1. Introduction

In recent years, the gold standard treatment of locally-advanced rectal cancer has shifted to total neoadjuvant therapy (TNT), where chemotherapy and radiation are administered, often as combined chemoradiation followed by a consolidation chemotherapy doublet, prior to surgery [

1]. In the current practice, TNT is typically recommended based on T3/4 staging, node positivity, involvement of the sphincter, or threatened surgical margins, based on inclusion criteria of published studies. However, no standard approach for total neoadjuvant therapy has been established via randomised clinical trial; the lack of data in this regard brings challenges when counselling patients around expectations for treatment outcomes and toxicities. It also makes it challenging for healthcare providers and teams to recommend treatment regimens to patients. Currently, TNT at many centres involves a collaborative process between surgeons, radiation oncologists, and medical oncologists, as well as the individual characteristics of the patient and patient’s malignancy. The specific TNT regimen and schedule remain, however, at the discretion of the treating physicians, without clear evidence to guide decision-making

Despite the lack of standardised approach, a number of landmark TNT trials have been published in recent years. The OPRA trial demonstrated that consolidation chemotherapy with FOLFOX or CAPEOX following chemoradiation provided superior disease-free survival, when compared to induction chemotherapy with FOLFOX or CAPEOX followed by chemoradiation [

2]. This likely plays into the preference for concurrent chemoradiation followed by chemotherapy, which many modern centres and practitioners consider the current standard of care. Patients included in OPRA randomisation had either T3/4N0 disease, or node-positive disease.

The RAPIDO trial demonstrated that short-course radiotherapy followed by CAPOX or FOLFOX4 prior to surgery was superior to chemoradiation, followed by surgery and the adjuvant therapy, if applicable according to local centre policies [

3]. Patients included in the RAPIDO trial were required to have at least one of the following tumour characteristics: cT4a, cT4b, cN2, extramural invasion, involved mesorectal fascia, or involved lymph nodes.

The PRODIGE-23 trial demonstrated the superiority of neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX, neoadjuvant chemoradiation, surgery, and adjuvant FOLFOX6 or capecitabine compared to neoadjuvant chemoradiation, surgery, and adjuvant chemotherapy (without the neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone) [

4]. Patients on this trial were required to have T3/4 disease.

More recently, the UNION trial included immunotherapy agent camrelizumab with CAPOX given neoadjuvantly after short course radiation, followed by resection and adjuvant camrelizumab/CAPOX, versus a control arm of long-course chemoradiation, surgery, and adjuvant chemotherapy [

5]. Early results have demonstrated improved pathological complete response rates in the immunotherapy arm. Patients included in this trial had T3/4 disease and/or node-positive disease. Widely publicised has also been the open-label phase II trial using dostarlimab for patients with microsatellite-instability high (MSI-H) rectal cancer, leading to a complete response for some patients [

6].

From these trials, one can easily appreciate the variety of approaches to TNT – including the lack of “total” therapy in the neoadjuvant approach, as well as the diversity of inclusion criteria – which makes translating results and findings into the real world challenging. Consequently, we conducted a real-world analysis of local treatments for rectal cancer, with an emphasis on examining patient-relevant outcomes including toxicity, efficacy, and risk factors for toxicity.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis of all localised rectal cancer patients who were treated by oncology at the London Regional Cancer Program (total 617), from June 1st 2019 to July 14th 2022. The June 2019 date was selected in order to ensure some patients treated with non-TNT regimens were included (the advent of TNT was shortly after the June 2020 ASCO presentation).

For context, during the selected time frame, MSI-H LARC was not routinely being treated neoadjuvantly with immunotherapy (immunotherapy was reserved only for metastatic or unresectable cases); consequently, no patients with treated immunotherapy were included in this analysis.

Patient Inclusion Criteria:

Diagnosis of localized rectal cancer

Treated for non-metastatic rectal cancer

Received at least one fraction of radiation, one dose of chemotherapy, or one dose of immunotherapy

At least 18 years of age

Received treatment at London Health Sciences Centre

Patient Exclusion Criteria:

Data Collection

The list of variables which collected via retrospective chart review are laid out below.

