Submitted:

12 December 2024

Posted:

12 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design

Participants

Procedures

Variables and Outcomes

Variables

Outcomes

Data Analysis

3. Results

| Overall n = 223 (100) | MIP/MEP abnormal values * n=121 (54.2) |

MIP/MEP normal values * n=102 (45.8) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, years [IQR] | 67 (57 – 75) | 67 (59 – 74) | 65 (55 – 75) | 0.11 |

| Male gender, no. [%] | 153 (68.6) | 76 (62.8) | 77 (75.5) | 0.04 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian, n [%] | 218 (97.8) | 118 (97.5) | 100 (98) | 0.99 |

| Black, n [%] | 4 (1.8) | 2 (1.7) | 2 (2) | 0.99 |

| Asian, n [%] | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 0.99 |

| Smoking history | ||||

| Current smoker, no. [%] | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1) | 0.99 |

| Former smoker, no. [%] | 88 (39.5) | 51 (42.1) | 37 (36.2) | 0.41 |

| Non-smoker, no. [%] | 133 (59.6) | 69 (57) | 64 (62.7) | 0.41 |

| BMI (pre-admission), median [IQR] | 30 (27 – 34) | 30 (27 – 34) | 30 (27 – 34) | 0.64 |

| BMI >30, no. [%] | 121 (54.3) | 68 (56.2) | 53 (52) | 0.21 |

| Outcomes | ||||

| LOS, days [IQR] | 14 (10 – 21) | 15 (11 – 23.5) | 13 (9 – 19.3) | 0.14 |

| Respiratory support | ||||

| HFNC, no. [%] | 60 (26.9) | 32 (26.4) | 28 (27.5) | 0.88 |

| NIV, no. [%] | 74 (33.2) | 48 (39.7) | 26 (25.5) | 0.03 |

| Intubation/MV, no. [%] | 36 (16.1) | 21 (17.4) | 15 (14.7) | 0.72 |

| Use of Tocilizumab | 150 (67.3) | 79 (65.3) | 71 (69.6) | 0.47 |

| Use of Dexamethasone | 67 (30) | 37 (16.6) | 30 (13.4) | 0.88 |

| Use of other corticosteroids (oral/IV) | 134 (60.1) | 73 (60.3) | 61 (59.8) | 0.99 |

| O2 at discharge, no. [%] | 32 (14.3) | 19 (15.7) | 13 (12.75) | 0.57 |

| Follow up | ||||

| Dyspnea grade (mMRC), median [IQR] | 0 (0 – 1) | 0 (0 – 1) | 0 (0 – 1) | 0.09 |

| Dyspnea as mMRC ≥ 1, no. [%] | 67 (30) | 39 (32.2) | 28 (27.5) | 0.46 |

| FEV1/FVC, % [IQR] | 82 (78 – 85.7) | 81.8 (78.7 – 86.3) | 82.1 (78.1 – 85.1) | 0.78 |

| TLC, %pred [IQR] | 105 (94 – 116) | 101 (91.5 – 113) | 107.5 (96.8 – 117) | 0.06 |

| TLC <90%pred, no. [%] | 38 (17) | 27 (22.3) | 11 (10.8) | 0.03 |

| DLCO, %pred [IQR] | 77 (67 – 87) | 75 (64.5 – 86) | 79.5 (68 – 92.3) | 0.02 |

| DLCO <80%pred, no. [%] | 128 (57.4) | 77 (63.6) | 51 (50.5) | 0.06 |

| MIP, %pred [IQR] | 84 (66 – 104) | 68 (58 – 73) | 102 (90 – 120) | <0.0001 |

| MEP, %pred [IQR] | 82 (62 – 93) | 65 (54 – 72) | 96 (88 – 101) | <0.0001 |

| Reduced strength in dominant hand, no. [%] | 60 (26.9) | 40 (33.1) | 20 (19.6) | 0.034 |

| Reduced strength in right hand, no. [%] | 68 (30.5) | 46 (38) | 22 (21.6) | 0.01 |

| Reduced strength in left hand, no. [%] | 77 (34.5) | 46 (38) | 31 (30.4) | 0.26 |

