1. Introduction

The diaphragm is a crucial muscle of ventilation and gas exchange process. The movement of this muscle creates morphological and functional alterations in the thoracic and abdominal cavities. Caudal and cranial movements of the diaphragm are associated with inspiration and expiration phases of respiration, respectively. Proper working of the diaphragm muscle is also important for expulsive actions such as coughing and sneezing which are necessary for airways clearing and maintaining its patency [

1,

2].

Like any other skeletal muscles in human body, the diaphragm can also be subjected to dysfunction. A numerous conditions (i.e., congenital defects, hernias, traumas, cardiothoracic surgeries, thoracic or abdominal pathologies) or systemic diseases (i.e., muscular dystrophies, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis) can directly affect the diaphragm leading to its weakness or/and paralysis, and in consequence reduce breathing capability and efficiently lungs aeration [

3,

4]. Previous studies reported presence of diaphragm disorders during viral infection course, such as human immunodeficiency virus [

5,

6], poliovirus [

7], West Nile virus [

8], dengue virus [

9], herpes zoster virus [

10] and Zika [

11].

SARS-CoV-2 is an RNA virus that has become a major public health threat. The clinical manifestations of COVID-19 infection vary, ranging from asymptomatic throughout mild and moderate symptoms, to serious clinical picture required intensive care [

12]. Many studies, focused on various aspects of this pandemic have been developed, but there is currently very limited informations about the nature and prevalence of post-COVID-19 symptoms. According to the literature, the large number of post-COVID-19 patients suffer from persistent dyspnea and fatigue, accompanied by some or much difficulty in walking, lifting, carrying, walking upstairs, and walking fast, even months after onset of disease [

13]. These first two respiratory symptoms are also among the top 5 post-COVID-19 symptoms [

14,

15]. Our study demonstrates the likelihood that diaphragm muscle dysfunction could be a major contributing factor of prolonged functional impairments. Hence, to fill the gap in existing literature we designed this study to identify and clarify possible impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on diaphragm muscle function.

The purpose of the study was to assess diaphragm muscle function among patients recovered from SARS-CoV-19 infection. We also strove: (I) to estimate the prevalence of diaphragm muscle dysfunction, (II) to establish causal relations between selected clinical variables and potential risk of diaphragm dysfunction, (III) to determine relationship of diaphragm functional parameters to physical functional capacity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Settings

A retrospective double-blind study was conducted at Physical Therapy Department at the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Administration's Specialist Hospital in Glucholazy (Poland). The study was approved by Institutional Review Board and the Ethics Committee of Silesian Medical University (Decision number: PCN/0022/KB1/09/21). All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants involved in the study. The authors had no access to information that could identify individual participants during or after data collection

2.2. Participants

A total of 114 participants, recovered from COVID-19 infection and qualified to three week post-covid rehabilitation program, were recruited. Patients were eligible for enrollment if they had at least one symptom during infection course (coughing, fever, dyspnea, loss of smell or taste) and SARS-CoV-2 infection were confirmed by RT-PCR (Real-Time reverse polymerase chain reaction) test of nasopharyngeal swabs. Participants were excluded from analysis due to presence of one or more following reasons: previous thoracic or/and abdominal surgery, presence of disease that interfere diaphragm function, previous participation in post-covid rehabilitation, difficulty to obtain clear view of diaphragm in ultrasound imaging, not complying to commands concerned breathing maneuvers during examination, presence of balance disorders what impeded ultrasound measurements in standing position. We also excluded participants who were no able to participate or finish 6-minute walk test. Finally, 46 patients were enrolled in the study.

2.3. Diaphragm Muscle Ultrasound

Diaphragm muscle function was evaluated using ultrasonography. The right and left hemidiaphragm was visualized through the liver and spleen window, respectively, in the zone of apposition area as a three-layer structure consisting of hyperechogenic lines of pleural and peritoneal membranes and the hypoechogenic layer of muscle itself. A high frequency (7-13 MHz) linear probe set to B mode was placed perpendicular to the chest wall in the midaxillary line, between the 8th and 10th intercostal space. In the situation of “lung curtain sign” artifact when the lung obliterated the muscle’s image, the operator moved the probe towards to the anterior axillary line or to caudal direction to the next intercostal space [

16,

17].

All measurements were performed with Sonoscape E1 ultrasound machine before beginning the physiotherapy process. Prior to measurements, the participants were given verbally instruction about breathing maneuvers to do. Based on literature review mentioned at the introduction chapter suggested that patients who underwent COVID-19 have respiratory problems especially during activity we decided to perform ultrasound not only in supine, but also at unsupported standing position. Ultrasonography examination were done by a well-trained specialist, who was blinded from the clinical data. Once a clear image of the diaphragm was obtained, the participant were asked to take a maximal inspiration (ThIns) and then exhale to end expiration (ThExp). On each frozen B-mode image, the diaphragm thickness was estimated as the vertical distance between pleural and peritoneal line. Three images for each position and for each side were collected, and the average value was included to statistical analysis [

16,

17].

From obtained diaphragm measurements we calculated the following diaphragm function indexes: (1) Diaphragm Thickness Fraction (DTF) reflecting the muscle effort (or strength?) was computed using the formula: DTF = thickness at end-inspiration—thickness at end-expiration/thickness at end-expiration x 100%, and the value less than 20% was interpreted as a hemidiaphragm paralysis; (2) Diaphragm Thickening Ratio (DTR), assessing a quality of muscle function, was calculated as the thickness at end-inspiration divided by the thickness at end-expiration; (3) We assumed an expiratory thickness less than 2 mm as a cutoff value for diaphragm muscle atrophy diagnosis; (4) „DTR module" and „DTF module" for supine and standing position were calculated to perform correlation analysis between DTR index and DTF index with clinical variables. We used following formulas: Module DTR = (Left ThIns/Left ThExp)/(Right ThIns/Right ThExp) and Module DTF = (left DTF + right DTF)/2. [

16,

17].

From all available diaphragm imaging techniques, we chose ultrasound examination as a non-invasive, valid and reliable tool to muscle action assessment. According to previous studies, sonography results correlate with the size of the diaphragm compound muscle action potential in response to phrenic nerve stimulation [

18], as well as, with inspiratory muscle strength and pulmonary function [

3,

19]. Ultrasound techniques have been also shown to outperform traditional techniques such as fluoroscopy in diagnosing diaphragm dysfunction [

20].

2.4. The mMRC (Modified Medical Research Council) Scale

The scale is a self-rating tool to assess severity of dyspnea during daily living activities. Questionnaire consists of five statements evaluating dyspnea degree graded on a scale from 0 (no breathlessness except on strenuous exercise) to 4 (complete incapacity to leave house or breathless when dressing or undressing) [

21].