Patient Demographics: Age at diagnosis, date of birth (month/year only), sex, disease stage (TNM), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group – Performance Status score, tumour histologic type, clinical TMN stage, microsatellite instability (MSI) status, tumour distance from anal verge, CRM threatened, sphincter involvement, smoking status (current/former/never), comorbidities (including diabetes, obesity, COPD, IBD, cardiac issues, neuropathy, thyroid issues)

Treatment-Specific Information: Treatment received (TNT, neoadjuvant + adjuvant, adjuvant), modality of treatment (chemotherapy, chemoradiation, radiation, immunotherapy), order of treatment, time interval between treatments (including surgery), dates of radiation, total radiation dose, total radiation fractions, delays in radiation, actual dose and fractions delivered vs planned, specific chemotherapeutic agent administered with radiation (if applicable), chemotherapy schedule with radiation, chemotherapy dose with radiation, chemotherapy regimen received, dates of solo chemotherapy, treatment strategy (neoadjuvant vs adjuvant vs both) delays in chemotherapy, dose of chemotherapy, actual dose received vs planned, immunotherapy received (if any), doses of immunotherapy, surgery vs watchful waiting approach, date of surgery, time to surgery, type of surgery, total treatment length

Outcomes: Adverse effects (see below), response to treatment (progression/stable disease/partial response/complete response), progression-free survival, overall survival, time to surgery, surgical outcomes (R0/R1/R2 resection), pathology (TMN stage), surgeon satisfaction (as determined from OR note), watch/wait approach vs surgical intervention

Adverse Effects: Presence, grade, and timing of side effects from radiation and from chemotherapy (pain, diarrhoea, skin desquamation, fatigue, nausea/vomiting, mucositis, hand/foot syndrome, neuropathy, renal compromise, cold sensitivity, and other symptoms). Grading based on CTC-AE version 5.0, and actionable vs non-actionable toxicities. Actionable toxicities will be further delineated into those requiring treatment delay, requiring outpatient pharmaceutical management, requiring inpatient management at the ward level, requiring ICU-level care, requiring treatment cessation, or death.

To assess efficacy of TNT in a real-world centre

To assess toxicity of TNT in a real-world centre

To compare TNT outcomes to non-TNT outcomes in a real-world centre

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Western University [

7,

8]. REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure, web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research studies, providing 1) an intuitive interface for validated data capture; 2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; 3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and 4) procedures for data integration and interoperability with external sources.

Demographic data was analysed via descriptive statistics. Response categories between TNT and non-TNT groups were compared using the Chi-squared test. Two-sided p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using R version 4.4.0.

3. Results

A total of 617 patients were identified by medical records as potential candidates for the study. Of these, 289 were included in the final analysis. Reasons for exclusion were identification of metastatic disease prior to commencing treatment, treatment for recurrent disease, failure to receive at least one dose of radiation and/or chemotherapy, treatment at an outside centre, and treatment dates outside the collection time frame.

Of the patients treated, 64.5% (

n = 187) were male. The median age was 67. Clinical staging was most frequently IIIB (44.8%;

n = 130) and IIA (26.2%;

n = 76). 23 patients (8%) were ECOG 2+. The vast majority of diagnoses (88.3%;

n = 256) were adenocarcinoma. 112 (38.6%) of patients had documentation of threatened circumferential margins, and 47 (16.2%) had documented sphincter involvement. A full list of demographic information is available in

Appendix 1.

