1. Indolizidines: Structure, Sources, and Bioactivities

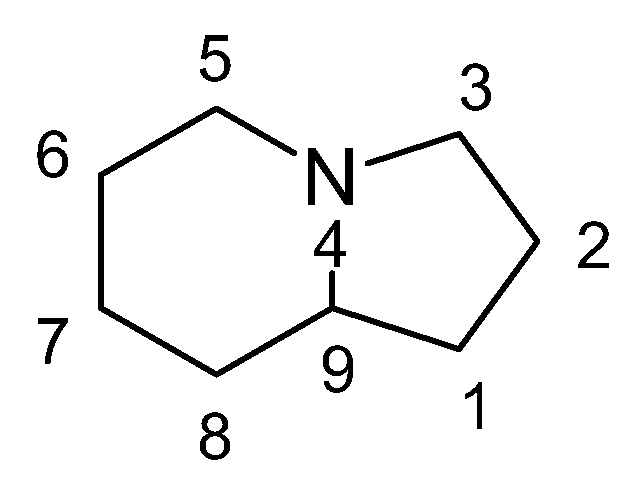

Indolizidines represent a class of structurally related alkaloids. Their core structure consists of a bicyclic framework comprising one cyclohexane and one cyclopentane, linked together through C9 and N4 (

Figure 1). Indolizidine derivatives can be extracted from various plant species, including legumes and orchids, as well as from certain animal species, such as ants, contributing to their diverse natural occurrence [

1].

Indolizidines display a wide range of activities, including antimycotic [

2], antimalarial [

3], and anti-inflammatory [

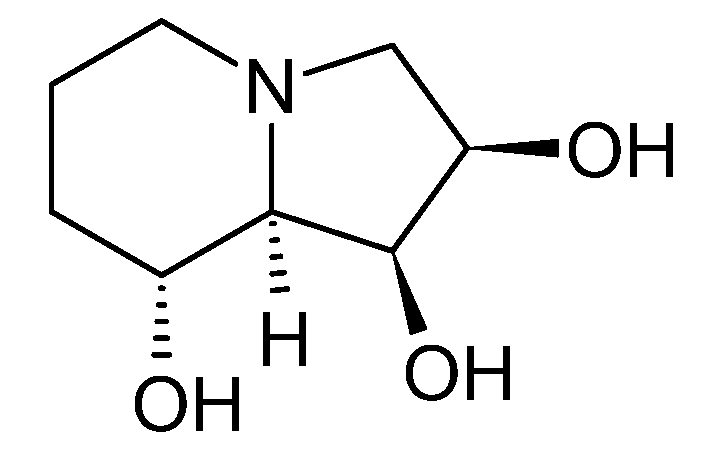

4] properties, highlighting their diverse pharmacological potential. Swainsonine, for example, is a well-known indolizidine notorious for its toxicity to livestock (

Figure 2) [

5], also demonstrates anticarcinogenic activity. Studies have shown its ability to inhibit various glioma cancer cells [

6,

7], human gastritic carcinoma cells [

8], as well as to reduce the tolerance of colorectal cancer cells to 5-fluorouracil [

9]. Only recently new indolizidines with an unusual, fused pyrrolidine moiety have been isolated from

Anisodus tanguticus, a plant native in China. Some of the compounds displayed cytotoxic potential against the cancer cells lines A2780, A549 and HGC-27 [

10].

2. Bioactive Metabolites from Microorganisms

Plants currently serve as the primary source of indolizidines [

1]. However, biotechnological production by microorganisms offers several advantages over plant-based production. A broad panel of instruments exist to easily manipulate microorganisms genetically for optimized production, and their growth and production rates can be much faster compared to plants. Furthermore, the scalability of production is typically easier with microorganisms. For instance, Pyne et al. developed a yeast platform for the improved synthesis of the tetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloid (S)-Noroclaurine. This led to manifold increases in yields and enabled the de novo synthesis of novel tetrahydroisoquinoline derivatives through genetic engineering [

11]. Likewise, cultivating bacterial or fungal species capable of producing bioactive indolizidines holds great promise for unlocking prolific sources of indolizidines.

As of today, four microbial species capable of producing indolizidines have been identified [

12,

13,

14,

15]. all four known bacterial producers of indolizidines belong to the family of actinomycetes, a diverse group of bacteria renowned for their ability to produce medically relevant natural products [

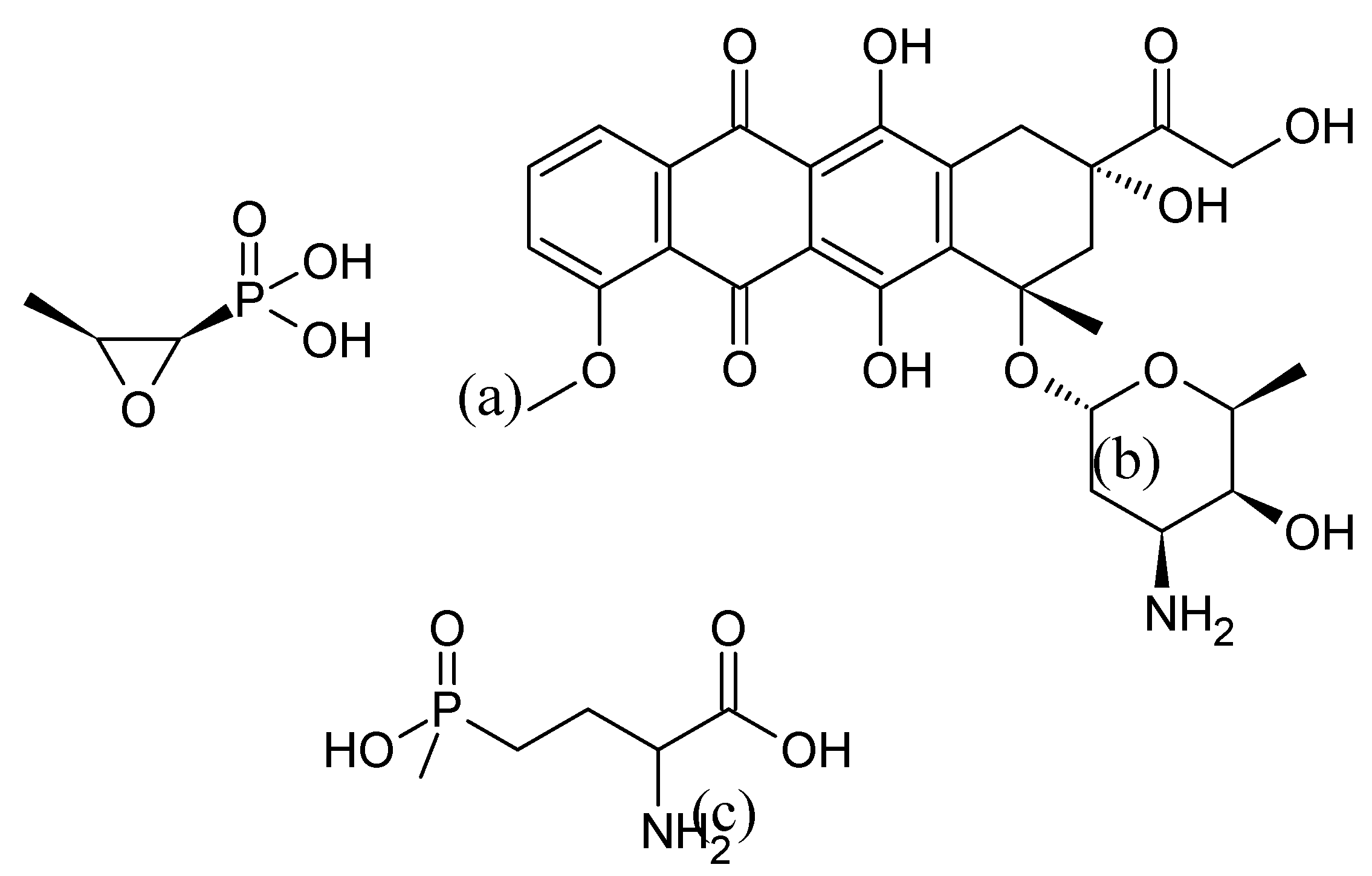

16]. Examples include fosfomycin from Streptomyces fradiae, (

Figure 3 (a)) [

17], considered an antibiotic of last resort by the World Health Organization [

18], doxorubicin from Streptomyces peuceticus (

Figure 3 (b)), used in chemotherapy [

19] and phosphinothricin from several

Streptomyces species (

Figure 3 (c)), exhibiting herbicidal activity akin to glyphosate [

20]. The immense potential of actinomycetes in the production of bioactive compounds with various applications has been extensively reviewed as for as example in [

21,

22,

23,

24].

