Yu, X.; Peng, S.; Luo, Y.; Li, J.; Lu, L. Construction of Nanomaterials as Contrast Agents or Probes for Glioma Imaging. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2021, 19(1), 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratiwi, F.W.; Kuo, C.W.; Chen, B.-C.; Chen, P. Recent Advances in the Use of Fluorescent Nanoparticles for Bioimaging. Nanomedicine 2019, 14(13), 1759–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Wang, H.; Hong, Y.; Tang, B.Z. Fabrication of Fluorescent Nanoparticles Based on AIE Luminogens (AIE Dots) and Their Applications in Bioimaging. Materials Horizons 2016, 3(4), 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caponetti, V.; Trzcinski, J.W.; Cantelli, A.; Tavano, R.; Papini, E.; Mancin, F.; Montalti, M. Self-Assembled Biocompatible Fluorescent Nanoparticles for Bioimaging. Frontiers in Chemistry 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Huang, Y.; Huang, P. Graphene-Based Nanomaterials in Bioimaging. Biomedical Applications of Functionalized Nanomaterials 2018, 247–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.; Roy, S.; Singh, P.; Khan, Z.; Jaiswal, A. 2D MoS2 -Based Nanomaterials for Therapeutic, Bioimaging, and Biosensing Applications. Small 2018, 15(1), 1803706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Li, A.; Zhang, A.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, J. Recent Advances in Functional-Polymer-Decorated Transition-Metal Nanomaterials for Bioimaging and Cancer Therapy. ChemMedChem 2018, 13(20), 2134–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, Z.; Luo, Z.; Qin, X.; Chen, Q.; Liu, X. Lanthanide-Activated Nanoparticles: A Toolbox for Bioimaging, Therapeutics, and Neuromodulation. Accounts of Chemical Research 2020, 53(11), 2692–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Li, P.; Cheng, D.; Wu, C.; Lu, Q.; Yang, W.; Zhu, X.; Yin, P.; Liu, M.; Li, H.; et al. Group IV Nanodots: Synthesis, Surface Engineering and Application in Bioimaging and Biotherapy. Journal of materials chemistry. B 2020, 8(45), 10290–10308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmaeili, Y.; Bidram, E.; Zarrabi, A.; Amini, A.; Cheng, C. Graphene Oxide and Its Derivatives as Promising In-Vitro Bio-Imaging Platforms. Scientific Reports 2020, 10 (1). [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Gavel, P.K. Low Molecular Weight Self-Assembling Peptide-Based Materials for Cell Culture, Antimicrobial, Anti-Inflammatory, Wound Healing, Anticancer, Drug Delivery, Bioimaging and 3D Bioprinting Applications. 2020, 16 (44), 10065–10095. [CrossRef]

- Kjellson, F.; Almén, T.; Tanner, K.E.; McCarthy, I.D.; Lidgren, L. Bone Cement X-Ray Contrast Media: A Clinically Relevant Method of Measuring Their Efficacy. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. Part B, Applied Biomaterials 2004, 70 (2), 354–361. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.S.; Diaz, J.; A Sabokbar; N Athanasou; F Kjellson; Tanner, K.E.; McCarthy, I.D.; L Lidgren. In Vitro and in Vivo Biological Responses to a Novel Radiopacifying Agent for Bone Cement. Journal of the Royal Society interface 2005, 2 (2), 71–78. [CrossRef]