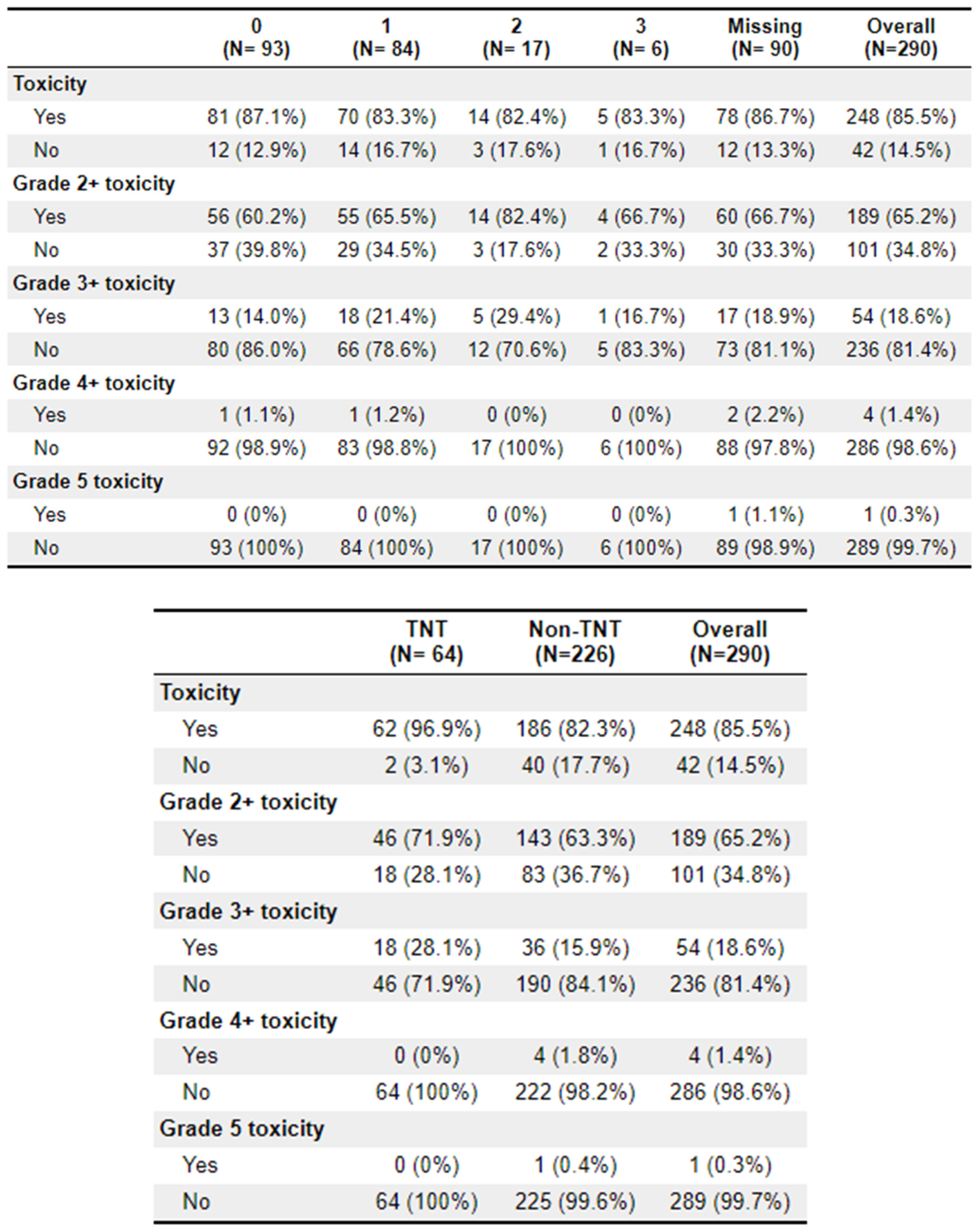

A total of 64 patients received treatment with TNT. Of these patients, 62 (96.9%) experienced toxicities, compared to 186 (82.3%) of the non-TNT patients. Grade 2+ toxicities were 46 (71.9%) and 143 (63.3%), respectively. The most common adverse effects to treatment were diarrhoea (

n = 150), fatigue (

n = 131), and cold sensitivity (

n = 74). Further toxicity information is available in

Appendix 2.