3. Known Actinomycetical Indolizidine-Producers

The strains

Streptomyces sp. HNA39 [

12],

Saccharopolyspora sp. RL78 [

14] and

Streptomyces sp. NCIB 11649 [

13] belong to the four known bacterial producers of indolizidines. These strains produce a group of indolizidine-derivatives, which are collectively known as cyclizidines, due to a cyclopropane moiety in their structure. Various cyclizidines exhibit low to moderate cytotoxicity [

12,

14]. Sreptomyces griseus OS-3601 produces iminimycins, another type of indolizidine derivatives (Figure 9), which carry a rare imine-cation [

15]. Additionally, one indolizidine compound was created via protoplast fusion of one

S. griseus with

Streptomyces tenjimariensis resulting in a new structure named indolizomycin [

25]. In the following all found indolizidines and their producers will be presented.

3.1. Cyclizidine M146791 from Streptomyces sp. NCIB 11649

3.1.1. Structure and Isolation

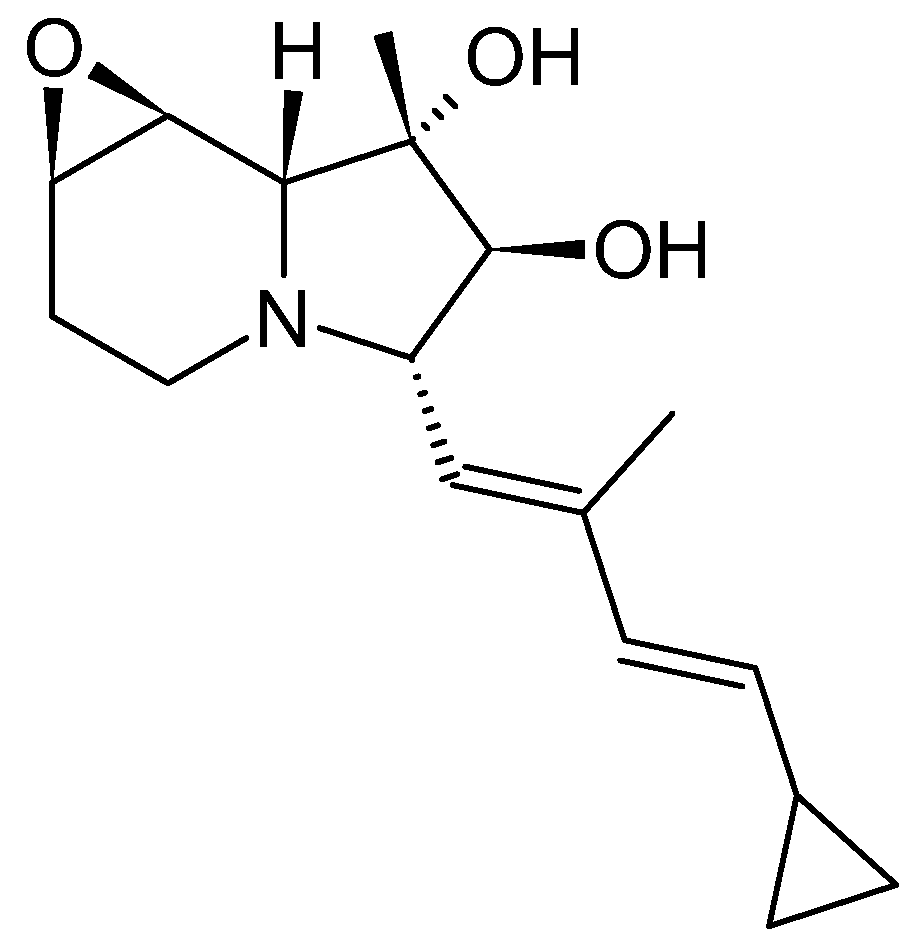

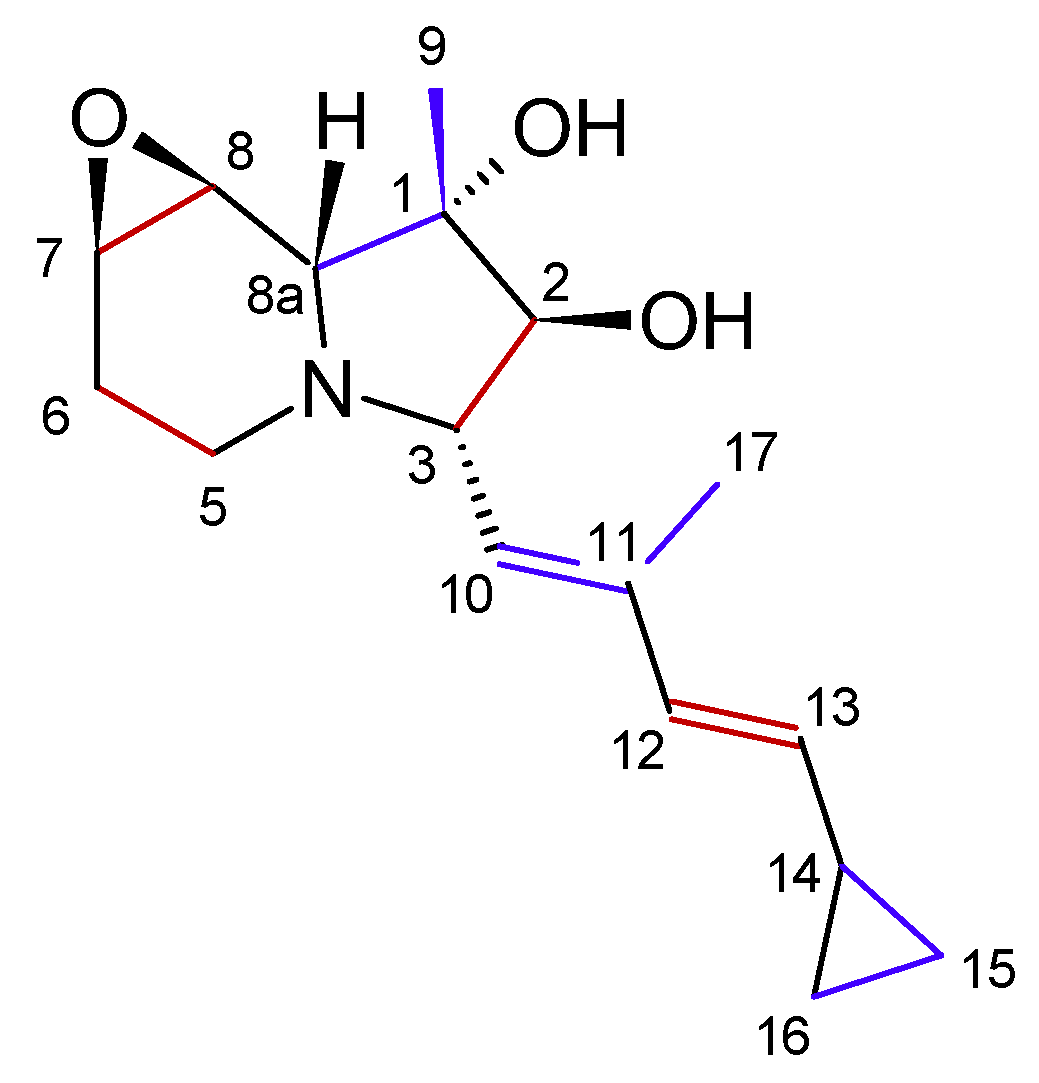

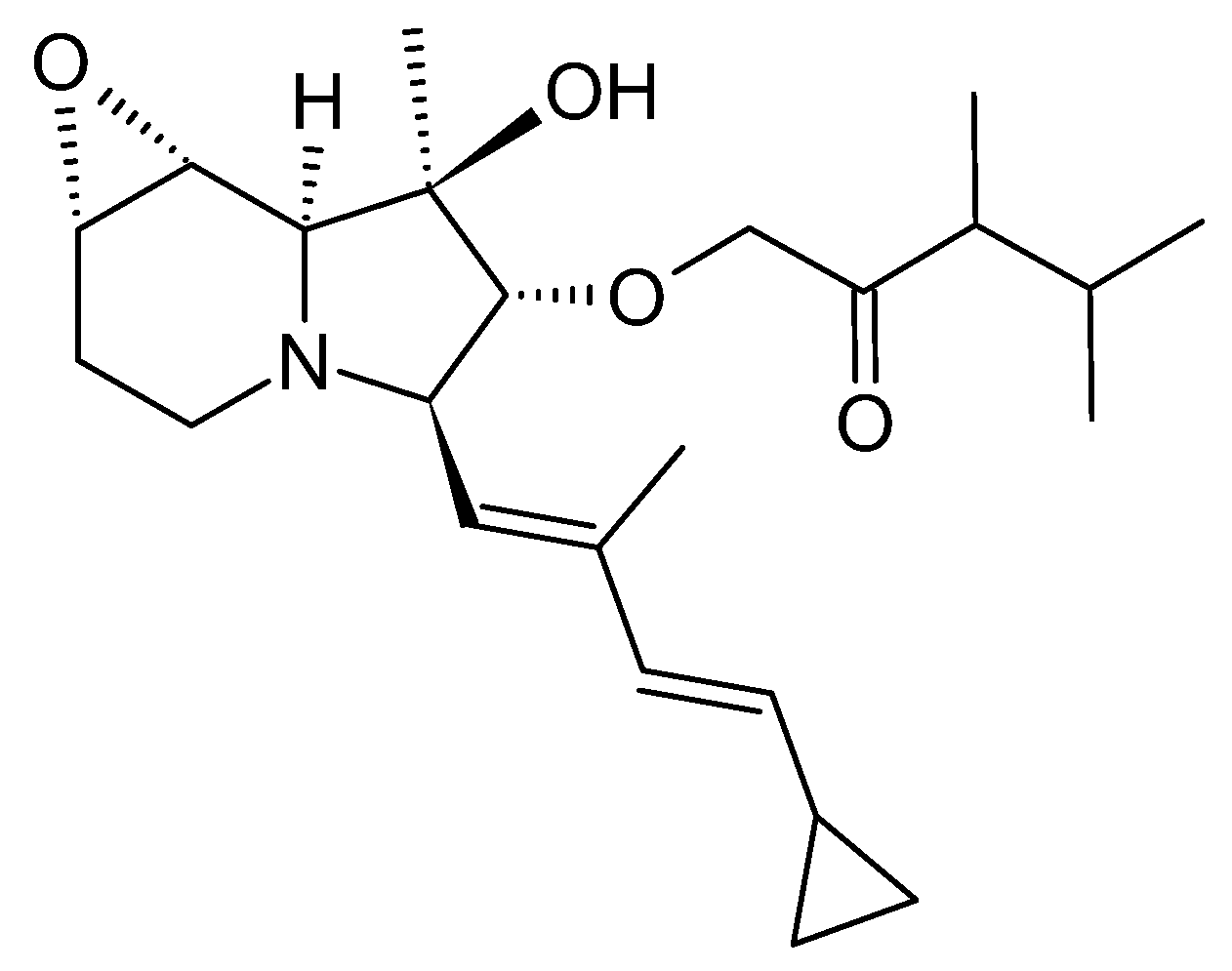

The first cyclizidine, named M146791 (

Figure 4), was discovered and structurally characterized using X-Ray crystallography in 1982. Its distinctive side group, featuring a cyclopropane terminus, had been unprecedented thus far. Cyclizidine was extracted from

Streptomyces sp. NCIB 11649, a bacterium that caught attention for its antifungal properties. strain NCIB 11649 was originally isolated from soil sourced in Stretford, Greater Manchester, UK [

13].

Cyclizidine was isolated through ethyl acetate extraction at pH 7, followed by treatment with animal charcoal and recrystallization from ethyl acetate [

26]. The cyclizidine biosynthetic machinery was elucidated on the basis of this strain in 2015 [

13].

3.1.2. Biosynthesis