- Manero, J.M.; Ginebra, M.P.; Gil, F.J.; Planell, J.A.; Delgado, J.A.; Morejon, L.; Artola, A.; M Gurruchaga; I Goñi. Propagation of Fatigue Cracks in Acrylic Bone Cements Containing Different Radiopaque Agents. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. Part H, Journal of engineering in medicine 2004, 218 (3), 167–172. [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, I.H.; Togawa, D.; Kayanja, M.M. Vertebroplasty and Kyphoplasty: Filler Materials. The Spine Journal 2005, 5(6), S305–S316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pepiol, A.; Teixidor, F.; Saralidze, K.; van der Marel, C.; Willems, P.; Voss, L.; Knetsch, M.L.W.; Vinas, C.; Koole, L.H. A Highly Radiopaque Vertebroplasty Cement Using Tetraiodinated O-Carborane Additive. Biomaterials 2011, 32(27), 6389–6398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitsch, R.G.; Kretzer, J.P.; Vogt, S.; Büchner, H.; Thomsen, M.N.; Lehner, B. Increased Antibiotic Release and Equivalent Biomechanics of a Spacer Cement without Hard Radio Contrast Agents. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease 2015, 83(2), 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas Webster, T.J. Nanofunctionalized Zirconia and Barium Sulfate Particles as Bone Cement Additives. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2009, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-S.; Yim, K.H.; Jeong, S.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, D.G. A Novel High-Visibility Radiopaque Tantalum Marker for Biliary Self-Expandable Metal Stents. Gut and Liver 2019, 13(3), 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, W.A.; Bini, T.B.; Venkatraman, S.S.; Boey, F.Y.C. Effect of Radio-Opaque Filler on Biodegradable Stent Properties. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A 2006, 79A (1), 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung Yoon Choi; Hur, W.; Byeung Kyu Kim; Shasteen, C.; Myung Hun Kim; La Mee Choi; Seung Ho Lee; Chun Gwon Park; Park, M.; Hye Sook Min; Kim, S.; Tae Hyun Choi; Young Bin Choy. Bioabsorbable Bone Fixation Plates for X-Ray Imaging Diagnosis by a Radiopaque Layer of Barium Sulfate and Poly(Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid). Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials 2014, 103 (3), 596–607. [CrossRef]

- Zaribaf, F.P.; Gill, H.S.; Pegg, E.C. Characterisation of the Physical, Chemical and Mechanical Properties of a Radiopaque Polyethylene. Journal of Biomaterials Applications 2020, 35(2), 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Yu, X.; Chen, X.; Gao, J.; Shi, D.; Shen, Y.; Tang, J.; He, J.; Li, A.; Yu, L.; et al. A Facile Composite Strategy to Prepare a Biodegradable Polymer Based Radiopaque Raw Material for “Visualizable” Biomedical Implants. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2022, 14 (21), 24197–24212. [CrossRef]

- Myriam Le Ferrec; Mellier, C.; Florian Boukhechba; Thomas Le Corroller; Daphné Guenoun; Franck Fayon; Valérie Montouillout; Christelle Despas; Alain Walcarius; Massiot, D.; François-Xavier Lefèvre; Robic, C.; Scimeca, J.-C.; Bouler, J.-M.; Bujoli, B. Design and Properties of a Novel Radiopaque Injectable Apatitic Calcium Phosphate Cement, Suitable for Image-Guided Implantation. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials 2017, 106 (8), 2786–2795. [CrossRef]

- Leibundgut, G. A Novel, Radiopaque, Bioresorbable Tyrosine- Derived Polymer for Cardiovascular Scaffolds. Cardiac Interventions Today Europe 2018, 2 (2), pp. 66– 70.

- Dukic, W. Radiopacity of Composite Luting Cements Using a Digital Technique. Journal of Prosthodontics 2017, 28(2), e450–e459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wear Performance of Calcium Carbonate-Containing Knee Spacers. Materials 2017, 10(7), 805. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deb, S.; Abdulghani, S.; Behiri, J.C. Radiopacity in Bone Cements Using an Organo-Bismuth Compound. Biomaterials 2002, 23(16), 3387–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