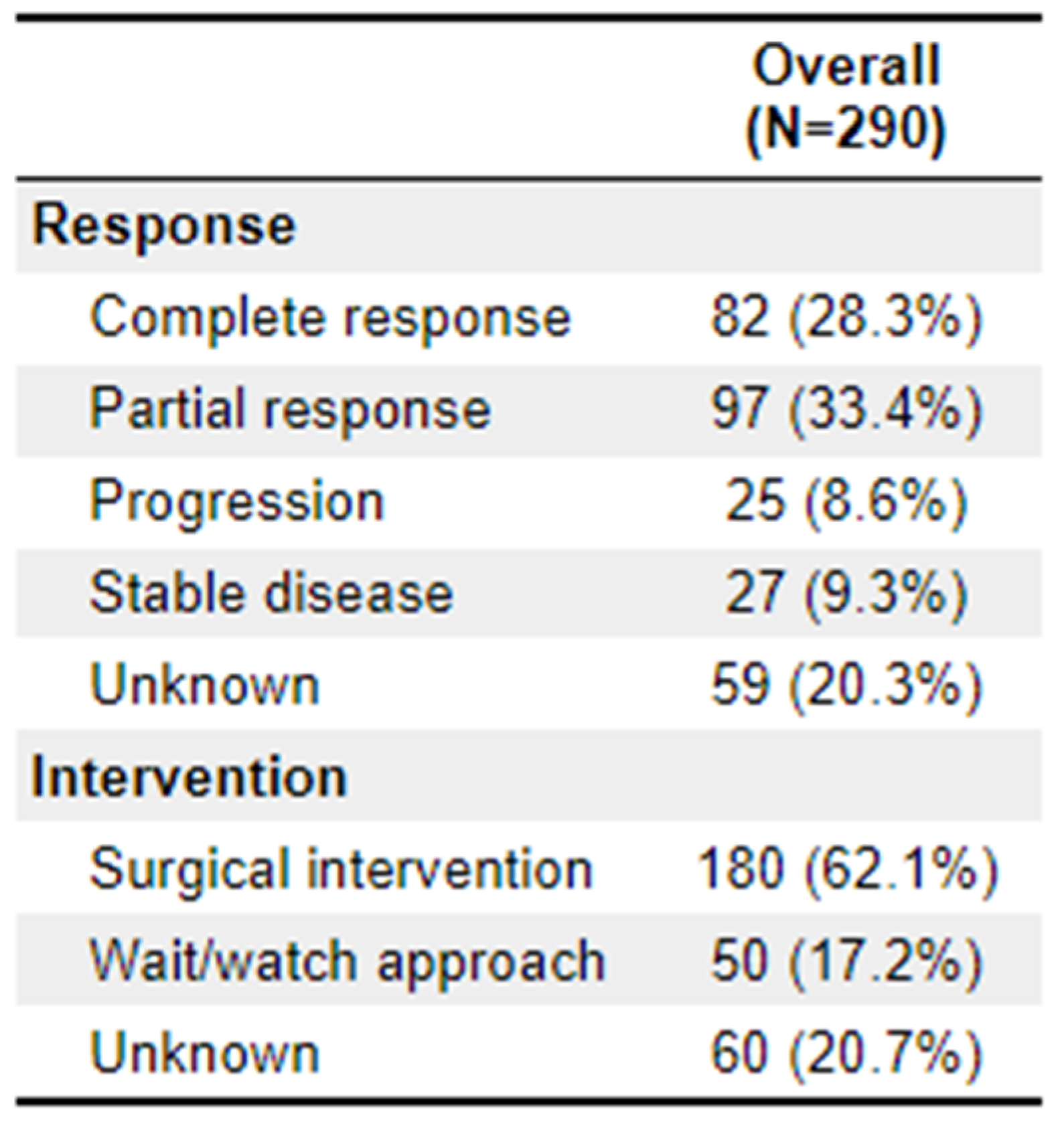

Differences in treatment response categories between TNT and non-TNT were significant (p = 0.012). For patients receiving TNT, 43.8% (n = 28) showed complete response, 31.3% (n = 20) showed partial response, and 9.4% (n = 6) showed disease progression. In the non-TNT cohort, 23.9% (n = 54) showed complete response, 34.1% (n = 77) showed partial response, and 8.4% (n = 18) showed disease progression. Ultimately, 60.9% (

n = 39) of the TNT arm underwent surgical intervention, which is roughly equivalent to the 141 (62.4%) of the non-TNT arm. Further outcome details are available in

Appendix 3.