First successful attempts at elucidating cyclizidine biosynthesis were performed by Leeper et al. in 1990. Strain NCIB 11649 was fed with the labelled cyclizidine precursor molecules CH

313C

18O

2Na and CD

3CH

213CO

2Na. The experiments confirmed that, as per usual for polyketides, the molecule is built from acetate and propionyl units (

Figure 5). The hydroxyl group at C2 is thereby derived from an acetyl moiety, while the typical cyclopropyl ring originates from a single proprionate unit [

27].

Indolizidines are synthesized by large modular enzyme complexes known as polyketide-synthases (PKSs) [

13]. PKSs serve as assembly lines for numerous bioactive compounds, such as the antibiotic erythromycin [

28] and the chemotherapeutic agent epothilone [

29]. Three types of PKSs have been identified thus far [

30]. The cyclizidine-PKS belongs to type II [

13], which is characteristic for bacteria and consists of several modules, which are further subdivided into domains with specific functions. The polyketide is passed from module to module for processing. In each module, the polyketide is elongated and modified depending on the domains present. Typically, one module contains the obligatory ketosynthase- (KS), Acyltransferase- (AT) and an acyl carrier protein (ACP) domain. The ACP transfers the growing polyketide chain to the KS of the following module. The AT elongates the chain by one carboxyacyl extender unit via esterification. Each module can include optional domains, which consecutively reduce the added extender unit: the ketoreductase reduces the added keto-group into a hydroxy-group, the dehydaratase-domain eliminates the hydroxy-group to establish a double bond, and the double bond can be converted into a fully reduced single bond by the enoyl-reductase domain. Additionally, a methyl-group can be added via the methyltransferase domain. A terminal reductase domain (TR) releases the polyketide chain from the PKS [

30].