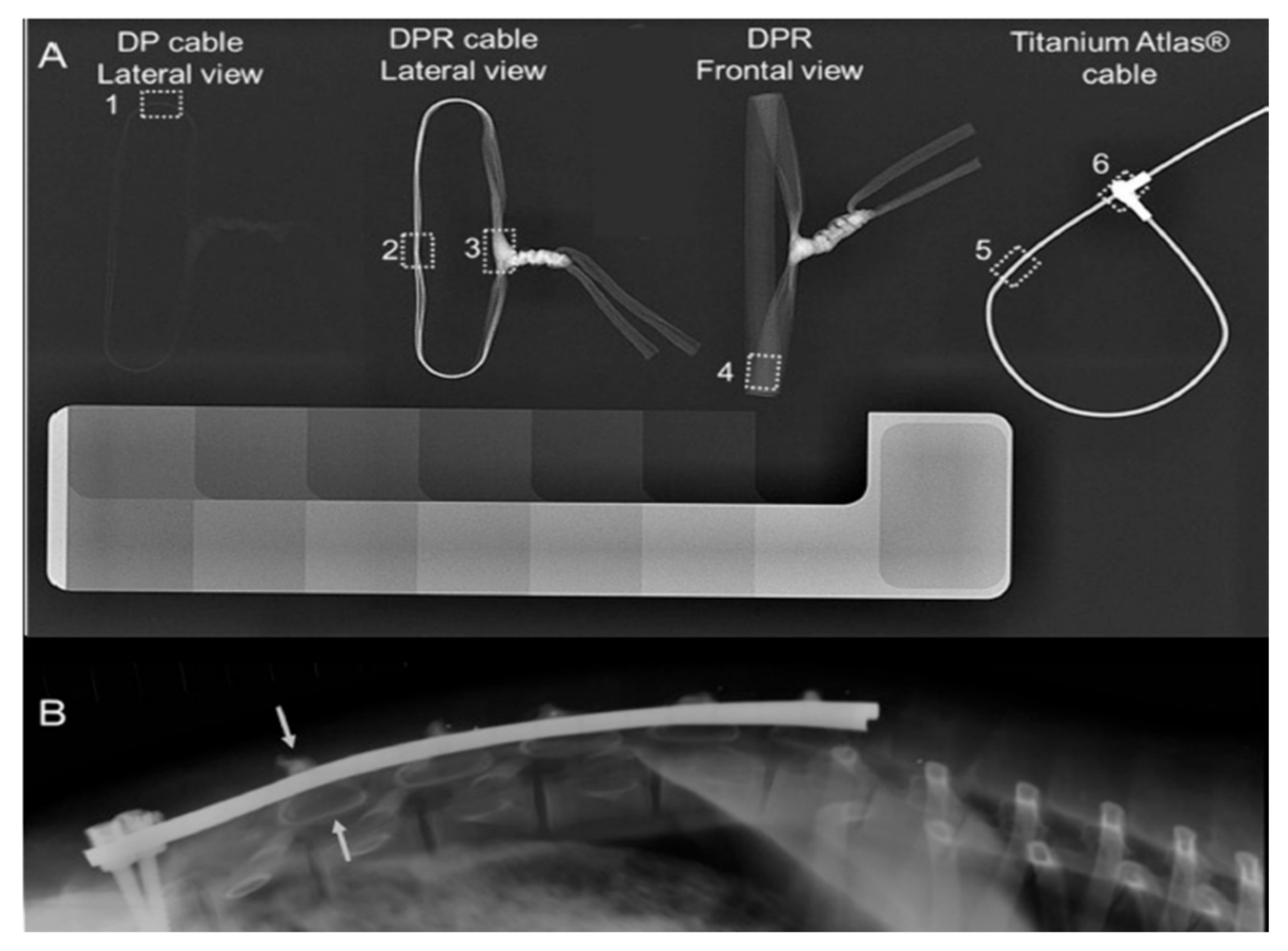

- Roth, A.K.; Karlien Boon-Ceelen; Smelt, H.; Bert van Rietbergen; Willems, P.; Rhijn, van; Arts, J.J. Radiopaque UHMWPE Sublaminar Cables for Spinal Deformity Correction: Preclinical Mechanical and Radiopacifier Leaching Assessment. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B 2017, 106 (2), 771–779. [CrossRef]

- Bogie, R.; Roth, A.K.; Faber, S.; Jong; T. Welting; Willems, P.; Arts, J.J.; L.W. van Rhijn. Novel Radiopaque Ultrahigh Molecular Weight Polyethylene Sublaminar Wires in a Growth-Guidance System for the Treatment of Early-Onset Scoliosis. Spine 2014, 39 (25), E1503–E1509. [CrossRef]