2.5. The 6 Minute Walk Test

The 6 Minute Walk Test is a sub-maximal exercise test used to assess aerobic capacity and endurance. The patients were instructed that the purpose is to walk as far as possible during 6 minutes. In the present study test was performed using the updated methodology specified by the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society. The primary outcome measure was 6-minutes walk distance. Heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation and modified Borg scale assessing subjectively the degree of dyspnea graded from 0 to 10, were also collected at the beginning and at the end of the 6MWT [

22].

2.6. MET (The Metabolic Equivalent) Score

The MET is the objective measure of the ratio of the rate at which a person expends energy, relative to the mass of that person, while performing some specific physical activity compared to a reference, set by convention at 3.5 mL of oxygen per kilogram per minute, which is roughly equivalent to the energy expended when sitting quietly [

23].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The sociodemographic data, as well as, clinical signs and patients symptoms during COVID-19 course were collected from available medical records and separate questionnaire. We used a excel sheet to gather the all variables. Descriptive data are expressed as the mean ± Standard Deviation (including 95% Confidence Interval), and/or percentages. Comparisons between two groups for categorical variables were made using the χ 2 test or Fisher’s exact test, while for continuous variables were made using Student’s t test or the Mann–Whitney U test. Correlations analysis were made using Spearman correlation test. Data analysis was performed using PQStat software for Windows. P values lower than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. less than 0.05.

3. Results

The demographic data of the study participants and their clinical characteristics are shown in

Table 1. There were no differences between patients in terms of gender composition (p=0.382), age (p=0.069), BMI index (p=0.196), saturation (p=0.403), oxygen therapy use (p=0.461) and mMRC scale (p=0.113). None of the patients had had the disease twice before participated in this study.

Descriptive statistics of diaphragm functional parameters were presented at

Table 2. The vast majority of patients had worse inspiratory (right dome: 91.3%, n=42; left dome: 86.9%, n=40) and expiratory (right dome: 82.6%, n=38; left dome: 86.9%, n=40) diaphragm thickness at standing position compared to supine. The same dependence, although in lesser extent, concerned also diaphragm function indexes. Standing worsening of DTF index outcomes was showed at 63% (n=29) on the left and at 56.5% (n=26) on the right diaphragm dome, while left and right DTR decreased was manifested among 31(67.3%) and 33 (71.7%) patients, respectively.

Only a small number of subjects had left (n=6; 13%), right (n=6; 13%), and both-sided (n=3; 6.5%) diaphragm muscle paralysis. We detected 73.9% (n=34) patients with left side, 76% (n=35) with right side and 69.5% (n=32) with simultaneous both side diaphragm atrophy. We noted slightly greater number of individuals with diaphragm atrophy among males than females (75%, n=15 vs 65%, n=17; p=0.482), as well as, in patients who did not use oxygen therapy during COVID-19 course (77%, n=20 vs 60%, n=12; p=0.216). A particulary high percentage (p=0.205) of this type of diaphragm dysfunction was reported in subjects with normal weight (90.9%; n=10) determined by BMI index versus overweight (64.7%; n=11) and obesity (61.1%; n=11). Similar findings were demonstrated in relation to age, where the youngest patients group between 41 and 50 years were characterized by the highest number (88.8%, n=8) of diaphragm muscle mass thinning - compared to other age groups (51-60 years: 64.7%, n=11; 61-70 years: 61.5%, n=8, p=0.654).

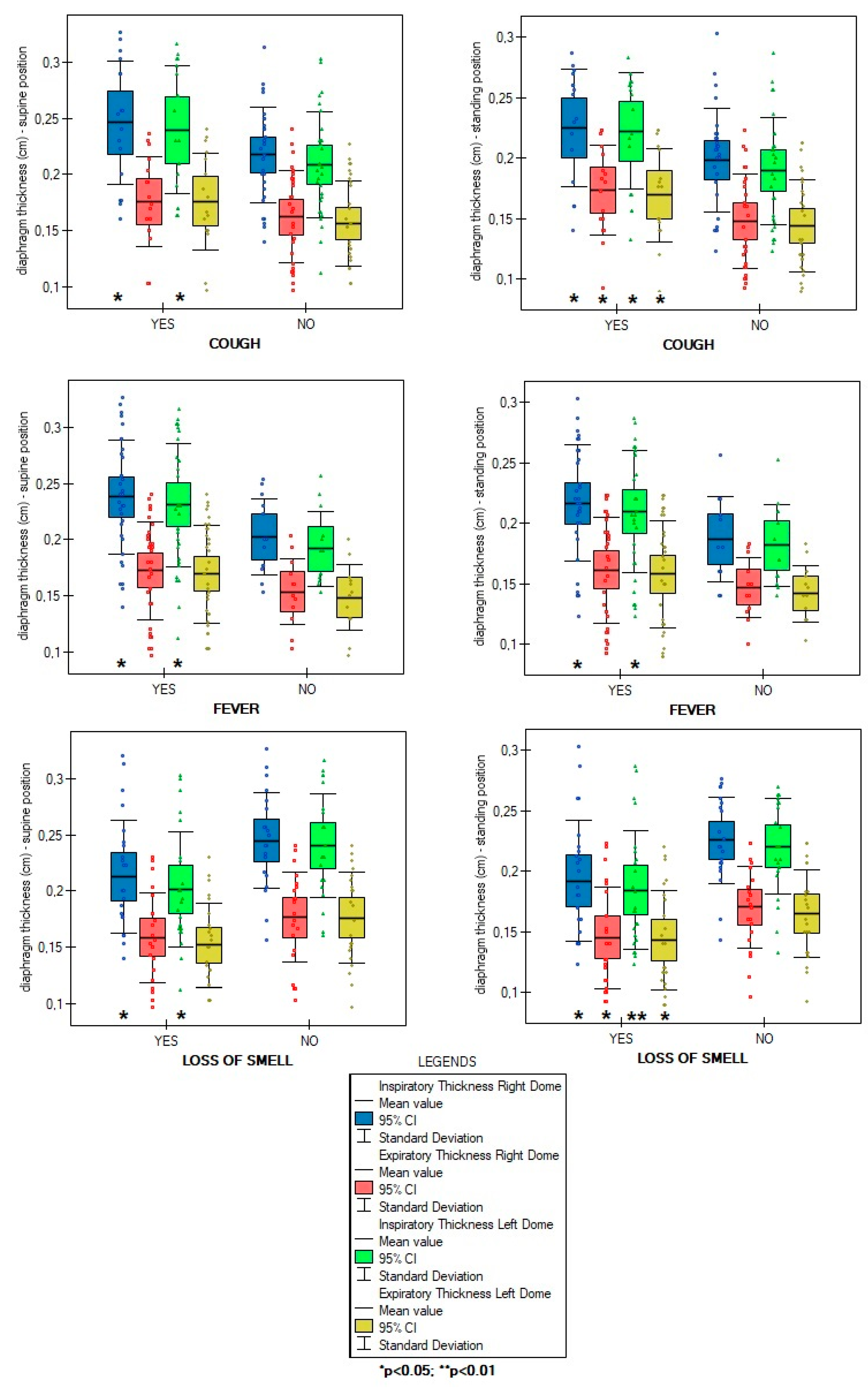

Overall number of symptoms during infection were not correlated with diaphragm function parameters in supine (ThIns: r=0.003, p=0.981; ThEx: r=0.104, p=0.488; DTF:r=-0.143, p=0.345; DTR: r=-0.144, p=0.338) and standing position (ThIns: r=-0.023, p=0.8798; ThExp: r=0.072, p=0.631; DTF: r=-0.140, p=0.357; DTR: r=-0.144, p=0.338). Of all analysed disease symptoms, only patients with presence of cough, fever and without loss of smell during COVID-19 course had a significantly greater values of diaphragm inspiratory thickness in supine position, as well as, greater inspiratory and expiratory thickness at standing position - compared to participants without mentioned above symptoms (