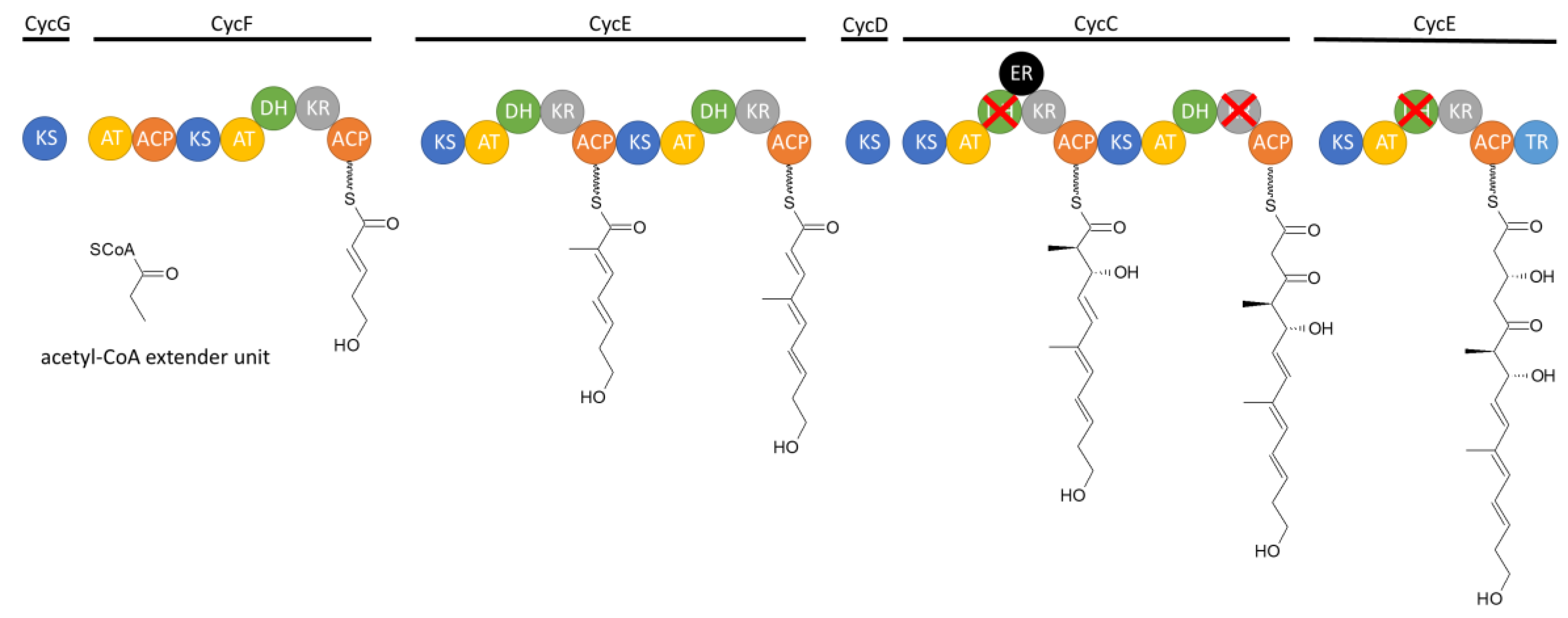

The cyclizidine PKS in strain NCIB 11649 has been elucidated by in vitro biochemical analysis as well as in vivo mutagenesis studies. The cluster is made up of seven modules, which are encoded in six genes, named cycB to cycG (

Figure 6). Module 1 recruits the first acetyl-CoA starter unit without further reduction of the unit. Module 2 includes a KR and DH domain, which results in the formation of a double bond in the second extender unit. This is also true for module 3 and 4. Module 3 uses methylmalonyl-CoA as the elongation unit, which introduces an additional methyl-group. Module 5 contains not only a KR and DH domain but also an ER domain. However, since the DH domain is not functional the modification of the extended unit of the polyketide stops at the hydroxy group. The KR domain in module 6 is also not functional, which results in a keto group there. Finally, in module 7, one last hydroxy group is added before the chain is released via the TR domain. The resulting chain is then modified further outside of the PKS. Additional open reading frames code for an aminotransferase, multiple oxidoreductases, a flavin reductase, and a ribonucleotide reductase, which collectively catalyze the cyclization reactions. This leads to the formation of the indolizidine core structure and the name-giving cyclopropane ring. The further biosynthetic pathway after the formation of the polyketide chain has yet to be experimentally verified [

13].

In addition to elucidating the biosynthesis of this natural product, cyclizidine has already been produced in a 26-step total synthesis starting from D-serine with identical conformation to the bioproduct. The overall yield amounted to 2.7% [

31].

3.1.3. Bioactivity

After isolating the pure compound, it was confirmed that cyclizidine was not responsible for the antifungal activity of strain NCIB 11649 after all. However, cyclizidine did show non-selective immunostimulatory properties. Furthermore, the acetylated compound elicited a decrease in the beating frequency of cultured heart cells, a response reminiscent of certain P-blocking medications [

26].

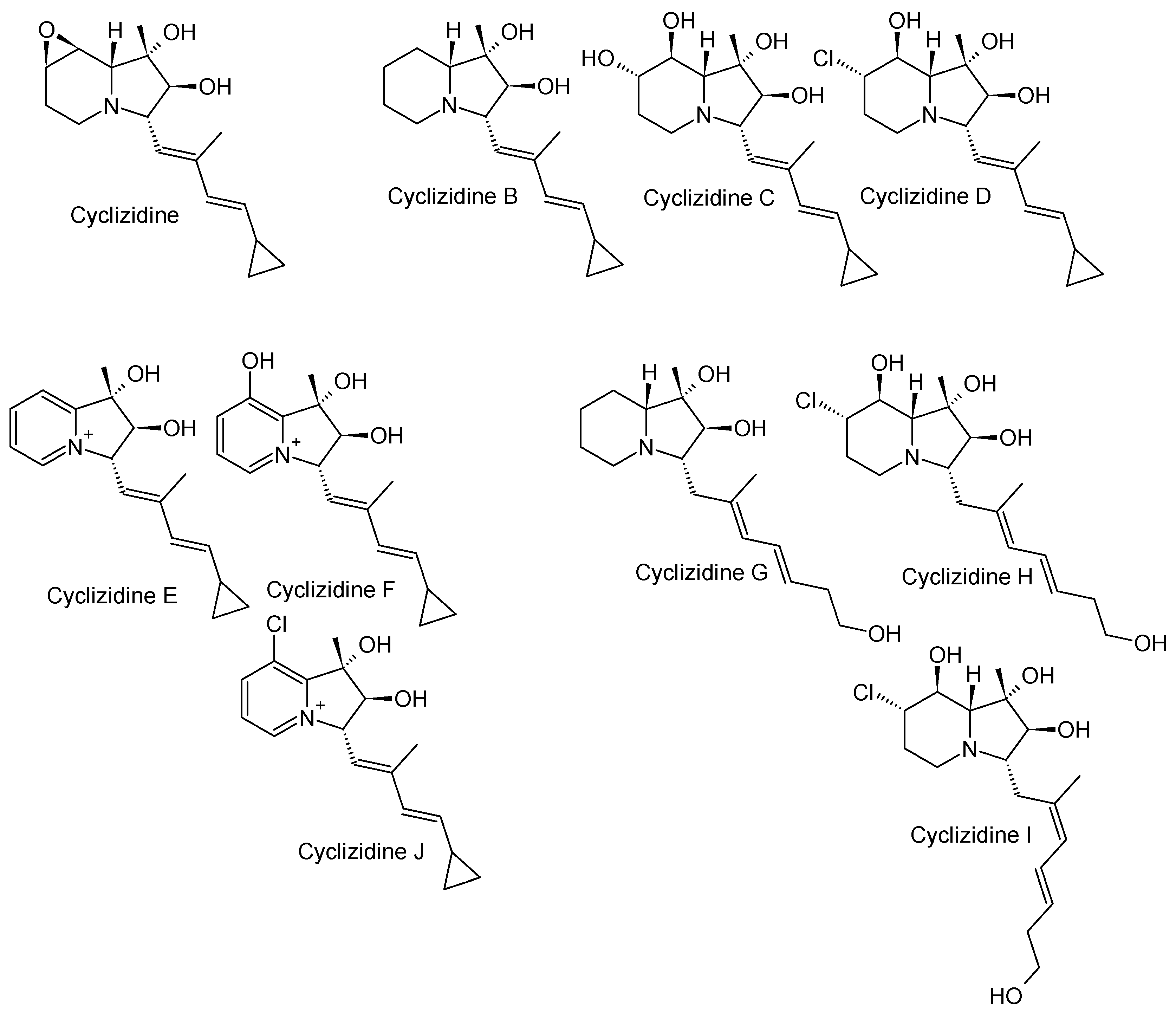

3.2. Cyclizidines from Streptomyces sp. HNA39

3.2.1. Structure and Isolation

The marine

Streptomyces sp. HNA39 originates from marine sediments of Hainan Island, China. The whole genome of the marine organism was recently sequenced. The genome revealed 29 putative biosynthetic gene clusters encoding secondary metabolites. One of these clusters is similar to the cyclizidine gene cluster of

Streptomyces sp. NCIB11649 [

32]. A total of ten compounds, nine of which were previously unknown, named cyclizidine B to J (

Figure 7), as well as the cyclizidine first isolated from strain NCIB 11649, were isolated from strain HNA39 [

12,

33].