- Kozakiewicz, M.; Leszek Olbrzymek; Ludomir Stefanczyk; Marek Olszycki; Komorowski, P.; Walkowiak, B.; Konieczny, B.; Krasowski, M.; Jerzy Sokołowski. Radio-Opaque Polyethylene for Personalized Craniomaxillofacial Implants. Clinical oral investigations 2016, 21 (5), 1853–1859. [CrossRef]

- Wei Jen Chang; Yu Hwa Pan; Jy Jiunn Tzeng; Ting Lin Wu; Tsorng Harn Fong; Feng, S.-W.; Haw Ming Huang. Development and Testing of X-Ray Imaging-Enhanced Poly-L-Lactide Bone Screws. PloS one 2015, 10 (10), e0140354–e0140354. [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.B.; Guo, J.; Hu, J.; Shan, D.; Yang, J. Novel Applications of Urethane/Urea Chemistry in the Field of Biomaterials. Advances in Polyurethane Biomaterials 2016, 115–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawlee, S.; Jayabalan, M. Intrinsically Radiopaque Polyurethanes with Chain Extender 4,4′-Isopropylidenebis [2-(2,6-Diiodophenoxy)Ethanol] for Biomedical Applications. Journal of Biomaterials Applications 2014, 29(10), 1329–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JAMES, N.; PHILIP, J.; JAYAKRISHNAN, A. Polyurethanes with Radiopaque Properties. Biomaterials 2006, 27(2), 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawlee, S.; Jayabalan, M. Development of Segmented Polyurethane Elastomers with Low Iodine Content Exhibiting Radiopacity and Blood Compatibility. Biomedical Materials 2011, 6(5), 055002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiran, S.; James, N.R.; Joseph, R.; Jayakrishnan, A. Synthesis and Characterization of Iodinated Polyurethane with Inherent Radiopacity. Biomaterials 2009, 30(29), 5552–5559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, W.; Xia, W.; Feng, C.; Tuo, X.; Qiu, T. Synthesis and Characterization of Radiopaque Poly(Ether Urethane) with Iodine-Containing Diol as Chain Extender. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry 2011, 49 (10), 2191–2198. [CrossRef]

- Kiran, S.; James, N.R.; Jayakrishnan, A.; Joseph, R. Polyurethane Thermoplastic Elastomers with Inherent adiopacity for Biomedical Applications. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A 2012, 100A (12), 3472–3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, S.; Joseph, R. Synthesis and Characterization of a Noncytotoxic, X-Ray Opaque Polyurethane Containing Iodinated Hydroquinone Bis(2-Hydroxyethyl) Ether as Chain Extender for Biomedical Applications. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A 2013, 102(9), 3207–3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sang, L.; Wei, Z.; Liu, K.; Wang, X.; Song, K.; Wang, H.; Qi, M. Biodegradable Radiopaque Iodinated Poly(Ester Urethane)S Containing Poly(ε-Caprolactone) Blocks: Synthesis, Characterization, and Biocompatibility. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A 2013, 102(4), 1121–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, D.-J. The Relative Physical and Thermal Properties of Polyurethane Elastomers: Effect of Chain Extenders of Bisphenols, Diisocyanate, and Polyol Structures. Journal of applied polymer science 1997, 66(7), 1251–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, L.; Luo, D.; Wei, Z.; Qi, M. X-Ray Visible and Doxorubicin-Loaded Beads Based on Inherently Radiopaque Poly(Lactic Acid)-Polyurethane for Chemoembolization Therapy. Materials science & engineering. C, Biomimetic materials, sensors and systems 2017, 75, 1389–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Particle and Size | Test on microbial strains | Concentration | Mechanism of action | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silver nanoparticles (7 nm) |

E. coli (Gram-negative) S. aureus(Gram-positive) |

3.38 and 6.75 μg/mL | Damage DNA and disturb the synthesis of protein | [36] |

| Silver oxide nanoparticles (42.7 nm) |

Streptococcus mutans (Gram-positive) Lactobacillus acidophilus (Gram-positive) |

Streptococcus mutans: At conc 250 μg zone of inhibition (ZI) was 6 ± 0.8 mm, MBC was 22 ± 0.2% L. acidophilus: zone of inhibition 8 ± 0.4 mm, MBC 25 ± 0.5% |