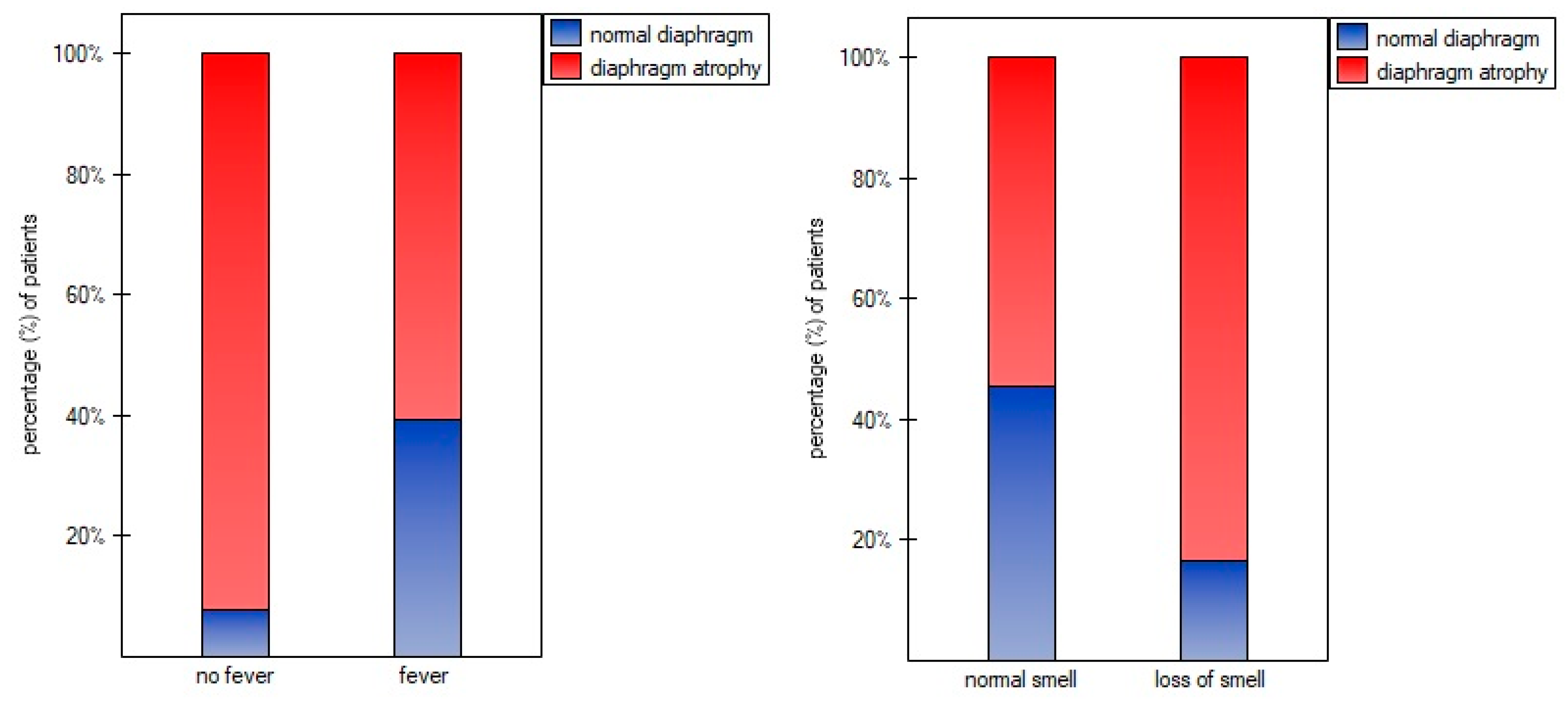

Figure 1). Furthermore, at

Figure 2 we found significantly lower percentage of diaphragm atrophy among participants with fever (p=0.0353) and without smell disorders (0.0340).

In further analysis, we compared diaphragm parameters relation to a number of statistically significant COVID-19 symptoms occured among patients during the disease. For this purpose we divided participants into 4 categories: subgroup I (presence of only 1 symptom: cough, fever, or loss of smell; n=16, 34.8%), subgroup II (presence of 2 from 3 symptoms; n=24, 52.2%), subgroup III (all 3 symptoms presented; n=3), subgroup IV (none of 3 symptoms reported; n=3, 6.5%). Due to small sample size of subgroups III and IV, we compared diaphragm parameters only between subgroups I and II. We found no differences, neither in the case of inspiratory (supine: p=0.622, standing: p=0.723) and expiratory thickness (supine: p=0.489, standing: p=0.648), nor in the case of DTF (supine: p=0.431, standing: p=0.781) and DTR index (supine: p=0.422, standing: p=0.657). In case of atrophy, simultaneous presence of fever and smell loss was also not more associated with a lower risk of diaphragm atrophy than single symptom occurence (p=0.4802).