To isolate the compounds, strain HNA39 was fermented in liquid medium and the culture broth was extracted with ethyl acetate. The extract was purified by silica-gel column chromatography and the compounds were separated by HPLC. Their common structural feature, besides the indolizidine core structure, is the cyclopropane ring after which all compounds are named. Although cyclizidines G, H and I do not show this feature, one can imagine that these two are precursors of the others, whereas G, H, and I would undergo a ring closure between C14 and C16. Cyclizidine I is the Z-isomer of cyclizidine H. While cyclizidine B appears relatively bare, cyclizidines C and D are decorated with hydroxy groups and a chlorine atom at C7 and 8, respectively. In the original cyclizidine, the two adjacent groups are combined in an epoxide ring [

26]. Cyclizidines E, F and J have an indolizinium system not previously found in cyclizidines. The nitrogen atom at the ring bridge transforms into a positively charged iminium cation under physiological conditions [

12,

33].

3.2.2. Bioactivity

Cyclizidines B to I were tested for their bioactivity against the cancer cell lines HCT-116 (colon cancer) and PC-3 (prostate cancer) in a colorimetric cytotoxicity assay with sul-forhodamine B (SRB) [

12,

34]. Cyclizidine J was tested only against PC-3 [

33]. The compounds showed low to moderate activities, with only cyclizidine C showing high cytotoxicity with IC

50 values of 0.52 ± 0.003 µM against PC-3 and 8.3 ± 0.1 µM against HCT116, while the positive control staurosporine reached values of 0.017 ± 0.004 and 0.055 ± 0.001, respectively. In addition, in a ROCK2 protein kinase inhibitory assay not only cyclizidine C but also F, H and I achieved moderate IC

50 values [

12,

33].

3.3. Cyclizidines from Saccharopolyspora sp. RL78

3.3.1. Structure and Isolation

Izumikawa et al. searched for new therapeutics against malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM). To this end, they screened the butanol culture extracts of 347 newly isolated from terrestrial and marine habitats by UHPL-MS for peeks not accounted for in the house intern database. The unknown compounds were isolated and their structures elucidated [

35]. Among the newly identified compounds was a new cyclizidine, named JBIR-102 (

Figure 8), produced by

Saccharopolyspora sp. RL78. This species was isolated from a mangrove soil sample from Ishigaki Island, Japan. After extraction of the cell pellet with acetone and ethyl acetate and separation by HPLC, an isobutyl ester derivative of cyclizidine was isolated [

14].

3.3.2. Bioactivity

The activity of JBIR-102 against malignant pleural mesothelioma and cervical cancer cells was tested in a colorimetric assay. JBIR-102 showed an IC

50 value of 39 µM against MPM ACC-MESO-1 cells and of 29 µM against HeLa cells. In comparison, cyclizidine shows slightly better activity with IC

50 values of 32 µM and 16 µM, respectively [

14].