Mechanism unclear | [37] |

| Fluorescent Ag nanoparticles (nAg-Fs), 1.5 nm |

Staphylococcus epidermidis NCIM2493, Bacillus megaterium (Gram-positive) Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC27853, Escherichia coli (Gram-negative) |

No cell growth was observed at conc. 2.0 μg/mL | Penetration of nAg-NPS into cell cytoplasm, leakage of cytoplasmic contents | [38] |

| SDS-stabilized silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), 25 nm |

Candida albicans (I, II) Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis |

0.052 mg/L (C. albicans I) 0.1 mg/L (C. albicans II) 0.42 mg/L (C. tropicalis) 0.84 mg/L (C. parapsilosis) |

The surfactant activity of NPs disrupts the cell wall of yeast. | [39] |

| Silver nanoparticles (30–50 nm) | HIV-1 isolates | 0.44 to 0/91 mg/mL | Prevention of CD-4 dependent virion binding, fusion, infectivity, inhibition of post-entry stages of HIV-1 lifecycle. | [40] |

| Silver/chitosan nanoparticles (3.5, 6.5, 12.9 nm) | H1N1 influenza A | 100 μg of Ag NPs was added to 1 mg of chitosan | Inhibiting viral penetration into the host cell | [41] |

| Silver nanoparticles of Lampranthus coccineus (10.12–27.89 nm), Malephora lutea (8.91–14.48 nm). | HAV-10, HSV-1, CoxB4 |

L. coccineus: HAV-10- no activity, HSV-1- 520.6μg/mL, COxB4- no activity (aqueous nano extract) 11.7μg/mL, 36.36μg/mL, 12.74μg/mL (hexane nano extract) M. lutea: no activity for aqueous nano extract, HAV-10- 31.38μg/mL, HSV-1-no activity, COxB4- 29.04μg/mL (hexane nano extract) |

Not determined | [42] |

| Copper nanoparticles (3–10 nm) |

Phoma destructiva (DBT 66) Curvularia lunata (MTCC, 2030) Alternaria alternate (MTCC 6572) Fusarium oxysporum (MTCC 1755) |

Zone of inhibition (ZI) value for Phoma destructive: 22 ± 1 mm Curvularia lunata: 21 ± 0.5 mm Alternaria alternate: 18 ± 1 mm Fusarium oxysporum: 24 ± 0.5 mm |

Not clearly mentioned | [43] |

| Cuprous oxide nanoparticles (45.4 ± 68 nm) | Hepatitis C virus (HCV) | 2 μg/mL | Attachment and entry Inhibition of HCV infection | [44] |

| Copper Iodide nanoparticles (160 nm) | Feline Calicivirus | 10 ng/mL to 10 μg/mL | ROS generation and subsequent capsid protein oxidation | [45] |

| Gold-chitosan hybrid nanoparticles (16.9 nm) |

S. aureus (Gram positive) P. aeruginosa (Gram-negative) |

0.25 mg/mL | Mechanism still unclear | [46] |

| Gold nanoparticles (25 nm) | Candida sp | 16–32 μg/mL | Inhibition of H + ATPase leads to intracellular acidification and cell death | [47] |

| Gold nanoparticles (17 nm) | HIV-1 | 0.05–0.12 mg/mL | The mechanism of gold nanoparticles against HIV-1 is not clear but it inhibits the HIV-1 fusion | [48] |

| Zinc oxide nanoparticles (30 nm) | Camphylobacter jejuni (Gram-negative) | 0.05–0.025 mg/mL | Disruption of the cell membrane and oxidative stress in C. jejuni. | [49] |

| Zinc oxide nanoparticles (70 nm) |

Botrytis cinerea Penicillium expansum |

3–12 mol/Ll−1 | Inhibition of growth by affecting cellular functions | [50] |

| Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs), 70 ± 15 nm |

Botrytis cinerea, Penicillium expansum |

3 mmol/L | Deformation in fungal hyphae by affecting cellular function | [50] |

| Zinc oxide nanoparticles (12–32 nm) |

Alternaria alternata (ITCC 6531), Aspergillus niger (ITCC 7122), Botrytis cinerea (ITCC 6192), Fusarium oxysporum (ITCC 55), Penicillium expansum (ITCC 6755) |