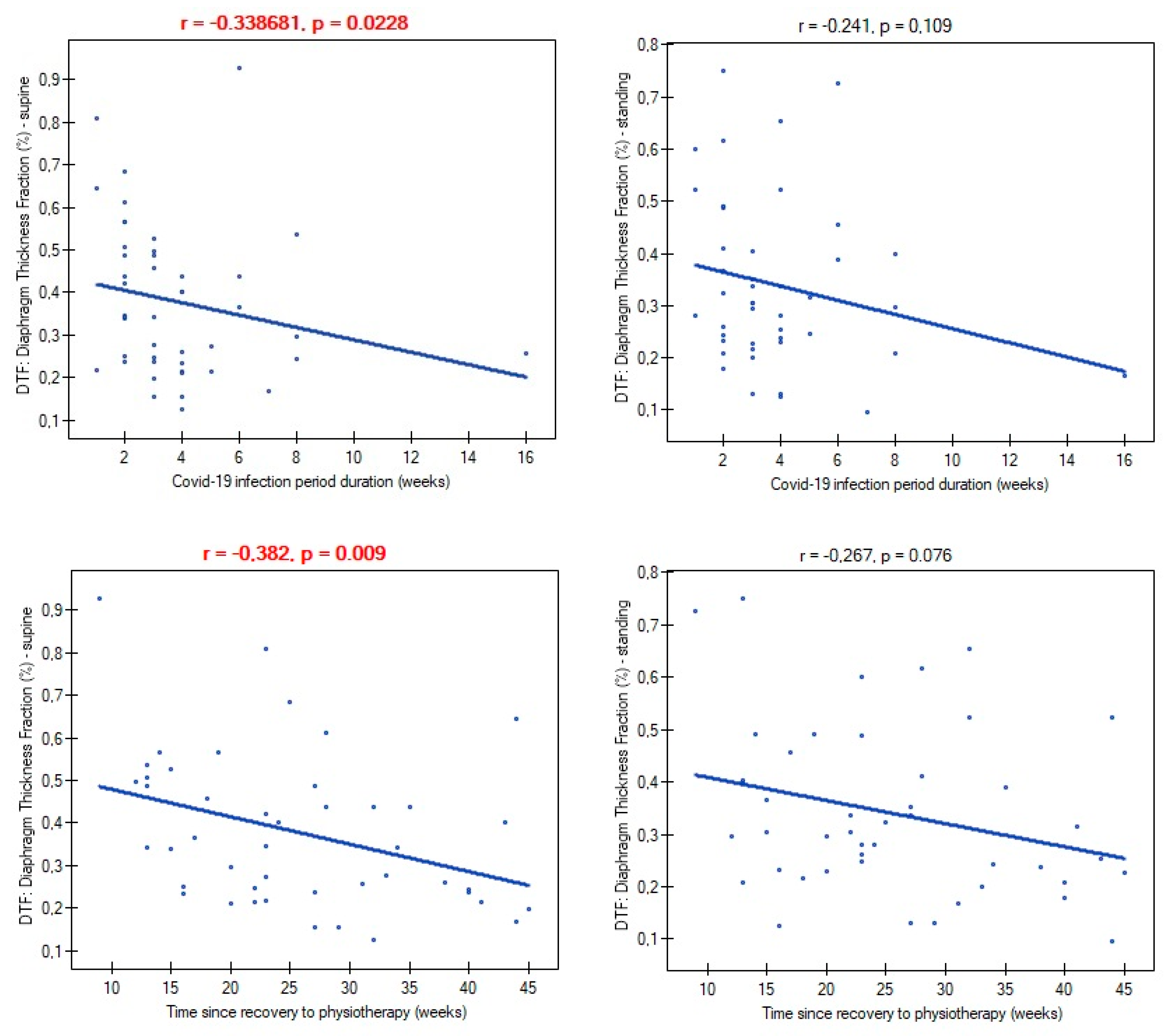

Mild and moderate severity of COVID-19 disease did not differentiate participants in terms of atrophy risk (mild: 66.6%; moderate: 70.9%; p=0.782), supine diaphragm ultrasound measurements (ThIns: p=0.684; ThExp: p=0.956; DTF: p=0.727; DTR: p=) and standing diaphragm ultrasound measurements (ThIns: p=0.597; ThExp: p=0.924; DTF: p=0.365; DTR: p=0.424). There were also no relationships between time of infection duration and diaphragm thickness both at supine (ThIns: r=0.022, p=0.880; ThExp: r=0.151, p=0.314) and standing position (ThIns: r=-0.087, p=0.563; ThExp: r=0.002, p=0.986). Likewise, time since recovery showed no association with muscle thickness (ThIns: r=-0,167, p=0.266; ThExp: r=0.019, p=0.899) (ThIns: r=-0.190, p=0.205; ThExp: r=-0.056, p=0.707). In contrast, both variables had an impact on values of DTF index (

Figure 3).

To further analysis of time variables, we split data into lower quartile (Q1), median quartile (Q2) and upper quartile (Q3). We found no differences in the proportion of diaphragm atrophy due to time of infection duration (p=0.810): < 2 weeks (75%, n=12), 3-4 weeks (65%%, n=13), over 4 weeks (70%, n=7), as well as, time since recovery to start physiotherapy (p=0.713): < 17 weeks (61.5%, n=9); 18-32 weeks (75%, n=15); over 32 weeks (61.5%, n=8).