3.1.1. Prevalence of MIP/MEP Dysfunction and Related Risk Factors

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | OR | 95% Confidence Interval | p value | OR | 95% Confidence Interval | p value |

| Age | 1.02 | 0.99 – 1.04 | 0.12 | |||

| Female sex | 0.54 | 0.3 – 0.98 | 0.04 | 0.51 | 0.28 – 0.91 | 0.03* |

| Smoking status (active/former) | 1.19 | 0.91 – 1.55 | 0.20 | |||

| BMI | 1.01 | 0.96 – 1.07 | 0.64 | |||

| BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 1.19 | 0.7 – 2 | 0.53 | |||

| Hospital length of stay | 1.01 | 0.99 – 1.03 | 0.15 | |||

| HFNC | 0.95 | 0.52 – 1.93 | 0.87 | |||

| NIV | 1.79 | 1.01 – 3.22 | 0.04 | 1.93 | 1.08 – 3.52 | 0.03* |

| Intubation/MV | 1.22 | 0.59 – 2.54 | 0.59 | |||

| Use of Dexamethasone | 1.06 | 0.59 – 1.6 | 0.85 | |||

| Use of other corticosteroids | 1.02 | 0.6 – 1.75 | 0.94 | |||

| Use of Tocilizumab | 0.82 | 0.47 -1.44 | 0.49 | |||

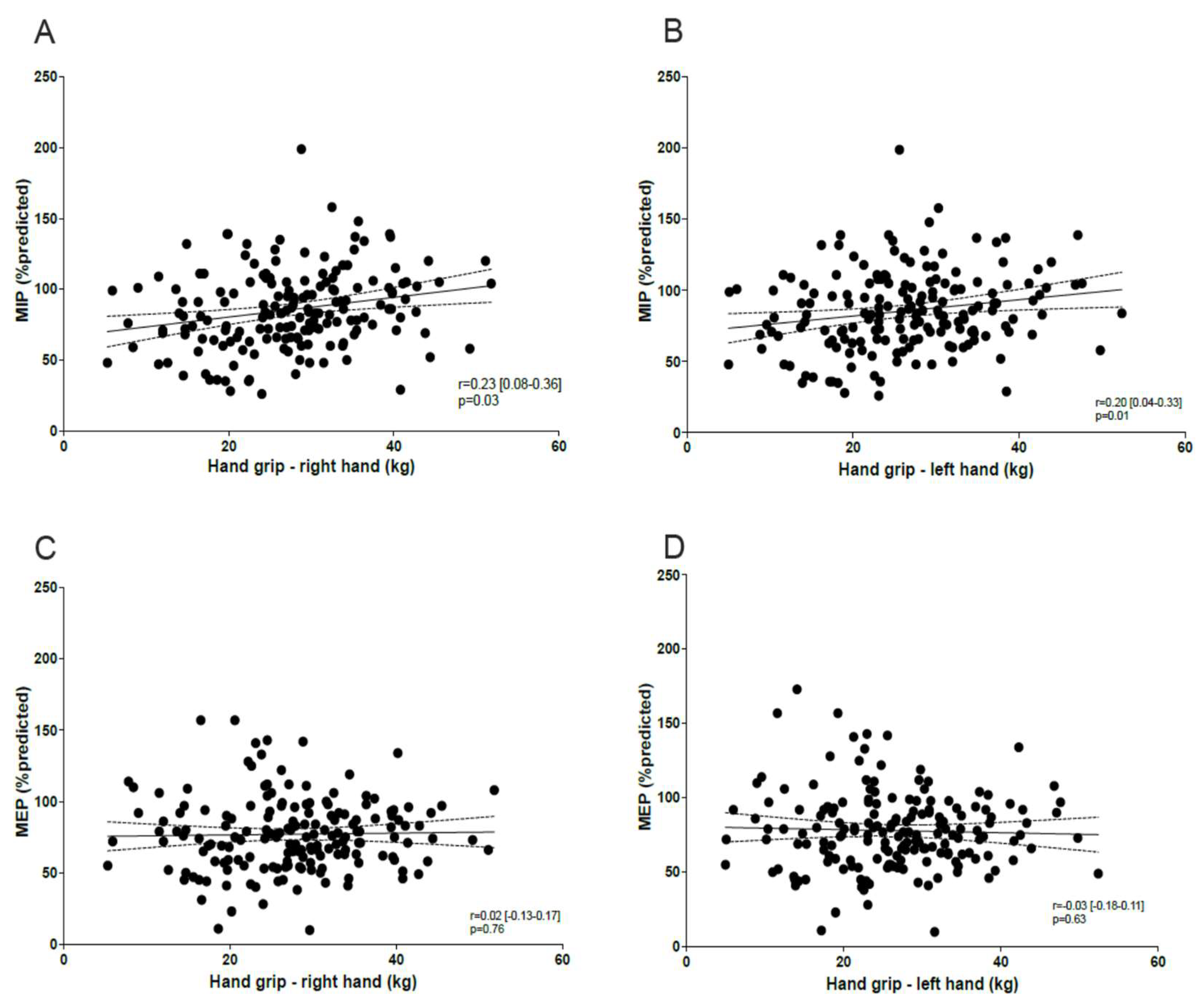

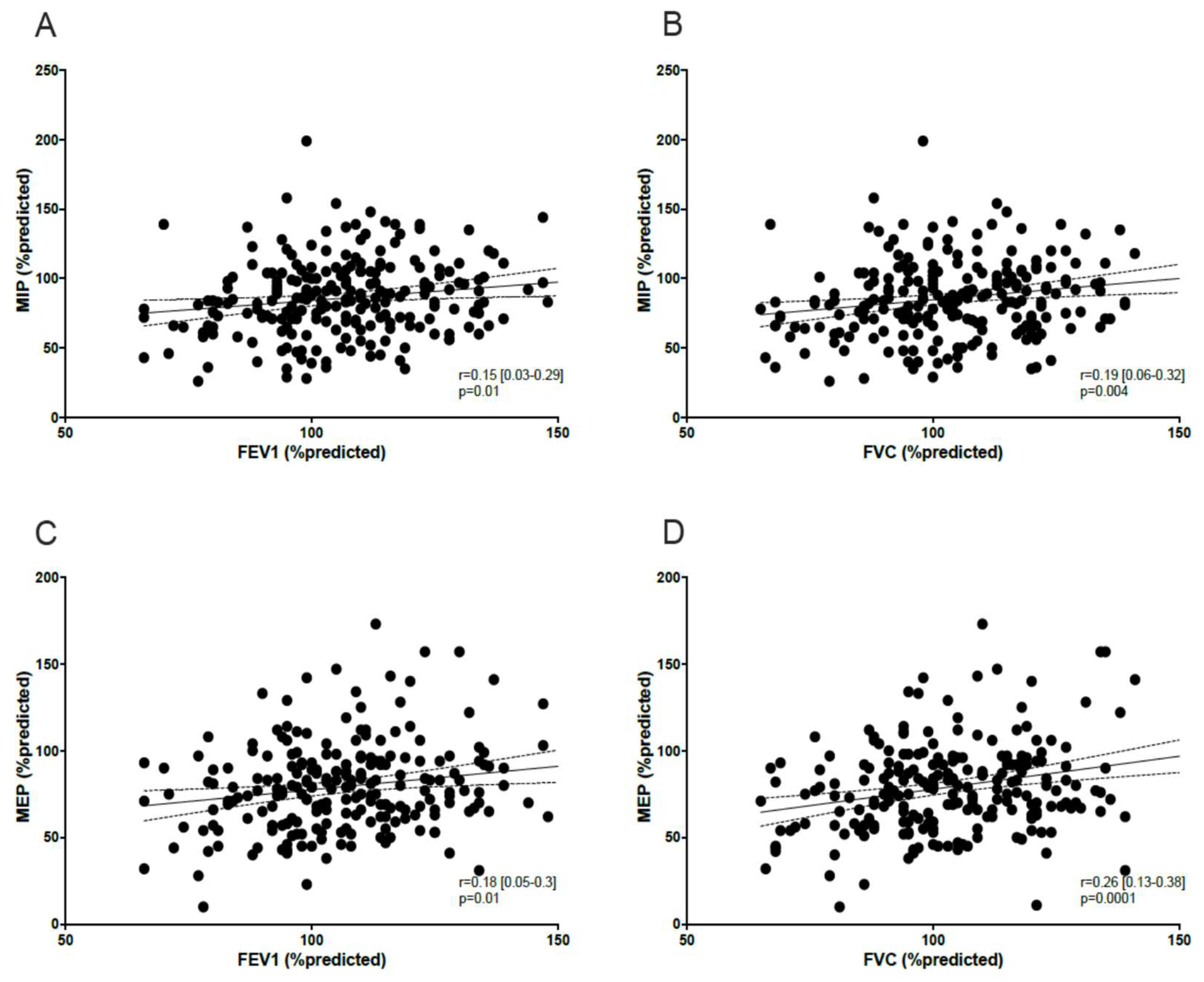

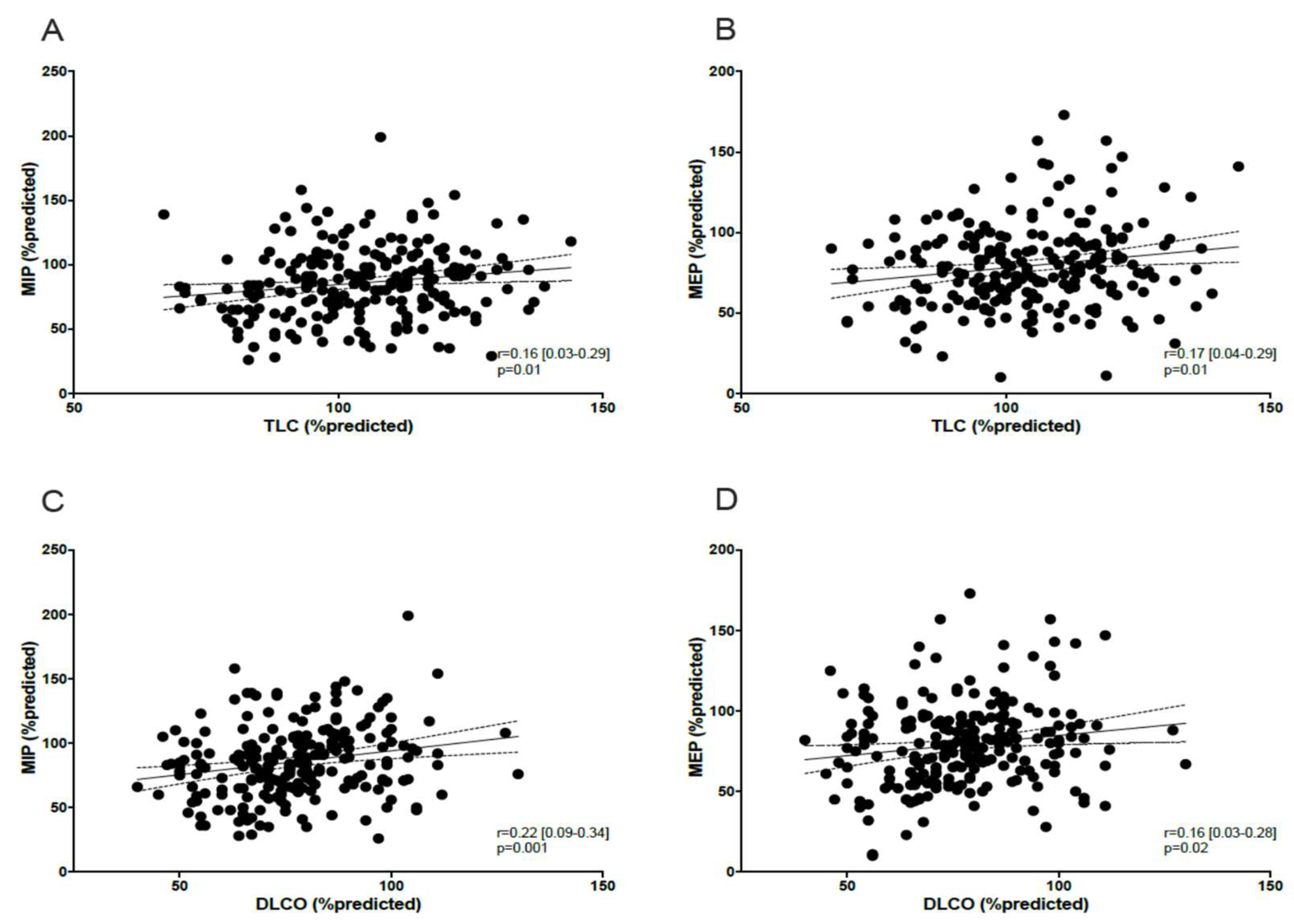

3.1.2. Correlation Between MIP/MEP, Peripheral Muscle Function, Lung Function, and Dyspnea

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organisation. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) situation reports. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports Accessed: 29th September 2024.

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020; 395(10223): 497-506. [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) and Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP). NICE guideline [NG188] Published: Last updated: 11 November 2021. https://www.nice.org.

- Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, Madhavan MV, McGroder C, Stevens JS, Cook JR, Nordvig AS, Shalev D, Sehrawat TS, Ahluwalia N, Bikdeli B, Dietz D, Der-Nigoghossian C, Liyanage-Don N, Rosner GF, Bernstein EJ, Mohan S, Beckley AA, Seres DS, Choueiri TK, Uriel N, Ausiello JC, Accili D, Freedberg DE, Baldwin M, Schwartz A, Brodie D, Garcia CK, Elkind MSV, Connors JM, Bilezikian JP, Landry DW, Wan EY. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med 2021; 27(4):601-615. [CrossRef]

- Mittal A, Dua A, Gupta S, Injeti E. A Research Update: Significance of Cytokine Storm and Diaphragm in COVID-19. Curr Res Pharm Drug Discov 2021; 2:100031. [CrossRef]

- Cesanelli L, Satkunskiene D, Bileviciute-Ljungar I, Kubilius R, Repečkaite G, Cesanelli F, Iovane A, Messina G. The possible impact of COVID-19 on respiratory muscles structure and functions: a literature review. Sustainability 2022; 14:7446. [CrossRef]

- Cacciani N, Skärlén Å, Wen Y, Zhang X, Addinsall AB, Llano-Diez M, Li M, Gransberg L, Hedström Y, Bellander BM, Nelson D, Bergquist J, Larsson L. A prospective clinical study on the mechanisms underlying critical illness myopathy-A time-course approach. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022; 13(6):2669-2682. [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Seisdedos MN, Valcárcel-Linares D, Gomez-Gonzalez MT, Lazaro-Navas I, Lopez-Gonzalez L, Pecos-Martin D, Rodriguez-Costa I. Inspiratory muscle strength and function in mechanically ventilated COVID-19 survivors 3 and 6 months after intensive care unit discharge. ERJ Open Res 2023; 9(1):00329-2022. [CrossRef]

- Nasiri MJ, Haddadi S, Tahvildari A, Farsi Y, Arbabi M, Hasanzadeh S, Jamshidi P, Murthi M, Mirsaeidi M. COVID-19 clinical characteristics, and sex-specific risk of mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med 2020; 7:459. [CrossRef]

- Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, Crapo R, Enright P, van der Grinten CP, Gustafsson P, Jensen R, Johnson DC, MacIntyre N, McKay R, Navajas D, Pedersen OF, Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Wanger J; ATS/ERS Task Force. Standardization of spirometry. Eur Respir J 2005; 26(2):319-338. [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, Crapo RO, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, van der Grinten CP, Gustafsson P, Hankinson J, Jensen R, Johnson DC, MacIntyre N, McKay R, Miller MR, Navajas D, Pedersen OF, Wanger J. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J 2005; 26(5):948-968. [CrossRef]

- Laveneziana P, Albuquerque A, Aliverti A, Babb T, Barreiro E, Dres M, Dubé BP, Fauroux B, Gea J, Guenette JA, Hudson AL, Kabitz HJ, Laghi F, Langer D, Luo YM, Neder JA, O'Donnell D, Polkey MI, Rabinovich RA, Rossi A, Series F, Similowski T, Spengler CM, Vogiatzis I, Verges S. ERS statement on respiratory muscle testing at rest and during exercise. Eur Respir J 2019; 53(6):1801214. [CrossRef]

- Lista-Paz A, Langer D, Barral-Fernandez M, Quintela-del-Rio A, Gimeno-Santos E, Arbillaga-Etxarri A, Torres-Castro R, Vilarç Casamitjana J, Varas de la Fuente AB, Serrano Veguillas C, Bravo Cortes P, Martin Cortijo C, Garcia Delgado E, Herrero-Cortina B, Valera JL; Fregonezi GAF, Gonzalez Montanez C, Martin-Valero R, Francin-Gallego M, Sanesteban Hermida Y, Gimenez Moolhuyzen E, Alvares Rivas J, Rios-Cortes AT, Souto-Camba S, Gonzalez-Doniz L. Maximal respiratory pressure reference equations in herlathy adults and cut-off points for defining muscle weakness. Arch Bronconeumol 2023; 59(12):813-820. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y-C, Bohannon RW, Li X, Sindhu B, Kapellusch J. Hand-grip strength: normative reference values and equations for individuals 18 to 85 years of age residing in the United States. J Orthop Sports Phys Ter 2018; 48(9):685-693. [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, CM. Standardised questionnaire on respiratory symptoms: a statement prepared and approved by the MRC Committee on the Aetiology of Chronic Bronchitis (MRC breathlessness score). Br Med J 1960; 2:1662.

- Combret Y, Prieur G, Hilfiker R, Gravier F-E, Smondack P, Contal O, Lamia B, Bonnevie T, Medrinal C. The relationship between maximal expiratory pressure values and critical outcomes in mechanically ventilated patients: a post hoc analysis of an observational study. Ann Intensive Care 2021; 11:8. [CrossRef]

- Schellekens W-J M, van Hees HWH, Doorduin J, Roesthuis LH, Scheffer GJ, van der Hoeven JG, Heunks LMA. Strategies to optimize respiratory muscle function in ICU patients. Critical Care 2016: 20:103. [CrossRef]

- Tzanis G, Vasileiadis I, Zervakis D, Karatzanos E, Dimopoulos S, Pitsolis T, Tripodaki E, Gerovasili V, Routsi C, Nanas S. Maximum inspiratory pressure, a surrogate parameter for the assessment of ICU-acquired weakness. BMC Anesthesiology 2011; 11:14. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, Tan C, Wu J, Chen M, Wang Z, Luo L, Zhou X, Liu X, Huang X, Yuan S, Chen C, Gao F, Huang J, Shan H, Liu J. Impact of coronavirus 2019 on pulmonary function in early convalescence phase. Respir Res 2020; 21(1):163. [CrossRef]

- Fagevik Olsén M, Lannefors L, Johansson EL, Persson HC. Variations in respiratory and functional symptoms at four months after hospitalisation due to COVID-19: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pulm Med 2024; 24(1):63. [CrossRef]