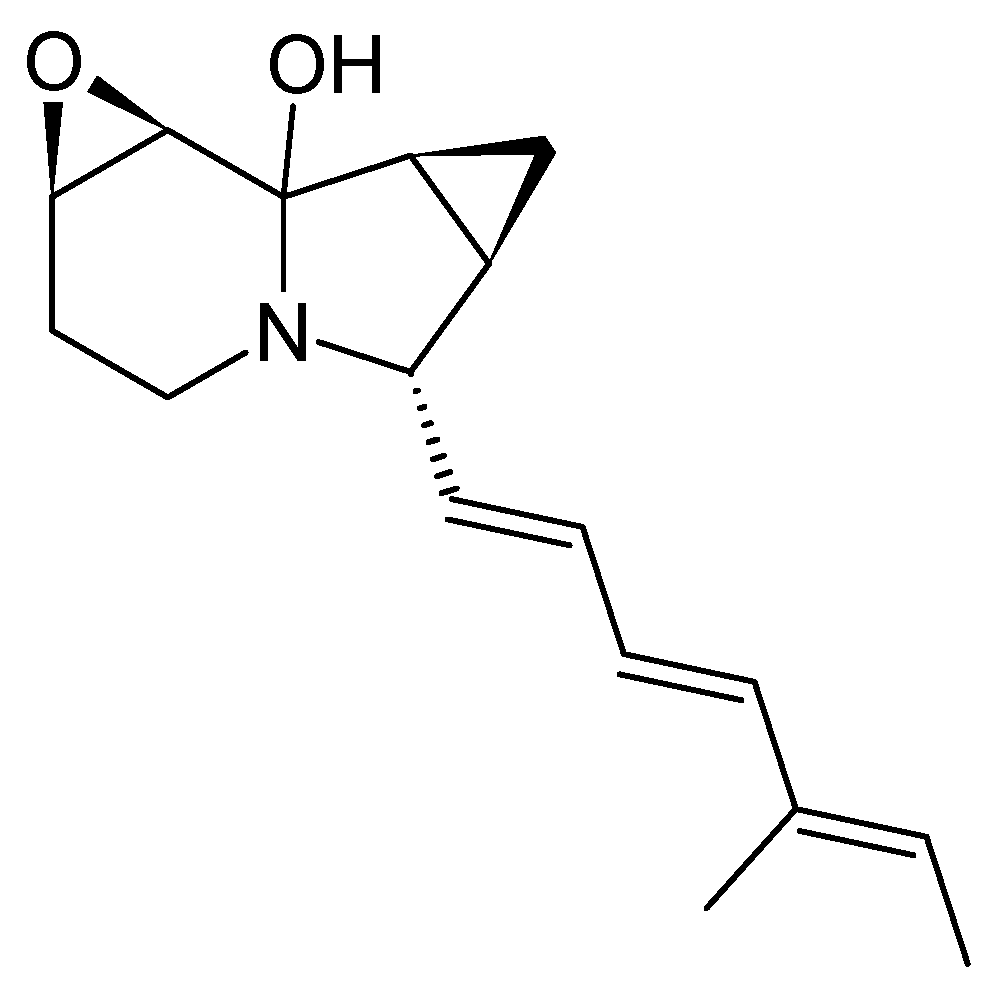

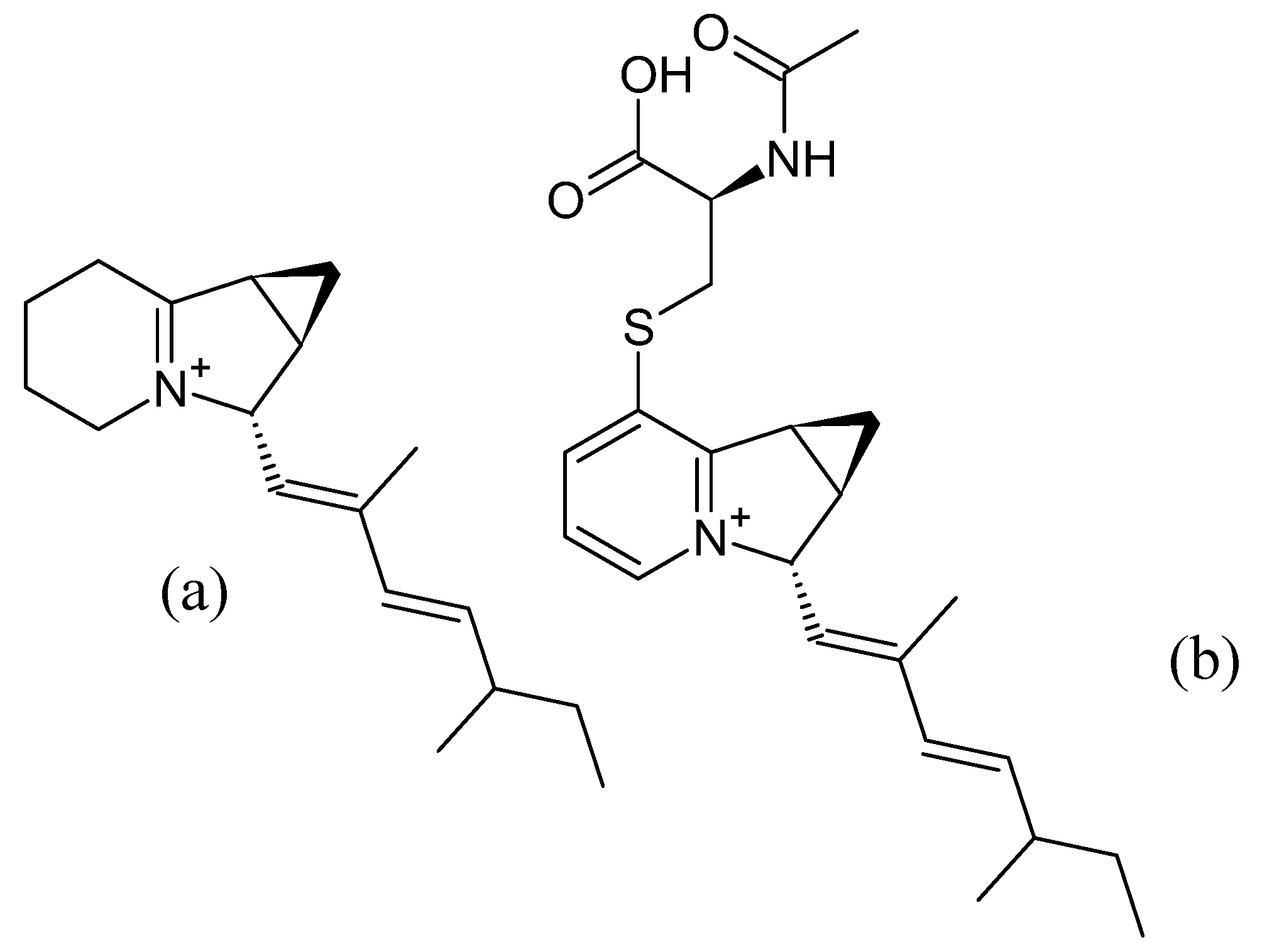

3.4. Iminimycins from Streptomyces griseus

3.4.1. Structure and Isolation

S. griseus has long been known as a producer of streptomycin [

36]. In addition, in 2016, two novel indolizidines were isolated from

S. griseus OS-3601, the cores of which consist of a 6-5-3 tricyclic system. Both molecules, named iminimycin A and B, carry a rare iminium cation and a cyclopropyl moiety fused to the indolizidine structure (

Figure 9) [

37,

38]. The iminium cation can also be found in cyclizidines E, F [

12], and J [

33] (

Figure 7). Unlike many cyclizidines, iminimycins A and B do not carry a cyclopropyl moiety at the olephinic tail, nor are the molecules hydroxylated or chlorated. The cyclohexane ring in iminimycin B is aromatized and an N-acetyl-cysteine moiety is attached to the aromatized indolizidine ring [

37,

38].

Isolation from culture broth was performed by silica gel column chromatography followed by HPLC. The iminimycins were eluted with methanol in water [

37,

38].

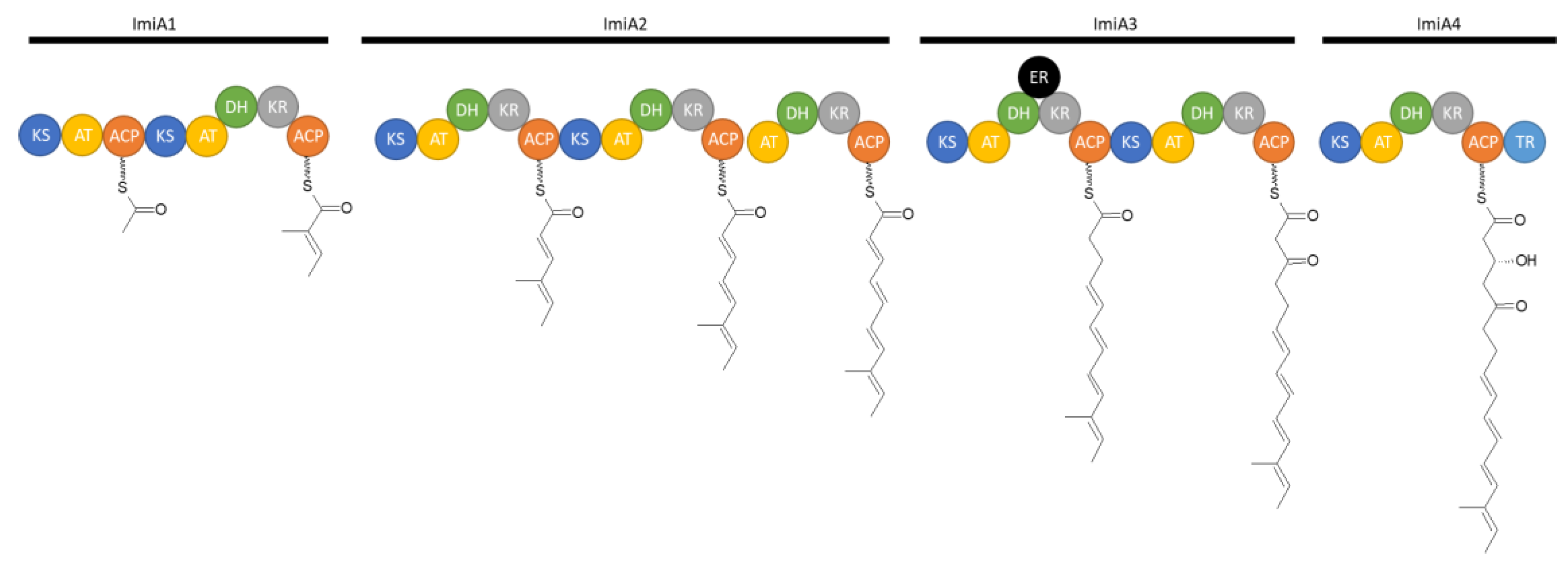

3.4.2. Biosynthesis

In additon to the isolation of these two compounds, the biosynthetic pathway of iminimycins was elucidated by bioinformatic analysis and subsequent inactivation of several genes within the biosynthetic gene cluster. Bioinformatic analysis revealed 22 genes, named imiA to imiT. Four genes, ImiA1 to 4, encode a type I PKS that synthesizes the polyketide chain on which the iminimycin structure is based. Eight modules forge the iminimycin chain. The acyltransferase domain of the first module was predicted to select (2S) methylmalonyl-CoA as the starter unit [

39].