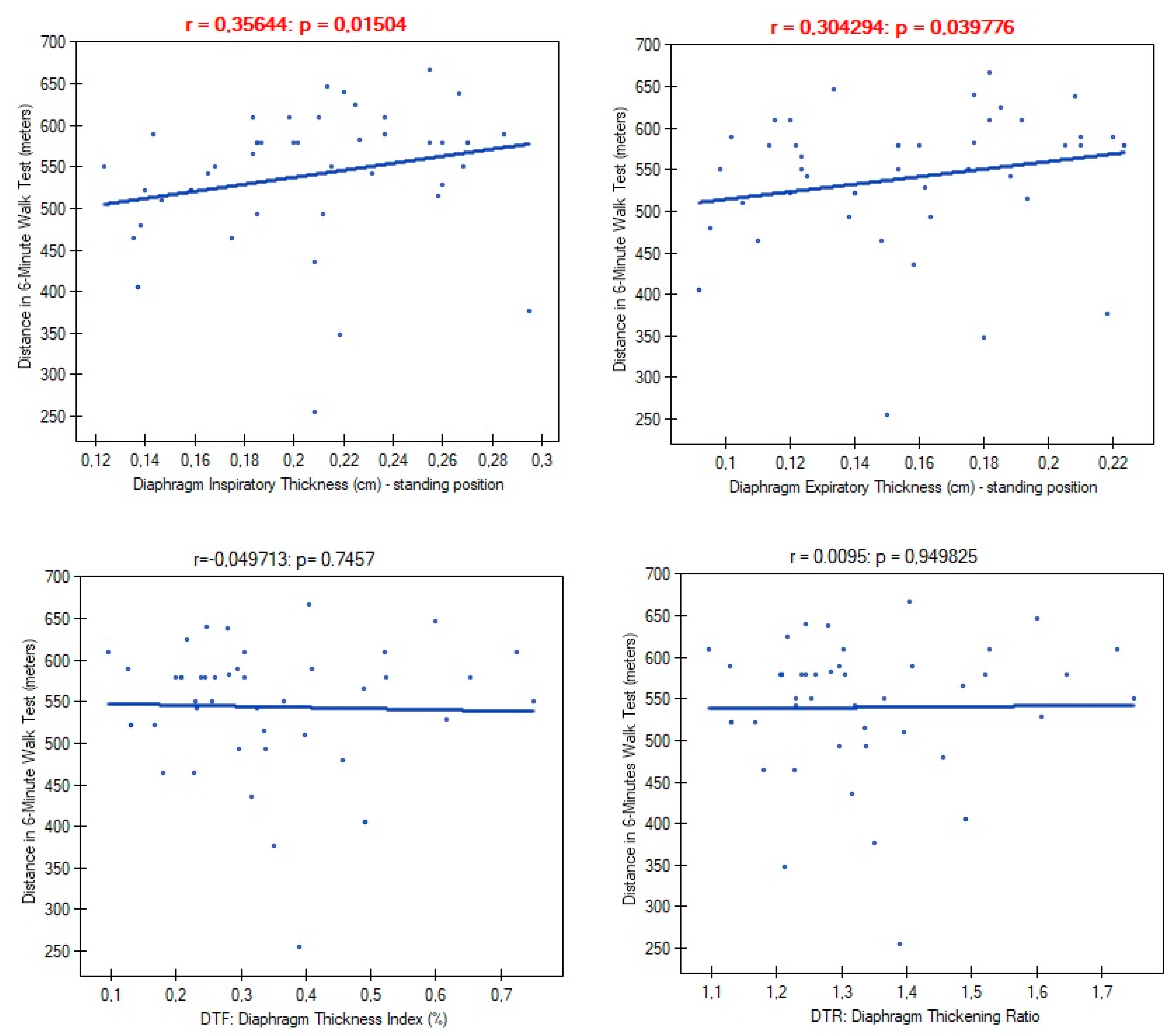

In further analysis we examined links between diaphragm functional parameters and person's exercise tolerance. We found significant correlations of diaphragm muscle thickness with distance obtained in 6-minute walk test (

Figure 4).

6-MWT derived variables such as saturation level after test, exertion and dyspnoea level measured in Borg scale and metabolic equivalent of task showed also dependence from diaphragm muscle mass (

Table 3).