4. Conclusions

In summary, we present a retrospective analysis of patients with LARC who underwent TNT and non-TNT-directed therapy.

Our studies provide some interesting findings. One key finding is that treatment was highly toxic, with nearly all patients in the TNT arm and the vast majority in the non-TNT arm experiencing some side effects. The majority of patients also experienced grade 2+ side effects. It is logical that the rate of side effects and severe side effects were higher in the TNT arm, given that this is more intense treatment given in a typically six-month time frame. As per centre policy, the majority of patients receiving TNT received chemoradiation with 5-FU-based therapy, followed by 4 months of either XELOX or FOLFOX.

Although we did not have enough events or long enough follow-up to determine survival outcomes, we do note that the percentage of patients experiencing a complete response from TNT was nearly double those who did not undergo TNT. This is in keeping with the rationale for performing total neoadjuvant therapy.

Given that this is a single-centre retrospective real-world analysis, there are limitations as to the generalisability of the study’s findings. Of note, many patient demographics (i.e. ECOG) were not captured pre-treatment, likely due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the entrance of virtual care to cancer centres. Likewise, the non-TNT group contained a diverse patient population, ranging from those who received adjuvant only or neoadjuvant + adjuvant, to those with smaller tumours or frailer physical conditions who received short-course radiation, only. Additionally, the similarity in patients undergoing TNT versus non-TNT in surgical intervention may be attributed to the sicker, frailer patients in the non-TNT group who opted for lighter therapy (i.e. radiation alone) as a more palliative measure. Finally, no patients in our study received neoadjuvant immunotherapy as, during the study window, neoadjuvant immunotherapy for rectal cancer was not a funded option in Ontario.

All in all, however, these findings suggest that TNT harbours both benefit and risk in a real-world population, and both of these aspects should be considered when deciding on a treatment approach for an individual patient. More work in the area is needed to determine longer term survival, as well as impact of surgery versus organ preservation approach on patient outcomes.

Author Contributions

Author BP was responsible for project design, data collection, and manuscript writing. Authors WW, BS, and MM were responsible for data collection. Author EM was responsible for data analysis. Author ET was responsible for project conception, design, editing, and oversight.

Funding

The research team would like to that CIBC for providing fellowship funding for this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Appendix A. Demographic Information

References

- Petrelli F, Trevisan F, Cabiddu M, Sgroi G, Bruschieri L, Rausa E, et al. Total Neoadjuvant Therapy in Rectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Treatment Outcomes. Vol. 271, Annals of Surgery. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Thompson H, Kim JK, Yuval JB, Verheij F, Patil S, Gollub MJ, et al. Survival and organ preservation according to clinical response after total neoadjuvant therapy in locally advanced rectal cancer patients: A secondary analysis from the organ preservation in rectal adenocarcinoma (OPRA) trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2021;39(15_suppl). [CrossRef]

- Bahadoer RR, Dijkstra EA, van Etten B, Marijnen CAM, Putter H, Kranenbarg EMK, et al. Short-course radiotherapy followed by chemotherapy before total mesorectal excision (TME) versus preoperative chemoradiotherapy, TME, and optional adjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer (RAPIDO): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(1). [CrossRef]

- Conroy T, Bosset JF, Etienne PL, Rio E, François É, Mesgouez-Nebout N, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with FOLFIRINOX and preoperative chemoradiotherapy for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer (UNICANCER-PRODIGE 23): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(5). [CrossRef]

- Lin Z, Zhang P, Hou Z, Tao K, Zhang T. Neoadjuvant short-course radiotherapy followed by chemotherapy plus camrelizumab versus long-course chemoradiotherapy followed by chemotherapy for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer: A randomized, multicenter, open-label phase 3 trial (Union). Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2023;41(16_suppl). [CrossRef]

- Cercek A, Lumish M, Sinopoli J, Weiss J, Shia J, Lamendola-Essel M, et al. PD-1 Blockade in Mismatch Repair–Deficient, Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2022;386(25). [CrossRef]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. Vol. 95, Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).