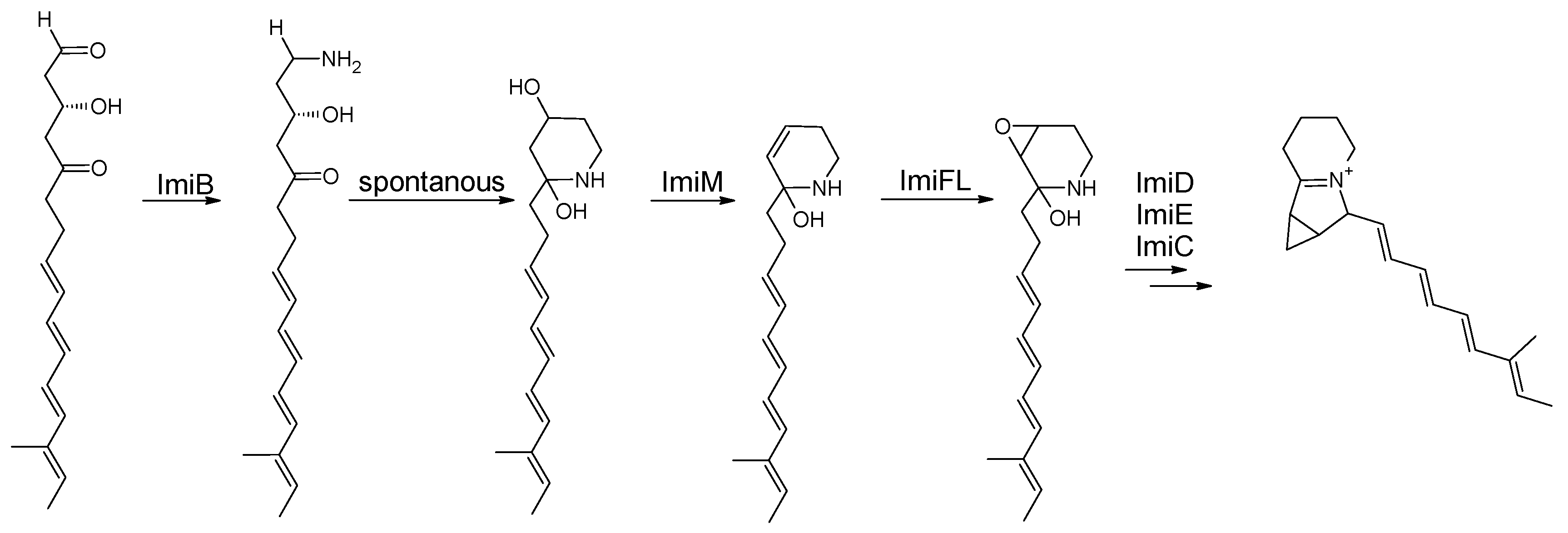

Eight modules in the gene cluster from a 16-membered polyketide chain: a tetraene is followed by modules with a fully oxidized keto moiety and a hydroxy group. After release, the group terminates in an aldehyde moiety. This aldehyde moiety is aminated by ImiB. The aminated polyketide chain undergoes a spontaneous cyclization reaction forming the six-membered ring of the indolizidine structure. Elimination of the hydroxy group at C4 results in a C4C5 double bond, which is oxidized to form the epoxide ring. The subsequent reactions are expected to be catalyzed by ImiM and ImiFL, respectively. The subsequent ring formation reaction, which completes the indolizidine core structure and results in imimycin A, is catalyzed by ImiD, C and E [

39].

Figure 10.

Schematic of the suggested iminimycin PKS assembly line from

S. griseus OS-3601 ([

39], modified by the author). KS=ketosynthase, AT=acyltranferase, ACP=acyl-carrier-protein, DH=dehydratase, KR=ketoreductase, ER=enoylreductase.

Figure 10.

Schematic of the suggested iminimycin PKS assembly line from

S. griseus OS-3601 ([

39], modified by the author). KS=ketosynthase, AT=acyltranferase, ACP=acyl-carrier-protein, DH=dehydratase, KR=ketoreductase, ER=enoylreductase.

Figure 11.

Post-PKS modifications of iminimycins in

S. griseus OS-3601 [

39].

Figure 11.

Post-PKS modifications of iminimycins in

S. griseus OS-3601 [

39].

3.4.3. Bioactivity

Iminimycin A showed little antibiotic activity against the bacteria

Bacillus subtilis,

Kocuria rhizophila and

Xanthomonas campestris pv. oryzae. Cytotoxicity against HeLa S3 and Jurkat cells was also determined, with IC

50 values of 43 µM and 36 µM, respectively [

37].

3.5. Indolizomycin from Streptomyces sp. SK2-52

3.5.1. Structure and Isolation

Shortly after the discovery of the first indolizidine, cyclizidine, from an actinomycete species, a second indolizidine, named indolizomycin, was discovered in 1984. Like cyclizidine, indolizomycin contains a cyclopropyl ring, but not at the end of the olephinic tail, but as a third ring added to the cyclopentane ring of the core indolizidine-structure, similar to the iminimycins (

Figure 12). This metabolite was not produced by a wild-type strain, but by a strain produced by interspecies fusion treatment: protoplasts of a

S. griseus strain, which was unable to produce any antibiotics, were fused with

S. tenjimariensis. As a result, the transformed strain

S. griseus SK2-52 produced indolizomycin. The indolizomycin was extracted from the culture broth using an Amberlite raisin column and eluted with 30% aqueous acetone. Subsequent treatment of the crude lyophilizate with methanol and preparative TLC purification followed by ethyl acetate extraction yielded a pure compound [

25].

3.5.2. Bioactivity

Indolizomycin exhibits weak antibiotic activity against several bacterial and fungal strains, such as Staphylococci, Bacilli,

E. coli and

Candida albicans. In addition, the LC

50 values against mice were determined to be 12.5 to 25 mg/kg. Cytotoxicity has not been tested [

25].

4. Conclusion and Future Prospects

While only a limited number of bacterial indolizidine producers have been identified thus far, it is evident that additional ones exist, harboring the potential to produce novel and bioactive compounds. Bioinformatic tools provide the means to screen huge amounts of genomic data. To give an example: In

Streptomyces sp. NCIB 11649 the gene cluster encoding the corresponding cyclizidine was elucidated (

Figure 6). This biosynthetic gene cluster can be used to identify other potential cyclizidine producers. The cluster has already been identified with almost 100% identity in

Actinosynnema mirum DSM 43827. The PKS of this cluster lacks the ER domain in domain 5 as well as the KR and DH domains in module 6. Furthermore, two additional putative KS domains appear to be fused to the N-terminus of what corresponds to CycF and CycC in strain NCIB 11649. However, the cyclizidine cluster in

A. mirum is not expressed under laboratory conditions. Thus, what kind of cyclizidine this altered cluster encodes and what bioactivities it might have remain to be explored [

13].

Collectively, the presented findings demonstrate that indolizidine derivatives have the potential to become anticancer drug candidates. However, there is currently a significant gap in our knowledge of these structures, particularly with regard to their pathway after release from polyketide synthases, the formation of the cyclopropane moiety in cyclizidines and, most importantly, their mode of action.

Furthermore, it is plausible that additional producers of these compounds, akin to A. mirum, exist. Activation of silent gene clusters could reveal new indolizidine derivatives with novel bioacitivities. The exploration of novel derivatives is warranted, as bacteria have been demonstrated to generate a diverse array of bioactive and potentially beneficial molecules. While the search for a bacterial indolizidine, with potential applications as an anticancer agent, holds promise, the outcome remains uncertain, and success may ultimately hinge on chance as it always does with natural products from microorganisms.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- J. Zhang et al., “Biologically active indolizidine alkaloids,” Med Res Rev, vol. 41, no. 2. [CrossRef]

- M. Dhiman, R. R. Parab, S. L. Manju, D. C. Desai, and G. B. Mahajan, “Antifungal Activity of Hydrochloride Salts of Tylophorinidine and Tylophorinine,” Nat Prod Commun, vol. 7, no. 9, pp. 1171–1172, Sep. 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. Kubo et al., “Antimalarial phenanthroindolizine alkaloids from Ficus septica,” Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo), vol. 64, no. 7, pp. 957–960, Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. W. Yang, W. L. Chen, P. L. Wu, H. Y. Tseng, and S. J. Lee, “Anti-inflammatory mechanisms of phenanthroindolizidine alkaloids,” Mol Pharmacol, vol. 69, no. 3, pp. 749–758, Mar. 2006. [CrossRef]