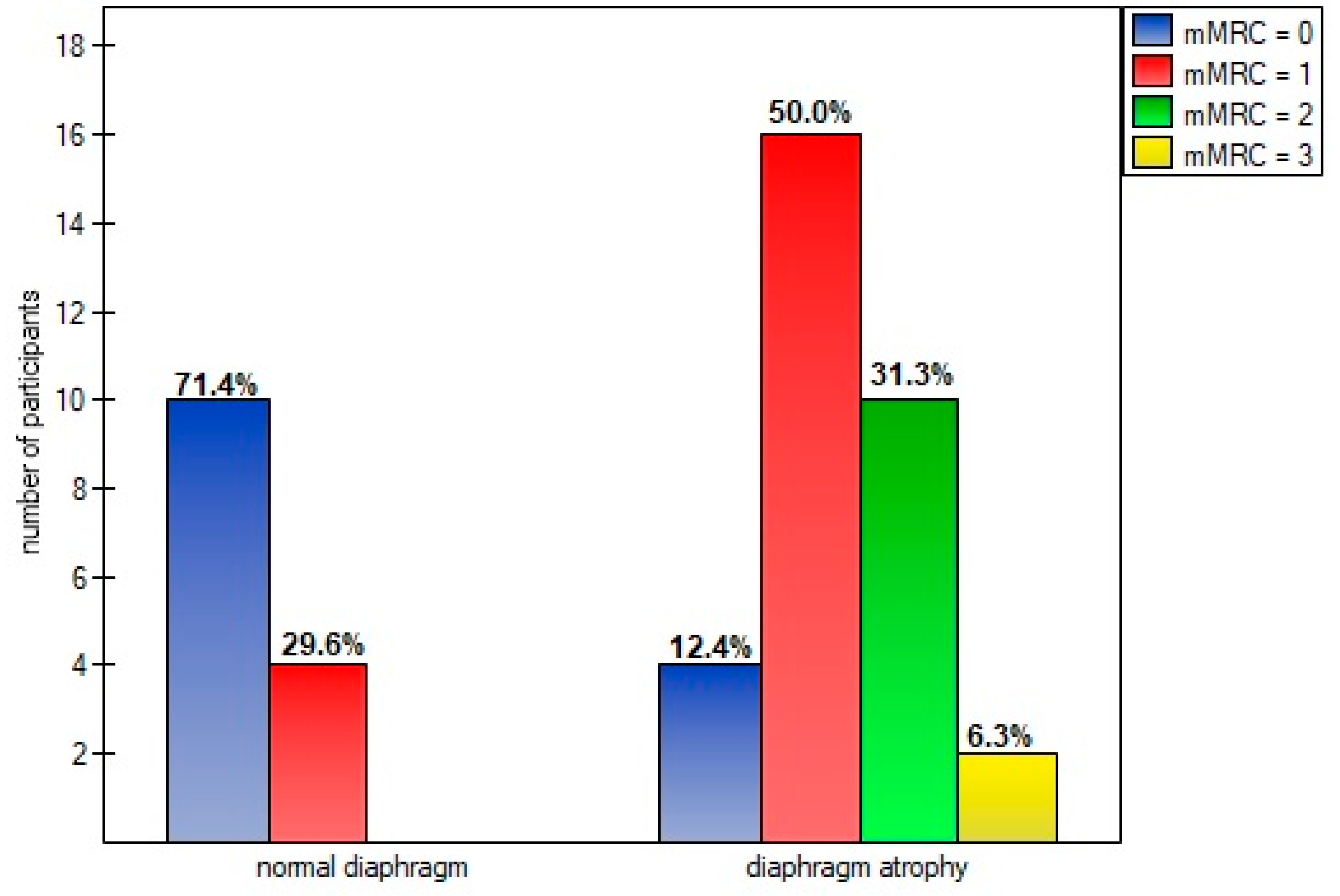

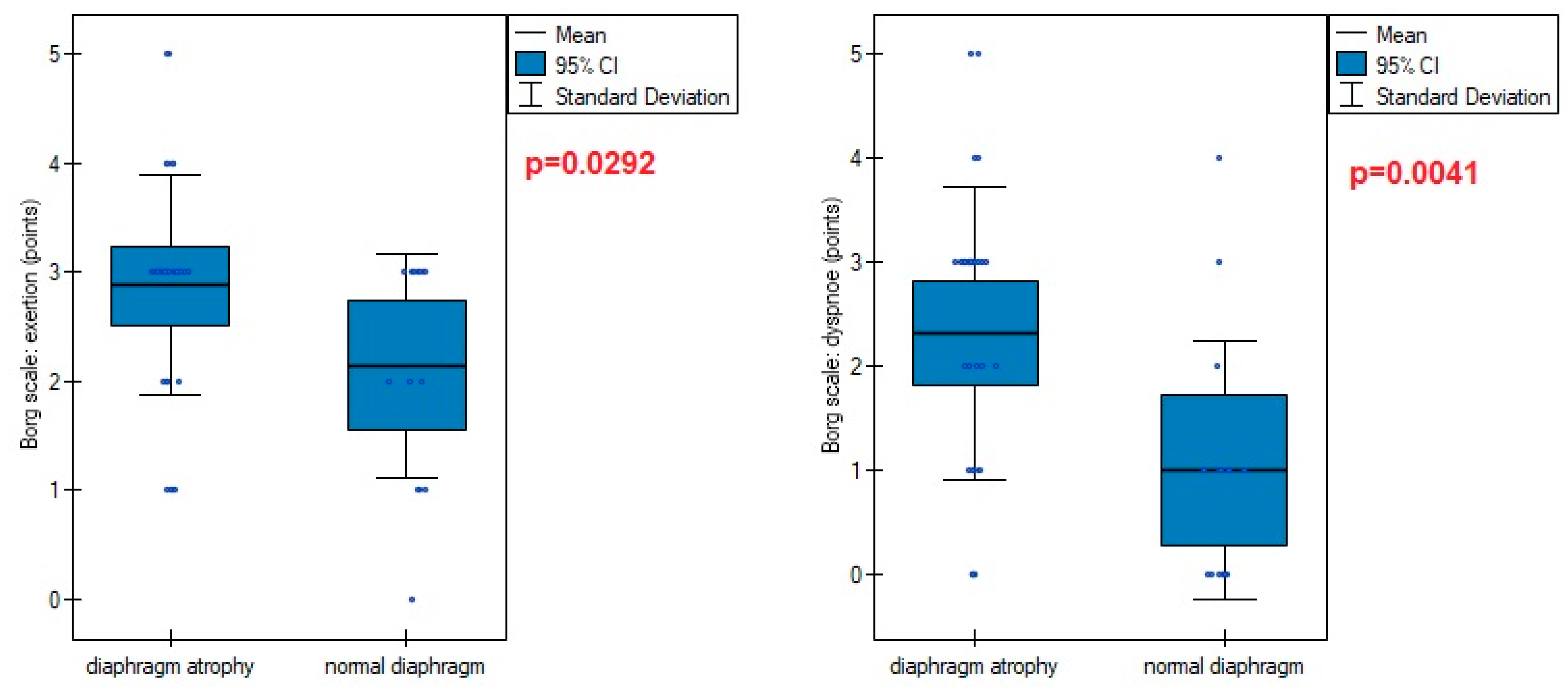

Diaphragm muscle atrophy strongly contributed (p=0.0005) to functional dyspnea during activity of daily living measured in mMRC scale (

Figure 5). This was also evident in higher points obtained in the Borg scale in persons with an atrophic diaphragm compared to subjects without dysfunction (

Figure 6).

However, there was no differences in saturation before test (95.30 vs 95.00; p=0.5910), saturation after test (95.68 vs 94.78, p=0.1411), MET (7.16 vs 7.81; p=0.2956), and 6-minute test distance (530.71 vs 559.92; p=0.2786).

4. Discussion

The pathophysiology of COVID-19 infection is not just limited to the lungs, but causes a cascade of systemic events, affecting various organs and tissues. To date, a several studies tried to determine impact of SARS-CoV-2 to diaphragm muscle. Imamovic et al., described an incidence of diaphragmatic rupture as a late consequence of the underwent SARS-CoV-2 infection [

24]. Shi et al., demonstrated distinct myopathic changes in the diaphragm muscle specimens of deceased COVID-19 patients. Autopsies from 26 patients showed an increased expression of angiotensin I-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in the diaphragm (predominantly localized at the myofiber membrane) as well as, a two-fold higher degree of epimysial and perimysial fibrosis in the postmortem diaphragms of COVID-19 patients admitted to ICU compared with non-covid ICU control group, with comparable duration of mechanical ventilation and ICU length of stay. Authors concluded that these histological changes may have an impact to the diaphragm contractility and contribute to the chronic sensation of dyspnoea and fatigue [

25]. However, at the base of this study it is unclear whether such diaphragm tissue changes are present in SARS-CoV-2 survivors. Indirect confirmations of this assumption is contained in other studies. Deboer and colleagues found an inverse correlation between diaphragm muscle strength and breathlessnes after recovery what may point to diaphragm fibrosis [

26]. Formenti et al., demonstrated a significantly lower echogenicity of diaphragm muscle in ultrasound among patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome arising from COVID-19 compared to non-survivors [

27].

Not just structural, but also functional diaphragm disorders were reported in literature. Several studies demonstrated cases of unilateral or/and bilateral diaphragm paralysis due to active SARS-CoV-2 infection [

28,

29,

30,

31]. Borroni described two cases of diaphragmatic myoclonus as neurological manifestation of SARS-CoV-2 infection with not accompanied by evidence of structural damage of the central nervous system [

32]. Satici et al., detected diaphragm elevation among patients with persistent dyspnea without lung parenchymal involvement, who recovered from COVID-19, as well as, decreased diaphragm excursion in most patients [

33]. Other researchers reported that diaphragmatic movement predict successful weaning in patients with COVID-19. The study included 22 patients with severe COVID-19 who were invasively mechanically ventilated for 2 days or more. A patient with diaphragmatic excursion > 12 mm during the spontaneous breathing trial is unlikely to be re-intubated [

34]. Umbrello et al., observed that both diaphragm sizes were significantly reduced at day 7 from ICU admission in COVID-19 patients. Significantly greater reduction were reported in non-survivors compared to survivors [

35]. Corradi et al., identified low diaphragm thickness fraction index as a predictor of Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) failure, as its values were inversely correlate with its success (the lower the DTF values, the more likely the CPAP failure) [

36]. In another study, the same authors examined 77 patients underwent diaphragm ultrasonography within 36 hours from admission. They found that low diaphragm thickness was independent predictor of adverse outcomes in COVID-19 patients, with the end-expiratory diaphragm thickness being the strongest [

37]. Similar Van Steveninck et al., described the case of low value of diaphragm thickness prior to patient intubation, while respiratory failure was not yet evident from arterial blood gas analysis in patients with COVID-19 with pneumonia [

38].

Results of our study add a new knowledge in this field and should contribute to an even better understanding of the pathophysiology and treatment of respiratory muscle pathology after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Data contained in

Table 2 indicate a low inspiratory and expiratory diaphragm thickness, as well as, a very low diaphragm thickness fraction (DTF). Importantly, patients presented worse outcomes at standing position - compared to supine, where abdominal wall is relaxed and resistance from visceral organs lower. It suggests impairment of diaphragm muscle contraction force and its ability to work properly during physical effort. The best illustration of the dysfunction scale is comparing the results obtained here with the values of healthy subjects, where the normal percentage of thickening was 65% in supine (36% in our study) and 174% in standing (32% in our study). This poor diaphragm contractility was strongly linked with parameters of physical functional capacity (

Table 3). The low inspiratory and expiratory diaphragm thickness in standing position corresponded with less distance obtained by patient during 6-minute walk test. In addition, patients with low DTF index values felt higher level of dyspnea and exertion on the Borg scale after performed test. Values of DTF index were also strongly negatively correlated with low oxygen saturation level measured after the test. We found no association of DTF index with resting oxygenation. This indicates that, despite its thinning, diaphragm fulfills primary function of ensuring gas exchange at rest, but after the infection it is so weak to perform optimal ventilation process during physical exertion.