- Goulart CDL, Arêas GPT, Milani M, Borges FFDR, Magalhães JR, Back GD, Borghi-Silva A, Oliveira LFL, de Paula AR, Marinho CC, Prado DP, Almeida CN, Dias CMCC, Gomes VA, Ritt LEF, Franzoni LT, Stein R, Neto MG, Cipriano Junior G, Almeida-Val F. Sex-based differences in pulmonary function and cardiopulmonary response 30 months post-COVID-19: A Brazilian multicentric study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2024; 21(10):1293. [CrossRef]

- Regmi B, Friedrich J, Jörn B, Senol M, Giannoni A, Boentert M, Daher A, Dreher M, Spiesshoefer J. Diaphragm muscle weakness might explain exertional dyspnea 15 months after hospitalization for COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2023; 15;207(8):1012-1021. [CrossRef]

- Farr E, Wolfe AR, Deshmukh S, Rydberg L, Soriano R, Walter JM, Boon AJ, Wolfe LF, Franz CK. Diaphragm dysfunction in severe COVID-19 as determined by neuromuscular ultrasound. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2021; 8(8):1745-1749. [CrossRef]

- Medrinal C, Prieur G, Bonnevie T, Gravier FE, Mayard D, Desmalles E, Smondack P, Lamia B, Combret Y, Fossat G. Muscle weakness, functional capacities and recovery from COVID-19 ICU survivors. BMC Anesthesiol 2021; 21(1):64. [CrossRef]

- Severin R, Arena R, Lavie CJ, Bond S, Phillips SA. Respiratory muscle performance screening for infectious disease management following COVID-19: a highly pressurized situation. Am J Med 2020; 133(9):1025-1032. [CrossRef]

- Hennigs JK, Huwe M, Hennigs A, Oqueka T, Simon M, Harbaum L, Körbelin J, Schmiedel S, Schulze Zur Wiesch J, Addo MM, Kluge S, Klose H. Respiratory muscle dysfunction in long-COVID patients. Infection 2022; 50(5):1391-1397. [CrossRef]

- Steinbeis F, Kedor C, Meyer HJ, Thibeault C, Mittermaier M, Knape P, Ahrens K, Rotter G, Temmesfeld-Wollbrück B, Sander LE, Kurth F, Witzenrath M, Scheibenbogen C, Zoller T. A new phenotype of patients with post-COVID-19 condition is characterised by a pattern of complex ventilatory dysfunction, neuromuscular disturbance and fatigue symptoms. ERJ Open Res 2024; 10(5):01027-2023. [CrossRef]

- Carfi A, Bernabei R, Landi F, for the Gemelli against COVID-19 Post-acute Care Study Group. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA 2020; 324(6):603-605.

- Shah AS, Wong AW, Hague CJ, Murphy DT, Johnston JC, Ryerson CJ, Carlsten C. A prospective study of 12-week respiratory outcomes in COVID-19-related hospitalizations. Thorax 2021; 76(4):402-404. [CrossRef]

- Arnold DT, Hamilton FW, Milne A, Morley AJ, Viner J, Attwood M, Noel A, Gunning S, Hatrick J, Hamilton S, Elvers KT, Hyams C, Bibby A, Moran E, Adamali HI, Dodd JW, Maskell NA, Barratt SL. Patient outcomes after hospitalization with COVID-19 and implications for follow up: results from a prospective UK cohort. Thorax 2021; 76(4):399-401. [CrossRef]

- Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Gu X, Kang L, Guo L, Liu M, Zhou X, Luo J, Huang Z, Tu S, Zhao Y, Chen L, Xu D, Li Y, Li C, Peng L, Li Y, Xie W, Cui D, Shang L, Fan G, Xu J, Wang G, Wang Y, Zhong J, Wang C, Wang J, Zhang D, Cao B. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet 2023; 401(10393):e21-e33. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-de-las-Penas C, Martin-Guerrero JD, Pellicer-Valero OJ, Navarro-Pardo E, Gómez-Mayordomo V, Cuadrado ML, Arias-Navalón JA, Cigarán-Méndez M, Hernández-Barrera V, Arendt-Nielsen L. Female sex is a risk factor associated with long-term post-COVID related-symptoms but not with COVID-19 symptoms: the LONG-COVID-EXP-CM Multicenter Study. J Clin Med 2022; 11:413. [CrossRef]