- S. Min, Y. Li, C. Nzabanita, H. Liu, M. Ting-Yan, and Y.-Z. Li, “Locoweed endophytes: A review,” 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Y. Sun et al., “Suppressive effects of swainsonine on C6 glioma cell in vitro and in vivo,” Phytomedicine, vol. 16, no. 11, pp. 1070–1074, Nov. 2009. [CrossRef]

- L. Sun, X. Jin, L. Xie, G. Xu, Y. Cui, and Z. Chen, “Swainsonine represses glioma cell proliferation, migration and invasion by reduction of miR-92a expression,” BMC Cancer, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 1–10, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Y. Sun, M. Z. Zhu, S. W. Wang, S. Miao, Y. H. Xie, and J. B. Wang, “Inhibition of the growth of human gastric carcinoma in vivo and in vitro by swainsonine,” Phytomedicine, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 353–359, May 2007. [CrossRef]

- J. Hamaguchi et al., “Swainsonine reduces 5-fluorouracil tolerance in the multistage resistance of colorectal cancer cell lines,” Mol Cancer, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 1–9, Sep. 2007. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhu et al., “New indolizidine- and pyrrolidine-type alkaloids with anti-angiogenic activities from Anisodus tanguticus,” Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, vol. 167, p. 115481, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Pyne et al., “A yeast platform for high-level synthesis of tetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloids,” Nat Commun, vol. 11, no. 1, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. J. Jiang, J. Q. Li, H. J. Zhang, W. J. Ding, and Z. J. Ma, “Cyclizidine-type alkaloids from Streptomyces sp. HNA39,” J Nat Prod, vol. 81, no. 2, pp. 394–399, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- W. Huang, S. J. Kim, J. Liu, and W. Zhang, “Identification of the polyketide biosynthetic machinery for the indolizidine alkaloid cyclizidine,” Org Lett, vol. 17, no. 21, pp. 5344–5347, Nov. 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Izumikawa, T. Hosoya, M. Takagi, and K. Shin-Ya, “A new cyclizidine analog JBIR-102 from Saccharopolyspora sp. RL78 isolated from mangrove soil,” Journal of Antibiotics, vol. 65, no. 1, pp. 41–43, Jan. 2012. [CrossRef]

- H. Tsutsumi et al., “Identification and analysis of the biosynthetic gene cluster for the indolizidine alkaloid iminimycin in Streptomyces griseus,” ChemBioChem, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Takahashi and T. Nakashima, “Actinomycetes, an inexhaustible source of naturally occurring antibiotics,” Antibiotics, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 1–17, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. O. Rogers and J. Birnbaum, “Biosynthesis of fosfomycin by Streptomyces fradiae.,” Antimicrob Agents Chemother, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 121–32, Feb. 1974.

- “WHO EML 22nd List (2021) | Enhanced Reader.”.

- J. V. McGowan, R. Chung, A. Maulik, I. Piotrowska, J. M. Walker, and D. M. Yellon, “Anthracycline chemotherapy and cardiotoxicity,” Cardiovasc Drugs Ther, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 63–75, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. J. Thompson and H. Seto, “Bialaphos,” Genetics and Biochemistry of Antibiotic Production, pp. 197–222, Jan. 1995. [CrossRef]

- S. Khan et al., “Biodiversity of actinomycetes and their secondary metabolites: A comprehensive review,” J. Adv. Biomed. & Pharm. Sci. J. Adv. Biomed. & Pharm. Sci, vol. 6, pp. 36–48, 2023, Accessed: Apr. 12, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://jabps.journals.ekb.eg.

- M. S. M. Selim, S. A. Abdelhamid, and S. S. Mohamed, “Secondary metabolites and biodiversity of actinomycetes,” Journal of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology, vol. 19, no. 1, p. 72, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Ezeobiora, N. H. Igbokwe, D. H. Amin, N. V. Enwuru, C. F. Okpalanwa, and U. E. Mendie, “Uncovering the biodiversity and biosynthetic potentials of rare actinomycetes,” Future Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2022 8:1, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 1–19, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Menezes et al., “Bioactive metabolites from terrestrial and marine actinomycetes,” Molecules 2023, Vol. 28, Page 5915, vol. 28, no. 15, p. 5915, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Gomi et al., “Isolation and structure of a new antibiotic, indolizomycin, produced by a strain SK2-52 obtained by interspecies fusion treatment,” J Antibiot (Tokyo), vol. 37, no. 11, pp. 1491–1494, 1984. [CrossRef]

- A. Freer, D. Gardner, D. Greatbanks, J. P. Poyser, and G. A. Sim, “Structure of cyclizidine (antibiotic M146791) : X -ray crystal structure of an indolizidinediol metabolite bearing a unique cyclopropyl side-chain,” J Chem Soc Chem Commun, vol. 0, no. 20, pp. 1160–1162, Jan. 1982. [CrossRef]

- F. J. Leeper, S. E. Shaw, and P. Satish, “Biosynthesis of the indolizidine alkaloid cyclizidine: incorporation of singly and doubly labelled precursors,” Can J Chem, vol. 72, no. 1, pp. 131–141, 2011. [CrossRef]

- J. Staunton, “The extraordinary enzymes involved in erythromycin biosynthesis,” Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English, vol. 30, no. 10, pp. 1302–1306, Oct. 1991. [CrossRef]

- C. T. Walsh, S. E. O’Connor, and T. L. Schneider, “Polyketide-nonribosomal peptide epothilone antitumor agents: the EpoA, B, C subunits,” J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol, vol. 30, no. 8, pp. 448–455, Aug. 2003. [CrossRef]

- Nivina, K. P. Yuet, J. Hsu, and C. Khosla, “Evolution and diversity of assembly-line polyketide synthases,” Chem Rev, vol. 119, no. 24, pp. 12524–12547, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Hanessian, U. Soma, S. Dorich, and B. Deschênes-Simard, “Total synthesis of (+)-ent -cyclizidine: Absolute configurational confirmation of antibiotic M146791,” Org Lett, vol. 13, no. 5, pp. 1048–1051, Mar. 2011. [CrossRef]

- S. Li, Y. J. Jiang, Z. Ma, and N. Wang, “Complete genome sequence of Streptomyces sp. HNA39, a new cyclizidine producer isolated from a South China Sea sediment,” Mar Genomics, vol. 70, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. W. Cheng, J. Q. Li, Y. J. Jiang, H. Z. Liu, and C. Huo, “A new indolizinium alkaloid from marine-derived Streptomyces sp. HNA39,” J Asian Nat Prod Res, 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Skehan et al., “New colorimetric cytotoxicity assay for anticancer-drug screening,” JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, vol. 82, no. 13, pp. 1107–1112, Jul. 1990. [CrossRef]

- M. Takagi and K. Shin-Ya, “New species of actinomycetes do not always produce new compounds with high frequency,” The Journal of Antibiotics, vol. 64, no. 10, pp. 699–701, Jul. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Schatz, E. Bugle, and S. A. Waksman, “Streptomycin, a substance exhibiting antibiotic activity against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria,” Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine, vol. 55, no. 1, pp. 66–69, Nov. 2016. [CrossRef]

- T. Nakashima et al., “Iminimycin A, the new iminium metabolite produced by Streptomyces griseus OS-3601,” The Journal of Antibiotics 2016 69:8, vol. 69, no. 8, pp. 611–615, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- T. Nakashima et al., “Absolute configuration of iminimycin B, a new indolizidine alkaloid, from S. griseus OS-3601,” Tetrahedron Lett, vol. 57, no. 30, pp. 3284–3286, Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. Tsutsumi et al., “Identification and analysis of the biosynthetic gene cluster for the indolizidine alkaloid iminimycin in Streptomyces griseus,” ChemBioChem, vol. 22, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).