In our study almost 85% of COVID-19 survivors qualified to physiotherapy programm had at least one sonographic abnormality of diaphragm muscle function. This finding are consistent with previous study conducted by Farr et al.l. [

39]. The vast majority of this dysfunctions was atrophy (69.5%) - unlike the other viral diseases described in literature that caused diaphragm paralysis [5-11]. Impact of diaphragm muscle thinning revealed particularly evident in degree of disability that breathlessness posed on day-to-day activities. Significantly higher percentage of patients classified subjectively perceived respiratory disability to first, second or third class of dyspnoe in mMRC scale than patients with normal musclar cross-section (

Figure 4). Reducing of diaphragm muscle mass affected also higher exertion and dyspnoe after 6-minute test - compared to non-atrophic patients.

Mittal et al., suggested that the cytokine storm following the SARS-CoV-2 entry the circulatory system, interacts with skeletal muscle, and may cause damage to the diaphragm and other respiratory muscles. This may lead to muscle dysfunction, atrophy, or injury [

40]. In our study we determined several factors that significantly contributed to diaphragm dysfunction or prevented its occurrence. Patients who during infection course were characterized by the presence of cough, fever and normal olfaction had a greater inspiratory muscle thickness compared to patients without these symptoms (

Figure 1). Fever and normal olfactory plays also protective role against diaphragm atrophy (

Figure 2). However, patients who reported presence of 2 from 3 symptoms (cough, fever, normal smell) had no greater inspiratory and expiratory thickness than patients with a single symptom from mentioned. Similarly, simultaneous presence of fever and lack of smell disorders were no associated with lower rate of atrophy than the presence of a single symptom. It suggests that occurence of only one symptom is enough to provide proper work of main respiratory muscle and protect against decrease muscle mass during COVID-19 infection course. The explanation of the influence of these factors should be sought in human physiology. Diaphragm muscle is involved in non-ventilatory expulsive behaviors. Cough mechanism causes diaphragm contraction, therefore, frequent coughs during infection seems prevent muscle thinning by stimulation it to contraction. In case of fever, a higher respiratory rate per minute seems to be of importance. It is much more difficult to explain the relationship of smell disorders with reduce diaphragm muscle mass. Previous study reported that odor stimuli change respiratory patterns. Unpleasant odors decrease tidal volume and increase respiratory frequency, resulting in a rapid and shallow breathing pattern. We suppose that anosmia during COVID-19 course could have caused similar changes in respiratory rhythm, thereby causing decrease of diaphragm muscle mass.

Previous studies have shown the presence of diaphragm atrophy in the severe and critical stage of the COVID-19 course [

39]. We added new knowledge in this field, demonstrating the presence of this type of diaphragm dysfunction also in people with a mild and moderate course. This allows to conclude that atrophy occurs independently of infection severity, with the exception of asymptomatic patients. Time of infection had no impact on inspiratory and expiratory diaphragm thickness, as well as, on percentage of atrophy diagnosis. However, longer time of infection was associated with greater impairment of diaphragm contractility measured by DTF index. Similar relationship was noted between time since recovery and magnitude of diaphragm contractility. Taking into consideration that our patients had no previous physiotherapy, as well as, time from recovery to start physiotherapy (mean 22 weeks) was negatively correlated with DTF index we can state that is not a temporary dysfunction that resolves spontaneously over time, but it turns into a chronic problem with a visible tendency to aggravate the problem in the absence of physiotherapy. Breathing alone seems to be also insufficient to regain the decreased muscle mass.

The strength of our study is comprehensive ultrasound diaphragm muscle function assessment and refered it to many of clinical variables in the course of COVID-19 what allow to obtain full clinical picture of this problem. We took into account that many of patients experience dyspnoe and fatigue during less or more intensive physical activity. To obtain the most reliable results we performed ultrasound assessment not only in supine position, but also at standing position. However, our study has one limitation. Despite measurements in two positions we were not able to detect percentage of atrophy and paralysis of diaphragm in standing position. The reason is a gap in medical literature, where a cut-off value for detect atrophy were described only in refer to a supine position. In our opinion, this does not affect the results of the research presented with the percentage of atrophy may be higher and correlations are even more statistically significant.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the diaphragm muscle dysfunction is a very common and serious long-term post-covid aftermath contributing to prolonged functional impairments. Respiratory rehabilitation should led to improvement in respiratory function and should be implemented at early recovery stage.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K., M.R., J.S., M.A.; methodology, J.K., M.A and J.S.; formal analysis, J.K. and M.R.; investigation, J.K., M.R., J.S., K.B., M.A.; resources, J.S. and K.B.; data curation, J.K. and M.R.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K.; writing—review and editing, M.A.; supervision, J.S. and M.A.; project administration, J.K., K.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Silesia, Katowice, Poland (protocol code: PCN/0022/KB1/09/21; date of approval: 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kocjan, J.; Adamek, M.; Gzik-Zroska, B.; Czyżewski, D.; Rydel, M. Network of breathing. Multifunctional role of the diaphragm: a review. Adv Respir Med 2017, 85, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bordoni, B.; Zanier, E. Anatomic connections of the diaphragm: influence of respiration on the body system. J Multidiscip Healthc 2013, 6, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCool, F.D.; Tzelepis, G.E. Dysfunction of the diaphragm. N Engl J Med. 2012, 366, 932–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricoy, J.; Rodríguez-Núñez, N.; Álvarez-Dobaño, J.M.; Toubes, M.E.; Riveiro, V.; Valdés, L. Diaphragmatic dysfunction. Pulmonology 2019, 25, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melero, M.J.; Mazzei, M.E.; Bergroth, B.; Cantardo, D.M.; Duarte, J.M.; Corti, M. Bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis in an HIV patient: Second reported case and literature review. Lung India. 2014, 31, 149–151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huh, S.; Chung, J.H.; Kwon, H.J.; Ko, H.Y. Unilateral Diaphragm Paralysis Associated With Neurosyphilis: A Case Report. Ann Rehabil Med 2020, 44, 338–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudrappa, M.; Kokatnur, L.; Chernyshev, O. Neurological Respiratory Failure. Diseases 2018, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betensley, A.D.; Jaffery, S.H.; Collins, H.; Sripathi, N.; Alabi, F. Bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis and related respiratory complications in a patient with West Nile virus infection. Thorax 2004, 59, 268–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratnayake, E.C.; Shivanthan, C.; Wijesiriwardena, B.C. Diaphragmatic paralysis: a rare consequence of dengue fever. BMC Infect Dis 2012, 12, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oike M, Naito T, Tsukada M, Kikuchi Y, Sakamoto N, Otsuki Y, et al. A case of diaphragmatic paralysis complicated by herpes-zoster virus infection. Intern Med 2012, 51, 1259–1263. [CrossRef]

- van der Linden V, Lins OG, de Lima Petribu NC, de Melo ACMG, Moore J, Rasmussen SA, et al. Diaphragmatic paralysis: Evaluation in infants with congenital Zika syndrome. Birth Defects Res. 2019, 111, 1577–1583. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu L, Wang B, Yuan T, Chen X, Ao Y, Fitzpatrick T, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect 2020, 80, 656–665. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs LG, Gourna Paleoudis E, Lesky-Di Bari D, Nyirenda T, Friedman T, Gupta A, et al. Persistence of symptoms and quality of life at 35 days after hospitalization for COVID-19 infection. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0243882.