64 μg/mL (A. alternata) 16 μg/mL (A. niger) 128 μg/mL (B. cinerea) 64 μg/mL (F. oxysporum) 128 μg/mL (P. expansum) |

Disruption of membrane structure and change in permeability. | [51] |

| Zinc oxide nanoparticles (16–20 nm) | H1N1 Influenza | 75 and 200 μg/mL | Suppress the proliferation of influenza virus at an inhibition rate of 52.2% | [52] |

| Zero-valent Iron (Fe°) nanoparticles, spherical (31.1 nm) |

Staphylococcus aureus (Gram-positive) E. coli (Gram-negative) |

MIC for both strains at 30 μg/mL and complete growth inhibition at 60 μg/mL | Oxidative stress generation via ROS and visible damage to bacterial protein and DNA. | [53] |

| Magnetic Iron oxide nanoparticles (50–110 nm) | S. aureus (Gram-positive) | DMF solution with 40 and 60 mJ laser fluencies showed the highest antibacterial activity | This could be due to stress generated by ROS disrupting the bacterial cell membrane. | [54] |

| Iron oxide nanoparticles (10–30 nm) | Trichothecium roseum, Cladosporium herbarum, Penicillium chrysogenum, Alternaria alternate and Aspergillus niger. | Varies between 0.063-0.016 mg/mL | Formation of ROS, damage of protein, and DNA by oxidative stress. | [55] |

| Nickel ferrite (NiFe2O4) nanoparticles (NFOTP) | Staphylococcus aureus NCIM 5021, Streptococcus pyogenes NCIM 5280 (Gram-positive) Escherichia coli NCIM 2345, Salmonella typhimurium NCIM 2501 (Gram-negative) |

Zone of inhibition for E. coli was seen but no numeric value is mentioned. | Higher negatively charged surface of E. coli, thin surface and formation of reactive oxidative species (ROS) and oxidative stress lead to cell death. | [56] |

| Iron oxide nanoparticles (10–15 nm) | A/Puerto Pico/8/1934H1N1 influenza virus strain (PR8-H1N1) | 1.1 pg | Inactivation of cell protein through the interaction of nanoparticles and –SH group (Proposed, not investigated yet) | [56] |

| TiO2 nanoparticles (70–100 nm) | Candida albicans | 5.14 μg/mL | Inhibition of fungal biofilms | [57] |

| BaSO4 nanoparticles (73 nm) |

Staphylococcus aureus; P. aeruginosa (Schroeter) ;Migula |

Nano BaSO4, 40% | Hypothesized the difficulty of preliminary steps on bacterial adhesion due to the nano roughness of the material | [58] |

| Nanomaterial | Functionalization | Cell Lines | Ref |

| Graphene-based nanosheets | Surface functionalization by bio-compatible targeting ligands and coatings | MDA-MB-468 (MCF-7) | [75] |

| Molybdenum disulfide nanosheets | Chitosan; PLGA, PEG functionalization | Breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-468), HeLa uterine cancer cells, human lung cancer cells | [76] |

| Transition metal nanoparticles decorated with polymers | Polymer functionalization | Mice bearing 4T1 breast cancer cell xenografts | [77] |

| Lanthanide-activated nanoparticles | Doping with lanthanide | Cancer cells xenografted in mice | [78] |

| Group IV quantum dots | Surface functionalization | Various cancer cell types | [79] |

| Graphene oxide nanosheets | Surface functionalization | Tumor cells | [80] |

| Peptide-based nanoparticles | Chemical functionalization | Peptide-treated HeLa cells preloaded with Hg2+ | [81] |

| Silver nanoparticles | Aptamer conjugation | Leukemia cells, neural stem cells, kidney tissue, renal carcinoma cells | [82] |

| Gold nanoprisms | Conjugation with polyethylene glycol | Gastrointestinal carcinoma cells (HT 29) | [83] |