- Johnsen S, Sattler SM, Miskowiak KW, Kunalan K, Victor A, Pedersen L, Andreassen HF, Jørgensen BJ, Heebøll H, Andersen MB, Marner L, Hædersdal C, Hansen H, Ditlev SB, Porsbjerg C, Lapperre TS. Descriptive analysis of long COVID sequalae identified in a multidisciplinary clinic serving hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients. ERJ Open Res 2021; 7(3):00205-002021.

- de Godoy CG, Schmitt ACB, Ochiai GS, Gouveia E Silva EC, de Oliveira DB, da Silva EM, de Carvalho CRF, Junior CT, D'Andre A Greve JM, Hill K, Pompeu JE. Postural balance, mobility, and handgrip strength one year after hospitalization due to COVID-19. Gait Posture 2024; 114:14-20. [CrossRef]

- Hussain N, Hansson PO, Samuelsson CM, Persson CU. Function and activity capacity at 1 year after the admission to intensive care unit for COVID-19. Clin Rehabil 2024; 38(10):1382-1392. [CrossRef]

- Shin HI, Kim DK, Seo KM, Kang SH, Lee SY, Son S. Relation between respiratory muscle strength and skeletal muscle mass and hand grip strength in the healthy elderly. Ann Rehabil Med 2017; 41(4):686-692. [CrossRef]

- González-Islas D, Robles-Hernández R, Flores-Cisneros L, Orea-Tejeda A, Galicia-Amor S, Hernández-López N, Valdés-Moreno MI, Sánchez-Santillán R, García-Hernández JC, Castorena-Maldonado A. Association between muscle quality index and pulmonary function in post-COVID-19 subjects. BMC Pulm Med 2023; 23(1):442. [CrossRef]

- Lee JH, Yim J-J, Park J. Pulmonary function and chest computed tomography abnormalities 6-12 months after recovery from COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Res 2022; 23(1):233. [CrossRef]

- Wu X, Liu X, Zhou Y, Yu H, Li R, Zhan Q, Ni F, Fang S, Lu Y, Ding X, Liu H, Ewing RM, Jones MG, Hu Y, Nie H, Wang Y. 3-month, 6-month, 9-month, and 12-month respiratory outcomes in patients following COVID-19-related hospitalization: a prospective study. Lancet Respir Med 2021; 9(7):747-754. [CrossRef]

- Lombardi F, Calabrese A, Iovene A, Pierandrei C, Lerede M, Varone F, Richeldi L, Sgalla G; Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Residual respiratory impairment after COVID-19 pneumonia. BMC Pulm Med 2021; 21(1):241. [CrossRef]

- Hewitt J, Carter B, Vilches-Moraga A, Quinn TJ, Braude P, Verduri A, Pearce L, Stechman M, Short R, Price A, Collins JT, Bruce E, Einarsson A, Rickard F, Mitchell E, Holloway M, Hesford J, Barlow-Pay F, Clini E, Myint PK, Moug SJ, McCarthy K; COPE Study Collaborators. The effect on frailty on survival in patients with COVID-19 (COPE): a multicentre, European, observational cohort study. Lancet Public Health 2020; 5(8):e444-e451. [CrossRef]

- Calvache-Mateo A, Reychler G, Heredia-Ciuró A, Martín-Núñez J, Ortiz-Rubio A, Navas-Otero A, Valenza MC. Respiratory training effects in Long COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev Respir Med 2024; 18(3-4):207-217. [CrossRef]

- Illi SK, Held U, Frank I, Spengler CM. Effect of respiratory muscle training on exercise performance in healthy individuals. Sport Med 2012; 42(8):707-724. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).