- Malik P, Patel K, Pinto C, Jaiswal R, Tirupathi R, Pillai S, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome (PCS) and health-related quality of life (HRQoL)-A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol 2022, 94, 253–262. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halpin SJ, McIvor C, Whyatt G, Adams A, Harvey O, McLean L, et al. Postdischarge symptoms and rehabilitation needs in survivors of COVID-19 infection: A cross-sectional evaluation. J Med Virol 2021, 93, 1013–1022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarwal, A.; Walker, F.O.; Cartwright, M.S. Neuromuscular ultrasound for evaluation of the diaphragm. Muscle Nerve 2013, 47, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boussuges, A.; Rives, S.; Finance, J.; Brégeon, F. Assessment of diaphragmatic function by ultrasonography: Current approach and perspectives. World J Clin Cases 2020, 8, 2408–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, S.; Pinto, A.; de Carvalho, M. Phrenic nerve studies predict survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clin Neurophysiol 2012, 123, 2454–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, L.Z.; Santana, P.V.; Caruso, P.; Ribeiro de Carvalho, C.R.; Pereira de Albuquerque, A.L. Diaphragmatic Ultrasound Correlates with Inspiratory Muscle Strength and Pulmonary Function in Healthy Subjects. Ultrasound Med Biol 2018, 44, 786–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, J.G.; Fleet, M.; Cowan, M.D.; McMillan, N.C. Comparison of ultrasound with fluoroscopy in the assessment of suspected hemidiaphragmatic movement abnormality. Clin Radiol 1995, 50, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahler, D.A.; Wells, C.K. Evaluation of clinical methods for rating dyspnea. Chest 1988, 93, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh SJ, Puhan MA, Andrianopoulos V, Hernandes NA, Mitchell KE, Hill CJ, et al. An official systematic review of the European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society: measurement properties of field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur Respir J 2014, 44, 1447–1478. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000, 32, S498–S504. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamović A, Wagner D, Lindenmann J, Fink-Neuböck N, Sauseng S, Bajric T, et al. Life threatening rupture of the diaphragm after Covid 19 pneumonia: a case report. J Cardiothorac Surg 2022, 17, 145. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi Z, de Vries HJ, Vlaar APJ, van der Hoeven J, Boon RA, Heunks LMA, et al. Dutch COVID-19 Diaphragm Investigators. Diaphragm Pathology in Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19 and Postmortem Findings From 3 Medical Centers. JAMA Intern Med 2021, 181, 122–124. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Boer W, Veldman C, Steenbruggen I, Patberg KW, Van Den Berg J. Diaphragm strength in COVID-19 patients and breathlessness. Eur Respir J 2021, 58, OA4344.

- Formenti P, Umbrello M, Castagna V, Cenci S, Bichi F, Pozzi T, et al. Respiratory and peripheral muscular ultrasound characteristics in ICU COVID 19 ARDS patients. J Crit Care 2022, 67, 14–20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FitzMaurice, T.S.; McCann, C.; Walshaw, M.; Greenwood, J. Unilateral diaphragm paralysis with COVID-19 infection. BMJ Case Rep 2021, 14, e243115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahid, M.; Ali Nasir, S.; Shahid, O.; Nasir, S.A.; Khan, M.W. Unilateral Diaphragmatic Paralysis in a Patient With COVID-19 Pneumonia. Cureus 2021, 13, e19322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandawate, N.; Humphreys, C.; Gordan, P.; Okin, D. Diaphragmatic paralysis in COVID-19: a rare cause of postacute sequelae of COVID-19 dyspnoea. BMJ Case Rep 2021, 14, e246668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, C.; Garg, A.; Fakih, R.; Hamzeh, N.Y. Bilateral diaphragmatic dysfunction: A cause of persistent dyspnea in patients with post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2. SAGE Open Medical Case Reports. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borroni B, Gazzina S, Dono F, Mazzoleni V, Liberini P, Carrarini C, et al. Diaphragmatic myoclonus due to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Neurol Sci 2020, 41, 3471–3474. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satici, C.; Aydin, S.; Tuna, L.; Köybasi, G.; Koşar, F. Electromyographic and Sonographic Assessment of Diaphragm Dysfunction in Patients Who Recovered from the COVID-19 Pneumonia. Tuberk Toraks 2021, 69, 425–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmy, M.A.; Magdy Milad, L.; Osman, S.H.; Ali, M.A.; Hasanin, A. Diaphragmatic excursion: A possible key player for predicting successful weaning in patients with severe COVID-19. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med 2021, 40, 100875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umbrello M, Guglielmetti L, Formenti P, Antonucci E, Cereghini S, Filardo C, et al. Qualitative and quantitative muscle ultrasound changes in patients with COVID-19-related ARDS. Nutrition 2021, 91–92, 111449. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corradi F, Vetrugno L, Orso D, Bove T, Schreiber A, Boero E, et al. Diaphragmatic thickening fraction as a potential predictor of response to continuous positive airway pressure ventilation in Covid-19 pneumonia: A single-center pilot study. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2021, 284, 103585.

- Corradi F, Isirdi A, Malacarne P, Santori G, Barbieri G, Romei C, et al. UCARE (Ultrasound in Critical care and Anesthesia Research Group). Low diaphragm muscle mass predicts adverse outcome in patients hospitalized for COVID-19 pneumonia: an exploratory pilot study. Minerva Anestesiol 2021, 87, 432–438.

- van Steveninck AL, Imming LM. Diaphragm dysfunction prior to intubation in a patient with Covid-19 pneumonia; assessment by point of care ultrasound and potential implications for patient monitoring. Respir Med Case Rep 2020, 31, 101284.

- Farr E, Wolfe AR, Deshmukh S, Rydberg L, Soriano R, Walter JM, et al. Diaphragm dysfunction in severe COVID-19 as determined by neuromuscular ultrasound. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2021, 8, 1745–1749. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, A.; Dua, A.; Gupta, S.; Injeti, E. A research update: Significance of cytokine storm and diaphragm in COVID-19. Curr Res Pharmacol Drug Discov 2021, 2, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).