| Gold nanorods | Encasing by mesoporous silica | Carcinoma cells | [84] |

| Magnetofluroscentnanoprobe | Surface functionalization | Human Breast Cancer (MCF-7), HeLa cells | [85] |

| Dye-loaded nanoemulsions | Lipids conjugation with polyethylene glycol | Human colon cancer (HCT116), HeLa cells | [86] |

| Cadmium telluride quantum dots | Capping by shells | Human bronchial epithelial cells | [87] |

| Contrast agent | Blending method | Polymer | Application | Content | Reported effects | Polymer biodegradable | Biological response | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BaSO4 | Blended in the powder phase | PMMA | Bone cement | 9–15 wt % | Hard particles, third body wear, reduced tensile and flexural strength | NO | Osteoclast formation | [88] [89] [90] |

| Blended in the powder phase | PMMA | Vertebroplasty cement | 30 wt % | Hard particles, third body wear, lower viscosity | NO | Osteoclast formation | [91] [92] [93] |

|

| Twin-screw micro-compounding | PLLA | Bioresorbable stents | 5–20 wt % | Increased tensile modulus and strength, decreased elongation at break and ductility | YES | No adverse effects after 21 days | [94] [95] |

|

| Magnetic stirring in organic solvent | PLGA | Bioresorbable stent | 17.9 v/v % | Increased Young’s modulus, reduced elasticity, increased radial strength | YES | Na | [96] | |

| Solution mixing | PLGA | Bone fixation plate | 1:10 and 1:3 w/w PLGA:BaSO4 | Radiopaque up to 56 days, BaSO4 leaching < 0.5 mg/day; insufficient to induce cytotoxicity | YES | No adverse effects | [97] | |

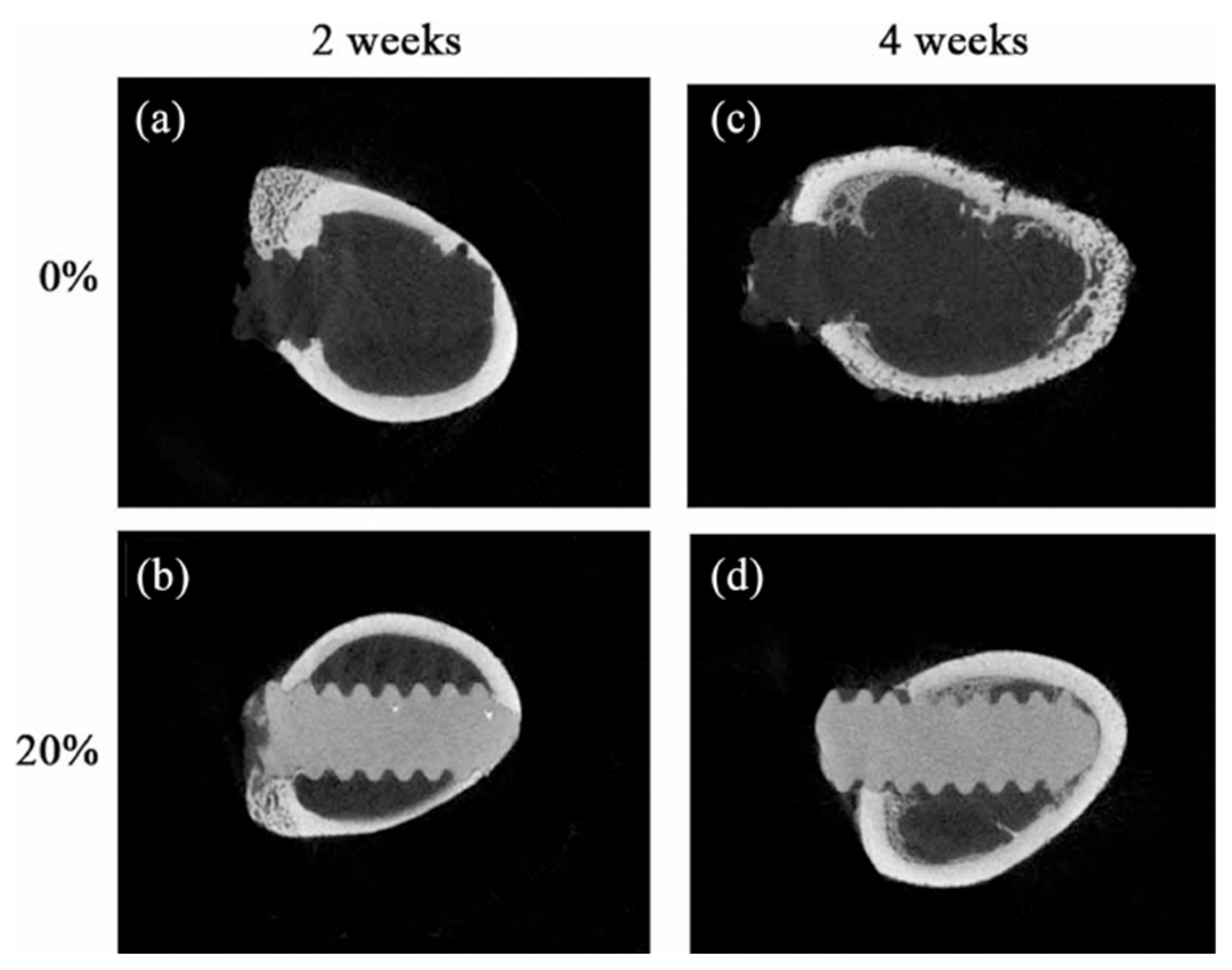

| Lipiodol ultra fluid | Immersion in oil at elevated temperature | UHMWPE | TKA insert | 25 mL | Physical alteration–swelling, 54% reduction in surface radiopacity after 4 weeks | NO | Na | [98] |

| Iohexol(IHX) | Stirring | PLA | Bioresorbable implants | 40 wt % | Reduced tensile strength, elongation at break and increased tensile modulus, enhanced crystallinity, slower polymer degradation | YES | Thin fiber capsule | [99] |

| Blended in the powder phase | PMMA | Bone cement | 10 wt % | Better biocompatibility compared to conventional contrast agents | NO | Osteoclast formation | [90] | |

| Iodixanol(IDX) | Blended in the powder phase | PMMA | Bone cement | 10 wt % | Higher osteoclast formation than IHX | NO | Osteoclast formation | [90] |

| Iobitridol | Dissolved in liquid phase | CPC | Bone cement | 56 mg Ml^–1 | Rapid release of contrast, no significant change in mechanical properties, no effect on injectability, cohesion, or setting time | YES | No adverse effects | [100] |

| Iodinated diphenol | Polymerization reaction | PLA diol | Coronary stent | <1% of 1 mL of iodine contrast | Increased ultimate tensile strength and elongation at break, long-term radiopacity | YES | No adverse effects | [101] |

| Bismuth salicylate(BS) | Dissolved in liquid phase | PMMA | Vertebroplasty cement | 10 w/w | Reduced compressive and tensile strength, reduced strain, lower setting temperature, increased radiopacity, longer injection time, Better compatibility than BaSO4 | NO | Na | [102] [103] |

| Triphenyl bismuth(TPB) | Dissolved in liquid phase | PMMA | Bone cement | 10 wt % | Increased ultimate tensile strength, Young’s modulus and strain to failure, lower setting temperature, better homogeneity | NO | Na | [104] |

| Bismuth oxide Bi2O3 | Blended into fiber | UHMWPE | Sublaminar cables | 20 wt % | Decreased tensile strength, limited leaching below toxic levels | NO | No adverse effects | [105] [106] |

| Titanium dioxide TiO2 | Blending | PE | Orbital implant | 6% | Slight decrease in tensile strength and modulus, significant decrease in compressive strength and modulus, reduced hardness | NO | No adverse effects | [107] |

| Iron oxide Fe3O4 | Twin-screw extrusion | PLLA | Bone screws | 20 wt % | Reduced flexural strength, increased crystallinity, increased thermal stability | YES | Osteogenic effect, no adverse effects | [108] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).